- 1School of Education, University of Roehampton, London, United Kingdom

- 2UCL Institute of Education, University College London, London, United Kingdom

COVID-19 has had substantial impact on children’s educational experiences, with schools and educators facing numerous challenges in adapting to the new reality of distance learning and/or social distancing. However, previous literature mostly focuses on the experiences of families [including families of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND)] and those of teachers, predominantly working in mainstream settings. This article aims to gauge the perspectives of educators working in specialised education settings that serve children with SEND in England on how they experienced working in those settings during the pandemic, including in during lockdown. A mixed (qualitative and quantitative) online survey was responded to by 93 educators. Responses denote emotionally charged views and a sense of learned helplessness. Most special schools were unable to implement social distancing measures in full or provide adequate protective equipment. The main challenges the respondents mentioned included lack of guidance from Governmental authorities, staff shortages, work overload, challenging relationship with parents and issues in meeting children’s complex needs. Professionals working for less than 3 years in a special school were more likely to say they would change jobs if they could, when compared to professionals with more years of experience. No effects of demographic characteristics were found in relation to professionals’ ratings of their own wellbeing during lockdown. Findings are discussed in light of the concept of learned helplessness and suggest that there is a need to reform provision in special schools in England to foster its sustainability and positive outcomes for children.

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial impact on educational experiences, worldwide, and from a variety of perspectives. Children, families and professionals have all reported significant challenges faced during the pandemic. From March 2020 several countries announced school closures, with teachers and families as well as other professionals involved in the education of children having to adjust to the reality of home-schooling, e-learning, and tele-consultations (e.g., Canning and Robinson, 2021; Thorell et al., 2021). There is consensus that the educational experience of children has been affected, with substantially increased impacts on those who are disadvantaged, either due to their socio-economic circumstances or due to having special educational needs and/or disabilities (SEND; Andrew et al., 2020; Crawley et al., 2020). The experience of families of children with SEND has been relatively well documented, internationally. In England, for example, Sideropoulos et al. (2021) reported enhanced anxiety levels of both parents and children with SEND, as perceived by the parents. Similar results have been observed in parents of children with SEND in India (Dhiman et al., 2020) and in Italy (Montirosso et al., 2021), for instance. Castro-Kemp and Mahmud (2021) who also surveyed parents of children with SEND in England, reported that school closures had a detrimental effect on parents’ mental health and wellbeing and that of their children, particularly in the most deprived families. This is in support of earlier studies that have also denoted the difficulty in implementing specialised services and resources for children with SEND during the pandemic (Andrew et al., 2020; Crawley et al., 2020). International evidence suggests that experiences of parents of children with SEND throughout the pandemic are somewhat dependent on the child’s type of need, denoting the role of cumulative risk (Andrew et al., 2020; Castro-Kemp and Mahmud, 2021).

There is some evidence of the difficulties faced by teachers in mainstream schools. For example, Warnes et al. (2021) looked at mainstream teachers’ concerns about special educational needs, with the highest level of concern reported as lack of resources, specifically, funding for specialist and support staff and appropriate infrastructure. This could lead to the assumption that specialised education settings might have been less affected by these challenges as they already possessed more appropriate resources for these children pre-pandemic. Other studies have referred to the challenges of adapting to online teaching, the lack of preparedness of staff and the need to think about the future for faster adaptiveness to changes in teaching methods (Greenway and Eaton-Thomas, 2020; Steed et al., 2021). However, scarce evidence is available on how these settings have dealt with the challenges posed by COVID-19, with extant studies being small-scale in nature (e.g., Crane et al., 2021; Lukkari, 2021; Middleton and Kay, 2021; Sayman and Cornell, 2021). This seems particularly important in England, where the number of children with SEND attending specialised settings as well as the number of special schools has been rising year on year since 2017 (Department for Education, 2021). Special needs settings were already exposed to a number of pressures in the pre-pandemic times including high staff turnover, increased paperwork and lack of training of paraprofessionals. Furthermore, children with SEND attending specialised settings in England are normally those who present more marked functioning difficulties requiring specialist resources and cooperation with other sectors, parents of children with multiple disabilities, for example, reportedly preferring provision in specialised settings (Shaw, 2017). These children are more likely to be in receipt of statutory support (Education, Health and Care plans) (Department for Education, 2021) and therefore, these settings require staff to be involved in a number of statutory assessment and intervention procedures that they are accountable for. Communication with parents of children with SEND has also been referenced as a key issue for effective practice, even in pre-pandemic times (Shelden et al., 2010; Azad and Mandell, 2016). It is important to understand how these factors may have been influenced by the events of 2020 and how they have affected the views of staff about their profession, wellbeing and quality of the service they provide. This article aims to gauge the perspectives of education staff working in specialised education settings that serve children with SEND in England on how they experienced working throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, with the view of informing future policy and practice. To this end, two research questions were formulated: (a) How have professionals working in specialised education settings in England dealt with the challenges of provision throughout the COVID-19 pandemic? (b) Do individual characteristics such as professional role, years of experience and geographical location of the setting influence professionals’ perceived wellbeing and satisfaction with current job?

Materials and Methods

The study adopted an online survey design with both closed and open-ended items. This exploratory quantitative design performed with a cross-sectional study allowed for data collection from a relatively large sample of participants, enabling statistical analysis of responses and identification of trends, while also allowing for in-depth explanations from the respondents on their ratings.

Sampling

The study adopted a convenience sample, in England. Contacts already established by the authors as part of their ongoing network of research collaborations within the community of interest were approached. These extend throughout the whole country (although the majority are based in Greater London and the Southeast of England), and include some communities within the Special Educational Needs field that are particularly active on social media. Email contacts were made with these communities to invite dissemination of the survey and participation where applicable. Participants responded to the survey in Spring 2021, when COVID-19 cases in England were decreasing significantly and an exceptionally successful vaccination programme was taking place. This followed a strict lockdown period of several months when many schools were closed. The aim was to achieve the maximum number of responses nationally, within the period of the survey between January and April 2021.

Survey

The survey was designed to be distributed and responded on the web via Qualtrics software. It included a set of demographic and categorical items (professional role – open text, years working in the setting – five options, years working in SEND – five options, years working in schools – five options, and region – open text), and closed multiple-choice categorical items, followed by open-ended questions requesting a justification for the ratings. The items were developed based on the recent literature on educational experiences during COVID-19, and the survey was piloted with three trainee Special Educational Needs Coordinators (SENCOs). The pilot test of the survey contributed to ensure the questions could capture a range of experiences. Some of the suggestions made by the trainee SENCOs included the addition of more options as categories for multiple choice questions and rewording of some items. Following demographic information, items agreed with pilot respondents (and in addition to the demographic questions) were: Did your school remain open during the March 2020 lockdown? (categorical variable with three options); Did you continue working in your school during the March 2020 lockdown? (categorical variable with three options); Did your school implement any social distancing measures in your school at that time? Which ones? (open text); Have you been able to keep social distancing measures in your school? (categorical variable with four options); In July 2020 the Government provided full guidance for special schools about re-opening safely in COVID-19 times. What is your view on this guidance? (categorical variable with four options); Did you receive Health and Safety risk assessment updates by your local authority regarding the children that attend your school? (categorical variable with three options); Have you been able to use Personal Protective Equipment? Please tell us why (categorical variable with three options and open text); Please tell us what you think are the main challenges were faced by special settings during the pandemic (open text); How would you rate your overall psychological wellbeing this academic year? (categorical variable with four options); If you could leave your job now, would you? (categorical option with three options); Please leave any other comments that you feel are important for us to consider in trying to understand how special settings are coping with the pandemic (open text). The survey took approximately 10–15 min to respond, and its brief and user-friendly nature was praised by the participants in the pilot.

Data Analysis

To address the first research question, descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic and test variables. Additionally, thematic content analysis was performed on open-ended questions. This consisted of inductively looking for patterns of content in the answers provided, and coding those patterns within common themes (Creswell, 2012; Guest et al., 2014). As the answers provided were relatively short, only one layer of coding was performed. Every statement in the participants’ responses expressing a unit of meaning was included in a category. Various iterations of clustering meaning units into common categories were performed until a set of categories was reached that consensually provided a fair picture of the themes covered by the respondents. This was discussed between the two authors until consensus was reached.

To answer the second research questions and obtain the predictive value of the demographic characteristics under study, namely professional role, years of experience and geographical location of the schools, and professionals’ perceptions, a series of logistic regression models were run. This approached enabled the identification of the likelihood of certain demographics explaining change in perceptions of the pandemic and lockdowns. All variables of interest were recoded into fewer categories to ensure a minimum of 5% of cases in each cell of the double entry chi-square table for logistic regression analysis.

Ethical Issues

The survey was designed to be completely anonymous to the research team. Although the survey was disseminated within the team’s research network, the team did not have access to any names of respondents, their schools and were unable to identify them in any way, or traced them back. This implies that the participants consented with their responses being used in an aggregate format, even if they withdraw from the survey before completing, as per the consent form included in the survey via an online informed consent form, signed prior to starting the response. This was in accordance with the ethics procedures agreed with and approved by the University of Roehampton’s Ethics Committee.

Findings

This article aims to voice the perspectives of education staff working in specialised education settings serving children with SEND in England on how they experienced working in these settings throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The following sections describe the findings resulting from the mixed survey conducted to professionals who worked in specialised settings in that period, in England, and address the two research questions formulated.

Participant Characteristics

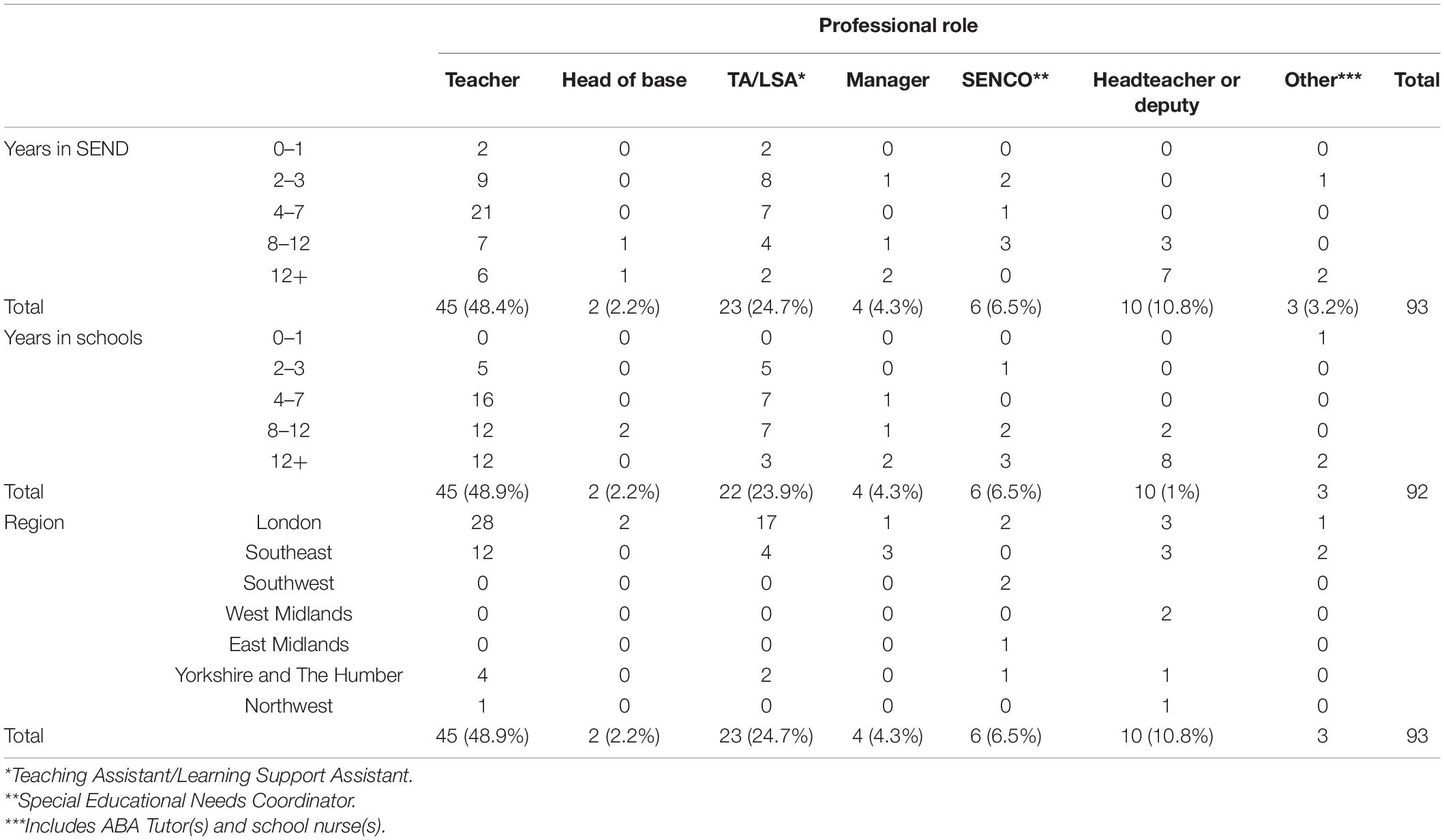

A sample of 93 education staff responded to the survey in full, from special education schools or from specialised units within mainstream schools. Table 1 shows participant characteristics. The majority classified themselves as teachers (n = 45, 48.4%), followed by Teaching Assistants/Learning Support Assistants (n = 23, 24.7%), Headteachers or Deputy Headteachers (n = 10, 10.8%), Special Educational Needs Coordinators (SENCOs) (n = 6, 6.5%), Managers (n = 4, 4.3%) (includes Business Managers), other roles (n = 3, 3.2%), including Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) tutors and school nurses, and two Heads of Base (2.2%), who manage a unit within the school.

Table 1. Participant characteristics per role, years of experience in SEND, years of experience in schools and region where school is based.

Most participants have worked in the setting for less than a year (n = 45, 48.4%), followed by those working in the setting for 4–7 years (n = 37, 39.8%), 8–12 years (n = 8, 8.6%), and only one professional had worked in his/her setting for more than 12 years (1.1%). However, in terms of years of experience working in special education, 29 staff (31.2%) had 4–7 years of experience, 21 (22.6%) had 2–3 years, 20 (21.5%) more than 12 years, 19 (20.4%) 8–12 years, and only 4 (4.3%) less than a year, demonstrating considerable experience in the field. Moreover, staff were mostly experienced in working in schools: 30 (32.2%) had worked in schools for more than 12 years, 26 (28%) for 8–12 years, 24 (25.8%) for 4–7 years (24%), 11 (11.8%) for two to three and only one (1.1%) was starting their career in a school that year. In terms of geographical distribution, most respondents were from Greater London (n = 54, 58.1%) and the Southeast (n = 24, 25.8%), but the sample also included responses from staff working in Yorkshire (n = 8, 8.6%), West Midlands (n = 2, 2.2%), Northwest (n = 2, 2.2%), Southwest (n = 2, 2.2%), and one from East Midlands (1.1%).

How Have Professionals Working in Specialised Education Settings in England Dealt With the Challenges of Provision Throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Most of the survey’s respondents reported that their setting remained partially open during the first national lockdown in 2020 (n = 71, 76.3%). Five participants (5.4%) reported that their settings had closed and 6 (6.5%) that the setting was fully open. When asked if they had continued working at school throughout that national lockdown, most reported that they had a mixed approach of working at school and from home (n = 43, 46.2%), 21 (22.6%) worked at school only as usual and 10 (10.8%) worked from home only.

Participants were asked in an open-ended item which social distancing or protective measures had been implemented by their setting in the period relative to the first national lockdown in 2020. Seven of them responded that no social distancing/protective measures had been implemented in their setting, or that this happened “only on paper” (participant number 10). Others mentioned a few measures, the most frequent being the use of “bubble” groups, keeping 2 m apart “where possible,” reduced timetables, working 1 to 1 with children, encouraging hand washing and sanitising and use of masks and personal protective equipment (PPE). However, participants also mentioned that this was not always possible because it was “very difficult to maintain social distancing with pupils (…) due their needs” (e.g., participant 42); “Students require hands-on support, some rooms are not big enough” (participant 1); “Due to the nature of the pupils needs, maintaining social distancing is near impossible. May require close proximity interaction by staff for their emotional well-being and ability to participate in learning objectives” (participant 3); “Our students struggle to understand social distancing and some of them need physical touch to help manage their anxieties” (participant 22).

When asked to rate whether they had been able to keep those social distancing and protective measures at school, 45 (48.4%) responded “not much” and 13 (14%) “not at all” (representing the majority of the sample), while 19 (20.4%) responded “yes, somewhat effectively” and 5 (5.4%) said “yes, very effectively” (the latter including a variety of roles: 1 teacher, 1 TA/LSA, 1 SENCO, 1 Headteacher/Deputy, and 1 in “other” role).

The survey asked about the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), with 45 (48.4%) respondents reporting they used it, 10 stating they had not (10.8%) and 25 (26.9%) saying they sometimes had. Of those who said they used PPE, many supported the costs themselves; for example:

“I bought my own masks and visors that suited my needs. We are able to wear them all day. School have provided gloves” (participant 1).

“But I paid for it myself. The things the school provided were uncomfortable” (participant 5).

The survey asked participants to rate the helpfulness of the Government’s guidance for special schools about re-opening safely in COVID-19 times; the most frequent response was that this was “somewhat helpful” (n = 40, 43%), but 21 (22.6%) said this was “not helpful at all,” 19 (20.4%) were not aware of any guidance and only two (2.2%) referred to this guidance as “very helpful.”

Regarding safety risk assessment updates sent by the Local Authorities to schools, 30 respondents reported to have received them, 12 (12.9%) said they had not, five (5.4%) reported they had received some updates, but 35 (37.6%) were unsure whether this had happened.

We asked respondents how they rated their overall wellbeing throughout the pandemic. 44 (47.3%) said “it has been hard” and eight (8.6%) stated “it has been very hard and I don’t feel that I am coping well”; only six (6.5%) said “Actually, I feel fine” and 22 (23.7%) reported that there were “Ups and downs but have been coping.”

To better understand their ratings, we asked through an open-ended question what main challenges they thought specialised settings faced during the pandemic. The most common themes were: (1) lack of support from local authority and/or other governmental authorities (of the United Kingdom – UK), (2) staff shortages and work overload, (3) challenging relationships with parents, and (4) the nature of pupils needs. For example:

“Have lost all hope and belief in the government. Special schools were never prioritised in any aspect when talking about schools either in re-opening or closing or any support. No respect for the sacrifices we made from leadership or parents which hurts” (participant 93).

“At the moment, the fact that we are required to deliver all provisions in section F of pupils” EHCP’s when we don’t have full access to some or all services. The fact that given the nature of our pupils, particularly those with sensory needs and other physical needs, we aren’t able to effectively social distance in the right way consistently, the fact that they (the government – they usually refers to the government) are requiring us to open full time with a full house with no support in PPE, halving class sizes, creating bubble groups or minimising expectations. We should not be out in a position where we are consistently risking our lives and both mental and physical health. My workload has worsened, expectations are still the same and anxieties are at an all-time high (Participant 10).

“We are not valued by our schools, parents or government. There has been no recognition of the work that we do. Not even a 1% pay rise or considered prioritised enough to get the vaccine. Parents are bullies and have no understanding of the work that we do. I feel sorry for the children who will be affected by all of this” (participant 70).

“Everything. Lack of funding for support for staff and kids. No school resources like extra support staff when people are off sick, even to the extent of no cleaning products for schools. I had to bring my own from home. Children cannot do online learning and so have fallen behind academically and socially even more so than typically developing children” (participant 10).

We asked participants whether they would leave their jobs now if they could; 47 (50.5%) said “Absolutely not,” 20 (21.5%) stated “perhaps, if I found a better one” and 13 (14%) said “Yes, I would.”

The last item of the survey allowed participants to express any other views they felt were not accurately captured by the survey items. The same themes have emerged when analysing their answers, with very similar responses to those pointing out main challenges throughout the pandemic. In particular, the lack of government support seems to be felt by most participants, but also the work overload and challenging relationships with parents:

“I/we feel completely let down by the government who said they would not prioritise teachers for vaccination. This coupled with the lack of consistency and constant changing and last minute decisions have created so many problems for us all. I would not leave my job for the kids I teach and support but if it was not for them I would seriously have left as soon as the pandemic started” (participant 54).

“We are under immense pressure from all. Disgruntled parents who cannot understand why their child cannot be in school. The pressures to change the entire teaching practice to remote learning. To having to educate our parents in a new way of communicating. Some parents believe we have closed school and that we are not supporting them, they clearly do not understand the daily hours, weeks and months that have been invested throughout this whole pandemic. We are exhausted, we went without the scheduled holidays to be able to continue the support that our families needed. House calls to deliver IT equipment. It never stopped” (participant 63).

“I regret working in Special Needs, I don’t feel that I am really a concern, I have caught COVID-19 at school and passed it on to my family, we have all been very ill. I have returned to work and not had one consultation on how I am feeling. I think everyone is too busy to really care, teaching assistants are considered ten a pen and my personal protection is not questioned. I do care very much about the pupils I help to look after but it seems to do this I am sacrificing my own family’s safety. I have a degree in Early Childhood Studies and spent a year studying autism at my own expense and in my own time and it feels wasted. I feel worthless and wish I had never gone into this field” (participant 67).

Do Individual Characteristics Such as Professional Role, Years of Experience and Geographical Location of the Setting Influence Professionals’ Perceived Wellbeing and Satisfaction With Current Job?

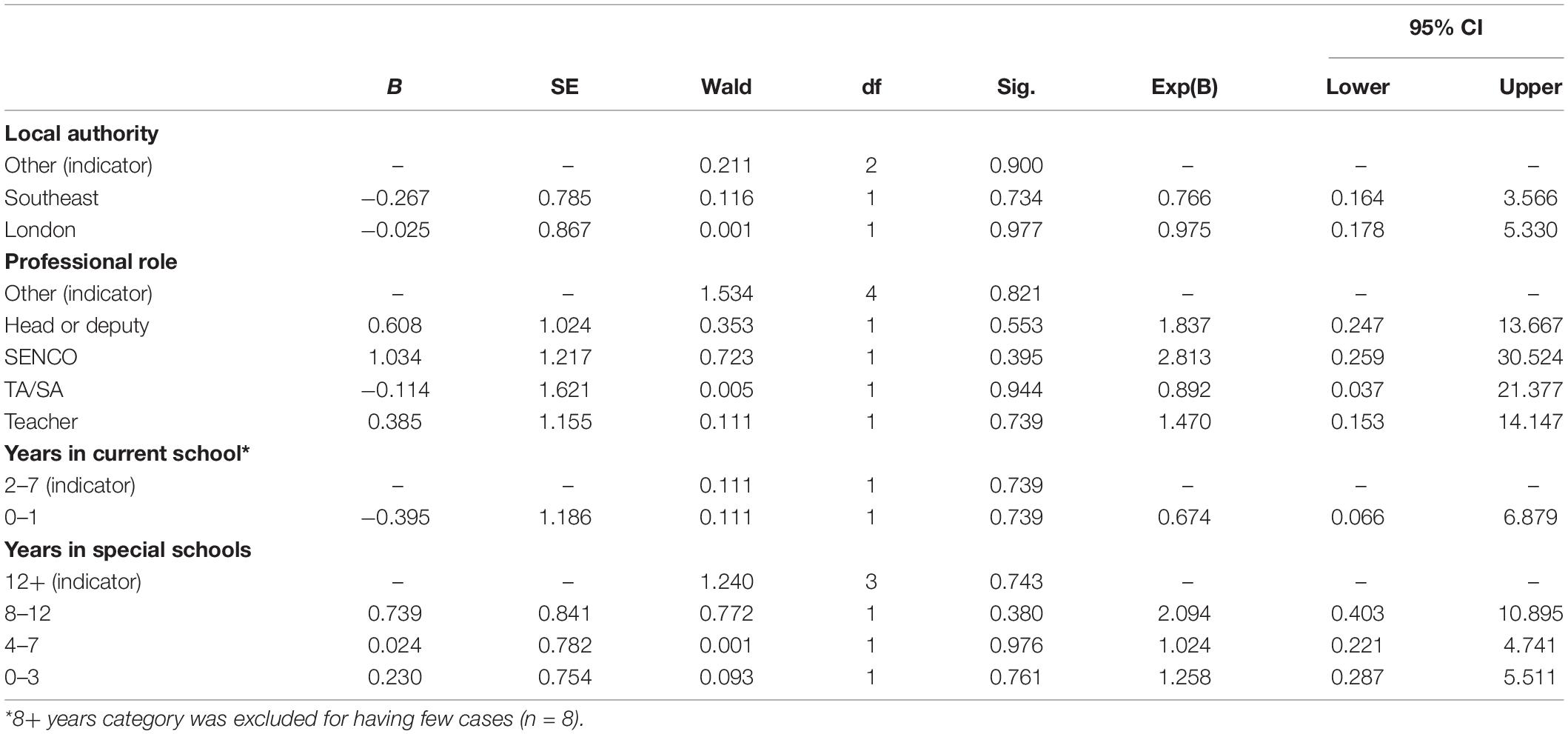

To understand the predictive role of the demographic variables under study on perceptions of wellbeing and on job satisfaction, two binary logistic regression models were tested, as the dependent variables were binary, once recoded. All assumptions required for running the models with these variables were met on both occasions, namely: having a nominal dependent variable and independence of observations. Tables 2, 3 show the regression coefficients obtained for both models.

Table 2. Regression coefficients regarding the effects of professional role, years of experience and geographical location of the setting on professionals’ perceived wellbeing (probability of responding that “it’s been hard or very hard”).

Table 3. Regression coefficients regarding the effects of professional role, years of experience and geographical location of the setting on whether professionals would leave the job if they could (probability of responding that “perhaps” or “Yes”).

Professional role, years of experience in the same school and in special education and geographical location do not predict and are unrelated to ratings of wellbeing (see Table 2). The model obtained is a good fit to the data given by the Hosmer and Lemeshow Test [χ2(8) = 2.021, p = 0.980].

An effect of years of experience was found in relation to whether practitioners would leave their current job if they could (see Table 3). The model obtained has good fit to the data [χ2(7) = 4.785, p = 0.686] and explains 17% (Cox and Snell) to 23% (Nagelkerke) of the variance in practitioners’ responses. Respondents were 7.6 times more likely to say they would change jobs if they could, if they had been working in special schools for less than 3 years [χ2(1) = 6.017, p = 0.014].

Discussion

The purpose of this article was to voice the experiences of professionals working in specialised settings providing services for children with SEND in England, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results reflect a number of concerns experienced by professionals with important implications for the future of the profession, and consequently, for the future of children with SEND. It is clear that staff did not feel that the United Kingdom Government nor the local authorities had done enough to support them in delivering the best quality provision in this period, to keep them safe and to protect their wellbeing. The narrative expressed in the open-ended answers to the survey is clear evidence of a sense of hopelessness and disbelief in a better future for the profession. Previous studies have highlighted the challenges faced by SEND professionals in the circumstances of the pandemic in England. For example, Middleton and Kay (2021) surveyed a small group of SENCOs on the impact of COVID-19 on the work that they do. The study concluded that SENCOs’ responsibilities have widened to include more administrative tasks, more emotional support to staff and students and also the need for a closer partnership with senior leaders and governors. Challenges such as heavy workload and sudden changes in government guidance were pointed out in the Middleton and Kay’s study, in line with our findings. However, the present study denotes emotionally charged responses, potentially reflecting the burnout that results from a considerable extended period of stress (data collection was performed in Spring 2021, later in the pandemic, when compared to previous studies).

There is also international evidence of challenges faced by SEND professionals in other countries. In Finland, Lukkari (2021) interviewed five special education teachers and found that remote teaching had increased home-school cooperation, lowered the threshold for parents to contact special education teachers, and overburdened teachers; technical difficulties were encountered, and the nature of communicating with parents had changed substantially. Sayman and Cornell (2021) examined the narratives of a small group of special education teachers in the United States, through reflective journals and virtual focus groups, during the 2020 lockdown. In this case, the main theme found was the teachers’ sense of loss, described as “grief,” not only in the period of school closures but also loss of the previous ways of working. Teachers also expressed they felt overwhelmed with their workload but seem to have immediately received appropriate training for online teaching. Similarly, Glessner and Johnson (2020) reported that teachers experiences revealed resilience, fostered by supportive relationships with administration, peers and families. However, these international accounts seem different from those observed in this study, where professionals report lack of confidence in Government and strong feelings of hopelessness and disbelief in the future of SEND provision. Their narratives reflect a general disposition compatible with the concept of learned helplessness (Seligman, 1972) – the repeated exposure to challenging working conditions generates a feeling of being unable to escape or believe in a better future. Feelings of learned helplessness have been described in students during the COVID-19 pandemic, as a result of being forced to rely on online learning technology and consequent growing exhaustion and sense of lost connectedness (Garcia et al., 2021). However, there is scarce evidence of this phenomenon as experienced by professionals working in SEND. Additionally, our results show that participants who joined their current special school most recently were more likely to say they would change jobs if they could. This may as well reinforce the argument of “learned helplessness” experienced by professionals with more years of experience in the setting – their accounts are emotionally charged, but change is not sought. This study provides evidence that staff working in SEND, in England, may be reaching a state of extreme burnout and urgent measures are needed to recover the system, integrating them as key pieces of that system, with sustained recognition and reward. The sense of fatigue can be seen from our results:

“We are exhausted, we went without the scheduled holidays to be able to continue the support that our families needed. House calls to deliver IT equipment. It never stopped” (participant 63).

Although long-term learned helplessness may be changed as a result of a shift in attributional status (Dweck and Goetz, 2018), the present study shows that professionals attribute the cause of their feelings to Government and sometimes to lack of understanding from parents, factors that they perceive as particularly difficult to change. Lake and Billingsley (2000) have looked at factors that contribute to parent-school conflict in special education; discrepant views of a child’s needs are enhanced by imbalance of knowledge, different views on service delivery (nature and length, for example), lack of reciprocal power (the use of intimidation), constraints (e.g., time, funding), valuation (issues of human worth), issues with communication (e.g., frequency and quality), and of trust (conciliatory attitudes). Participants in this study have referred to issues of reciprocal power (e.g., “parents are bullies”) but also to different views on service delivery and generally to a different understanding of what the children need versus what was possible to deliver in times with restricted resources (of time, funding, staff, etc.). This suggests that a substantial change in the system is urgently needed in post-pandemic times, to protect the profession, its status, the motivation of new trainees to join the profession and the wellbeing of those delivering direct services to children who are vulnerable and in need of the best quality provision. Crane et al. (2021) provide insights on potential actions undertaken by a group of special schools in London to mitigate the challenges faced during the pandemic; the group reiterates the issue that Special Schools were left as an after-thought for the Government, with guidelines on social distancing to schools largely not applying to their settings. In turn, the group undertook an individualised risk assessment for pupils and families, moved to frequent online parent consultations through a variety of media and signposted supports and resources needed particularly to disadvantaged families and pupils, where they could not provide the resources themselves. Although an extremely useful account of initiatives that could mitigate the impact of the pandemic on children and their families, the study does not cover the implications of these measures on the wellbeing of staff involved in service delivery. Moreover, the experience of this select group of London Special Schools is almost certainly not a reflection of the experience of specialised settings nation-wide, where lack of resources and funding as well as issues with reciprocal power are probably more apparent. The present study has attempted to illustrate the challenges faced by staff in the field and reflects the urgency of prioritising special education settings in a future recovery strategy. Notably, the study did not identify differences in staff perceptions based on their professional role, years of experience of geographical location, suggesting these may be widespread views across various sub-cohorts of professionals working in specialised settings. Moreover, although the majority of respondents would still continue on the profession if given the choice, a significantly large proportion (35.5%), would consider a change. In a time when staff shortages and work overload are consensual challenges, the results from this study suggest that the Government prioritise the transformation of SEND services into an attractive and rewarding career.

The study presents some limitations, the first of which is the concentrated sample in Greater London and the Southeast and the under-represented responses from other regions in England. The sample is relatively small and not nationally representative and, therefore, the absence of effects of demographic characteristics on wellbeing ratings may be an artefact of the sample characteristics. Variables required recoding into fewer categories for the purpose of analysis, which may contribute to some nuanced effects not to be revealed. The survey design adopted may have over-simplified the complexity of the views expressed and future research should complement these with in-depth interviews to fully gauge the essence of the learned helplessness phenomenon and illuminate potential ways forward. Its brief user-friendly nature was intended as such to respect the already overloaded work schedule of the target participants, and was praised in the pilot study. However, wider research making using of a range of methodologies of data collection (including interviews) may reveal other trends. Nevertheless, the study is one of few focussing on the experience of staff working in specialised settings in England and generates unique evidence of their concerns and challenges faced, with potential implications for the sustainability of the whole SEND system, in practice.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was to voice the experiences of professionals working in specialised settings supporting children with SEND in England, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main findings suggest that professionals working in these settings feel overwhelmed with the pressures brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic. Challenges mentioned include lack of confidence and hope in supports given by the Government, difficulties communicating and relating to parents and general difficulty in providing high quality services in under resourced environments, providing for children to whom social distancing measures were not applicable. A large proportion of staff surveyed would consider a different job if given the opportunity, in particular those working in their current special school for less than 3 years. This potentially reinforces the argument toward the “learned helplessness” phenomenon lived by more experienced professionals, where despite emotionally charged views, change is not sought. The sense of learned helplessness, acquired throughout the pandemic, potentially jeopardises not only the quality of provision but also the sustainability of the professional area. These findings are suggestive of a need to prioritise the wellbeing of staff and resources available to them, so as to promote careers that are rewarding and consequently, have the potential to positively impact the development and learning of the most vulnerable children.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, upon request.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of Roehampton. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

AM conceived and designed the study, collected the data, and contributed to the writing up. SC-K contributed to the design of the study, data collection, analysis of the data, and wrote the final manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., and Krutikova, S. (2020). Inequalities in Children’s Experiences of Home Learning during the COVID-19 Lockdown in England. Fiscal Stud. 41, 653–683. doi: 10.1111/1475-5890.12240

Azad, G., and Mandell, D. S. (2016). Concerns of parents and teachers of children with autism in elementary school. Autism 20, 435–441. doi: 10.1177/1362361315588199

Canning, N., and Robinson, B. (2021). Blurring boundaries: the invasion of home as a safe space for families and children with SEND during COVID-19 lockdown in England. Eur. J. Special Needs Educ. 36, 65–79. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872846

Castro-Kemp, S., and Mahmud, A. (2021). School Closures and Returning to School: Views of Parents of Children With Disabilities in England During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Front. Educ. 6:666574. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.666574

Crane, L., Adu, F., Arocas, F., Carli, R., Eccles, S., Harris, S., et al. (2021). Vulnerable and forgotten: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on autism special schools in England. Front. Educ. 6:666574. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.629203

Crawley, E., Loades, M., Feder, G., Logan, S., Redwood, S., and Macleod, J. (2020). Wider Collateral Damage to Children in the UK Because of the Social Distancing Measures Designed to Reduce the Impact of COVID-19 in Adults. BMJ Paediatrics Open 4, 1–4. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000701

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research, 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Department for Education (2021). Special Educational Needs in England. Retrieved from: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/special-educational-needs-in-england (accessed date 24 June 2021).

Dhiman, S., Sahu, P. K., Reed, W. R., Ganesh, G. S., Goyal, R. K., and Jain, S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak on Mental Health and Perceived Strain Among Caregivers Tending Children with Special Needs. Res. Dev. Disab. 107:103790. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103790

Dweck, C. S., and Goetz, T. E. (2018). Attributions and learned helplessness in New directions in attribution research. Hove: Psychology Press, 157–179.

Garcia, A., Powell, G. B., Arnold, D., Ibarra, L., Pietrucha, M., Thorson, M. K., et al. (2021). “Learned helplessness and mental health issues related to distance learning due to COVID-19,” in Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, 1–6.

Glessner, M. M., and Johnson, S. A. (2020). The Experiences and Perceptions of Practicing Special Education Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Interact. J. Glob. Leadership Learn. 1, 1–43.

Greenway, C. W., and Eaton-Thomas, K. (2020). Parent experiences of home-schooling children with special educational needs or disabilities during the coronavirus pandemic. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 47, 510–535. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12341

Guest, G., MacQueen, M., and Namey, E. E. (2014). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Lake, J. F., and Billingsley, B. S. (2000). An analysis of factors that contribute to parent—school conflict in special education. Remed. Spec. Educ. 21, 240–251.

Lukkari, O. (2021). Home-school cooperation during the COVID-19 pandemic: the perspective of elementary school special education teachers in Finland. [Unpublished Masters thesis]. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Middleton, T., and Kay, L. (2021). Uncharted territory and extraordinary times: the SENCo’s experiences of leading special education during a pandemic in England. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 48, 212–234. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12359

Montirosso, R., Mascheroni, E., Guida, E., Piazza, C., Sali, M. E., Molteni, M., et al. (2021). Stress symptoms and resilience factors in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychol. 40, 428–438. doi: 10.1037/hea0000966

Sayman, D., and Cornell, H. (2021). “Building the plane while trying to fly”: exploring special education teacher narratives during the Covid-19 pandemic. Plan. Chang. 50, 191–207.

Shaw, A. (2017). Inclusion: the role of special and mainstream schools. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 44, 292–312. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12181

Shelden, D. L., Angell, M. E., Stoner, J. B., and Roseland, B. D. (2010). School principals’ influence on trust: Perspectives of mothers of children with disabilities. J. Educ. Res. 103, 159–170. doi: 10.1080/00220670903382921

Sideropoulos, V., Dukes, D., Hanley, M., Palikara, O., Rhodes, S., Riby, D. M., et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and worries for families of individuals with special education needs and disabilities in the UK. J. Aut. Dev. Dis. 2021, 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05168-5

Steed, E. A., Phan, N., Leech, N., and Charlifue-Smith, R. (2021). Remote Delivery of Services for Young Children With Disabilities During the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J. Early Interv. 2021:10538151211037673. doi: 10.1177/10538151211037673

Thorell, L. B., Skoglund, C., de la Pena, A. G., Baeyens, D., Fuermaier, A. B., Groom, M. J., et al. (2021). Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: Differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Keywords: learned helplessness, SEN practitioners, SEND, England, COVID-19

Citation: Mahmud A and Castro-Kemp S (2022) “Lost All Hope in Government”: Learned Helplessness of Professionals Working in Specialised Education Settings in England During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:803044. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.803044

Received: 27 October 2021; Accepted: 17 January 2022;

Published: 21 February 2022.

Edited by:

Waganesh A. Zeleke, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jenny Wilder, Stockholm University, SwedenLilly Augustine, Jönköping University, Sweden

Copyright © 2022 Mahmud and Castro-Kemp. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arif Mahmud, QXJpZi5NYWhtdWRAcm9laGFtcHRvbi5hYy51aw==

Arif Mahmud

Arif Mahmud Susana Castro-Kemp

Susana Castro-Kemp