- 1Department of Economics, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan

- 2Department of Information Networking for Innovation and Design, Toyo University, Tokyo, Japan

This study examined the effects of individual-level and group-level trust on willingness to communicate (WTC) in a second language, targeting Japanese university students in a group-language (English) learning setting. Although the effects of group language learning on students’ learning attitudes and the effects of trust on WTC in a second language have been examined extensively, no study has examined group-level factors in a group-language learning setting. A questionnaire survey was conducted thrice per semester. Multilevel analysis found that individual-level trust in group members positively influenced individual-level WTC in English, and group-level trust in group members also positively influenced group-level WTC in English repeatedly through one semester. Moreover, the degree of group-level WTC in English changed after the mid-semester. This study contributes to the literature on group-language learning, and has implications for language education where educators must be mindful not only of each student’s characteristics but also of each group’s characteristics to enhance their performance.

Introduction

Cooperative Learning

The Japanese government has stated that one of the goals of English education should be to instill a positive communicative attitude among students (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT], 2021). Educators should use group and cooperative learning in the classroom (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT], 2021) to make language education effective.

Cooperative learning is an instructional method in which students work together to achieve their learning goals (Zhang, 2010). Cooperation with classmates has positive effects on relationships among students, self-esteem, long-term retention, and comprehension of course material (Zhang, 2010). Furthermore, cooperative learning has a higher level of reasoning and more frequent generation of new ideas (Johnson and Johnson, 2000) as compared to competitive or individualistic learning.

Cooperative learning creates a relaxed classroom environment and increases student motivation (Crandall, 1999). Johnson et al. (1995) suggest that cooperative learning creates a supportive learning setting; it decreases competitiveness and individualism but increases opportunities to cooperate among students. A supportive atmosphere can develop learning if classmates feel positive (Johnson et al., 1995).

Johnson and Johnson (2000) described cooperative learning as a teaching strategy in which students of different levels form groups to work on activities that will eventually enhance their understanding of the subject. Vygotsky (1978) states that more learning occurs in a group when an expert adult helps an adult with less expertise through conversation to achieve the same results.

Cooperative Language Learning

Cooperative learning is used in second language education. Cooperative language learning provides more opportunities for learners to comprehend input and output through interactions between them (Zhang, 2010). Second language learners obtain many opportunities to use the target language through group work in a second-language educational environment (Storch, 1999). Alrayah (2018) conducted a study on university students in Sudan who were studying English, and found a positive correlation between cooperative learning activities and improvement of foreign language learners’ fluency in speaking. Richards (2005) claimed that groups help learners converse more, as a more relaxed environment helps them negotiate with others without pressure. The language development is due to the fact that students felt more relaxed in this learning environment.

Long and Porter (1985) indicated that learners use longer sentences and do not speak any less grammatically in group work than they do in teacher-fronted work. Long et al. (1976), targeting adult learners of English as a foreign language in Mexico, found that the learners produced not only a greater quantity but also a greater variety of speech in group work than in teacher-centered activities. Namaziandost et al. (2019) in their study on Iranian university students found that was a remarkable development in the students’ speaking skills through cooperative learning. Ellis (1999) concluded from previous studies that learner-learner interactions are more effective than teacher-learner interactions in helping learners acquire a second language.

Ghufron and Ermawati (2018) discussed the strengths and weaknesses of cooperative learning in writing classes. They targeted university students in Indonesia studying English as a foreign language, using questionnaires. The results indicated that strengths included raising students’ self-confidence and easing the learning process for the students, and weaknesses included difficulty to manage and requirement of more preparation.

Group Cohesiveness

Group cohesiveness is created for each group through group language learning. Students in a cohesive group have a strong connection with each other as they talk more and share their ideas (Dörnyei and Murphey, 2003). Group cohesiveness also provides opportunities for learning success because it motivates learners to learn a second language more effectively (Clément et al., 1994). Furthermore, students are motivated to help their classmates achieve successful learning through group cohesion because they care about each other (Prichard, 2006).

Ehrman and Dörnyei (1998) noted that this mental bond results from perceived similarity and mutual acceptance. If group members notice common interests among themselves, they will feel closer to each other, and as a result, they become interdependent and gain mutual acceptance. These positive feelings motivate the group and encourage members to become actively involved in group activities (Clément et al., 1994).

Trust in Group Members

What psychological factors does group cohesiveness produce in a group language-learning setting? As stated above, members of a cohesive group are interdependent and mutually accept each other. Acceptance, which means accepting one another’s feelings, values, and problems, has a positive correlation with trust (Roark and Sharah, 1989). Trust is an individual trait, disposition, or cognitive bias toward the goodwill of others (Yamagishi and Yamagishi, 1994). Individuals with high trust are more likely to obtain social benefits than those with low trust because the former risk more and work harder to maximize profitable relationships. Those with low trust limit their opportunities by interacting with smaller networks of people (Yamagishi, 2001). Therefore, group cohesiveness, a strong connection with each member, has a positive correlation with trust (Roark and Sharah, 1989).

Willingness to Communicate

Trust leads to positive attitudes toward language communication. Ito (2021) in his study found a positive correlation between general trust and willingness to communicate (WTC) in a second language (English) among Japanese university students. Therefore, trust in group members leads to WTC in the group. The present study focused on WTC in a second language and trust as the predictors of WTC in a group language-learning setting.

Willingness to communicate in a second language is defined as the readiness to enter discourse at a specific time with a specific person(s) using a second language when free to do so (MacIntyre et al., 1998). Positive correlations between WTC and frequency of communication have been reported (MacIntyre and Charos, 1996; Yashima et al., 2004). Kang (2005) proposed a definition of WTC in group learning: “willingness to participate in small group activities is an individual’s volitional inclination toward actively engaging in the act of communication in a specific situation that can vary according to the interlocutor(s), topic, and conversational context among other potential situational variables.”

Peng and Woodrow (2010) examined the positive effects of classroom environment, such as teacher support, student cohesiveness, and task orientation on WTC in a second language (English), targeting Chinese university students. Dewaele (2019) revealed that foreign language enjoyment and frequency of foreign language use by teachers were the positive predictors toward WTC for English learners from Spain. Using the doubly latent multilevel analysis, which combines multilevel analyses with structural equation models, Khajavy et al. (2018) showed that a positive classroom environment was related to enhancing WTC and enjoyment, and reducing anxiety. At the same time, enjoyment increased WTC at student level and classroom level.

Present Study

Although the effects of group language learning on students’ learning attitudes and the effects of trust on WTC in a second language have been examined extensively, no study has examined group-level factors in a group-language learning setting. In the context of group language work, individuals are nested within groups (Nezlek, 2008). The relationships between the psychological factors are usually calculated based on individual learners as the independent ones. However, in group learning, they share a same learning group environment in each group (Khajavy et al., 2018). In the situations, each group creates an atmosphere that is different from the other groups. In short, in a classroom, individual-level and group-level psychological factors are simultaneously created through group work. Since the assumption of parametric statistic test is the independence of the individual observation, this phenomenon violates the assumption (Hox, 2010). To address this, using the multilevel analysis, it is necessary to examine not only individual-level factors but also group-level factors in a group language learning setting.

Does group-level trust also influence the group-level WTC in the group setting? Khajavy et al. (2018), using multilevel analysis, examined the relationships between enjoyment and WTC at both student level and classroom level, but they did not examine the factors at the learning group level. Based on the above argument, we hypothesized that individual-level trust in group members positively influenced individual-level WTC in English, as in the previous study, and that group-level trust in group members positively influenced group-level WTC in English.

Multilevel analysis was used to examine this hypothesis. This method hierarchically treats individuals and groups (Shimizu, 2014). This analysis can reveal the characteristics of not only individuals but also their groups. For example, it could reveal that high a trust individual can belong to a low trust learning group. This analysis simultaneously estimated each individual’s fixed effects and each group’s random effects (Shimizu, 2014).

The hypothesis of the present study was tested at Level 1 (individual) using the following model:

The hypothesis of the present study was also tested at Level 2 (group) using the following model:

Yij indicates the WTC score for member i in group j. β0j indicates the intercept and β1j the regression coefficient. β0j and β1j were estimated using γ00 and γ10 (fixed effects) and u0j and u1j (random effects). The formulas for the control variables are abbreviated in these models.

Materials and Methods

Pre-survey Method

The pre-survey examined the hypothesis that individual-level trust in group members positively influenced individual-level WTC in English, and group-level trust in group members positively influenced group-level WTC in English, targeting Japanese university students who studied English as a second language.

Participants

The participants were 149 Japanese undergraduate students from a university in Tokyo (118 men, 30 women, 1 other; mean age = 18.99 years, SD = 0.92). They took the one-semester class named, “Listening and Speaking Exercise” with an aim to develop effective and practical English communication skills through a task-based project. They were divided into their respective classes based on their scores on the English ability (CASEC) test. In this class, they were required to suggest a new application to help university students with their group members through one semester.

Students in each class were randomly assigned to fixed groups in the first class, with each group comprising of five students. The members of each group were unchanged for one semester. While analyzing data, the groups having only one student or no student who answered the survey questionnaire were excluded because the multilevel analysis could not analyze them. Finally, there were 52 groups, with 149 participants, and each group had two to five students (the average was 2.86) in the dataset.

Procedure

In the class, after brainstorming, university students’ problems and solutions, participants collected and analyzed data on the problems using questionnaires. They then described the application design and made business and marketing plans. After preparing for the presentation of their group’s new application, they peer-reviewed their final group presentations in the classroom. There were twenty-eight lessons in one semester, half of which were face-to-face lessons, with the others being on-demand lessons.

In every face-to-face lesson, group members chose their roles in group work: discussion leader, speaker, writer, and editor. Assigning a role to each member of the group is effective in achieving successful group work (Dörnyei and Murphey, 2003). Researchers (McCafferty et al., 2006) state that the group would be efficient if every member has something specific to do, such as asking for and giving information, taking notes, and summarizing. Dörnyei and Murphey (2003) suggested that specifying roles for each member improves learning and may decrease the anxiety of group members, as they know what they are expected to do.

Before the participants finished their final presentation (12/15/2020–12/29/2020), they were administered questionnaires with scales assessing WTC in English and trust in group members. The instructors distributed links to web-based questionnaires to the students, and the participants answered through their own PC or smartphone. They were informed on the first page of the questionnaire, which was written in Japanese, that their participation was voluntary and anonymous. The students provided their consent to participate and to use their data.

Questionnaires

Willingness to Communicate in English

Willingness to communicate in English in the present study is the willingness to communicate in English discussions and presentations with group members in a group language learning setting. The original WTC scale was based on a scale published by McCroskey (1992); the Japanese version was developed by Yashima (2002). The scale (twelve items) consisted of four communication contexts (talking in dyads, small groups, large meetings, and in front of an audience) with three types of receivers: strangers, acquaintances, and friends. The present study focused on group learning in the classroom, and the main activities were discussion and presentation. Therefore, the present study used two items: “I am willing to discuss in English with group members,” and “I am willing to present in English to group members” (r = 0.82, p < 0.01). The response options for all the statements ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Trust in Group Members

Six items were used to assess participants’ trust in group members (α = 0.92). The trust scale was based on the scale published by Yamagishi and Yamagishi (1994) and the Japanese version (Yamagishi, 1998) of the same. The items were as follows: “My group members are basically honest,” “My group members will respond in kind when they are trusted by others,” “My group members are trustworthy,” “My group members are trustful of others,” “I am trustful to my group members,” and “My group members are basically good and kind.” The response options for all the statements ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). For individual-level trust, the score was group-mean-centered, which means that the intercept represents the expected value of an observation with a score at the mean for its groups. By subtracting intergroup fluctuations, the regression coefficient was a pure individual estimate free from group effects (Enders and Tofighi, 2007).

Main Survey Methods

The pre-survey confirmed the hypothesis, but the effects of individual-level and group-level trust were marginally significant. The main survey targeted more participants to check whether significant effects could be obtained. The survey was conducted only once. However, the effects can change over one semester. Therefore, the present survey was conducted three times to determine whether the effects had changed. In addition, the present survey examined whether the degrees of individual-level and group-level factors changed through one semester because long-term group work could affect the degrees of individual-level and group-level factors.

Participants

The participants were 284 Japanese undergraduate students from the same university as the pre-survey (229 men, 55 women; mean age = 18.56 years, SD = 0.67). They took the one-semester class named, “Listening and Speaking Exercise” and the aim of this class was to develop effective and practical English communication skills through a task-based project. They were divided into their respective classes based on their scores on the English ability (CASEC) test. Through one semester, they were required to suggest improvements to the existing English website for tourists in Japan; this was called website consulting project.

Students in each class were randomly assigned to fixed groups in the ninth lesson with each group comprising five students. The members of each group were kept unchanged for one semester. While analyzing data, the groups that had only one student or students who did not answer the second or third questionnaire were excluded (the participants answered all three questionnaires). Finally, there were 83 groups, with 284 participants, and each group had two to five students (the average was 4.39) in the dataset. The participants were recruited from all classes.

Procedure

After choosing their project websites for consultation, they analyzed the website’s target audience and user needs and set their business goals. After the midterm group presentation, they described the design, usability, and functionality of their project websites. Finally, they peer-reviewed the final group presentation of the website consultation in the classroom. There were twenty-eight lessons in one semester, half of which were face-to-face lessons, the others being on-demand lessons. In every face-to-face lesson, group members chose their roles in the group work: discussion leader, speaker, writer, and editor.

The participants answered questionnaires with scales assessing WTC in English and trust in group members three times: at the beginning (Lesson 9; 5/10/2021–5/14/2021), middle (Lesson 15; 5/31/2021–6/4/2021), and end (Lesson 25; 7/5/2021–7/9/2021) of the group project. The instructors distributed links to web-based questionnaires to the students, and the participants answered through their own PC or smartphone. They were informed on the first page of the questionnaire, which was written in Japanese, that their participation was voluntary and anonymous. The students provided their consent to participate and to use their data. Actual English proficiency (CASEC), chance of communicating with English speakers, and experience of communicating with English speakers outside school were assessed as control variables.

Questionnaires

Willingness to Communicate in English

The same two items as in the pre-survey were used for WTC in English (r = 0.81, p < 0.01 for 1st; r = 0.82, p < 0.01 for 2nd; r = 0.79, p < 0.01 for 3rd).

Trust in Group Members

The same six items as in the pre-survey were used for trust in group members (α = 0.91 for 1st; α = 0.93 for 2nd; α = 0.94 for 3rd). For individual-level trust, the score was group-mean-centered.

Computerized Assessment System for English Communication

This tool is a computer-based English proficiency test with reading and listening sessions. The highest score is 1,000. All the participants took the test before the semester. The mean was 522.77 and the standard deviation was 84.17 (For the conversion to TOEFL, the mean was 433.67 and the standard deviation was 33.21).

Chance of Communicating With English Speakers

The participants answered the following question: “In daily life, including in the classroom, how often do you talk in English?” The response options were 1 = not at all, 2 = once a month, 3 = once a week, 4 = three times a week, and 5 = every day.

Experience Communicating With English Speakers Outside School

The participants answered the following question: “In the past, how much experience do you have communicating in English with English speakers outside the school (e.g., workplace, shop, park, and street)?” The response options were 1 = not at all, 2 = not much, 3 = sometimes, 4 = usually, and 5 = always.

Results

Pre-survey Result

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of WTC and trust. The WTC (M = 3.20, SD = 1.06) and trust (M = 4.21, SD = 0.76) scores were significantly higher than the midpoint [t(148) = 2.27, p < 0.05; t(145) = 19.28, p < 0.01].

Table 1 also shows the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which indicates how much of the total variance in scores varied between the groups. Between-group variability is partitioned further and represented by the variance components of each random effect. This information can be used to determine how much of the variance within groups and how much of the between-group variance around each parameter is accounted for by Level 1 and Level 2 predictors (Yeo and Neal, 2004). The ICC was 8.9% for WTC in English and 22.5% for trust in group members, thereby justifying the use of Level-2 variables in subsequent analyses (Hox, 2002). The ICC for WTC was not significant. Some researchers suggest that multilevel models are not appropriate when the ICC is low (or 0), because a low ICC means that there is relatively little variance between groups. Even if there is little between-group variance, it cannot be assumed that the relationships between or among these measures do not vary across groups. The assumption is that researchers should use multilevel modeling when they have a multilevel data structure. If there is a meaningful nested hierarchy in the data, multilevel modeling is recommended (Nezlek, 2008).

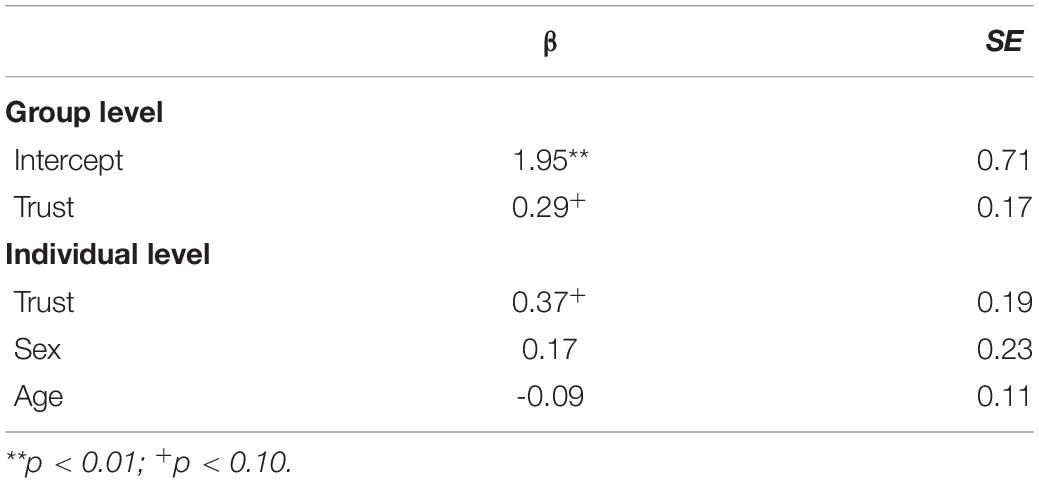

Table 2 shows the effect of trust in group members on WTC in English using a hierarchical linear model. After controlling for sex and age, individual-level trust positively influenced individual-level WTC in English (β = 0.37, p < 0.10). Furthermore, group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English (β = 0.29, p < 0.10). These effects were marginally significant, which means the value that was close to significance (significant tendency). Therefore, students who trusted group members tended to be willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members tended to be willing to discuss and present in English. From these results, the effects of group-level factors were shown in the group language learning setting.

Main-Survey Result

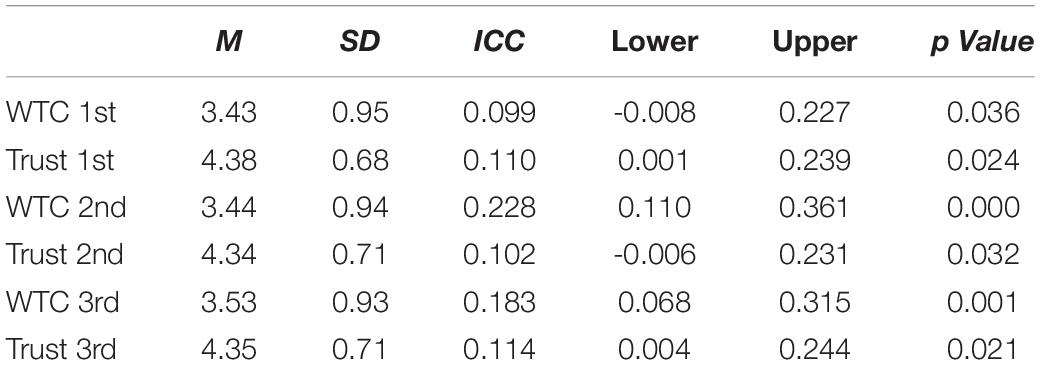

Table 3 shows means and standard deviations of WTC and trust at each survey. The scores of WTC (M = 3.43, SD = 0.95) and trust (M = 4.38, SD = 0.68) were significantly above the midpoint [t(284) = 7.67, p < 0.01; t(284) = 34.40, p < 0.01] for the first survey, WTC (M = 3.44, SD = 0.94) and trust (M = 4.34, SD = 0.71) were significantly above the midpoint [t(285) = 7.92, p < 0.01; t(283) = 31.78, p < 0.01] for the second survey, and WTC (M = 3.53, SD = 0.93) and trust (M = 4.35, SD = 0.71) were significantly above the midpoint [t(286) = 9.55, p < 0.01; t(281) = 32.12, p < 0.01] for the third survey.

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and confidence intervals (95%) for three surveys.

Table 3 also shows the ICC, which indicates how much of the total variance in scores varied between groups. The ICC was 9.9% for WTC in English and 11% for trust in group members for the first survey, 22.8% for WTC in English and 10.2% for trust in group members for the second survey, and 18.3% for WTC in English, and 11.4% for trust in group members for the third survey with all results being significant, thereby justifying the use of Level-2 variables in subsequent analyses (Hox, 2002).

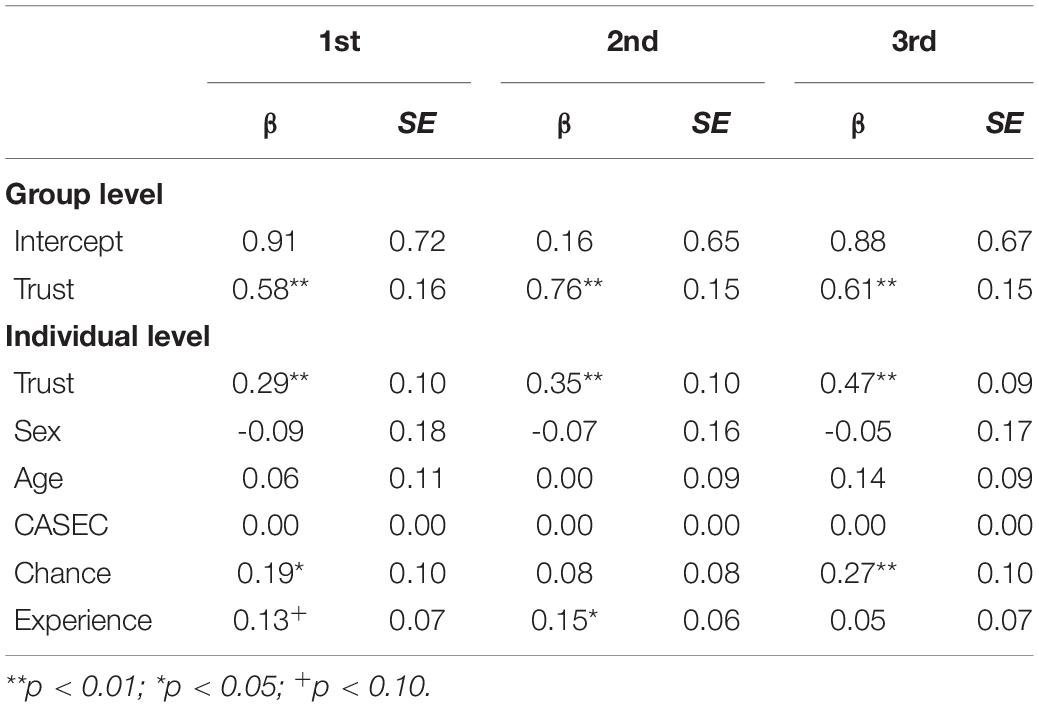

Table 4 shows the effects of trust in group members on WTC in English under a hierarchical linear model for the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd survey. For the 1st survey, after controlling for sex, age, CASEC, chance of communicating with English speakers, and experience of communicating with English speakers outside school, individual-level trust positively influenced WTC in English (β = 0.29, p < 0.01). Furthermore, group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English (β = 0.58, p < 0.01). Therefore, students who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English in the 1st survey.

For the 2nd survey, after controlling for sex, age, CASEC, chance of communicating with English speakers, and experience of communicating with English speakers outside school, individual-level trust positively influenced WTC in English (β = 0.35, p < 0.01). Furthermore, group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English (β = 0.76, p < 0.01). Therefore, students who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English in the 2nd survey.

For the 3rd survey, after controlling for sex, age, CASEC, chance of communicating with English speakers, and experience of communicating with English speakers outside school, individual-level trust positively influenced WTC in English (β = 0.47, p < 0.01). Furthermore, group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English (β = 0.61, p < 0.01). Therefore, students who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English in the 3rd survey. From these results, the effects of group-level factors were shown in the group language learning setting throughout one semester, and these effects were all significant.

We also examined whether the degrees of individual-level and group-level factors changed over one semester. A one-way within-subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effect of timing on individual-level trust among the group members. There was no significant difference in individual-level trust among group members between the three times [F(2, 552) = 0.65, n. s.]. Then, a one-way within-subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effects of timing on group-level trust among group members. There was no significant difference in group-level trust among group members between the three times [F(2, 552) = 2.14, n. s.].

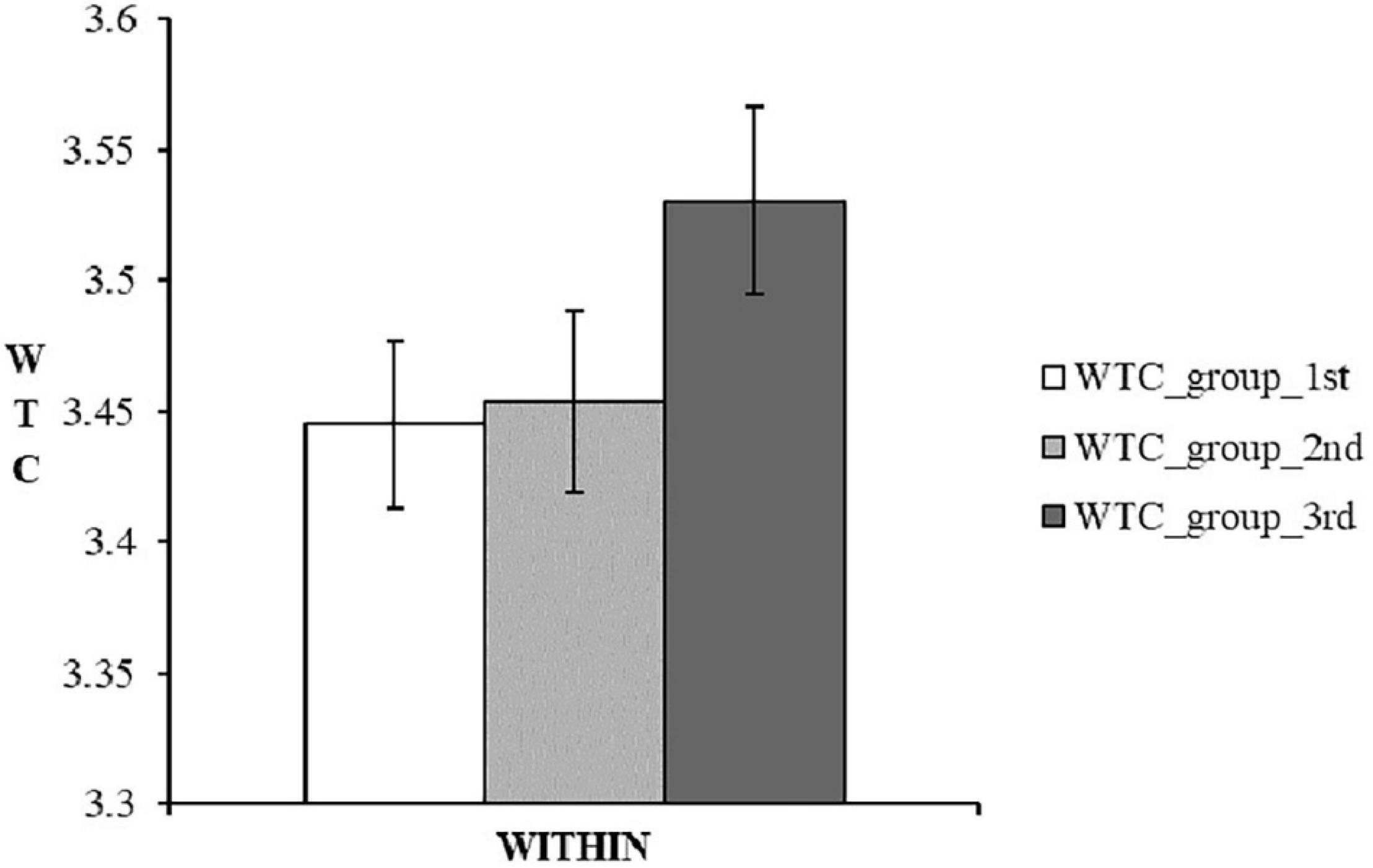

Next, a one-way within-subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effects of timing on individual-level WTC in English. There was no significant difference in the individual-level WTC in English between the three times [F(2, 566) = 2.06, n. s.]. Then, a one-way within-subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare the effects of timing on group-level WTC in English (Figure 1). There was a significant difference in the group-level WTC in English among the three times [F(2, 566) = 5.25, p < 0.01]. The Holm test for multiple comparisons found that the mean value of group-level WTC in English was significantly different between the 1st and 3rd (p < 0.01), and between the 2nd and 3rd (p < 0.01). Therefore, the 3rd group-level WTC in English was the highest at that time. Thus, the degree of group-level factors changed through one semester in the group language learning setting.

Discussion

Discussion on Pre-survey

In the pre-survey, the ICC of trust in group members was significant. A significant ICC of trust in group members means that each group had its own unique trust in group members. Through a group project in the classroom, they suggested a new application. They needed to discuss their ideas, but if they disagreed, they needed to build a consensus on the best idea. Through this process, they made the group cohesive and trusted each other when necessary. Therefore, unique group-level trust is formed. Although the ICC for WTC was not significant, the group project had a multilevel data structure, and multilevel modeling could be used (Nezlek, 2008).

As a result of a hierarchical linear model, students who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English. The effects of group-level factors were demonstrated through a group project in the classroom. Having trust in someone can form strong connections between the two concerned parties. Therefore, higher group-level trust led to higher group-level willingness to discuss and present in English.

Discussion on Main-Survey

For the main survey, the ICC of WTC in English and trust in group members were significant. A significant ICC of trust in group members means that each group had its own unique trust in group members. Through the group project, they suggested an improvement to an existing English website. They needed to discuss their ideas and express their feelings about ideas from other members. Through this process, they made the group cohesive and trusted each other when necessary. Therefore, unique group-level trust was formed. Simultaneously, a unique group-level WTC in English was created, as shown by the significant ICC of WTC in English. Higher group-level willingness was a crucial factor for their grades because not only was individual performance evaluated in the group project but group performance as well. Therefore, a unique group-level WTC in English was formed.

A hierarchical linear model showed that individual-level trust positively influenced individual-level WTC in English. Furthermore, group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English throughout the semester. According to the results, through one semester, students who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English among group members, and groups who trusted group members were willing to discuss and present in English repeatedly. Interestingly, the effect of group-level factors was observed at the beginning of group projects. Immediately after making the group random, the participants formed group-level trust, and the effects of the trust remained until the end of the group projects.

In the classroom, group performance was evaluated for grades and group-level WTC was related to group performance. The students were required to discuss the group project, and each group presented their ideas in front of their classmates. Teachers were evaluating not only individuals’ but also groups’ performance. In short, grades depended not only on individuals but also groups. We could infer the relationships between group-level WTC and group performance because active group discussion and well-cooperated discussion by higher group-level WTC will result in good group performance. Group-level trust continuously influenced group-level WTC throughout one semester. Therefore, group-level trust played a crucial role in enhancing groups’ classroom performance through active discussion and presentation in English. Thus, it is important to examine group-level trust in group-language learning settings.

We also examined whether the degrees of individual-level and group-level factors changed through one semester. There was a significant difference in group-level WTC in English between the three surveys, and 3rd group-level WTC in English was higher than the other timings. The group-level WTC did not change until the middle of the group projects, but after that, the WTC increased. As stated above, in the classroom, group performance was evaluated for their grades, and group-level WTC was related to group performance. In short, they were evaluated not only individually but also as a group in terms of discussion and presentation. Furthermore, they had a final group presentation at the end of the group projects, which comprised a large percentage of their grades. Therefore, they were really motivated to show group-level good performance, which means active group discussion and well-cooperated discussion, and as a result, their group-level WTC in English increased around the 3rd timing.

Group Language Learning

As stated in the Introduction, second language learners obtain many opportunities to use the target language through group work in a second language educational environment (Storch, 1999). However, group language learning has a negative effect. Students perceived group work as a waste of time if they worked with others without gaining any benefits in the classroom. These findings could be the result of working with mixed-ability groupings, where low-ability students asked many questions to clarify doubts (Alfares, 2017). Senior (1997) explored the perceptions of experienced English-language teachers regarding the nature of good English language classes. The findings showed that teachers judged the quality of their classes according to how well students cooperated with each other. They clearly perceived that any class with a positive whole-group atmosphere was good, whereas any class that lacked the spirit of group cohesion was unsatisfactory, even if it was composed of high-achieving students.

The results of the present study suggest that if group-level trust is high in students, group-level WTC in English will also be high. Group-level WTC in English was related to group performance, which was included in their grades. In this situation, even if some students were not motivated to discuss and present in English among their groups, they could obtain higher grades thanks to group performance. However, if the students’ group-level trust was low, group-level WTC in English was also low. Low group-level WTC was related to poor group performance. In this situation, some students who were motivated to discuss and present in English among their groups could not obtain many opportunities to use the target language and get higher grades due to poor group performance. Consequently, their satisfaction was low. Educators need to consider these cases in a group language learning setting.

Trust and Willingness to Communicate in English

Ito (2021) showed a positive correlation between general trust and WTC in a second language (English) among Japanese university students. However, no study has yet examined the effect of group-level trust on group-level WTC in English. The present study targeted Japanese students learning English in a group language learning setting. In this situation, individual students are nested within groups (Nezlek, 2008) and it is appropriate to look at not only individual-level factors, but also group-level factors. Consequently, individual-level trust positively influenced individual-level WTC in English, and group-level trust positively influenced group-level WTC in English. Furthermore, these tendencies were shown repeatedly throughout the semester. In addition, group-level WTC in English increased after the middle of the semester.

Limitation and Future Research

There are some limitations of this study. We assume that if some students motivated to discuss and present in English work with a group having low group-level trust and WTC, their satisfaction would be low. However, the present study did not measure the students’ satisfaction. Future research should focus on examining the effect of the discrepancy between individual -level and group-level factors on satisfaction. Furthermore, the present study measures these psychological factors at the same time. To examine the causal relationships between these factors, we need to conduct a longitudinal study.

Even though we could infer the relationships between group-level WTC and group performance because active group discussion and well-cooperated discussion as groups with high-level WTC will have better group performance, we did not measure the students’ performance. Future studies need to examine the relationships between group-level WTC and group performance. Furthermore, external motivation such as getting higher grades, which are related to good group performance, could influence WTC. Future studies should examine the effect of external motivation.

Conclusion

The present study examined the effects of individual-level and group-level trust on WTC in a second language, targeting Japanese university students in a group-language learning setting. Both individual-level and group-level effects were shown throughout one semester, and the group-level WTC in English changed after the middle of the semester. This study contributes to the literature on group language learning.

This study has implications for language education. Currently, educators use group and cooperative learning in the classroom (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT], 2021) to make language education effective. However, motivated students working in a group with low group-level trust and WTC in English could experience decreased satisfaction. Therefore, in the group language learning setting, educators must be mindful not only of each student’s characteristics but also of each group’s characteristics to enhance their performance.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Committee of the Department of Information Networking for Innovation and Design at Toyo University, Japan. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

TI, MF, and JT-S made substantial contributions to study design, acquisition of data, and interpretation of data, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Toyo University for Open Access Publication Fees.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Associate Professor Jason Byrne for help in conducting the studies.

References

Alfares, N. (2017). Benefits and Difficulties of Learning in Group Work in EFL Classes in Saudi Arabia. Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 247–256. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n7p247

Alrayah, H. (2018). The effectiveness of cooperative learning activities in enhancing EFL learners’ fluency. Engl. Lang. Teach. 11, 21–31. doi: 10.5539/elt.v11n4p21

Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., and Noels, K. A. (1994). Motivation, self-confidence, and group cohesion in the foreign language classroom. Lang. Learn. 44, 417–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01113.x

Crandall, J. (1999). “Cooperative language learning and affective factors,” in Affect in Language Learning, ed. J. Arnold (Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Researching Press), 226–245.

Dewaele, J.-M. (2019). The effect of classroom emotions, attitudes toward English, and teacher behavior on Willingness to Communicate among English foreign language learners. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 38, 523–535. doi: 10.1177/0261927X19864996

Dörnyei, Z., and Murphey, T. (2003). Group Dynamics in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ehrman, M. E., and Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Interpersonal Dynamics in Second Language Education: The Visible and Invisible Classroom. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Enders, C. K., and Tofighi, D. (2007). Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychol. Methods 12, 121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121

Ghufron, M. A., and Ermawati, S. (2018). The strengths and weaknesses of cooperative learning and problem-based learning in EFL writing class: teachers and students’ perspectives. Int. J. Instruct. 11, 657–672. doi: 10.12973/iji.2018.11441a

Hox, J. (2002). Multilevel Analysis Techniques and Applications. Quantitative Methodology Series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Ito, T. (2021). Effects of general trust as a personality trait on willingness to communicate in a second language. Pers. Individ. Differ. 185:111286. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111286

Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, F. P. (2000). Joining Together: Group Theory and Group Skills, 7th Edn. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Holubec, E. J. (1995). Circles of Learning, 4th Edn. Edina, MI: Interaction Book Company.

Kang, S. J. (2005). Dynamic emergence of situational willingness to communicate in a second language. System 33, 277–292. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2004.10.004

Khajavy, G., MacIntyre, P., and Barabadi, E. (2018). Role of the emotions and classroom environment in Willingness to Communicate: applying doubly latent multilevel analysis in second language acquisition research. Stud. Sec. Lang. Acquisit. 40, 605–624. doi: 10.1017/S0272263117000304

Long, M. H., Adams, L., McLean, M., and Castaños, F. (1976). “Doing things with words: Verbal interaction in lockstep and small group classroom situations,” in On TESOL ’76, eds J. Fanselow and R. Crymes (Washington, DC: TESOL), 137–153.

Long, M. H., and Porter, P. A. (1985). Group work, interlanguage talk and second language acquisition. TESOL Q. 19, 207–227. doi: 10.2307/3586827

MacIntyre, P. D., and Charos, C. (1996). Personality, attitudes, and affect as predictors of second language communication. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 15, 3–26. doi: 10.1177/0261927X960151001

MacIntyre, P. D., Clément, R., Dörnyei, Z., and Noels, K. A. (1998). Conceptualizing willingness to communicate in a L2: A situational model of L2 confidence and affiliation. Mod. Lang. J. 82, 545–562. doi: 10.2307/330224

McCafferty, S. G., Jacobs, G. M., and DaSilva Iddings, A. C. (2006). Cooperative Learning and Second Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCroskey, J. C. (1992). Reliability and validity of the willingness to communicate scale. Commun. Q. 40, 16–25. doi: 10.1080/01463379209369817

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology [MEXT] (2021). Curriculum Guideline. Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/en/ (accessed May 16, 2022).

Namaziandost, E., Shatalebi, V., and Nasri, M. (2019). The impact of cooperative learning on developing speaking ability and motivation toward learning English. J. Lang. Educ. 5, 83–101. doi: 10.17323/jle.2019.9809

Nezlek, J. B. (2008). An introduction to multilevel modeling for social and personality psychology. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2, 842–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00059.x

Peng, J. E., and Woodrow, L. (2010). Willingness to communicate in English: A model in the Chinese EFL classroom context. Lang. Learn. 60, 834–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00576.x

Prichard, J. S. (2006). The educational impact of team-skills training: preparing students to work in groups. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 76, 119–140. doi: 10.1348/000709904X24564

Richards, J. C. (2005). Communicative Language Teaching Today. Singapore: SEAMEO Regional Language Centre.

Roark, A. E., and Sharah, H. S. (1989). Factors related to group cohesiveness. Small Group Behav. 20, 62–69. doi: 10.1177/104649648902000105

Senior, R. (1997). Transforming language classes into bonded groups. ELT J. 51, 3–11. doi: 10.1093/elt/51.1.3

Storch, N. (1999). Are two heads better than one? Pair Work and Grammatical Accuracy. System 27, 363–374. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00031-7

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). “Interaction between Learning and Development,” in Mind and Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, eds M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 79–91. doi: 10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4.11

Yamagishi, T. (1998). The Structure of Trust: The Evolutionary Game of Mind and Society. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Yamagishi, T. (2001). “Trust as a form of social intelligence,” in Russell Sage Foundation Series on Trust. Trust in Society, ed. K. S. Cook (New York: Russell Sage Foundation), 121–147.

Yamagishi, T., and Yamagishi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motiv. Emot. 18, 129–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02249397

Yashima, T. (2002). Willingness to communicate in a second language: the Japanese EFL context. Mod. Lang. J. 86, 55–66. doi: 10.1111/1540-4781.00136

Yashima, T., Nishide, L., and Shimizu, K. (2004). The influence of attitudes and affect on willingness to communicate and second languages. Lang. Learn. 54, 119–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00250.x

Yeo, G. B., and Neal, A. (2004). A multilevel analysis of effort, practice, and performance: effects of ability, conscientiousness, and goal orientation. J. Appl. Psychol. 89, 231–247. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.2.231

Keywords: group language learning, trust, willingness to communicate, multilevel analysis, cooperative learning

Citation: Ito T, Furuyabu M and Toews-Shimizu J (2022) The Effects of Individual-Level and Group-Level Trust on Willingness to Communicate in the Group Language Learning. Front. Educ. 7:884388. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.884388

Received: 08 March 2022; Accepted: 02 May 2022;

Published: 26 May 2022.

Edited by:

Ting-Chia Hsu, National Taiwan Normal University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Chien Shu-Yun, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, TaiwanChing Chang, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan

Chin-Yu Chen, National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, Taiwan

Copyright © 2022 Ito, Furuyabu and Toews-Shimizu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Takehiko Ito, aXRvdGFrZWhpa29AaG9zZWkuYWMuanA=

Takehiko Ito

Takehiko Ito Mariko Furuyabu2

Mariko Furuyabu2