- Faculty of Educational Studies, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

The research critically evaluates ways of narrating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in Polish secondary-school history textbooks. Based on a repeated critical reading and discourse analysis of both Israeli and Arab-Palestinian narratives, the study focuses on the choice of pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli designations when naming the conflict and the incorporation or silencing of pro-Israeli and/or pro-Palestinian voices in textbook narratives. Reducing Palestinians to a displaced population and depicting Palestinian liberation movement as terrorism are some elements of the anti-Palestinian/pro-Israeli textbook narrative. Reducing Israel to the status of a Zionist State and presenting Zionism as a colonial movement are the examples of pro-Palestinian textbook narrative. The research found that although the over-simplistic “aggressor-victim” format is not dominant, the coverage of Israeli-Palestinian conflict in most of the analyzed textbooks is unbalanced, sometimes even misleading and implying asymmetrical relations between Jews/Zionists and Arabs/Palestinians.

Introduction

Western representations of Islam and the Arab world changed in the second half of the 20th century. The lens through which the dominant Western judgments of the Arab world was focused was the changing political situation due to the partition of historic Palestine and its territorial division into one state for Jews and the other for Arabs, the oil boom, the rise of terrorism and religious extremism. These overlapping themes were pointed out by Wiseman (2021, p. 248): “The main determinants of how the Western world has viewed the Middle East since the middle of the twentieth century have been the oil industry, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and terrorism.” The roots of the Middle East’s transformation into the epicenter of world’s crisis zone in the 20th century are the highly unequal core-periphery relations. As explained by Hinnebusch (2003, p. 3): “The Middle East, once an independent civilization, was turned, under imperialism, into a periphery of the Western-dominated world system. As the location of both Israel and of the world’s concentrated petroleum reserves, the Middle East remains an exceptional magnet for external intervention which, in turn, has kept anti-imperialist nationalism alive long after de-colonization.” Another reason for the Middle East’s crisis epicenter transformation was the incongruence between territory and identity due to the colonial powers’ arbitrary imposition of state boundaries. The conflicts between the loyalties to the new states and the supra-state identities, e.g., Pan-Arabist and Pan-Islamic movements, led to a peculiar “dualism”: “While they (the Arab states – DH-W) have tenaciously defended the sovereignty of their individual states, legitimacy at home has depended on their foreign policies appearing to respect Arab-Islamic norms” (Hinnebusch, 2003, p. 5). Both the struggle against imperialist control and the defense of regional identities against the arbitrary imposition of borders, have been ceaselessly intertwined with the two other sources of conflict built into the Middle East: the struggle over control of the region’s oil and the Arab-Israeli conflict: the struggle over Palestine (Hinnebusch, 2003, p. 9).

What makes the understanding of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle so difficult – quoting historian and the former Israeli ambassador to the United States, Itamar Rabinovich – is that “there is no single Arab-Israeli dispute” (Caplan, 2020, p. 35). The core conflict between Palestine and Israel – a classic conflict of two national movements over the same land – is just one of many distinct, but interrelated disputes in the region. What makes this ethnic and nationalist confrontation so long-lasting and resistant to resolution is its historical transformation, that has been changing the nature of the clash and complicating its dynamics. Alan Dowty, the author of the book “Israel/Palestine” describes four key stages of the conflict. Origins of the conflict lie “in the 1880s, when Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe began settling in the historical Land of Israel (…), then a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, in order to re-establish a Jewish presence there” (Dowty, 2017, p. 3). The first stage lasted until 1948 as a conflict between two national communities to control a single piece of land --a clash between two national movements: Jewish (Zionism) and Arab/Palestinian.1 The second stage – from the 1947 to 1949 war until the early 1990s – was “an interstate conflict between Israel and its Arab neighbors” (Dowty, 2017, p. 182). This shift initially eclipsed the Palestinian cause. However, moving into the 1990s, Palestine gradually reasserted its central place as one of the two main sides of the conflict. The third stage lasted between the 1990s and 2000s as a predominantly Israeli-Palestine confrontation, with less external Arab states engagement; a relationship built in a futile attempt to share the land between two states: Israel and Palestine (a two-state solution). The year 2001 constituted a turning point that made the religious dimension more significant than a national one. Previously, religious fundamentalism was prominent on both sides, but it was not predominant. The fourth stage of the conflict that has lasted until the present day, is still positioned as an unresolved Israeli-Palestinian struggle, but more and more intertwined into regional and global affairs, and increasingly influenced by religious fundamentalists as non-state actors undermining state authority. The question of the ethnic identification of both sides of the conflict seems of vital importance in the Israeli/Palestinian case “where identities have changed over time and have often been challenged by the other side as lacking historical foundation” (Dowty, 2017, p. 8). There is however a further perspective of sovereignty: the question of the political right of national self-determination of both groups that makes this conflict not an ethnic, but a national one.

There are two contrasting ways of representing and interpreting the conflict. The pro-Israeli perspective emphasizes the return to the ancient homeland and the heroic effort as pioneers in harsh conditions and in an inhospitable territory. As such, Zionism is a legitimate expression of Jewish nationalism, especially after the struggle for survival after WWII. The pro-Palestinian perspective sees the Jewish national revival as an example of European colonist expansion into the Middle East, as a foreign intrusion and an attempt to overpower the indigenous population. Accepting one narrative will inevitably undermine the legitimacy of the other narrative. The decision to view the conflict only through one of the lenses – pro-Israeli or pro-Palestinian – leads to a number of far-reaching consequences. Caplan (2020, p. 52) signifies these consequences as follows: “First, it will strongly affect how one weighs all the historical data, and how one interprets the evidence and arguments put forth by the protagonists. Secondly, and perhaps more seriously, it will amount to choosing one side over the other by endorsing the main claim of its narrative while rejecting the other.”

When narrating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a futile attempt of staying unbiased and neutral must give way to a “double narrative” without the intention of convincing the reader of the authenticity of one model over another. The transfer of the above arguments to the level of school textbook narrative means the necessity of accepting the mutual incompatibility of both perspectives. Thinking of it as an antinomy, we have to agree that such a “double narrative” will always be contested and subject to only partial approval. To accept the contradictory nature of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict at the level of history textbook narratives means not only to allow both conflicting perspectives to “speak” in textbook narratives; it also requires that both perspectives are treated as “authentic expressions of the protagonists’ respective narratives” (Caplan, 2020, p. 55). Caplan’s recommendation to consider pro-Palestinian (“Zionism as a movement of conquest”) and pro-Israeli (“Zionism as a movement of national liberation”) narratives as non-binary constitutes a useful, but difficult guideline for school historiography to bring both versions of the historical experience to the fore.

How difficult it is to obtain middle-ground historical narratives has been shown recently in a report by two academics, Professors John Chalcraft and James Dickins (The Independent, 2021), giving evidence of deliberate distortion of historical data in two history textbooks to fit a political agenda of pro-Israel lobbying groups in the United Kingdom. After comparing the texts of original and revised versions of two Pearson-published upper-secondary school history textbooks, the authors of the report pointed to the distortion of historical and political facts relating to Israel/Palestine. After analyzing 294 alterations, the report concluded: “We show how the revisions have consistently under-played and explained Jewish and Israeli violence, while amplifying and leaving unexplained Arab and Palestinian violence. They have left intact accounts of Jewish and Israeli suffering, while downplaying and editing accounts of Arab and Palestinian suffering” (The Guardian, 2021). In a subsequent, heated media discussion many eminent historians highlighted the importance of a balanced approach in presenting such a complex and sensitive issue. One of the reactions to the report was the statement of Eugene Rogan, Professor of modern Middle Eastern history at the University of Oxford: “Given Britain’s historical responsibility, it is particularly important that the subject be taught in a way that is impartial and objective. It is a betrayal of such objectivity to allow Israel advocates the opportunity to edit teaching materials without giving Palestine advocates an equal opportunity to provide input” (Jewish Voice for Labour, 2021).

The main question of the study was placed within the area of historical inquiry as a pedagogical practice and relates to the key issue of introducing other narratives into history textbooks, bringing non-standard interpretations and presenting opposing points of view on historical facts. To what extent are the pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian voices in textbook narratives incorporated or silenced? What is the choice of pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli designations when naming the conflict in analyzed textbooks? The main objective is the focus on the contrasting elements of Israeli-Palestinian conflict’s depictions reflected in textbook narratives. Reducing Palestinians to a displaced population and depicting Palestinian liberation movement as terrorism are some elements of the anti-Palestinian/pro-Israeli textbook narrative. Reducing Israel to the status of a Zionist State and presenting Zionism as a colonial movement are the examples of pro-Palestinian textbook narrative. Reviewing these elements enables to notice how the two opposite facets (Pro-Israeli – pro-Palestinian) of the “double faced” Israeli-Palestinian debate work together in selected history textbooks.

The article opens with an introduction on main points of changing nature and complicated dynamics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, as well as on two contrasting ways of representing and interpreting the conflict. It then continues with the critical discourse analysis of selected history textbooks, exploring the construction of hegemonic discourses, and simultaneously detecting counter-discourses and/or marginalized discourses. The “Results” section is divided into two subsections. The first focuses on the designations as discursive devises with particular ideological functions. The second presents constructing narratives on two main protagonists, aiming at establishing the narrative (im)balance between Israeli and Palestinian perspectives at different stages of the conflict. The final section “Discussion” focuses on meaning and relevance of the presented results. It also includes recommendations on how to fit historical education into the demands of the present day, bearing in mind the ascribed status of past events, as well as the way the present inevitably influences the interpretation of them. The necessity to include competing narratives as a counter-measure to the excessive political use of history is the underlying assumption of the multi-perspective history teaching. It argues for a change in the monolithic approach to textbook knowledge and allows for it to be seen as a human construct composed not only of selected data, but also opinions and interpretations.

Materials and Methods

Social constructivism with its perspective on realities (being constructions or interpretations) and truth (being subjective and multiple) (Berger and Luckmann, 1967; Hildebrandt-Wypych, 2017) functions throughout the text as a key theoretical reference. The social constructionist approach to education (including teaching history) is based on the principle of the social interchange and negotiation between multiple realities, both reproductive and transformative in its character. Human beings’ inclination to interpret our reality through collectively constructed lenses applies to common systems of cultural representation, with language being of primary importance (Berger and Luckmann, 1967; Hildebrandt-Wypych, 2017).

The mission of education, and particularly of history education, is to constantly actualize the past in the present. History curricula mirror current and politicized perspectives of society’s vision about the past. From a critical perspective, textbooks are not really books as such: they are merely “collections of narratives about loosely connected topics, almost none of which constitutes a satisfactory treatment on either scholarly or pedagogical grounds” (Crawford and Foster, 2008, p. VIII). As a result of the top-down approach to historical knowledge production and dissemination, “curricular contents are not only informed by the insights of historical science, but also by collective national desires, identity needs, mentalities, and political interests”(Wagner et al., 2018, p. 32). History textbooks are produced within a particular set of (imposed and implicit) ideological, cultural, and political parameters. As such, they are the social constructions of the political, economic, and cultural interests, battles and compromises of various groups. The images of the past, present in school history textbooks are never value-free, neutral or objective. Instead of actual historical reality they offer representations of historical reality, altered according to present ideological aims (Hildebrandt-Wypych, 2021).

There is always a question of students’ agency to construct independent responses to the textbook narrative. Some scholars point out that students “do not passively receive,” but “actively read” textbook content, filtering it through their class, racial, gender, and religious background (Apple, 1993, p. 61). However I agree with Podeh (2002, p. 2) when he notes that “most students lack sufficient historical knowledge and consciousness to prompt them to contest existing historical narratives.” Even in the age of instant access to digitalized historical sources and their extensive media discussions, persistence of the implanted textbook messages is rooted in the textbook’s “authority” as one of the main ideological resources.

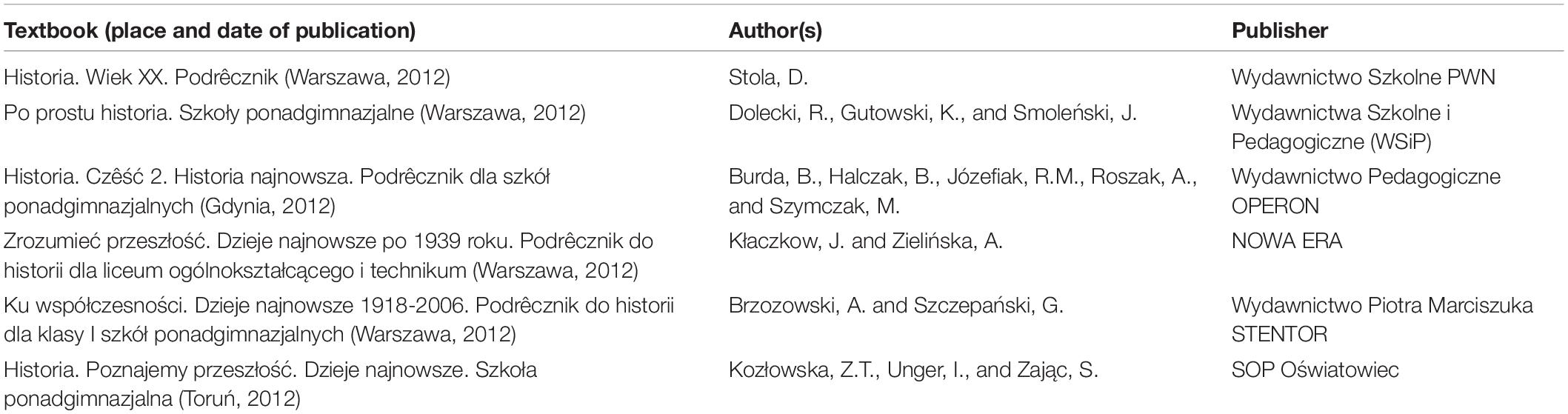

The examination of Israel-Palestine conflict in Polish school historiography was based on a repeated critical reading and discourse analysis of both Israeli and Arab-Palestinian narratives in the six selected history textbooks for the upper secondary level schools, published in the same year – 2012 (see Table 1). All of them were screened and approved for school use in accordance with the national curriculum by the central government (the Ministry of National Education) and published by private, well-known publishing houses. The choice of one corresponding publication date is related to the research objective to capture the narrative differences between teaching materials issued at the same point in time, under the same curriculum and educational policy. All textbooks are based on the same national curriculum standards. Four textbooks were published by four biggest educational publishers in Poland in 2012 (WSiP, PWN, Nowa Era, and Operon), having altogether about 83% market share (Strycharz, 2018). However, for the sake of variety and comprehensiveness, two smaller but significant publishers were included in the analysis (Stentor, SOP Oświatowiec). All publishing houses still are present in the Polish educational market, with their textbooks’ new editions being adjusted to new curriculum standards. Historical facts were not of primary interest in this analysis. The focus of the analysis was on various interpretations of the facts and the disclosure of contrasting representations, biases, and prejudices toward Israeli and Palestinian perspectives on the conflict.

The analysis of the textbook narratives was conducted based on the critical approach to discourse analysis, highlighting the social and ideological nature of words and texts (Strycharz, 2018). The analysis was oriented to critical inquiry and the role of discourse in creating the social world. By looking at the language used the analysis aimed to expose certain codes (values or social beliefs) in the discourse that lead to reproduction of political and social inequalities, as well as stabilize balance of power and domination. As highlighted by Fairclough (1992, p. 76): “People make choices about the design and structure of their clauses which amount to choices about how to signify (and construct) social identities, social relationships, and knowledge and belief.” Textual analysis was focused on semantic and pragmatic properties of textbook rhetoric, including vocabulary (e.g., the choice of pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli designations when naming the conflict; the choice of vocabulary indicating emotional elements, such as aggression, backwardness, suffering, righteousness, injustice, etc.) and discursive schemata (e.g., the incorporation or silencing of pro-Israeli and/or pro-Palestinian voices in a given textbook narrative; the discursive strategy of constructing the Palestinian-Israeli binary as “positive-negative,” “negative-positive,” or even “negative-negative,” with West-centric domination installed). The aim was to explore the construction of hegemonic discourse, and simultaneously detect tensions around marginalized discourses (sometimes) becoming counter-discourses. There is a visible power struggle over meaning within most textbook narratives on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The question arises whether and to what extent in this power struggle is the contrasting voice of “the other side of the conflict” incorporated into each textbook’s narrative. Is there space given to dialog, flexibility, change of perspective, and an “orientation to difference” (Fairclough, 2003)? Or is the difference ignored through attempts to silence certain interpretations while amplifying others? Are the textbook narratives intertextual, that is opening up to bring other, conflicting “voices” into the presentation of Palestinian-Israeli struggle? The focus on the “orientation to difference” facilitates the examination of how textbook narratives construct various group (Palestinian, Arab, Israeli, and Jewish) identities within the conflict. As indicated by Gulliver (2010, p. 729–730), “low orientation to difference (…) works toward the construction of identities as stable, coherent and knowable, whereas an openness to difference can foreground some of the heterogeneity of social positions and the competing and contesting possible claims that could be performed.”

Results

Naming the Conflict – The Designations

Each term chosen as a name for the conflict is a particular discursive device with a particular ideological function. Naming of the conflict may not only unintentionally favor one side of it; it can also – deliberately or not – install a biased perspective of the textbook narrative. The choice of a given term – “Arab-Israel” or “Israeli-Palestinian” – may show or hide power relations, and present inequality of power as natural, non-existent or taken for granted. It can enhance the contested nature and complexity of the conflict; it can also silence the ambivalence of the conflict and construct it as “inevitable.”

Textbooks use a variety of names for the conflict, as well as many different names for the two main protagonists, aka sides of the struggle. The textbook choice of designations of the conflict shows the favorable viewpoint of the conflict itself. By choosing certain lexical items, such as Jews (pol. Żydzi) or Zionists (pol. Syjoniści), Arabs (pol. Arabowie) or Palestinians (pol. Palestyńczycy), each textbook narrative sets a different direction of the process of forming a view or a judgment among students. Not only the use, but also the non-use of a particular designation, turns the reader’s attention to a related interpretation of history, and even to its moral evaluation. And it is not about explicit prejudice or partiality, but the implied meanings of vocabulary items, and their interpretations. As indicated by Caplan (2020, p. 4):“In naming the conflict and defining what it is about, one is immediately, if unwillingly taking a position that will surely be disputed by someone holding a different view.” Textbook authors as producers of the text are socially and ideologically driven to choose particular forms that identify particular meanings, and thus motivate students to turn to particular knowledge, beliefs, and social relationships.

Not using the term “Palestinians” deprives students of a chance to differentiate the Arab world and see the Palestinians as a community with distinct political and national aspirations. It is a wasted opportunity for students to transgress the reductionist idea of Arab world as a single entity, one Islamic civilization. The key distinction between Arabic and Islamic civilization is that the first one is characterized by the national, and the second one by the denominational dimension. The rejection of the Arabic character of the Islamic community, and the emphasis on the religious rather than the national character of the statehood appears in some fundamentalist Pan-Islamist theological trends (e.g., within the Muslim Brotherhood), highlighting the Arab nature of Muslim ideas and the superiority of Arab identity over Islamic identity. Arabness and Muslimness are ideologically linked in Maghreb countries, leading to negation of other, non-Islamic-Arabic identities, e.g., Arab Christians (Perrin, 2014, p. 233). Edward Said’s definition of Palestinians as “the non-Jewish native inhabitants of Palestine, who call themselves (Muslim or Christian) Palestinian Arabs” (Said and Hitchens, 2001, p. 1) may prevent students from developing common stereotypical images of Palestinians as yet another group of Islamic zealots.

On the one hand, as indicated by Caplan (2020, p. 4), “the designations Jews and Arabs refer to wider groups extending beyond those directly contesting the land of Palestine/Israel.” On the other hand though, the term “Zionists” seems too narrow and the designation is accurate to use only to the “Zionist-Palestinian” conflict prior to the creation of the Israeli state in 1948 (Caplan, 2020, p. 5). Some pejorative connotations of the word: “Zionist” are associated not only with the mysterious, obscured power from “The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion.” There is a legacy of the Soviet anti-Zionist rhetoric present during the communist Poland’s anti-Zionist campaign of 1967–1968, following Israel’s victory over Arab nations during the 6-Day War. The elements of this rhetoric have shown remarkable persistence in Polish political culture, as well as some contemporary media discussions, e.g., during the debate about Jedwabne (Michlic, 2007, p. 163). It is therefore possible, as Caplan points out (Caplan, 2020, p. 6), that “the term “Zionists” will understandably be viewed negatively as signifying those who took over the lands and the country they claim as theirs.” J. Michlic (Said and Hitchens, 2001, p. 163–164) gives examples of the ultra-Catholic, right-wing media discourse, in which “the escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Middle East and the second intifada reinforced the image of the Jew as the greatest perpetrator of violence in the world history (…); the perpetrator of the crimes against the Polish nation and against the Palestinian nation (the subject of the Palestinians, their history and their emergence as a nation seeking statehood is not of any serious concern per se in this anti-Jewish narrative, but it solely applied instrumentally to portray the Jews as notorious culprits).”

The most commonly used textbook designation, the “Arab-Israeli conflict,” is an adequate name for a particular historical period: “the territorial and political dispute since 1948 between the state of Israel, on the one hand, and the 20 or so states that consider themselves to be Arab, on the other” (Caplan, 2020, p. 5). As concluded by Dowty (2017, p. 1),“the label “Arab-Israeli conflict” is still more common, even though Palestinians have reclaimed their previous position as Israel’s major antagonists.” Reference to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as the core and narrow perspective, without integrating a broader regional (Arab) dimension, also has its limitations. In a pro-Israeli narrative frequent references to “the Palestinians” may be perceived as illegitimate and the designation “Arab” would be preferred; it would be “consistent with the belief that there is no such thing as a separate Palestinian people who are entitled to a separate Palestinian political state” (Caplan, 2020, p. 6). It would also refer to the national identity discussions and the false opposition between the Israeli Jewish identity constructed as deep-rooted, long-standing and natural, and the Palestinian identity – as flimsy, recent and artificial. Without acknowledging that national identity is – in any case – a fairly recent “invention” (in Gellner’s, Hobsbawm’s or Anderson’s approaches), the Palestinian identity has been subject to continuous belittling in comparison to more prominent national identities, such as the Arab or the Jewish one. As noted by Khalidi (2010, p. xxii–xxiv): “Before the 1990s Palestinian identity was fiercely contested (…) there remains today the familiar undercurrent of dismissiveness of Palestinian identity as being less genuine, less deep-rooted, and less valid than those of other peoples in the region.”

From Arab-Israeli to Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Contrasting Narratives on Two Main Protagonists

Palestine Without the Palestinians

Who are the central protagonists of the conflict? In the PWN textbook there appear two references to the Arab-Israeli war (wojna arabsko-izraelska) and Israeli-Arab wars (wojny izraelsko-arabskie), as well as multiple references to three designations: Jews (Żydzi) or Israelis (Izraelczycy) on one side, and Arabs (Arabowie) – on the other. The designation “Palestinians” appears only once throughout the whole passage “The rise of the state of Israel,” and is written in bold in reference to the forced migration – a result of the first Arab-Israeli war of 1948–1949. “At the same time, they caused nearly a million Arab refugees to flee the occupied territories. Since then, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians (bold is originally in the textbook) have been living in refugee camps in various countries in the region” (Stola, 2012, p. 182). The reduction of Palestinians as a separate ethnic/national community to refugee status is characteristic of some other history textbook narratives as well. The adjective “Palestinian” appears in the last sentence of the passage “The rise of the State of Israel,” in a phrase: “a Palestinian problem.” “The peace process made it possible to improve Israel’s relations with its neighbors, but hopes for a peaceful solution to the Palestinian problem were not fulfilled” (Stola, 2012, p. 183). From this fragment it can be indirectly concluded that the improvement in external relations was not accompanied by an improvement in the internal situation. However, the internal “Palestinian problem” is not addressed from the perspective of the “problematic” inhabitants of the area – the Palestinians themselves. An ultimate failure to notice indigenous Palestinian Arab losses and the focus on Israeli achievements appear in the sentence summarizing information from the chapter: “The State of Israel fought a series of victorious wars with its Arab neighbors, defended its existence, and took (pol. zajêło) the West Bank and Gaza Strip” (Stola, 2012, p. 186). Palestine is a territory without Palestinians also in the introductory, pro-Israeli fragment, and highlighting their national liberation: “After nearly 2,000 years of living in exile and a few years after the Holocaust, the Jews created their own state, but the Arab leaders rejected the division of Palestine and did not recognize Israel” (Stola, 2012, p. 182). In the second part of the sentence the “Palestinian-blindness” is once again apparent, and the conflict is visualized as a clash between “Arab leaders” and the newly formed state of Israel. Five of six textbooks analyzed fail to recall to the students the perspective of the local, quantitatively dominant Arab native population.

The last chapter of the struggle in the Middle East, taking place since the 1990s, is only signaled in the passage about the United States as the only superpower: “American supremacy has its opponents. The most furious turned out to be radical Muslim organizations (bold original in the text), whose leaders hate the United States, especially for their support for Israel” (Stola, 2012, p. 227). The use of emotional language (adjective: “furious,” pol. zażarty; and verb: “hate,” pol. nienawidzą) is not the only dissonance in the narrative. Another, more serious one is the non-recognition in the text of a Palestinian national entity. The textbook does not provide students with any information about the Palestinian National Movement. There is no reference made either to the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) or its longtime Chairman, Yasser Arafat. The Palestinian self-determination process is not discussed at all and students are left with a one-sided, Western-centric view limiting their understanding of the conflict.

Unlike in the PWN textbook, where the designation “Zionists” and the term “Zionism” do not appear at all, the WSiP textbook puts the movement in the spotlight. Interestingly, the textbook uses the adjectives “Jewish” (pol. Żydowski), but – surprisingly – the designate “Jews” (pol. Żydzi), present in all other textbooks analyzed, is not used in WSiP textbook. The opponents in the Middle Eastern conflict are – in the first phase (before 1948) Zionists vs. Arabs, and later Israel as a state vs. the Arabs as a single, collective entity. The focus on Zionists as being the main protagonists appears already in the description of the early stage of the Jewish settlement in Palestine: “Palestine has become a big problem for Great Britain. Ruling in this former Turkish province from 1918, the British promised the Zionists that they would create a Jewish national home there” (pol. translation for the Jewish national home is “żydowska siedziba narodowa”) (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284). As we read further, after the Second World War, when Britain withdrew its troops, “the Zionists proclaimed the establishment of the state of Israel” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284).

The repeated reference to Zionism in the textbook directs students’ perception to the ideological and political nature of the Israeli state project.2 It is also the only textbook that explicitly emphasizes the perspective of European (Western) colonialism: “The Jewish colonization of the Holy Land sparked resistance from the Arabs who repeatedly triggered anti-Jewish riots” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284). The use of the biblical phrase “the Holy Land” not only emphasizes the religious dimension of the dispute, but represents a “Western” point of view as a symbolic denotation of the Middle East in Western civilization. However, the textbook narration represents Jewish (Western) immigration as an illegal and hostile foreign intrusion: “Transports of illegal immigrants were reaching Palestine, and armed Jewish troops (a military expression used in the textbook: pol. oddział) were attacking British posts” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284–285).

The entire textbook narrative of the conflict is based on an ill-matched opposition: a state vs. a broad ethnic, religious and cultural group. As in the previous textbook, Palestine is shown as a geographic territory but without the Palestinians: there are “Arab inhabitants” in the disputed territory. The narrative presents Israel as a victorious invader, emphasizing its strengths (better organization and strong determination) and its ability to overpower the indigenous population: “Israel forced most of the Arab inhabitants to flee from the lands it had taken. The problem of their right to return home is still one of the factors hindering the achievement of a Jewish-Arab agreement” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284).

Despite such an open emphasis on the rights of the native population forced to leave their country, this narrative cannot be described as pro-Palestinian. Similarly to the previous textbook, the PLO as a representative of the Palestinian people is not mentioned. The name of its famous leader, Yasser Arafat, appears in short, one-sentence reference to the wave of refugees that gave rise to the unmentioned Palestinian national liberation movement. The adjective “Palestinian” appears in a general phrase: “Many Palestinian political and terrorist organizations were established in the refugee camps, including Fatah (Palestinian National Liberation Movement) led by Yasser Arafat” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 284). There is no information in the textbook that Fatah maintains a leading position in the PLO and is the largest faction of this ideologically diverse, multi-party organization. The adjective “Palestinian” appears for the first and only time in the context of refugee camps; implicitly “Palestinian identity” emerges in exile; earlier in the narrative there are only “Arab inhabitants forced to flee.”

In the last section of the chapter “The World After World War II,” entitled “Terrorism,” one sentence confirms Israel’s recognition as an integral part of the Western world, standing in opposition to Islamic terrorism: “Al-Qaeda has declared jihad – a holy war against the United States, Israel, and all influences of Western civilization in the Muslim world. (…) Due to the rapidly increasing number of Muslims in developed countries, Islamic terrorism has become one of the major threats in the modern world” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 290).

From the Initial “Arab-Israeli” to the Subsequent “Israeli-Palestinian” Conflict

In the third textbook by Operon which was analyzed, the narrative on the conflict again begins with the two main protagonists: Jews, representing Jewish state (pol. państwo żydowskie), and Arabs, representing a heterogeneous group of “Arab states” (państwa arabskie). The Operon textbook opens with a balanced sentence presenting the Jewish perspective on their national self-determination by using of the unbiased and agreeable wording of “return” and “reestablishment”: “The Jewish-Arab conflict began in the 19th century, when the Zionists began formulating slogans of returning to Palestine and reestablishing the Jewish state” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 41). The reference to Zionism is not excessive and vilifying. On the other hand, the textbook tries to use non-confrontational rhetoric in addressing the Arab side, e.g., by replacing “attack” – the word used in other textbooks – with an euphemistic “armed crossing of the border,” pol. zbrojne przekroczenie granicy: “The establishment of the Israeli state provoked opposition from the Arab countries associated in the League of Arab States. They did not recognize the founding of the new state and on the same day (May 15, 1948) they made an armed crossing of the border of Israel” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 41). Again, however, the presence and internal opposition of the native population, the Palestinian Arabs, is disregarded; the opposing side is the external Arab League.

Unlike the analyzed textbooks mentioned previously, Operon goes beyond this overgeneralization and shifts the textbook narrative from the initial “Arab-Israeli” to the subsequent “Israeli-Palestinian” conflict. It shows the transition highlighted by Alan Dowty who traced the evolution of the conflict and delineated its four key stages. At the turn of the 1980s a previous conflict between the state of Israel and its neighboring Arab states evolved and Palestine gradually reasserted its central place. The textbook gives the exact account of this change of perspective: “From the beginning of the 1980s, the situation in the Middle East was dominated by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 43).

Similarly to the previous textbooks, the designation “Palestinians” appears for the first time in the context of their exile. The refugee experience symbolically “labels” the Palestinians as a distinct ethno-national group. “The situation of one million Palestinians who took refuge in the refugee camps in Arab states was a source of unrest” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 42). However, what distinguishes the material analyzed from the two earlier textbooks is the clear presence of narratives about the Palestinian resistance movement. While the first one is completely silent and the second one contains a single reference to Y. Arafat, the Operon textbook describes the activity of the Palestinian leader, attaching a large portrait photo to his biography. The political victories of the organization he founded are listed, including recognition of the PLO by the United Nations in 1979. The narrative is objectified, factual, and impartial, for example in the passage: “The Palestinian Liberation Organization representing interests of about 5 million of stateless Palestinians living in Arab countries” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 43).

An important feature of the final Operon textbook passage on the conflict is the agency identified on the Israeli-occupied Palestinian side: “In the Jewish-occupied territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, a Palestinian uprising called the intifada (“war of stones”) began in 1987” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 44).

The textbook presents the Palestinian perspective, giving students access to reflect on the right of Palestinians to national self-determination. The narrative refers to all the facts, including the description of the hostile involvement of Hamas and Hesbollah – anti-Israeli terrorist organizations – in the conflict. Two large photos of the same size (one third of a page each) illustrate the events following the Palestinian uprising of 1987 (Burda et al., 2012, p. 43–44). The first one shows the armed and masked Hamas fighters marching with flags and shoulder-fired missile weapons; the second one shows the street densely covered with debris and stones and two groups facing each other: young men throwing stones and armed soldiers with weapons, shields, and helmets. The juxtaposition of these photos visualizes the multidimensionality of the Palestinian national liberation struggle.

There is an attempt to maintain balance between “competing narratives” and present both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian views of the conflict. The textbook highlights the breakdown of the Middle East peace process as a result of Jewish settlement activity on the occupied Palestinian land: “The peace process in the Middle East was interrupted in 1997 due to the policy of Prime Minister Benjamin Natanyahu supporting Jewish settlement in the territories occupied by Israel” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 44). The textbook does not mention that Jewish settlements have been considered illegal under international law by the United Nations3; it does not bring forward the Palestinian narrative of the colonial model of Israeli settlement policy either. The information that follows about Palestinian terrorist organizations and the questioning of the legitimacy of Israel’s statehood by the Palestinian side appears as a counter-argument which helps to understand the Israeli position and to see Israel’s decisions as a retaliation against terrorist acts. In the same manner, the use of the term “anti-Palestinian provocation” (Burda et al., 2012, p. 44) as a trigger of the second intifada in 2000 is another attempt to recognize the genuine experience of Palestinians. The section ends with information on the establishment of the Palestinian Authority. Thus, the textbook narrative gives voice to the perspective of the Palestinian struggle for national liberation and independence.

Palestinian Arabs – A Clear Ethno-National Distinction

In the NOWA ERA textbook the main protagonists – Arabs and Jews – are named in the first sentence of the chapter “Conflicts in the Middle East” section: “The rise of the state of Israel”: “In Palestine, administered by Great Britain after World War I (as mandated territory of the League of Nations), the Arab-Jewish conflict intensified” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 166). The narrative refers to the Balfour Declaration as the most important document announcing the rise of “Jewish national home,” and “Zionist groups seeking to establish a Jewish state in the Holy Land – in the place where it existed 2,000 years ago” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 166). The religious dimension of the clash between Arabs and Jews is indirectly highlighted not only by the phrase about the return to the “Holy Land,” but also by the use of a reference not appearing in other textbooks: “the opposition of the local Muslim population”; previous textbooks usually speak of “Arab opposition” at this point. Again a dominant narrative pattern appears: national liberation of Jewish people and their return to the historical territory after 2,000 years in exile. Similarly to WSiP and OSP Oświatowiec, here also appears the term “Jewish national home” as a symbol of the right of the Jewish people to rebuild their homeland. In the context of national liberation, emphasis is placed on the heroic effort of the Jewish pioneers – the new citizens so needed by Israel “surrounded on all sides by hostile Arab countries” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 166). Interestingly, the hostility from the native Palestinian Arab population is not mentioned. Instead, the perspective of facing the unwelcoming land is highlighted: the Jewish settlers are challenged by poor economic potential and lack of resources. Thanks to their own efforts, but also – as the textbook narrative emphasizes – “enormous help from the Jewish Diaspora” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 167), they manage to initiate an unprecedented socio-economic and political development of Israel. The modernization is presented as the success of the heroic Israeli society. Even the description of the attached photo presenting David Ben-Gurion pronouncing Israel’s Declaration of Independence, May 14, 1948 refers to the modernization and urbanization success of “creating a new national home” by recalling the place where the declaration was signed: the Dizengoff House in Tel Aviv, described in the textbook as “one of the first buildings built in the city” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 167).

The high point of the Eurocentric perspective is the last sentence of the section, where Israel is depicted as a quasi “Western island” in the Middle East, especially in political terms: “Due to these changes, Israel soon became a highly developed state with democratic institutions resembling Western European ones” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 167).

The Palestinian narrative in the NOWA ERA textbook is exceptional; it is the only analyzed textbook that – already at the early stage of the conflict, in the interwar period – makes a clear ethno-national distinction: “The local Arabs, known as the Palestinians, protested against the influx of Jews, which is why the British began to restrict the admission of new refugees in the 1930s. It caused discontent among Palestinian Jews” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 166). This symmetrical approach: “Palestinian Arabs – Palestinian Jews” shows the clash of interests of both groups at the beginning of the conflict as a dispute between the two national movements.

As in the majority of textbooks analyzed, there is a narrative gap as a result of not addressing the issues of the exodus of Palestinians from the land occupied by Israel. Their settling in refugee camps is implicitly noticed, as they appear at a later stage of the narrative as “Palestinian refugees” in the last section entitled “Palestinian conflict at the end of the 20th century.” NOWA ERA is the only textbook that addresses the Palestinian national liberation struggle in such a comprehensive and balanced manner. The revolutionary nature, mercilessness of the fight, and the resulting use of terrorist methods are also emphasized here. The climate after the Camp David Accords of 1978 and the following Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty are described as follows: “The remaining Arab countries stepped up their actions against Israel, primarily by supporting Palestinian refugees who used terrorist methods in their fight against the Jewish state. This type of activity was carried out by the PLO established in 1964 in exile. The PLO intended to fight for the establishment of an independent Palestinian state by all means available, including the use of acts of terror” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 171).

The national liberation struggle was narrated as final and total in both national movements (Israeli and Palestinian), although the extremity of it is more elaborately discussed in relation to the Palestinian side. However, in the section “The rise of the state of Israel” there is a reference to the anti-Arab and anti-British Zionist terrorist organization: the Irgun, operating in the Mandate Palestine between 1931 and 1948: “Britain’s containment of the influx of Jewish immigrants “sparked discontent among Palestinian Jews who formed the Irgun military organization to conduct terrorist activities against the British and Palestinians” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 166).

Yasser Arafat as a leader of Palestinian national liberation movement is described very favorably, especially compared to the Operon biography, which only mentions his role in the creation of the PLO. Here he is referred to as a “devoted Arab nationalist” who not only fought for independence (“the creation of an independent Palestinian state as a result of victory in an armed struggle”), but also undertook diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict peacefully (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 171). The textbook narrative emphasizes conciliation activities, including “leading to the removal of the provision for the necessity to destroy the Israeli state from the PLO’s program declaration” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 171). There are two pivotal moments of his political career mentioned: the Nobel Peace Prize in 1994 (without, however, naming the two other politicians awarded: Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin) and the election for president of the PNA 2 years later.4

The section on the Palestinian conflict in the late 20th century ends with the passage on the 1993 agreement, the declaration of mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO, and Israel’s consent to the “gradual emergence of an independent Palestinian state” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 172). It is further emphasized that this did not lead to an end to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The narrative highlights the persistent, deep division of a religious nature. “The peace treaty, however, was not recognized by the radical Islamic groups Hezbollah and Hamas, which to this day carry out bomb attacks on Israeli cities” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 172). However, similarly to all other analyzed textbooks, the designation “Judaism” does not appear as a religious “counterweight” to the often mentioned Islam – the major source of turmoil in the present Middle East. Nevertheless, the narrative focuses on showing that not only on the Arab side are we dealing with extremity and nationalism: “Agreements with Palestinians are also not accepted by Jewish nationalist groups, which strive to further expand Jewish settlements in territories occupied by Israel” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012, p. 172). The very last sentence concerns Yitzhak Rabin, an Israeli Prime Minister murdered by a “Jewish extremist.” By recognizing both Jewish and Palestinian nationalism perspectives, the NOWA ERA textbook seems to focus on representation of both sides (victim vs. victim) and tries to avoid recriminations.

Palestinian Refugees and Palestnian Terrorists

The STENTOR textbook, similarly to the four other history textbooks analyzed, places Jews and Arabs as two sides of the initial (pre-1948) phase of the conflict. It also introduces an interesting discussion on ethnicity issues in an innovative tool: a textbox called “Historical Forum,” graphically designed to replicate discussions on the Internet. It paves the way to exceed beyond the facts toward opinions, interpretations and to allow emotional language, or even “controlled” bias. One of the “entries” draws attention to the lack of unanimity among the Jews scattered around the world as to the plans to establish a Jewish state and return Jews to Palestine. It points out that the ethnic identity of the Jewish population was only beginning to emerge in the second half of the nineteenth century. “Although there was agreement on the idea of reactivating Israel, the issue of returning to the lands of Palestine, inhabited mainly by Arabs, was less well received.” (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 170). This draws students’ attention to the more complex issue of the claim that the Jews constitute both an ethnic group and a religion – the claim that was necessary to make a territorial claim on “national homeland” – was a relatively new and as yet not widely accepted idea among Jews (Dowty, 2017).

With both text and image (photo of the march of armed men and women, captioned “Israeli society of soldiers”), the STENTOR textbook is the only textbook that points to a social-historical element: the experience of living in a constant struggle and with the ongoing sense of the threat of war that justifies the principle of defense as a primary civic duty and the focus on the Israel’s deterrence capacity: “Being surrounded by hostile Arab states and the presence of a large Arab minority in Israel resulted in a higher than anywhere else in the world degree of militarization of Israeli society” (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 190).

The adjective “Palestinian” comes in two symptomatic phrases. The first is the “Palestinian People” in the context of the post-1948 refugee experience: “After Israel was founded, many Palestinians went into exile. They did not accept the existence of a Jewish state and treated it as a temporary state. They founded many organizations fighting for the establishment of an Arab state in Palestine, some of them adopting terrorist methods of operation” (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 191). Second phrase is the “Palestinian terrorist” in the fragment with a detailed description of the 1972 Munich Olympics Attack on Israeli Athletes: “the action of the group operating within the PLO” (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 192).

Yasser Arafat’s biography in the STENTOR textbook (title: Hero of the Moment: Arafat – the Palestinian Leader) marks his gradual evolution from armed struggle to negotiation as the main method on the Palestinian “road to independence.” An important attempt to maintain a balance and to allow the pro-Palestinian narrative to speak out is the phrase: “promoting the arguments of the Palestinians” (pol. racje Palestyńczyków) (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 294). However, the narrative of the Palestinian liberation struggle in the STENTOR textbook is not complete: it appears in the descriptions of the terrorist activities (the Munich Attack – pol. Zamach w Monachium) and it is expressis verbis mentioned in Yasser Arafat’s biography: “He participated in the Palestinian liberation struggles against Israel” (Brzozowski and Szczepański, 2012, p. 294). The biography indirectly touches upon the institutionalization of Palestinian nationalism: the creation of Fatah and the PLO. However, the next important developmental step of the Palestinian nationalism – the first and the second Intifada, and the civil struggle of Palestinian people – is not elaborated.

The Jewish Settlers and the Arabs Living in Palestine

In the SOP Oświatowiec textbook the protagonists of the pre-1948 stage of the conflict are outlined in the following sentence: “The competition between the Jews and the Arabs living in Palestine has resulted in numerous conflicts” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 13). Although the use of the word “competition” indicates even rivalry for resources and territory, there is no symmetry in the narrative. The textbook presents neither facts, nor numbers on Arab community inhabiting Palestine in the initial phase of Aliyah – a term used in the textbook for the late 19th century immigration of Jews from the Diaspora to the Land of Israel (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 12). Although there is information on the Jewish community rising (1914: 80,000; 1939: 500,000), there are no corresponding numbers concerning the Arab population in that period. The designation “Arabs” appears again in just one additional sentence: “Attempts to introduce the division of influence between Arabs and Jews were unsuccessful” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 13). And again the “Arabs” constitute an anti-Jewish ethnic monolith, without distinction between Palestinians, Syrians, or Egyptians.

The subsection “The Case of Palestine” in the SOP Oświatowiec textbook focusing on the interwar period is narrated from a clearly pro-Israeli perspective. There emerges an admirable picture of the effort to build a new state, and its economic and cultural modernization. The textbook offers a long half-page description of modernization changes, including the establishment of agricultural cooperatives, the development of urbanization, the unification of Hebrew as the state language, and the establishment of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem in 1925. “Large groups of Jews with varied education and social position, led by Zionist organizations, consciously organized the new state” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 13). It reveals a narrative element that Podeh calls the “wilderness thesis”: the description “showing Eretz Israel as empty and underdeveloped, thus “proving” that the immigrants indeed found a desolate country” (Podeh, 2002, p. 80). The symbolic “absence” of Palestinian Arab population and their lack of historical subjectivity is emphasized in a sentence, pointing to the transactional nature of the settlement process – two sides of the transaction being the British and the Jewish settlers: “The British gave permission for Jews to settle in Palestine and for Zionist organizations to buy the land” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 13). The phrase: wydali zgodê na wykup ziemi (“gave permission to buy the land”) is a narrative device to point to The British as actual “possessors” of Palestine. It denounces the Arabs in Palestine as a unreliable party to the territorial dispute.

As in the majority of textbooks analyzed, the SOP Oświatowiec textbook introduces the phrase from the Balfour declaration, later on repeated in Israel’s 1948 declaration of independence: “national home for Jewish people.” It is also one of two textbooks (along with the WSiP textbook) that presents students with the definition of Zionism. However, in spite of Zionists being colonizers, as depicted in the WSiP textbook’s depiction of Zionist colonialism, the definition here does not refer to any elements of Western cultural and economic imperialism. It points to the religious dimension and the unique bond between a land and a people, strengthening an ancestral homeland narrative. Zionism is “the ideology of the national revival of Jews. The name comes from the hill Zion in Jerusalem, on which the temple of Solomon is built – a symbol of the unity of the Jews” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 13). The modern territorial dispensation is shaped by a strong historical and religious connection to the land.

The SOP Oświatowiec textbook is the only one that introduces the new denotation, based on a colonial dichotomy of native vs. settler. Along with “Jewish immigrants” there appear multiple references to “Jewish settlers,” e.g., in the sentence: “Armed clashes between Jewish settlers and the Arab population were more frequent” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 233). The category of settlers as geographical outsiders emerges through movement. The reference of the Zionist settler mechanism is done without referring to the other category in this dichotomy: the native Arab population. The only natives discussed in the textbook are Jews, holding at a different historical moment the position of natives and striving now for “national revival.” The vast majority of the “The establishment of the State of Israel” paragraph was devoted to the state-building struggles of Israel, as well as clearly embedding them in the spectrum of interests of the Western world countries (the decision of the United Nations General Assembly of 1947, the proclamation of the state of Israel in 1948, the armed conflict with “neighboring Arab states,” mentioned without naming the states). The Palestinian perspective is indicated in the textbook in two lapidary sentences: “The consequence of the war was the problem of refugees. Over 600,000 Palestinians have found refuge in Arab states “(Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 234).

The last passage on the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – “Palestinian Authority. Islamic Terrorism” – tries to answer the question of why the creation of the Autonomy did not ensure peace in the Middle East. The reasons are, however, addressed asymmetrically from the start, juxtaposing Palestinian radicalism with “some groups” in Israel – unspecified, but not marked as radical: “The implementation of the Washington Treaty has provoked opposition from both radical Palestinian organizations and some groups in Israel” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 370). Further can be read: “Both sides blamed themselves for provoking tension. Israel maintained and even expanded Jewish settlements in the West Bank. Palestinians undertook terrorist actions, and the Israeli army used retaliatory measures. In 2000, the Palestinians started another uprising” (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 370). The last sentence about the uprising is the only trace in the textbook on the “Second Intifada” – the Palestinian revolt against the Israeli occupation and the period of intensified Israeli-Palestinian violence between 2000 and 2005. Moreover, the phrase “retaliatory measures” used in the context of Israeli army is a semiotic device to build up a legitimizing claim that the force used against the Palestinians was “necessary.” The pro-Israeli nature of the narrative is also indicated by the selection of other expressions, e.g., instead of the phrase “Israel attacked” appearing in other textbooks there is the euphemistic “Israel has begun military operations” (pol. rozpoczął działania zbrojne) used (Kozłowska et al., 2012, p. 262).

Discussion

The over simplistic “aggressor-victim” format is not dominant in the analyzed history textbook narratives. The juxtaposition of an unequivocally unfavorable image of one party with an overly positively distorted image of the other party appears rarely. The one-sided pattern of perception of the conflict is not dominant. Not always successful attempts to find a narrative balance dominate. In most textbooks the conflict is presented in a neutral tone, the use of emotive language in the textbook narrative is present in two of the six textbooks. Most textbooks focus on chronology that may sometimes turn into the decontextualized naming of the selected facts. Three of the six textbooks aim to show students varying interpretations of the conflict. By opening their narratives for discussion they try to escape the intention to “convince” the student to the one “righteous” perspective.

Half of analyzed textbooks fit in with biased preconception about the Arab world as a “single place”; the complexity of Arab world is rarely addressed. The dominant strategy is the compression and over-simplification of the whole region under an umbrella term: “the Arabs.” Even if it is not due to ignorance, the attempt to make the narrative more accessible and less nuanced results in a generalization of the Arab world which affects the students’ perception of the Middle East as a culturally and politically monolithic territory.

The coverage of Israeli-Palestinian conflict in most of the analyzed textbooks is unbalanced, sometimes even misleading and implying asymmetrical relations between Jews (in Palestine) and Arabs (in the Middle East). There is no discussion around the legitimacy of the claim to separate statehood of Palestinians. No textbook mentions that Palestinian nationalists have been active in struggle against Zionism since the early 1920s. Due to the decontextualized fact-naming “the foundation of the Palestinian Liberation Organization in 1964” appears as if without justification. The Palestinian Arab presence in pre-1948 Palestine is disregarded in four of six textbooks. Only two textbooks note the ethno-national difference of the Palestinians at the early stage of the conflict. They make an attempt to construct a narrative that not only acknowledges the Jewish right to national independence, but also the Palestinian right to national revival. They also voice criticism of some aspects of Israeli policy toward native population. The existence of the Palestinian minority in Palestine/Israel is noted only within the exile experience, as if that particular experience transformed the former Arabs into Palestinian refugees. It has also been noticed in other textbooks studies (Osborn, 2017) that displacement is a key identity component when classifying Palestinians as a population. The narrative effect is playing down the existence of the Palestinian national identity. Students get access only to the Jewish (Zionist) national narrative (Nasser and Nasser, 2008).

In five of six textbooks there is a reference to the historical, centuries-old, “biblical roots” of Jews in Palestine (“the return to Zion” narrative). Five of six textbooks highlight the righteousness of Jewish struggle for national revival (historical roots, the Holocaust). The Balfour Declaration is presented in all textbooks as the document of primary importance for the process of establishing the “Jewish national home in Palestine.” The importance of the British promise appears in all textbooks as the foundation of the Israeli State, although it is euphemistically spoken of a “home” rather than a “state.” In spite of the Balfour Declaration being one of several, sometimes conflicting agreements, e.g., between the British and the Arabs (e.g., MacMahon-Husayn correspondence concerning Palestine), the fact of existence of other agreements is omitted in all history textbooks. As a result it is “suggested to the student that the Balfour Declaration was more important than other wartime commitments. While this is certainly the Israeli view, it was not the British or the Arab interpretation” (Podeh, 2002, p. 90). The elements of moral rationalization are also used: the morally questionable acts are counterbalanced and “rewarded” by positive consequences, e.g., the establishment of a modernized, successful, Western-like Jewish state. In four textbooks the Jewish settlement process is moralized by being defined as “a modernization success” and “the region’s recovery from backwardness.” Explicit anti-Israeli rhetoric appears only in one textbook where Zionism is presented as a pure colonial movement and Zionists are the only protagonists present in the textbook narrative on the Establishment of Israel. The complete exclusion of the designation “Jews” from the textbook narrative reduces Israel to the status of a Zionist State and offer students an essentialist and over-simplistic understanding of Jewish community in Israel. Moreover, all textbooks offering the definition of Zionism refer only to the aim of “establishing a national home for Jewish people” in Palestine. As noted by Osborn in his textbook study, in the process of reducing Zionism to a community focused on sovereignty, other concerns of the movements, e.g., the alternative ways of cultivating Jewish identity, were not noticed. “Without these representations, textbooks and teachers imposed narrow parameters on Zionists that veiled the diversity within this subset of Jews” (Osborn, 2017, p. 27).

There is no symmetrical reference to the history/roots of indigenous Arabs in Palestine. An attempt to present the conflict in a more balanced way appears at a later stage, especially after the Lebanese war in 1982. Three textbooks change their initial historical narrative noticing – even if implicitly – the existence of the Palestinian resistance and national liberation movement when referring to its most prominent figure – Yasser Arafat and the institutionalization of Palestinian nationalism in the creation of Fatah and the PLO. However, as formulated by Podeh in her textbook study (Podeh, 2002, p. 93), “the underlying message (…) is that Palestinian nationalism emerged not as a result of an array of geographical, historical, economic, and cultural developments, but entirely as a reaction to Zionism.” The struggle with Zionism may have consolidated Palestinian nationalism, but most textbooks choose to portray the struggle as its only trigger.

The explicit reference to the “Arab nationalism” appears only in two textbooks. They choose the “ethnocentric attitude” that – in case of Israeli-Zionist historiography – is defined by Podeh (2002, p. 89) as a tendency to “ignore, overlook, or diminish the importance of major developments in the Arab world.” No analyzed Polish history textbook chooses to distinguish the Arab nationalism from the Palestinian nationalism. In fact, the latter – being non-existent in the historical textbook narrative – becomes “submerged under Arab nationalism” (Podeh, 2002, p. 92). Caught in a vicious circle, Palestinian nationalism is dismissed as ephemeral and of recent origin mainly due to the lack of sovereignty of Palestine as a nation-state (Khalidi, 2010).

The religious dimension of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is – until 2001 – not discussed. The issue of religious diversity in Palestine is excluded in all textbook descriptions. Without any reference to Judaism or Islam in the pre-2001 era, the conflict is initially presented as a clash between two rival civilizations, and not religious communities. In the textbook narratives of the post-2001 period Islam (most commonly “radical Islam”) is mentioned only in relation to terrorism. Three textbooks stereotype Palestinians as “terrorists” and – by highlighting Israel’s right to defend itself and initiate “retaliatory actions” (pol. działania odwetowe) – place Israel as a victim of Palestinian “aggression.” Israel is depicted as a “defender” whose preemptive attacks are legitimized as a response to external aggression. Two textbooks openly juxtapose Palestinian nationalism with Islamic terrorism. They explicitly merge the last chapter of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with the rise of fundamentalism/Islamism. Both labels are often used interchangeably and without providing explicit definitions. Textbooks do not clarify for students the various tendencies within Islamism as a non-monolithic religious ideology. As summarized by Mozzafari (2007, p. 25), the divergent nature of Islamism is summarized “around two axial pillars: division determined by sub-religious affiliations (Sunni, Shi’a, and Wahhabi), and division emanating from the diverse scope of claims and ambitions (national and global Islamist groups).” Similar way of depicting Palestinian liberation movement as terrorism was noticed in other textbook studies (Osborn, 2017), where – instead of differentiating actions of the secular nationalist PLO from those of other more religious organizations – they effectively entangle “disparate actions perpetrated by dissimilar organizations into a purportedly cohesive movement of Islamic terrorism” (Osborn, 2017, p. 22).

The discussion of the anti-Western movements in the context of Israeli-Palestinian conflict should include the differentiation between the global and the national; between Hamas and Hezbollah, and other, secular Palestinian movements like the PLO and Fatah. The latter tend to present the conflict as the one between Israelis and Palestinians, whereas Hamas or Hezbollah formulate it as an Islamic struggle against world Zionism (Mozaffari, 2007, p. 27).

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is narrated as a story of wars, armed struggle and acts of aggression, and half of the analyzed textbooks present these military struggles as symmetrical. Three of six textbooks mention Intifada, but only two refer to the harm and injustice of the unequal position of both sides by juxtaposing civilian rioting against the efficiency of a highly militarized army. There is also very little narrative space devoted to the issues of conflict resolution and peace process. With half of textbooks analyzed focusing on conflict as inherent and presenting peace attempts as futile, the students do not get the chance to be confronted with history that would educate for peace and promote conflict resolution. The last missing element of the narrative in all textbooks is the lack of discussion of the Western dominance in the Middle East, especially from the post-colonial perspective of the Arabs and Muslims’ continuous struggle with imperialism. There is no reference in any of the textbooks to the exceptional dynamic between Islam and globalization (aka Westernization) that helps explain the position of the Middle East (and Palestine in particular) as “the one world region where anti-imperialist nationalism, obsolete everywhere, remains alive and where indigenous ideology, Islam, provides a world view still resistant to West-centric globalization” (Hinnebusch, 2003, p. 15). The inclusion of this “Western dominance” discussion would allow going beyond the decontextualized and depoliticized inevitability of the war between East and West. A colonization perspective would help understand the “irresolvable” nature of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It is however promising that half of textbooks analyzed escape the narrative of absolute truth and try to introduce a “divided narrative” where either side is right and either side is a victim. There is an inspiration coming from Edward Said’s suggestion to look critically “at the Arab environment, Palestinian history, and Israeli realities, with the explicit conclusion that only a negotiated settlement between the two communities of suffering, Arab and Jewish, would provide respite from the unending war” (Said, 1994, p. 338). Critical historical thinking is a pedagogical model based on the idea of students developing an understanding of ambiguity of historical evidence and striving to deliberate over historical questions, especially whose that remain unresolved. Bringing non-standard interpretations and presenting opposing points of view on historical facts is the purpose of multi-perspective history teaching. Its most decisive element is the way educational politicians cope with the trap of temporariness and arbitrariness, and “whether a country and government feels mature enough to afford the “luxury” of teaching a multi-perspective history to all or whether political institutions see voices diverging from their own narrow ideology as a threat” (Wagner et al., 2018, p. 45). Students should have a chance chance to move beyond glorified and axiomatic narratives and develop “an informed citizenry that is capable of critiquing official/marginalizing knowledge while promoting equity as agenda of social justice” (Blevins et al., 2015, p. 73). Critical minded history learners of today will become the critical minded citizens of tomorrow.

Author Contributions

DH-W contributed to conception and design of the study, wrote all sections of the manuscript, and as well as contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved its submitted version.

Funding

The publication is going to be funded with the AMU Faculty of Educational Studies grant.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Dowty points here to an important narrative difference – describing the core issue using contrasting reasoning. On one side there are pro-Israeli voices that “argue that the basic cause of the conflict is the refusal of Palestinians and other Arabs to acknowledge the existence and legitimacy of a Jewish state in the historic Jewish homeland” (Dowty, 2017, p. 4). On the other side there are pro-Palestinian voices that stand against “the violation of the natural right of the Palestinian people to self-determination in its ancestral homeland” (Dowty, 2017).

- ^ The direct and repeated reference to Zionism, completely absent from the previous PWN textbook, is accompanied with the source material added at the end of the chapter: a long fragment of the “Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel.” Tasks for students include identifying in the source text the arguments justifying the establishment of Israel (primarily, the link between the people and the land) and finding a figure considered to be the founder of Israel: the answer is: “the father of modern political Zionism, Theodor Herzl” (Dolecki et al., 2012, p. 291).

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 2,334 from 23 December, 2016. The textbook refers to the earlier international (UN) pressure on Israel because of the illegal nature of the annexation of territories in 1967, as well as its consequence: the inability to end the armed conflict.

- ^ The bio ends with a speculative theory about the cause of death of the Palestinian leader, a hypothetical statement that does not appear in any other textbook analyzed: “One hypothesis was that he might have been poisoned with radioactive polonium by the Israeli secret service” (Kłaczkow and Zielińska, 2012). It exemplifies a very rare example of pro-Palestinian bias, especially taking into account the fact that the textbook does not provide the source of the hypothesis (a forensic report obtained by Al Jazeera from the Institute of Radiation Physics at the University in Lausanne in Switzerland) and does not discuss the context and reasons for this possible political assassination. Even the media coverage choose their words on this delicate topic very carefully saying that the Swiss scientists “are extremely cautious about their findings” (see BBC, 2021).

References

Apple, M. W. (1993). Official Knowledge: Democratic Education in a Conservative Age. New York, NY: Routledge.

BBC (2021). Yasser Arafat ‘May have been Poisoned with Polonium’. Available Online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-24838061 [accessed November 5, 2021].

Berger, P. L., and Luckmann, T. (1967). The Social Construction of Reality. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Blevins, B. E., Salinas, C. S., and Talbert, T. L. (2015). “Critical historical thinking. Enacting the voice of the other in the social studies curriculum and classroom,” in Critical Qualitative Research in Social Education, ed. C. White (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 71–90.

Brzozowski, A., and Szczepański, G. (2012). Ku Współczesności. Dzieje Najnowsze 1918-2006. Podrêcznik do Historii dla Klasy I Szkół Ponadgimnazjalnych. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Piotra Marciszuka Stentor.

Burda, B., Halczak, B., Józefiak, R. M., Roszak, A., and Szymczak, M. (2012). Historia. Czêść 2. Historia Najnowsza. Podrêcznik dla Szkół Ponadgimnazjalnych. Gdynia: Wydawnictwo Pedagogiczne Operon.

Caplan, N. (2020). The Israel-Palestine Conflict: Contested Histories. Hoboken, NJ: John Willey & Sons.

Crawford, K. A., and Foster, S. J. (2008). War Nation Memory: International Perspectives on World War II in School History Textbooks. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Dolecki, R., Gutowski, K., and Smoleński, J. (2012). Po Prostu Historia. Szkoły Ponadgimnazjalne. Warszawa: Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London: Routledge.

Gulliver, T. (2010). Immigrant success stories in ESL textbooks. TESOL Q. 44, 725–745. doi: 10.5054/tq.2010.235994

Hildebrandt-Wypych, D. (2017). “Religious nation or national religion: Poland’s heroes and the (Re) construction of national identity in history textbooks,” in Globalisation and Historiography of National Leaders: Symbolic Representations in School Textbooks, eds J. Zajda, T. Tsyrlina-Spady, and M. Lovorn (Dordrecht: Springer), 103–121. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0975-8_7

Hildebrandt-Wypych, D. (2021). “Religiously framed nation-talk in polish history textbooks: Jahn Paul II. And St. Jadwiga as national heroes,” in Comparative Perspectives on School Textbooks. Analyzing Shifting Discourses on Nationhood, Citizenship, Gender, and Religion, eds D. Hildebrandt-Wypych and A. W. Wiseman (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan), 289–323. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-68719-9_13

Hinnebusch, R. (2003). The International Politics of the Middle East. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Jewish Voice for Labour (2021). Textbooks Altered Line by Line at UK Lawyers for Israel’s Behest. Available Online at: https://www.jewishvoiceforlabour.org.uk/article/textbooks-altered-line-by-line-at-uk-lawyers-for-israels-behest/ [accessed November 5, 2021].

Khalidi, R. (2010). Palestinian Identity. The Construction of Modern National Consciousness. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.