- Centre for University Teaching and Learning, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

Argumentative writing is the central generic skill in higher education studies. However, students have difficulties in basic argumentation skills. Novice students do not necessarily receive adequate guidance, and their prior education may not have supported the requirements of higher education writing. Position-taking is at the core of argumentation, but students are often hesitant to make their point. Furthermore, they may have an incorrect and one-sided perception about an argument, leading them to avoid alternative positions in their argumentative writing. The study aims to explore starting level skills of novice students’ argumentative writing, namely their position-taking. The participants were 196 first-year students from diverse fields of study in two Finnish higher education institutions. They were required to solve a problem and write an argumentative essay based on five documents that were given to them. The essays were analyzed using qualitative content analysis applying abductive approach. Substantial variation was detected in students’ position-taking. We identified four groups of writers based on their position-taking. First two groups were more or less explicit in their position-taking. Most of the students (72%) belonged to these two groups. However, a minority of them were consistent in their position-taking. Writers in the third group (15%) implied their position, and writers in the fourth group (12%) stuck to summarizing sources without position-taking. The findings invite teachers to support novice students in their basic argumentation. Co-operation between faculty teachers and writing teachers is encouraged.

Introduction

Generic skills have been considered vital for success in higher education studies (Barrie, 2006; Shavelson, 2010; Hyytinen et al., 2019). They are universal expert skills, such as communication, problem solving and argumentation, and they are equally important in all fields, enabling learning discipline-specific skills and knowledge (Hyytinen et al., 2021a). The central generic skill is argumentation (Andrews, 2009; Mäntynen, 2009; Wolfe, 2011; Wingate, 2012). Argumentation, and more specifically argumentative writing, is required of the students from the moment they apply and enter a higher education institution, until graduation, in the form of essays, examinations, and dissertations (see Wolfe, 2011; Wingate, 2012). Even more important, it is not just a technical skill, to pull through assignments, but argumentation also facilitates learning (Asterhan and Schwarz, 2016; Iordanou et al., 2019; Kuhn, 2019). Research on generic skills often focuses on clusters of skills, their importance, and students’ experiences of them (e.g., Barrie, 2006; Tuononen et al., 2019; Virtanen and Tynjälä, 2019). However, such an approach offers few practical insights for higher education teachers who often struggle between teaching discipline-specific knowledge and supporting students in their generic skills. Instead, gaining a more detailed understanding of students’ strengths and weaknesses in each generic skill, such as argumentation, will help in developing tools for teachers.

Several studies show that even advanced higher education students have gaps in their basic argumentation skills, such as combining claims and evidence, or presenting diverse viewpoints (Marttunen, 1994; Ivanič, 1998; Andrews et al., 2006; Laakso et al., 2016; Hyytinen et al., 2017, 2021b; Breivik, 2020). Students may be unsure about what an argument is (Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012; Breivik, 2020). They may also have difficulties in identifying rhetoric situations and their expectations and adapting their writing for the requirements of each assignment (Zimmerman and Risemberg, 1997; Johns, 2008; Roderick, 2019). It has been suggested that prior education does not provide sufficient argumentative skills, but students in higher education still feel that they do not receive adequate guidance or instructions on elements of argumentative writing (Andrews, 2009). Teachers often assume that students either already master these skills or learn as they go. Surprisingly, even though argumentative writing has been thought to be the Achilles’ heel in the transition to higher education, little research has focused on actual novice students’ starting level skills. We know a lot more about advanced students’ or even senior scholars’ argumentative skills. The present study focuses on novice students’ basic skills in argumentative writing, namely describing the variation in the ways of their position-taking, which is viewed as the core of argumentation (Andrews et al., 2006; Wingate, 2012).

Argumentation and Argumentative Writing in Higher Education

The objective of an argument is to support one’s claims and conclusions with reasons or evidence (Toulmin, 2003; Halpern, 2014). In academic contexts, the claims and conclusions are backed with prior research and/or empirical data (Swales, 1990; Wolfe, 2011). In argumentative guidebooks, an argument is often presented as a simple one or two sentence structure, but in practice it is often integrated in broader entities such as written essays or articles, or spoken addresses or debates (see Andrews, 2009). Most assignments that a higher education student—across disciplines—encounters during their studies require argumentative writing (Wolfe, 2011). Assignments that require argumentation have also been considered a valuable tool for learning. Such assignments have been found to be a particularly advantageous method when learning about complex topics with diverse viewpoints and complex skills such as critical thinking (Asterhan and Schwarz, 2016; Iordanou et al., 2019; Kuhn, 2019).

There is no template for constructing an argumentative text, but the writer must identify the requirements of the situation, and the best ways to fulfill those requirements (see Johns, 2008). A major decision in argumentative writing is related to choosing the placing of claims or conclusions and evidence. These rhetorical strategies are culture-specific to some degree; in other words, one strategy may be favored over another, across genres and communities. For instance, Finnish writers have been found to prefer to present all evidence and elements of uncertainty before their conclusion (final focus), in contrast to Anglo-American writers who prefer to present their inference first and then proceed to evidence (initial focus) (Mauranen, 1993; Mikkonen, 2010; see also Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969).

In addition to variation across cultures, argumentative skills have also been suggested to be, at least in part, discipline-specific (Andrews, 2009, 2015). Accordingly, there are disciplinary differences in the epistemologies that influence how to evaluate an argument (e.g., Hetmanek et al., 2018). However, beyond the varying conventions of cultures and disciplines, arguments and argumentative texts have more generic features. This includes development and presentation of one’s position (Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012), and micro- and macrostructures of argumentation, such as claim or conclusion and evidence, and introduction, counterarguments, and discussion (Kuhn, 1991; Toulmin, 2003; Breivik, 2020). To learn the discipline-specific conventions of argumentation, it is necessary to master the generic features. Consequently, the ability to use generic features of argumentation is eminently important for novice students who are new to higher education. They are not yet integrated in their study program or academic writing community (Swales, 1990; Donald, 2002). However, despite the lack of relevant skills, novice students receive little guidance in argumentative writing. In the absence of proper guidance to academic requirements, they are tapping into the skills they have learnt in their prior education (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Andrews et al., 2006). In Finland, it has been suggested that argumentation is not sufficiently emphasized in the upper secondary school, and its final exams, the Matriculation Examination (Mäntynen, 2009; Komppa, 2012). However, evidence-based information about Finnish novice higher education students’ argumentative writing is scarce. While we know that they have some problems in consistency of their arguments (Hyytinen et al., 2017), there is no research on more generic features in argumentative writing.

Position-Taking in Argumentative Writing

Taking a position is at the core of argumentation (Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012). Typically, the position is seen as the viewpoint the writer intends to support, or the main point the writer intends to make. The position conveys the writer’s explicit presence in the text (Mauranen, 1993; Hyland, 2005). Additionally, to strengthen the argument, the position can be challenged with alternative positions (see Andrews, 2009). Failing to take a position can lead to problems in higher education studies where argumentation skills are vital (e.g., Wolfe, 2011). Such problems often go hand in hand with problems in deep learning and meaning construction (Biggs, 1988; see also Petrić, 2007).

In argumentative writing, the position is often expressed as a thesis, a holistic main claim that summarizes the writer’s point of view (Kakkuri-Knuuttila and Halonen, 1998; Mikkonen, 2010; Wolfe, 2011). However, the position is not always expressed as explicitly as a thesis. Indeed, it has been found that higher education students have challenges in emphasizing their position, and instead, they may lean toward research sources, as well as summarizing, and attributing (Lea and Street, 1998; Petrić, 2007; Mäntynen, 2009; McCulloch, 2012; Laakso et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2018). Consequently, they do not take a position, but they rather display their knowledge on the topic (see Petrić, 2007). Higher education students can feel inadequate for making a strong point (Ivanič, 1998; Andrews, 2009; Mendoza et al., 2022). They may avoid making a holistic statement like a thesis by making so called local arguments. These are claims that encompass a short proportion of the text, and do not summarize the point of view of the entire text (Mauranen, 1993; Wolfe, 2011). However, writers may also imply their position in more subtle ways than stating an explicit thesis or even making local arguments. Linguists talk about interactional features, referring to elements that convey writer’s relation with their text (Hyland and Tse, 2004; Hyland, 2005). Writers might withhold (hedge) or emphasize (boost) their commitment, express their affective attitudes (attitude marker), or use first-person forms to remind reader of their presence in the text (self-mention) (Hyland, 2005).

Discussion of diverse viewpoints, i.e., alternative positions, is an important yet challenging part of argumentation (Kuhn, 1991; Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012; Kuhn et al., 2016b). In its strongest form, a rebuttal, an explicit position is taken against some evidence. Just as they may be hesitant in their position-taking, as discussed above, even advanced higher education students may have challenges in introducing alternative positions in their argumentation (Laakso et al., 2016; Hyytinen et al., 2021b; Kuhn and Modrek, 2021). Even acknowledgment of alternative positions is difficult for many, not to mention rebutting them (Kuhn, 1991). This tendency has been called my-side bias, indicating an inability to see other alternatives (Perkins, 1989). However, these challenges may not be about an inclination to emphasize one’s own opinion but instead they reflect the writer’s incorrect perception of an argument (Wolfe and Britt, 2008; Wingate, 2012). Writers may see a good argument as a one-sided construction, and so they bring out all the supporting evidence, and leave out any contesting facts. The ability to develop rebuttals requires a basic understanding of position-taking, and usually, the presence of rebuttals is an indication of a higher overall quality of argumentation (Wolfe et al., 2009; Kuhn et al., 2016a).

The variation in position-taking can be a consequence of either hesitancy or uncertainty (Ivanič, 1998; Andrews, 2009; Lee et al., 2018) or an incorrect perception about position-taking and the characteristics of an argument (Wolfe and Britt, 2008; Andrews, 2009; Breivik, 2020). However, research has pointed out other reasons students may avoid position-taking. Cultural conventions, such as inclination to minimize writer presence in a text, can add to the challenge (Mauranen, 1993). Furthermore, the tendency to reward students for showing what they know instead of constructing new meanings discourages writers from developing their own positions (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Andrews, 2009). Overall, some writers intend to present all available evidence, in contrast to writers who intend to construct new information based on available evidence (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Biggs, 1988). Some interesting contrasting findings suggest that assignment directions could be a culprit behind the challenges. The writer may not correctly identify the requirements of an assignment. It has been found that even when explicit requests are made for position-taking, writers may fall back on a strategy of summarizing sources (Macbeth, 2006; Andrews, 2009; Paldanus, 2017). However, when the directions come across, higher education students and even younger adolescents are able to present an explicit position (Marttunen, 1994; Marttunen and Laurinen, 2004; Mikkonen, 2010).

The Research Gap and Objective of the Study

Argumentative writing is demanding, and novice students cannot be expected to master the conventions and hidden rules of the academic context (Swales, 1990; Ivanič, 1998; Macbeth, 2006; Johns, 2008; Andrews, 2009). To understand where novice students stand in their argumentative writing skills, all dimensions of argumentation need to be studied; implementing logic, rhetoric, and dialectic approaches. A tendency in the research of argumentation in the higher education studies is to focus on the validity and quality of arguments (cf. Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012). However, if students do not understand what an argument is or are not able to formulate their arguments on a textual level, teaching more abstract and often discipline-specific aspects of argumentation, such as validity, may be futile. Furthermore, novice students’ preparedness for argumentative writing in the academic context has been questioned, but research-based understanding of the matter is insufficient. Thus, the present study investigates novice students’ argumentative writing on a very basic level, namely focusing on their position-taking skills. Such investigation will bring insights into supporting novice students in their studies. The growing understanding of novice students’ starting level skills will help not only writing teachers, but all teachers in higher education who are involved in giving writing assignments.

The aim of our study was to explore starting level skills of novice higher education students’ argumentative writing. In more detail, we investigate how they take a position in an argumentative essay, and how they present alternative positions. Our specific research questions were:

RQ1: What kind of variation is there in students’ presentations of their position?

RQ2: What kind of variation is there in students’ presentations of alternative positions?

RQ3: What types of argumentative writers can be identified based on the findings in RQ1 and RQ2?

Materials and Methods

Context of the Study

Higher education admissions in Finland are extremely competitive (OECD, 2019). Until recently, all applicants have participated in discipline-specific entrance examinations, but recently more emphasis was put on academic achievement in prior education (Kleemola and Hyytinen, 2019). The upper secondary school in Finland consists of a general and a vocational track. The aim of the general track is to give students extensive general knowledge and to prepare them for further education either in higher education or in vocational training. While the general track introduces all subjects to all students, different emphases are allowed, such as mathematics, natural sciences, or languages. In contrast, the vocational track aims to give students vocational competence in their chosen field. Some general subjects are taught, but the focus is on vocational skills. It is noteworthy that both general and vocational tracks give eligibility for higher education admissions. Thus, novice students in higher education have varied academic backgrounds.

Participants and Data Collection

The data were collected in accordance with the ethical principles of research with human participants by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (2019). Students gave their consent to participation. The data were collected in a national project on higher education students’ generic skills (Ursin et al., 2021). Based on instructions and templates provided by the project, administrators, and teachers in participating institutions invited students via e-mail. Approximately 25% of the invited students participated. In the national project, 1538 first-year students participated in the early stages of their first study term. Participation was voluntary, and students could withdraw from the research at any time. Sixty-nine students did not complete the assessment, and they were not included in any analyses. For the purposes of the present study, a subsample of the data was selected. The aim was to sample a subgroup that would represent a wide range of disciplines, and the variation in argumentative writing within the whole data. With these aims in mind, two large multidisciplinary higher education institutions in southern Finland were selected to represent the data. The selection of students in two institutions instead of a random sample across the 18 participating institutions ensured that there was not too much contextual variation in the students of the subgroup. One of the institutions was a research-intensive university (99 students) and one was a university for applied sciences (97 students). The subgroup of 196 Finnish-speaking students covered the whole range of performance levels in the national project, assessing generic skills. Thus, it was assumed that the subsample would represent the variation in argumentative writing within the whole data. Students represented a diversity of study fields, including healthcare, humanities, biosciences, engineering, natural sciences, and social sciences, covering most of the key disciplines. While it is possible that study fields attract students with different skillsets, the present study does not report disciplinary differences, as participating novice students were not yet exposed to different disciplinary cultures. Students’ mean age was 24.83 (SD = 6.85) and median age 22.00. While this is slightly older than the average starting age, it is worthy to note that Finns typically start in higher education older than in other countries (OECD, 2019). The majority of the students (84%) had completed the general track in the upper secondary school.

Participants completed a computer-based Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA +) that includes an open-ended performance task and a multiple-choice section. The open-ended task, used in the present study, required students to think critically and argue for their response in writing (see Klein et al., 2007; Kleemola et al., 2021). The task at hand was designed to activate argumentative writing skills in participants. Furthermore, it was suitable for assessing argumentative writing in the academic context: participants were required to develop a position by means of leaning on documents that were provided in the task. Thus, the task simulated the reality of academic contexts in that the text should be embedded in the existing research literature (see e.g., Swales, 1990). Performance tasks in general have been found to be motivating for students (Kane et al., 2005; Hyytinen and Toom, 2019; Hyytinen et al., 2021c). The task that was used in the study is confidential, but similar tasks are introduced by Shavelson (2010) and Hyytinen and Toom (2019). In the task, students were asked to take a role of an intern in a city government, where they would have to solve a problem and give a report concerning different life expectancies in two cities, Woodby and Brookdale. They were provided five documents, namely a blog post, a podcast transcript, a memorandum, a newspaper article, and an infographic. They were asked to give their response to the problem as an essay, and their proposals for action. They were reminded to discuss any counterarguments, and to support their own claims with information in the available documents. Students had 60 min to complete the task. The length of the responses ranged from one sentence of about 10 words to several pages of about 800 words.

Data Analysis

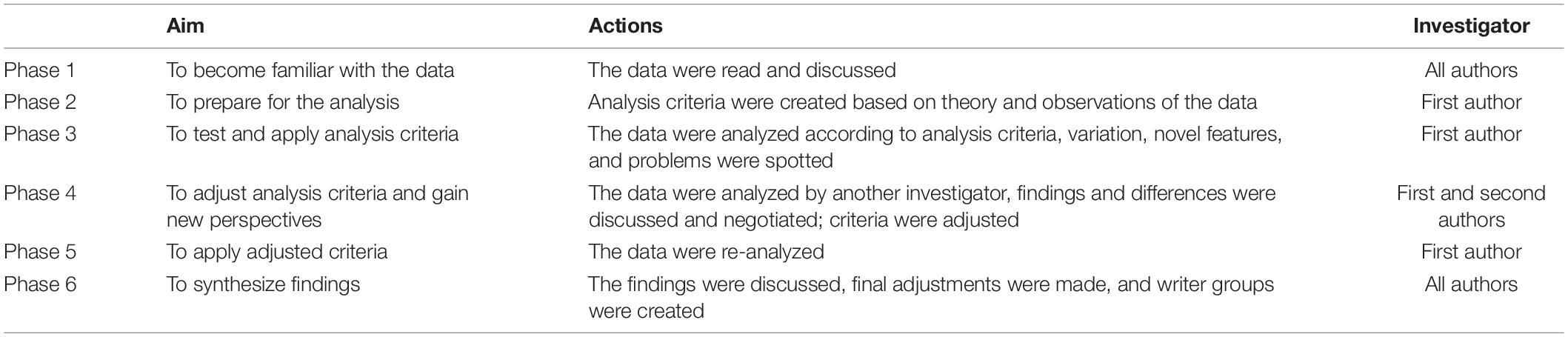

Qualitative content analysis was used to investigate students’ texts. An abductive approach (e.g., Timmermans and Tavory, 2012) was adopted, namely the analysis was theory-driven to start with, but researchers kept an open mind to new discoveries based on the data. Both a group-level approach (RQ1 and RQ2) and an individual-level approach (RQ3) were used to gain a multifaceted view on the topic. The investigation proceeded in six main phases that are presented in Table 1. The process was non-linear in that the authors discussed findings and issues continuously during the process.

In the first phase of the analysis, all three authors became familiar with the data by reading students’ responses. During this phase, general observations were made about the data and were discussed. In the second phase of the analysis, theory-based analysis criteria for identifying the position and alternative positions were created by the first author. The criteria are described in detail below. In phase three, the analysis criteria were implemented by the first author. In addition, data-based, novel features were noted. The episodes with positions and alternative positions were located and their variation was explored and reflected in light of existing research. In phase four, the second author analyzed independently 25% of the essays that were randomly selected. The first and second authors discussed the findings, negotiated their differences, and adjusted analysis criteria where needed and integrated the data-based findings in the criteria. In phase five, the first author re-analyzed the data according to the adjusted criteria from phase four. Finally, in phase six, all authors discussed the findings, and remaining analysis challenges. Additionally, groups of argumentative writers were identified on the basis of the findings.

The analysis criteria were created and adjusted during phases two and four. The criteria aimed for describing the variation in the students’ texts instead of creating exclusive categories. To respond to RQ1, writers’ positions were analyzed, and two types of episodes were traced, namely explicit thesis-statements and other position-indicating expressions (see also Table 2 in “Results” section). The thesis was defined as the response for the main question (Mauranen, 1993). In academic texts, the question is the research question or research aim. In the present study, the task question “what is the reason for the different life expectancies in the two cities?” was considered to be the relevant question. Furthermore, the thesis should be a holistic claim, summarizing the main point of the whole text (Mauranen, 1993). During the analysis in phase three, it was found that some of the essays included a thesis-like statement that responded to a more generic question than the actual task question, having a different orientation (see more in “Results” section). In phase four it was determined that these were included as a thesis, but thesis orientation was to be examined. According to theories and prior studies, the thesis location could be in the introductory section of the text (initial focus), in the conclusion section of the text (final focus) or both (Nestorian order) (Perelman and Olbrechts-Tyteca, 1969; Mauranen, 1993). Thus, the thesis was traced in these sections. Expressions such as “in conclusion” were first looked for, but as Finnish writing tends to include less such metatext (Mauranen, 1993), the content of the sentences was examined more carefully. Consequently, typical expressions were “is caused by,” “significant factors are,” and “the reason behind—is.” A closer analysis of the variation in the thesis-statements revealed that the thesis precision varied, and thus, it was integrated in the analysis criteria in phase four and examined. It was found that some thesis-statements were vague, and some included hedges that are interactional elements implying uncertainty (Hyland, 2005). In philosophical theories, such expressions have been considered to be modal qualifiers (Toulmin, 2003) that assess the degree of probability of the statement, namely how likely they think the statement to be true.

If a thesis could not be found, other position-indicating expressions were traced. Interactional elements (Hyland, 2005) were traced, namely attitude markers and self-mentions that appear without a thesis. Affective, and attitudinal expressions, such as “positive,” “unreliable,” “questionable,” and “cannot be trusted” were traced. In addition, the first-person forms of pronouns “I” and verbs “I recommend” (Finnish verbs have an integrated first-person form which does not require the pronoun) were traced. During the analysis, it was found that in some essays there were explicit claims that could nevertheless not be identified as a holistic thesis. These were recognized as local arguments (Mauranen, 1993; Wolfe, 2011), that indicate a position while not expressing it holistically, in the way that the present study defined the thesis. Local arguments were integrated in the analysis criteria in phase four. Finally, in some essays we found no position-taking, neither explicit thesis nor other position-indicating expressions.

In analyzing alternative positions (RQ2), we traced episodes where the writer showed their awareness on rival explanations to the task question, namely “what else could be the reason behind the different life expectancies, but maybe is not true?” (see also Table 3 in “Results” section). Such episodes show that the writer accepts the possibility of diversity in the positions, while they do not necessarily always express an explicit position against the evidence (Kuhn, 1991). Thus, we traced both rebuttals and expressions of contradictory positions. To trace these episodes, we looked for contrasting expressions such as “however,” and “on the other hand.” Furthermore, we looked for rebuttals, such as “is not significant,” “does not affect,” and “I can’t agree.” Additionally, as mentioned above in thesis-identification, content of the sentences was examined beyond metatext. Structures such as “X says Y, Z says not Y” were noted. During the analysis, variation was detected in the rebuttals, namely in the reasoning, hesitancy, and attitudes. These features were integrated in the analysis criteria in phase four.

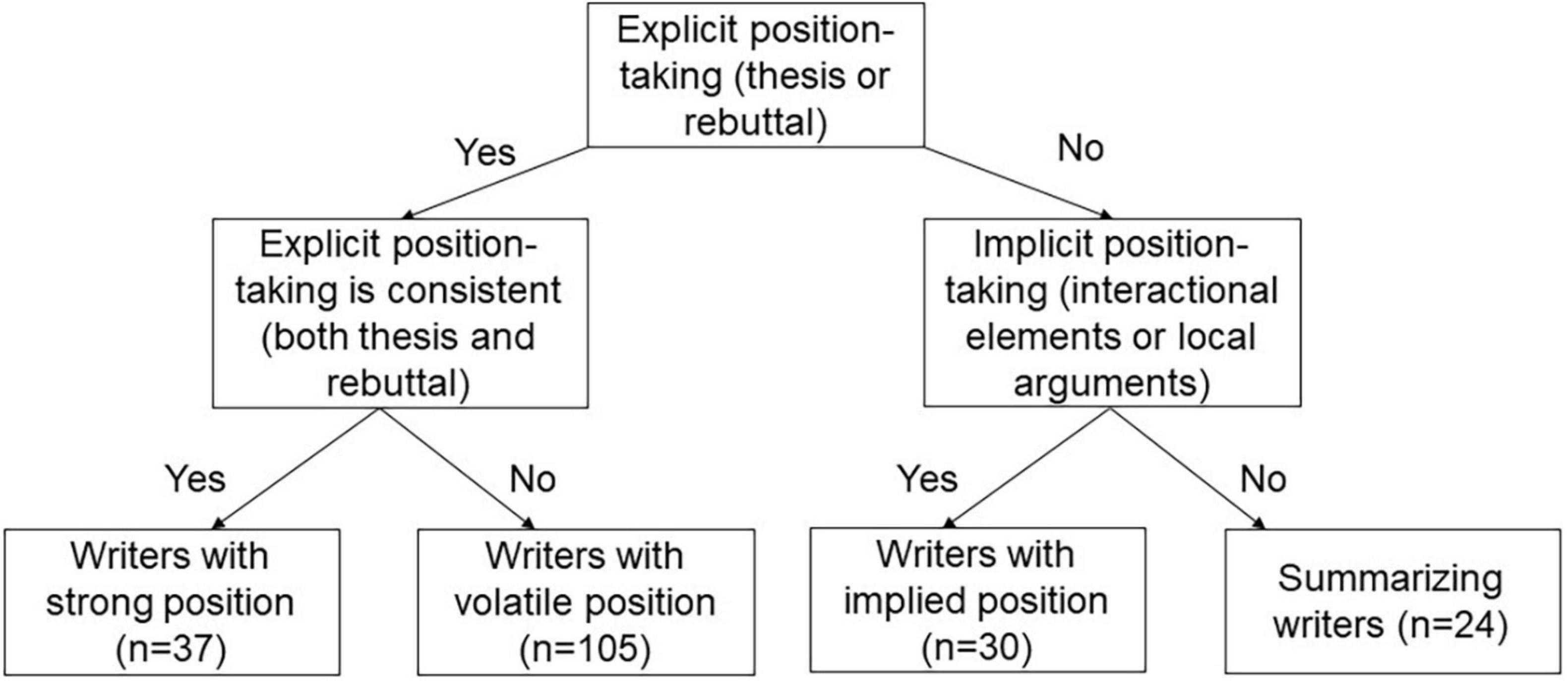

To respond to RQ3, findings of RQ1 and RQ2 were examined carefully. At this point, the variation in the degree of writer’s presence through their position-taking was recognized as the guiding theme. Four groups were created examining the aspects of position-taking, their differences, and similarities. The differences between the groups culminated in explicitness of their position. The process of creating the groups is also presented in the “Results” section (Figure 1).

Investigator triangulation was used in the data analysis (Denzin, 1970). Becoming familiar with the data in the first phase allowed all authors to evaluate findings in light of the entire dataset. While the first author performed the analyses in phases three and five, all authors discussed and evaluated findings and considered challenging features throughout the process. Additionally, in phase four, the independent analysis by the second author and discussions that followed ensured that all authors interpreted the analysis criteria similarly.

The excerpts that are presented in the “Results” section are translations from Finnish to English. Any typos were omitted in translations as they were not relevant to the present study. Some details concerning the content have been altered in order to preserve confidentiality of the task. These alterations do not influence the analysis of the position-taking that is the focus of the present study.

Results

Variation in the Presentations of Writer’s Position

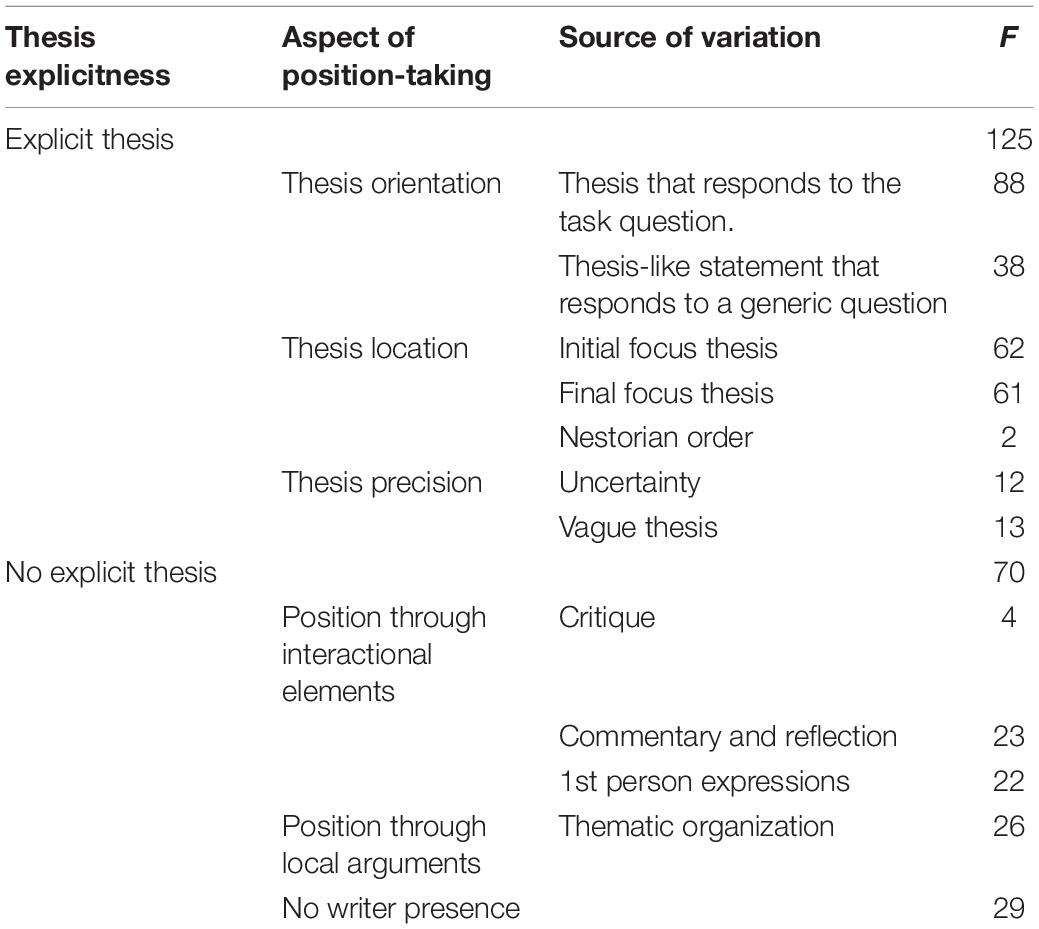

Position-indicating episodes were identified in the essays and variation was analyzed. The sources of variation are summarized in Table 2. An explicit thesis was detected in 125 (64%) essays. The thesis-statements varied in their orientation, location, and precision. An explicit thesis could not be detected in 71 essays (36%). However, in some of these essays, a degree of writer presence and position-taking could be detected, namely interactional elements and local arguments.

Thesis Orientation

We first examined the orientation of the explicit thesis-statements. A thesis that adhered to the original definition, responding to the task question (explanation behind different life expectancies in two cities) was found in 88 essays (45%). A typical thesis is presented in example 1. A typical thesis that was oriented toward the task question explicates that the statement is about differences in the life expectancy in the two cities or about Woodby’s higher life expectancy compared with that of Brookdale. Furthermore, a typical thesis lists the most important factor or factors behind the life expectancy. The thesis is underlined in the examples.

(1) — Factors that influence Woodby’s higher life expectancy are exercise and the level of education. —

However, during the data analysis, it was discovered that some essays had a slightly different orientation. They included a thesis-like statement, making a holistic, summarizing statement based on the evidence, which did not respond to the task question. These thesis-statements (F = 38, 19%) responded to a more generic question of factors that influence life expectancy instead of addressing the differences between the two cities. Writers of these essays would write about the factors that help individuals live longer (example 2), or that shorten the life expectancy.

(2) — In summary, it could be said that the level of education, sleep, exercise, and nutrition are keys to a long life.

These students may have falsely understood the question, or they may have failed to analyze the task materials, as responding to the actual task question required deeper problem-solving across available documents. Furthermore, they may have assumed that this generic question was in fact, what was asked, due to most of the materials addressing it. In further analyses in the present study, both thesis orientations were treated as an explicit thesis.

Thesis Location

Next, we examined the variation in the thesis location. Half of the essays with an explicit thesis (F = 62) were using initial focus strategy, namely the thesis was situated in the introductory section of the essay. These thesis-statements were located either in the very beginning of the essay or after an orientating introduction. Some writers would open their essay by stating the reasons behind different life expectancies (example 3) and proceed by presenting the detailed evidence behind this statement. In contrast, some essays with the initial focus strategy opened with an introductory section where writers would describe general background information about the situation (example 4) or state their objectives of the text. After the introduction, they proceed to their thesis-statement, and follow with the detailed evidence.

(3) It seems that two factors are above the rest behind the higher life expectancy of Woodby: exercise and the level of education. —

(4) In the region of Brookdale-Woodby, the changes in life expectancy and reasons behind it have been followed for a long time. At the moment, there is a lot of discussion about actual reasons why people in the Woodby region live longer than the average. Based on research findings, we also can give Brookdale residents tips on how to increase their life expectancy.

There are many reasons for the long life expectancy in Woodby region. According to research findings, the two most significant differences between residents of Woodby and Brookdale are exercise and the level of education. —

The other half of the essays with an explicit thesis (F = 61) had a final focus strategy, namely the thesis was situated toward the end of the essay, as a conclusion (examples 5 and 6). Such a thesis was mostly preceded with the presentation of evidence that supports the thesis. In some essays, an alternative position was presented after the supporting evidence, but before the thesis. In such cases, writers first listed the evidence that they thought was relevant to their own position and then listed the evidence they rebutted or considered inconsequential to the task question (see in more detail below in section “Variation in Presentations of Alternative Positions”). The thesis-statements with a final focus strategy may have been at the very end of the essay (example 5). However, most often it was followed by the proposals for action (example 6), namely what should the cities and their citizens do about the difference in life expectancies.

(5) — It can be concluded that especially the large amounts of exercise and the high level of education seem to lengthen the life expectancy and are probably contributing to the differences in life expectancy in Woodby and Brookdale.

(6) — In other words, since Woodby residents are getting more exercise and have a higher level of education, they also live longer.

Therefore, I recommend Brookdale residents to live healthier. —

In two essays, a Nestorian order was used, namely the thesis was repeated in the beginning and in the end (example 7). While the thesis was reworded, it was similar in contents in the beginning and in the end. Thesis-statements in the Nestorian order essays were not different from the above descriptions of initial and final focus strategies. However, with only two occurrences, inferences about thesis-statements in Nestorian order need to be taken with caution. Some of the essay text has been omitted from the example to save space.

(7) Woodby has a higher life expectancy compared to its neighboring town of Brookdale. The strongest contributing factors seem to be the residents’ level of education and the amount of exercise they are getting. In the Woodby that has the higher life expectancy, a larger proportion of residents —

[supporting evidence]

[rebuttal of alternative positions]

— Neither seems the sleep they are getting to be significant contributor to the difference in the life expectancy: volume of sleeps seems to be equal in both towns.

Based on the materials, it seems that the longevity of Woodby residents has to do with healthy exercise and the level of education. Therefore, I recommend the Brookdale residents to focus on their exercise in accordance with instructions by the personal trainer Maria. In addition, the educational level of Brookdale residents should be raised.

Thesis Precision

The final aspect of the explicit thesis-statements to be examined was their precision. In most essays, the thesis-statements were plainly stating the conclusion. However, in a few rare cases interactional elements, namely hedges, were found (examples 8 and 9). Hedges are modal expressions that the writer uses to define either their uncertainty about the statement, or the degree of probability, namely how likely they think the statement to be true. Hedges such as probably, perhaps, or likely were identified in the essays. The hedges are outlined in the examples.

(8) — I have been able to define two variables that most likely cause the difference in life expectancies, namely the amount of exercise and the level of education. —

(9) — The higher life expectancy in Woodby is probably mainly caused by the higher educational levels. —

While the hedges often convey uncertainty of the writer, in some cases the thesis was very vague as an example 10 (many reasons). Such statements may have indicated uncertainty as well, but it was not expressed in an explicit way as in the hedges above. The vague thesis-statements complicated distinguishing between an essay with and without a thesis. While the writer of the example 10 is vague in their response, the writer in example 11 does not explicate the factors that are influencing the life expectancy, but instead refers to the rest of the essay, the evidence.

(10) — There are possibly many reasons for the higher average life expectancy in Woodby compared with Brookdale. —

(11) — In my report, I examine factors that point to a longer life expectancy in Woodby, compared with Brookdale residents. —

In such cases the deciding factor was that to be an explicit thesis, the sentence should stand for itself without the rest of the essay. Thus, the example 11 was considered not a thesis while the example 10 was a thesis.

Position Through Interactional Elements

Many essays lacked an explicit thesis. We could not identify a thesis in altogether 70 (36%) essays. However, when we analyzed how these writers related themselves to the available evidence, we found considerable variation. While some essays were strict summaries of available documents, some included various degrees of writer presence.

Even though no thesis could be identified, in a few of these essays, writers took a strong position toward reliability of the materials. For instance, in example 12, the writer questions the trustworthiness of the author of a document.

(12) — In addition, it is notable that Doctor Dave’s identity is open to question and therefore, his information is not reliable as a source. —

Some essays with no thesis included a commentary or reflective sections. In example 13, the writer expresses their hesitancy about the evidence they are referring to by using the word “apparently.” In contrast, in example 14, the writer reflects on their opinion of the facts that they cited, characterizing them as “positive.” These are interactional elements, attitude markers to be precise. Such elements convey the writer’s affective stand toward the facts, thus implying a position.

(13) — Apparently the air quality in Woodby is excellent. —

(14) — The amount of sleep is according to statistics similar in both towns —. This is a very positive observation. —

In several essays—despite having no thesis—the writer used first-person expressions, as in examples 15 and 16. It is worth mentioning that such essays also contained passive statements of facts, so the first-person form did not cover the whole essay. First-person expressions are interactional elements similar to attitude markers. Such self-mentions indicate the writer’s presence in the text. Self-mentions are vaguer in their position-taking than attitude markers. However, it is possible to interpret that the writer agrees with the facts in the first-person sentences.

(15) — I would recommend Brookdale residents to exercise, to get an education and eat healthily. —

(16) — I noticed that all sources I browsed through, always mentioned the same problem. —

Position Through Local Arguments

More than a third of the essays without an explicit thesis had a thematic organization where the writer considered each theme in the materials at a time. For instance, they dealt first with all aspects of exercise that are related to the life expectancy in the two cities, and then moved on to the next theme. In these essays, local arguments were made, but no holistic thesis, summarizing their findings, was present (example 17). The local arguments are underlined.

(17) During the last 20 years, the Brookdale university has followed life expectancies in Woodby and Brookdale. The data shows that the life expectancy in Brookdale is 79 and in Woodby 84. What causes the 5-year difference in the life expectancies?

Research shows that getting less exercise increases the risk for a premature death. In Brookdale, 35% of the residents do not exercise at all. Instead, in Woodby, 31% of residents exercise daily, and 29% of the residents exercise regularly. This surely has a positive influence on the life expectancy in Woodby.

The educational level of residents has also a bearing. According to research, 21% of Brookdale residents has a degree in higher education, compared with 34% of Woodby residents. The difference is not that large, but the higher educational level of Woodby residents very likely influences the life expectancy.

If Brookdale residents want to lengthen their life expectancy, they should exercise more, and get a better education.

In essays with local arguments, the writer clearly takes a position. However, they fail to summarize their observations in a holistic manner. They may consider local arguments to be sufficient as a response to the task, leaving the reader to make a synthesis.

Challenges in Distinguishing Between a Thesis and No Thesis

A complication for the thesis identification was the second part of the task, asking for recommendations for Brookdale residents to improve their life expectancy. A couple of writers had integrated their conclusions and recommendations like in example 18.

(18) — Basing on the information presented above, I recommend Brookdale residents more exercise and going back to school.

These cases were interpreted as no thesis, since the response to the task question was not explicit. However, it is feasible to assume that such statements implicate students’ response and position.

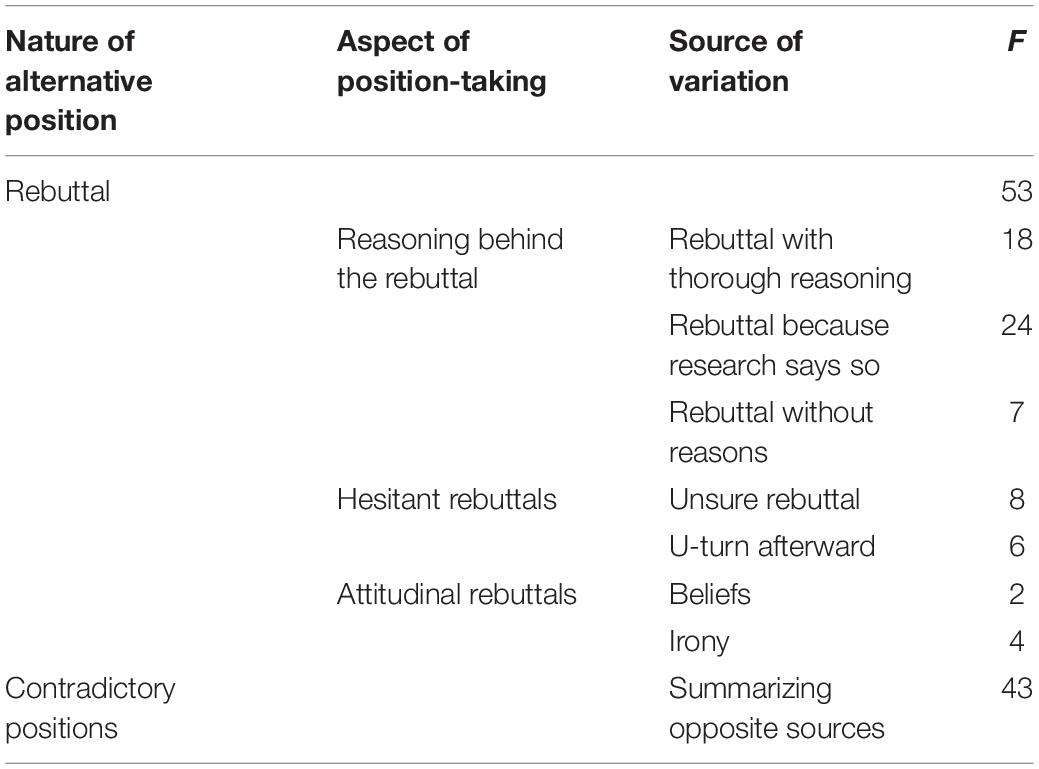

Variation in Presentations of Alternative Positions

In line with the research questions, the variation in ways that writers used to present alternative positions were analyzed. The findings are summarized in Table 3.

Alternative positions were presented in altogether 95 (48%) essays. Two main types of presenting alternative positions, namely rebuttals and contradictory positions, were identified. In rebuttals, the writer explicitly took a position against a piece of evidence within the materials. Of the essays that included alternative positions, 53 (56%) presented a rebuttal. In contrast, the rest of the essays presented contradictory positions. In this type of essay, the writer summarized opposing positions from different sources without taking a personal position toward the issue.

Variation in Rebuttals

In a stereotypical case, a rebuttal included a presentation of the piece of evidence, and an explicit rebuttal, and thorough reasons behind the writer’s choice to dismiss the evidence (example 19).

(19) — The amount of sleep seems to have a bearing on the life expectancy. — Nevertheless, when statistics about Brookdale and Woodby residents are examined, it turns out that there is no significant difference in their sleeping habits and therefore, it is not a sufficient reason to explain the higher life expectancy in Woodby. —

However, not all essays that were identified as presenting a rebuttal were this explicit in their position. Some of the essays with rebuttals simply stated their refutation without expressing reasons behind that position, as an example 20. Often writers considered that “research” was a sufficient reason to rebut a piece of evidence, as an example 21. The rebutting expressions are underlined.

(20) — The clean air in Woodby does not influence life expectancy despite news reports. —

(21) — According to the Woodby Times article, their air quality increases their life expectancy. There is no research proof on this, so I can’t agree with the claim. —

Interestingly, in a few of the essays the writer rebutted a piece of evidence, and afterward they made a U-turn, proceeding to rationalize, why that evidence could still be valid. Such is the case in example 22. This may indicate hesitancy about their position. In a similar vein, some writers were very unsure about their rebuttal, using word the hardly (example 23). This type of expression can be seen as an interactional hedge, even though in the example 22, the hedge is not expressed with a single word.

(22) — It is worth mentioning, that in according to a rumor in Woodby their air quality is rejuvenating. The air quality is undeniably good, but research has not proven that the high life expectancy could be explained by the air. A good-natured belief about a distinctive quality of air does probably not harm the residents. It could even boost their moral and encourage them to take care of themselves, which would increase the life expectancy. —

(23) — The air quality of Woodby hardly has any significant influence on the life expectancy. According to research there is no essential difference, and residents’ claims are based on individual cases instead of scientifically relevant data. —

Another type of interactional rebuttal was presented by some writers who reasoned via attitudes. For some writers their own opinion was a sufficient reason for rebuttal (example 24). In addition, some writers took an ironic position toward the evidence they were rebutting, as did the writer mentioning “magical air” in example 25. While these are not attitude-markers in the sense of linguistic expressions, their aim is similar.

(24) — In Woodby Times there is a claim that the air quality of Woodby could be the reason behind Woodby’s long life expectancy. Of course, it could be beneficial compared with polluted air, but hypothetically I don’t believe it is so much different from Brookdale air. —

(25) — A long life expectancy requires versatile nutrition instead of magical air. —

Contradictory Positions

In contrast to the rebuttals, there was not a lot of variation in the essays with contradictory positions. The lack of variation was probably due to the summarizing nature of these statements. In addition, there was often minimal paraphrasing of the sources.

Typically, in these essays, the writer stated that one of the sources said something that another source opposed (example 26). Sometimes, writers presented more detailed evidence, as an example 27. However, in these cases the wording followed quite closely the original wording in the source documents, indicating problems in paraphrasing (see Hyytinen et al., 2017).

(26) — The amount of sleep increases life expectancy according to Smith’s memorandum, but Doctor Dave says otherwise. Need to investigate more. —

(27) — However, there is contradictory information about Woodby region’s air quality. According to local Environmental Services unit, the air is rich in oxygen. In other towns with similar air quality, residents live longer than average. In their research, Woodby University has not found support on the theory about the air quality as the source for longevity, but they agree that the air is very fresh. —

The distinction between a rebuttal and contradictory evidence was mostly straight-forward, but few cases proved challenging. Above in the example 21, the writer had rebutted the evidence citing research. A different wording changes the interpretation. In example 28, the writer cites a source that rebuts the claim instead of rebutting it themselves.

(28) — An article in Woodby Times contemplates on the Woodby air quality as the secret of long life, but the claim is rebutted by a study on the air. —

Using passive voice could also indicate hesitancy as in examples 22 and 23 above, and thus, analysis of such statements is not easy. In the present study, a strict view on explicit position-taking was adopted.

Types of Argumentative Writers

Based on the analysis of variation in presentations of position and alternative positions in students’ essays, we identified that the degree of writer’s presence in the text through their position-taking was a guiding theme across the findings. Therefore, we identified four kinds of writers. Variation in all detected aspects of position-taking was taken in consideration, however, the explicitness of position-taking was found to be the differentiating feature. The process of creating writer groups, and the differentiating features are presented in Figure 1.

Based on the analysis, we labeled the first group as Writers with strong position. These writers were consistently explicit in their position-taking. In this group, writers took an explicit position toward the evidence, stating an explicit thesis and an explicit rebuttal. Altogether 37 essays represented this group. There was variation in thesis orientation, both types were detected. Likewise, the thesis location varied. In regard to thesis precision, the majority of these essays presented an exact rather than a vague thesis (see example 10 above). Additionally, few of the thesis-statements in this group included hedges, expressing uncertainty. In addition to presenting a thesis, some of these essays also presented local arguments about each theme they discussed. There was more variation in rebuttals in the group. Rebuttal reasoning was varying, some writers presented more comprehensive reasons for their rebuttal than others, and some were more hesitant than others (see examples 19–23). All in all, interactional elements were present in most of the essays in this group. However, interestingly, some writers in this group withheld any other indications of their presence apart from the explicit thesis and the explicit rebuttal.

We labeled the second group as Writers with volatile position. These writers did take an explicit position but were more inconsistent compared to the first group. Writers either presented an explicit thesis or a rebuttal, but not both. Altogether 105 essays represented this group. The majority (F = 89) of these essays included only a thesis, but interestingly, some essays (F = 16) presented a rebuttal but not a thesis. Thesis orientation and thesis location varied in these essays just as in the first group. However, there was a difference in thesis precision. There was more vagueness and uncertainty compared to the first group. Half of those essays that presented only a rebuttal, had local arguments (see example 17), indicating that writers were willing to take a position, but they did not do it in a holistic manner as a thesis. The reasoning behind rebuttals were varied just as in the first group. Interestingly, most of the essays in this group that did not present a rebuttal, did not present any contradictory positions either. The presence of interactional elements was varied in this group.

The third group was labeled as Writers with implied position. Instead of being explicit in their position-taking as did writers in the first and second groups, these writers instead showed their presence in their essays using various ways to imply their position. They did not take an explicit position either in the form of a thesis or a rebuttal. Instead, the essays in this group included some interactional elements that implied their association with the evidence. Altogether 30 essays represented this group. Typically, these essays included critique (example 12), commentary or reflective sections (examples 13–14), and first-person expressions (examples 15–16). Approximately half of these essays had some local arguments (see example 17), implying some position toward the evidence. Additionally, about half of the essays in this group presented some contradictory positions.

Finally, the fourth group was labeled as Summarizing writers. These writers did not show their position toward the evidence in their essays, but they instead summarized the source materials, either by document or by theme. In other words, no thesis, no rebuttal, and no interactional elements were detected in the essays. Altogether 24 essays represented this group. The only indications toward their presence may have been the choice of summarized documents: if they thought some evidence was not relevant for the task question, they omitted it. Nevertheless, some of these essays included contradictory evidence (examples 26–27). This showed that at least some of these writers acknowledged the importance of diverse viewpoints.

Discussion

The present study gives unique insights into novice students basic level argumentative writing that has received little focus in earlier research. Findings show that there is a large variation in novice students’ position-taking. On the bright side, the majority of the students are not entirely clueless about position-taking, but show inclinations to express their viewpoint, which is vital for argumentation. Some guidance by informed teachers might help these students improve their argumentative writing greatly. The findings invite higher education teachers to support novice students in their basic argumentation instead of assuming that they already master all relevant skills.

The findings are in line with earlier studies indicating that some higher education students find aspects of argumentative writing extremely difficult (Petrić, 2007; Laakso et al., 2016; Hyytinen et al., 2021b; Kuhn and Modrek, 2021). Most writers in the present study showed some position-taking regarding their supporting evidence, namely they presented a more or less comprehensive, explicit thesis, or at least made local arguments. Some degree of position-taking was detected in all the writer groups, except for Summarizing writers group. The variation in the degree of position-taking was not surprising. Earlier, it has been suggested that Finnish writers are more implicit in their argumentation, compared with Anglo-American writers (Mauranen, 1993). While being implicit is not always a disadvantage, as Mauranen (1993) points out, writers should be aware of requirements and consequences of their texts. Being implicit, namely letting the reader make conclusions, is an efficient way to activate reflectivity in the reader. However, when the writer needs to be sure that the reader comes to the intended conclusion, as in the present study, an explicit thesis-statement is essential. Student writers should learn to be aware of the requirements of each situation. Furthermore, they should learn to be able to identify each situation in order to fulfill its requirements (see Johns, 2008). It was expected that novice students would find discussing alternative positions challenging (Kuhn, 1991; Andrews, 2009; Wolfe et al., 2009; Kuhn and Modrek, 2021). However, half of the writers did present some version of an alternative position in their essay, indicating that many of them understood the importance of diverse viewpoints. In fact, the essays with contradictory evidence were detected in all four writer groups, while explicit rebuttals were much less frequent, and were detected only in the Writers with strong position group and few of the essays in the Writers with volatile position group. Writers often incorrectly perceive alternative positions to be a shortcoming for an argument (Perkins, 1989; Wolfe and Britt, 2008; Wolfe et al., 2009), and learning how diverse viewpoints strengthen the message would benefit most students in all writer groups. Additionally, understanding similarities in position-taking regarding supporting and contradicting evidence could be helpful.

It is worth pointing out that in the present study, students used both initial focus and final focus strategies in their essays. This was surprising, as earlier studies have shown that Finnish writers have a strong preference on the final focus strategy (Mauranen, 1993; Mikkonen, 2010). It is possible that the format of the task with a direct question influenced this outcome: initial focus strategy may simply have sprung out of an urgency to respond to the task question. An alternative, intriguing explanation to this finding could be that the globalization and exposure to Anglo-American texts with initial focus may have influenced Finns’ rhetoric preferences. However, further research with up-to-date data needs to be conducted in order to draw such conclusions.

Pedagogical Implications

The present findings invite higher education teachers to focus not only on advanced questions of argument validity but also on basic questions concerning how to build argumentation on a textual level, how to identify requirements in each situation, and how to introduce alternative explanations. All higher education teachers, not just writing teachers, should be aware that not all students have learnt basic argumentation in their prior education. Argumentation is difficult, and students need adequate, explicit guidance that focuses on basics (Andrews, 2009; Wingate, 2012; Paldanus, 2020). Fortunately, studies show that even small interventions such as tutorials or exposures to multifaceted texts can help students in their argumentative writing (Wolfe et al., 2009; Kuhn and Modrek, 2021). For instance, analysis of texts with explicit position-taking and summarizing strategies (see Paldanus, 2020), and asking guiding questions about the writer’s position could be helpful (see Wingate, 2012). Such small interventions would nudge the Writers with strong position and Writers with volatile position toward stronger argumentation. However, interventions are not a magic bullet. If students have deficiencies in the basics of composition, as did students in the Summarizing writers group, they require more work and guidance. Furthermore, some of the challenges students have in their position-taking may be due to their self-doubt. Novice students—and even senior students—may feel they are not competent in expressing any position (Ivanič, 1998; Andrews, 2009; Mendoza et al., 2022), and teachers should address such perceptions. Giving more space for discussions and debates would benefit all students in developing their expertise and self-confidence. A vital task of higher education is not only to build expertise but to strengthen the sense of expertise in students.

Co-operation between faculty teachers and writing teachers could be beneficial in integrating learning of argumentation with discipline-specific studies. Supporting students in their position-taking and argumentation has wide-ranging benefits to other generic skills that are needed in higher education. Argumentative skills help in developing students’ critical thinking, academic writing, and overall communicative skills, in addition to supporting knowledge acquisition (Wingate, 2012; Asterhan and Schwarz, 2016; Iordanou et al., 2019; Kuhn, 2019). However, argumentative assignments are not beneficial for learning if students do not receive guidance in the basics of argumentation (Iordanou et al., 2019).

Higher education teachers should be aware that prior education may give little guidance to argumentation and rhetoric (Andrews, 2009). The emphases are culture-specific, and for instance in the Finnish context, the upper secondary education does not focus on such skills (Marttunen and Laurinen, 2004; Mäntynen, 2009; Mikkonen, 2010; Komppa, 2012). The consequence of this shortcoming is that higher education students need even more support in their academic writing, and teachers should not assume that novice students are fully prepared to take on the academic genre.

In the present study, some students did not answer the question prompted in the task, but their response reflected a broader and more generic topic. Earlier research has similar observations. Students may have difficulties in understanding task assignments and what is expected of them (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Macbeth, 2006). Understanding principles of the argumentation is futile if students cannot identify situational requirements (Swales, 1990; Mauranen, 1993; Johns, 2008). Consequently, teachers across disciplines are encouraged to focus on clear and precise directions when giving assignments. Giving students opportunities to discuss assignment requirements can help in facing novel situations (see Johns, 2008).

Methodological Reflections

In the present study, two types of triangulation were used, namely investigator triangulation and theory triangulation (Denzin, 1970), strengthening the findings. In investigator triangulation, multiple researchers participated in the data analysis, ensuring that any alternative interpretations were considered and integrated in the analysis. In theory triangulation, multiple theoretical approaches were integrated, namely pedagogical, linguistic, and philosophical theories. This allowed for a practical approach, to support higher education teachers, and not to limit to one theoretical framework.

In the study design and the implementation of the assessment, some limitations were observed. In future studies, these points need to be addressed. The possible ambiguity of assignments needs to be acknowledged in the future. In the present task, students were prompted to write an essay, which is an ambiguous concept at best (see Johns, 2008), and is often associated with study assignments, or exams. While the intention of the task was for the student to take the role of an intern in a city government, the use of the word “essay” may have led some students to associate the assignment with their studies. Such association may have activated a knowledge-display mode instead of argumentative writing (e.g., Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Petrić, 2007). On the other hand, the task was not a part of students’ real studies, and thus, not assessed as an assignment related to their studies. This may have had influence on students’ motivation and effort they have put to the task. Additionally, students worked under time pressure, having 60 min to complete the task. This may have influenced their performance as they may have run out of time. The time limitation could even discourage students from engaging in complex cognitive processes (Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Paldanus, 2020). In future studies of argumentative writing, students should be allowed to take their time, to obtain a realistic picture of their skills. However, working under time pressure may possibly reveal about which skills students can effortlessly use in a tight situation and which skills come less easily to them. In any case, all participants in the present study had the same time constraint. Finally, it is important to recognize that a study of end products, i.e., finished texts, does not tell us about strategies and processes students use while writing the text or decisions they make (e.g., Bereiter and Scardamalia, 1987; Hyytinen et al., 2021c). For instance, based on our findings, we do not know, if the Summarizing writers made a conscious decision about not expressing their position, or if Writers with strong position stumbled across their thesis-statement instead of goal-oriented writing. In future, combining study of texts with cognitive laboratories allowing investigating cognitive processes during writing, would bring a more thorough understanding of argumentative skills and strategies of novice students.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: The dataset is not readily available, as it may reveal information that comes under the copyright of the test developer. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KK contributed to the theoretical background. KK and HH contributed to the data analysis. All authors contributed to writing, and revision of the manuscript, approved the submitted version, and contributed to the design of the study and data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture (Grant Nos. OKM/44/240/2018 and OKM/280/523/2017).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Council for Aid to Education (CAE) for providing the CLA + International, the participating institutions for administering the assessments and recruiting participants and the Kappas project team for their efforts.

References

Andrews, R. (2015). “Critical thinking and/or argumentation in higher education,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education, eds M. Davies and D. Barnett (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 49–62. doi: 10.1057/9781137378057_3

Andrews, R., Bilbro, R., Mitchell, S., Peake, K., Prior, P., Robinson, A., et al. (2006). Argumentative Skills in First Year Undergraduates: A Pilot Study. York: The Higher Education Academy.

Asterhan, C. S. C., and Schwarz, B. B. (2016). Argumentation for learning: well-trodden paths and unexplored territories. Educ. Psychol. 51, 164–187. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1155458

Barrie, S. C. (2006). Understanding What we mean by the generic attributes of graduates. High. Educ. 51, 215–241. doi: 10.1007/s10734-004-6384-7

Bereiter, C., and Scardamalia, M. (1987). The Psychology of Written Composition. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Biggs, J. (1988). “Approaches to Learning and to Essay Writing,” in Learning Strategies and Learning Styles, ed. R. Schmeck (New York, NY: Plenum Press), 185–228. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-2118-5_8

Breivik, J. (2020). Argumentative patterns in students’ online discussions in an introductory philosophy course: micro-and macrostructures of argumentation as analytic tools. Nord. J. Digit. Lit. 15, 8–23. doi: 10.18261/ISSN.1891-943X-2020-01-02

Denzin, N. (1970). The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (2019). The Ethical Principles of Research with Human Participants and Ethical Review in the Human Sciences in Finland. Helsinki: Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK.

Halpern, D. F. (2014). Thought and Knowledge: An Introduction to Critical Thinking, 5th Edn. London: Psychology Press.

Hetmanek, A., Engelmann, K., Opitz, A., and Fischer, F. (2018). “Beyond Intelligence and Domain Knowledge,” in Scientific Reasoning and Argumentation - The Roles of Domain-specific and Domain-general Knowledge, eds F. Fischer, C. Chinn, K. Engelmann, and J. Osborne (Milton Park: Routledge), 205–226.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: a model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Stud. 7, 173–192. doi: 10.1177/1461445605050365

Hyland, K., and Tse, P. (2004). Metadiscourse in academic writing: a reappraisal. Appl. Linguist. 25, 156–177. doi: 10.1093/applin/25.2.156

Hyytinen, H., Kleemola, K., and Toom, A. (2021a). “Generic skills and their assessment in higher education,” in Assessment of undergraduate students’ generic skills in Finland, eds J. Ursin, H. Hyytinen, and K. Silvennoinen (Jakarta: Ministry of Education and Culture), 14–18.

Hyytinen, H., Löfström, E., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). Challenges in argumentation and paraphrasing among beginning students in educational sciences. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 61, 411–429. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2016.1147072

Hyytinen, H., Siven, M., Salminen, O., and Katajavuori, N. (2021b). Argumentation and processing knowledge in an open-ended task: challenges and accomplishments among pharmacy students. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 18, 37–53. doi: 10.53761/1.18.6.04

Hyytinen, H., and Toom, A. (2019). Developing a performance assessment task in the Finnish higher education context: conceptual and empirical insights. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89, 551–563. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12283

Hyytinen, H., Toom, A., and Shavelson, R. (2019). “Enhancing scientific thinking through the development of critical thinking in higher education,” in Redefining Scientific Thinking for Higher Education, eds M. Murtonen and K. Balloo (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 59–78. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-24215-2_3

Hyytinen, H., Ursin, J., Silvennoinen, K., Kleemola, K., and Toom, A. (2021c). The dynamic relationship between response processes and self-regulation in critical thinking assessments. Stud. Educ. Eval. 71:101090. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101090

Iordanou, K., Kuhn, D., Matos, F., Shi, Y., and Hemberger, L. (2019). Learning by arguing. Learn. Instr. 63, 101–207. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.05.004

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and Identity: The Discoursal Construction of Identity in Academic Writing. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johns, A. M. (2008). Genre awareness for the novice academic student: an ongoing quest. Lang. Teach. 41, 237–252. doi: 10.1017/S0261444807004892

Kakkuri-Knuuttila, M.-L., and Halonen, I. (1998). “Argumentaatioanalyysi ja hyvän argumentin ehdot,” in Argumentti ja Kritiikki. Lukemisen, Keskustelun ja Vakuuttamisen Taidot, ed. M.-L. Kakkuri-Knuuttila (Helsinki: Gaudeamus), 60–113.

Kane, M., Crooks, T., and Cohen, A. (2005). Validating measures of performance. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 18, 5–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1999.tb00010.x

Kleemola, K., and Hyytinen, H. (2019). Exploring the relationship between law students’ prior performance and academic achievement at University. Educ. Sci. 9:236. doi: 10.3390/educsci9030236

Kleemola, K., Hyytinen, H., and Toom, A. (2021). Exploring internal structure of a performance-based critical thinking assessment for new students in higher education. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2021.1946482 [Epub ahead of print].

Klein, S., Benjamin, R., Shavelson, R., and Bolus, R. (2007). The collegiate learning assessment: facts and fantasies. Eval. Rev. 31, 415–439. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07303318

Komppa, J. (2012). Retorisen Rakenteen Teoria Suomi Toisena Kielenä -Ylioppilaskokeen Kirjoitelman Kokonaisrakenteen ja Kappalejaon Tarkastelussa. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

Kuhn, D., Hemberger, L., and Khait, V. (2016b). Dialogic argumentation as a bridge to argumentative thinking and writing. J. Study Educ. Dev. 39, 25–48. doi: 10.1080/02103702.2015.1111608

Kuhn, D., Hemberger, L., and Khait, V. (2016a). Tracing the development of argumentive writing in a discourse-rich context. Writ. Commun. 33, 92–121. doi: 10.1177/0741088315617157

Kuhn, D., and Modrek, A. (2021). Mere exposure to dialogic framing enriches argumentive thinking. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 35, 1349–1355. doi: 10.1002/ACP.3862

Laakso, H., Kiili, C., and Marttunen, M. (2016). Akateemisten tekstitaitojen ohjaus yliopisto-opiskelijoiden tiedonrakentamisen tukena. Kasvatus 47, 139–152.

Lea, M. R., and Street, B. V. (1998). Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Stud. High. Educ. 23, 157–172. doi: 10.1080/03075079812331380364

Lee, J. J., Hitchcock, C., and Elliott Casal, J. (2018). Citation practices of L2 university students in first-year writing: form, function, and stance. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 33, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2018.01.001

Macbeth, K. (2006). Diverse, unforeseen, and quaint difficulties: the sensible responses of novices learning to follow instructions in academic writing. Res. Teach. Engl. 41, 180–207.

Mäntynen, A. (2009). “Lukion tekstitaidoista akateemiseen kirjoittamiseen,” in Tekstien Pyörityksessä. Tekstitaitoja Alakoulusta Yliopistoon, eds M. Harmanen and T. Takala (Helsinki: Äidinkielen opettajain liitto), 153–159.

Marttunen, M. (1994). Assessing argumentation skills among Finnish university students. Learn. Instr. 4, 175–191. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(94)90010-8

Marttunen, M., and Laurinen, L. (2004). Lukiolaisten argumentointitaidot – perusta yhteisölliselle oppimiselle. Kasvatus 35, 159–173. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2019.03.06

Mauranen, A. (1993). Cultural Differences in Academic Rhetoric: A Textlinguistic Study. Bern: Peter Lang.

McCulloch, S. (2012). Citations in search of a purpose: source use and authorial voice in L2 student writing. Int. J. Educ. Integr. 8, 55–69. doi: 10.21913/IJEI.v8i1.784

Mendoza, L., Lehtonen, T., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., and Hyytinen, H. (2022). Exploring first-year university students’ learning journals: conceptions of second language self-concept and self-efficacy for academic writing. System 106:102759. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102759

Mikkonen, I. (2010). “Olen sitä mieltä, että.” Lukiolaisten yleisönosastotekstien rakenne ja argumentointi. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Paldanus, H. (2017). “Historian Esseevastauksen Funktionaalinen Rakenne,” in Kielitietoisuus eriarvoistuvassa yhteiskunnassa - Language awareness in an increasingly unequal society. AFinLAn vuosikirja Suomen soveltavan kielitieteen yhdistys AFinLA. eds S. Latomaa, E. Luukka, & N. Lilja (Helsinki: AFinLAn vuosikirja), 219–238.

Paldanus, H. (2020). Kuka Aloitti Kylmän Sodan? Lukion Historian Aineistopohjaisen esseen Tekstilaji Tiedonalan Tekstitaitojen Näkökulmasta. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Perelman, C., and Olbrechts-Tyteca, L. (1969). The New Rhetoric. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame.

Perkins, D. (1989). “Reasoning as it is and could be: an empirical perspective,” in Thinking Across Cultures: The Third International Conference on Thinking, eds D. Topping, D. Crowell, and V. Kobayashi (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates), 175–194.

Petrić, B. (2007). Rhetorical functions of citations in high- and low-rated master’s theses. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 6, 238–253. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2007.09.002

Roderick, R. (2019). Self-Regulation and rhetorical problem solving: how graduate students adapt to an unfamiliar writing project. Writ. Commun. 36, 410–436. doi: 10.1177/0741088319843511

Shavelson, R. (2010). Measuring College Learning Responsibly: Accountability in a New Era. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis. English in academic and research settings. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Timmermans, S., and Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research. Sociol. Theory 30, 167–186. doi: 10.1177/0735275112457914

Tuononen, T., Parpala, A., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2019). Graduates’ evaluations of usefulness of university education, and early career success–a longitudinal study of the transition to working life. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 44, 581–595. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1524000

Ursin, J., Hyytinen, H., and Silvennoinen, K. (eds) (2021). Assessment of undergraduate students’ generic skills in Finland: Findings of the Kappas! project. Chiyoda: Ministry of Education and Culture.

Virtanen, A., and Tynjälä, P. (2019). Factors explaining the learning of generic skills: a study of university students’ experiences. Teach. High. Educ. 24, 880–894. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2018.1515195

Wingate, U. (2012). ‘Argument!’ helping students understand what essay writing is about. J. Engl. Acad. Purp. 11, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jeap.2011.11.001

Wolfe, C. R. (2011). Argumentation across the curriculum. Writ. Commun. 28, 193–219. doi: 10.1177/0741088311399236

Wolfe, C. R., and Britt, M. A. (2008). The locus of the myside bias in written argumentation. Think. Reason. 14, 1–27. doi: 10.1080/13546780701527674

Wolfe, C. R., Britt, M. A., and Butler, J. A. (2009). Argumentation Schema and the Myside Bias in Written Argumentation. Writ. Commun. 26, 183–209. doi: 10.1177/0741088309333019

Keywords: argumentative writing, higher education, novice students, generic skills, position

Citation: Kleemola K, Hyytinen H and Toom A (2022) The Challenge of Position-Taking in Novice Higher Education Students’ Argumentative Writing. Front. Educ. 7:885987. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.885987

Received: 28 February 2022; Accepted: 21 April 2022;

Published: 09 May 2022.

Edited by:

Rafael Denadai, Plastic and Cleft-Craniofacial Surgery, A&D DermePlastique, BrazilReviewed by:

Jeffery Nokes, Brigham Young University, United StatesSetyo Admoko, Surabaya State University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Kleemola, Hyytinen and Toom. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katri Kleemola, a2F0cmkua2xlZW1vbGFAaGVsc2lua2kuZmk=

Katri Kleemola

Katri Kleemola Heidi Hyytinen

Heidi Hyytinen Auli Toom

Auli Toom