- Department of Foreign Languages, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa

This manuscript investigates to what extent the use of corpora could help translation trainees while translating from Arabic into English and vice versa. Forty Yemeni trainees, who were enrolled in an advanced course in Arabic-English translation during the academic year 2020, participated in the study. They participated in translation projects from which the data for this study was collected, using thinking aloud protocols and computational observation. The translation process was investigated using the translation process software Transalog, an eye-tracking software and the screen recording software Screen-O-Matic. This kind of computational observation enabled a researcher to discover the extent to which the participants were able to employ corpora in their translation projects. At the end of the study, the participants were given a questionnaire with the aim of finding out their perceptions toward the use of corpora in their translation projects, and toward the project-based training approach adopted in the study. The findings of the translation process indicated that the trainees employed various kinds of corpora in their translation projects. Results from the questionnaire showed that the trainees have very positive attitudes toward the progress in their instrumental translation sub-competence, the utilization of corpora tools, and the project-based training approach adopted in this study.

Introduction

Translation into the second language has been a matter of heated discussion and debate. While one group of scholars argue that only a native speaker can translate into his/her mother tongue, others emphasize that this is a far-fetched goal due to the lack of native speakers in the second language who are equally competent in the first source language and duly familiar with its culture (Campbell, 2014:57). In addition, it is hard to find native-speaker translators who can meet the globally growing demands for the translation and localization industry in all languages. Adab (2005:227) therefore correctly asserts that the concept of translating with the level of nuance of a native speaker is “a meme which is fast becoming unenforceable and impractical in this era of globalized communications and intercultural exchanges”. For example, the mixing of standard English and other European languages, which has led to the emergence of “European English” makes it difficult to say precisely who is a native speaker. Similarly, the localization industry lists several varieties for each language. Arabic, for instance, has several varieties such as Saudi Arabic, Yemeni Arabic, Egyptian Arabic, and the like. It would be hard to find translators for each variety should a company require a translation for its products with a localized (i.e., colloquial) flavor. Thelen (2005:248) for instance, has opted for the concept of “real speaker” introduced by Cascio (2001). In other words, translation should not be monopolized by native speakers, and the competence of non-native speaker translators should not be undermined (Rogers, 2005:270). In this age of the fourth industrial revolution, translators are increasingly more prepared and confident to translate into the target language than ever before. Tremendous developments in the fields of translation and linguistics technology have greatly facilitated the role of translators and enabled them to produce target texts that are clearer and more nuanced. It is incumbent upon training institutions to incorporate those technologies into syllabi to keep trainees abreast of the demands of the fast-growing language industry. Translator and interpreter training is an interdisciplinary field that has evolved alongside with and benefited from linguistics, cultural studies, translation studies; and educational, philosophical, and computational approaches. Thus, training institutions must synergize various translation approaches in their programs without prejudice. This kind of interdisciplinarity in training is necessary for the enhancement of the competence of translator trainees. This manuscript advocates the view that an approach which has not received adequate attention in translator training programs, especially in the Arab World, is the computational model. When they first emerged, the use of computer-assisted translation tools was not enthusiastically hailed by translators and language practitioners on the pretext that “computer facilities […] threatened to change the image of translation from an art to a technique” (Carrové, 1999:84). The last decade of the 20th century, however, witnessed a paradigm shift in the fields of translation studies and computational linguistics from fully-automated translation to computer-assisted translation. As a result, computer assisted translation (CAT) has been widely adopted in translator training. Despite the poor quality of some automated translation systems, the role of CAT technology in translation pedagogy and translation industry cannot be denied. CAT tools should be viewed as a translator’s aid, and not as an enemy or substitute for a human translator. An example of CAT tools is translation memories (TMs), which can store translations for future use (Thawabteh, 2013). A translation memory can save millions of translated texts, sentences, and terminologies, which can be automatically retrieved for use in the future. TMs can either provide an exact translation (full match) or a partial translation (fuzzy match). In a sense, a TM is a parallel corpus that includes a source text and its translation in one or more languages.

Research Objectives and Questions

This study is action-based research which uses a project-based approach to allow participants to work on genuine translation projects and to find out the degree to which they create corpora and utilize them in their translation. In doing so, this study gives equal weight to both the process and product of translation. Due to the exploratory nature of this study, research questions rather than hypotheses were investigated. This study attempts to answer the following questions:

1. To what extent do translation trainees employ corpora tools in their translations?

2. Do translation trainees have positive perceptions toward corpora tools?

3. Is there any correlation between the perceptions of the participants and their professional rank?

4. Is there any correlation between the perceptions of the participants and their computer skills?

Literature Review

In fact, the literature abounds with reports in which the benefits of translation technology are espoused. The attitudes of the trainees toward the use of CAT were investigated in many studies including (Çetiner, 2018; Mahfouz, 2018; Heinisch and Iacono, 2019; Mohammed et al., 2020). However, few empirical studies have explored the use of corpora tools in the translation classroom and translation workplace, especially in the context of Arabic-English translation. For example, Alotaibi (2016) attempted to compile an Arabic-English parallel corpus (AEPC) for the purpose of translation training as well as the design of an Arabic-English concordance tool. The corpus is based on human translations covering different text types and rich metadata. The corpus was supposed to include ten million words in its first phase. A web interface with a bilingual concordance tool was created to enable users to navigate the content of the AEPC in both English and Arabic.

Ahmed and Nürnberger (2008) presented a corpus-based approach for a word-definition disambiguation method to be used in automatic translations from Arabic into English. The study used a statistical model to analyze parallel corpora. The aim was to use the corpora in a word-definition disambiguation task. The findings of the study indicated that the approach has the potential to provide useful semantic information that can assist in improving translation equivalents for polysemous items.

Similarly, Ahmed et al. (2009) adopted a corpus-based approach to improve cross-language information retrieval between Arabic and English. They used an analysis tool for Arabic query terms and for definitions of ambiguous terms. Based on co-occurrence statistical data and the web, the correct meaning of the ambiguous query terms was selected.

In a similar vein, Brierley and El-Farahaty (2019) attempted a corpus-based analysis of the Arabic word karama and its collocations in an Arabic-English corpus. The morphological variants of karama were identified and parallel concordance lines were scrutinized. The study concluded that when karama is used as an indefinite noun, it was rendered as “dignity”. However, the definite form of the word (i.e., al-karāma) is often rendered as “treatment” followed by a qualifying adjective.

In so far as second language writing (SLW) is concerned, Zaki (2020) investigated how inducing self-correction in corpus-based tasks enhances the writing skills of learners of Arabic as a foreign language. Corpus-based tasks taken from a learner corpus were given to intermediate level Arabic learners to encourage them to think about their errors and to correct them. The study concluded that the use of such a corpus not only enables learners to self-correct their errors, but also encourages them to explore new avenues of understanding in the natural structures of Arabic.

Corpus-based data-driven learning (DDL) was also examined in a few studies. Abuhakema et al. (2008), for instance, compiled a learner’s corpus of Arabic which includes writing tasks from intermediate and advanced-level Arabic students. The study also developed a tagset for the annotation of errors based on the French Interlanguage Database (FRIDA) tagset (Granger, 2003) and performed a Computer-aided Error Analysis (CEA) on the collected data. The study concluded that intermediate speakers make many phonological/orthographical errors (e.g., the glottal stop known as hamza). Advanced learners, on the other hand, make errors in word order and cohesion. The study also concluded that intermediate and advanced learners make lexico-grammatical errors and often have difficulties with the use of morphologically marked agreement. Other empirical studies that were conducted on other languages include Popescu’s study (Popescu, 2013) which examined the error patterns produced by Romanian English as a Foreign Language (EFL) students in a business and public administration course. Based on the translations of thirty students using a variety of texts, a learner’s corpus of 15,000 words was created. The corpus shows that three main kinds of errors are made by EFL students, namely, comprehension, linguistic, and translation errors. Similarly, Jantunen (2002) dealt with the use of comparable corpora in translation studies with specific reference to the Translational English Corpus (TEC) and the Corpus of Translated Finnish (CTF). The study focused on phenomena such as the representation and objectivity of translation corpora as well as their applications in translators’ training and work. Additionally, Jingang (2016) investigated the use of parallel corpora as teaching and learning resources and its significance in the study of translation universals, translation norms and a translator’s style.

Most of the above studies are primarily concerned with the use of corpora in the context of language learning rather than using them for translation purposes. Even these studies that have been conducted in a translation context tend to focus on the automation of corpora, rather than enabling translators to compile and utilize them as a way of optimizing translation projects. The current study is different from the above studies because it not only highlights the significance of using various rarely-used corpora in the Arabic-English translation context, but it also aims to enable trainees to create their own corpora. Available corpora are not universal solutions that can meet all the needs of a translator. Translators will always be required to create their own corpora should they embark on a project for which few materials are available. A translation project might require the use of customized mono-, bi- and multi-lingual corpora. Corpus-based studies have therefore been given adequate attention in the field of Applied linguistics in general and in translation studies in particular. The next section provides a brief overview of the corpus-based translation model and explains the types of corpora that are related to this study.

Corpus-Based Translation Studies

A remarkable phase in the integration of computer-assisted translation and translator and interpreter training began in the 1990s when translation scholars collected several corpora of translated texts to determine the existence of certain translation universals as well as the distinctive patterns in translated texts (Granger, 2003:18, 19). According to Baker (1993:242), “the availability of large corpora of both original and translated text, together with the development of a corpus-driven methodology will enable scholars to uncover the nature of translated texts as a mediated communicative event”. The corpus-based model grew in popularity and eventually shifted the paradigm in translation studies (Bendazzoli and Sandrelli, 2009:1). It was widely adopted by scholars such as (Otman, 1991; Munday, 1998; Kenny, 1999; L’Homme, 2000; Zanettin, 2001). Undoubtedly, the integration of a corpus-based translation model in training translators plays a vital role in the development of their competence. Various corpora have been created to satisfy a variety of instructional needs. Insofar as the present study is concerned, the following types of corpora are relevant: monolingual comparable corpora, bilingual comparable corpora, and parallel corpora.

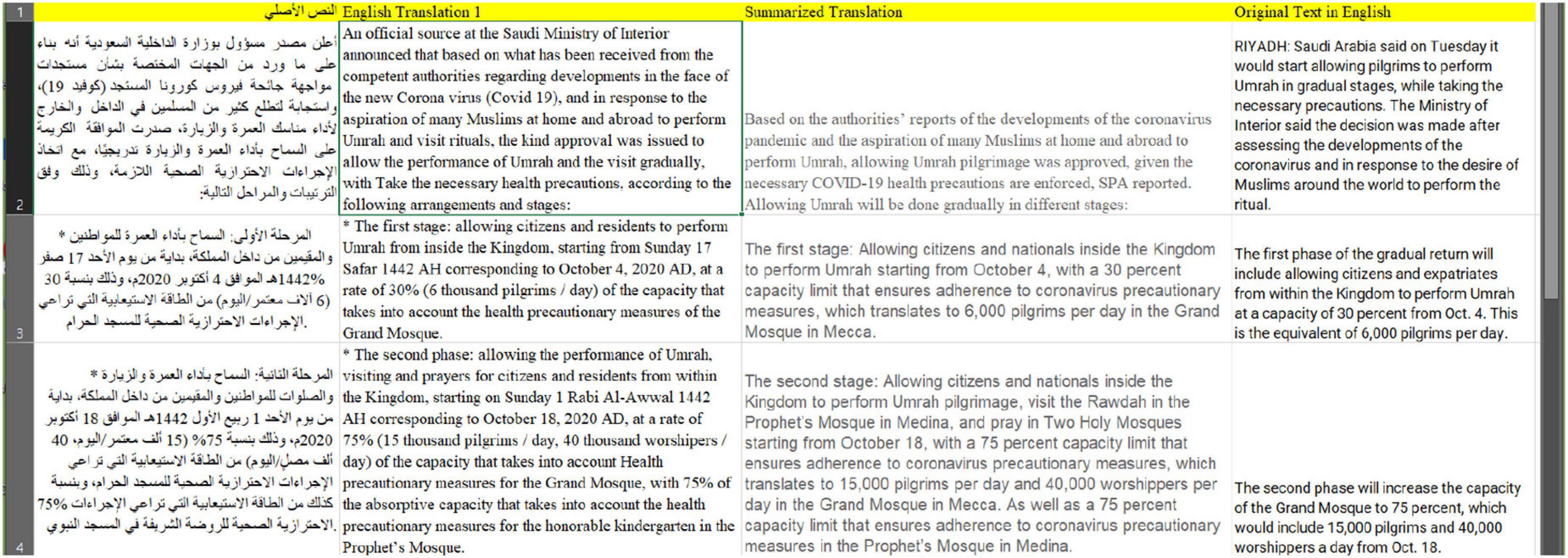

A monolingual comparable corpus includes texts in one language only. That is, it contains texts which are originally written in a target language and texts which are translated into it from source languages (Baker, 1995; Laviosa, 1997; Zanettin, 1998). A monolingual corpus can assist translators to examine “the linguistic nature of translated text, independently of the source language” (Zanettin, 1998:1). Presently, monolingual corpora can be easily compiled from sources such as comparable documents and news stories which are written in the target language and those translated into it from many other languages. This type of corpus is common, and the content can be tagged to investigate morphological, syntactic, or semantic issues. It can also be used to discern the usage of lexical items, collocations, and frozen expressions in context. Should a legal translator, for instance, come across the expression “bona fide” in a text that needs to be translated into Arabic, s/he would find limited meanings for this expression in a dictionary. Investigating the expression in the British National Corpus, however, provides the translator with various equivalents for the expression in context. Thus, the translator can choose the meaning that best suits the context. An example of a monolingual comparable corpus appears in Figure 1.

Although these comparable texts are not exact translations of the source text, a cursory look at them shows many phrases and expressions which are equivalent to phrases and expressions in the source text. Translators may also come across certain standard idiomatic or technical expressions. In addition, such a corpus can be used as a reference tool, as complement to dictionaries and grammar. A monolingual corpus enables the translator/user to determine how an expression is used in context, thereby increasing the chance of learning. The corpus in Figure 1 can be used as a reference tool which provides users with valuable information unlike dictionaries. In this monolingual corpus, a translator can find exact and fuzzy matches for most of the words, expressions and even sentences in the source text, as shown in Table 1.

The monolingual corpus is also ideal for studying the features of certain text types or genres. Monolingual corpora can be compiled using desktop software and web-based tools such as Antconc. The easiest way, however, is to use the internet as a corpus. Tools such as Sketch Engine and the Web as Corpus can be easily used to compile web-based corpora.

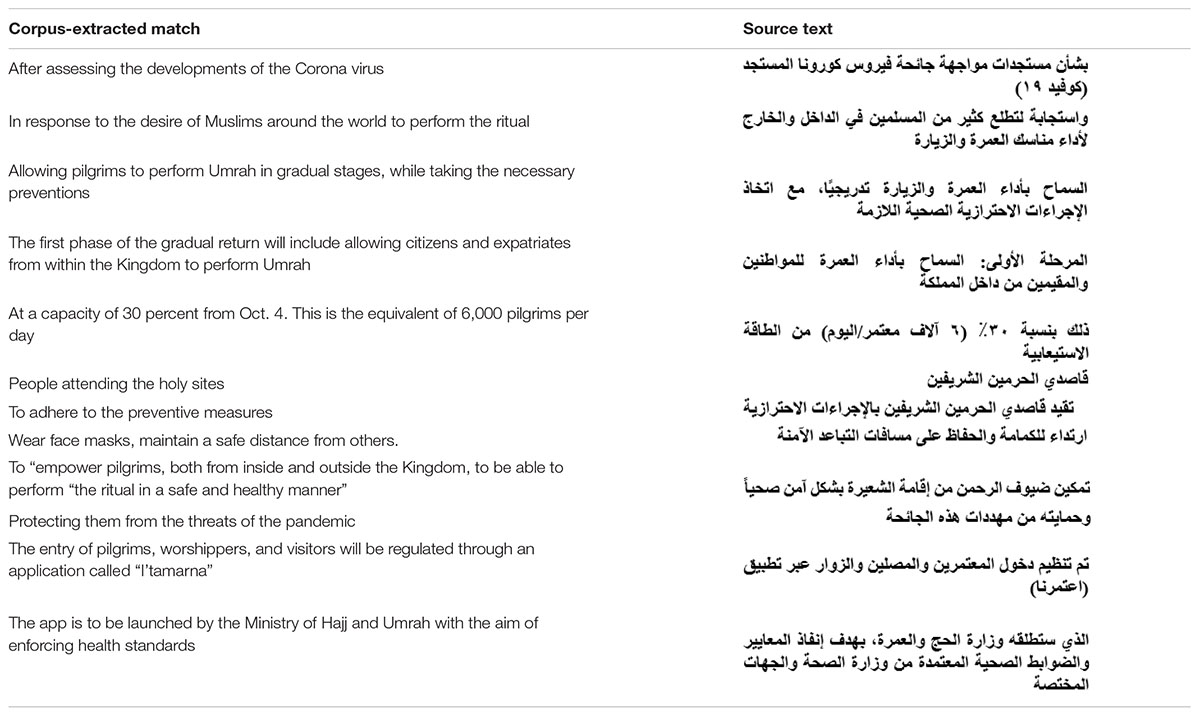

The second type of corpus relevant to this study is the bilingual comparable corpus. In this type of corpus, bilingual texts are selected from different sources (e.g., online, or scanned books/materials) based on a number of criteria such as similarity of topic and communicative function (Zanettin, 1998; Aston, 1999). Texts in a bilingual comparable corpus generally belong to socio-linguistically similar genres. In a sense, bilingual comparable corpora are an extension of traditional parallel texts in translation (Hartmann, 1994) which are “typically unrelated except by the analyst’s recognition that the original circumstances that led to the creation of the two [sets of] texts have produced accidental similarities” (Zanettin, 1998:2). An example of a bilingual comparable corpus is the Wikipedia-based corpus about the COVID-19 pandemic (COVID-19) shown in Figure 2. The corpus was created by Wordfast Autoaligner. It shows a similarity degree between zero and 76%.

A comparable corpus allows the translator to better understand source texts and produce natural and standard translated versions in the target language. It is highly beneficial in domain-specific translation tasks such as technical translation, legal translation, localization, and the like. It also assists translators when identifying prototypical features of a particular text, such as text structure and register conventions (Zanettin, 1998; Aston, 1999; Gavioli, 2005).

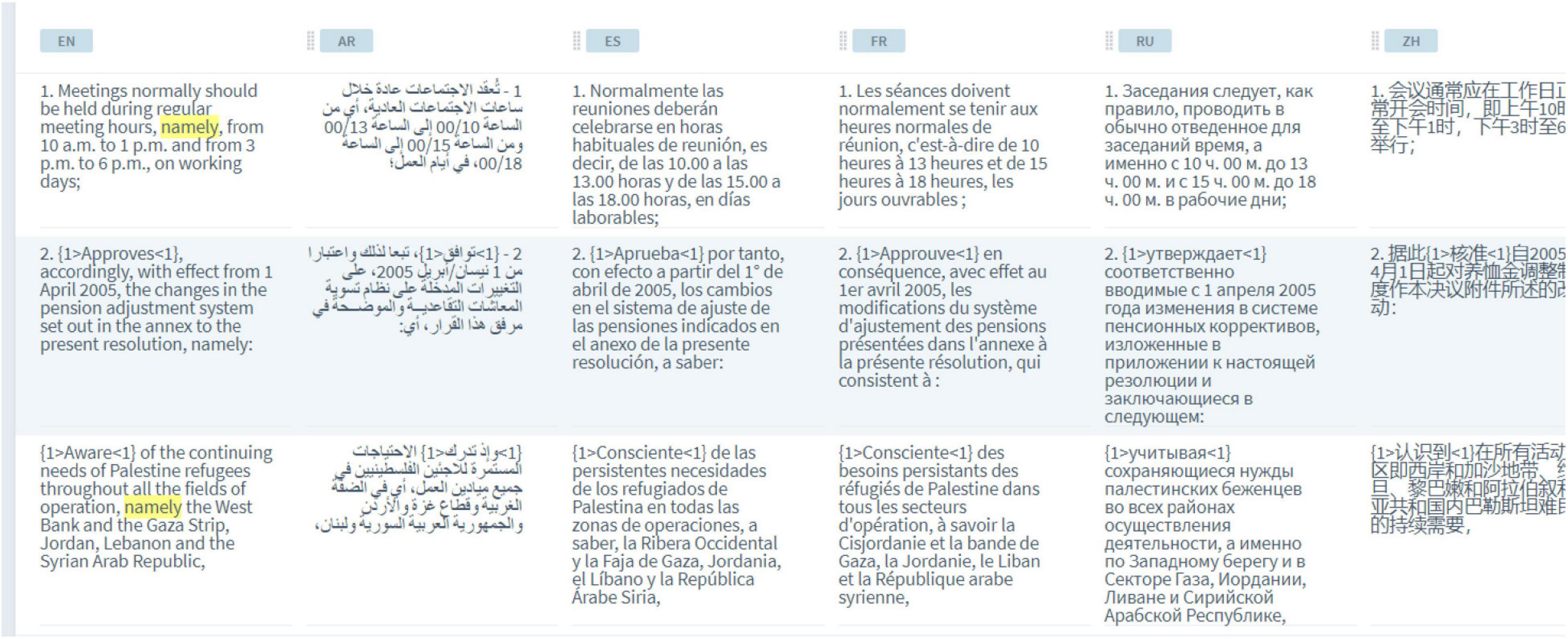

The third type of corpus investigated in this study is the parallel corpus, which consists of texts in a source language and their translations into one or more languages. An example of a parallel corpus is the United Nations (UN) corpus which is published in the official languages of the United Nations, as shown in Figure 3.

A parallel corpus may assist translators to identify equivalent terms and expressions. The alignment of texts, as seen in Figure 3, not only allows the translators and language practitioners to render various translations of an expression, but also perceive general patterns (Zanettin, 1998). A parallel corpus can therefore be used to translate terminology and phraseology with a high degree of precision. It may also provide “a systematic translation strategy for linguistic structures which have no direct equivalents in the target language” (McEnery and Xiao, 2005; Xiao and Hu, 2015). Additionally, it can be used as an effective tool in contrastive grammar/linguistics, or in the study of discourse structures and markers in two or more languages. Moreover, it is an ideal resource for the investigation of some translation universals such as explicitations and implicitations. Furthermore, a parallel corpus can play a vital role in the training of translators. It can be used to examine an array of translation errors and problems. As Bowker (2002:19) observes, a parallel corpus that includes trainees’ translations serves as a record to detect potential problems and thus guides teaching practices. A text of a particular genre and its translations by different students can be aligned and standardized with the help of a concordance. This forms a learner’s parallel corpus and thus highlights the potential translation problems students might encounter. The corpus can also show whether certain problems or errors are specific to individual students, or they affect the entire class. Moreover, a learner corpus may include the translations of a group of students over a period of time. Such a longitudinal corpus helps teachers track students’ progress over a semester, or an entire course. Teachers can identify any language and translation problems which may or may not have been resolved during the course (Bowker, 2002:20). A parallel corpus can also be domain-specific (e.g., legal or technical). This kind of corpus is highly beneficial in the context of translator training. It can be used to determine whether the errors made by translators are genre-specific, or they are recurring in other genres.

In a word, all types of corpora can be exceedingly beneficial to the translator as they enhance the acceptability of the target text and save the time of the translator and the client. However, the incorporation of corpora tools and the use of corpus-based data-driven learning in higher education training institutions in the Arab world have not received adequate attention yet. We therefore investigate the role this technology-enhanced model can play in the translation process as well as in the enhancement of the instrumental competence of translation trainees using a project-based training approach that is more oriented toward the trainees themselves, as shown in “Project-Based Training”.

Project-Based Training

Project-based learning is a trainee-centered method that is widely employed in a variety of training and professional contexts, including translation training. It is based on the premise that students or trainees learn best through experience. This means that students spend an extended period of time engaged in authentic projects. As such, it is founded on the concepts of active and meaningful learning. Learners are no longer passive recipients of knowledge; they are active participants in the learning process and they construct their learning autonomously and collaboratively. As a result, the teacher’s role is primarily that of a facilitator. Project-based learning in translation pedagogy is thus inspired by learning theories used in other fields, such as social constructivism, postmodernism, self-directed learning, enactive cognitive science, complexity theory, and transformational educational theory, as well as the capability approach (Kiraly, 2012; Havenga and De Beer, 2016). According to Markham (2011:38) project-based learning “integrates knowing and doing. Students learn knowledge and elements of the core curriculum, but also apply what they know to solve authentic problems and produce results that matter. PBL students take advantage of digital tools to produce high quality, collaborative products”.

Project-based learning is founded on the principle of learning ownership. Students are more motivated and take more responsibility for their own learning when they are working on projects. Instead of relying solely on the lecturers, students complete projects in which they plan and organize their group learning activities, conduct assessments or research, solve problems, and synthesize information (Apandi and Afiah, 2019:103). They are fully accountable for the entire production cycle, from preparation and pre-translation through production and delivery to the client. In contrast to traditional training, project-based translation training focuses on authentic translation tasks, encourages trainees to think critically and necessitates continuous reflection on certain tasks, problems and translation processes (Bell, 2010; Rotherman and Willingham, 2010; Havenga and De Beer, 2016). Projects allow students to explore, assess, interpret, and synthesize information with the goal of achieving a variety of learning outcomes. Furthermore, projects are likely to boost trainees’ confidence and self-direction. Projects allow them to build and strengthen their organizational and research skills, as well as their communication and teamwork skills with their peers and negotiation skills with clients. Students learn to use a variety of translation, linguistic and text-processing technological tools relevant to the various stages of translation during the project’s implementation. As Bell (2010:42) points out.

An authentic use of technology is highly engaging to students because it taps into their fluency with computers. Students participate in research using the Internet. During this phase of PBL, students learn how to navigate the Internet judiciously, as well as to discriminate between reliable and unreliable sources.

Another advantage of project-based training lies in the assessment and evaluation of trainees’ performance. Students are evaluated mostly based on their numerous responsibilities in the project, rather than their performance in written exams or summative activities. Project-based learning “refocuses education on the student rather than the curriculum, rewarding intangible assets such as drive, passion, creativity, empathy, and resiliency” (Markham, 2011:38). These cannot be taught in a textbook and must be learned via experience. Project-based learning can provide students and teachers with such experience.

Methodology

This study employs mixed qualitative and quantitative methods for the collection of data. To be more precise, observational research methods and questionnaires are used in this study. The participants were (40) translation trainees enrolled in an advanced translation course at Taiz University in the Republic of Yemen during the academic year 2020. The course includes both student translators and students auditing the course, and thus the background and experience of the participants were varied. This did not present a problem because all participants in the course have not been taught CAT tools before. The participants did not constitute a homogeneous group, and therefore the diversity of the participants enabled a better understanding of the translation process.

Observation

Observation was conducted on five of the participants. The texts chosen for computer observation are all parts of genuine translation projects the participants completed as part of the course. The projects included a media text for a research project, a biography translation for Wikipedia, and an official communiqué to travel agencies concerning the resumptions of Muslim Umrah (non-obligatory, or “lesser pilgrimage”) and Hajj (obligatory pilgrimage) by Saudi authorities in the aftermath of COVID-19 related lockdowns.

The participants were encouraged to use whatever tools they had at their disposal. When they completed the first text, they had not yet been given any training in the use of CAT or corpora tools. The participants assigned to do the initial translation were asked to do the translation via a computer equipped with three software programs, namely, Translog, Screencast-O-Matic and Gaze recorder. The former is a translation process recording program used to obtain quantitative results about user activity. The second is a screen recording software that can capture all moves and think-aloud verbalizations on the computer and save them in a video format. The third is an eye-tracking software that can track the movement of the eyes during the translation process. The data collection consisted of three steps: preparing the participants; the translation process via the abovementioned software; and, finally, the questionnaire. During the first phase, the participants received intensive training to familiarize them with the three software. All participants became acquainted with the use of thinking aloud protocols (TAPs) as an observational method. They were then asked to do a demo exercise in which they translated a text and verbalized their thoughts. Such a demo was necessary to train participants to speak freely during the translation process. The participants were asked to translate the texts in the typical scenario of the working conditions of translators. While the translation process involves many steps, this study investigated to what extent the participants employ corpora in their translation process, and whether they can create a corpus relevant to an ongoing project. The description of other processes is beyond the scope of this study.

Questionnaire

This study used a 19-item questionnaire to determine the attitudes of trainees in the course toward the use of monolingual, comparable, and parallel corpora in translation. The questionnaire encompassed three sections. The first section consisted of 10 five-point Likert items, aimed at identifying the cohort of respondents’ attitudes toward their instrumental or technological sub-competence in general. The second section (also five-point Likert items) aimed at identifying their attitudes toward the actual use of corpora tools. The third section included 4 items that dealt with the project-based training approach used in the course. The questionnaire was administered during the academic year 2020. Firstly, it was verified for its content and validity by two senior colleagues from Taiz University in Yemen, and two more experts (one from the University of the Western Cape, South Africa and one from Aden University, Yemen). The questionnaire was created by Google Forms and the link was sent to the respondents for completion. Finally, the data collected were computed and analyzed using a statistical software named (PSPP). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to find the reliability coefficient of the questionnaire. The values for the alpha coefficient were (0.91) for the entire instrument, (0.91) for the first section of the instrument, (0.76) for the second section, and 0.85 for the third section. These values indicate acceptable levels of reliability.

Findings

Findings From Computational Observation

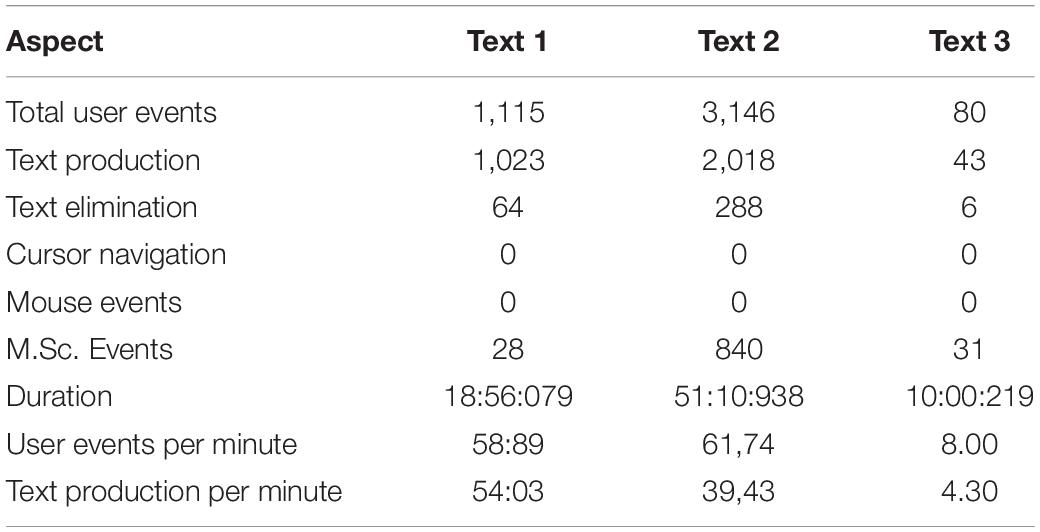

When addressing the first question; to what extent do translation trainees employ corpora tools in their translations, TAPs and computer observation via Translog, Gaze Recorder and Screencast-O-Matic were used to analyze the translation process of three texts. Table 2 provides various user events as captured by Translog.

The first text used in this study was translated by the trainees as a part of a project that was completed before they were introduced to corpora tools. The linear representation of the translation process appears in Figure 4.

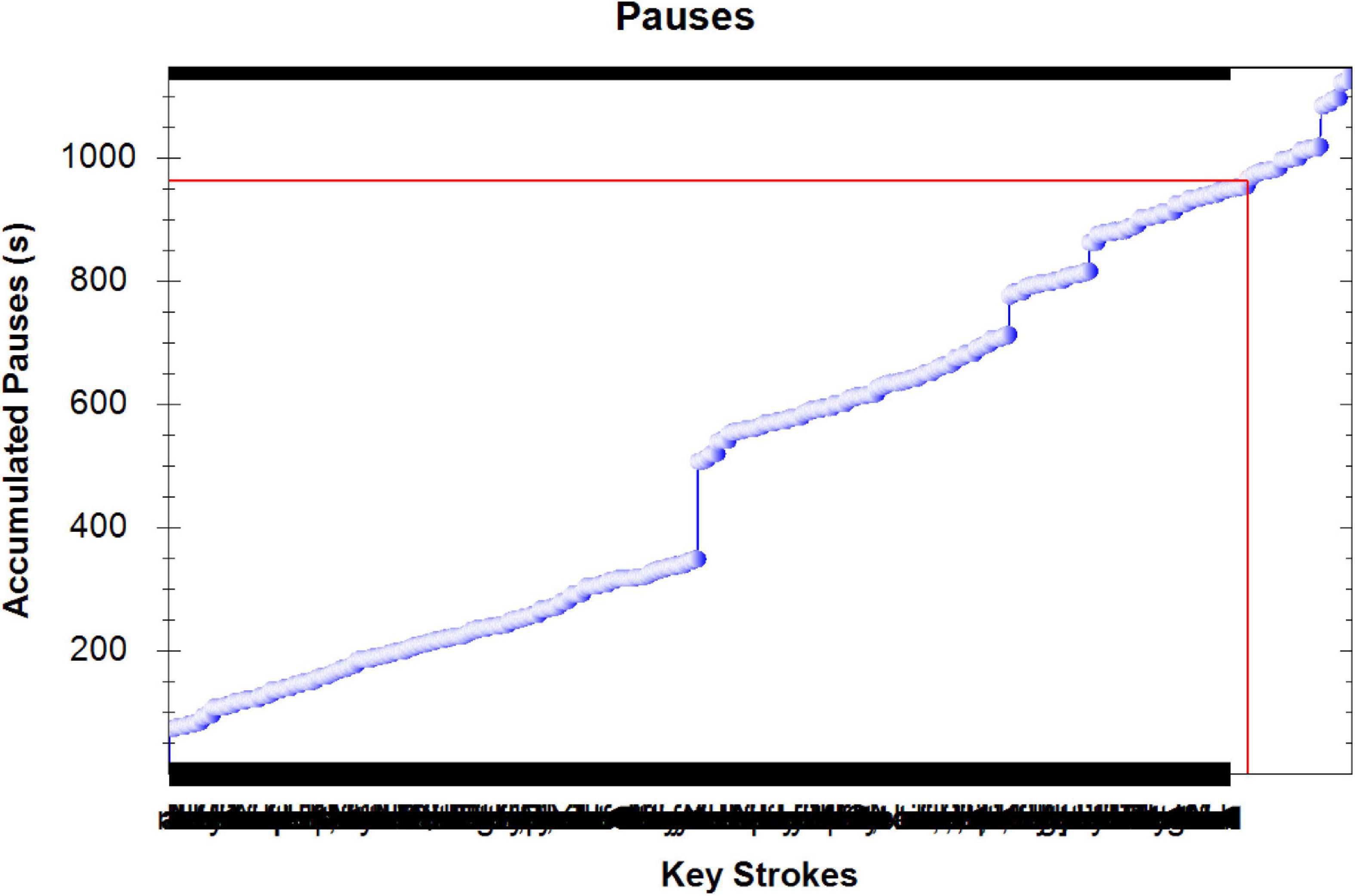

As Figure 4 shows, the translation undergoes several pauses. The translator paused either to think of the meaning of some words/expressions, or to consider the appropriateness of them. Figure 5 shows the pauses made by the translator of the text as well as keystrokes.

The statistics of the TAPs document and the screen recording show that the translator spent about 19 mins producing the target text. During the time, 1,115 user events were produced; 1,023 of which are related to text production, 64 were devoted to deletion of text, and 28 were miscellaneous events. The replay of the document shows that the translator did not compile any corpus. Neither a comparable nor a parallel corpus were used, and the translation seems literal to a great extent; some inappropriate lexical items and collocations were used.

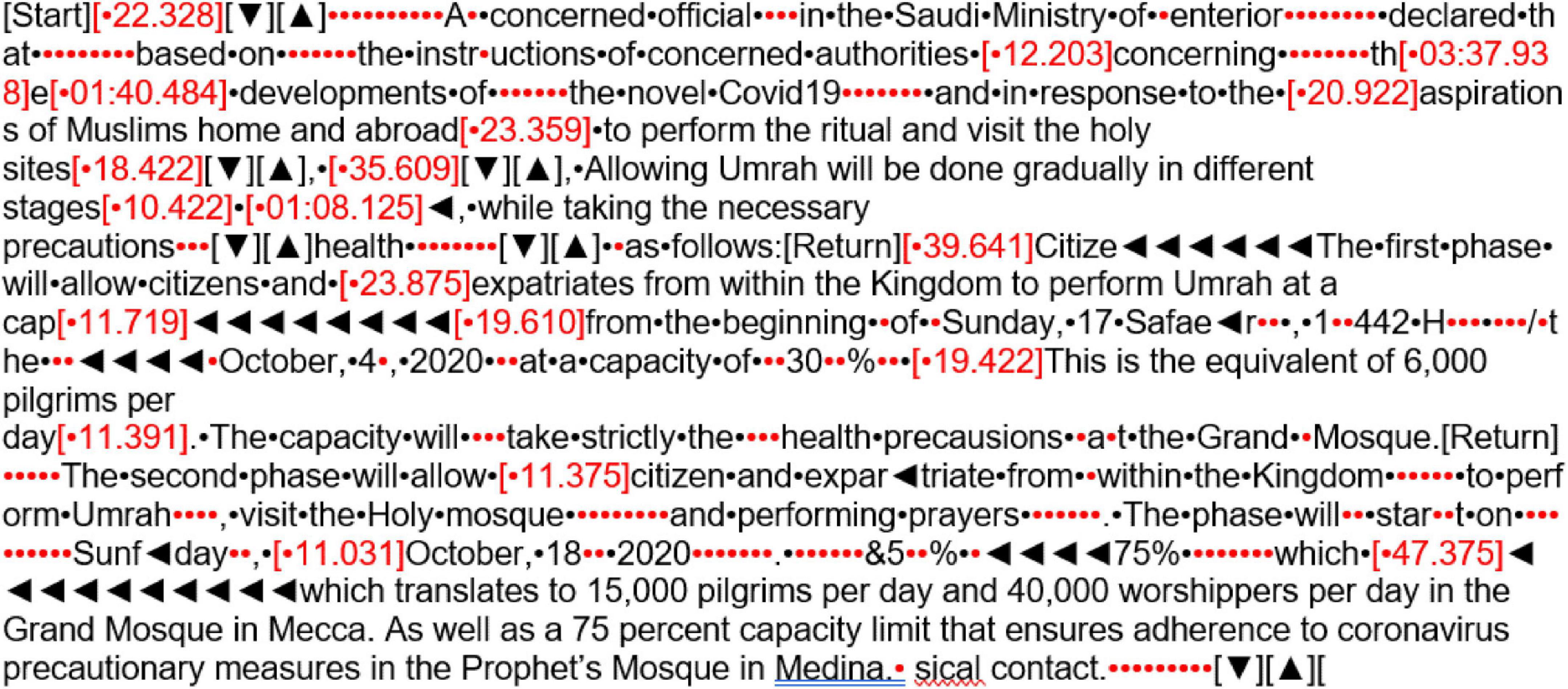

Upon completion of the section on corpus-based translation studies in the course, the trainees participated in several genuine translation projects, including the following project about the resumption of Umrah by Saudi authorities. The linear representation of the translation appears in Figure 6.

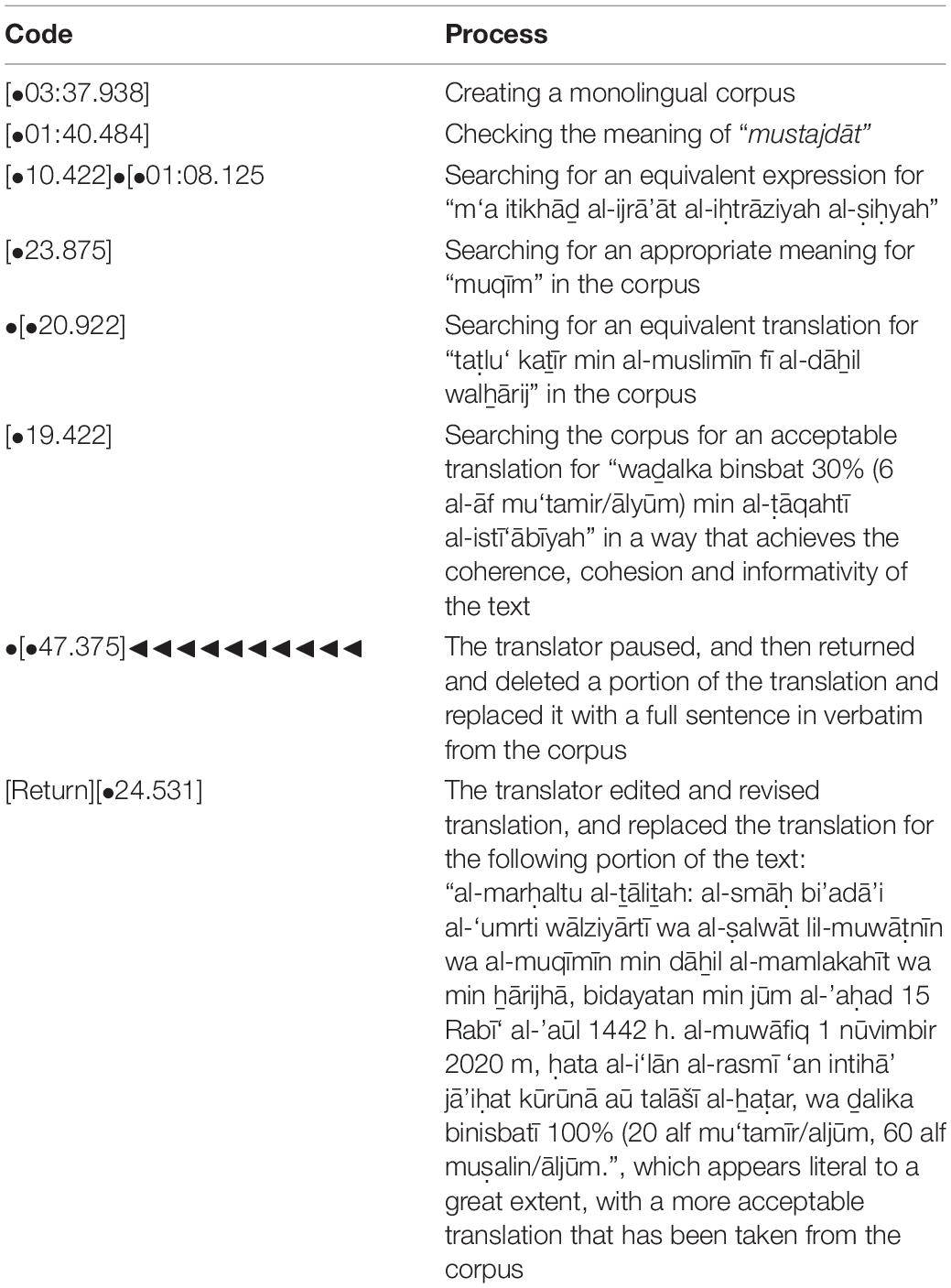

The statistics of text production in Figure 6 indicate that the trainee completed the translation in 51 mins, 10 s and 938 ms. The total user events are 3,146; 2,018 of them are text-production events, 288 are text-elimination events, and 840 are miscellaneous events. Table 3 summarizes some of those events.

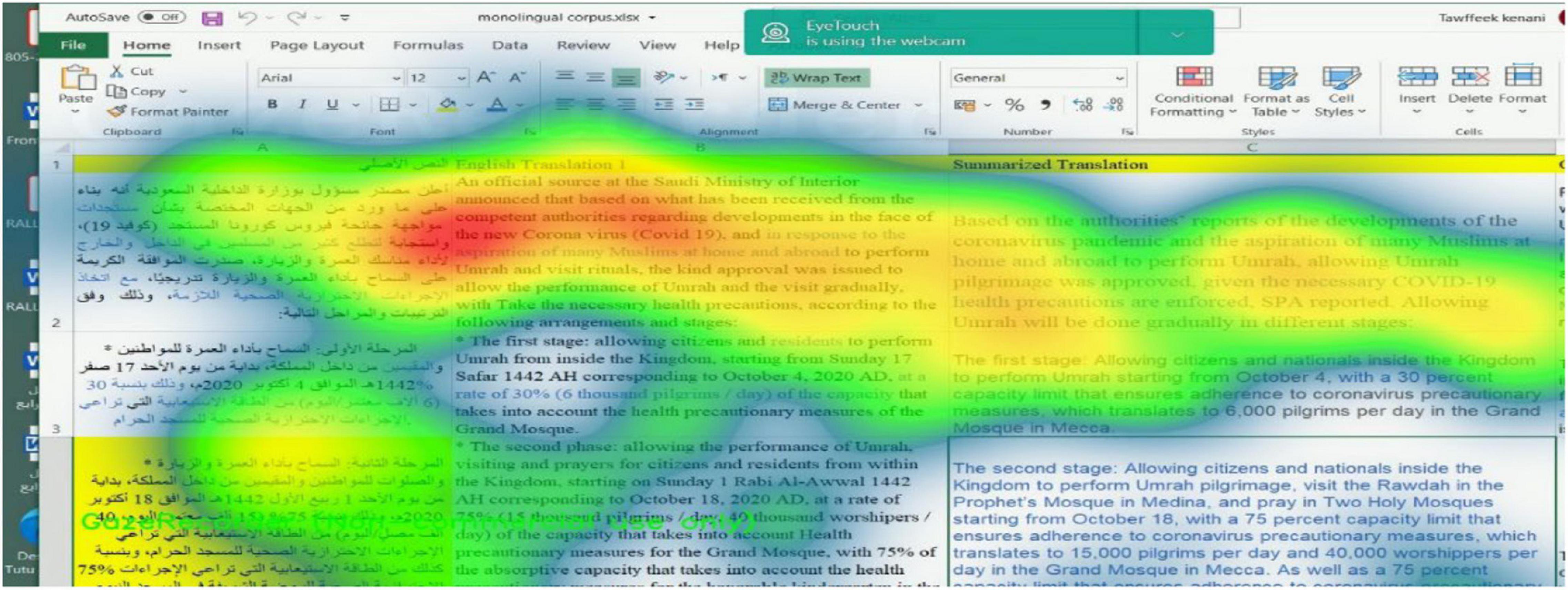

The screen and gaze recorders indicate that the translator utilized the corpus to find out the most natural equivalent terms/expressions for those of the source texts. The heat map in Figure 7 shows that the translator, before drafting the final end product, located more than one possible translations for lexical items such as “mustajdāt” and “muqīm” as well as for expressions and sentences such as “m‘a itikhāḏ al-ijrā’āt al-iḥtrāziyah al-ṣiḥyah” and “taṭlu‘ kaṯīr min al-muslimīn fī al-dāẖil walẖārij”.

The linear representation also shows that the translation sometimes seems smooth and continuous and has not been interrupted by any hesitations or pauses. These are the positions in which the translator used a previously designed corpus and retrieved translations from it.

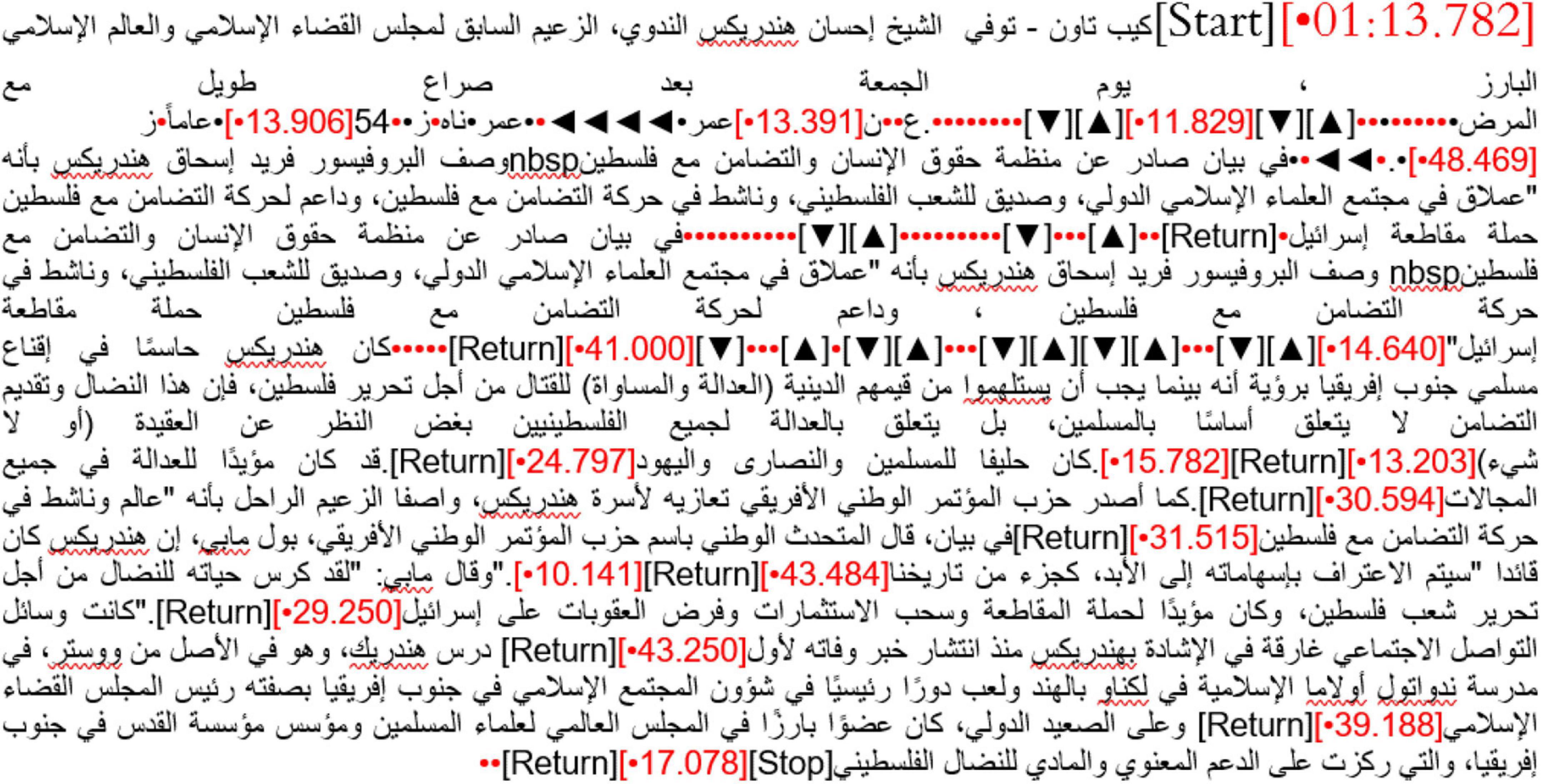

The linear representation for the translation of the third text (i.e., a biography text) in Figure 8 shows that the translator has rarely paused. The longest pause period was [•01:13.782]. When referring to the screen recording, it was found that the translator used a translation memory that included a parallel corpus in a significant portion of the text. The pause time was used to recall the translation memory. Afterward, translation proceeds smoothly.

Emerging data from the linear representation in Figure 8 and the output analysis show that the translator translated the text in about 10 mins. Almost all user events except 6 were devoted to the production, rather than the elimination of the text. That is to say, the parallel corpus used by the translator provided exact and accurate translation that saved time and effort.

Findings From the Questionnaire

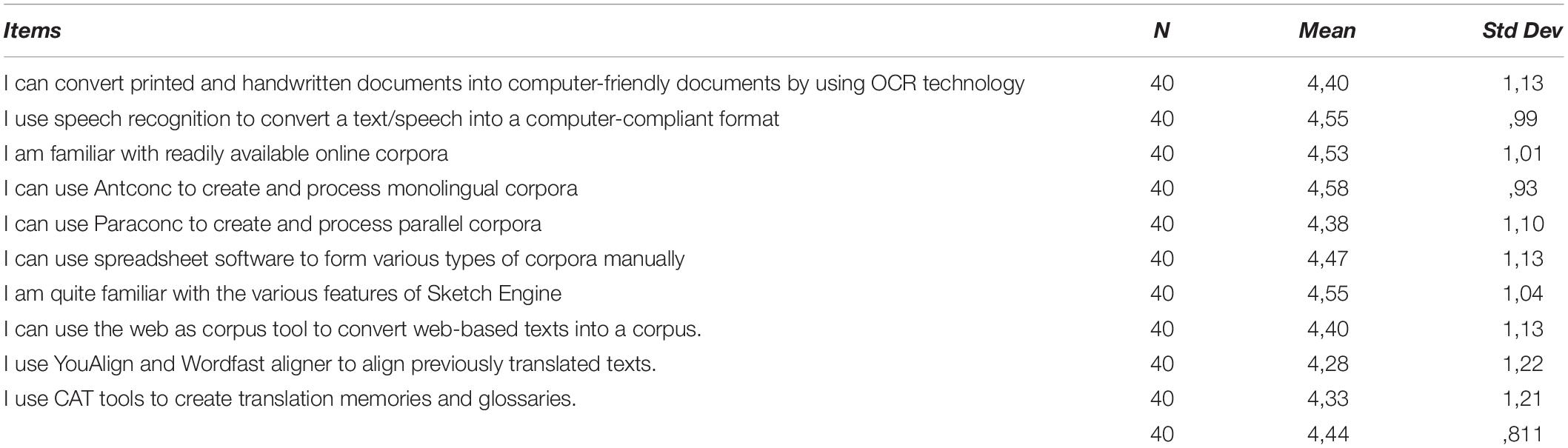

To answer the second question posed in this study; do translation trainees have positive perceptions toward corpora tools? the data collected via the questionnaire were captured and analyzed using the PSPP software. The descriptive statistics (i.e., means and standard deviations) for each item were calculated. Table 4 shows how the respondents perceive their instrumental sub-competence and to what extent they use computer tools in the creation of their corpora.

The data in Table 4 show the respondents’ perceptions about the contributions the training could add to their technological and instrumental sub-competence. The average of items ranged from 4.28 to 4.58. This demonstrates a high level of agreement on all items related to the instrumental competence of the trainees. The overall average of the items is 4.44 out of 5, indicating a high level of positive attitudes toward the program’s impact on their instrumental sub-competence.

The results in Table 4 also confirm findings obtained from the computer observation and the TAPs that translators’ competence improved tremendously. They used and created all types of corpora. They demonstrated familiarity with all the logistics of a corpus creation such as the use of Optical Character Recognition (OCR), speech recognition, and speech to text tools. Mastering such tools enables the trainees to make use of hard-copy texts and documents and convert them to files compatible with the corpus creation tools. After all, one should not expect a translation firm that accumulated a bulk of hard-copy documents to reprint them from scratch. The use of the above tools might not render a 100% accuracy rate, but the output is generally satisfactory. Results also show that the trainees are familiar with the various types of corpora available online which can increase their focus during translation. The emerging data also confirm that the trainees are able to use corpus creation tools to compile monolingual, comparable, and parallel corpora. The trainees indicated that they make use of spreadsheet software, desktop corpus tools such as Antconc, Paraconc, and Sketch Engine, as well as the web as corpus tools. Trainees also reported use of alignment software such as Wordfast auto-aligner to create parallel corpora out of translations they had previously made, saving them as translation memories for future use.

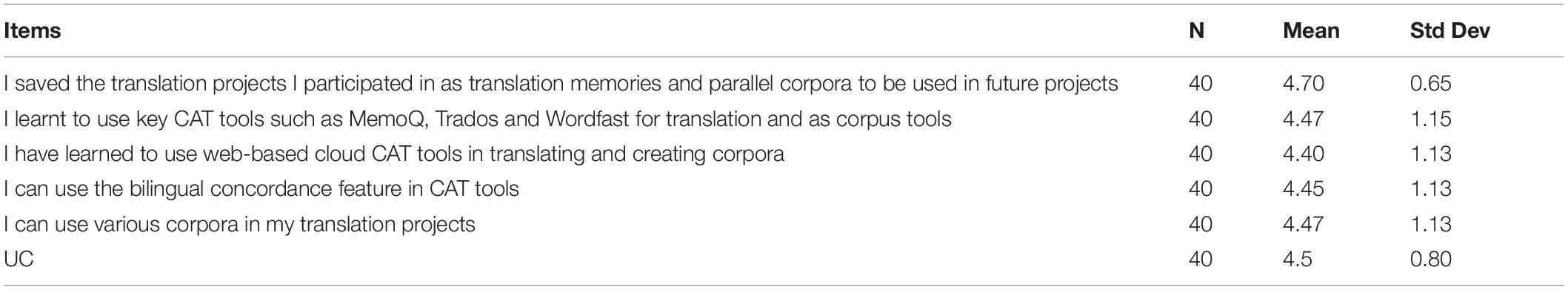

Findings from the questionnaire also confirmed these from translation process that the trainees are able to create and utilize various corpora and CAT tools in their translation tasks and projects, as Table 5 shows.

The results in Table 5 indicate that the trainees’ perceptions toward the use of corpora in their translation projects are positive. The average of items in the relevant section of the questionnaire ranged from 4.40 to 4.70. This shows a high level of agreement on all items. The overall average of the items is 4.5 out of 5. The table shows that the trainees have not only used CAT programs such as Wordfast, Trados, or MemoQ in their translation work, but they also saved the translations they finalized as translation memories for future use. The trainees also reported use of web-based translation tools such as Memsource, Wordfast Anywhere, and the like, in translation and as corpus tools. They saved their projects as translation memories, using alignment tools to create translation memories and parallel corpora from their previous translations. Trainees also used the built-in concordance tools to search for equivalent terms/expressions in the two languages or to find out a key word in context (KWIC). Trainees also indicated that they create various in-demand corpora that are related to their projects. Additionally, the trainees have also shown positive perceptions toward the approach adopted in the training, as shown in Table 6.

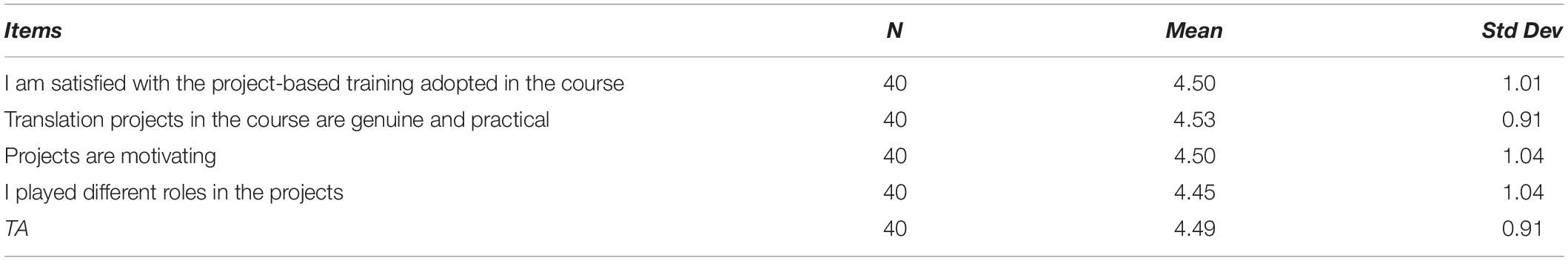

The data in Table 6 show that the trainees’ attitudes toward the project-based approach used in the course were high. The mean of items ranged from 4.45 to 4.53. This shows a high level of agreement on all items of the training approach. The total average of the items is 4.49 out of 5. The trainees indicated that the translation projects they participated in, were genuine and practical, and motivated them to work and learn. The projects gave them an opportunity to play different roles. They were requested to pre-translate, translate, proofread, edit, and revise translations.

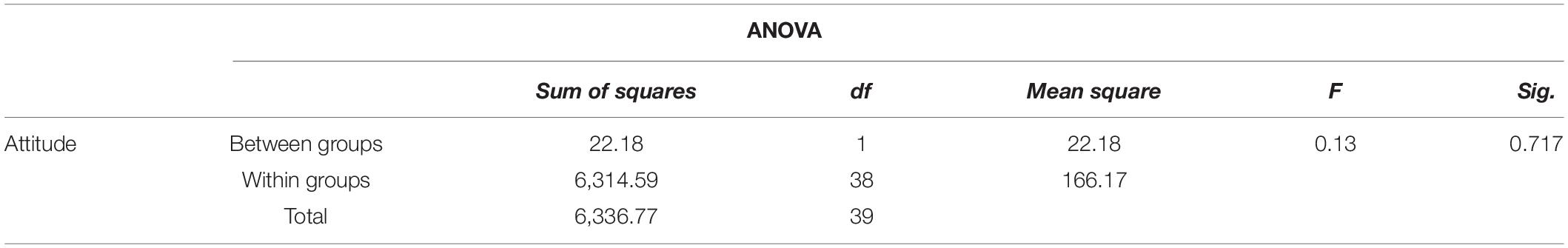

To answer the third question of the study; Is there any correlation between the perceptions of the participants and their professional rank or computer literacy? the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test (Table 7) was used. The significance level in this study was set at p < 0.05.

As the results in Table 7 show, no statistically significant correlation was found in the respondents’ attitudes toward the use of corpora tools based on their professional rank (i.e., novice, professional, expert, student, etc.) at the (0.05) level of significance. The F-value was (0.13), indicating no significant differences at α = 0.05 since the p-value > 0.05 (p = 0.717). This can be attributed to lack of training on the use of those tools in the translation programme at university.

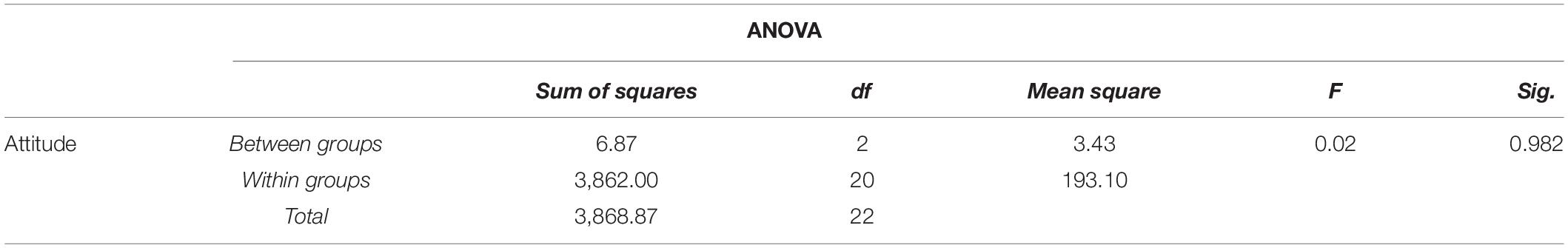

In a similar vein, the ANOVA test (Table 8) was also used to investigate whether the trainees’ attitudes toward the use of corpora and the training approach are related to their computer literacy.

The results of the ANOVA test in Table 8 indicate that there is no statistically significant correlation α = 0.05 between the respondents’ attitudes toward the use of corpora tools and their computer skills or literacy. The F-value was (0.02) and the p-value > 0.05 (p = 0.982).

Discussion

The study aimed at examining the effect of using monolingual, comparable and parallel corpora tools while translating authentic projects from Arabic into English and vice versa. The findings from computational observation showed that participants have not only used available online corpora but they have also created corpora that are fully in accord with the translation projects they are doing. The findings of this study are in line with the studies of Baker (1995), Zanettin (1998; 2001; 2014), Krüger (2012), and Alhassan et al. (2021) which emphasized the importance of corpus-driven pedagogy in the translation and language classrooms. Corpora tools like other computer-assisted translation tools have increased productivity, consistency and quality in translation (Doherty, 2016). This finding, however, is in conflict with a recent study that was conducted in the Russian-French context (Usmanova et al., 2021), which concluded that novice translators’ overreliance on some CAT tools may negatively affect the quality of their translation.

With regards to the second research question about the attitude of translation trainees toward corpora tools, findings displayed generally positive attitudes toward corpus use in translation training. This result is consistent with the findings of Yoon and Hirvela (2004); Kilimci (2017), and Poole (2020) which investigated corpus use in L2 writing, vocabulary learning and language learning and teaching in general. The findings are also in line with other studies that examined the attitudes of professional translators toward computer-aided translation tools including (Çetiner, 2018; Mahfouz, 2018; Heinisch and Iacono, 2019). However, the findings of this study contradict the results of Mohammed et al. (2020) who found that the professional translators in Yemen are averse to use CAT tools. The aversion of these professional translators to the technologization of translation may be attributed to the fact that they have not been familiarized with these tools and their benefits in the training programme or in the workplace.

With regards to the research question about the correlation between the professional rank of participants and their attitudes toward the experience of corpus use, the findings of the study indicated no statistically significant correlation between the two variables. This finding of the study contradicts the results of Heinisch and Iacono (2019) which indicated that students have more positive attitudes toward translator platforms than professional translators. In a similar vein, the findings of our study showed no correlation between the computer skills of the participants and their attitudes toward corpora tools. This finding is also in conflict with the findings of Mahfouz (2018) which revealed that users with better computer skills have more favorable attitudes toward CAT tools unlike those with more experience in translation.

As far as the training approach is concerned, the findings of this study confirm the studies of Kiraly (2012); Li (2013), Alkhatnai (2017); Apandi and Afiah (2019), and Al-Sowaidi (2021) about the rewarding benefits of a project-based approach in translator training.

Conclusion

This study examined the use of monolingual, comparable, and parallel corpora in the context of Arabic-English translation. The translation trainees who participated in the study were involved in several translation projects and the process of translation was monitored using Transalog, a translation process software, a gaze recorder software as well as a screen capturing tool. Results from the thinking aloud protocols and computer observation indicated that the translation trainees who participated in this study employed various types of corpora effectively in their translation projects. They not only used available online corpora, but they also created corpora that are directly related to their translation projects. Participants also indicated noticeable mastery over technological tools that are used in the creation of corpora.

The results of the questionnaire showed that the trainees had positive attitudes toward their technological or instrumental competence, the use of corpora in their daily workplace, as well as toward the project-based approach adopted in this study. This study recommends the integration of technology in training institutions for translators using genuine projects that more accurately reflect the challenges of the translation industry. The project-based approach has great potentials in the context of translation training as it can be employed in translation classrooms while teaching various modules that require the translation of various text types and genres as well as in the teaching of advanced modules that requires a higher level of technology integration. This study also recommends in-service training workshops for novice and professional translators that keep them updated about the fast-growing technological tools in the language and translation industry.

Despite the importance of the findings, the study is not without limitations. Although the study points out the need to enhance the instrumental competence of the translation trainees, it has just dealt with limited computer-assisted translation tools. Further studies are needed to investigate the use of other CAT tools in the translation process and the impact of these tools on the translation trainees’ performance. In addition, the small sample of the study may affect the generalizability of the findings. It is worth mentioning that a sample of 40 participants is sufficient in an empirical study about the translation process. Future research could include the investigation of the teaching and use of various CAT tools in a higher education context and their role in the enhancement of the instrumental competence of the would-be translators. The actual use of these tools in the translation process may be explored through retrospective interviews, eye-tracking and other computational tools.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abuhakema, G., Faraj, R., Feldman, A., and Fitzpatrick, E. (2008). Annotating an Arabic Learner Corpus for Error. Department of Linguistics Faculty Scholarship and Creative Works. [Preprint]. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.montclair.edu/linguistics-facpubs/10 (accessed March 15, 2021).

Adab, B. (2005). “Translating into a second language: can we, should we,” in In and out of English: For Better, for Worse, eds G. M. Anderman and M. Rogers (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 227–241.

Ahmed, F., and Nürnberger, A. (2008). “Arabic/English word translation disambiguation using parallel corpora and matching schemes,” in Proceedings of 12th EAMT Conference, Hamburg, Germany, 22-23 September 2008, (Hamburg), 6–11.

Ahmed, F., Nürnberger, A., and De Luca, E. W. (2009). “A corpus-based approach to improve Arabic/English cross-language information retrieval,” in Proceedings of Corpus Linguistics Conference (CL2009), University of Liverpool, UK, 20 - 23 July 2009, (University of Liverpool), 144–159.

Alhassan, A., Sabtan, Y., and Ismail Omar, L. (2021). Using parallel corpora in the translation classroom: moving towards a corpus-driven pedagogy for omani translation major students. Arab. World English J. (AWEJ). 12, 40–58. doi: 10.24093/awej/vol12no1.4

Alkhatnai, M. (2017). Teaching translation using project-based-learning: saudi translation students perspectives. AWEJ Transl. Literary Stud. 1, 83–94. doi: 10.24093/awejtls/vol1no4.6

Alotaibi, H. M. (2016). AEPC: designing an Arabic/English parallel corpus. Res. Corpus Linguist. 4, 1–7. doi: 10.32714/ricl.04.01

Al-Sowaidi, B. (2021). Use of project-based training in teaching business translation. Eur. J. Educ. Pedagogy 2, 11–16. doi: 10.24018/ejedu.2021.2.4.114

Apandi, D., and Afiah, S. S. (2019). The use of project based learning in translation class. Acad. J. Perspect.: Lang. Educ. Literature 7, 101–108. doi: 10.33603/perspective.v7i2.2656

Baker, M. (1993). “Corpus linguistics and translation studies: implications and applications,” in Text and Technology: In Honour of John Sinclair, eds M. Baker, G. Francis, and E. Tognini-Bonellis (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing), 233–250.

Baker, M. (1995). Corpora in translation studies: an overview and some suggestions for future research. Target. Int. J. Transl. Stud. 7, 223–243. doi: 10.1075/TARGET.7.2.03BAK

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based Learning for the 21st Century: skills for the future. Clearing House: J. Educ. Strategies Issues Ideas 83, 39–43. doi: 10.1080/00098650903505415

Bendazzoli, C., and Sandrelli, A. (2009). Corpus-based Interpreting Studies: Early Work and Future Prospects. Tradumatica 7. L’aplicació dels Corpus Linguistics a la Traducció. [Preprint]. Available online at: https://iris.unito.it/retrieve/handle/2318/137114/14543/2009_Bendazzoli-Sandrelli_TRADUMATICA.pdf (accessed March 15, 2018).

Bowker, L. (2002). Computer-aided Translation Technology: A practical Introduction. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

Brierley, C., and El-Farahaty, H. (2019). An interdisciplinary corpus-based analysis of the translation of كرامة (karāma,“dignity”) and its Collocates in Arabic-English constitutions. JoSTrans: J. Specialised Transl. 32, 21–145.

Carrové, M. S. (1999). Towards a Theory of Translation Pedagogy. Ph.D. thesis. Lleida: The University of Lleida.

Çetiner, C. (2018). Analyzing the attitudes of translation students towards CAT (Computer-aided Translation) tools. J. Lang. Linguistic Stud. 14, 153–161.

Doherty, S. (2016). Translations| the impact of translation technologies on the process and product of translation. Int. J. Commun. 10, 947–969.

Granger, S. (2003). Error-tagged learner corpora and CALL: a promising synergy. CALICO J. 20, 465–480. doi: 10.1558/cj.v20i3.465-480

Hartmann, R. R. K. (1994). “The use of parallel text corpora in the generation of translation equivalents for bilingual lexicography,” in Proceeding: Papers presented at the 6th EURALEX International Congress on Lexicography, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 30 August-3 September 1994, (Amsterdam), 291–297.

Havenga, M., and De Beer, H. (2016). Project-based learning in consumer sciences: enhancing students’ responsibility in learning. J. Consumer Sci. 44, 58–70.

Heinisch, B., and Iacono, K. (2019). Attitudes of professional translators and translation students towards order management and translator platforms. J. Specialised Transl. 32, 61–89.

Jantunen, J. (2002). Comparable corpora in translation studies: strengths and limitations. SKY J. Linguist. 15, 105–117.

Jingang, B. (2016). “Parallel corpus, translation studies and translation teaching,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Education, Management, Information and Computer Science (ICEMC 2017). Advances in Computer Science Research (ACSR), Shenyang, China, June 16-18, 2017, (Shenyang), 358–362.

Kenny, D. (1999). CAT tools in an academic environment: what are they good for? Target. Int. J. Transl. Stud. 11, 65–82. doi: 10.1075/target.11.1.04ken

Kilimci, A. (2017). ‘Learner perspectives towards corpus use in vocabulary learning. Int. J. Lang. Acad. 5, 343–359. doi: 10.18033/ijla.3765

Kiraly, D. (2012). Growing a project-based translation pedagogy: a fractal perspective. Meta: J. Traducteurs/Meta: Transl. J. 57, 82–95. doi: 10.7202/1012742ar

Krüger, R. (2012). Working with corpora in the translation classroom. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 2, 505–525. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.4.4

Laviosa, S. (1997). How Comparable can’Comparable Corpora’ be? Target Int. J. Transl. Stud. 9, 289–319. doi: 10.1075/target.9.2.05lav

Li, D. (2013). Teaching business translation: a task-based approach. Interpreter Transl. Train. 7, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/13556509.2013.10798841

Mahfouz, I. (2018). Attitudes to CAT tools: application on egyptian translation students and professionals. Arab World English J. (AWEJ) Special Issue CALL 4, 69–83. doi: 10.24093/awej/call4

McEnery, A. M., and Xiao, R. Z. (2005). “Character encoding in corpus construction,” in Developing Linguistic Corpora : A Guide to Good Practice, ed. M. Wynne (Oxford: Arts and Humanities Data Service (AHDS), 1–11.

Mohammed, O. S., Shaik, S., and Mahdi, H. S. (2020). The attitudes of professional translators and translation students towards computer-assisted translation tools in Yemen. J. Lang. Linguistic Stud. 16, 1084–1095. doi: 10.17263/jlls.759371

Munday, J. (1998). A computer-assisted approach to the analysis of translation shifts. Meta: J. Traducteurs/Meta: Transl. J. 43, 542–556. doi: 10.7202/003680ar

Otman, G. (1991). Aspects de l’informatisation des activités terminologiques et traductionelles. Terminol. Nouvelles 5, 15–20.

Poole, R. (2020). “Corpus can be Tricky”: revisiting teacher attitudes towards corpus-aided language learning and teaching. Comput. Assisted Lang. Learn. 1–22. doi: 10.1080/09588221.2020.1825095

Popescu, T. (2013). A corpus-based approach to translation error analysis. A case-study of Romanian EFL learners. Proc.-Soc. Behav. Sci. 83, 242–247. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.048

Rogers, M. (2005). “Native versus non-native speaker competence in german-english translation: a case study,” in In and Out of English: For Better, for Worse, eds G. M. Anderman and M. Rogers (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 256–274. doi: 10.21832/9781853597893-020

Rotherman, A. J., and Willingham, D. T. (2010). “21st Century Skills”: not new but a worthy challenge. Am. Educator. 34, 17–20.

Thawabteh, M. (2013). The intricacies of translation memory tools: with particular reference to Arabic-English translation. Localisation Focus: Int. J. Localisation 12, 79–90.

Thelen, M. (2005). “Translating into English as a Non-native language: the dutch connection,” in In and Out of English: For Better, for Worse, eds G. M. Anderman and M. Rogers (Clevedon: Multilingual Matters), 242–255.

Usmanova, Z. A., Zudilova, E. N., Arkatov, P. A., Vitkovskaya, N. G., and Kravets, E. V. (2021). Impact of computer-assisted translation tools by Novice translators on the quality of written translations. Laplage Revista 7, 714–721. doi: 10.24115/S2446-622020217Extra-C1154p.714-721

Xiao, R., and Hu, X. (2015). Corpus-based Studies of Translational Chinese in English-Chinese Translation. New York, NY: Springer.

Yoon, H., and Hirvela, A. (2004). ESL student attitudes toward corpus use in L2 writing. J. Second Lang. Writ. 13, 257–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jslw.2004.06.002

Zaki, M. (2020). Self-correction through Corpus-based Tasks: improving writing skills of arabic learners. Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 31, 193–210. doi: 10.1111/ijal.12312

Zanettin, F. (1998). Bilingual comparable corpora and the training of translators. Meta: J. Traducteurs/Meta: Transl. J. 43, 616–630. doi: 10.7202/004638ar

Zanettin, F. (2001). “Swimming in words: corpora, language learning and translation,” in Learning with Corpora, ed. G. Aston (Houston, TX: Athelstan), 177–197.

Keywords: translation, corpus, monolingual, parallel, comparable, trainees, project-based

Citation: Mohammed TAS (2022) The Use of Corpora in Translation Into the Second Language: A Project-Based Approach. Front. Educ. 7:849056. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.849056

Received: 05 January 2022; Accepted: 15 February 2022;

Published: 06 April 2022.

Edited by:

Anabela Carvalho Alves, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Sonia Gomez, Eindhoven University of Technology, NetherlandsMohammad Ahmad Thawabteh, Al-Quds University, Palestine

Copyright © 2022 Mohammed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed, dGF3ZmZlZWtAZ21haWwuY29t

Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed

Tawffeek A. S. Mohammed