- 1School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences, Technological University of Dublin, Dublin, Ireland

- 2School of Human Development, Institute of Education, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland

- 3Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science & Engineering, Maynooth University, Kildare, Ireland

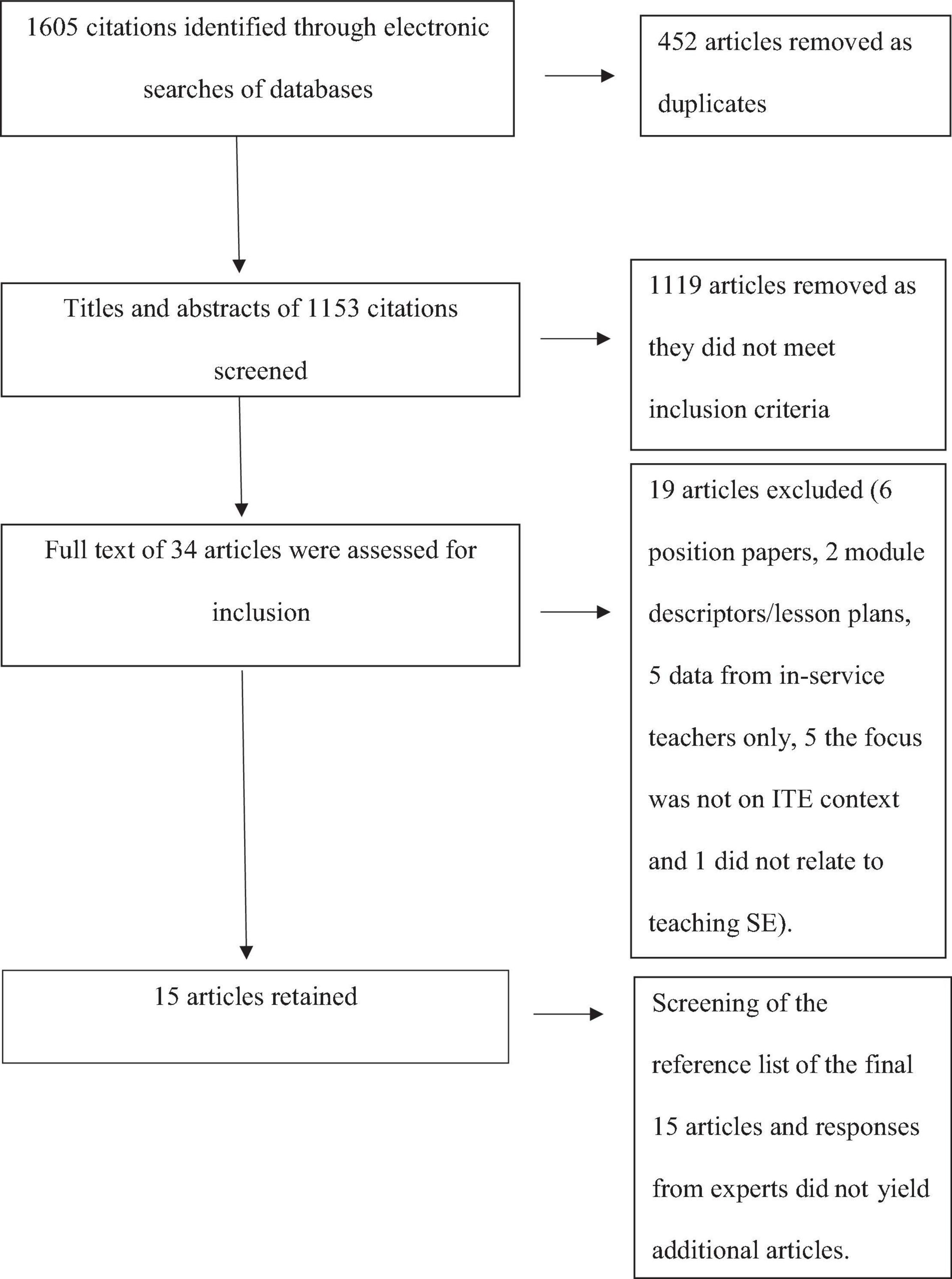

Teachers, and their professional learning and development, have been identified as playing an integral role in enabling children and young people’s right to comprehensive sexuality education (CSE). The provision of sexuality education (SE) during initial teacher education (ITE) is upheld internationally, as playing a crucial role in relation to the implementation and quality of school-based SE. This systematic review reports on empirical studies published in English from 1990 to 2019. In accordance with the PRISMA guidelines, five databases were searched: ERIC, Education Research Complete, PsycINFO, Web of Science and MEDLINE. From a possible 1,153 titles and abstracts identified, 15 papers were selected for review. Findings are reported in relation to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework of core competencies for sexuality educators. Results revealed that research on SE during ITE is limited and minimal research has focused on student teachers’ attitudes on SE. Findings indicate that SE provision received is varied and not reflective of comprehensive SE. Recommendations highlight the need for robust research to inform quality teacher professional development practices to support teachers to develop the knowledge, attitudes and skills necessary to teach comprehensive SE.

Introduction

Sexuality Education

Our understanding of sexuality education is ever evolving, and differences exist in the terminology, definitions and criteria employed across various international documentation relating to SE (cf. Iyer and Aggleton, 2015; European Expert Group on Sexuality Education, 2016). While the term comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has, in the last decade or so, come to be widely employed (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017; United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2018), given its more recent common usage, for the purpose of this paper, sexuality education (SE) is the broader term employed.

An international qualitative review of studies which report on the views of students and experts/professionals working in the field of SE (Pound et al., 2017) provides recommendations for effective SE provision. According to that review, effective SE provision should include: The adoption of a “sex positive,” culturally sensitive approach; education that reflects sexual and relationship diversity and challenges inequality and gender stereotyping; content on topics including consent, sexting, cyberbullying, online safety, sexual exploitation, and sexual coercion; a “whole-school” approach and provide content on life skills; non-judgmental content on contraception, safer sex, pregnancy and abortion; discussion on relationships and emotions; consideration of potentially risky sexual practices and not over-emphasize risk at the expense of positive and pleasurable aspects of sex; and the production of a curriculum in collaboration with young people. Similarly, Goldfarb and Lieberman’s (2021) systematic review provides support for the adoption of comprehensive SE that is positive, affirming, inclusive, begins early in life, is scaffolded and takes place over an extended period of time.

Teachers as Sexuality Educators

While there are a variety of sources from which students access information for SE, and diversity in respect of students expressed preferences with regards to SE sources (Turnbull et al., 2010; Donaldson et al., 2013; Pound et al., 2016), the formal education system remains a significant site for universal, comprehensive, age-appropriate, effective SE. Teachers are particularly well-positioned to provide comprehensive SE and create a climate of trust and respect within the school (World Health Organisation [WHO]/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA, 2010, 2017; Bourke et al., 2022). Qualities of the teacher and classroom environment are associated with increased knowledge of health education, including SE, for students. Murray et al. (2019) found that the teacher being certified to teach health education, having a dedicated classroom, and having attended professional development training were associated with greater student knowledge of this subject. Inadequate training, embarrassment and an inability to discuss SE topics in a non-judgmental way have been cited as explanations provided by students as to why they would not consider teachers suitable or desirable to teach SE (Pound et al., 2017).

Walker et al. (2021) in their systematic review of qualitative research on teachers’ perspectives on sexuality and reproductive health (SRH) education in primary and secondary schools, reported that adequate training (pre-service and in-service) was a facilitator that positively impacted on teachers’ confidence to provide school-based SRH education. These findings highlight the importance of quality teacher professional development, commencing with initial teacher education (ITE), for the provision of comprehensive SE. Consequently, ITE has increasingly been proposed as key in addressing the global, societal challenge of ensuring the provision of high-quality SE.

Initial Teacher Education

Teacher education provides substantial affordances to respond to the opportunities and challenges presented in the area of SE (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017). Furthermore, a research-informed understanding of teacher education is emphasized to better support teacher educators in their work with student teachers (Swennen and White, 2020).

Quality ITE provides a strong foundation for teachers’ delivery of comprehensive SE and the creation of safe and supportive school climates. Research has found that teacher professional development in SE is a significant factor associated with the subsequent implementation of school-based SE (Ketting and Ivanova, 2018). A recent Ecuadorian study reported that student teachers held a relatively high level of confidence in terms of their perceived ability to implement SE and to address specific CSE topics. Furthermore, favourable attitudes toward CSE, strong self-efficacy beliefs to implement CSE, and increased confidence in the ability to implement CSE were significantly associated with positive intentions to teach CSE in the future. Insufficient mastery of CSE topics, however, may temper student teachers’ intentions to teach CSE (Castillo Nuñez et al., 2019). Internationally, research suggests there is inconsistency in the provision of SE in ITE and that access to professional development in SE in ITE, and after qualification, needs substantial development (United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2009, 2018; Ketting et al., 2018; O’Brien et al., 2020).

Research is thus warranted to explore aspects at the institutional, programmatic and student-teacher level at ITE to address issues regarding the provision, and barriers to SE provision during ITE. Contemporaneous to the current review, O’Brien et al. (2020) undertook a systematic review of teacher training organizations and their preparation of student teachers to teach CSE. They found that teacher training organizations are often strongly guided by national policies and their school curricula, as opposed to international guidelines. They also found that teachers are often inadequately prepared to teach CSE and that CSE provision during ITE is associated with greater self-efficacy and intent to teach CSE in schools. The importance of ITE with regards to the provision of SE cannot be underestimated. Teachers are in an optimal position to provide age-appropriate, comprehensive and developmentally relevant SE to all children and young people.

The current systematic review will assess the provision of SE to student teachers in ITE and how this relates to the relevant knowledge, attitudes and skills required of sexuality educators as proposed by the international guidelines produced by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017). The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework of core competencies for sexuality educators adopts a holistic definition of core competencies, espousing an understanding of teacher competencies as “…overarching complex action systems” and as multi-dimensional, made up of three components: attitudes, skills and knowledge (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017, p. 20). This framework outlines a set of general competencies, together with more specific attitudes, skills and knowledge competencies for sexuality educators. Attitudes, which may be explicit or implicit, are understood as a factor pertaining to the influencing and guiding of personal behaviour. Skills are understood in terms of the abilities educators can acquire which enables them to provide high-quality education. While knowledge is understood as professional knowledge (pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge and pedagogical subject knowledge) in all relevant areas required to deliver high-quality education. Overall, the framework endorses a holistic and multi-dimensional approach which focuses on sexuality educators and the inter-related competencies, in relation to the knowledge, attitudes, and skills that they should have, or need to develop to become effective teachers of SE.

Aims and Objectives

The current study aimed to systematically review existing empirical evidence on the provision of SE for student teachers in the context of ITE.

The objectives were:

• To review the existing peer-reviewed, published literature on SE provision during ITE.

• To synthesize the research on SE provision at ITE institutional/programmatic level.

• To synthesize the research on individual level student teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills in relation to SE during ITE.

Materials and Methods

The systematic review was completed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009). A descriptive summary and categorization of the data is reported (Khangura et al., 2012).

Eligibility Criteria

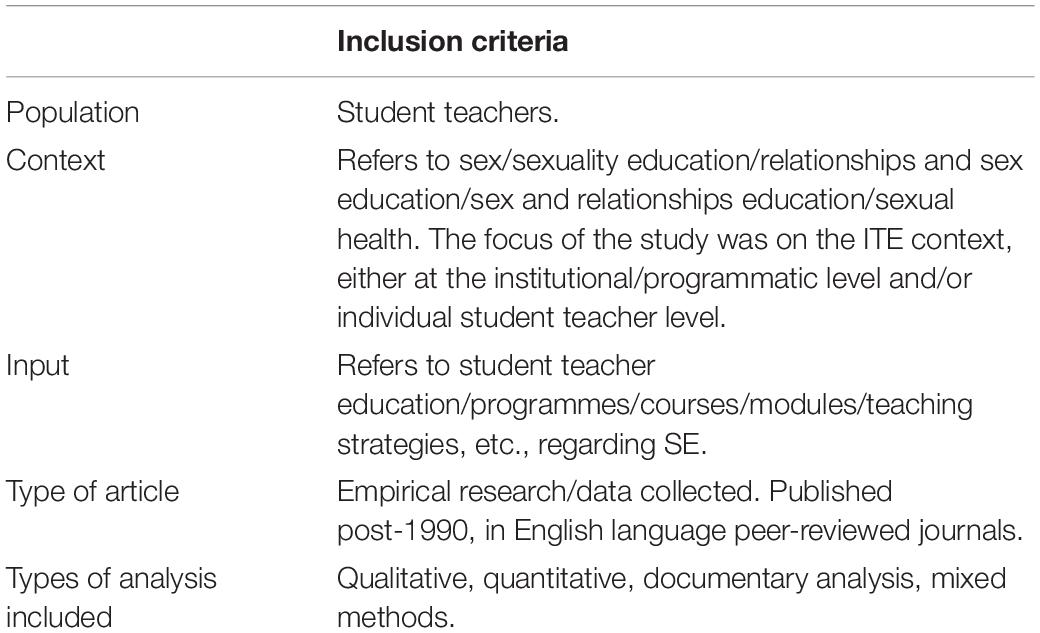

Articles were included in the review subject to adherence to specific inclusion criteria. An overview of inclusion criteria is outlined in Table 1.

Information Sources

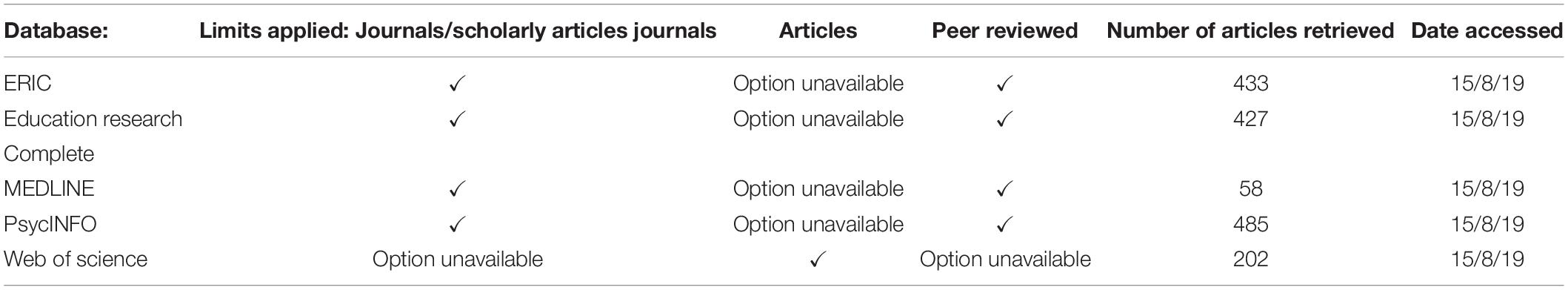

A three-reviewer process was employed. Searches were conducted in August 2019 on five databases selected for their ability to provide a focused search within the disciplines of education (ERIC and Education Research Complete), psychology (PsycINFO), and multi-disciplinary research in the disciplines of health/public health (Web of Science and MEDLINE).

Screening and Study Selection

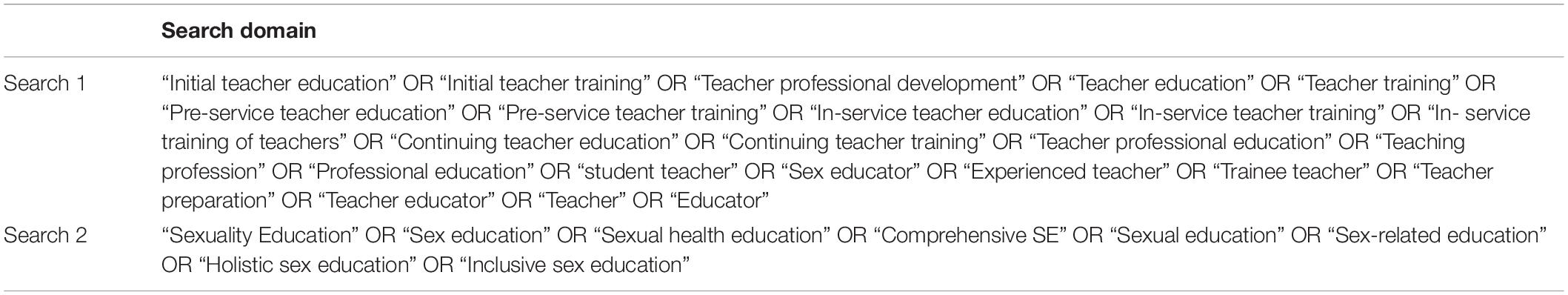

Reviewers’ selected keywords from two domains, namely ITE and SE as outlined in Table 2, for the searches. Search terms for each domain were combined using the Boolean search function “AND.”

Where possible, limits were applied to include articles from peer reviewed journals as outlined in Table 3.

In accordance with Boland et al. (2017), a pilot screening of a sample of titles and abstracts were completed by two reviewers to assess the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All titles and abstracts were then screened using Abstrackr software (Abstrackr, 2010, accessed 2019; Wallace et al., 2010). A selection of abstracts were then cross checked by two reviewers. The final selection involved a three reviewer process. Duplicates and references which did not meet the eligibility criteria were removed at this stage. Full text papers of the remaining articles were obtained, where possible. All three reviewers blindly screened the texts of the remaining articles. Consensus was reached that 15 articles met the criteria for this review. Two experts in the field of SE reviewed the list of 15 articles to ensure there were no outstanding papers for consideration within the parameters of the review. No additional papers were identified.

Data Collection Process

A data extraction template was devised in accordance with Boland et al.’s (2017) recommendations. Information was collected on each study regarding: participant characteristics (data on participant gender, age, programme and institution of study, ethnicity, socio-economic status and religion were extracted, where provided); whether the studies examined programmatic input and if so the duration/extent of input; theoretical and conceptualization of SE within the programme; topics covered; whether this was a compulsory or elective programme; and whether the study addressed the WHO-BZgA competencies of knowledge, attitudes and skills of student teachers during ITE (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017). One lead author was contacted for the purpose of data collection and provided further information regarding their study.

Synthesis of Results

A qualitative synthesis was conducted; the purpose of which was to provide an overview of the evidence identified regarding research on the provision of SE in the ITE context. The findings of the reviewed studies were synthesized following consideration of the key learnings and recommendations from the studies and consideration of the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) competencies of knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for the provision of SE at ITE. The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) framework was selected to support the categorization and analysis of findings as it was developed by global experts in the field and is thus, an international standard for SE. While there are limitations to the use of this framework, it offered the ability to categorize and analyze findings through a multi- dimensional lens of knowledge, attitudes, and skills.

Quality Appraisal

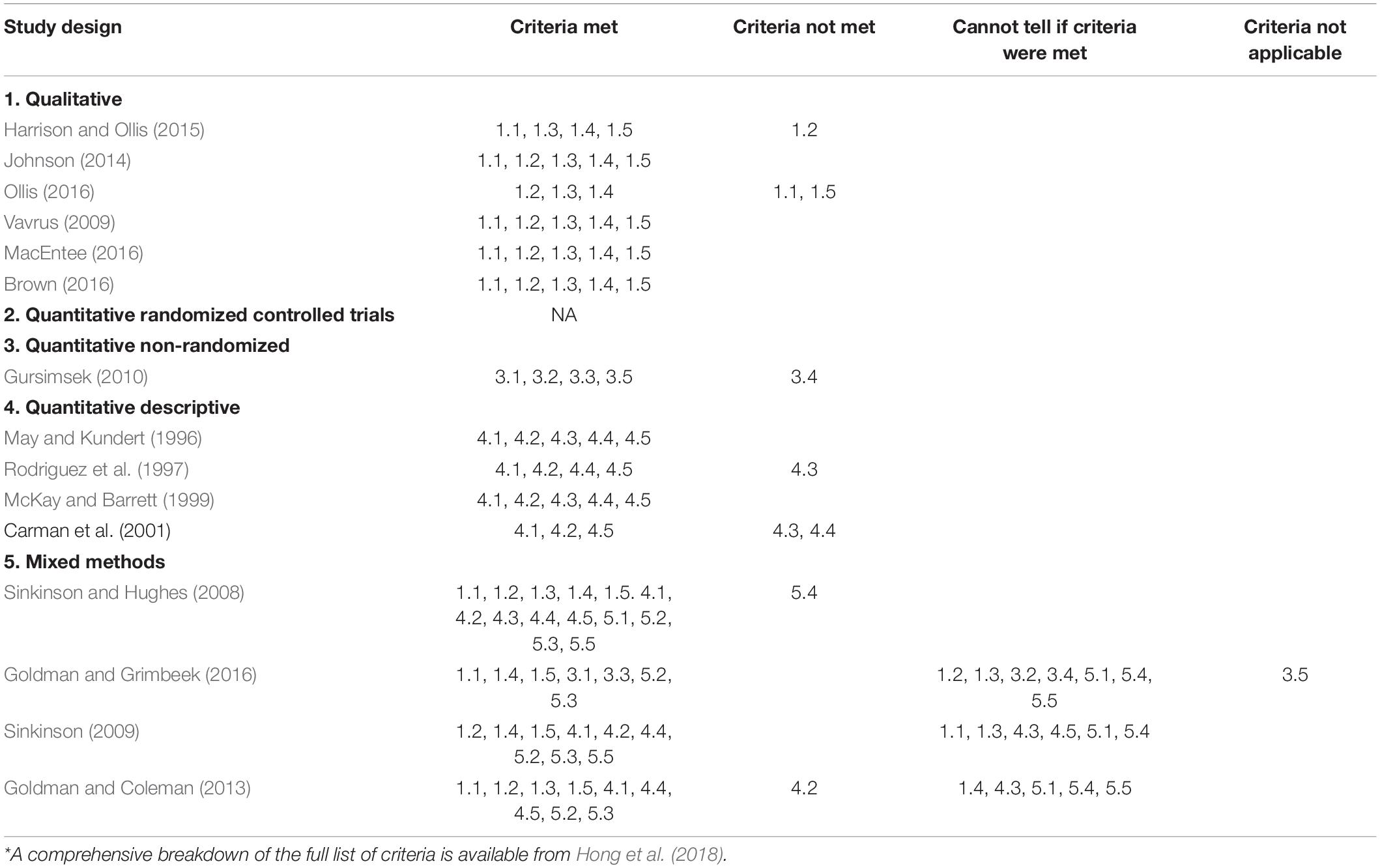

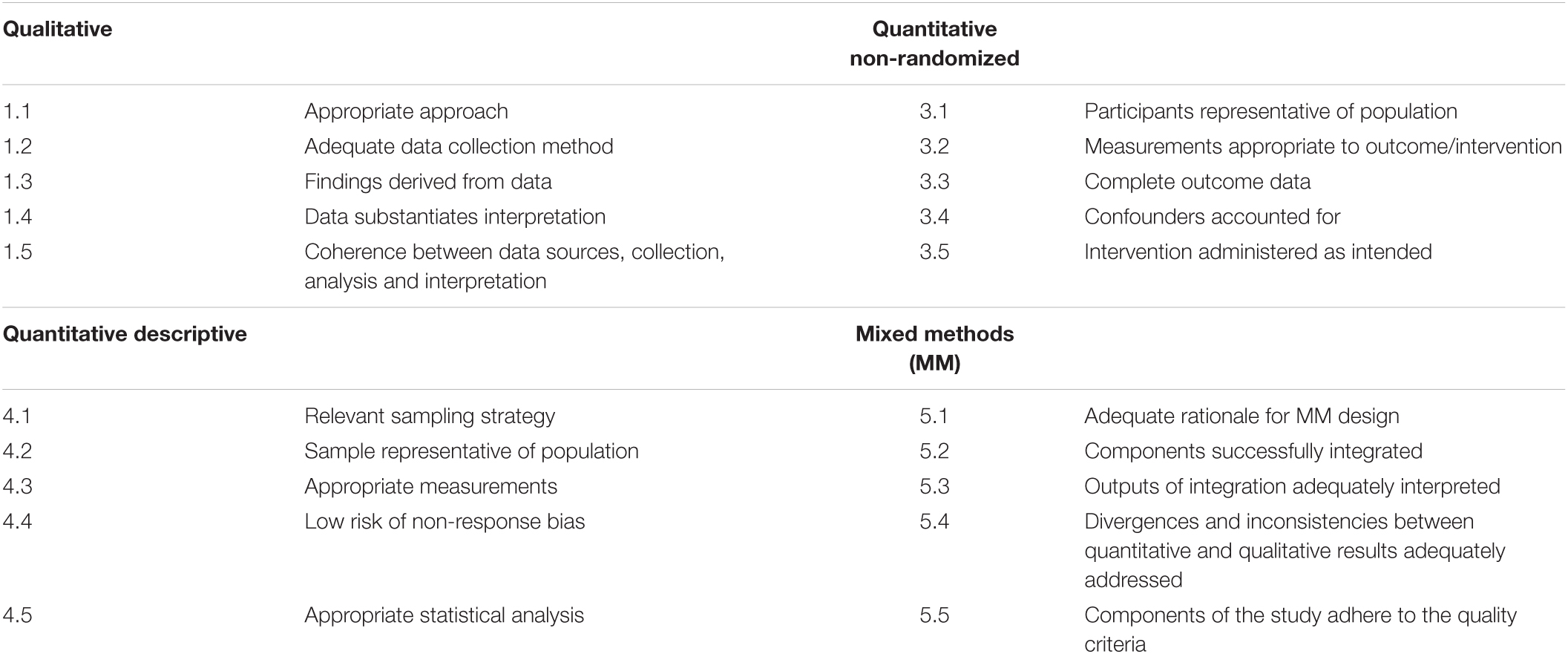

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pluye et al., 2009; Hong et al., 2018) was used to appraise the quality of papers by two reviewers. This tool has been found to be reliable for the appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies (Pace et al., 2012; Taylor and Hignett, 2014) and has been successfully used in previous systematic reviews (e.g., McNicholl et al., 2019). For each paper, the appropriate study design was selected (i.e., 1. Qualitative, 2. Quantitative randomized controlled trials, 3. Quantitative non-randomized, 4. Quantitative descriptive, and 5. Mixed methods). Next, the paper was assessed using the checklist associated with the study design (see Appendix A for overview of checklist). For example, if the study was categorized as 4. Quantitative descriptive, the study was assessed against the five criteria (4.1–4.5) associated with this study design. An example of a question on the checklist includes “Are the measurements appropriate?” criteria were reported as “met,” “not met,” “cannot tell if criteria were met” or “criteria not applicable.” The results of the quality appraisal are presented in Table 4. The same numbering as the methodological quality criteria of Hong et al.’s (2018) study was used.

Results

Study Selection

Fifteen articles reporting on thirteen empirical studies were included in the review (see Figure 1). Harrison and Ollis (2015) and Ollis (2016) articles are derived from the same dataset, as are Sinkinson and Hughes (2008) and Sinkinson (2009) articles. Given, however, that these articles refer to unique aspects of the particular studies, they have been described and discussed as separate studies in this review. An overview of the process of screening and study selection is outlined in Figure 1.

Study Characteristics

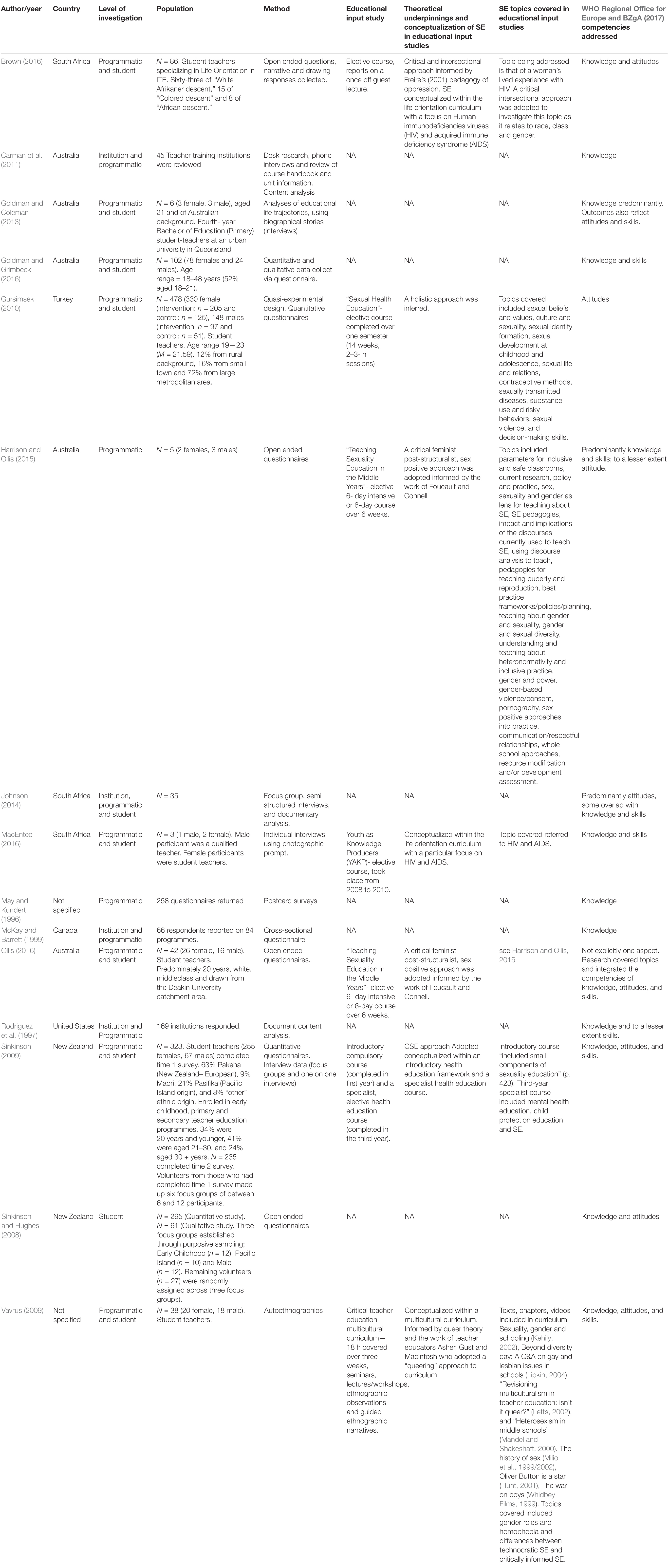

Six qualitative, five quantitative, and four mixed methods studies were reviewed. Where information was available, the research studies were identified as having been conducted predominantly in Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. The studies were published between 1996 and 2016. Data was most frequently collected from one source; student teachers (n = 10) and teacher educators/course providers (n = 3). One study collected data from both student teachers and teacher educators/course providers (Johnson, 2014). The samples size of studies varied from three to 478 participants but were generally small (eight of the studies had fewer than 90 participants: Vavrus, 2009; Carman et al., 2011; Goldman and Coleman, 2013; Johnson, 2014; Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Brown, 2016; MacEntee, 2016; Ollis, 2016).

Seven studies assessed SE educational inputs at ITE, and three conducted content analysis of content covered on SE educational input at ITE. As the studies were predominantly descriptive and explorative in design, specific outcome variables were often neither defined nor addressed. Educational input studies were classified as examples of research which assessed a particular course, module, or lecture on SE at ITE. With regards to theoretical approaches that may have informed the educational input studies reviewed, three did not report a specific theoretical approach (Sinkinson, 2009; Gursimsek, 2010; MacEntee, 2016), and the remaining four reported that a critical approach was adopted (Vavrus, 2009; Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Brown, 2016; Ollis, 2016). An overview of study characteristics are presented in Table 5.

Quality Appraisal Results

An overview of the results of the MMAT are presented in Table 4. All the papers in the review were empirical studies and therefore could be appraised using the MMAT. Predominantly the studies reviewed employed the use of qualitative methods, and of the mixed methods studies there was often an emphasis on the qualitative data. Generally, the quality of the mixed methods studies was varied with only a minority of these studies providing a rationale for the use of mixed methods and reporting on divergences between the qualitative and quantitative findings.

The rigour and quality of the qualitative research was also varied. An explicit statement of the epistemological stance adopted and detail of the analytical process were reported in a minority of studies. With regards to educational input studies, data was often collected only after the educational input was completed and thus behavioral change as a result of engagement in the educational input could not be ascertained (e.g., Harrison and Ollis, 2015; MacEntee, 2016; Ollis, 2016). Only one study employed a quasi-experimental design (Gursimsek, 2010), and in this case a purposive sample of student teachers who did not complete the SE course was selected as the control group. Within the remaining 14 studies there were no control groups, randomization, or concealment.

Synthesis of Results

Findings are reported in relation to (a) institutional/programme level and (b) individual student teacher level aligned with the World Health Organisation (WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA, 2017) Training Matters: Framework of Core Competencies for Sexuality Educators. An awareness of the interaction of these aspects of student teachers’ development was informative in terms of structuring the findings.

The research studies reviewed predominantly focused on examining a particular educational input on SE during ITE (Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Gursimsek, 2010; Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Brown, 2016; MacEntee, 2016; Ollis, 2016) or investigating the SE content covered during ITE (Rodriguez et al., 1997; McKay and Barrett, 1999; Carman et al., 2011). Fewer of the reviewed studies focused on student teachers’ skills to teach SE (e.g., Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Goldman and Grimbeek, 2016; MacEntee, 2016) or student teachers’ attitudes regarding SE (e.g., Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008; Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Gursimsek, 2010; Johnson, 2014; Brown, 2016). The findings of the studies were synthesized and categorized in relation to institutional/programmatic level or individual student teacher level. Findings which reflected responses and perceptions of student teachers were categorized as individual student teacher level. Institutional/Programme level related to studies assessing particular modules or comparing course content across programmes, and institutional level studies were categorized as studies where data was collected from multiple institutions. Individual student teacher level findings were reported in relation to the knowledge, attitudes, and skills competency areas required of sexuality educators. These competency domains, however, are not discrete entities or mutually exclusive. In taking a systemic approach, it is, therefore, acknowledged that they are dynamically interconnected, and influence and interact.

Institutional/Programme Level Findings

At a programmatic level, studies revealed variance in the type of SE provision (core/mandatory and elective), student teachers receive during ITE. May and Kundert (1996) found that coursework on SE was reported as part of a mandatory course by 66% of respondents and as part of an elective course by 14% of respondents. While McKay and Barrett (1999) reported that only 15% of the health education programmes in their study offered mandatory SE training with 26% of programmes offering an elective component. With regards to the provision of skill development and training for SE that student teachers received during ITE, Rodriguez et al. (1997) found that of a potential 169 undergraduate programmes, the majority (i.e., 72%) offered some training to student teachers in health education: A minority offered teaching methods courses in SE (i.e., 12%) and HIV/AIDS prevention education (i.e., 4%). Two of the reviewed studies also investigated programme time allocated to SE and found that time spent on SE varied from 3.6 hours (May and Kundert, 1996) to between 9.6 and 36.2 hours (McKay and Barrett, 1999). While at an institutional level, Carman et al. (2011) found that eight of 45 teacher training institutions did not offer any training in SE and of those that did, 62% offered mandatory, and 38% elective inputs.

Findings indicate the paucity of SE topics covered across ITE programme curricula. Rodriguez et al. (1997) reported that 90% of the courses they reviewed listed a maximum of three SE topic areas. The top three SE topics reported in terms of coverage were human development, relationships, and society and culture. Somewhat consistently, McKay and Barrett (1999) found that the topics least emphasized on courses were masturbation, sexual orientation, human sexual response, and methods of sexually transmitted disease prevention. Johnson (2014) sought to examine coverage of, what they defined as, “lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersexual (LGBTI)” (p. 1249) issues on ITE courses and reported that of the three ITE institutions examined, none specifically reference LGBTI issues. Finally, one study reported that the provision of SE was found to be contingent on the interest and expertise of the university teacher educators (Carman et al., 2011). Collectively, these findings bring to light the variance in mandatory and/or elective SE provision during ITE, as well as the diverse content covered and the role of teacher educators on its provision.

Individual Student Teacher Level Findings

Factors Associated With Student Teachers’ Attitudes Regarding Sexuality Education Topics

Gender, geographical location, religious beliefs, and family background were identified as factors associated with student teachers’ attitudes regarding SE (Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008; Gursimsek, 2010; Johnson, 2014). Attending a SE course may have positive implications for student teachers’ attitudes as Gursimsek (2010) found that students who had not attended the SE course reported more conservative and prejudiced views toward sexuality than those who had attended the SE course. Given that this was an elective course, however, it is important to consider self-selection bias regarding those who may have opted to take the course.

Student teachers in Johnson’s (2014) study reported that, through engagement in educational inputs which discussed sexuality issues in an open and inclusive way, greater awareness of student teachers’ own and others’ biases was developed. So, too, was knowledge to better understand sexuality issues. Student teachers did, however, acknowledge difficulty integrating these new learnings with their family backgrounds, and belief systems. MacEntee’s (2016) study also brought to light tensions between student teachers’ intentions to teach, and their own attitudes to SE topics and norms within schools. Since the educational input, however, none had used the participatory visual methods when teaching about HIV and AIDS during their teaching practice. Student teachers’ responses indicated that external factors made it difficult to independently continue to integrate participatory visual methods and HIV and AIDS topics into their teaching practice experiences in schools. The findings from Johnson (2014), and MacEntee (2016) studies indicate that student teachers’ intentions and the realities of teaching subjects and using pedagogical approaches in schools do not always align.

Critical Consciousness

The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework outlines the objectives of SE, including “open-mindedness and respect for others” (p.26). Although SE courses during ITE may be student teachers’ first exposure to issues of sexual and gender equality, for example, critiques of hetero-normativity (Vavrus, 2009) and introductions to critical feminist discourses (Harrison and Ollis, 2015), findings from several of the studies (Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Harrison and Ollis, 2015), indicated that the SE programmes offered during ITE may be insufficient in developing student teachers’ critical consciousness—the ability to recognize and analyze wider social and cultural systems of inequality and the commitment to take action to address such inequalities.

Vavrus (2009) found student teachers expressed varying degrees of critical consciousness as a result of completing a multi-cultural curriculum and assignment. While Harrison and Ollis’s (2015) examination of micro-teaching lessons indicated that completion of an educational input on SE from a feminist, post-structuralist perspective did not suffice in increasing student teachers’ understanding of gender/power relations but rather brought to light the challenges of employing such a perspective. Similarly, Sinkinson (2009) reported a noticeable lack of development of criticality regarding socio-cultural perspectives of SE from the completion of an introductory health education course (2004, first year) to the completion of a specialist health education course (2006, third year). Finally, albeit difficult to generalize given the study’s small sample size, Brown (2016) reported that experiential pedagogical approaches, through inclusion of a guest speaker living with HIV, and employment of a critical, creative arts-based pedagogical strategy offered a critical lens through which student teachers moved from a position of stigmatization toward one of understanding and compassion.

Factors Associated With Student Teachers’ Skills Regarding Sexuality Education Topics

With regards to student teachers’ skills, or potential skill development during ITE, several aspects of ITE were identified as significant in relation to the acquisition of the required skills to teach SE. These included the pedagogical approaches adopted during ITE; the learning environment; opportunities for practical teaching experience, and critical self- reflection.

Pedagogical Approaches and Practical Teaching Experiences

Seven of the studies reviewed examined aspects of pedagogical approaches to teaching SE (Rodriguez et al., 1997; Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008; Sinkinson, 2009; Carman et al., 2011; Goldman and Coleman, 2013; Johnson, 2014; Goldman and Grimbeek, 2016). Goldman and Coleman (2013) reported that their small sample of six student teachers indicated that they learned very little regarding knowledge and pedagogical approaches specific to SE during ITE. Sinkinson (2009), however, found that student teachers identified co- constructivist pedagogical approaches as being important when teaching SE. Student teacher participants in MacEntee’s (2016) study indicated that the use of participatory visual methods was a novel and thought-provoking way to learn about HIV and AIDS.

Several of the studies indicated the need for opportunities for student teachers to teach and develop the skills to teach SE. Harrison and Ollis (2015) article was the sole study to report on the evaluation of the potential pedagogical skills student teachers had acquired following the completion of SE input. Their examination of micro-teaching lessons indicated the value in examining student teachers teaching of SE. Through this experience, they identified that the educational input had been insufficient in providing student teachers with the opportunity to reflect on a critical approach to gender and sexuality, and to develop the pedagogical skills to teach SE from a critical perspective.

Vavrus (2009) suggested that, given the level of fear acknowledged by student teachers around teaching SE, interventions and programmes should provide structured opportunities for student teachers to construct lesson plans that critically address gender identity and sexuality in developmentally appropriate ways. Vavrus (2009) further suggests that instruction on conducting discussions related to gender identity and sexuality, and strategies to respond to homophobic and sexist discourse should also be provided. Participants in Brown’s (2016) study similarly reported that they would have liked to have had more opportunities to familiarize themselves with facilitating visual participatory methods when teaching about SE topics such as HIV and AIDS.

Learning Environment

MacEntee’s (2016) study provides provisional support for the use of workshops in learning about HIV and AIDS. Student teachers (Goldman and Grimbeek, 2016) and course providers (Johnson, 2014), indicated preferences for the use of tutorial groups, small group face-to-face discussion, and case studies when teaching about SE. In both studies, these approaches were associated with creating less threatening, and more comfortable environments for student teachers to engage with topics on a personal level. Across studies, student teachers remarked that respect and acceptance of other people’s views and opinions were critical to ensure that the environment in which SE provision takes place is safe. These views are aligned with two of the overarching skills outlined by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017); the “ability to use interactive teaching and learning approaches” and the “ability to create and maintain a safe, inclusive and enabling environment” (p. 28). In relation to assessment of SE at ITE, Goldman and Grimbeek (2016) found that student teachers had a preference for group-based assessments, independent research, and self-assessment.

Consistent with the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) Training Matters: Framework of Core Competencies for Sexuality Educators, sexuality educators should “be able to use a wide range of interactive and participatory student-centered approaches” (p. 28). These findings indicate that the creation of interactive and participatory learning environments is conducive to SE at ITE level. The opportunity to engage in these types of learning environments and student teachers’ positive perceptions of these learning environments may have consequences for the classroom environment which student teachers subsequently create.

Critical Self-Reflection

The ability of sexuality educators to reflect on beliefs and values is a vital skill, according to WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017). The reviewed studies consistently cited the importance of self-reflection in SE provision during ITE. Vavrus (2009) found that self-reflection was critical to the development of a more understanding, and empathetic, approach to teaching. Harrison and Ollis (2015) emphasized the need to support teachers in the development of reflective practices. Ollis (2016) concluded that the opportunity for self-reflection would impact on student teachers’ intention to include pedagogies of pleasure in their practice. Johnson’s (2014) study indicated that engagement in reflection regarding the self and others, helped students to develop a better understanding of their own beliefs and assumptions. The findings from Johnson’s study, however, also show that increased opportunity for self-reflection, and exposure to critical interpretations of content, do not necessarily transfer to teaching behaviours. Gursimsek (2010) recommended the inclusion of critical self-reflection components on future SE courses as it was suggested that components would assist student teachers in clarifying their own social and sexual values, life experiences, and learning histories. This clarification then assists, and supports, maturation in terms of attitudes, beliefs, knowledge as they relate to sexuality. Collectively, these findings indicate that teaching in ITE needs to provide safe spaces for self-reflection on the part of student teachers—and honest engagement with others.

Factors Associated With Student Teachers’ Knowledge Regarding Sexuality Education Topics

Two of the reviewed studies explored the topics student teachers perceived as important for school students to learn about, and the topics they themselves would like to study during ITE. Sinkinson and Hughes (2008) found that, of the aspects of health education student teachers prioritized for school students, the most important were mental health (62%); aspects of sexuality (61.2%); and drugs and alcohol (46.8%). Mental health included “personal development, relationships, emotional health and essential skill development such as decision making” (p. 1079). Student teachers’ responses indicate that they saw personal and interpersonal topics as important aspects of health education. Goldman and Grimbeek (2016) reported that, during ITE on SE, student teachers would most prefer to have social, psychological, and developmental factors associated with student/learner puberty and sexuality addressed. Older student teachers—those in the 22–48 year-old age range—were significantly more likely than their younger student teachers to strongly rate preferences for knowledge about wider socio-cultural contextual factors.

Student Teachers’ Confidence and Comfort to Teach Sexuality Education

Four of the studies reviewed reported student teachers’ comfort and confidence in teaching SE (Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Johnson, 2014; Ollis, 2016). Student teachers in Sinkinson’s (2009) study suggested that increases in knowledge and learning about SE topics increased comfort levels and intention to teach SE. Student teachers suggested that the opportunity to listen, learn, and discuss topics in an open environment reduced their embarrassment in discussing SE issues. These opportunities increased their comfort for answering pupils’ questions, and using language that they had previously considered taboo (Sinkinson, 2009). Vavrus (2009) reported that having completed the educational input on SE, all student teachers felt they would create an open and safe space for students. Some student teachers reported confidence in their ability to create content, and think of topics to cover, relating to sexuality and gender identity. Responses also indicated challenges for student teachers regarding empathy; fears on how to respond to issues of sexuality and gender identity; lack of experience; feeling unprepared; and fear of reprisal for working outside traditional norms. Cognitive dissonance between the knowledge student teachers acquired about sexuality issues during ITE, and their personal and familial belief system in Johnson’s (2014) study was associated with discomfort for student teachers. Thus, findings from Vavrus’s (2009) and Johnson’s (2014) studies indicate that, although ITE had provided student teachers with knowledge on SE topics, wider socio-cultural/systemic factors may influence student teachers’ confidence or comfort to integrate or apply this knowledge outside of the ITE context.

A lack of student teacher knowledge about SE topics, especially with regards to “non- normative” areas, such as HIV/AIDS, was reported by Brown (2016) as associated with “othering” and discomfort regarding teaching SE content. Ollis (2016) reported the discomfort student teachers’ experience with topics on sexual pleasure and observed that engagement in teaching a 20-minute lesson on a positive sexual development theme—such as pleasure—resulted in increased confidence and skill to discuss sexual pleasure, orgasm, and ethical sex. The topic of student teachers’ comfort and confidence provides a prime example of the interaction of all three competency areas; knowledge, attitudes, and skills in relation to SE. Furthermore, the findings highlight that a more systemic consideration of these competency areas and teachers’ comfort and confidence to teach SE beyond the ITE context to the lived experience of school contexts, is warranted.

Discussion

Overview of Findings

This systematic review sought to investigate the empirical literature on SE provision with student teachers during ITE. Fifteen articles, reporting on thirteen studies, from predominantly Western, English-speaking contexts met the criteria for review. The findings reveal the varied nature of the provision of SE during ITE for student teachers (Rodriguez et al., 1997; McKay and Barrett, 1999; Carman et al., 2011). This is consistent with the findings of O’Brien et al.’s (2020) systematic review which similarly found variability in the provision of SE for student teachers. The current reviewed studies document an examination of SE provision at institutional/programme level, and individual student teacher level. The latter studies, in the main, reflected student teachers’ experiences regarding a particular educational input on SE, and to a lesser extent related to an examination of student teachers’ general knowledge, attitudes, or skills regarding SE.

Along with the acknowledged need to provide educational input on SE in ITE, the findings reflect that SE is perceived of as more than a stand-alone curriculum subject. Recommendations from the reviewed studies in respect of educational input provide some support for a more embedded and intersectional approach to SE provision during ITE. Similarly, O’Brien et al.’s (2020) systematic review emphasized the need for greater collaboration, integration and consistency in provision of SE at ITE. ITE in SE is typically seen within the realm of student teachers who are going to qualify as health educators, however, there is a strong argument to make that all pre-service teachers require a fundamental understanding of SE. With regards to the current review, for example, Vavrus (2009) concluded that there is a need for teacher education programmes that extend curricular attention to gender identity formation and sexuality, beyond specific SE modules, as it was suggested that this will help student teachers better understand socio-cultural factors that influence their teacher identities. Harrison and Ollis (2015) acknowledged that—as student teachers may not have engaged with critical approaches to material previously and may not have been provided with adequate time to consider these interpretations of gender and power—programmes over an extended period of time and engagement with these topics across the curriculum may facilitate increased engagement and reflection on this content. The findings provide some support that more time invested in educational input programmes may be beneficial. Courses covered over a semester (Sinkinson, 2009; Gursimsek, 2010), for example, may be more beneficial than those covered over much shorter periods (Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Ollis, 2016).

The WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) states that an important pre-requisite to teaching SE is the ability and willingness of teachers to reflect on their own attitudes toward sexuality, and social norms of sexuality. Sexual Attitudes Reassessment or values clarification has been an integral part of sexology education and training since the 1990s (Sitron and Dyson, 2009). Indeed, many accreditation bodies set a minimum number of hours in this process-orientated exploration as a requirement for sexology or sexuality education work (Areskoug-Josefsson and Lindroth, 2022). This involves a highly personal internal exploration that is directed toward helping participants to clarify their personal values and provides opportunities for participants to explore their attitudes, values, feelings and beliefs about sexuality and how these impact on their professional interactions (Sitron and Dyson, 2009). This type of input would be valuable in the ITE space. The current findings indicate that educational inputs which facilitate self-reflection and the development of critical consciousness may be particularly beneficial and necessary in supporting student teachers to teach SE. Having the space and time to engage with one’s own belief systems, and experiences, can provide student teachers with insights regarding factors that shape identity and human interaction, which are fundamental to comprehensive SE. This is an important task for teachers and previously has been identified as a gap within existing teacher education programmes (Kincheloe, 2005, as cited in Vavrus, 2009).

With regards to pedagogical approaches for teaching SE during ITE, the findings indicate that the use of tutorial groups, small group face-to-face discussions, case studies, participatory visual methods, and the inclusion of guest speakers sharing their lived experiences may create less threatening, and more comfortable, environments for student teachers to engage with SE topics on a personal level (Johnson, 2014; Brown, 2016; Goldman and Grimbeek, 2016; MacEntee, 2016). These findings are somewhat consistent with existing evidence that supports experiential and participatory learning techniques for SE (e.g., United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO], 2018; Begley et al., 2022). A lack of practical teaching experience was acknowledged by student teachers as a barrier to teaching SE topics (e.g., Vavrus, 2009; MacEntee, 2016). Given the reported (Ollis, 2016), and potential (Vavrus, 2009) benefits from engaging in the practice of teaching SE the inclusion of skills-based and practical teaching experience of SE or its proxy as a minimum, within the ITE context may be warranted.

There were some notable absences from the literature reviewed. Although there are examples of research in this review which refer to positive SE topics such as pleasure, sexual orientation, and gender identity, the studies in the main do not reflect an examination of topics fundamental to a CSE curriculum. Studies did not consider or examine the impact of the Internet and social media in relation to SE. Apart from May and Kundert’s (1996) study, the research did not reflect consideration of the provision of SE for students with diverse learning abilities and needs. Some studies considered correlational factors pertaining to student teachers’ attitudes regarding SE. These included gender, geographical location of upbringing (Gursimsek, 2010), and student teachers’ previous school experiences of SE (Sinkinson and Hughes, 2008; Vavrus, 2009). Overall, in the studies reviewed there was a dearth of research on student teachers’ attitudes about SE, and the inter-dependence of factors that may influence student teachers’ attitudes.

Given that this field of research is in its relative infancy, the findings which may be inferred from the educational input studies (Sinkinson, 2009; Vavrus, 2009; Gursimsek, 2010; Harrison and Ollis, 2015; Brown, 2016; MacEntee, 2016; Ollis, 2016), are tentative. These studies are generally informative regarding a particular topic or educational input but tend not to shed light on student teachers’ experiences. Furthermore, the findings from Carman et al.’s (2011) and Johnson’s (2014) studies, highlight the role of teacher educators in relation to SE provision being taught during ITE. Teacher educators provide vital support and facilitate new understandings and guidance in the context of SE and teacher professional development. Consistent with O’Brien et al. (2020), this review highlights the need to promote greater shared learning and evidence-based resources among teacher educators and ITE institutions.

Limitations

This systematic review should be considered in light of its limitations. There is inherent risk of bias across studies given that only peer reviewed articles written in English were reported on. Consequently, a wealth of potential research may have been precluded from review and the findings of the studies will pertain to and potentially reflect the experiences of those in the global north and/or a Westernized view. The exclusion of grey literature such as dissertations and theoretical papers is indicative of publication bias. The very process of selecting inclusion and exclusion criteria is subjective and may facilitate the exclusion of minority voices, or creative methodologies for conducting and or presenting research. Through the exclusion of position papers or articles that do not make reference to empirical data, important voices to this conversation may have been limited/excluded.

Findings were discussed in relation to the competencies outlined by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017). Although an international standard for SE, there are limitations to these guidelines. Our understanding of the provision of SE is continuously developing. In 2019, the Sex Information and Education Council of Canada (SIECCAN) updated their guidelines to include an emphasis on changing demographics in relation to sexual health, the need for sexual health educators to demonstrate awareness of the impact of colonialism on the sexual health and well-being of indigenous people, to recognize the impact of technology on sexual health education, to meet the needs of young people of all identities and sexual orientations, and the need to address the topic of consent within sex education. These aspects of SE are not reflected in the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) guidelines, nor are they reflected in the studies reviewed. This is indicative of the dynamic and complex nature of the field of SE and specifically in ITE.

Given the design of the studies we cannot conclude that ITE experiences translate to teachers’ SE teaching practice. Some studies provided examples of the barriers student teachers can face in the translation of ITE experiences to classroom experiences (e.g., MacEntee, 2016). However, other than MacEntee (2016), examples of research with both student teachers and in-service teachers were not identified nor were longitudinal studies examining the progression from ITE to classroom experiences. Notably, upon screening the abstracts, the literature tended to assess SE received by medical and health care professionals, and there were far less examples regarding research with teachers in general and as may be garnered from this systematic review, a very limited amount of research conducted with student teachers in ITE. As ITE programmes do not routinely publish their course content, there is also a chance that such professional learning and development is being provided but not being reported. Furthermore, given that research on SE within an ITE context is a relatively novel field, diverse methodological approaches have been adopted and there appears to be limited reporting of the theoretical basis informing on this work which has implications for cross-study synthesis of findings. The studies included in this systematic review, predominantly employed qualitative designs and consequently were more idiosyncratic in their selected methodological approach.

Recommendations

Drawing on the findings from the systematic review the overarching recommendation is for more quality research on teacher professional development in the context of SE during ITE. Aspects which require further research attention are outlined below.

Along with the provision of educational input on SE at ITE, an embedded and intersectional approach to SE at ITE programme-level requires further exploration. If student teachers are to meet their future school students’ SE needs, a foundational element of teacher preparation must involve actively addressing issues that are linked to teacher confidence and comfort for delivering SE. The reviewed studies broadly indicate that opportunities for critical self-reflection, practice-oriented and small-group, dialogical, inclusive and participatory pedagogical approaches may be beneficial to adopt with regards to the provision of SE during ITE, however, further robust research is required to support this.

Larger scale, multi-dimensional, integrative studies employing rigorous methodologies to assess inter alia student teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills, regarding sexuality during ITE including student teachers’ knowledge, comfort, confidence and preparedness to teach sexuality are warranted. Furthermore, research which is inclusive of both student teachers’ and teacher educators’ voices, is needed.

Adoption of a systemic approach examining individual-level and contextual factors relating to SE provision during ITE is needed to develop theoretically derived, research-informed, and evidence-based SE programmes at ITE. In order to improve the provision of SE at ITE an evaluation of provision must be in place for best practice to be achieved.

ITE provision needs to adopt a holistic approach when supporting teacher development. As documented by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2017) guidelines, this involves supporting the development and acquisition of relevant knowledge, attitudes and skills pertaining to SE. Although ITE in SE often focuses on student teachers who will qualify as health educators, it can be argued that all pre-service teachers require a fundamental understanding of SE. Furthermore, the SE provided during ITE should be nuanced to support LGBTI students, students with special educational needs and/or from diverse racial and cultural backgrounds (Whitten and Sethna, 2014; Ellis and Bentham, 2021; Michielsen and Brockschmidt, 2021). A series of indicators to assess the relevant factors pertaining to SE provision and how these indicators relate to the knowledge, attitudes, and skills required for sexuality educators would be helpful. Monitoring and evaluation of structural indicators such as the designated SE components of course programmes, whether courses are elective or core, whether practice elements are provided etc. would provide a baseline from which system change and improvements could be measured. This systematic review has provided tentative suggestions as to what may work to ensure best practice of SE during ITE. Further research is required to evaluate the outcomes associated with their implementation.

Author Contributions

AC, CM, CC, and AB were responsible for the development and design of the study and final decisions regarding the reviewed articles. AC and CM completed the initial pilot searches. AC completed the final searches and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AC, CM, and CC reviewed the articles. AC and AB developed the data extraction template. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Irish Research Council IRC Coalesce Research Award (Strand 1E—HSE—Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme) for the research study TEACH-RSE Teacher Professional Development and Relationships and Sexuality Education: Realizing Optimal Sexual Health and Wellbeing Across the Lifespan (Grant No. IRC COALESCE 2019/147).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abstrackr Abstrackr. (2010). Available Online at: http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu/account/login (accessed 2019).

Areskoug-Josefsson, K., and Lindroth, M. (2022). Exploring the role of sexual attitude reassessment and restructuring (SAR) in current sexology education: for whom, how and why? Sex Educ. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2021.2011188

Begley, T., Daly, L., Downes, C., De Vries, J., Sharek, D., and Higgins, A. (2022). Training programmes for practitioners in sexual health promotion: an integrative literature review of evaluations. Sex Educ. 22, 84–109.

Boland, A., Cherry, G., and Dickson, R. (eds) (2017). Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide, 2nd Editio Edn. London: Sage.

Bourke, A., Mallon, B., and Maunsell, C. (2022). Realisation of children’s rights under the UN convention on the rights of the child to, in, and through sexuality education. Int. J. Childrens Rights.

Brown, A. (2016). How did a white girl get aids?’ shifting student perceptions on HIV-stigma and discrimination at a historically white South African University. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 30, 94–112.

Carman, M., Mitchell, A., Schlichthorst, M., and Smith, A. (2011). Teacher training in sexuality education in Australia: how well are teachers prepared for the job?” Sexual Health 8, 269–271. doi: 10.1071/SH10126

Castillo Nuñez, J., Derluyn, I., and Valcke, M. (2019). Student teachers’ cognitions to integrate comprehensive sexuality education into their future teaching practices in Ecuador. Teach. Teacher Educ. 79, 38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.12.007

Donaldson, A. A., Lindberg, L. D., Ellen, J. M., and Marcell, A. V. (2013). Receipt of sexual health information from parents, teachers, and healthcare providers by sexually experienced US adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 53, 235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.017

Ellis, S. J., and Bentham, R. M. (2021). Inclusion of LGBTIQ perspectives in school-based sexuality education in Aotearoa/New Zealand: an exploratory study. Sex Educ. 21, 708–722. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1863776

European Expert Group on Sexuality Education (2016). Sexuality education: what is it? Sex Educ. 16, 427–431. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2015.1100599

Goldfarb, E. S., and Lieberman, L. D. (2021). Three decades of research: the case for comprehensive sex education. J. Adolesc. Health 68, 13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.07.036

Goldman, J. D., and Coleman, S. J. (2013). Primary school puberty/sexuality education: student-teachers’ past learning, present professional education, and intention to teach these subjects. Sex Educ. 13, 276–290. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2012.719827

Goldman, J. D., and Grimbeek, P. (2016). What do preservice teachers want to learn about puberty and sexuality education? an Australian perspective. Pastoral Care Educ. 34, 189–201. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2016.1204349

Gursimsek, I. (2010). Sexual education and teacher candidates’ attitudes towards sexuality. Aust. J. Guidance Counsell. 20, 81–90. doi: 10.1375/ajgc.20.1.81

Harrison, L., and Ollis, D. (2015). Stepping out of our comfort zones: pre- service teachers’ responses to a critical analysis of gender/power relations in sexuality education. Sex Educ. 15, 318–331. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2015.1023284

Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fabregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., et al. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Montréal: McGill Department of Family Medicine.

Hunt, D. (2001). Oliver Button is a Star: a Story for all Families (Video-Recording Available From Hunt & Scagliotti Productions in Association With TwinCities Gay Men’s Chorus and Whitebird). Monson, MA: Hunt & Scagliotti Productions.

Iyer, P., and Aggleton, P. (2015). Seventy years of sex education in health education journal: a critical review. Health Educ. J. 74, 3–15. doi: 10.1177/0017896914523942

Johnson, B. (2014). The need to prepare future teachers to understand and combat homophobia in schools. S. Afr. J. High. Educ. 28, 1249–1268.

Kehily, M. J. (2002). Sexuality, Gender and Schooling: Shifting Agendas in Social Learning. London: Routledge.

Ketting, E., Brockschmidt, L., Renner, I., Luyckfasseel, L., and Ivanova, O. (2018). “Sexuality education in Europe and Central Asia: recent developments and current status,” in Sex Education, ed. R. A. Benavides-Torres (New York: Nova Science Publishers), 75–120.

Ketting, E., and Ivanova, O. (2018). Sexuality Education in EUROPE and Central Asia. State of the Art and Recent Developments. An Overview of 25 Countries. Cologne: The Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA and International Planned Parenthood Federation – European Network IPPF EN.

Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., and Moher, D. (2012). Evidence summaries: the evolution of a rapid review approach. Syst. Rev. 1:10. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10

Kincheloe, J. (2005). “Critical ontology and auto/biography: being a teacher, developing a reflective teacher persona,” in Auto/Biography and Auto/Ethnography: Praxis of Research Method, ed. W. Roth (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 155–174. doi: 10.1163/9789460911408_009

Letts, W. (2002). “Revisioning multiculturalism in teacher education: isn’t it queer?,” in Getting Ready for Benjamin: Preparing Teachers for Sexual Diversity in the Classroom, ed. R. M. Kessler (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield), 119–131.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Lipkin, A. (2004). Beyond Diversity Day: a Q&A on Gay and Lesbian Issues in our Schools. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

MacEntee, K. (2016). Two years later: preservice teachers’ experiences of learning to use participatory visual methods to address the South African AIDS Epidemic. Educ. Res. Soc. Change 5, 81–95. doi: 10.17159/2221-4070/2016/v5i2a6

Mandel, L., and Shakeshaft, C. (2000). “Heterosexism in middle schools,” in Masculinities at School, ed. N. Lesko (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 75–103. doi: 10.4135/9781452225548.n4

May, D., and Kundert, D. (1996). Are special educators prepared to meet the sex education needs of their students? a progress report. J. Special Educ. 29, 433–441. doi: 10.1177/002246699602900405

McKay, A., and Barrett, M. (1999). Pre-service sexual health education training of elementary, secondary, and physical health education teachers in Canadian faculties of education. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 8, 91–101.

McNicholl, A., Casey, H., Desmond, D., and Gallagher, P. (2019). The impact of assistive technology use for students with disabilities in higher education: a systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 16, 130–143. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2019.1642395

Michielsen, K., and Brockschmidt, L. (2021). Barriers to sexuality education for children and young people with disabilities in the WHO European region: a scoping review. Sex Educ. 21, 674–692. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1851181

Milio, J., Peltier, M. J., and Hufnail, M. (1999/2002). The History of Sex (Videorecording Available From MPH Entertainment for the History Channel), Vol. 4. New York, NY: A & E Television Networks.

Murray, C. C., Sheremenko, G., Rose, I. D., Osuji, T. A., Rasberry, C. N., Lesesne, C. A., et al. (2019). The influence of health education teacher characteristics on students’ health-related knowledge gains. J. School Health 89, 560–568. doi: 10.1111/josh.12780

O’Brien, H., Hendriks, J., and Burns, S. (2020). Teacher training organisations and their preparation of the pre-service teacher to deliver comprehensive sexuality education in the school setting: a systematic literature review. Sex Educ. 21, 284–303. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1792874

Ollis, D. (2016). ‘I felt like I was watching porn’: the reality of preparing pre- service teachers to teach about sexual pleasure. Sex Educ. 16, 308–323. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2015.1075382

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., et al. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 49, 47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Pluye, P., Gagnon, M. P., Griffiths, F., and Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 529–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

Pound, P., Denford, S., Shucksmith, J., Tanton, C., Johnson, A. M., Owen, J., et al. (2017). What is best practice in sex and relationship education? a synthesis of evidence, including stakeholders’ views. BMJ Open 7:14791. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014791

Pound, P., Langford, R., and Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? a qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ Open 6:e011329. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

Rodriguez, M., Young, R., Renfro, S., Asencio, M., and Hafrher, D. W. (1997). Teaching our teachers to teach: a study on preparation for sexuality education and HIV/AIDS prevention. J. Psychol. Hum. Sex. 9, 121–141. doi: 10.1300/j056v09n03_07

Sinkinson, M. (2009). ‘Sexuality isn’t just about sex’: pre-service teachers’ shifting constructs of sexuality education. Sex Educ. 9, 421–436. doi: 10.1080/14681810903265352

Sinkinson, M., and Hughes, D. (2008). Food pyramids, keeping clean and sex talks: pre-service teachers’ experiences and perceptions of school health education. Health Educ. Res. 23, 1074–1084. doi: 10.1093/her/cym070

Sitron, J. A., and Dyson, D. A. (2009). Sexuality Attitudes Reassessment (SAR): historical and new considerations for measuring its effectiveness. Am. J. Sex. Educ. 4, 158–177. doi: 10.1080/1554612090300140

Swennen, A., and White, E. (eds) (2020). Being a Teacher Educator: Research- Informed Methods for Improving Practice. Milton Park: Routledge.

Taylor, E., and Hignett, S. (2014). Evaluating evidence: defining levels and quality using critical appraisal mixed methods tools. Health Environ. Res. Design J. 7, 144–151. doi: 10.1177/193758671400700310

Turnbull, T., Van Schaik, P., and Van Wersch, A. (2010). Adolescents preferences regarding sex education and relationship education. Health Educ. J. 69, 277–286. doi: 10.1177/0017896910369412

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO] (2009). International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education: An Evidence-Informed Approach for Schools, Teachers and Health Educators. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO] (2018). International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. Paris: UNESCO.

Vavrus, M. (2009). Sexuality, schooling, and teacher identity formation: a critical pedagogy for teacher education. Teach. Teacher Educ. 25, 383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.002

Wallace, B. C., Small, K., Brodley, C. E., Lau, J., and Trikalinos, T. A. (2010). “Modeling annotation time to reduce workload in comparative effectiveness reviews,” in Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Health Informatics Symposium IHI’10, Arlington, VA, 28–35. doi: 10.1145/1882992.1882999

Walker, R., Drakeley, S., Welch, R., Leahy, D., and Boyle, J. (2021). Teachers’ perspectives of sexual and reproductive health education in primary and secondary schools: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Sex Educ. 21, 627–644. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2020.1843013

Whitten, A., and Sethna, C. (2014). What’s missing? Anti-racist sex education! Sex Educ. 14, 414–429. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2014.919911

World Health Organisation [WHO]/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA (2010). Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe: A Framework for Policy Makers, Educational and Health Authorities and Specialists. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education – BZgA.

World Health Organisation [WHO]/Regional Office for Europe & Federal Centre for Health Education BZgA (2017). Training Matters: A Framework of Core Competencies for Sexuality Educators. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education – BZgA.

WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA (2010). Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe: A Framework for Policy Makers, Educational and Health Authorities and Specialists. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education.

WHO Regional Office for Europe, and BZgA (2017). Training Matters: A Framework of Core Competencies for Sexuality Educators. Cologne: Federal Centre for Health Education.

Appendix A

Explanation of MMAT categorization (Hong et al., 2018).

Keywords: systematic review, sexuality education, student teacher, initial teacher education, comprehensive sexuality education, sex education

Citation: Costello A, Maunsell C, Cullen C and Bourke A (2022) A Systematic Review of the Provision of Sexuality Education to Student Teachers in Initial Teacher Education. Front. Educ. 7:787966. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.787966

Received: 01 October 2021; Accepted: 08 February 2022;

Published: 07 April 2022.

Edited by:

Manpreet Kaur Bagga, Partap College of Education, IndiaReviewed by:

Laura Sara Agrati, University of Bergamo, ItalyJennifer Oliphant, University of Minnesota Health Twin Cities, United States

Teresa Vilaça, University of Minho, Portugal

Jacqueline Hendriks, Curtin University, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Costello, Maunsell, Cullen and Bourke. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Aisling Costello, YWlzbGluZy5jb3N0ZWxsb0B0dWR1Ymxpbi5pZQ==

Aisling Costello

Aisling Costello Catherine Maunsell

Catherine Maunsell Claire Cullen3

Claire Cullen3