- 1Saint Louis University, Baguio City, Philippines

- 2Walailak University, Thai Buri, Thailand

While a number of studies have previously conceptualized hybrid teaching, often used interchangeably with blended learning during the pre-COVID19 pandemic, hybrid teaching has been undertheorized and unexplored during and post-COVID19 pandemic when schools have slowly opened their classrooms for students. This paper explores the concept of hybrid teaching (also referred to as hybrid classroom instruction and hybrid learning) and how such teaching methodology is different from blended learning, fully online, and remote teaching by presenting a teacher’s practice during the COVID19 pandemic. Although our goal is to identify clearly what hybrid teaching is, we do not intend to offer a definite conceptualization and practice of hybrid teaching as teaching is context-dependent. However, we argue that hybrid teaching has the potential to be one of the teaching methodologies in the post COVID19 pandemic education, especially when schools and universities are in the transition back to residential classroom teaching.

Introduction

The COVID19 pandemic has undoubtedly changed the educational landscape in all schools and universities in the world as these schools migrated to online and remote teaching from residential classroom teaching. Studies have reported that while migrating to online teaching, teachers faced issues that challenged their classroom pedagogical practices, doubted their teaching abilities, and questioned the learning outcomes of their students (Ulla and Achivar, 2021; Ulla and Perales, 2021a; Maatuk et al., 2022). Teachers were not prepared to migrate to online and remote teaching, given the lack of training, experience, and orientation in conducting online classes (Chakraborty et al., 2021; Ulla and Perales, 2021b). In addition, migrating to online teaching during the COVID19 pandemic was sudden. Teachers may not have time to redesign their teaching materials, assessments, and other learning resources that contributed to their encountered issues. Other schools may not have a well-designed learning management system (LMS), internet connectivity, and electronic gadgets that teachers and students could utilize during this unprecedented time (Nhu et al., 2019; Ulla and Perales, 2021b).

However, despite these challenges, the COVID19 pandemic has also caught the interest of some education scholars, practitioners, and researchers in innovating the traditional classroom teaching practice to suit the current educational context. Studies have shown the significance of online teaching and learning resources, the provision of electronic devices, online platforms, and various online applications to make online and remote teaching possible and successful. The asynchronous and the synchronous teaching have also become the most crucial teaching modalities, offering choices for teachers and students to continue the teaching and learning process (Moorhouse and Wong, 2022). For instance, teachers utilize popular online platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet as their virtual classrooms where they synchronously meet their students (Kansal et al., 2021). Some teachers may have employed an asynchronous teaching modality where they used online platforms like Facebook, Moodle, and Google classroom for students who may have an intermittent internet connection. In addition, teaching materials have also been modified for online teaching, and teachers employed online applications such as Kahoot, Socrative, Quizlet, and Quizizz to make their online teaching interactive and fun (Sayıner and Ergönül, 2021). In other words, despite the pedagogical challenges that teachers faced in their online teaching, it may be noted that teachers may also have learned from this experience where they became more resourceful, flexible, and creative teachers who were willing to adapt to the changing landscape of education.

With the current situation in education, uncertainties are the only certain, especially since no one knows when this pandemic will end. Neuwirth et al. (2021) mentioned that teaching and education “will not be a return to normal, but rather that it will be a new normal, which will be quite different from anything that we have known before” (p. 143). This suggests that transitioning back to residential classroom teaching may also be challenging, considering parents’ and their students’ doubts about whether they are safe or not to go back to the campus. In other words, although some universities have slowly opened their classrooms back for their students, other parents and their students may not be comfortable and confident just yet to go back to the residential classroom learning. Thus, schools, especially in some higher education institutions (HEIs), may offer a hybrid classroom where teachers and students meet for hybrid teaching and learning. However, although hybrid teaching may not be a new teaching method in education, studies in the literature gave no definite conceptualization and theorization of the concept, as it is often used to refer to blended learning. Such unclear distinction only leaves classroom teachers puzzled about its use, purpose, and meaning, especially during this COVID19 pandemic, when all education institutions may still have no clear guidelines regarding the return to face-to-face classroom instruction.

This article discusses the concept of hybrid teaching in a hybrid classroom by examining relevant studies exploring this concept in the pre and during the COVID19 pandemic and how hybrid teaching is conducted by presenting a teacher’s teaching practice in a university in Thailand. However, our goal is not to give a definite conceptualization of hybrid teaching and teaching practice. We want to contribute to hybrid teaching practice and its theorization through this article based on our teaching context. Thus, this article hopes to shed light on the nuances of the features and practices of hybrid teaching so that education practitioners, scholars, and policymakers will have something to consider when deciding to do hybrid teaching in post COVID19 education.

Defining Hybrid Teaching

Studies in the literature present no clear definition of hybrid teaching, its differences from other modes of lesson delivery (e.g., blended learning), and how such teaching methodology is conducted in the teaching and learning environment, especially during the COVID19 pandemic. In fact, these studies used the concept of hybrid teaching or learning interchangeably with blended learning (O’Byrne and Pytash, 2015; see Klimova and Kacetl, 2015; Solihati and Mulyono, 2017; Smith and Hill, 2019), emphasizing the combination of residential classroom instruction with computer-mediated instruction. For instance, Linder (2017) broadly defined hybrid teaching as a teaching method that integrates technology to provide students with a different learning environment while catering to their learning needs and preferences. Such a definition is similar to Garrison and Kanuka’s (2004) definition of blended learning as “a thoughtful integration of classroom face-to-face learning experiences with online learning experiences” (p. 96). Garrison and Vaughan (2013) emphasized that in blended learning, “learning designs are informed by evidence-based practice and the organic needs of the specific context” (p. 24). This suggests that both hybrid teaching and blended learning primarily consider the needs of the teaching context and that instructional designs are geared toward students’ learning experiences.

Consequently, Oliver and Trigwell (2005), Klimova and Kacetl (2015), and Smith and Hill (2019) acknowledged the complexity and ambiguity of the given definitions of hybrid teaching and blended learning. However, considering the various definitions of the concepts, it can be noted that hybrid teaching and blended learning are grounded on the following essential characteristics: the integration and the combination of the residential classroom teaching with online teaching and learning approaches (Oliver and Trigwell, 2005), the important role of technology in the teaching and learning process (Saichaie, 2020), and the use of class time for asynchronous and synchronous teaching and learning activities (Chen and Chiou, 2014; Linder, 2017; Solihati and Mulyono, 2017; Saichaie, 2020). Furthermore, Saichaie (2020) claimed that despite problematic distinction between these teaching and learning models, they “represent a departure from instructor-centered pedagogies (e.g., lecture) to student-centered pedagogies (e.g., active learning), where the focus is less on instructor delivery of content and more on student application of content (e.g., problem-solving)” (p. 96).

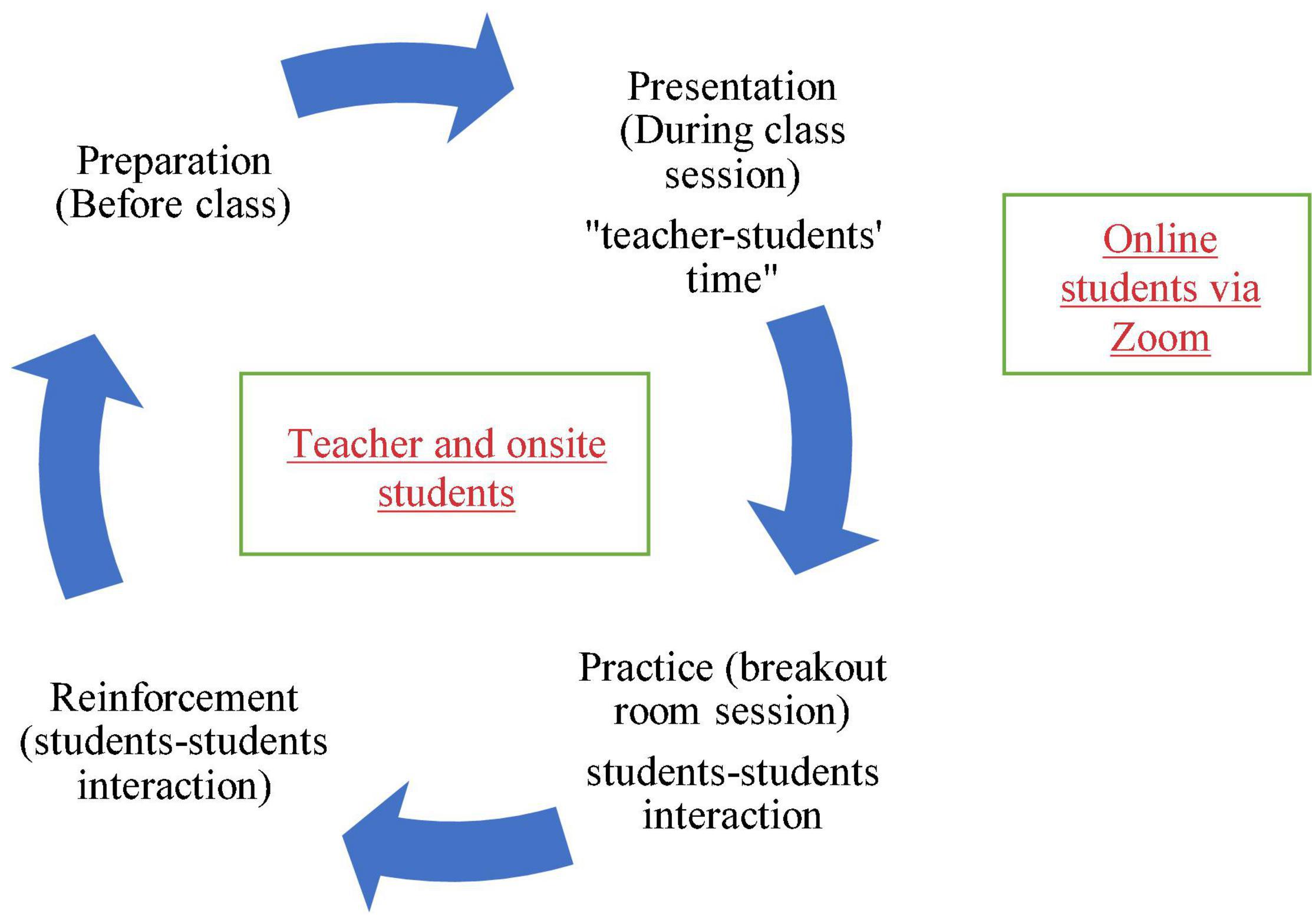

Although this paper aims not to distinguish and elevate one over the other, we defined hybrid teaching (also referred to as hybrid classroom instruction and hybrid learning) as an approach to teaching that not only integrates technology in the teaching process but also combines students who are inside a physical classroom and students from online. In other words, hybrid teaching is synchronous teaching of students in the classroom and online using an online platform, Zoom. Likewise, as a teaching methodology, it addresses students’ learning preferences, especially during the COVID19 pandemic, as students who were inoculated against the virus may choose whether to return to the classroom or continue learning online. Unlike in the fully online classroom, hybrid teaching allows online students to join and engage in various learning discourses with their classmates in the physical classroom through Zoom (see Figure 1).

Moreover, hybrid teaching components are similar to residential classroom teaching and learning since they have the teacher and students’ presence. Also, the lesson’s design is based on the learning outcomes, and activities are aimed at students’ learning (Linder, 2017). However, Saichaie (2020) noted that “class time” is more flexible in hybrid teaching, where one class period is substituted with online or offline activities for students’ active learning. Most importantly, “hybrid courses have significant e-learning activities, including online quizzes and synchronous or asynchronous discussions, in addition to traditional classroom face-to-face teaching and learning (Vernadakis et al., 2011, p. 188).

Hybrid Teaching During the Pre-COVID19 Pandemic

Although a number of empirical studies have explored hybrid teaching, its effectiveness compared to traditional classroom face-to-face teaching (Vernadakis et al., 2011; Chen and Chiou, 2014), teachers’ experiences and perceptions (Drewelow, 2013; Solihati and Mulyono, 2017), and students’ learning achievements and perceptions (Dowling et al., 2003; Lin, 2008), these mainly were conducted before the COVID19 pandemic when electronic communication tools, CD-ROM, and TV were utilized for hybrid teaching, and the use of online conferencing platforms such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Facebook, and Google classroom was not yet popular. For example, Chen and Chiou (2014) investigated the impact of hybrid learning instruction on students’ learning achievement, style, satisfaction, and classroom learning community compared to traditional classroom face-to-face teaching in a university in Taiwan. The teachers designed the hybrid curriculum, where the first eight weeks of instruction were devoted to teachers giving students a face-to-face lecture for both the study group and control group of students. In addition, the e-learning system was used for material posting, online discussion forums, and submission of assignments. In the tenth week, the study group received all the discussion for their final assignment in the e-learning system, while the control group had a face-to-face discussion for their final assignment. While the results revealed that students in the hybrid course had higher learning scores, satisfaction, and a stronger sense of community compared to traditional classroom face-to-face students, hybrid teaching was not implemented simultaneously with online and onsite students. Instead, both groups of students received the same instruction differently, one online and the other face-to-face.

Vernadakis et al. (2011) also conducted a similar study investigating the effectiveness of hybrid learning in delivering a computer science course compared to traditional lecture instruction in a university in Greece. Participants were one hundred seventy-two first-year university students randomly assigned to hybrid lecture instruction and traditional lecture instruction. The hybrid lecture instruction combined the asynchronous learning activities on the internet and traditional learning activities in the classroom. Additionally, the hybrid lecture instruction was designed following a one-three ratio. Two lesson units were conducted using the traditional lecture instruction, and the remaining four units were conducted in a learning management system called the open eClass. Like the findings from the study by Chen and Chiou (2014), the results also pointed out that students in a hybrid lecture instruction had higher scores than those students in the traditional lecture instruction. Although Vernadakis et al. (2011) concluded that hybrid teaching instruction effectively facilitates students’ understanding of planning and remembering factual and conceptual knowledge, it was not conducted simultaneously with students in the classroom and online. The technology integration was done only for asynchronous learning activities.

In Indonesia, Solihati and Mulyono (2017) employed a hybrid classroom instruction in an Indonesian private university and reflected on their experience as teachers of a hybrid classroom. They utilized the Google classroom as a site for their hybrid learning activities and conducted face-to-face instruction to students once a week for 100 min for 12 weeks. Similar to the studies by Chen and Chiou (2014) and Vernadakis et al. (2011), the asynchronous online activities in a hybrid instruction by Solihati and Mulyono were only done to support students’ learning. In other words, hybrid teaching was not implemented in synchronous teaching, where students from onsite and online learned together. However, they recognized the benefits of hybrid teaching as it made the lesson delivery convenient and accessible for students.

Furthermore, positive perceptions regarding hybrid teaching were also common among 15 graduate teaching assistants in a public university in the United States. Drewelow (2013), who also examined teaching assistants’ experiences in a hybrid teaching course, found that teaching assistants believed that a hybrid language class could facilitate student-centered instruction that is important for language acquisition. However, like the previous studies, the hybrid instruction was not implemented following the integration of an online platform where online and onsite students were connected simultaneously for real-time instruction. Instead, as reported by Drewelow, the hybrid instruction also utilized the asynchronous online activities, where students were given 24 h to complete the tasks. Thus, the asynchronous online activities were only made to prepare students for face-to-face instruction, reinforce students’ learning practices, and enhance their reading and writing skills.

Considering how classroom teachers implemented hybrid classroom instruction in different teaching and learning contexts, where there were no online and onsite students learning simultaneously, the present teaching practice adds to the discussion and practice of hybrid teaching, especially in the context of the COVID19 pandemic. Likewise, this article provides a different perspective of how hybrid teaching was conducted in a university in Thailand and pushes forward one basic identifying feature of a hybrid classroom: the presence of students online and onsite. We maintain that a hybrid classroom is identified by utilizing an online platform where online students are connected to engage and participate in the learning discussion with their classmates and teacher in the onsite physical classroom.

Hybrid Teaching: The Teaching Practice

The Teaching Context

Hybrid teaching was conducted in a university in Thailand during the third term of 2020–2021 (January 2022–April 2022) when the COVID19 cases started to decline. Before the end of the second term, the university had announced the shift to hybrid teaching the following term for those students who were willing to come back to the campus. In other words, the university did not compel students to study back in the physical classroom but had given them an option whether to study onsite or online. Health safety protocols were followed (social distancing, vaccination, testing, wearing a mask, and sanitation) to ensure a successful transition to hybrid teaching. However, since there were still a number of students who were not confident to be back on the campus, there were still classes held online since most students preferred to study online.

The second author (the teacher) obtained a degree in English and currently finishing his Master of Arts degree in English language teaching. He has been teaching for almost 5 years already. Moreover, he conducted the hybrid teaching in one of his general English language classes (English for Reading and Writing) with 35 first-year students majoring in Digital Communications. Of these 35, only 12 students were onsite, and 23 were online. The class met once a week for 2 h every Friday from 10 to 12 noon.

The teacher acknowledged that he did not have experience and knowledge in conducting hybrid teaching. He also mentioned that there was no training that the university provided for the teachers on how to do hybrid teaching before the opening of the third semester. However, since this paper aims to present how a teacher perceives and conducts hybrid teaching in a university in Thailand, we believe that by presenting a teacher’s hybrid teaching practice, we could contribute to the conceptualization of hybrid teaching, pushing forward some of the features of a hybrid classroom and highlighting the presence of students online and onsite. Our participant is ideal for the study since he does not know what a hybrid teaching is, and the university offers no training for them on how to conduct hybrid teaching. However, with his experience in conducting an online teaching and a residential classroom teaching and the provision of the technological equipment and platform in the classroom, he could use his pedagogical skills and knowledge to plan and design his hybrid classroom instruction.

The Teaching Practice

Preparation

Before every class session, I had to prepare and create PowerPoint slides for my class. The contents of the slides were taken from our textbook. Sometimes, I had to look for other sources from the internet, especially video clips or listening audio. I also had to ensure that all my language activities worked in the online applications. For example, I used the Socrative application for my vocabulary activities, which was launched during the first 15 min of the class. I also used Google Forms for other language exercises. I needed to prepare all of these online applications before coming to my class so that my hybrid classroom instruction would run smoothly.

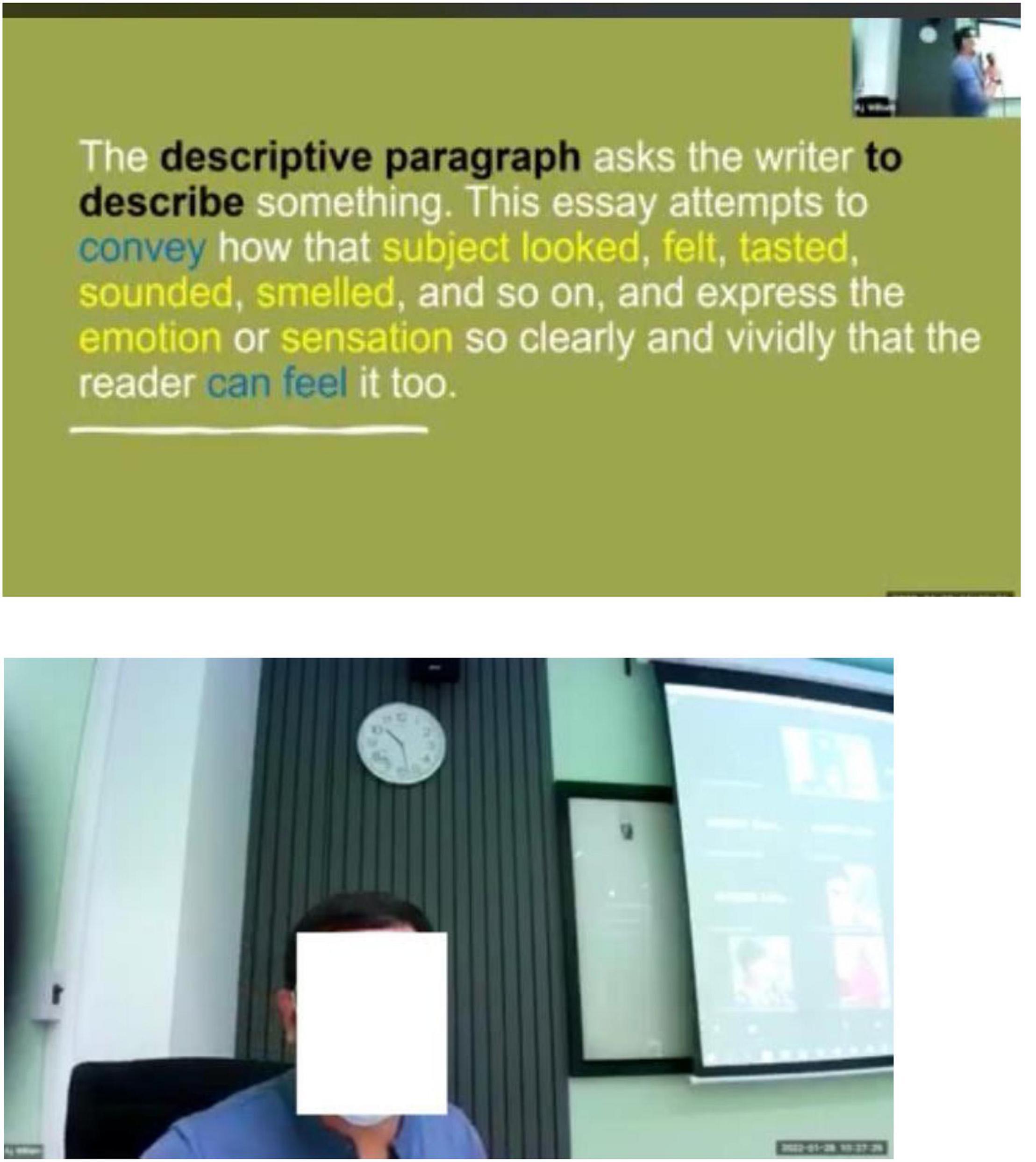

On the day of the class, I had to be in the classroom 15 min before the scheduled time to ensure that all technological equipment was ready and working for my hybrid class. I turned on the classroom air-conditioning, checked the computer, web camera, internet connection, and microphone, and turned on the multimedia projector. I also logged into my google drive, where all the class teaching materials were stored, including the class register, the lesson slides, and online links to my language activities. I then opened them all for easy access when the class started. I also logged into my class Zoom account so that online students can join the class already (see Figure 2).

Presentation

At 10 in the morning, I started the class by checking the class attendance. Next, I launched the online Socrative application for 15 min of vocabulary exercise. I considered this online vocabulary exercise helpful in the hybrid classroom instruction because it has become a common application both for online and onsite students to join the class exercise.

Following the online vocabulary exercise, I proceeded to share my Zoom screen to make my lesson PowerPoint slides visible for onsite and online students. For onsite students, they could see the lesson PowerPoint through a multimedia projector, while online students could see it through the shared Zoom screen. I had to use the microphone so that online students could hear my lesson discussion. Likewise, I had to limit my “teacher time” or lesson discussion to 30 to 45 min so that students could have time to interact, discuss, and share ideas. To check their comprehension, I would call some students either online or onsite to recall what I said.

After my “teacher time,” I would always have a breakout room discussion where students were given a space to engage with each other regarding our lesson. I always had a question or two as their point for discussion. Onsite students could join their online classmates in the breakout rooms or form their groups in the classroom. In case onsite students wanted to join the breakout room discussion with their online classmates, they needed to open their Zoom account and log in to participate. However, some onsite students usually preferred to create one or two groups with their classmates in the classroom.

The breakout session was limited to 30 min only, and students should be back to the main room to share their group discussion with the rest of the class. Students were advised to be creative in their group discussion sharing. They could present their discussion in a PowerPoint or they could do a discussion role-play.

When online students returned to the main room, I facilitated the group sharing discussion by calling some volunteer groups to share first. Otherwise, I let the onsite students share first their group discussions by using the microphone and the web camera facing them so that they would be seen and heard by their online classmates. Online and onsite students were also encouraged to ask questions or supplement the group discussion. The group discussion sharing lasted for 20 to 30 min. Lastly, I gave my students a comprehension exercise either in Socrative or Google form platform.

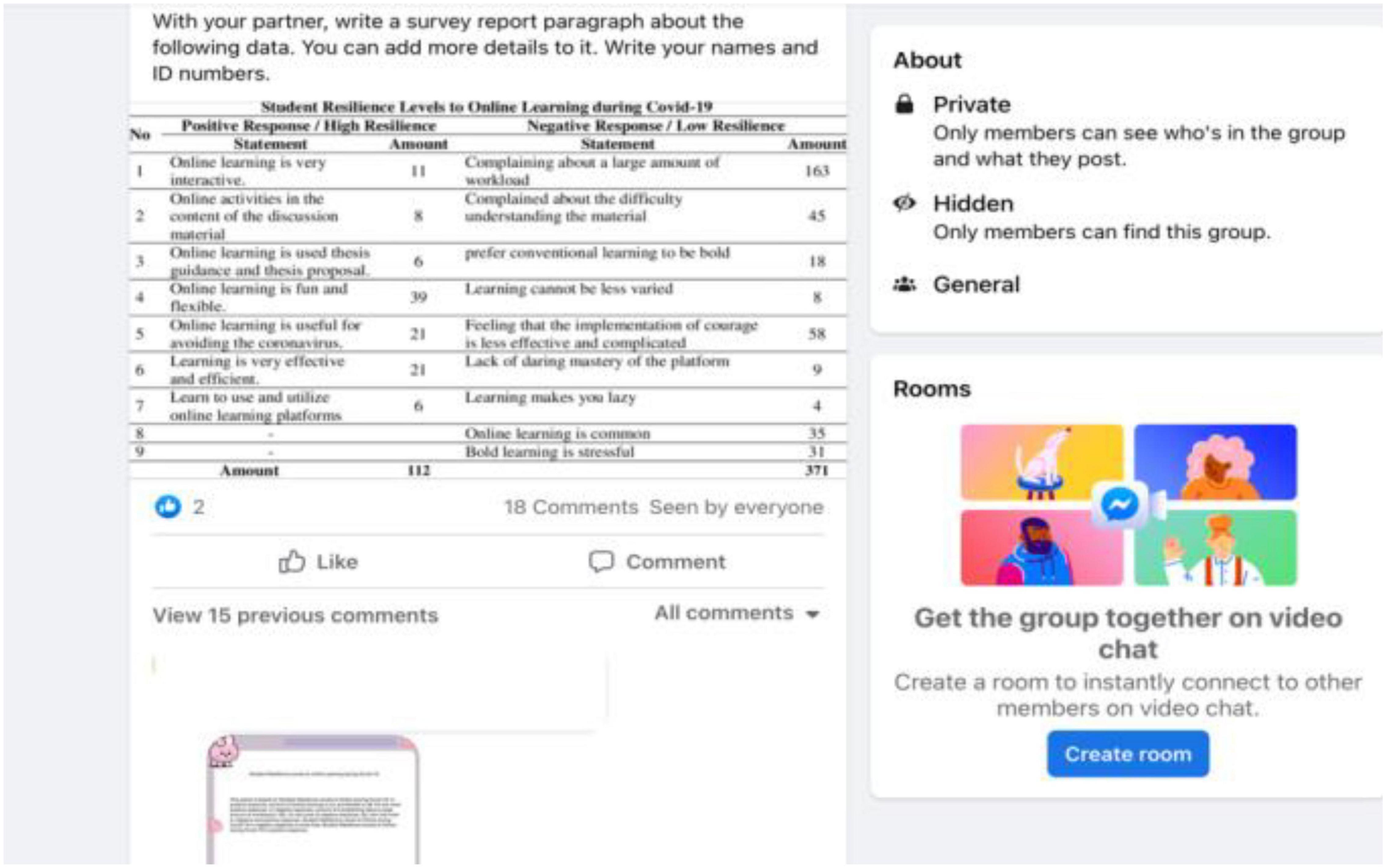

Every week for 12 weeks, this was how I conducted my synchronous hybrid classroom instruction. Fortunately, the record feature in Zoom allowed me to record and save the video for online students who faced a problem with an internet connection. The recorded hybrid classroom instruction videos were posted in our closed-class Facebook group. Online students who missed the class due to internet issues could still engage in the class discussion asynchronously by sharing their ideas in the comment section of the post on our closed-class Facebook group.

Reinforcement

Since the course is a general English language course focusing on reading and writing, other reinforcement language activities were done in an asynchronous learning modality. I utilized another online platform, Facebook, for other independent language learning activities in this asynchronous learning modality. For example, every three weeks, we had an asynchronous writing class discussion posted in our class closed-Facebook group, where everyone was a member. Such an asynchronous writing activity required students to respond to my question in not more than 200 words based on our hybrid class lesson of the day. They were given one week to respond to the discussion question and one of their classmate’s answers.

For asynchronous reading activities, I usually gave my students google form links, which I posted on our closed-Facebook group to access, read, and answer the reading comprehension questions (see Figure 3).

Reflection

Given the current context where the COVID19 is still affecting students’ decision to return to the campus and study in the physical classroom, the teacher reflected that conducting a hybrid class offered an opportunity and choices for students to study online or onsite. In other words, hybrid teaching addressed and catered to students’ language learning preferences during this unprecedented time. Although there were still a number of students who were not confident about returning to the campus, there were also some students who were excited and happy to go back to residential classroom teaching, considering the fact that they were locked in their homes, where they only did online learning for over a year. For the teacher, he was also glad to meet his students in person, especially since they were still first-year students who were excited about becoming university students.

Based on the teaching practice presented, it can be noted that hybrid teaching requires a teacher to have strong pedagogical skills (previous teaching experience) and knowledge and affordances of the online platforms. The teacher observed and perceived that a key to a successful hybrid classroom instruction, where online and onsite students were simultaneously learning, was the availability of technological equipment and platform. He noted that a hybrid classroom should have a multimedia projector, a computer connected to the internet, a web camera, a microphone, and an online platform (Zoom). Without these tools, he believed that a hybrid classroom would not work. Additionally, he also reflected that hybrid teaching was more challenging than fully online teaching as he dealt with students in “two worlds.” This suggests that whenever he planned for his lesson, he did not think only of his online students but also considered his onsite students. He wanted to give equal attention to two groups of students, especially in the various language learning activities. He found it challenging to arrange students for group discussion since he had onsite students, and he wanted them to interact with their online classmates. However, he also found a way to address this issue by encouraging his onsite students to join their online classmates in the breakout room session. Otherwise, onsite students were grouped with their fellow onsite classmates. Nevertheless, he emphasized that “class time” for students’ group discussion should be part of the hybrid classroom instruction.

Another important reflection from the teacher was on how he presented his lesson. He believed that coming to his hybrid classroom instruction required a lot of preparation, especially his teaching and learning materials. He had to prepare a PowerPoint presentation, the online links to his language learning activities, and a breakout room group discussion to facilitate the teaching and learning engagement between him and his students. He was also aware that he had to limit his “teacher time” and focus more on “students’ time” where students had to be in their groups and discuss and share their ideas, promoting a sense of learning community.

He also observed that students were participative and creative during their group discussions and presentation. He realized that if students were given such a space and time to engage in learning activities, they could perform well and learn from each other.

Lastly, the teacher also perceived that reinforcement activities should be given in an asynchronous mode of learning delivery to allow students to work on their own, becoming independent learners. However, he noted that such asynchronous learning activities should be given as assignments where students work at their own pace. Thus, another online platform where students can engage in asynchronous learning activities was needed. In this case, he used his class closed-class Facebook group for all his asynchronous learning activities.

Conclusion

Hybrid teaching may not be a new teaching method; however, how other studies in the literature described and implemented such teaching methodology was rather problematic and ambiguous since it is always used interchangeably with blended learning. In addition, in most studies in the literature, such a teaching method was implemented during the pre COVID19 pandemic. However, in this teaching practice article, we identified the features of hybrid classroom instruction and how hybrid teaching methodology was implemented in a university in Thailand during the COVID19 pandemic. We argue that hybrid teaching is synchronous teaching of students in the classroom and online simultaneously using an online platform, Zoom. This definition is in contrast with Singh et al. (2021), who mentioned that “online interactions in a hybrid medium of instruction can be completed either synchronously using real-time meeting sessions or asynchronously where students interact at different times” (p. 142). As a teaching method, hybrid teaching emphasizes the availability of technological equipment and platform such as a multimedia projector, a computer connected to the internet, a web camera, a microphone, and an online platform (Zoom). Likewise, it also addresses students’ learning preferences considering that the COVID19 cases still counted and some students were not yet ready to be back on campus. However, like any other teaching methodologies, especially when teachers lack training, orientation, and skills in employing such a teaching method, it also means teaching issues. Thus, it is crucial that support be given to the teachers by providing them training on hybrid teaching.

Although this teaching practice is limited only to a specific context, a university in Thailand, it offers implications that education practitioners, scholars, and policymakers can consider when conducting a hybrid classroom instruction. First, the teacher utilized Zoom’s platform for his online students to join his hybrid class. Although Zoom may be a good platform for online teaching as it has features for screen-sharing and breakout room discussions, other online platforms should also be considered, especially since Zoom requires a premium account to access these features. Using Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, Facebook, and Google classroom may provide different perspectives and practices in hybrid teaching. Second, hybrid teaching is believed to provide an alternative method during the COVID19 pandemic or post COVID19 education. However, it requires some tools to make it work, and schools should consider the availability of these tools in their context before implementing such a teaching methodology. Third, as emphasized earlier, teachers need training before shifting to hybrid classroom instruction. Although teachers may utilize their existing pedagogical knowledge and skills in conducting hybrid teaching, providing them with the necessary training would equip them, making them confident to deliver their lessons. Fourth, learners are important clients in hybrid teaching. Thus, teachers who embark on doing hybrid teaching should consider their teaching and learning materials whether or not they support the learning needs of their students so that students’ engagement and active participation in the hybrid classroom instruction are ensured.

For future research, exploring more on the concept of hybrid teaching from a different perspective and context would offer new insight into its conceptualization and practice.

Author Contributions

MU contributed to conception and design of the manuscript. WP contributed the teaching practice and the reflection. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Chakraborty, P., Mittal, P., Gupta, M. S., Yadav, S., and Arora, A. (2021). Opinion of students on online education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 3, 357–365. doi: 10.1002/hbe2.240

Chen, B. H., and Chiou, H. H. (2014). Learning style, sense of community and learning effectiveness in hybrid learning environment. Int. Learn. Environ. 22, 485–496. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2012.680971

Dowling, C., Godfrey, J. M., and Gyles, N. (2003). Do hybrid flexible delivery teaching methods improve accounting students’ learning outcomes? Acc. Educ. 12, 373–391. doi: 10.1080/0963928032000154512

Drewelow, I. (2013). Exploring graduate teaching assistants’ perspectives on their roles in a foreign language hybrid course. System 41, 1006–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2013.09.007

Garrison, D. R., and Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Int. High. Educ. 7, 95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Garrison, D. R., and Vaughan, N. D. (2013). Institutional change and leadership associated with blended learning innovation: two case studies. Int. High. Educ. 18, 24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.09.001

Kansal, A. K., Gautam, J., Chintalapudi, N., Jain, S., and Battineni, G. (2021). Google trend analysis and paradigm shift of online education platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Infect. Dis. Rep. 13, 418–428. doi: 10.3390/idr13020040

Klimova, B. F., and Kacetl, J. (2015). Hybrid learning and its current role in the teaching of foreign languages. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 182, 477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.830

Lin, O. (2008). Student views of hybrid learning: a one-year exploratory study. J. Comput. Teach. Educ. 25, 57–66. doi: 10.1080/10402454.2008.10784610

Linder, K. E. (2017). Fundamentals of hybrid teaching and learning. New Direct. Teach. learn. 149, 11–18. doi: 10.1002/tl.20222

Maatuk, A. M., Elberkawi, E. K., Aljawarneh, S., Rashaideh, H., and Alharbi, H. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and E-learning: challenges and opportunities from the perspective of students and instructors. J. Comput. High. Educ. 34, 21–38. doi: 10.1007/s12528-021-09274-2

Moorhouse, B. L., and Wong, K. M. (2022). Blending asynchronous and synchronous digital technologies and instructional approaches to facilitate remote learning. J. Comput. Educ. 9, 51–70. doi: 10.1007/s40692-021-00195-8

Neuwirth, L. S., Joviæ, S., and Mukherji, B. R. (2021). Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 27, 141–156. doi: 10.1177/1477971420947738

Nhu, P. T. T., Keong, T. C., and Wah, L. K. (2019). Issues and challenges in using ICT for teaching English in Vietnam. CALL-EJ 20, 140–155.

O’Byrne, W. I., and Pytash, K. E. (2015). Hybrid and blended learning. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 59, 137–140. doi: 10.1002/jaal.463

Oliver, M., and Trigwell, K. (2005). Can ‘blended learning’ be redeemed? Elearn. Dig. Media 2, 17–26. doi: 10.2304/elea.2005.2.1.17

Saichaie, K. (2020). Blended, flipped, and hybrid learning: definitions, developments, and directions. New Direct. Teach. Learn. 164, 95–104. doi: 10.1002/tl.20428

Sayıner, A. A., and Ergönül, E. (2021). E-learning in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 27, 1589–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.05.010

Singh, J., Steele, K., and Singh, L. (2021). Combining the best of online and face-to-face learning: hybrid and blended learning approach for COVID-19, post vaccine, & post-pandemic world. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 50, 140–171. doi: 10.1177/00472395211047865

Smith, K., and Hill, J. (2019). Defining the nature of blended learning through its depiction in current research. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 38, 383–397. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1517732

Solihati, N., and Mulyono, H. (2017). A hybrid classroom instruction in second language teacher education (SLTE): a critical reflection of teacher educators. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 12, 169–180. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v12i05.6989

Ulla, M. B., and Achivar, J. S. (2021). Teaching on Facebook in a university in Thailand during the COVID-19 pandemic: a collaborative autoethnographic study. Asia Pac. Soc. Sci. Rev. 21, 169–179.

Ulla, M. B., and Perales, W. F. (2021a). Emergency remote teaching during COVID19: the role of teachers’ online community of practice (CoP) in times of crisis. J. Int. Media Educ. 9, 1–11.

Ulla, M. B., and Perales, W. F. (2021b). Facebook as an integrated online learning support application during the COVID19 pandemic: Thai university students’ experiences and perspectives. Heliyon 7:e08317. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08317

Keywords: education, hybrid classroom, hybrid teaching, online teaching & learning, post COVID19 pandemic

Citation: Ulla MB and Perales WF (2022) Hybrid Teaching: Conceptualization Through Practice for the Post COVID19 Pandemic Education. Front. Educ. 7:924594. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.924594

Received: 20 April 2022; Accepted: 03 June 2022;

Published: 22 June 2022.

Edited by:

Niwat Srisawasdi, Khon Kaen University, ThailandReviewed by:

Pawat Chaipidech, Khon Kaen University, ThailandChiu-Lin Lai, National Taipei University of Education, Taiwan

Patcharin Panjaburee, Khon Kaen University, Thailand

Copyright © 2022 Ulla and Perales. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: William Franco Perales, d2lsbGlhbS5wZUBtYWlsLnd1LmFjLnRo

Mark Bedoya Ulla

Mark Bedoya Ulla William Franco Perales

William Franco Perales