- 1Broward County Public School District, Fort Lauderdale, FL, United States

- 2Department of Counselor Education, School of Psychology, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 3School of Nursing, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA, United States

- 4Department of Counseling, School of Psychology, Alfred University, Alfred, NY, United States

This study was an investigation of the possible relations and interactions between traditional feminine ideology, and social and relational aggression within a sample of female children and adolescents. Participants included 45 female students (8-19 years of age) who completed measures assessing beliefs about and behaviors feminine ideology, body image (including body objectification), relational and social aggression, and interpersonal maturity. Analyzes revealed that participants who rated themselves as having a weaker internalization of the objectification of one’s body (a subtype of traditional feminine ideology) rated themselves as less likely to use socially-aggressive tactics than those with higher levels of body objectification. No other significant findings were noted. Implications for these findings and directions for future research are discussed.

Feminine Ideology, Body Appreciation, and Indirect Aggression in Girls

Direct forms of physical and verbal aggression are observable, easily detected by adults, and often result in immediate intervention. However, indirect aggression tends to be more subtle, thereby making it difficult for adults to detect. Factor analytic studies have distinguished between direct aggressive behavior and what is broadly termed indirect aggression, which includes manipulation of relationships to inflict harm, such as sabotaging friendships or romantic relationships, and damaging a victim’s social standing, through such behaviors as gossiping and excluding someone from activities, frequently through indirect or covert methods (Card et al., 2008). Girls tend to use indirect means of aggression more frequently than boys, although meta-analyzes have suggested that these differences favor girls only slightly (Card et al., 2008), and are revealed through some means of assessment (e.g., observations, peer ratings, teacher reports) but not others (e.g., peer nominations, self-reports; Archer, 2004).

Girls’ Use of Indirect Aggression

Gender role theory has been suggested as an explanation as to why girls appear to be more likely to use indirect aggression. Gender role theorists suggest that children are socialized to associate masculinity with achievement and autonomy, while femininity is characterized by affiliation, nurturance, and passivity (Bem, 1981). Thus, girls who identify with traditional feminine gender identity avoid overt conflict in order to maintain harmonious relationships, but resort to covert means to expressing anger and resolving conflicts in comparison to females who are less traditionally feminine in their sex role type.

Young girls learn that it is not acceptable, as purported by traditional gender norms, to use more overtly-aggressive techniques when in conflict with a female friend, as their male peers may (Pressley and McCormick, 2007). In simpler terms, physical aggression is not viewed by society as “feminine” behavior, and this is ingrained within the female adolescent population from a young age. In contrast, adolescent girls may come to realize that by utilizing relationally- and socially-aggressive tactics, they can control or manipulate the friend group in a way that is viewed as more acceptable by society.

A number of of other hypotheses have been presented regarding girls’ increased use of indirect aggression in comparison to boys’. First, some have posited that females’ less-developed physical strength necessitates girls’ reliance on indirect means of aggression more so than that demonstrated by boys (Björkqvist et al., 1991). Second, girls’ more-rapidly-developing verbal and social skills that are not required for direct forms of aggression are ideally suited to indirect forms of aggression (Björkqvist et al., 1991). Third, girls heavily rely on the emotional and social support derived from a social group and friendships in adolescence in comparison to boys’ more numerous, casual relationships (Maccoby, 1990, 1998; Björkqvist et al., 1991), rendering them vulnerable to attacks about their relationships. Fourth, the sexual reputation of girls are likely to be scrutinized (e.g., gossip about promiscuity and sexual identity) as well as their general social reputations (Artz, 2005). Finally, gender socialization processes that occur through role modeling, reinforcement, and punishment (Pressley and McCormick, 2007) reward gender-typical behaviors and punish gender-atypical behaviors (Galambos, 2004).

Gender Socialization and Education

There is research to suggest that the educational process reinforces gender stereotypes and inequalities, as youth are exposed to gender stereotypes which serve as the foundation for gender roles (Gooden and Gooden, 2001). Feminist research studies have revealed that although schools espouse the value of educational equality, schools often include gender stereotypes that constitutes a hidden curriculum (Skelton, 1997). According to UNESCO, common prejudicial attitudes toward females reflected in school textbooks include the fact that in comparison to males females are mentioned less frequently and are less likely be represented within images and roles in which they are depicted are less varied (Michel, 1986).

Gender-Typical Aggression for Girls

Related to the final hypothesis, adolescent girls may be reprimanded for using overt forms of aggression, since physical aggression is not viewed as “feminine” behavior (Bowie, 2007). As a result, adolescent girls likely internalize such gender boundaries in handling conflict and search for other means by which to solve problems with peers (Field et al., 2006), which often leads them toward indirect aggression. Furthermore, girls are known to spend an increasing amount of time with their same-sex peers throughout adolescence; therefore, it is essential to understand how a social group can create an appearance culture in which the girls share similar expectations (Paxton et al., 1999). Since girls place such importance on maintaining their close friendships, they may be willing to conform to the group norms in an effort to enjoy the social benefits and preserve their standing within the group even when the group’s expectations regarding body image may lead to greater body dissatisfaction in individual members (Oliver and Thelen, 1996).

Feminine Ideology and Indirect Aggression

The purpose of this study is to determine if girls’ identification with more traditional feminine characteristics is a risk factor for relational aggression, and if the converse is also true, if body appreciation among girls is a protective factor against the perpetration of relational aggression. There is considerable literature regarding gender identity and, more recently investigations have examined feminine ideology, which concerns people’s perceptions of how women are expected to act in society. For the purposes of this study, feminine ideology is to be understood as a socially-constructed ideology in which the current culture reinforces several ways in which a girl must behave in order to be viewed as “feminine” (Tolman et al., 2006). More specifically, the feminine ideology posits that girls must behave in a “feminine” manner within their relationships with others, and their bodies are to be objectified and kept within the standards espoused by society (Tolman et al., 2006).

The limited literature regarding identification with traditional feminine norms and indirect aggression is mixed. Several studies that have used the Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem, 1981), which measures people’s identification with traditional gender norms, revealed that there was a positive association between feminine gender identity and indirect aggression with high school girls (Crothers et al., 2005), but no such relationship was identified for college students (Kolbert et al., 2010). Dickinson (2007), who used the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory (Parent and Moradi, 2011), found a negative relationship between conformity to feminine norms and indirect aggression among college females. Given the lack of clarity in the research literature regarding the relationship between identification with traditional feminine gender norms and indirect aggression, we sought to examine such a potential relationship using the Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale (AFIS; Tolman et al., 2006). The BSRI (Bem, 1981),which was used in the previously mentioned studies, measures gender-typed personality traits. The AFIS measures the degree to which girls have internalized two aspects of traditional feminine ideology: inauthenticity and body objectification.

Traditional feminine ideology, which is a specific form of gender ideology, concerns people’s internalization of the dominant cultural beliefs regarding expected roles for girls and women (Pleck, 1995). Traditional feminine ideology has been linked to poor mental health outcomes for girls and women (Tolman et al., 2006; Richmond et al., 2015). According to the theory of traditional femininity ideology, regardless of whether females identify or do not identify with traditional feminine norms, they will likely experience stress and conflict due to social pressures to follow expected feminine expectations (Levant, 2011). The fact that the BSRI and AFSI measures different constructs is supported by the finding that neither of the two subscales of the AFIS were related to the BSRI (Tolman and Porche, 2000).

Body Appreciation and Indirect Aggression

Whereas we expect that traditional feminine ideology may be related to use of indirect aggression, which has been hypothesized to be a more acceptable form of aggression for girls and women who hold a traditional view of femininity, we will also examine if body appreciation, which may be considered a characteristic that is inconsistent with traditional feminine ideology, is negatively related to use of indirect aggression. Body appreciation concerns having a positive view of one’s body, which contrasts with the construct of body image which concerns negative thoughts and feelings about one’s body (Avalos et al., 2005).

Western cultures emphasize one’s physical appearance as an indication of one’s value, and the body has become an essential element of gender identity. The human form is evaluated according to a gendered standard of beauty (e.g., Calogero and Tylka, 2010). Objectification theory (Frederickson and Roberts, 1997) asserts that female bodies in particular are sexually objectified. In modern society female beauty is equated with extreme thinness and large breasts (Hesse-Biber et al., 2006), allowing little space for a diverse range of body types (Calogero and Tylka, 2010). These ideals of that feminine beauty are associated with thinness and fragility are internalized at early ages (Harriger et al., 2010). It has been well established that women tend to be concerned about their physical appearance (Etcoff et al., 2004). Women analyze their bodies and exhibit greater levels of shame and anxiety about their bodies in comparison to men (Slater and Tiggerman, 2010). Women are also more likely than men to discuss their bodies with others (Jones and Crawford, 2006). Body objectification among women is negatively associated with psychological wellbeing (Tolman et al., 2016), which solidifies the idea that body image is an essential component of the feminine ideology.

Among female college students traditional feminine ideology has been found to be negatively associated with appreciation of one’s body (Swami and Abbasnejad, 2010).

Tolman et al. (2006) revealed that many adolescent girls exhibit body objectification, which involves viewing one’s body as an object disconnected from one’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and whose purpose is to satisfy the sexual gratification of others (Frederickson and Roberts, 1997).

There is scant research regarding a potential relationship between girls’ thoughts about their body and indirection aggression. Reulbach et al. (2013), the only related study that could be identified in the literature, revealed that among both 9 year-old boys and girls, body image, but not body mass index, was associated with both bullying perpetration and bullying victimization.

Based upon the findings discussed, and the need for further investigation in the areas of feminine ideology, body appreciation, and indirect aggression in girls, we proposed the following research questions:

Our research questions are as follows:

• Do the beliefs consistent with a traditional feminine ideology impact adolescent girls’ use of social and relational aggression?

• Does body appreciation impact adolescent girls’ use of social and relational aggression? (3) Are adolescent girls’ levels of interpersonal maturity impacted by such constructs as the beliefs consistent with traditional feminine ideology or body appreciation?, and4) Does body appreciation moderate the relationship between traditional feminine ideology and social and relational aggression in adolescent girls?

Materials and Methods

Participants

The population for this study included female students ranging in age from 8 to 19 years who attended independent or faith-based private k-12 schools in the mid-Atlantic U.S. Students at these schools and their parents were provided with information about the study, and the students were invited to participate in the research. The final sample of participants included 45 female students from an overall sample of 116 students. Almost 76% of the sample identified as White, 17.8% as Black, 2.2% as Biracial, 2.2%, Asian/Pacific Islander, and 2.2% endorsed “Other.” Protocols were excluded from the analysis if they were completed by a male student, or if the protocol was incomplete.

Measures

The Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale

Data obtained from the Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale (AFIS; Tolman and Porche, 2000) was examined to understand how adolescent girls relate to the feminine ideology. The AFIS was developed to evaluate the extent to which adolescent girls internalize two significant aspects of femininity). This measure includes 20 items within two subscales to examine how adolescent girls feel about themselves. Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale in which 1 denotes that a girl Strongly Disagrees and 6 indicates that a girl Strongly Agrees. The AFIS consists of two subscales that are to be scored separately, and allows the researcher to examine two key aspects of femininity. After reverse-scoring several of the items, the scores on the two subscales are then averaged separately in order to examine these subsets of femininity. Higher scores on these subscales indicate a stronger internalization of the feminine ideology, while lower scores point toward weaker internalization of femininity.

The Inauthentic Self in Relationship Subscale (ISR)

In this subscale, an individual’s ability to be authentic in the expression of her thoughts and feelings toward another within a close relationship are measured. Several items on the ISR subscale include, “I worry that I make others feel bad if I am successful,” “Often I look happy on the outside in order to please others, even if I don’t feel happy on the inside,” “I usually tell my friends when they hurt my feelings,” and “I express my opinions only if I can think of a nice way of doing it.”

The Objectified Relationship to Body Subscale (ORB)

In the second subscale, items illustrate how a girl may evaluate, rather than appreciate, her own body. Items evaluated on the ORB subscale include, “I often wish my body were different,” “I think a girl has to have a light complexion and delicate features to be thought of as beautiful,” “I often feel uncomfortable in my body,” and “I am more concerned about how my body looks than how my body feels.”

The AFIS has been shown to exhibit acceptable reliability as evidenced by the internal consistency of the measure (Tolman and Porche, 2000). The ISR subscale had Cronbach’s alpha score of α = 0.81 for a first-year college sample Similarly, the ORB subscale yielded Cronbach’s alpha score of α = 0.81 for a first-year college site. The validity of the AFIS has been established through convergent validity studies between the IRF subscale and responses on the Appearance Evaluation subscale of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (Tolman and Porche, 2000) in an eighth-grade sample (r = -0.65, p < 0.001), and between the ORB subscale and the Body Image subscale of the Self-Image Questionnaire for Young Adolescents for both the eighth-grade (r = -0.51, p < 0.001) and high school (r = -0.75, p < 0.001) populations (Tolman and Porche, 2000). The AFIS has been shown to have acceptable predictive validity, as high scores on both the IRS and ORB subscales have been linked to low self-esteem and depression. Lastly, research has shown the AFIS to be a unique measure in that it evaluates feminine ideology separate from previously conceived ideas of the construct, such as a personality trait or gender role (Tolman and Porche, 2000).

The Body Appreciation Scale (BAS)

The BAS utilizes 13 items to examine an individual’s favorable opinions of the body, acceptance of the body regardless of weight, body shape, and imperfections, respect for the body by engaging in self-care behaviors, and protection of the body by resisting unrealistic body images (Avalos et al., 2005). BAS items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from Never (1) to Always (5). The scores are averaged to provide a global measure of body appreciation, with higher scores reflecting greater body appreciation. A sample of items included on the BAS are, “I respect my body,” “Despite its flaws, I accept my body for what it is,” “I am attentive to my body’s needs,” and “I engage in healthy behaviors to take care of my body.”

Avalos et al. (2005) showed that the BAS has good reliability by examining both the internal consistency and test-retest reliability of the measure. Cronbach’s alpha was used to examine internal consistency, with a resulting value of 0.94. The corrected item-total correlations had an average of 0.73, and ranged from 0.41 to 0.88, indicating appropriate internal consistency. In terms of test-retest reliability, BAS scores are consistent over a 3-week period as demonstrated by an overall correlation (r = 0.90, p < 0.001).

The BAS has acceptable convergent validity as Avalos et al. (2005) demonstrated by examining its associations to similar measures. A large effect size was observed in regards to BAS scores and body esteem, as high BAS scores were clearly related to higher body esteem (r = 0.50, p < 0.001) and physical condition (r = 0.60, p < 0.001). Additionally, high scores on the BAS were associated with lower weight concern (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), lower body surveillance (r = -0.55, p < 0.001), and lower body shame (r = -0.73, p < 0.001). Additional evidence for the BAS’s convergent validity is provided in that higher BAS scores are linked with a greater tendency to evaluate one’s appearance favorably (r = 0.68, p < 0.001), a decreased likelihood to engage in body preoccupation (r = -0.79, p < 0.001), and a decreased likelihood to feel dissatisfied with one’s body (r = -0.73, p < 0.001).

The BAS also has strong associations to self-esteem (r = 0.53, p < 0.001), optimism (r = 0.50, p < 0.001), and proactive coping (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), providing evidence for its association with psychological wellbeing (Avalos et al., 2005). The BAS proves to have a strong, negative correlation with eating disorder symptomatology (r = -0.60, p < 0.001), further providing evidence that high scores on the BAS illustrates positive body image (Avalos et al., 2005). Discriminant validity is presented as BAS scores were only slightly related to impression management (r = 0.14, p < 0.01; Avalos et al., 2005).

The Young Adult Social Behavior Scale

The Young Adult Social Behavior Scale (YASB) is a measure that was used to evaluate indirect bullying (relationally- and socially-aggressive behaviors) as well as behaviors that reflect social maturity (Crothers et al., 2009). The instrument is a 14-item self-report measure that aims to assess both healthy and maladaptive behaviors that individuals use within friendships or relationships. The YASB was developed with the purpose of examining both relational and social aggression, as well as indicators of interpersonal maturity, in adolescents and young adults. Raters evaluate themselves utilizing a 5-point Likert scale including such responses from Always (1) to Never (5). On the YASB, lower scores reflect higher use of relational aggression, social aggression, and interpersonal maturity. Several items included on the YASB are as follows, “When I am angry with someone, that person is often the last person to know. I will talk to others first,” “I contribute to the rumor mill at school or with my friends and family,” “I confront people in public to achieve maximum damage,” and “I respect my friend’s opinions, even when they are quite different from my own.”

Although some researchers have argued that relational and social aggression are similar constructs, the YASB includes items meant to tap both relationally and socially aggressive behaviors separately from one another (Crothers et al., 2009). The definitions used for these two terms for the purposes of the YASB differ in that relational aggression includes influencing a person within the context of a dyadic relationship, while social aggression includes intending to harm an individual’s social standing within a peer group. These definitions differ in the intention of the aggressor, and thus the items on the YASB reflect this important difference.

In order to further assess how relational and social aggression are separate constructs, Crothers et al. (2009) conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to test three separate theoretical models of the YASB. Model A, which depicted three separate factors including social aggression, relational aggression, and interpersonal maturity, was the best fit of the three proposed models. The Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) was utilized to assess the best fitting model, with lower values representing a good fit. The AIC was 164.39 for Model A, 178.78 for Model B, and 268.96 for Model C, providing support that Model A was the best fitting model in the CFA. The comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.98, the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) was 0.97, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.02. As values for CFI and TLI of more than 0.95 suggest a good fitting model, and RMSEA values less than 0.05 indicate a close fit, these results further support that Model A was superior and that the three constructs are separate from one another.

In order to demonstrate convergent and divergent validity of the YASB, ratings on the scale were compared to a measure of hyperfemininity (Crothers et al., 2009). Correlations showed that those with lower scores on relational and social aggression behaviors (which indicates higher usage of these behaviors), scored higher on levels of hyperfemininity. Furthermore, the YASB appears to be a reliable measure as the internal consistency of each factor is reported as exceeding 0.70 (Kolbert et al., 2012).

Overall, research indicates that relational and social aggression are related, yet separate constructs (Crothers et al., 2009). Furthermore, CFA proved that the best fitting model was one that differentiated among the constructs of relational aggression, social aggression, and interpersonal maturity, indicating that this measure can appropriately distinguish between two types of aggression that were considered to be synonymous with each other in different theoretical models (Crothers et al., 2009).

Results

Prior to the primary statistical analyzes, several steps were taken to screen the data and examine statistical assumptions. In order to determine if there were any outliers, histograms and frequency charts were examined; no cases were removed from the analysis due to extreme values being obtained. The assumption of normality did not appear violated on the measure used to capture the dependent variables as indicated by an analysis of the skewness and kurtosis as well as a non-significant result on the Shapiro-Wilk test (p = 0.28). The linearity and homoscedasticity assumptions were visually scrutinized for potential problems. Field (2013) states that these assumptions can be analyzed together via scatterplots in which the values of the residuals are plotted against the predicted values of the model; the scatterplots exhibited no systematic relationships; therefore, these assumptions were met. Lastly, multicollinearity of the predictor variables was evaluated through an examination of a correlation matrix. None of the variables appeared to highly correlate with one another, as defined by all correlations falling below 0.80 (Field, 2013).

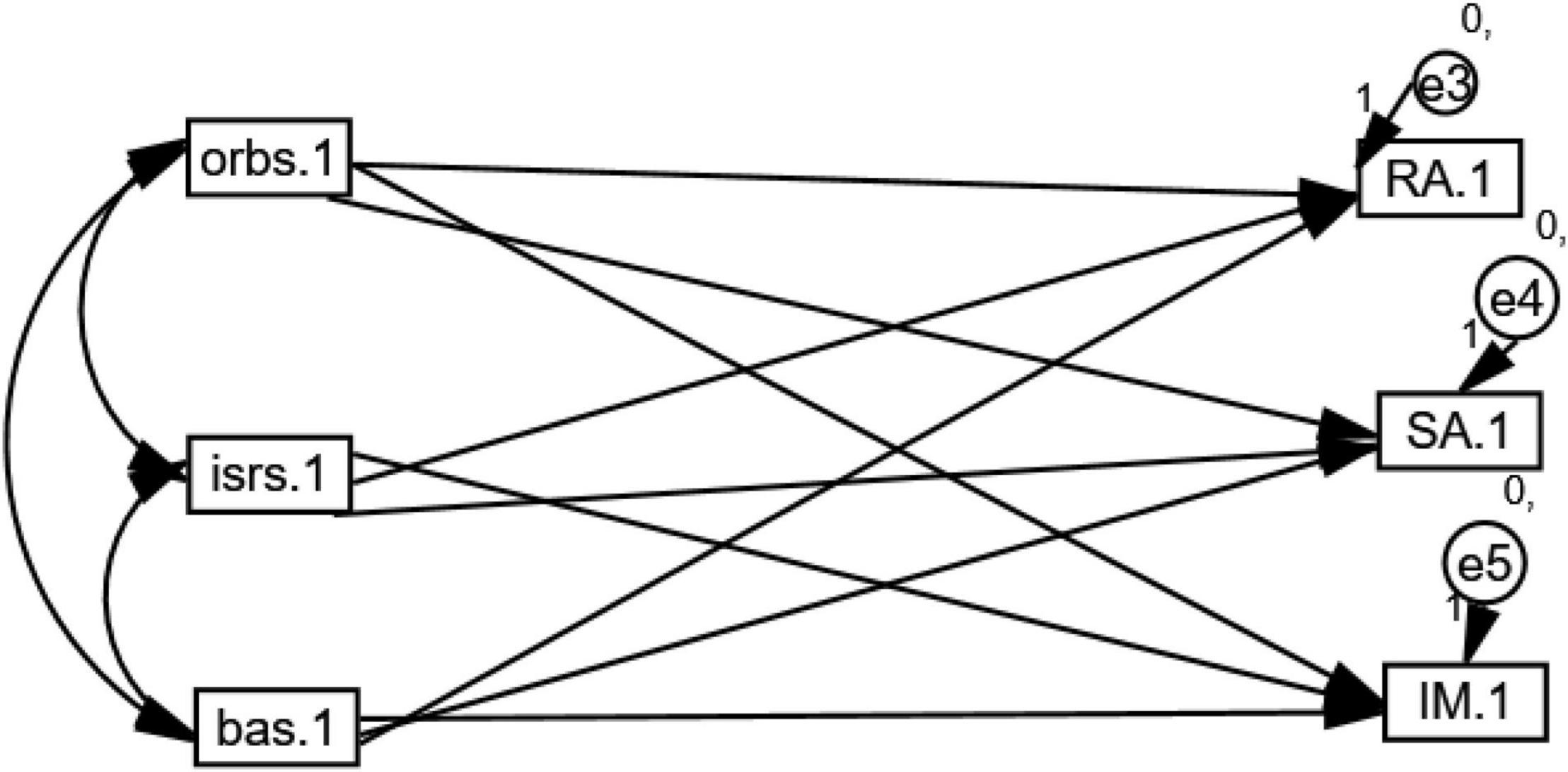

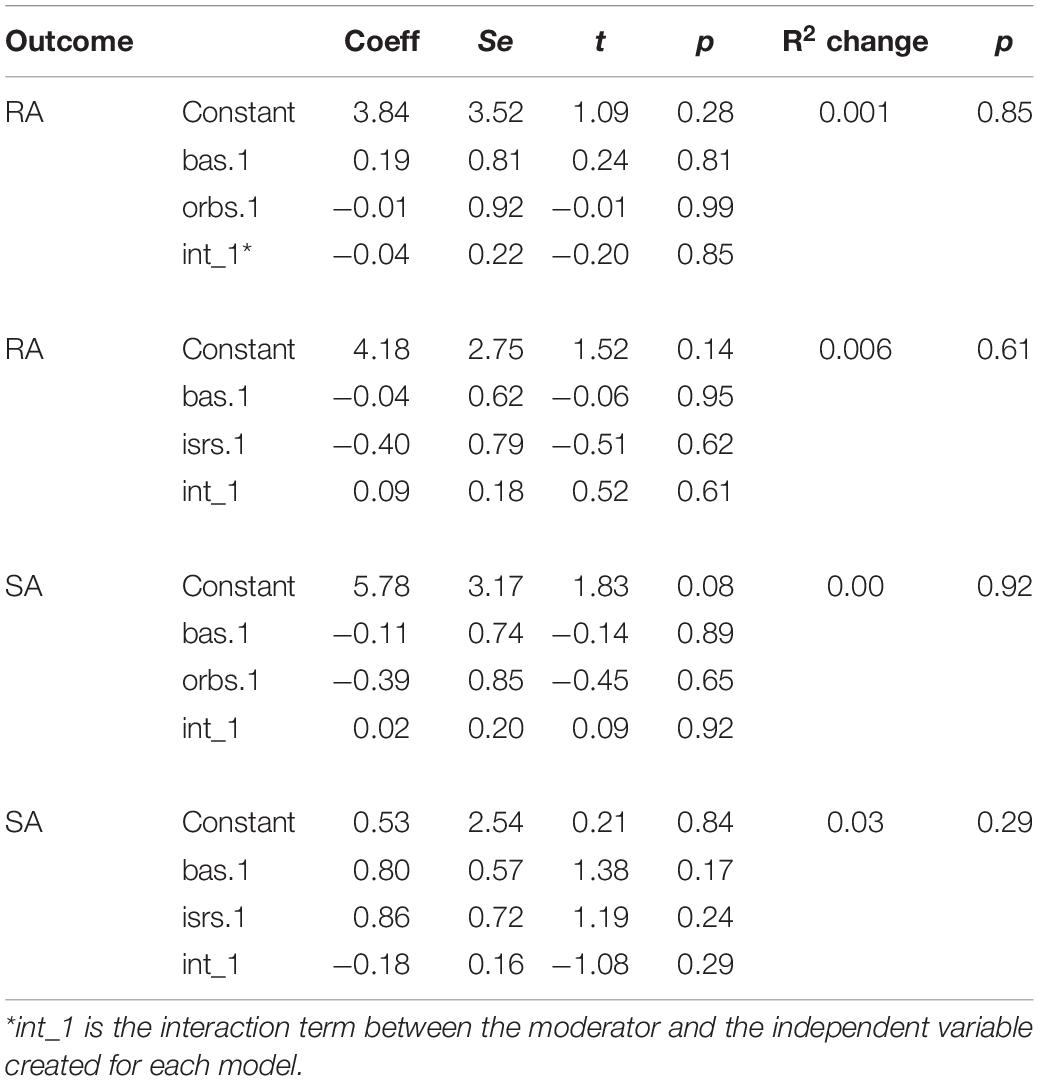

Research questions one, two, and three were evaluated with structural equation modeling (SEM). Several indices were examined to assess the overall fit of the hypothesized model: the chi-square (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the chi-square adjusted by its degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). A good-fitting model would have a χ2 that is insignificant (p > 0.05), CFI ≥ 0.95, TLI ≥ 0.95, CMIN/DF < 3.00, and RMSEA ≤ 0.08 (Hooper et al., 2008; Iacobucci, 2010). It should be noted that the chi-square statistic is sensitive to sample size; therefore, the CMIN/DF has been recommended as a more appropriate indicator of model fit (Iacobucci, 2010). Given that this study is based on a small sample size, the chi-square statistic should be interpreted with caution. A diagram of the researcher’s proposed model is depicted in Figure 1. The fit indices for the model are displayed in Table 1, and indicate a poor fit. This suggests that the data collected from this particular sample of adolescents do not appropriately fit the hypothesized model.

Table 1. Estimates from structural equation modeling (SEM) model for research questions 1, 2, and 3.

In research question one, we investigated the link between the internalization of feminine ideology and adolescent girls’ use of social and relational aggression. The two subscales on the AFIS, the ORB (objectified relationship with body) subscale and the ISR (inauthentic self in relationships) subscale, were utilized as predictors, and two constructs on the YASB, relational aggression (RA) and social aggression (SA), were examined as outcome variables. Therefore, the paths from orbs.1 and isrs.1 to RA.1 and SA.1 were analyzed in answering this question. The statistical estimate, or regression coefficients, for these paths may be viewed within Table 1. A significant path was found from orbs.1 to SA.1 (β = -0.47, p < 0.01). Participants who reported lower ratings on the ORB subscale of the AFIS tended to rate themselves higher on YASB items relating to social aggression. Lower scores on the two subscales within the AFIS indicate lower levels of feminine ideology while higher scores on the YASB items indicates lower rates of aggression; therefore, these results reveal that those who rated themselves as having less internalization of feminine ideology tended to report engaging in fewer acts of social aggression. In contrast, significant paths could not be derived between the ISR subscale of the AFIS and either social or relational aggression as indicated on the YASB. Although these findings partially support the hypothesis in that subjects who rated themselves as more gender atypical on the ORB subscale of the AFIS also indicated more infrequent utilization of social aggression, it should be noted that this was found within a poor-fitting model.

In research question two, we investigated if body appreciation impacted adolescent girls’ use of social and relational aggression. Responses from the BAS were employed as predictors, while RA and SA scores were again scrutinized as outcome variables. The BAS provides a global indicator of body appreciation, with higher scores indicating higher levels of body appreciation and lower scores indicating reduced appreciation for the body. Paths leading from bas.1 to RA.1 and SA.1 were examined (Table 1) to gain greater insight as to research question two. Neither the path from bas.1 to RA.1 nor the path from bas.1 to SA.1 was found to be statistically significant. The statistical analyzes performed in relation to body appreciation and indirect aggression did not support this hypothesis.

In research question three, we investigated whether adolescent girls’ levels of interpersonal maturity are impacted by such constructs as the internalization of feminine ideology or body appreciation. For this question, ratings collected on the ORB subscale, the ISR subscale, and the BAS were used as predictors, and a third construct from the YASB, interpersonal maturity (IM), was assessed as the outcome variable. The paths from orbs.1, isrs.1, and bas.1 to IM.1 were evaluated in answering this question (see Table 1). The analyzes found that none of these paths held statistical significance. It should be noted that the paths from orbs.1 and bas.1 to IM.1 were negative, signifying that those who rated themselves lower on the ORB subscale and the BAS scale rated themselves higher on the interpersonal maturity items of the YASB. The pattern of ratings collected indicated that those reporting themselves as having lower levels of appreciation for their bodies also rated themselves as exhibiting lower levels of interpersonal maturity.

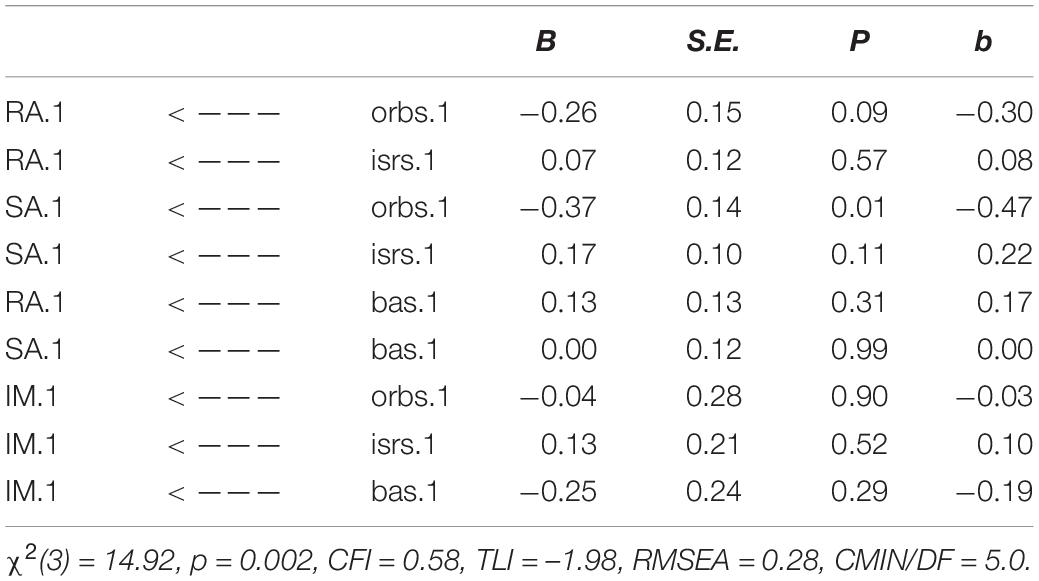

In research question four, we explored if body appreciation moderates the relationship between feminine ideology and social and relational aggression in adolescent girls. Put simply, moderation is an interaction effect, whereby two variables work together to produce an effect on an outcome variable (Field, 2013). A variable is considered to moderate the relationship if it impacts the strength or the form of the relationship between a predictor and an outcome variable (MacKinnon, 2011). Social and relational aggression served as the dependent variables for this research question, feminine ideology was considered the independent variable, and body appreciation was the moderator variable. The independent, dependent, and moderator variables were all entered into the model. Four separate models were required in order to provide the most information relating to the relationships between the variables. The four models included one for each indirect aggression style, both relational aggression and social aggression, modeled on two subtypes of feminine ideology, the inauthentic self in relationships subscale and the objectified relationship with the body subscale. Moderation has occurred if the model produces a significant interaction term and a significant change variance accounted for.

The estimates from the differing moderation models are presented in Table 2. In most models, the interaction terms are the opposite direction of the moderator and independent variables. The moderation analysis did not find any significant interactions, nor were there any significant changes in variance. These analyzes reveal that body appreciation does not act as a moderator between feminine ideology and indirect aggression within this specific sample of adolescent girls.

Additional Analyses

Additional regression analyzes Were completed as an attempt to see if the large age range of the participants contributed to any changes Within the relational aggression, social aggression, or interpersonal maturity scores. in order to evaluate the impact of age on these three outcome variables, linear regression analyzes Were conducted using age as the predictor variable. the participants’ age did Not appear to Have a statistically significant impact on the change in relational aggression scores, R2 = 0.12, R2adj = 0.08, F(1, 24) = 3.10, p = 0.09. However, age proved to significantly impact changes in scores relating to social aggression, R2 = 0.15, R2adj = 0.12, F(1, 24) = 4.33, p = 0.05. the effect size Was 0.39, indicating a moderate effect. as With relational aggression, age did Not serve as a statistically significant predictor of changes in scores on the interpersonal maturity items, R2 = 0.06, R2adj = 0.02, F(1, 25) = 1.63, p = 0.21.

Lastly, multiple regression analyzes were conducted including the predictor of age along with the items relating to feminine ideology and body appreciation. The three constructs captured through the responses on the YASB served as the outcome variables for this series of regressions. Regression results examining the variables of age, feminine ideology (isrs and orbs), and body appreciation (bas) as predictors did not significantly predict the change in relational aggression scores, R2 = 0.13, R2adj = -0.05, F(4, 20) = 0.71, p = 0.59. Likewise, the results utilizing these same predictors upon the changes in social aggression did not yield statistically significant findings, R2 = 0.27, R2adj = 0.13, F(4, 20) = 1.86, p = 0.16. Lastly, a multiple regression examining the impact of these predictors on interpersonal maturity did not find statistically significant implications, R2 = 0.13, R2adj = -0.03, F(4, 21) = 0.81, p = 0.53. These additional analyzes indicate that the inclusion of age within the three regression models did not assist in the discovery of statistically significant findings.

Discussion

The results appeared to provide partial support for the hypothesis that girls’ gender identity is related to their use of indirect aggression. We found that girls who reported less body objectification were less likely to report engaging in social aggression, although such a relationship was not found for relational aggression. Interestingly, we did not find that body appreciation, which can be considered the opposite construct of body objectification, to be related to girls’ use of social and relational aggression. We also did not find that interpersonal maturity was related to either body objectification or body appreciation.

The fact that girls who reported less body objectification were less likely to engage in social aggression may reflect such girls’ developing understanding of the negative impact of traditional social expectations of women and its particular relevancy within social contexts. The intent of social aggression is to negatively impact the social status of a peer, whereas in relational aggression, the intent is to obtain power within a relationship dyad through the use of relationships threats. Crothers et al. (2009) found that social and relational aggression are related but distinct constructs. It is possible that girls who are developing an understanding, and resisting, the objectification of their bodies by others have a greater understanding of social context and the inappropriateness of harming others within social contexts.

The fact that relational aggression was not associated with traditional feminine gender identity may be related to the age of the participants who ranged from nine to 19 years of age. It is possible that girls who earlier develop a social consciousness, who begin to recognize and reject society’s objectification of females and social pressure to pursue social status through the use of social aggression, are in the nascent phases of developing the skills necessary for managing relationship conflict in a mature manner. The age of participants may also be an explanation as to why body appreciation was not found to be associated with social or relational aggression or interpersonal maturity, as girls who are learning to resist body objectification are still developing the capacity for body appreciation.

An implication of the findings is that programs that seek to reduce aggression among youth should promote girls’ understanding of how they have been influenced by societal characterizations of traditional femininity. Girls can be helped to understand that the characterizations of femininity as involving affiliation, nurturance, and passivity, presents an incomplete portrayal, that it is acceptable for females to desire power and influence, and that conflict is inevitable within all relationships. Girls can be assisted in understanding the larger social context that influences how they view their bodies and relate to their peers. In contrast, girls who have begun to counter the limiting societal perspectives that equate females’ worth with their physical appearance may need less assistance in understanding the negative impact of social aggression, and may need more assistance with managing conflict within a relationship dyad.

Limitations and Future Directions

The presented results and findings should be evaluated in light of the study’s limitations. Perhaps the greatest limitation of this study was its low statistical power due to the small sample size. Several cautions should also be noted in regards to group composition and selection threats. The sample utilized in this study was homogeneous in that all students attended independent or faith-based educational settings. In contrast, the participants within this study were quite heterogeneous in that they notably ranged in age. Additionally, selection threat may have hindered the researcher from seeing greater results, as parents of more aggressive adolescents may not have provided consent for their child to participate in the study.

The results of the study suggest that further research regarding the potential relationship between traditional feminine ideology and social and relational aggression is warranted. Future studies should differentiate between social and relational aggression, as such efforts may provide a rationale for differentiated interventions for youth aggression. Longitudinal investigation is needed to confirm a causal relationship between girls’ resistance to body objectification and decreased use of social aggression.

Conclusion

This results of this study provide partial support for gender role theory in that girls who displayed less body objectification, which is one the main components of traditional feminine ideology, were less likely to engage in social aggression, which has been theorized to be a form of aggression that is seen by as more acceptable to females who maintain a traditional view of women. Additional investigation regarding traditional feminine ideology and social and relational aggression appears to be warranted, and future investigations should differentiate between social and relational aggression. The results suggest that intervention efforts should promote girls’ understanding of how societal messages of femininity may influence their views of their bodies and how they relate to their peers.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Duquesne University Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: a meta-analytic review. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 8, 291–322. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291

Artz, S. (2005). “The development of aggressive behaviors among girls: Measurement issues, social functions, and differential trajectories,” in The Development and Treatment of Girlhood Aggression, eds D. J. Pepler, K. C. Madsen, C. Webster, and K. S. Levene (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 105–136.

Avalos, L., Tylka, T. L., and Wood-Barcalow, N. (2005). The body appreciation scale: development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 2, 285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002

Bem, S. L. (1981). Bem Sex-Role Inventory: Professional Manual. Sunnyvale: Consulting Psychologist Press.

Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K., and Kaukiainen, A. (1991). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggress. Behav. 18, 117–127. doi: 10.1002/1098-2337199218:2<117::AID-AB2480180205<3.0.CO;2-3

Bowie, B. H. (2007). Relational aggression, gender, and the developmental process. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 20, 107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6171.2007.00092.x

Calogero, R. M., and Tylka, T. L. (2010). Fiction, fashion, and function: an introduction to the special issue on gendered body image, part I. Sex Roles 63, 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9821-3

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Salawani, G. M., and Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Dev. 79, 1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x

Crothers, L. M., Field, J. E., and Kolbert, J. B. (2005). Navigating power, control, and being nice: aggression in adolescent girls’ friendships. J. Counse. Dev. 83, 349–354. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00354

Crothers, L. M., Schreiber, J. B., Field, J. E., and Kolbert, J. B. (2009). Development and measurement through confirmatory factor analysis of the young adult social behavior scale (YASB): an assessment of relational aggression in adolescence and young adulthood. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 27, 17–28. doi: 10.1177/0734282908319664

Dickinson, K. J. (2007). The relationship between relational forms of aggression and conformity to gender roles in adults. Diss. Abstr. Int. Sect. B Sci. Eng. 68:1920.

Etcoff, N., Orbach, S., Scott, J., and D’Agostino, H. (2004). The Real Truth About Beauty:A Global Report. White Paper. New York, NY: Strategyone.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Field, J. E., Crothers, L. M., and Kolbert, J. B. (2006). Fragile friendships: exploring the use and effects of indirect aggression among adolescent girls. J. Sch. Couns. 4, 3–10.

Frederickson, B. L., and Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: toward understanding women’s lived experience and mental health risks. Psychol. Women Q. 21, 173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Galambos, N. L. (2004). “Gender and gender development in adolescence,” in Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 2nd Edn, eds R. M. Lerner and L. Steinberg (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons), 233–262.

Gooden, A. M., and Gooden, M. A. (2001). Gender representation in notable children’s picture Books: 1995-1999. Sex Roles 45, 89–101. doi: 10.1023/A:1013064418674

Harriger, J. A., Calogero, R. M., Witherington, D. C., and Smith, J. E. (2010). Body size Stereotyping and internalization of the thin ideal in preschool girls. Sex Roles 63, 609–620. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9868-1

Hesse-Biber, S., Leavy, P., Quinn, C. E., and Zoino, J. (2006). The mass marketing of disordered eating and eating disorders: the social psychology of women, thinness and culture. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 29, 208–224. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2006.03.007

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modeling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 6, 53–60.

Iacobucci, D. (2010). Structural equation modeling: fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J. Consum. Psychol. 20, 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2009.09.003

Jones, D. C., and Crawford, J. K. (2006). The peer appearance culture during adolescence: gender and body mass variations. J. Youth Adolesc. 2, 257–269. doi: 10.1007/s10964-005-9006-5

Kolbert, J. B., Crothers, L. M., Kanyongo, G. Y., Ng, H. K. Y., Albright, C. M., and Fenclau, E. Jr., et al. (2012). Ego identity and relational and social aggression mediated by elaborative and deep processing. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol. 1, 98–108. doi: 10.6000/1929-4409.2012.01.10

Kolbert, J. B., Field, J. E., Crothers, L. M., and Schreiber, J. B. (2010). Femininity and depression mediated by social and relational aggression in late adolescence. J. Sch. Violence 9, 289–302. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2010.483181

Levant, R. F. (2011). Research in the psychology of men and masculinity using the gender role strain paradigm as a framework. Am. Psychol. 66, 765–776. doi: 10.1037/a0025034

Maccoby, E. E. (1990). Gender and relationships: a developmental account. Am. Psychol. 45, 513–520. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The Two Sexes: Growing up Apart, Coming Together. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). Integrating mediators and moderators in research design. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 21, 675–681. doi: 10.1177/1049731511414148

Michel, A. (1986). Down with Stereotypes!: Eliminating Sexism from Children’s Literature and School Textbooks. Paris: UNESCO.

Oliver, K. K., and Thelen, M. H. (1996). Children’s perceptions of peer influence on eating concerns. Behav. Ther. 27, 25–39. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80033-5

Parent, M. C., and Moradi, B. (2011). An abbreviated tool for assessing feminine norm conformity: Psychometric properties of the Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory-45. Psychol. Assess. 23, 958–969. doi: 10.1037/a0024082

Paxton, S. J., Schutz, H., Wertheim, E. H., and Muir, S. L. (1999). Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 108, 255–266. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.108.2.255

Pleck, J. H. (1995). “The gender role strain paradigm: An update,” in A new Psychology of Men, eds R. F. Levant and W. S. Pollack (New York, NY: Basic Books), 11–32.

Pressley, M., and McCormick, C. (2007). Child and Adolescent Development for Educators. New York, NY: Guilford.

Reulbach, U., Ladewig, E. L., Nixon, E., O’Moore, M., Williams, J., and O’Dowd, T. (2013). Weight, body image and bullying in 9-year-old children. J. Paediatr. Child Health 49, E288–E293. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12159

Richmond, K., Levant, R., Smalley, B., and Cook, S. (2015). The Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS):Dimensions and its relationship to anxiety and feminine gender roles. Women Health 55, 263–279. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2014.996723

Skelton, A. (1997). Studying hidden curricula: developing a perspective in the light of postmodern insights. Curric. Stud. 5, 177–193. doi: 10.1080/14681369700200007

Slater, A., and Tiggerman, M. (2010). Body image and disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys: a test of objectification theory. Sex Roles 63, 42–49. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9794-2

Swami, V., and Abbasnejad, A. (2010). Associations between femininity ideology and body appreciation among British female undergraduates. Pers. Individ. Differ 48, 685–687. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.12.017

Tolman, D. L., and Porche, M. V. (2000). The Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale: development and validation of a new measure for girls. Psychol. Women Q. 24, 365–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb00219.x

Tolman, D. L., Davis, B. R., and Bowman, C. P. (2016). “That’s just how it is”: a gendered analysis of masculinity and femininity ideologies in adolescent girls’ and boys’ heterosexual relationships. J. Adolesc. Res. 31, 3–31. doi: 10.1177/0743558415587325

Keywords: indirect aggression, bullying, body image, feminine ideology, relational aggression, social aggression

Citation: Buzgon J, Crothers LM, Schreiber JB, Schmitt AJ, Kolbert JB, Wadsworth J, Fidazzo A, Barron M and Steeves T (2022) Feminine Ideology, Body Appreciation, and Indirect Aggression in Girls. Front. Educ. 7:896247. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.896247

Received: 14 March 2022; Accepted: 15 June 2022;

Published: 04 July 2022.

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Stamatios Papadakis, University of Crete, GreeceFernando Barragán-Medero, University of La Laguna, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Buzgon, Crothers, Schreiber, Schmitt, Kolbert, Wadsworth, Fidazzo, Barron and Steeves. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jered B. Kolbert, a29sYmVydGpAZHVxLmVkdQ==

Julie Buzgon1

Julie Buzgon1 Laura M. Crothers

Laura M. Crothers James B. Schreiber

James B. Schreiber Jered B. Kolbert

Jered B. Kolbert Jacob Wadsworth

Jacob Wadsworth