95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 14 February 2022

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.819922

This article is part of the Research Topic Gender Differences and Disparities in Socialization Contexts: How Do They Matter for Healthy Relationships, Wellbeing, and Achievement-related Outcomes? View all 22 articles

Social exclusion, i.e., being kept apart from others and not being allowed to join, is a common phenomenon at school and can have severe consequences for students’ healthy development and success at school. This study examined teachers’ reactions to social exclusion among students focusing on the role of gender. Specifically, we were interested in potential effects of gender-specific socialization and social expectations linked to gender for teachers’ reactions to social exclusion among students. We used hypothetical scenarios in which a student is being excluded from a study group by other students. We focused on the gender of the teacher (as an observer of exclusion) on the one hand and on the gender of the excluded student on the other hand. In the hypothetical scenarios, we varied the gender of the excluded student by using either a typical female or male name. The study included 101 teachers from different school tracks in Germany (Mage = 36.93, SD = 9.84; 84 females, 17 males). We assessed teachers’ evaluations of the exclusion scenario and their anticipated reactions, i.e., how likely they were to intervene in such a situation and what they would specifically do. As expected, the participating teachers showed a general tendency to reject exclusion among students. This tendency was even more pronounced among female teachers compared to male teachers. Interestingly, these gender differences on the attitudinal side did not translate into differences in teachers’ behavioral intentions: for the likelihood to intervene, we did not find any differences based on the gender of the teacher. In terms of the gender of the excluded student, things were different: The gender of the excluded student did not affect teachers’ evaluations of the exclusion scenario. Yet, the gender of the excluded was relevant for participants’ behavioral intentions. Namely, teachers were less likely to intervene in the scenario if a boy was excluded. These findings are in line with considerations related to gender-specific socialization and social expectations linked to gender. Overall, the study demonstrates that gender is an important aspect in the context of social exclusion and further research should explicitly focus on how socialization and gender expectations can explain these findings.

Being socially excluded threatens the possibility of fulfilling one’s psychological needs, for instance, social belonging (Williams, 2009). Recurrent experience of social exclusion can have serious consequences for children’s health and wellbeing (Gazelle and Druhen, 2009; Sebastian et al., 2010; Fuhrmann et al., 2019; Jiang and Ngai, 2020), their emotional and social development (Gazelle and Druhen, 2009; Murray-Close and Ostrov, 2009), and even their academic achievement (Buhs et al., 2006).

As children and adolescents spend large parts of their lifetime at school, school has great importance as an environment, in that inclusion and exclusion take place. Given the strong impact of social exclusion on health, wellbeing, and achievement, schools should try to promote relatedness and to prevent exclusion among students. For this, teachers play an important role. It has been shown that teachers’ behavior in class can have a strong impact on their students’ attitudes regarding exclusion. For instance, Mulvey et al. (2021) found that students who perceived better student–teacher relationships as well as students who reported higher support by their teachers, were more likely to judge exclusion to be wrong and to expect that they would defend victims against exclusion. Additionally, teachers establish norms in class that indicate which behaviors are acceptable and which are not, including in terms of social exclusion. With their reactions to social exclusion among students, teachers transmit messages about their own attitudes regarding exclusion and might with that impact their students’ attitudes and behavior as well. Thus, it is important to investigate teachers’ reactions to social exclusion.

According to Riva and Eck (2016, p. ix), social exclusion can be defined as the “experience of being kept apart from others physically or emotionally”. This includes situations in which a person is excluded from conversations or activities by one or several other individuals (Wesselmann et al., 2016). As social exclusion among students is a common phenomenon at school, teachers often witness exclusion situations (Killen et al., 2013). Just as people in other contexts generally tend to reject unsubstantiated social exclusion (Wesselmann et al., 2013), this is also the case for teachers in schools. Several studies using hypothetical scenarios demonstrated that teachers as observers of exclusion among students show a general tendency to reject exclusion (Beißert and Bonefeld, 2020; Grütter et al., 2021; Kollerová and Killen, 2021). Witnessing social exclusion typically induces feelings of empathy with the excluded person (Wesselmann et al., 2013). Several studies found evidence that this is also the case for teachers when they witness exclusion among their students (Grütter et al., 2021; Szekely et al., under review). For instance, in a study by Grütter et al. (2021), the most frequently referenced emotions that teachers reported when reasoning about an exclusion scenario were feeling sad and sympathetic for the excluded student. In line with these findings, we assume that based on empathy with the excluded person, combined with the knowledge about the severe consequences associated with social exclusion, teachers show a general tendency to reject exclusion among students.

Besides these general tendencies, it is of interest whether teachers’ reactions to social exclusion might be influenced by characteristics of the target of exclusion (i.e., the excluded student) or by characteristics of the teachers as observers of exclusion. In this context, one important characteristic might be gender. More specifically, the gender of the observing teacher on the one hand, and the gender of the excluded student on the other hand. In the current study, we focus on these two aspects when investigating teachers’ reactions to hypothetical exclusion scenarios.

It has already been shown in different contexts that females tend to evaluate exclusion as more reprehensible than males (Killen and Stangor, 2001; Horn, 2003; Malti et al., 2012; Beißert et al., 2019). This also holds for female teachers (Beißert and Bonefeld, 2020; Beißert et al., 2021).

One possible explanation for this could be gender-specific socialization. Namely, the socialization of girls typically has a stronger focus on harmony and the avoidance of interpersonal struggles (Cross and Madson, 1997; Zahn-Waxler, 2000; Hwang and Mattila, 2019). Moreover, in many families, the harmful consequences of aggressive behaviors are much more addressed in the socialization of girls compared to boys, which might lead to more pronounced feelings of empathy in girls (Smetana, 1989). In line with this, females of different ages have been shown to be more empathic than males (e.g., Rueckert and Naybar, 2008; Schulte-Rüther et al., 2008; D’Ambrosio et al., 2009; Van der Graaff et al., 2014).

Thus, female socialization might lead to stronger feelings of empathy on the one hand and a stronger focus on interdependence, belonging, and community on the other hand. This is in accordance with Bakan’s (1966) theory of the two basic dimensions “agency” and “communion” that describe how individuals relate to their social world. The main assumption of this theory is that females and males are differentially socialized in terms of the relative emphasis on agency and communion (Bakan, 1966). Agency refers to an individual striving to assert the self, master the environment, experience competence, and achievement. Whereas communion refers to an individual’s desire to cooperate and connect closely with others. While females are typically socialized with a stronger focus on communal goals, the socialization of males has a strong focus on agentic goals. As a consequence, females—being communion-oriented individuals—experience stronger fulfillment through relationships, whereas males as agency-oriented individuals experience fulfillment through achievement of their individual goals (Guisinger and Blatt, 1994). Thus, it seems evident that females value relationships more than males. In line with prior research as well as in accordance with Bakan’s theory (1966) and considerations related to gender-specific socialization, we assume that female teachers reject social exclusion more strongly than males.

Not only the gender of the observers of exclusion, in our case teachers, might be relevant. Also, the gender of the excluded student might impact teachers’ reactions to social exclusion. To date, there is hardly any research on the gender of the excluded person, especially not in educational contexts. To our knowledge, there is only one study that focused on the role of the excluded person’s gender for teachers’ evaluations of social exclusion in an educational setting. In this study, Kollerová and Killen (2021) found no differences based on the excluded person’s gender in teachers’ evaluations of the wrongfulness of the exclusion. However, they found differences in teachers’ reasoning revealing that the participants used more moral justifications when reasoning about excluded girls compared to excluded boys.

Yet why should the excluded person’s gender be relevant for teachers’ reactions to social exclusion? One possible explanation are social expectations linked to gender.1 Generally, with regard to the two genders, quite different expectations are prevalent. These gender expectations typically impact our thoughts and actions in many ways (Neuburger et al., 2015; Retelsdorf et al., 2015; Mello et al., 2019). Thus, gender expectations might also affect our perception of and reactions to exclusion of boys vs. girls.

Socialization also provides a possible explanatory approach here. Having been socialized throughout our lives, we all have learned and internalized systematically differing expectations regarding males and females. Typical expectations that are relevant in this context are those in line with the assumptions of the aforementioned theory by Bakan (1966): females are usually associated with the dimension of communion; males are traditionally associated with characteristics of agency. That is, we expect girls to strongly value interpersonal affiliation and harmony with others (Spence and Helmreich, 1978; Bem, 1981; Eckes, 2010; Tay et al., 2019). Additionally, in line with traditional gender role expectations, girls are typically perceived as more vulnerable than boys and hence might evoke stronger feelings for care (Stuijfzand et al., 2016). Given that we stereotypically perceive girls—compared to boys—as more communal and more vulnerable beings (Bakan, 1966; Gilligan, 1993; Ely et al., 1998; Eckes, 2010), we might expect that exclusion affects girls more strongly than boys. Based on these considerations on social expectations linked to gender, we assume that exclusion might be perceived as more serious for girls than for boys and in consequence, the exclusion of girls should be rejected more strongly compared to the exclusion of boys.

The purpose of this study is to extend prior research on teachers’ evaluations of and reactions to social exclusion scenarios by analyzing the role of gender. More specifically, we are interested in potential effects of gender-specific socialization and social expectations related to gender. Thus, we focus on the gender of the observing teacher on the one hand and on the gender of the excluded student on the other hand. Focusing on teachers in the role of observers of exclusion among students, we assessed teachers’ evaluations of hypothetical exclusion scenarios. Since particularly teachers’ behavior can have an impact on their students, it is not only important to analyze teachers’ evaluations of exclusion (which reflect an attitudinal aspect), but also their reactions (which capture a behavioral aspect). Given that it is very difficult to realize naturalistic observational studies in the context of social exclusion, especially at schools, we approach the behavioral aspect by assessing behavioral intentions and want to see whether teachers’ evaluations of exclusion translate into respective behavioral intentions. Accordingly, we assess teachers’ anticipated reactions and interventions. More precisely, we asked them how likely they were to intervene in such a situation and what they would specifically do. Our main interest was to determine whether the gender of an excluded student and the gender of the teacher as an observer of exclusion are relevant factors for teachers’ responses to hypothetical exclusion scenarios.

Based on the aforementioned considerations on gender-specific socialization and gender expectations, we want to examine the following hypotheses:

A. We assume teachers to show a general tendency to reject social exclusion among students and to intervene in exclusion situations among students.

B. We hypothesize that female teachers reject social exclusion more strongly and are more likely to intervene compared to male teachers.

C. We expect that the exclusion of girls will be rejected more strongly compared to the exclusion of boys and the likelihood to intervene will be higher when a girl (vs. boy) is excluded.

As an open question, we want to explore if there are any interactions of the excluded student’s gender and the gender of the teachers as observers of exclusion. Further, we want to explore if participants’ justifications for their decision to intervene in the situation or not as well as their anticipated specific actions differ between female and male teachers’ or depending on the excluded students’ gender.

The study included 101 teachers from different school tracks in Germany (Mage = 36.93, SD = 9.84, range: 22–65, 84 females, 17 males). The working experience of the teachers ranged from under 1 to 42 years (M = 8.16, SD = 8.50) with half of the sample being within their first 5 years of service (median = 5.00 years).

The study was conducted as an online survey and participants were recruited via different mailing lists and online groups in social media platforms (e.g., Facebook groups). Moreover, flyers advertising the study were distributed in libraries, schools, and public sites of universities. Participation was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of DGPs (German Psychological Society).

Before starting the actual survey, participants were informed of their data protection rights and learned that participation in the study was anonymous and voluntary. They were also informed, that there were no negative consequences if they decided not to participate or to leave the study early without completing it. Prior to the assessment, participants had to confirm that they were willing to participate in the study and understood the information.

Starting the survey, participants provided demographic information, participants were then presented with a hypothetical exclusion scenario. The study took approximately 10 min per person.

In the hypothetical exclusion scenario, one student was excluded from a study group by its classmates. We varied the gender of this excluded protagonist by presenting either a typical male or female name (Lukas vs. Julia) in the scenario. The names used in the scenarios had been pretested in a former study by Bonefeld and Dickhäuser (2018). The exact wording of the scenario was as follows:

While packing up after class in 7th grade, you observe some students making an appointment to study together. Lukas/Julia would like to join the learning group. The other students tell him/her that he/she can’t join.

The study was realized as a between-subjects design. The participants were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions (51 were assigned the version with a female protagonist, 50 to the version with the male protagonist).

As we wanted to assess not only attitudinal but also behavioral aspects, we assessed participants’ evaluations of the exclusion situation on the one hand and their likelihood to intervene in such a situation and the specific actions they would undertake on the other hand. We used a seven-point Likert-type scale consisting of three items to assess the evaluations of the exclusion scenario. Specifically, we asked the participants to rate how (1) not okay/okay, (2) unfair/fair, and (3) unjustifiable/justifiable the scenario was. Based on these three items, a score was created indicating a participant’s evaluation of the exclusion (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79). High scores indicate low rejection of exclusion and low numbers indicate strong rejection of exclusion. Moreover, we asked the participants how likely they were to intervene, given the situation took place in their class. The likelihood of intervention was also assessed using a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = very unlikely to 7 = very likely). Eventually, we asked the participants to justify their decision and to indicate what specific actions they would have taken (open-ended questions).

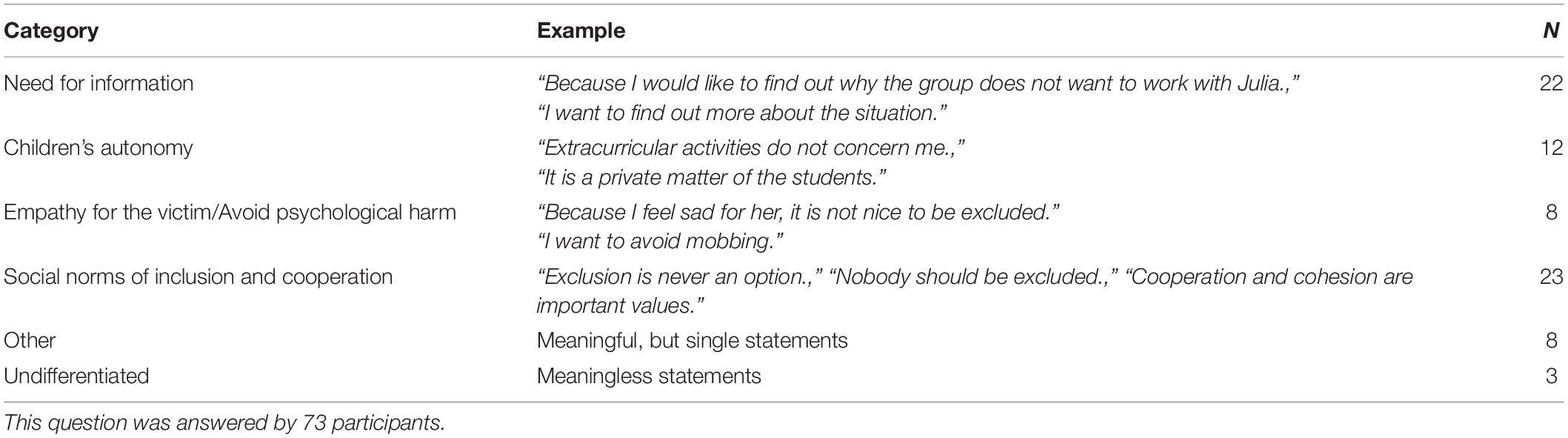

The coding systems for the open-ended questions are based on the study by Beißert and Bonefeld (2020) and were extended by inductively developing categories from the surveys themselves (see Tables 1, 2 for an overview and examples). The coding was completed by two independent coders, that were not allowed to code more than three relevant justifications for each statement. Based on 20% of the interviews we calculated a high interrater reliability, with Cohen’s kappa = 0.96 for both, for the justifications of the likelihood of intervention as well as for the specific actions.

Table 1. Coding system for justifications of likelihood of intervention and frequencies for each category.

Univariate ANOVAs were used to test for differences in the evaluation of exclusion and the likelihood of intervention between the different experimental conditions and between male and female participants.

Repeated measures ANOVAs on the proportional use of categories were conducted to analyze reasoning data from the open-ended questions. ANOVA frameworks are appropriate for repeated measures reasoning analyses because ANOVAs are robust to the problem of empty cells, whereas other data analytic procedures require cumbersome data manipulation to adjust for empty cells (see Posada and Wainryb, 2008, for a more thorough explanation and justification of this data analytic approach).

All analyses were firstly run with participants’ age and years of service experiences included. But as there were no effects based on these variables in any of the analyses, we dropped these variables from the analyses for the sake of simpler models.

In line with our expectations, we found a general tendency to reject exclusion across both protagonists, i.e., a right-skewed distribution on the evaluation scale with a skewness of 0.21 (SE = 0.25), a mean of 2.94 (SD = 1.14), mode = 4.00, and median = 3.00.

To analyze differences in the evaluation of exclusion based on the gender of the participants and the gender of the excluded person, a 2 (participant gender: male, female) × 2 (protagonist gender: male, female) univariate ANOVA was conducted.

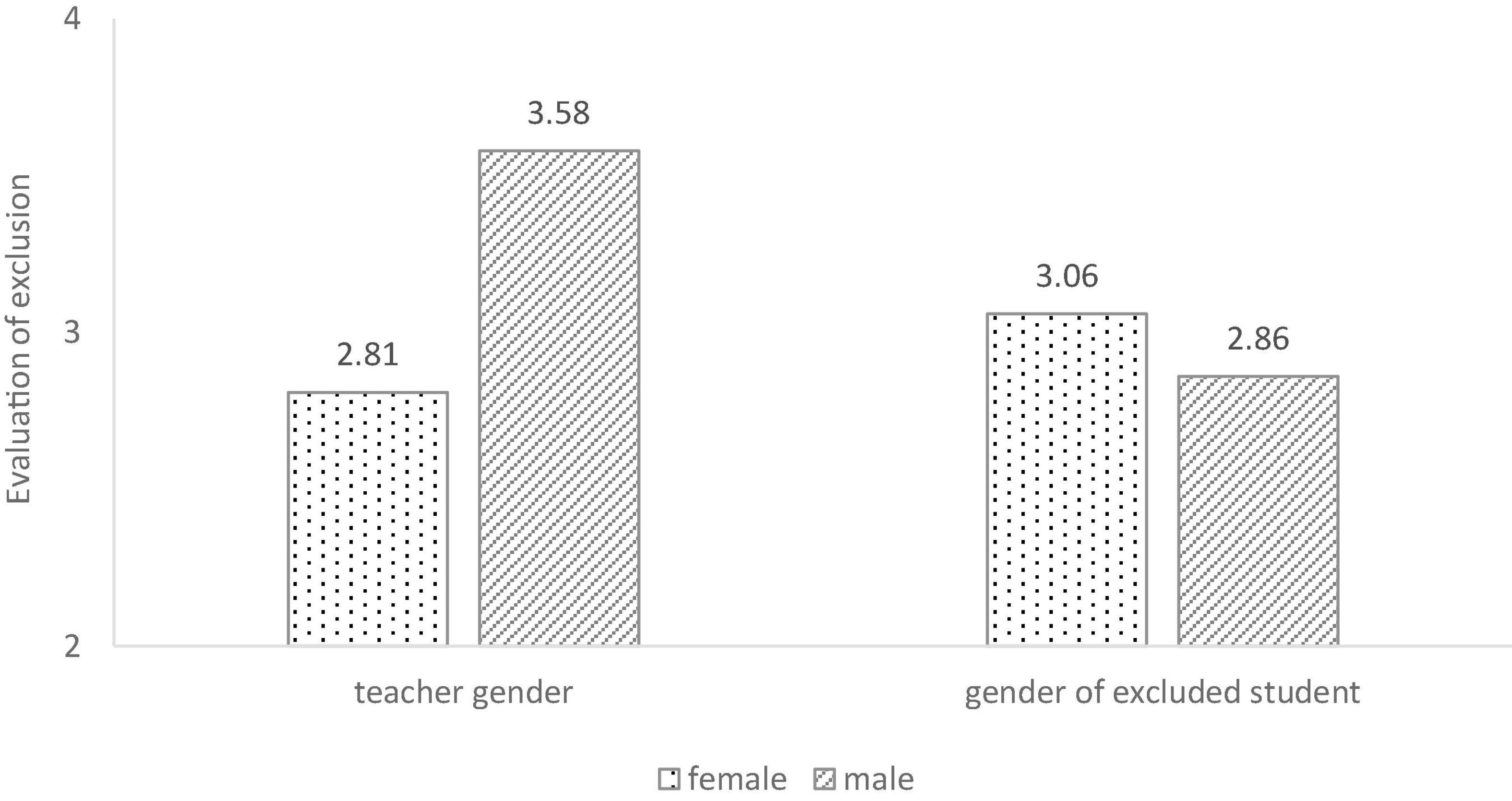

As expected, there was a main effect of participant gender, F(1,86) = 4.94, p = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.05, demonstrating that females (M = 2.81, SD = 1.01) rejected exclusion more strongly than males (M = 3.58, SD = 1.50). There was no effect of the gender of the protagonist, nor any interaction effects. See Figure 1 for a graphical presentation of these results.

Figure 1. Evaluation of exclusion as a function of teacher gender and the gender of the excluded student. High numbers indicate high acceptability of exclusion; low numbers indicate strong rejection of exclusion.

This question was answered by 86 participants. The descriptive analyses showed that 56 participants (65.1%) tended to intervene, 22 participants (25.6%) tended not to intervene, and 8 (9.3%) participants chose the middle of the scale, indicating that it was as likely that they would intervene as not intervene.

To test for differences in the likelihood of intervention, a 2 (participant gender: male, female) × 2 (protagonist gender: male, female) univariate ANOVA was conducted. As preliminary analyses revealed no effects of participants’ age or the years of participants’ service experiences, these variables were not included in the analysis for the sake of a simpler model.

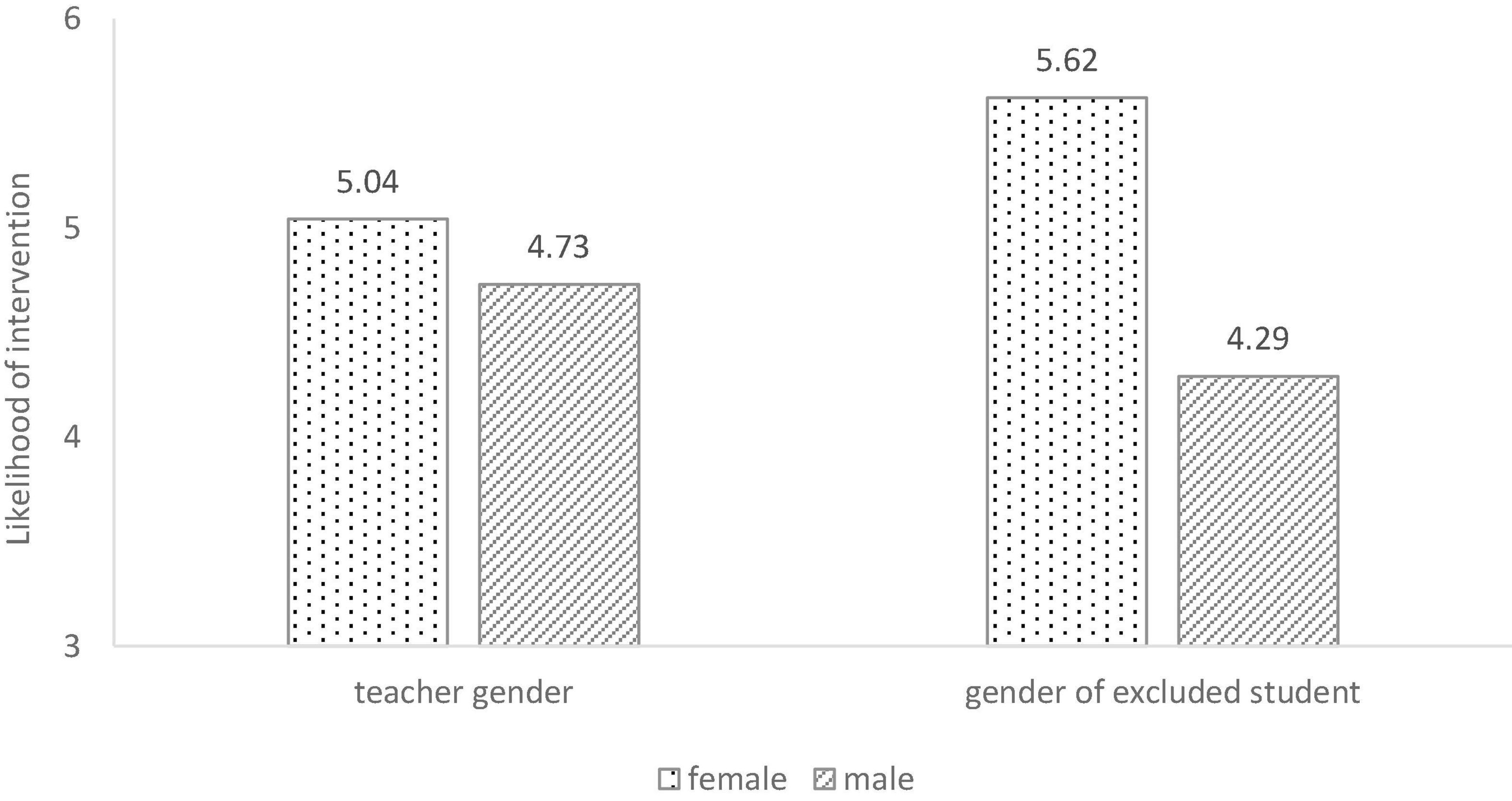

As expected, there was a main effect of the gender of the protagonist, F(1,82) = 14.11, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.15, revealing that participants were less likely to intervene in scenarios in that a boy was excluded (M = 4.29, SD = 2.03) compared to scenarios in that a girl was excluded (M = 5.62, SD = 1.37). There was no effect of the participants’ gender, nor any interaction effects. See Figure 2 for a graphical presentation of these results.

Figure 2. Likelihood of intervention as a function of teacher gender and the gender of the excluded student. High numbers indicate high likelihood to intervene; low numbers indicate low likelihood to intervene.

To analyze the participants’ justifications why they would tend to intervene or not as well as their specific actions, we conducted reasoning analyses on the proportional use of the coded categories. In order to see whether the specific justifications were related to the decision to intervene or not, we created a new variable out of the seven-point scale measuring the likelihood of intervention, resulting in the three categories “tendency to intervene,” “indecisive,” and “tendency not to intervene.”

Using this new variable, we ran a 3 (decision: no intervention, indecisive, intervention) × 2 (participant gender: male, female) × 2 (protagonist: boy, girl) × 4 (justification: need for information, children’s autonomy, empathy for the victim/avoid psychological harm, social norms of inclusion and cooperation) ANOVA with repeated measures on the factor “justification.” The Huynh–Feldt adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity.

This analysis revealed an interaction effect of justification and decision, F(6,192) = 2.63, p < 0.018, ηp2 = 0.08, demonstrating that “need for information” and “social norms of inclusion and cooperation” were mainly used by those who tended to intervene, whereas “children’s autonomy” was mainly used by those who tended not to intervene. However, there were no main or interaction effects based on the gender of the participants or the gender of the protagonist.

In order to get a better understanding of how teachers would intervene, we analyzed their answers to the open-ended question of what they would specifically do when intervening in the situation. To test for differences in these answers based on the gender of the participants and the gender of the protagonist, a 2 (participant gender: male, female) × 2 (protagonist: boy, girl) × 4 (action: ask for reasons, conversation, inclusion-oriented behavior, find an alternative solution for excluded student) ANOVA was run with repeated measures on the factor “action.” The Huynh–Feldt adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity.

This analysis revealed a main effect of action, F(4.33,44.23) = 6.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.09, indicating that participants stated significantly more often that they would ask for reasons or talk to the students than they would try to find an alternative solution for the excluded student. The frequency of inclusion-oriented behavior was not different from the other actions. Again, there were no main or interaction effects based on the gender of the participants or the gender of the protagonist.

The current study investigated teachers’ reactions to social exclusion scenarios in Germany. Focusing on teachers as observers of social exclusion, we used hypothetical scenarios in which a student (girl vs. boy) was excluded by other children in class. We assessed teachers’ evaluations of the exclusion behavior as well as how likely they were to intervene in the situation, and what they would specifically do. To extend prior research, we focused on the role of gender for teachers’ reactions to social exclusion. More specifically, we focused on the gender of the excluded student on the one hand and the gender of the observing teacher on the other hand.

As expected, the teachers in our study showed a general tendency to reject social exclusion among students. This replicates the findings of other studies (e.g., Beißert and Bonefeld, 2020; Grütter et al., 2021; Kollerová and Killen, 2021), which overall provide strong evidence that teachers generally reject social exclusion among students. This tendency to reject exclusion seems to translate into action intentions insofar that the majority of the participating teachers stated that they would have intervened in the situation if it had happened in their class.

Based on considerations of gender-specific socialization (Bakan, 1966; Cross and Madson, 1997; Zahn-Waxler, 2000) we had assumed that female teachers would reject social exclusion even more strongly than male teachers. In terms of the evaluation of social exclusion, we found evidence for this assumption. Interestingly, these gender differences in the evaluation of exclusion did not manifest in teachers’ expected likelihood to intervene in the situation. Female teachers were not more likely to intervene in the situation than male teachers. One possible explanation for this discrepancy between the evaluation of and the expected reaction to social exclusion could also lie in gender-specific socialization. Women are socialized to connect with others and strive for companionship, but less to be self-effective agents (Bakan, 1966). In line with this, females attach great value to relationships (Guisinger and Blatt, 1994) and have a strong need for harmony (Hwang and Mattila, 2019). This might lead females to be hesitant to intervene in the exclusion situation because intervening might be conceptualized as getting involved in an interpersonal conflict. Hence, even though females reject exclusion more strongly, they might not take the step to action. However, one important limitation is that there were only 14% male teachers in the sample, and thus, the results should be considered with caution.

Interestingly, the low proportions of male participants are a typical problem of many online studies (Cull et al., 2005; Cheung et al., 2017; Beißert et al., 2020) and especially in studies on social exclusion (Butler, 2012; Butler and Shibaz, 2014; Beißert et al., 2021) with about 90% female participants. And even though we find a higher base rate of females compared to males among teachers, these samples as well as our sample include even more females than the proportion of female teachers in Germany (which would be appr. 73%, Statista Research Department, 2021). This might indicate that there is some self-selection of helpful individuals, since more helpful individuals are presumably more likely to participate in studies voluntarily. Nevertheless, further research should continue to investigate whether these results can be replicated in a sample with more male teachers.

The gender of the excluded student did not affect teachers’ evaluation of the exclusion situation. The exclusion of boys and girls was evaluated equally reprehensible. However, the gender of the excluded student did influence teachers’ behavioral intentions. As expected, teachers were more likely to intervene in scenarios in that a girl was excluded compared to scenarios in that a boy was excluded. This fits to our assumptions that this is due to gender expectations such as girls being more likely to strive to connect with others (communion) while boys tend to be more focused on individual goals (agency) (Bem, 1981). Therefore, boys may be seen as less vulnerable and less affected by social exclusion, which could induce a weaker need to intervene and protect them.

We could not find any differences between female and male teachers’ justifications to intervene or not, nor were there any differences based on the gender of the excluded student. Thus, the finding of Kollerová and Killen (2021) that teachers used more moral justifications when reasoning about excluded girls compared to excluded boys could not be replicated in the current study. Gender was not relevant for teachers’ reasoning.

Interestingly, teachers’ decisions to intervene or not were associated with different considerations. Namely, if teachers conceptualized the exclusion scenario as something that falls in the children’s scope of action., i.e., when they referenced children’s autonomy as a justification, they were less likely to intervene compared to those teachers who focused on socio-moral aspects such as inclusion and cooperation as social norms or compared to those who understood the situation to be ambiguous and stated their need for further information. That means that teachers’ tendency to intervene seems to depend on how they perceive the exclusion situation—but independent of their own gender or the gender of the excluded student. In this context, it is encouraging that many teachers wanted to ask for reasons to better understand the situation in order to find out if further interventions were necessary or not.

All in all, we can say that gender is an important aspect in the context of social exclusion. On the one hand, the gender of the observing teacher is relevant as females reject exclusion even more strongly than males. On the other hand, the gender of the excluded student impacted teachers’ reactions to social exclusion as they were less likely to intervene when a boy was excluded compared to a girl. We explain these findings with gender-specific socialization and social expectations linked to gender. Namely, the stronger focus on communal aspects in girls’ socialization which is associated with a high value of relationships and harmony on the one hand, and the perception of females as being more vulnerable and more in need of relatedness than males, on the other hand. Future research should systematically examine whether such a communal orientation with a higher focus on interpersonal affiliation in females really can explain the current findings.

Additionally, further research should pay more attention to the assessment of evaluations and behavior or at least behavioral intentions. In this study, it becomes clear that even though the general tendency to reject exclusion among students manifests in a general tendency to intervene, the effects related to gender reveal differential patterns regarding the evaluations and the behavioral tendency. Hence, further research should include both attitudinal and behavioral measures. Moreover, in this context, it would be of great interest to conduct real behavioral studies in naturalistic settings in order to investigate whether the reported behavioral intentions transmit into the respective actions.

Interestingly, the gender differences that we found regarding the reported behavioral intentions are not reflected in teachers’ reasoning or their specific actions. That means, teachers are more likely to intervene when girls are excluded than when boys are excluded. However, once they decide to intervene, the specific actions are not related to the gender of the excluded student. This leads us to the assumption that the differences in the likelihood to intervene or not are no conscious tendencies but rather automatisms based on socialized expectations linked to gender. Thus, it is crucial to sensitize teachers to such expectations and help them reflect their own gender-specific expectations. Further, teachers should be encouraged to treat both genders equally and to consequently intervene also when boys are excluded. It is important to make teachers aware of the fact that boys and girls suffer equally from the severe consequences of social exclusion.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

HB and MB developed the idea and the design of the study. MS made a first draft of the manuscript which was revised by HB and MB. All authors have approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved, and have contributed meaningfully to the manuscript and analyzed and interpreted the data.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We would like to thank the undergraduate research assistants Michelle Barth and Julia Hildebrandt for their help to prepare and conduct this study and Lea Markhoff for her support with the data preparation and literature research. And we are grateful to all teachers who participated in this study.

Beißert, H., and Bonefeld, M. (2020). German Pre-service Teachers’ Evaluations of and Reactions to Interethnic Social Exclusion Scenarios. Front. Educ. 5:586962. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.586962

Beißert, H., Köhler, M., Rempel, M., and Kruyen, P. (2020). Ein Vergleich traditioneller und computergestützter Methoden zur Erstellung einer deutschsprachigen Need for Cognition Kurzskala. Diagnostica 66, 37–49. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924/a000242

Beißert, H., Staat, M., and Bonefeld, M. (2021). The role of ethnic origin and situational information in teachers’ reactions to social exclusion among students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 24, 1511–1533. doi: 10.1007/s11218-021-09656-5

Beißert, H., Bonefeld, M., Schulz, I., and Studenroth, K. (2019). Beurteilung sozialer Ausgrenzung unter Erwachsenen: Die Rolle des Geschlechts. [Poster presentation]. Mannheim: Moraltagung.

Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: a cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 88, 354–364. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.88.4.354

Bonefeld, M., and Dickhäuser, O. (2018). (Biased) Grading of Students’ Performance: students’ Names, Performance Level, and Implicit Attitudes. Front. Psychol. 9:481. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00481

Buhs, E. S., Ladd, G. W., and Herald, S. L. (2006). Peer exclusion and victimization: processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection and children’s classroom engagement and achievement? J. Educ. Psychol. 98, 1–13. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.1

Butler, R. (2012). Striving to connect: extending an achievement goal approach to teacher motivation to include relational goals for teaching. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 726–742. doi: 10.1037/a0028613

Butler, R., and Shibaz, L. (2014). Striving to connect and striving to learn: influences of relational and mastery goals for teaching on teacher behaviors and student interest and help seeking. Int. J. Educ. Res. 65, 41–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2013.09.006

Cheung, K. L., Ten Klooster, P. M., Smit, C., de Vries, H., and Pieterse, M. E. (2017). The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: a comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health 17:276. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4189-8

Cross, S. E., and Madson, L. (1997). Models of the self: self-construals and gender. Psychol. Bull. 122, 5–37. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5

Cull, W. L., O’Connor, K. G., Sharp, S., and Tang, S. F. S. (2005). Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Services Res. 40, 213–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00350.x

D’Ambrosio, F., Olivier, M., Didon, D., and Besche, C. (2009). The basic empathy scale: a French validation of a measure of empathy in youth. Pers. Individ. Dif. 46, 160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.020

Eckes, T. (2010). “Geschlechterstereotype: von rollen, identitäten und vorurteilen,” in Handbuch Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung. Theorie, Methoden, Empirie, eds R. Becker and B. Kortendiek (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften), 178–189.

Ely, R., Melzi, G., Hadge, L., and McCabe, A. (1998). Being brave, being nice: themes of agency and communion in children’s narratives. J. Pers. 66, 257–284. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00012

Fuhrmann, D., Casey, C. S., Speekenbrink, M., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2019). Social exclusion affects working memory performance in young adolescent girls. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 40:100718. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100718

Gazelle, H., and Druhen, M. J. (2009). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion predict social helplessness, upset affect, and vagal regulation in response to behavioral rejection by a friend. Dev. Psychol. 45, 1077–1096. doi: 10.1037/a0016165

Gilligan, C. (1993). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grütter, J., Barth, C., Tschopp, and Buholzer, A. (2021). “Teachers’ emotional reactions and reasoning about social exclusion based on learning difficulties and hyperactive behavior,” in Proceedings of the 47th AME Conference.

Guisinger, S., and Blatt, S. J. (1994). Individuality and relatedness: evolution of a fundamental dialectic. Am. Psychol. 49, 104–111. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.49.2.104

Horn, S. S. (2003). Adolescents’ reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Dev. Psychol. 39, 71–84. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.71

Hwang, Y., and Mattila, A. S. (2019). Feeling left out and losing control: the interactive effect of social exclusion and gender on brand attitude. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 77, 303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.07.010

Jiang, S., and Ngai, S. S.-Y. (2020). Social exclusion and multi-domain well-being in Chinese migrant children: exploring the psychosocial mechanisms of need satisfaction and need frustration. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 116:105182. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105182

Killen, M., Mulvey, K. L., and Hitti, A. (2013). Social exclusion in childhood: a developmental intergroup perspective. Child Dev. 84, 772–790. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12012

Killen, M., and Stangor, C. (2001). Children’s social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Dev. 72, 174–186. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00272

Kollerová, L., and Killen, M. (2021). An experimental study of teachers’ evaluations regarding peer exclusion in the classroom. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 463–481. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12373

Malti, T., Killen, M., and Gasser, L. (2012). Social judgments and emotion attributions about exclusion in Switzerland. Child Dev. 83, 697–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01705.x

Mello, S., Tan, A. S. L., Sanders-Jackson, A., and Bigman, C. A. (2019). Gender Stereotypes and Preconception Health: men’s and Women’s Expectations of Responsibility and Intentions to Engage in Preventive Behaviors. Matern. Child Health J. 23, 459–469. doi: 10.1007/s10995-018-2654-3

Mulvey, K. L., Gönültaş, S., Irdam, G., Carlson, R. G., DiStefano, C., and Irvin, M. J. (2021). School and Teacher Factors That Promote Adolescents’ Bystander Responses to Social Exclusion. Front. Psychol. 11:581089. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.581089

Murray-Close, D., and Ostrov, J. M. (2009). A longitudinal study of forms and functions of aggressive behavior in early childhood. Child Dev. 80, 828–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01300.x

Neuburger, S., Ruthsatz, V., Jansen, P., and Quaiser-Pohl, C. (2015). Can girls think spatially? Influence of implicit gender stereotype activation and rotational axis on fourth graders’ mental-rotation performance. Learn. Individ. Differ. 37, 169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2014.09.003

Posada, R., and Wainryb, C. (2008). Moral development in a violent society: colombian children’s judgments in the context of survival and revenge. Child Dev. 79, 882–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01165.x

Retelsdorf, J., Schwartz, K., and Asbrock, F. (2015). Michael can’t read! J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 186–194. doi: 10.1037/a0037107

Riva, P., and Eck, J. (2016). “The Many Faces of Social Exclusion,” in Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing its Impact, 1st Edn, eds J. Eck and P. Riva (Cham: Springer), ix–xv.

Rueckert, L., and Naybar, N. (2008). Gender differences in empathy: The role of the right hemisphere. Brain Cogn. 67, 162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.01.002

Schulte-Rüther, M., Markowitsch, H. J., Shah, N. J., Fink, G. R., and Piefke, M. (2008). Gender differences in brain networks supporting empathy. Neuroimage 42, 393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.04.180

Sebastian, C., Viding, E., Williams, K. D., and Blakemore, S.-J. (2010). Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain Cogn. 72, 134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008

Smetana, J. G. (1989). Toddlers’ social interactions in the context of moral and conventional transgressions in the home. Dev. Psychol. 25, 499–508. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.25.4.499

Spence, J. T., and Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and Femininity: Their Psychological Dimensions, Correlates, and Antecedents. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Statista Research Department (2021). Frauenanteil unter den Lehrkräften nach Schulart 2021. Available online at: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1129852/umfrage/frauenanteil-unter-den-lehrkraeften-in-deutschland-nach-schulart/ (accessed November 15, 2021).

Stuijfzand, S., Wied, M., de Kempes, M., van de Graaff, J., Branje, S., and Meeus, W. (2016). Gender Differences in Empathic Sadness towards Persons of the Same- versus Other-sex during Adolescence. Sex Roles 75, 434–446. doi: 10.1007/s11199-016-0649-3

Szekely, L., Bonefeld, M., and Beißert, H. (under review). Teachers’ Reactions to Social Exclusion among Students: The Effect of Ethnic Origin and Background Information. Open Psychology.

Tay, P. K. C., Ting, Y. Y., and Tan, K. Y. (2019). Sex and care: the evolutionary psychological explanations for sex differences in formal care occupations. Front. Psychol. 10:867. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00867

Van der Graaff, J., Branje, S., Wied, M., de Hawk, S., van Lier, P., and Meeus, W. (2014). Perspective taking and empathic concern in adolescence: gender differences in developmental changes. Dev. Psychol. 50, 881–888. doi: 10.1037/a0034325

Wesselmann, E. D., Grzybowski, M. R., Steakley-Freeman, D. M., DeSouza, E. R., Nezlek, J. B., and Williams, K. D. (2016). “Social exclusion in everyday life,” in Social Exclusion: Psychological Approaches to Understanding and Reducing its Impact, 1st Edn, eds J. Eck and P. Riva (Cham: Springer), 323.

Wesselmann, E. D., Williams, K. D., and Hales, A. H. (2013). Vicarious ostracism. Front. Human Neurosci. 7:153. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00153

Williams, K. D. (2009). “Chapter 6 Ostracism,” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. Vol. 41, ed. M. P. Zanna (Cambridge, US: Academic Press), 275–314. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2601(08)00406-1

Zahn-Waxler, C. (2000). “The development of empathy, guilt, and internalization of distress: Implications for gender differences in internalizing and externalizing problems,” in Wisconsin Symposium on Emotion: Anxiety, Depression, and Emotion, ed. R. Davidson (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 222–265.

Keywords: social exclusion, teacher reactions, teacher evaluations, gender differences, gender role expectations, socialization

Citation: Beißert H, Staat M and Bonefeld M (2022) The Role of Gender for Teachers’ Reactions to Social Exclusion Among Students. Front. Educ. 7:819922. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.819922

Received: 22 November 2021; Accepted: 18 January 2022;

Published: 14 February 2022.

Edited by:

Daniela Barni, University of Bergamo, ItalyReviewed by:

Francesca Giovanna Maria Gastaldi, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Beißert, Staat and Bonefeld. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hanna Beißert, YmVpc3NlcnRAZGlwZi5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.