- 1Institute of Education and Child Studies, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 2Centre for Inclusion and Health in Schools, Zurich University of Teacher Education, Zurich, Switzerland

- 3Department of Psychology, Applied Social and Health Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Natural Sciences, University of Stirling, Stirling, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Sports Science, Sport Psychology, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany

- 6Institute of Human Movement Science, Health Sciences, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

The satisfaction of teachers’ need for relatedness is an important pre-condition for teachers’ wellbeing. Receiving social support plays an important role in satisfying the need for relatedness. Following job crafting theory, the present study aims to examine (1) whether searching for social support results in an increase in the satisfaction of the need for relatedness and (2) whether this effect is mediated by an increase of received social support from the school principal and from colleagues. Using longitudinal data (N = 1071) we calculated residualized change scores and applied structural equation modeling to test the hypothesized mediation model. Results confirmed the beneficial effect of searching for social support on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. This effect included a direct effect and an indirect effect through the receipt of social support from colleagues. The receipt of social support from the school principal was positively related to searching for social support but was unrelated to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. These findings emphasize the importance that teachers build strong and supportive relationships within the school team, as this helps to satisfy their need for relatedness, which in turn contributes to better wellbeing among teachers.

Introduction

Teaching is frequently being associated with the experience of relatively high stress levels and reduced wellbeing among teachers (Desrumaux et al., 2015; Harmsen et al., 2018; Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2018). The receipt of social support is an important job resource that can be beneficial for teachers’ wellbeing and thus their functioning (Rothland, 2007). According to self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 2000) individuals experience wellbeing and optimal functioning when their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied. Previous research shows that social support primarily contributes to the satisfaction of the need for relatedness (van den Broeck et al., 2010; Fernet et al., 2013). Thus, strengthening the receipt of social support among teachers may result in tight-knit school teams that can support teachers’ wellbeing and functioning and thereby contribute to educational quality (Moolenaar, 2012). Therefore, it is important to examine how the receipt of social support in schools can be strengthened. The individual and proactive role of teachers in receiving social support by searching for it is underexposed in this question.

Searching for Social Support

The exchange of social support is an essential aspect of social interactions (Knoll and Kienle, 2007) which involves the qualitative aspect of helping behavior between two persons. Multiple types of such supportive interactions can be distinguished. Perceived or anticipated social support entails the support a person expects to be available in their social network when help is needed (Knoll and Kienle, 2007). Studies indicated that perceived social support is rather a stable than a modifiable characteristic (e.g., Sarason et al., 1987). Thus, perceived social support is rather independent from the actual behavior a specific network member displays and therefore not an optimal indicator to measure supportive interactions (Knoll and Kienle, 2007). In contrast, received social support is a retrospective report that reflects actual support transactions from specific network members (Uchino, 2009). The present study focusses on received social support.

The concept of job crafting (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001; Tims and Bakker, 2010) provides a bottom-up perspective from which we can examine what teachers individually can contribute to the social support they receive and therefore to their satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Job crafting involves a process in which employees individually and proactively adjust job demands and job resources to make their job better fit their needs, preferences, and abilities (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001; Tims and Bakker, 2010). This is in contrast to a top-down perspective that focuses on changes in the work environment initiated by supervisors. Searching for social support is a central element of job crafting that aims at actively increasing the social support one receives (Tims et al., 2012). First studies from occupational health psychology that examined samples outside the context of schools suggest that searching for social support can increase the receipt of social support (Tims et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2015). However, whether teachers’ individual and proactive search for social support may result in an actual increase in the receipt of support is unclear.

Furthermore, teachers have two sources at school to which they might turn to for receiving social support: the school principal and colleagues. The nature of the relationship between the one giving and the one receiving support may influence the effects of social support (Sarason et al., 1994). Therefore, we explore possible differences in the effect of teachers’ search for social support on the receipt of social support from the school principal and from colleagues and possible differences in their effect on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness.

Searching for Social Support and the Satisfaction of the Need for Relatedness

The basic psychological need for relatedness involves feelings of respect, understanding, and connectedness which result from strong interpersonal relationships (Deci and Ryan, 2000). The need to form and maintain such relationships is considered to be universal and central to human psychological functioning (Baumeister and Leary, 1995). The social interaction that occurs in the process of searching for social support and receiving it, strengthens interpersonal relationships and contributes to feelings of respect, understanding, and connectedness. By searching for social support from the school principal and from colleagues, teachers build meaningful relationships and feel connected to others at work. Empirical studies demonstrated beneficial effects of searching for social support at the workplace, such as more satisfaction of the need for relatedness (Bakker and Oerlemans, 2019), higher work engagement (Bakker et al., 2016), higher job satisfaction (Tims et al., 2013), and higher self-rated performance (Petrou et al., 2015). The underlying mechanism that can explain these beneficial effects might be found in the aim of searching for social support to increase the amount of social support one receives. This implies that effects on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness are indirect effects through actual changes in the receipt of social support. This mediating process was previously demonstrated in the effects of searching for social support on work engagement, job satisfaction, and burnout (Tims et al., 2013).

Aim of the Study

To improve educational quality it is important to investigate the individual and proactive role that teachers can play in strengthening the social support they receive at work. So far, it is unclear whether searching for social support results in an actual increase in the receipt of social support among teachers. Moreover, there is limited evidence for processes that explain the benefit that can arise from searching for social support. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine whether searching for social support results in satisfaction of the need for relatedness and whether this is mediated by an increase in the social support that teachers receive from the school principal and from colleagues, hence an indirect effect. In contrast, a direct effect would imply that the effect of searching for social support on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness is independent of changes in the social support that teachers receive. Moreover, these effects of the search for social support and its receipt may depend on the source of the social support (Sarason et al., 1994). Therefore, we distinguish between the receipt of social support from the school principal and colleagues and examine the different mediating roles. Thus, we advance the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis. Searching for social support results in an increase in the satisfaction of the need for relatedness through an increase in the receipt of social support from the school principal and from colleagues.

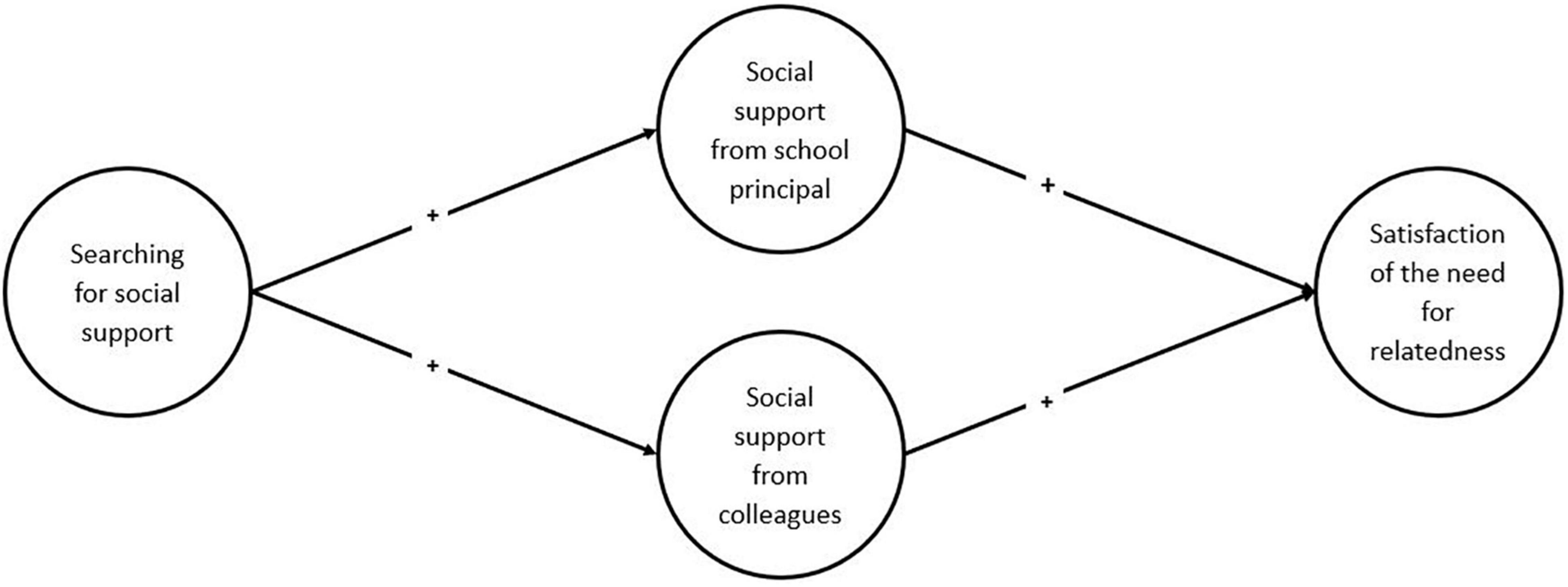

Figure 1 shows the hypothesized relationships between searching for social support, receipt of social support, and the satisfaction of the need for relatedness.

Methods

The hypothesis was tested in a sample of teachers using a longitudinal online study with three measurement time points. The participants were requested to fill out online questionnaires in the school year 2017/2018. The first questionnaire was assessed in September 2017 (T1), the second in January 2018 (T2), and the third in May 2018 (T3). The completion of each questionnaire took 45 min on average. As compensation for their participation the participants received a voucher worth 25 Swiss francs for each of the three completed questionnaires.

Participants

Participants were teachers at primary (pupils aged 5--12 years) and lower-secondary compulsory school level (pupils aged 13--15 years) in the German-speaking part of Switzerland. They were recruited through teacher organizations. The participants registered individually for participation by giving written informed consent. Eligible for participation were teachers that: teach at primary or lower secondary school level, have a minimum workload of 10 lessons per week, and work at a school with a formal school principal1.

In total, N = 1365 teachers gave written informed consent. Of these, n = 1082 (79.3%) completed all three questionnaires. Over the course of the three measurement points n = 283 participants dropped out (20.7%). Dropout was unrelated to the control variables and to the model variables. From the total sample of N = 1,365 participants, data of n = 294 participants were excluded: n = 110 participants did not meet the conditions for participation, n = 154 participants were special education teacher and worked with very small groups of students in contrast to the other study participants working with groups of around 20 students, n = 28 participants did not have the same school principal during the entire period of data collection (T1--T3), and n = 2 participants gave implausible answers. The final sample consisted of N = 1071 teachers (79.5% females, 18.3% males, 2.1% persons did not report gender). Age ranged between 22 and 65 years (M = 42.8 years, SD = 11.3). School level was distributed as follows: 74.7% teachers at primary school level, 23.1% teachers at lower secondary school level, and 2.2% teachers at both primary and secondary school level. There were no significant differences between primary and lower secondary school level with regard to the study variables2. The mean teaching experience was M = 17.3 years (SD = 10.9), and the mean workload was M = 80.8% of a full-time equivalent (SD = 20.2). Although the study did not aim to obtain representative data, these sample characteristics corresponded largely to the population of teachers in the German-speaking part of Switzerland in the school year 2016/17. Population characteristics are: 75% females, 25% males, 42% younger than 40 years and 58% older than 40 years, and from the total teacher population in Switzerland 59% teach at primary school level and 29% at lower secondary school level (Federal Statistical Office, 2018).

Measures

This section describes the measurement scales which were used for the study variable. We used well-established instruments and adapted them to the school context.

Searching for social support was assessed at T2 because we aimed to measure changes during one school year. In this process of change we assume that “searching for social support” becomes most important for teachers later in the school year instead of at the beginning. Moreover, by this design we aimed to build on and partly replicate the study conducted by Tims et al. (2013). This study applied a comparable design by examining effects of “crafting social resources” at T2 on changes in social job resources and wellbeing between T1 and T3.

“Searching for social support” was measured with an adapted version of the scales emotional support seeking and instrumental support seeking from the Pro-active Coping Inventory (Greenglass et al., 1999). Due to a strong correlation between searching for emotional and instrumental support (r = 0.76, p < 0.000) we combined the two scales into one general scale “searching for social support.” From the subscale “searching for emotional support” we excluded the item “I know who can be counted on when the chips are down.” This item related more to the cognitive level of knowing people that can help. Yet, we aimed to measure the active search for support on the behavioral level. This distinction was also empirically confirmed: the factor loading of this item was considerably lower (0.37) than the factor loadings of the other items (ranging between 0.64, and 0.83). For the same reason we excluded the item “I can usually identify people who can help me develop my own solutions to problems” from the subscale “instrumental support seeking.” This item did not relate to an active search for support but rather to a cognitive level of knowing people that can help. Empirically, the factor loading supported this decision because it was considerably lower (0.48) than the factor loadings of the other items (ranging between 0.68 and 0.78). Sample items of the remaining scale were for example “I asked for support from others in my school” and “I asked others in my school what they would do in my situation” with a 4-point response format (anchors is not true and absolutely true). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 (M = 2.73, SD = 0.67).

Received social support from the school principal and received social support from colleagues were both assessed at T1 and T3 using an adapted version of the Berlin Social Support Scales (Schulz and Schwarzer, 2003). The original scale was reformulated to fit the school setting and adjusted to the social support provider: school principal or colleagues, respectively. Both scales consisted of the subscales emotional and instrumental social support which were, due to a strong correlation (r = 0.85 and 0.86 at T1 and r = 0.86 and 0.87 at T3), merged to create one scale. Moreover, from both scales (school principal and colleagues), three negatively worded items were excluded because they did not load on the intended factor but constituted a separate factor. A phenomenon that appears to be rather common for negatively worded items (Barnette, 2000). This resulted in two scales both consisting of ten items. A sample item was ‘‘My principal/colleagues assured me that I can rely completely on him/her/them’’ with a 6-point response format (anchors is not true and absolutely true). The scale’s internal consistency from the scale ‘‘social support from the school principal’’ was Cronbach’s alpha 0.94 at T1 (M = 4.11, SD = 1.26) and 0.95 at T3 (M = 3.93, SD = 1.31), and from ‘‘social support from colleagues’’ was Cronbach’s alpha 0.93 at T1 (M = 4.72, SD = 1.06) and 0.94 at T3 (M = 4.61, SD = 1.07)3.

Satisfaction of the need for relatedness: was assessed at T1 and T3 with the German version of the Work-related Basic Need Satisfaction scale (van den Broeck et al., 2010). The scale consisted of 6 items with a 5-point response format (anchors not true at all and absolutely true). A sample item was “At work I feel as part of a group.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.81 at T1 (M = 3.98, SD = 0.76) and 0.84 at T3 (M = 3.96, SD = 0.78).

Data Analyses

The hypothesized model was tested with structural equation modeling using R version 3.4.3 (R Core Team, 2018) and the Lavaan package version 0.6-3 (Rosseel, 2012).

To estimate the hypothesized model, we used robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR), which is robust against violations of normality assumptions (Lai, 2018). Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was used to handle missing data (Graham and Coffman, 2012).

Model fit was assessed using the chi-square/df ratio (χ2/df), the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR), and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Values of χ2/df < 5 indicate good model fit (West et al., 2012). RMSEA values of ≤0.06 indicate a good fit, SRMR values of ≤0.08 are considered as a good fit, and the incremental fit indices CFI >0.95 reflects a good fit (Hu and Bentler, 1999). To test the proposed mediated effects we used bootstrapping instead of the MLR estimator. Bootstrapping is a statistical re-sampling method recommended for testing indirect effects which creates an empirical sampling distribution through resampling the original sample (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Estimations of confidence intervals of indirect effects by bootstrapping are more accurate, because it does not assume a normal sampling distribution, which is the case for indirect effects (Shrout and Bolger, 2002). We computed bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence intervals from 1,000 resamples (MacKinnon et al., 2004; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). A significant mediation is indicated when the confidence intervals exclude zero.

To measure change over the course of one school year in the receipt of social support and in teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness, we used residualized change scores (cf., Tims et al., 2013). Following the recommendations of Smith and Beaton (2008), standardized residualized change scores were computed by regressing T3 scores on the corresponding T1 scores. The differences between the predicted and the observed scores at T3 were included as standardized residual scores in the hypothesized mediation model. Compared to simple difference scores, residualized change scores have higher reliability because they do not correlate with the initial T1 score (Williams et al., 1987). Residualized change scores indicate which individuals have changed more, or less, than can be expected based on their T1 score (Smith and Beaton, 2008).

Results

Preliminary Analyses: Descriptives and Correlations

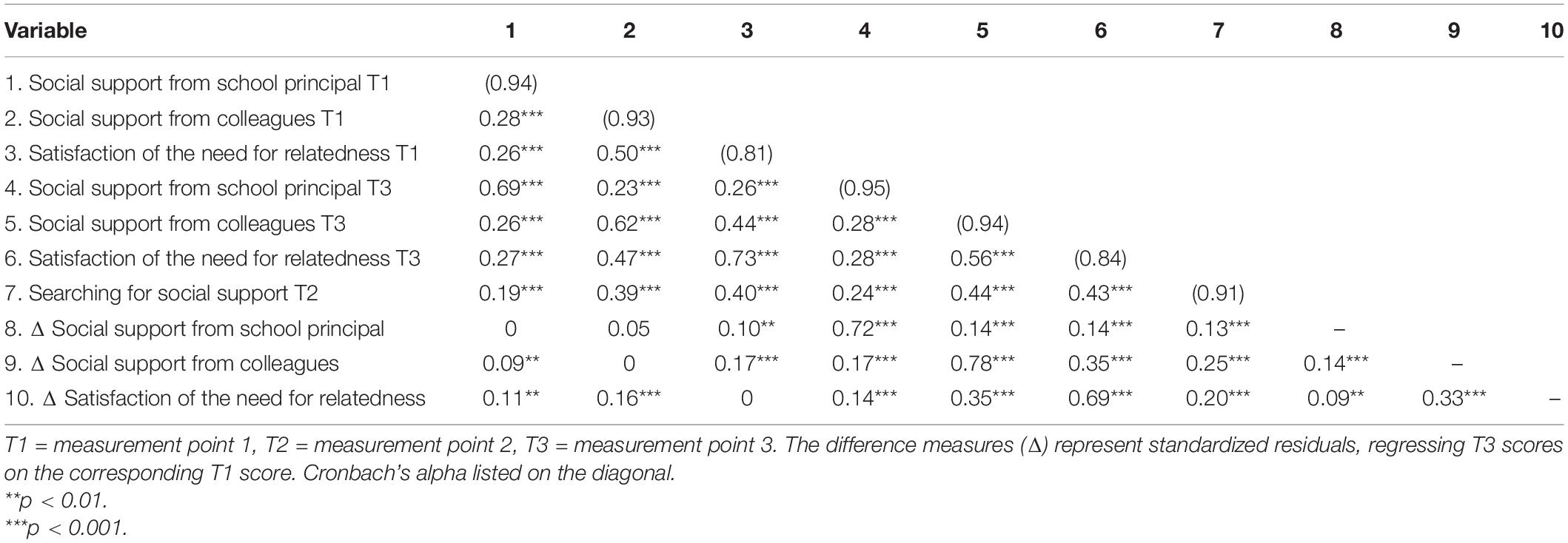

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations of the variables at T1 and T3 and the model variables are displayed in Table 1. Zero-order correlations between T1 and T3 measurement waves were strong ranging between r = 0.62 and r = 0.73 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, zero-order correlations between all model variables were significant (p < 0.01).

Table 1. Zero-order correlations between variables at T1 and T3 and between model variables and cronbach’s alpha (N = 1071).

Preliminary Analyses: Model Fit of the Measurement Model

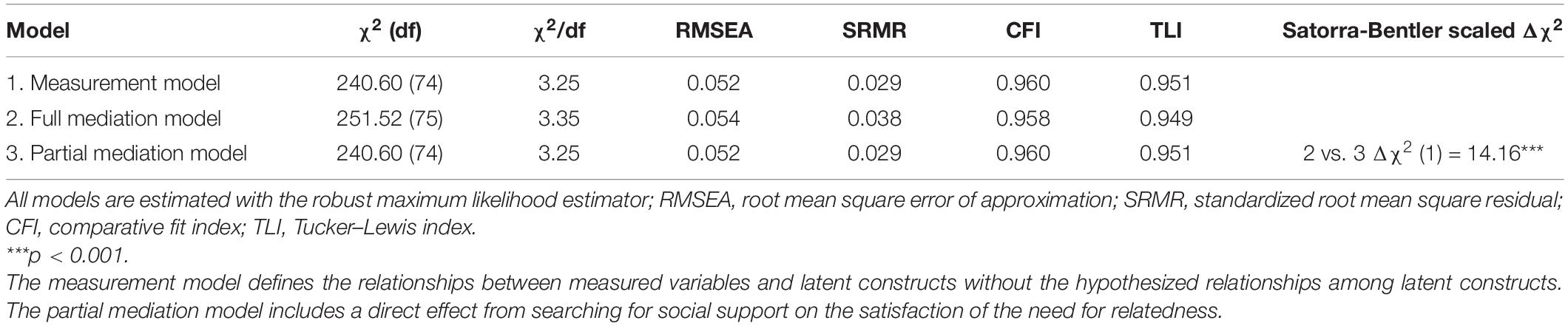

We tested the model fit of the measurement model applying a confirmatory factor analysis. The measurement model yields a sufficient model fit: χ2/df = 3.25, CFI = 0.960, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.029 (see Table 2).

Main Analyses

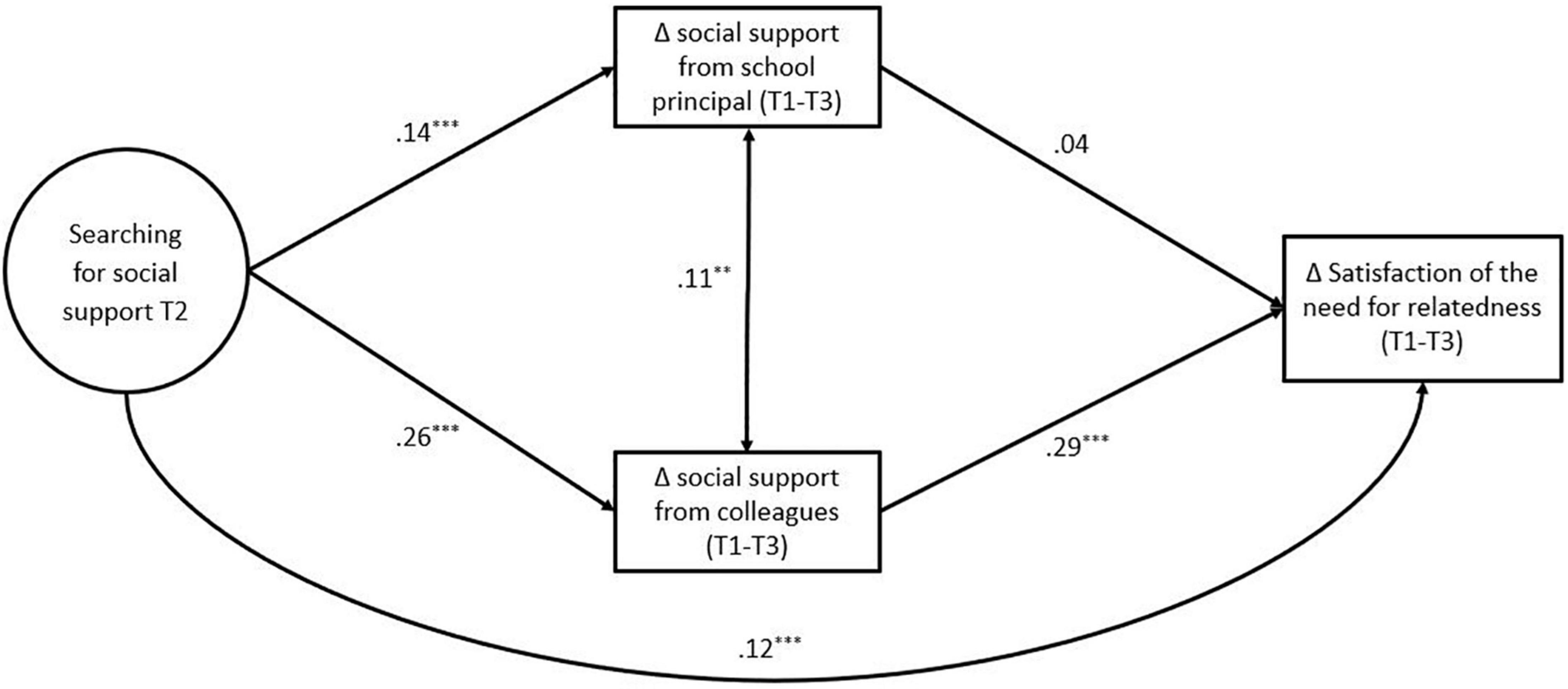

To test our hypothesis, we compared the hypothesized full mediation model with a partial mediation model. The partial mediation model included a direct effect from searching for social support on the change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Scaled Satorra-Bentler χ2 difference tests showed that including this direct effect significantly improved the model fit: Δχ2 (1) = 14.16, p < 0.001. Thus, besides the indirect effect of searching for social support on the change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness, there was also a direct effect between those two variables (see Figure 2). The indirect effects consisted of a positive effect of searching for social support on the change in receipt of social support from the school principal (β = 0.14, p < 0.001) as well as from colleagues (β = 0.26, p < 0.001), and a positive effect of the change in receipt of social support on the change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Yet, the latter positive effect could only be determined for the change in receipt of social support from colleagues (β = 0.29, p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Partial mediation model with standardized regression coefficients. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. T2 = measurement point 2, T1–T3 = residualized change scores of measurement points 1 and 3.

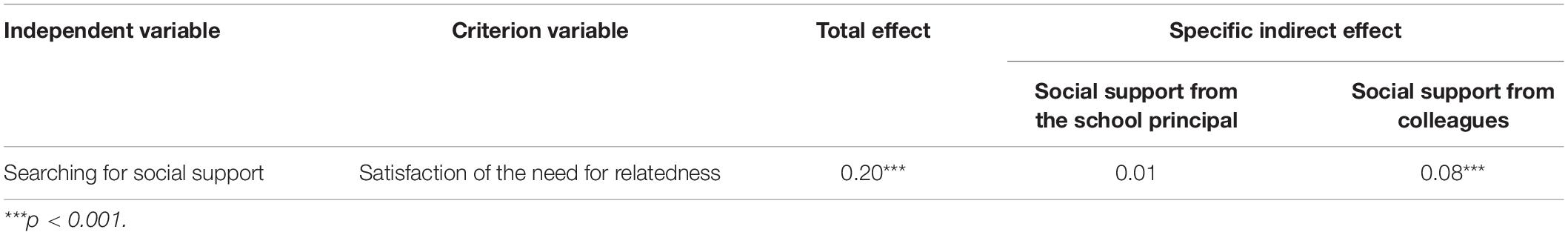

Bootstrap analysis showed a difference between the indirect effects via the receipt of social support from the school principal and via the colleagues (see Table 3). The change in received social support from colleagues mediated the effect of searching for social support on the change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness (β = 0.08, p < 0.001). Yet, the change in received social support from the school principal did not function as mediator of this effect (β = 0.01, p = 0.337). The latter finding is primarily due to the insignificant direct effect of the change in received social support from the school principal on the change in satisfaction of the need for relatedness (β = 0.04, p = 0.374). This gives further clarity to our hypothesis which can only be confirmed for social support from colleagues.

Table 3. Bootstrapped standardized regression coefficients of indirect and total effects of searching for social support on teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness via received social support from the school principal and colleagues.

Discussion

The satisfaction of teachers’ need for relatedness is an important pre-condition for teachers’ wellbeing, job satisfaction, and consequently for their teaching quality. Empirical evidence shows that receiving social support plays a key role in satisfying the need for relatedness. The present study aimed (1) to test whether searching for social support results in an increase in teachers’ satisfaction of the need for relatedness and (2) to examine whether this effect is mediated by an increase of received social support from the school principal and from colleagues. Our results suggest that searching for social support has both a direct and an indirect positive effect on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. The indirect effect consists of teachers increasing the amount of social support they receive from colleagues and from the school principal by searching for it. In turn, this increase in the amount of received social support is positively related to an increase in the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. However, the indirect effect was only mediated by the receipt of social support from colleagues and not from the school principal. Besides the indirect effect, the satisfaction of the need for relatedness also benefits directly from searching for social support, thus, independent of changes in the amount of received social support both from the school principal and from colleagues.

The Benefit of Searching for Social Support

In line with the concept of job crafting (Wrzesniewski and Dutton, 2001; Tims and Bakker, 2010), our results support the assumption that employees can actively adjust their work environment to make it better meet their needs, preferences, and abilities. The finding that teachers can individually and actively contribute to the social support they receive at the workplace and thereby improve the satisfaction of their need for relatedness is an important insight for collaboration in schools. Actual developments in schools such as team-teaching and an increase of part-time working teachers (Appius and Nägeli, 2017) might influence the extent to which teachers search for social support within the school team. Team-teaching involves collaboration between teachers which could intensify the search for social support making it a normal routine of day-to-day practice. An increasing number of teachers in Switzerland that work part-time presumably also affects the exchange of social support (Brägger and Schwendimann, 2022). However, it is rather unclear how this influence might look like. Either working part-time results in less presence within the school team, and consequently in less opportunities to search for social support, or part-time work compels teachers to intensify collaboration which also promotes searching for social support. We argue that it is important to consider such school developments also in the light of their influence on the exchange of social support within school teams.

Searching for social support had a direct as well as an indirect positive effect on the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. This result partly supports previous studies that showed indirect effects of searching for social support on employee outcomes (Tims et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2015). The direct effect found in the present study might be explained by other sources of social support. Because we examined social support explicitly from either the school principal or teaching colleagues, we consequently excluded social support from other sources at schools such as school psychologists and school social workers.

To the best of our knowledge, only one previous empirical study investigated the effects of job crafting on teachers’ basic need satisfaction. The main finding of this study is that job crafting contributed to more basic need satisfaction among teachers (van Wingerden et al., 2017). A nuanced look at the different aspects of job crafting shows that the effects of job crafting on teachers’ basic need satisfaction differ between these aspects. Results suggest that only the aspect “increasing challenging job demands” showed a beneficial relation with basic need satisfaction. The aspect “searching for social support” did not seem to contribute to teachers’ basic need satisfaction. This contradicts the results of the present study and gives reason to further investigate the effects of the different aspects of job crafting.

Receipt of Social Support: Differences Between School Principal and Colleagues

The present study revealed differences between the social support received from the school principal and from colleagues. There might be several reasons for these differences: Distributed and shared forms of leadership have the possibility to arise in school organizations (Harris, 2008; Fuchs and Wyss, 2016). Informal leaders, such as experienced teachers, might occupy a central position within the school team from which they assist and advice their colleagues. Accordingly, previous studies suggested that social relationships within school teams do not reflect the formal organizational structure of the school (Moolenaar, 2012), and that formal advisory roles in the school organization are not always adopted by the formally designated person (Penuel et al., 2010; Spillane and Healey, 2010). Thus, because colleagues are easily accessible and offer competent support, there might not be a need to request support from the school principal. Additionally, there might be other reasons to rather turn to colleagues for social support than to the school principal. Previous research shows that school principals are less frequently involved in day-to-day social interactions between teachers, such as discussing work related issues (Moolenaar et al., 2014). Moreover, a possible explanation could be that school principals might have less available time for such day-to-day social interactions. Thus, teachers might have experienced that their school principal is less available which strengthens them in searching for social support from their colleagues rather than from their school principal. Further, school principals’ responsibility of controlling and evaluating teachers’ performance might play a role in their more remote position toward their teachers (Rothland, 2007). Teachers might want to avoid showing the school principal a need for social support as this could be perceived as a limitation of teacher’s abilities.

The finding that received social support from colleagues was positively related to the satisfaction of teachers’ need for relatedness whereas received social support from the school principal was not, could be explained as follows: The need for relatedness refers to feelings of social connectedness, being a group member, and feeling close with others (Deci and Ryan, 2000). The important role of social support from colleagues in satisfying this need can be expected. However, as the social interaction between school principals and teachers is less close compared to colleagues (Moolenaar et al., 2014), school principals might have less influence on teachers’ satisfaction of the basic need for relatedness. Although this seems to contradict the importance of leadership behavior that aims at the promotion of employees’ basic psychological needs for employees’ functioning (Hetland et al., 2011; Kovjanic et al., 2012), this does not rule out the influence of school principals on the satisfaction of the other basic needs of autonomy and competence. Especially the satisfaction of the need for autonomy seems to benefit from the receipt of social support from the school principal (Maas et al., 2021). Moreover, instead of directly affecting their teachers, school principals might rather exert the influence of their leadership behavior indirectly through adjustments in job demands and job resources which creates opportunities to satisfy teachers’ needs (Vincent-Höper and Stein, 2019). Besides this, our results suggest that school principals display an important aspect of supportive behavior by being responsive to teachers’ requests for social support and providing social support.

Strengths and Limitations

The present study has several strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that examined effects of teachers’ search for social support differentiated by source. By distinguishing social support from the school principal and from colleagues, we could show important differences in relation to searching for social support and the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. These differences shed light on the exchange of social support in school teams and how it can contribute to the satisfaction of teachers’ basic needs.

Second, by using a longitudinal design and residualized change scores we were able to show relationships over time and actual changes in the receipt of social support and the satisfaction of the need for relatedness. Finding these changes even for a long time-interval of approximately 9 months strengthens our findings. Comparable studies used much shorter time-intervals (Tims et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2015). Moreover, by covering almost a whole school year the present study provides valuable insight in the occupational reality of teachers across the school year. Although the longitudinal design also implied that study participants had to fill out three online surveys across one school year which was time consuming, the dropout rate was very low. This led to a large sample size of over thousand teachers: to the best of our knowledge one of the biggest teacher samples in the German speaking part of Switzerland.

Yet, there are also some limitations that are worth mentioning. First, despite the longitudinal design, we cannot draw conclusions about causality. The influence of third variables that explains our results cannot be ruled out (Mackinnon and Pirlott, 2015). Also, short term fluctuations in the receipt of social support and the satisfaction of the need for relatedness could have influenced the changes we demonstrated between the measurement points. Studies that use an experimental design are required to neutralize influences of third variables and short-term fluctuations, and to unfold causal relationships.

Second, by using only self-reports possibly common method variance might have affected our results (CMV; Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, we intentionally used self-reports because we were interested in teachers’ personal experience. Using reports by others for measuring teachers’ search for social support, receipt of social support, and satisfaction of the need for relatedness would be complicated and above that not accurate enough. Moreover, “objective” indicators also have shortcomings, for example, observers’ bias, halo, and stereotype effects (Kerlinger and Lee, 2000).

Conclusion

Previous empirical research showed that the satisfaction of teachers’ need for relatedness depends to a great extent on the receipt of social support at school and is an important precondition for teachers’ wellbeing, job satisfaction, and teaching quality. The present study suggested that teachers can actively contribute to the satisfaction of their need for relatedness by searching for social support. Our results showed that this effect works both directly and indirectly. The receipt of social support from colleagues functioned as a mediator, whereas the receipt of social support from the school principal did not mediate the positive association between searching for social support and need satisfaction. However, teachers’ search for social support was beneficially related to the receipt of social support from both the school principal and colleagues.

Regarding teachers’ daily work practice we conclude that teachers should take opportunity to actively strengthen the social resources they receive at work. This helps to satisfy their need for relatedness, which, in turn, can positively contribute to their wellbeing. Therefore, we encourage teachers to actively request for social support both from their school principal and from their colleagues. In situations in which it might be difficult for some teachers to ask for help, school principals may play an important role by promoting a climate of appreciation and acceptance to reduce such barriers. Open social interactions and strong relationships within a school team are important prerequisites for satisfying the need for relatedness and being able to deal with the high demands in the teaching profession.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://osf.io/k37ef/?view_only=efcfc00b79e445b0a46503d1086805af.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics committee of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University Zurich (Approval Number 17.6.9). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JM performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JM, SS, and RK conducted the data collection and organized the database. All authors contributed to conception and design of the study, manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 100019M_169788/1; Project “Why does Transformational Leadership Influence Teacher’s Health?— The Role of Received Social Support, Satisfaction of the Need for Relatedness, and the Implicit Affiliation Motive”).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ At the time of the data collection not all schools in the German speaking part in Switzerland had an organizational structure which included the formal position of school principal.

- ^ Searching for social support: t(935) = 1.16, p = 0.247, d = 0.090. Standardized residual of received social support from the school principal: t(894) = 0.482, p = 0.630, d = 0.038. Standardized residual of received social support from colleagues: t(897) = 0.081, p = 0.935, d = 0.006. Satisfaction of the need for relatedness: t(900) = 1.961, p = 0.050, d = 0.153.

- ^ Factor analyses are available upon request from the authors.

References

Appius, S., and Nägeli, A. (2017). Schulreformen im Mehrebenensystem. Eine Mehrdimensionale Analyse von Bildungspolitik [School Reforms in a Multi-Level System. A Multidimensional Analysis of Education Policy]. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien.

Bakker, A. B., and Oerlemans, W. G. M. (2019). Daily job crafting and momentary work engagement: a self-determination and self-regulation perspective. J. Vocat. Behav. 112, 417–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2018.12.005

Bakker, A. B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., and Sanz Vergel, A. I. (2016). Modelling job crafting behaviours: implications for work engagement. Hum. Relat. 69, 169–189. doi: 10.1177/0018726715581690

Barnette, J. J. (2000). Effects of stem and Likert response option reversals on survey internal consistency: if you feel the need, there is a better alternative to using those negatively worded stems. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 60, 361–370.

Baumeister, R. F., and Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529.

Brägger, M., and Schwendimann, B. A. (2022). Entwicklung der arbeitszeitbelastung von lehrpersonen in der Deutschschweiz in den letzten 10 jahren [Development of the working time load of teachers in German-speaking Switzerland over the last ten years]. Präv. Gesundheitsförderung 17, 13–26.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., and Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2015). Productive and counterproductive job crafting: a daily diary study. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 20, 457–469. doi: 10.1037/a0039002

Desrumaux, P., Lapointe, D., Ntsame Sima, M., Boudrias, J.-S., Savoie, A., and Brunet, L. (2015). The impact of job demands, climate, and optimism on well-being and distress at work: what are the mediating effects of basic psychological need satisfaction? Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 65, 179–188. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2015.06.003

Federal Statistical Office (2018). Personal von Bildungsinstitutionen [Staff of educational institutions]. Neuchâtel: Bundesamt für Statistik.

Fernet, C., Austin, S., Trépanier, S.-G., and Dussault, M. (2013). How do job characteristics contribute to burnout? Exploring the distinct mediating roles of perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 22, 123–137. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2011.632161

Fuchs, M., and Wyss, M. (2016). “Geteilte führung bei schulleitungen an volksschulen [shared leadership in school management],” in Leadership in der Lehrerbildung [Leadership in Teacher Education], eds M. Heibler, K. Bartel, K. Hackmann, and B. Weyand (Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press), 87–101.

Graham, J. W., and Coffman, D. L. (2012). “Structural equation modeling with missing data,” in Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling, ed. R. H. Hoyle (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 277–295.

Greenglass, E., Schwarzer, R., Jakubiec, D., Fiksenbaum, L., and Taubert, S. (1999). “The proactive coping inventory (PCI): a multidimensional research instrument,” in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Stress and Anxiety Research Society, dec 1999, Cracow, 1–18.

Harmsen, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., Maulana, R., and van Veen, K. (2018). The relationship between beginning teachers’ stress causes, stress responses, teaching behaviour and attrition. Teach. Teach. 24, 626–643. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1465404

Hetland, H., Hetland, J., Schou Andreassen, C., Pallesen, S., and Notelaers, G. (2011). Leadership and fulfillment of the three basic psychological needs at work. Career Dev. Int. 16, 507–523. doi: 10.1108/13620431111168903

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscipl. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Kerlinger, F. N., and Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of Behavioural Research, 4th Edn. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt.

Knoll, N., and Kienle, R. (2007). Fragebogenverfahren zur Messung verschiedener Komponenten sozialer Unterstützung: ein Überblick. Z. Med. Psychol. 16, 57–71.

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., Jonas, K., Van Quaquebeke, N., and van Dick, R. (2012). How do transformational leaders foster positive employee outcomes? A self-determination-based analysis of employees’ needs as mediating links. J. Organ. Behav. 33, 1031–1052. doi: 10.1002/job.1771

Lai, K. (2018). Estimating standardized SEM parameters given nonnormal data and incorrect model: methods and comparison. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscipl. J. 25, 600–620. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2017.1392248

Mackinnon, D. P., and Pirlott, A. G. (2015). Statistical approaches for enhancing causal interpretation of the M to Y relation in mediation analysis. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 19, 30–43. doi: 10.1177/1088868314542878

MacKinnon, D., Lockwood, C., and Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multiv. Behav. Res. 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901

Maas, J., Schoch, S., Scholz, U., Rackow, P., Schüler, J., Wegner, M., et al. (2021). School Principals’ Social Support and Teachers’ Basic Need Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Job Demands and Job Resources. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Moolenaar, N. M. (2012). A social network perspective on teacher collaboration in schools: theory, methodology, and applications. Am. J. Educ. 119, 7–39. doi: 10.1086/667715

Moolenaar, N., Daly, A. J., Sleegers, P. J. C., and Karsten, S. (2014). “Social forces in school teams: how demographic composition affects social relationships,” in Interpersonal Relationships in Education: From Theory to Practice, eds D. Zandvliet, P. den Brok, T. Mainhard, and J. van Tartwijk (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers).

Penuel, W. R., Kenneth, A. F., and Krause, A. (2010). “Between leaders and teachers: using social network analysis to examine the effects of distributed leadership,” in Social Network Theory and Educational Change, ed. A. J. Daly (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 159–178.

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., and Schaufeli, W. B. (2015). Job crafting in changing organizations: antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 20, 470–480. doi: 10.1037/a0039003

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., and Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher, K. J., and Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 40, 879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

R Core Team (2018). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (Computer Software Package). Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5-12 (BETA). J. Stat. Softw. 48, 1–36.

Rothland, M. (2007). Belastung und Beanspruchung im Lehrerberuf. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Sarason, B. R., Shearin, E. N., Pierce, G. R., and Sarason, I. G. (1987). Interrelations of social support measures: theoretical and practical implications. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 52, 813–832.

Sarason, I. G., Sarason, B. R., and Pierce, G. R. (1994). “Relationship-specific social support: toward a model for the analysis of supportive interactions,” in Communication of Social Support: Messages, Interactions, Relationships, and Community, eds B. R. Burleson, T. L. Albrecht, and I. G. Sarason (London: Sage Publications, Inc), 91–112.

Schulz, U., and Schwarzer, R. (2003). Soziale unterstützung bei der krankheitsbewältigung: die berliner social support skalen (BSSS) [Social support in coping with illness: the Berlin Social Support Scales]. Diagnostica 49, 73–82. doi: 10.1026//0012-1924.49.2.73

Shrout, P. E., and Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 7, 422–445. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.4.422

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2018). Job demands and job resources as predictors of teacher motivation and well-being. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 21, 1251–1275. doi: 10.1007/s11218-018-9464-8

Smith, P., and Beaton, D. (2008). Measuring change in psychosocial working conditions: methodological issues to consider when data are collected at baseline and one follow-up time point. Occup. Environ. Med. 65, 288–296. doi: 10.1136/oem.2006.032144

Spillane, J. P., and Healey, K. (2010). Conceptualizing school leadership and management from a distributed perspective: an exploration of some study operations and measures. Elem. Sch. J. 11, 253–281. doi: 10.1086/656300

Tims, M., and Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 36, 1–9. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 80, 173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 18, 230–240. doi: 10.1037/a0032141

Uchino, B. N. (2009). Understanding the links between social support and physical health: a life-span perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 4, 236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x

van den Broeck, A., Vansteenkiste, M., Witte, H., Soenens, B., and Lens, W. (2010). Capturing autonomy, competence, and relatedness at work: construction and initial validation of the work-related basic need satisfaction scale. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 83, 981–1002. doi: 10.1348/096317909X481382

van Wingerden, J., Bakker, A. B., and Derks, D. (2017). Fostering employee well-being via a job crafting intervention. J. Vocat. Behav. 100, 164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.008

Vincent-Höper, S., and Stein, M. (2019). The role of leaders in designing employees’ work characteristics: validation of the health- and development-promoting leadership behavior questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 10:1049. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01049

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., and Wu, W. (2012). “Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling,” in Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling, ed. R. H. Hoyle (New York, NY: The Guilford Press), 209–231.

Williams, R. H., Zimmerman, D. W., and Mazzagatti, R. D. (1987). Large sample estimates of the reliability of simple, residualized, and base-free gain scores. J. Exp. Educ. 55, 116–118. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1987.10806443

Keywords: searching for social support, need for relatedness, school teachers, school principals, job crafting

Citation: Maas J, Schoch S, Scholz U, Rackow P, Schüler J, Wegner M and Keller R (2022) Satisfying the Need for Relatedness Among Teachers: Benefits of Searching for Social Support. Front. Educ. 7:851819. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.851819

Received: 10 January 2022; Accepted: 24 February 2022;

Published: 17 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ibrahim Duyar, Arkansas State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Seung-Hwan Ham, Hanyang University, South KoreaBronwyn MacFarlane, University of Arkansas, United States

Copyright © 2022 Maas, Schoch, Scholz, Rackow, Schüler, Wegner and Keller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasper Maas, ai5uLm0ubWFhc0Bmc3cubGVpZGVudW5pdi5ubA==

Jasper Maas

Jasper Maas Simone Schoch

Simone Schoch Urte Scholz

Urte Scholz Pamela Rackow

Pamela Rackow Julia Schüler

Julia Schüler Mirko Wegner

Mirko Wegner Roger Keller

Roger Keller