- Department of African and African American Studies, Berea College, Berea, KY, United States

In our continued study of Blackness and being, we must emphasize the quotidian—or everyday—strategies that young Black womxn and femmes employ to cope with anti-Black gendered racism and its psychological impact at historically and predominantly white institutions. As such, the purpose of this article is to give prominence to the resistance types of coping strategies that Black womxn and femme college students used to maintain their dignity at a predominantly white university of the American West, where the psychological aftermath of anti-Black gendered racism remains hidden under dense layers of neoliberalism, affluence, faux progressivism, and whiteness. I approach this topic from the conceptual perspective of Blackness and being at the nexus of gender by combining discourses on the ontologies of Blackness, and Black feminist thought and epistemology. In the study that informs this article, I utilized qualitative mixed methods—one-on-one interviews, focus group interviews, and participant observation. Like our foremothers whose survival was predicated on the subtle and purposeful coping strategies they engaged, Black womxn and femme college students’ resistance coping styles were demonstrated in the everyday presence of anti-Black gendered racism. Findings reveal that Black womxn and femme undergraduate students demonstrated three main types of resistance coping when experiencing anti-Black gendered racism: (1) self-education; (2) direct confrontation with aggressors (e.g., racists, sexists, homophobes, elitists); and (3) humor. I conclude with recommendations on transformative justice, monetary trusts, longitudinal data collection, and critical curriculum at historically and predominantly white educational institutions.

Introduction

Extent literature reveals that Black womxn and femmes in higher education experience gendered racism and actively resist is by practicing various herstorical, intersectional, and culturally-relevant means (Lewis et al., 2013; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Leath and Chavous, 2017, 2018). Scholarship shows that many Black womxn and femmes demonstrate active resistance through talking back (hooks, 1989), collective organizing (Davis, 1972; Taylor, 1998; Springer, 2005), and anger (hooks, 1996; Perlow, 2018; Lorde, 2020; Pearl, 2020). Black womxn’s and femmes’ acts of resistance in higher education is intergenerational knowledge and praxis exchanged through othermothering (Mogadime, 2000; Griffin, 2013; Collins, 2022), mentorship and sister circles (Green and King, 2001; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Kelly and Fries-Britt, 2022; Parrott, 2022; Samuels and Wilkerson, 2022), radical care (Luney, 2021b; Chambers and Sulé, 2022; Harushimana, 2022), and sharing knowledge to survive (Combahee River Collective, 1977; Hull et al., 1982). Literature on Black womxn’s and femmes’ active resistance in higher education demonstrates that Black women and femmes pass down and exchange knowledge to one another through their communal (Collins, 2009; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Jones and Sam, 2018), pedagogical (hooks, 2014; Gines et al., 2018), and epistemological (Collins, 2004, 2009; Dotson, 2015; Nadar, 2019; Porter et al., 2022) efforts.

Our academic foremothers, sisters and siblings, aunties, and cousins weave their lessons together, which loom over us and through us in the dusty, thin-aired, and arid universities of the American West. For their narratives guide us in our journeys of surviving anti-Black gendered racism at historically and predominantly white universities. Our collective and lived experiences of coping to survive in higher education are pertinent to establishing discourse around gendered Blackness and being, or our mere existence. Once we understand Black womxn’s and femmes’ existence within predominantly and historically white higher education institutions that benefit from colonization (e.g., land-grant colleges and universities), we paint a more comprehensive picture of Black youth claiming their humanity and dignity within educational settings.

In our continued study of Blackness and being, we must emphasize the quotidian strategies that young Black womxn and femmes employ to cope with anti-Black gendered racism and consequent psychological traumas at predominantly white institutions. These traumas include exhaustion; self-doubt and an altered self-image; anger; embarrassment; anxiety and melancholia; alienation; and distrust in the university or peers (West et al., 2010; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Shahid et al., 2018; House, 2020; Luney, 2021b). As such, the purpose of this article is to give prominence to the resistance coping (Lewis et al., 2013; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Corbin et al., 2018; Shahid et al., 2018; House, 2020) that Black womxn and femme college students use to maintain their dignity at University of Colorado Boulder (CU Boulder), a predominantly white university of the American West. There, the aftermath of gendered anti-Blackness remains hidden under dense layers of neoliberalism, affluence, faux progressivism, and whiteness (Luney, 2021a,b). Like our foremothers, whose survival was predicated on the bold and purposeful coping strategies they engaged, Black womxn and femme college students’ resistance coping styles are demonstrated in the everyday presence of anti-Black gendered racism.

Throughout this article, I address the resistance coping strategies that Black womxn and femme college students practice. I approach this topic from a conceptual perspective consisting of Blackness and being, and Black feminist thought and epistemology in hopes to emphasize students’ everyday agency and survival at a historically and predominantly white university. I utilized qualitative mixed methods in the study that informs this article. Findings from the study reveal that Black womxn and femme college students who participated in the study demonstrated three main types of resistance coping when dealing with anti-Black gendered racism:

1. self-education;

2. direct confrontation with aggressors (e.g., racists, sexists, homophobes, elitists); and

3. humor.

To conclude, I call researchers and higher education personnel to address the everyday life of Black womxn and femme being in higher education. We must esteem what means for college-age Black womxn and femmes to be, particularly within political and socio-herstorical contexts at the local level. I present transformative justice, monetary trusts, longitudinal data collection, and critical curriculum as recommendations to mitigate the impact of anti-Black gendered racism on Black womxn and femme undergraduates and the diligence that coping with it entails.

Conceptual framework and scholarly framing

On Blackness and being: Anti-Black settler colonialism, enslavement, and a colorblind society

I define being as the ontological life of Blackness to make meaning of our existence rooted in histories and herstories of colonization and enslavement. Being captures the intricacies of what it means to be, to exist, to survive, and to continue living in white supremacist and capitalist systems that require the exploitation and death of Black bodies, cultures, and vitality. This article partially details being for Black womxn and femme undergraduate students at the University of Colorado Boulder (henceforth referred to as CU Boulder)—the study site—situated within the context of anti-Black settler colonialism. Anti-Black settler colonialism categorized “Others,” or the subaltern, to incite racial hierarchies in which white Euro-Americans monetarily benefit from Black subjugation, fungibility, and liminality through enslavement, driving settler-colonial ventures. Connections between humanism—or the making of “Man” and “human”—and control over land and property persist as main components of anti-Black settler colonialism. As geopolitical, ideological, theoretical, cultural, spiritual, and existential explorations led to definitions of “Man” based on the precipice of “incommensurable ontological (anti)Blackness” (Bilge, 2020, p. 2302; Sexton, 2011), race and capital undergirded categorizations of white Euro-Americans as human, colonized Indigenous peoples as sub-human, and colonized and enslaved Africans and Black Americans as non-human to justify the anguishes of colonization (Wynter, 1989; Mills, 1997; Wilderson, 2010, 2020; King, 2019).

Exploring Colorado’s regional and state sociopolitical history of anti-Blackness from a decolonial perspective reveals a colorblind racist society (Bonilla-Silva, 2006, 2015; Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich, 2011) as well. At Colorado’s founding, white tolerance of African Americans was not based on the recognition of Black people’s humanity and dignity, nor was it an accurate understanding of power, oppression, and white privilege. Instead, white tolerance was based on the dehumanization of other non-white Westerners like Indigenous people, Mexicans, and Chinese immigrants (Wayne, 1976; Junne et al., 2011). This type of tolerance of Black folks persists in higher education institutions in the West, such as CU Boulder, due to the fungibility of the Black body and Blackness for the sake of labor, monetary and social gain, and as a tool to occupy Indigenous spaces and maintain racial-ethnic hierarchy based on cultural familiarity (e.g., English as a primary language). Tolerating Blackness is unequivocally and largely due to university administrators’ lack of critical approaches to white supremacy and racism in the academy.

Within the context of anti-Black settler colonialism and a colorblind society, CU Boulder instituted non-discriminatory policies since its inception and never explicitly implemented procedures that discriminated against students on the basis of race, gender, class, ability, or other groups, classes, or categories in the written record or university policy (Hays, 2010). In fact, CU Boulder’s campus community admitted non-white students without prejudice. On the contrary, CU Boulder’s campus and the Boulder City community instilled colorblind racism and anti-Blackness in the form of de facto segregation and white supremacy. CU Boulder’s colorblind racism and anti-Blackness by way of segregation prevailed adjacent to non-discriminatory policy at the university (Hays, 2010). CU Boulder has always been “bound by law and regulation to allow minority attendance and to educate without prejudice,” and held responsible by loco parentis (Hays, 2010, p. 145). Yet, neither students, faculty, nor administration confronted inequity, racial separation, or white supremacy. According to Hays (2010, 145), “passive egalitarianism appears to have coexisted with campus and local customs of segregation.”

Just as white supremacy and segregation persisted through “passive egalitarianism” within CU Boulder, the university subjected Black students to anti-Black racism concurrent with Colorado law mandating that higher education institutions educate persons based on merit as opposed to racial and gender identity. The landmark United States Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson reigned as the guiding law for race relations, and social and political codes, instituting “separate but equal” mores throughout the state. Subsequently, the university’s apathetic approaches toward protecting student welfare sustained separate but equal sentiments, guiding anti-Black race relations at the institution. Black people faced an insurmountable level of anti-Black racism from the 1800s throughout the 1900s (McLean, 2002, 2018; Hays, 2010). Additionally, Boulder City began outsourcing blue-collar mining and industrial jobs, which led to a decrease in the county’s Black population and brought in white Southerners to boost the tourism and white-collar economies around 1910. Resultingly, Black folks faced harsher anti-Blackness, such as segregated housing where Black people could only live north of campus; segregated restaurants, theaters, and other businesses and services on The Hill and throughout the city; and racist stereotypes depicted in cartoons, editorials, and other media publications (Hays, 2010).

At the University of Colorado’s flagship institution, administrators and faculty denied Black students from admittance and enrolling in courses, and rejected Black students from campus services and assistance. Members of white Greek-letter organizations explicitly refused Black students from participating in their organizations, and CU Boulder’s student life inhibited Black students from participating in extracurricular and social events. Because of the university’s and city’s segregationist mores, Black students had to travel to Denver—approximately 30 miles away from campus—to be serviced by barbers and hair stylists, obtain their teaching hours for practicum, and receive medical and mental health attention. Segregationist efforts by the university and the city particularly affected Black womxn’s work life in the mid-1900s because they could not find kitchen or custodial work at businesses on The Hill or in boarding houses as their male counterparts did (McLean, 2002; Armitage, 2008). Furthermore, Black students who attended CU Boulder were subject to segregated housing practices in that they were banned from campus housing, leaving them responsible for paying higher prices for room and board in houses with inadequate living conditions located north of campus (McLean, 2002, 2018; Hays, 2010). As part of a long linage of anti-Blackness, white supremacy continues to persist against Black students, and Black womxn and femme students specifically, at CU Boulder.

Anti-Black settler colonialism dictates Black college womxn’s and femmes’ experiences of coping in spaces that have been colonized through the logics of whiteness to maintain white supremacy and racialization. It informs how I analyzed the study site, emphasizing that Black femme bodies are contemporarily and herstorically positioned in the humanistic settler-colonial project in Colorado. Furthermore, anti-Black settler colonialism highlights the afterlife of enslavement (Spillers, 1987; Wynter, 1989, 2003; Hartman, 1997, 2007; Sharpe, 2016; King, 2019; Wilderson, 2020) that African Americans inherit. I argue that this afterlife—and the assumed mark of enslavement that continental Africans living in the United States (US) must also face—deems Black college womxn and femmes as undeserving to thrive within higher education institutions upholding settler-colonialism, and are instead positioned as liminal in these spaces.

In assessments of Black femme life at universities, we must account for anti-Black settler colonialism, the afterlife of enslavement, and colorblind racism because the effects remain fixed in our current lives. Through their existence, Black womxn and femme undergraduate students continue to battle anti-Black settler colonialism, the mark of enslavement, and colorblind racism, which reveals themselves as anti-Black gendered racism. Black being and survival—by way of resistance coping techniques—enmeshes with broader historic and sociopolitical implications of anti-Black settler colonialism amidst a gendered and anti-Black herstory at CU Boulder. In turn, Black womxn and femmes have maintained resistance coping strategies to deal with gendered anti-Black racism at CU Boulder.

Black feminist thought and epistemology

Black womxn,1 as a group, gain, generate, and share knowledge through their overlapping experiences of oppression (Collins, 2004, 2009; Dotson, 2015; Nadar, 2019; Porter et al., 2022). These knowledges tell us about the relationship between connected oppressions exasperating the gravity of inequality that Black womxn experience brought about by the matrix of domination, or the organization of intersecting oppressions Black womxn face. Furthermore, Black womxn demonstrate the role of agency in consciousness-building and productions of knowledge that criticize human subjugation. In combination, these factors make up Black feminist thought, which is a critical social theory where US African American womxn’s collective wisdom and consciousness motivate creations of specialized knowledge from common thematic experiences of oppression and resistance (Collins, 2004, 2009; Dotson, 2015; Nadar, 2019; Porter et al., 2022).

Regarding knowledge production, Black feminist epistemology allows us to redefine the term “intellectual” to include not only Black womxn scholars in academia, but alternative thinkers outside the academy providing oppositional knowledge as well. While Black womxn’s intellectual thought is suppressed in the academy and society—through surveillance in bureaucratic institutions and segregation in structural domains of power—we develop Black feminist thought by reclaiming intellectuals through “discovering, reinterpreting, and analyzing” (Collins, 2009, p. 16) their works with a Black feminist epistemological framework.

Additionally, Collins emphasizes the importance of “the group” stating that, although responses between individual group members are diverse, Black womxn share common experiences that elicit their standpoints. This results in their agency and resistance against subjugation through self-determination and self-definition. Moreover, because Black womxn’s experienced oppressions shift over time, Black feminist thought is dynamic and everchanging. The day-to-day experiences of Black womxn scholars and alternative thinkers encompass a holistic view of the matrix of domination because they experience oppressions at various axes; hence, Black womxn experiences decrypt how power and control operate. Within this framework, a transversal politics is achieved, which occurs when we observe the intersects of others’ oppressions without privileging our own (Collins, 2004, 2009; Dotson, 2015; Nadar, 2019; Porter et al., 2022).

Black feminist thought and epistemology re-orientate how knowledge is created by centering Black womxn and femme undergraduate students as alternative thinkers to orthodox and hegemonically white supremacist ways of producing knowledge. Drawing on Black feminist thought and epistemology, I argue that Black womxn’s and femmes’ shared experiences with gendered anti-Blackness at a historically and predominantly white university elicits further investigation on the lineage of their resistance coping strategies. Placing recent and past Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ experiences with resistance coping in conversation with one another yields a generational discourse on being and survival. Just as the afterlife of enslavement remains present in our current lives, so too does our will to cope with the encumbrances of anti-Black, anti-womxn, and anti-femme being.

Resistance coping for Black womxn in higher education

Resistance is a form of engagement coping, which occurs when people actively address stressors and stress-related emotions. Types of resistance coping that Black college womxn demonstrate are defying Eurocentric beauty standards, speaking up about gendered racism on campus, and education and advocacy (Lewis et al., 2013; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016). Coping scholarship on racial identity centrality suggests that African Americans cope differently than other racial-ethnic groups based on culturally specific strategies learned and passed on throughout generations, and the types of discrimination we face (Daly et al., 1995; Coll et al., 1996; Utsey et al., 2000; Johnson, 2001; Scott, 2003; Blackmon et al., 2016). Researchers have found that Black womxn in college use cognitive, emotional, ritual, collective, and spiritual-centered methods of Africultural coping, and that Black college womxn cope by relying on their racial self-identity (Robinson-Wood, 2009; House, 2020). Other studies show that racial identity fails as a strategy to mitigate the impact of gendered racism on mental health, and does not prevent psychological distress as it may cause more race-related stress than other coping strategies (McKnight, 2003; Robinson-Wood, 2009; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Burton, 2017; Luney, 2021b).

Many Black womxn attending historically and predominantly white institutions cope by relying on the resilience that comes with being a Strong Black Woman (Lewis et al., 2013; Corbin et al., 2018; Shahid et al., 2018; House, 2020). In many instances, Black college womxn counteract repressive and silencing dynamics on campus but are careful not to embody the Angry Black Woman stereotype in these efforts (Corbin et al., 2018). The Strong Black Woman is personified in response to racially gendered microaggressions to avoid embodying the Angry Black Woman archetype. Adopting the Strong Black Woman archetype to fight gendered racism, or misogynoir (Bailey and Trudy, 2018; Leath et al., 2021) in this case, may have negative impacts on Black womxn’s wellbeing such as racial battle fatigue, where constant exposure to gendered anti-Blackness elicits emotional, psychosocial, and physiological stress responses (Smith et al., 2007; Smith, 2014; Corbin et al., 2018; Quaye et al., 2019; Rollock, 2021). Another result of coping with the Strong Black Woman identity is a potential increase in perceived racial tension on campus that causes stress but does not prevent it because the cause of this stress is administrators’ failure to improve race and gender relations on campus (Shahid et al., 2018).

The current study situates Black womxn and femme college students’ resistance coping—which is connected to Black womxn’s and femmes’ being—as a human response to gendered anti-Black racism rather than a solution to it. In addition, the current study delves into the retribution that Black womxn and femme undergraduates face when they resist gendered anti-Black racism and advocate for themselves, providing implications for the Angry Black Woman myth and resistance coping. While previous scholarship stresses the role of the Strong Black Woman in Black womxn undergraduate coping, the findings of the current study reveal that the Angry Black Woman trope arises as a consequence to resistance coping strategies. Findings also provide implications on Black womxns’ and femme’s agency in their educational journeys and humor, accentuating the significance of their humanity in a colonial, anti-Black, and anti-womxn and femme institution.

Materials and methods

Outsiders within the academy: Researcher positionality and student narrators

While outsider-within status (Collins, 1986, 1999, 2009; Howard-Hamilton, 2003; Wilder et al., 2013; Bartman, 2015; Garrett and Thurman, 2018; Porter et al., 2020; Porter, 2022; West, 2022) speaks to Black womxn who are academicians, I employ the term to refer to myself and Black womxn and femme participants, or “narrators” (Bignold and Su, 2013), in the current study. I occupy an outsider-within position because I choose to remain in the academy knowing that I will never obtain full insider status in institutions that were set up for and cater to whiteness and capital. Additionally, I occupy an outsider-within position because I choose to bring my experiences as a Black Kentuckian womxn who grew up in poverty to the forefront of my research and existence in the academy. I use my outsider status to avoid assimilating into orthodox ways of interpreting social phenomena.

I recognize the narrators of this study as outsiders within the university as they were perpetually perceived as “strangers” (Collins, 1986, p. 15) at the study site, and because they maintained critical perspectives of the academy. Narrators who are Black, womxn, and femme—amongst other multiply marginalized identities—provide an epistemology that recognizes the persistence of anti-Black gendered racism in higher education, and the significance of coping as form of surviving higher education institutions.

Researcher positionality

I often considered myself an outsider from the narrators because of my education status, where I am from, socioeconomic status, the type of undergraduate institution I attended, and power dynamics between undergraduates and me that were based on my roles as a doctoral student, teaching assistant, part-time instructor, staff member, and community organizer. Through these roles, I established relationships with Black students, some of whom participated in the study. The participant observation phase of this study underscores my positionality as a researcher, how I analyzed the study site, and implications for strained relationships between myself and narrators that expound how I was an outsider from narrators.

Alternatively, my status as a Black womxn who matriculated through the CU education system very much made me an insider with the students who were the focus of the study; one with experiential knowledge about how Black womxn and femme students were treated at the university. My involvement with grassroots organizations might have encouraged students to see me separate from a strictly academic role. Furthermore, my early interactions with grassroots organizations and Black students on campus allowed me to learn more about their lives as CU Boulder students.

It took time to make my presence known in the first relationship I held with a student organization due to changes in leadership. I was concerned that I may have jeopardized my relationship with the organization and other students because of a staff position I took at the university. The intent was to “immerse” myself in the setting by obtaining a staff position; however, I recognized that some students had not fully trusted the administrators I worked under in light of institutional politics, Black exceptionalism, and politics of respectability. In the staff position, I witnessed tensions between Black students and CU Boulder administrators, which included some Black administrators.

At the time of participant observation, I was involved with a united conglomeration of campus organizers representing various groups, and who called for reallocated funds from the university police’s multi-million-dollar budget to improve mental health services, antiracism training, and Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) student programs and resources on campus. I was also a member of a grassroots group of students and staff wanting to radically change CU Boulder and the larger community, and care for one another as students, staff, and faculty who had been harmed by the institution. Lastly, I was a team member and mentor for a community building program for Black students, faculty, and staff, whose hope was to create a sustainable community for Black students attending and transitioning to CU Boulder in efforts to provide support while navigating the academy. In addition to meeting students through my academic, staff, and organizing roles, I worked on building relationships with Black students in non-Black Greek-letter organizations, the athletics department, and those majoring in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) fields.

Methodologically, being an organizer and researcher held challenges for me; challenges that scholars rarely discuss openly. There were times in which I felt that I was too “close” to organizing to conduct sound research, being pulled in by the force of social justice work and the life of organizing for a more equitable future. I would follow these feelings with the reminder that Black feminist scholarship argues that no research is objective and rejects the notion that someone could be too close to their work (Hull et al., 1982; Ladson-Billings, 2000; Wing, 2000, 2003; Chilisa, 2019; Evans-Winters, 2019; Esposito and Evans-Winters, 2021).

Student narrators

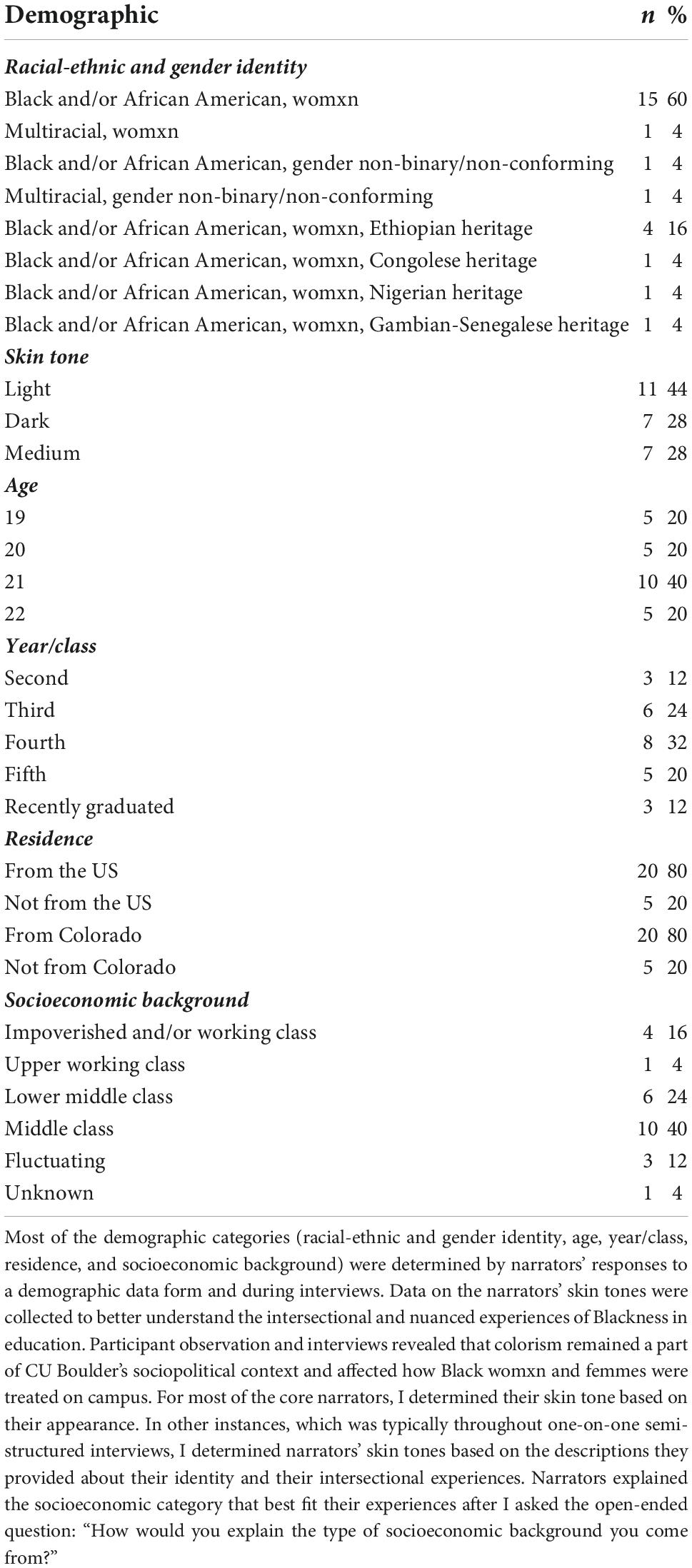

Using purposeful sampling technique (Patton, 1990; Esposito and Evans-Winters, 2021), I observed approximately 80 undergraduate students of various gender identities during participant observation; nine Black womxn and femmes participated in exploratory focus group interviews to inform this study; and twenty-five core narrators participated in one-on-one interviews and are the foci of this research article (n = 25). These core narrators racially identified Black, African American, and/or other terms for the African diaspora; had a womxn and/or femme gender identity; were between the ages of 19 and 22; and were in their second, third, fourth, or fifth year of undergraduate studies at CU Boulder, or had graduated within the past academic year. The 25 core narrators completed a demographic survey that gathered information on their age, academic year/class, major(s) and minor(s), the amount of time they had lived in Colorado, and their racial and ethnic identities. Table 1 provides demographic information about the 25 Black womxn and femmes that participated in one-on-one interviews, such as their racial-ethnic identity, gender identity, skin tone, age, academic year/class, residence, and socioeconomic background.

Table 1. Demographics of narrators from one-on-one interviews with Black womxn and femme undergraduate students: Racial-ethnic and gender identity, skin tone, age, year/class, residence, and socioeconomic background.

Study site: The University of Colorado Boulder

Colorado appointed Boulder City as the city to house the first state university in 1872. Four years and one constructed building later, CU Boulder was founded in 1876 during the same year that Colorado became a state. CU Boulder is now the flagship institution of the University of Colorado system that includes three additional campuses. CU Boulder is a public Research I institution accredited by the Association of American Universities (University of Colorado Boulder, 2022). Guardians send their children to CU Boulder under the pretenses that the university is a prominent public teaching and research institution. CU Boulder’s overall student population is wealthy, making up the second most affluent student population amongst selective higher education institutions in the US with a median family income of $133,700 (The Upshot, 2017). Approximately 1.2% of undergraduate students come from an impoverished background, whereas almost 60% of undergraduate students come from families who are in the top 20% of income earners in the US (The Upshot, 2017).

During the fall 2019 semester, 703 Black undergraduate students enrolled at CU Boulder. At the time of the study, Black students accounted for only 2.6% of CU Boulder’s undergraduate population and this proportion had not increased since 2010, although white and Latinx student populations had grown since 2016 (University of Colorado System Office of Institutional Research, 2020; University of Colorado Boulder IR – Profile, 2021). Of the Black undergraduate students attending CU Boulder, 35.4% were first generation, 42.5% received institutional financial aid, 74.1% paid in-state tuition as Colorado residents, and 44% identified as womxn and 56% men. One hundred and thirty-five Black undergraduate first-year students enrolled for the 2019 fall semester, and African American students’ one-year retention rates declined between 2014 and 2018 (University of Colorado System Office of Institutional Research, 2020; University of Colorado Boulder IR – Profile, 2021).

A 2014 campus climate survey showed that Black students feel less welcome, valued, and supported than the rest of the CU Boulder student population.2 Findings indicated that Black students felt less intellectually stimulated at the institution and were not as proud to attend the institution when compared to the overall student population. CU Boulder’s Black student population was less likely to perceive CU Boulder as diverse. Black students reported experiencing more microaggressions on campus than the rest of the student population as well. Additionally, Black students were less likely to report a sense of community and less likely to report that they have made friends at the institution. In the classroom, Black students expressed that instructors tolerate the use of stereotypes, prejudicial comments, or ethnic, racial, and sexual slurs or jokes. Black students were less likely to feel that instructors help students to understand the different perspectives of diverse cultures and social groups as well. Lastly, Black students were less likely to feel that instructors successfully manage discussions about sensitive or difficult topics, treat students with respect when they voiced positions or opinions, and provide a supportive classroom environment in other ways.

I specifically name—or call out—CU Boulder as the study site to hold the institution accountable for its role in allowing anti-Black gendered racism to permeate through its campus culture, policy, and praxis. The current study appertains to Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ techniques of resistance coping, which may empower us to continue surviving or provide us hope. Yet, we must not lose sight of the structural issues that Black womxn and femme undergraduates must survive. I openly identify and name the higher education institution in which this study is set so that we recognize the localized herstory of anti-Black gendered racism, and to subject CU Boulder to retribution for its prolonged mistreatment of Black womxn and femme undergraduate students.

Data collection

The 14-month study used three different tools of data collection: (1) semi-structured one-on-one interviews; (2) semi-structured group interviews; and (3) participant observation. I heavily draw on the one-on-one interviews in the forthcoming analysis; however, group interviews and participant observation informed how I conducted these interviews, the questions I asked, and how I analyzed the local context of CU Boulder.

I conducted in-depth, one-on-one interviews with 25 core narrators who racially identified as African American, or Black, womxn and/or femmes. The purpose of in-depth, one-on-one interviews is to gain an understanding of narrators’ realities with gendered racism and coping outside of the influence of other narrators (e.g., group interviews), and to allow time and space for more detailed questions. The one-on-one interviews encouraged narrators to determine their own narratives with race and gender through a reflective process of storytelling. By telling their stories, narrators “talk back” (hooks, 1989) to systems of oppression diminishing their wellbeing and exercise a sense of agency by speaking about their coping strategies. I asked narrators open-ended questions about stressors they encounter as a CU Boulder student, the impact of these stressors on their wellbeing, how they cope with such stressors, and the impact of their coping strategies on their wellbeing.

In addition, I conducted two semi-structured focus group interviews with seven sophomores, juniors, and seniors during the Spring 2020 semester to engage them in reflecting on their perceptions of CU Boulder, wellbeing, derogatory and favorable experiences at CU Boulder, and how they cope with such experiences. I also conducted a semi-structured group interview with two self-identified African American undergraduate first-year women to triangulate focus group data.3

As a participant observer, I spent one to two hours a week observing any number of African American students engaging in spaces and meetings (both in-person and online) pertaining to their experiences on campus. During participant observation, I paid attention to collective dialogues, behaviors, and interactions between narrators, non-African American students, faculty, staff, and campus community members.

Data analysis

I conducted open coding for descriptive themes both inductively and deductively (Emerson et al., 1995; Maxwell, 2013; Ravitch and Riggan, 2017; Esposito and Evans-Winters, 2021). I used transcriptions and memos from fieldnotes to meticulously review narratives several times to better gain context of the narrator accounts, discover commonalities in content, and create substantive/descriptive themes found in the data. My analysis became more methodical, employing an iterative process. Using this iterative process, I checked the coding scheme and modified codes as new themes emerged, then compared and condensed substantive/descriptive codes.

I conducted theoretical coding to connect themes found in the collected data with my conceptual framework and scholarly framing. I identified how Blackness and being, Black feminist thought and epistemology, and Black womxn’s coping techniques play out in narrators’ lives. Furthermore, I used intersectional qualitative research methods (Evans-Winters, 2019; Esposito and Evans-Winters, 2021) to analyze commonalities between Black womxn’s and femmes’ lives on campus, but to also expose the nuances and contentions in their perceptions of CU Boulder and their experiences of coping with gendered racism. Data collection and analysis were successful as the study had sufficient data to logically code for themes regarding Black womxn and femme undergraduate experiences at CU Boulder.

Findings

Resistance coping is “the process of confronting the perpetrators of a discriminatory behavior” (Szymanski and Lewis, 2016, p. 231). I conceptualize resistance coping as processes of addressing and challenging gendered racism by attempting to rectify oppressive systems at micro and macro levels, and/or adapting emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses within the context of anti-Black gendered racism’s impact on wellbeing. Black womxn and femme undergraduates at CU Boulder survived by using self-education, direct confrontation, and humor to cope with anti-Black gendered racism.

To supplement the presented findings, it is important to note that narrators’ perceptions on the uniqueness of anti-Black gendered racism differed throughout this study. Most narrators argued that anti-Blackness at CU Boulder was more intense than in other spaces they had experienced it, including other higher education institutions, due to Boulder City’s colonially historic mistreatment of Black people. In fact, participant observation interactions, additional exploratory interviews with alumni, and narrative accounts from Black womxn alumna (McLean, 2002) illustrate that Black women and femme undergraduates faced anti-Blackness throughout the years. Other narrators expressed that the campus represented a microcosm of anti-Blackness against Black womxn and femmes en masse. While the current study is unique to a university in Colorado, the ways in which Black womxn and femme undergraduates cope with anti-Black gendered racism persists in every college and university due to the noxious persistence of anti-Black gendered racism in the academy. The findings from this study push us to not only recognize how Black womxn and femme students live out resistance coping, but to also pinpoint anti-Black settler colonialism as the background plaguing the very campuses that Black femmes must survive overall. This study transpires as an example localized to CU Boulder.

“It’s weird to say that I love learning about systems of oppression because they absolutely suck”: Self-education as resistance coping

Coping through education and advocacy is “the process of increasing self and other’s awareness of discrimination and implementing advocacy efforts to fight discrimination at micro- and macro-levels” (Szymanski and Lewis, 2016, p. 231). I define education and advocacy as processes of informing the self and others about the impact and functionality of systems of power in order to navigate anti-Black spaces, combat oppression, and empower the self and others through advocacy. Throughout the study, Black womxn and femme undergraduate narrators demonstrated education and advocacy coping at CU Boulder. I present how Black womxn and femme undergraduate student narrators educated themselves as a resistance coping strategy henceforth.

Narrators educated themselves using various methods, such as dissociating from stressors and using their access to academic content as college students. For example, Octavia, a 22 year-old fifth-year student, said that she selected “very specific classes about writing and liberation. And so, I’ve got to meet professors that have opened my mind so much to the entire universe, including race relations.” Similarly, Ayanna engaged in schoolwork when she was stressed:

Weirdly enough, if I get stressed by things that aren’t school related, I [turn] to school. I make sure that I have [that] one aspect of my life. I’ll figure it out. Maybe I’ll do some extra credit or something. Or I’ll read. Sometimes professors will have assigned reading and then maybe recommended reading. So I’ll read a recommended reading and immerse myself in this very dense, scholarly articulation of the world’s problems, and theory. It allows me to detach from some of the things that are happening in my personal life. And I can go super meta. It’s very strange. I don’t get overwhelmed by that, taking it in.

As Ayanna illustrated, Black womxn and femme narrators used their academic work to “detach” from stressors in their personal lives by delving into professors’ recommended reading lists and engaging with high theorizations of the world. Narrators mentioned several books that they were reading—whether assigned or suggested by their teachers, or on their own fruition—in order to cope with anti-Black gendered racism. These texts included Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates (2015), White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism by Robin DiAngelo (2018), The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism by Jemar Tisby (2019), and the infamous This Will Be My Undoing: Living at the Intersection of Black, Female, and Feminist in (White) America by Morgan Jerkins (2018).

Narrators contended that they engaged such thought provoking and timely texts because they were inspired by the Black Lives Matter Movement, the sociopolitical climate of 2020, and because they learned more about their place in the world as Black womxn and femmes. According to Inez, a 21-year-old fourth-year student, learning about how gendered racism functioned made her “feel better” because she understood the “history and background” of power and oppression. Inez also explained that taking Ethnic Studies courses at CU Boulder was “affirming and validating” to her experiences throughout life, as they provided her the “vocabulary” to conceptualize how she had been treated by others, and sometimes complacent, in predominantly white spaces.

Knowing about power and oppression as an educational coping strategy remained a prevalent theme. While some narrators educated themselves to better conceptualize how systems of oppression impacted their daily lives, others used it as an opportunity to connect with likeminded people on campus. Milan explained that taking Ethnic Studies courses with her friends and colleagues connected her with compatible colleagues because they validated one another and saw their lives reflected in the academic content. Milan stated that taking her Ethnic Studies courses with friends helped them to:

… connect what we’re learning academically to our own personal lives. It’s helpful to talk that out with somebody who knows the authors that I’m talking about, the texts that we’ve read, the conversations we’ve had in and out of class.

In a like manner, Ayanna mentioned that she had met people who were just as curious as she about systems of oppression and had “in depth discussions and examinations” of the world with them. Ayanna talked about why she was interested in learning about power and oppression as well:

It’s weird to say that I love learning about systems of oppression because they absolutely suck. And they’re the worst aspect of humanity. Like, why can’t we get this shit right? But it’s rewarding in a way. The impact is not all negative because the positive impact on my wellbeing is that I’m better equipped with strategies and coping mechanisms, like talking about it and being able to articulate it. [Learning about systems of oppression] better prepares you for more of the same.

Ayanna’s narrative exemplifies that self-education positively affected her wellbeing in that she connected with others and gained tools for future coping skills. She also found joy in having the ability to “articulate” and expound on the topics she learned about. Other narrators provided specific examples of why they engaged in self-education, like Monica, who used it to prepare for pushback when she politically advocated on social justice issues. Monica shared,

I would research and write, take down notes, because I’ve always been in environments where people at times don’t accept your statements and always want to challenge it. And so I always came prepared for whatever stance was taken, whatever stance I take, whether they speak or not, that I was knowledgeable about it.

As found in interviews and participant observation, Black womxn and femme college student narrators were often silenced at CU Boulder. This was particularly the case when directly confronting and advocating for social equity on campus. Monica’s narrative highlights that she dealt—or coped—with the silencing of Black womxn and femmes by learning from past experiences of having her “stance” challenged and educating herself in preparation.

Self-education also helped narrators who were student organizers cope with gendered racism because it gave a sense of purpose and time to nurture themselves. Milan, who spoke openly about the disadvantages of organizing and activism, mentioned that engaging in self-education led her to feel “purposeful.” When I asked Milan to further explain her thoughts, she stated,

Oftentimes, it feels like what I’m doing is not enough, whether protesting isn’t enough or the policy work isn’t enough. Because nothing has happened after that. Sometimes I feel like I need to do more and be more…. It feels like at the end of the day, nothing is left, almost. Even my friends, who have been on the front lines right now protesting, come home and it’s like, “Damn. I hope that was for something.” Like, “We went through all this traumatizing stuff for what?” But through my academics and in my writing, it feels like I’m doing something for myself, instead of constantly fighting for the community and constantly fighting for my people as a whole. Because, yes, that’s what I love to do, but I need to also tend to myself because my mental health is also very important. And it is often overlooked, or it gets lost in the movement, it gets lost [while] constantly working, and constantly going from classes to meetings to work. Academics has taught me that we need to take a step back. And I’m trying to – I’ve been trying to – implement that in my life.

Milan’s narrative testifies to her and her peers questioning if the labor they had committed to activism and policy work would implement social change. Given the fungible status of Black womxn and femme undergraduate students (Luney, 2021b), the university’s abuse of their labor (Dancy et al., 2018; Luney, 2021b), and keeping up with work and academics, student activist narrators such as Milan became apprehensive of the benefits of organizing. Furthermore, Milan understood her writing and academics to be “purposeful” in that they taught Milan to “take a step back” from the bustling life of class, meetings, and “the movement,” creating time for her to focus on improving her mental health and wellbeing.

“I slander them actively…. It’s not that passive shit”: Direct confrontation as resistance coping strategy

Previous scholarship lists confrontation, community organizing, and student activism as types of resistance coping (Lewis et al., 2013; Szymanski and Lewis, 2016; Burton, 2017). Narrators in the study shared stories about directly confronting assailant in their everyday lives, and the resultant impact on their wellness.

Narrators demonstrated resistance coping techniques through direct confrontation with aggressors, such as racists, sexists, homophobes, elitists, and misogynoirists. When discussing her strategies of direct confrontation, Meg, a 21-year-old fourth-year student, reasoned that she prefers to directly speak with people when racially gendered stressors arose, stating, “I’m very big on ‘We are not going to drive this [issue] for weeks and weeks and weeks’ because I [do] not have that kind of time. I don’t have time.” Emphasizing that she did not “have time” to participate in drawn-out conversations with aggressors was reflected in the labor that Black womxn and femme students faced—like work study and creating political change—in addition to carrying the hardships of anti-Black gendered racism from the campus community. Angela, a 22-year-old fifth-year student, also preferred to directly confront adversaries. During our one-on-one interview, they spoke about practicing pettiness for this process:

Angela: I get on some petty shit. If someone says something racist to me, I’m like, “What?!” Petty! I slander them actively.

LeAnna: You said you slander them actively?

Angela: Yeah.

LeAnna: Is that what pettiness is? Is that how we define it?

Angela: Yeah. It’s an active slander. ‘Cause it’s not that passive shit. I’m like, “That person’s a fucking racist. That one right there. They say racist shit to people.” I know sometimes, when it’s lightly racist shit I’m like, “This is problematic.”

For Angela, direct confrontation as a form of resistance coping emerged as pettiness, or the idea of exaggerating or overemphasizing what others might consider miniscule to accentuate points of an argument, actions or behaviors, ideas, or attitudes. Based on our interview conversation and working on social equity initiatives with them on campus during participant observation, Angela’s actions to “actively slander” and to be “petty” called out racists and problematized “lightly” racist actions while informing other minoritized people of potential harm.

At times, campus community members retaliated against narrators when they challenged them for perpetuating anti-Black gendered racism. Angela’s direct confrontation—and radical honesty—often sparked controversy and criticism from people on campus. After telling me a story about how they were reprimanded for confronting a Latina colleague at a summer program for using the N-word, Angela explained their initial coping response, saying:

I feel like whenever it happens, I just disconnect for a little bit. ‘Cause I can’t fight people anymore. ‘Cause every time I would fight people, I would get threatened by going to OIEC [Office of Institutional Equity and Compliance].

In instances involving retaliation to direct confrontation, Angela used disconnection and boundaries (Luney, 2021b). Due to the backlash that people gave Angela, they decided that confronting people would create penalty from the public, and the OIEC in particular, so they began creating spaces and groups with and for marginalized people to empower, validate, and inform one another. Angela further complicated the strategy of coping through direct confrontation and why they received pushback when calling out others:

With violence and Black bodies and aggression, that’s how I know I’m Black. ‘Cause sometimes I’ll say some shit and then magically it’s like, “Oh, so you’re aggressive.” It’s like, “No,” because when I try to tell you in your language, when I try to tell you calmly, when I try to tell you that’s fucked up, you did not listen. And clearly if I don’t fucking drag you, you’re going to be on some fuck shit. And so it’s petty, but it’s also like “Nah, I’ll be up in your face.”

Worth noting is Angela’s explanation of why they were obligated to engage direct confrontation as a type of resistance coping. They pinpointed a crucial aspect of what it means to be a Black femme, which is that others expected them to express their concerns “calmly” and to accept being silenced, or to be categorized as “aggressive” once they became “petty.” These expectations are based on the Angry Black Woman myth, a herstorically damaging stereotype of Black womxn and femmes (Collins, 2009; Corbin et al., 2018; Perlow, 2018; Doharty, 2020). Furthermore, this passage expounds on why Angela used direct confrontation to cope with anti-Black gendered racism. As Angela explains, placid reasoning with aggressors may be ineffective in mitigating the damage of anti-Black gendered racism, but that forthright contest draws attention to Angela’s voiced demands for humanity.

“I say that I’m on this journey, writing this anthropological research, on white spaces”: Humor as resistance coping strategy

Scholars have outlined humor as a coping strategy (Carver et al., 1989). Humor is “the production of laughter that results from the observed misfortune and suffering of others and viewed as the ultimate soul cleansing” with undertones and connections to leisure and playfulness (Outley et al., 2020). Moreover, humor is a method of redressing the traumas of anti-Black violence, accentuating “its ability to frame or reframe situations or experiences in ways perceived as being more interesting for the individual” (Outley et al., 2020, p. 2). Throughout my study, narrators resisted aggressors by turning to humor when dealing with stressful events around misogynoir. Angela shared how they employed humor as a form or resistance coping:

Think about so many of the best Black comedians’ jokes and how they address racism. It’s never that they’re like, “This racist white person.” They’re like, “This racist white person said something [racist] and I flamed them.” Because what do you want me to do? You really want me to hit you and confirm the physical aggressiveness that you’re saying I have? ‘Cause, honestly it seems like you prefer I say some shit and embarrass you, because that seems easier for you than getting the shit smacked out of you.

Angela’s narrative accentuates how narrators used humor strategically to navigate stereotypical assertions of “aggressiveness” and other illogical sentiments about their character. As Angela and other students described in their narratives, perpetrators of anti-Black gendered racism left little space for uncensored expression of narrators’ frustrations, bogging them down with stereotypical expectations of aggression. Therefore, humor, such as embarrassing oppressors, was an auspicious form of resistance coping.

Other narrators explained that humor helped them to bear second-hand trauma from witnessing anti-Black racism at CU Boulder. Ayanna, for instance, described how she and her friends, who are also Black, utilized humor to cope with hearing about a white woman from Boulder City calling two Black men students the N-word during the fall 2019 semester:

I was finding myself going to my Black friends in particular, and finding them and finding strength in being around people that really understand the impact. And then also are able to make fun of it in that very nuanced, very specifically Black way. Where it’s like, “We understand what’s going on and we understand that [racism is] hurtful, but also we’re able to tear it down piece by piece through poking at it and prodding at it.”

As Ayanna described, Black students communally used humor to cope with racism on campus by analyzing the inanity of racism on campus through mutual understanding and validation. Moreover, Ayanna’s humor highlights the importance of being in community with other people who “understand the impact” of racism, such as the hurt that racism causes. Ayanna’s and her friends’ humor centers Blackness and speaks to the “nuanced” ways in which it exists.

Octavia also coped using humor. When I asked her how she coped with stressful events around race and gender, she responded,

I have to laugh. I have to laugh because if you don’t laugh at what happened, if you can’t do one of [laughs hardily] those, I think [gendered racism] will eat at you. And so I have to sometimes see the humor in the ignorance, and keep it pushing…. I say that I’m on this journey, writing this anthropological research, on white spaces.

Emphasizing the role of laughter, Octavia’s narrative specifically underscores Black womxn’s and femmes’ satirical aptitudes when surviving gendered racism at CU Boulder. Octavia wittingly reconceived others’ gendered racism against her as “ignorance” and her experience as a Black womxn attending CU Boulder as “anthropological research on white spaces,” despite others’ intentions to sabotage her wellbeing through racially gendered violence. Octavia’s use of humor pushes her to reframe racially gendered stressors, buffering her outlook and wellbeing from anti-Black gendered racism. When she says that she is on the “journey” of “anthropological research” about “white spaces,” Octavia redefines her experiences with misogynoir as one where she plays on the misfortune of white ignorance and makes the situation more interesting by amusingly taking on the role of an anthropological researcher.

Discussion

I must point out the minutiae of Black womxn’s and femmes’ coping through the usage of self-education. Firstly, the overwhelming majority of narrators who described how they coped with anti-Black gendered racism by using education centralized discourses on race, gender, Blackness, power and oppression, and liberation. Many of these narrators named CU Boulder’s Department of Ethnic Studies and Department of Women and Gender Studies when outlining the benefits of educational content that the university provided. The significance of Ethnic Studies and Women and Gender Studies courses in narrators’ self-education journeys is that they provided information for narrators to better understand power and oppression from perspectives similar to their own (Rojas, 2010; Ferguson, 2012; hooks, 2014). Ethnic Studies and Women and Gender Studies courses contributed to narrators’ epistemic production by allowing narrators to theorize about their own realities and prepare for anti-Black gendered racism. In turn, Ethnic Studies and Women and Gender Studies pedagogies empowered narrators as creators of knowledge that is relevant to their lived realities as Black womxn and femmes.

Narrators employing self-education as a coping strategy contributed to a long lineage of Black womxn and femmes finding power in self-education, and particularly when educating oneself in community with likeminded people. From a Black feminist perspective, foremothers, such as members of the Combahee River Collective, contributed, upheld, and bestowed practices of self-education as a method of coping through anti-Black gendered racism in their reading groups and spaces where members acquired the language to understand their lived experiences and compounded identities as African American women (Combahee River Collective, 1977; Taylor, 2018; Khan et al., 2022). Narrators using self-education to cope outside of community found space and time for themselves, especially if they were student activists and organizers. For them, self-education helped to resist and survive the impact of activism, which could surface as doubt for the movement and neglect of wellbeing. Equivalently, Black womxn and femme narrators attending CU Boulder educated themselves to survive anti-Black gendered racism.

The findings demonstrate that retaliation from the campus community and the Angry Black Woman trope (Collins, 2009; Corbin et al., 2018; Perlow, 2018; Doharty, 2020) played a critical role when narrators utilized direct confrontation as a means to cope with gendered anti-Black racism. Regardless of narrators’ gender identity and background, the campus community condemned most narrators who directly confronted racists, sexists, homophobes, elitists, misogynoirists, and others perpetuating anti-Blackness in its various forms. Retaliation involved interpersonal and systemic actions, ranging from threatening to report narrators to university personnel to projecting the Angry Black Woman stereotype onto narrators. The campus community’s retaliation against Black womxn and femme undergraduates exists in contention with—and in reaction to—Black womxn and femmes exercising their humanity by defending themselves, surviving, and simply being. Universities may not perceive retaliation as acts of academic violence against Black womxn and femme undergraduates. Yet, retaliation against Black womxn and femmes occur often (Ahmed, 2021), illustrating a culture of censoring, surveilling, and silencing Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ challenges to the university’s status quo. Retaliation remains a bleak reality of gendered anti-Black racism that the narrators in the study—and their foremothers—coped with.

In critical assessment of their realities as Black womxn and femme college students at a historically and predominantly white university—and confronting, assessing, and recovering from the effects of gendered racism—narrators coping through humor took gendered racism and flipped it on its head. In the words of the beloved writer, feminist, womanist, and activist, Lorde (2020), narrators stomached the “cacophony” of the world’s hate for Black womxn and femmes and transformed it into a “symphony” through humor. Humor played a role in transforming the “cacophony” into a “symphony” for Black womxn and femme narrators at CU Boulder, reframing transgressive acts of gendered racism as absurd and antiquated shots at their humanness. Colloquially speaking, narrators “licked their wounds” through laughter and playfulness, which allowed them to continue living their lives and reinforced their dignity and humanity. Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ humor as a resistance coping mechanism provides further implications on Black being, and Black joy as a means of liberating oneself and others from the impending impacts of anti-Black gendered racism, more specifically.

I hold concern when scholars study Black womxn’s and femme’s coping and survival in higher education institutions, and historically and predominantly white college and universities in particular. This is because of excessive emphasis on Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ actions and behaviors, which we often conflate with solutions to gendered anti-Black racism in educational settings. However, students’ acts of survival through coping are not sustainable methods of ridding college campuses of gendered anti-Blackness for two reasons. Foremost, the focus on Black womxn and femme survival as a method to improve racially gendered experiences is a distraction that excuses higher education institutions from redressing the harm against Black femme bodies they allow to persist. This also diverts us from holding higher education institutions accountable for creating and implementing solutions to gendered anti-Blackness at systemic levels. Secondly, the sensationalism of coping and survival neglects the strife that Black womxn and femme undergraduates endure during the process of coping with gendered anti-Black racism—which requires arduous labor mentally, emotionally, physically, academically, and socially—and allows it to fester for generations.

My intent here is not to belittle the significance of the resistance coping strategies that Black womxn and femmes use in their daily lives at historically and predominantly white institutions. Instead, I hope to call attention to the university’s failure to acknowledge fault and rectify gendered anti-Black racism, often leaving Black womxn and femme undergraduates to fend for themselves when facing burdens that are not of their own volition, but of white supremacy’s. Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ methods of coping and survival demonstrate Black youth claiming their humanity and dignity, finding ways to matter within educational settings that have devalued and demeaned us throughout time. It is up to historically and predominantly white universities to recognize and value Black womxn and femme undergraduates’ coping strategies for what they are—human acts of surviving gendered anti-Blackness. Until colleges, universities, and society at large renounce white supremacy, they should provide resources for Black womxn and femme undergraduates that mirror their survival and being in higher education, at the very least.

Recommendations: Transformative justice, trusts, longitudinal data collection, and critical curriculum

It is pertinent to understand that today’s colleges and universities are white supremacist institutions of the colonial state, and that we cannot conduct transformative justice in higher education without delinking from the colonial state (Carney, 1999; Dancy et al., 2018; Perlow, 2018; Lorde, 2020). For this reason, I call higher education personnel to rely on a transformative justice framework. This might encourage us to acknowledge that although colleges and universities remain unprepared to conduct true transformative justice, we should continue striving to change higher education systems perpetuating anti-Black gendered racism. Transformative justice is preventative, meaning that it brings the source of harm and violence to the surface so that we create solutions in community and without interference from the colonial state. Within the context of Black womxn and femme undergraduate coping, transformative justice allows us to understand the underlying conditions of anti-Black gendered racism, holding individuals and institutions accountable for the ways that we contribute to gendered anti-Blackness. Most importantly, a transformative justice framework allows us to uproot and mitigate anti-Black gendered racism without causing more violence in the process when applied to everyday praxis (Gready and Robins, 2014; Cullors, 2018; Stein, 2018; Kim, 2021).

Additionally, I urge colleges and universities to create and sustain monetary trusts for educational and social programming for Black womxn and femme undergraduates. In juxtaposition to grants for program development, a trust or endowment might garner buy in from the campus community and ensure that institutions secure monies reserved for exclusively Black womxn and femme spaces. Stipulations for trusts should be set by former and current Black womxn and femme undergraduates and their campus community partnerships. Building these types of trusts require higher education administrations to divest from university entities that uphold white supremacy (e.g., the prison industrial complex) in order to reallocate funds to programming exclusive to Black womxn and femmes.

Thirdly, I advocate for longitudinal data collection on Black womxn and femme experiences with gendered anti-Blackness at historically and predominantly white colleges and universities. Although these studies do not have to capture resistance coping particularly, they should include implications on what it means for Black womxn and femmes to be. Because our being involves political resistance (Davis, 1972; Combahee River Collective, 1977; Crenshaw, 1990; Collins, 2009), a longitudinal approach would illustrate higher education’s history of mistreating Black womxn and femmes. A longitudinal approach would also demonstrate the ways in which our antecessors survived, empowering us to do the same at historically and predominantly white educational institutions or institutions created for us and by us. We must involve personal and counter narratives, oral herstory, and storytelling (Wing, 2000; Pratt-Clarke, 2012) in longitudinal data collection on Black womxn’s and femmes’ experiences in the university to further critical implications about being for Black womxn and femme undergraduates.

Lastly, I recommend that colleges and universities offer Africana Studies, Ethnic Studies, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies courses to students regardless of their academic track. Colleges and universities must develop and provide—not merely offer—courses that aid in students’ critical consciousness raising so that Black womxn and femmes do not have to seek content on their own. Courses and curriculum should be developed by persons with experience facilitating unorthodox pedagogies, including students (undergraduate and graduate) and community leaders. This may foster reading groups and spaces where Black womxn and femme undergraduates build community with one another while learning techniques for analyzing and navigating their racially gendered experiences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, University of Colorado Boulder. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author conceptualized, designed, conducted, and analyzed this research and wrote, revised, and finalized the manuscript.

Funding

This research project was partially funded by the Department of Ethnic Studies, University of Colorado Boulder.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the narrators who contributed to this study.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Black feminist thought and epistemology, as theory, centers cisgender womxn. As such, I solely refer to cisgendered womxn throughout this section. My application of the conceptual framework and analysis incorporates gender non-conforming/gender queer femmes throughout the remainder of the article.

- ^ This campus climate survey was distributed every four years since 1994 but skipped in 2018 because of a university system wide campus climate survey distributed in November of 2019. An official report of 2019 campus findings were to be released in 2020, but CU Boulder’s Office of Data Analytics did not conduct a climate survey at the university-level, opting instead to conduct the survey in select research institutes and social science departments. I was unsuccessful in obtaining CU Boulder’s most updated campus climate statistics on research institutes and social science departments from the Office of Data Analytics because the aggregate data had not been compiled nor anonymized for public access at the time of writing and publishing this article.

- ^ Including first-year student perspectives helped to understand how African American first-year perspectives and coping strategies compare to those of upper-class students. Having these experiences provide a point of triangulation (Mathison, 1988), and comparatively allows me to observe the development of African American college students’ coping strategies and how they understand their experiences as they matriculate through CU Boulder.

References

Armitage, S. (2008). “The mountains were free and we loved them: Dr. Ruth Flowers of Boulder, Colorado,” in African American Women Confront the West, 1600-2000, ed. Q. Taylor (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press), 165–177.

Bailey, M., and Trudy. (2018). On misogynoir: Citation, erasure, and plagiarism. Fem. Media Stud. 18, 762–768. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2018.1447395

Bartman, C. C. (2015). African American women in higher education: Issues and support strategies. College Student Affairs Leadership 2:5.

Bignold, W., and Su, F. (2013). The role of the narrator in narrative inquiry in education: Construction and co-construction in two case studies. Int. J. Res. Method Educ. 36, 400–414. doi: 10.1080/1743727X.2013.773508

Bilge, S. (2020). The fungibility of intersectionality: An Afropessimist reading. Ethn. Racial Stud. 43, 2298–2326. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2020.1740289

Blackmon, S. M., Coyle, L. D., Davenport, S., Owens, A. C., and Sparrow, C. (2016). Linking racial-ethnic socialization to culture and race-specific coping among African American college students. J. Black Psychol. 42, 549–576. doi: 10.1177/0095798415617865

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2006). Racism Without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in the United States. Washington, DC: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. Am. Behav. Sci. 59, 1358–1376. doi: 10.1177/0002764215586826

Bonilla-Silva, E., and Dietrich, D. (2011). The sweet enchantment of color-blind racism in Obamerica. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. 634, 190–206. doi: 10.1177/0002716210389702

Burton, W. M. (2017). Coping at the Intersection: A Transformative Mixed Methods Study of Gendered Racism as a Root Cause of Mental Health Challenges in Black College Women. Bethesda, MD: ProQuest.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., and Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 65, 375–390. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.375

Chambers, C. R., and Sulé, V. T. (2022). “For colored girls who have considered suicide when the tenure track got too rough,” in Building mentorship networks to support black women (Milton Park: Routledge), 121–135. doi: 10.4324/9781003147183-11

Coll, C. G., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., et al. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Dev. 67, 1891–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01834.x

Collins, J. (2022). Othermothering by African American Women in Higher Education at Predominantly White Institutions: How the Practice Affects Their Professional and Personal Lives, Ph.D thesis, Chicago, IL: DePaul University.

Collins, P. H. (1986). Learning from the outsider within: The sociological significance of Black feminist thought. Soc. Prob. 33, s14–s32. doi: 10.1525/sp.1986.33.6.03a00020

Collins, P. H. (1999). Reflections on the outsider within. J. Career Dev. 26, 85–88. doi: 10.1177/089484539902600107

Collins, P. H. (2004). “Toward an afrocentric feminist epistemology,” in Turning points in qualitative research: Tying knots in a handkerchief (London: Routledge), 47–72.

Collins, P. H. (2009). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Milton Park: Routledge.

Combahee River Collective. (1977). “A Black feminist statement,” in How we get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, ed. K.-Y. Taylor (Chicago: Haymarket Books), 15–27.

Corbin, N. A., Smith, W. A., and Garcia, J. R. (2018). Trapped between justified anger and being the strong Black woman: Black college women coping with racial battle fatigue at historically and predominantly White institutions. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 31, 626–643. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2018.1468045

Crenshaw, K. (1990). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan. Law Rev. 43:1241. doi: 10.2307/1229039

Cullors, P. (2018). When They Call you a Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Daly, A., Jennings, J., Beckett, J. O., and Leashore, B. R. (1995). Effective coping strategies of African Americans. Soc. Work 40, 240–248. doi: 10.1093/sw/40.2.240

Dancy, T. E., Edwards, K. T., and Earl Davis, J. (2018). Historically white universities and plantation politics: Anti-Blackness and higher education in the Black lives matter era. Urban Educ. 53, 176–195. doi: 10.1177/0042085918754328

Davis, A. (1972). Reflections on the Black woman’s role in the community of slaves. Mass Rev. 13, 81–100.

DiAngelo, R. (2018). White Fragility: Why it’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism. Boston: Beacon Press.

Doharty, N. (2020). The ‘angry Black woman’as intellectual bondage: Being strategically emotional on the academic plantation. Race Ethn. Educ. 23, 548–562. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2019.1679751

Dotson, K. (2015). Inheriting Patricia Hill Collins’s black feminist epistemology. Ethn. Racial Stud. 38, 2322–2328. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1058496

Emerson, R. M., Fretz, R. I., and Shaw, L. L. (1995). Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, 2nd Edn. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226206851.001.0001

Esposito, J., and Evans-Winters, V. (2021). Introduction to Intersectional Qualitative Research. Thousand Oak: SAGE.

Evans-Winters, V. (2019). Black Feminism in Qualitative Inquiry: A Mosaic for Writing our Daughter’s Body (Futures of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research). Milton Park: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781351046077

Ferguson, R. A. (2012). The Reorder of Things: The Iniversity and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. doi: 10.5749/minnesota/9780816672783.001.0001

Garrett, S. D., and Thurman, N. T. (2018). “Finding fit as an “outsider within,” in Debunking the Myth of Job fit in Higher Education and Student Affairs, eds B. J. Reece, V. T. Tran, E. N. DeVore, and G. Porcaro (Frisco: Style Publishing, LLC), 119–146.

Gines, K. T., Ranjbar, A. M., O’Byrn, E., Ewara, E., and Paris, W. (2018). “Teaching and learning philosophical “special” topics: Black feminism and intersectionality,” in Black Women’s Liberatory Pedagogies, (eds) O. Perlow, D. Wheeler, S. Bethea, and B. Scott (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 143–158. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-65789-9_8

Gready, P., and Robins, S. (2014). From transitional to transformative justice: A new agenda for practice. Int. J. Trans. Justice 8, 339–361. doi: 10.1093/ijtj/iju013

Green, C. E., and King, V. G. (2001). Sisters mentoring sisters: Africentric leadership development for Black women in the academy. J. Negro Educ. 70, 156–165. doi: 10.2307/3211207

Griffin, K. A. (2013). Voices of the “Othermothers”: Reconsidering Black professors’ relationships with Black students as a form of social exchange. J. Negro Educ. 82, 169–183. doi: 10.7709/jnegroeducation.82.2.0169

Hartman, S. V. (1997). Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hartman, S. V. (2007). Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Harushimana, I. (2022). “Retained by the grace of sisterhood: The making of an african woman academic in US academia,” in Building mentorship networks to support black women (Milton Park: Routledge), 136–150. doi: 10.4324/9781003147183-12

Hays, D. M. (2010). “A quiet campaign of education”: Equal rights at the University of Colorado, 1930–1941,” in Enduring Legacies: Ethnic Histories and Cultures of Colorado, eds A. J. Aldama, E. Facio, and D. Maeda (Boulder: University of Colorado Press), 96–110.