95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Educ. , 01 March 2022

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.841395

This article is part of the Research Topic Executive Functions, Self-Regulation and External-Regulation: Relations and new evidence View all 12 articles

The goal of this study was to develop and test an intervention in order to improve academic writing and SRL skills of English learners (ELs). ELs are well-represented across university and college campuses in the United States. While most of them thrive academically and receive their undergraduate and graduate degrees, a majority of ELs experience difficulties with academic writing such as limited English proficiency levels and opportunities to practice academic writing. Therefore, there is a need to develop and examine evidence-based interventions to promote the development of academic writing skills of ELs. One promising line of research involves adding instruction in self-regulated learning (SRL) to writing courses. In this study, the SRL writing intervention was delivered as a one-credit semester-long course taught at a medium research university. A mixed-methods research design, combining single case quasi-experimental design to collect quantitative data and focus group interviews to collect qualitative data, was used with undergraduate ELs (n = 8) from Southeast Asia. The results of this study revealed that the SRL writing intervention had a small positive effect on the quality of students’ persuasive writing skills, but no effect on students’ SRL skills. Focus group interviews suggested that students appreciated learning about SRL skills, but found the SRL journal confusing and frequent. These findings suggest that both writing and SRL skills are teachable, but may require more time and adjustments to the teaching and learning methods employed in the study. Recommendations for the development of the improved intervention are also provided.

The number of international English learners (ELs) pursuing their degrees in the United States was 1,075,496 in 2020 (Project Atlas, n.d.). These students face a host of challenges while pursuing their degrees in American universities such as limited English proficiency levels, limited experience with academic writing, and cultural differences in writing expectations in the United States as compared to their home countries (Cheng et al., 2004; Phakiti and Li, 2011; Lillis, 2012; Tang, 2012; Atkinson, 2016; Hyland, 2019). In addition, students are required to write a great deal to meet course requirements. As a result, high quality academic writing is often the skill that determines students’ success. ELs, therefore, need a strong support system to succeed in writing. To create such a support system, it is important to develop and evaluate interventions that can help ELs succeed in American universities such as combining the constructs of multilingual writing (MW) and self-regulated learning (SRL).

Many researchers refer to multilingual writing as second language writing (SLW) or foreign language writing (FLW; Matsuda et al., 2013; Manchón, 2016; Silva, 2016; Hyland, 2019). For example, Hyland (2013) defines SLW as “writing performed by non-native speakers” (p. 426). Reichelt (2011), however, distinguishes FLW from SLW. In her view, “foreign language writing… is the phenomenon of writers composing in a language that is neither the writer’s native language nor the dominant language in the surrounding context” (p. 3). Other scholars recognize the diversity ELs bring to academic writing and introduce concepts of multilingual and translingual writing (Canagarajah, 2002, 2013), which is performed in more than one language. Canagarajah (2013) contrasts multilingual writing with translingual writing, which allows for the use of different varieties of a language or different languages in a written text. In this study, we refer to the construct as MW, which refers to any piece of writing produced by nonnative speakers of English in academic settings. The types of writing may include but are not limited to paragraphs, essays, papers, literature reviews, bibliographies, position papers, online posts, and even email communication with peers and instructors.

Another construct in a current study is SRL – a dynamic process during which learners set goals, monitor, and control cognitive, metacognitive, emotional, motivational, behavioral, and environmental processes in their attainment of goals (Winne, 1995; Pintrich, 2004; Greene et al., 2011; Zimmerman and Schunk, 2011). SRL has been extensively researched over the past 30 years, generating numerous definitions, models, and theories (Winne and Perry, 2000; Zimmerman, 2000; Pintrich, 2004; Zimmerman and Schunk, 2011). Irrespective of the theoretical bases, SRL generally refers to the processes of: (a) setting goals; (b) monitoring of progress; (c) adjusting strategies; and (d) revising goals as needed (Winne, 1995; Pintrich, 2004; Zimmerman and Schunk, 2011; Andrade, 2013). SRL is a mega-theory of sorts that includes multiple psychological, motivational, affective, and cognitive processes working in sync to facilitate achievement of goals (Andrade, 2013).

Research has shown that learners tend to regulate their learning, and effective SRL is related to academic achievement of students across ages and education levels (Winne, 2005; Mullen, 2011; Dent and Koenka, 2016). Since SRL has properties of a skill, it is teachable; however, it is important to provide enough scaffolding for learners to become proficient in SRL. The time it takes to become an expert user of SRL varies, depending on the types of SRL skills targeted and metacognitive monitoring performed (Winne, 2005). SRL interventions have been developed and applied across domains, including math, science, reading, writing, history, and online learning environments (Dignath and Büttner, 2008; Greene et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2019).

Writing is susceptible to self-regulation. A meta-analysis examining the effectiveness of the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD; Harris et al., 2011) intervention on the quality of writing done by adolescents indicated that it significantly contributed to improved writing quality (Graham and Perin, 2007). At least for native English speakers, SRL instruction combined with writing instruction results in improved writing skills (Graham and Perin, 2007; Harris et al., 2011). According to Harris et al. (2011), years of research with typically developing students and students with special needs show that (a) better writers tend to be more self-regulated; (b) novice writers become more self-regulated with age and practice; (c) level of self-regulation is related to writers’ performance; and (d) struggling writers can become successful through targeted writing and SRL instruction with multiple opportunities to practice new skills. SRL is teachable and, when embedded into writing interventions, helps struggling students become better writers.

Although research has shown that SRL is associated with improved performance by native speakers of English across disciplines and age-groups (Graham, 2006; De Corte et al., 2011; Kitsantas and Kavussanu, 2011; Tonks and Taboada, 2011), research on the usefulness of SRL instruction in developing scholarly writing skills in college students, especially ELs, is scarce and under-developed. A small number of scholars have recognized the importance of SRL in developing writing skills of ELs (Oxford, 2011; Andrade and Evans, 2013; Teng and Zhang, 2016, 2018, 2020; Fathi and Feizollahi, 2020; Altas and Mede, 2021; Han et al., 2021). Research shows that the SRL processes that occur during writing by ELs are similar to those of native speakers. For example, a validation of the Writing Strategies for Self-Regulated Learning Questionnaire (WSSRLQ) with Chinese undergraduate students (n = 780) revealed that the strategies of deep processing, emotional control, motivational self-talk, and feedback use were strong predictors of students’ writing proficiency (Teng and Zhang, 2016). Farsani et al. (2014) reported a statistically significant, yet small and negative correlation between SRL and writing performance (r = −0.294, p = 0.043) in their sample of Iranian students (n = 48), using the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ). Although the authors acknowledged the importance of embedding SRL instruction in writing courses for ELs, their anomalous findings had indicated that the relationship between SRL and writing performance of ELs warrants additional rigorous research.

A handful of scholars conducted the quasi-experimental intervention studies measuring undergraduate students’ gains in multilingual writing and SRL skills (Fathi and Feizollahi, 2020; Teng and Zhang, 2020; Altas and Mede, 2021; Chen et al., 2021). For instance, Chen et al. (2021) conducted a quasi-experimental study with undergraduate students (n = 102), targeting the revision instruction of the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD; Harris et al., 2011) in control, SRSD + genre-specific criteria, and SRSD + generic criteria conditions. The results showed that both SRSD conditions were more effective in improving students’ text quality and revisions than the control group. However, Chen et al. (2021) did not measure students’ SRL skills. In contrast, Teng and Zhang (2020) examined the effects of the SRL strategies-based writing intervention on Chinese undergraduate students (n = 80) multilingual writing proficiency, reported use of SRL strategies, and academic self-efficacy. The results indicated students’ improvements in the use of various SRL strategies and increased levels of linguistic self-efficacy (ES = 0.39) and performance self-efficacy (ES = 0.21) as well as in the improvement of writing performance (d = 2.11).

Some experts in MW recognize the importance of developing self-regulated writing curricula. For example, Andrade and Evans (2013) laid out a comprehensive writing program, embedding direct instruction of SRL skills with opportunities for learners to engage in SRL in pre-, during, and post-writing tasks. Similarly, Oxford (2011) suggested directly teaching SRL skills, emphasizing the importance of learning strategies for each of the English skills: speaking, listening, reading, writing, grammar, and vocabulary. To date, none of these programs have been empirically tested.

This review of the small body of literature combining SRL and MW shows the mixture of correlational studies that examined relations between SRL and writing performance/quality (Farsani et al., 2014; Teng and Zhang, 2016, 2018; Han et al., 2021), four intervention studies reporting on students’ writing quality and some SRL skills (Fathi and Feizollahi, 2020; Teng and Zhang, 2020; Altas and Mede, 2021; Chen et al., 2021), or proposed untested SRL writing programs/instructional practices (Oxford, 2011; Andrade and Evans, 2013). While these lines of research contribute to our understanding of how SRL associates with MW and four intervention studies provide initial evidence of improvement in MW and SRL skills, they do not provide conclusive results on how SRL writing instructional methods work in authentic settings. Therefore, there is a need for continuing empirical research on the effects of embedding SRL training in multilingual writing instruction and developing targeted interventions for ELs.

This study contributes to the growing body of the intervention research on combining SRL and writing instruction. Unlike the intervention studies discussed above, the use of the single case quasi-experimental design in this study allowed for identification of MW and SRL gains, if any, for each participant and across all participants combined. In addition, this study promoted the intervention development (Hayes et al., 2013) since the detailed analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data indicated the potential areas for improvements. All of these aspects are discussed in details in the remainder of this article.

The Model of Self- and Socially-Regulated Multilingual Writing (Akhmedjanova, 2020; Figure 1) was used to describe the interactions between SRL and writing in authentic classroom settings. The model is organized around three broad areas: processes internal to a student (C–I, M, and N), processes external to a student (A, B, and J–N), and culture (O). Each area has its own set of processes contributing to the development of writing and self-/socially-regulatory skills. Thus, processes external to the student include instructional techniques (A, B) and formative assessment, occurring in classrooms (J–N). The processes internal to a student focus on activation of student’s background knowledge and motivational beliefs, which lead to the choice of strategies and techniques to do the writing task (C–I, M, and N). Finally, culture (O) situates both types of processes within a socio-cultural context or “writing communities” (Graham, 2018, p. 258), which function under certain social, political, economic, environmental, and cultural affordances. As a result, writing becomes a cultural activity of jointly constructing meanings to communicate them within various genres (Rose and Martin, 2012; Atkinson, 2016).

Typically, writing instruction starts with how to write in a specific genre (A). As part of the instruction (A), the teacher sets the writing task (B) and articulates the criteria for it. The writing task activates students’ prior knowledge, strategy knowledge, and motivational beliefs (C). Task interpretation (D) acknowledges that students interpret tasks in idiosyncratic ways, and their interpretations influence their personal goals and task management (F), as well as their self-efficacy and motivation (Butler and Winne, 1995). Based on their task interpretation, students set mastery or performance goals (E) in relation to their writing tasks. Task management (F) includes task specific strategies as well as strategies for managing students’ time, environment, and motivation. In the case of writing, task management (F) involves the selection of various writing strategies (G): planning, translating ideas into a written text, reviewing and generating feedback, and revising an essay, which correspond with the elements of the cognitive model of writing (Elbow, 1981; Flower and Hayes, 1981; Hayes, 1996). This phase helps students to apply knowledge of a new writing genre and writing strategies that can be used within this genre (Rose and Martin, 2012). As students write, they monitor their progress (H) by self-assessing their work on a task and using metacognitive strategies. They also adjust their motivational beliefs, depending on how well they are doing. The progress monitoring phase informs the task management phase (F) because it allows students to identify which of the writing strategies (G) work well and which do not. Based on this information, students make adjustments to the way they approach the task by choosing new strategies or modifying the old ones. This leads to internal learning outcomes (I). In the case of writing a persuasive essay, students internalize the elements of genre and other writing conventions to write high quality persuasive texts. As a result of actions in phases A–I, M (Figure 1), students generate externally observable outcomes, such as persuasive essays (J). At this stage, teachers can enact social-regulation by creating opportunities for students to provide and receive peer feedback, as well as feedback from teachers and technology (K). In this study, students received feedback on their persuasive essays from their peers and the teacher. Feedback allows students to make adjustments to their finished products before they are summatively assessed (L).

Reflection (N) occurs throughout the whole process of writing; however, it is placed toward the final stages of the writing process because its primary purpose is to inform students and teachers about what worked well and what did not. In the case of writing, self-regulated students reflect on the writing strategies (G) that were helpful or not helpful for them. This reflection can facilitate students’ improved knowledge of the domain and strategies as well as their motivational beliefs (C). In addition, reflection can facilitate adjustment to instruction for teachers (A). For example, reflection can lead teachers to see what aspects of persuasive writing to reteach. Finally, the processes described above occur within multilingual classrooms that bring together teachers and students from various cultural backgrounds to form writing communities (Graham, 2018). All participants in such writing communities bring their own cultural views and perceptions on how writing should be practiced. Therefore, both the processes internal and external to a student operate within a complex culture (O).

All of the elements in Figure 1 are grounded in models of writing. For example, the processes external to a student (A, B, and J–N) mirror sociocultural theory since they occur in an environment that includes a task, a learner, peers, a teacher, and interactions among these agents (Prior, 2006; Rose and Martin, 2012; Cumming, 2016). The processes internal to a student (C–I, M, and N) combine the elements of genre since students develop the knowledge of writing genres and the cognitive model of writing because students use cognitive processes of planning, transcribing, and revising while writing (Elbow, 1981; Flower and Hayes, 1981; Hayes, 1996; Rose and Martin, 2012; Hyland, 2019). Culture (O) is represented in the Writers within Communities model of writing (Graham, 2018). In addition, each aspect of this model enjoys support from the research literature; however, there is very little research on how well these processes work in the population of English learners (ELs). Therefore, the current study addresses the gap in the research literature by targeting the population of ELs and applying quasi-experimental design to identify the effects of the SRL writing intervention on two constructs: writing and SRL skills.

To address this research gap, we have adapted the Self-Regulated Strategy Approach to Writing (SSAW; MacArthur and Philippakos, 2012). This curriculum focuses on self-regulated strategy instruction in developmental writing courses. It covers a variety of genres including narrative, classification, compare/contrast, cause and effect, and persuasive writing. In addition, the SSAW emphasizes the use of planning, drafting, and revising writing strategies along with SRL strategies (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2012). A quasi-experimental study of the effectiveness of the curriculum for community college students (n = 276) indicated improved writing quality [Glass Δ = 1.22, F(1,7.3) = 40.0, p < 0.001] and increased length of essays [Glass Δ = 0.71, F(1, 7.6) = 75.2, p = 0.027; MacArthur et al., 2015). The findings also showed increases in students’ self-efficacy for writing, [Cohen’s d = 0.27, = 0.03, F(1, 249) = 7.58, p = 0.006] and adoption of mastery goals [Cohen’s d = 0.29, = 0.027, F(1, 249) = 7.01, p = 0.009]. Unfortunately, only 10% of the sample in MacArthur et al. (2015) study were ELs. The results for ELs were not reported because they were not statistically significant.

The intervention developed by MacArthur and Philippakos (2012, 2013) and MacArthur et al. (2015) produced gains in both writing quality and SRL skills. However, it is not clear how well this intervention can work with ELs (MacArthur et al., 2015). Therefore, we adapted and tested the SSAW intervention with a small group of undergraduate ELs. The adaptation of the SSAW intervention was treated as intervention development (Hayes et al., 2013) because it was implemented with the population of ELs. As a result, the application of the SSAW intervention led to identification of future changes to the intervention in order to meet the needs of ELs. For the purpose of this study, we chose instruction of only persuasive essays since it is one of the genres that is assigned the most in higher education (Gardner and Nesi, 2013).

The rationale for targeting the population of the undergraduate ELs is that they represent the largest proportion in comparison with the graduate ELs (Project Atlas, n.d.). Undergraduate ELs are in a greater need so that they do not fall behind early in their academic careers. The aim of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of the SRL writing intervention in improving SRL and writing performance of undergraduate ELs in the context of an authentic multilingual classroom by addressing the following research questions:

(1) Does the SRL writing intervention improve the quality of persuasive essays done by ELs?

(2) Does the SRL writing intervention improve the self-reported SRL skills of ELs?

(3) What are students’ perceptions of the SRL component of the SRL writing intervention?

A mixed-methods research design, combining both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, was implemented in this study (Casanave, 2016; Manchón, 2016; Onghena et al., 2019). The single-case quasi-experimental design (SCED) was used to collect quantitative data. The SCED has been extensively used in various fields such as medicine, neurosciences, physical therapy and special education (Kratochwill et al., 2014; Moeyaert et al., 2014), but it is new to the field of multilingual writing. SCEDs share three main characteristics: (1) the focus is on one unit: a person or case, (2) one or more dependent variables are measured repeatedly across time, and (3) one or more independent variables are actively manipulated (Kratochwill et al., 2010; Horner and Odom, 2014).

A typical single-case design study involves an active manipulation of an independent variable to identify how this manipulation affects a dependent variable (Kratochwill et al., 2010; Horner and Odom, 2014). The dependent variable is measured repeatedly and systematically in successive phases before, during, and/or after the intervention. This design can be used to examine causal relationship between the independent variable, represented as intervention, and changes in outcome variables (Kratochwill et al., 2010; Smith, 2012). The relationship between dependent and independent variables is causal when a change in outcome data between the intervention and baseline conditions can be solely attributed to the manipulation of the intervention and not to outside experimental factors (i.e., confounders; Kratochwill et al., 2010). Hence, an intervention effect should be replicated across multiple participants and, ideally, the intervention effect should be demonstrated at different points in time. A unique strength of using an SCED is that participants serve as their own control as they are observed during a control condition preceding an intervention condition (i.e., no matched comparison group is needed). In addition, because of the repeated observations, participant-specific changes in data across time during both the baseline and intervention conditions can be evaluated, in addition to estimating an individual-specific intervention effect (Molenaar and Campbell, 2009; Velicer and Molenaar, 2012). For these reasons, an SCED was implemented in the current study.

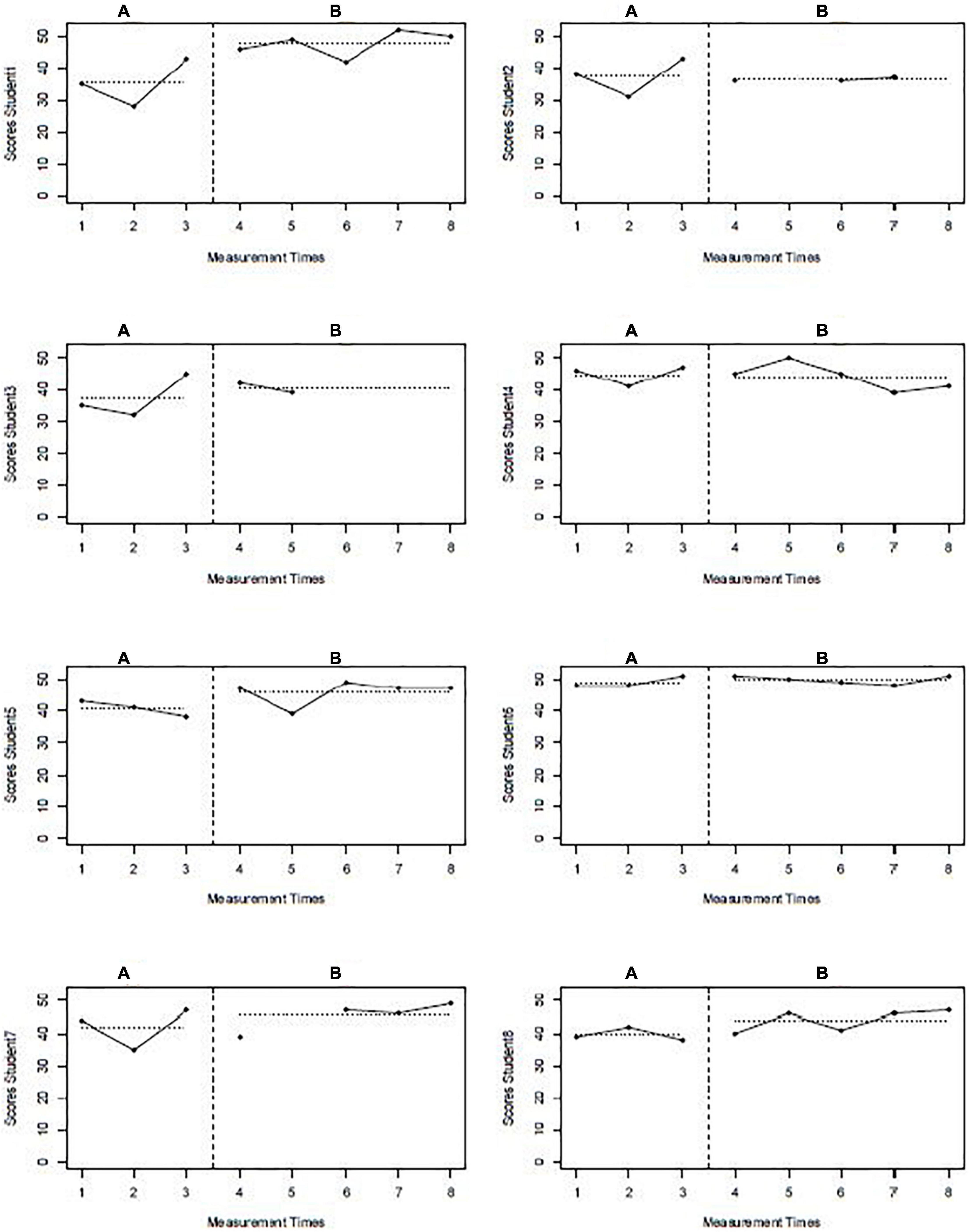

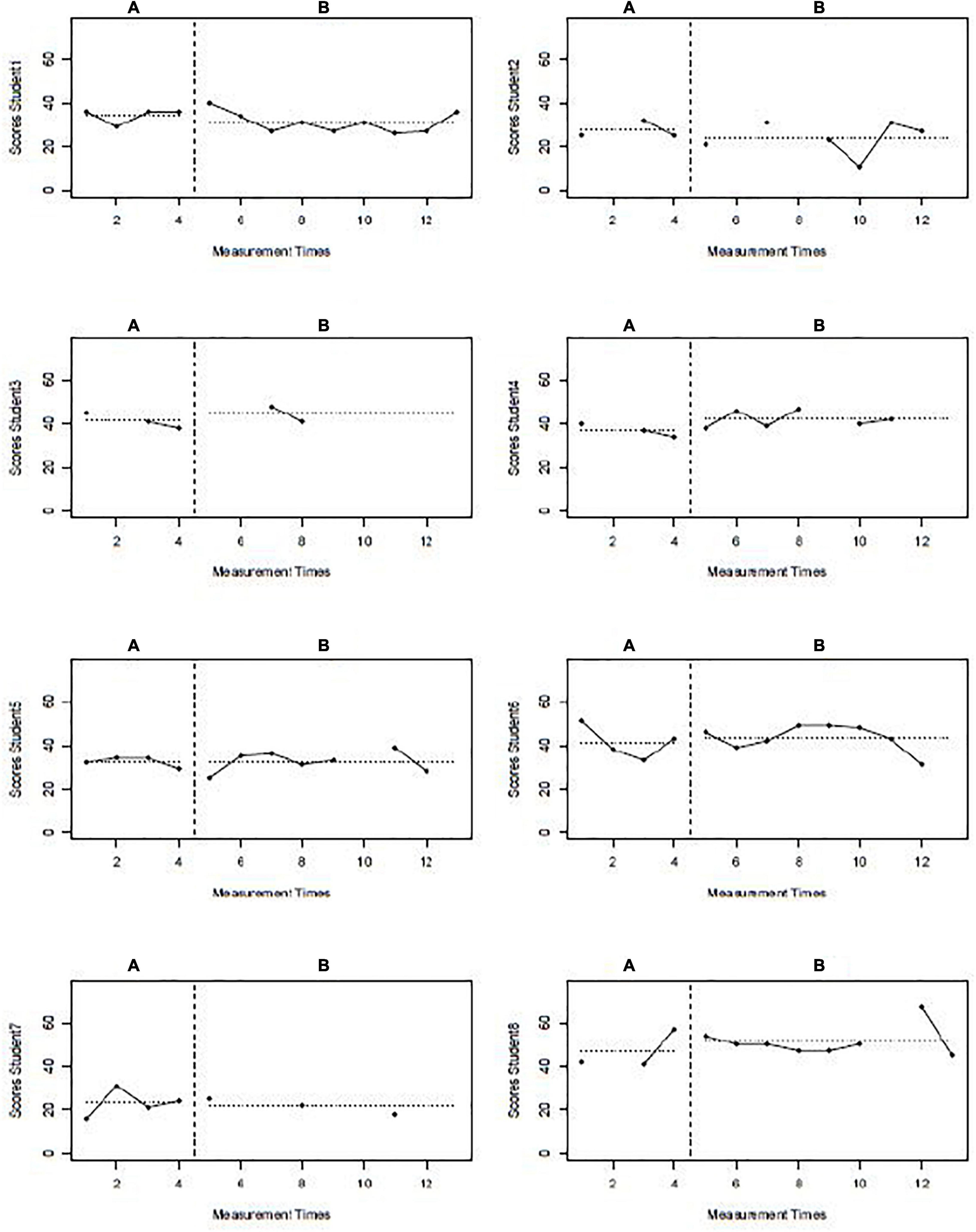

A replicated AB phase design was used (Figures 2, 3), which has the potential to demonstrate intervention effectiveness across individuals. To increase the internal validity of the replicated AB phase design, it is recommended to start the intervention at different time points across the participants (i.e., participants have different baseline lengths, What Works Clearinghouse, 2020). In that way, it can be concluded that the intervention is effective, regardless of the starting time. Changes in data patterns should only be observed for participants starting the intervention, whereas participants still in the baseline should not experience any changes. A staggered starting point of the intervention was not possible in this study given the nature of the intervention and the university setting (predetermined class sessions, and start/end of the semester). However, we increased the internal and external validity of our replicated AB phased design by including a large set of participants and measurements within participants. As suggested by the What Works Clearinghouse (i.e., WWC, Kratochwill et al., 2010; What Works Clearinghouse, 2020) design standards, the minimum number of observations should be three per phase across at least three participants to meet the standards with reservations. In current study, we exceeded these minimum criteria by including eight participants and a total of eight observations. Particularly, our SCED includes three measurements of writing skills in the baseline phase, and five measurements in the intervention phase; eight in total. We collected four measurements of SRL skills in the baseline phase, and at least nine in the intervention phase; thirteen in total. The first author manipulated the independent variable – the SRL writing intervention; all outcome variables were measured repeatedly over time; and at least 20% of essay and SRL journal data were double-scored to establish the evidence of reliability and validity. We can conclude that this study meets the What Works Clearinghouse (2020) requirements with reservations. Finally, qualitative data was collected through two focus group interviews. Those interviews were designed to collect detailed information about students’ perceptions of the SRL components of the intervention. This has the potential to explain why the intervention was effective or not effective.

Figure 2. Baseline (A) and intervention (B) phases for essay total score for each participant (n = 8).

Figure 3. Baseline (A) and intervention (B) phases for SRL total score for each participant (n = 8).

The participants were international ELs, who were in the first or second semesters of their undergraduate programs. The sample (n = 8) included students in their early twenties, predominantly from Korea (87.5%); half of the sample were female (n = 4; see Table 1).

All participants (n = 8) were enrolled in a 1-credit tutoring course offered by the School of Education in a medium public research university. The course was part of the larger study focusing on the written and spoken discourse of ELs. However, the primary goal of the course was to help ELs improve their academic discourse skills: Speaking, listening, reading, and writing in order to succeed in their undergraduate studies. The section of the course taught by the first author focused on helping ELs develop their writing and SRL skills. Due to low enrollment, the course was taught during two semesters: In the fall semester with five students, and in spring with three. To control for the outside confounding variables, the course was taught by the same instructor (first author), on the same days and times (Wednesdays, 4:15–5:35 p.m.), and using the same curriculum and teaching methods. Since the course was part of the larger study described above, it had to include assignments such as prompted discussions of the moral dilemmas, which otherwise would not have been included in the SRL writing intervention. The study was granted the IRB approval to collect data, and all participants signed the consent forms at the beginning of the intervention.

Three types of instruments were used to collect outcome data: essays, SRL journals, and two focus group interviews.

Students wrote eight persuasive essays during the semester on the prompts provided in the SSAW curriculum (Supplementary Appendix A).1 Three of the essays were written during the baseline phase and were used to assess the quality of students’ writing before the intervention. Five of the essays were generated after students had received instruction on how to write persuasive essays and self-regulate their learning. Since some of the students did not submit all of the essays, the final number of essays was 58.

The essays (n = 58) were scored by two independent raters, using the rubric that included such criteria as development, focus/organization, language, and conventions (Supplementary Appendix B). The raters were experienced writing instructors who taught at local community and liberal arts colleges. The first author trained the raters using benchmark essays (n = 2). Raters’ percent agreement was 86%. After the training, raters scored four essays individually, resulting in 56% percent exact agreement, disagreeing with each other only by one point across the criteria. Raters and the first author discussed discrepancies and scored one more essay to establish higher agreement in scores. After the second day of training, raters scored five essays and reached 77% percent agreement, which was acceptable to let them score individually (Stemler, 2004). While it is recommended to double-score around 20% of the data, raters double scored 43% of the essays (n = 25) to increase their agreement. The first author served as a third rater to resolve discrepancies in the scores. As a result, the exact percent agreement was moderate (63%), the adjacent percent agreement was high (95%), and Cohen’s kappa was weak (κ = 0.315; Stemler, 2004). A possible explanation of low and moderate inter-rater reliability is that the raters were not experienced in scoring essays of multilingual writers.

In order to capture the development of SRL skills in students during the semester, a self-report measure was used: SRL journals (Supplementary Appendix C). One of the goals of this study was the development of SRL skills. Therefore, the participants were encouraged to set goals, manage their tasks, monitor their progress, and reflect on their end products in the SRL journals. Each participant was expected to fill out 13 journals throughout the semester. Four of the journals were assigned during the baseline phase, and nine during the intervention phase. Due to some students skipping some of the classes, the total number of SRL journals was 77.

Similar to the quality coding of essay data, two different independent raters coded the SRL journal data (n = 77). The coding protocol included the categories within each of the four SRL constructs of goal-setting, task management, progress monitoring, and reflection, which were coded for specificity, relevance to the writing task or SRL, and alignment with the goals (Supplementary Appendix D). Two independent raters, both doctoral students in educational psychology and methodology with expertise in SRL and classroom assessment, scored the SRL journal data.

The raters received an intensive 2-day training, resulting in 86% agreement. The raters double-scored 29% of the journals (n = 23) in an attempt to increase their agreement, with exact percent agreement of 78%, adjacent percent agreement of 95%, and Cohen’s kappa value of κ = 0.617, which are considered to be good reliability estimates (Stemler, 2004). The first author served as a third rater to resolve discrepancies in the scores.

Focus group interviews were conducted with the participants to inquire about their perceptions of the SRL component of the writing intervention at the end of each semester. A trained interviewer, a doctoral student in educational psychology and methodology, conducted two focus group interviews that included six out of eight participants: The focus group in the fall included four students, and the one in spring two students. During the focus group interviews, the students were asked to reflect on their experiences with the SRL components of goal-setting, task management, progress monitoring, and reflection while working on their persuasive essays. In addition, students shared their thoughts about their experiences with the SRL journals (Supplementary Appendix E).

As part of the study, students wrote three essays and filled out four SRL journals in the baseline phase before the start of the intervention. These measurements served as students’ baseline skills in writing and SRL. Supplementary Appendix F shows the timeline of the intervention and data collection.

Most students wrote five persuasive essays during the course. Those essays served as five measures of writing quality during the intervention phase of this study. Unit 3, focusing on persuasive writing, of the SSAW (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2012) curriculum was used for this study. Unit 3 included ten lessons during which students learned how to write persuasive essays and self-regulate their writing behaviors (See Supplementary Appendix G for the syllabus). The first five lessons of the intervention focused on teaching students how to write a persuasive essay using all the elements of the genre – introduction, reasons, and conclusions. It also included a session when the first author modeled the process of writing by setting goals, brainstorming ideas for and against a controversial issue, organizing them in a graphic organizer, and drafting the whole essay. The remaining three sessions were spent on collaborative and guided practice. Students worked on their individual essays, peer review, and editing, applying knowledge and skills they acquired during the intervention. The second half of the intervention (five sessions) focused on the development of the opposing position in a persuasive essay. The first two sessions were spent on introducing a concept of opposing positions and writing opposing position paragraphs. During the remaining three sessions students wrote an essay with an opposing position, peer reviewed, and edited it.

During the intervention, students wrote four essays. Two essays were written during the first five lessons, and two during the last five lessons. An additional essay was assigned as a final exam and served as a maintenance data point 2 weeks after the intervention had finished. In total, each student was expected to write eight essays during the study to the prompts suggested in Unit 3 of the SSAW curriculum (Supplementary Appendix A; MacArthur and Philippakos, 2012).

In terms of the SRL, students filled out the remaining nine journals after the first author taught them about SRL skills. After the SRL instruction, various writing and learning strategies were discussed during each class. As a result, journals documented thirteen measures of goal setting, task management, progress monitoring, and reflection both in baseline and intervention phases.

The writing and SRL data from the journals were quantitatively analyzed using regression-based statistics. The focus group interview data were analyzed qualitatively.

The regression-based analysis was performed to estimate the overall effect of the intervention for the whole group as well as individual effects for each participant.

First, a single-level regression analysis was run to estimate the effect of the intervention on the outcomes of each participant separately. Using the simple linear regression equation presented in Eq. 1, a change in outcome level between the baseline and intervention phase can be estimated.

In Eq. 1, the outcome variable Yt is regressed on a dummy-coded variable (i.e., D). The dummy variable, D, indicates whether Yt belongs to the intervention (D = 1) or baseline phase (D = 0). Therefore, β0 refers to the outcome level during the baseline phase, and β1 indicates the change in level, representing the intervention (Rindskopf and Ferron, 2014).

Second, the single-level regression analysis is expanded to a two-level hierarchical linear modeling analysis (HLM). HLM was used to identify the average treatment effect across the participants, variance of the effect across participants, and possible factors that relate to the average treatment effect.

A two-level hierarchical linear model was fitted, assuming a stable level during the baseline phase and a change in level during the intervention phase. The mathematical model is a straightforward extension of the single-level regression model introduced in Eq. 1:

Yij is the outcome score for observation i, nested within participant j and is regressed on a dummy coded variable, Dij. Dij equals 0 when observation i within case j belongs to the baseline phase, 1 to the intervention phase. Therefore, β0j indicates the baseline level for participant j, and β1j indicates the change in level (i.e., intervention effect). The within-case variance is assumed to be normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ2e. A first order autoregressive residual variance is assumed. Because it is unlikely that the baseline level and the intervention effect will be the same for all participants, a second level was added to the model.

Level 2:

θ00 is the overall average level in the baseline phase across all participants, and u0j is the deviation of participant j from the overall average baseline level (θ00). u0j is assumed to be multivariate normally distributed [with mean equaling zero and the between-case variance in baseline level ()]. θ10 is the overall average treatment effect; it is the change in outcome level between the intervention and baseline. u1j represents the deviation of participant j from this overall average immediate intervention effect [and u1j is multivariate normally distributed with mean equaling zero and between-case variance in intervention effect (σu12)].

The two-level HLM generated effect size estimates across all and per individual participants (Moeyaert et al., 2014). The data were analyzed using the nlme (Pinheiro et al., 2019) and lme4 (Bates et al., 2019) R packages.

The analysis of the interview data included several iterations of reading (Creswell, 2013; Maxwell, 2013). The first author transcribed the interview data, using the Rev converter (Rev, n.d.), and checked the transcripts for accuracy. Ten months after the interviews, the transcriptions were emailed to students for member-checking (Anderson, 2017). Only one student responded, stating that the transcription reflected the content of the focus group interview. The thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Lester et al., 2020) was implemented to analyze data. Two raters, the focus group interviewer and the first author, coded both interviews together to identify students’ perceptions regarding the SRL component of the intervention. The coding procedures included: (1) Developing a-priori codes; (2) identifying meaningful units; (3) coding and refining the codes; (3) narrowing down the codes; and (4) making interpretations and looking for meanings. The themes, codes, and example quotes are provided in Supplementary Appendix H.

After coding data from both focus group interviews, the first author went through all of the codes, identified the duplicate codes and condensed them. It took three rounds of reading, identifying similarities and differences, and deciding which codes belonged in what categories.

The results are organized around the research questions, which examine the effects of the SRL writing intervention on: (1) the quality of students’ persuasive essays and (2) students’ SRL skills, and (3) the students’ perceptions of the SRL instruction in the writing course.

The two-level analysis was conducted to test the effect of the SRL writing intervention on the quality of students’ persuasive essays for each student individually (single-level analysis) and all of them combined (two-level analysis). Figure 2 shows individual student’s total scores across eight essays; the maximum score could be 52 in accordance with the rubric in Supplementary Appendix B.

Student 1 had medium and statistically significant gains in the quality of her persuasive writing, [β1 = 12.47, t(49) = 3.17, p = 0.02]: There is a 24% increase in her score. Students 5 and 8 had small and marginally statistically significant2 gains in the quality of their persuasive essays [β1 = 5.13, t(49) = 2.01, p = 0.091 and β1 = 4.33, t(49) = 2.04, p = 0.087, respectively]. Students 3, 6, and 7 had small increases in their essay scores but they were not statistically significant (Supplementary Appendix H). In contrast, Students 2 and 4 had small decreases in their essay scores as a result of the intervention; however, they were not statistically significant. The analysis by criteria revealed that Students 1 and 5 had small but statistically significant gains in language and conventions, and Students 1 and 7 had small but marginally statistically significant gains in development and conventions. Students 2 and 4 had small decreases in their scores on the focus and organization and language criteria, but they were not statistically significant (Supplementary Appendix I). The remaining students had small increases in their scores across four criteria, but they were not statistically significant.

The SRL writing intervention had a small and significant effect on the quality of students’ persuasive essays [θ10 = 3.66, t(49) = 2.38, p = 0.021]. That is, there was 7% or 3.66 points increase in persuasive writing scores across all students in the intervention phase. In addition, the estimates of the between-case variance () suggest less variability in students’ scores in the intervention phase than in the baseline phase ().

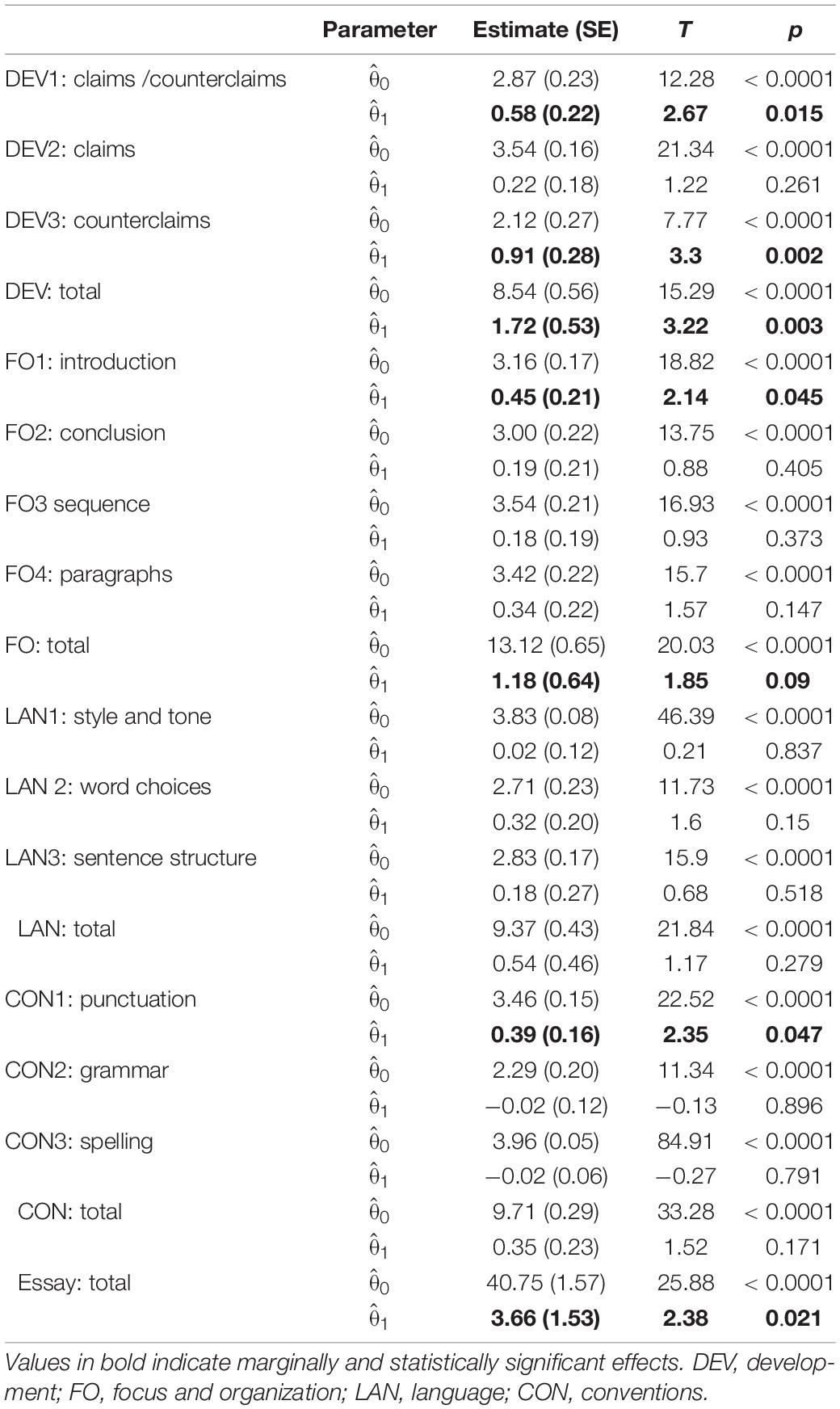

In terms of criteria (Table 2), Development had a small but statistically significant improvement as a result of the intervention [θ10 = 1.72, t(49) = 3.22, p = 0.003]. As a result of the intervention, there were gains in such sub-criteria as Claims and Counterclaims [θ10 = 0.58, t(49) = 2.67, p = 0.015], Explanation of Counterclaims [θ10 = 0.91, t(49) = 3.30, p = 0.002], Introduction [θ10 = 0.45, t(49) = 2.14, p = 0.045], and Punctuation [θ10 = 0.39, t(49) = 2.35, p = 0.047]. The remaining sub-criteria also had incremental increases, but they were not meaningful. However, the sub-criteria of grammar and spelling indicated incremental decreases, which were not meaningful as well. The data were less variable across students in the intervention phase for the majority of the sub-criteria except for Introduction (, ), Sentence Structure (), and Spelling (). The regression-based estimates indicate a small effect of the intervention on both individual and overall students’ persuasive writing.

Table 2. Results of the Two-level analyses of essay data by sub-criteria, criteria, and essay total.

The two-level analysis was conducted to examine the effect of the SRL writing intervention on students’ SRL skills both for each student individually (single-level analysis) and all of them combined (two-level analysis). Figure 3 shows individual student’s total scores across thirteen SRL journals; the maximum score could be 76 in accordance with the rubric in Supplementary Appendix D.

The SRL writing intervention resulted in a small, positive, and marginally statistically significant effect on the overall SRL skills of Student 4, [β1 = 5.00, t(68) = −1.99, p = 0.086]: There is a 6.6% increase in his scores. Students 3, 5, 6, and 8 also resulted in small and positive increases in their SRL skills. In contrast, the results of Students 1, 2, and 7 indicated small and negative effects on their SRL skills; however, none of these effects were statistically significant (Supplementary Appendix J). The results for Students 3, 5, and 7 should be interpreted with caution since these students had missing data.

The examination of students’ results for each SRL domain revealed some instances of small and statistically significant effects. For example, Student 5 had a small positive and marginally statistically significant effect of the SRL writing intervention on his goal-setting skills, [β1 = 1.46, t(68) = 2.19, p = 0.056]. The Progress Monitoring domain of the SRL turned out to be the most problematic criterion for the majority of students. For instance, Students 1 [β1 = −2.87, t(37) = −2.73, p = 0.021] and 2 [β1 = −3.3, t(37) = −5.00, p = 0.04] had a small negative and statistically significant effects of the intervention on their progress monitoring skills. The analyses for this criterion, however, could not be performed for Students 5 and 7 because there were many instances of missing data. Therefore, the results of the Progress Monitoring domain should be interpreted with caution.

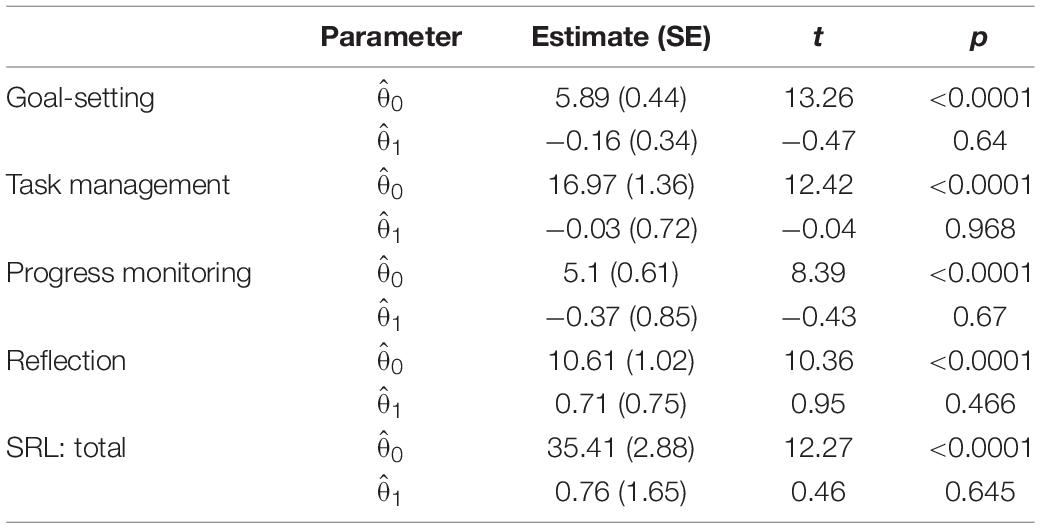

Based on the two-level analysis, the SRL writing intervention had a small and not statistically significant effect on students’ SRL skills, [θ10 = 0.76, t(68) = 0.46, p = 0.645]. The results by domains did not indicate statistically significant increases. In fact, Goal-setting, Task Management, and Progress Monitoring resulted in small and negative effects (Table 3). The between-case variance in the intervention phase for Goal-setting, Task Management, and Reflection resulted in small estimates, suggesting low levels of variability for these domains. In contrast, Progress Monitoring resulted in a high degree of variability in the intervention phase, , which may be the result of a large amount of missing data in that domain.

Table 3. Results of the two-level analyses of self-regulated learning (SRL) journals data by domains.

Based on the thematic analysis (Supplementary Appendix H), three broad themes were identified in regard to the students’ perceptions of the SRL component of the course: (1) SRL journal; (2) SRL knowledge and skills; and (3) suggestions.

All of the interviewed students (n = 6) talked about the SRL journal since it was one of the assignments that they had to do every class. Based on their responses, it can be concluded that students developed some understanding of the purpose of the task, and some of them were confused during the first classes. From Students’ 1 and 4 perspectives, the purpose of the SRL journal was as follows:

S1: I mean, I think all we forgot about the purpose of this activity, we just, “Oh we have to finish this, we have to finish that.”

I(nterviewer): What is the goal of this activity?

S4: It’s setting your goal and reflecting your strategies.

Generally, students had mixed feelings about this task: On one hand, they recognized its value. For example, Student 4 described his experience with the journal in the following terms: “… it’s helpful to view yourself back. What you’re wrong, and what you’re right”. On the other hand, they were dissatisfied with the length of the journal and frequency with which they had to work on it: “It is useful, … but just too many” (Student 4).

This overview of the SRL journal theme indicates that students did not have a clear understanding of what they were supposed to do with this task, even though they could articulate a primary goal of the SRL journals.

Students also reflected on the SRL knowledge and skills that they had used during the intervention. One of the re-occurring topics in both focus group interviews was strategy use and how it takes time to develop a habit of using new strategies. For example, Student 5 mentioned that “… it remind(s) me that I need use some strategies, I can’t just write.”

Nevertheless, several students expressed their concern regarding the use of new strategies. Thus, Student 2 said: “For me it’s hard to change my writing strategy so … It’s hard to get used to it … the new things so. I tried but it doesn’t go long, it goes only one or 2 days.” Student 7, in turn, repeated multiple times that it takes time to develop new strategies: “I believe that creating and applying the new strategy, a new logic is … uh, is uh, it takes a very long time.”

Another finding is students’ appreciation of feedback they received from their peers and teacher. All of them enjoyed participating in the peer review activities, which were part of the class. Some students felt uncomfortable providing feedback to each other at first. They felt as if they were judging their peers, and it made them feel awkward because they did not know each other well, “So, we did a lot peer review. … We switched like, our essay and reading, and after reading, we have to talk about like, “That part is good, this part is not that good” But I understand that, the purpose, but it’s really awkward to say like-… You have to do better at that part, because we’re not really friendly each other…. I kind of feel bad, you know what I mean” (Student 1). However, as they had more exposure to peer feedback, they valued this experience because it gave them an opportunity to see how other people write and what kind of writing techniques they use. For example, Student 1 mentioned “I thought I did like, perfectly, and when I get that part review, oh I missed that part. So I can realize what parts I have to improve.”

All of the students were unhappy about the frequency with which they had to fill out the SRL journal and its length. Students provided suggestions for ways in which the journal could be improved. For example, three students suggested making the SRL journal assignment less frequent and reducing the number of questions in it. Thus, Student 1 commented on the frequency of the assignment, “I mean, every week we have to do that … I wanna reduce that.”

Another set of suggestions focused on the writing genres and strategies used in the course. For example, Student 6 expressed her concern about writing only persuasive essays, and she wanted to learn how to write in other genres as well, “I think it should be more various. So it can be boring. I want to practice some various writing …”

Finally, most of the students were confused about the SRL strategies and expressed their concern regarding the knowledge of various strategies. Student 6 explained, “In my case, the last question [regarding new strategies to use] was hard to answer… Because like I have, like, no idea about the other strategies, um, yeah. So I am not sure what to write… That I, I didn’t know many strategies. I know only few strategies that I tried.” In this way, they suggested providing a more detailed instruction of the SRL strategies in future.

These results suggest that students’ perceptions of the SRL component were mixed. On the one hand, they appreciated the experience of reflecting on their learning and self-regulation in writing. On the other hand, they did not like the format: They considered the journal to be too frequent, long, and repetitive. In addition, some of the students did not know of new strategies, or they needed more time to get used to new strategies. In spite of these setbacks, students admitted to using some SRL strategies in other courses.

The goals of this study were: (1) to help multilingual students improve their persuasive writing and SRL skills, (2) to examine the effectiveness of the SRL writing intervention in an authentic classroom setting, and (3) to suggest modifications to the SSAW intervention in an attempt of the intervention development.

The results of the statistical analyses provided weak evidence of an effect of the intervention on persuasive writing skills across all students. There was an average of 7% increase in students’ scores, which is an incremental improvement in comparison with other writing interventions (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2013; Harris et al., 2015; MacArthur et al., 2015; Ennis, 2016; Teng and Zhang, 2020). Even though the increase in scores is small, it still indicates improvement in students’ writing skills.

Examination of the results by criteria and sub-criteria across all students also indicated increases for some of them. The criteria of Focus and Organization, Language, and Conventions did not indicate large increases. However, a statistically significant increase in scores was observed for the Development criterion. A plausible explanation of these increases is related to the nature of the intervention: Students were taught how to write persuasive essays, practiced writing about the Claims and Counterclaims, and learned how to effectively explain Counterclaims during the course. That is, students learned how to produce texts within the genre of persuasive writing. Overall, the two-level analysis results suggest that improvements were observed for the criteria and sub-criteria which were explicitly taught and repeatedly practiced during the course.

The results of the statistical analyses provided weak evidence of intervention effectiveness in improving persuasive writing skills for Students 1, 5, and 8. The largest improvement in terms of the effect size and statistical significance was observed for Student 1: There was a 24% increase in her score. Interestingly, this is the only student in the sample (n = 8) who graduated from an American high school and did not have to take the standardized assessment of proficiency in English. It is possible that the gains of Student 1 could be due to familiarity with the American educational system and culture (Foster, 2004), which made it easier for her to adapt to the tasks and environment. The other two students who benefitted from the intervention scored in the 65–80 range on the TOEFL. Writing interventions are typically effective for students with medium English proficiency levels (Manchón, 2011; Pasquarella, 2019), which explains the gains of Students 5 and 8.

Lack of improvement in other students’ persuasive writing skills can possibly be attributed to their unfamiliarity with the cultural and language expectations of American classrooms (Elbow, 1999; Ramanathan and Atkinson, 1999; Foster, 2004). For example, most of the students admitted during the focus group interview that it was their first time participating in peer review activities. Some of the students felt “awkward” or that they were “judging each other” when providing feedback on their essays. They were shy and reserved at the beginning of the course because of their language skills: It took some time to encourage the students to speak and contribute to discussions during classes. These findings echo research on Asian students’ reactions toward peer review in American classrooms (Atkinson, 2016).

The results of the statistical analysis of the SRL journal data indicated no evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention on students’ SRL skills. This result must be interpreted with caution, however, given evidence of the psychometric weaknesses of the SRL journal used in this study. Examination of the SRL journals and focus group interviews suggested that the journal was not a valid measure to assess students’ SRL skills because they either did not (1) understand how to respond to some of the questions, or (2) take it seriously. Typically, journals are used both to promote and measure SRL skills (Schmitz et al., 2011), and their use is associated with improvement in students’ reflection, SRL skills, and learning outcomes (Schmitz and Wiese, 2006). Journaling is also associated with positive attitudes to schooling and development of reflective and literacy skills among multilingual students (Walter-Echols, 2008; Linares, 2019). In contrast, in this study, the use of journals to promote and measure SRL skills turned out to be unsuccessful because students failed to monitor and reflect on their learning, at least in writing.

Possible explanations of this failure include the influence of culture and students’ attitudes toward and experiences with this activity (Atkinson, 2016). All eight students were from Southeastern Asia; they might not have felt comfortable freely expressing their thoughts and ideas (Walter-Echols, 2008). It seemed that some of them lacked guidance on how to fill out the journals. Finally, all of them admitted that it was their first experience journaling in their academic careers, which was probably one of the reasons they did not take full advantage of learning from the SRL journals.

These findings are in a stark contrast with the findings of other studies. For example, Santangelo et al. (2016) reported medium effect sizes for goal-setting and cognitive strategy instruction combined with self-evaluation and self-monitoring, and large effect sizes for the cognitive strategy instruction in their meta-analysis of 79 quasi- and experimental studies, examining the effectiveness of the SRL and writing instruction. MacArthur and Philippakos (2012, 2013) and MacArthur et al. (2015) reported increases in students’ mastery goals and self-efficacy for writing. In this study, in contrast, the domains of goal-setting, task management, and progress monitoring resulted in small negative effects, and reflection in small positive effects, even though not statistically significant. Similarly, Altas and Mede (2021) investigated the effect of the flipped classroom on pre-service teachers’ (n = 55) writing achievement and SRL. The results indicated increases in writing achievement, but no effects on SRL, which was measured using the self-report survey. It is worth reiterating that in the current study, the results are based on the data from the SRL journal, which turned out to be an invalid measure. Therefore, a further investigation of the effectiveness of the SRL writing intervention on students’ SRL skills is warranted since existing research shows that teaching students to self-regulate writing improves their writing outcomes and some of the SRL processes (MacArthur et al., 2015; Graham et al., 2016; Santangelo et al., 2016; Teng and Zhang, 2020).

The focus group interviews shed light on the mixed results of the SRL writing intervention on students’ SRL skills. Overall, students did not value the use of the SRL journal during the writing intervention, which is likely the reason the SRL journal turned out to be a flawed measure. At least five students mentioned in the interview that the SRL journal assignments were too frequent, repetitive, and long. Students perceived the SRL journal as an “annoying” and “boring” activity they had to do every class. This can explain the negative effects on students’ goal-setting, task management, and progress monitoring domains of SRL: The quality of students’ journal entries became worse toward the end of the semester at least in part because they disliked having to write them.

Also, only Student 6 understood aspects of the SRL-related content of the journals. That is, she recognized that her goals for the new writing assignments should be based on the feedback she had received on her previous assignments. This means that Student 6 could understand the feedback she received and chose to act upon it to improve her performance on following assignments (Ruiz-Primo and Li, 2013; Goldstein, 2016). In addition, Student 6 had the highest baseline scores for her essays, which suggests that she had a high level of knowledge (i.e., declarative, procedural, and conditional; Pressley and Harris, 2008) of persuasive writing and had the resources (i.e., cognitive and motivational) to reflect on what areas she still needed to improve on in her SRL journals (Harris et al., 2011). Consistent with the research on feedback and multilingual writing, this means that other students were confused on how to act upon the feedback they received (Goldstein, 2016), and that they should have been explicitly taught that some of the areas in need of improvement from the previous essay could serve as writing goals for a new essay (Cumming, 2012).

Examination of the SRL journals confirms that some students did not take the journal assignments seriously. Past mid-semester, students either wrote the same responses for the remaining journals (Students 1 and 2), or skipped some of the questions (Student 7). Their results were worse than for other students in the sample, or could not be calculated like for Students 5 and 7 in Progress Monitoring domain. A possible explanation for students’ difficulty in addressing questions about progress monitoring could be that students lacked declarative knowledge about the SRL strategies (McCormick, 2003; Pressley and Harris, 2008), or when they tried to apply new strategies, they were inconsistent in their use (Harris et al., 2011). The interviews also revealed that at least four out of six interviewed students did not recognize that planning, formulating, reviewing, revising, and providing feedback on each other’s essays were actually macro-level writing strategies (Manchón et al., 2007) that they could have written about in their journals.

If to situate the results of the SRL writing intervention within the Model of Self- and Socially Regulated Multilingual Writing (Figure 1), we can conclude that the instruction in persuasive writing (A) resulted in improved knowledge (C) on how to write persuasive essays (J) for some students in this sample. However, the focus group interviews revealed that at least five of the six interviewed students had difficulties with writing strategies knowledge (C). Students had gains in discussing claims and counterclaims as well as in developing counterclaims sub-criteria, which contributed to their domain knowledge of persuasive writing (C). In addition, they enjoyed the formative feedback provided/received (K) because it gave them an opportunity to learn from each other (L). It is also worth noting the influence of students’ cultural and educational backgrounds (O) during the intervention: Students started as passive participants of the learning process, feeling shy and awkward while participating in classroom discussions and peer review activities. As the semester progressed, they developed some confidence and recognized the value of learning from each other. This observation warrants further examination of the cultural changes, if any, happening in writing classrooms with multilingual students (Atkinson, 2016).

In contrast, the SRL writing intervention had mixed and hard to interpret effects on student’s goal-setting (E), task management (F–G), progress monitoring (H), and reflection (N) skills. Based on the results, the use of journals to promote and measure SRL skills turned out to be unsuccessful because students failed to monitor (H) and reflect (N) on their learning, at least in writing. Nevertheless, students reported appreciating the SRL knowledge and skills (F) they gained.

The results described above should be interpreted with caution due to the limitations of this study, which may prevent generalizing its findings to a wider population of ELs and other settings. Limitations include: (1) convenience sampling, (2) use of self-report data to measure SRL skills, (3) small sample size, and (4) the curriculum which was developed for native speakers of English.

Due to the use of convenience sampling in this study, findings may not be generalizable to a wider population of ELs (Gall et al., 2007). Convenience sampling might have introduced sampling error in terms of having a non-representative sample of students coming from a particular country – South Korea. Meanwhile, there were a large number of students coming from India, Pakistan, and some Middle Eastern countries on campus.

The SRL journals were used in this study to measure SRL skills, which is a self-report measure that provides a limited view of students’ SRL from a retrospective viewpoint (Winne and Perry, 2000; Greene et al., 2011). The SRL journals used in this study proved to be an invalid instrument to measure SRL skills because students did not take them seriously. As a result, it is desirable to triangulate SRL data from the self-report with additional data such as think aloud protocols or trace data (Winne and Perry, 2000; Greene et al., 2011; Azevedo et al., 2013). While these techniques could help with triangulating SRL measurements, it was not feasible to use them in the current study due to difficulty of a writing task.

Another limitation of this study is a small sample size and attrition. While eight participants were enough to run parametric tests for SCED data, this number was not large enough to run moderator analyses. There were instances of missing data both for essays and SRL journals, which affected the overall results. Finally, the curriculum SSAW (MacArthur and Philippakos, 2012) was originally developed for the native writers of English. While it has been appropriate for the English learners in this study and generated similar results in terms of improving students’ persuasive writing skills, it still needs to be tailored to the needs of multilingual writers.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to its field in terms of intervention development, which is the creation of new methods to change/improve desired behaviors and outcomes (Hayes et al., 2013). In this study, intervention development refers to the adjustments that should be made to the SRL writing intervention based on the findings. The use of the SCED resulted in the collection of the detailed information on all eight participants: Their writing and SRL outcomes, which were measured repeatedly during the semester. While we did not modify the SRL writing intervention based on the students’ needs during the study, an in-depth analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data provided evidence on how diverse participants and their needs were. For example, while most of the students had high baseline overall writing scores, a closer examination by sub-criteria revealed that they needed targeted instruction for particular sub-criteria, including Spelling, Grammar, Word Choices, and Sentence Structure. The criteria and sub-criteria that improved as a result of the intervention were explicitly taught during the course. Therefore, modifications to the SRL writing intervention should incorporate explicit instruction of sub-criteria of interest. As is evident from the narrative above, strength of this study is intervention development which provides evidence for the informed adjustments to the SRL writing intervention.

As future steps, we recommend making changes to the intervention such as: (1) using a more rigorous SCED or a traditional experimental design; (2) conducting moderator analyses; (3) identifying cut-off scores for effect sizes; (4) making changes to the SRL journal; and (5) examining the nature and quality of feedback to oneself and peers. Hence, the observation of the largest improvement in Student 1’s writing skills warrants further examination of the nature of writing skills that multilingual students gain in secondary schools in the United States, and possibly tailoring the interventions to the needs of this particular group of students when they start college.

Finally, the Model of Self- and Socially-Regulated Multilingual Writing incorporates various cognitive, behavioral, affective, and socio-cultural processes, most of which are grounded in research in educational psychology and multilingual writing. There are some of the elements in the model that have not been rigorously examined from the perspective of multilingual writing. For example, Kormos (2012) calls for research in the area of motivation in multilingual writing. Similarly, there are not any research studies examining task interpretation of writing tasks, and very little research on goal-setting (Cumming, 2012), self-assessment, progress monitoring, reflection, and metacognition in multilingual writing. In addition, it is important to examine the influence of culture and students’ previous cultural experiences with writing in English both in their home countries and in countries where English is used as the medium of communication (Atkinson, 2016; Bazerman et al., 2018). Therefore, future researchers should consider designing rigorous studies to examine these processes with the population of ELs in terms of multilingual academic writing.

In sum, the SRL writing intervention had a weak effect on improving students’ persuasive writing skills but the results regarding their SRL skills were mixed and difficult to interpret because of problems with the measures. It is hard to tell what part of the intervention contributed to students’ gains in writing: (1) Writing instruction, (2) SRL instruction, or (3) a combination of both, because SRL was embedded in the persuasive writing curriculum. This warrants a further examination of the effectiveness of the intervention using a different research design and SRL measures. Nevertheless, this study contributes to the growing body of literature introducing and encouraging SRL instruction along with multilingual writing skills among ELs. Given the promising results from other studies (Fathi and Feizollahi, 2020; Teng and Zhang, 2020; Altas and Mede, 2021; Chen et al., 2021), and some evidence of students’ appreciation of SRL knowledge in this study, we can conclude that SRL instruction, can potentially make writing courses enriching. To detect changes in ELs’ SRL skills, however, future studies should employ more valid and powerful measures than the self-report surveys and journals.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University at Albany Institutional Review Board, University at Albany - State University of New York (SUNY). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

DA performed material preparation, data collection, analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the study conception and design, commented on previous versions of the manuscript, read, and approved the final version.

This research was supported by the internal funds available at the University at Albany – SUNY: the Spring 2019 Graduate Student Association Grant Research Award, Dissertation Research Fellowship 2018–2019 Award, Summer 2018 University at Albany Initiative for Women Award, and Fall 2017 University at Albany Benevolent Association Research Grant.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

DA would like to express gratitude to Heidi Andrade, Mariola Moeyaert, and Kristen Wilcox for guiding me through this study. In addition, this study would not have seen light without the financial support provided by the University at Albany – State University of New York.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.841395/full#supplementary-material

Akhmedjanova, D. (2020). The Effects of a Self-Regulated Writing Intervention on English Learners’ Academic Writing Skills. (Publication No. 27836830). Doctoral dissertation. Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Altas, E. A., and Mede, E. (2021). The impact of flipped classroom approach on the writing achievement and self-regulated learning of pre-service English teachers. Turk. Online J. Dist. Educ. 22, 66–88. doi: 10.17718/tojde.849885

Anderson, V. (2017). Criteria for evaluating qualitative research. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 28, 125–133. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.21282

Andrade, H. (2013). “Classroom assessment in the context of learning theory and research,” in Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. J. H. McMillan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 17–34. doi: 10.4135/9781452218649.n2

Andrade, M. S., and Evans, N. W. (2013). Principles and Practices for Response in Second Language Writing: Developing Self–Regulated Learners. London: Routledge.

Atkinson, D. (2016). “Second language writing and culture,” in Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing, eds R. M. Manchón and P. K. Matsuda (Berlin: Walter de Gruyte), 545–565. doi: 10.1515/9781614511335-028

Azevedo, R., Harley, J., Trevors, G., Duffy, M., Feyzi_Behnagh, R., Bouchet, F., et al. (2013). “Using trace data to examine the complex roles of cognitive, metacognitive, and emotional self-regulatory processes during learning with multi-agents systems,” in International Handbook of Metacognition and Learning Technologies, eds R. Azevedo and V. Aleven (Berlin: Springer – Verlag), 427–449. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-5546-3_28

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., Christensen, R. H. B., Singmann, H., et al. (2019). lme4 package [R package]. Available online at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html (accessed June 22, 2021).

Bazerman, C., Applebee, A. N., Berninger, V. W., Berninger, V. W., Brandt, D., Graham, S., et al. (2018). The Lifespan Development of Writing. Champaign, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butler, D. L., and Winne, S. F. (1995). Feedback and self-regulated learning: a theoretical synthesis. Rev. Educ. Res. 65, 245–281. doi: 10.3102/00346543065003245

Canagarajah, A. S. (2002). A Geopolitics of Academic Writing. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt5hjn6c

Canagarajah, A. S. (Ed.) (2013). Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Communities and Classrooms. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203120293

Casanave, C. P. (2016). “Qualitative inquiry in L2 writing,” in Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing, Vol. 11, eds R. M. Manchón and P. K. Matsuda (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG), 519–544. doi: 10.1515/9781614511335-027

Chen, J., Zhang, L. J., and Parr, J. M. (2021). Improving EFL students’ text revision with the self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) model. Metacogn. Learn. 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11409-021-09280-w

Cheng, L., Myles, J., and Curtis, A. (2004). Targeting language support for non-native English- speaking graduate students at a Canadian University. TESL Can. J. 21, 50–71. doi: 10.18806/tesl.v21i2.174

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Cumming, A. (2012). “Goal theory and second-language writing development, two ways,” in L2 Writing Development: Multiple Perspectives, ed. R. Manchón (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG), 135–164. doi: 10.1515/9781934078303.135

Cumming, A. (2016). “Theoretical orientations to L2 writing,” in Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing, Vol. 11, eds R. M. Manchón and P. K. Matsuda (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG), 65–90. doi: 10.1515/9781614511335-006

De Corte, E., Mason, L., Depaepe, F., and Verschaffel, L. (2011). “Self-regulation of mathematical knowledge and skills,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance, eds B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk (London: Routledge), 155–172.

Dent, A. L., and Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 425–474. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacogn. Learn. 3, 231–264. doi: 10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

Elbow, P. (1981). Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elbow, P. (1999). Individualism and the teaching of writing: response to Vai Ramanathan and Dwight Atkinson. J. Second Lang. Writ. 8, 327–338. doi: 10.1016/S1060-3743(99)80120-9

Ennis, R. P. (2016). Using self-regulated strategy development to help high school students with EBD summarize informational text in social studies. Educ. Treat. Child. 39, 545–568. doi: 10.1353/etc.2016.0024

Farsani, M. A., Beikmohammadi, M., and Mohebbi, A. (2014). Self-regulated learning, goal-oriented learning, and academic writing performance of undergraduate Iranian EFL learners. Electron. J. Engl. Second Lang. 18, 1–19.

Fathi, J., and Feizollahi, B. (2020). The effect of strategy-based instruction on EFL writing performance and self-regulated learning. ZABANPAZHUHI (Journal of Language Research) 11, 23–45.

Flower, L., and Hayes, J. R. (1981). A cognitive process theory of writing. Coll. Compos. Commun. 32, 365–387. doi: 10.2307/356600

Foster, M. K. (2004). Coming to terms: a discussion of John Ogbu’s cultural-ecological theory of minority academic achievement. Intercult. Educ. 15, 369–384. doi: 10.1080/1467598042000313403

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., and Borg, W. R. (2007). An Introduction to Educational Research. London: Pearson.

Gardner, S., and Nesi, H. (2013). A classification of genre families in university student writing. Applied linguistics 34, 25–52. doi: 10.1093/applin/ams024

Goldstein, L. M. (2016). “Making use of teacher written feedback,” in Handbook of Second and Foreign Language Writing, Vol. 11, eds R. M. Manchón and P. K. Matsuda (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG), 407–430. doi: 10.1515/9781614511335-022

Graham, S. (2006). “Strategy instruction and the teaching of writing: a meta-analysis,” in Handbook of Writing Research, eds C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, and J. Fitzgerald (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 187–207.

Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer (s)-within-community model of writing. Educ. Psychol. 53, 258–279. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406

Graham, S., and Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 445–476. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., and Chambers, A. B. (2016). “Evidence-based practice and writing instruction,” in Handbook of Writing Research, 2nd Edn, eds C. A. MacArthur, S. Graham, and J. Fitzgerald (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 211–226.

Greene, J. A., Bolick, C. M., Caprino, A. M., Deekens, V. M., McVea, M., Yu, S., et al. (2015). Fostering high-school students’ self-regulated learning online and across academic domains. The High School Journal 99, 88–106. doi: 10.1353/hsj.2015.0019

Greene, J. A., Robertson, J., and Costa, L. C. (2011). “Assessing self-regulated learning using think-aloud methods,” in Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance, eds B. J. Zimmerman and D. H. Schunk (London: Routledge), 313–328.

Han, Y., Zhao, S., and Ng, L. L. (2021). How technology tools impact writing performance, lexical complexity, and perceived self-regulated learning strategies in EFL academic writing: a comparative study. Front. Psychol. 12:752793. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.752793

Harris, K. R., Graham, S., and Adkins, M. (2015). Practice-based professional development and self-regulated strategy development for Tier 2, at-risk writers in second grade. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 40, 5–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.02.003