95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Educ. , 14 July 2022

Sec. Special Educational Needs

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.914448

This article is part of the Research Topic Inclusion and Diversity in Education View all 9 articles

This paper investigates the elements of a “trauma informed classroom.” The origins of this approach lie in the developing understanding of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and their significant life-long negative effects on development in all areas of life. The study takes a narrative topical approach drawing on established research on trauma impact, and the emerging studies on trauma informed approaches in education. Children and young people affected by traumas such as living with addiction, domestic violence or severe neglect are currently attending educational institutions. There are also young refugees, who are victims of state sponsored violence and brutality. These young people frequently struggle with concentration and may also have relational and behavioural difficulties. Logistical difficulties around attendance, resources, and PTSD type symptoms add to their burden and lead to dropping out or gaining a reputation as a troublemaker or incapable student. The foundation of the “trauma informed classroom” is an understanding by teachers of the daily circumstances of their pupils’ lives, and awareness of what trauma-based reactions and behaviours look like. The rituals and teaching methods of the classroom may be modified in response to the pupils’ needs, in consultation with them, and in a system of ongoing feedback. This work necessitates a collaborative team to support the teacher, and access relevant services. The aim of this paper is to explore the elements of a trauma informed classroom. The benefits and challenges for pupils and teachers will also be discussed.

The definition of trauma in the nineteenth century identified it as based in personal moral weakness in battle weary soldiers. It was a century before trauma was recognised in the 1980s by the American Psychiatric Association as a condition with disabling symptoms and effects (Thomas et al., 2019). The understanding of the lifelong effects of trauma and the high incidences of young people attending education with significant adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) was initiated in the work of Felitti et al. (1998). Further research by Anda et al. (2006) led to the development of concepts of trauma informed practice (Hickey et al., 2020). Early studies into ACEs, which surveyed thousands of adults found negative impacts on health, employment and education opportunities that lasted a lifetime and had intergenerational implications (Felitti et al., 1998; Anda et al., 2006). Specific research into cognitive and educational effects of abuse found a mixture of negative effects on concentration, cognition and learning ability, combined with impact on vital social and emotional relational skills (Perkins and Graham-Bermann, 2012).

Earlier research analysed the number of ACEs a person had suffered and found a direct causality with mental and physical health and educational and employment opportunities (Bellis et al., 2016). Early definitions of ACEs included experience of sexual, physical or psychological abuse, violence toward mother, substance abuse, mental illness or suicidal behaviour in the home or incarceration of a family member. These were measured against health risks:

We included a history of ischemic heart disease (including heart attack or use of nitroglycerin for exertional chest pain), any cancer, stroke, chronic bronchitis, or emphysema (COPD) (including heart attack or use of nitroglycerin for exertional chest pain), cancer, stroke, chronic bronchitis (COPD), diabetes, hepatitis or jaundice, and any skeletal fractures (as a proxy for risk of unintentional injuries) (Felitti et al., 1998, p. 248).

The findings demonstrated significant deleterious effects on long term health conditions as listed above. Negative life choices around substance abuse, poor employment and housing and higher rates of depression and suicide were also related to the number of ACEs and the severity and length of exposure for the young person.

Later research was more nuanced and developed a further integration of the individual’s life circumstances and the societal context of their life as highlighted by Gorski:

The best trauma informed practices are rooted in anti-racism, and anti-oppression more broadly, not just in helping students cope with the impact of isolated traumatic events, and not just in assuming that a student whose family is experiencing poverty must be experiencing some sort of abuse at home. If I am not actively anti-racist, I am not trauma-informed (Gorski, 2020, p. 17).

This broader focus was also found in resilience research which moved away from a focus on the individual’s competencies or deficits to explore the wider impact of intersectionality on the individual (Romero et al., 2018). The emphasis on social emotional (SEL) programmes and their effectiveness in supporting positive development and ameliorating negative experience is part of this understanding (Taylor et al., 2017).

The concept of widespread trauma being a public health emergency has contributed to the understanding of the negative effects on society of unresolved trauma being suffered into adulthood (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, p. 2). Studies have researched the benefits of various interventions with major institutions agreeing on the deleterious effects of living with severe poverty, neglect, abuse, and addiction for children and their families (Radford et al., 2013). The shift in understanding from identifying problem issues as needing a “social service” or a “medical” response to awareness of the endemic levels of trauma experienced in severely underserved communities is explored by Nadine Burke. This is the subject of her Ted Talk on working as a paediatrician in one of the most underserved areas of San Francisco (Burke Harris, 2014).

The methodology used was data based searching for the key words noted at the beginning of the paper: “trauma informed classroom, Adverse Childhood Experiences, trauma informed practice, educators, students, implementation, secondary trauma.” Data bases used included Ebsco, Eric, PubMed and Academic Search Complete. Hand searching of articles and reports, specialist journals and international studies was also completed. The journals sourced included those with a focus on education, preventive medicine, trauma, ACEs, psycho-social development, domestic violence, and refugee experiences. The writer was further informed by the professional experience of teachers, lecturers and second chance educators working with student cohorts significantly affected by trauma.

The developing understanding of the long-term effects of ACEs, and the statistics showing high numbers of children affected (Bellis et al., 2016), influenced public health initiatives and education approaches. This highlighted the need for an integrated service from health, education, family support, and juvenile justice, and the importance of collaboration and trauma informed practice (TIP) training across the services (Murphey and Sacks, 2019).

Schools are an obvious site for supports and early intervention for children affected by individual ACEs and community based trauma (Thomas et al., 2019; Douglass et al., 2021). The nature of the school day with its predictable events and timings, and attendance of a broad range of children, makes it a useful site to provide trauma informed supports (Perry and Daniels, 2016).

Traumatic experiences have a direct impact on young people’s cognitive strengths and ability to engage with education. Streeck-Fischer and van der Kolk’s (2000) research on traumatised abused children found they were affected by various developmental factors such as: “Their speech problems interfere with understanding complex situations and the narration of complex stories. Many have limited capacity to comprehend complex visual-spatial patterns. This, in turn, leads to problems with reading and writing” (Streeck-Fischer and van der Kolk, 2000, p. 912). Hultmann and Broberg’s (2016) research in a Swedish psychiatric clinic for 6–17 year olds connected attention and compliance difficulties and impulsivity to family violence. Children’s verbal skills were also negatively affected as were social skills (Hultmann and Broberg, 2016). They also noted the very low rate of reporting by the children to the authorities at under 10%. This suggests that the majority of abused and neglected children are unknown and unsupported in Sweden. This massive underreporting is an international issue corroborated in research (WHO et al., 2013).

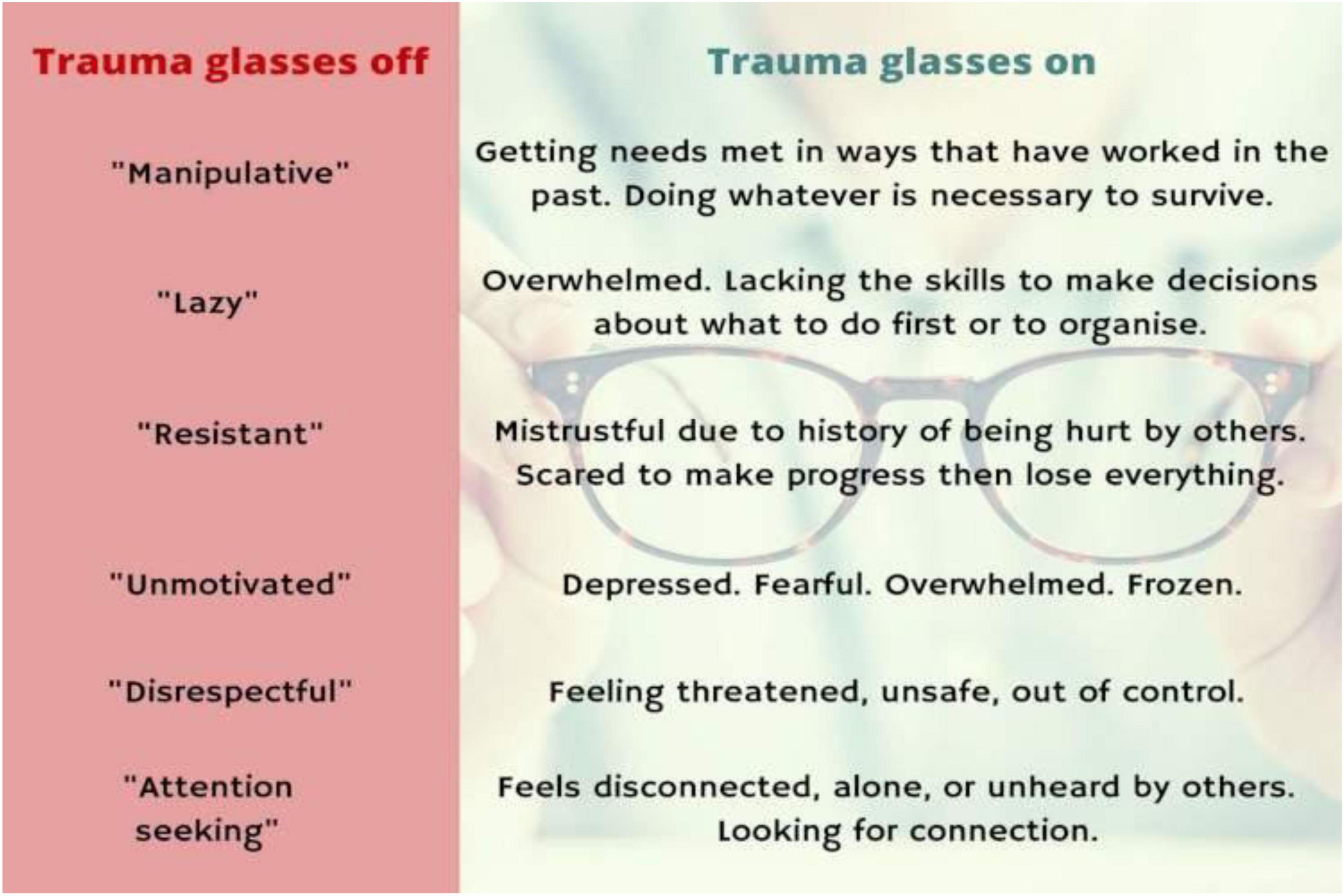

The “Thrive” project conducted a study with 273 second chance educators in Ireland, Austria, Italy, Malta, and Romania. The focus was on educators’ use of TIP, understanding and training around trauma, and secondary stress. The project also provides a detailed set of information around trauma, its manifestations and effects and developed training modules. There are materials for working with second chance learners, case studies and resources. The table in Figure 1 suggests alternative views of young people’s negative behaviour (Thrive, 2021, Module 1:Promoting attachment and safety).

Figure 1. Trauma glasses off and on (Thrive, 2021 Module 1: Promoting attachment and safety).

Schools and education services are increasingly involved as sites for trauma informed supports for young people affected by individual traumatic events, and those situated in their community living circumstances (Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021).

Teachers and the school environment can provide a safe space and nurturing relationships which have been cited as the most important element in recovery from trauma (Treisman, 2018; Murphey and Sacks, 2019). The importance of positive trusting relationships to heal trauma and enable help seeking has been established in research into the effects of domestic violence on young people. Youth advisors in their ‘Voice against Violence’ survey reported that:

People listening to children was a big theme for young people who answered our survey. This is also a big theme for all VAV members especially with regards to adult professionals who children chose to confide in. It is a big privilege to be a child’s trusted adult and it is important that professionals believe children and know how to include the child in any decisions they make about how to help. It is, after all, our lives and our future and we know best what we need (Houghton and Voice Against Violence [VAV], 2011, p. 22).

Young students affected by trauma were interviewed in a qualitative study by Dods (2015) and all three emphasised their need to be heard and feel a trusting relationship with teachers. This was expressed as a desire for acceptance but also as being the basis of reaching out for help: “he felt that if a teacher had approached him and asked him if there was a reason why he was “smoking that much pot and being that kind of grumpy,” then he would have told them his thoughts” (Dods, 2015, p. 125). Young people in foster care, a vulnerable group, emphasised their need to be heard and consulted when engaging in therapy. The importance of disclosing their story at their own pace was also highlighted in this Irish study. As one participant put it: “She (the therapist) actually wanted to get to know me” (Gilmartin et al., 2022, p. 8).

Resilience research has developed an analysis of the family and social environment of the individual and a deeper understanding of the endemic nature of violence and trauma for many underserved communities. Teachers working in vulnerable communities may be the only stable caring adult in the students’ lives and are thus in a position to offer positive relational support and a bridge to referral to more specialist services for their students (Brunzell et al., 2018). A brief search of the literature by the researcher found a very small body of research into trauma informed care until after 2000. This was noted in the systematic review conducted by Stipp and Kilpatrick (2021, p. 68): “found zero articles with the keywords “trauma informed practice education” from 1990 to 2009, and 391 articles 2010 to 2019. Of those, 327 (84%) were published between 2015 and 2019.”

Educators in schools in America and internationally have often been inundated with new programmes and solutions that create more administration for the staff and then fade away (Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021). This pattern is found in the comprehensive review of two decades of trauma informed care by Thomas et al. (2019).

The elements that contributed to successful and lasting reform were first that the reform offered solutions to problems educators were aware of and wanted to solve, second that the reform identified an actual issue that educators were unaware of but engaged with on understanding it, third that the reform correlated to public pressure on socio-political needs in education, and the fourth element was that the educators were supplied with the tools and guidance to implement the practices in the classroom (Cohen and Mehta, 2017, p. 2).

Thus, trauma informed training requires whole staff engagement and awareness, commitment to ongoing implementation of new practices and approaches and some practical tools for applications of the theory in the classroom. The review by Crosby et al. (2018b) looked at the need for TIP in schools severely impacted by deprivation and lack of resources. The links between TIP and socially just education were clarified and justified in terms of the treatment of minority groups and racial discrimination, an analysis used by Gorski (2020) which recognised historical and institutionalised injustice in education. The very significantly higher rate of exclusion and expulsion of female African Americans, at six times the rate of white female students, noted the possibility of this enabling school dropout and juvenile crime involvement (Crosby et al., 2018a). The issue of the institutions or schools being sites of further traumatisation for clients was explored in research into TIP (Crosby et al., 2018a,b). The importance of trauma awareness and the reduction of triggers for students was another key issue (Gorski, 2020; Thrive, 2021).

Appropriate training for educators has been identified as the essential part of the process. Research suggested that up to 60% of adults have suffered significant trauma (Anda et al., 2006), and were at risk of being retraumatised by training focussed on their specific experiences. This figure holds true for educators and support staff in any institution (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Therefore, training in trauma informed practice needs to be carefully tailored to each group and offer information in advance on the content, with easy options for withdrawal from specific sections available for staff according to Koslouski and Chafouleas (2022). The authors base their training on the SAMHSA approach. Their definition of trauma is that:

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014, p. 7).

The important elements recommended by “Samhsa” for effective training are:

Six key principles of a trauma-informed approach: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues (Koslouski and Chafouleas, 2022, p. 1).

The aims of TIP and trauma informed schools (TIS) training shared core elements in international research (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Bywaters, 2017; Thomas et al., 2019; Douglass et al., 2021). Training for a range of organisations in the fields of health, education, psychology, and juvenile crime prioritised these aims (Lucio and Nelson, 2016; Ellison et al., 2020).

These aims included preparation of the programme tailored to the particular staff and situation of the school/institute, recognition of the existence of traumatic experiences among the staff and delivering specific training on trauma, its appearance and effects on individuals. Knowledge of the traumatic elements in the community and their impact and the institutionalised aspect of racism and other social injustices was deemed essential to understand the realities of students’ lives and avoid retraumatisation. Mechanisms of change in the entire organisation and strategies to maintain that evolving system were central to the training aims. In the educational field the same core principles applied. A vital shift in understanding challenging or withdrawn behaviour by students required teachers to ask: “what has happened/what is going on with you?” of students in place of “why did you do that?/What is wrong with you?” This new lens for responding to students’ behaviour aims to replace a punitive attitude to the students with one of relational understanding and open questions (Treisman, 2018; Murphey and Sacks, 2019). The empowerment of staff and pupils was a key aim, giving voice to their concerns in a respectful space was an essential feature of the work.

Systematic approaches to training followed similar progressions:

• Preparation—in advance of the progamme, tailored to the school/institute, with open engagement of staff.

• Inclusion of the whole staff, including auxiliary staff, in the training.

• Information—on the prevalence, meaning and effects of trauma on behaviour and development.

• Reflection on current teacher practice and its relation to the new learning- changes to relational not punitive interactions.

• Application in the classroom—theory to practice.

• Access to supports and appropriate referrals for staff and pupils.

• Peer support for staff- awareness of secondary trauma and compassion fatigue.

• Ongoing review and development of the programme approach and implementation.

• Empowerment and consultation at all levels of the organisation (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021).

Successful implementation following training was characterised by three themes: “(a) Building knowledge—understanding the nature and impact of trauma; (b) Shifting perspectives and building emotionally healthy school cultures; and (c) Self-care for educators” (Thomas et al., 2019, p. 426).

Reasons for reform failure included the lack of buy-in by staff and rejection by parents and students. The training is relational and was most effective when all the stakeholders, including families, were involved and where: “Care Coordination closes a gap that is often present—that between school and family—by facilitating ongoing dialogue between these two systems” (Perry and Daniels, 2016, p. 179).

The fact that there is no formula and that each school or community has its own unique experiences and needs was highlighted in the research into effective TIP training: “key elements of trauma-informed practice are actively brainstorming how to best support a specific situation and engaging in some trial and error to assess students’ responses” (Koslouski and Chafouleas, 2022, p. 3).

The possibility of retraumatisation or secondary traumatisation is real when using TIP training, as college students report 65–85% life-time traumatic experience and many will have had multiple exposures. Similar figures exist for adult staff so the need for understanding the difference between teaching ethically about trauma and using traumatic materials to induce responses is the base for effective staff and student emotional safety (Carello and Butler, 2014). Educators may be triggered by training into their own traumas or may fear inappropriate disclosures from students (Carello and Butler, 2014). Compassion fatigue and burn out are serious issues for educators and are frequently denoted as a personal problem with no institutional support available. Secondary trauma needs to be recognised and more research into the issue is needed (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Thomas et al., 2019). Teachers expressed concerns around a lack of training and information around trauma responses to pupils and confusion of roles between academic and pastoral care (Alisic et al., 2012).

Developing a knowledge and understanding of the effects and manifestations of trauma may empower educators to work more effectively with trauma victims among their students (Burgess and Phifer, 2013). The awareness that the difficult behaviours were not intentional but resulted from the overwhelming impact of trauma helped to reduce the institution’s traditional punitive approach that triggered further antagonism or withdrawal in the affected students (Wegman and O’Banion, 2013).

Social emotional learning (SEL) had value as a mainstream initiative to enhance communication skills and emotional literacy and build up skills for all students. SEL offered a wide range of resources to educators (Elias, 2019) and could form part of a public health approach to education (Greenberg et al., 2017).

A new understanding of challenging behaviours, formerly viewed as the pupil’s consciously oppositional behaviour, was a benefit reported by teachers who took part in training. Professional development (PD) was identified by teachers in a pilot study as a key element in adopting TIP in their school (Perry and Daniels, 2016). The transformative effect of positive relationships and a safe accepting school environment were emphasised in the body of research as providing possible repair of damaged attachment for traumatised pupils (Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021; Thrive, 2021).

A reduction in challenging behaviours and discipline infractions in the school community were another benefit of this approach (Perry and Daniels, 2016; Crosby et al., 2018a). The increased cooperation among the staff and between staff and management was noted as improving motivation and encouraging a more caring working environment (Douglass et al., 2021). Improved communication with families and more interagency cooperation were other positive results for educators (Perry and Daniels, 2016). The importance of self-care for educators, especially in situations where secondary traumatisation is more intense, was prioritised in TIP training and it was recommended that this be part of the organisation’s structure and not a personal responsibility of the teacher (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Luthar and Mendes, 2020). The importance that teachers give to their work with underserved communities as “meaningful work” contributed to their workplace well-being and was strengthened by TIP training (Brunzell et al., 2018).

The students’ need to be heard and understood was expressed as an essential element in the direct research with pupils around TIP in education (Gorski, 2020). The need for a trusted adult to relate to was highlighted in the study of three young people’s school experience who were victims of neglect and domestic violence (Dods, 2015). The young people expressed that:

Frustration and confusion with finding help while in high school was apparent across the case studies. Their collective need for connected relationships with teachers they perceived as caring and respectful was paramount. What the young adults wanted from teachers was not a therapist or any immediate intervention, but rather someone who would notice them, validate their distress, reach out to them, care about them as people, and look out for their overall well-being (Dods, 2015, p. 128–129).

Relational approaches and building supportive relationships through the school community including auxiliary staff, pupils and parents benefitted the students and led to teachers offering each other more peer support (Howell et al., 2019). TIP training which included more methods for responding to trauma reduced numbers of students being referred to special education and being categorised as troublesome students (Banks and Meyer, 2017; Pemberton and Edeburn, 2021). Practices which included non-verbal approaches to self-regulation and innovative teaching methods such as creative and outdoor materials supported students in building trust and reduction of trauma responses (Mulholland and O’Toole, 2021).

A student participant in a student forum in a ghetto school expressed the value of voice:

“When I was talking to those teachers, you could just see those eyes of people who just wanted to know what we were thinking. That just felt so powerful…” He wanted adults to “know that students at this young age have an opinion. We know what we want and can see the different things that are happening. [We can push for change in our school] in a respectful manner without raising our voice, getting upset, and other ways that people have tried to do in the past, which have gone nowhere…” (Mitra, 2006, p. 9).

The value of increased communication in a variety of methods with parents was evident in the body of research, particularly using “Care Coordination” systems. In this study, involving a therapeutic support service to families based in the school, parents continued to support each other when the programme was finished (Perry and Daniels, 2016). Collaboration included school counsellors linking with therapy services (O’Gorman, 2018).

The findings show the international figures for ACEs consistently high across the population and significantly higher in underserved areas. The need for integrated supports and early intervention for children affected by trauma is demonstrated by the high prevalence rates in the ACEs research and the lifelong negative effects (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014; Murphey and Sacks, 2019). TIP is becoming part of organisational practice across various disciplines including education. Schools remain the gathering point for children and youth in every community and are thus positioned to coordinate these supports (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). However, a central problem is that where need is greatest, such as in underserved communities, resources are limited, and educators are suffering from compassion fatigue and burnout. There are various methods of introducing supports in the school situation. Some recommend identifying the students at risk and targetting resources for them (Perry and Daniels, 2016), while others favour a whole school approach with specialist supports emerging from the mainstream teaching and training about trauma. This approach is mindful of the fact that many of the students have been traumatised by personal and institutional factors outside their control (Koslouski and Chafouleas, 2022). The establishment of a feeling of safety, and school as a safe space is the essential part of building a supportive relationship with the entire class, including those most affected by trauma in all cases. This process is detailed by Treisman (2018) in her therapeutic work with children and is described in a study which prioritises safety and developing competencies around self-regulation in the process of healing from trauma (Dauber et al., 2015). The trauma informed school community needs to support educators and other caregivers in this process.

Teachers reported higher levels of emotional and mental distress among students annually, and ensuing pressure on themselves (Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021). The teacher is required to complete a curriculum for their students while responding to the emotional and behavioural effects of trauma among their students. Effective training is valuable in increasing teachers’ skills and understanding of the students’ experiences and tools to differentiate learning tasks and help students to self-regulate were useful. The improved cooperation between teaching staff, families and directors led to a supportive work environment. This more empathic approach was a positive result of training and new TIP initiatives, mirroring the improved relationships in the classroom (Douglass et al., 2021).

However, the teacher is still faced with a classroom to teach and the emotional drain on teachers in violent underserved areas where violence, death and addiction are prevalent is huge (Koslouski and Chafouleas, 2022). Teachers have repeatedly requested more support services in the school itself (Thomas et al., 2019). These include more counselling and behaviour support personnel in the school and resources such as quiet rooms. Links to community-based specialist services are seen as vital to enable the teacher to act as the trusted adult encouraging the student to seek help from the relevant services (O’Gorman, 2018). Where these supports, both internal and external, are lacking many teachers suffer from burn out and compassion fatigue and leave the profession or become detached and demotivated (Luthar and Mendes, 2020). The long-term cost of ignoring these ACEs is already established in the research into effects such as serious illness, physical and mental, increased levels of addiction, homelessness, and family breakdown (Bellis et al., 2016). The need for trauma informed schools and school personnel forms part of the growing understanding of the increased levels of trauma and toxic stress among young people and secondary stress on teachers (Stipp and Kilpatrick, 2021). The lifelong effects of ACEs on the individual and their community require a coordinated response from services. The school is a key site for delivering interventions and supports. Further direct research is needed with students to establish how they perceive the experience of TIP and TIS and their priorities in supports. The field of TIP is relatively new and is evolving. The main body of research to date addresses the needs and training of teachers, the voice of the students of all ages needs to be included.

The findings of this study demonstrate the value of TIP training for educators and the reduction in discipline problems that result (Douglass et al., 2021). This new awareness aligns with the ACEs research concerning the immediate and long term effects of severe or repetitive trauma in youth. The fact that any group of participants in training will include those affected by ACEs and vulnerable to retraumatisation is an emerging field for research as it goes beyond the understanding of vicarious trauma (Koslouski and Chafouleas, 2022). The importance of supportive relationships in response to trauma has been expressed by young people (Dods, 2015) and the role of the teacher as a safe adult for support and referral has been highlighted (Brunzell et al., 2018). The supports and interventions are needed most where resources are already under pressure and educators are working with difficult situations, including violence, on a daily basis. Significant resources are needed to implement change and it needs to be sustainable.

The challenge for practice and direct research in TIP is the concerns around retraumatisation of participants by training or discussion (Carello and Butler, 2014), vs. the need for giving a voice to those affected and fostering an informed non-judgemental approach to the victims of traumatic experiences. The importance of the individual guiding the process is central to the handbook relating to the current refugees in Ireland (Ryan et al., 2022). This same caution around retraumatisation has restricted direct research with domestic violence and was challenged by Corbin and Morse (2003) and later by the work of Houghton (2015). Young people have expressed confidence in being experts on their own lives and regulating their research experiences (Evang and Øverlien, 2014; Cody, 2017).

The implementation of safe effective TIP training for staff, educators and students has shown effective results when delivered within good practice. The tension between addressing the long-term deleterious effects of ACEs and maintaining a safe and supportive environment for the school and wider community provides the central focus. Further research into the lived experience of educators, students and families would inform this development.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer PM declared a shared affiliation with the author to the handling editor at the time of review.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alisic, E., Bus, M., Dulack, W., Pennings, L., and Splinter, J. (2012). Teachers’ experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. J. Trauma. Stress 25, 98–101. doi: 10.1002/jts.20709

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Bremner, J. D., Walker, J. D., Whitfield, C., Perry, B. D., et al. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 256, 174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4

Banks, R. B. Y., and Meyer, J. (2017). Childhood trauma in today’s urban classroom: moving beyond the therapist’s office. Educ. Found. 30, 63–75.

Bellis, M. A., Ashton, K., Hughes, K., Ford, K., Bishop, J., and Paranjothy, S. (2016). Welsh Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE). Liverpool: Public Health Wales.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2018). Why do you work with struggling students? Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 116–142. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n2.7

Burgess, D. A., and Phifer, L. W. (2013). “Students exposed to domestic violence,” in Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students, eds E. Rossen and R. Hull (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 129–139. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199766529.003.0009

Burke Harris, N. (2014). How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime. In TEDMED2014 (Producer). New York, NY: TedTalk.

Bywaters, P. (2017). Identifying and Understanding Inequalities in Child Welfare Intervention Rates: Comparative Studies in four UK Countries. Briefing Paper 1. London: Nuffield Foundation.

Carello, J., and Butler, L. D. (2014). Potentially perilous pedagogies: teaching trauma is not the same as trauma-informed teaching. J. Trauma Dissociation 15, 153–168. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2014.867571

Cody, C. (2017). ‘We have personal experience to share, it makes it real’: young people’s views on their role in sexual violence prevention efforts. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 79, 221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.015

Cohen, D. K., and Mehta, J. D. (2017). Why reform sometimes succeeds: understanding the conditions that produce reforms that last. Am. Educ. Res. J. 54, 644–690. doi: 10.3102/0002831217700078

Corbin, J., and Morse, J. M. (2003). The unstructured interactive interview: issues of reciprocity and risks when dealing with sensitive topics. Qual. Inq. 9, 335–354. doi: 10.1177/1077800403009003001

Crosby, S., Howell, P., and Thomas, S. (2018b). Social justice education through trauma-informed teaching. Middle Sch. J. 49, 15–23. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2018.1488470

Crosby, S., Day, A., Somers, C., and Baroni, B. (2018a). Avoiding school suspension: assessment of a trauma-informed intervention with court-involved, female students. Prev. Sch. Fail. 62, 229–237. doi: 10.1080/1045988X.2018.1431873

Dauber, S., Lotsos, K., and Pulido, M. (2015). Treatment of complex trauma on the front lines: a preliminary look at child outcomes in an agency sample. Child Adolesc. Social Work J. 32, 529–543. doi: 10.1007/s10560-015-0393-5

Dods, J. (2015). Bringing trauma to school: the educational experience of three youths. Exceptionality Educ. Int. 25, 112–135. doi: 10.5206/eei.v25i1.7719

Douglass, A., Chickerella, R., and Maroney, M. (2021). Becoming trauma-informed: a case study of early educator professional development and organizational change. J. Early Child. Teach. Educ. 42, 182–202. doi: 10.1080/10901027.2021.1918296

Elias, M. J. (2019). What if the doors of every schoolhouse opened to social-emotional learning tomorrow: reflections on how to feasibly scale up high-quality SEL. Educ. Psychol. 54, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1636655

Ellison, D., Wynard, T., Walton-Fisette, J. L., and Benes, S. (2020). Preparing the next generation of health and physical educators through trauma-informed programs. J. Phys. Educ. Recreat. Dance 91, 30–40. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2020.1811623

Evang, A., and Øverlien, C. (2014). ‘If you look, you have to leave’: young children regulating research interviews about experiences of domestic violence. J. Early Child. Res. 13, 113–125. doi: 10.1177/1476718X14538595

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 14, 774–786. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Gilmartin, D., McElvaney, R., and Corbally, M. (2022). “Talk to me like I’m a human” an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the psychotherapy experiences of young people in foster care in Ireland. Couns. Psychol. Q. 1–23. doi: 10.1080/09515070.2022.2062702

Gorski, P. (2020). How trauma-informed are we, really? To fully support students, schools must attend to the trauma that occurs within their own institutional cultures. Educ. Leadersh. 78, 14–19.

Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., and Durlak, J. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future Child. 27, 13–32. doi: 10.1353/foc.2017.0001

Hickey, G., Smith, S., O’Sullivan, L., McGill, L., Kenny, M., MacIntyre, D., et al. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed practices in second chance education settings in the republic of Ireland: an inquiry-based study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 118, (Suppl. 2):105338. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105338

Houghton, C. (2015). Young people’s perspectives on participatory ethics: agency, power and impact in domestic abuse research and policy-making. Child Abuse Rev. 24, 235–248. doi: 10.1002/car.2407

Houghton, C., and Voice Against Violence [VAV] (2011). Shaping the Future: One Voice at a Time: Tackling Domestic Abuse through the Voice of the Young. Scotland: VAV.

Howell, P. B., Thomas, S., Sweeney, D., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Moving beyond schedules, testing and other duties as deemed necessary by the principal: the school counselor’s role in trauma informed practices. Middle Sch. J. 50, 26–34. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2019.1650548

Hultmann, O., and Broberg, A. G. (2016). Family violence and other potentially traumatic interpersonal events among 9- to 17-year-old children attending an outpatient psychiatric clinic. J. Interpers. Violence 31, 2958–2986. doi: 10.1177/0886260515584335

Koslouski, J. B., and Chafouleas, S. M. (2022). Key considerations in delivering trauma-informed professional learning for educators. Front. Educ. 7:853020.

Lucio, R., and Nelson, T. L. (2016). Effective practices in the treatment of trauma in children and adolescents: from guidelines to organizational practices. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work 13, 469–478. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2016.1166839

Luthar, S. S., and Mendes, S. H. (2020). Trauma-informed schools: supporting educators as they support the children. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 8, 147–157. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1721385

Mulholland, M., and O’Toole, C. (2021). When it matters most: a trauma-informed, outdoor learning programme to support children’s wellbeing during COVID-19 and beyond. Ir. Educ. Stud. 40, 329–340. doi: 10.1080/03323315.2021.1915843

Murphey, D., and Sacks, V. (2019). Supporting students with adverse childhood experiences: how educators and schools can help. Am. Educ. 43, 8–11.

O’Gorman, S. (2018). The case for integrating trauma informed family therapy clinical practice within the school context. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 46, 557–565. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2017.1407919

Pemberton, J. V., and Edeburn, E. K. (2021). BECOMING A TRAUMA-INFORMED EDUCATIONAL COMMUNITY WITH UNDERSERVED STUDENTS OF COLOR: what educators need to know. Curric. Teach. Dialogue 23, 181–196.

Perkins, S., and Graham-Bermann, S. (2012). Violence exposure and the development of school-related functioning: mental health, neurocognition, and learning. Aggress. Violent Behav. 17, 89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2011.10.001

Perry, D. L., and Daniels, M. L. (2016). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: a pilot study. Sch. Ment. Health 8, 177–188. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9182-3

Radford, L., Corral, S., Bradley, C., and Fisher, H. L. (2013). The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse Negl. 37, 801–813. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.004

Romero, V. E., Robertson, R., and Warner, A. (2018). Building Resilience in Students Impacted by Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Whole-Staff Approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin press.

Ryan, M., Elaine, M., Rogers, E., Miller, I., Mc Hugh, S., Carey, A., et al. (2022). Not ReLIVING- But LIVING. Dublin: The Psychological Society of Ireland.

Stipp, B., and Kilpatrick, L. (2021). Trust-based relational intervention as a trauma-informed teaching approach. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 13, 67–82. doi: 10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1

Streeck-Fischer, A., and van der Kolk, B. A. (2000). Down will come baby, cradle and all: diagnostic and therapeutic implications of chronic trauma on child development. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 34, 903–918. doi: 10.1080/000486700265

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD.

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: a meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev. 88, 1156–1171. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12864

Thomas, S., Crosby, S., and Vanderhaar, J. (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: an interdisciplinary review of research. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 422–452. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821123

Thrive (2021). Trauma Informed Practice in Second Chance Education Settings: Guidelines for Educators. Available Online at: https://thrivelearning.eu/english/ (accessed March 6, 2022).

Treisman, K. (2018). A Therapeutic Treasure Box for Working with Children and Adolescents with Developmental Trauma. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Wegman, L., and O’Banion, A. M. (2013). “Students affected by physical and emotional abuse,” in Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students, eds E. Rossen and R. Hull (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 220–228. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780199766529.003.0015

Keywords: trauma informed classroom, adverse childhood experiences, trauma informed practice, educators, students, implementation, secondary trauma

Citation: Sweetman N (2022) What Is a Trauma Informed Classroom? What Are the Benefits and Challenges Involved? Front. Educ. 7:914448. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.914448

Received: 06 April 2022; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 14 July 2022.

Edited by:

Waganesh A. Zeleke, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Patricia McCarthy, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandCopyright © 2022 Sweetman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Norah Sweetman, c3dlZXRtYW5AdGNkLmll

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.