- 1Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Queensland – Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi Academy of Research, New Delhi, India

- 2Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, New Delhi, India

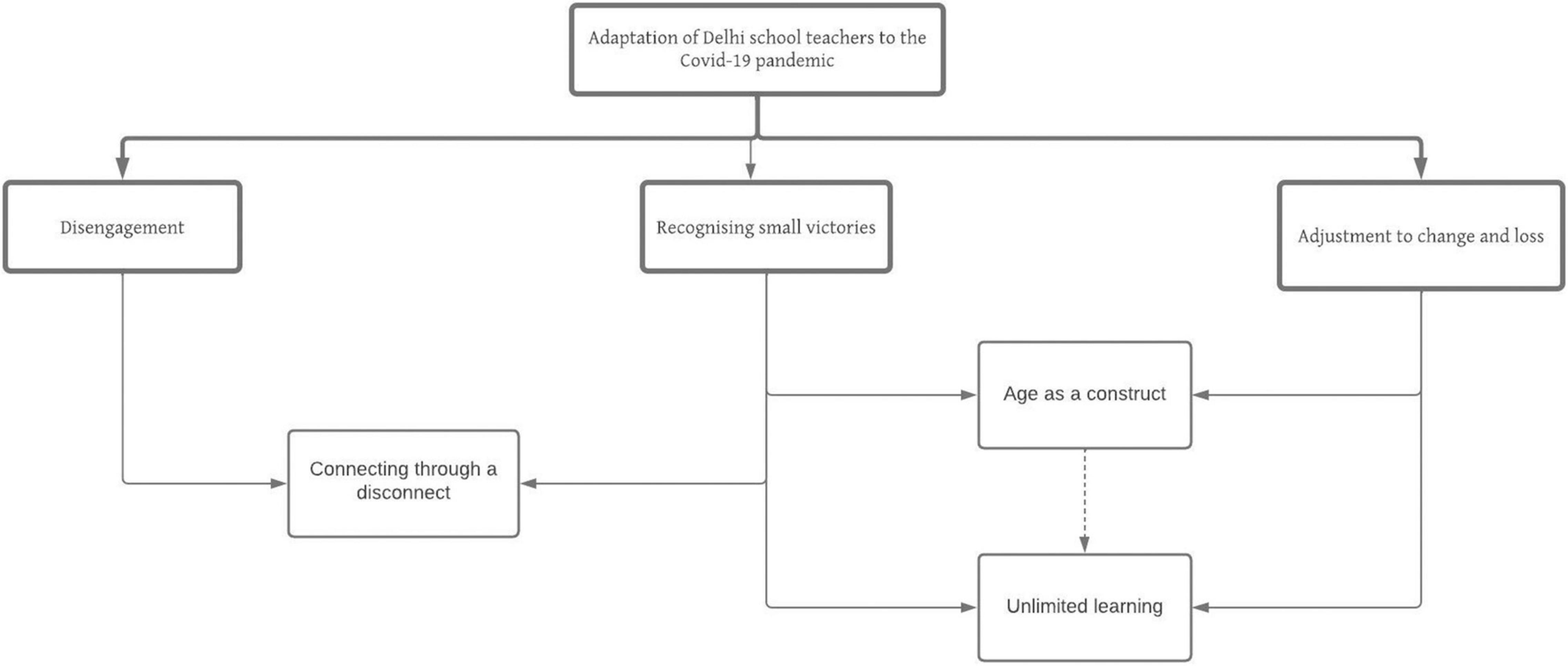

With the sudden onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers across the globe felt the need to respond overnight to unprecedented adversity. Rapid adaptation to unfamiliar modes of teaching was required, leading teachers to face overwhelm on two fronts–adapting to a global pandemic, and teaching in the absence of resources and infrastructure. The lack of a physical classroom and face-to-face interaction also impacted a teachers’ sense of purpose and identity. Shifts in teacher identity affect their motivation, commitment, job satisfaction, and self-image, which collectively influences their resilience. By focusing on the impact of COVID-19 on their teaching experience, this study attempted to understand the resilience of the teaching community while exploring the social and emotional factors that helped them adapt. Using the Life Story Interview method, 20 school teachers in the Delhi National Capital Region were asked to reflect on their teaching experiences during the lockdown to explore their resilience in adapting to a new reality. Reflexive thematic analysis revealed adjustment to change and loss, disengagement, and recognising small victories as themes.

Introduction

According to a World Bank (2019), education worldwide was undergoing a “learning crisis,” as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG4) responsible for ensuring equal and accessible education for all children were short of meeting their goals when the pandemic struck. With the beginning of global lockdowns in 2020, educational institutions were closed immediately to curtail the spread. India underwent a complete lockdown in March 2020, forcing schools to shift to online teaching overnight, with minimal notice and preparation. According to D’Orville (2020), school closures for an extended duration of time cause loss of learning and inexplicably hurt disadvantaged students. He further claims that the negative impact of COVID-19 is likely to be experienced most in countries with established high dropout rates and low learning outcomes. Specific to India, UNESCO (2020) reported that only 37.6 million children have been able to continue education through online means and radio-television programmes, a statistic validated by Kundu (2020) report highlighting that only 8% of Indian households (having children) have access to both the internet and a computer.

Despite the infrastructural roadblocks, educational institutions in India, including schools, adopted teaching platforms such as Zoom, Moodle, Google classrooms, Google meet, etc. The Indian government also launched an initiative, “Bharat Padhe Online” (India Studies Online), to inspire teachers to share innovative educational ideas and content in the public space via educational blogs, YouTube channels and create multiple online educational resources (Bordoloi et al., 2021). The Government of India, specifically the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) in March 2020 (MHRD, 2020), shared information regarding multiple platforms such as Diksha (Department of School Education and Literacy, 2021), SWAYAM, and E-pathshala, wherein resources were available in the form of videos, e-textbooks, and worksheets for both students and teachers. Despite these initiatives, Singh et al. (2020) report that these centralised resources were inaccessible to more than 50% of the student and teacher population due to lack of access to devices and an internet connection, disproportionately more for the rural students. Pratham (2020) report indicates that the most dominant medium to communicate with learners that met the local needs was WhatsApp–an instant messaging application.

Whilst the expectation and intention of the Government of India (GOI) was to bridge the digital gap and make education more accessible, it also came with the implicit expectation that teachers could adjust to the digital transformation and learn new software while meeting the curriculum goals. According to researchers (Kundu and Sonawane, 2020; The Hindu, 2020), many teachers experienced difficulties in gaining proficiency with new technology over a short period, despite training. Although (The Hindu, 2020) sections of teachers are tech-savvy, teaching online full-time is a specialised form of pedagogy which comes with its own struggles, a concern that requires acknowledgement by all stakeholders involved (schools, parents, and students). A recent study by Jain et al. (2021) surveyed the experiences of Delhi schoolteachers during the peak of the COVID lockdown (April–May, 2020), and the data revealed that teachers were spending more of their own time and money to bridge the access gap between students and teachers. According to Jain et al. (2021), while government schoolteachers spent their own money to buy internet data packs for their underprivileged students, private schoolteachers recorded and saved their materials on online platforms so that accessibility is easier for students. Government schoolteachers were able to spend their own money since various state governments-initiated welfare schemes to financially secure these teachers. The difference between government and private schoolteachers is necessary to highlight since welfare schemes initiated by the government have overlooked private unaided schools wherein the teachers have faced severe financial concerns due to lack of salary from their employers, as well as benefits from the government (Alam and Tiwari, 2021). In the same report one can note that such a practice is not restricted to India alone. Countries such as Canada, Pakistan, Panama, and Ireland have not included private schools in their policies while making additional funds available. In Indonesia, however, private schools which taught marginalised and remote communities had access to government grants (Alam and Tiwari, 2021). These practices are stressful for teachers and impact their relationships with their work, employers, and with other essential stakeholders.

The teaching profession involves more than pedagogy; it includes the relationship with parents and colleagues (Hargreaves, 2001) and provides purpose and a sense of commitment (Veldman et al., 2013), all of which contribute to teacher identity. According to Kim and Asbury (2020), teachers have experienced difficult shifts in their professional lives since March 2020 and gaining insights about their experience and their engagement with stakeholders would allow us to understand how teacher identity was impacted.

Social identity may be defined as the sense of self that individuals derive from their connection and identification to social groups of importance, such as professional groups, friends, and family (Tajfel, 1978; Tajfel and Turner, 1979). A key characteristic of this collective sense of identity is the propensity to define oneself in terms of “we” as opposed to “I.” According to Benwell and Stokoe (2006, p. 25), collective identity involves a deep awareness of the group membership and an “emotional attachment to this belonging.”

According to Kim and Asbury (2020), during a crisis such as COVID-19, social identity acted as a source of support and was found to positively impact teachers, as they drew a sense of shared identity. This was particularly useful given that a work from home (WFH) setting diluted the sense of belongingness and association–but having a shared identity for a professional group (such as teachers) assisted in feeling supported and unified in a global crisis such as this pandemic. Drury (2018) highlighted that having a shared identity in crisis situations leads to increased support from peers/colleagues, which increases one’s wellbeing and sense of efficacy. Drury (2012) argues that having a shared social identity owing to professional group membership can enhance one’s survival, coping and wellbeing–thereby increasing their experience of collective resilience (Drury et al., 2009).

When individuals are removed from their workplace surroundings, professional identity is impacted. It gets more prominently highlighted in the teaching profession–which flourishes in a physical classroom requiring face-to-face interaction. In times such as the COVID-19 pandemic, it is crucial to understand how the sense of shared identity is impacted in the absence of a physical space encouraging closeness. According to Beauchamp and Thomas (2009), teacher identity is a construct that lacks a clear definition or theoretical basis. Hanna et al. (2019)’s review on teacher identity measures states that six components drive a teacher identity–task perception (an individual’s understanding of their task as a teacher), commitment (to their profession), self-image (the way they view themselves as a teacher), job satisfaction (an individual’s sense of satisfaction with their job), motivation (the reason individuals chose the teaching profession), and self-efficacy (the belief in oneself on their ability to complete activities). According to Day et al. (2007), rapid changes can cause imbalance, leading a teacher to lose motivation, and sincere individual effort would be required to counter the imbalance. Day et al.’s (2007) seminal paper proposes that teacher identity is essentially an amalgamation of three types of identities–situated identity (a teacher’s relationship with others in a school context), professional identity (social trends and policies), and their personal identity (driven by their surroundings outside of a school context). A teacher’s commitment and resilience are driven by the above-stated identities being in balance. In extension to teacher identity, Day (2018) specified the nature of teaching to extend beyond pedagogical and knowledge-based transactions. He also suggests that teaching often requires teachers to create a capacity for professional empathy, which is different from “empathy,” such that it needs a follow-up/intervention by the teachers to ensure sustained learning/emotional growth. In the last 2 years, COVID-19 has provided an inconsistent and unstable work environment with the multiple lockdowns and reopening(s) and the constant threat of a new variant which has tested a teacher’s motivation, commitment, and resilience. Identity and resilience are interlinked because a teacher’s professional empathy, agency, and efficacy tap into their emotional reserve, and the heightened demands over the last 2 years of COVID-19 undoubtedly impacted their capacity for resilience.

It is important to define resilience to understand the impact on teacher identity and resilience. To begin with, Masten (2018) defined resilience in a systems context as the capacity to adapt to challenges that successfully impede the functioning, development, or survival of a system. In extension, Norris et al. (2008) characterised resilience as a process that links a set of adaptive responses that encourage adaptation and functioning after an imbalance. More specifically, to define teacher resilience, Mansfield et al. (2016) highlighted that resilient teachers are those “having the capacity to thrive in difficult circumstances” (p. 78). Beltman (2015) also characterised teacher resilience as a capacity and notably included dimensions of sourcing personal and social–contextual resources to overcome challenges and experience enthusiasm, commitment, satisfaction, and professional growth. This is an important factor in this study since COVID-19 has led to heightened feelings of disengagement and burnout. According to Chen and Bonanno (2020), flexibility, as opposed to a set of strategies optimising personal and contextual resources, is needed to counter the impact of COVID-19. Bonanno and Burton (2013) highlight that flexibility entails regular monitoring of the efficacy of one’s strategies, re-assessing their utility with changing scenarios and modifying them as the situation demands. Through this study, the authors wish to map how teachers in Delhi NCR adapted and modified their coping strategies depending on their external contexts.

Finally, the importance of relational resilience cannot be disregarded. Day et al. (2007) note the importance of supportive relationships with colleagues in education literature while highlighting its protective role in maintaining teachers’ resilience and motivation levels. Relational resilience is developed through a network of relationships between teachers, students, and teachers and teacher–leaders who are strong and trusting in nature. These are important for empowerment and support and are at the core of the resilience process (Day and Gu, 2014; Gu, 2014). According to Ebersöhn (2012), communities experiencing stress over an extended time experience and respond to it collectively, making resilience a collective response. This has also been reiterated by Gu and Li (2013), who defined resilience as a process which “is the culmination of collective and collaborative endeavours” (p. 300). In extension, if resilience is deemed a collective response, schools and their leadership become responsible for supporting teachers and ensuring professional affiliations and shared resources are available to them to sustain their efforts to maintain balance.

Therefore, this research attempted to explore the following objectives:

• Examine the experiences of Delhi school teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

• Understand how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their teacher identity.

• Understand how they adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic and defined their resilience process.

Methodology and Methods

Research Context

This study aimed to understand the life experiences of teachers teaching during COVID-19 in the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR). Depending on their access to infrastructure and resources, their adaptation to under-utilised methods of teaching such as Zoom, Moodle, or Google classrooms was likely to differ, impacting their teaching experience. For this, in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 teachers teaching across schools. The selected teachers represented schools hosting students from various socio-economic backgrounds. The schools differed in size and were from rural and urban Delhi NCR districts. There were no exclusion criteria based on the teacher’s age and years of teaching experience.

Research Method and Design

This study used Narrative Identity (McAdams, 2001; McAdams and McLean, 2013) to explore teacher experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to McAdams (2001), the theory of narrative identity posits that individuals, based on their episodic memory, develop a dynamic life story which helps provide their life with a sense of purpose. The participants were asked to share their life experiences during the pandemic to understand how they explained their sense of professional and personal identity.

To explore their life experiences, Section B of the Life Story Interview (LSI; McAdams, 2008) was studied. Kim and Asbury (2020) adapted the LSI specific to the teaching population and centred the interview around three scenes: a low point, a turning point, and a high point in a teacher’s experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to McAdams (2008), a key scene would be a moment that is recounted for reasons such as being meaningful, intense, or memorable. According to the life story interview, a high point can be described as a moment that stands out for bringing joy, happiness, and exhilaration every time it is recounted. The respondents are encouraged to highlight the details of the high point scene in an elaborate manner and how it made them feel as a person. A low point, on the other hand, are moments that brought unpleasant feelings for the respondents, such as immense sadness, grief and feelings of overwhelm. Again, the respondents were encouraged to elaborate on the reasons why the episode counted as a low point and how it impacted their self-image. Lastly, according to McAdams (2008), a turning point would be certain moments that caused a shift in one’s perception and caused an important change in the respondent’s life. The teachers were encouraged to elaborate on key incidents that described each of these points in great detail to understand the meaning embedded in their narrative experience. This adapted semi-structured interview is attached in the Appendix.

Participants

Interviews were conducted with 20 teachers teaching across grades ranging from kindergarten to grade 12. An invitation to participate in the research was shared with teachers in the schoolteacher’s WhatsApp groups, on social media platforms such as Instagram, and through snowball sampling techniques. Given that the snowball technique is a non-probabilistic method, this study attempted to collect data from a heterogeneous sample. The interviewees’ age ranged from 23 to 61 years, while their teaching experience ranged from 1 to 29 years. Out of the 20 teachers, 30% of the interviewed teachers were male (n = 6), while the remaining 70% (n = 14) were female. The interviewees taught students from varied socio-economic backgrounds: 9 teachers belonged to schools teaching students from lower-income backgrounds, 6 from middle-income groups, and 4 from higher-income groups. 12 teachers taught senior school, while 4 teachers taught primary school and middle school, respectively.

The interviews were conducted over audio calls, given the requirements of social distancing. Approval for this study was obtained from the 11-member Institute Ehics Committee (IEC) of the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi under ethics application number P-082 in August 2021. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed of the scope of the research, and verbal consent was recorded on an audio recorder, while the written consent was shared over the first author’s email. Interviews were conducted between December 2020 to February 2021. The teachers were encouraged to reflect on and share their teaching experiences from April 2020 to November 2020. The interviews lasted an average of 30 min.

Analysis

The responses from the Life Story Interviews were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019). The analysis was done inductively, and it was felt pertinent by the researchers to describe the lived experiences rather than ascribe meaning to them. The researchers generated detailed descriptive analysis themes that were supported by excerpts from the data.

Results

Theme 1: Disengagement

The first theme highlights the feeling of disconnect teachers experienced with their job roles, social surroundings, and family. The abrupt and overwhelming change in their lives caused an imbalance in their professional and personal identities, and the interviews highlight the struggles they faced in restoring normalcy.

In the beginning, while adjusting to the concept of work from home (WFH), teachers struggled to find physical and mental space to separate their familial and work responsibilities. An interesting finding remains that most female teachers acknowledged the difficulty in balancing work and life as compared to their male counterparts (“I barely get time to even speak to my husband or my daughter. It’s just that I just keep the food ready, prepared for them and then I am off, like, the whole day with my schoolwork.”). Since the pandemic has been a struggle for all stakeholders, including parents, some teachers noticed the discomfort of having a parent actively involved in the classroom (“why are parents poking their nose so much into our classes…all the teachers are quite disturbed, because when we are giving our 200%, leaving our family, doing nothing for them (family). We are just doing it for the children, their children and doing it for their benefit.”). It is essential to highlight that while the teachers understood the reasons behind the parent’s involvement, it was challenging to translate this insight into behaviour, given how intrusive it felt as opposed to their experience of a physical classroom.

As Hanna et al.’s (2019) review highlights, a teacher’s identity is driven by their task perception, commitment, self-image, job satisfaction, motivation, and self-efficacy. Almost all teachers acknowledge the impact of COVID-19 on their feelings of adequacy, their commitment to teaching, and experiences of hurt and despair. Given the incidences of zoom bombing, explicit songs being played during classes, or even ghosting their teacher (absenting oneself from the class and then ignoring the teacher), teachers have been vocal about the impact of these incidents on their self-esteem, their commitment to work, and how they much pride they took in their work (“one day I told to the students that an important topic will be discussed on a particular date. I sent a link to the students to join the class, I was prepared to take the class but only four students joined my google class…. I was so embarrassed and angry. It really hurt”).

Specifically, regarding self-image, many teachers highlighted the struggles of not having an engaged classroom as a low point in their professional journey during the pandemic (“huge part of my challenge in the first month itself was that the children were unfazed by the class, I felt terrible. I hated doing it, you know?”). Although most teachers noted this struggle, teachers with an experience of over 15 years were the first to highlight the lack of an engaged classroom as a low point. Although resilience and adaptation entail using personal and professional resources to adjust to a situation, teachers mentioned how an intellectual awareness of their self-efficacy did not lessen their guilt regarding a “bad day” (“I like doing things particularly well and it was terrible that day…I just had a lot of guilt and even though I knew that not all of it was in my control, I have not been able to make peace with it…I don’t know how to cut myself slack. I felt helpless, what can I do if the student is not speaking. They cheat, they don’t pay attention. It’s been a low point in teaching”).

However, this pandemic also presented an opportunity for the teachers to bring more closeness and trust to the student-teacher relationship. The narratives of a few teachers indicate that getting a glimpse into a student’s home life has increased their sense of compassion and made them more sensitive to a student’s cause (“earlier in school, we used to think they have a bad attitude. Now when they switch on the camera, I can see that in one room–they are studying–the father is lying down on the bed behind. So now empathy…It has increased. Now teachers think maybe the child was telling the truth, we are not so stern now. They are not lying, they genuinely have a problem at home”).

Given that teaching is an innately caring profession (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayim, 2020), it was not surprising to note that some teachers narrated pushing their professional boundaries to make themselves more accessible to their students. Government schoolteachers in this study brought data packs for their students to ensure uninterrupted access to classes, sent worksheets to students via post to students who had migrated to their villages, and kept their lines of communication open beyond school hours (“Now we’ve become familiar to their home situation. Earlier, in school–we would not know so much. Now I tell the child–whenever you need call me–I will take your call. And when the student gets the phone at night, they call me”).

Theme 2: Recognising Small Victories

As Figure 1 indicates, the second theme is on recognizing small victories. Teacher accounts from these interviews highlighted the inherently optimistic nature of teaching and teachers. Despite the pandemic, teachers across socio-economic backgrounds, ages, and gender had one aim in mind–to adapt to the digital pedagogy and ensure the learning process remains undisturbed while ensuring their students’ physical and mental health.

As highlighted in the previous theme, teacher identity has been closely linked to their motivation and job satisfaction. Despite the setbacks caused by the multiple lockdowns and changing policies at the institute and government levels–teachers kept their motivation and commitment high by finding the silver lining in their experiences (“If I’m able to reach 150 students properly, and they are understanding, it is giving me satisfaction. They are also suffering so hard. But when I see their cheerful faces in my class, and they respond nicely…That gives me very solid satisfaction at the end of the day. That at last in this pandemic, I am doing whatever is there within my strength”). Job satisfaction also increased when teachers could transcend inter-departmental boundaries, which was previously difficult due to infrastructural constraints. It is interesting to note that younger teachers (age < 35 years) were more enthused about the opportunity to collaborate with teachers from other departments (“Collaborating with teachers across departments…I think that made me also open up a lot of channels in my own head and way of thinking and way of working because there have been a lot of new insights for me as a teacher. So I think in that sense, I feel a lot more opened…I think my thinking has broadened somewhere”).

These narratives of finding a shift within were uniformly noted across male and female teachers who expressed having grown as listeners and learners (“my students have changed me…earlier 9–10 months ago, what was happening was that 40 students were listening to you right, but in the turning point, I was listening to my 40 students”). It is important to highlight that teacher narratives have consistently reported the pandemic’s role in letting them experience limitless learning. Interestingly, older teachers recounted this feeling more while illuminating the fact that, professionally, the pandemic let them distinguish between age and experience. They chartered a new learning curve, which construed age as only a construct. (“I’m in the age bracket of fifty plus…some teachers give up thinking we are not going to learn any new thing. I find it very, very interesting that now only, you know, only 8 years are left in my retirement, and I’m still ready to learn new ways of teaching…what I have not learnt in the last 30 years, I have learnt in the past 6 months. Now I am enjoying it. I only struggle with maintaining discipline”).

Lastly, it was humbling to note that teachers from private schools noticed and pointed out the difference in their experiences as teachers during the pandemic. Despite most teachers experiencing personal and professional losses–teachers, particularly from the government and rural districts, experienced more hardship compared to those from private urban sectors. Government schoolteachers were expected to do door-to-door COVID surveys, experienced high student loss due to migration, all while they had to meet their teaching goals, and manage with minimal resources. The acknowledgement of the privilege highlighted how collective resilience could be gained in a community by supporting peers and colleagues in their hardships (“We belong to a group, which has access to resources. Government school teachers have gone beyond their capacity. They’ve done COVID duties and teaching. We are lucky”).

Theme 3: Adjustment to Change and Loss

This theme focused on the immediate and retrospective assessment of their experiences to the COVID-19 pandemic. Throughout the interviews, teachers mentioned feeling like they had been thrown into the “deep end of the pool” in the first few weeks of the pandemic. Many teachers from the private school sectors had expected the national lockdown (which began on March 25, 2020) in India to last for only 21 days and mentioned not realising the impending impact of the change till the end of April 2020. Through the interview, when presented with the opportunity to introspect on their experiences–the journey of adaptation to the change can be mapped linearly.

The feelings at the onset of the pandemic were characterised by overwhelm and confusion. Teachers from government and private schools across urban and rural districts of Delhi experienced this overwhelm and specifically highlighted the role of continuous changes in instructions and the consequent lack of clarity in increasing their feelings of anxiety (“initially it was like scratching…nothing came as a straight road ahead. There would be a U-turn, suddenly left, then right. Overnight topics had to be changed. There was no clear idea”).

To add to the struggles of adapting to uncertain times, the lack of technological familiarity caused this transition to be even more daunting for some teachers. Teachers with experience of over 20–22 years, or those aged 50 years and above, were vocal about their difficulties while transitioning to online teaching (“May–June was such a turmoil(ing) time for us, especially people who are like me…I could not even handle my laptop properly. people like me were having sleepless nights when we were asked to perform, and we were asked to conduct the online classes…at that point of time, we used to work 19 h a day.”).

Having said that, as the teachers mapped their journey from April to October 2020, there was a recognition of the positive changes brought on to their professional lives and attitude owing to the pandemic (“when we were going to school, we were on our toes from 5:00 a.m. till 3:30 p.m. And now, we have all the data available with us. Everything on our screen, and we can prepare everything in advance…We are becoming professional, we are preparing well in advance”). Some teachers highlighted that owing to the digital nature of the pedagogy and research, online teaching had resulted in them becoming “a more organised teacher.”

It was humbling to note that at the end of each interview, the teachers thanked the authors for this interview as it made them realise their ability to gain knowledge irrespective of age, socio-economic background, and life situations. Often, it led them to be more perceptive of their gains and acknowledge the small victories (“As a teacher, I will say, it’s- it’s been a learning experience. And obviously, this is something which is so new…like it’s not something we are used to…So obviously, there was apprehension and uncertainty at the beginning. But…again there was a lot to learn from it. And I think we’re still learning.”).

Discussion

Through the interviews, teachers reflected on their teaching experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and highlighted their low points, high points, and turning points. Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019) of the interviews revealed disengagement, recognising small victories, and adjustment to change and loss as the prevalent themes in the teachers’ narratives. It is important to note, as the teachers provided their “scenes” (low point, high point, and turning point), a glimpse was offered on the curation of their teacher identities and the meaning they derived from their experience.

Through this research, the authors attempted to explore the experiences of the schoolteachers in Delhi NCR while teaching during the pandemic’s peak. Gu and Day (2007) asserted that a lacuna in studying resilience in teachers included researching means of promoting resilience during changing times. To elaborate, it is important as researchers to study teacher attitudes and behaviours during difficult teaching periods to understand and anticipate their coping mechanisms rightly. This qualitative research study was a step forward in exploring teacher experiences during adverse periods in the Indian context. As noted previously, few researchers believe (Masten, 2001; Beltman, 2015) that resilience rises from the resources of the ordinary man and their community. Naidu (2021) proposed that tapping this everyday strength from stakeholders such as students, teachers, families, and communities will play an essential role in sourcing strong and adaptive responses to COVID-19. Findings from this study indicate that for the sound mental health of both students and teachers, they sought support from each other and found meaning in their experiences. In addition, Ruohotie-Lyhty (2018) proposed that teachers will negotiate their identities based on the response from their social environment. Narratives derived in the interviews illustrate the journey traversed by teachers: bargaining in anger initially, negotiating with their realities, and finally accepting and adapting to their circumstances. Many teachers reported a transformation in their behaviour, including experiencing more empathy and trust with their students–suggesting a closeness that was earlier missing. The blurring of the professional and personal physical space softened both teachers and students to the struggles of the other. Day (2018) explains that a good teacher is involved in everyday emotional work with students and follows it up with professional empathy as well. Professional empathy, according to Day (2018), is having the ability to understand the emotional state of the other while also following it with “appropriate interventions by the teacher that provide enhanced learning opportunities for the student” (p. 66). This professional empathy assisted the teachers in ensuring the teaching process retained its caring nature.

The key takeaway from this research includes the need to provide opportunities to upskill teachers with digital pedagogy. In her study, Dhawan (2020) noted that most teachers struggled with live lectures, installations, and frequently the focus during classes became integration with the digital technology as opposed to teaching (Bhaumik and Priyadarshini, 2021). Many of the teachers in this study outlined similar concerns at the beginning of the pandemic. According to Naidu (2021), teachers have to reskill themselves for long-term sustenance against adverse situations, and institutions need to re-engineer their policies and teaching operations. Although open schooling and higher education have been a part of Indian education systems since the 1960s, more focus needs to be directed around the needs of the faculty and students, specifically on the transparency of teacher and student contributions. By developing these areas, more efficient resource utilisation will occur while all stakeholders feel validated regarding their effort.

This current research draws its strength from the in-depth exploration of the impact of COVID-19 on teacher identity and resilience, which has been a gap in the literature as most studies have been cross-sectional quantitative studies. The findings from this study have the potential to support teachers in the present situation and beyond in case of similar adverse conditions. Nevertheless, the contribution of this study has to be considered in context of its limitations. This study draws its findings from a limited sample of 20 teachers. The snowball sampling technique, being a non-probabilistic method, limits the scope of the findings, despite studying a phenomenon in a contextualised and in-depth manner. Additionally, the study focuses on teachers from a particular geographical area (Delhi NCR). For future directions, research findings can be more impactful if they include teachers from different states of India, specifically focusing on the rural, semi-rural, and per-urban sectors as well.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research was an attempt to understand the process of meaning making and adaptation to the COVID-19 pandemic by the educational community. Researchers have formerly asserted that a lacuna in studying resilience in teachers included researching means of promoting resilience during changing times. The present study was conducted amongst Delhi school teachers to assess how teachers negotiated their commitment, resilience, and identity in their process of adapting to the global pandemic. The findings indicate that a retrospective lens offered teachers an opportunity to reflect on the teachings from the pandemic. Teachers asserted how online teaching offered an opportunity to perceive age as “just a construct” and enjoy learning new forms of pedagogy and technology despite years of experience. This growth mindset has been known to impact stress appraisal it helped perceive challenges as opportunities for growth as indicated by our findings. Through the present study, the researchers hope to encourage multiple views on the role of resilience in contributing to teacher identity during times of adversities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MR led the data collection, performed the analysis, and interpreted the data. MR and PS conceptualized and designed the study and wrote the initial draft. Both authors revised the subsequent drafts and revised and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alam, A., and Tiwari, P. (2021). Implications of COVID-19 for Low-cost Private Schools. UNICEF. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/media/1581/file/UNICEF_Global_Insight_Implications_covid-19_Low-cost_Private_Schools_2021.pdf (accessed date 28th March, 2022)

Beauchamp, C., and Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: an overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Camb. J. Educ. 39, 175–189. doi: 10.1080/03057640902902252

Beltman, S. (2015). “Teacher professional resilience: Thriving not just surviving,” in Learning to teach in the secondary school, ed. N. Weatherby-Fell (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press), 20–38.

Bhaumik, R., and Priyadarshini, A. (2021). Pandemic Experiences of Distance Education Learners: inherent Resilience and Implications. Asian J. Dist. Educ. 16:2.

Bonanno, G. A., and Burton, C. L. (2013). Regulatory flexibility. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8, 591–612. doi: 10.1177/1745691613504116

Bordoloi, R., Das, P., and Das, K. (2021). Perception towards online/blended learning at the time of Covid-19 pandemic: an academic analytics in the Indian context. Asian Assoc. Open Univ. J. 16, 41–60. doi: 10.1108/AAOUJ-09-2020-0079

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Q. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Chen, S., and Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: a resilience perspective. Psychol. Trauma 12, S51–S54. doi: 10.1037/tra0000685

Day, C. (2018). “Professional Identity Matters: Agency, Emotions, and Resilience,” in Research on Teacher Identity, eds P. Schutz, J. Hong, and D. Cross Francis (Cham: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93836-3_6

Day, C., and Gu, Q. (2014). Resilient teachers, resilient schools: Building and sustaining quality in testing times. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Stobart, G., Kington, A., and Gu, Q. (2007). Teachers Matter: Connecting Work, Lives, and Effectiveness. Maidenhead: Open University Press, doi: 10.1037/e615332007-001

Department of School Education and Literacy (2021). DIKSHA - Government of India. Available online at: https://diksha.gov.in/ (accessed November 16, 2021).

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J. Educ. Technol. Syst. 49, 5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018

D’Orville, H. (2020). COVID-19 causes unprecedented educational disruption: is there a road towards a new normal? Prospects 49, 11–15. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09475-0

Drury, J. (2012). “Collective resilience in mass emergencies and disasters: A social identity model,” in The social cure: Identity, health and well-being, eds J. Jetten, C. Haslam, and S. A. Haslam (Hove: Psychology Press), 195–215.

Drury, J. (2018). The role of social identity processes in mass emergency behaviour: an integrative review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 29:3881. doi: 10.1080/10463283.2018.1471948

Drury, J., Cocking, C., and Reicher, S. (2009). Everyone for themselves? A comparative study of crowd solidarity among emergency survivors. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 487–506. doi: 10.1348/014466608X357893

Ebersöhn, L. (2012). Adding ‘flock’ to ‘fight and flight’: a honeycomb of resilience where supply of relationships meets demand for support. J. Psychol. Afr. 27, 29–42. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2012.10874518

Gu, Q. (2014). The role of relational resilience in teachers’ career-long commitment and effectiveness. Teach. Teach. 20:502e529. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.937961.

Gu, Q., and Day, C. (2007). Teachers resilience: a necessary condition for effectiveness. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23:13021316. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.006

Gu, Q., and Li, Q. (2013). Sustaining resilience in times of change: stories from Chinese teachers. Asia-Pacific J. Teach. Educ. 41, 288–303. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2013.809056

Hanna, F., Oostdam, R., Severiens, S. E., and Zijlstra, B. J. H. (2019). Domains of teacher identity: a review of quantitative measurement instruments. Educ. Res. Rev. 27, 15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2019.01.003

Hargreaves, A. (2001). The emotional geographies of teachers’ relations with colleagues. Internat. J. Educ. Res. 35, 503–527. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(02)00006-X

Jain, S., Lall, M., and Singh, A. (2021). Teachers’ Voices on the Impact of COVID-19 on School Education: are Ed-Tech Companies Really the Panacea? Contemp. Educ. Dial. 18, 58–89. doi: 10.1177/0973184920976433

Kim, L. E., and Asbury, K. (2020). ‘Like a rug had been pulled from under you’: the impact of COVID-19 on teachers in England during the first six weeks of the UK lockdown. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90, 1062–1083. doi: 10.1111/bjep.1238

Kundu (2020). “Indian education can’t go online - only 8% of homes with young members have computer with net link”, The Scroll, 5th May. Available online at: https://scroll.in/article/960939/indian-education-cant-go-online-only-8-of-homes-with-school-children-have-computer-with-net-link (accessed date 5, May 2020).

Kundu, P., and Sonawane, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on School Education in India: What are the Budgetary Implications? - A Policy Brief. Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) and Child Rights and You (CRY). Available online at: https://www.cbgaindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Impact-of-COVID-19-on-School-Education-in-India.pdf (accessed date November 21, 2021)

Lavy, S., and Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 91:103046. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103046

Mansfield, C. F., Beltman, S., Broadley, T., and Weatherby-Fell, N. (2016). Building resilience in teacher education: an evidenced informed framework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 54, 77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: resilience processes in development. Am. Psychol. 56, 227–238. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.227

Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: past, present, and promise. J. Fam. Theory Rev. 10:1231. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12255

McAdams, D. P. (2001). The Psychology of Life Stories. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 5, 100–122. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.100

McAdams, D. P. (2008). The LSI. The Foley Center for the Study of Lives. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University.

McAdams, D. P., and McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative Identity. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 22, 233–238.

MHRD (2020). “Students to continue their learning by making full use of the available digital e- Learning platforms – Shri Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’, pib.gov.in. Available online at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1607521 (accessed 16 December 2021).

Naidu, S. (2021). Building resilience in education systems post-COVID-19. Dist. Educ. 42, 1–4. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2021.1885092

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., and Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. Am. J. Comm. Psychol. 41, 127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Pratham (2020). Annual status of education report (rural) 2020: Wave 1. ASER Centre. Available online at: https://img.asercentre.org/docs/ASER%202021/ASER%202020%20wave%201%20-%20v2/aser2020wave1report_feb1.pdf (accessed 16 December, 2021).

Ruohotie-Lyhty, M. (2018). “Identity-agency in progress: teachers authoring their identities,” in Research on Teacher Identity, eds P. Schutz, J. Hong, and Cross Francis D. (Cham: Springer), 25–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93836-3_3

Singh, K. A., Satyawada, R. S., Goel, T., Sarangapani, P., and Jayendran, N. (2020). Use of EdTech in Indian school education during COVID-19: a reality check. Econ. Polit. Weekly 55, 16–19.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Differentiation Between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. London: Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., and Turner, J. (1979). “An integrative theory of inter-group conflict,” in The Social Psychology of Inter-group Relations, ed. W.-S. Austin (Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole).

The Hindu (2020). Corona Virus: In the time of pandemic classes go online and on air. Available online at: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/in-the-time-of-the-pandemic-classes-go-online-and-on-air/article31264767.ece (Accessed date November 21, 2021)

UNESCO (2020). Global Monitoring of School Closures Caused by COVID-19. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed October 25, 2021).

Veldman, I., van Tartwijk, J., Brekelmans, M., and Wubbels, T. (2013). Job satisfaction and teacher– student relationships across the teaching career: four case studies. Teach. Teach. Educ. 32, 55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.01.005

World Bank (2019). The education crisis: Being in school is not the same as learning. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Appendix

Life Stories Section of Time Interview Schedule

[Adapted from Kim and Asbury (2020) adaptation of Section B LSI; McAdams (2008)]

I would like you to start by telling me the story of your experience so far of being a teacher/headteacher during the coronavirus pandemic. I am going to ask you to describe some scenes from your story, a low point, a high point, and a turning point.

1a. First of all, please can you tell me about the low point in your experience of being a teacher/headteacher during the pandemic so far? Even though this event is likely to be something unpleasant, I would appreciate you telling the story of this low point in as much detail as you can. For example, what happened, when and where, who was involved and what were you thinking and feeling?

1b. Why do you think this particular moment was so bad, and what does it say about you as a teacher/headteacher?

2a. Now, I would like to ask you to describe a scene that you would describe as a high point during your experience of being a teacher/headteacher during the pandemic so far. Please try to describe this high point scene in detail. Think about what happened, when and where, who was involved, and what were you thinking and feeling? Please tell the story of your high point in as much detail as you can.

2b. Why do you think this particular moment was so positive, and what does it say about you as a teacher/headteacher?

3a. The final scene I would like you to describe is a “turning point” scene. In looking back over your experience of the pandemic so far, can you identify a scene that stands out as a “turning point” for you as a teacher/headteacher? If you cannot identify a key turning point, please describe an event from the past month where you went through an important change of some kind. Again, for this event, please describe what happened, when and where, who was involved and what you were thinking and feeling.

3b. As before, please can you say a word or two about what this “turning point” event says about you as a teacher/headteacher or about your teaching career.

Keywords: school teachers, resilience, teacher identity, COVID-19, reflexive thematic

Citation: Ramakrishna M and Singh P (2022) The Way We Teach Now: Exploring Resilience and Teacher Identity in School Teachers During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:882983. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.882983

Received: 24 February 2022; Accepted: 11 April 2022;

Published: 29 April 2022.

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Ana Isabel González Herrera, University of La Laguna, SpainAna Isabel González, University of Extremadura, Spain

Elvira Molina-Fernández, University of Granada, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Ramakrishna and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Madhumita Ramakrishna, TWFkaHVtaXRhLnJhbWFrcmlzaG5hQHVxaWRhci5paXRkLmFjLmlu

Madhumita Ramakrishna

Madhumita Ramakrishna Purnima Singh2

Purnima Singh2