A Commentary on

The use of simulated patients in medical education: AMEE Guide No 42

by Cleland, J. A., Abe, K., and Rethans, J. J. (2009). Med. Teach. 31, 477–486. doi: 10.1080/01421590903002821

Simulation based education

by Cleland, J. A. (2017). Psychologist 30, 36–40.

Building Academic Staff Capacity for Using eSimulations in Professional Education for Experience Transfer

by Cybulski, J., Holt, D., Segrave, S., O'Brien, D., Munro, J., Corbitt, B., et al. (2010). Sydney, NSW: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Student and staff views of psychology OSCEs

by Sheen, J., McGillivray, J., Gurtman, C. and Boyd, L. (2015). Aust. Psychol. 50, 51–59. doi: 10.1111/ap.12086

The Australian Postgraduate Psychology Education Simulation Working Group (APPESWG) recently published guidelines titled “A new reality: The role of simulated learning activities in postgraduate psychology training programs” (Paparo et al., 2021). The document was developed in the context of COVID 19-related disruption to practica within professional psychology training. As a consequence, many training providers adopted simulated training activities as a way to support course progression during the pandemic. Paparo and colleagues' stated aims were to provide comprehensive guidance for the use of simulation as a competency-based training tool and in the interests of public and student safety, both during and after COVID 19. The guidelines included nine criteria for best practice in simulated learning activities in training, for example, that activities should be competency-based, should mirror real-life practice situations and should provide opportunities for active participation and trainee reflection (see Paparo et al. for detail). The document provided helpful guidance on the use of simulated learning activities (SLA) as part of course content within an Australian professional psychology training context, however the guidelines did not cover simulated placement experiences. Considerations especially around supervision and the development of professional and ethical practice within a simulated learning environment need to be made to effectively apply the APPESWG Guidelines within a placement context. Here, we extend these guidelines for provision of simulated professional psychology placements based on our successful development and implementation of large-scale simulated placements at an Australian University (2020—current). Previously, all professional psychology placements in Australia were limited to in-vivo options, however the latest version of the Accreditation Standards for Psychology Programs (Australian Psychology Accreditation Council, 2019) now make provision for simulated learning within required placement experiences at Level 3, Professional Competencies. This extension of the Paparo et al. (2021) article provides guidelines specifically for the use of simulation with professional psychology placements, with a focus on the Australian context.

Advantages of Simulated Placements

The provision of simulated placement experiences (beyond incorporation of simulated activities in teaching) has many benefits. Firstly, simulated placements provide standardization of professional psychology placements, reducing the variability of in-vivo placements. This has the additional benefit of making placement experiences reproducible (Lateef, 2010) and consistent across cohorts. Secondly, simulated placement experiences offer professional psychology training to those residing in rural and remote areas, which often have high demand for practitioners but very few opportunities to access supervised practicum. Thirdly, the option to consider simulated placement experiences has provided a viable and timely alternative for training in professional psychology programs within the COVID-19 context, which rendered face-to-face placements difficult to source (Cosh et al., 2021). Fourth, simulated placement experiences protect clients from novice practitioners (Lateef, 2010), and provide a lower risk context for students to practice working with difficult presentations (e.g., management of risk of harm) (Lucas, 2014). Fifth, simulation facilitates the assessment of student performance (Lateef, 2010), and ensures students are competent before seeing actual clients. Furthermore, simulation in placements offers the benefit of repeated and intentional practice with feedback to enhance retention and skills, and structured experience with presentations that are uncommon and rare for students to gain exposure to (Maran and Glavin, 2003; Lateef, 2010). Simulated placements are common in other health fields, such as nursing, medicine and allied health (Imms et al., 2018) and use of simulation for placements aligns psychology with these other disciplines.

Guidelines For Simulated Learning in Professional Psychology Placements

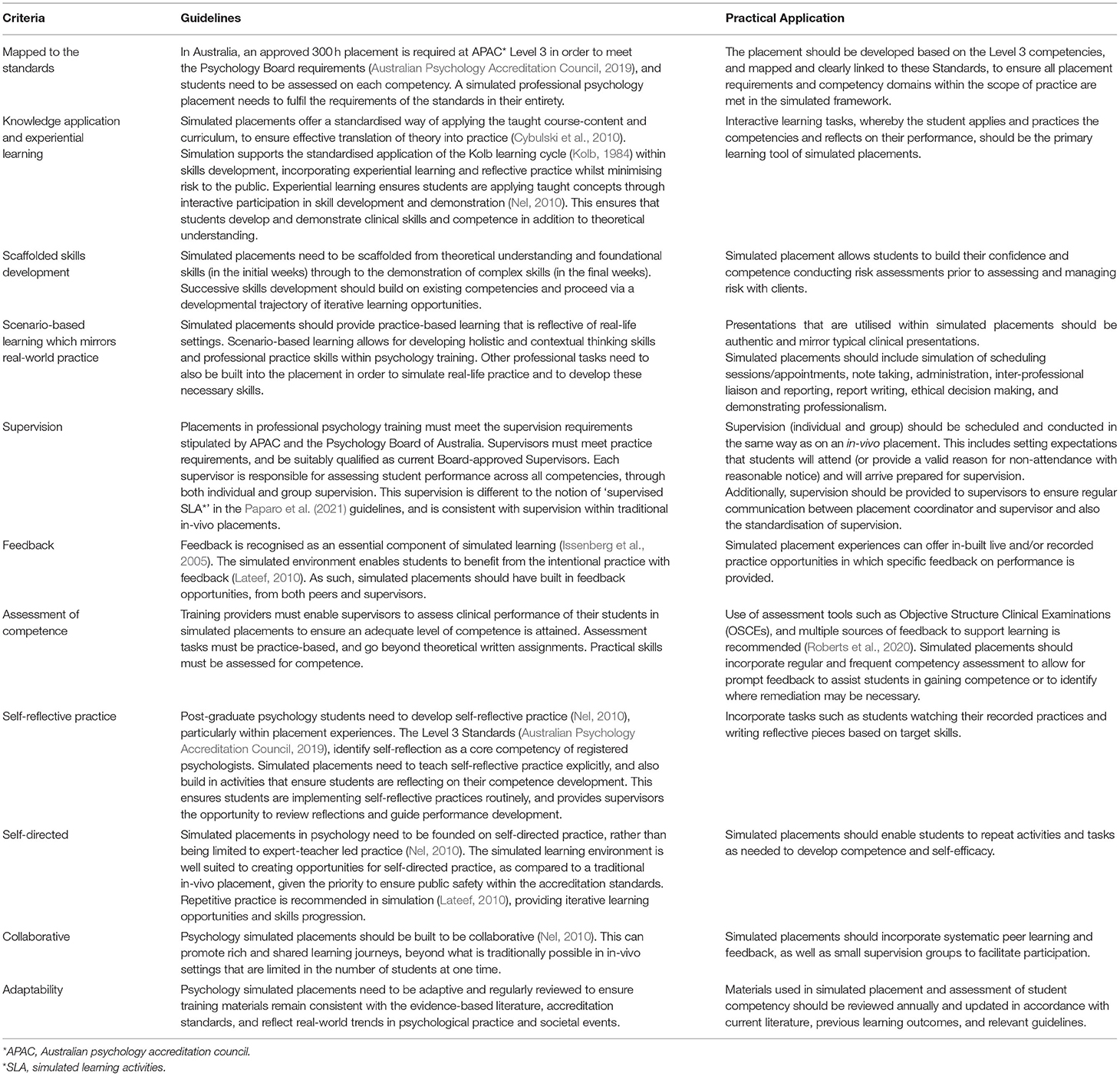

Table 1 provides guidelines for the explicit application of simulated learning within placement experiences in professional psychology.

Educational Outcomes

A considerable body of research from medical and allied health fields suggests that students who have engaged in simulation-based education perform better on subsequent clinical tasks. For example, a group of students who undertook simulated training prior to attending ward-based training performed twice as well, and in half the training time, as the group who only attended ward training (Lateef, 2010). Wright et al. (2018) found that simulation placements undertaken by final year physiotherapy students resulted in increased self-confidence across all skill areas. These students also achieved significantly higher competence grades compared to students who had undertaken the traditional in-vivo placement in their final year on a standardized clinical competence measure used in physiotherapy training. Beyond simulation reducing risk to the public during training, simulated training has been associated with increased performance (Liaw et al., 2010) and improved client outcomes (Lateef, 2010).

Challenges

There are, indeed, some limitations to simulated placement experiences. For example, the limitations of role plays pose challenges in simulating a whole course of treatment or all psychometric assessments. Moreover, simulation precludes trainee exposure to the administrative side of running a service; and poses additional cost of developing with requisite training and support needed for staff to implement and sustain such models, although these challenges may be managed through explicitly specifying to the learner the differences between the simulated vs. real life clinical environment (Maran and Glavin, 2003). Furthermore, the real-world client outcomes after simulated psychology training have yet to be investigated, necessitating research in this area.

A further challenge is the limited evidence base for the effectiveness of simulated training in psychology. Paparo and colleagues reported that their guidelines represent the first attempt internationally to establish consensus around best practice in the use of simulated learning activities. Cleland (2017) noted very low uptake of simulated learning within clinical psychology training in the UK, despite its obvious advantages in the context of competency-focused training and the need to ensure public safety. She drew a parallel between contemporary psychology training and medical training of two decades ago, citing barriers around the absence of a relevant evidence base and a lack of expertise in simulation amongst trainers. The current widespread use of simulation in medical training could therefore provide a model for the future of psychology training. Indeed, those at the forefront of introducing simulation-based training in psychology in Australia are adopting assessment techniques currently used in medical training e.g. the Objective Structured Clinical Exam (Sheen et al., 2015). This is appropriate in view of the overlap in quality markers for effective simulated training between medicine and psychology, such as repetitive practice, feedback and increasing difficulty (Issenberg et al., 2005; Cleland et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Simulation now offers a viable alternative or supplement to in-vivo options within APAC Level 3 Standards for professional psychology programs and can overcome barriers with sourcing placements and physical distances particularly for trainees in rural and remote locations, whilst providing a consistent training experience across the scope of psychological practice and reducing risk for actual clients. Training providers seeking to introduce a simulated placement should ensure that the simulated environment includes appropriate supervision and suitable opportunities for competency development and demonstration. We recommend incorporating experiential learning, reflective practice, skills-based assessment and self-directed learning. We also recommend the use of real-world scenarios which develop professional and ethical skills, including report writing and inter-professional liaison. Simulation can be used beyond SLAs to provide a standardized, practice-based, experiential training opportunity that meets all accreditation standards while safeguarding the public in early stage of learning.

Author Contributions

KR wrote the draft of this article. All authors contributed to editing the draft of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Australian Psychology Accreditation Council (2019). Accreditation Standards for Psychology Programs, Effective 1 January 2019, Version 1.2. Australian Psychology Accreditation Council. Retrieved from https://psychologycouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/APAC-Accreditation-Standards_v1.2_rebranded.pdf

Cleland, J. A., Abe, K., and Rethans, J. J. (2009). The use of simulated patients in medical education: AMEE Guide No 42. Med. Teach. 31, 477–486. doi: 10.1080/01421590903002821

Cosh, S., Rice, K., Bartik, W., Jefferys, A., Hone, A., Murray, C., et al. (2021). Acceptability and feasibility of telehealth as a training modality for trainee psychologist placements: a COVID-19 response study. Austral. Psychol. 57, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/00050067.2021.1968275

Cybulski, J., Holt, D., Segrave, S., O'Brien, D., Munro, J., Corbitt, B., et al. (2010). Building Academic Staff Capacity for Using eSimulations in Professional Education for Experience Transfer. Sydney, NSW: Australian Learning and Teaching Council.

Imms, C., Froude, E., Chu, E. M. Y., Sheppard, L., Darzins, S., Guinea, S., et al. (2018). Simulated versus traditional occupational therapy placements: a randomised controlled trial. Austral. Occup. Ther. J. 65, 556–564. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12513

Issenberg, S. B., Mcgaghie, W. C., Petrusa, E. R., Gordon, D. L., and Scalese, R. J. (2005). Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med. Teach. 27, 10–28. doi: 10.1080/01421590500046924

Kolb, D. A.. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lateef, F.. (2010). Simulation-based learning: just like the real thing. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock 3, 348–352. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.70743

Liaw, S. Y., Chen, F. G., Klainin, P., Brammer, J. A. O., and Samarasekera, D. D. (2010). Developing clinical competency in crisis event management: an integrated simulation problem-based learning activity. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 15, 403–413. doi: 10.1007/s10459-009-9208-9

Lucas, A. N.. (2014). Promoting continuing competence and confidence in nurses through high-fidelity simulation-based learning. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 45, 360–5. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20140716-02

Maran, N. J., and Glavin, R. J. (2003). Low- to high-fidelity simulation – a continuum of medical education? Med. Educ. 37 (Suppl. 1), 22–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.37.s1.9.x

Nel, P. W.. (2010). The use of an advanced simulation training facility to enhance clinical psychology trainees' learning experiences. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 9, 65–72. doi: 10.2304/plat.2010.9.2.65

Paparo, J., Beccaria, G., Canoy, D., Chur-Hansen, A., Conti, J. E., Correia, H., et al. (2021). A new reality: the role of simulated learning activities in postgraduate psychology training programs. Front. Educ. 6:653269. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.653269

Roberts, R. M., Oxlad, M., Dorstyn, D. S., and Chur-Hansen, A. (2020). Objective structured clinical examinations with simulated patients in postgraduate psychology training: student perceptions. Austral. Psychol. 55, 488–497. doi: 10.1111/ap.12457

Sheen, J., McGillivray, J., Gurtman, C., and Boyd, L. (2015). Student and staff views of psychology OSCEs. Aust. Psychol. 50, 51–59. doi: 10.1111/ap.12086

Keywords: simulation, psychology, simulated learning, practicum, placement, APPESWG Guidelines, the Australian Postgraduate Psychology Education Simulation Working Group, a new reality: The role of simulated learning activities in postgraduate psychology training programs

Citation: Rice K, Murray CV, Tully PJ, Hone A, Bartik WJ, Newby D and Cosh SM (2022) Commentary: An Extension of the Australian Postgraduate Psychology Education Simulation Working Group Guidelines: Simulated Learning Activities Within Professional Psychology Placements. Front. Educ. 7:840258. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.840258

Received: 20 December 2021; Accepted: 10 February 2022;

Published: 31 March 2022.

Edited by:

Fabrizio Consorti, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Giulia Rampoldi, University of Milano Bicocca, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Rice, Murray, Tully, Hone, Bartik, Newby and Cosh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kylie Rice, a3lsaWUucmljZUB1bmUuZWR1LmF1

Kylie Rice

Kylie Rice Clara V. Murray

Clara V. Murray Phillip J. Tully

Phillip J. Tully Alice Hone

Alice Hone Warren J. Bartik

Warren J. Bartik Suzanne M. Cosh

Suzanne M. Cosh