- 1Department of Psychology and Human Development, University College London, London, United Kingdom

- 2Department of Psychological, Behavioural and Social Sciences, Coventry University, Coventry, United Kingdom

University entry represents a period of significant change for students. The extent to which students are able to effectively navigate this change (e.g., via their personal adaptability and social support) will likely impact upon their psychological wellbeing (a finding corroborated by recent studies). However, no study to date has examined these relations among overseas, international students, who represent an increasing proportion of university students in the UK and where the degree of change, novelty, and uncertainty is often exacerbated. In the present study, 325 Chinese international (overseas) students at UK universities, were surveyed for their adaptability and social support as well as their psychological wellbeing outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction, flourishing, and distress). A series of moderated regression analyses revealed that adaptability and social support operate largely as independent predictors of psychological wellbeing (all outcomes). Further, social support was found to moderate the association between adaptability and two of the psychological wellbeing outcomes: life satisfaction and psychological distress. These findings have important implications for educators and researchers, who are seeking to support the transition of international (overseas) students to university and optimize their experience.

Introduction

The number of students going abroad for higher education is on the rise. For example, in the 2019/20 academic year, there were 556,625 non-UK domiciled students studying at UK universities (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2021), representing approximately one fifth of all university students. Most of these students come from China: in the last 5 years alone, the number of students from China has increased by 51,140 (56%), and in the academic year 2019/20, approximately 35% of all non-EU students were from China (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2021). The challenges associated with the transition to higher education are well-documented (see Matheson et al., 2018); but for international, overseas students, who are often crossing borders and cultures to pursue their studies, the magnitude of change is even more significant (e.g., Zhai, 2004), and this may have adverse consequences on their psychological wellbeing and mental health. In the present study, we examine the contribution of adaptability (one's ability to adjust their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in situations of change, novelty, and uncertainty) and social support (one's perception of assistance and support offered by family, friends, and significant others) to university students' psychological wellbeing (Holliman et al., 2021). Indeed, these variables have begun to receive a great deal of attention in discussions of the transition to higher education (see Holliman et al., 2021). To extend and diverge from prior work, our focus is on Chinese international (overseas) students, who are currently studying at UK universities. Furthermore, given the complexities associated with the conceptualization of psychological wellbeing as a construct (see Buzzai et al., 2020, for some related discussion), we incorporate a range of psychological wellbeing outcomes that cover both mental health and mental wellbeing (see Hone et al., 2014), as well as “hedonic” (the affective or “feeling good” dimension) and “eudaimonic” (the psychological functioning or “living well” dimension) aspects (see Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016).

Adaptability and Psychological Wellbeing

Adaptability refers to an individual's ability to manage (i.e., regulate, direct, and adjust) their thoughts, behaviors, and emotions in situations of change, novelty, and uncertainty (Martin et al., 2012, 2013). As a construct, adaptability is firmly rooted in a number of theoretical approaches and traditions, such as self-regulation frameworks (e.g., Zimmerman, 2002; Winne and Hadwin, 2008) and “lifespan theory of control” approaches (Heckhausen et al., 2010), each of which emphasize the importance of self-management systems that monitor, control, and direct one's thoughts and behaviors in order to respond effectively to the demands of the environment (affective adaptability was added later—see Martin et al., 2012, 2013). These adaptive dimensions are important for the maintenance of a positive relationship between oneself and one's (educational) environment.

It follows, that a literature has shown an association between adaptability and psychological wellbeing. For example, longitudinal studies have shown that adaptability is uniquely predictive of psychological wellbeing (positive) and psychological distress (negative) among adolescents (Martin et al., 2013). Moreover, and across three different sample groups, Holliman et al. (2021) found that beyond effects of social support and other demographic variables, adaptability made a significant independent contribution to a range of psychological wellbeing outcomes, including life satisfaction, flourishing, affect, and psychological distress. Additionally, in a study among undergraduate students in China, Zhou and Lin (2016) found that adaptability was a unique predictor of life satisfaction, but also, that social support moderated this relationship (we elaborate on this in a later section). Taken together, there is evidence that adaptability is associated with psychological wellbeing in different countries; although, this research has not explored these relations among international, overseas students.

Social Support and Psychological Wellbeing

Social support is conceptualized as the perception or the actuality that one is cared for and esteemed within a social network of mutual assistance and obligations (Wills, 1991). The concept of social support can be divided into different categories when stressing on action or perception. Enacted support, or received support refers to actual supportive actions such as advice given by providers (Pierce et al., 1996). The perceived social support represents subjective awareness of assistance and support offered by family, friends, and significant others (Zimet et al., 1988; Cauce et al., 1994). Theoretically, Cohen and Wills (1985) argue that social support is important for the receival of positive emotions and a sense of value (thus, a likely predictor of psychological wellbeing). Further, social support may protect one from the adverse impact of stressful events (Cohen and Wills, 1985) and promote the effectiveness of coping strategies and reduce distress (Lakey and Cohen, 2000).

It follows that there is empirical evidence for an association between social support and psychological wellbeing. For example, a converging literature has shown that social support is related to psychological wellbeing among college (e.g., Berndt, 1989) and university samples (e.g., Lee et al., 2011; Yildiz and Karadaş, 2017). Associations between social support and wellbeing outcomes such as self-esteem, positive affect, and life satisfaction, have also been demonstrated among Chinese samples (see Kong et al., 2013). Moreover, Dollete and Phillips (2004) found that social support protected university students from psychological distress and operated as a buffer against stressful circumstances. While few would dispute that social support is important for the psychological wellbeing of university students, few studies have examined these relations among Chinese international (overseas) students, where many social networks may not be as readily available as before: this may be particularly impactful for Chinese students, who come from a collectivist culture where relational (or inter-dependent) self-construal (identity) is more commonplace (see Li et al., 2019).

Adaptability, Social Support, and Psychological Functioning

According to the Conservation of Resources (COR) model, resources can be considered as personal or conditional (or situational) resources, which protect an individual from stress (see Hobfoll, 2001). Adaptability can be considered a personal resource, which, embedded within self-regulation, helps one adjust to new and uncertain environments (Mackey et al., 2013) akin to those studying at an overseas university. Social support can also be viewed as a conditional resource that can help protect and avoid losing important personal resource (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 1990). Perhaps unsurprisingly then, there is empirical evidence of an association between adaptability and social support (e.g., Burns et al., 2018): this may raise questions about the uniqueness of adaptability and social support for predicting psychological wellbeing outcomes. In fact, Zhou and Lin (2016), showed while adaptability and social support were independent predictors of psychological wellbeing (life satisfaction in this case) among a Chinese sample, it was also found that social support moderated (made stronger) the association between adaptability and psychological wellbeing. However, Holliman et al. (2021) failed to replicate this moderating effect among post-16 students, university students, and non-studying adults in the UK. There is therefore a need to further examine the independent (and interaction) effects of adaptability and social support on psychological wellbeing, particularly among international (overseas) students, who may experience a more significant change relative to domestic students.

The Present Study

In sum, there is good reason to suspect that adaptability and social support may be associated with psychological wellbeing among university students; however, there remains a paucity of research examining these relations, and few (if any) attempts to examine these relations among international, overseas students in the UK. This is problematic, given that Chinese students represent a significant proportion of UK university students, and are likely to experience a heightened degree of change, novelty, and uncertainty. There is also a need to examine both independent and moderating effects, given that some research (among Chinese students) has found social support to have a moderating effect (between adaptability and psychological wellbeing: Zhou and Lin, 2016) while other research has not (e.g., Holliman et al., 2021). The present study examines the relationship between adaptability, social support, and psychological wellbeing among Chinese international students at UK universities. The findings may have important implications for educators and researchers, who are seeking to support the transition of international (overseas) students to university and optimize their experience.

Taken together, the current study addressed two major questions:

1. Do adaptability and social support contribute significantly, and independently, to psychological wellbeing outcomes among Chinese international students studying in the UK?

2. Is there an interaction effect between adaptability and social support on psychological wellbeing outcomes among Chinese international students studying in the UK; specifically, a moderating role of social support?

Method

Sample and Procedures

A sample of Chinese international (overseas) students (N = 325) were recruited from several higher education institutions (universities) in the UK. Students were enrolled on various programmes, although approximately half were studying for a psychology-related degree (an anticipated result given the researcher's connections). Most of the sample were female (N = 169; 52%) and in their early twenties (M = 22.59, SD = 2.96). A combination of convenience, snowball, and self-selective sampling approaches were used to recruit participants. The selection criteria were not limited to any particular ability group; all eligible students (Chinese and currently studying in UK higher education institutions) were invited to participate in this research. All students completed an online questionnaire to ascertain demographic details and to measure the core constructs in this study (i.e., adaptability, social support, life satisfaction, flourishing, and distress), as detailed in what follows. The research was carried out in adherence with the British Psychological Society's Code of Ethics and Conduct.

Measures

Adaptability

The Adaptability Scale (Martin et al., 2013) was used to measure students' adaptability. This scale comprises three items concerning emotional adaptability (e.g., “I am able to reduce negative emotions to help me deal with uncertain situations”), and six items relating to cognitive-behavioral adaptability (e.g., “I am able to revise the way I think about a new situation if necessary”). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Prior measurement work has revealed adequate psychometric properties (see Martin et al., 2012, 2013). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was.91.

Perceived Social Support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al., 1988) was used to measure students perceived social support. The scale comprises four items concerning support from the family (e.g., “I get the emotional help and support I need from my family”), four items concerning support from friends (e.g., “My friends really try to help me”) and four items concerning support from significant others (e.g., “There is a special person who is around when I am in need”). All items were rated of a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 7 (very strongly agree). Prior measurement work has revealed satisfactory reliability and construct validity (see Zimet et al., 1988). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.93.

Psychological Wellbeing

There have been calls for research of this kind to incorporate measures of both mental health and mental wellbeing (Hone et al., 2014), and to capture both “hedonic” wellbeing (i.e., the affective or “feeling good” dimension, such as life-satisfaction) and “eudaimonic” wellbeing (the psychological functioning or “living well” dimension, such as personal growth/flourishing) (see Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2016). Therefore, to respond to such calls, in the present study, we include three measures of psychological wellbeing: Flourishing; Distress; and Life Satisfaction.

Flourishing

The Flourishing Scale (FS; Diener et al., 2009) was used to measure students' self-perceived success and psychological wellbeing. The scale comprises eight items (e.g., “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life”). All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Prior measurement work has demonstrated satisfactory reliability and convergent validity with other wellbeing scales (see Diener et al., 2009). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.92.

Distress

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., 2002) was used to measure students' general level of psychological distress. The scale comprises 10 items (e.g., (e.g., “During the last 30 days, about how often did you feel nervous?”). All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Prior measurement work has revealed adequate psychometric properties (see Kessler et al., 2002). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.91.

Life Satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) was used to measure students' general level of satisfaction with their lives. The scale comprises five items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”) using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Prior measurement work has demonstrated the reliability and validity of the scale (see Pavot et al., 1991). Cronbach's alpha in the present study was 0.83.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

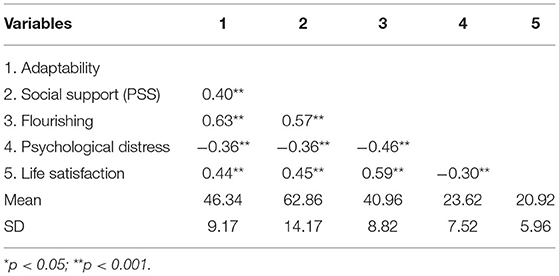

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the key variables are presented in Table 1. As indicated, adaptability and perceived social support were significantly positively associated with flourishing and life satisfaction. Moreover, both adaptability and perceived social support were significantly negative associated with psychological distress. Mann-Whitney U tests revealed no significant differences in wellbeing (U = 12,907.5, p = 0.82), distress (U = 13,215.5, p = 0.88), or life satisfaction scores by sex (U = 14,054, p = 0.26).

Moderated Regression Analyses

All regression assumptions for this dataset were met for each model. Moderated regression analyses were conducted to examine perceived social support as a moderator of the relationship between adaptability and psychological wellbeing outcomes (wellbeing, distress, life satisfaction), respectively. The total scores of the key predictor variables (i.e., Adaptability) and the moderator (i.e., Social Support) were first mean-centered and an interaction term computed by multiplying the centered predictors (Aiken and West, 1991).

Flourishing

It was found that there was a significant positive relationship between adaptability (β =0.52, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.41, 0.58]), and perceived social support (β = 0.39, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.18, 0.28]), on psychological wellbeing. However, there was no interaction effect observed (β = 0.00, p = 0.39, 95% CI = [−0.00,0.00]). The variance explained by the predictors was 55%.

Distress

It was found that there was a significant negative relationship between adaptability (β = −0.26, p <0.001, 95% CI = [−0.31, −0.12]), and perceived social support (β = −0.29, p <0.001, 95% CI = [−0.21, −0.09]), on psychological distress. The variance explained by the predictors was 18%. A significant interaction effect was also observed (β = −0.11, p =0.04, 95% CI = [−0.00,0.00]) although the effect size of this interaction was very weak in magnitude (Cohen's f2 = 0.01). A simple slopes analysis was then conducted at both high (+1SD) and low (−1SD) mean levels of perceived social support. Analyses revealed that at high levels of perceived social support there was a stronger negative relationship between adaptability and distress (β = −0.28, p <0.001, 95% CI = [−0.42, −0.15]) in comparison to when perceived social support was lower (β = −0.14, p =0.002, 95% CI = [−0.24, −0.05]).

Life Satisfaction

It was found that there was a significant positive relationship between adaptability (β = 0.39, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.19, 0.33]), and perceived social support (β = 0.29, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.08, 0.16]), on life satisfaction. The variance explained by the predictors was 28.8%. A significant interaction effect was also observed (β = 0.12, p = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.00, 0.00]) although the effect size of this interaction was very weak in magnitude (Cohen's f2 =0.01). A simple slopes analysis was then conducted at both high (+1SD) and low (−1SD) mean levels of perceived social support. Analyses revealed that at high levels of perceived social support there was a stronger positive relationship between adaptability and life satisfaction (β = 0.31, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.21, 0.44]) in comparison to when perceived social support was lower (β = 0.20, p <0.001, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.27]).

Discussion

The present study examines the influence of adaptability and social support on Chinese university students' psychological wellbeing (flourishing, distress, and life satisfaction). Our analyses were consistent with previous work showing that students' adaptability and social support were significantly related to all outcome variables (Zhou and Lin, 2016; Holliman et al., 2021). Moreover, our findings support the conservation of resources (COR) model (Hobfoll, 2001; Dollete and Phillips, 2004) which posits that personal (i.e., adaptability) and conditional (i.e., social support) resources are useful in protecting oneself against current and future stress. As such, individuals with more (higher) resources may have a greater capacity to manage and cope with stress and have greater psychological wellbeing outcomes.

There were some other interesting findings observed. Specifically, we noted significant interaction (i.e., moderation) effects such that the relationship between adaptability and psychological wellbeing outcomes (distress, life satisfaction) was stronger when social support was higher. These findings are consistent with those of Zhou and Lin (2016) who also recruited from a Chinese sample. However, our findings contradict those from Holliman et al. (2021) who observed no moderation effects using samples from the United Kingdom. As such, it may be that social support can be more beneficial and aid adaption to situations of novelty and change for Chinese rather than UK samples. It is important to note, however, that the magnitude of the moderation effects observed in the present study were very small (trivial). Therefore, these beneficial effects are unlikely to be observed in “real life”. We suggest future researchers more closely examine how and why social support may be a moderator for specific populations (e.g., Chinese) using more qualitative designs and perhaps experience sampling methodology.

Implications

The findings of this study have valuable implications for educators and researchers particularly within the UK higher education sector regarding how best to support the transition of international (in this case Chinese) students to UK universities. As adaptability is an alterable construct (van Rooij et al., 2017), universities could provide interventions following the suggestions from Martin et al. (2015) to (1) teach students how to recognize new circumstances that might require regulatory responses; (2) teach them how to make appropriate cognitive, behavioral, and emotional adjustments; and (3) help students to notice the positive effect of these adjustments and process the regulatory responses. In terms of promoting the perceived social support, it is important for universities to encourage students to maintain and access social support networks (e.g., from existing family and friends); although, admittedly, this may be more difficult when based in a different country. Universities might also promote the development of friendships via organized activities, events, and initiatives. Zhai (2004) suggested informative orientation would be an effective strategy for international students to help them familiar with university life in a foreign country and be ready to make appropriate adjustment.

Limitations and Further Directions

There are some limitations of this study that need to be addressed to interpret the findings. First, the study focused solely on Chinese international students studying in the UK. Further research is needed with more powerful and diverse samples, to examine the extent to which these findings apply to other types of international students (i.e., not just Chinese students) studying in different institutions and countries (beyond the UK). Second, since the research was conducted using a quantitative approach, the interpretation of the results is somewhat limited, and the nuances associated with students' lived experience are not represented. Future research adopting more qualitative approaches, may be fruitful for understanding the experience of transitioning to an overseas university and uncovering the dynamics of adaptability, social support, and psychological wellbeing. Third, the current research focused on some of the individual-level variables, however, other factors might be related to Chinese international students' psychological functioning e.g., at the teacher or institution level. Relatedly, other variables not included in this study might have been assessed for and statistically controlled, such as their socio-economic status, attendance, or their academic achievement. Finally, the study reported here used a concurrent, correlational design; therefore, it is not possible to establish cause-effect relations (these can only be conceptually inferred).

Conclusion

The present study showed that Chinese international students' adaptability and social support could make a unique contribution to their psychological wellbeing in the form of flourishing, distress, and life satisfaction. Social support was also found to moderate the association between adaptability and two of the psychological wellbeing outcomes: life satisfaction and psychological distress. However, the moderation effect was very weak in magnitude. Taken together, these findings have important implications for educators and researchers, who are seeking to support the transition of international (overseas) students to university and optimize their experience.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AH, YS5ob2xsaW1hbkB1Y2wuYWMudWs=.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the participating University; British Psychological Society. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AH contributed to idea conception. AH and DW contributed to analysis of the datasets. AH, DW, and NA contributed to the write-up and editing of the manuscript. DW contributed to writing the results section. TY, CK, and MZ contributed to idea conception, data collection, and editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. London: Sage Publications, Inc.

Berndt, T. J.. (1989). “Obtaining support from friends during childhood and adolescence,” in Children's Social Networks and Social Supports, ed D. Belle (New York, NY: Wiley), 308–331.

Burns, E. C., Martin, A. J., and Collie, R. J. (2018). Adaptability, personal best (PB) goals setting, and gains in students' academic outcomes: a longitudinal examination from a social cognitive perspective. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 53, 57–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.02.001

Buzzai, C., Sorrenti, L., Orecchio, S., Marino, D., and Filippello, P. (2020). The relationship between contextual and dispositional variables and well-being and hopelessness in school context. Front. Psychol. 11:533815. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.533815

Cauce, A. M., Mason, C., Gonzales, N., Hiraga, Y., and Liu, G. (1994). “Social support during adolescence: methodological and theoretical considerations,” in Social Networks and Social Support in Childhood and Adolescence, eds F. Nestmann and K. Hurrelmann (New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter),89–108.

Cohen, S., and Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 98, 310. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., and Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49, 71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2009). New measures of well-being: flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 39, 247–266. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12

Dollete, S., and Phillips, M. (2004). Understanding girls' circle as an intervention on perceived social support, body image, self-efficacy, locus of control and self-esteem. J. Psychol. 90, 204–215.

Heckhausen, J., Wrosch, C., and Schulz, R. (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol. Rev. 117, 32–60. doi: 10.1037/a0017668

Higher Education Statistics Agency (2021). Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2019/20 - Where Students Come From and Go to Study. Available online at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/27-01-2021/sb258-higher-education-student-~statistics/location

Hobfoll, S. E.. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E.. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 50, 337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., and Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources: social support resource theory. J. Soc. Pers. Relationships 7, 465–478. doi: 10.1177/0265407590074004

Holliman, A. J., Waldeck, D., Jay, B., Murphy, S., Atkinson, E., Collie, R. J., et al. (2021). Adaptability and social support: examining links with psychological wellbeing among UK students and non-students. Front. Psychol. Educ. Psychol. 12:636520. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.636520

Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., Schofield, G. M., and Duncan, S. (2014). Measuring flourishing: the impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 4, 62–90. doi: 10.5502/ijw.v4i1.4

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., et al. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32, 959–956. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074

Kong, F., Zhao, J., and You, X. (2013). Self-esteem as mediator and moderator of the relationship between social support and subjective well-being among Chinese university students. Soc. Indic. Res. 112, 151–161. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0044-6

Lakey, B., and Cohen, S. (2000). “Social support theory and measurement,” in Social Support Measurement and Intervention: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists, eds S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, and B. H. Gottlieb (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 29–52. doi: 10.1093/med:psych/9780195126709.003.0002

Lee, S. J., Srinivasan, S., Trail, T., Lewis, D., and Lopez, S. (2011). Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning. Internet Higher Educ. 14, 158–163. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.04.001

Li, J., Liu, M., Peng, M., Jiang, K., Chen, H., and Yang, J. (2019). Positive representation of relatioqnal self-esteem versus personal self-esteem in Chinese with interdependent self- construal. Neuropsychologia 134, 107195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107195

Mackey, J. D., Ellen, B. P. III., Hochwarter, W. A., and Ferris, G. R. (2013). Subordinate social adaptability and the consequences of abusive supervision perceptions in two samples. Leadersh. Q. 24, 732–746. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.07.003

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2012). Adaptability: conceptual and empirical perspectives on responses to change, novelty and uncertainty. Austral. J. Guidance Counsell. 22, 58–81. doi: 10.1017/jgc.2012.8

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S., and Liem, G. A. D. (2013). Adaptability: how students' responses to uncertainty and novelty predict their academic and non- academic outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 728–746. doi: 10.1037/a0032794

Martin, A. J., Nejad, H. G., Colmar, S. H., Liem, G. A. D., and Collie, R. J. (2015). The role of adaptability in promoting control and reducing failure dynamics: a mediation model. Learn. Individ. Diff. 38, 36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.02.004

Matheson, R., Tangney, S., and Sutcliffe, M. (2018). Transition In, Through and Out of Higher Education: International Case Studies and Best Practice. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315545332

Pavot, W. G., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., and Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the satisfaction with Life Scale: evidence for the cross-method convergence of well- being measures. J. Pers. Assess. 57, 149–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5701_17

Pierce, G. R., Sarason, I. G., and Sarason, B. R. (1996). “Coping and social support,” in Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications, eds M. Zeidner and N. S. Endler (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons), 434–451.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Ten Klooster, P. M., Drossaert, C. H., Pieterse, M. E., Bolier, L., Walburg, J. A., et al. (2016). Validation of the flourishing scale in a sample of people with suboptimal levels of mental well-being. BMC Psychol. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40359-016-0116-5

van Rooij, E. C. M., Jansen, E. P. W. A., and van de Grift, W. J. C. M. (2017). Secondary school students' engagement profiles and their relationship with academic adjustment and achievement in university. Learn. Individ. Diff. 54, 9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2017.01.004

Wills, T. A.. (1991). “Social support and interpersonal relationships,” in Prosocial Behavior, ed M. S. Clark (London: Sage Publications, Inc.), 265–289.

Winne, P. H., and Hadwin, A. F. (2008). “The weave of motivation and self-regulated learning,” in Motivation and Self-Regulated Learning: Theory, Research, and Application, eds D. H. Schunk and B. J. Zimmerman (New York, NY: Routledge), 297–314.

Yildiz, M., and Karadaş, C. (2017). Multiple mediation of self-esteem and perceived social support in the relationship between loneliness and life satisfaction. J. Educ. Pract. 8, 130–139.

Zhai, L.. (2004). Studying international students: adjustment issues and social support. J. Int. Agric. Extension Educ. 11, 97–104. doi: 10.5191/jiaee.2004.11111

Zhou, M., and Lin, W. (2016). Adaptability and life satisfaction: the moderating role of social support. Front. Psychol. 7, 1134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01134

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., and Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 52, 30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Keywords: adaptability, social support, wellbeing, university, Chinese

Citation: Holliman A, Waldeck D, Yang T, Kwan C, Zeng M and Abbott N (2022) Examining the Relationship Between Adaptability, Social Support, and Psychological Wellbeing Among Chinese International Students at UK Universities. Front. Educ. 7:874326. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.874326

Received: 12 February 2022; Accepted: 11 April 2022;

Published: 04 May 2022.

Edited by:

Yvonne Skipper, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Halis Sakiz, Mardin Artuklu University, TurkeyLuana Sorrenti, University of Messina, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Holliman, Waldeck, Yang, Kwan, Zeng and Abbott. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrew Holliman, YS5ob2xsaW1hbkB1Y2wuYWMudWs=

Andrew Holliman

Andrew Holliman Daniel Waldeck

Daniel Waldeck Tiange Yang1

Tiange Yang1