- Applied College, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

Women’s entrepreneurship is critical to an economy’s growth and development, yet it faces a variety of difficulties. This study aims to conduct a theoretical assessment of women’s entrepreneurship in Yemen and examine the problems it faces in its development. The findings show that women entrepreneurs in Yemen face numerous hurdles, including social, cultural, and institutional barriers; financial constraints; a lack of entrepreneurial education and knowledge; and a deficiency in training and incubation support. Consequently, it is suggested that a complete ecosystem for women’s entrepreneurship be developed, involving various stakeholders and comprising different types of facilities capable of assisting women entrepreneurs and ensuring their optimum advantage.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have historically played an essential role in providing a consistent income for low-income people and reducing their social instability (Chu et al., 2007; Estrin and Mickiewicz, 2011; Li et al., 2020; Alshebami and Seraj, 2021; Cai et al., 2021; Chew et al., 2021; Rafiq and Muhammad, 2021). The account for the majority of emerging countries’ GDP (International Finance Corporation, 2000). The growth of SMEs can lead to enhanced women’s entrepreneurship and gender equality (Stevenson et al., 2010). However, to reap the maximum benefit of entrepreneurship in economic growth and other areas, both genders must be involved in the development cycle (Aidis et al., 2007). Women-owned firms account for between 25% and 33% of formal sector enterprises worldwide (Langowitz et al., 2005). Accordingly, they can provide a variety of chances for employment development and economic growth (Brush and Cooper, 2012; Banihani, 2020). Moreover, women’s employment aids in the recovery from conflict in impacted areas, which frequently leave them with the dual weight of economic and family responsibilities.

In many nations, entrepreneurship, in general, has received little attention, let alone women’s entrepreneurship (Langowitz et al., 2005). Although women entrepreneurs contribute to economic development, this is still insignificant compared to their male counterparts (Minniti and Arenius, 2003).

Women entrepreneurs worldwide have a great deal in common, mainly in relation to the difficulties and barriers they face. Although women’s entrepreneurship is expanding in the Middle East, they still have the lowest recorded proportion of Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA), at 4% (Salama, 2020). In addition, only about 28% of adult women in the Middle East are classified as economically active (Hattab, 2012), the lowest figure in the world. Further, women’s entrepreneurial engagement in the Arab area is the weakest in the world (UNDP, 2006), even though they play a crucial role in enhancing and diversifying the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Verheul et al., 2006) and providing outlets for the potential fulfillment and expression of women (Eddleston and Powell, 2008).

Compared to other parts of the world, the employment gap between men and women in the Arab world is quite wide (Mcloughlin, 2013) despite Islam’s support for women to increasingly exercise their rights in economic and social activities. Women in the Middle East, particularly in the Arab countries, continue to be hampered by conservative cultural practices that prevent them from obtaining their rights in economic participation, education, and other aspects of society. Furthermore, because women are more likely to work in industries with smaller enterprises (Niethammer, 2013), it is assumed that any externalities such as war will have a more significant impact on their business activities.

Consequently, when women run vulnerable small businesses in a challenging climate, they are likely to confront numerous obstacles, the most significant of which are the highly bureaucratic business environment and the lengthy and costly delays in their firms’ licensing, approval process. Additionally, economies in general are not predisposed to demand female labor due to cultural attitudes, generic regulations, and poor support systems (O’Sullivan et al., 2011). Other obstacles include a lack of high-quality education, limited labor market mobility, a lack of enforcement of laws protecting women’s rights, and limited access to financing (Mcloughlin, 2013).

Arab women entrepreneurs encounter a range of barriers that can frustrate their initiatives. These include gender-specific legislative barriers, insufficient budgets, minimal societal support, male partner control of the enterprise, a lack of research and data to drive an effective advocacy strategy, as well as a gender gap, cultural norms, and civil regulations. The security situation of their countries and internal instability may also deter women from becoming entrepreneurs (Mohsen, 2007; Sadi and Al-ghazali, 2010; Danis and Smith, 2012; Alkwifi et al., 2020; Salama, 2020). These hurdles, particularly the financial ones, highlight the importance of encouraging measures such as angel investment, government loans, and equity capital to assist women to pursue entrepreneurship and become self-sufficient, independent, and financially secure (Nuttner, 1993). Women can also be inspired to enter business by providing them with the essential skills, knowledge, and entrepreneurial education to help them gain confidence, improve their performance, and participate in company operations (Allen et al., 2007; Alshebami et al., 2020).

Yemen is similar to other Middle Eastern countries in its conservative society. Accordingly, because of accumulated cultural ideas and conventions, a perception toward women has developed that they should stay home to care for their children, leaving the economic activities solely to men as the family’s breadwinners. Such beliefs hinder women’s employment opportunities (UNDP, 2006) and prevent them from reaping the potential benefits of economic participation for their families. Furthermore, although the country has a law for SMEs that allows for the equal opportunity of men and women, women are regarded differently when opting to create their small firms due to their socially determined positions and limited access to networks (International Finance Corporation, 2007). Uneducated Yemeni women are not the only ones who are unemployed; educated women face the same difficulties in securing work. Consequently, entrepreneurship provides an ideal alternative for women in Yemen to enter and gain confidence in the workforce (Allen et al., 2007; Alshebami and Khandare, 2015).

In conclusion, the above discussion demonstrates the limited empirical and theoretical research on entrepreneurship in general in Yemen and on women entrepreneurs in particular. This highlights the need for more research to help develop the women’s entrepreneurship sector in this country. Accordingly, this article theoretically reviews the available literature, analyses the available challenges, provides several recommendations for policymakers, and creates a proposed entrepreneurship ecosystem for developing women entrepreneurs in Yemen.

Literature Review

Status of Women Entrepreneurs in Yemen

Yemen is one of the poorest Arab countries, with an international poverty rate of 18.8% and a national poverty rate of 48.6%. Since the end of 2014, the Yemeni economy has shrunk by 39%, according to the World Bank (2019). Internal conflicts and armed skirmishes in the country have wreaked havoc on the government’s economy and stability since 2015, resulting in a slew of economic and political issues and ultimately leading to a significant increase in poverty and unemployment. Armed confrontations have harmed almost every sector, but small and medium-sized women-owned enterprises have been particularly hard hit (Maasher, 2019). Although the entire population has suffered during these conflicts, women are especially adversely affected, as they must handle both the income-generating economic activities as well as the home responsibilities to support their families. They are compelled to seek employment to meet their necessities and to support their husbands.

Yemeni women are capable of conducting business, not just to support their families but also to succeed as entrepreneurs. However, their low contribution in the market is due to many factors, such as a lack of self-confidence and the business information, skills, and experience needed to establish a business. Moreover, restrictive educational practices, family roles and responsibilities, and barriers to economic engagement are problems for women in Yemen and other Arab countries, largely stemming from these societies’ local cultures (Hattab, 2012). This suggests that government should endeavor to foster the growth of women-owned businesses and their participation in the labor market.

Generally in Yemen, it is believed that women’s rightful place is in the home and that men are responsible to earn a living to support their families. Largely due to this negative cultural perception, Yemeni women have been prevented from contributing to their family’s standard of living and Yemen’s total GDP women. According to research, over 3 million Yemeni women and girls are at risk of gender violence, making Yemen the worst country in the world for gender inequality (Brady, 2019). The gender segregation in Yemen adds to the problem; on top of society’s negative perception of women’s participation in business, women themselves worsen this perception by allowing only female trainers or instructors to train them throughout the initial business phases (Niethammer, 2013). Also, despite their desire and motivation to start a business, entrepreneurs in Yemen, regardless of gender, lack confidence in the reliability and accuracy of the information provided about their potential businesses to investors, which contributes to a loss of trust, interest, and confidence among business investors in supporting proposed projects. Entrepreneurs in Yemen who can assess the potential of their enterprises and fully comprehend the interests and expectations of investors are few and far between (Qasem, 2017).

As a result, entrepreneurship is vastly underdeveloped in Yemen. Neither the government nor international agencies are focused on its growth and development, and its significance to the economy is largely overlooked. Even though women entrepreneurs expend a great deal of effort in starting their businesses and have success stories to tell, they also play a crucial role in their failure or in limiting their business scope by complying with the existing cultural norms and opting to work primarily in routine female business activities and ignoring other economic opportunities. According to the findings of the baseline survey conducted by the Social Fund for Development (SFD) in 2004, Yemen has around 310,000 businesses. Out of the total, 3% were women-owned businesses, and 77% of these were in the service sector, such as the beauty care, tailoring, education, health care, commerce, and retail services.

According to Burjorjee (2008), Yemeni women entrepreneurs are typically involved in very small-scale, home-based businesses with few opportunities to work outside the home. Their projects usually include sewing, incense manufacturing, textile buying and selling, perfumes, hairdressing, and animal husbandry. Previously, these projects were funded by microfinance institutions; however, the SMEPS and UNDP (2015) indicated that 73% of these enterprises had no access to external funding since the 2015 war began. To fund their endeavors, women rely on their savings and help from friends. Furthermore, it was revealed that 29% of women firm owners intended to use revenue diversification as a survival strategy.

Accordingly, training, monitoring, and consulting services are required to implement women’s business ideas and maximize the monies they obtain. Currently, mobile phones and other apps can be used by development programs and institutions operating in Yemen to communicate with female entrepreneurs and provide them with the necessary developmental skills, financial resources, and consulting services. Accordingly, the SFD, which is represented by different entities, has successfully adopted technology by using the WhatsApp application to provide technical support to women entrepreneurs with the assistance of experienced women business counselors. Private health clinics, import and export, manufacturing, reselling, and other services are all covered in this program. Other programs and business incubators, such as the Rowad Foundation, Block One Business Incubator, Youth Leadership Development Foundation (YLDF), and Khadija Program for Entrepreneurship Training and Business Incubation, were also launched before the 2015 confrontations in Yemen. Unfortunately, due to the present conflict in the country, many programs have been either halted or cut back. If strengthened, these foundations can play a vital role in promoting women’s entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship in general throughout the country.

Impediments to Women Entrepreneurship in Yemen

Many young women in Yemen have unique ideas but lack the skills to put them into action, the financial resources to fund them, and the management experience to oversee them. Self-sufficient women who want to improve their standard of living and support their families may be inspired to start small enterprises with the help of such initiatives and foundations. Yemeni women have excellent entrepreneurial talents, but they lack the ability, training, and support to develop those skills further and reach their full potential (Ahmad, 2011). They additionally face challenges related to high financial risk, lack of financing, economic barriers, lack of skills and supportive services, and an ineffective Yemeni educational system, which does not prepare Yemeni youth for the world of entrepreneurship (Qatinah, 2016). Additionally, high-interest rates, financial literacy, erroneous religious perceptions, and requested collateral on loans are all factors that need to be considered in enhancing women’s opportunities in business (Alshebami and Khandare, 2015).

Women entrepreneurs often face challenges besides financial ones, such as access to markets and networks and restrictive rules and regulations, even after receiving the necessary training and finishing the requisite programs. Women’s failure to establish income-generating activity is primarily due to their social culture, according to Stevenson et al. (2010). It is also due to the lack of a specific law aimed at protecting women from gender discrimination (Moyer et al., 2019). According to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Women are also concerned with how society perceives them, which may demotivate them from thinking entrepreneurially, attending a training program, or starting small projects. Women, in particular, therefore require training that is customized to their needs and takes into account their vulnerable social status.

In a patriarchal, morally dominated society that inhibits female-initiated business ventures, women are subject to many ethical, coded, and unwritten social mores (Roomi and Parrott, 2008). Therefore, to pave the way for women entrepreneurs and reduce the challenges they face in Yemen, it is necessary to provide them with an adequate environment equipped with essential facilities. It is also advisable to connect them with microfinance institutions, development organizations, incubators, and other mechanisms so they receive the required financial assistance and technical training to run their businesses successfully. Furthermore, the private sector should also support women entrepreneurs by either funding them directly or providing them with the necessary training and consultation that will enable them to obtain the funding and other assistance they need.

A Glance at Selected Yemen Individuals’ Economic Indicators

Table 1 shows that unemployed women account for about 54.7% of the workforce in Yemen, compared to 12.4% for men. This percentage demonstrates the impact of the gender gap in the country and indicates that the unemployment problem is a significant challenge. One solution to this systemic problem is to establish and promote a vibrant entrepreneurship ecosystem that paves the road for and motivates Yemeni individuals in general, and women in particular, to start new business ventures. The table also shows that women account for roughly 40% of discouraged job seekers, while men account for 60%. This could be attributed to previous governments’ longstanding poor performance and failure to support SMEs, as well as the country’s ongoing armed conflicts, which have forced hundreds of thousands of people to leave their jobs. In terms of workers in the informal sector, both men and women have achieved more than 60%, indicating that most Yemeni individuals work in this sector and rely on informal finance and qualifications. This could also mean a high level of financial exclusion of individuals as majority of them depend on informal sources for financing their needs.

In terms of the highly skilled labor force, women make up only 1.1% of the total, while men account for 6.8%, highlighting the need for more developmental training and assistance for both female and male entrepreneurs. Males make up 38.5% of the workers contributing to families, whereas women account for only 9.4%, a common occurrence due to the culture, which encourages women to stay at home while forcing men to go to work to support their family. Finally, the table shows that 31.3% of men and 26.1% of women in Yemen work for their own. Overall, it is clear from the previous discussion that an ecosystem supporting women’s entrepreneurship in Yemen and involving various stakeholders is required. Thus, the following section describes a proposed women entrepreneurship ecosystem for Yemen.

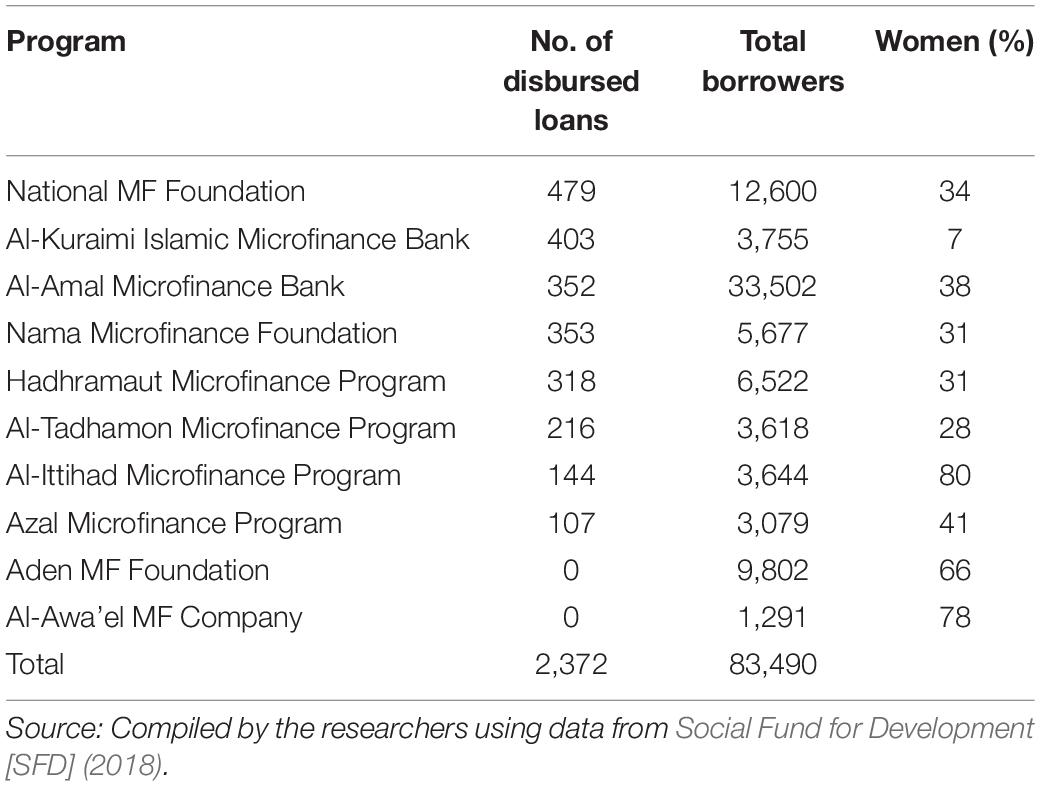

Table 2 shows that practically all the MFIs in Yemen support women; however, due to the current war and internal disputes, the number of active women entrepreneurs has decreased to 83,490 from 120,839 in 2014. However, despite the ongoing economic slump and volatility, women demonstrate a high borrowing rate, indicating an increased interest and willingness to start small businesses despite cultural and local customs barriers. The MFIs mentioned above and the programs they represent appear to be ineffective; sadly, they do not provide a comprehensive bundle of various sorts of microfinance products and services to assist women. The majority of them give microcredit, while others offer loans for consumption, which is completely counter to the objective of microfinance as a tool for poverty alleviation and employment creation. Training and support should be provided in tandem with the financial assistance provided to women entrepreneurs to ensure they get the most out of it and minimize their potential risks as much as feasible.

Proposed Ecosystem for Women Entrepreneurship in Yemen

People with an entrepreneurial mentality are anticipated to perform better than those with a conservative one. However, to build the entrepreneurial mindset of people in general, the right environment is required to encourage them to think creatively and act innovatively. In Yemen, however, people are generally motivated to innovate but lack the necessary resources to do so. Therefore, the study recommends that an entrepreneurial ecosystem framework be established for Yemeni women, aimed at assisting policymakers in paving the way for entrepreneurship and overcoming the obstacles they currently face.

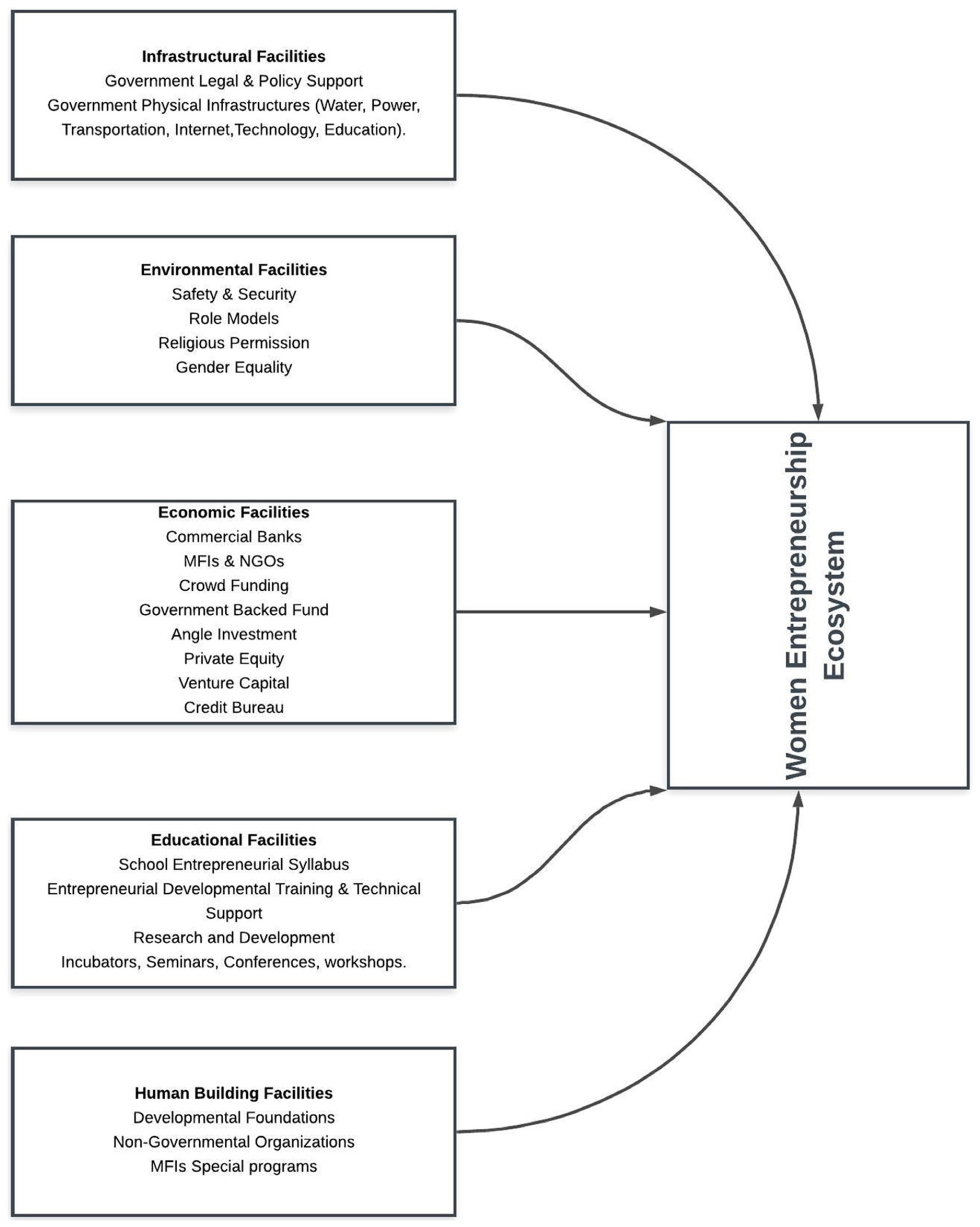

Figure 1 depicts the recommended model for promoting female entrepreneurship in Yemen. It emphasizes the importance of providing an environment containing essential infrastructural facilities, such as government assistance and legislation, and social and cultural facilities, such as social support, gender equity, role models, and gender equity. The approach also underlines the importance of working with various financial institutions, MFIs, commercial banks, crowdfunding platforms, and other financing facilities to provide the necessary financial support. Moreover, it is vital to focus on developing the country’s educational system by incorporating entrepreneurial education into school and university curricula and establishing the requisite incubators and training centers. There is also a need to develop individuals and their abilities, which can be accomplished by setting the required developmental foundations and programs. In conclusion, decision-makers in Yemen must consider all these elements when developing policies to encourage women’s entrepreneurship in order to maximize the benefits to the country and its citizens.

Figure 1. Proposed framework for women entrepreneurship ecosystem in Yemen. Source: Modified from Isenberg (2011).

Discussion

This study aimed to understand the status of women entrepreneurship in Yemen and identify the crucial factors restricting its growth and development. Despite the limited literature on this topic, it is apparent that Women entrepreneurs in Yemen are confronted with numerous problems and difficulties that stifle their growth and development. A major impediment is that they are unable, through the lack of support, to comprehend their business concepts fully and, as a result, fail to garner the attention and meet the expectations of local or international investors, thus resulting in the loss of funding opportunities.

Furthermore, Yemen’s flawed and corrupt judicial system is ineffective in defending women’s rights. It has been further found that the lack of property management legislation leads to confrontations and disagreements among entrepreneurs who want to buy a property and start a business. In addition, weak economic reforms and bankruptcy rules pose a barrier to women’s participation in the business sector. Women’s prospects of flourishing in the market and competing with other rivals are limited due to a lack of financial support, technical training, coaching services, and developmental programs. There are also inadequate physical facilities, such as power, roads, internet, networks, and other services, in the country to support entrepreneurial activity. These findings are in line with previous studies conducted globally (Minkus-Mckenna, 2009; Ahmad, 2011; Fallatah, 2012; De Vita et al., 2014; Alshebami and Khandare, 2015; Alshebami and Rengarajan, 2017; Nsengimana and Tengeh, 2017; Mathew, 2019; Aljarodi, 2020; Cai et al., 2021).

Additionally, the local market is dominated by a few corrupt families, who only allow their products to be manufactured. This leads to monopoly and control of the markets, which is considered a significant barrier to women’s entry into business. It is also reported that women in Yemen face cultural challenges, such as the lack of social mobility and male dominance of the country’s businesses. In addition, women face the challenge of inadequate support from family and friends. These challenges are supported by numerous studies (Sadi and Al-ghazali, 2010; Danis and Smith, 2012; Welsh et al., 2014; Al-ghamri, 2016; AbuBakar et al., 2017; Alkhaldi et al., 2018; Alhothali, 2020).

Finally, despite their intention and willingness to carry out business activities, women entrepreneurs must improve their human capital, emotional intelligence, psychological capital, knowledge and skills, and entrepreneurial mindset. All these factors contribute to directing their behavior and thinking toward familiarizing themselves with business environments and know-how in order to achieve their objectives (Sadi and Al-ghazali, 2010; Ahmad, 2011; Darley and Khizindar, 2015; Alkwifi et al., 2020; Alshebami and Alamri, 2020).

Conclusion

Women’s economic participation in society offers them the opportunity to achieve their goals and support their families, which also benefits children and men (OCED, 2017). However, in many regions of the world, including Yemen, women entrepreneurs remain an untapped source of wealth and face numerous hurdles that stifle their growth and development.

These include constraints related to social and cultural factors, financial support, knowledge and training support, institutional support, and entrepreneurial education and skill development. Women entrepreneurs can be discouraged by a lack of finances, training, and consultation; economic instability, ongoing armed conflicts, and religious restrictions. These circumstances may lead to women working in the informal sector, where they receive low wages for low-quality work.

Consequently, there is a need to increase women’s propensity to work in business, which could be accomplished by restructuring school and university educational curricula and designing them to meet the needs of markets, as well as preparing graduates with the entrepreneurial intention, skills, and mindset needed to turn their innovative ideas into successful business ventures. Yemeni women entrepreneurs’ attitudes, mindsets, abilities, self-confidence, and behavior must also be fostered and strengthened. Moreover, there is a compelling need to nurture leadership qualities, such as creativity, sound judgment, emotional intelligence, psychological capital, and so on. Also, initiatives designed to provide women entrepreneurs with the required skills, information, and training should collaborate with international financing organizations to ensure they optimize their opportunities. Further, it is vital to create awareness about the value of small and micro businesses and entrepreneurship and share triumphant tales of female entrepreneurs in the media, which can boost the translation of new ideas into business initiatives.

Additionally, new and young businesses require assistance to ensure their survival and growth, which can be accomplished by increasing access to advisory services and the use of technology in the workplace. Laws should be written to discourage discrimination against women when it comes to starting a business or carrying out commercial operations; laws should be gender-agnostic. In addition, the government should encourage the private sector, particularly financial institutions, to improve their regulatory environments for aiding women entrepreneurs. Moreover, research and development should investigate potential investment opportunities for women entrepreneurs and show how they can successfully access and benefit from them. Lastly, a greater focus on designing capacity-building programs for women entrepreneurs that are congruent with cultural norms and practices is required.

In conclusion, it should be mentioned that supporting and developing women entrepreneurs in Yemen begins from the ground up. It necessitates a concerted effort from all market sectors, actors, government, and international institutions. As a result, there is a pressing need to create a thriving women’s entrepreneurship ecosystem capable of providing the necessary support and facilities to female entrepreneurs. The government should establish an entrepreneurship development strategy in coordination with the private sector, MFIs, NGOs, international organizations, commercial banks, developmental foundations, investors, and other relevant parties. The joint effort undertaken by these stakeholders in Yemen will allow women entrepreneurs to develop their knowledge and skills, benefit from available resources, and reduce their uncertainty and risk in starting businesses. On a larger societal scale, this will ultimately help to mitigate poverty and unemployment and increase the country’s economic growth and development.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported through the Annual Funding track by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Project No. AN000200).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AbuBakar, A. R., Ahmad, S. Z., Wright, N. S., and Skoko, H. (2017). The Propensity to Business Startup: evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data in Saudi Arabia. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 9, 263–285. doi: 10.1108/jeee-11-2016-0049

Ahmad, S. (2011). Evidence of the Characteristics of Women Entrepreneurs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: an Empirical Investigation. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 3, 123–143. doi: 10.1108/17566261111140206

Aidis, R., Welter, F., Smallbone, D., and Isakova, N. (2007). Female Entrepreneurship in Transition Economies: the Case of Lithuania and Ukraine. Fem. Econ. 13, 157–183. doi: 10.1080/13545700601184831

Al-ghamri, N. (2016). The Negative Impacts of Commercial Concealment on the Performance of Small Businesses in Jeddah Province in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Econ. Finance 8, 124–142. doi: 10.5539/ijef.v8n8p124

Alhothali, G. T. (2020). Women Entrepreneurs Doing Business from Home: motivational Factors of Home-based Business in Saudi Arabia. Adalya J. 9, 1242–1274.

Aljarodi, A. (2020). Female Entrepreneurial Activity in Saudi Arabia: An Empirical Study, Doctorate in Entrepreneurship and Management Bellaterra. Ph.D. thesis. Cerdanyola Del Valles: Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, International.

Alkhaldi, T., Cleeve, E., and Brander-brown, J. (2018). “Formal Institutional Support for Early-Stage Entrepreneurs: evidence from Saudi Arabia,” in International Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 903–908.

Alkwifi, O. S., Khoa, T. T., Ongsakul, V., and Ahmed, Z. (2020). Determinants of Female Entrepreneurship Success across Saudi Arabia. J. Trans. Manag. 25, 3–29. doi: 10.1080/15475778.2019.1682769

Allen, E., Elam, A., Langowitz, N., and Dean, M. (2007). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2007 Global Report on high-growth Entrepreneurship. London: Global Entrepreneurship Research Association

Alshebami, A., Al-jubari, I., Alyoussef, I., and Raza, M. (2020). Entrepreneurial education as a predictor of community college of Abqaiq students ’ entrepreneurial intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 10, 3605–3612. doi: 10.5267/j.msl.2020.6.033

Alshebami, A., and Alamri, M. (2020). The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Enhancing the Ambition Level of the Students: mediating Role of Students ’ Commitment to University. Talent Dev. Excell. 12, 2275–2287.

Alshebami, A., and Khandare, D. (2015). The Role of Microfinance for Empowerment of Poor Women in Yemen. Int. J. Soc. Work 2, 36–44. doi: 10.5296/URL

Alshebami, A., and Seraj, A. (2021). The Impact of Intellectual Capital on the Establishment of Ventures for Saudi Small Entrepreneurs: GEM Data Empirical Scrutiny. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. 11, 129–142. doi: 10.48047/rigeo.11.08.13

Alshebami, S. A., and Rengarajan, V. (2017). Microfinance Institutions in Yemen “Hurdles and Remedies.”. Int. J. Soc. Work 4:10. doi: 10.5296/ijsw.v4i1.10695

Banihani, M. (2020). Empowering Jordanian Women through Entrepreneurship. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 22, 133–144. doi: 10.1108/JRME-10-2017-0047

Brady, K. (2019). Empowering women in Yemen’s civil war. Avaliable Online at: https://www.dw.com/en/empowering-women-in-yemens-civil-war/a-50586064. (accessed on 29 Sep, 2020)

Brush, C. G., and Cooper, S. Y. (2012). Female Entrepreneurship and Economic Development: an International Perspective. Entrep. Reg. D. 24, 1–6. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2012.637340

Burjorjee, D. (2008). Microfinance Gender Study: A Market Study of Women Entrepreneurs in Yemen Prepared for the Social Fund for Development by: Microfinance Gender Study: A Market Study of Women Entrepreneurs in Yemen. Germany: KFW.

Cai, L., Murad, M., Ashraf, S. F., and Naz, S. (2021). Impact of dark tetrad personality traits on nascent entrepreneurial behavior: the mediating role of entrepreneurial intention. Front. Bus. Res. China 15:7. doi: 10.1186/s11782-021-00103-y

Chew, T. C., Tang, Y. K., and Buck, T. (2021). The Interactive Effect of Cultural Values and Government Regulations on Firms ’ Entrepreneurial Orientation. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 29, 221–240. doi: 10.1108/JSBED-06-2021-0228

Chu, H., Benzing, C., and Mcgee, C. (2007). Ghanaian and Kenyan Entrepreneurs: a Comparative Analysis of Their Motivations, Success Characteristics and Problems. J. Dev. Entrep. 12, 295–322. doi: 10.1142/s1084946707000691

Danis, A., and Smith, H. (2012). Female Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 4, 216–235. doi: 10.1108/17566261211264136

Darley, W. K., and Khizindar, T. M. (2015). Effect of Early-Late Stage Entrepreneurial Activity on Perceived Challenges and the Ability to Predict Consumer Needs: a Saudi Perspective. J. Trans. Manag. 20, 67–84. doi: 10.1080/15475778.2015.998145

De Vita, L., Mari, M., and Poggesi, S. (2014). Women Entrepreneurs in and from Developing Countries: evidences from the Literature. Eur. Manag. J. 32, 451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2013.07.009

Eddleston, K. A., and Powell, G. N. (2008). The Role of Gender Identity in Explaining Sex Differences in Business Owners’ Career Satisfier Preferences. J. Bus. Ventur. 23, 244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.11.002

Estrin, S., and Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Institutions and Female Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. Entrep. J. 37, 397–415. doi: 10.1007/s11187-011-9373-0

Fallatah, H. (2012). Women Entrepreneurs in Saudi Arabia: Investigating Strategies used by Successful Saudi Women Entrepreneurs, Degree of Master of Business Management. Ph.D. thesis. England: Lincoln University Digital.

Hattab, H. (2012). Towards understanding female entrepreneurship in Middle Eastern and North African countries: a cross-country comparison of female entrepreneurship. Educ. Bus. Soc. Contemp. Middle Eastern Issues 5, 171–186. doi: 10.1108/17537981211265561

International Finance Corporation (2000). Paths Out of Poverty, The Role of Private Enterprises in Developing Countries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

International Finance Corporation (2007). Women Entrepreneurs in the Middle East and North Africa: Characteristics, Contributions and Challenges. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

Isenberg, D. (2011). The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship. Dublin, Ireland: Institute of International and European Affairs, 1–13.

Langowitz, N., Minniti, M., and Arenius, P. (2005). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2004 Report on Women and Entrepreneurship. Available Online at: www.gemconsortium.org (accessed March 12, 2022).

Li, C., Murad, M., Shahzad, F., Aamir, M., and Khan, S. (2020). Entrepreneurial Passion to Entrepreneurial Behavior: role of Entrepreneurial Alertness. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Proactive Personality. Front. Psychol. 11:1611. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01611

Maasher, B. (2019). Empowering women entrepreneurs in Yemen to sustain quality education amidst a devastating conflict. from Women Enterprises Finance Initiative. Avaliable Online at : https://we-fi.org/empowering-women-entrepreneurs-in-yemen-to-sustain-quality-education-amidst-a-devastating-conflict/. (accessed on 29 Sep, 2020).

Mathew, V. (2019). Women Entrepreneurship in Gulf Region: challenges and Strategies In GCC. Int. J. Asian Bus. Inf. Manag. 10, 94–108. doi: 10.4018/IJABIM.2019010107

Mcloughlin, C. (2013). Women’s economic role in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report). Birmingham, UK: Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, University of Birmingham.

Minkus-Mckenna, D. (2009). Women Entrepreneurs in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Working Paper Series, 2. Maryland: University of Maryland University College (UMUC).

Minniti, M., and Arenius, P. (2003). “Women In Entrepreneurship,” in Paper presented at The Entrepreneurial Advantage of Nations: First Annual Global Entrepreneurship Symposium, (New York: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor), doi: 10.1007/s11365-007-0051-2

Mohsen, D. K. (2007). Arab women entrepreneurs and SMEs: challenges and realities. Retrieved from Daily News, Egypt. Available Online at: https://dailynewsegypt.com/2007/02/11/arab-women-entrepreneurs-and-smes-challenges-and-realities/ (accessed January 2, 2022).

Moyer, J. D., Bohl, D., Hanna, T., Mapes, B. R., and Rafa, M. (2019). Assessing the Impact of War on Development in Yemen. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Niethammer, C. (2013). Women, Entrepreneurship and the Opportunity to Promote Development and Business. The 2013 Brookings Blum Roundtable Policy Briefs. Washington, D.C: Brookings, 31–39.

Nsengimana, S., and Tengeh, R. K. (2017). The Sustainability of Businesses in Kigali, Rwanda: an Analysis of the Barriers Faced by Women Entrepreneurs. Sustainability 9, 1–9. doi: 10.3390/su9081372

Nuttner, E. (1993). Female entrepreneurs: how far have they come? Bus. Horiz. 36, 59–65. doi: 10.1016/S0007-6813(05)80039-4

OCED (2017). Women’s Participation in the Labour Market and Entrepreneurship in Selected MENA Countries. Available online at: doi: 10.1787/9789264279322-5-en

O’Sullivan, A., Rey, M., and Mendez, J. G. (2011). Opportunities and Challenges in the MENA Region. In Arab world competitiveness report, 2012. Working paper. Available online at: http://www.oecd.org/mena/49036903.pdf. (accessed on 10 Dec, 2015).

Qasem, A. (2017). To build an entrepreneurship ecosystem in Yemen. Available Online at: http://www.rowad.org/?blog_post=to-build-an-entrepreneurship-ecosystem-in-yemen (accessed November 12, 2021).

Qatinah, A. (2016). Market Assessment: Enhanced Rural Resilience in Yemen Programme (ERRY). New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Rafiq, M., and Muhammad, R. (2021). Impact of Entrepreneurial Education, Mindset, and Creativity on Entrepreneurial Intention: mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 12:724440. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724440

Roomi, M. A., and Parrott, G. (2008). Barriers to Development and Progression of Women Entrepreneurs in Pakistan. J. Entrep. 17, 59–72. doi: 10.1177/097135570701700105

Sadi, M. A., and Al-ghazali, B. M. (2010). Doing Business with Impudence: a focus on Women Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 4, 1–11.

Salama, H. (2020). Women Entrepreneurship in MENA: An Analysis., from ECOMENA -Echoing Sustainability in MENA. Available Online at: https://www.ecomena.org/women-entrepreneurship-in-mena/ (accessed on 29 Sep, 2020).

SMEPS, and UNDP (2015). Rapid Business Survey: Impact of The Yemen Crises on Private Sector Activity. New York: United. Nations Development Programme.

Social Fund for Development [SFD] (2018). The Social Fund for Development, Anual Report. In The Social Fund for Development. Yemen: Social Fund for Development.

Stevenson, L., Daoud, Y., Sadeq, T., and Tartir, A. (2010). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: GEM-MENA Regional Report 2009 (Middle East and North Africa). Ottawa, Canada: International Development Research Centre.

UNDP (2006). The Arab Human Development Report: Towards the Rise of Women in the Arab World. New York: UNDP, doi: 10.5860/choice.44-6583

Verheul, I., Van Stel, A., and Thurik, R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 18, 151–183. doi: 10.1080/08985620500532053

WEF (2018). The Global Gender Gap Report 2018: South Asia. In World Economic Forum. Available online at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2018.pdf

Welsh, D. H. B., Memili, E., Kaciak, E., and Al, A. (2014). Saudi Women Entrepreneurs: a Growing Economic Segment. J. Bus. Res. 67, 758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.040

Keywords: SMEs, gender, culture, ecosystem, development, entrepreneurs

Citation: Alshebami AS and Alzain E (2022) Toward an Ecosystem Framework for Advancing Women’s Entrepreneurship in Yemen. Front. Educ. 7:887726. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.887726

Received: 01 March 2022; Accepted: 01 April 2022;

Published: 26 April 2022.

Edited by:

Majid Murad, Jiangsu University, ChinaReviewed by:

Kalpina Kumari, Greenwich University, PakistanFarhan Mirza, University of Management and Technology Sialkot, Pakistan

Copyright © 2022 Alshebami and Alzain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Saleh Alshebami, YWFsc2hlYmFtaUBrZnUuZWR1LnNh

Ali Saleh Alshebami

Ali Saleh Alshebami Elham Alzain

Elham Alzain