Abstract

The existence and development of public schools is influenced by a plethora of factors. Through the creation of education policies, any state education system is striving to accomplish specific goals. Both informal and formal private schooling is taking the lead in all cultures and societies. Unmistakably, the distinction between private and public schools is evident. However, given the different circumstances, choosing the best alternative for a child is regularly a fervently discussed topic among parents. There is no universal answer to the question whether private schools are actually better than or superior to the public schools. Our research aimed to describe the school choice process, it focuses on unveiling the factors and their interrelation while the parent choosing between two types of schools—private and public. First of all, the research aims to describe the parent’s perception of achieving success at school, what is the base for such belief, what the sentence—“School—base of future success” actually mean. How important is so called social index? The significance of the reputation and prestige of the educational institution during school choice process—as a guarantee for future success. The key questions for the research were as follows: (1) How interested the parents are to be actively involved in school choice process and spend certain period of time for that? (2) What factors are considered by the parents during school choice and what is the source they receive information from? (3) Does the family’s socioeconomic condition and the kids gender have influence on the process? It’s worth mentioning that, generally the research results fully coincide with the school choice theory arguments and the research findings conducted in the similar field. All these are described and presented in the first part of the article. The probabilities listed on the base of the current data, that the information source, the parent’s information level, the parents’ engagement as well as the family’s socioeconomic and demographic status play integral role in the school choice process appeared to be genuine. Apparently, the parents are much interested to provide perfect future for their kids, though socioeconomic conditions, environment, poor educational system limits their choice. Once our results compared to the existing literature and theory, one can see that our study conducted in Georgia follows the trends of the developed countries, known as the “Heyneman-Loxley effect.”

Literature review

Based on its multifactorial character, the school selection process is a popular issue of research and attracts the attention of various researchers and educational theorists. For instance, Fowler stated that choosing a school can easily be the most controversial education policy issue of any time (Fowler, 2002).

Generally, the discussion issues are following: should the parent be given freedom during the school choice process, if yes, what is the maximum level of interference, as well as should the government support the increased competition in the education sphere, if yes, give the hints how? The first part of the literature review will cover the Q & A regarding the abovementioned issues, later specifically the selection/choice process and the factors influencing the process itself will be discussed.

Private and public schools

The scholars attempt to outline private education as accurately as possible. Lewis and Patrinos (2012) identify three characteristics distinguishing private education from the public education: funding, sponsorship, and management/control.

The meaning of the term “public” and “private” has changed through years. Its meaning may vary from country to country. Private schools are often state-funded. For instance, charter schools in the US are the best examples. Georgia has a voucher system that implies that the private sector receives these vouchers additionally to extra payment from parents. Therefore, it is difficult to come up with a particular definition for private schools.

In developing countries, the private education system is a guarantor of academic and social security. Since the state fails to provide primary education for all, in some countries, private education is the only way to get quality education, filling the gap left by the state education system.

Many scholars focus on identifying the difference between the private and the public schools. They all undoubtedly agree that public and private schools are significantly different in terms of environment and management. “The private school is characterized by several factors and characteristics, admittedly associated with efficiency, they belong to different sectors of the market and policy controls, they vary in terms of a social control method: state schools represent a hierarchical system of subordination that is structured by democratic politics, while private schools have a wider degree of autonomy, controlled by the market demand and delivery mechanism” (Chubb and Moe, 1988).

Freedom in school selection/Choice process

According to John Stuart Mill “the objections which are urged with reason against state education don’t apply to the enforcement of education by the state, but to the state taking upon itself to direct that education…. All that has been said of the importance of individuality of character, and diversity in opinions and modes of conduct, involves, as of the same unspeakable importance, diversity of educations” (Allison, 2015).1

Mill’s “Diversity of Education” idea came to spotlight together with the opportunity to develop the school selection/choice right, that happened in Anglo-Saxon reality.

Friedman’s (1955) proposed idea of educational vouchers, which would encourage the introduction of competition in the education, inspired the new theoretical course to be established giving the base to the innovation reformation policy in USA and then in the whole world.

Generally, in reforming states and not only there, there is rising tendency of the parents’ distrust toward public schools, meaning that they will fail to meet their kids demands and goals (it is no surprise that parents are scrambling for enrollment in the limited functional sub-system; Blake and Mestry, 2021). Many parents doubt the government’s dedication for providing the educational system with the appropriate standards.

School selection/choice right is an issue of enduring discussion. According to Goodwin (2009) the arguments named by the opponents of the choice can be listed as follows: (a) The excising market is poor in managing certain issues; (b) The choice in education necessarily has deleterious effects on social justice. It underlines and deepens the excising inequality; (c) The choice is not an effective tool for increasing the standard. Thus, out of the above listed three opinions, the very first is an ideological argument in general, so in this particular article we will focus on the rest two issues.

According to the choice proponents the school selection/choice process is equal to other similar decisions, which the parents make on the base of the conditions created by the market, thus the parent, as a consumer should have freedom of choice and right either. At the same time the choice proponents are focusing not only on the parents’ rights of freedom of choice, but they assure that the freedom of choice is ultimate stimuli for the schools’ improvement (Davies and Aurini, 2011, p. 460).

Besides this, the parents are well aware of their kids knowing their strength and weakness, as well as their interests and demands. Thus they appear to be the best of the best choice and decision makers. In parallel with this, if the government provides the selection/choice process funding, the poor (not well-off) families will also have opportunity to select the school they favor (Friedman and Friedman, 1980).

According to minor chance of choosing in the traditional schooling system too, though only rich families, who either can pay the private school fee, or move closer to the better school, can afford this. Thus only reformed system, when there is a public funding for providing freedom of choice, can give chance to the poor (not well-off) families to make a choice.

Providing school selection/choice can be the merit of the following: by extending the variety of school types, by expanding the publicly available information about schools, and by expanding the parental capabilities to choose (Davies and Aurini, 2011, p. 460).

The following ideas can be used to provide the appropriate public funding for school choice: opening catchment programs, the creation of specialty schools within the public school boards, partial funding of independent schools, charter schools, voucher programs, laws that facilitate home-schooling, and tax credits for private school tuition.

All the above listed initiatives were vast popular in USA during last decades of the twentieth century and later the similar tendency was spread in other countries too (Belfield and Levin, 2002; Merrifield, 2008; Hess, 2009, e.g., Hepburn, 2001; Robson and Hepburn, 2002; Davies and Aurini, 2011).

The reform launched in the last decade of the twentieth century made it clear that the school choice right will reduce the bureaucratic control, decentralization and will improve the schooling system in general (Clune, 1993).

Compering educational pluralism2 with uniformity, the current mechanisms in use (tax credits, vouchers, scholarships) Berner (2016) concluded that “[pluralism] is more intellectually honest and democratically aligned … and schools with distinctive missions often produce better academic and civic outcomes for students.”

Generally, school choice includes 2 aspects: (a) Policy or regulation defining the equality of power for private and public schools; (b) Public funding, providing the parent’s freedom of choice on behalf of both for public or private schools (Robershaw et al., 2022).

In theoretical literature, during discussing the schools’ choice issue the focus is made on the following three factors: (a) School choice results, which are generally measured on the base of the students’ evaluation; (b) The schools provide the delivery of quality education, meaning how the school responds the market demand; (c) During the selection/choice which aspects are the vast priority for the parents, and how they behave; We focuses exactly on these issues.

School choice process by the parents

When we are discussing the parents’ role in the school choice process, 2 fundamental questions should be asked: (1) Are the parents motivated enough to participate in the process and use all the chances existing on the market? (2) What are the key issues the parents pay the most attention during the choosing process? In other words, 2 things should be clear while talking about the parents: (1) What they demand from the school; (2) Are they capable enough to evaluate each school quality and make rational decision for their kids during the school choice process, or will the government be the better variant for that.

The school choice proponents assume that the most parents desire school variety, are primarily motivated to seek academic quality, and will use available information on achievement when selecting schools. Opponents doubt these assumptions, countering that many parents are more interested in a school’s exclusiveness rather than its pedagogical quality, and that parents use criteria other than test scores when selecting the schools (Davies and Aurini, 2011).

The school choosing proponents stress the revitalization of public education through the creation of private alternatives, thus enhancing parental involvement, satisfaction, empowerment, and sense of community, and resulting in improved student achievement (Chubb and Moe, 1988; Driscoll and Kerchner, 1999; Smrekar and Goldring, 1999).

According to them this system prepares a solid base for competition between the schools as a result of which the schools appear to be more responsive to the needs and interests of parents and students by providing different types of programs for different types of families (Bosetti, 2007). Thus, on the one hand the individual demands from the students and their parents, and on the other hand the high competition between the schools should make the educational institutions to be attentive toward their clients (parents and students) demands, to attract more students which mean more funds as well.

Though according to the opponents, if the parents don’t have desire or initiative to participate in the school choice process, the choosing system will fail to work and will never become the alternative of the traditional public school. On the other hand, the public schools own more formal and familiar tools and mechanism, which theoretically should help the parents in decision-making. The critics also underline that during the school choosing “parents are able to select their own vision of the ‘good life’ without considering the social goals. This could lead to a loss of diversity and educationally sound public schools and democratic values” (Erickson, 2017).

At the same time “school choice may result in the creation of value communities that reflect ‘little fiefdoms’ that cater to the needs, values, and interests of particular groups. This contributes to the further social fragmentation of society and a two-tier education system” (Gewirtz et al., 1995; Fuller et al., 1996). And this prioritizes the well-off middle class of the society, who owns social and cultural capital for gaining the appropriate information (Bosetti, 2007). For defining the social capital, let’s use Bourdieu’s explanation: “Social capital is the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition [.]” (Bourdieu, 1986). In our case, the parents’ social capital is defined they their own circle/environment, who helps them to have access to the appropriate information for making proper decision (Corcoran and Jennings, 2020).

To its end, the family’s cultural capital is “knowledge and skills acquired over time, through ‘socialization and education that exist within us,’ ‘material objects or cultural goods,’ and ‘institutional acceptance or recognition in the form of academic qualification and credentials”’ (Bourdieu, 1986). Frequently the family’s socioeconomic status is defined as the best indicator for outlining the family’s cultural capital (Robershaw et al., 2022). When we are talking about the maintaining the existing social configuration and deepening the segregation danger while school choice process, Gorard, Fitz research is worth mentioning. The research results showed that, in 1988 the fulfillment of the Education Reform Act3 didn’t cause any of the above listed results in the schools of England and Wales. According to Bosetti (2004) rational choice theory suggests that parents are utility maximizers who make decisions from clear value preferences, and that they can be relied upon to pursue the best interests of their children.

At the same time, the theory says that they are able to demand effective action from local schools and teachers. Though the modern researches show that rational choice theory is totally useless to explain the school choice process from the parents (Jabbar and Lenhoff, 2020).

The rational choice model totally rejects the importance of the parent’s social network, the fact how the preferences of the different groups vary or what harm can the lack of information bring during the school choice process (Levin, 2009).

One of the approaches used for studying the school choice is the Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) described by Engeström in 2001.4 In case of studying the school choice this covers multiple factors, which may influence each and every individual during his/her school choice process.

It’s worth considering that each and every individual’s approach and interpretation regarding the school choice goals and objectives, at least slightly differ. According to Sullo (2011) “choice theory posits that an individual’s behavior or choices they make are driven by a never-ending quest to satisfy five genetically driven needs and four fundamental psychological needs” (Blake and Mestry, 2021). The critics frequently say that during the school choice process, the parents may prioritize their choice due to convenience or considering certain build-in activities including sports over the schools’ academic level (Harris and Larsen, 2015). According to Erickson (2017), its beyond sophisticated to measure the academic level. It’s even more sophisticated, to define its real meaning as it includes exams results, teachers’ quality, educational environments and infrastructure, as well as educational programs. He also underlines that, generally it’s not fair the parents to pay key attention only to the academic level as the families’ demands and goals differ.

What factors influence the school choice

Generally, the school choice is quite a complex issue and is the mix of religion, practical demands and opportunities correspondingly. It’s widely spread that those who believe in the vast necessity of freedom of choice, they use this opportunity/right. Would-be choosers are seen to want more input into school decisions, more responsive educators, and more transparent information about school performance. Furthermore, choice is seen to be particularly popular among parents who are deeply involved in their children’s schooling (Davies and Aurini, 2011).

In the developing states, the parents progressively acknowledge the increased value of the education for their kids’ future and for creating priceless opportunities in their lives. Thus, this doubtlessly upsurges the school choice process significance. It’s noteworthy that those parents who are actively involved in the school choice process, are also actively engaged in their kids’ education progression and appear happier with the school compared with those, who absolutely are not involved in the procedure (Bosetti, 2007). Lee et al. (2021) were researching the interdependency of quality and choice. On the base of the research they identified three conclusions: (a) The parents are happier when there is an opportunity to choose confirming that this makes the process much more fair; (b) Though later evolution of the selection objects (in case of experiment till 8) did not have any influence either on satisfaction quality or on the fairness level; (c) Whether performance declines or increases does not affect the effect of provider choice on satisfaction, and, by itself, performance decline lowers satisfaction and perceptions of fairness, consistent with what would be expected from the findings of previous research on public service performance outcomes and satisfaction.

According to Coleman et al. (1982) when a person has to make an important decision, he/she starts to gather information regarding the issue. The situation is all the same with the parent, who has to make choice about his/her kid’s school. During the decision-making process the parent considers his/her personal values and the subjective perception of the existing educational system. The appropriate information is gathered through the parent’s social and professional circle/environment. Thus, it’s logical that those parents who have limited access to valuable and relevant information have trouble to make well-informed choice (Smrekar and Goldring, 1999). Social-economic factors play integral role in the selection/choice process, to be more precise, meaning the parents’ education level and income (Bosetti, 2007). Many scholars mention that the level for having chance to make informed choice depends on the family’s socioeconomic and demographic parameters.

To be more precise, socioeconomic status is seen to provide the knowledge and finances needed to engage in choice, while dominant racial and ethnic groups are seen to be motivated to segregate themselves from minorities (for a review, see Lauen, 2007).

Davies and Aurini (2011) researches show that: (a) The majority of Canadian parents support the freedom of choice right; (b) The using of the right of choice depends on socioeconomic and demographic indicators—in reality the parents with higher education use the right of choice more actively. At the same time, less educated parents, as well as ethnic minorities, express eagerness to support the freedom of choice, this means that they would use the chance if they had the opportunity. (c) Third, a mix of educational attitudes predicted choosing; the most consistent was that parents with higher levels of participation in their children’s schooling tended to do more choosing (Davies and Aurini, 2011, p. 472).

According to Bosetti (2007) research the educated, employed parents with high income are more active in using the right of choice. At the same time the researches show that the families with high income prefer private schools (Bosetti and Pyryt, 2007) and in case of need, they are ready to move to the expensive districts to live in (Goyette, 2008).

Bosetti (2007) research also showed the role of family condition in school choice process, mainly in case of religious private schools. The vast majority of parents interviewed, indicated that they are married, with religious private school parents being most likely to be married (95%). It’s quite interesting that the parents of the alternative and secular private schools, in frequent cases appear to be divorced or single parents. It’s also worth mentioning that, the parents of the private religious schools’ students own similar or lower socioeconomic status compared with the parents of the public schools’ students’ (Bosetti, 2007). All abovementioned indicate that while religious school choice the parents prioritize the values and they are ready to pay ‘certain price’ for their kids’ future.

It should also be considered that the parents’ socioeconomic status also defines their perception regarding the importance of education. Hatcher (1998) explains that “working-class young people can maintain their class position, and even achieve some upward mobility, simply by completing compulsory secondary education,” when middle-class families are more anxious about the educational options for their children because the benefits of attaining certain educational qualifications and credentials are higher, and the risk of social demotion greater. Therefore, because of these perceived high stakes, middle-class parents are more likely to be predisposed to engage in education markets (Bosetti, 2007).

Some scholars think that, while analyzing school choice, the kid’s gender should also be discussed as one of the integral factors. According to them, the parents have different approaches toward daughters’ and sons’ education. Bellani and Ortiz-Gersavi (2022) research shows that in Italy, for the low income families “parental time preferences matter more for sons than for daughters of lowly educated parents. This gender effect is found both for upper secondary choices and for entry into higher education.” They explain this with different expectations linked to their children. The parents think that sons have higher chance for the career promotion compared with daughters, who should mainly focus on building good family. Such different expectation becomes base for different attitude while school choice. Sahoo (2017) shares similar tendencies though on the example of India. According to his research and analysis households choose to provide their sons rather than daughters with an education which is more expensive and which they perceive to be better in quality. Such attitude is unveiled while selecting the school type—if the family has to choose, which kid should get private (high quality) education, in major cases they send sons to the private schools, as for the daughters, they are sent to public (lower education quality) schools. As it was underlined above for several times, the valuable info gained about the school appears to be one of the main factors for the parent to make final decision. Key sources for the information gathering are friends, neighbors, other parents, as well as teachers, school administration staff who share valuable info to the parents before they make any choice. This once again underlines the importance of the social-cultural role while making final decision from the parent. Thus because of this, the school choice theory opponents assure that, the parents with lower socioeconomic status have limited access to the useful and adequate info. Hence, they are lack of motivation to reserve themselves from sending kids to the neighboring schools, meaning that they won’t spend much time and energy to seek for better options. As a result of this, according to Bosetti (2007) research, nearly half of the public schools’ student’s parents choose the schools before having appropriate information about the certain institution, and this basically exceeds the data regarding the alternative and private schools (21 and 7%, respectively).

Thus, to sum up Bosetti (2007) research results, for the private secular schools’ parents, the most important factors are the class size, values, teaching style and academic reputation; in case of private religious schools—the most important are values and academic reputation; as for the family/public schools—the most significant factor is closeness to house, then comes academic reputation, teachers’ qualification and teaching style.

To keep it simple, the private schools’ students’ parents do their best to choose school based on their kids’ individualism and demands; though public schools’ students’ parents simply accept the existing reality; only exceptions are the lower class religious parents, for whom religion is much important and they are ready to make certain commitments above their power and provide proper education for their kids in private religious schools.

Sending kids in public schools in frequent cases is the result of limited alternatives or just limited access to the information (parents just don’t have info about other educational facilities). As a rule, the parents of the public schools’ kids, state that if the government provide funding, they would have sent their kids to the private schools with the great pleasure (Bosetti, 2007).

According to Blake and Mestry (2021), in frequent cases the parents have utopic expectations as a result of which they fail to make proper decision. This happens when the parent is lack of proper knowledge/experience regarding educational system or has limited financial condition.

It’s obvious that the family’s financial condition influences the freedom of choice, vividly showing the government’s policy to support the school selection/choice principle to be fair and right, because “without tuition vouchers or bursaries the competitive market pressures generated by these parents is restricted to charter schools or alternative schools in the public education system.” This once again shows that while making school choice, the parents personal attitude is vast important, as according to it, the parents make clear what kind of education, skills and values should their kids’ elaborate during their years at school (Wells, 2000).

As a rule, the parents agree that the key function of the school is to deliver academic knowledge, good working skills, self-discipline, and critical thinking to the kids, though different groups of parents differently prioritize those characters.

To sum up, the parents’ final decision regarding the school choice is defined by following factors: family characters (socioeconomic status, education, income etc.); other demographic characters—kid’s educational demands; Parent’s knowledge of system/appropriate information (exciting school types, exciting school choice programs/policy, and opportunities); Parental perspective of school choice (exciting school types, exciting school choice programs/policy, and opportunities) (Robershaw et al., 2022).

Erickson (2017) underlines three patterns in literature: (1) There is great consistency in parents’ stated preferences of school characteristics across choice programs; (2) Parents value academic quality, but it is not always their most prized school feature; (3) Parents make trade-offs among their preferences when selecting a school.”

According to Fowler (2002) “School choice is going to continue to expand whether we like it or not. Parents like the idea of being able to select their children’s schools, and public support for the idea has grown enormously over the last decade or so.”

It is common knowledge that providing education is a parent’s responsibility, and a parent tries to create the best learning environment for a child. It is the parent’s responsibility to take care of a child’s health, safety, development, and success. Below is listed literature that identifies ten key factors affecting parental decision-making regarding the school type selection: (1) parental social status; (2) income; (3) school syllabus; (4) school environment/infrastructure; (5) school achievement/location; (6) location; (7) qualification of teachers; (8) school image/reputation; (9) the role of religion or moral values in school choice; (10) social selection and social experience for children.

The Heyneman-Loxley effect

According to the study of Heyneman and Loxley (1983), the family and school impact on students’ academic achievement is highly depended on the degree of economic development of a country/community. Socioeconomic status (SAS- socioeconomic status). While the family impact is more significant in developed countries, school resources and quality of school education is a more reliable determinant for low-income countries.

The research has also shown that when it comes to the mathematics and science, high-income countries have higher academic achievements compared with low-income countries. This finding has been named the “Heyneman-Loxley Effect.” To explain it briefly, Heyneman and Loxley developed a theory in which family characteristics correlated with school characteristics and student achievement rates.

This case was later explained by Baker et al. (2002) as follows: Education policy in the developed countries and existing areas provide a certain degree of public schooling, creating the environment where the distinction between public and private schools is not so significant. What we are left with is a family socioeconomic condition as a key distinctive feature. In less-developed countries, a uniform minimum standard of schooling does not exist, and therefore, a school factor may turn out to be a decisive determinant, exceeding the quantity of family factors.

After the study referenced above, no study has been carried out in various countries utilizing the same standard until 1990. There was just one—we would be able to generate results and compare the data. Since 1990, this has changed with single-standard international studies that were conducted in different countries (TIMSS, PISA). However, the research conducted under the auspices of TIMSS (1994), considered a minimal number of the family characteristics—such as mothers’ and fathers’ education and the number of books in the family. The research analysis led in 1994 failed to prove the “Heyneman—Loxley effect.” Yes, there were existing differences, but not significant enough in terms of variables. A 21-year-old analysis showed that among three factors—school quality, family socioeconomic status, and student academic achievement, are not interrelated with the country’s economic performance as described above—the authors conclude that the “Heyneman-Loxley effect” either did not exist or it has undergone the transformation during 21 years. One of the objectives of our research/study is to check the abovementioned conclusion’s accuracy in case of Georgia, as an example country.

Development of education system in Georgia

Prior to the Proclamation of the First Republic on May 26, 1918, Georgia was a part of Tsarist Russia and the school system was governed by the rules of the Russian Empire. The gradual subjugation of the Georgian kingdoms by the Russian Empire (first half of the nineteenth century) coincided with an ongoing school reform in the empire.

A fundamental educational reform, prepared by the closest associates of Tsar Alexander I (1777--1825), created a hierarchical school system headed by the Ministry of Public Education and regulated by The Charter of the Universities of the Russian Empire (1803). It included six educational regions with four types of institutions beyond elementary schools: parish schools, uyezd (district) schools, gymnasiums, and universities. Russian education evolved with both minor and major changes. In 1828 the course of study at gymnasiums was extended to 7 years, with priority given to classical education. Schools with instruction in Armenian, Georgian, and Azerbaijan languages were opened in the Caucasus. The turning point in the development of the Russian educational system was the reform of the 1860s carried out as part of cardinal transformations under Czar/King Alexander II (1818--1881). The Statute on Elementary Public Schools of 1864 declared elementary education open to all social ranks. The reform strongly encouraged private and local initiative in establishing new schools.5

In 1918–1921, the Democratic Republic of Georgia implemented crucial reforms in the field of education. The Law on Public Education was adopted. The education system was based on the principles of democracy, equality, universality, human rights. Schools taught the following subjects: Georgian language and speech, Russian and world literature, second foreign language (French, German, or English), history, political economy, law, psychology, logic, natural sciences and mathematics, hygiene, physical education, chanting and music, handicrafts and fancywork/needlework. Latin was an elective/optional subject. Alongside with the world history and non-Georgian language, teaching Georgian language and Georgian history was compulsory in all non-Georgian schools. At this time there were some privately operated schools. Their compliance with the country’s legislation and students and teachers’ rights were all monitored by the government. A significant number of schools were based in Tbilisi (Georgia). There were some private schools in Kutaisi as well. Their programs, plans and textbooks were reviewed by Ministry of Education. The annexation of Georgia by Russia in 1921 was followed by the changes in the school system as well. In April 1921, by the decision of the Revcom of Georgia, the People’s Commissariat for Education was established. The first task of the Leninist Cultural Revolution was to eliminate/eradicate illiteracy and transform public education on a social basis. In 1921, a commission set up by the Department of People’s Commissariat for Education of the Georgian SSR drafted the Republic’s “Uniform Labor School Regulations.” It was to provide free, universal polytechnic education for both sexes in Georgia to expand the network of pre-school institutions that were the basic principles of the new Soviet public education system. The education system of the Soviet Union was a classical model of education that was introduced from Germany and Israel.

Elementary schools were called the “beginning/beginner” level (in Russian: начальное, nachalnoye), 4 and later 3 classes. Secondary schools were 7 and later 8 classes (required complete elementary school) and called “incomplete secondary education” (in Russian: неполное среднее образование, nepolnoye sredneye obrazavaniye). This level used to be compulsory for all children (since 1958–1963) and optional for under-educated adults (who could study in so-called “evening schools”). Since 1981, the “complete secondary education” level (10 or, in some republics, 11 years) was compulsory. 10 classes (11 classes in the Baltic States) of an ordinary school was called “secondary education” (in Russian: среднее образование, srednye obrazovanye—literally, “middle education”). PTUs, tekhnikums, and some military facilities formed a system of so-called “secondary specialized education” (in Russian: среднее специальное, sredneye spetsialnoye). PTU’s were vocational schools and trained students in a wide variety of skills ranging from mechanic to hairdresser. Completion of a PTU after primary school did not provide a full secondary diploma or a route to such a diploma (Grant, 1979).

Such was the education system in Georgia when the country declared its independence on April 9, 1991, which then gained international recognition in 1992.

The rise of private schools in Georgia has been growing for more than 20 years since its independence from the Soviet Union (see the map of modern Georgia in addition 1). Throughout this period, it has undergone several stages of development. The first Georgian private school was established in 1991. Since then, its number has been growing over the decades. The most dramatic jump was in 2005 and 2006. The reasons behind the drastic increase are many, though the most significant changes can be linked to economic growth and educational policy. Almost at this time, a new model of educational system management was introduced. The government chose to finance students but not educational institutions. An education voucher enables a parent to choose to spend the received fund either on private or public schooling. As a consequence, private schools receive up to 20 million GEL from the state budget. The education policy has increased not only the number of private schools but the number of students as well.

In the beginning of the 2021/2022 academic year, there were 2,313 general education institutions in Georgia, including 2,086 public, and 227 private schools (National Statistics Office of Georgia, 2019).6 Prior to the reform, the public education system in Georgia was not responsible toward the government. The system was overloaded with bureaucratic functionaries that had dozens of overlapping obligations and duties, characterized by the lack of effective coordination, administration, and financial management mechanisms.

The introduction of a voucher system in the field of school education, has transformed the system, which was under state control. The market economic principle came into play and developed a supply and demand marketing mechanism for education. The introduction of the voucher funding in the school education served to improve school education and environment for a parental choice. School funding has also been a source for private schools. Despite the state voucher funding, the primary input is the fee paid by the parents. The data shows that fee is higher in cities, and it is significantly higher in Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia.

Rarely schools have sponsors or partner organizations that fund them. In most cases, this involves initial infrastructure development and school running costs (utility costs and hand-over costs). The patterns of manufacturing and education partnerships which are common in the western countries are rarely found in Georgia.

However, along with the advantages, this process has its adverse sides. The increased public funding has expanded the state dependence, letting the state interfere in the operation of private schools, invoking more standardization of the curriculum—the new systems of issuing school certificates through a unified national exam, the so-called branding proposed system. The latter encourages private schools to modify their success criteria (in some cases to worsen it) exchange for certain benefits from the state.

Currently, the primary indicator of private schools’ weakness can be their dependence on the state and the lack of instruments necessary for internal financial sustainability.

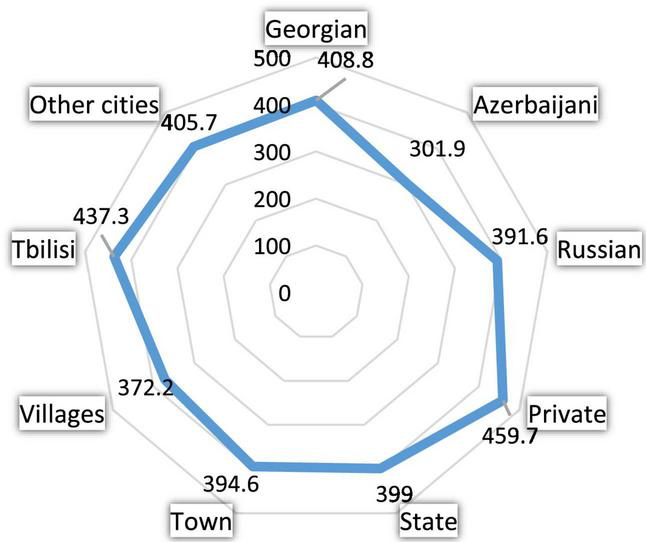

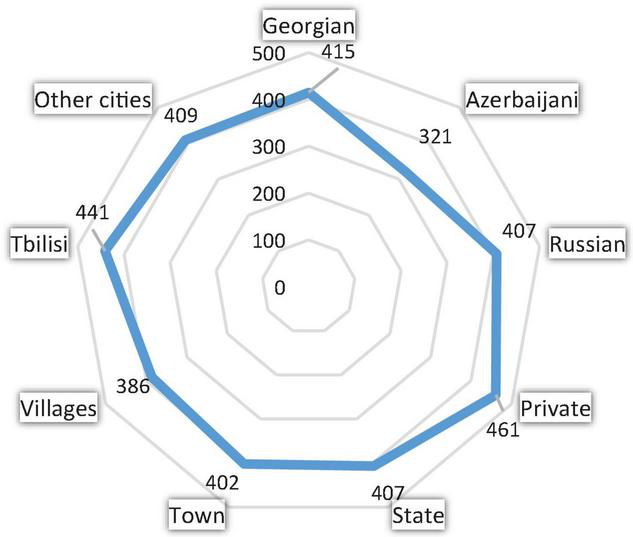

The researches show that the private schools are far more successful considering academic performance compared with the public ones. Figures 1, 2 shows the quality level difference between various types of schools (including private schools). The table demonstrates the private schools advantage over other public ones.7 TIMSS International Research of Study, 2015-2016.

FIGURE 1

Students’ grade in mathematics by type of schools.

FIGURE 2

Students’ grade in natural sciences by type of schools.

In private schools, higher academic performance level is the merit of not only quality learning, but various other reasons as well. Some private schools have their own policy and criteria of accepting the students, such as: testing and interview. Considering this factor, it may sound unfair to judge the schools according to their academic performance. The academic results depend not only on schooling surroundings, but on the conditions and support from the family either. Thus, because of this, it’s rather interesting point how the parent prioritizes the educational institution’s academic performance level during school choice process and final decision-making.

Research context and methodology

Goals and objectives of the research

The research aims to describe the school choice process, it focuses on unveiling the factors and their interrelation while the parent choosing between two types of schools—private and public. First of all, the research aims to describe the parent’s perception of achieving success at school, what is the base for such belief, what the sentence—“School—base of future success” actually mean. How important is so called social index? The significance of the reputation and prestige of the educational institution during school choice process—as a guarantee for future success.

The key questions for the research were as follows: (1) How interested the parents are to be actively involved in school choice process and spend certain period of time for that? (2) What factors are considered by the parents during school choice and what is the source they receive information from? (3) Does the family’s socioeconomic condition and the kids gender have influence on the process?

Considering the research objectives, so called structural questionnaire composing of 68 questions was prepared.

During composing the questionnaire, various factors were considered including: international experience, advice from field experts,8 comments and the research results9 conducted in Georgia.

Considering the reviewed literature, several acknowledgments were worked out:

- •

The parents have access to the information mainly through their social environment, as a result of this the parents of the private school students are far more informed regarding various aspects of school, compared with the parents of the public school students;

- •

The parents of the private school students are more motivated about the information gathering and are also more involved in the school choice process;

- •

In case of highly educated and well-off parent, the probability that he/she will send the kid to the private school is of course high, as private schooling is associated with better education;

- •

Selection criterion is much sophisticated and in frequent cases the social factor appears to be more important than academic performance of the school. This happens because neither private nor public school is capable of fully satisfying the parent’s demands.

Research methodology

The present study is a quantitative study of face-to-face interviews, conducted with a fully structured instrument. The average duration of an interview was 1 h. A pre-stratified three-stage cluster sampling was used for the study. 25 public, and 25 private schools were selected, and 12 students were randomly chosen (one student per class) from each selected school. Totally, 300 students were selected from each types of schools. The interviews were conducted with the parent/guardian of the selected student. The student in the selected class was chosen from the school journal through simple random sampling. If the parents of selected student were absent or refused to be interviewed, the parent of next student on the list was chosen. It should be mentioned that there was no significant difference in non-response rate between private and public schools. Such a sampling design for each student in Tbilisi guaranteed equal probabilities of being chosen. The field study was conducted in May and June 2017 (see details in Addition 2).

Research limits

The main limits of the research were limited resources and time, thus only Tbilisi schools appeared to be beneficiaries.

Thus we can’t talk about those parents’ choices, living in other cities. Though it’s also noteworthy that 50% of private schools located in Tbilisi balance this problem. Another error was that we didn’t have chance to use qualitative methodology while analyzing the quantitative research results (including more detailed interviews and/or focus groups).10 Hopefully these errors will be balanced through future researches.

Research main findings

The principle of choice

As the received data showed, the parents who decided to send the kid to the private school appeared to be far more informed regarding various aspects of schooling, compared with the parents of the public school students.

Comparing the average index of two groups of parents (private and public schools’ students’ parents) regarding the quality information gathering before sending kids to school is much significant: private—78.5%, public—63.9% (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Private | Public | Difference | |

| Was informed | |||

| School fee | 93.6% | 90.0% | 3.6% |

| School reputation | 92.4% | 83.8% | 8.6% |

| School academic performance | 81.2% | 61.7% | 19.5% |

| School infrastructure | 78.4% | 65.1% | 13.3% |

| School staff, teachers’ qualification | 80.0% | 59.8% | 20.1% |

| Teaching hours/duration each day | 86.8% | 76.3% | 10.4% |

| Number of students in class | 79.2% | 58.9% | 20.3% |

| Attitude toward the students | 79.2% | 59.5% | 19.6% |

| Transportation | 81.2% | 79.4% | 1.76% |

| Food | 76.8% | 67.6% | 9.2% |

| Additional activities (Music, dance, singing) | 75.6% | 57.3% | 18.2% |

| Preparing home task at school, the need of parent’s participation during the studying process | 81.6% | 56.7% | 24.9% |

| Teaching of religious subjects | 56.8% | 39.9% | 16.9% |

| Unconsidered/extra costs | 48.8% | 41.1% | 7.6% |

| Sports activity, encouraging healthy lifestyle | 70.4% | 43.0% | 27.4% |

| Communication with the representatives of specific social environment | 62.8% | 41.7% | 21.0% |

| Safe surroundings | 95.2% | 74.5% | 20.7% |

Do you have information about the school details before making decision?

Own results.

Besides the fact that private and public school students’ parents have different level of information regarding the educational institutions, there are other contradictions between them:

Access to information—the research showed significant difference between the private and public schools student’s parents’. The private schools’ students’ parents are more interested to receive valuable information happening in educational sphere through various channels including television (on a daily bases private-28,3, public-24.0), radio (on a daily bases private-3,8, public-3.1), internet (on a daily bases private-43,5, public-34.6) (Table 2).

TABLE 2

| Private schools students’ parents | Public schools students’ parents | |

| Daily | 43.5% | 34.6% |

| Couple of times a week | 14.9% | 18.1% |

| Once a week | 8.1% | 8.4% |

| Couple of times a month | 14.1% | 12.5% |

| Once a month | 8.9% | 12.1% |

| Couple of times a year | 6.0% | 4.0% |

| Never | 4.4% | 10.3% |

How often do you read about education sphere updates via internet?

Own results.

The quality of demand on the services offered by the school also differs: the private school consumers are far more demanding toward their school (that can be proved multiple times throughout the research) and demand on information is high too. That’s normal, as the private school student’s parents pay certain amount of money and their attitude is much demanding toward the service they receive, including the information sharing. Thus, the private school students’ parents are more informed compared with the public school students’ parents.

Social and Cultural Capital. According to the data, those who decided to send kids to private schools were influenced by their own social circle/friends, as 60% of the people they communicated with had their kids in private schools, the same was with the public schools—those who decided to send their kids to public school were influenced by their own social circle/friends as 92.5% of the people they communicated with had kids in public schools (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Private schools students’ parents | Public schools students’ parents | |

| Private school | 60.0% | 7.5% |

| Public school | 40.0% | 92.5% |

Where do your friends’ kids study (mainly)?

Own results.

Thus we can talk about (1) the sharp segmentation of the society, where the people are divided having their own social circle, and attitude toward private/public/state education system. (2) Education is very relevant for both groups of people and a serious issue of everyday discussion (private 20,8 and public 20,5—talks about education issues with their friends/relatives on a daily basis).

One more indicator showed such strict segmentation

On the following question: during the school choice process, did you make choice between public schools, private schools or both? The parents gave following answers:

63.5% of the private schools’ student’s parents were choosing only between private schools; 72.3% of the public schools’ student’s parents were choosing only between public schools (Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Criteria | Private school children’s parents | Public school children’s parents |

| From private schools only | 63.5% | 3.1% |

| From public schools only | 2.8% | 72.3% |

| Between public and private schools | 33.7% | 24.6% |

School selection criteria; 600 respondents, SE 4%.

Own results.

The parents’ education and income connection with school choice

The demographic questionnaire vividly showed serious difference between the private and public schools’ parents’ income. This can be seen by the following data (Table 5):

TABLE 5

| Private school children’s parents | Public school children’s parents | |

| High income/Rich | 3.2% | 0.9% |

| Between high and middle income | 20.9% | 9.0% |

| Middle income | 68.7% | 60.7% |

| Low income | 7.2% | 28.7% |

| Poor | 0.6% |

How would you rank your family’s social level?

Own results.

It also appeared that private schools’ students’ parents have better education (Table 6).

TABLE 6

| Private school children’s parents | Public school children’s parents | |

| Junior high school/high school | 2.8% | 8.7% |

| VAT | 7.2% | 13.0% |

| Incomplete higher education | 3.1% | 7.0% |

| Higher education | 86.9% | 73.1% |

Parents’ education.

Own results.

Both data show that the school choice is much linked to the parent’s education and income.

When the private schools’ students’ parents have higher education and good income (compared with the public schools’ students’ parents), the chance of sending their kids to private schools in future is inevitably high.

The gender of a child and a parent’s choice

Below in Table 7 is an official data set issued by the Ministry of Education—the number of students in private and public secondary schools by gender (October 2017).

TABLE 7

| School status | Girl | Boy | Girl% | Boy% |

| Private | 25,683 | 31,560 | 44.9% | 55.1% |

| Public | 248,187 | 269,562 | 47.9% | 52.1% |

Distribution of pupils in private and public schools.

Ministry of education.

The data showed that both in private and in public schools, boys outnumber girls. In a private school, this difference is even more noticeable. If the proportion of girls among public school students is 4.1% lower than the boys, this difference is 10.3% in private school.

That allows us to assume that while choosing a school (whether private or public), along with other factors, the child’s gender plays an important role. In other words, boys are slightly more likely to be taken to private schools than girls.

The research showed significant difference between the private and public schools’ students’ parents regarding the access to information. The parents of the private schools’ students have better access to information and media channels as well as they are more interested to be better informed. Here are listed the factors defining school choice:

- •

Different level of demand toward the schooling services;

- •

The parents’ social environment;

- •

The parents’ education;

- •

The parents’ income;

- •

Kid’s gender.

Selection criterion

According to the results, there is a low competition between the private and public schools.

There is a competitive environment between the private and public school sectors. A public school cannot compete with a private school. The low competitiveness of public schools is reflected in parents’ assessments of various factors.

During our study, 38 factors were identified that affected the parents’ decisions. The date was analyzed using multifactor dispersion analysis. The factors later were grouped into 10 factors according to the statistical significant (0.5 and more). The results are given in Table 8.

TABLE 8

| Criteria that are significant for private school | Criteria that are significant for public school | |

| School comfort, infrastructure, equipment | 0.56 | –0.51 |

| Teaching quality | 0.22 | –0.20 |

| Relationship between students and teacher | 0.24 | –0.22 |

| Development of students social and communication skills | 0.04 | –0.04 |

| No need of additional tuition | 0.12 | –0.11 |

| Parental engagement and orientation on parents | 0.12 | –0.11 |

| Students’ rights | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Sport and healthy life style | -0.02 | 0.02 |

| Sport and healthy life style | 0.22 | –0.20 |

| Preparing homework at school/extra study | 0.4 | 0.0 |

| Family income and socio-economic status | 0.56 | –0.51 |

School selection/choice criteria in Georgia? 600 respondents, SE 4%.

Own results.

The table shows that higher the evaluation is, the parents’ attitude and assessment of the similar factor is high too. Higher than 0.1 evaluation factor is much significant for the school review that for sure influences the parent’s school choice process. The figures listed above make clear how the average factor assessment indicator differs in case of private and public schools (high and low). For instance: #1 factor—comfort, material-technical base—private schools have higher than average evaluation, 0.56 points (on 10-point rating scale) to this direction, though the similar factor evaluation for the public schools totals 0.51 points (on 10-point rating scale).

Thus, in case of private schools, the highest evaluation is defined by school’s material-technical base—0.56 points. Next important indicator is relationship between students and teachers—0.24 points; as well as preparing homework at school/extra study—0.22 points; no need of additional tuition—0.12 points and parental engagement, orientation on parents—0.12 points. In case of public schools, the table above shows that the evaluation of the majority indicators is lower than average.

It’s also interesting to compare the abovementioned answers to the fact, why did they send their kids to that particular school? (Table 9).

TABLE 9

| Private school children’s parents | Public school children’s parents | |

| Good educational conditions | 57.0% | 31.0% |

| High quality education | 49.2% | 23.3% |

| Safe environment | 29.5% | 10.0% |

| It’s comfortable for parents, offering extra services including transportation, extra study | 28.3% | 5.3% |

| Prestigious | 11.5% | 3.0% |

| Close to living area | 9.0% | 31.7% |

| Affordable | 7.0% | 50.7% |

| The kid will have good friend as the majority of the students are from good families | 7.0% | 2.7% |

Why did you choose the school named by you?

Own results.

The data above shows that, in reality, during school choice process, the key factor for the private schools’ students’ parents appeared to be following: good educational conditions—57.0%; high quality education—49.2%; safe environment—29.2%, comfortable for parents, offering extra services including transportation, extra study—28.3%. As for the public schools’ students’ parents, during school choice process, the key factors were as follows: affordability—50.7%; closeness to living area—31.7%; good educational conditions—31.0%; high quality education—23.3%.

A private school choice is mainly determined by a “family (high) financial status” factor and accounts for 24% of choice in favor of a private school.

Discussion of results

As it was mentioned above, during school choice process, the key factor for the private schools’ students’ parents were as follows: good educational conditions; high quality education; safe environment and parents comfort (extra services including transportation, extra study etc.). As for the public schools’ students’ parents, during school choice process, the key factors were as follows: affordability; closeness to living area and good educational conditions. As we see, these results totally coincide with the world examples and theories discussed in literature review.

Now it’s interesting to compare the parents’ expectations and real results assessment.

Our results demonstrate that primarily, a private school parent pays for the safety and emotional wellbeing of a child, and a quality education takes only a third place. About half of the parents of private school students believe that their children get a high-quality education, which allows us to assume that the other half of parents are not entirely sure whether the chosen school, which they pay money to, gives a child an excellent quality education. The answer “school gives everything for a successful future” comes in fourth, and half of the private school parents think so (Tables 10, 11).

TABLE 10

| Better quality education | 48.4% |

| Small number of students at classes | 35.6% |

| Safer environment | 24.2% |

| Better relationship with students from teachers | 18.9% |

| Extra study | 10.8% |

Why are private schools better than public schools?

Own results.

TABLE 11

| No fee | 77.2% |

| Close to the living area | 19.4% |

Why are public schools better than private schools?

Own results.

According to the answers given by public school parents, there are far worse outcomes: The 2/3 of the parents of public-school students are not convinced that the school provides quality education, and 4/5 of parents do not believe that the school provides everything for a successful future.

Private school children’s parents are convinced that: a school can provide a safe environment—86.8%; their child feels good at school—82.0%; the school provides quality education—58.8%; the school gives everything for a successful future—53.6%. In the case of public schools, the sequence is as follows: A parent feels sure that: a child feels good at the school they choose—61.1%; the school can provide a safe environment—52.6%; the school provides quality education—31.8%; the school gives everything for a successful future—22.7%.

Despite such conflicting assessments, about half of both public and private school parents (43.4% of private school parents and 57% of public-school parents) believe that it is impossible to obtain a quality education without the help of tutors and family.

These results just partly coincide with the forth probability we made, to be more precise, overall neither private nor public schools totally satisfy the parents’ demands. Thus, here we come to Blake and Mestry (2021) opinion, discussed in literature review above, regarding the parents’ utopic expectations. If we consider the fact that the parents receive information mainly from their relatives or friends, it will be much interesting if the interviewed parents’ experience can have influence over the decision criterion and structure, of their relatives and friends in future. Thus, this can become the issue of additional research.

Both private and public-school parents try to compensate for the school’s shortcomings by arranging tutoring and home studying. The results of the study demonstrate that public school students are more likely to study with tutors than private school students. When it comes to the arts, sports, other extracurricular activities, more private school students are engaged in the activities than public school students.

The question is why parents pay (quite a lot) money to a private school if they are not sure about high-quality education. It is possible to conclude that this sequence of factors reflects the priority of the private school student’s parent—firstly safety, later emotional satisfaction, and only then quality education and the necessary conditions for future success and here we can compare and see similarity of our study results with Kisida and Wolf (2015).

Theoretically, it is possible that, among the various factors (described in detail in the central part of research results), presented to the respondents, we missed to include the criteria which would explain why parents still send their children to public schools even when there is nothing that prevents them?

In order to address this suspicion, the survey included two open questions, to which the respondents replied unlimitedly—1. Why are private schools better than public schools? 2. Why are public schools better than private schools? The answers were as follows:

It can be assumed that for most parents of public schools due to economic conditions, they cannot provide their children with private school education, and the choice of public school is a forced decision. To this end, the educational situation in Georgia somehow coincides with the Bosetti (2007) study explaining that—having alternatives and right to make choice is rather important.

Having considered the above, we can conclude that private and public-school parents have different attitudes toward school education, as well as parental beliefs about their child’s future success in school education. This totally coincides with the conclusions and examples by Hatcher (1998).

We can only assume that, since the data do not allow interpretation—it may be due to the different socioeconomic state of the families of private and public-school students (according to the survey). Income gives more choice to high-income families than low-income families—this is what the given findings/results reflect.

One of the limits of our study/research is that we don’t have enough material/evidence for finally strengthening this conclusion and that can become the issue of further/future research as well. Though the results discussed in previous paragraphs enables us to say that the school choice process is much linked with the parents’ education and income, and these results coincide with our third probability and with Robershaw et al. (2022) conclusions as well.

One more issue studied by us was a wish to change the school. The study asked: “Do you think you would take your child to another school if there were not any financial or other problems?” By this question, parents are hypothetically given a choice that they may not have. 89.6% of the parents of private school students would choose the same school, which is understandable. All survey data show that the parents of private school students are more-or-less satisfied with their school choices. In case of public school students’ parents’, the majority of them would like to move their kids to private schools (33%). To this end, our results coincide with Bosetti (2004) research results. Though we should also underline the parents who don’t support the idea to move their kids to other schools and they name 2 arguments for that:

- •

They think that “more or less all schools are the same,” thus school changing is pointless;

- •

In public schools the students gain serious social experience as they communicate with various types of people that can be a base for successful future.

As we see both arguments coincide with the ones named by the school choice theory opponents we discussed during literature review.

Concerning the information gathering, the study showed that during the school choice process, the private schools’ students’ parents are far more informed regarding various aspects of school, compared with the parents of the public school students. Thus, all these is conditioned by several requirements:

- •

In private sector there is a bigger choice and the parents are interested to gather as much information as possible to select the most appropriate and affordable variant for them. Thus, the parents of the private school students are more motivated about the information gathering and are also more involved in the school choice process than public school students’ parents;

- •

Because of superior social-cultural capital, the private school student’s parents have better access to useful information;

- •

The private school student’s parents pay certain amount of money and their attitude is much demanding toward the service they receive, including the information sharing. Thus this is the reason why the private school students’ parents are more informed compared with public school students’ parents.

All in all, our results have clearly shown that there is a difference between private and public school students’ parents. 75% of private school parents and 25% of public-school parents stated that they started thinking about to which school they would take the child when a child was 1-year-old. When parents started thinking about the school preference, the average age of a child was 1–2 for private school parents, and 3–4 for public school parents.

All these totally meet our expectations (see the probability 1 and 2) and the cases discussed in the literature review (see Smrekar and Goldring, 1999; Bosetti and Pyryt, 2007; Davies and Aurini, 2011).

Comparison of private and public-school students’ outcomes is a heavily debated topic among many researchers. Most of them show the unquestionable success of private schools compared to public schools. The study conducted by Coleman et al. (1982) also shows this advantage even when the socioeconomic status of the student is considered. The same results can be found in our study. The research results make it clear that the school choice much depends on the parents’ education and income. These results totally coincide with our third probability theory.

Furthermore, children’s gender also plays an essential role in school choice. The number of boys in both private and public schools exceeds the number of girls. In a private school, this difference is even more noticeable. In this respect our survey is echoing the findings of Bellani and Ortiz-Gersavi (2022).

One of the issues, that appeared in your research and was not the part of other international researches, was the number of kids in family and its influence on school choice process. Our study demonstrated a link between the number of children in the families (families with children under 18) and the parents’ choice—the more children in the family are, the more likely they are to go to public school. On average, families whose children attend a public school have more members. The families of public-school students consist of 4.58 members on average, and the families of private school students consist of 4.44 members on average. There are also, on average higher numbers of school-aged children—the ratio of children under 18 is 4.58 on average, and on average, 4.44 for private-school families. Thus, for sure this factor defines the family’s financial condition, and this coincides with the third our probability and abovementioned theories.

As we saw, the private school students’ parents’ are more likely engaged in schooling process. Private school parents are also encouraged by the schools themselves. As Chubb and Moe (1990) state, for private schools, a parent and a student are extremely central figures compared to public schools. Schools are more active in communicating with parents, as their successful communication is significantly related to their awareness, so a parent who is motivated to choose between the private schools is also helping private schools with their information policies. According to same authors a state school is a product of the state policy. State schools are controlled by a hierarchical system of state administration and democratic control. The policies adopted for the public schools are the result of the conflicting and reconciling interests of the various hierarchical branches of administration. Consequently, state schools offer a similar product to parents. Consequently, the need to obtain information about a particular public school in comparison to a private school is much less. Public school student’s parents try to fill the school gaps with private tuition and with the education the kids can receive from the family itself. This shows one more time that generally, the parents are much interested to provide perfect future for their kids, though socioeconomic conditions, environment, poor educational system limits their choice.

Once our results compared to the existing literature and theory, one can see that our study conducted in Georgia follows the trends of the developed countries, known as the “Heyneman-Loxley effect.”

Conclusion

As it was mentioned above for several times, the aim of the research was to study and describe the school choice process. The research focused on unveiling factors and their correlation during private and public schools’ choice process by the parents. Key issues of the research were as follows: (1) How interested the parents are to be actively involved in school choice process and spend certain period of time for that? (2) What factors are considered by the parents during school choice and what is the source they receive information from? (3) Does the family’s socioeconomic condition and the kids gender have influence on the process?

The study/research results are summed up in the following conclusion:

- •

The sharp segmentation of the society, where the people are divided having their own social circle, and attitude toward private/public/state education system;

- •

Education is very relevant for both groups of people and a serious issue of everyday discussion (talks about education issues with their friends/relatives on a daily basis). During the school choice process, the parents of the private school students are far more informed regarding various aspects of school, compared with the parents of the public school students; The parents of the private school students are more motivated about the information gathering;

- •

There are listed several factors defining the specific school choice:

- ∘

Different demands toward the service provided by the schools

- ∘

Parents’ socioeconomic condition

- ∘

Parents’ education

- ∘

Parents’ income

- ∘

Kids’ gender

- ∘

Number of kids in the family

- ∘

- •

During the school choice process, the key factor for the private schools’ students’ parents were as follows: good educational conditions; high quality education; safe environment and parents comfort (extra services including transportation, extra study etc.). As for the public schools’ students’ parents, during school choice process, the key factors were as follows: affordability; closeness to living area and good educational conditions. As we see, these results totally coincide with the world examples and theories discussed in literature review;

- •

It can be assumed that for most parents of public schools due to economic conditions, they cannot provide their children with private school education, and the choice of public school is a forced decision;

- •

The private school students’ parents are more confident in their choice (that they chose the right school for their kids) than the public school students’ parents;

- •

Our results demonstrate that primarily, a private school parent pays for the safety and emotional wellbeing of a child. In the case of public schools’ parents feel sure that: a child feels good at the school they choose and the school can provide a safe environment. The data show that the following answer—“provides quality education” is much important for both public and private schools’ students’ parents and in the list of trust is ranked on the third place;

- •

The parents of the private schools’ students’ are more confident and think that there is enough choice of schools in Georgia than the parents of the public schools’ kids’. But about half of both public and private schools’ students’ parents believe that it is impossible to obtain a quality education without the help of private tuition and family.

It’s worth mentioning that, generally the research results fully coincide with the school choice theory arguments and the research findings conducted in the similar field. All these are described and presented in the first part of the article. The probabilities listed on the base of the current data, that the information source, the parent’s information level, the parents’ engagement as well as the family’s socioeconomic and demographic status play integral role in the school choice process appeared to be genuine. Apparently, the parents are much interested to provide perfect future for their kids, though socioeconomic conditions, environment, poor educational system limits their choice.

Once our results compared to the existing literature and theory, one can see that our study conducted in Georgia follows the trends of the developed countries, known as the “Heyneman-Loxley effect.”

Statements

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (Ethics Committee) of Ilia State University Tbilisi, Georgia, protocol code ECISU 0l0gl20r7. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

AT carried survey. AT, LT, and WS analyzed the survey results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^John Stuart Mill, 1859, On Liberty.

2.^According to author educational pluralism charts a middle course, between libertarian approach and status quo, that offers an expansion of educational options within a common accountability framework.

3.^The Education Reform Act 1988 (and subsequent case law) gave all families the right to express a preference for any school (even one outside their Local Education Authority) and denied schools the right to refuse anyone entry until a planned admission number was reached.

4.^CHAT is a cross-disciplinary framework for studying how humans purposefully transform natural and social reality, including themselves, as an ongoing culturally and historically situated, materially and socially mediated process (Roth et al., 2012).

5.^Russian Federation - History Background - Education, Schools, Educational, and School - StateUniversity.comhttps://education.stateuniversity.com/pages/1265/Russian-Federation-HISTORY-BACKGROUND. html#ixzz6swsAsSYb.

7.^National Assessment and Examinations Center official website https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/timss2015/international-results/wp-conten t/uploads/filebase/full%20pdfs/T15-International-Results-in-Mathematics.pdf.

8.^10 detailed interviews were conducted with the field experts beforehand. During the interviews current situation in Georgia was discussed, as well as problems and issues for research. Later the draft of used questionnaire was also discussed with them.

9.^We studied following researches: Caucasian Barometer 2010–2016 (www.caucasusbarometer.org); The General Education Voucher Funding Effectivity Research in the Context of Equality, 2014; The research was conducted by Centre for Civil Integration and Inter-Ethnic Relations (CCIIR) in the frames of the East West Management Institute (EWMI) Policy, Advocacy, and Civil Society Development in Georgia project (G-PAC), funded by USAID. The costs spent on general education and its results, 2013–2016; Private Schools Research in Georgia, 2018; Besides this 70 private school teachers and 70 public school teachers were interviewed.

10.^For instance: Parents motivation when they have different approach while making school choice in case of sons and daughters; Private school choice motivation, when they still have to pay money for extra tuition etc.

References

1

AllisonD. J. (2015). School choice in Canada: Diversity along the wild–domesticated continuum.J. Sch. Choice9282–309. 10.1080/15582159.2015.1029412

2

BakerD. P.GoeslingB.LeTendreG. K. (2002). Socioeconomic status, school quality, and national economic development: A cross-national analysis of the “heyneman–loxley effect” on mathematics and science achievement.Corp. Educ. Rev.46291–312. 10.1086/341159

3