- Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand

This research attempted to illustrate how different mentoring approaches impact student-teacher identity development. Mentoring approaches in this study were categorized into transmission-oriented and constructivist-oriented. Guided by the biographical-narrative identity theory, the data in this study were extracted from interviews with four student teachers from Thailand while they were in the teaching practicum. It was found that student teachers who received the constructivist-oriented mentoring perceived themselves as teachers, were more confident about their teaching abilities, and expressed willingness to enter the teaching profession than those who received the transmission-oriented mentoring. Implications for selecting qualified school-based mentor teachers and the urgent need to offer an induction program to support mentors are discussed.

Introduction

Teaching practicum is an integral part of teacher education worldwide, and it varies from country to country (Darling-Hammond, 2017). In Thailand, where this paper is situated, teaching practicum is compulsory for teacher education, which is expected to be designed in constructive alignment with professional standards prescribed by the Teachers Council of Thailand (Vibulphol, 2015; Prabjandee, 2020). Teacher education in Thailand has undergone many reforms since 1978, “from a traditional model for teachers to a degree-led teacher educational model, and more recently, to a licensed and accredited teacher professional model” (Thongthew, 2014, p. 543). In 2005, Thai teacher education was changed from four years to five years in an attempt to uplift the status of the teaching profession (Chailom, 2019). However, in 2019, Thai teacher education was shortened to 4 years to solve the teacher shortage crisis (Sairattanain and Loo, 2021). Even though the teaching practicum has received tremendous interest from researchers worldwide for at least five decades (Caires et al., 2012), research on teaching practicum in the Thai context, with a few exceptions (e.g., Prabjandee, 2019; Imsa-ard et al., 2021), is under-represented.

The teaching practicum is very important since it provides opportunities for student teachers to put theory into practice and learn about themselves (Britzman, 2003; Farrell, 2008; Zeicher, 2010; Cohen et al., 2013; Furlong, 2013; Trent, 2013; Smith and Lev-Ari, 2015; Prabjandee, 2019). In the teaching practicum, student teachers spend most of their time with school-based mentor teachers; thus, the heart of the teaching practicum experience depends mainly on the relationships with the mentor teachers (Johnson, 2003; Graves, 2010; Yuan, 2016; Izadinia, 2017). Mentoring relationships can be positive or negative (Izadinia, 2015). Prior research has extensively documented the positive side of mentoring (e.g., Johnson, 2003; Lindgren, 2005; Hobson et al., 2009; Richter et al., 2013; Orland-Barak, 2014; Mok and Staub, 2021). In Germany, for example, Richter et al. (2013) pointed out that positive mentoring relationships fostered teacher efficacy, teaching enthusiasm, and job satisfaction. Additionally, in the review of mentoring beginning teachers, Hobson et al. (2014) summarized that mentoring enabled student teachers to put challenging experiences into perspective, increase job satisfaction, and improve teacher retention.

A plethora of research has documented the positive sides of mentoring; however, little attention has explored its negative side, leaving a considerable gap in teacher education research (Izadinia, 2015, 2017; Yuan, 2016). The emphasis on the negative side will shed light on “useful insights into the complexities and challenges involved in pre-service teachers’ learning to teach” (Yuan, 2016, p. 189). Investigating the impact of negative mentoring will also complement extant literature to inform teacher education design to support student teachers’ professional development. In addition, when attempts were made to explore the negative side of mentoring, it was conducted to focus on student teachers’ knowledge (e.g., Mena et al., 2016). Still, limited research has been undertaken to realize how negative mentoring relationships between mentors and student teachers affect teacher identity development (Izadinia, 2017). This paper attempts to contribute to this sphere of inquiry.

Theoretical underpinnings

Student teacher identity

In the seminal reviews of teacher identity (Beijaard et al., 2004; Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009), it is widely accepted by most researchers that teacher identity is socially constructed, dynamic, and multifaceted. To elaborate, teacher identity is formed through interaction with others in social contexts, and it is also developed based on how others perceive us. Teacher identity is not static; it is constantly evolving. It has been used to refer to in-service and in a discussion of pre-service teachers (Prabjandee, 2020), consisting of myriad aspects such as personal, professional, and political (Beijaard et al., 2004). In a more recent review on student–teacher identity, Izadinia (2013) summarized that student–teacher identity could be defined as “perceptions of their cognitive knowledge, sense of agency, self-awareness, voice, confidence, and relationship with colleagues, pupils and parents, as shaped by their educational contexts, prior experiences and learning communities” (p. 708). Based on this definition, student-teacher identity is all-inclusive, so it is necessary to situate it in a particular theoretical framework (Prabjandee, 2019).

In this study, the biographical-narrative theory, popularized by Kelchtermans (1993), was used to conceptualize student–teacher identity. The theory is appropriate for exploring student–teacher identity because it explains teacher identity construction as a learning process in which student teachers form a teacher identity by making sense of the teaching profession (Prabjandee, 2020). As student teachers learn to become teachers, they develop their understanding of the teaching profession by observing what teaching entails, performing “real” teaching in the school setting, and reflecting upon what kinds of teachers they want to be (Prabjandee, 2020). This understanding demonstrates student-teacher identity as an ongoing trajectory of professional development (Kelchtermans, 1993). In the biographical-narrative theory, Kelchtermans (1993) defined identity as autobiographical stories one narrates in a social context. Specifically, student teachers use stories as an interpretative framework to understand the teaching profession. The stories are both a form and a process illustrating a collective representation of oneself to others (Sfard and Prusak, 2005). The stories are inherently multiple, contextually shaped, and constantly evolving.

Kelchtermans (1993) explained that teacher identity development is an ongoing process of constantly identifying the professional self and formulating a subjective educational theory. The professional self is described as a personal story narrated in a social context. Kelchtermans (1993) argued that the professional self could be conceptualized in five dimensions: self-image, self-esteem, job motivation, task perception, and future perspective. For self-image, it is a general description of oneself as a teacher. Closely related to self-image, self-esteem is one’s confidence in their teaching ability evaluated against professional norms. Job motivation is the desire to choose, stay, or leave the teaching profession. Task perception is the conception of the teaching profession that one perceives. The future perspective is the expectation for professional development. Finally, the subjective educational theory is an interpretative system that student teachers use to make sense of education and teaching (Kelchtermans, 1993).

The impact of mentoring on student–teacher identity

Mentoring is a social activity involving interactions between the mentor and the mentee (Ambrosetti et al., 2014). It is an essential component of the teaching practicum because it supports student teachers in learning about teaching, putting knowledge obtained from teacher education into perspective, and improving their teaching ability (Mena et al., 2017; Mok and Staub, 2021). The notion of mentoring is often used interchangeably with coaching and supervising (Ambrosetti et al., 2014); however, they are somewhat different in their focuses. Mentoring is often juxtaposed with coaching, but mentoring suggests a reciprocal relationship whereby the mentors and the mentee are involved in two-way knowledge sharing through reflective activities (Ambrosetti et al., 2014). In contrast, coaching emphasizes on-the-job training for in-service teachers to achieve implementation fidelity (Teemant et al., 2011). Supervising suggests a hierarchical relationship whereby specific skills are explicitly trained and assessed (Ambrosetti et al., 2014). This paper situates in the context of mentoring since it is conceptually precise when referring to the teaching practicum.

Different mentoring approaches were articulated to characterize the quality of interaction between mentor and mentee (Richter et al., 2013). Cochran-Smith and Paris (1995) described a mentoring continuum as knowledge transmission and knowledge transformation. On the one side, in knowledge transmission, a mentor is perceived as an expert passing on accumulative knowledge and experience of teaching in a hierarchically structured relationship to the mentee. However, on the other side, in knowledge transformation, a mentor is regarded as a collaborative partner helping a student–teacher grow professionally in a mutually generated relationship. In addition, Feiman-Nemser (2001) categorized mentoring as conventional and educative. Even though the two terms (conventional and educative) are different from Cochran-Smith and Paris (1995), conventional mentoring is like the knowledge transmission approach, whereas educative mentoring is like knowledge transformation. As a result, Richter et al. (2013) consolidated the interrelated conceptualizations into transmission-oriented and constructivist-oriented mentoring since they better reflect learning theory. The transmission-oriented mentoring is based on the behaviorist learning theories, describing learning as “a unidirectional process in which learners as passive recipients of information” (Richter et al., 2013, p. 168). The constructivist-oriented mentoring describes learning as the active construction of their knowledge by linking new learning with previous experiences (Richter et al., 2013).

Research on how mentoring impacts student-teacher identity development is scarce in the international research landscape and Thailand context. For example, Izadinia (2015) explored how mentor teachers shaped student–teacher identity by using interviews and reflection journals in an Australian context. It was revealed that a positive mentoring relationship enabled student teachers to feel more confident as teachers. On the contrary, a negative mentoring relationship decreased their confidence, and they thought they did not improve as teachers. Similarly, Yuan (2016) investigated the dark side of mentoring on student–teacher identity in China by using in-depth interviews, field observation, and personal reflection. It was found that negative mentoring dismantled student teachers’ ideal identities, created feared identities, and influenced their professional growth. Recently, Izadinia (2017) added that different mentoring styles impinge on student-teacher identities, facilitating or inhibiting their professional development. Based on these studies, it can be concluded that the different mentoring approaches affect teacher identity and professional growth. While these studies provide valuable insights into the negative side of mentoring, they treated the impact on teacher identity holistically. However, since teacher identity is multifaceted (Beijaard et al., 2004; Beauchamp and Thomas, 2009), how mentoring relationships affect different aspects of teacher identity remains overlooked. By implementing a theoretical framework with multifaceted nature, such as the biographical-narrative theory (Kelchtermans, 1993), the following research questions were used to guide the pursuit of knowledge in this study:

1. How do student teachers describe their mentoring relationships?

2. How do different mentoring relationships affect teacher identity development?

The present study

Context and participants

This paper is part of a larger research project conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2017. The project examined teacher identity development in teacher education and its roles in supporting identity development (Prabjandee, 2020). This paper is not a priori, in which the research questions were formulated to pursue accordingly. Instead, the objective of this paper emerged during the data analysis stage. When this study was conducted, the teacher education program was a 5-year curriculum (4 years of classes and 1 year of a teaching practicum) affiliated with a public university in central Thailand. It was purposively selected because it has a long-history reputation of preparing pre-service teachers to enter the teaching profession. Still, the teacher education program has not yet fully understood why it could produce the graduates who decided to step into the teaching profession to become teachers. This study focuses on one aspect of teacher preparation – mentoring student teachers.

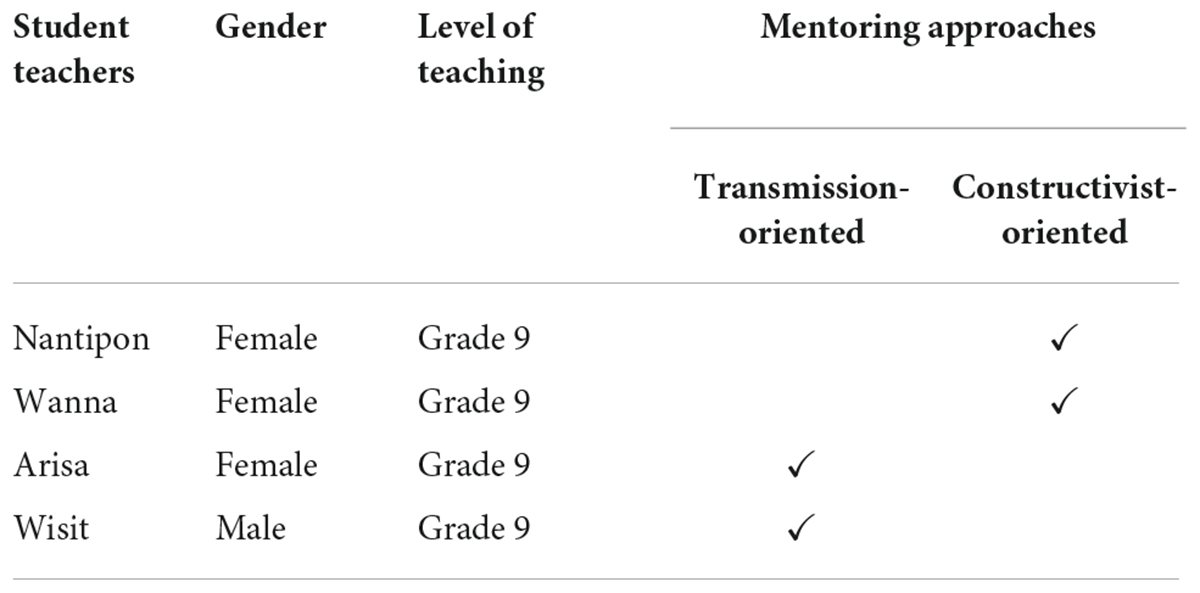

In the larger research project, ten participants volunteered to participate in the study. This paper extracted the data from only four student teachers (hereafter referred to by pseudonyms as Nantipon, Wanna, Arisa, and Wisit) because they were strong cases to illustrate how mentoring approaches affected student-teacher identity. Out of the four participants, Nantipon and Wanna received transmission-oriented mentoring, but Arisa and Wisit received constructivist-oriented mentoring. They were strong cases because the mentoring approaches they received were extremely different, which allows for greater comparison between the two groups. The other six participants were excluded because they received transmission-oriented mentoring like the two cases in this study (Nantipon and Wanna), and their teaching practicum contexts differed from the two selected cases. The participants’ demographic information is presented in Table 1.

All student teachers taught Grade 9 students from different secondary schools. Upon asking why they chose to enter teacher education, all participants reported various reasons. Nantipon said she wanted to be like her secondary-school teacher, whom she admired. Wanna remembered her inspiring childhood moments when she played the role of teacher. Unlike Nantipon and Wanna, who decided to join teacher education because of internal factors, Arisa enjoyed the external benefits of being a teacher. She narrated that teaching is a stable job that she could stay at until 60 years old. Similarly, Wisit entered teacher education simply because he enjoyed the subject, not because he wanted to become a teacher. All student teachers brought these initial reasons into teacher education, where they tried to make sense of the teaching profession. All student teachers chose the schools where they wanted to do a teaching practicum by themselves. The student teachers were assigned to work closely with school-based mentor teachers. In the interviews, Nantipon and Wanna described the relationships with their mentor teachers as corresponding to the constructivist-oriented approach. Arisa and Wisit characterized their relationships with the mentors as the transmission-oriented approach.

Data collection and analysis

The data in this paper were derived from four semi-structured interviews, in which the interview protocol was designed based on the biographical-narrative theory (Kelchtermans, 1993). The interview protocol consisted of several topics: self-concept, perceived confidence to teach, reasons for entering teacher education, their understanding of what teaching entails, and teacher professional development expectations. Before the interviews, the participants were informed of the study’s purposes. They signed a consent form before the interviews were conducted face to face. The interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed for the analysis. The length of the interviews ranged from 29.50 to 33.13 min. During the interviews, written notes on critical points, direct conversations, and hunches were recorded to supplement the data.

In the larger research project, the initial goal of data analysis was to examine teacher identity development in teacher education. The coding method was used to analyze the data to find emergent themes (Saldaña, 2009). While exploring the interview data, it was evident that the student teachers’ self-concepts as a teacher differed. Two student teachers perceived themselves as teachers, while the other two perceived themselves as students learning to become teachers. In trying to find the reasons for the difference, it was found that their relationships with school-based mentor teachers were the cause. As a result, the moments when the student teachers described the relationships with their mentors were analyzed closely by looking at how they linked with their teacher identities.

To maximize the trustworthiness of the analysis, a critical inter-rater was requested to analyze the data independently. Later, we discussed our analyses together until we reached a consensus. For example, we discussed the term to describe mentors’ practices. In my analysis, I used the word “mentoring strategies” to describe the practices narrated from the student teachers’ perspectives. Still, the critical inter-rater suggested that “strategy” might not be conceptually accurate because it is used in the context of acting and solving problems toward a particular aim. Instead, we agreed to use the term “approach” since it is a general way of thinking about the mentors’ underlying thoughts of what student teachers should or should not do. Given the limitation of qualitative research, even though attempts were made to explain the cause for different self-concepts among student teachers contributed by different mentoring approaches, I did not intend to claim a causal relationship. Instead, the goal of the analysis was to provide a detailed description of how different mentoring affects student-teacher identity.

Findings

Different views toward mentor teachers

The thought of entering the teaching practicum for the first time was exhilarating for the four student teachers. They reported that they were extremely excited. It had been four years of learning in the teacher education program. Finally, they had an opportunity to learn about being a teacher in the “real” school setting. However, the relationships with their mentors gave them more exciting or bitter experiences depending on the mentoring approach being implemented. The interview revealed that two student teachers (Wisit and Arisa) described the relationships with their mentor teachers as unfavorable, controlling, and uneasy. In contrast, the other two (Nantipon and Wanna) described the relationships with their mentors as supportive, encouraging, and favorable. Even though Wisit and Arisa were placed in different schools, they were assigned to work with mentor teachers who adopted the transmission-oriented mentoring approach. It should be noted that the mentor teachers did not articulate what approaches they used for mentoring. Still, judging from the participants’ perspective, they implemented transmission-oriented mentoring. When asking why they did not feel like a teacher, Wisit immediately replied:

Wisit: “My mentor has certain views about teaching. She wants me to do exactly what she tells me to do. Before I do something, I must ask for permission from her. I must run through what I want to do with her. She told me not to use negative reinforcement when the students misbehave. I tried to use only positive reinforcement, but the students didn’t care. They didn’t respect me. They said that even their parents did not tell me what to do. I don’t think I can be a good teacher. She corrected me when I taught the students that ‘eat breakfast’ was okay. She interrupted me immediately during my class and said that’s wrong. She told the entire class to ‘have breakfast.’ I saw in a book that ‘eat breakfast’ is okay, but I don’t share it with her. It seems like she wanted me to teach just like her. I keep my mouth shut most of the time.”

It was evident that Wisit’s mentor wanted to mold Wisit into a particular type of teacher based on her conception of a good teacher. She had “certain views about teaching,” such as “not to use negative reinforcement,” and she tried to impart these views to Wisit. As indicated in the interview response that “I must run through what I want to do with her,” the mentor teacher did not relinquish her authority to Wisit, resulting in a lack of freedom to experiment with teaching by himself. These mentoring practices hindered the adoption of teacher identity since Wisist did not perceive himself as a teacher.

Similarly, upon being asked to articulate why she did not see herself as a teacher, Arisa immediately narrated her relationships with the mentors.

Arisa: “My mentor always controls me. She always tells me to do things and asks me to follow strictly. She always gives me the topic to teach last minute. I always don’t have much time to prepare. When I asked for permission to plan teaching topics by myself, she refused. She told me she knew the students and what they wanted to learn. She asked me to have hands-on activities in every class. I can’t do every class because she gives me the topic to teach last minute. I became incompetent in her eyes. One day she asked me in front of the crowd ‘Do you really want to be a teacher?’ I don’t have the freedom to do what I want. Sometimes, I envy my friends who have supportive mentors. I feel like I am not myself.”

Based on the quote above, it was clear that Arisa worked with a highly controlling mentor teacher who did not allow her to have freedom in teaching. Like Wisit’s mentor, Arisa’s mentor had a clear image of what teaching should be, and she wanted to implant this image in Arisa. Her response is filled with bitter emotion, which signifies her inability to adopt a teacher identity.

On the contrary, Nantipon and Wanna described the relationships with their mentors as overwhelmingly positive and corresponding to the constructivist-oriented approach. Nantipon reported that she felt like a teacher because her mentor was supportive and kind.

Nantipon: “My mentor is amazing! She always supports me in everything. My first day of teaching was a disaster. I was shaking. I couldn’t hear myself. I knew it was not a good class even though I was very prepared, but my mentor comforted me at the end of the class. She told me that it happened to everyone. Prepare more if you feel that you are not confident. Keep doing it. Just do it. What is good about her is that she allowed me to fail even though she knew that I would fail. When I succeed, it is because of her support. When I asked for teaching tips, she gave me valuable suggestions.”

For Nantipon, the relationships with her mentor were depicted as positive and favorable. Nantipon’s mentor gave her the freedom to experience teaching by herself and learn from her mistakes. Her mentor also offers psychological support (she comforted me) and technical support (she gave me valuable suggestions). These types of support eased the challenges she encountered during the teaching practicum.

Moreover, upon being asked why she felt she was a teacher, Wanna immediately reported that it was because of her mentor.

Wanna: “My mentor always gives me opportunities to do the job of real teachers. She allows me to plan lessons, solve students’ misbehaviors problems, or give consultations to students. She never intervenes in what I do, but she observes. I know she cares, but she gives me space. When I need help, she is there for me. I’m not afraid to make mistakes because I know that she has my back all the time.”

It was obvious that Wanna’s mentor is very supportive during her teaching practicum. Freedom is the central practice of their mentoring relationships. Since she was given a space to experiment with her teaching and she was permitted to fail, Wanna was empowered to take charge of her own learning to become a teacher. She could construct the knowledge of teaching by herself, and she could adopt teacher identity positions based on her teaching experiences.

The impact of mentoring on student–teacher identity

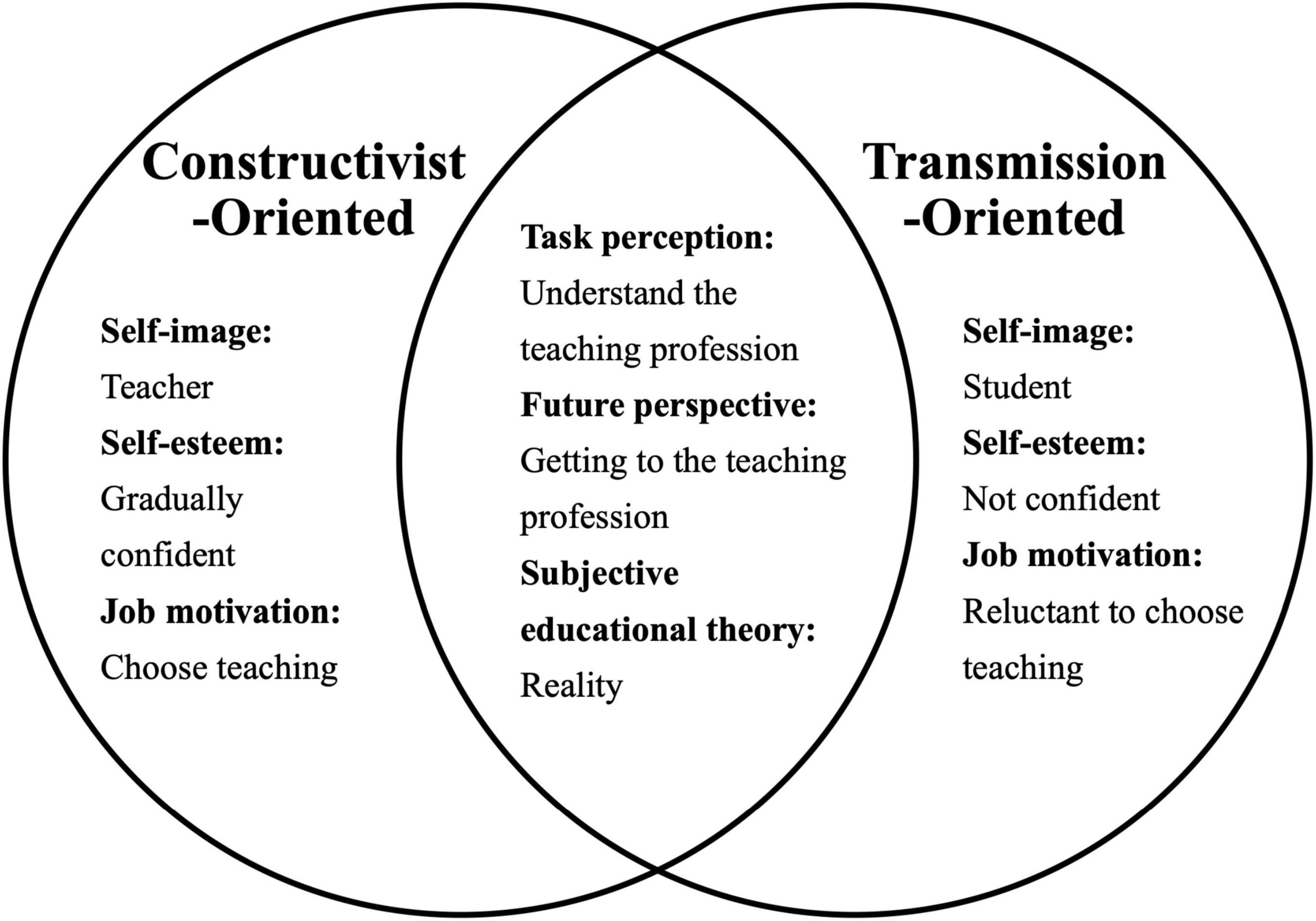

Teacher identity was shaped by student teachers’ biographies, including motivation to choose teacher education as a career choice and initial image of the teaching profession. Wisit was not interested in being a teacher but was attracted to teacher education because he enjoyed the English language. Arisa perceived that teaching could offer her financial stability, and she wanted to be an English teacher, “just like my mother.” The interview data revealed that mentoring relationships strongly impacted student-teacher identity development. The impacts are manifested in different aspects of student–teacher identities as illustrated in Figure 1.

The data revealed that different mentoring approaches affected three aspects of student-teacher identities (self-image, self-esteem, and job motivation); however, the other three aspects were not affected by mentoring approaches (task perception, future perspective, and subjective educational theory). Nantipon and Wanna, who received constructivist-oriented mentoring, perceived themselves as teachers because they were given the power and space to experiment with teaching and learn from their mistakes. In other words, they were provided opportunities to take risks. They could construct the knowledge of the teaching profession by themselves. However, Wisit and Arisa did not start to adopt teacher identity because they were not given freedom. In addition, the four students also reported different self-esteem or their perceived confidence to teach. Those who received the constructivist-oriented mentoring tended to be more confident in their teaching ability than those in the transmission-oriented group. Moreover, different mentoring approaches affected their job motivations. At the end of the teaching practicum, the constructivist-oriented group was more willing to step into the teaching profession than the transmission-oriented group.

However, the other three aspects of student-teacher identities were not affected by different mentoring approaches, namely task perception, future perspective, and subjective educational theory. All participants reported that they understood the nature of teaching better and witnessed its complexities with their own eyes. During the teaching practicum, they also developed expectations to know how to get into the teaching profession, even though those who received the transmission-oriented mentoring expressed a reluctance to enter the teaching profession. Finally, their subjective educational theories were materialized into reality; they became aware of the real meaning of teaching. These similarities across the participants were attributed to the holistic experiences of the teaching practicum. The context of the teaching practicum itself helped student teachers understand the complexity of the teaching profession.

Discussion

Utilizing the biographical-narrative theory (Kelchtermans, 1993), this study pointed out that different mentoring approaches impact student–teacher identity development. Mentoring approaches revealed in this study were characterized based on the interaction between the mentor and the mentees, degree of freedom to experiment with teaching, and mentoring expectations from student teachers. The mentoring approaches, revealed in this study, followed transmission-oriented and constructivist-oriented mentoring (Richter et al., 2013). Unlike prior research that presented the impact of negative mentoring relationships on student-teacher identities from a holistic perspective (e.g., Izadinia, 2015, 2017; Yuan, 2016), this study found that mentoring approaches affected self-image, self-esteem, and job motivation, but they did not affect task perception, future perspective, and subjective educational theory. Based on the findings, it was clear that mentoring relationships partially impacted student-teacher identities.

This study pointed out that different mentoring approaches affected how student teachers perceived themselves (teachers or student teachers) and later influenced their confidence to teach (gradually confident or not confident) and the decision to step into the teaching profession after completing the teaching practicum (choose teaching or reluctance to choose teaching). Those who had self-concept as teachers believed in their ability to teach and tended to step into the teaching profession more than those who did not. The findings are not entirely surprising, but they are unique in the literature. Prior research has revealed that negative mentoring affected student-teacher identity (Izadinia, 2015, 2017; Yuan, 2016), but this study found that negative mentoring approaches did not only affect student teachers themselves but also affected the teaching profession since some student teachers were not certain about entering the teaching profession because of the negative mentoring approaches they received during the teaching practicum.

Mentoring relationships did not affect the other aspects of student-teacher identity: task perception, future perspective, and subjective educational theory. This finding is also new to the literature. Regardless of receiving different mentoring approaches, all participants became aware of the complexity of the teaching profession, expressed the desire to improve themselves similarly, and their subjective educational theory became a reality than before. This might be because the teaching practicum itself provides tremendous opportunities for the student teachers to figure out the nature of the teaching profession (Kelchtermans, 1993). These findings added to the benefits of the teaching practicum articulated clearly in prior research (e.g., Britzman, 2003; Farrell, 2008; Zeicher, 2010; Cohen et al., 2013; Furlong, 2013; Trent, 2013; Smith and Lev-Ari, 2015; Prabjandee, 2019).

Even though this study offers an insight into how different mentoring approaches impact student-teacher identities, interpreting the findings should be conducted with caution. The results could not be generalized since the participants were only case studies to illustrate how different mentoring approaches impact student-teacher identity development. Additionally, the data in this study were obtained from the student teachers’ perspectives only; “the other side of stories,” for example, from mentor teachers, were not included. Future research may want to compare the data from student teachers’ perspectives with mentors’ perspectives to triangulate the results. Other possible reasons can also be further explored to see how they affected student-teacher identity development.

Implications and conclusion

This paper provides empirical evidence to claim that a mentor teacher is essential in the teaching practicum. The importance of mentor teachers is evident from the impact of their mentoring practices on student-teacher identity development (Izadinia, 2015, 2017; Yuan, 2016). Teacher educators should spend considerable time selecting qualified mentor teachers to work closely with student teachers. Based on the findings of this study, it was clear that mentor teachers should be supportive of student teachers during the teaching practicum. They should also offer a safe space for the student teachers to experiment with teaching by themselves. The student teachers should be allowed to fail to teach and learn from their mistakes rather than protect them from failure. Imposing what student teachers should do from the mentors’ preference hurts more than helps.

Because the mentor teachers in this study did not use similar mentoring approaches, resulting in different practices that negatively impact student-teacher identities, the roles of mentor teachers should be communicated clearly. On the one hand, mentor teachers should be aware that the transmission-oriented approach, where mentor teachers impinged particular views of teaching to student teachers, hindered the adoption of student-teacher identity even though they might adopt it with healthy intentions. On the other hand, they should be aware that the constructivist-oriented approach could facilitate student-teacher identity development. The findings call for offering a mentor induction program to prepare mentor teachers to implement constructivist-oriented mentoring. Extensive literature often finds ways to provide an induction program for student teachers, but induction programs for mentor teachers are overlooked. This study calls for an urgent need to design an induction program to support mentor teachers to undertake effective mentoring practices for student teachers during the teaching practicum.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Burapha University Institutional Review Board (BUU-IRB). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) (MRG5980181).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author thank the participants, who volunteered to participate in this study. Thanks to the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) for providing the grant to conduct this research. Finally, thanks to the reviewers who offer constructive feedback to improve the quality of this manuscript. Any mistakes are all mine.

References

Ambrosetti, A., Knight, B. A., and Dekkers, J. (2014). Maximizing the potential of mentoring: a framework for pre-service teacher education. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 22, 224–239. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2014.926662

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/03057640902902252

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., and Verloop, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 107–128. doi: 10.1017/S0022215121001389

Britzman, D. (2003). Practice Makes Practice: A Critical Study of Learning to Teach. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Caires, S., Almeida, L., and Vieira, D. (2012). Becoming a teacher: student teachers’ experiences and perceptions about teaching practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 163–178. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2011.643395

Chailom, S. (2019). Five-year curriculum of teacher education in Thailand: gain or pain? London: International Academic Multidisciplinary Research Conference. Available online at: http://icbtsproceeding.ssru.ac.th/index.php/ICBTSLONDON/article/view/49

Cochran-Smith, M., and Paris, C. L. (1995). “Mentor and mentoring: did Homer have it right,” in Critical Discourses on Teacher Development, ed. J. Smyth (London, UK: Cassell), 181–202.

Cohen, E., Hoz, R., and Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: a review of empirical studies. Teach. Educ. 24, 345–380. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.711815

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from International Practice? Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 291–309.

Farrell, T. S. (2008). Here’s the book, go teach the class’ ELT practicum support. RELC J. 39, 226–241. doi: 10.1177/0033688208092186

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). Helping novices learn to teach: lessons from an exemplary support teacher. J. Teach. Educ. 52, 17–30. doi: 10.1177/0022487101052001003

Furlong, C. (2013). The teacher I wish to be: exploring the influence of life histories on student teacher idealized identities. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 68–83. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2012.678486

Graves, S. (2010). Mentoring pre-service teachers: a case study. Aust. J. Early Child. 35, 14–20. doi: 10.1177/183693911003500403

Hobson, A., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., and Tomlinson, P. D. (2014). Mentoring beginning teachers: what we know and what we don’t. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001

Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., and Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: what we know and what we don’t. Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.001

Imsa-ard, P., Wichamuk, P., and Chuanchom, C. (2021). Muffled voices from Thai pre-service teachers: challenges and difficulties during teaching practicum. Shanlax Int. Educ. 9, 246–260. doi: 10.34293/education.v9i3.3989

Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers’ professional identity. Br. Educ. Res. J. 39, 694–713. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2012.679614

Izadinia, M. (2015). A closer look at the role of mentor teachers in shaping preservice teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 52, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.08.003

Izadinia, M. (2017). From swan to ugly duckling? Mentoring dynamics and preservice teachers’ readiness to teach. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 66–83. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2017v42n7.5

Johnson, K. A. (2003). “Every experience is a moving force”: identity and growth through mentoring. Teach. Teach. Educ. 19, 787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.06.003

Kelchtermans, G. (1993). Getting the story, understanding the lives: from career stories to teachers’ professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 9, 443–456. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(93)90029-G

Lindgren, U. (2005). Experiences of beginning teachers in a school-based mentoring program in Sweden. Educ. Stud. 31, 251–263. doi: 10.1080/03055690500236290

Mena, J., García, M., Clarke, A., and Barkatsas, A. (2016). An analysis of three different approaches to student-teacher mentoring and their impact on knowledge generation in practicum settings. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 53–76. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2015.1011269

Mena, J., Hennissen, P., and Loughran, J. (2017). Developing pre-service teachers’ professional knowledge of training: the influence of mentoring. Teach. Teach. Educ. 66, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.024

Mok, S. Y., and Staub, F. C. (2021). Does coaching, mentoring, and supervision matter for pre-service teachers’ planning skills and clarity of instruction? A meta-analysis of (quasi-)experimental studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103484. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103484

Orland-Barak, L. (2014). Mediation in mentoring: a synthesis of studies in Teaching and Teacher Education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 44, 180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.011

Prabjandee, D. (2019). Becoming English teachers in Thailand: student teacher identity development during teaching practicum. Issues Educ. Res. 29, 1277–1294.

Prabjandee, D. (2020). Narratives of learning to become English teachers in Thailand: developing identity through a teacher education program. Teach. Dev. 24, 71–87. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2019.1699155

Richter, D., Kunter, M., Lüdtke, O., Klusmann, U., Anders, Y., and Baumert, J. (2013). How different mentoring approaches affect beginning teachers’ development in the first years of practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 36, 166–177.

Sairattanain, J., and Loo, D. B. (2021). Teacher education reform in Thailand: a semiotic analysis of preservice English teachers’ perception. J. Res. Policy Pract. Teach. Teach. Educ. 11, 28–45. doi: 10.37134/jrpptte.vol11.2.3.2021

Sfard, A., and Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: in search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educ. Res. 34, 14–22. doi: 10.3102/0013189X034004014

Smith, K., and Lev-Ari, L. (2015). The place of the practicum in pre-service teacher education: the voice of students. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 33, 289–302. doi: 10.1080/13598660500286333

Teemant, A., Wink, J., and Tyra, S. (2011). Effects of coaching on teacher use of sociocultural instructional practices. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 683–693. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.006

Thongthew, S. (2014). Changes in teacher education in Thailand 1978 – 2014. J. Educ. Teach. 40, 543–550. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2014.956539

Trent, J. (2013). From learner to teacher: practice, language, and identity in a teaching practicum. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 41, 426–440. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2013.838621

Vibulphol, J. (2015). Thai teacher education for the future: opportunities and challenges. J. Educ. Stud. 43, 50–64.

Yuan, E. R. (2016). The dark side of mentoring on pre-service language teachers’ identity formation. Teach. Teach. Educ. 55, 188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.01.012

Keywords: student-teacher identity, mentoring, teaching practicum, teacher education, mentoring approach

Citation: Prabjandee D (2022) Inconvenient truth? How different mentoring approaches impact student–teacher identity development. Front. Educ. 7:916749. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.916749

Received: 10 April 2022; Accepted: 29 June 2022;

Published: 22 July 2022.

Edited by:

Christi Underwood Edge, Northern Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Gwen Moore, Mary Immaculate College, IrelandEkamorn Iamsirirak, Ramkhamhaeng University, Thailand

Pariwat Imsa-ard, Ramkhamhaeng University, Thailand, in collaboration with reviewer EI

Copyright © 2022 Prabjandee. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denchai Prabjandee, ZGVuY2hhaUBnby5idXUuYWMudGg=

Denchai Prabjandee

Denchai Prabjandee