- 1LE@D, Departamento de Educação e Ensino a Distância, Universidade Aberta, Lisbon, Portugal

- 2CIEd, Instituto de Educação, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal

- 3CIPEM/INET-Md, Escola Superior de Educação, Instituto Politécnico do Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 4ISCTE, Instituto Universitário de Lisboa/Centro de Investigação e Estudos de Sociologia (CIES-ISCTE), Lisbon, Portugal

- 5CIIE, Faculdade de Psicologia e Ciências da Educação, Universidade do Porto, Porto, Portugal

- 6CEIS20, Centro de Estudos Interdisciplinares do Século XX, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

In the context of schools’ growing autonomy, external evaluation mechanisms, including External Evaluation of Schools (EES), are increasingly central to educational policies. This paper is based on the documentary analysis of all reports of the third cycle of EES in Portugal (77 reports), focusing on two of the sections of those reports—the strengths and areas for improvement identified in them. The analysis intends to uncover the areas EES is currently stressing as relevant to assess schools’ quality and identify tendencies across years of implementation and territorial areas (TAs). The results identify some impacts from the TAs, highlighting the effects of the agents interpreting and implementing the policies. Some areas are highlighted as critical—such as the impact of self-evaluation, management, curriculum management, supervision and accompaniment of teaching practices, evaluation, pedagogical practices, or the analysis and improvement of the results. These areas are aligned with broader educational policy priorities.

Introduction

The external evaluation of schools (EES) is a complex process which has globally gained centrality in the scope of public policies for education. External evaluation policies aim to ensure education quality publicly, support improvements and changes, and guide educational actions (European Education Culture Executive Agency Eurydice, De Coster et al., 2016).

External evaluation is increasingly relevant in the context of complex governing—which is the case in western countries, where societies are heterogeneous and fragmented. This fragmentation and complexity are closely linked to the public questioning of policies, as described by Innerarity (2021). In effect, the organization of societies has changed “in terms of family structure, in terms of the job market, work modalities and conditions, and of the relevance of leisure as a need and as a service” (Clímaco, 2005, p. 21). In response to these pressures, “in several countries, a restructuring of the state’s educational systems has been taking place, in the function of an entrepreneurial managerialism mainly preoccupied with results and performance” (Afonso, 2000, p. 202). According to this perspective, schools should set their own goals, strategic mission, and objectives, assessed through performance indicators. Schools need to fulfill the educational policy’s general goals emanated from the Ministry of Education (Afonso, 2000; Barroso, 2005, p. 97).

This way of conceiving schools is subjacent to the notions of autonomy and decentralization (Mouraz et al., 2019). Applied to schools, autonomy implies that each school has the capacity (or a margin) for self-governing decision-making in specific domains—strategical, pedagogical, administrative, or financial—through the attribution transferred from the other levels of administration (Barroso, 2005, p. 108). However, this autonomy is not designed as an end itself but rather as a means to provide schools with the capacity to better respond to the children and youth’s educational needs, in response to the need for contextualization determined by the social diversity that permeates societies.

In this process of restructuring educational policies, it is possible to identify tensions between logics of personalization and of social control (Pacheco et al., 2014; Morgado, 2020)—namely, the need to respond to individual needs and characteristics and differentiate, on one hand, and to retain some forms of central state control over schools, in a movement of recentralization through what Ball has referred to as governing by numbers (Ball, 2015) or performativity (Ball, 2003), where assessment and monitoring become the fundamental tools for governing. These decentralization efforts are also permeated by the national integration of policies defined at a supernational level—such as the concept of quality (Pacheco et al., 2020), specifically schools’ quality, and quality of the learning that takes place in schools. Quality is a multifaceted concept, which can only be understood within the conceptual frame of reference of those defining it; in this perspective, an understanding of how quality is understood and defined by those in power and expressed in norms is relevant (Seabra et al., 2021). The concepts of information and assessment are deeply connected to educational quality. Without information, it is impossible to assess, and therefore to emit a “systematic judgment of the value or merit” (Clímaco, 2005, p. 103) of the object of assessment and, thus, of its quality.

Despite its risks, it is possible to identify a decisive impact of EES for schools’ self-reflection and induction of changes to several areas of schools’ activities (Ehren and Shackleton, 2016b; Fialho et al., 2020). EES also fulfills an essential role in monitoring the quality of schools, encouraging continuous improvement, involving the school educational community, and for accountability in a logic of transparency (OECD, 2013; Li et al., 2019).

Aiming to reach this sought-after quality of schools and school clusters of non-higher education in Portugal, the approval of Law No. 31/2002, of 20 December 2002, regulates the schools’ external evaluation process. This law presents the evaluation process as structured into two distinct and complementary dimensions: self-evaluation/internal evaluation (article 5) and external evaluation (article 8). According to Correia et al. (2015, p. 100), “the processes of external evaluation and self-evaluation are proposed as decisive instruments for improving the quality of the educational service.” External evaluation is performed by the elements exterior to the school organization. This type of evaluation occasionally happens and is formal and guided by a program that discriminates a frame of reference comprising a set of indicators. Such indicators intend to simplify the complex reality of schools and should be helpful in policy and regulation (Clímaco, 2005).

It is therefore essential to consider the frames of reference guiding the EES process. In Portugal, this process is currently in its third cycle of implementation. This third cycle of evaluation recognizes the following as its goals: “to promote the quality of teaching, learning and inclusion of all children and students; to identify the strengths and priority areas to improve the planning, management, and educational action of schools; to assess the effectiveness of schools’ self-evaluation practices; to contribute to a better public knowledge of the quality of schools’ work; and to produce information to support decision making in the scope of developing educational policies” (General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC], 2019, p. 1).

As is the case for other educational policies, also for EES, the pathway between policy design and implementation is not linear. Several actors and contexts of influence affect it. The professionals implementing any policy have a fundamental and creative role in its translation into practice that cannot be reduced to a mere implementation of the prescribed text, which is particularly relevant when faced with “writerly” texts, that is, texts that are more open to interpretation (Ball and Bowe, 1992; Mainardes, 2006).

The frame of reference of the third cycle of EES can be understood in the context of a more comprehensive set of public policies for education aimed at reinforcing equity in access to education and educational success in the context of curricular flexibility and reinforced relevance of pedagogical practices. In particular, the diploma establishing the principles and norms for inclusion as a process to respond to the diversity of each student’s needs and potentials (Law-decree No. 54/2018 of 6 July 2018). Also relevant in this frame is the diploma establishing the curriculum for basic and secondary education, the guiding principles for its conception, the operationalization and evaluation of learning as well as the principles of curricular autonomy and flexibility (Law-decree No. 55/of 6 July), and the Profile of students at the end of mandatory schooling (Dispatch No. 6478/2017 of 26 July). These contemporary documents stress the schools’ autonomy and need to contextualize their action, calling for EES reframing.

As pointed out by Fialho et al. (2020), the focus on the schools’ educational activities, specifically teaching practices, seems to be at the core of the intent of improvement of the third cycle of EES, which is coherent with the broader frame of educational policies we described earlier. The same authors also note a focus on processes rather than results as one of the main differences between the current model and its predecessor.

Schools are assessed by an external team, coordinated by the two members from the General Inspectorate of Education, including two external evaluators, usually from academia. The teams visit schools, perform documentary analysis, apply and analyze questionnaires, and conduct panel interviews with several stakeholders from the educational community (General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC], 2018a). As we understand that policy implementation is critically dependent on the actors involved in its practice (Ball and Bowe, 1992; Mainardes, 2006), we are interested in uncovering the impacts of the diversity of actors implementing EES. The EES model somewhat predicts this diversity—the fact that elements from outside of the general inspectorate of education and science are called to integrate EES teams reflects the valuing of different perspectives and is an indicator of the “writerly” nature of the frame of reference: a text considered “readerly” would not have a margin for enhancement by the different perspectives and sensibilities brought to the process by other evaluators.

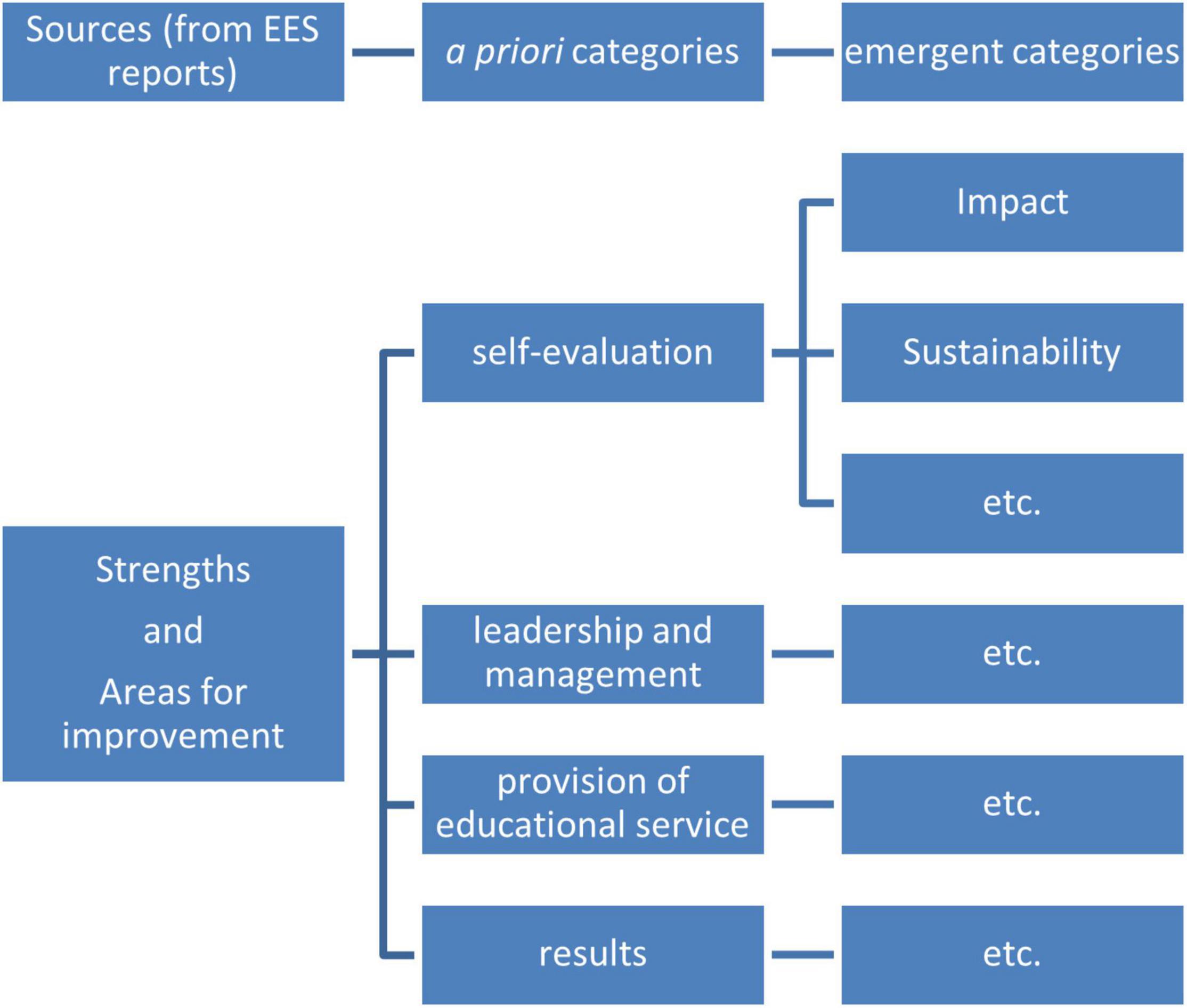

This information collected and analyzed by the EES teams is organized in a report according to the frame of reference of the third cycle of EES, including the following domains: self-evaluation; leadership and management; provision of educational service; and results (General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC], 2018b), and also includes two fields discriminating each school’s perceived strengths and areas for improvement. These last two fields were the object of analysis of the present article, as we understand these highlights, along with the qualitative mentions for each of the domains under evaluation, are the most salient aspects of the EES reports and therefore may be particularly relevant to the image of the schools portrayed in these reports. They also signal elements that schools may be pressed to improve or keep improving, as they were recognized as critical by the EES teams—we believe these aspects may be particularly relevant to understanding how EES may be inducing changes in schools’ practices.

Therefore, this article intends to reflect the perspectives of EES teams on schools’ performance, as expressed in the EES reports concerning schools’ strengths and areas for improvement, aiming to question how the priorities expressed in those fields allow us to conceive central efforts to induce practices in schools, and at what levels, as well as to shed light into the current realities of Portuguese schools, in the context of their increasing autonomy. On a second level, we intended to uncover tendencies during this third cycle of EES, namely emergent areas of focus or areas of decreasing relevance, and differences of interpretation and implementation according to the actors involved, as expressed by divergences across territorial areas (TAs) of the General Inspectorate of Education and Science.

Materials and Methods

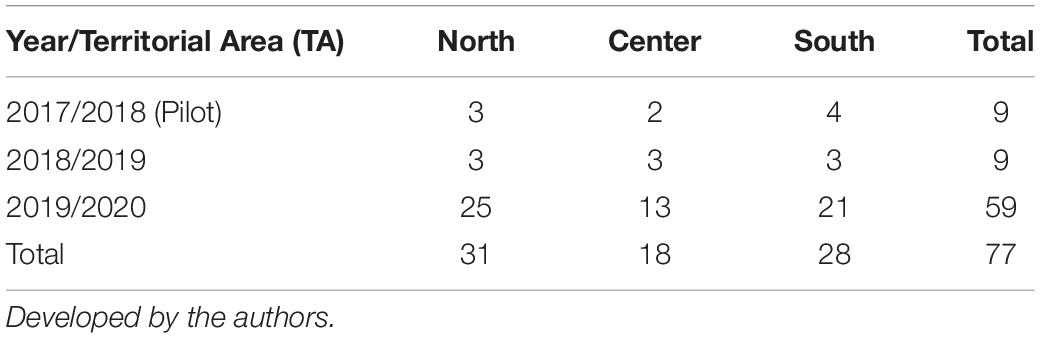

The study is inscribed in a qualitative matrix and based on the documentary analysis. The corpus of research is composed of 77 EES reports of the third cycle of EES in Portugal (between 2017/2018—a pilot phase of the third cycle of EES and 2019/2020). This number corresponds to all the EES reports of this cycle available online at the moment of data gathering—October 2021). The pandemic forced generalized school closings and brought the EES process to a halt in 2020, which explains the limited number of reports available. The EES process has recently restarted, but the most recent reports are still not publicly available. The distribution of those reports by year and by TA of the General Inspectorate of Education and Science is expressed in Table 1.

Table 1. Distribution of external evaluation of schools’ (EES) reports by school years and territorial areas (TAs).

The reports were subject to the categorical content analysis (Guerra, 2006; Tuckman, 2012), aiming to identify and quantify the segments of text relating to strengths and areas for improvement in the EES reports of schools and school clusters. The domains of the EES frame of reference (General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC], 2018b), namely, self-evaluation, leadership and management, the provision of educational service, and results, were taken as a priori categories for analysis. Emergent categories and subcategories were developed within each of these a priori categories to help describe and organize the content of the analyses expressed in the EES reports concerning the strengths and areas for improvement in each of the domains under investigation. Considering the nature of the material under study—the strengths and areas for improvement are presented as short but very content-rich and dense paragraphs—the emergent categories used are not mutually exclusive. Therefore, one segment may be categorized under more than one category. A scheme of the structure of the analysis is presented in Figure 1.

The analysis process involved the three phases described by Bardin (2009). The first stage, pre-analysis, corresponds to systematization, schematization, and note-taking. The second stage explores the material, the definition of registry units (in the present case, the sentence was chosen), contextual units, and categorization. This process was supported by using the MaxQDA 2022 qualitative analysis software (Kuckartz and Radiker, 2019). Finally, the third stage of analysis corresponds to inference and interpretation. This process makes finding patterns similitudes and establishing relationships between data possible. During this stage, the theoretical background can also guide interpretation and help clarify and enhance knowledge about the object of study (Moura et al., 2021). We compared the frequency of the categories across years of EES implementation and TAs of the General Inspectorate of Education and Science. A comparative analysis is also presented when the emerging subcategories showed significant overlapping, for the same domain of EES, between strengths and areas for improvement.

Ethical considerations in educational research, as for research in general, are critical because they affect the integrity of the work (CIRT, 2019). The adoption of ethical principles must be ensured at all stages of the research process, ensuring: the correct referencing of ideas mobilized from other authors, the transparency of the methodological design, the guarantee of subjects informed and voluntary participation, as well as the protection of their identity, and the rigor in data analysis and presentation of results and conclusions (Bassey and Owan, 2019). In the present article, the guarantee of anonymity is relevant. Even though the data under analysis is public (gathered from the site of the General Inspectorate of Education and Science), the authors have chosen to identify schools or school clusters using codes. This allows us to make direct references without revealing the school’s identity the report refers to (Dooly et al., 2017; ASHA, 2018). Transparency is expressed in direct quotes from the corpus of analysis to illustrate and fundament inferences.

Results

The results are organized according to the a priori categories extracted from the structure of the EES reports and the frame of reference for the third cycle of EES (General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC], 2018b). The strengths and areas for improvement are described.

Self-Evaluation: Strengths

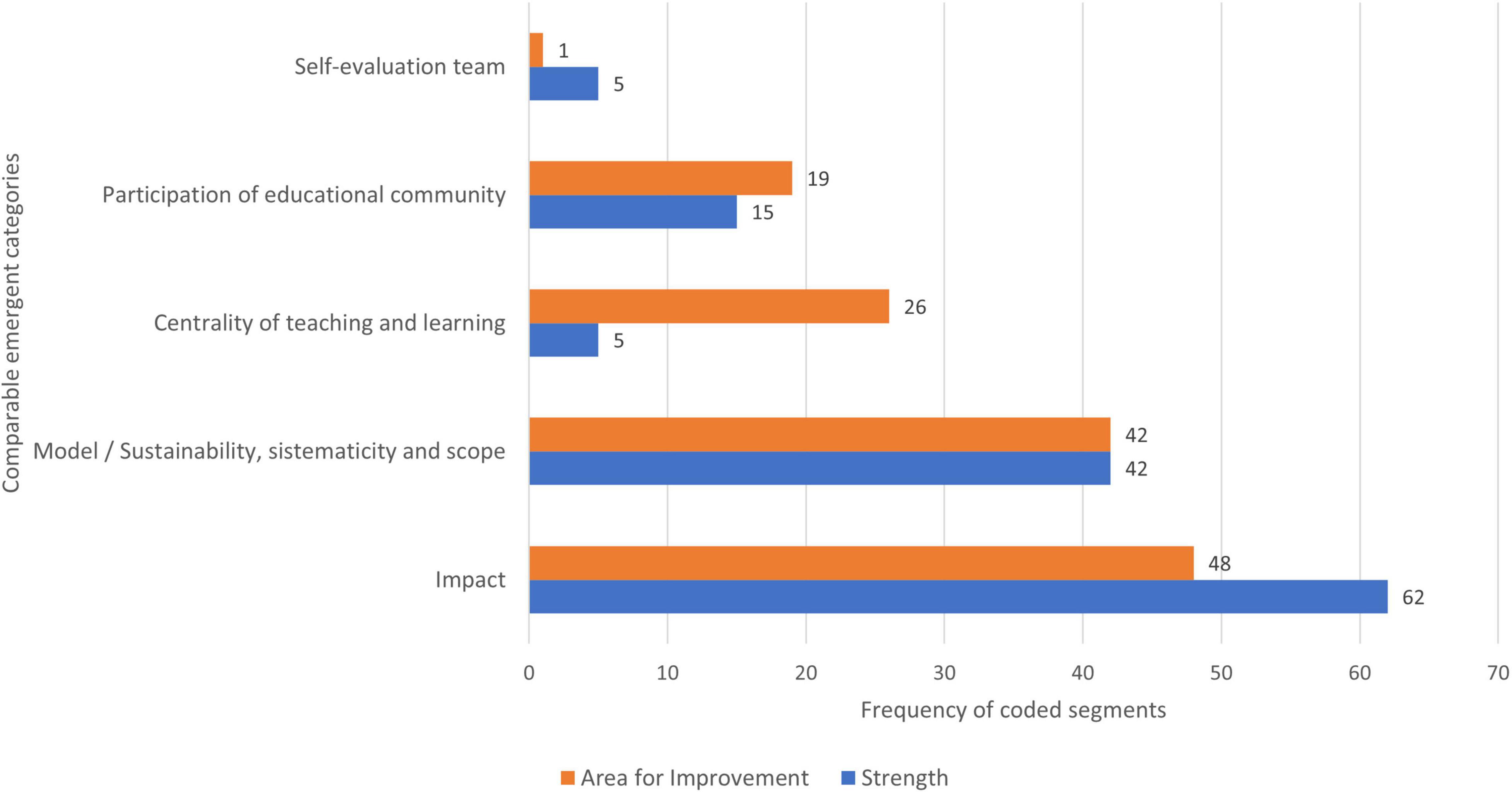

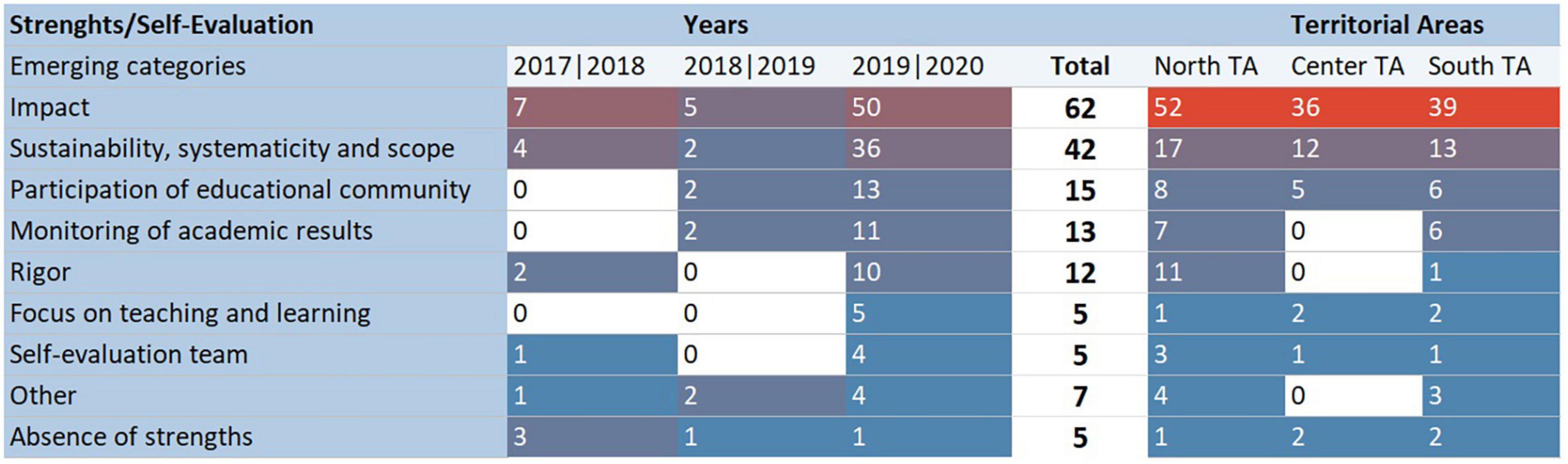

This category includes 118 codified segments of text. The distribution of coded segments by emergent subcategories, years, and TAs of the General Inspectorate for Education and Science can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Self-evaluation: strengths. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and territorial area (TA).

The most salient aspect among the strengths pointed out by EES reports in the domain of self-evaluation relates to the impacts of the schools’ self-evaluation process [62 segments, example (ex.): “Encompassing self-evaluation processes, with impact on the definition of the needs for continuous training and strategies reinforcing the inclusion of children and students”; N3]. Within those impacts, there are frequent references to the improvement of the educational service (29), to organizational improvement (13), to inclusion (8), to the identification of the schools’ strengths and needs for improvement (6), to the identification of training needs (5), and the improvement of the schools’ structuring documents (4).

The category sustainability, systematicity, and scope (42, ex.: “Consolidated and systematic processes of self-evaluation, integrated into the cluster of schools’ routines”; N15) was designed with this wide configuration because these characteristics of the self-evaluation processes were very frequently associated in reports.

The participation of the educational community in the process of self-evaluation is also frequently highlighted (15, “Scope of the process, concerning the domains under evaluation and the involvement of a significant number of elements from the educational community”; N33), corresponding to the process of data gathering as well as to the process of dissemination, discussion, and analysis.

It should be noted that five reports did not identify any strengths in the domain of those schools’ self-evaluation, which is unparalleled in any other domain. Those reports correspond to two reports of schools assessed as insufficient in this domain, and three schools assessed as sufficient, the two lowest scores possible.

Making a cross-analysis of the strengths identified in the domain of self-evaluation and the school years when that evaluation took place, we can identify some emergent themes, such as the impact of self-evaluation on inclusion and the identification of training needs, the participation of the educational community, and the focus of self-evaluation on the process of teaching and learning. This analysis is tentative as the higher number of reports from 2019 to 2020 than the previous year warrants caution. The colors used for each cell of the image represent the relative frequency of references for each column, allowing a comparison between years or TAs, and are extracted from the MaxQDA software.

Concerning the distribution by TAs, we can verify that the two categories are absent among the strengths identified in the Center TA: monitoring of academic results and rigor. The North TA reveals a proportionally higher valuing of rigor as a strength of the self-evaluation process.

Self-Evaluation: Areas for Improvement

This category includes 100 coded segments. The distribution of coded segments by emergent subcategories, years, and TAs of the General Inspectorate for Education and Science can be observed in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Self-evaluation: areas for improvement. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

The features of the schools’ self-evaluation process are highlighted as areas in need of improvement are related to their impact (48, ex.: “Designing improvement plans to consequently sustain decision-making at the levels of planning, activities management and professional practices promoting the quality of teaching and learning,” S3), the need to improve the self-evaluation model (42), the need for the self-evaluation process to focus on the teaching and learning process (26, ex.: “…conferring centrality to the processes of teaching and learning, to increase its strategic usefulness for the improvement of curriculum development, of the teaching and learning practices and teachers’ professional development,” S8), the need for greater involvement of the educational community (19), an aspect also reinforced in need to better communicate results to the educational community, mentioned eleven times, the need to monitor the improvements implemented (17), and the improvement of reflection about the results of self-evaluation (14).

The category “model optimization” encompasses suggestions to deepen and systematize the model of self-evaluation, situations referring to the need to articulate different self-evaluation processes, and even situations where the need to create a self-evaluation model, in the face of its absence or grave insufficiency, are implied. Examples of this category are: “Structuring a more integrative process for the different self-evaluation procedures in existence, to promote a more critical and impactful reflection for the continuous improvement of the school cluster” (N55), or “Developing an integrated self-evaluation process which allows the introduction of intentionally assumed improvement plans, with consequent monitoring and evaluation of impact” (N7).

The reference to the need to monitor the implementation of improvement plans is present primarily in the reports of schools that already have consistent and consequent self-evaluation processes. For example, “the deepening of the processes of monitoring the improvement actions, stemming from self-evaluation practices, to assess their impact” (N26, a report from a school assessed as Very Good in this domain).

Analyzing the categories identified in the areas for improvement in the context of self-evaluation, crossed with the years of EES they refer to, we can verify that in 2018/2019, the references to the model’s optimization were very prevalent. The reflection about the self-evaluation results was more commonplace in 2019/2020 and was absent in the reports from the pilot year and referred only once in 2018/2019, which may signal an emergent concern in this domain.

Dividing the analysis in the function of the TA the reports originate from, the references to the impact of the self-evaluation process, model optimization, and monitoring of improvement actions are relatively more frequent in the South TA. References to the participation of the community are somewhat less frequent in the Center TA.

Finding a relative overlapping between the areas for improvement and the strengths pointed out to this domain by EES reports was perplexing (Figure 4). This allows us to highlight a framework of what the EES teams have preconized as a successful self-evaluation practice: a practice with evident and monitored impacts, supported by systematic, sustainable, and encompassing procedures that involve the educational community. The centrality of the educational process of self-evaluation is portrayed as an aspect that still requires enhancement, as it is more frequently referred to as an area for improvement than a strength.

Leadership and Management: Strengths

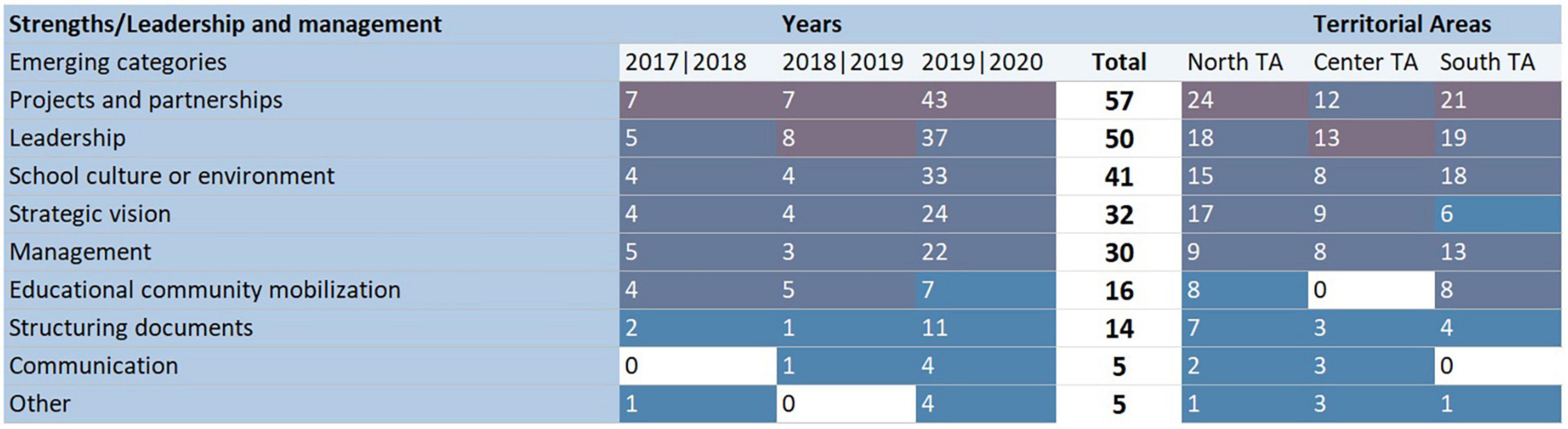

This category included 209 codified segments. The segments are distributed as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Leadership and management: strengths. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

Concerning the domain of leadership and management, the positive aspects which are highlighted are projects and partnerships (57, ex.: “The establishment of an active network of partnerships and protocols in strategic areas of intervention which contribute to the improvement of the service provided”; P8), the role of leaders (58), the school culture or environment (41, ex.: “Good educational environment, promoting safety and implementing inclusive educational and pedagogic practices”; N11), the strategic vision (32), management (30), the involvement and mobilization of the educational community (16), the structuring documents (14), and communication (5).

The category leadership is quite encompassing, including references to leadership in general or mainly focusing on a specific level. For example, “Leadership assumed by the director and their team, open to diverse educational actors… (…)” (N2).

The category related to structuring documents refers to the articulation, coherence, strategic orientation, or operationality of internal documents such as the Schools’ Educational Project, plans for activities, or curricular plan, for example, “The strategic vision expressed in the structuring documents, in tune with the matrix set by the Students’ Profile at the Exit of Mandatory Schooling and the principles for inclusive schools” (N36). The category management includes elements concerning human resources management, as well as material resources; for example, “Dynamics of the director and their team to mobilize and value internal resources, and involve community agents and institutions, with impacts on the improvement of the services provided” (N12).

The comparative analysis between the years of EES does not identify expressive tendencies. However, the crossed analysis with the TAs signals a proportionally higher valuing of leadership, a relatively lower weight attributed to projects and partnerships, and the absence of references to the mobilization of the educational community in the Center AT. In the South AT, a strategic vision was mentioned proportionately less frequently, and communication is not referenced.

Leadership and Management: Areas for Improvement

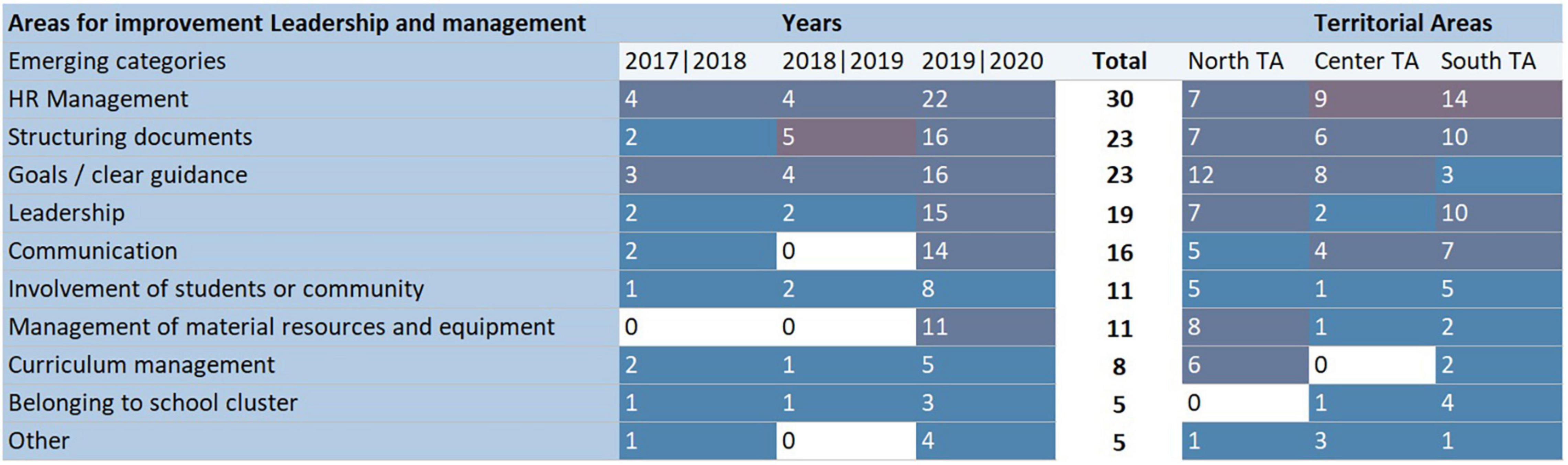

This category included 134 segments, distributed as expressed in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Leadership and management: areas for improvement. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

The matters related to management are prevalent among the areas for improvement identified in the EES reports, either through a reference to human resources management, frequently associated with their continuous training (30, ex.: “Promotion of professional development, through a plan that systematically congregates the diagnostic of needs and allows to implement actions to surpass difficulties,” P9), but also, albeit less frequently, to aspects related to material resources and equipment (11; ex: “Investment in improving mobile and technological digital equipment as tools to support learning, to promote a more motivating and autonomous work,” P9). They occasionally refer to the curricular management allowed by autonomy and flexibility (8, ex.: “Planning of curriculum development which includes decisions at the level of vertical articulation of curriculum and its contextualization for the improvement of the learning sequence” N31).

Another theme is crossing the two following categories, related to the clarity of the direction intended for the school, concern the categories goals/clear guidance (23; ex; “Defining current goals for the academic results, assumed as referential to the planning of teachers’ work and the internal monitoring the school cluster intends to achieve,” N1) and structuring documents [23, ex.: “To articulate the guiding documents of the school cluster, namely the annual plan of activities and the objectives of the educational project, identifying the competences to be reached by students (…),” N8], that partially overlap.

Other recurring themes are the actions of leaders (19), communication (16), or the involvement of students and the educational community (11). Although not frequent, there are also references to creating a sense of belonging to a school cluster (5) or other issues related to the school environment (3).

Analyzing the matrix of codes by years of EES reveals some emergent themes in recent years, namely, the management of material resources and equipment and communication. Looking at the distribution through the TAs, in the North TA, references to communication, human resources management, or involvement of students and the community, were proportionately less frequent, and the sense of belonging to the school cluster was not referenced. In the Center TA curriculum management was not categorized as an area for improvement in this domain, and references to the role of leaders were proportionately less frequent. References to goal setting and clear guidance were less frequent in the South TA than in the other regions.

Provision of Educational Service: Strengths

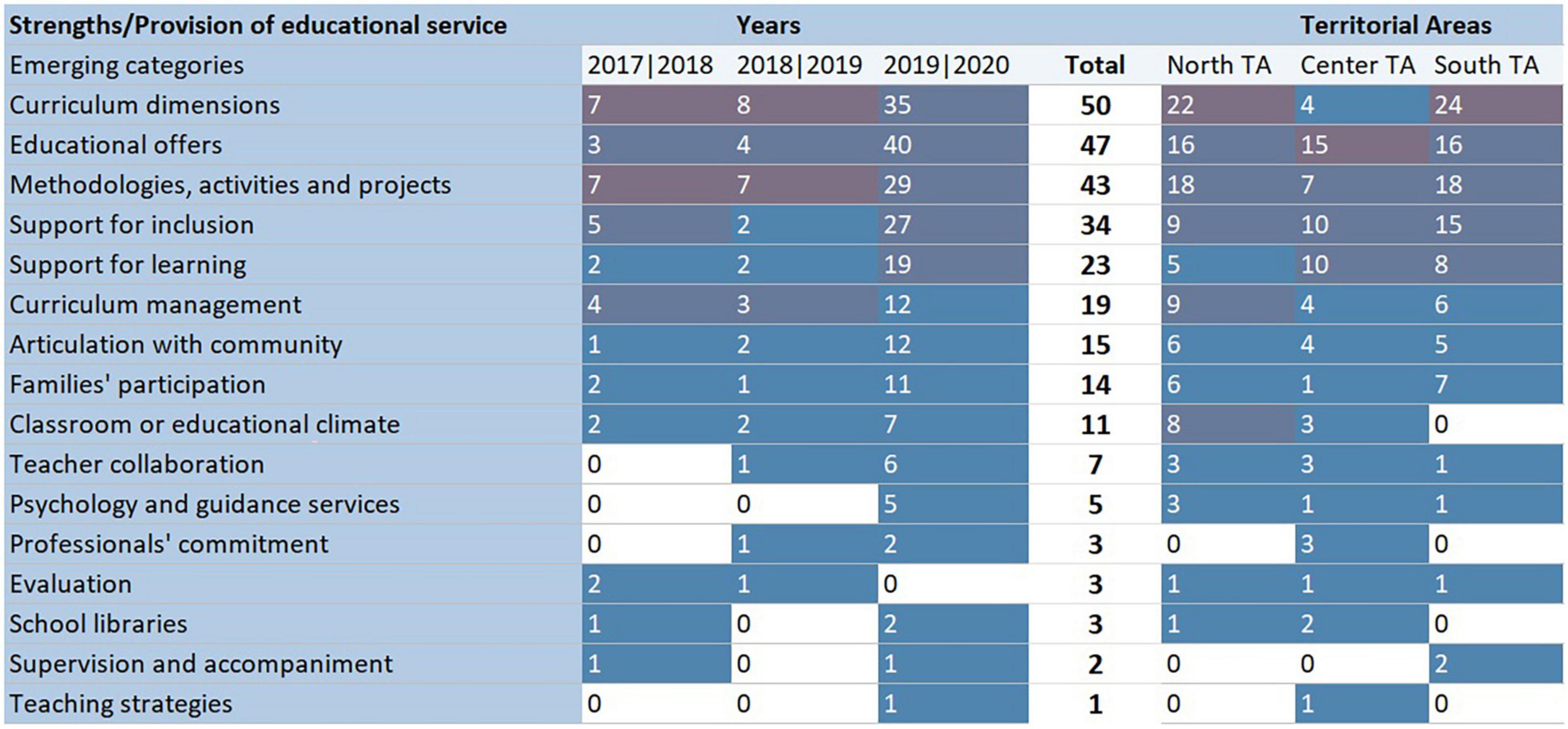

This category includes 208 coded segments and their distribution, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Provision of educational service: strengths. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

In this point, issues related to the curriculum are stressed, either concerning the valuing of diverse curricular dimensions (artistic, cultural, sports, and civic) (50, ex.: “Curricular integration of cultural, scientific and sports, that promote equality of opportunity in the access to curriculum …,” N25) or by an educational offer adequate to the needs of the population (47, ex.: “Professional courses in areas that are in agreement with the interests of students and the encompassing community…,” N2).

These issues are followed by pedagogical aspects, namely those about methodologies, activities, and projects (43, ex.: “Diversity of activities and projects, adjusted to the students’ interests…” N3), supporting inclusion (34) and learning (23), sometimes overlapping (ex.: “Implementation of measures to support learning and inclusion, promoting equality of opportunities and access to the curriculum,” N9).

Another set of references concerns articulation with the community (15) and the participation of families (14). There are also references to other pedagogical and curricular aspects. We highlight those related to evaluation (3) and supervision and accompaniment of the teaching practice (2) due to their scarcity and the contrast with the frequency of reference as areas for improvement.

The analysis of the matrix of codes by years of EES reveals that, proportionally to the number of reports for each year, the references to the valuing of diverse dimensions of curriculum and methodologies, activities, and projects are less frequent in the most recent year. Concerning the geographical distribution, we found a lower proportion of mentions of the valuing of diverse dimensions of the curriculum and a comparatively higher proportion of mentions to educational offers in the Center AT. The North AT reveals fewer mentions of support to learning and more frequent mentions of curriculum management and educational climate than the other TAs. This last aspect is never mentioned in the reports from the South TA as a strength in this domain.

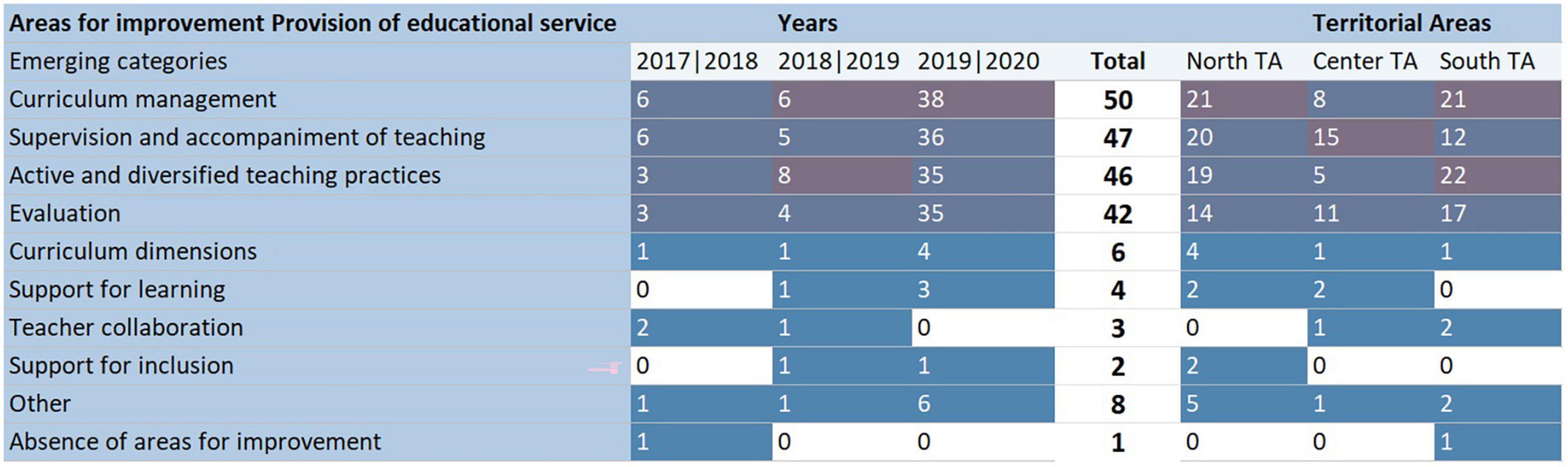

Provision of Educational Service: Areas for Improvement

This category includes 191 coded segments and their distribution, as portrayed in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Provision of educational service: areas for improvement. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

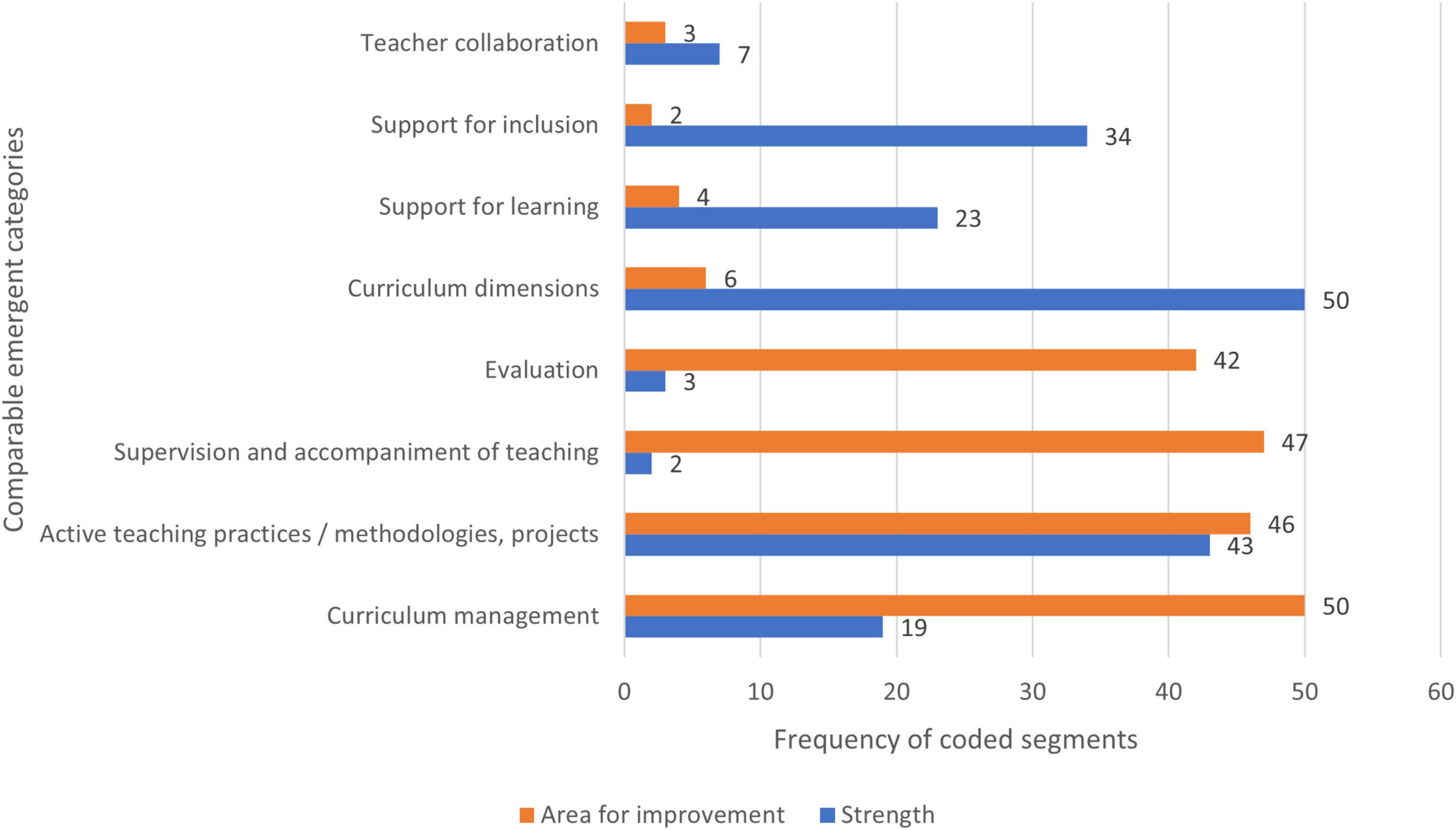

Curricular issues that have also been especially under focus as strengths are also the most frequently identified area for improvement (50, ex.: “To consolidate the practices of curricular articulation in process …,” N10), which highlights the centrality curricular matters assume in the context of the third cycle of EES. The comparison between strengths and areas for improvement is presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9. Provision of educational service: a comparison between strengths and areas for improvement.

Supervision and accompaniment of the teaching practice are in second place of the most highlighted areas (47), in contrast with only two references as a strength, which points to an area that requires particular intervention in the schools under analysis, from the perspective of the EES teams (ex.: “Strengthening the mechanisms of accompanying, regulation or supervision of the pedagogical practices in classrooms…,” N20). Interestingly, and although references to collaborative and inter-peers’ supervision practices, there are also references appealing to vertical strategies of supervision and regulation, which agree with what is present in the frame of reference for this third cycle of EES.

Next is the appeal for diverse and active pedagogical practices (46; ex: “Intensification of the project methodology as a strategy for teaching and learning, as well as performing practical and experimental activities with the students,” N31). Concrete initiatives and projects were frequently noted as strengths; however, as areas for improvement, an appeal for a transversal improvement of pedagogical differentiation and methodologic diversity is more frequent.

Also often highlighted are references to evaluation (42), almost universally pertaining to an increase of formative evaluation (ex.: “Reinforcing formative evaluation, as a process to regulate learning,” N25), once again in contrast with the rare strengths related to evaluation, seeming to reveal an area, which is particularly deserving schools’ attention, according to the view of the EES teams.

The categories support for learning, support for inclusion, and valuing the dimensions of curriculum, frequently indicated as strengths, are underrepresented among the areas for improvement, which may suggest that these are relatively well-resolved aspects in schools, from the perspective of the EES teams. One report, corresponding to a school assessed as Excellent in the domain of provision of the educational service, did not identify any areas for improvement in this domain.

According to the years of EES, the analysis of the codes’ matrix reveals a seemingly decreasing priority regarding the promotion of teachers’ collaborative work (amiss among the areas for improvement of 2019/2020). Looking at the distribution by TAs, supervision, and accompaniment of teaching seem to be proportionally more stressed in the Center AT and curriculum management frequently mentioned in the same region. In the South AT, teaching practices are proportionally highlighted.

The comparative analysis of strengths and areas for improvement identified in the reports concerning the domain of provision of educational service (Figure 9) highlights, on one hand, dimensions that seem to be transversally well resolved among the schools under evaluation and from the perspective of EES: the valuing of diverse dimensions of curriculum, support to inclusion and support to learning are much more frequently mentioned as strengths than as areas for improvement.

On the reverse end, the accompaniment and supervision of teaching practice, evaluation, and curricular management, are overwhelmingly pointed out more as areas for improvement than they are strengths.

Also deserving of reference are teaching methodologies, activities, and projects, frequently referred to as strengths (although, often, the reference includes specific actions that the EES team deems successful, ex.: “Adhesion to projects and initiatives that consolidate curricular autonomy and flexibility…,” N15) but also as areas for improvement, reporting, in this case to the need to generalize active practices of teaching and learning (ex.: “Generalization of diverse strategies of teaching and learning, in all cycles and levels of education,” N23). These areas, therefore, seem to be at the core of the pressure for improvement that EES introduces in schools, in the context of the third cycle, which is consistent with the centrality of the classroom and the improvement of teaching practices this cycle aims for.

Results: Strengths

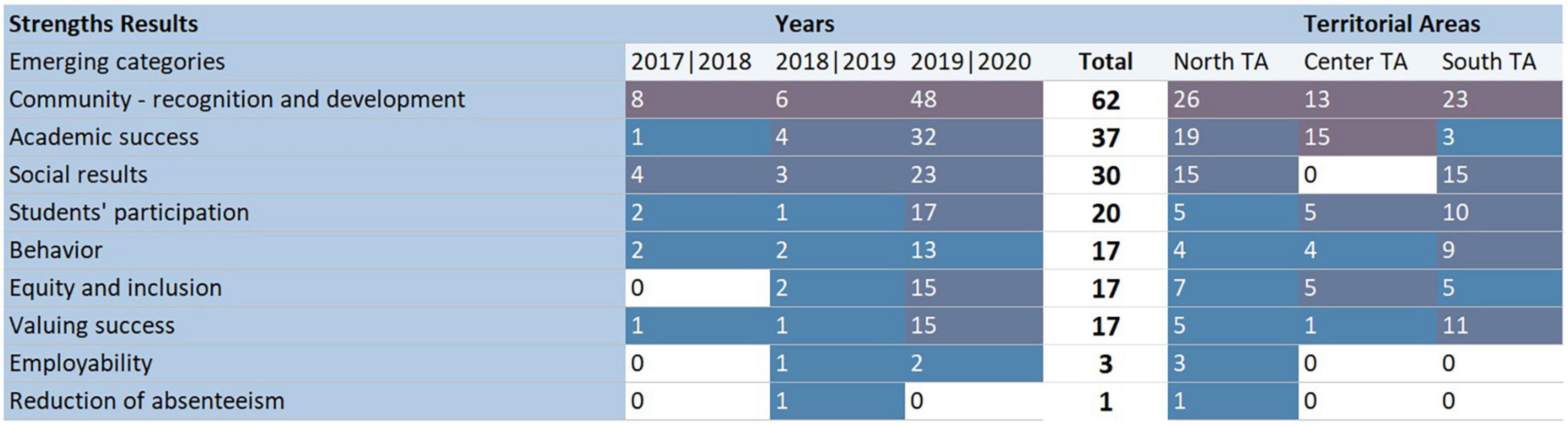

This category includes 182 coded segments, distributed as shown in Figure 10.

The most frequent strength pointed out concerning results is related to the community’s recognition or development (62, ex.: “The synergy between the school cluster and the local entities has concurred remarkably to the qualification of the human resources and the recognition by the surrounding community” P8).

Also frequent are references to various measures of academic success (pathways of direct success, improvement of a particular indicator, results above the national average…) (37, ex.: “Percentage of students who obtain a positive classification on the national exams of the 9th grade, after a pathway without retentions on the 7th and 8th grades which has grown during the last triennium,” N8).

There are also frequent references to aspects related to social results, either directly (30, ex.: “Social results resulting from an integrative and inclusive educational action,” S9), or by referencing students’ participation (20, ex.: “Stimulus to students’ participation in the schools’ life, associated with a critical, creative and collaborative culture of student intervention for the promotion of active citizenship,” N6), or even by referencing students’ behavior [17, ex.: “The work carried out for the prevention and resolution of cases of indiscipline (…),” N36].

There are also relevant references to equity and inclusion (17, ex.: “Efficacy of the measures to promote equity and inclusion…,” N15) and to the valuing of students’ success [17, ex.: “Valuing and recognition of students’ work and success by the attribution of merit and academic excellence awards (…),” N7].

The distribution of references through the categories along the years of EES reveals a growing relevance to academic success, students’ participation, valuing success, and equity and inclusion. Academic success seems to be less frequently mentioned as a strength in the South TA and proportionately more so in the Center AT. References to social results per se are absent in the reports from the Center AT. Although it is infrequent, employability and reduction of absenteeism are only referred to as strengths in this domain in the North AT.

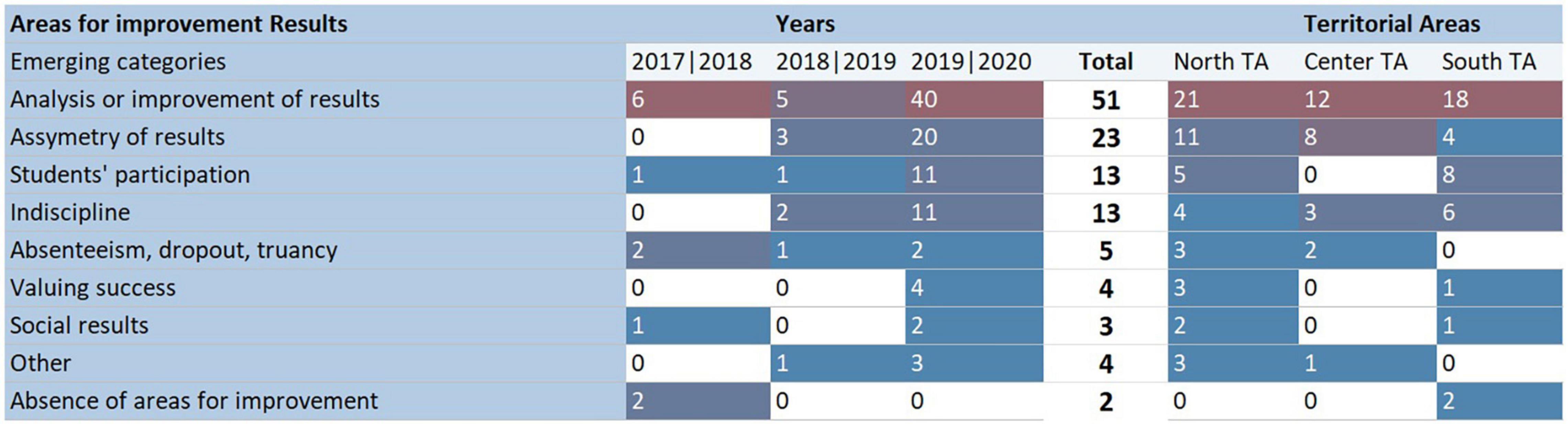

Results: Areas for Improvement

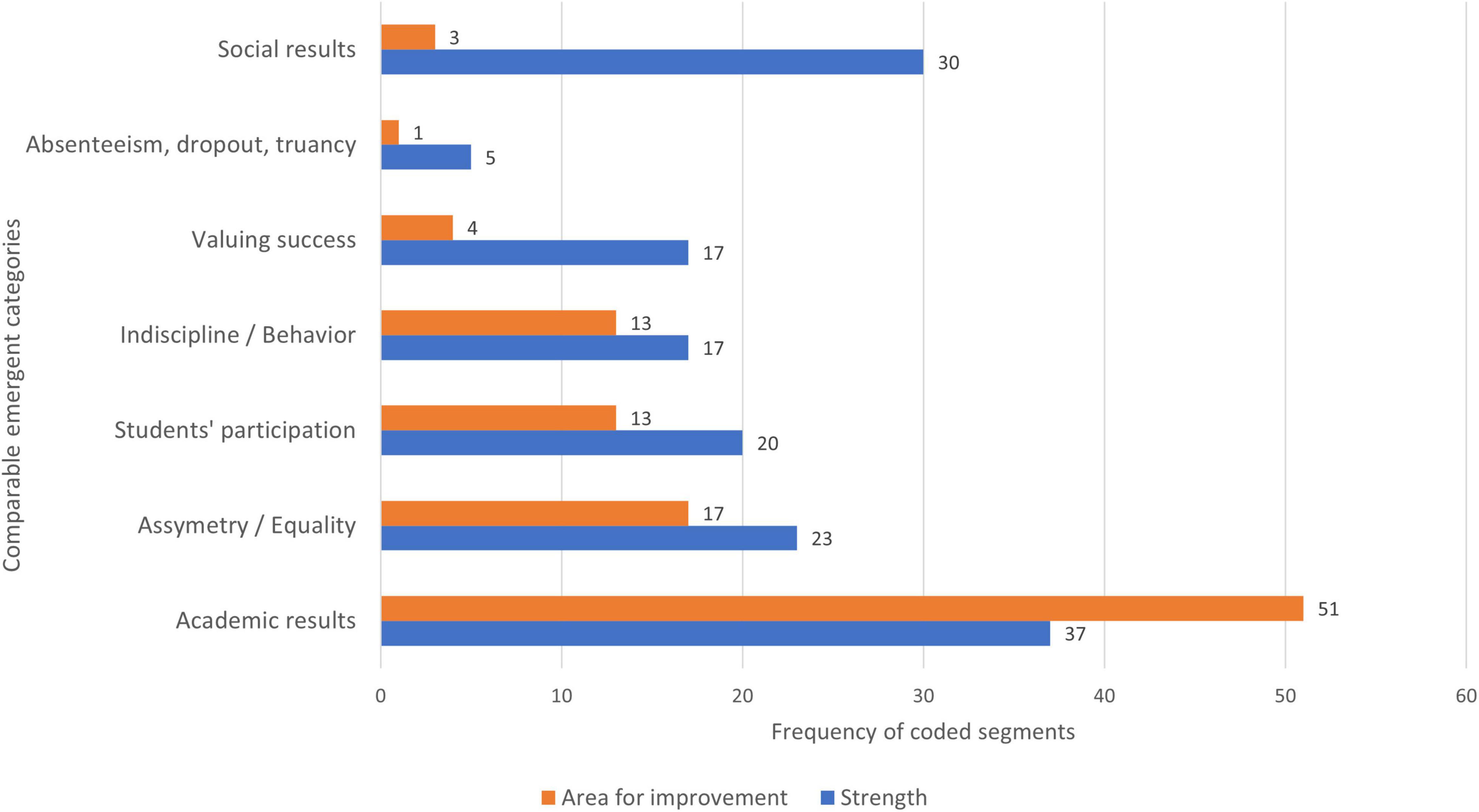

This category includes 110 coded segments distributed, as depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11. Results: areas for improvement. The distribution of coded segments by subcategories, year, and TA.

The more frequently highlighted area for improvement concerning results is related to academic results, namely, their analysis (including the diagnosis of internal causes for the lack or limitation of success), and improvement (51, ex.: “Improving the rates of conclusion, the continuation of studies and employability of students in professional education,” N22).

These references are followed by the need to reduce asymmetry in results, that we consider a reverse to the strength pointed out referring to equity and inclusion (23, ex.: “To reinforce educational measures that prove effective in the reduction of asymmetry of school results for the first cycle of basic education,” N3).

The appeals to increased participation of students in the life of the school have some expression (13, ex.: “Perfecting mechanisms for students’ participation in school life, namely through the promotion of students’ associations…,” N26) and less frequent references are present to the improvement of social results (3; “Transversal and systematic actions in the domain of solidarity and volunteering for all levels of education” P4). Indiscipline (13) and absenteeism, truancy, and dropout (5) are also referred to as areas requiring intervention in some reports. We remark that the two reports, corresponding to one school assessed as excellent and one evaluated as very good in the domain of results, did not include any areas for improvement. Analyzing the TAs, the reports originate from, references to the asymmetry of results were more prevalent in the Center TA and less so in the South TA. Several categories are not represented in one of the TAs. Indiscipline is proportionately less mentioned in the reports from the North TA.

A comparative analysis (Figure 12) acknowledges that academic success is highlighted both as a strength and as an area for improvement, suggesting the centrality this aspect retains in the context of EES. Factors related to equity and inclusion, or its reverse asymmetry, are also valued more frequently as an area for improvement but also as a strength. Students’ behavior/indiscipline and participation are also referred to as strengths and areas for improvement. Social results and recognition from the community or contribution to community development are highlighted only as strengths, which indicates that they may be relatively well resolved in schools from the perspective of the EES teams.

Discussion

We discuss the results concerning the objectives that guided our research although we assume an inverse order.

In fact, the most novel and significant result corresponds to the identification of differences in how EES is applied across TAs of the General Inspectorate of Education and Science, even though the process is based on a single frame of reference. To some extent, this finding is expected—the very fact that the EES teams include external elements, usually from academia, at least raises the issue of whether the EES frame of reference is interpreted and applied by each EES team influenced by the evaluators’ background. Previous research has already highlighted the complexity in how EES policy is translated into practice, for instance, by determining how schools and teachers have an active role in how evaluation is received and how it does or does not influence their subsequent actions (e.g., Ehren and Visscher, 2006; Ehren and Shackleton, 2016a). Our findings posit the possibility for another level of complexity due to the interference of a previous mediating level of interpretation and transformation in the process of transformation from policy into practice (Ball and Bowe, 1992; Mainardes, 2006)—the interpretation and difference of application of the frame of reference by EES teams. External evaluators, either belonging to the inspectorate or academia, seem to have an essential and active role in this process. This finding requires further research, both by widening the analysis to the previous cycles of EES in Portugal and refining the analysis. As we mentioned previously, the frame of reference for the third cycle of EES is a relatively “writerly” text (Mainardes, 2006), leaving room for agency and interpretation, which may influence results. The Portuguese EES model parallels other European models (Gray, 2014). Therefore, this finding may be helpful to policymakers, not only in Portugal but in a broader European context.

Analyzing the strengths and areas for improvement identified in the schools and school clusters subject to EES enables a double reading. Firstly, EES teams’ perspectives about the schools themselves as the analysis being—despite some disparity—based on a common and public frame of reference and necessarily grounded in evidence, justifies using the resulting EES reports as valuable sources for study. The second presupposition relates to the use of the fields concerning strengths and areas for improvement, which, as has been previously noted, correspond to the areas deemed as most relevant (either positive or problematic), and therefore likely to be priority foci of analysis and change by schools affected by the process (Seabra et al., 2021).

We set out for this analysis to consider how EES relates to schools’ autonomy. The results presented as indicators of the assumption of autonomy relate mainly with the domains of self-evaluation and provision of educational service. However, they are expressed throughout all the categories. Thus, when trying to understand the contribution of schools’ self-evaluations, as acknowledged by EES, we verify the centrality of the impact of this dimension through the high number of references found and their relationship with all the domains of schools’ action. Specifically, features, such as impact, sustainability, systematicity, and scope of the self-evaluation processes, and the participation of the educational community, were highlighted as desirable in the corpus under analysis. We also note that a report by the National Council of Education in 2008 (Conselho Nacional de Educação[CNE], 2008) reinforced the need for a greater representation of the educational community in gathering data about the schools. In this sense, a broader data gathering process, including students, families, and the representatives of local power, and not restricted to the formal structures of school organizations was valued.

When considering the results concerning the areas for improvement, we can see that the same themes emerged, with the addition of focusing self-evaluation processes on teaching and learning. These data are predictable in response to the tendency developed since the second cycle of EES. In a study conducted in 2014 about the first and second cycles of EES, Mouraz et al. (2014) had already found a distinct tendency for EES to focus on the definition of self-evaluation mechanisms of schools, which was particularly evident in the less well-assessed schools, “whereas the schools with higher classifications are those where the EES has acknowledged more consistent practices of self-evaluations, inducing a culture of self-evaluation” (p. 96). Two concluding remarks emerge from these results: the first is that the schools’ self-evaluation processes are directly linked to improving the overall quality of schools, in the perspective of EES, such as Clímaco (2005) defended. The second idea is that the construction of self-evaluation with the desired characteristics requires time for development and incorporation. A similar conclusion was found by Fialho et al. (2020) when studying the self-reflection that was carried out by schools and the conditions for its implementation.

Still concerning practices promoting schools’ self-evaluation practices, we endorse the proposals of authors such as Quintas and Vitorino (2013), who defend the two logics of action: “on the one hand, a process that directly engages teachers and schools, with eventual outside aid for the dimensions schools are less secure about, namely methodological aspects; on the other, a theoretical training on the matter, complemented by a contextualized practice of self-evaluation which should be continuously and systematically debated and analyzed among peers” (Quintas and Vitorino, 2013, p. 18).

The reinforcement of self-evaluation induced by EES may be a way of recentering control on schools, rather than the central administration, therefore avoiding the previously mentioned dangers of government by numbers (Ball, 2015) and performativity (Ball, 2003).

The centrality of teaching and learning processes in the scope of schools’ self-assessment is infrequently stressed as a strength, but it is highlighted as an area for improvement in several reports—this seems to be an area that the schools that have been assessed so far have yet to develop. Schools reflecting on the improvement of their self-assessment processes can be advised to consider this dimension, particularly given that this appears to be an emergent preoccupation of EES, more frequently expressed in the most recent reports. The centrality of teaching and learning is also a concern that aligns with more general policy concerns of recent years, as we have pointed out (Law-decree No. 54/2018 of 6 July, Law-decree No. 55/2018 of 6 July, Dispatch No. 6478/2017 of 26 July).

At the level of provision of educational service, areas such as curriculum management, pedagogical practice, evaluation, and supervision and accompaniment of teaching practice emerged as particularly salient, in agreement with a more general policy frame that has been fostering schools’ curricular autonomy. This is also an essential focus of EES, associated with the valuing of diverse dimensions of curriculum, Curriculum articulation, the adequation of schools’ curricular offer to the needs of the surrounding community, or curriculum management according to the principles of flexibility and the desired profile for students at the end of mandatory schooling, and more formative practices of evaluation of learning. Central importance is also conveyed to active and diverse pedagogical practices and school action designed to reinforce teaching capacity through supervision and accompaniment of the teaching practices. Although teaching practices are also highlighted as accomplished areas, an analysis of the contents of the appraisals reveals that positive appraisals tend to focus on selected activities and projects deemed as successful. In contrast, areas for improvement stress the generalization of active teaching practices. These data support the idea that in the third cycle of EES, as noted by Fialho et al. (2020), aspects related to process—namely curricular and pedagogical process—are highlighted, conferring centrality to the classroom.

Concerning the domain of leadership and management, human resources management, including continuous training of professionals, the school structuring documents, and the clarity of goals for the school, leadership, and communication are the most frequent areas for improvement pointed out to schools in the third cycle of EES. We also remark equipment and material resource management as a priority area, given that this appears to be an emergent concern in the latest EES reports.

Finally, concerning the domain of results, academic results remain the most prevalent concern and the most prevalent strength. Nevertheless, equity and social results are emergent preoccupations of EES—and relate to the foci of concern of concomitant educational policy. Therefore, despite being more frequently pointed out as a strength than as an area for improvement, these aspects merit the schools’ attention.

Conclusion

The present study has identified, through the analysis of all the reports from the third cycle of EES in Portugal available at the time, several areas of concern expressed by the assessments of the EES teams. Some areas, which are in line with broader educational policy tendencies focusing on inclusion, curriculum management, and autonomy (Law-decree No. 54/2018 of 6 July, Law-decree No. 55/2018 of 6 July, Dispatch No. 6478/2017 of 26 July), seem to merit particular investment from the part of schools aiming to improve their assessment. We highlight, in terms of schools’ self-assessment practices, its scope, openness to the educational community, as well as its sustainability and its impact on school improvement. An emergent concern relates to how much schools’ self-evaluation processes focus on teaching and learning. On the same note, in the domain of the provision of educational service, curriculum management, generalized active teaching methods, and evaluation, including formative evaluation of students’ learning, are stressed as critical areas for improvement. In the domain of leadership and management, human resources management, as well as the categories related to a sense of direction for the school and to its expression in the schools’ documents, are stressed, along with an emergent theme related to the management of material resources and equipment. In relation to the results, and while academic results remain central, improvement of aspects related to equity and social results seem to be gaining expression.

The differences found among TAs of the general inspectorate of education may be of value to educational policymaking and understanding. More relevant than specific differences, which may vary as more reports are produced, is the very fact that differences are present. While these differences may reflect the characteristics of the schools under evaluation and the territories they are located in, they point to the possibility of a level of interpretation of the EES referential by the EES teams, which highlights the active role and critical importance of EES teams’ constitution and training. The diversity, and richness of perspectives provided by the constitution of these teams, including members of the inspectorate as well as external members (usually from academia), seem to be incorporated in the model for the third cycle of EES as it increased the number of external evaluators. The specific backgrounds and sensitivities of the team members—namely, external evaluators—merit the focused study. This is a suggestion for future research.

As the process of EES is being resumed after the interruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the more descriptive data characterizing the most frequent areas for improvement and strengths identified in this third cycle may prove helpful to guide schools’ action in preparation for evaluation. We believe these data are of significant practical value to schools.

The chronological tendencies identified require further analysis as new reports will soon be published, which can verify or question these results. The fact that few reports were produced during the first two years of implementation of this cycle of EES also limits our ability to conclude from this analysis. Still, some emergent themes such as equity and inclusion, or conversely the need to reduce asymmetry in results, are promising as they are quite expressive and aligned with a broader policy.

Legal Documents

Law-Decree No. 54/2018 of 6 July. https://www.dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/EEspecial/dl_54_2018.pdf.

Law-Decree No. 55/2018 of 6 July. https://files.dre.pt/1s/2018/07/12900/0292802943.pdf.

Dispatch No. 6478/2017 of 26 July. https://dge.mec.pt/sites/default/files/Curriculo/Projeto_Autonomia_e_Flexibilidade/perfil_dos_alunos.pdf.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.igec.mec.pt/PgMapa.htm.

Author Contributions

FS: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, supervision, and project administration. FS, SH, AM, and MA: validation and writing—review and editing. FS, SH, AT, AM, and MA: writing—original draft preparation. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript was funded by national funds through the FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., in the scope of project PTDC/CED-EDG/30410/2017, and of the projects UIDB/04372/2020 and UIDP/04372/2020.

Conflict of Interest

SH and AM currently collaborate with the General Inspectorate of Education and Science as the elements of EES teams. No financial incentives affected the research process.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Afonso, N. (2000). “Autonomia, avaliação e gestão estratégica das escolas públicas,” in Liderança e Estratégia nas Organizações Escolares, Orgs J. Costa, A. Mendes, and A. Ventura (Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro), 201–216.

ASHA (2018). Ethics in Research and Scholarly Activity, Including Protection of Research Participants. Rockville, MD: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association.

Ball, S. (2015). Education, governance and the tyranny of numbers. J. Educ. Policy 30, 299–301. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2015.1013271

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Ball, S. J., and Bowe, R. (1992). Subject departments and the “implementation” of national curriculum policy: an overview of the issues. J. Curric. Stud. 24, 97–115. doi: 10.1080/0022027920240201

Bassey, B. A., and Owan, V. J. (2019). “Ethical issues in educational research management and practice,” in Ethical Issues in Educational Research Management and practice, (Chennai: PEARL PUBLISHERS), 1287–1301. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.11785.88161

Conselho Nacional de Educação[CNE] (2008). Parecer Sobre Avaliação Externa de Escolas. Lisboa: Conselho Nacional de Educação.

Correia, A. P., Fialho, I., and Sá, V. (2015). A autoavaliação de escolas: tensões e sentidos da ação. revista de estudios e investigación en psicologia y educación, Vol. Extr. 10, 100–105. doi: 10.17979/reipe.2015.0.10.535

Dooly, M., Moore, E., and Vallejo, C. (2017). “Research ethics,” in Qualitative Approaches to Research on Plurilingual Education, Orgs M. Dooly and E. Moore (Voillans: Research-publishing), 351–362.

Ehren, M. C. M., and Shackleton, N. (2016b). Mechanisms of change in Dutch inspected schools: comparing schools in different inspection treatments. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 64, 185–213. doi: 10.1080/00071005.2015.1019413

Ehren, M. C. M., and Shackleton, N. (2016a). Risk-based school inspections: impact of targeted inspection approaches on Dutch secondary schools. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 28, 299–321. doi: 10.1007/s11092-016-9242-0

Ehren, M. C. M., and Visscher, A. J. (2006). Towards a theory on the impact of school inspections. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 54, 51–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00333.x

European Education Culture Executive Agency Eurydice, De Coster, I., Birch, P., Czort, S., Delhaxhe, A., and Colclough, O. (2016). Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe, Publications Office. Luxembourg: Publication office of European Union.

Fialho, I., Saragoça, J., Correia, A. P., Gomes, S., and Silvestre, M. J. (2020). “O quadro de referência da avaliação externa das escolas, nos três ciclos avaliativos, no contexto das políticas educativas vigentes,” in Avaliação Institucional e Inspeção: Perspetivas Teórico-Conceptuais, eds J. C. Morgado, J. A. Pacheco, and J. R. Sousa (Porto: Porto Editora), 63–100.

General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC] (2018a). Terceiro Ciclo de Avaliação Externa das Escolas. Quadro de Referência. Disponível em. Lisboa: IGEC. https://www.igec.mec.pt/upload/AEE3_2018/AEE_3_Quadro_Ref.pdfConsultadoa02dedezembrode (accessed February 1, 2022).

General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC] (2018b). Terceiro Ciclo da Avaliação Externa das Escolas. Metodologia. Disponível em. Lisboa: IGEC.

General Inspectorate of Education and Science [IGEC] (2019). Terceiro Ciclo da Avaliação Externa das Escolas. Âmbito, Princípios e Objetivos. Lisboa: IGEC.

Gray, A. (2014). “Supporting school improvement: the role of inspectorates across Europe,” in in Proceedings of The Standing International Conference of Inspectorates, (Brussels).

Kuckartz, U., and Radiker, S. (2019). Analyzing Qualitative Data with MaxQDA. Text, Audio and Video. Berlin: Springer.

Li, R. R., Kitchen, H., George, B., Richardson, M., and Fordham, E. (2019). “oecd reviews of evaluation and assessment in education: Georgia,” in OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, (Paris: OECD Publishing), doi: 10.1787/94dc370e-en

Mainardes, J. (2006). Abordagem do ciclo de políticas: uma contribuição para a análise de políticas educacionais. Educ. Soc. 27, 47–69. doi: 10.1590/s0101-73302006000100003

Morgado, J. C. (2020). “Introdução,” in Avaliação Institucional e Inspeção: Perspetivas Teórico-Conceptuais, Orgs J. C. Morgado, J. A. Pacheco, and J. R. Sousa (Porto: Porto Editora), 7–12.

Moura, E., Ramos, R., Simões, S., and Li, Y. (2021). “Técnica de análise de conteúdo: uma reflexão crítica, in costa,” in Reflexões em Torno de Metodologias de Investigação – análise de dados, Vol. vol. 3, Orgs A. P. Moreira and P. Sá (Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro), 45–60. doi: 10.34624/dws0-6j98

Mouraz, A., Fernandes, P., and Leite, C. (2014). Influências da avaliação externa das escolas no desenvolvimento de uma cultura de autoavaliação. Rev. Port. Investigação Educ. vol. 14, 67–96.

Mouraz, A., Leite, C., and Fernandes, P. (2019). Between external influence and autonomy of schools: effects of external evaluation of schools. Paidéia 29:e2922. doi: 10.1590/1982-4327e2922

OECD (2013). “synergies for better learning: an international perspective on evaluation and assessment,” in OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, (Paris: OECD Publishing).

Pacheco, J. A., Morgado, J. C., Sousa, J., and Maia, I. B. (2020). “Avaliação externa de escolas: quadro teórico-conceptual no contexto metodológico de um estudo nacional,” in Avaliação Institucional e Inspeção: Perspetivas Teórico-Conceptuais, Orgs J. C. Morgado, J. A. Pacheco, and J. R. Sousa (Porto: Porto Editora), 13–62.

Pacheco, J. A., Seabra, F., and Morgado, J. C. (2014). “Avaliação externa. Para a referencialização de um quadro teórico sobre o impacto e os efeitos nas escolas do enino não superior,” in Avaliação Externa de Escolas: Quadro Teórico/Conceptual, Orgs. J. A. Pacheco (Porto: Porto Editora), 15–55.

Quintas, H., and Vitorino, T. (2013). “Avaliação externa e auto-avaliação das escolas,” in Escolas e Avaliação Externa: um Enfoque Nas Estruturas Organizacionais, Orgs D. Craveiro, H. Quintas, I. Rufino, J. A. Gonçalves, P. Abrantes, S. C. Martins, et al. (Lisboa: Editora Mundos Sociais), 7–25.

Seabra, F., Mouraz, A., Henriques, S., and Abelha, M. (2021). A supervisão pedagógica na política e na prática educativa: o olhar da avaliação externa de escolas em Portugal. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 29, 1–27. doi: 10.14507/epaa.29.6486

Keywords: external evaluation of schools, school improvement, documentary analysis, strengths, improvement opportunities, school autonomy

Citation: Seabra F, Henriques S, Mouraz A, Abelha M and Tavares A (2022) Schools’ Strengths and Areas for Improvement: Perspectives From External Evaluation Reports. Front. Educ. 7:868481. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.868481

Received: 02 February 2022; Accepted: 07 March 2022;

Published: 11 April 2022.

Edited by:

David Pérez-Jorge, University of La Laguna, SpainReviewed by:

Jose Luis Ramos Sanchez, Universidad de Extremadura, SpainKonstantinos Karras, University of Crete, Greece

Copyright © 2022 Seabra, Henriques, Mouraz, Abelha and Tavares. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Filipa Seabra, RmlsaXBhLnNlYWJyYUB1YWIucHQ=

Filipa Seabra

Filipa Seabra Susana Henriques

Susana Henriques Ana Mouraz

Ana Mouraz Marta Abelha

Marta Abelha Ana Tavares1

Ana Tavares1