- 1Resource Development Institute, Tra Vinh University, Tra Vinh, Vietnam

- 2School of Education, Faculty of Arts and Social Science, The University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

Assessment decision-making is an integral part of teacher practice. Issues related to its trustworthiness have always been a major area of concern, particularly variability and consistency of teacher judgment. While there has been extensive research on factors affecting variability, little is understood about the cognitive processes that work to improve the trustworthiness of assessment. Even in an educational system like Australia, where teacher-based assessment in mainstream classrooms is widespread, it has only been relatively recently that there have been initiatives to enhance the trustworthiness of teacher assessment of English as a second or additional language (EAL). To date, how teachers make their decisions in assessing student oral language development has not been well studied. This paper reports on the nature and dynamics of teacher decision-making as part of a larger study aimed at exploring variability of teacher-based assessment when using the oral assessment tasks and protocols developed as part of the Victorian project, Tools to Enhance Assessment Literacy for Teachers of English as an Additional Language (TEAL). Employing a mixed-method research approach, this study investigated the assessment judgements of 12 experienced NSW primary and secondary EAL teachers through survey, assessment activity, think-aloud protocols and individual follow-up interviews. The paper highlights the key role of teachers’ first impressions, or judgement Gestalts, in forming holistic appraisals shaping subsequent assessment decision-making pathways. Based on the data, a model identifying three assessment decision-making pathways is proposed which provides a new lens for understanding differences in teachers’ final assessment judgements of student oral language performances and their relative trustworthiness. Implications of the model for assessment theory and practice, teacher education, and future research are discussed.

Introduction

Sound assessment decision-making underpins the trustworthiness of teacher-based assessment in both general and language teaching contexts. The trustworthiness of teacher-based language assessments has always been a matter of concern. Teachers’ grading decisions (McMillan and Nash, 2000), inter- and intra-rater reliability (McNamara, 1996, 2000; Gamaroff, 2000) and language performance assessment are all subject to variability (Lado, 1961; Huot, 1990; Hamp-Lyons, 1991; Janopoulos, 1993; Williamson and Huot, 1993; Weigle, 2002). Likewise, the inherent subjectivity of teacher-based assessment (McNamara, 1996, 2000) challenges the consistency (Luoma, 2004; Taylor, 2006) of teacher assessment decision-making. Moves towards assessment for learning as a trustworthy alternative to standardised testing (Stiggins, 2002; Smith, 2003; Davison, 2004, 2013; Popham, 2004, 2014; Davison and Leung, 2009) have only intensified the need to address these long-standing issues in classroom assessment (Anderson, 2003; Brookhart, 2003, 2011; McMillan, 2003; Harlen, 2005; Joughin, 2009a,b; Klenowski, 2013).

While there has been extensive research on factors affecting variability and consistency, teacher thinking processes affecting the trustworthiness of teacher-based assessment is little understood. Recent initiatives to enhance the trustworthiness of English language teacher assessment in Australia have focused on improving teachers’ assessment literacy through collective socio-technical systems of support fostering moderated assessment practices around shared tools and resources (Davison, 2008, 2019, 2021; Michell and Davison, 2020). Over the last decade or so, the trustworthiness of teacher assessment judgements has been the central concern of assessment moderation studies (Klenowski et al., 2007; Klenowski and Wyatt-Smith, 2010; Wyatt-Smith et al., 2010; Adie et al., 2012; Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2013, Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2014) as well as individual teacher assessment studies (Crisp, 2010, 2013, 2017). This research on assessment judgement invites wider consideration of the nature of human judgement (Cooksey, 1996; Laming, 2004) and its operation as part of teacher cognition (Clark and Peterson, 1984; Freeman, 2002; Borg, 2009; Kubanyiova and Feryok, 2015) and classroom practice (Yin, 2010; Allal, 2013; Glogger-Frey et al., 2018).

Research on teacher assessment judgement has highlighted fundamental categories of holistic and analytical thinking and their interaction in assessment decision-making (e.g., Thomas, 1994; Anderson, 2003; Newton, 2007; Sadler, 2009; Crisp, 2017). These modes of thinking have a long history in psychological research. Kahneman’s (2011) two modes of thinking: System 1—“fast,” automatic, intuitive impressions and System 2—“slow” conscious, effortful attention—expand our understanding of holistic and analytical judgements and their respective and complementary operation in reliable decision-making and development of trustworthy expertise. It is in this context that Gestalt theory (Wagemans et al., 2012a,b; Wertheimer, 2012; Koffka, 2013) offers further insight into the holistic, impressionistic System 1 of language assessment. Although variability in classroom language assessment is an inherent characteristic of human assessment (McNamara, 1996; Davison, 2004; Davison and Leung, 2009), an understanding of the nature and dynamics of System 1 and 2 modes of thinking can be applied to enhancing the trustworthiness of teacher language assessment judgements and decision-making “from the inside.”

In reviewing relevant research and reporting on the study findings, this paper outlines the following argument: (a) the situated cognitive processes underpinning teacher assessment practice is critical but is still underexplored; (b) such cognitive processes can be productively researched from the perspective of teacher judgement and decision-making; (c) holistic and analytical thinking and their dynamic interplay are fundamental thinking processes in how teachers form assessment judgements and decisions; (d) judgement Gestalts, conceptualised in this paper as holistic, intuitive assessment impressions, play a crucial role in teacher assessment shaping different assessment decision-making pathways; (e) a model making these assessment pathways and their contributory factors transparent can help teachers better understand their own assessment decision-making and ultimately improve the trustworthiness of teacher-based assessment and teacher assessment literacy.

Teacher Assessment Decision-Making

Assessment for Learning, the idea that assessment should be designed to promote student learning and thus be integrated with instruction (e.g., Black and Wiliam, 1998; Shepard, 2000, 2001; Stiggins, 2002; Stiggins et al., 2004; Gipps, 2012) “brings the teacher back in” (Michell and Davison, 2020) as leading agents of learning oriented assessment (Carless, 2007; Turner and Purpura, 2016). This renewed emphasis on formative, teacher-based classroom assessment has been accompanied by a paradigm shift in conceptions of assessment from assessment-as-measurement to assessment-as-judgement:

as the role of assessment in learning has moved to the foreground of our thinking about assessment, a parallel shift has occurred towards the conception of assessment as the exercise of professional judgement and away from its conceptualisation as a form of quasi-measurement (Joughin, 2009a, p. 1 original italics).

As Sadler (2009) has noted, the traditional measurement model of assessment is reflected in the quantitative language of “gauging” the “extent of” learning, while the judgement model employs the qualitative language of “evaluation,” “quality,” and “judgement”.

This shift has brought about a reconsideration of psychometric methods developed to ensure test validity and reliability and have lead to a reconception of what these standards look like in classrooms (e.g., Brookhart, 2003; Moss, 2003; Smith, 2003). Traditional standards of validity, reliability and fairness break down when applied to classroom assessment that support learning and new approaches to quality standards for assessment are required (Joughin, 2009a,b). Based on a critique that “measurement theory expects real and stable objects, not fluctuating and contested social constructs” (Knight, 2007, p. 77) of classrooms, some researchers have called for “classroometric” (Brookhart, 2003) or “edumetric” (Dochy, 2009) approaches to redesigning classroom assessment to meet the learning needs of students rather than satisfying the technical, psychometric properties of external testing. In this context, teachers’ practical, pedagogical needs are foregrounded as necessary starting points for such designs (Davison and Michell, 2014) and issues of assessment validity and reliability are being reconsidered in terms of trustworthiness (Davison, 2004, 2017; Leung, 2013; Alonzo, 2019) and teacher assessment literacy (e.g., Mertler, 2004; Popham, 2004, 2009, 2014; Taylor, 2009; Brookhart, 2011; Koh, 2011; Xu and Brown, 2016; Davison, 2017).

The move to assessment-as-judgement highlights the evaluative nature of teacher assessment decision-making. Assessment judgements are decisions about the quality of students’ work and the best course of action the teacher might take in light of these decisions (e.g., Cooksey et al., 2007). Teacher-based assessment therefore brings to the fore considerations of the nature, development and exercise of human judgement in assessment, and these considerations are central to any theorising of assessment trustworthiness and teacher assessment literacy. Evaluative and inferential judgement is the epistemic core of teacher assessment decision-making:

The act of assessment consists of appraising the quality of what students have done in response to a set task so that we can infer what students know (Sadler private communication quoted in Joughin, 2009b, p. 16, original italics)

Thus, judgement is appraisal—a decision concerning the value or quality of a performance or perceived competence which applies regardless of assessment purpose, participants or method. All judgements are, by nature, summative—even those made for formative purposes—there is no such thing as a formative judgement (Newton, 2007; Taras, 2009).

Underpinning this judgement-centred understanding of teacher assessment is the nature of teacher expertise that enables it. This expertise has been described as connoisseurship (Eisner, 1998)—a highly developed form of competence in qualitative appraisal, where “the expert is able to give a comprehensive, valid and carefully reasoned explanation for a particular appraisal, yet is unable to do so for the general case” (Sadler, 2009, p. 57, author italics). Teachers develop such expertise through extensive engagement and “reflection on action” in particular classroom events and situations. An implication of this is that models of teacher assessment decision-making that do not consider the exercise of professional judgement ignore the nature and role of language teacher cognition and epistemology (Borg, 2009; Kubanyiova and Feryok, 2015) in which teaching and assessment is grounded.

In classroom contexts, teacher assessment decision-making is a multi-step process in which teachers form judgements about the quality of student work or performance from available information and then relate these judgements as a score to a rubric, criteria, scale, standard or continuum. Sadler (1998) describes classroom assessment events as a common three stage structure of assessment judgement formation involving (1) teacher attention is drawn to student output, (2) teacher assessment of student output against some given scoring rubric and (3) teacher judgement or action decision. At each decision point in this process, different teachers tend to refer to and apply different resources to make their judgements. In assessing student task performance, teachers typically look first at student output information from different sources to gain an initial overall impression of students’ abilities (Anderson, 2003; Crisp, 2017). During this stage, teachers rarely examine assessment rubrics or rating scales.

Within this process, two key modes of judgement are identified—holistic and analytical: “holistic grading involves appraising student works as integrated entities; analytic grading requires criterion-by-criterion judgements” (Sadler, 2009, p. 49). Newton (2007) describes these two judgment modes as being on a summative-descriptive continuum where summative judgements are characterised by appraisal—a decision concerning the value or quality of a performance or perceived competence and descriptive judgements are characterised by analysis—a reflection on the nature of the performance or perceived competence (p. 158).

Holistic assessment focuses on the overall quality of student work, rather than on its separate properties, and is foregrounded in both initial and final stages of the assessment process:

In holistic, or global grading, the teacher responds to a student’s work as a whole, then directly maps its quality to a notional point on the grade scale. Although the teacher may note specific features that stand out while appraising, arriving directly at a global judgement is foremost. Reflection on that judgement gives rise to an explanation, which necessarily refers to criteria. Holistic grading is sometimes characterised as impressionistic or intuitive (Sadler, 2009, p. 46).

Holistic assessment in the form of overall teacher judgements (OTJ) were found to be both lynch-pin and Achilles’ heel of New Zealand education reform. Teachers were required to draw on and synthesise multiple sources of assessment information to make overall judgements about students’ performance against National Standards. The Standards, however, were broad multi-criteria descriptors identified by Sadler (1985) as “fuzzy” standards. The study found that teachers formed somewhat equivocal overall judgements against the standards in three ways, (1) by unsubstantiated “gut feeling,” (2) by intra-professional judgement based on a range of assessment information, and (3) by inter-professional judgement through collegial discussion (Poskitt and Mitchell, 2012).

By contrast, comparative judgements have been found to be a more reliable means of holistic assessment. Based on the insight that all judgements of quality involve comparative, tacit or explicit evaluation of assessment artefacts (Laming, 2004), comparative judgement approaches such as pair-wise comparison (Heldsinger and Humphry, 2010; McMahon and Jones, 2015) and adaptive comparative judgement (Pollitt, 2012; Bartholomew and Yoshikawa, 2018; Baniya et al., 2019; van Daal et al., 2019) have shown high levels of reliability, even when compared with assessment against pre-set criteria (Bartholomew and Yoshikawa, 2018).

Underpinning holistic or global assessment judgements are tacit, “in the head,” models of quality which teachers bring to the assessment event. These “prototypes” (Rosch (1978) or “implicit constructs” (Rea-Dickins, 2004) are internal conceptions of quality as a generalised attribute, which are mobilised as standards of comparison in the course of engagement with student assessment artefacts. These internal, construct-referenced standards have been found at work in evaluative processes during the formation of teachers’ assessment grading decisions (Crisp, 2010). Here, Crisp found that the “Cartesian gestalt model” (Cresswell, 1997) where an assessor “identifies the presence or absence of certain features and then combines these cues via a flexible process to reach a judgement of grade-worthiness” (Crisp, p. 34) best describes this judgement process of “comparing to prototypes.” In this context, mental portraits of students (Yin, 2010) may also be seen as a kind of prototype in which stored impressions about particular types of students act as a reference point for comparative judgements about students’ relative strengths and weaknesses.

As described by Sadler, the formation of final overall assessment judgements is the product of reflexive interaction between global and analytical assessment:

Experienced assessors routinely alternate between the two approaches in order to produce what they consider to be the most valid grade…. In doing this they tend to focus on the overall quality of the work, rather than on its separate qualities. Among other things, these assessors switch focus between global and specific characteristics, just as the eye switches effortlessly between foreground (which is more localised and criterion bound) and background (which is more holistic and open (Sadler, 2009, p. 57).

Similar two-way interactions involving descriptor interpretation, judgement negotiation, comparing across samples, differential attention to criteria and work samples, and implicit weighting criteria have been reported in detailed studies of teacher assessment decision-making (Klenowski et al., 2007; Wyatt-Smith et al., 2010).

A final consideration is a generalised model of how judgement-centred assessment operates in classroom situations. Wyatt-Smith and Adie (2021) draw on Sadler’s criteria classification of explicit, latent, and meta-criteria (Sadler, 1985, 2009; Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2013) to provide a realistic cyclical account of how these criteria interact during teachers’ appraisal processes. In this cyclic appraisal model, teacher analytical feature-by-feature assessment arising from stated criteria interacts with reflection on a global appraisal (emergent, latent criteria) that synthesise as an overall assessment judgement according to certain meta-criteria—the knowledge of how explicit and latent criteria can be combined. Latent criteria might include global impressions such as prototypical models of quality, student mental portraits, and teachers’ prior judgements carried forward over time. This process highlights the key role reflexive decision-making processes play in effective teaching and assessment (e.g., Clark and Peterson, 1984; Wilen et al., 2004; Good and Lavigne, 2017).

The dynamics of judgement appraisals and its centrality to teacher-based assessment has been well documented in studies on situated judgement practices in assessment moderation contexts (e.g., Klenowski et al., 2007; Wyatt-Smith et al., 2010; Adie et al., 2012; Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2013, Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2014). The notion of judgement practice however, needs broadening to better reflect the professional, epistemic and evaluative agency teachers develop through recurring classroom assessment activity. Elaborating the concept of L2 assessment praxis (Michell and Davison, 2020) as judgement praxis aptly describes the conscious and tacit tool-mediated, judgement-based assessment knowledge practices reviewed in this section.

Gestalts and Decision-Making

Gestalt Psychology

With its holistic view of human perception and action, Gestalt Theory and its concept of Gestalt offers insights into what happens inside the cognitive “back box” of language teacher assessment decision-making. Roughly translated as “configuration” (Jäkel et al., 2016, p. 3) or more accurately as “whole” or “form” (Cervillin et al., 2014, p. 514), the concept of Gestalt was first introduced to psychology in the late 1890s by a German psychologist Christian von Ehrenfels (Wagemans et al., 2012a,b). The concept was later extended as Gestalt Theory by Wertheimer (1912), who, together with Kurt Koffka and Wolfgang Kohler, founded the Berlin School of Gestalt psychology. These Gestalt psychologists investigated the psychology of visual perception with a view to understanding human mind and thought in its totality.

Koffka (1935, 2013) theorised the key Gestalt principles of perception organisation, namely, similarity—similar items tend to be viewed as a group; prägnanz (simplicity)—objects are viewed as simply as possible; proximity—items near each other tend to be categorised as a single group; continuity—perception favours alternatives that allow contours to continue with minimal changes in direction; the law of closure—the tendency of human brain to complete shapes by filling gaps in missing parts; and the law of common fate—“the tendency for elements that move together to be perceived as a unitary entity” (Wertheimer, 1923 as cited in Wagemans et al., 2012a, p. 1,181).

The primary principle behind the Gestalt laws of perception organisation is that the whole is other than the sum of its parts, meaning the whole should be viewed as the interwoven and meaningful relationship between parts, not simply as an addition of parts to make the whole (Koffka, 1922, 2013). Gestalt is “a whole by itself, not founded on any more elementary objects … and arose through dynamic physical processes in the brain” (Wagemans et al., 2012a, p. 1,175). Thus, the meaning and the behaviour of the whole is not determined by the behaviour of its parts. Rather, the intrinsic nature of the whole determines the parts (Wertheimer, 1938, 2012). This is theorised in modern Gestalt psychology as the primacy of holistic properties which cannot be perceived as individual constituents, but only by their interrelations. This means that holistic configurations dominate constituents during information processing; perceptions are constructed “top down” rather than “bottom up.” In sum, the central idea of Gestalt psychology from both traditional and modern perspectives is the dominance of the whole over its parts in perceptual processing.

Gestalt in Language Teacher Cognition

Gestalt theory therefore offers valuable insights into the holistic, impressionistic aspects of teachers’ language assessment decision-making. Gestalts may be understood as part of the sense-making (Kubanyiova and Feryok, 2015) or imagistic orienting activity (Feryok and Pryde, 2012) processes of language teacher cognition and can be equated with “situational representations” (Clarà, 2014) that develop through experience of the immediate demands of teaching activity to become the stock and store of teacher knowledge practice.

Gestalts play a key role in Korthagen’s model of teacher learning as situated cognitions:

[A Gestalt is] a dynamic and constantly changing entity, [that] encompasses the whole of a teacher’s perception of the here-and-now situation, i.e., both his or her sensory perception of the environment as well as the images, thought and feelings, needs values, and behavioural tendencies elicited by the situation (Korthagen, 2010, p. 101).

The process of Gestalt formation is the result of a multitude of everyday encounters with similar types of classrooms situations. Korthagen’s three level model of Gestalt formation from concrete experiences to schematisation to theory formation and then subsequent reduction of schema and theory elements as higher-order Gestalts highlight teaching as a Gestalt-driven activity in which Gestalts are triggered by certain classroom situations when sufficiently rich schema has been developed. In this way, Gestalts are both a key resource and driver of teacher cognition, learning and expertise available for recognition and recall to guide classroom decision-making (Klein, 1997).

Gestalt Cognition in Clinical Judgement

Teacher assessment judgement is akin to clinical judgement in the medical professions, specifically in the areas of diagnosis, therapy, communication and decision-making (Kienle and Kiene, 2011). As with teacher assessment judgements, doctors apply their connoisseurship, expertise and skills to establish

a relationship between the singular (everything the evaluator knows about a particular individual) and the general (formal and tacit professional knowledge, as well as institutional norms and rules) in order to formulate the most appropriate course of action possible (Allal, 2013, p. 22).

Gestalt cognition lies at the heart of clinical judgement. Often manifesting as a “hunch,” it enables expert practitioners to swiftly interpret situations, develop a global impression of a patient’s health status, make causality-effect judgements and decide on appropriate treatments. Gestalt-based predictive causality assessments develop over time through repeated practice, experience, knowledge and critical reflection:

Personal experience can translate into Gestalt cognition, which can be recast into the logic of tacit thought, and can eventually translate into the tacit power of scientific or artistic genius (Cervillin et al., 2014, p. 513).

Recently, there has been something of a reassessment of the value of Gestalts in clinical decision-making. The application of “evidence-based” scientific methods for evaluating clinical reasoning has not necessarily lead to better health outcomes and, unlike clinical judgement, “gold standard” cohort-based, statistics-driven, probabilistic research such as randomised controlled trials cannot determine effective treatment outcomes for individual patients (Kienle and Kiene, 2011). Gestalt cognition has been shown to enhance the effectiveness of medical practices such as physical examination, electrocardiogram analysis, imaging interpretation and difficult patient diagnoses (Cervillin et al., 2014), and, in the pandemic context, Gestalt-based clinical judgements in virtual, online consultations (Prasad, 2021).

Gestalt as Heuristic Insight

Extending Gestalt theory, Laukkonen et al. (2018, 2021) have highlighted “insight” at the heart of Gestalt cognition by drawing attention to the insight experience associated with eureka (aha!) moments and its effects on the cognitive-emotional appraisal of ideas and decision-making. Phenomenologically, these “feelings of insight” are often experienced as a sudden illumination after an extended incubation period of problem solving. Often associated with inherent confidence (Danek and Salvi, 2020), these powerful feelings “act as a heuristic signal about the quality or importance of an idea to the individual” and “play an adaptive role aiding the efficient selection of ideas appearing in awareness by signalling which ideas can be trusted, given what one knows”(p. 27).

The phrase “given what one knows,” is a major caveat since “false eurekas” can be elicited experimentally and false insights occur when an idea is consistent with one’s knowledge but inconsistent with the facts. If one’s implicit knowledge structures are invalid, then insights arising therein will also be invalid. Such Gestalts then are no guarantee of truth but are only as solid as the knowledge and expertise that lies behind it. The implication for language assessment decision-making is clear—to be established as trustworthy, such insights need to be followed by, and subject to, reflection, analysis and verification.

Materials and Methods

Research Design

This study was part of larger mixed-method study (Johnson and Christensen, 2010) on variability in teachers’ oral English language assessment decision-making. The study aimed to provide insight into this process through the following research questions.

1. What are the processes of teacher decision-making when assessing student’s oral language performances?

2. How trustworthy are teachers’ assessment judgements?

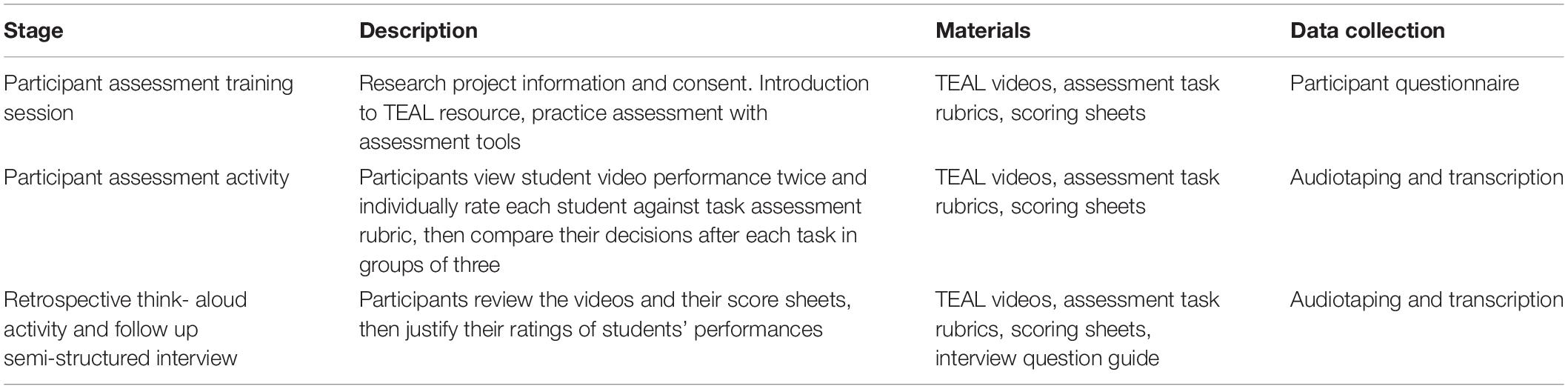

The study was conducted in three stages: (1) a participant project information, consent and assessment training session in which a questionnaire was used to collect background information from the participating teachers, (2) a teacher assessment activity in which teachers watched a set of videos of students’ performances and assigned scores to student performances and (3) a retrospective think-aloud activity and follow-up semi-structured interviews to further investigate explanations of teachers’ decisions and justifications.

The design of this qualitative study of teachers’ assessment decision-making reflects Vygotsky’s process analysis which recognises that, as “any psychological process… a process of undergoing changes right before one’s eyes” (Vygotsky and Cole, 1978, p. 61). Consequently, “the basic task of research…becomes a reconstruction of each stage in the development of the process”(p. 62) “in all its phases and changes—from birth to death …to discover its nature, its essence, for it is only in movement that a body shows what it is” (p. 65).

Participants

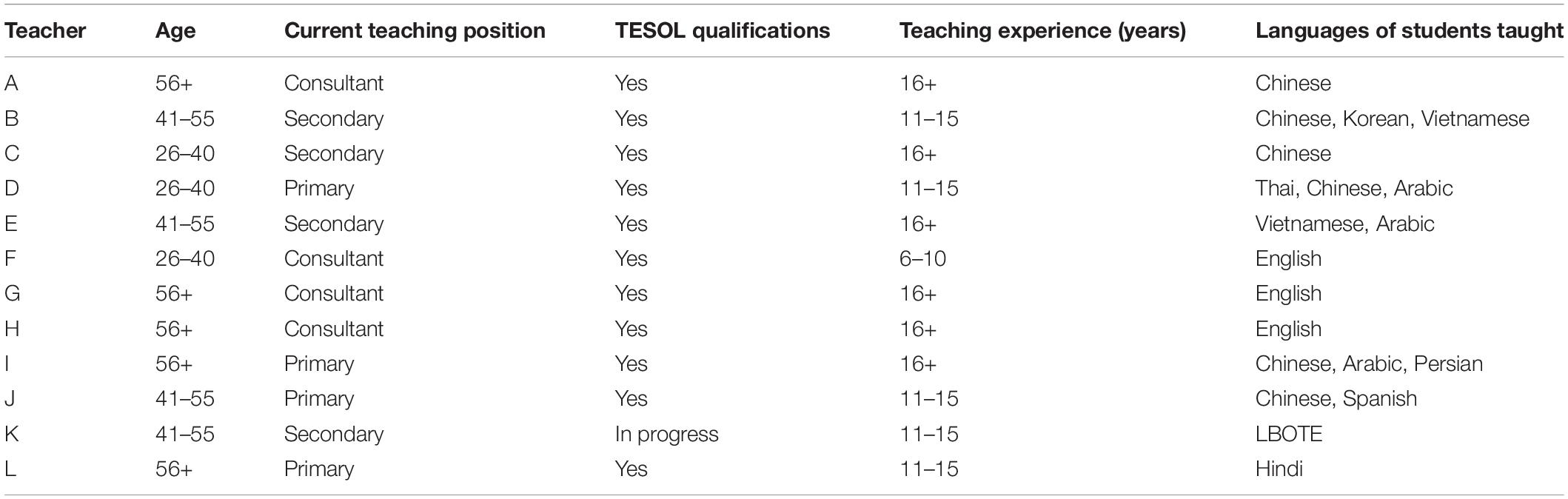

Participants were selected using convenience sampling. Currently practicing EAL/D teachers from the state professional association were invited to take part in the study. Twelve teachers took part in the full research study. Teachers were drawn from primary and secondary levels in NSW: seven from the government school sector, two from the Catholic school sector and one from the independent school sector. Background information about participants was collected from a questionnaire which was also used to obtain teachers’ consent to participate in the training workshop and the assessment activity. The results of background information questionnaire are shown in Table 1.

As shown in the table, all participants were highly experienced EAL/D teachers, with half teaching for more than 16 years, five teaching for between 11 and15 years and one teaching for between 6 and 10 years. Four participants were EAL/D consultants, who worked closely with EAL/D teachers and learners at both primary and secondary levels. Teachers had experience in teaching students from diverse language backgrounds. With one exception, all participants had TESOL qualifications in addition to their general teaching qualification. All participants were female.

Teacher-Based Assessment Activity

A teacher-based assessment activity was conducted immediately after the questionnaire administration (Table 2). The activity replicated the TEAL Project professional learning workshop design and, as the teachers did not know the students presented in the video stimulus, assessment took place “Out of Context” (Castleton et al., 2003; Wyatt-Smith et al., 2003).

Participants were asked to view three video samples of student assessment task activity and score their oral language performance against task-specific assessment rubrics. Descriptions of video samples are presented in Supplementary Appendix A. The rubric comprised an equally weighted, four-level rating scale with each level indicated by a set of criteria across four different linguistic categories—communication, cultural conventions, linguistics structures and features and strategies (Supplementary Appendix B).

After a practice run, teachers were asked to highlight the performance descriptors that matched the performance they observed in silence; then decide on students’ performance levels in a scale from 1 to 4. In addition, they could add any comments they thought would justify and support their final decisions they made against the student. Teachers were then shown the video of each student sample twice. During the first time watching the first student sample, teachers were encouraged not to refer to the criteria; however, they could use the criteria sheet the second time. Teachers’ task assessment scores are recorded in Supplementary Appendix C.

Immediately after finishing scoring for each student performance sample, teachers were asked to compare and discuss their assessment results in groups of three before they moved on to another task. Discussion focused on the two guiding questions: “Compare your responses. What was similar and what was different? Why did you have differences?”

In the next stage, after teacher assessments were examined for variability, teachers were individually followed up and were asked to justify their assessment decisions. Immediately after their oral justifications, teachers were interviewed with a view to obtaining more insight into their decision-making process.

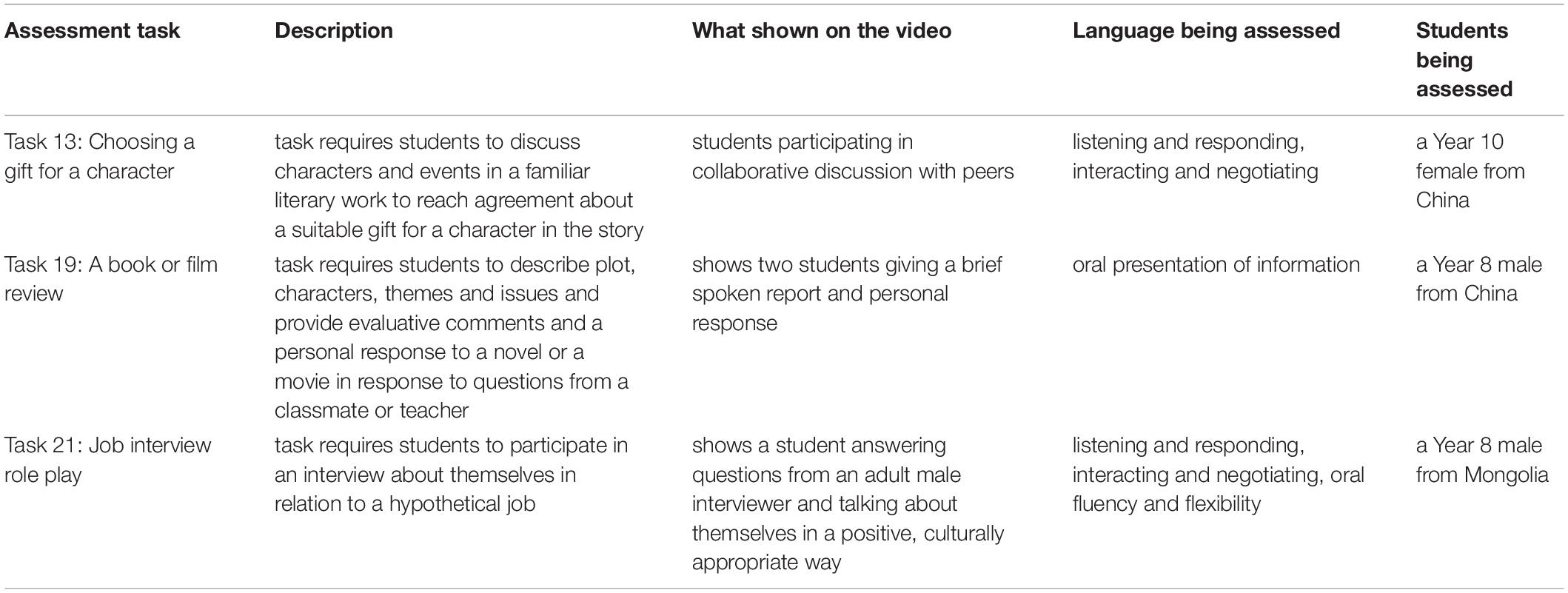

Materials

Three tasks were selected from a bank of twenty one oral assessment tasks developed for the TEAL assessment project in Victoria accessed from the project website at http://teal.global2.vic.edu.au/. These tasks were designed to assess upper primary and secondary students’ English language performances, meaning that both primary teachers and secondary teachers can suitably use these tasks to evaluate their student outputs. Detailed descriptions of the video stimulus material are summarised in Table 3.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted via a 3-h accredited professional development workshop delivered and trained by an assessment specialist. Teachers signed up for either a morning session or an afternoon session. Methods employed for data collection are outlined in the previous research design section.

Think-Aloud Protocols and Interviews

Think-aloud methods have been widely employed in studies in language assessment (e.g., Cumming, 1990, 2002; Weigle, 1998; Barkaoui, 2007). Retrospective think-aloud protocols rather than concurrent think-aloud protocols were used as the latter poses a complex and difficult multitasking challenge for teachers while the former has been reported to increase teachers’ verbalisation by reducing their cognitive load through spacing viewing and scoring activity from explaining assessment decisions (Bowers and Snyder, 1990; Van Den Haak et al., 2003).

Teachers were individually invited to complete retrospective think-aloud protocols which were implemented 1 week after the teacher-based assessment activity. During the think-aloud protocol, teachers viewed their scored criteria sheets and watched the videos of student speaking tasks again, and explained what they had thought and decided in the teacher-based assessment activity. After completing their think-aloud protocols, individual teachers were followed up in semi-structured interviews in order to obtain rich data about their assessment justifications and decision-making. An interview guide consisting of predetermined structured questions and follow-up open-ended questions was used (Supplementary Appendix D). The interview questions were divided into three major categories to cover information about teachers’ assessment confidence, processes and biases. Qualitative interviews were chosen for their value in eliciting in-depth information about social processes, and the “how” of psychological phenomena. All teacher discussion and interviews were audiotaped with the consent of the participants and later transcribed.

Data Analysis

Data from the three data sets below were analysed and triangulated with a view to identifying interaction between holistic and analytical assessment processes, the role of Gestalt-like judgements in these processes, and patterns in teachers’ assessment decision-making and their relative trustworthiness.

Analysis of Questionnaire Data

Background information collected from 12 participants through questionnaire. Responses from close-ended questions were turned into numerical data and analysed using descriptive statistics methods through the statistical computer software SPSS. The questionnaire data were then analysed in conjunction with the assessment data. Findings from these analyses were triangulated with the information obtained from the think-aloud protocols to answer the second research question.

Analysis of Teacher Assessment Scores

To analyse teacher variability and consistency, mean score calculations were conducted on teacher grade scores. Each teacher marked three student outputs using the criteria including seven assessment categories. Individual marks were taken as separate subsamples for data analysis. Teachers’ individual judgment scores in each category were therefore considered as a distinct variable with each teacher assigned 21 scores, making up 252 observations. This number of observations was large enough for the purpose of analysis. However, given this was still a fairly simple data set, all data collected from the assessment activity were manually calculated. For the purpose of calculation, data were first modified prior to primary analyses being conducted.

Analysis of Group Discussion and Interview Data

Transcriptions of the post-assessment group discussions were analysed to design the interview questions for the follow-up interviews to the retrospective think-aloud activity. Key themes and subthemes from all three sources were iteratively identified and triangulated (Miles and Huberman, 1994; Esterberg, 2002; Nunes et al., 2019). The coding scheme suggested by Cumming et al. (2002) was adopted to identify influential themes, with data coded both according to predetermined themes identified in the literature and using grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967), used mainly to untangle issues of outlier assessment behaviours. To facilitate coding and coding management, a computer program NVivo version 10 was used. Aptly for this study, researcher immersion in the data led to a gestalt of the assessment pathway model which the researcher subsequently analysed, verified and refined against the data.

Results

Qualitative Analysis of Teacher Assessment Pathways

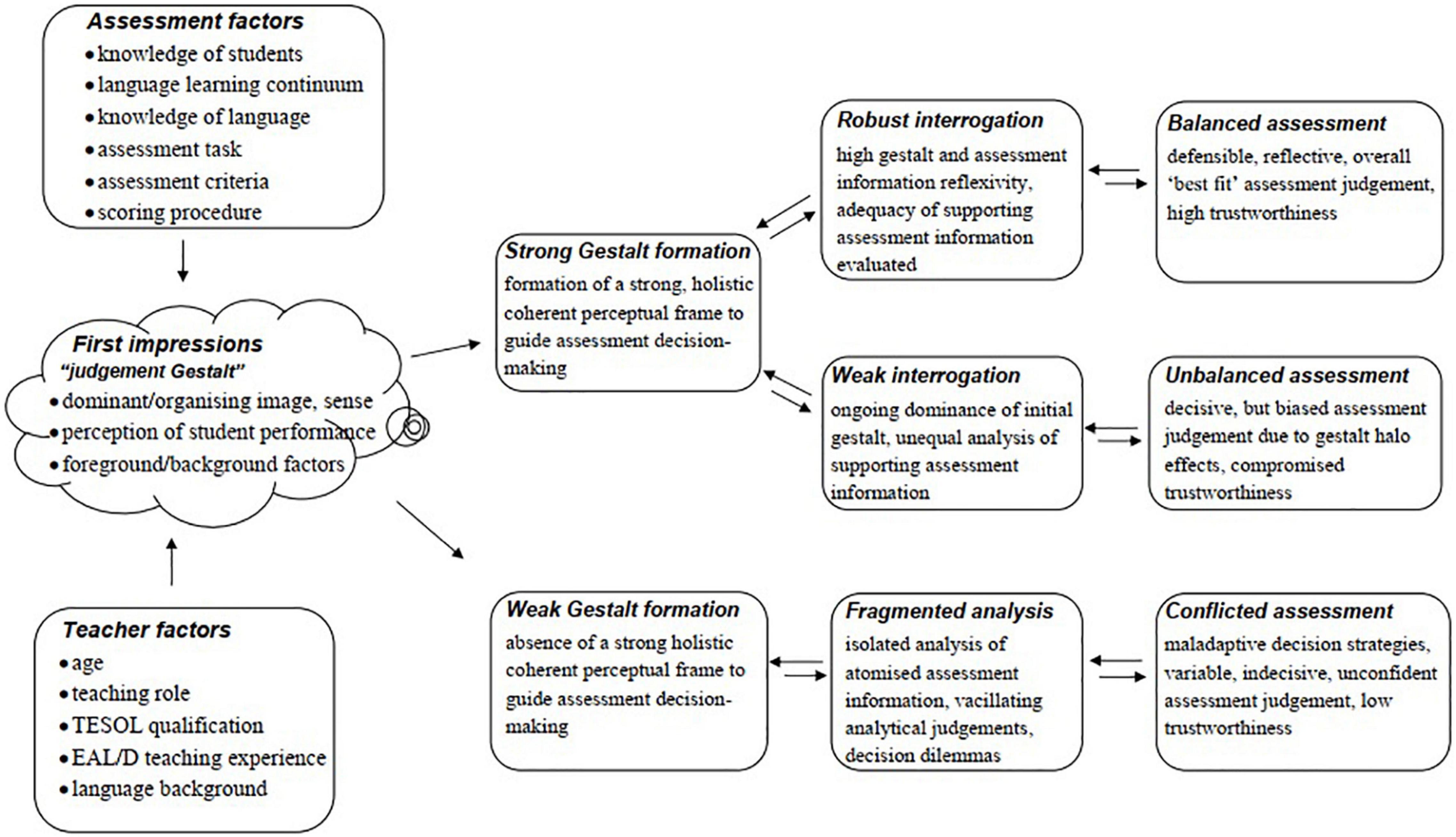

Analysis of teacher discussion, think-aloud and interview data identified the key role of teachers’ first impressions, or Gestalts, in assessing students’ oral performances. These Gestalts were found to determine the nature and trustworthiness of teachers’ final assessment judgements through one of three identifiable assessment decision-making pathways—balanced, conflicted and unbalanced. These Gestalt-based assessment pathways were further tested against the data and refined as the model of Gestalt-based language assessment decision-making shown in Figure 1.

This section presents the analysis of the verbal data from teacher discussion, think-aloud activity and interviews in each of the three assessment pathways of the model in order to show how teacher’s assessment decision-making unfolds in these pathways. From the twelve participants, three groups were identified in relation to each of the assessment pathways. Six teachers were found to have formed trustworthy, balanced assessment judgements through a strong Gestalt/high reflexivity pathway; one teacher formed unconfident conflicted assessment judgements through a weak Gestalt/low reflexivity pathway; while five teachers formed suboptimal trustworthy, unbalanced assessment judgements through a strong Gestalt/low reflexivity pathway.

Balanced Assessment Pathway

The balanced assessment pathway was identified as a highly reflexive assessment decision-making process in which teachers arrived at a trustworthy, “on balance” judgement of students’ language skills as a result of robust interrogation of their strong initial assessment Gestalt and the adequacy of related available assessment information. This assessment pathway unfolded in three stages—formation of a strong initial assessment gestalt, robust self-interrogation and a final balanced assessment judgement. Teachers C, E, F, G, K, and L were in this pathway group.

Stage 1: Formation of a strong initial assessment Gestalt

After watching the videos, teachers in the balanced assessment pathway group reported that they formed clear impressions of the relative strengths and weaknesses in the talk of the three students being assessed. Certain features of each of the students’ talk stood out and gave them an immediate and generalised sense of where students might be placed on the task assessment performance levels. Teacher’s first impressions were thus triggered and formed by students’ individual and comparative language performances and continued to influence subsequent assessment decision-making.

For example, Teacher C reported her initial impression of Student 1 was that “her oral language was clunky and … forced.” She was impressed nevertheless, with the student’s understanding of the content, noting: “she developed really good ideas.” Her clear impressions of Student 2 were formed in the context of comparison with Student 1:

He had a really sophisticated sort of grasp of informal English. You know, he spoke confidently, he was using it really well, he wasn’t looking … whereas, yeah, the girl was really clunky, as opposed to [Student 2].

As with other teachers in this group, Teacher C found that Student 2’s communication and interpersonal skills had a positive impact on her. Like the other teachers, her first impression about the third student was an overwhelmingly positive one of oral fluency:

He’s mastered the pronunciation, the American pronunciation really well. So, if I saw him I’d go yeah, automatically, he’s fine for entry, his oral language is fine.

Teacher E’s first impressions went beyond Student 1’s apparent disfluency. She was impressed by the way the student took part in the conversation (e.g., starting and maintaining the conversation):

Because it’s also easy to be distracted by the negatives, but the detail I think, and her case, she didn’t leap into it. You could see that as a negative but actually I could see that she was just thinking things through carefully before she spoke.

Student 2’s communication and interpersonal skills also impressed her and elicited a high score. She rated Student 3 as quite a competent speaker:

He is obviously quite articulate and his grammatical features I thought were quite good and his text structure is quite high. I thought he would come out on top.

By contrast, when talking about her first impressions, Teacher K, focused on what she thought were salient aspects of Student 1’s personality:

I just liked her assertiveness but that could be … because I just appreciated the fact that even though she is lacking a little bit of, I guess fluency with her spoken text, she really put herself out there and she butted in a bit. I liked that.

She got the conversation going. It would have come to proactivity. So, I thought she was very proactive.

She also indicated that she was impressed with Student 2’s pragmatic approach which she thought “was a major strength for him,” adding that she felt he was very good at engaging his counterpart and eliciting details from his partner. Like the other teachers, she was impressed by his communication and conversation skills compared with Student 1:

He did it in a friendly way. He didn’t do it in the same way as the first student. He was really good at keeping the conversation going, the dialogue going.

From these representative accounts, it is evident that the teachers quickly formed strong holistic appraisals of students’ speaking skills from their comparative viewing of students’ oral language performances. Triggered by observed language features that teachers considered to be salient, these judgement Gestalts arose as unified configurations of inseparable elements of language features, assessment task performances, student intentionality and agency and inferred or imputed personality characteristics. Formed without reference to any pre-specified criteria, they were frequently described by the teachers in terms of their immediate impact, most commonly as “being impressed.”

Stage 2: Robust interrogation of initial assessment Gestalt and supporting evidence

In this stage, teachers interrogated their initial judgement Gestalts of student performances as well as the information gained from analysing the task assessment rubric or from further reflection on student observed language performance. This stage marked the shift from, and interaction between, the “fast” thinking of Gestalt appraisals and the “slow” thinking of rubric analysis.

The additional time needed for analytical consideration of assessment rubrics is prominent in Teacher C’s response. She commented that the student dialogue gave her time to read through and reflect on the criteria while the non-assessed students were speaking, “The fact that it was dialogue was quite good because it forced you to also reflect back on what you had ticked and things like that.” She added if the dialogue was shorter, “1 min or even 30 s,” she may have been forced to make an inaccurate assessment.

This move to analytical thinking around the task assessment rubrics allowed interrogation of and reflection on teacher’s initial assessment Gestalts. Teacher E thought she could not rely solely on her positive first impressions of the two students to judge how well they were performing their task but would “have to stick on the indicators” in the assessment rubric. Teacher F expressed a similar view, reiterating that even though her initial impressions suggested the students were positive, she could not provide an accurate score without using appropriate assessment criteria:

… first impressions may be good, because I may have … unconsciously I have criteria set in my mind. I go, “oh that’s good.” But when I look at the assessment criteria, the assessing criteria I know I need to follow this standard.

A key outcome of this interaction between Gestalt- and rubric-mediated judgements was the verification of the teachers’ initial judgement Gestalts and a confident grading decision. Teacher L reported:

But then, when I see the criteria, you know, this specifies where they are at. Because when I look at them, it’s just general. I can’t find where do I need to assess them. And then when I see this, “oh this is where they should go.”

Similarly, Teacher K’s analysis of the assessment criteria confirmed her first impressions of Student 3 “as more fluent and more experience[d] in the use of English.”

I still relied upon the criteria. I was really pleased when I started doing it that it was quite accurate in its format. That it came up, based on my note-taking it came up at a higher level than the other students. I was quite thrilled about that and I thought this is actually quite a helpful tool.

From these accounts, it is clear that the teachers placed great value on using assessment rubrics as aides to reflect on their initial assessment Gestalts and ensure accurate and reliable language assessment. The stage highlights the extra time needed for “slow” analytical engagement with assessment criteria in contrast to the “fast” immediacy of judgement Gestalts. Teachers’ initial Gestalts did not disappear, however, but remained as coherent organising frames guiding assessment decision-making.

Stage 3: Further reflection on supporting evidence and balanced assessment

In this final stage, teachers form an “on balance” assessment judgement from the interaction between, and interrogations of, their assessment Gestalt and rubric-mediated assessment information. This stage is characterised by high reflexivity motivating teachers to interrogate the relevance and adequacy of existing information and seek out additional “missing” evidence that enables them to form a sound, confident overall judgement of students’ language skills.

Teacher C’s comments on deciding on Student 1’s task performance level reflects high level awareness of the common mistakes teachers make when assessing students’ oral performance. This awareness impels her, not only to interrogate available information, but also to seek out and weight further necessary evidence about student’s real language abilities.

As teachers, when you’re assessing students, you’ve got to be mindful of how … because we do get fooled by students who talk the talk really confidently and things like that. Whereas the little girl [S1] her expression was not so great, but she had some really good ideas, she had some really good understanding of the text. So, I think you’ve got to be really careful, and if you’re assessing for understanding you’ve got to make sure that that is weighted more and that teachers can see that.

Similarly, Teacher E was aware that an overall assessment judgement needed to take account of student performance at different levels across different skill areas. Despite Student 1’s strategic competence, enthusiasm and engaging conversation, she required further information to form a comprehensive overall judgement of the student’s oral language ability:

It helped to inform that first communication because it was an overall judgement about the type of communication skills she had, but I don’t think it affected the other aspects in terms of her strategic competence because I knew I had to look for other features.

Her reflexivity was also evident in deciding on Student 2’s performance level. Although Student 2’s communication and interpersonal skills impressed her and suggested a high rating, she was prepared to look beyond surface-level phenomena:

You have to step back and listen to the content and actually he didn’t have a lot of content although he did have some good vocabulary, so … but his grammatical features he had some grammatical inaccuracies which were easy to overlook because of his fluency.

The balanced assessment judgements achieved by the teachers in this group was an outcome of holistic and analytical assessment appraisals which were both subject to robust interrogation, including considerations of necessary supplementary evidence. This process of sustained meta-reflection made possible confident and trustworthy overall teacher assessments of students’ language skills.

Conflicted Assessment Pathway

The conflicted assessment pathway was identified as a decision-making process in which the teacher was unable to make an “on balance assessment” of students’ oral language skills due to a weakly formed assessment Gestalt and a resulting fragmented analysis of isolated language elements from the task assessment rubric. The conflicted nature of the assessment was evident in the teacher’s “torn” vacillation between equally weighted analytic elements of the students’ performance and her lack of confidence in her final assessment judgement. This assessment pathway unfolded in three stages—a weakly formed initial assessment Gestalt, fragmented analysis and a final conflicted assessment judgement. Only one teacher, Teacher D, was found in this assessment pathway.

Stage 1: Weak formation of initial assessment Gestalt

Like the teachers in the balanced assessment pathway, this teacher observed the relative strengths and weaknesses of students’ oral language performances. Unlike these teachers, however, she did not form an overall perceptual frame that could provide a central, coherent reference point for judging students’ oral language skills.

This weak Gestalt is indicated by her “split,” indecisive appraisals of Student 1. On the one hand, her responses during the group conversation were “rather structured, formulaic and stilted,” but, on the other hand, she “accurately uses formulaic structures to indicate turn taking.” Further, the initial impressions gained from comparing the oral language skills of Students 2 and 3 were somewhat superficial and were not interrogated

He (Student 2) was definitely better than the first one (Student 1). And a lot of that had to do with the spontaneity and colloquialisms that he had.

He (Student 3) was self-correcting as well which was very good. They all did a bit. And it also helped that he’s developed a bit of an accent as well that is a native like [sic] accent. It sounded quite American.

Stage 2: Fragmented analytical assessment

As with the previous teachers in this stage of the assessment pathway, Teacher D shifted her attention to the task assessment rubric. However, the conflict between her initial (superficial) impressions and assessment criteria soon became apparent:

Like I said before, for instance, that last student, well the second student, he was just so funny, and because he’s so confident … then the criteria grounds you.

The absence of a strong guiding assessment Gestalt led to atomised analytical assessment characterised by a criteria-by-criteria examination of the language descriptors on the task assessment rubric and rating decisions without reference to an overall appraisal:

You start looking at, what about their verb endings, are they using modal verbs, are they just using formulaic language. I think that is very important to come down.

Similarly, students’ “borderline” performances are resolved without reference to holistic appraisals, “if I had to give the students a one to four, they’d all probably be a bit higher.”

When asked whether her first impressions influenced her assessment decision-making, teacher D was uncertain and non-specific, “Yes, well, quite a bit I think.” Her further reflections on this issue were similarly non-specific:

I think, as a reflective teacher, that I would have to be a bit dishonest to say that I do not have biases. And maybe they’re not conscious, but I think everybody does.

In the absence of a strong overall guiding assessment Gestalt, Teacher D’s assessment becomes little more than atomised “criteria compliance” (Wyatt-Smith and Klenowski, 2013) where equally weighted descriptors foster conflicted and vacillating assessment decision-making.

Stage 3: Conflicted assessment judgement

In the absence of a strong guiding assessment Gestalt, Teacher D resorts to contradictory or inconsistent decision-making strategies and final indecision, when pushed.

For example, when grading Student 1’s performance, she decided that this student was halfway between a level two and three: “If I can’t decide I should always assess them down.” This strategy was contrary to what she had said earlier when she indicated that she would give higher scores for students on the borderline. However, in the end, she applied her own “middle halfway” decision-making strategy:

That’s how I reached that decision … I went “Okay, she’s halfway in-between so I’ll go for two.

When assessing Student 2’s performance, she was torn between giving a global rating of student language competence based on her initial comparison with the previous student, and her reading of the assessment criteria. Although she felt the student was very confident and she wanted to rate him at level four, “in the end I felt that I couldn’t, based on the criteria.” Similarly, when deciding on Student 3’s performance on one of the language skill areas, she could not arrive at a final overall assessment judgement:

I couldn’t decide … I gave him two and then I changed it back to a three and I couldn’t really decide for that one. And that probably dragged him down a little bit as well. I think if I’d been confident that that was a level three, then maybe I could have pushed him up a bit more.

In this final stage of the conflicted assessment pathway, then, Teacher D’s uncertainty and indecision fostered maladaptive decision-making strategies which undermined the confidence and trustworthiness of her final assessment judgements.

Unbalanced Assessment Pathway

The unbalanced assessment pathway was identified as an assessment decision-making process in which teachers were unable to make an “on balance assessment” judgement due to inadequate interrogation of a strong initial assessment Gestalt. This pathway resulted in decisive but unbalanced assessment judgements with sub-optimal trustworthiness due to halo effects associated with the persistent strength of the initial Gestalt. This assessment pathway unfolded in three stages—formation of a strong initial assessment Gestalt, weak self-interrogation and a final unbalanced assessment judgement. Five participants, Teachers A, B, H, I, and J were in this pathway group.

Stage 1: Formation of a strong initial assessment Gestalt

As with the previous two decision-making pathways, teachers’ first impressions of students’ oral communication skills were formed from viewings of their task performances. In this pathway, teachers’ initial assessment Gestalts were associated with perceived aspects of students’ personalities related to their language performance:

At first she was very confident. She presented a very diligent student who’d really gone over the material. She’s obviously familiar with that. Her articulation, you know she opened her mouth and articulated (Teacher A about Student 1).

With the girl, I was impressed at how she did throw a bit of insight into the ideas of the film. It wasn’t just a black and white … she was able to counteract. I thought that was really good. She was clever, I thought (Teacher B about Student 1).

[he] was a very skilled communicator. and very engaging and, you know, he’s got a lot of personality, very interested in people. He was very observant, he’s watching the person he’s communicating with and reading memos (Teacher A about Student 2).

Task salient aspects of students’ personalities are foregrounded and teachers’ attention is drawn to the way students take charge of, lead or sustain the group conversation:

When you look at the first group, the three students sitting there together, one thing I did like [was] how the girl held the conversation … So, I think that would influence me in terms—even though I know we’re probably meant to assess language skills, but I think she was very good, and that’s why I would be more influenced for her (Teacher B).

She clearly knows how to interact in a discussion. So, her strengths are that she knows what an oral discussion is all about (Teacher H about Student 1).

She was the type of student who would take a leadership role in any group work (Teacher I about Student 1).

He’s confident. He appropriately avoids negotiating and communicating. I think it’s quite clever. I’d do the same thing. I have a very sustained conversation (Teacher H about Student 3).

Teacher I believed that she might score Student 1 higher because “she seemed to take charge and seemed to be very competent.” Teacher H found that Student 2 had “an engaging personality in an oral discussion” and that what this student really needed was vocabulary to be “a very articulate, engaging speaker.”

Conversely, Teacher B’s first impression of Student 3’s job interview performance was affected by the student’s lack of interaction and engagement, “he was a little boring in his responses.” Consequently, she focused on his drawbacks such as “his pronunciation of words by default.” As seen in the other assessment pathways, these Gestalts were stimulated by a comparative assessment of students’ strengths and weaknesses:

One of his strengths was in the way he spoke. He did sound colloquial, but because it wasn’t too formal, and I think that’s how your attention [was] a bit with his conversation, [not] with the girl (Teacher B about Students 2 and 1).

The girl had good answers. She knew what she was talking about. She had a lot of knowledge about the characters. More so than what he had … but he displayed more confidence in the way he was speaking than the girl. She sat quite still, whereas he was leaning all over, which I think is a street, smart kind of kid. He didn’t have the formality in the same way as the girl did, but that could be part of his personality as well, because people have different kinds of personalities (Teacher B).

I know you’re not meant to compare students. You’re not meant to compare, but it is really hard not to (Teacher B).

While the origin, formation and nature of teachers’ assessment Gestalts parallel those in the balanced assessment pathway, what is noticeable in this pathway is their relative strength and power associated with perceived student personality traits. This strength persists throughout the next two stages and overwhelms and sidelines any robust interrogation required to form balanced assessment judgements.

Stages 2 and 3: Gestalt dominance, weak interrogation and unbalanced assessment judgement

These stages are characterised by the continuing dominance of teachers’ initial Gestalts with weak, unequal interrogation of those Gestalts and related assessment rubric information. Teachers’ first impressions of students’ performances remain unchanged and persist as the dominant influence on their final assessment judgements. This Gestalt dominance is particularly evident in teachers’ recognition of the continuing influence of their first impressions on their assessment thinking.

Gestalt dominance can be seen in the persistence of Teacher B’s first impressions of Student 1 and their acknowledged influence on her final assessment decision even after considering other students’ performances:

When you look at the first group, the three students sitting there together, one thing I did like [was] how the girl held the conversation … So, I think that would influence me in terms—even though I know we’re probably meant to assess language skills, but I think she was very good, and that’s why I would be more influenced for her.

Teacher I’s account highlights how holistic assessment judgements ultimately override or sideline analytical ones during grading decisions. After viewing Student 1’s performance a second time, the teacher noticed that she had not realised or had ignored grammatical issues in his performance on the day “because she was providing so much information and doing it reasonably articulately.” Nevertheless, her overwhelming impression that Student 1 “seemed to take charge and seemed to be very confident” in the conversation dominated and led her to believe that she might have given the student a higher score.

Similarly, her initial positive impressions of Student 2’s performance persisted unchanged, despite noticing his limited talk time and several speech problems:

He had a whole lot of the non-verbal[s] and his … he was the perfect talk show host. … and he had a lot of the … even the gestures and the … and the demeanour of a talk show host in talking into an interview … into an interview guest.

Remaining front-of-mind, the student’s overall communication and conversation ability “would have influenced me, then.” On further analysis, she identified several weak points in the student’s talk but did not mark him down, but instead gave him “a relatively high score,” weakly justifying, “I might have been feeling very generous that afternoon.”

In this assessment pathway, then, teachers’ first impressions about students’ oral language performances play the decisive role in forming their final assessment judgements. These assessment judgements were unbalanced because teachers’ reflexivity was not adequate or equal to the task of interrogating a dominant assessment Gestalt or related assessment evidence. As a result, trustworthiness of final assessment judgements is compromised by “halo effect” biases chiefly associated with student personality factors.

Quantitative Analysis of Teacher Assessment Variability and Consistency

Quantitative analysis of teacher assessment variability and consistency was undertaken to complement and check the qualitative findings of the study. The relative trustworthiness suggested by each of the teacher assessment pathways was specifically investigated through quantitative analysis of teacher assessment variability and consistency. Here, trustworthy assessment processes are identified as those that produce consistent results, when administered in similar circumstances, at different times and by different raters. It was found that quantitative analysis for both teacher assessment variability and consistency confirmed the relative trustworthiness of each of the teacher assessment pathways suggested in the qualitative analysis.

Variability

Assessment variability is measured by the degree of difference between the mean score and the observed score and the mean scores are different for each student. This means that the variable behaviour of that teacher was stable at different times, tasks and students and, thus, predictable.

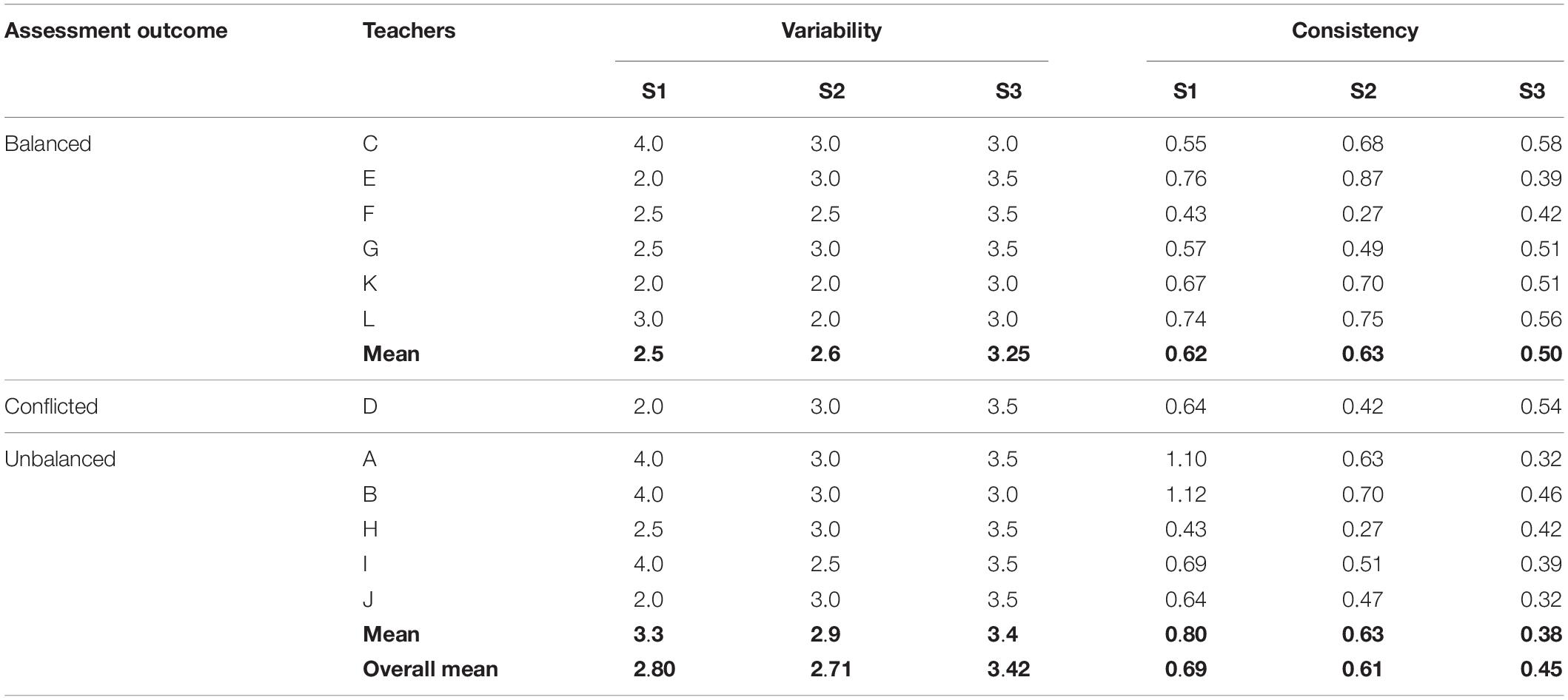

Table 4 shows the variations in comparative means of actual scores assigned by each teacher for the performance of each of the three students according to balanced, conflicted and unbalanced assessment outcomes.

In relation to assessment of Student 1’s performance, teachers who produced unbalanced assessment judgements were found to give this student the lowest scores. The mean of actual scores by this group was 3.3, compared to the overall variability mean of 2.8. On the other hand, teachers who produced balanced assessment judgements assigned the highest scores to this student with a mean score of 2.5. The teacher producing conflicted assessment judgements tended to show most variation in her score for this student. Her assessment was significantly lower than the overall mean score at 2.0, indicating she gave the lowest score to this student.

In relation to assessment of Student 2’s performance, teachers with balanced assessment judgements showed the least variation overall and gave more reliable scores than those in the other two groups, with the mean score at 2.6 compared to the overall mean score of 2.71. The conflicted assessment judgement teacher gave the lowest score at 3.5, meaning that her assessment for this student showed the widest variations. Assessments by teachers with unbalanced assessment judgements were a fraction higher than the overall mean score, 2.9 compared to 2.71, indicating that their assessment of this student was slightly harsh.

In relation to Student 3, teachers in unbalanced assessment group were found to give the most reliable score. Their mean score of 3.4 against the overall mean score of 3.42 indicated that their assessment had the least variation. Giving a slightly higher score than the overall mean score, 3.5 compared to 3.42, the teacher with conflicted assessment judgement was slightly more generous than the other assessor groups. Conversely, the mean score of teachers with balanced assessment judgements was the lowest at 3.25, meaning that their scoring for this student was comparatively stricter.

To sum up, in relation to assessment variability for individual student performances, teachers from the balanced assessment group were generally more reliable language assessors than those from the conflicted and unbalanced assessment groups. Further, certain patterns in assessment rigor were identified from the cross-student assessments of teachers in the conflicted and unbalanced assessment groups. While the conflicted assessment teacher tended to be increasingly generous in her assessments, the unbalanced assessment group’s assessments fluctuated across students but always remained above the overall mean score.

Consistency

While variability indicates whether teacher assessments are “hard” or “soft,” consistency describes the degree of agreement i.e., accurate and stable assessment, that a teacher achieves over different times or in different conditions (Luoma, 2004; Taylor, 2006). Ideally, it is expected that teachers score student performances in the same way. A student should receive a consistent score no matter how many teachers are involved in assessing their performance. By receiving consistent scoring from different teachers, students’ ability in a task is fairly reflected and the result can be relied on for fulfilling the purpose of the assessment task.

Consistency is measured by the degree of difference between the mean score and the actual scores assigned by teachers—the smaller the difference, the more reliable the assessment. Consistency for individual students is indicated by the extent to which an observed score given by a teacher to a student is close to the mean score. Consistency across students is indicated by the extent to which an observed score by a teacher is close to the mean score consistently across students. Table 4 shows differences in assessment consistency between teachers in the three assessment pathway groups.

In relation to S1’s performance, teachers producing unbalanced assessment judgements tended to have the least consistent assessments, followed by the conflicted assessment teacher and teachers in the balanced assessment group. For example, the difference between the unbalanced assessment group’s average assigned score for Student 1’s performance and the overall mean score by all 12 teachers was 0.80, followed by 0.64 and 0.62 for the conflicted and balanced assessment teachers, respectively. Thus, teachers producing balanced assessment judgements assigned the most consistent scores for this student’s oral output.

For S2’s performance, the conflicted assessment teacher produced the most consistent assessment with a difference of 0.42 between her score and the mean score. Teachers producing conflicted and unbalanced assessment judgements showed the same degree of consistency in their assessments of S2’s performance, namely 0.63.

A different situation was observed among the three groups regarding consistency in assessing S3’s oral output. Here, the unbalanced assessment teachers were found to make the most consistent assessments at 0.38, while those from balanced and conflicted assessment groups followed at 0.50 and 0.54, respectively. Overall, the unbalanced and balanced assessment teachers were the most consistent in their cross-student assessments, with the conflicted assessment teacher with the least consistent assessment.

It is also worth examining the internal consistency within groups for patterns of consistency. As can be seen from Table 4, the degree of assessment consistency of the unbalanced assessment group tended to improve each time after they assessed a student. Thus, their consistency for Student 1 was 0.80, which then reduced to 0.63 and 0.38 for Students 2 and 3 respectively. The balanced assessment group, despite having the same degree of overall consistency across students, demonstrated slight variations among students. Their degree of consistency was initially 0.62 for Student 1, then rose to 0.63 for Student 2 before dropping to 0.50 for Student 3. The pattern of consistency of the conflicted assessment teacher was the most unstable and unpredictable with fluctuations at 0.64, 0.42 and 0.54 for Students 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Reviewing groups’ assessment consistency, the teachers in the unbalanced assessment group were one of the two most consistent assessors and their consistency significantly improved across student assessments. The balanced assessment group teachers were more stable in their consistent score assignments, while the conflicted assessment teacher produced the least consistent and most unstable assessments across students.

These results suggest that assessment judgements made by teachers in the conflicted and unbalanced assessment groups are not as reliable as those made by the teachers in the balanced assessment group.

Discussion

Understanding Language Teacher Assessment Decision-Making

This study has aimed “to grasp the process in flight” (Vygotsky and Cole, 1978, p. 68) of teachers’ assessment decision-making of students’ oral English language skills in the Australian context. The major finding of the study is the identification and confirmation of a three-stage pathway model of teacher language assessment decision-making in which varying strengths of holistic and analytical assessment processes interact to produce one of three final assessment judgement outcomes—balanced, unbalanced or conflicted.

Central to this assessment process is the pivotal role of teacher’s first impressions, their judgement Gestalts, that are triggered by initial observations and comparisons of students’ language performances. Such Gestalts give a name to the impressionistic, holistic judgements that have received attention in language assessment research (Vaughan, 1991; Mitchell, 1996; Tyndall and Kenyon, 1996; Carr, 2000) as well as in clinical decision-making and other decision-making contexts (Kienle and Kiene, 2011; Cervillin et al., 2014; Danek and Salvi, 2020; Laukkonen et al., 2021) and equate to reported “configurational models of judgement” which are made directly and then checked against specific criteria (Crisp, 2017, p. 35). The findings also confirm the importance of comparative appraisals (Laming, 2004; Heldsinger and Humphry, 2010; Pollitt, 2012; Bartholomew and Yoshikawa, 2018) which naturally arise from serial viewing of student performances and trigger initial judgement Gestalts.

We have seen that how teachers respond to their assessment Gestalt determines the nature and trustworthiness of their final assessment judgement. When teachers engage in robust analysis of task-based assessment criteria to interrogate strong initial “gut feelings,” a meta-criterial reframing occurs between holistic and analytical appraisals which enables teachers to arrive at an overall, “on balance” judgement synthesis. When teachers fail to robustly interrogate strong initial Gestalts, it continues as the dominant frame overwhelming analytical processes and results in unbalanced assessment judgements. When teachers engage in fragmented analysis of isolated task criteria in the absence of strong guiding Gestalt, then indecision and conflicted assessment ensues.

These two-way interactions between holistic and analytical judgements highlight the critical role teacher reflexivity and meta-reflection play in sound assessment decision-making. “On balance” judgements may be seen as a “best fit” appraisal with given assessment information (Klenowski et al., 2009, p. 12; Poskitt and Mitchell, 2012, p. 66) characteristic of abductive reasoning (Fischer, 2001). This decision-making synthesis draws on teachers’ latent assessment experiences as well as criterion-related assessment information arising from assessment tool engagement, and reflects their meta-criterial interpretations of “the spirit” of assessment rubrics rather than “feature by feature” compliance according to “the letter” (Marshall and Drummond, 2006).

Allied to this process is the perceived “sufficiency of information” (Smith, 2003) which assessors feel they need in order to make sound decisions. Where there is insufficient information about a student’s performance (as is likely in this out-of-context assessment situation), teachers naturally infer, and may even speculate on, contextual information such as student personality traits and behaviours in order to “tip the balance” towards an overall assessment judgement.

Drawing on Frawley’s (1987) meditational model of co-regulation and Brookhart’s (2016) and Andrade and Brookhart’s (2020) co-regulation model of classroom assessment, teacher assessment decision-making can be further theorised as a dialectic process of other- and object-regulation leading to self-regulation, where teachers’ final assessment judgements constitute the achievement of a reflexive self-regulated synthesis of holistic and analytical thinking processes. As shown in the meditational model in Figure 2, teacher assessment processes involve the dialectic interplay of cognitive regulation arising from perceptions of human others and assessment tool engagement to develop the metacognitive self-regulation of balanced assessment judgements. The model relates these other- object- and self-regulation processes to holistic, analytic and synthetic appraisals aligning them the concepts of latent, explicit and meta-criteria.

The model provides a clearer understanding of the dynamics of each of the assessment pathways. Balanced assessment judgements are the productive self-regulated synthesis of the holism of teachers’ assessment Gestalts and the analytics of assessment tool engagement. Unbalanced assessment judgements are the biased outcome of teachers’ dominant and insufficiently interrogated assessment Gestalts. Conflicted assessment judgements are the unstable outcome of the unresolved decision-making dilemmas between atomised assessment information from their assessment tool engagement in the absence of a strong guiding assessment Gestalt.

Trustworthiness of Language Teacher Assessment Decision-Making

Teacher assessment decision-making concerns the forming of judgments about the quality of specific performance samples, mediated by assessment resources and the opportunity for teachers to make explicit and justified opinions (Klenowski et al., 2007). Trustworthy assessment has been described as a process where teachers show their disagreements, justify their opinions and arrive at a common, but not necessarily complete, consensus judgement about student performance (Davison, 2004; Davison and Leung, 2009). These notions of assessment trustworthiness are socially anchored in group moderation processes.

Central to the concept of trustworthiness in language assessment are the notions of judgement contestability, process transparency and accountability to evidence. However, these are all key qualities present, or absent in the individual dialectic decision-making processes of the three assessment pathways. These pathways show that essential elements of trustworthiness are inherent to the internal dynamics of assessment judgement formation. Balanced assessment is trustworthy assessment because it has its own internal self-regulating, self-corrective. In this context, trustworthy assessment can be understood as an internal dialectic process of reflexive co-regulation, in which teachers’ final assessment judgements represent a self-regulated decision synthesis of prior holistic and analytical appraisal processes.

The study offers a way forward in understanding and improving the trustworthiness of classroom-based language assessment through a model of how teachers form assessment decision-making judgements. The trustworthiness of unbalanced assessment decision-making is compromised because final assessment judgements are determined by teachers’ first perceptions of student performance. Because “perceptions are not reality; perceptions are filtered through the lens that we use to see reality” (Anderson, 2003, p. 145), students’ skills are “seen,” coloured and constructed through Gestalt’s all-encompassing lens. This outcome describes the power of the “halo effect” (Beckwith and Lehmann, 1975; Abikoff et al., 1993; Spear, 1996) where teachers’ judgements reflect the extra-performance characteristics of students and unconscious positive or negative biases that threaten assessment trustworthiness.

The halo effect’s influence on unbalanced assessment suggests ways it may be remedied to improve its trustworthiness. Teachers’ reliance on and confidence in their initial impressions of student performance can minimise the assessment tool engagement and language analysis teachers need to obtain confirming or countervailing information. Alternatively, teachers may engage in tool-mediated language analysis but the strength of their assessment Gestalt based in experience (Barkaoui, 2010a,c, 2011) overrides its influence. In both cases, trustworthiness will be enhanced by the practice of sustained dialogue and meta-reflection within and across the two assessment processes. This remedy is based on the recognition that the strength and quality of teacher reflexivity and interrogation is the key difference between balanced and unbalanced assessment.