- College of Health and Life Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham, United Kingdom

The Higher Education attainment gap between BAME students and their White peers is well documented. The cause of this gap is multifactorial, and there is a need to understand contributing factors to support the design of meaningful interventions. This study aimed to probe student and staff understanding of what contributes to the attainment gap and to collect feedback on how to reduce it. Qualitative data were collected from 110 STEM students (95% BAME and 75% female) and 20 staff (70% BAME and 80% female) from Universities in the West Midlands and London via one-to-one interviews and focus groups. Questions were developed across themes of support, inclusivity, and development. Transcripts were subjected to inductive and deductive thematic analysis. Key findings included: the need for cultural awareness and representation within student support services and pastoral care provision and tailored support for students who were the first in their families to attend university. Students also felt the academic staff disproportionally represent their backgrounds, leading to a sense of not belonging amongst BAME students. BAME staff felt like tokens for diversity and reported having higher workloads than White staff, the social drinking culture felt isolating, participants felt that all staff should engage with cultural/religious training and diversity of academic staff should be improved through inclusive recruitment practices and mentoring. The results highlight the need for access to academic and pastoral support that is culturally sensitive to all backgrounds.

Introduction

Existing literature uses a variety of terms to address the issue of academic disparity. Most notably, terms like the learning gap, which refers to student outputs, the difference in the relative performance of students in comparison to their expected performance and, the opportunity gap which refers to student inputs—the inequitable distribution of resources and opportunities. Unequivocally, the two terms are interwoven and are not typically isolated or passing events, but observable and predictable trends that remain relatively stable and enduring over time. Educational performance and attainment disparities may appear in a wide variety of data sets, including but not limited to, university admission, absenteeism, dropout, and completion rates (Dualeh, 2017; Universities UK, and NUS, 2019). However, the most discussed is the attainment gap, and at the heart of the discussion is the BAME group who are at the receiving end of the discrimination. The attainment gap identifies BAME students as underachievers in comparison to their white peers. A vast literature has identified differences in socioeconomic status, minority status, disproportionate representation, and ethnocentric influences as causative factors in the establishment and persistence of the attainment gap (Stegers-Jager et al., 2011; Mowat, 2017; Panesar, 2017).

The work of Chmielewski reports, that academic attainment disparity in science subjects is strongly correlated to parental education, parental occupation and the number of household books (Chmielewski, 2019). There also exists a wealth of literature that suggests globalization has led to a larger share of immigrant students enrolled on courses, who generally perform less well in comparison to native students (Czaika and Haas, 2015; Bound et al., 2021). More specifically, there exists considerable variation in household expenditure on school tuition and private tutoring. Consequently, students are segregated at an early age into private and public schooling, with the former more likely to have better academic outcomes. The work of Miri Song reports that individuals identifying as a minority status are more likely to experience feelings of social isolation, prejudice, and discrimination (Song, 2020). The effects of minority status have been reported to negatively impact mental health, leading to an increased perceived stress score and depressive symptoms. These two factors are known to contribute to earning potential and academic progression, thus, the attainment gap (Everett et al., 2016; Panayiotou and Humphrey, 2018). The sum of previous factors leads to a lack of BAME individuals holding academic positions in Higher Education institutes. Disproportionate representation of ethnic minorities in academic roles has previously been described as a causative factor in limiting an institution’s capability to address the attainment gap. This hinders the ability of BAME students to envisage careers in related fields and is a source of demotivation (Smith, 2016).

It is very difficult to isolate a single reason behind the attainment gap, with academic research providing contrasting narratives. The work of Cannella and Koro-Ljungberg describes the integration of capitalism, profiteering, and corporatization of Higher Education as neoliberalism. Consequently, students are perceived as consumers and HEIs as service providers (Cannella and Koro-Ljungberg, 2017). Therefore, we witness a shift from prize learning to increasing efforts of HEIs becoming reactionary to the job marketplace. Critics of neoliberalism argue that neoliberal practices exacerbate, rather than mitigate, social inequalities. HEIs have forsaken their transformational leadership and adopted a transactional approach, leading to the reduction or removal of safety nets, historically provided by HEIs to support vulnerable students (Wilkesmann, 2013).

Furthermore, by failing to acknowledge structural forms of oppression, neoliberalism practices assert that it is individual failures rather than systemic inequality that led to attainment disparities. This ideology has been widely recognized as the “deficit model,” justifying the inequalities experienced by BAME students by putting the blame squarely on perceived lower entry grades, poorer socio-economic circumstances, and the lack of cultural/moral resources necessary to succeed without support from the dominant society (Gillborn, 1997). According to the deficit model, students belonging to marginalized groups exhibit a reduced ability to integrate into university culture, are more likely to be dissatisfied, are less prepared and/or hold unrealistic expectations (Andall-Stanberry, 2017). Circumventing the widespread adoption of the deficit approach is of paramount importance. In essence, deficit thinking allows generalizations about students to be made, which translates directly into internalized racism by strengthening stereotypes in the minds of educators, policymakers, and students themselves (McNamara and Coomber, 2012). This leads to BAME students accepting racist views by internalizing negative attitudes toward themselves, which may include the notion that they are not as intelligent as their white counterparts (Weissglass, 2004).

HEIs in the United Kingdom are becoming increasingly diverse. More specifically, minority students make up the majority within institutes situated in the Midlands and London. Under such circumstances, the need to counteract deficit ideologies with cultural competence is a necessity. When senior leadership approaches achievement gaps through the lens of cultural proficiency, they delve into underlying causes that may be unique to each demographic or cultural group (Goe et al., 2008). Culturally responsive educators develop learning environments that value diversity and promote civic-mindedness. The net result is the establishment of an enriched curriculum and equity in academic attainment (Goe et al., 2008). Developing cultural competence amongst higher education staff could potentially help reduce attainment disparities. A better understanding of the issues which affect BAME cohorts will result in an empathic approach toward supporting students and eradicate deficit thinking.

Academic environments often harbor discriminatory behavior and this is evidenced within the literature. Both, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have provided compelling evidence to show the severity of the problem. The work of Boliver (2016) documented that only 36% of BAME applicants to Russell Group universities were offered places, compared to 55% of White applicants between 2010 and 2016. Statistics from the Equality Challenge Unit (ECU) United Kingdom 2017, reported 77.1% of white students received a first or 2:1 compared with 61.7% of BAME students in England. Stratifying this statistic for specific ethnicities reveals, that 70% of Chinese, 65% of Asian and 50% of Black students received a first or 2:1. The ECU goes on to report that 7.8% of BAME leavers were unemployed 6 months after qualifying, compared with 4.3% of white leavers. Furthermore, 61.2% of White leavers were in full-time work compared with 54.8% of BAME leavers, which highlights the forthcoming implications on prospects and career development (Berry and Loke, 2011). Allen (2017) comments that academic institutes are very capable of nurturing environments that foster inequality. The fact that students who come from marginalized groups based on race, sexuality, and social and economic factors, have more negative experiences in the education system than White students is evidence of this statement (Allen, 2017).

Wong (2015) recognizes the role of educational institutes in perpetuating the segregation of BAME students. His findings document that segregation begins as early as primary education, with BAME students making up the majority in special education classes and the minority in gifted and talented classes (Wong, 2015). This disparity is detectable at HEI and has been underpinned by the critical race theory (CRT). A view that race is not determined by biological or geographical influences instead is socially constructed and functions to maintain the interests of the white population that established it (Allen, 2017). Evidence derived from the 2017 Equality and Human Rights Commission found that 25% of BAME students had experienced racial harassment. The harassment manifested in the form of microaggression, exclusion, and exposure to racist material. Although most students confirmed their harassers were students, a large number also confirmed it was a member of academic staff (Equality Human Rights Commission, 2017).

The Office for Students issued a warning to HEIs in the United Kingdom revealing that institutes were either failing to acknowledge the attainment gap or measures put in place to tackle the disparity were ineffective. For example, in a predominantly White institution (PWI), simply working toward increasing the number of students of color enrolled is an insufficient goal if institutional change is a priority. There is, however, evidence of effective practice, most recently demonstrated by Kingston University London, which has been recognized as the sector-wide champion in mitigating attainment gaps by incorporating the closure of the attainment gap into a key performance indicator. It can be postulated that HEIs should be examining campus climates and enhancing efforts to have a culturally competent workforce as a more effective way of becoming more diverse and inclusive (Gasman et al., 2015). A popular mechanism to contrive meaningful data is to put the onus on students themselves.

The work of Flodèn recognizes student feedback as a critical performance indicator and highlights how experienced members of staff can utilize student feedback to stimulate meaningful change in academic legislation and facilitate development (Flodén, 2016). However, while the student experiences are instrumental in tackling attainment disparities, existing literature seldom acknowledges the views of BAME staff members. It is well documented that there is a distinct lack of BAME representation in HEI (Arday et al., 2022). Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) reveals only 17 per cent of academic staff are from BAME backgrounds, which falls to 10 per cent for professors. Consequently, a majority of the individuals responsible for implementing strategic initiatives to tackle attainment disparities have never experienced the issues and concerns affecting the students (HESA Staff Statistics, 2018; Mantle, 2018).

This investigation consists of three objectives. The primary objective was to understand the role of cultural competence and its contribution to the persistence of the attainment gap. The study protocol questions an ethnically representative sample of students and staff from West Midlands and London based institutes, areas synonymous with being ethnically diverse. The secondary objective of this study was to probe student perspectives on university support services and their effectiveness in mitigating attainment disparities, and finally to obtain valuable feedback on how the issues surrounding the attainment gap, could be better addressed. This approach reinforces students’ and staff’s commitment to institutional development and could potentially provide objective suggestions for improvement.

Materials and Methods

Design

Qualitative data was collated via audio-recorded interviews and focus groups, with students and staff from West Midlands and London based universities to better understand factors facilitating attainment disparities as well as explore their perceptions of institutional initiatives currently employed to tackle attainment differences between White and BAME students. A qualitative, non-hypothesis-driven approach was adopted. This approach limits the interference of personal opinions/experiences and prevents internal biases from misconstruing student views. By not assuming links between student experience and academic attainment, but instead judging the data on its merits, prevents the research facilitators from directing the conversations during focus groups and instead enhances knowledge discovery. As a result, this method helps to obtain a deeper and truer understanding of participant experiences. Students were given the option to participate in one-to-one interviews or focus groups. This offered participants flexibility due to the sensitivity of the research topic and the sharing of personal circumstances and experiences. All staff interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis, allowing staff members to discuss their experiences in confidence.

Participants

In total, 110 full-time students enrolled on STEM degree programs, currently studying in their final year, participated in the study. An invitation to participate was emailed to students, with some recruited through direct contact with a member of the research team and via the local BAME staff network that advertised the research. Participants included 28 males and 82 females, with a mean age of 20 years (range: 20–24 years).

The participants described themselves as South-Asian (68), Black (29), Arab (8) and White (5). English was an additional language for 88 participants. 20 staff members, occupying both academic and administrative roles, were emailed specifically for having teaching-focused roles and/or direct contact with students. The staff cohort consisted of 4 male and 16 female members who identified themselves as South Asian (9), Black (5), and White (6). Furthermore included a range of roles, from graduate teaching assistants to professors. No incentives were offered to staff or students for taking part. Interested participants were sent an information sheet detailing the background of the research and its potential impact, their freedom to withdraw at any time, and the confidential nature of the interviews and focus groups. Those agreeing to participate were asked to complete a written consent form.

Procedure

Ethical approval was applied for and approved by Aston University’s internal ethical committee (ethics number ETMEd19001). Following approval, email invitations were sent to final year students. Interested participants were invited to attend a focus group meeting, which took place on campus at a convenient time for the students. The research team consisted of one male academic member of staff, one female member of technical staff and five female student members, all of whom identify as BAME. Focus groups were conducted by the student members of the research team and adhered to maintaining ethnic homogeneity in a bid to facilitate dialog amongst participants, an approach which has been documented to be advantageous over heterogeneous groups (Greenwood et al., 2014). Staff interviews were conducted by the academic members of staff from the research team. Questions for discussion during the focus group were pre-approved by the ethics committee. All questions were developed to synchronize with the objectives of the study and then distilled into specific themes. The primary objective was to understand the role of cultural competence within HEI and questions addressing this objective were categorized under the theme of inclusivity. The next objective was to probe student perceptions of academic services and their effectiveness in tackling attainment disparities, and questions probing this were categorized under the theme of support. Finally, questions were designed to obtain constructive feedback from participants to help devise strategies aimed at reducing attainment gaps. Such questions were categorized by the theme of development.

This approach was underpinned by basic needs according to self-determination theory (SDT) (Deci et al., 2001). A theory that proposes three basic human needs: Autonomy refers to the need to feel that one’s behavior and resulting outcomes are self-determined, as opposed to being influenced by external forces. Much in line with how students seek control over their academic progression. Competence refers to the need to feel capable of performing. Relatedness refers to the need to feel cared for by other people, for example, by personal tutors and other academic staff. SDT stipulates all three needs must be fulfilled for psychological well-being to occur and has been used to determine motivation and psychological adjustment in the working environment (Deci et al., 2001). The presence of these basic needs is a key predictor of whether individuals will exhibit increased intrinsic motivation toward learning, and how they experience relatedness through staff interactions and has been documented to correlate with improved mental health (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009). By being better aware of interventions that could motivate and encourage students, a foundation of SDT provides the ideal framework for establishing the final theme of further development. Collating student feedback via questions underpinned by themes of SDT (autonomy, competence, and relatedness) will facilitate the reverse-engineering of recommendations to address student concerns and development.

Example questions were:

• How would you describe the support services available to you, and how likely are you to use these services? (support)

• What are your views on the ethnic profile of your department? (inclusivity)

• How can the university tailor student support with consideration of students’ ethnicity? (development)

The questions for staff covered awareness of discrimination toward students or staff, knowledge of different learning patterns amongst students from BAME backgrounds, and suggestions for improvements in tackling attainment disparity. Student focus groups lasted approximately 60–90 min, and interviews with staff lasted between 20 and 30 min. Transcripts from both interactions were transcribed verbatim by the facilitators of the research as soon as possible after the focus groups/interviews to prevent losing the essence of the conversations.

Analysis

Focus group transcripts were analyzed using thematic analysis (TA) and subjected to both inductive and deductive analysis, in a bid to better understand the experiences of students and staff (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The transcripts were screened by the first author to initiate the familiarization phase (phase 1). Transcripts were then read, re-read, and annotations of emerging ideas or similarities between student experiences were identified. In phase 2, a coding system was established to help identify and organize data into groups, by labeling similar narratives, better allowing the author to determine themes. Themes were generated within the data using the approach adopted by Sims (1998).

The focus group chair collated dissenting views and noted elements of acquiescence. This helped establish how many members provided substantive statements or examples of discussion that support the consensus view.

These views were combined into a matrix and divided to help identify positive and negative viewpoints. Which effectively recorded the level of agreement and disagreement within the group. This allowed the data to be segregated into areas where students perceived discrimination and areas where students were happy with their university environment. This approach formed the basis of the next phase, where key information was congregated into coherent and meaningful patterns. Areas where the majority of students agreed or disagreed scored highly on either end of the spectrum and were incorporated into themes. Using a matrix helped filter out areas of discussion that were deemed unimportant by the study participants and helped build strong themes that were aligned to the key objectives of the study. This was achieved by identifying positive and negative responses corresponding to inclusivity on campus, the effectiveness of student support services, and areas of improvement. The lead author then analyzed these themes extensively, reviewing and revising to ensure an accurate depiction of the focus groups as well as establishing meaningful data cohesion within each theme and its corresponding objective. Furthermore, as a final measure of legitimacy and to confirm that the findings accurately represented the views of staff and students taking part in the study, the results section was sent to participants.

Results

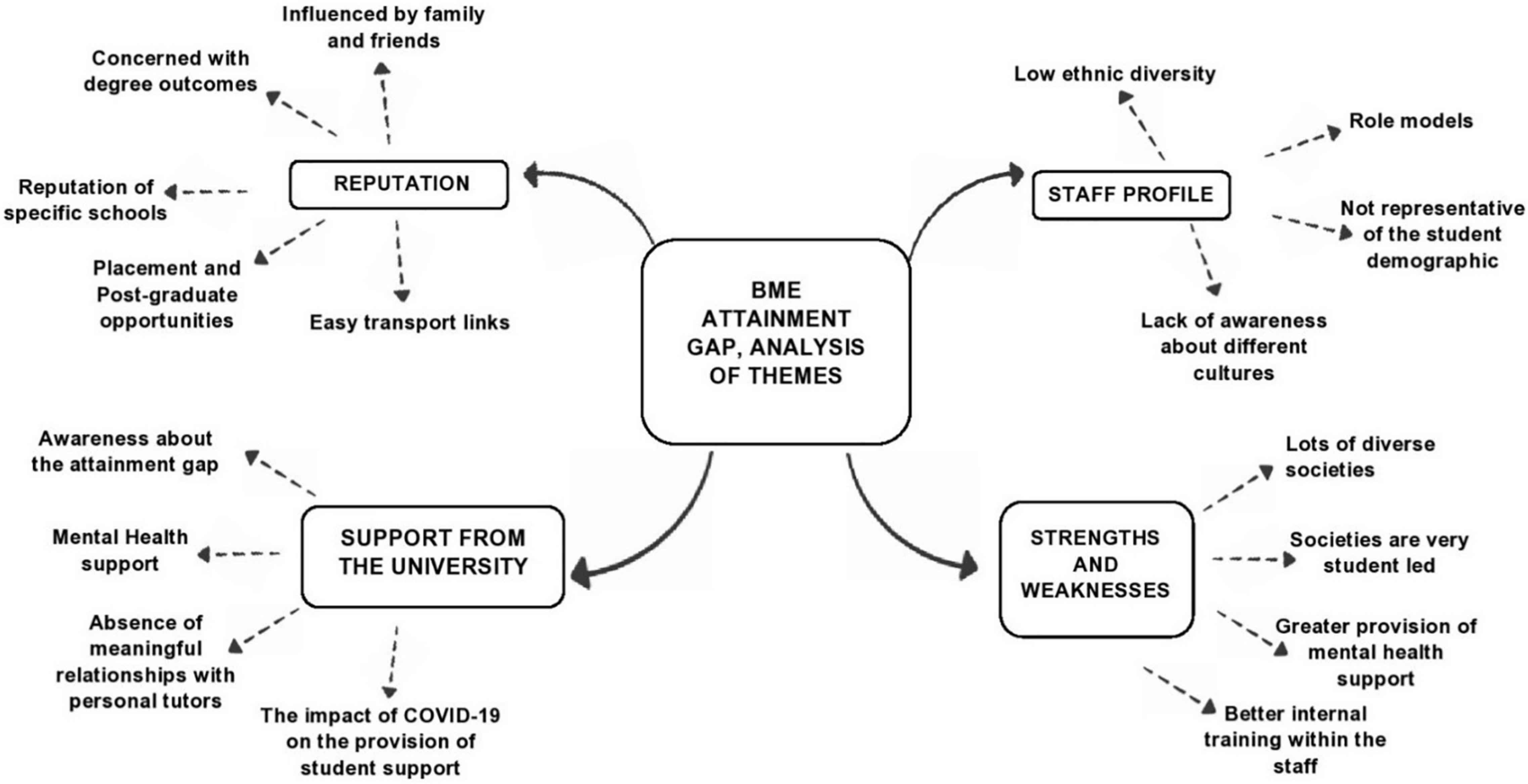

Common themes presented by staff and students were summarized using a mind map of prominent ideas (Figure 1). Key themes were identified and distilled into questions correlating to the study objectives, which probed the inclusive nature of the department, quality of student support and finally what initiatives could be implemented moving forward to address the attainment gap. Within the three themes, firstly the student response will be considered and then the academic point of view.

The Inclusive Nature of University Departments

Student Views

Whilst students agreed their respective university campuses are inclusive, with regards to societies for different ethnicities, prayer room facilities and Student Union activities. This element of inclusivity was restricted at a social level and did not transcend to the professional level. 63% of participants were unaware of the attainment gap and all participants stated they were disappointed at the lack of representation of BAME staff members in teaching-focused roles.

“In my experience, I feel staffs have pre-conceived notions about students, particularly regarding our academic background. I did BTEC for example and struggled a lot in the first year because it was just assumed that I had sat exams and knew things other students did, when I didn’t. It’s not really an inclusive approach to assume we all had conventional backgrounds; I believe this to be a major contributor to attainment gaps.”

“I pretend to understand my tutor’s jokes. I see other students laughing so I just join in… she brings up cultural references, or her white background all the time and I never had that upbringing, I can’t relate so my interactions are considerably shorter with my tutor than some of my peers. It’s probably led to a weaker relationship with her.”

Students felt staff had prior assumptions about BAME students with regards to both academic attainment and social experiences. In the case of BAME students, this led to a feeling of isolation, superficial relationships, and an integral factor in establishing a non-inclusive environment and the attainment gap. Whereas non-BAME students harbored stronger relations with staff due to relatedness. Students attributed this primarily to the ratio of BAME to white staff members and described this to be abnormal.

“I feel like there is diversity in students at uni… across all degrees, and the range of academic staff profile should aim to match this, but I feel that it doesn’t” I would like to see more people of color like me, as it would encourage me to work harder, to obtain an achievable goal.

Participants openly discussed that they felt recruitment at HEI followed a structure of hierarchy as it was evident BAME members were being recruited in non-academic roles and statistics which contribute to BAME recruitment may not account for the level of occupation. Students correlated this to being unable to envisage a career in academia, hence a reduced motivation to succeed, and consequently poorer academic outcomes.

“I think the ethnic profile of at my university, particularly in the Biosciences department is extremely skewed. The majority of academic staff are white. Ethnic minorities are largely represented by individuals in technical, cleaning and catering roles. This is extremely discouraging for me as I am unable to see myself becoming a scientist. I feel like this career is not meant for me and maybe I chose the wrong course, maybe other BAME students feel this way and is why we have poorer outcomes.”

Students were asked if they would feel more comfortable speaking to an ethnic member of staff and 55% of participants agreed this would be beneficial, as they currently felt unable to openly discuss personal problems with a white academic. Furthermore, they felt BAME concerns would not be understood by white academics and would not resonate with them as issues that could contribute to BAME students performing poorly.

“The reason why the problem (attainment gap) exists, is quite obvious. There is a lack of cultural awareness, we claim to be inclusive, but we are not. My tutor still cannot pronounce my name properly, it’s been 4 years. How am I supposed to discuss my personal problems when he (tutor) doesn’t even know me? At times I’ve had so much going on and it has really affected my ability to study and no one to discuss it with. Having BAME members of staff, who understand us better is an obvious solution.”

Again, the ethnicity of an academic member of staff may not be a mitigating factor for non-BAME students to seek support. This was evidenced by the non-BAME participants.

“I don’t feel it would make a difference to me, I have spoken to several [members of staff] and I am comfortable with all. However, I could understand that some students would feel more comfortable speaking to a tutor of the same ethnic background.”

Students spoke at length when asked to summarize if they felt the university harbored an environment inclusive of all ethnicities. Students felt institutional inclusivity in professional regard was unsatisfactory and some of it stemmed from the commercialization of education. Others suggested outright bias and inherent discrimination against BAME students was the prominent reason for the attainment gap.

“No, I feel that there are many opportunities in which our university could educate students and staff, in aiming to eliminate the attainment gap but they do not and it’s kind of brushed under the carpet. I don’t think it bothers them. We pay our fees, and they see us as customers, but they see non-BAMEs as students. It’s not surprising why they (non-BAME) perform better than we do.”

Students claimed the university seemed to be in control of the issue, but a deep-rooted analysis of the environment would reveal otherwise. Others felt archaic teaching practice and how older generation academics were not aware of political correctness were at fault.

“One of my lecturers said, ‘there will be a lot more jobs once the foreigners leave and Brexit goes through.’ You can’t say things like that. It isolates the non-British students and demonstrates that these old fashion views are seeping into teaching and assessment.”

“Our environment is not inclusive at all. It’s happened to me countless times, where I’ve put my hand up in a practical and the lecturer walks right past to help a group of white students…. that’s another problem, we are told to sort our own groups out, so we naturally stick to our mates. Diversifying the practical groups will allow us to mix with different people and learn from each other, whilst getting an equal share of attention.”

Staff Views

Staff members both academic and non-academic echoed the responses from students and understood the need to diversify academic departments. Most accepted they were aware of instances where staff exhibited pre-conceived notions regarding BAME students.

“Sometimes students come into university and bring community prejudices with them. Maybe if they reached out, they would realize we are not that different….although I have known staff to pre-judge students based upon their ethnicity. For example, it is common for white academics to think Asian males are likely to join the family business and females to get married and not further pursue education or a career. Maybe these notions are the reason behind the attainment gap.”

Other BAME academics resonated that there exists an environment that caters to the majority and does very little for marginalized groups.

“I get the feel that HEI belongs to one set of people—those who are whites which somehow seem to encourage an attitude of entitlement. At the same time, BAMEs have a sense of un-belonging. What universities do through EDI is to seek to develop a feeling of belonging which reinforces that BAMEs do not belong, this is bound to have negative connotations of prejudice? If they feel unwelcomed, they will not do as well.”

90% of staff participants in both academic and non-academic roles agreed that institutional discrimination extended beyond students and affected staff. Whilst non-BAME staff discussed gender-based discrimination, BAME members of staff felt that they had been racially discriminated against, an area that receives very little attention.

“I believe as a BAME woman I have to work twice as hard as my white colleagues to even get a look in and would be subject to more scrutiny if I was to make a mistake, this has hindered my progression in my career. I imagine our students endure the same and is the main reason why they are subjected to attainment disparities.”

Other BAME staff also corroborated the theme of having increased workloads and felt as if they were less integral to departmental culture but were at the forefront of showcasing diversity and equality.

“I do feel like I’m one of the token BAME individuals within the department that get wheeled out at every opportunity to showcase diversity and inclusivity. I’ve definitely seen this with BAME student reps at open days. It’s a tick box exercise, I’m rarely invited to the pub but I’m always included on public engagement events. This discriminatory mindset must flow into academic practice and has to be a contributing factor to the attainment gap.”

Staff members identifying as Muslim reinforced the notion that social events involving the consumption of alcohol were plentiful and did not consider their beliefs. These events are organized by non-BAME staff members who are culturally unaware, consequently forming a common ground for isolating both students and staff from integrating into departmental life. A quintessential factor in academic attainment.

“The heavy social drinking emphasis on campus makes team building very difficult. I have been in situations where key decisions were made during work social events, which I could not attend due to my religious beliefs. Of course, these events are organized by non-BAME staff. Muslim students raised the same issue with their non-BAME society reps. It was just laughed off. There is not an inclusive environment for staff let alone students.”

The Quality of Student Support

Student Views

65% of students agreed there were various avenues to obtain support and appreciated the variety of sources.

“We do have a lot (services), the Hub, chaplain, the learning and development center and I feel sometimes students aren’t always aware of them…….and they are helpful, they try their best.”

“I really appreciate how we have prayer rooms, societies and all that. My uni has mentoring schemes too, where we can go for support.”

94% of students felt a lack of culturally specific support was evident and therefore deterred them from availing of the services or the reason why there was a high rate of attrition in engagement. Consequently, were insignificant in tackling attainment disparities.

“Although there are many formal opportunities for support, such as being able to book appointments, library workshops and advice lines etc. I feel like these are all opportunities which touch the surface of emotion. I feel to connect with students at a deeper level, it is very important to be able to empathize with them not just sympathize. The current profile of staff are unable to do this, therefore students just aren’t comfortable speaking to them.”

“For me, this [university service] would not reap benefit of support because the likelihood of me speaking to someone who understands or is familiar with my background is very low. Everyone working there is white, they are not going to understand the difficulty of observing a Ramadan fast while revising or the pressures of an inter-religion relationship.”

The responses indicated a need for universities to better understand cultural issues which are considered important or alarming for BAME students. The lack of cultural support was primarily down to the predominantly white workforce, who were unaware of or fail to recognize the challenges associated with BAME households.

“Not entirely. For broader issues, i.e., mental health, there are support networks in place, however, support for issues that specifically affect certain communities is not currently available. This might discourage students from seeking help and might lead to them suffering in silence because there aren’t people (staff) with the same lived experiences. It’s just not on the universities radar as an issue and it will continue to persist until they hire BAME staff or educate existing non-BAME ones.”

Whilst students expressed that support services could be more considerate of ethnic needs, they also felt that personal tutors ought to play a larger role in providing support. Since students spent time with tutors one-to-one and/or in smaller groups, both environments are conducive to sharing personal issues. Students felt these opportunities could be better utilized to discuss concerns stemming from cultural issues but also to educate students on the attainment gap.

“Our tutorials really should cover these things (cultural issues), I can understand not being comfortable discussing race in large groups but it’s the perfect thing to talk about with your tutor. We should be having healthy conversations around the attainment gap…I don’t know why we don’t, maybe lecturers aren’t comfortable talking about it.”

A few participants highlighted positive experiences, this included students who had a BAME tutor, highlighting the ease of confiding in academic members who shared common ancestry and understood student experiences.

“Easier to talk to someone from the same ethnic background speak to him (personal tutor) openly about my problems without feeling judged and knowing that I’m being understood. My mates struggle to have such conversations with white academics and those that have tried said it was just awkward.”

Staff Views

Members of staff felt, that although a considerable amount of effort and time was spent in providing support for students, there were still vast improvements to be made. Particularly with regards to culturally specific support.

“Yes, we try to. But I don’t think we ‘get’ some of the issues our students face (family pressures, mental health, etc.).”

Staff members also recognized that students who were amongst the first within their household to attend university were more vulnerable and required additional support.

“I think the university should do more for those students who have no family, or close relatives who have been through higher education. Currently, we have no provision or support system for such students. We have just started analyzing TEF (teaching excellence framework) data after our module boards, which covers ethnicities, gender, mature students etc. We really ought to collate attainment data from students who are the first from their family to attend higher education.”

“Many Asian students are the first in their families to attend university and have no point of reference regarding university life, so require considerably more support, we know that it is a problem but we have never acted on it.”

Moving Forward and Development

In all focus groups/interviews, students agreed, that more tailored support for the BAME cohort was necessary and felt, a panel of BAME individuals within higher education could offer a support service.

“The university can provide support in the form of counselors from different ethnic backgrounds that are well versed in the issues that might affect certain ethnicities. It could function as a rota of BAME staff providing support throughout the year. A combination of male and female members could really make it easier for BAME students to open up about their concerns, particularly for Muslim girls as I know there aren’t any role models for us.”

Students also felt that staff education and development would be an equally successful strategy to improve the academic performance of the BAME group. Participants mentioned if staff were well versed with issues deemed problematic to BAME students, they would feel more comfortable discussing their concerns and less apprehensive to engage in discussion.

“Individual departments can train staff members to make them aware of certain issues affecting students from different ethnic backgrounds, in addition to personal tutor training.”

Most participants felt a more entrenched approach was necessary and suggested staff members should be provided with a handbook or should complete a training course that details, the cultural and religious aspects of BAME students.

“I think that staff should educate themselves on different ethnic cultures and religions (as religion can also have an impact on the culture), this will allow them to understand the students’ situation a lot better and as a result, you will see an improvement in student engagement and attainment.”

One potential approach suggested including staff-led sessions to address the BAME attainment gap and for staff to share examples of best practice along with updating students on what measures had been put into place to tackle the attainment gap, as well as present an opportunity for students to raise any concerns.

“I feel they [the university] should create an open space for discussion between students and academics, this could be an open forum like….where we can discuss our concerns and they [the staff] can tell us about what they are doing to resolve our issues.”

The non-BAME participants, similarly, felt less of a change was necessary but called for increased distribution of knowledge regarding the attainment gap as well as an increased presence of BAME members of staff in teaching roles.

“I feel the support at the university is currently very good, maybe a few tweaks can be made in terms of distribution of ethnicity throughout the different courses to have an even spread of students and academics of certain ethnicity.”

Staff Views

Staff unanimously agreed that increasing diversity within recruitment and increased representation of BAME groups would help reduce attainment disparities by bringing about a sense of familiarity and belonging.

“Yes, I feel that more could be done to hire academic staff/support students to develop careers in academia from diverse ethnic groups, specifically from Black British/African/Caribbean groups which are poorly represented. These students have no role models, nothing to aspire to.”

Members of staff also felt the process of diversifying recruitment would require large timescales and a quicker resolve would be to educate existing staff members about the issues which affect BAME cohorts the most.

“The university could train academic staff in these issues or have a dedicated team that BAME students could go to for support. Currently, it seems non-BAME academic staff are unaware how BAME students dealing with these issues can affect their mental health and general wellbeing, as well as their academic performance.”

Both academic and non-academic members of staff agreed that the onus to establish inclusivity and foster a homogenous learning environment is very much on the shoulders of HEI.

“I think mentoring and role modeling is very important, we need to challenge decision-making processes at all levels of the institution to ensure that they are free from bias, the responsibility is very much ours and we should not be looking at our students to come up with solutions to problems which have largely been established by ourselves.”

Discussions further led into the specifics of how HEI can implement changes to develop a more inclusive environment and these suggestions included inculcating diversity into all aspects of campus life.

“Insert their (BAME) culture in the classroom. At all times food and drink sold on the campus should reflect those normally consumed by BAMEs and more BAME heroes and their history should be celebrated in hallways and across campus. Embed inclusivity into the curriculum and open discuss discrimination/bias rather than hiding away from it.”

Discussion

Current literature documents that BAME students are less likely to achieve a higher standard in HEI in comparison to their White peers (Bécares and Priest, 2015). Research has exposed stark differences in student attainment between BAME and non-BAME students (Lessard-Phillips and Li, 2017). Despite the persisting disparity, this apparent and severe inequality has largely been overlooked or ignored. This study aimed to ascertain the role of cultural competence in facilitating attainment gaps. Furthermore, to investigate how the student and staff body at a selection of West Midlands and London based HEI perceived the usefulness of support services available and whether their department harbored an inclusive environment. Finally, what, in their opinion, could be done to improve the disparity from an institutional standpoint?

The data provided herein exhibits, that whilst there were clear areas of good practice that were considerate of the cultural needs of the BAME student body, these were restricted to the social elements of university life. Students stated that this failed to make a major impact/contribution to the reason why they attended higher education. Furthermore, students clearly expressed their disappointment concerning the lack of inclusivity at an academic level, with little to no representation of ethnic groups in teaching. Consequently, there was an element of hesitation to discuss pastoral and academic needs with members of staff, whom students felt would not understand the difficulties they were experiencing. A re-occurring concern amongst students was that academics exhibited a lack of understanding of issues that stem from cultural/religious reasons. This familiarization with how to deal with BAME students translated into a decreased academic performance. Views from BAME staff members concurred with those expressed by BAME students, and they recognized that higher education institutes are very capable of fostering inequality. BAME staff members reported the university experience is tailored for White students, whilst other ethnicities are expected to adjust. This view also transitioned into their journey as BAME academics, evidenced by staff members reporting experiencing invisibility and marginalization.

A novel finding of this research is the realization of the importance of having culturally aware academics and support services at HEIs. Both staff and students agreed that increased knowledge and understanding of diverse backgrounds would help alleviate academic bias. Students suggested the incorporation of diversity training could be inculcated into transferable skills modules for students and mandatory staff training. Students also felt personal tutors could play a larger role in facilitating inclusive conversations. Alves (2019) concluded pastoral tutoring can help raise the attainment gap by positively creating that sense of belonging, with the support of culturally aware academics, students would be empowered to share personal issues.

Although BAME academics within this study rejected the notion presented by the deficit model, identifying BAME students as less focused and determined to succeed, placing the onus of the attainment gap directly on BAME students (Ulysse et al., 2016; Khan, 2019). Staff did feel that students and staff interact with preconceived notions about each other. Students share the opinion that academics are from privileged backgrounds and have forgotten what it feels like to be a student, whilst staff consider the lack of developing meaningful relationships with BAME students is due to student disengagement because of parental coercion, prior grades, and socioeconomic status (Bodycott and Walker, 2000). This view is now contestable as more recent data from the United Kingdom HESA reveals the attainment gap exists even when BAME students obtain better A-levels than white students and if the effects of entry grades and wealth are completely neutralized (HESA Statistics Bulletin, 2020). Another theory, which again derives from the deficit model debates, BAME student attainment is highly correlated to their engagement with campus life. Meeuwisse (2010) attributes a lack of extra-curricular activities and peer-group integration as factors responsible for increased withdrawal rates and generally reduced chance of success amongst BAME cohorts (Meeuwisse et al., 2010).

A report from the Office for Students, titled Understanding and Overcoming the Challenges of Targeting Students from Under-represented and Disadvantaged Ethnic Backgrounds, revealed that students from BAME backgrounds are often less involved in campus life than their White peers, due to personal pressures surrounding employment, the pressure to achieve a first and/or social care responsibilities. The work of Cotton et al., identified why sociocultural backgrounds played a significant role in determining which campus activities appealed to students. The authors report that compared to students from ethnic minority backgrounds, White students spent more time with friends in clubs and bars and were involved in more university-based activities. On the contrary, Black students spent considerably more time in the library, with family, or were involved more in solitary activities. These data are indicative of differences in campus integration (Cotton et al., 2015). It would be irresponsible to encourage BAME students to spend more time in bars to improve their academic performance. Both staff and students belonging to BAME backgrounds extensively discussed the number of social events centered around the consumption of alcohol, which immediately isolates individuals from BAME communities where alcohol is forbidden.

Khambhaitia and Bhopal explain that female students belonging to Indian, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi ethnic groups are more likely to opt for living with their parents than on campus, in comparison to White females. This is largely due to cultural barriers and the view that university campus environments are predominantly White. This is perceived by minority families as a threat to cultural identity and has detrimental implications on degree outcomes (Khambhaita and Bhopal, 2015). As a result, BAME students are often concentrated in large inner-city post-1992 universities. Such institutes are known for their teaching rather than research and are ranked lower in league tables (Dillon, 2011; Bhopal, 2020).

Jessop and Williams reported that BAME students felt they were perceived as inferior to non-BAME students, a view sometimes reiterated by course materials and endorsed by non-BAME lecturers who did not “understand” their backgrounds or the challenges that they faced (Jessop and Williams, 2009). The data revealed that BAME students were facing the brunt of racism embedded in United Kingdom society. This was exemplified by academic staff not necessarily discouraging students but being less empathetic toward them, a finding which was reported by staff within this study.

A proportion of students within this study reported being subjected to racism and feeling a sense of direct discrimination. It has been reported that abuse toward Asian students is rife amongst HEI but is under-presented as most students do not feel comfortable raising the issue and/or are unaware they are being disadvantaged (Pilkington, 2013). Furthermore, HEIs have been hesitant to tackle the issue due to the negative attention it would draw upon the university (Burns, 2019). Remaining oblivious to discrimination is not limited to the sufferers. An observation reported within this study saw the non-BAME participants expressing a rather different higher education experience. An experience where there was a complete sense of fulfillment and very little room for improvement. Claridge et al. conducted a comprehensive qualitative study investigating the attainment gap amongst medical and biomedical science students in a United Kingdom HEI. They report that whilst BAME students were subjected to a lack of informal transfer of knowledge, which directly impacted academic performance, non-BAME students were not isolated from useful academic information (Claridge et al., 2018). This was to a certain extent confirmed by a member of staff. However, White participants had no such complaints and were completely unaware of any such incidents.

It is plausible that BAME students and non-BAME students have a very different student experience, leading to the attainment gap. Because there is no evidence to suggest BAME students spend less time studying or are more likely to skip lectures in comparison to White students (Bunce and King, 2019). Participants in this study suggested that stronger support networks were required, focusing on the BAME student body. Non-BAME staff lack awareness and understanding of issues affecting BAME students and this issue has not been addressed by HEIs. It will be crucial for institutions to provide relevant training on equality, diversity, and inclusion and ensure that staff acknowledge and internalize the importance of challenging racism and discrimination.

Historically, efforts made within HEIs in the United Kingdom to level the playing field have included legislative interventions and equality policies such as The Race Relations Amendment Act (2000), the Athena SWAN Charter (2005), the Equality Act (2010) and the Race Equality Charter (2014). Which have required HEIs to demonstrate their commitment to student attainment, BAME staff progression, and enriching the curriculum. However, the work of Bhopal identifies the implementation of diversity policies as “tick-box” exercises, as well as clever marketing ploys, using multiculturalism to attract more students in an ever-growing global market (Bhopal and Pitkin, 2020). HEIs have been suspected of protecting the interests of white academics and perpetuating white privilege whilst demonstrating an intrinsic failure to make a meaningful impact on inclusion. Policy enactment itself has been recognized as a vehicle to benefit white academics and senior leaders in HEIs. As it is often seen as a means of meeting performance targets, facilitating wider recognition within departments and a pre-requisite for academic promotion (Bhopal, 2018). This view coincides with the theory of interest convergence, a theory that suggests Whites will only seek to advance the cause of racial injustice when they are to mutually benefit from it (Bell, 1980). Bhopal further reports that if white identity and white privilege are not threatened, white groups are supportive of diversity and inclusion programs. Evidence for this statement stems from the disproportionate benefit of the Athena Swan charter to middle-class white women (Bhopal, 2020).

In essence, the performativity of inclusion policies has catered to white academics and organizational interests instead of addressing the racial inequalities experienced by BAME students (Bhopal, 2018). As a result, such policies reinforce privileges and institutional hierarchies. Consequently, the burden of tackling the attainment gap and associated inequalities rest on the shoulders of the few BAME academics found within HEIs. Currently, there are no provisions at the teaching staff level to address the attainment gap in a meaningful way. A major change is required in staff recruitment, with increased representation of BAME academics and a structured pathway to promote existing members. An influx of BAME academics could potentially ease the barrier between staff and student engagement regarding sensitive cultural issues. Whilst, increasing BAME recruitment in HEIs is a very important step, realistically will require substantial change, over a long period. A strategy to yield a long-lasting effect, a lot sooner would be to engage existing academics to foster relatedness and provide a more empathic and open-minded approach. A direct and impactful approach could include mandatory diversity training, which specifically addresses BAME issues.

Relatedness among BAME students could be facilitated by less formal avenues, for example, BAME focused support groups, student voice sessions, and more informal discussions between staff and students. From a social and academic perspective, HEIs can make larger efforts to acknowledge religious festivals whilst accounting for them in academic timetables and should be reflected on staff calendars (Bashir et al., 2021). UCL published literature in favor of decolonizing the curriculum. The diversification of academic practice was recognized by members of staff who encouraged students to reflect on their own experiences and identities (Hussain, 2016). This open-minded and autonomous approach could potentially be embedded into key skills modules, in conjunction with mental health. The current study is not without its limitations. Most student interactions took place during the pandemic and under lockdown restrictions. This unequivocally would have affected students’ perceptions regarding student support. There are also very few students who took part in the study who identified as being from a white background. Collating testimonies from white students would provide a holistic view of the situation and prevent the authors from outlining measures that could positively discriminate against non-BAME students.

Conclusion

HEIs possess the authority, financial capability, and personnel to provide a learning experience that fosters academic development and caters to students from all cultures, backgrounds, and religious beliefs. This academic goal has been falling short for numerous years and continues to do so, as BAME students are still being failed by the system. To turn the tide on academic disparity, universities will have to undergo a hierarchic transformation. Senior management groups within HEIs must shift the emphasis from policymaking to establishing objectives to decrease discrimination and report on quantifiable outcome measures. The ideology of using diversity to meet pre-requisites of academic governing bodies or using diversity as an attractive marketing campaign is implicated in maintaining pre-existing racial inequalities. Academics must commit to addressing the marginalization of students and tailoring curriculum content to reflect a diverse student body. This can be manifested by championing modules that explore a variety of cultures and provide safe spaces for discussing racism. There exists a need to raise awareness of the importance of cultural competence among students and staff. More importantly, there needs to be a systematic approach to providing equality and diversity training for staff. Enhancing cultural competence/awareness amongst academics will facilitate stronger relationships between students and staff. The increased recruitment and/or promotion of existing BAME academics exhibits an inclusive environment and provides student bodies with relevant role models. The net effect helps both staff and students to collectively overcome barriers around discrimination and reduce attainment disparities.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Aston University Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

KR contributed to the conception and design of the study and wrote the manuscript. FB supervised focus groups. AB and HB read and approved the submitted version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ayesha Hanif, Ariana Mugore, Deepa Mistry, Neda Nadilouei, and Rabia Mehmood for their input into and assistance with the study.

References

Allen, M. (2017). The relevance of critical race theory: impact on students of color. UERPA Educ. Res. Policy Ann. 5, 33–42.

Alves, R. (2019). Could personal tutoring help improve the attainment gap of black, Asian and minority ethnic students? Blended Learn. Pract. 66–76. Available online at: https://www.herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/246691/BLiP-Spring-2019-Final-Published.pdf

Andall-Stanberry, M. (2017). Aspiration and Resilience - Challenging Deficit Theories of Black Students in Higher Education. Unpublished Doctorate Thesis.

Arday, J., Branchu, C., and Boliver, V. (2022). What do we know about black and minority ethnic (BAME) participation in UK higher education? Soc. Policy Soc. 21, 12–25. doi: 10.1017/S1474746421000579

Bashir, A., Bashir, S., Rana, K., Lambert, P., and Vernallis, A. (2021). Post-COVID-19 adaptations; the shifts towards online learning, hybrid course delivery and the implications for biosciences courses in the higher education setting. Front. Educ. 6:711619. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.711619

Bécares, L., and Priest, N. (2015). Understanding the influence of race/ethnicity, gender, and class on inequalities in academic and non-academic outcomes among eighth-grade students: findings from an intersectionality approach. PLoS One 10:e0141363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141363

Bell, D. (1980). Brown V board of education and the interest convergence dilemma. Harvard Law Rev. 93, 518–533. doi: 10.2307/1340546

Berry, J., and Loke, G. (2011). Improving the Degree Attainment of Black and Minority Ethnic Students. London: The Higher Education Academy and Equality Challenge Unit. Available from: https://www.ecu.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/external/improving-degree-attainment-bme.pdf

Bhopal, K. (2018). White Privilege: the Myth of a Post-racial Society. Bristol: Policy Press, Social Science.

Bhopal, K. (2020). Confronting White privilege: the importance of intersectionality in the sociology of education. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 41, 807–816. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2020.1755224

Bhopal, K., and Pitkin, C. (2020). ‘Same old story, just a different policy’: race and policy making in higher education in the UK. Race Ethnicity Educ. 23, 530–547. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2020.1718082

Bodycott, P., and Walker, A. (2000). Teaching Abroad: lessons learned about inter-cultural understanding for teachers in higher education. Teach. Higher Educ. 5, 79–94. doi: 10.1080/135625100114975

Boliver, V. (2016). Exploring ethnic inequalities in admission to russell group universities. Sociology 50, 247–266. doi: 10.1177/0038038515575859

Bound, J., Braga, B., Khanna, G., and Turner, S. (2021). The globalization of postsecondary education: the role of international students in the US higher education system. J. Econ. Perspect. 35, 163–184. doi: 10.1257/jep.35.1.163

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bunce, L., and King, N. (2019). Experiences of autonomy support in learning and teaching among black and minority ethnic students at university. Psychol. Educ. Rev. 43, 2–8.

Burns, J. (2019). Universities ‘Oblivious’ to Campus Racial Abuse, Family & Education, BBC News. London: BBC.

Cannella, G. S., and Koro-Ljungberg, M. (2017). Neoliberalism in higher education: can we understand? can we resist and survive? can we become without neoliberalism? Cultural Stud. Critical Methodol. 17, 155–162. doi: 10.1177/1532708617706117

Chmielewski, A. (2019). The global increase in the socioeconomic achievement gap, 1964 to 2015. Am. Sociol. Rev. 84, 517–544. doi: 10.1177/0003122419847165

Claridge, H., Stone, K., and Ussher, M. (2018). The ethnicity attainment gap among medical and biomedical science students: a qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 18:325. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1426-5

Cotton, D. R. E., Joyner, M., George, R., and Cotton, P. A. (2015). Understanding the gender and ethnicity attainment gap in UK higher education. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 53, 475–486. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2015.1013145

Czaika, M., and Haas, H. (2015). The globalization of migration: has the world become more migratory? Int. Migration Rev. 48, 283–323. doi: 10.1111/imre.12095

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagné, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., and Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: a cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personal. Psychol. Bull. 27, 930–942. doi: 10.1177/0146167201278002

Dillon, J. (2011). Black minority ethnic students navigating their way from access courses to social work programmes: key considerations for the selection of students. Br. J. Soc. Work 41, 1477–1496. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcr026

Dualeh, H. (2017). BME Attainment Gap Report. Bristol: Bristol Students Union. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/sraa/Website%20bme-attainment-gap-report.pdf

Equality Human Rights Commission (2017). Equality Challenge Unit, Equality in Higher Education: Statistical Report. Advance HE Equality and Human Rights Commission. London: Equality and Human Rights Commission, Tackling Racial Harassment: Universities Challenged https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/tackling-racial-harassment-universities-challenged.pdf

Everett, B. G., Onge, J. S., and Mollborn, S. (2016). Effects of minority status and perceived discrimination on mental health. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 35, 445–469. doi: 10.1007/s11113-016-9391-9393

Flodén, J. (2016). The impact of student feedback on teaching in higher education. Assess. Eval. Higher Educ. 42, 1054–1068. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1224997

Gasman, M., Abiola, U., and Travers, C. (2015). Diversity and senior leadership at elite institutions of higher education. J. Diversity Higher Educ. 8, 1–14. doi: 10.1037/a0038872

Gillborn, D. (1997). Racism and reform: new ethnicities/old inequalities. Br. Educ. Res. J. 23, 345–360.

Goe, L., Bell, C., and Little, O. (2008). Approaches to evaluating teacher effectiveness: a research synthesis. Natl. Compr. Cent. Teach. Q. 103, 1–53.

Greenwood, N., Ellmers, T., and Holley, J. (2014). The influence of ethnic group composition on focus group discussions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 14:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-107

HESA Staff Statistics (2018). Higher Education Statistics Agency: Higher Education Staff Statistics: UK 2018/2019. Telangana: HESA.

HESA Statistics Bulletin (2020). Higher Education Statistics Agency: Higher Education Statistics Bulletin: UK 2019/2020. Telangana: HESA.

Hussain, M. (2016). Why is My Curriculum White? -Decolonising the Academy. NUS Connect. Available online at: https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/articles/why-is-my-curriculum-white-decolonising-the-academy (accessed February 09, 2021).

Jessop, T., and Williams, A. (2009). Equivocal tales about identity, racism and the curriculum. Teach. Higher Educ. 14, 95–106. doi: 10.1080/1356251080260281

Khambhaita, P., and Bhopal, K. (2015). Home or away? the significance of ethnicity, class and attainment in the housing choices of female university students. Race Ethnicity Educ. 18, 535–566. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2012.759927

Khan, O. (2019). Ethnic Minority Pupils get Worse Degrees and Jobs, Even if they Have Better A-levels. Available online at: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/education/2019/02/ethnic-minority-pupils-get-worse-degrees-and-jobs-even-if-they-have

Lessard-Phillips, L., and Li, Y. (2017). Social stratification of education by ethnic minority groups over generations in the UK. Soc. Inclusion 5, 45–54. doi: 10.17645/si.v5i1.799

McNamara, C., and Coomber, N. (2012). BME Student Experiences at Central School of Speech and Drama. Heslington: Higher Education Academy.

Meeuwisse, M., Severiens, S. E., and Born, M. P. (2010). Learning environment, interaction, sense of belonging and study success in ethnically diverse student groups. Res. Higher Educ. 51, 528–545. doi: 10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1

Mowat, J. G. (2017). Closing the attainment gap - a realistic proposition or an elusive pipedream? J. Educ. Policy 33, 299–321. doi: 10.1080/02680939.2017.1352033

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom: applying self-determination theory to educational practice. Theory Res. Educ. 7, 133–144. doi: 10.1177/1477878509104318

Panayiotou, M., and Humphrey, N. (2018). Mental health difficulties and academic attainment: evidence for gender-specific developmental cascades in middle childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 30, 523–538. doi: 10.1017/S095457941700102X

Panesar, L. (2017). Academic support and the BAME attainment gap: using data to challenge assumptions. Spark: UAL Creat. Teach. Learn. J. 2, 45–49.

Pilkington, A. (2013). The interacting dynamics of institutional racism in higher education. Race Ethnicity Educ. 16, 225–245. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2011.646255

Sims, J. (1998). Collecting and analysing qualitative data: issues raised by the focus group. J. Adv. Nurs. 28, 345–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00692.x

Smith, M. (2016). Race in the Workplace, McGregor-Smith Review. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/upload s/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/594336/race-in-workplace-mcgregor-s mith-review.pdf (accessed October 2021).

Song, M. (2020). Rethinking minority status and ‘visibility’. CMS 8:5. doi: 10.1186/s40878-019-0162-2

Stegers-Jager, K., Cohen-Schotanus, J., Splinter, T., and Themmen, A. (2011). Academic dismissal policy for medical students: effect on study progress and help-seeking behaviour. Med. Educ. 45, 987–994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04004.x

Ulysse, B., Berry, T. R., and Jupp, J. C. (2016). On the elephant in the room: toward a generative politics of place on race in academic discourse. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 29, 989–1001. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2016.1174903

Universities UK, and NUS (2019). Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Student Attainment At UK Universities:#Closingthegap. Universities UK, NUS. Available online at: https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2021-07/bame-student-attainment.pdf

Weissglass, J. (2004). “Racism and the Achievement Gap.” Education Week, August 2001. Bethesda, MD: https://www.Edweek.org/leadership/opinion-racism-and-the-achievement-gap/2001/08

Wilkesmann, U. (2013). Effects of transactional and transformational governance on academic teaching: empirical evidence from two types of higher education institutions. Tert. Educ. Manag. 19, 281–300. doi: 10.1080/13583883.2013.802008

Keywords: attainment-gap, ethnic, inclusion, higher education, BAME ethnicity

Citation: Rana KS, Bashir A, Begum F and Bartlett H (2022) Bridging the BAME Attainment Gap: Student and Staff Perspectives on Tackling Academic Bias. Front. Educ. 7:868349. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.868349

Received: 02 February 2022; Accepted: 14 April 2022;

Published: 06 May 2022.

Edited by:

Marco A. Bravo, Santa Clara University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jan Gube, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaJulie A. Hulme, Keele University, United Kingdom

Adria Patthoff, University of California, Santa Cruz, United States

Copyright © 2022 Rana, Bashir, Begum and Bartlett. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Karan S. Rana, ay5yYW5hMkBhc3Rvbi5hYy51aw==

Karan S. Rana

Karan S. Rana Amreen Bashir

Amreen Bashir Fatehma Begum

Fatehma Begum