- Minerva University, San Francisco, CA, United States

Non-cognitive skills are essential for success in a variety of settings but are not commonly taught and assessed in undergraduate curricula. The challenge for curricular integration of non-cognitive skills stems from varying interpretations of what it means to apply a specific skill effectively. In addition, teaching these skills requires going beyond the foregrounded academic content in traditional coursework. At Minerva University, we articulate core non-cognitive skills precisely and transparently as learning outcomes to guide the design of courses and assessments. We integrate these skills into the academic curriculum and student life alongside traditional learning outcomes. Students are introduced to these outcomes in their first year and continue to apply them throughout their 4 years, receiving feedback and scores across academic, disciplinary, and real-world, experiential learning contexts. We provide examples of the Learning Outcomes, detailing their introduction and application in various contexts across the 4-year arc Students’ college experience. We identify aspects of our approach that can be generalized and implemented in different settings, from individual courses to programs, departments, or entire institutions.

Introduction

Non-cognitive skills can be understood as the set of behaviors, skills, attitudes, and strategies that underlie Students’ actions toward their academic, personal, and professional responsibilities and goals (Farrington et al., 2012; Gutman and Schoon, 2013). They are distinguished in the literature from skills such as numeracy and literacy that traditional cognitive tests have measured, although all of these skills require the development of cognitive processes (Smith, 2020). Unlike traditional cognitive skills, non-cognitive skills are more malleable and independent from context; they improve one’s ability to learn, apply other skills, and adapt to changing needs (Hagel et al., 2019).

The importance of non-cognitive skills has been emphasized by developmental psychologists since the early twentieth century. Lev Vygotsky theorized that learning is a social process that requires interaction and is influenced by culture, resulting in the development of behaviors and attitudes that allow for more complex thinking (Blake and Pope, 2008). Further strengthening the importance of non-cognitive skills, Bruner (1961) argued that education aims not to impart knowledge but to facilitate thinking and problem-solving skills that students can then transfer to a variety of situations. More recent studies show that the development of non-cognitive skills positively impacts Students’ academic outcomes and future professional readiness (Kyllonen, 2012; Gutman and Schoon, 2013; Kautz et al., 2014). Indeed the most in-demand competencies across the labor market include communication, teamwork, leadership, problem-solving, and complex thinking (Carnevale et al., 2020).

Higher education institutions are uniquely situated to equip students with non-cognitive skills and competencies. Still, despite the increasing evidence of the importance of such skills in the workplace (Mercer et al., 2019), many institutions have not prioritized teaching them, where they remain part of the hidden curriculum. Skills such as leadership and teamwork are meant to be gained as students participate in extracurricular clubs and athletics. Students may voluntarily participate in skill-building workshops and seminars at college learning centers or be compelled to join due to significant issues in academic standing or high school preparation (Truschel and Reedy, 2009). In either case, participation in these programs is seen as co-curricular and is neither assessed nor reported on transcripts. This results in students not fully appreciating the value of these skills and services (Gutman and Schoon, 2013; Mintz, 2019). There is an assumption that students will somehow learn these skills as they progress through college. In reality, many students who excel at applying non-cognitive skills learned them before college through attending well-resourced or elite high schools and extracurricular learning programs (Tyson, 2014; Paul, 2015).

The challenge of promoting non-cognitive skill development starts with defining what is to be taught. There is no universal agreement on what skills constitute this set (Humphries and Kosse, 2016). Non-cognitive skills are multidimensional and interdisciplinary, integrating aspects of the social and psychological spheres (Farrington et al., 2012) that apply to processes of learning and working across disciplines. Furthermore, teaching these skills necessarily requires going beyond the foregrounded academic content. Finally, assessing Students’ non-cognitive skills in typical academic courses remains unsystematic, subjective, and ad hoc. Without a formal curriculum, it cannot be ensured that these skills are taught, learned, and practiced effectively and consistently.

At Minerva University, we explicitly teach non-cognitive skills, revealing much of the traditionally hidden curriculum. Here we describe our highly structured approach to integrating the learning and assessment of non-cognitive skills throughout our curriculum, both inside and outside the classroom.

Pedagogical Framework and Principles

Minerva University is a primarily undergraduate institution where all classes are taught in small seminars using active learning pedagogy via a sophisticated digital learning platform. Students participate in a global rotation program, living together in different global cities during their studies (more details on these aspects of Minerva’s model are in Supplementary Material 1). Minerva’s framework for integrating academic coursework with student life and career development programming to foster the development of non-cognitive skills is defined by three principles:

Defining Core Skills as Learning Outcomes

Minerva has identified a set of broadly applicable skills and concepts that are paramount for the next generation of leaders, innovators, and engaged global citizens. For each concept or skill, we have articulated a measurable Learning Outcome (LO), a statement of what students should know and be able to do as a result of applying that concept or skill. The LO statement ensures that all stakeholders use the same definition. All LOs also have hashtag handles, a shorthand that makes them easier to discuss and remember across teams. For example, the learning outcome, “identify and correct logical fallacies,” is shorthanded to #fallacies. While many LOs are knowledge-based, several LOs are directly relevant to non-cognitive skills. For example, two non-cognitive LOs are “follow through on commitments, be proactive, and take responsibility” (#responsibility) and “use emotional intelligence to interact effectively” (#emotionaliq).

In the context of academic coursework, the LOs are derived from and organized under four competencies: Thinking Critically, Thinking Creatively, Interacting Effectively, and Communicating Effectively. The Foundational, cross-contextual LOs span all dimensions of these competencies without significant redundancy. They each capture specific aspects of the core competencies while remaining broadly applicable across a wide range of disciplines and domains of inquiry. The full list of nearly eighty learning outcomes, organized into sub-competencies under the four core competencies, is provided in Supplementary Material 2.

Similarly, staff and deans responsible for student experience, career services, and student wellbeing at Minerva identified five competencies called Integrated Learning Outcomes (ILOs) that are pertinent to personal and character development. These are Self-Management and Wellness, Interpersonal Engagement, Intercultural Competency, Professional Development, and Civic Responsibility. They identified a subset of Foundational LOs relevant to each ILO, as indicated in Supplementary Material 3. Students are expected to engage in and improve upon these ILOs throughout their Minerva journey.

Integration Between Academics and Real-World Settings

While introducing students to the Foundational LOs associated with core skills in the classroom, we provide opportunities to apply and practice these in real-world contexts. This is founded on the belief that learning is truly successful when learners use concepts and skills across diverse settings. For instance, the Integrated Learning Course is a four-semester-credit course delivered over 4 years that provides students with tools to face the challenging process of personal and character growth and prepares students for effective citizenship in a diverse, multicultural society. Each semester, students participate in structured projects and community immersion experiences to orient themselves to the culture in their rotation cities. In this manner, students deepen their understanding of LOs, while earning course credit for engaging with relevant experiential learning opportunities. Another example is career coaching, where students set goals and reflect on their non-cognitive skill development, such as self-management, relating to others, and teamwork—critical to their employment and life success. Along their 4-year journey, coaches continue to help students apply the LOs in professional contexts, including networking, developing application materials, and interviewing.

Multidimensional Channels for Reflection and Feedback

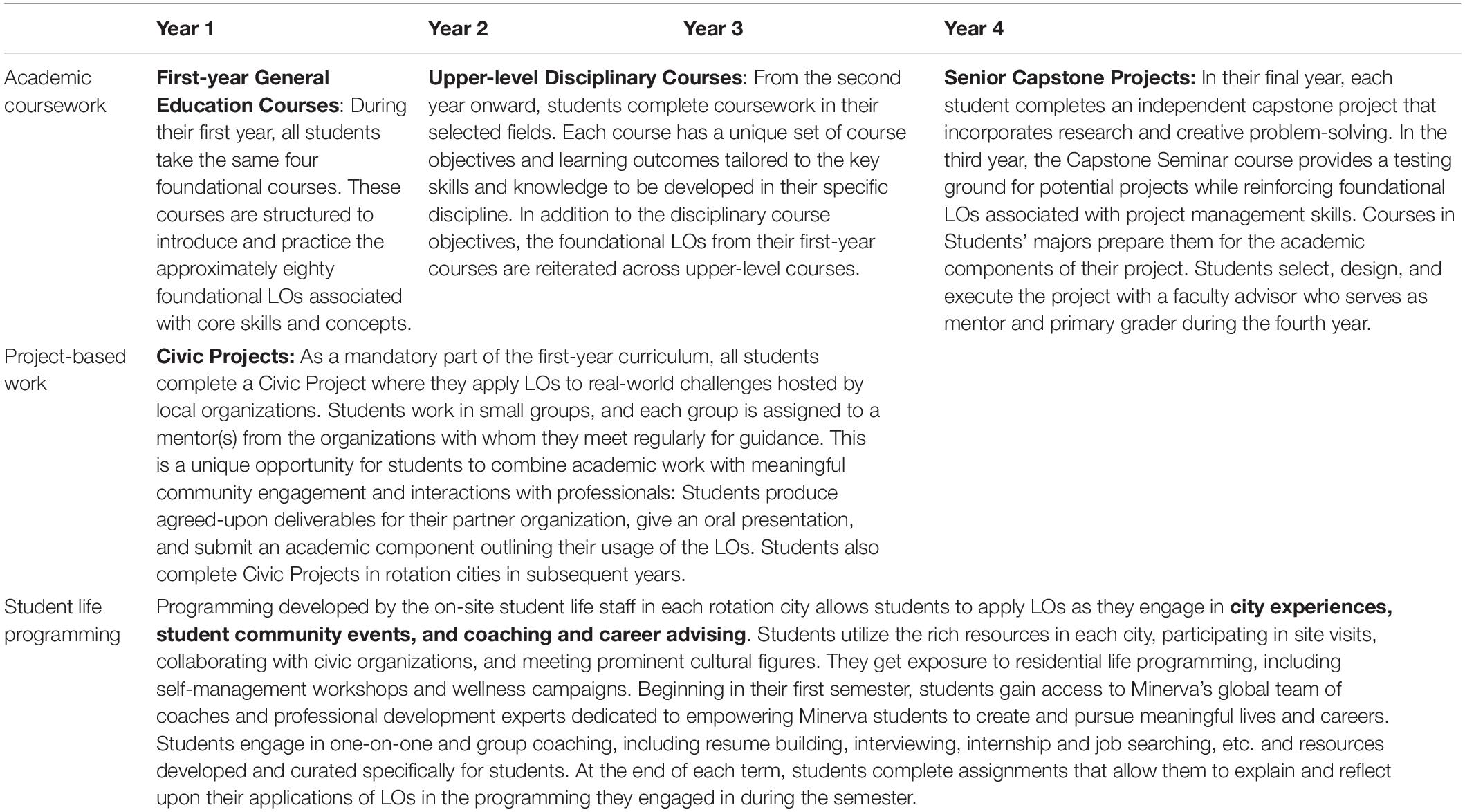

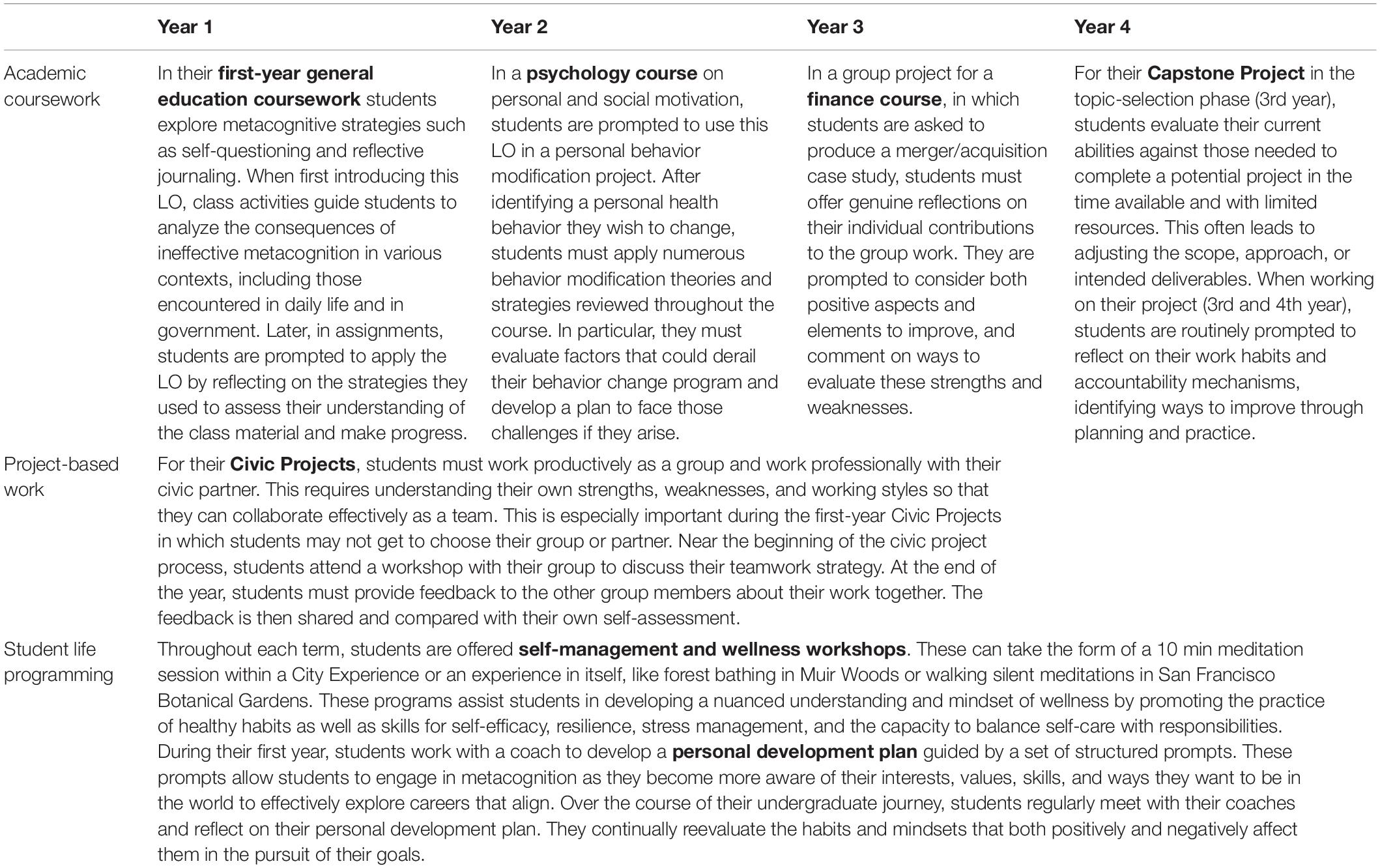

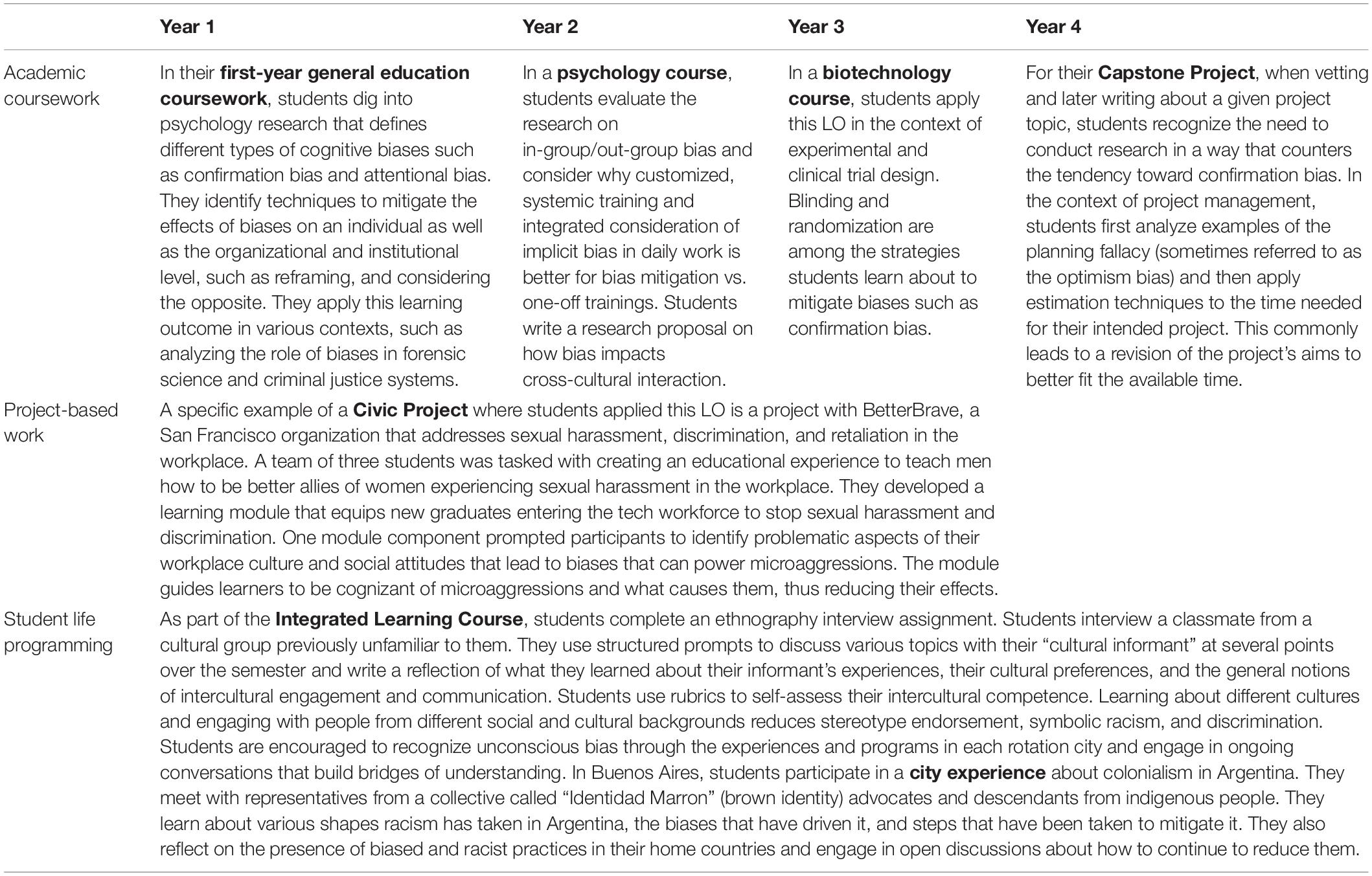

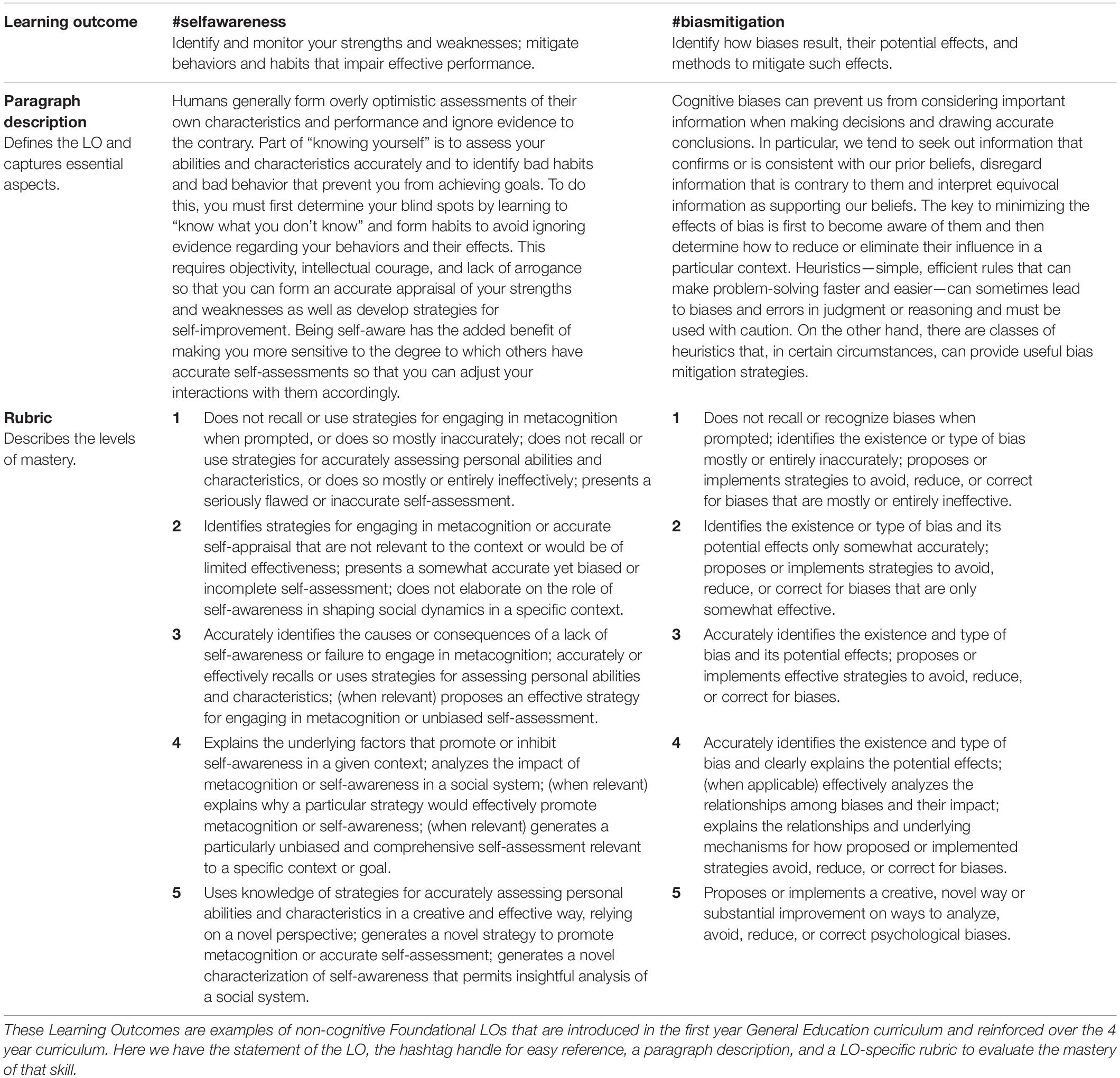

In addition to the statement and hashtag handle, each Foundational LO has a paragraph description and a 5-point rubric (Supplementary Material 4) that makes explicit the criteria for evaluating Students’ work. Table 1 displays this information for two LOs, #selfawareness and #biasmitigation, which we discuss in more detail in the next section. The information for each LO is readily accessible to faculty, staff, and students. To promote reflection, all assignments at Minerva require students to tag their LO applications with footnotes or provide explanatory analysis in Supplementary Material. Typically 2–3 sentences, the intention of these annotations is for students to reflect on their applications of the LOs and explain what makes these applications strong, drawing from the rubrics. Regularly tagging LOs in this fashion is an excellent way for students to engage in metacognition and evaluate the strength of their understanding and applications. Next, instructors apply the rubrics when grading coursework, supporting consistency, and making grading more objective (Allen and Tanner, 2006). Instructors typically provide a written comment explaining what the student had done well and what they could improve. Students receive this formative feedback for their work during class sessions and on assignments. Easy access to rubrics also allows students to better understand and implement instructor feedback.

Table 1. This table presents in full the two the Learning Outcomes (LOs) shorthanded #selfawareness and #biasmitigation.

In parallel, as Minerva’s experiential programs incorporate 1:1 coaching, students receive actionable feedback on their application of non-cognitive skill associated LOs, in experiences such as job searches, networking, project-based learning, or formal professional experiences such as internships. Finally, each student completes a self-assessment to reflect on their current skills and abilities pertaining to specific ILOs at the end of each year, guided again by clearly defined rubrics (Supplementary Material 5). This self-assessment allows students to set goals, monitor, and reflect upon their progress.

Learning Environment and Pedagogical Format

Minerva’s student body is extraordinarily international, relative to standard U.S. universities. More than 80% of Minerva’s student population comes from outside the United States. Considering the 721 students in the five cohorts spanning the classes of 2020–2024, 36% of our students come from Asia; 23% from Europe; 22% from North America; 13% from Africa; and 6% from South America. English is not the first language for over 60% of our students, and about 30% of our students come from International Baccalaureate programs. Of all Minerva students who have matriculated, about 54% identify as female and about 46% as male. In addition to being highly international, the student body is also notable for its high economic diversity. Nearly 80% of Minerva students receive some sort of financial support in the form of loans, work-study, and/or scholarships.

Minerva incorporates the pedagogical framework described in the previous section through a hybrid model where classroom instruction is virtual while students live together and engage in real-world activities and events that supplement the curriculum. Academic instruction is remote, and Minerva’s on-site Student Life staff supports students in residential life, career and professional development, integrated learning skills, and cultural and civic work in each city. These programs complement the in-class curriculum and help students get the most of their experiences in their cities by developing real-life skills and connections needed to pursue their career and personal goals. All faculty and staff receive extensive training, including on the application and assessment of Foundational LOs.

To illustrate Minerva’s model more extensively and demonstrate it in action, we further define some key elements and components of the learning environment that foster the model described above. As detailed in Table 2, we introduce students to the Foundational LOs during their first year of study when taking the same 4-year General Education courses. Beyond the first year, the LOs are scaffolded and incorporated throughout the entire curriculum, reinforced over time, and regularly practiced in coursework, projects, and extracurricular activities. For instance, as students take upper-level courses in their selected majors, they continue to apply Foundational LOs from their first year, practicing these skills in the context of their disciplines and receiving scores and feedback on their applications. LO scores are updated daily and shown to students on a dashboard in their Learning Management System. The dashboard shows all prior scores, associated feedback, and a running average. Therefore, students can track their growth in each LO to see how they progress in individual courses and overall over 4 years. Tables 3, 4 elaborate on the two non-cognitive skill LOs introduced earlier, #selfawareness and #biasmitigation, detailing their introduction and application in various contexts across the 4-year arc of their college experience and channels for feedback.

Results to Date and Planned Data Collection

When assessing non-cognitive skills, quantitative metrics, such as objective scores and tests, are informative but must be balanced with the depth and insights of more subjective and qualitative data, such as self-report, observation, and perception (Garcia, 2014). To evaluate how well our programs are meeting intended outcomes, we analyze various types of data, including student LO rubric scores, surveys of internal and external stakeholders (e.g., faculty and staff; civic project partners and internship managers), and student self-assessment and reflection.

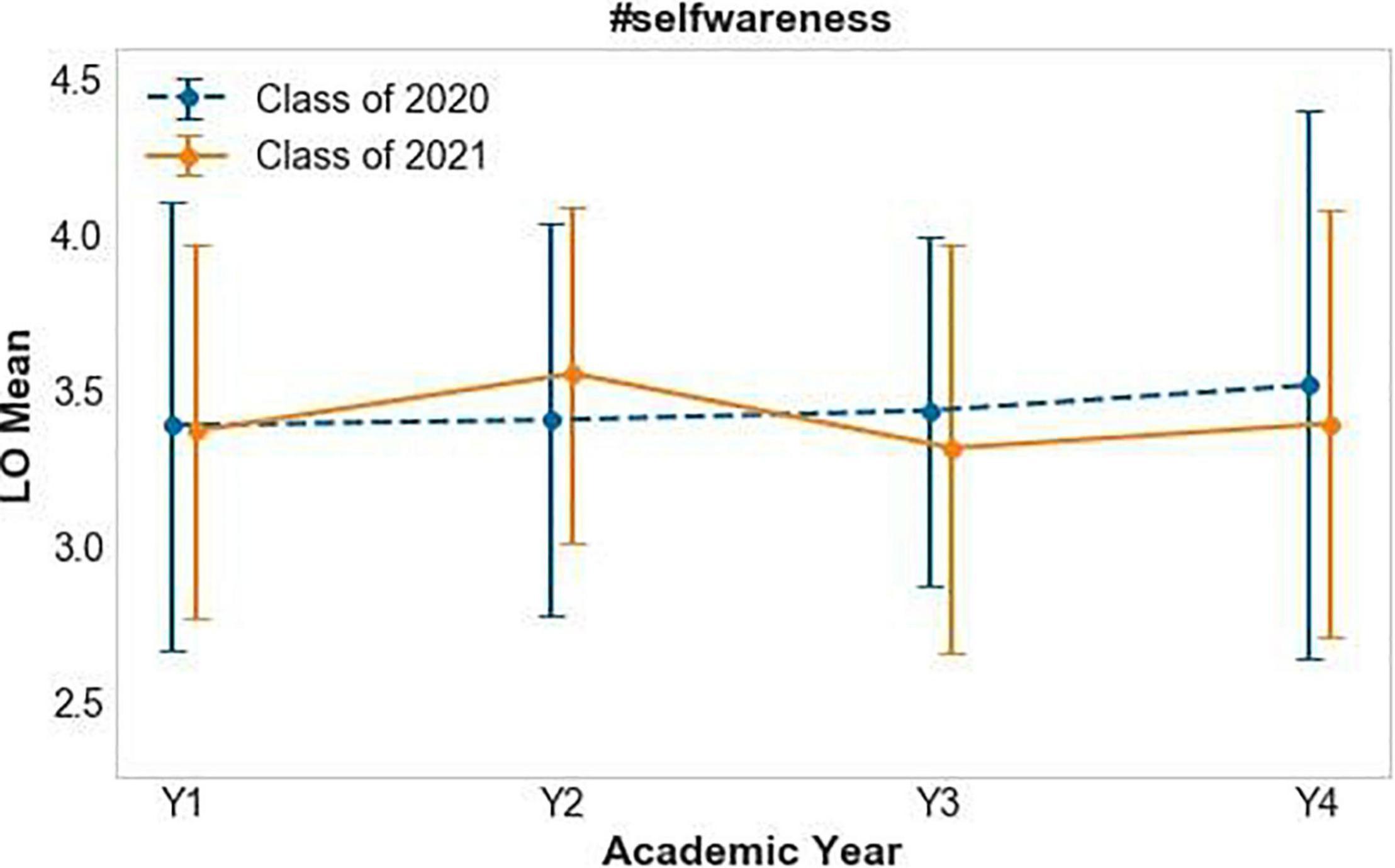

Our scaffolded curriculum allows us to evaluate Students’ growth by tracking student scores on Foundational LOs over 4 years. However, a few caveats make current LO data challenging to interpret meaningfully. Being such a new and small institution, sample sizes are limited. Additionally, there have been significant revisions to the course policies, curriculum, LO definitions and rubrics, and assessment practices, especially in the early years as Minerva created its curriculum for the first time. For instance, we do not currently have consistent 4-year data for #biasmitigation because this LO was introduced starting in 2018, resulting from a restructuring of other previous bias-related LOs that were merged. In Figure 1 we present the scores on #selfawareness earned by two cohorts over 4 years. While no clear trend of change in mean or variation in LO scores over time emerges from these two cohorts, this nonetheless serves as an illustrative example of the type of data we are actively collecting and using to inform our approach. Refinements to our curriculum and policies are getting asymptotically smaller year after year, and we will have more comparable data from multiple cohorts, allowing us to identify patterns in student performance and mastery of these skills.

Figure 1. Mean and standard deviation of scores on #selfawareness earned by two cohorts, the class of 2020 and the class of 2021 (who began in the fall of 2016 and 2017, respectively). Numbers of students in each year and score count are presented in Supplementary Material 8.

More generally, the assessment of non-cognitive skill development is challenging. These skills are, by nature, subjective to the perceptions of the observer. While we mitigate this using clearly defined LOs and rubrics, there is bound to be some variation. Additionally, some non-cognitive skills take considerable time and practice to develop. At the moment of project or program completion, it is difficult to know if students experienced growth and whether it is lasting. Finally, control groups are needed to determine whether any change resulted from our curriculum or our Students’ typical growth and development.

We recently initiated the implementation of two additional tools to measure non-cognitive skill development (1) A self-assessment survey (Supplementary Material 5) which students complete at the start of their first year and then at the end of each academic year. Students use a rubric to reflect on their current skills and abilities within specific ILOs and develop an action plan to help them grow within those LOs. (2) The Intercultural Effectiveness Scale (IES) (Kozai Group, 2009), a psychometric instrument designed for the assessment of intercultural competencies, which students complete at the start of their first year and upon graduation. The IES report provides students feedback on their non-cognitive skills related to intercultural effectiveness such as cross-cultural communication, interpersonal engagement, and emotional resilience. We started administering both tools 2 years ago with the incoming class that will graduate in 2023. This means that these students will take the final post-graduation surveys in 2 years. We will then be positioned to compare pre- and post-program data. In conjunction with 4-year LO scores, these data will identify areas that may require improvement, informing our efforts to iterate and adjust our curriculum and programming to support non-cognitive skills development better.

Finally, surveys to assess perceptions of external stakeholders provide indirect evidence of student success and areas of strength in student non-cognitive skill development. Minerva’s employer-facing team surveys internship managers of Minerva students at the end of each year, assessing their experience with the students and the quality of their work output. From 2018, 2019, and 2020 we gathered responses from 118 external employers. These employers include high-level executives from around the world including CEOs, MDs, CSOs. Of these, 62% responded that their Minerva intern was outstanding and ranked in the top 5% compared to previous interns. Testimonials from the respondents highlighted adaptability and cultural dexterity, “What I was most impressed by is her ability to be flexible and work with a variety of student skill levels. It was also helpful that she has had travel and culture experience as we have students from many parts of the world and she is able to relate to them,” and growth mindset, “[Student] brought a positive attitude and a passion for giving and seeking strong feedback, aka an attitude steeped in growth and continuous improvement of himself and his peers.”

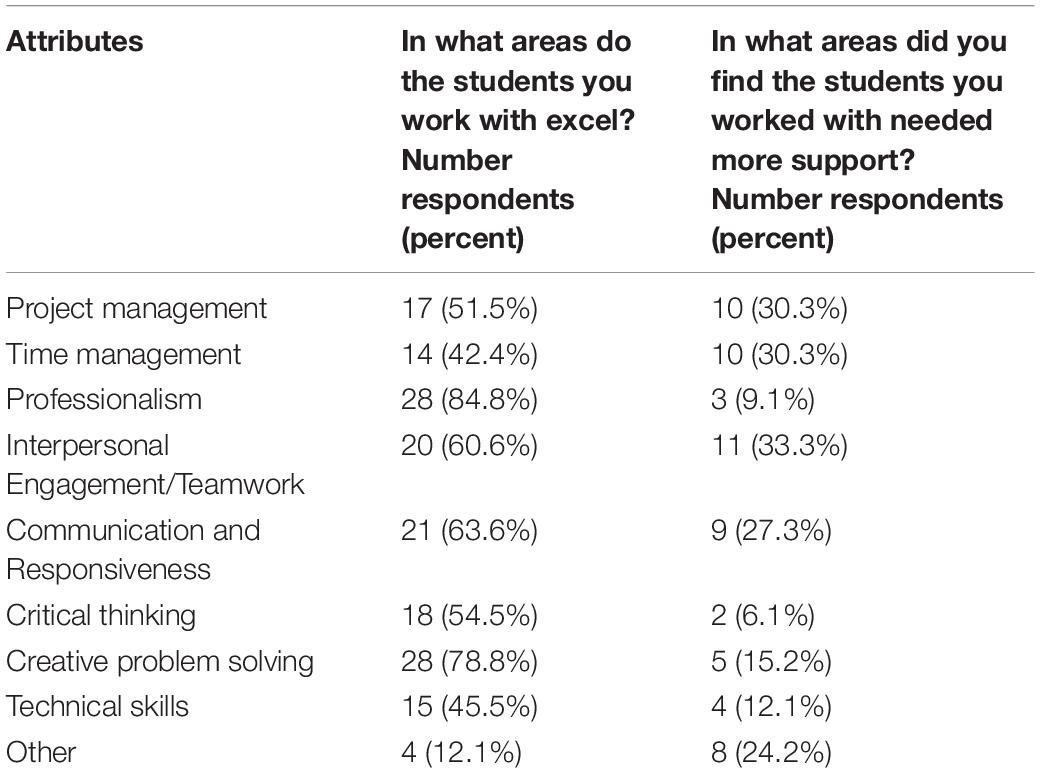

Similarly, at the end of the Student’s first academic year, we ask mentors from Students’ Civic Projects (described in Figure 1) to evaluate the students in their teams. Our Spring 2020 survey received responses from 33 professionals working in the San Francisco area, in industries ranging from financial services to hospitals and non-profits. From a list of attributes, partners selected areas that their mentees excelled in Table 5. The most commonly chosen attributes were professionalism (85%), creative problem solving (79%), and communication and responsiveness (63%). The attribute identified as needing the most support was time management (42%). So while, on average, our first-years impressed the partners with their professional behavior and creativity, they still have room for growth with respect to time management. This data will inform programmatic revisions, such as defining learning outcomes that specifically target this skill. Overall, Minerva students receive overwhelmingly positive feedback from external partners.

Table 5. Survey responses from 33 civic partners who mentored fist year students during their year long civic project.

Implications and Limitations

Minerva is a new and innovative institution, and evidence-based iteration is the cornerstone of our programmatic approach as we build and improve processes, learning outcomes, and programs each year. We collect various data, including student feedback (such as end-of-course surveys and focus groups), LO rubric scores, and information from internal and external stakeholders (e.g., faculty and staff; civic project partners and internship managers) to evaluate how well our programs are meeting intended outcomes. For instance, we use student outcome data and faculty feedback to continually re-evaluate the usefulness and relevance of Foundational LOs. As a result, the LOs have evolved from a list of over one hundred outcomes to the current, narrower, and more clearly defined list of fewer than eighty outcomes. The Integrated Learning Course provides another example. The course was originally designed to support students in acculturating to the different global rotation cities. Many additional elements have been added over time to broaden its scope and include more non-cognitive skills that students, staff, faculty, and external stakeholders identified as necessary for student success.

The small size of our institution makes implementing this integrated, scaffolded approach more tractable. Our faculty, staff, and students have joined Minerva, in part, because of its innovative nature, and they are open to and excited by change, making it easier for the institution to move coherently and quickly when change is desired. Minerva is also unique in that we are a highly selective, needs-blind, and majority international institution, accepting under 2% of applicants for the past several years from approximately 80 countries, resulting in a diverse, high-performing student body upon entry into the University. Therefore the scale of our approach is not necessarily replicable at other institutions. Nonetheless, the underlying principles remain the same. Other programs can adapt our framework to fit their particular situations, spanning as many or as few courses and co-curricular experiences as practical and potentially expanding over time. Importantly, the formative assessment needed to teach and assess non-cognitive skills effectively requires courses to move beyond traditional ways of measuring student learning. This might involve adding reflections at the end of exams, assessment of progress on assignments, and assignments that explicitly require the use of non-cognitive skills. Many skills related to communication and interaction can also be practiced and assessed during in-class activities, which requires courses to move away from the traditional lecture format. At most universities, teaching centers and career services departments are available as a resource for faculty and departments interested in integrating non-cognitive skill development into their courses and curricula.

Minerva’s newness and inclination toward iteration pose a challenge to the assessment of the effectiveness of programs. Changes in student experience over the years, making comparative data challenging to identify. Recently, as our curriculum and policies have stabilized, we anticipate that we will be able to make more year-over-year comparisons. More broadly, the assessment of non-cognitive skills remains challenging. These skills are, by nature, subjective to the reality and perceptions of the observer. We mitigate this using rubrics and learning outcomes, but we cannot be entirely objective. Additionally, some non-cognitive skills need to develop over time. At the moment of project or program completion, it is difficult to know if one experienced growth and whether it is lasting or transferred to other projects. At this time, we do not have a control group with which to compare our students, and we cannot say definitively if that growth was a result of our curriculum or a result of our Students’ typical growth and development. We plan to further investigate how to best measure this growth and transfer going forward.

In sum, by integrating academics with community experience and professional development and coaching, higher education can promote non-cognitive skills that typically take years of experience to acquire. This approach relies on a clear set of goals, coordination and integration between faculty and student life staff, with ample feedback, reflection, and open dialogue.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

AA: project lead, writing, review, and editing (all sections). CN: literature review, table creation, and editing. AT: writing (academic model), tables creation, review, and editing. GS: writing (introduction, limitations), review, and editing. SK: writing (implications, capstone project) review and editing. RK: writing (coaching and professional development) review and editing. MS: writing (student life programming) and review. KKW: writing (limitations, student life programming) and review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2022.782214/full#supplementary-material

References

Allen, D., and Tanner, K. (2006). Rubrics: tools for making learning goals and evaluation criteria explicit for both teachers and learners. CBE Life Sci. Edu. 5, 197–203. doi: 10.1187/cbe.06-06-0168

Blake, B., and Pope, T. (2008). Developmental psychology: incorporating piaget’s and vygotsky’s theories in the classroom. J. Cross-Discip. Perspect Edu. 1, 59–67.

Carnevale, A. P., Fasules, M. L., and Campbell, K. P. (2020). Workplace Basics: The Competencies Employers Want. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

Farrington, C. A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T. S., Johnson, D. W., et al. (2012). Teaching Adolescents to Become Learners: The Role of Noncognitive Factors in Shaping School Performance: A Critical Literature Review. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Garcia, E. (2014). The Need to Address Non-Cognitive Skills in the Education Policy Agenda. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute.

Gutman, L. M., and Schoon, I. (2013). The Impact of Non-Cognitive Skills on Outcomes For Young People. A Literature Review. London: Institute of Education University College London.

Hagel, J., Brown, J. S., and Wooll, M. (2019). Skills Change, but Capabilities Endure: Why Fostering Human Capabilities First Might be More Important Than Reskilling in the Future of Work. London: Deloitte Insights.

Humphries, J. E., and Kosse, F. (2016). On The Interpretation of Non-Cognitive Skills – What is Being Measured and Why it Matters. in (Berlin, Germany). Available online at: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/148554/1/875032826.pdf (accessed June 19, 2021) doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2879804

Kautz, T., Heckman, J. J., Diris, R., Weel, B. T., and Borghans, L. (2014). Fostering and Measuring Skills: Improving Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills to Promote Lifetime Success. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online at: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w20749/w20749.pdf (accessed June 19, 2021).

Kyllonen, P. C. (2012). The importance of higher education and the role of noncognitive attributes in college success. Pensam. Educ. 49:17. doi: 10.7764/PEL.49.2.2012.7

Mercer, S., Hockly, N., Stobart, G., and Galés, N. L. (2019). Global Skills – Creating Empowered 21st Century Citizens. Oxford: Oxford University.

Mintz, S. (2019). How to Help Academically Struggling Students | Inside Higher Ed. Available Online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/higher-ed-gamma/how-help-academically-struggling-students (accessed July 12, 2021)

Paul, A. M. (2015). Opinion | Are College Lectures Unfair? The New York Times. 12. Available Online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/13/opinion/sunday/are-college-lectures-unfair.html (accessed August 21, 2021)

Smith, M. (2020). Becoming Buoyant: Helping Teachers and Students Cope with the Day to Day. Milton Park: Routledge.

Truschel, J., and Reedy, D. L. (2009). National survey-what is a learning center in the 21st century? Learn. Assist. Rev. 14, 9–22.

Keywords: non-cognitive, skill development, collaborative design, reform and innovation, Minerva University, undergraduate, transferable skill development

Citation: Ahuja A, Netto CLM, Terrana A, Stein GM, Kern SE, Steiner M, Kim R and Krupnick Walsh K (2022) An Outcomes-Based Framework for Integrating Academics With Student Life to Promote the Development of Undergraduate Students’ Non-cognitive Skills. Front. Educ. 7:782214. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.782214

Received: 24 September 2021; Accepted: 20 January 2022;

Published: 03 March 2022.

Edited by:

Alexander Muela, University of the Basque Country, SpainReviewed by:

Chetan Sinha, O.P. Jindal Global University, IndiaAshley R. Vaughn, Northern Kentucky University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Ahuja, Netto, Terrana, Stein, Kern, Steiner, Kim and Krupnick Walsh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Geneva M. Stein, Z3N0ZWluQG1pbmVydmEuZWR1

Abha Ahuja

Abha Ahuja Camila L. M. Netto

Camila L. M. Netto Alexandra Terrana

Alexandra Terrana Geneva M. Stein

Geneva M. Stein Suzanne E. Kern

Suzanne E. Kern Mara Steiner

Mara Steiner Rachel Kim

Rachel Kim Kayla Krupnick Walsh

Kayla Krupnick Walsh