- 1Department of Early Childhood and Pre-primary Education, Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda

- 2Department of Educational Psychology, Masinde Muliro University of Science & Technology, Kakamega, Kenya

Human flourishing has recently gained more attention in the world as a prerequisite safety net for better human resilience in uncertain times. While most Western authors believe that human flourishing is an individual issue, gained in later life, African communities that are largely communal may not have the same view. Communalism as opposed to individualism as a key pillar in African Ubuntu thinking makes it a possibility that there is a departure in the contextualisation of human flourishing and its pathways. This explores the African conceptualisation of flourishing in the Ubuntu lens and how communities are coming together to cultivate it by implementing home based early childhood learning centres. Desk review was used to learn the contextual meaning of human flourishing and different pathways to it in African community settings. Home based early learning centres operated by parents was seen as a core activity to nurture Ubuntu, as each family and community member becomes useful in provide a service that helps others to flourish at different stages of life. The paper concludes that the use of the home-based early childhood model as a flourishing intervention helps to engage every member of the community for the good of their children, bringing live the Ubuntu saying “I am a person because of other persons.” This study is significant in that it proposes home-based early learning as a more viable pathway way to human flourishing and redirects the focus of flourishing to a younger age group.

Introduction

In Africa, the education of children is preferred to adult education to allow them grow into it (Nsamenang, 2004). That early education, as represented in garden metaphors reflects a gradual unfolding of social ontogenesis, human abilities, and selfhood framed as “buds of hope and expectation” (Zimba, 2002, 98), that are helped to flourish. Thus, today’s adults are a product of their childhoods (Lanyasunya and Lesolayia, 2001, 4).

Nelson Mandela, one of Africa’s most respected leaders once said “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world” (Duncan, 2013: 1). This means that African communities can use education of children as a critical pathway for uplifting themselves from their disadvantaged position so as to flourish. There are still not agreements in some African communities as to when there is the onset of flourishing in the sense of education. For example, some argue that human flourishing should be the ideal or overarching aim of education (Brighouse, 2008), others think that fruits of flourishing should determine the aim of education so as to lead to flourishing lives (Reiss and White, 2013). In either circumstance, education is paramount to flourishing.

If education is one pathway to flourishing (De Ruyter et al., 2021), then the next challenge will be when to start achieving flourishing. While some argue that human flourishing should be the ideal or overarching aim of education (Brighouse, 2008), others think that fruits of flourishing should determine the aim of education so as to lead to flourishing lives (Reiss and White, 2013). In either circumstance, education is paramount to flourishing.

Traditionally in Europe, the concept of human flourishing has always been tagged to old age where it is believed that you experience it when your life is complete (Curzer, 2012). This argument had been strengthened by earlier views that contended that children or youth who are just starting their lives cannot experience flourishing (Aristotle, 2009, p. 15, 1100). However, the more acceptable view in many African societies is that ideals of flourishing must be nurtured early in life as any interventions that are implemented ex post facto (Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2012) never yield continuous and contextual flourishing.

It has already been suggested that experiences of fruitful and rewarding careers later in life can be traced back to the skills and abilities learned during the early year (Seligman, 2011). In this case, providing flourishing interventions early helps individuals to gain necessary skills, knowledge, abilities and attitudes (Van Zyl and Rothmann, 2012) so as to uptake flourishing fruits in the short term during tertiary education and in the long term in old age (Van Zyl and Stander, 2014). From the economic perspective, interventions that aim at investing in early childhood education have been found to yield better returns of between 7 and 13 dollars for every dollar spent on it (Heckman, 2012). This argument about investing in ECCE is a better way to invest in human flourishing (Tucker, 2020).

If we now agree that we focus on early years’ education, we also need to agree that the education should be provided in the context in the communities to help children foster social relations in their environment (Cuban, 1988) and optimal development, a concept closely associated with flourishing (Narvaez et al., 2016). If that is done, we should be able to cultivate in our children values that help them to make meaningful choices about their lives so as to meet their core flourishing needs rather than trying to engineer them in adulthood to experience flourishing (Raab, 2019). Contextual education as suggested by the ecosystem model can best be actualised using hybrid models that work with both homes and pre-schools to promote child and parenting outcomes for flourishing. It should, however, be noted that not all children are benefiting from compulsory education (Moore, 2020). While it is believed that most children, especially those in underprivileged communities are more likely not to benefit from any form of education (Raab, 2017), studies show that even those from well to do families are equally not flourishing as their childhood is being suppressed by their parent’s pursuit for success (Lythcott-Haims, 2015; Pope et al., 2015).

Different models that include center-based nurseries or kindergarten, community or home-based approaches are currently being used in different parts of Africa to deliver early years’ education. However, each of them has both strong and weak points. For example, the Home-based and informal community-based models are noted to increase quality, relevance, and access and to ensure equity, particularly for the most marginalised groups. However, all of them have their own limitations. For example, the center-based nursery or kindergarten approach is unaffordable for many and is weak in developing socio-emotional outcomes (McCabe and Frede, 2007). The home-based models are also criticised for having less trained caregivers, having limited resources for children, and spending less time on cognitive development activities (Bradley and Vandell, 2007; Paulsell et al., 2010).

A flourishing child is a child who has meaningful relationships, is unburdened, in optimal development, enjoys childhood goods, experiences enjoyment and subjective happiness (Wolbert et al., 2021). This feeling of happiness for children is usually achieved during play. Different studies already recognise play as a positive emotional pathway and a vehicle for developing curiosity, learning and happiness in children (Baker et al., 2017). Through play, children are able to build appropriate character strengths (Seligman et al., 2009), a positive mindset toward life (Dweck, 2006), and resilience that are core to human flourishing. Thus, the bio-ecological model underpins the use of play-based pedagogy in home-based centres in context.

This study attempts to show an African based pathway to human flourishing using the ideals of Ubuntu as an input and an outcome. We use two theoretical underpinnings of the bio-ecological model of human development and the ecosystems model to explain the basis of the approach in nurturing and getting to the ultimate goal of flourishing. The bio-ecological model was developed from the ecological systems model now with a focus on proximal processes as engines of development pinned on four principal components of process, person, context and time (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2006). The second theoretical model is the ecosystems model developed by the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016) to help to suggest possible explorations of interrelationships of issues across the framework (Bartolo et al., 2019). The two models are used to conceptualise and develop an Afri-centric early learning model that promises to nurture Ubuntu.

The Africentric Inclusive Home-Based Early Childhood Education Model

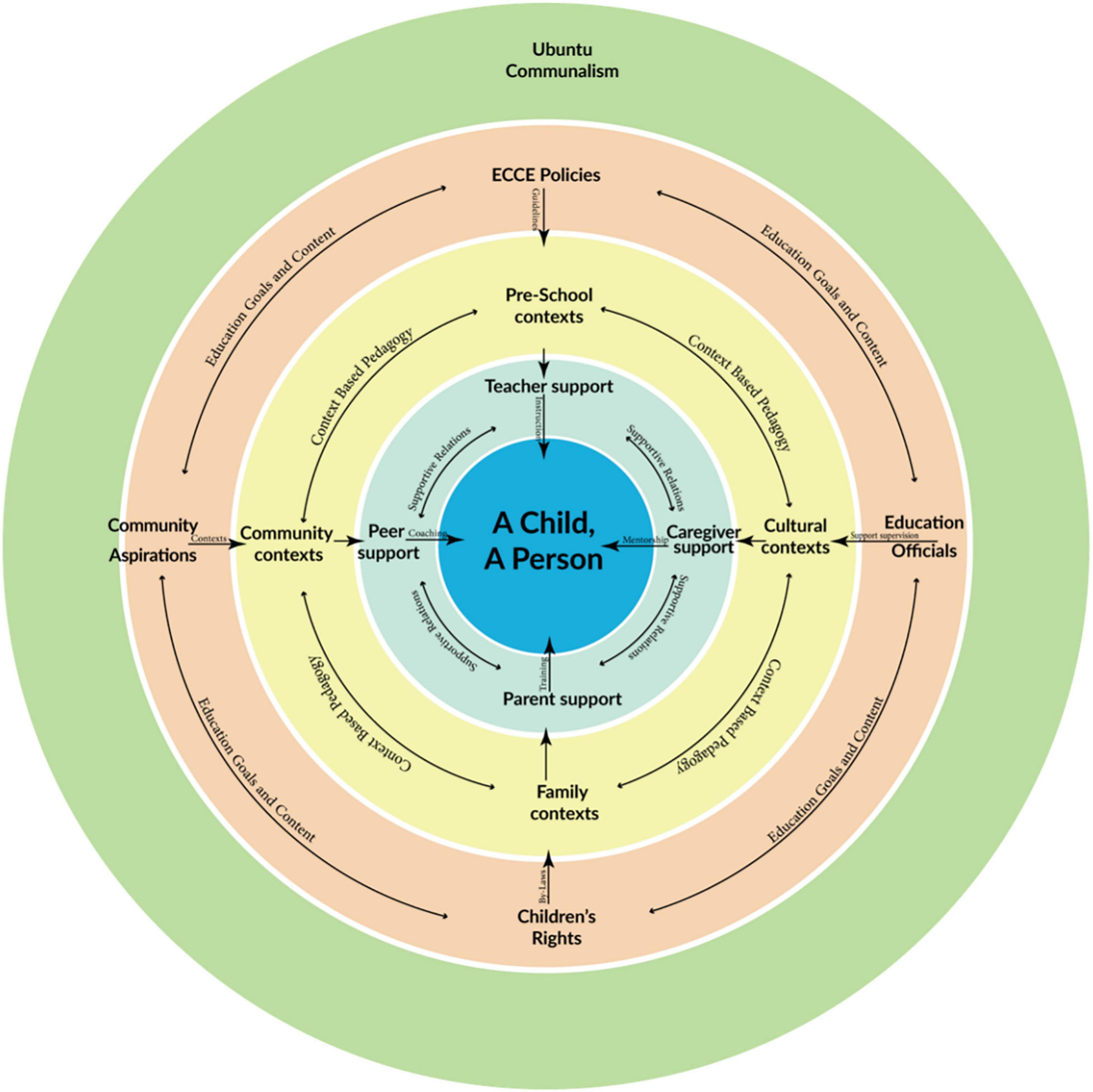

IHELP model is built on Bame Nsamenang’s Africentric theory of human ontogenesis (Nsamenang, 2006), but with lessons from the Ecosystem model of Inclusive Early Childhood Education adopted from the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016). The model adopts the five layers from the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016), however, it contextualises the layers to the outcome, strong relations, contextual environments, aspirations and finally flourishing or Ubuntu based on African contextual understanding of child-rearing and teaching in the early years as proposed by Bame’s human ontogenesis theory (Nsamenang, 2006). EANSNIES uses outcome, quality processes, supportive structures in IECE, supportive structures in communities, and supportive structures in national and regional levels (Bartolo et al., 2019), that is slightly different from the IHELP model as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Africentric inclusive home-based early childhood education model adopted and adapted from the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016).

In the first layer, the outcome is a child who has become a ‘person’ who fits well in the community of other peers. Such a child manifests social responsibility, acceptable moral and spiritual values, willingly participates in different activities, uses his/her intelligence, wisdom, and knowledge to solve personal and community challenges (Ogbu, 1994), use language appropriately, and shows respect for self and other people commensurately (Awopegba et al., 2013).

The second layer is strong relations in form of peer and sibling relations in the first place who coach the child by introducing the child to norms, language, socialisation and life skills. The next supportive structure is the parent relations that provide the child with standards, discipline, physical needs and role models. In the third place is the teacher or and caregivers who work as substitute parents to the child to mentor and instruct, but also introduce the child to other horizons beyond the local community. This is done from the lessons and experiences they introduce the child to. Sometimes the teachers and parents play double roles as counsellors and disciplinarians depending on where the child has found self in a conflict.

The next layer is the contextual layer in which the child has to work within a given context to fit in the community. In this area, the child is taught using context-based pedagogic strategies as they are offered psychosocial surveillance, coaching, nutrition and moral values (Awopegba et al., 2013). The child must learn to differentiate and act according to family, community, school or cultural contexts in a reflective manner as he/she matures to adulthood. Failure to behave in the right context will negatively affect their flourishing as they will not be able to belong to any of such environments both as children or adults. In this case, a child must act smart and act contextually as a way of showing evidence of flourishing from a very early age (Oduolowu, 2011).

The fourth layer is the larger societal goals and aspirations that must govern and drive the nature of the learning activities and focus for the ultimate good of both the children and their country. Community aspirations for their children, the early learning policies in the country, national and international child rights or protection legislation and acts guide it. These provide guidance and parameters through which communities may exercise their freedom to nurture their children.

The fifth layer is the overarching layer that shows the ultimate and the beginning point for child preparation and support. Ubuntu or in this case human flourishing is the reason why we do all that we do, with the hope that our children in turn will flourish and exhibit as an outcome the spirit and purpose of Ubuntu.

Inclusive Home-Based Early Childhood Education

Based on the Africentric philoshical conceptualisations above, we now developed a hybrid called the Inclusive Home-based Early Learning Project (IHELP) model. IHELP is a typically inexpensive model that addresses a basic and fundamental need of, specifically, though not exclusively, poor African women. These women, who, more often than not, have the sole responsibility of caring for their children and for whom, the question of securing help with childcare is difficult and in most cases, non-existent.

The model combines the centre and home-based models but is implemented in homes in marginalised communities. The model centres are located either in one of the homes in a homestead or in a central communal land space that is within reach of about 10 or more homes that have children in the early years’ age range. Using the Ubuntu spirit, the centre is managed by a group of volunteer parents who form the management committee. Parents enroll their children in the centre and contribute agreed food items for children’s meals while at the centre. Parents contribute by conducting lessons themselves, preparing meals for children, maintaining the centre play materials and doing farming as in-kind payment for the caregivers or teachers. The centres operate on a half-day basis with parents engaged in teaching children cultural content, self-help skills, play and language activities every Monday and Thursday. The hired trained teachers engage the children in literacy and numeracy activities every Tuesday and Friday. Every Wednesday is a free day for child play but monitored by parents. All children with special needs who are not able to participate during the rest of the days come to the centre to join in the play with other children on Wednesdays. On this day, special needs education experts visit the centre to observe the children with special needs and plan for them Individualised Education Plans (IEP) to be implemented in the week. The special needs experts visit identified children with challenges in the week to assess their learning needs. Those making progress are allowed to join the centre on the days when parents are in charge of learning. If they show further progress, they can come on the days when teachers are teaching literacy and numeracy. If they adjust to all the routines, then they are integrated into the centre like any other child.

This model is currently being piloted in 24 sites located in eight districts, four in Uganda, two in Kenya and Zimbabwe, respectively. It is hoped that the model will take advantage of the centre and home-based approaches while minimising their weaknesses. The model also uses the Ubuntu spirit to rally the community to contribute toward the flourishing of their children in a culturally responsive way and in turn build Ubuntu, the ultimate human flourishing.

The use of the IHELP model empowers the parents and the community to assume collective responsibility for the welfare of children. In its architectural design, it is organised to ensure a community response to childcare so that women can be freed up to take care of different needs. It also seeks to provide education and cultural enrichment by teaching children true Ubuntu culture that allows the entire village to share in the dignity of knowing that they have resumed the responsibility for the welfare of their own children. In this way, IHELP model helps to bridge the gap in the community and bring all resources together in a holistic impactful way.

Discussion

Conceptualization of flourishing seems to be grounded on Eurocentric ideals that view flourishing from an individualistic perspective (Hailey, 2008), yet the African view is always communal, as they believe in the welfare above self commonly referred to as Ubuntu (Mugumbate and Nyanguru, 2013). Both Africans and non-Africans alike have understood Ubuntu in different ways across the globe. Differences in conceptualisation arise from either direct translation of the Nguni language “Umuntu ngumuntu Ngabantu” which is “a person is a person because of others” (Moloketi, 2009:243) or the interpretation of the phrase to mean human dignity (Tutu, 2009), personhood (Banda, 2019), human virtue (Gichure, 2015) or relational to kinsmen (Mbiti, 1990).

The broader Ubuntu supports the communitarian idea, which believes that all members of a given community must participate as a moral obligation in all its activities to be gifted with genuine humanity (Shutte, 2001). Thus, Ubuntu is a broad concept that covers all aspects of community human flourishing that should be offered to all persons in the world as a gift for embracing humanity (Broodryk, 2002). In short, Ubuntu is the African version of human flourishing that demands that no matter what you have or who you are, you will only flourish if you are able to offer and maintain humane treatment of others and be better than others in being human (Banda, 2019).

The same Ubuntu can have different meanings in both narrow and broader senses. For example, Ubuntu can be understood as social justice, righteousness, care, empathy for others and respect’ (Mkhize, 2008). It can also be seen as the capacity of persons to express compassion, reciprocity, dignity, humanity and mutuality in the interests of the building and maintaining communities with justice and mutual caring (Khoza, 2006). At a personal level, Ubuntu is seen as a universal brotherhood (Khoza, 1994), fairness (Mugumbate and Nyanguru, 2013), behaving well toward others (Thompsell, 2019).

While education is generally seen as a pathway to human flourishing, a community approach to it as demonstrated in a home based early learning models supported by parents can be a more enriching approach for many. With this model, focussing on individuals cannot be called flourishing in African settings. Also, flourishing cannot be seen in the sense of being humanitarian, but in the sense of proactive behaviours that support the wellbeing of all. Many African communities face a number of life-threatening challenges, but they have always found a way of acting together in the Ubuntu spirit to overcome them. Flourishing is built on the rich cultural values and traditional practices that have for long been used to regulate and shape the social lives of the people (Gyekye, 2013). These values are passed on from one generation to another through both overt and covert educational practices that begin with early years’ education. Inclusive home-based early childhood education can be such one fulfilling experience for deprived children and communities in Africa.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

GE contributed to conceptualisation and review of the article supported by RO. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Preparation for this manuscript was made possible with generous funding from IDRC grant 109666-001 to Kyambogo University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge ISSBD professional development group members and faculty whose feedback helped to shape this manuscript.

References

Aristotle (2009). The Nicomachean Ethics, transl. D. Ross, ed. L. Brown Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Awopegba, P. O., Oduolowu, E. A., and Nsamenang, A. B. (2013). Indigenous Early Childhood Care and Education (IECCE) Curriculum Framework for Africa: A Focus on Context and Contents. Addis Ababa: UNESCO: International Institute for Capacity Building in Africa.

Baker, L., Green, S., and Falecki, D. (2017). Positive early childhood education: expanding the reach of positive psychology into early childhood. Eur. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 1:8.

Banda, C. (2019). Ubuntu as human flourishing? An African traditional religious analysis of ubuntu and its challenge to Christian anthropology. Stellenbosch Theol. J. 5, 203–228.

Bartolo, P. A., Kyriazopoulou, M., Björck-Åkesson, E., and Giné, C. (2019). An adapted ecosystem model for inclusive early childhood education: a qualitative cross European study. Int. J. Sch. Educ. Psychol. 9, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2019.1637311

Bradley, R. H., and Vandell, D. L. (2007). Child care and the well-being of children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 161, 669–676. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.669

Brighouse, H. (2008). Education for a flourishing life. Yearb. Natl. Soc. Study Educ. 107, 58–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7984.2008.00130

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2006). “The bioecological model of human development,” in Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, 6th Edn. Vol. 1, eds W. Damon and R. M. Lerner (New York, NY: Wiley), 793–828.

Cuban, L. (1988). “Constancy and change in schools (1880s to the present),” in Contributing to Educational Change: Perspectives on Research and Practice, ed. P. W. Jackson (Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publishing), 85–105.

De Ruyter, D., Oades, L., and Waghid, Y. (2021). Meaning(s) of Human Flourishing and Education a Research Brief by the International Science and Evidence Based Education Assessment. An Initiative by UNESCO MGIEP. Available online at: https://en.unesco.org/futuresofeducation/sites/default/files/2021-03/Flourishing%20and%20Education_ISEEA%20Research%20Brief.pdf (accessed August 9, 2021).

Duncan, A. (2013). Education: The Most Powerful Weapon for Changing the World. Available online at: https://blog.usaid.gov/2013/04/education-the-most-powerful-weapon/ (accessed August 9, 2021).

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2016). Inclusive Early Childhood Education: An Analysis of 32 European Examples, eds P. Bartolo, E. Björck-Åkesson, C. Giné, and M. Kyriazopoulou (Odense: European Agency).

Gichure, C. (2015). Human Nature/Identity: The Ubuntu World View and Beyond. Available online at: https://su-plus.strathmore.edu/bitstream/handle/11071/3758/Human%20nature.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed August 9, 2021).

Gyekye, K. (2013). Philosophy Culture and Vision: African Perspectives: Selected Essays. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Heckman, J. J. (2012). Invest in Early Childhood Development: Reduce Deficits, Strengthen the Economy. Available online at: https://heckmanequation.org/www/assets/2013/07/F_HeckmanDeficitPieceCUSTOM-Generic_052714-3-1.pdf (accessed August 9, 2021).

Khoza, R. J. (2006). Let Africa Lead: African Transformational Leadership for 21st Century Business. Johannesburg: Vezubuntu.

Lanyasunya, A. R., and Lesolayia, M. S. (2001). El-barta Child and Family Project. Working Papers in Early Childhood Development 28. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

Lythcott-Haims, J. (2015). How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Over Parenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Mbiti, J. S. (1990). African Religions & Philosophy, 2nd Edn. Gaborone: Heinemann Educational Botswana.

McCabe, L. A., and Frede, E. C. (2007). Challenging Behaviors and the Role of Preschool Education. NIEER Preschool Policy Brief. Available online at: https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/16.pdf (accessed August 9, 2021).

Mkhize, N. (2008). “Ubuntu and harmony: an African approach to morality and ethics,” in Persons in Community: African Ethics in a Global Culture, ed. R. Nicolson (Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press), 35–44. doi: 10.1007/s11948-021-00313-w

Moloketi, G. R. (2009). Towards a common understanding of corruption in Africa. Public Policy Adm. 24, 331–338. doi: 10.1177/0952076709103814

Moore, J. (2020). “Human flourishing and education,” in Wonder, Education, and Human Flourishing: Theoretical, Empirical, and Practical Perspectives, ed. A. Schinkel (Amsterdam: VU University Press).

Mugumbate, J., and Nyanguru, A. (2013). Exploring African philosophy: the value of Ubuntu in social work. Afr. J. Soc. Work 3, 82–100.

Narvaez, D., Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Miller-Graff, L. E., Gettler, L. T., and Hastings, P. D. (2016). Contexts for Young Child Flourishing: Evolution, Family, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nsamenang, A. B. (2004). Cultures of Human Development and Education: Challenge to Growing up African. New York, NY: Nova.

Nsamenang, A. B. (2006). Human ontogenesis: an indigenous African view on development and intelligence. Int. J. Psychol. 41, 293–297. doi: 10.1080/00207590544000077

Ogbu, J. U. (1994). “From cultural differences to differences in cultural frames of reference,” in Cross-Cultural Roots of Minority Child Development, eds P. M. Greenfield and R. R. Cocking (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum), 365–391.

Paulsell, D., Porter, T., Kirby, G., Boller, K., Martin, E. S., Burwick, A., et al. (2010). Supporting Quality in Home-Based Child Care: Initiative Design and Evaluation Options. Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research.

Pope, D., Brown, M., and Miles, S. (2015). Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy, Successful Kids, 1st Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Raab, E. L. (2017). Why School? A Systems Perspective on Creating Schooling for Flourishing Individuals and a Thriving Democratic Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Raab, E. L. (2019). Designing Schools for Human Flourishing & a Thriving Democracy. Available online at: https://erinraab.medium.com/designing-schools-for-human-flourishing-a-thriving-democracy-7db8a1eecc3b (accessed March 8, 2021).

Reiss, M. J., and White, J. (2013). An Aims-Based Curriculum. The Significance of Human Flourishing for Schools. London: Institute of Education Press.

Seligman, M., Ernst, R., Gillham, K., and Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 35, 293–311. doi: 10.1080/03054980902934563

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well–Being. New York, NY: Free Press.

Thompsell, A. (2019). Get the Definition of Ubuntu, a Nguni Word with Several Meanings. Available online at: https://www.thoughtco.com/the-meaning-of-ubuntu-43307 (accessed February 8, 2021).

Tucker, P. (2020). Early Childhood Education is an Investment in Human Flourishing. Available online at: https://www.postregister.com/opinion/guest_column/early-childhood-education-is-an-investment-in-human-flourishing/article_9311247b-9a5b-5568-9907-d047b6784fb5.html (accessed February 8, 2021).

Van Zyl, L. E., and Rothmann, S. (2012). Beyond smiling: the development and evaluation of a positive psychological intervention aimed at student happiness. J. Psychol. Afr. 22, 78–99.

Van Zyl, L. E., and Stander, M. W. (2014). “Flourishing interventions: a practical guide to student development,” in Psycho-Social Career Meta-capacities, ed. M. Coetzee (Cham: Springer). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-00645-1_14

Wolbert, L., de Ruyter, D., and Schinkel, A. (2021). The flourishing child. J. Philos. Educ. 55, 698–709.

Zimba, R. F. (2002). “Indigenous conceptions of childhood development and social realities in Southern Africa,” in Between Cultures and Biology: Perspectives on Ontogenetic Development, eds H. Keller, Y. P. Poortinga, and A. Scholmerish (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 89–115. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511489853.006

Keywords: Ubuntu, human flourishing, home-based, inclusive early learning, marginalised communities

Citation: Ejuu G and Opiyo RA (2022) Nurturing Ubuntu, the African Form of Human Flourishing Through Inclusive Home Based Early Childhood Education. Front. Educ. 7:838770. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.838770

Received: 18 December 2021; Accepted: 27 January 2022;

Published: 17 February 2022.

Edited by:

Milan Kubiatko, J. E. Purkyne University, CzechiaReviewed by:

Muhammet Usak, Kazan Federal University, RussiaCopyright © 2022 Ejuu and Opiyo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Godfrey Ejuu, Z29kZnJleWVqdXVAZ21haWwuY29t

†

Godfrey Ejuu

Godfrey Ejuu Rose Atieno Opiyo2

Rose Atieno Opiyo2