- 1Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

- 2Berry Street, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

This qualitative study focused upon ways teachers make meaning when working with students who are affected by trauma. An 11-month longitudinal design was used to explore teachers’ perspectives (N = 18 teachers) as they reflected upon the impacts of trauma within their classrooms and as they learned about trauma-informed practice strategies. Data from group interviews and participant journals were analyzed using interpretative phenomenological analysis. Results emerged that suggested common pathways in the ways teacher perspectives evolved; and these pathways were then analyzed in light of the meaningful work literatures to further suggest how work became more meaningful to these teachers when learning trauma-informed practice strategies. Teachers fostered a greater sense of meaning at work via two pathways: first by increasing their own wellbeing via personal use of trauma-informed strategies; then second, by incorporating trauma-informed strategies into their pedagogy to more effectively engage their students with learning. Increasing meaningful work for teachers who are working with trauma-affected students has promising implications for teacher professional development and workforce sustainability in schools experiencing high rates of teacher turnover and burnout as a result of teacher exposure to adverse student behavior.

Introduction

The Increasing Need for Trauma-Informed Teachers

Considering the increasing numbers of children contending with adverse experiences and the impacts of trauma (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2020), the need to explore the voices and lived experiences of teachers takes on greater importance, particularly as many schools require effective implementation of trauma-informed practice responses. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; i.e., experiences that undermine a child’s belief that the world is good and safe such as experiencing violence, abuse or neglect) impact high numbers of children. For example, pre-COVID research estimates that children in Canada (67%), United Kingdom (50%), and United States (60%) have experienced at least one ACE (Cook et al., 2017; Association of Directors of Public Health [ADPH], 2020; National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2020; Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion [OAHPP], 2020). In Australia, the country of the current study, the number was higher at 72% (National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2020; Sahle et al., 2020).

Without intervention the impacts of ACEs can appear to teachers as dysregulated, escalated, disengaged, disruptive or sometimes violent student behaviors in classrooms (Downey, 2007). These challenging behaviors are often masking fear, lack of safety, sadness and great loss for students (Wolpow et al., 2009; National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2020). In direct response, Quadara and Hunter (2016) define trauma-informed practices as frameworks and strategies to understand and respond to the effects of trauma on wellbeing and behavior. It is, therefore, important that teachers are educated in trauma-informed practices to proactively address negative impacts of students’ behaviors on themselves, their peers and teachers (Hughes, 2004).

Further, the relevance of trauma-informed educational practices and strategies takes on greater significance given the COVID-19 pandemic which has triggered escalating rates of child and youth adversity (Ma et al., 2021; Piquero et al., 2021; Waters et al., 2021). Students and teachers across the world have been impacted by COVID-19 through illness, fear of exposure, losing loved ones, the move to remote learning and so on (Brown et al., 2020). COVID-19 has widened the equity gap and decreased student engagement in schools embedded in communities of educational inequity (Flack et al., 2020). Vulnerable students have experienced greater hardship due to factors such as the increasing prevalence of family violence (Humphreys et al., 2020). Researchers have identified that COVID-19 has led to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in youth samples during the pandemic (Guo et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020).

Considering adverse childhood experiences before COVID-19, and the compounding and ongoing impacts on child adversity during the pandemic, trauma-informed educational responses hold possibility for proactive steps for teachers to learn and then to enact. As Quadara and Hunter (2016) propose, when teachers learn about the impacts of trauma on child development and on their capacities to learn, teachers can be empowered to understand what they can proactively do to support children when learning. Further, teachers may feel more effective in both modeling repair responses to ruptures in the classroom while maintaining strong ethics of care, safety and compassion for the classroom community.

A Proactive Teacher Practice Response: Trauma-Informed Positive Education

Designed as an integrated practice contribution, trauma-informed positive education (TIPE; Brunzell et al., 2015, 2016b) was developed as an evidence-informed pedagogical approach from a systematic literature review of two relevant areas of trauma-informed education and positive education. This approach to trauma-informed educational practice aims to help teachers understand the impact of trauma on students’ wellbeing and learning whilst providing strengths-based pathways to support students meeting their own needs in healthy ways in the classroom and beyond.

TIPE is a practice application designed as a whole-school trauma-informed approach for teachers to learn. TIPE suggests developmental capabilities to trauma-informed teaching and learning which advises teachers to actively work toward fostering students’ own understanding of their stress response when learning; introduce strategies to regulate heightened responses to stress within the classroom (including mindfulness, sensory integration strategies, pairing rhythmic movement with learning academic content); increase relational strategies; learn about character strengths; prime times for learning with positive emotion; practice gratitude and intentionally savor small and big successes in class.1 TIPE has been shown to provide teachers with effective strategies to increase self-regulatory abilities in students (Brunzell et al., 2016a) and to increase their relational capacity and psychological resources for wellbeing (Brunzell et al., 2019). These early results are promising, and there is still much to explore with TIPE. There remains a need to understand the experiences and perspectives of teachers as they learn and practice TIPE to comprehensively sustain trauma-informed practices within a school’s culture, practices and tired-intervention approaches.

As TIPE has supported teachers to shift from reactive to proactive strategies to increase student engagement and wellbeing, it has also enabled teachers to maintain a strengths-based perspective much needed in classrooms impacted by stress- and trauma-exposure. The aims of TIPE are to provide teachers the knowledge and strategies for what to do when supporting dysregulated behaviors; and further, to maintain focus on each student’s inherent strengths. When teachers are able to observe when a child is learning well, using their strengths, and attached to the classroom community, they can work toward replicating these conditions for learning success.

Meaningful Work as a Protective Factor for Teachers

Like other professionals on the frontlines of supporting individuals impacted by trauma and chronic stressors, teachers can struggle to learn new practices when they are continuously service-rationing their limited resources of planning time, focus, and other resources (van Dernoot Lipsky, 2009). Teachers may also be managing vicarious impacts (secondary stressors) of witnessing, understanding, and supporting young people who have been impacted by trauma and chronic stressors (Alves et al., 2020). With respect to the impact of students’ trauma-related behaviors upon their teachers, previous research has shown that this leads to a loss of meaning for teachers who feel inadequately prepared to support students to meet their unmet learning needs; and this loss of meaning is directly related to compassion fatigue and workplace burnout (Brunzell et al., 2021). Aligned with this finding, Pines (2002) suggests that when teachers are unsuccessful at managing student disruption, it compromises their feelings of existential significance at work. According to Pines (2002, p. 133), students presenting resistant behaviors may trigger teacher beliefs that they can no longer “educate, influence, and inspire;” and this has negative impacts on teachers who need to believe their work is meaningful.

Research in other professions has shown that having work which provides meaning is an important component in one’s life satisfaction (Duffy et al., 2013), general wellbeing (Arnold et al., 2007) and global sense of life meaning (Steger et al., 2012). Having a sense of meaning at work also impacts various aspects of one’s work life, including positive affect and engagement at work (Steger et al., 2013), use of character strengths at work (Hartzer and Ruch, 2012), work satisfaction (Kamdron, 2005), feeling that work is important (Harpaz and Fu, 2002) and having a sense of calling. In addition, higher levels of meaningful work are related to less absenteeism and increased desire to stay in one’s organization (Steger et al., 2012).

When studying meaning at work, clarified the distinction between “work meaning” (i.e., whatever type of meaning people give and take from their work) and “meaningful work” (i.e., work that is both eudaimonically positive and significant for the individual; Dik et al., 2013a,b). Steger et al. (2012) describe four qualities of meaningful work: it is subjectively judged to matter by the individual, seen as significant, serves the greater good, and fulfills the broader need for meaning in one’s life. Three theories are often employed to suggest how work becomes meaningful: Rosso et al. (2010) bi-dimensional model of meaningful work, Steger and Dik’s (2009) three-factor theory of meaningful work, and Park’s (2005) meaning-making model.

The current study employs meaningful work theories as analytical tools in order to extend the findings from an earlier study which determined sources of meaningful work in teachers working within schools impacted by childhood trauma (see Brunzell et al., 2018). Two umbrella sources of meaningful work for teachers were identified in this earlier study: (1) Teachers believe their work is meaningful when their own workplaces nurture their own wellbeing as front-line professionals exposed to childhood trauma, and (2) they also believe their work is meaningful when practice pedagogies used across their schools effectively engage students who struggle with presentations of disengagement, resistance and defiance within the classroom. Restated, teachers believe that they can indeed cultivate meaningful work if they are given frequent opportunities within their work to increase their own wellbeing and to improve their own practice as teachers (Brunzell et al., 2018). The current study aims to extend these findings to increase understandings of how these two umbrella themes (sources) of meaningful work potentially interact or change over time when learning trauma-informed practices.

Within the meaningful work literature, (Dik et al., 2013b, p. 364) ask researchers to discover in what ways can meaningful work be “fostered, encouraged, elicited, or increased?” They also call for further investigation into the ways an individual’s work can be made even more meaningful. The contention within the current study is that by studying the qualitative responses, experiences and perspectives of teachers as they learned and implemented trauma-informed pedagogy, the field can gain nuanced understandings of how learning trauma-informed pedagogy impacts teachers’ perceptions of the efficacy and meaning of their own actions as they work toward implementation of trauma-informed practice approaches within their schools.

Materials and Methods

The qualitative methodology employed was interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) which privileged and prioritized the lived experiences and perspectives of participating teachers (Smith, 1996, 2017; Smith et al., 2009). In accordance with IPA, the aims and research questions in this study sought to (1) explore teachers’ own understanding and their perspectives when learning trauma-informed practice pedagogy (phenomenology), (2) understand the meanings of teachers’ own meaning making throughout professional learning (hermeneutics), and (3) place focus on individual teachers’ journeys (idiography) according to the perspectives of the teachers themselves. IPA guided the epistemology, procedural design, tools for data collection, researchers’ reflexivity, analytical strategies, and write up of the investigation.

Participants and Procedure

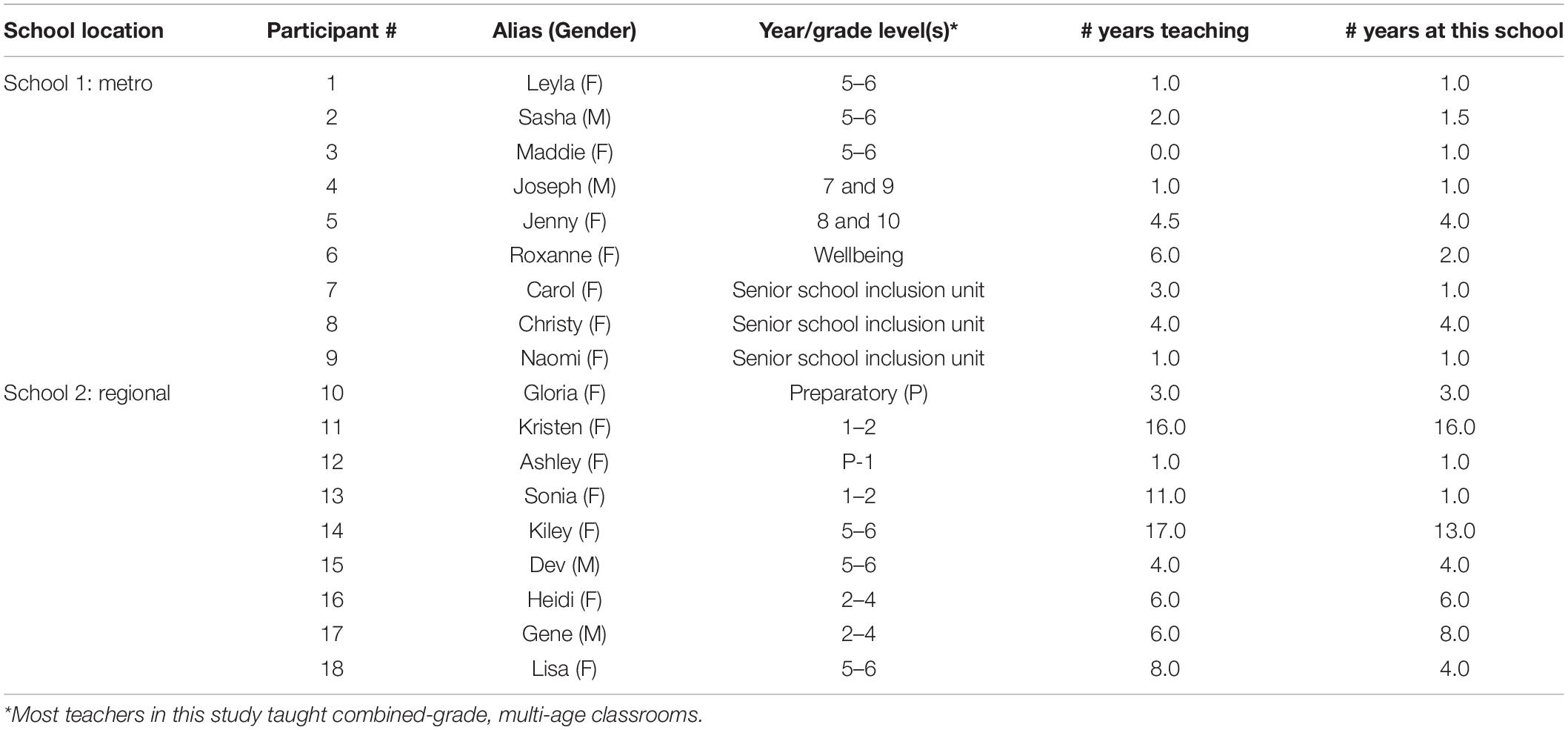

Eighteen teachers2 were sourced from two schools: a metropolitan school containing foundation (first year in school) to year 12 students (N = 9 teachers; 77% female, average years teaching = 1.8)3 and a rural school containing foundation to year six students (N = 9 teachers; 66% female, average years teaching = 12.2).4 Table 1 shows demographic information for participating teachers.

The data collection occurred across 8 days spread over 11-months (i.e., a complete school year). Within each session teachers reflected together on what they had learned about trauma-informed pedagogy and its daily applications to the classroom. The teachers also participated in group interviews and completed individual journals in each of the eight sessions across the year.

Data Collection

The current study collected qualitative data via group interviews and participant journals.

Group Interviews

Group interviews were selected to gather data based on practical concerns determined by the schools’ principals with the researchers as a condition for the study. Group interviews have been used for IPA (Flowers et al., 2000; de Visser and Smith, 2007; Palmer et al., 2010). Acknowledging IPA’s focus on idiography when using group interviews, caution is needed because the multiple voices and perspectives from group members can make it difficult to parse the individual and idiographic experiences of each participant (Smith et al., 2009). Smith et al. (2009) recommend one way to mitigate this is to analyze all transcripts at least twice: the first time to look for group patterns and the second time to look for idiographic, personal account. This two-step analytic process was used in the current study explained below.

Participant Journals

In addition to group interviews, teachers were asked to write in their own individual journals about their experiences and reflections throughout the course of the 11-months. Journals tapped into the idiographically unique aspects of meanings attributed by each teacher for themselves in their own words. Teachers were encouraged to record any stories or reflections that they did not want to share in the group.

Ethical Considerations

The approved application to the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 1442689.1) addressed several ethical concerns in the study. The roles of researchers and participating teachers involved an inherent power differential and affected the self-report of participant attitudes, perceptions, and actions. The study’s data collection strategies attempted to empower participating teachers by providing various ways to provide their responses (e.g., group interviews and individual journals). Confidentiality was carefully considered throughout the procedures for this study. Due to the small sample size of participants, confidentiality of responses could not be guaranteed by the researchers. Pseudonyms were used throughout the data reporting, analysis, and this report.

Discussing sensitive topics such as stress exposure due to managing adverse student behaviors may have led to empowerment and action toward mitigating the impacts of these behaviors; but it may also have led to the experience of unexpected distress during the research activities. No participant requested additional support as a result of their involvement in this study. However, if a participant had required further assistance, the researchers were ready to provide referral details for relevant professional services counseling for participants as specified in the study’s plain language statements.

Another potential concern (articulated by the ethics committee of the state government’s department of education) was ensuring participation in the study would be well integrated into teachers’ professional learning and workplace priorities. The ethics committee was assured that under agreements with the schools’ principals, the time commitment in this study included using a teacher’s pre-existing planning periods, and the principals agreed that a teacher’s participation in the study was designated planning time in teachers’ timetables. If a teacher felt their limited planning time was not being used effectively, or causing them duress when considering other priorities, a teacher could elect to exit the study.

Data Analysis

Step 1

Following IPA two-steps for employing group interviews (Smith et al., 2009), the first author read transcripts of all group interviews and re-read while listening to group interview recordings to become familiar with the text. Next, a line-by-line analysis was done by first author to determine IPA categories of emergent, super-ordinate and recurring themes (Smith et al., 2009).

Step 2

After the group interviews had been coded, the first author manually extracted, compiled and analyzed individual participant responses from group interview transcripts for emergent, super-ordinate and recurring themes for each individual participant (separate from group themes). Within this exploratory qualitative investigation, individual participant accounts were considered as an idiographic description of an individual’s unique journey. However, all 18-participant teachers were compared for themes and patterns. All texts from the journal entries were also transcribed from participant handwriting and subjected again to the IPA steps outlined above to monitor and include unique findings arising from participant journal entries.

Cross validation of data analysis occurred through dependability audits by two research colleagues (different to this study’s second and third authors) to increase internal confirmability and intercoder agreement. These colleagues (1) individually coded selected manuscripts from each participant, (2) noted emergent and super-ordinate themes, and (3) resolved discrepancies with the study’s authors. NVivo data analysis software was used to support the manual sorting and categorization of data themes. Together, the researchers with additional two colleagues conferred upon 174 unique codes yielding this study’s two recurring themes. Ongoing checks throughout this process between authors aimed to assess researcher bias from pre-existing biases due to a priori theory.

Results

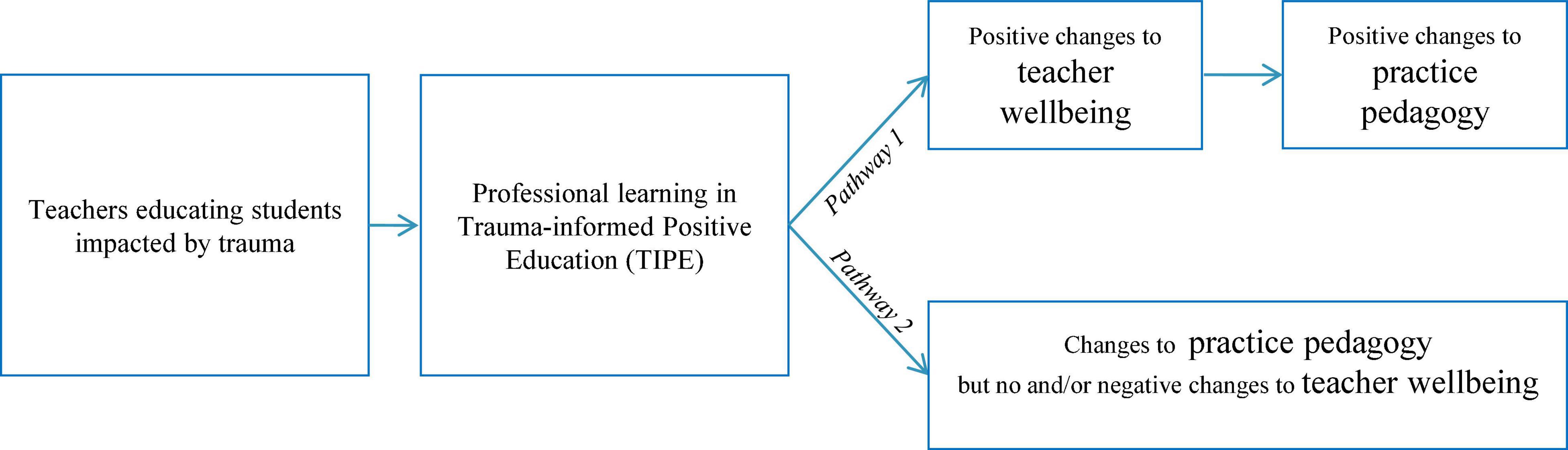

Results emerged showing teachers used two applications of trauma-informed positive education (TIPE): (1) they used TIPE strategies to increase their own wellbeing inside and outside work; and (2) they implemented new teaching practices (practice pedagogy) to better suit the needs of and engage with students impacted by trauma. Analysis showed two distinct pathways emerging from teachers’ experiences and reflections as shown in Figure 1.

In pathway one, teachers deliberately applied TIPE practices to themselves (e.g., de-escalation, self-regulation, breathing, mindfulness, strengths, gratitude) before they explicitly implemented these practices in their teaching with students. Within this first pathway there were two distinct subgroups: Subgroup one of teachers (N = 6) experienced considerable disruption to their prior held beliefs about their own abilities to teach in trauma-affected environments. Despite their best intentions at the beginning of the school year, they struggled when trying to manage disruptive student behavior and reported daily incidences of student disengagement and refusal to learn. This disruption to their initial beliefs (that they were indeed capable and prepared for their work) depleted the meaning they hoped to derive from their work; and they soon realized the most viable way to help their students was to ensure their own wellbeing was first in order.

Early on in the study, the teachers (who were eventually placed) in subgroup two (N = 10) confirmed their previously held belief that taking care of their own wellbeing was an effective buffer to the possible impacts of vicarious student trauma. These teachers knew that if they did not practice trauma-informed practices as applied in their own lives, they could not effectively learn nor practice trauma-informed practice strategies with authenticity with their students. Both subgroups one and two followed the same pathway when learning about and applying TIPE in their classrooms as shown in Figure 1.

In pathway two (N = 2), the teachers reported that they only focused on their students and not on their own wellbeing as adults. They did indeed learn and use TIPE strategies throughout the school year to introduce new practice pedagogy into their classrooms to increase engagement with learning. These teachers reported some increases in practice (i.e., observing positive changes in self-regulation and relationships in students as result of TIPE) but did not apply TIPE to their own wellbeing as professionals. At the end of the study, these teachers reported either no change or decreasing wellbeing at work. The following sections detail the stories and reflections as told by the teachers themselves representing the pathways of teachers learning of TIPE.

Pathway One: Changes to Wellbeing Before Practice Pedagogy

Subgroup One: Thriving After Faced With Failure to Teach

Common patterns emerged across participants placed in this subgroup showing how meaningful work plummeted within the first half of the school year due to significant disruption to their global beliefs regarding their professional capabilities to effectively teach their student cohorts. These six teachers started the year with enthusiasm and hope, and quickly reported presentations of secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue and burnout. All teachers in this group experienced disruption to their own beliefs about their own abilities and purposes for teaching.

Through their learning of trauma-informed strategies the teachers focused first by increasing their own wellbeing before attempting to apply changes to their pedagogy. For this group, applying TIPE to themselves first was a priority decision made by the teachers themselves. Their school year was described by one participant as a “journey of adversity” and teachers found themselves desperately needing strategies for their own wellbeing to feel their actions had positive meaning and were connecting with students.

In keeping with IPA’s focus on idiographic experiences, the reflections of one teacher in subgroup one are introduced below.5 Carol’s story represented a specific pathway toward meaningful work through disrupting previously held global values and beliefs. When Carol was asked about what made her work more meaningful, she spoke first about using what she was learning in TIPE to boost her own wellbeing, and thus she was able to cope more effectively. Later in the year, she explained she was spending much more time teaching effectively and witnessing “small wins” with students which reconnected her to her sense of meaning and purpose in her work.

Carol: “I was a barrier.” Carol, in her early 30s, had 3 years of teaching overseas before teaching in a metro-center within Australia. Her primary teaching responsibility was in the school’s specialist learning unit specifically designed for mixed-aged high school students struggling due to dysregulated behaviors, low academic achievement, and disengagement. She began her year with excitement and enthusiasm for her new school and work assignments, but her optimism quickly faded. Within the first week students were openly defiant to her instructions and refused to do their classwork. The co-teachers on her team acknowledged she had the most struggle with her own escalation. She reflected:

I do need to work on self-control because I am a little bit hot-headed, I can be persistent. So, trying to control myself in certain situations from not getting hot-headed is something that I’m more aware of.

In the following interview session, she spoke of yelling at students when they talked back to her, and having students walk out of class when they did not want to do their work. In the first term of the school year, her team was learning TIPE and creating interventions for the classroom (e.g., predictable rhythms and routines in the classroom, shared ways of de-escalating students, relationships based upon attachment and attunement, etc.). At the end of the first term, Carol shared that she was still struggling with her own personal escalated responses.

When prompted on how she was going with TIPE during the group interview, she replied:

I feel like [TIPE] is more about us than it is for [students]. So, I suppose, because I am a pretty confrontational person, and I love the drama. I think my self-regulation has changed quite dramatically. and at my old school, you just think you’re angry, you yell, or you get grumpy, and I’ve realised that I could’ve done that in the past quite a lot. So, I’ve really tried to work on grounding myself.

She spoke of “grounding herself” based on strategies she was learning through TIPE and from the activities that other teachers had shared in the group interview sessions (e.g., noticing escalation in her own body, centering herself, lowering her voice, taking a deep breath in front of the classroom, standing side-by-side with the student instead of looking down at them).

In her final group interview, she provided reflections on how her practice pedagogy had improved as a result of her working on her own wellbeing throughout the school year:

I was a barrier… I realise that I actually have grown, and my resilience as a teacher, because I think I’m a pretty resilient person in my personal life, but this school made me feel really insecure and really like I was a crap teacher and not very resilient at all. But I feel like I’m able to step back and work out strategies that’s not going to escalate me, escalate them.

Carol’s responses throughout the sessions provided insight into the ways TIPE was enhancing her sense of meaning over time. She was able to see the benefits of the new practices she was learning upon on herself, and then she reflected that focusing on trauma-informed strategies for her own wellbeing made her a more effective teacher for the students. Her own journey toward meaningful work was a slow process because she struggled for most of the school year with the daily exposure to trauma-affected students’ escalation. As evidenced through her own reflections, she noticed incremental changes to the way she felt in the work and reported positive changes in student outcomes. Getting to this personal insight required disrupting her initial beliefs about her own capabilities as a teacher—and forging a new path through trauma-informed pedagogy.

Subgroup Two: A Journey of Validation

Like subgroup one, teachers in subgroup two applied the practices they were learning in TIPE to their own wellbeing before integrating it into their practice pedagogy. However, while subgroup one did this due to significant disruption to their prior assumptions about their own workplace capabilities, subgroup two described how TIPE validated workplace meanings, beliefs and practices to which they already ascribed.

Sasha: “Your attitude becomes contagious.” Sasha, in his early 30s, had taught for 2 years at his current school, which was his first job following his university teacher training course. He was quickly elevated to team leader after a couple of years, leading four other teachers, in part because the school had significant staff turnover each year, and approximately 30% of his school’s teachers were new to the profession.

He described the classroom environment in the first session: “You know you’ve got to look after all these kids, especially the kids that always annoy you. Kids escalating and throwing things in the classroom.” He shared that both he and his teaching team needed consistent and effective strategies for both teachers and students to self-regulate in order to maintain healthy classroom relationships for learning. His insights suggested that he was already conscious and aware of his own wellbeing to be an effective teacher.

In the second term’s session, he told stories about using TIPE strategies for himself, particularly strategies for self-regulation, de-escalation, growth mindset and resilience at home with his partner and extended family. One such example is below:

Okay, and I just sort of found myself doing self-regulation at home. My wife rang me up and she told me, “Oh! Did you hear about this, that and that?” And I’ve got a really big family and everyone’s in competition with each other, and she told me this story that really got me upset. Any other day I would have just lost the plot, driven to my cousin’s house and had a word. But, I thought about what we’ve been learning, and I just said, “Yeah…let’s just come from a different angle,” and I was just really relaxed about it.

By term three, he began to actively apply his new language and learning from his personal life and personal wellbeing into the classroom. He openly modeled for the other teachers various strategies emerging from TIPE including how to describe his own de-escalating self-talk out loud and regulate students trying to self-exit from the classrooms; he created a set of over 150 emoji cards to teach emotional intelligence and prime his lessons with positive emotion; he created “red-light” and “green-light” thinking process charts to teach growth mindset; and he practiced self-regulatory strategies with the classes every day.

He also reaffirmed that an aspect of what made work meaningful to him was being a role-model to students:

I want to be the teacher that I needed when I grew up.I think for me it’s one of the most fulfilling things I’ve ever done. I like to say as a career it’s a fulfilling career. We’re a role-model because a lot of the kids might not have a mum and dad at home or someone to look up to. So, we’re a lot more than what we studied for, you know?

The practices he was learning in TIPE provided him with further ways to be a role-model (e.g., role modeling emotional regulation). Moreover, Sasha noticed his entire teaching team’s ability to role-model increased over time as they collectively re-imagined their profession as a role-modeling profession (instead of what Sasha described as “deliverers of information”). Like Sasha, the teachers in this subgroup all described the additive effects of their own wellbeing positively impacting their ability to work together to increase their strategies for on-task student learning.

Pathway Two: Practice Changes Only

Teachers in this pathway reported that TIPE led to positive changes in their practice pedagogy and thus, their increased capabilities to engage students. However, they deliberately chose to not practice TIPE in their own lives inside or outside work.

Dev: “It didn’t really cross over to my personal life…this year my focus was 100% on giving all the information to the kids.” Dev taught years 5 and 6 in a combined classroom. He had 4 years of teaching experience, all at his current primary school. In his late 20s, he was a physically active person, always dressed in sports gear or a jersey from his local football club and would find every opportunity to get his students outside and moving throughout the day. He frequently voiced grave concerns for the impacts of trauma within the wider community (a community in which he also lived in). Dev said he felt his own pedagogical aims were validated by TIPE’s focus on de-escalating stress-response systems within the body, physical activity, self-regulation, and rhythm.

He said he often connected physical activity with positive emotions and hunted for every opportunity to give students movement breaks when learning academic content. He then made a routine of asking students to reflect on how they were feeling as a result of these movement breaks called “positive primers” and “brain breaks” in TIPE. He found these movement breaks de-escalated students quickly and helped to increase student focus at the beginning of a lesson. In the interview groups, Dev frequently related TIPE to his practice pedagogy, though he plainly shared that he did not relate TIPE to his life or wellbeing outside work. He attributed this to the following:

My personal wellbeing is dependent of my ability to switch off. Unlike a lot of other teachers, when I go home, I have the ability to block work out of home and private life.

Analysis of his responses suggested that Dev considered TIPE part of his practice pedagogy—and that practice did not include a deliberate application to his own wellbeing inside or outside of work. In the final sessions, when asked in interviews (and journal prompts) to describe what provided him with meaning at work, Dev discussed how the TIPE practices allowed him to be a better teacher, but he did not mention that TIPE influenced his own wellbeing. In the final data collection rounds, Dev reported his wellbeing “was not very good” and had decreased throughout the year. He attributed this to school-based stressors of receiving inadequate workplace resources, unreasonable deadlines and feeling unsupported by his leadership team. He did not see TIPE as a potential way to reduce his own workplace related stressors.

Discussion

This qualitative study focused upon ways that teachers made meaning when teaching students affected by trauma and how their use of trauma-informed education strategies fostered more meaningful work. Results showed that TIPE enhanced meaning via two pathways: through the use of trauma-informed strategies to bolster their own wellbeing prior to embedding the strategies into the classroom, and through the direct use of trauma-informed strategies in the classroom without personal application.

Park’s (2005) meaning making model is helpful here to interpret the ways in which TIPE can facilitate meaningful work when teachers experience significant disruption to their prior held global beliefs about their own ability to be effective within trauma-affected classrooms. These results suggest that meaning making occurs as a deliberate process when teachers recover from a significant disruption or stressor (i.e., encountering a highly dysregulated and volatile classroom environment of students struggling with escalating and aggressive classroom behaviors) with ongoing attempts to reduce the discrepancy between their prior (global) worldview and their current reality of adversity within their classroom (Park, 2010). For example, teachers in pathway one, subgroup one all held a prior global worldview that they were capable teachers who could work effectively in vulnerable communities.

Park (2010) asserts that by resolving these discrepancies through new learning, the meaning making process promotes better accommodation of future stressors. Interpreted through Park’s meaning making model, teachers in this subgroup moved through stages toward resolution of new meaning through (1) acceptance (e.g., coming to terms with stressors in the workplace environment, and accepting that their prior reactions to ruptures were exacerbating student escalation and off-task behaviors), (2) perceiving their own growth through positive life changes (e.g., applying TIPE to life outside work; deliberating practicing self-regulatory strategies in one’s personal life and then modeling those strategies for the students), and (3) reappraising the meaning of stressors (e.g., de-personalizing student stress; Park, 2010).

When considering teachers like in pathway one’s subgroup two, it is helpful to recall Rosso et al. (2010) sources and mechanisms of how work becomes meaningful. For those like the teachers in this subgroup, a self-attributed source of meaningful work is one’s ability to role-model wellbeing to students, a relational theme within both teacher wellbeing and practice pedagogy. This source of meaningful work, role-modeling, can become activated through all four mechanisms of meaningful work (i.e., individuation, contribution, self-connection, and unification), particularly in the mechanism of authenticity (i.e., role-modeling allowed Sasha to feel like his “true-self”; Rosso et al., 2010, p. 109), and mechanisms of self-efficacy and purpose.

As shown in pathway two, there may be teachers who (after learning trauma-informed education strategies) might only apply those strategies in their practice pedagogy and not to their personal wellbeing. To recall the teachers in pathway two, their self-reported increases in practice pedagogy strategies were promising. They deliberately tried to integrate the research on self-regulation and positive emotion into classrooms and reported that students were noticeably more engaged in lessons.

Here, Steger et al. (2012) three-factor theory of meaningful work describes how teachers can increase meaningful work in the domain of practice pedagogy: (1) Comprehension—teachers in this pathway readily expressed more meaning in their job throughout the year when witnessing increased engagement behaviors in students. (2) Purpose—teachers’ learning of TIPE encouraged the creation of new strategies which fortified their aims for wanting to be effective teachers. (3) Serving the greater good—teachers clearly observed that new professional learning positively impacted students, the school community and the greater good within their local communities. However, like the teachers in this pathway who did not consciously practice trauma-informed strategies for themselves, teachers may quickly attribute decreases in their own wellbeing as related to structural issues within their school—for which they may have limited opportunities to change.

Limitations

When considering limitations, it must be recognized that the teacher learning sequence of TIPE and this study’s methodological strategies may have pre-constrained the findings. TIPE was learned by teachers in a specific, developmental order (i.e., first increasing self-regulatory abilities; next increasing relational capacity; and then increasing psychological resources; Brunzell et al., 2016b), and the data collection strategies captured data in the time period after teachers learned each one of these domains.

While a strength of this design allowed the researchers to focus on how teachers specifically learned (and reflected upon) each of TIPE’s domains, future research with different methods may find alternative themes that do not follow the findings from this study. An alternative to the current design may be to first introduce all TIPE domains to teachers; next, allow time to pass for teachers to possibly apply these domains to their own wellbeing and practice; and then, begin data collection to explore possible impacts. Employing this kind of design would allow researchers to understand teacher priorities and workplace application when not interrupted by data collection.

Implications and Future Directions

It is often the case that teachers who are experiencing ill-being within trauma-organized systems (Bloom and Sreedhar, 2008) are only given approaches that address their illbeing/wellbeing (Cartwright and Cooper, 2005). However, only focusing on teacher wellbeing fails to build teachers’ pedagogical capabilities to work with students presenting complex unmet needs within the classroom as a result of trauma. The results of this study suggest that trauma-informed education approaches to address teacher wellbeing should also include teacher practice as a key priority in order to support workface sustainability.

Conclusion

The current study provides novel contribution to the field including a new model proposing how teachers can make and extend meaningful work using trauma-informed approaches within their classrooms. There is urgent world-wide need to provide viable trauma-informed approaches to buffer teachers against the primary and secondary impacts of distress and trauma arising through the COVID-19 pandemic (Alves et al., 2020). Teachers must be given viable ways to process and create new meaning through their ongoing exposure to student trauma. Understanding how to increase meaningful work for trauma-affected teachers can make a valuable contribution to teacher practice and wellbeing—and to enhance the outcomes for students who need to experience daily success when learning. The current evidence suggests that teachers might welcome the invitation to apply TIPE strategies to themselves and with their students.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Melbourne. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by funding received through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ For more detailed information about TIPE (see Brunzell et al., 2016b).

- ^ All names, including school and participant names, have been given pseudonyms to protect participant identities as outlined in the study’s ethical agreements. All participants have been given the opportunity to review all transcripts of interviews and journal entries, and they have provided their consent for the use of their responses in this report.

- ^ The Index of Community Socio-Educational Advantage (ICSEA) for this school is 967 (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2020). An ICSEA is a scale which allows comparison among schools with similar student cohorts. Schools with ICSEA scores of 800–999 are considered to be lower in educational advantage than the national Australian average. Forty percent of families in the F-12 school were in the state’s lowest quartile for socio-economic status. Forty two percent of the students had a language background other than English. School reports for trauma-affected students were confirmed by community psychological support agencies, child protective services and the school.

- ^ The ICSEA for this school is 883 (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2020). Seventy two percent of families in the school were in the state’s lowest quartile for socio-economic status. Twenty four percent of students in the school were of Aboriginal descent. Thirty percent were known to the State Government Department responsible for Child Protection services. School reports for trauma-affected students were supplied by community psychological support agencies, child protective services and the school.

- ^ Only three participants are detailed within this report in keeping with this study’s IPA methodology and its emphasis on phenomenological participant experience (Smith et al., 2009). Participants were chosen due to their representation of common themes across participants and contribution to novel theorizing.

References

Alves, R., Lopes, T., and Precioso, J. (2020). Teachers’ well-being in times of Covid-19 pandemic: factors that explain professional well-being. Int. J. Educ. Res. Innov. 15, 203–217. doi: 10.46661/ijeri.5120

Arnold, K. A., Turner, N., Barling, J., Kelloway, E. K., and McKee, M. C. (2007). Transformational leadership and psychological wellbeing: the mediating role of meaningful work. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 12, 193–203. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.12.3.193

Association of Directors of Public Health [ADPH]. (2020). Creating ACE Informed Places: Promoting a Whole-System Approach to Tackling Adverse Childhood Experiences in Local Communities. Available Online at: https://www.health.org.uk/project/creating-ace-informed-places-promoting-a-whole-system-approach-to-tackling-adverse?gclid=CjwKCAjw8-78BRA0EiwAFUw8LA46r1flT7laQhwTepeyr5rbF7czvdPs1USimQCPEjTYLhj4PVF-WxoCBK8QAvD_BwE [accessed October 30, 2020].

Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2020). About ICSEA Factsheet. Available Online at: https://www.myschool.edu.au/media/1835/about-icsea-2020.pdf [accessed February 9, 2020].

Bloom, S. L., and Sreedhar, S. Y. (2008). The sanctuary model of trauma-informed organizational change. Reclaim. Child. Youth 17, 48–53.

Brown, N., Te Riele, K., Shelley, B., and Woodroffe, J. (2020). Learning at Home During COVID-19: Effects on Vulnerable Young Australians. Independent Rapid Response Report. Peter Underwood Centre for Educational Attainment. Available Online at: https://www.utas.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/1324268/Learning-at-home-during-COVID-19-updated.pdf [accessed November 3, 2020].

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2016b). Trauma-informed positive education: using positive psychology to strengthen vulnerable students. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 20, 63–83. doi: 10.1007/s40688-015-0070-x

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2016a). Trauma-informed flexible learning: classrooms that strengthen regulatory abilities. Int. J. Child Youth Fam. Stud. 7, 218–239. doi: 10.18357/ijcyfs72201615719

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2018). Why do you work with struggling students? Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 116–142. doi: 10.14221/ajte/vol43/iss2/7

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2019). Shifting teacher practice in trauma-affected classrooms: practice pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. School Ment. Health 11, 600–614. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., and Stokes, H. (2015). Teaching with strengths in trauma-affected students: a new approach to healing and growth in the classroom. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 85, 3–9. doi: 10.1037/ort0000048

Brunzell, T., Waters, L., and Stokes, H. (2021). Trauma-informed teacher wellbeing: teacher reflections within trauma-informed positive education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 91–107. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2021v46n5.6

Cartwright, S., and Cooper, C. (2005). “Individually targeted interventions,” in Handbook of Work Stress, eds J. Barling, E. Kelloway, and M. Frone (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 607–623. doi: 10.4135/9781412975995.n26

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., et al. (2017). Complex trauma in children and adolescents. Psychiatr. Ann. 35, 390–398.

de Visser, R. O., and Smith, J. A. (2007). Alcohol consumption and masculine identity among young men. Psychol. Health 22, 595–614. doi: 10.1080/14768320600941772

Dik, B. J., Byrne, Z. S., and Steger, M. F. (eds). (2013a). “Toward an integrative science and practice of meaningful work,” in Purpose and Meaning in the Workplace, (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 3–14. doi: 10.1037/14183-001

Dik, B. J., Steger, M. F., Fitch-Martin, A. R., and Onder, C. C. (2013b). “Cultivating meaningfulness at work,” in The Experience of Meaning in Life: Classical Perspectives, Emerging Themes, and Controversies, eds J. A. Hicks and C. Routledge (Berlin: Springer), 363–377. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-6527-6_27

Downey, L. (2007). Calmer Classrooms: A Guide to Working with Traumatized Children. Victoria: Australian Child Safety Commissioner.

Duffy, R. D., Allan, B. A., Autin, K. L., and Bott, E. M. (2013). Calling and life satisfaction: it’s not about having it, it’s about living it. J. Couns. Psychol. 60, 605–615. doi: 10.1037/a0030635

Flack, C. B., Walker, L., Bickerstaff, A., and Margetts, C. (2020). Socioeconomic Disparities in Australian Schooling During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Essendon: Pivot Professional Learning.

Flowers, P., Duncan, B., and Frankis, J. (2000). Community, responsibility and culpability: HIV risk management amongst Scottish gay men. J. Commun. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 10, 285–300. doi: 10.1002/1099-1298(200007/08)10:4<285::aid-casp584>3.0.co;2-7

Guo, J., Fu, M., Liu, D., Zhang, B., Wang, X., and van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2020). Is the psychological impact of exposure to COVID-19 stronger in adolescents with pre-pandemic maltreatment experiences? A survey of rural Chinese adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 110:104667. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104667

Harpaz, I., and Fu, X. (2002). The structure of the meaning of work: a relative stability amidst change. Hum. Relat. 55, 639–667. doi: 10.1177/0018726702556002

Hartzer, C., and Ruch, W. (2012). When the job is a calling: the role of applying one’s signature strengths at work. J. Posit. Psychol. 7, 362–371. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2012.702784

Hughes, D. A. (2004). An attachment-based treatment of maltreated children and young people. Attach. Hum. Dev. 6, 263–278. doi: 10.1080/14616730412331281539

Humphreys, K. L., Myint, M. T., and Zeanah, C. H. (2020). Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 145:e20200982. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982

Kamdron, T. (2005). Work motivation and job satisfaction of the Estonian higher officials. Int. J. Public Adm. 28, 1211–1240. doi: 10.1080/01900690500241085

Liang, L., Ren, H., Cao, R., Hu, Y., Qin, Z., Li, C., et al. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatr. Q. 91, 841–852. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3

Ma, L., Mazidi, M., Li, K., Li, Y., Chen, S., Kirwan, R., et al. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 293, 78–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021

National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN] (2020). Understanding Child Trauma and the NCTSN. Los Angeles, CA: National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion [OAHPP] (2020). Interventions to Prevent and Mitigate the Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) in Canada: a Literature Review. Ontario: Queen’s Printer.

Palmer, M., Larkin, M., de Visser, R., and Fadden, G. (2010). Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qual. Res. Psychol. 7, 99–121. doi: 10.1080/14780880802513194

Park, C. L. (2005). “Religion and meaning,” in Handbook of the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, eds R. F. Paloutzian and C. L. Park (Los Angeles, CA: Guilford), 295–314.

Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of meaning literature: an integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychol. Bull. 136, 257–301. doi: 10.1037/a0018301

Pines, A. M. (2002). Teacher burnout: a psychodynamic existential perspective. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 8, 121–140. doi: 10.1080/13540600220127331

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., and Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic-evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crim. Just. 74:101806. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

Quadara, A., and Hunter, C. (2016). Principles of Trauma-Informed Approaches to Child Sexual Abuse: A Discussion Paper. Sydney: Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., and Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: a theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 30, 91–127. doi: 10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Sahle, B., Reavley, N., Morgan, A., Yap, M., Reupert, A., Loftus, H., et al. (2020). Communication Brief: Summary of Interventions to Prevent Adverse Childhood Experiences and Reduce Their Negative Impact on Children’s Mental Health: An Evidence Based Review. Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health. Parkville, VIC: Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

Smith, J. A. (1996). Beyond the divide between cognition and disclosure: using interpretative phenomenological analysis in health psychology. Psychol. Health 11, 261–271. doi: 10.1080/08870449608400256

Smith, J. A. (2017). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: getting at lived experience. J. Posit. Psychol. 12, 303–304. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1262622

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., and Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis – Theory, Method and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Steger, M. F., and Dik, B. J. (2009). If one is looking for meaning in life, does it help to find meaning in work? Appl. Psychol. Health Wellbeing 1, 303–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01018.x

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., and Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: the work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 20, 322–337. doi: 10.1177/1069072711436160

Steger, M. F., Littman-Ovadia, H., Miller, M., Meger, L., and Rothmann, S. (2013). Affective disposition, meaningful work, and work-engagement. J. Career Assess. 21, 348–361. doi: 10.1177/1069072712471517

van Dernoot Lipsky, L. (2009). Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R. S., et al. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain Behav. Immun. 87, 40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

Waters, L., Cameron, K., Nelson-Coffey, K., Crone, D. L., Kern, M. L., Lomas, T., et al. (2021). Collective wellbeing and posttraumatic growth during COVID-19: how positive psychology can help families, schools, workplaces and marginalized communities. J. Posit. Psychol. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1940251

Keywords: trauma-informed education, positive education, teacher practice, meaningful work, teacher wellbeing

Citation: Brunzell T, Waters L and Stokes H (2022) Teacher Perspectives When Learning Trauma-Informed Practice Pedagogies: Stories of Meaning Making at Work. Front. Educ. 7:852228. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.852228

Received: 10 January 2022; Accepted: 03 May 2022;

Published: 17 June 2022.

Edited by:

Ruth Buzi, Independent Researcher, Bellaire, TX, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Brunzell, Waters and Stokes. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tom Brunzell, dGJydW56ZWxsQGJlcnJ5c3RyZWV0Lm9yZy5hdQ==

Tom Brunzell

Tom Brunzell Lea Waters1

Lea Waters1