- 1Department of Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 2Centre for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 3Research Focus Area Optentia, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

- 4Center for Technology Experience, AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH, Vienna, Austria

- 5University College of Teacher Education Styria, Styria, Austria

The idea of inclusion in the sense of participatory access to educational opportunities is widely acknowledged and implemented within the pedagogical discourse. Nevertheless, ensuring social participation of students with and without special education needs in learning situations continues to be challenging. The present study examines promoting and hindering factors for social inclusion with a focus on students with special educational needs. Therefore, semi-structured interviews regarding students’ (n = 12 students with SEN, 12 students without SEN), parents’ (n = 24), and teachers’ (n = 6 regular teachers, 6 special need teachers) perceptions of promoting educational characteristics that might influence students’ inclusion in everyday school life are analyzed through thematic analysis. The findings provide a wide range of pedagogical interventions that have the potential to promote inclusive education processes on educational, intrapersonal, and interpersonal levels as well as regarding different actors who are involved.

Introduction

Several researchers have pointed out that students labeled with special educational needs (SEN) experience a lack inclusion (Koster et al., 2009; Bossaert et al., 2013; Schwab, 2018b; Hassani et al., 2020). Additional studies have demonstrated that when compared to their peers, the wellbeing of students with SEN has reported being less (e.g., Skrzypiec et al., 2016; McCoy and Banks, 2017); whereas other studies could not find any evidence (e.g., Goldan et al., 2021). Nevertheless, there is a consensus that wellbeing is linked to self-esteem, happiness, and further social, emotional, and psychological outcomes (Allen et al., 2018), which are important indicators for inclusion (Gökmen, 2021). Transnational agreements (e.g., UNESCO, 1994; UN, 2006) have therefore urged policymakers to foster the inclusion of all students in mainstream schools. Yet, the concept of inclusion does not seem to be consistent or clearly defined in the literature (Nilholm and Göransson, 2017). Nilholm and Göransson (2017) conducted a review and classified different definitions of inclusion into four main types, namely, inclusion as (a) the placement of students with SEN in mainstream classrooms; (b) meeting the social/academic needs of students with SEN; (c) meeting the social/academic needs of all students; (d) the creation of communities with specific characteristics (p. 441). For the proposes of the current paper, the concept of inclusion introduced by Felder (2018) is used, which emphasizes that inclusion consists of two interacting dimensions: the societal and the interpersonal. While the societal aspect refers to the larger social context, the interpersonal aspect refers to relationships built on interactions and emotions. Children and youth spend a considerable time of their life in school. Therefore, research and educational policy have by now acknowledged the necessity of school becoming a place where all students have the same chances (UNESCO, 2020) and feel included. Like the concept of inclusion also the concept of inclusive education, as a strategy to promote inclusion, is interpreted in various ways, thereby leading to different approaches in educational policy and practice. In the current study, inclusive education is understood as “(…) a systemic approach to education for all learners of any age; the goal is to provide all learners with meaningful, high-quality educational opportunities in their local community, alongside their friends and peers” (Watkins, 2017, p. 1). Therefore, the importance that “Inclusive schools (…) adapt the school environment to meet the needs of an individual student, rather than making the student fit in the school system” (Erten and Savage, 2012, p. 222) needs to be emphasized at this point. In Austria, where the current study was conducted, students with SEN attend so-called inclusive classes in mainstream schools or self-contained special schools. Schwab (2018a) provides an overview and notes that around 36% of students with SEN in Austria still attend the latter schools, which is a high number given the need for an inclusive approach in the school system. That said, about 64% of students with special educational needs attend inclusive classes, which in turn means that a closer look at their specific situation is needed.

A Framework for Inclusive Education

Even though past research has made considerable efforts to foster the inclusion of students with SEN, the measures to overcome these difficulties remain to be a challenge. Over the last decades, several studies have been undertaken to identify the components needed to build a framework for inclusive education to foster social inclusion. Little (2017) argues that in educational settings, it is important to offer opportunities that foster involvement and particularly encourage those students who have difficulties engaging with their peers in socially anticipated ways. These educational opportunities comprise different aspects such as social participation, students’ sense of belonging to the school, and wellbeing (Hascher, 2017; Juvonen et al., 2019). Koster et al. (2009) reviewed past research and name friendships/relationships, interactions/contacts, perception of the student with SEN, and acceptance by classmates to be considered when speaking of social inclusion (see also Bossaert et al. (2013)). Previous research conducted by Janice et al. (2017) further highlights that in schools, “(a) goal setting and planning learning opportunities; (b) incorporating all young children in the classroom; (c) utilizing tiered models of support; (d) measuring and assessing inclusion; and (e) training competent classroom teams and staff” (p. 59) play a crucial role in providing high-quality inclusion.

It is essential to note that inclusion still poses a challenge for all stakeholders in the educational system, and additional evidence is needed for the requirements for an inclusive school. These components promising a successful inclusion need to be defined by all people involved in the school system. For example, Schwab et al. (2019) conclude in their study that multiple perspectives are necessary when assessing and analyzing social participation since different actors have varying experiences and diverse views of the same situation. Hence, apart from teachers, students and their parents need to be involved in order to provide a comprehensive perspective that will allow designing a school that responds to all needs. With this understanding, the current paper takes these voices into account and asks students with and without SEN, their parents, and teachers about promoting factors of successful inclusion of students with SEN.

Conditions for Successful Inclusion: Role of Students, Parents, and Teachers

Lower social inclusion of students with SEN could take place owing to reasons ranging from educational factors such as class composition, inclusive didactics, and classroom practices to parents’, teachers’, and classmates’ attitudes as well as individual factors such as students’ wellbeing, school belonging and so forth. Allen et al. (2018), in their meta-analysis consisting of 51 studies, found evidence that individual factors such as teacher support (e.g., in learning processes), student characteristic (e.g., emotional stability and self-esteem), and micro-level factors such as peer and parent support strongly correlated with school belonging. School belonging, in turn, has an impact on psychological wellbeing (Jose et al., 2012).

Several studies have indicated that the relationships to teachers as well as classmates correlate strongly with the wellbeing domains (e.g., Moore et al., 2017). The importance of the student-teacher relationship for wellbeing was also confirmed by Littlecott et al. (2018) who conducted interviews with the teaching and support staff as well as with students and parents. In a mixed-method survey, Anderson and Graham (2016) showed that students reported that being respected, being listened to as well as having a say were linked to school wellbeing.

Peers’ Role

In a systematic review Woodgate et al. (2020) state that peers named the presence of teacher assistants who spend time with students with SEN as well as dependence on parents (e.g., the necessity to accompany to e.g., leisure activities) as a barrier of inclusion. Furthermore, physical disabilities and emotional challenges of students with SEN were named as hindering factors for them to include their peers. However, also the peers’ lack of knowledge in alternative communication skills and their friends influence toward students with SEN were discussed as additional barriers in building relationships with students with SEN. Following this, also the attitude of peers has to be named as an important factor. Several studies have shown its significant impact on the social inclusion of students with SEN (Vignes et al., 2009; De Boer and Pijl, 2016; Schwab, 2017). Therefore, it is important to consider this aspect of peer relationships in inclusive classrooms, as negative attitudes displayed toward students with SEN can lead to poor social inclusion of the latter (Nowicki and Sandieson, 2002; Bossaert et al., 2011). Hellmich and Loeper (2019) also found empirical evidence that apart from contact, students’ self-efficacy beliefs also predicted their attitudes. Positive attitudes can be fostered by actions such as promoting high-quality contact among students with and without SEN by engaging students in cooperative group activities (Keith et al., 2015; Schwab, 2017). This need was further highlighted in a systematic review by Garrote et al. (2017) who found empirical evidence that besides peer tutoring, interventions aiming to foster social interaction and cooperative learning, promote the social acceptance of students with SEN. Rademaker et al. (2020) further point out that in addition to contact, information on the topic of SEN is crucial to change students’ attitudes.

Parents’ Role

The role of parents, both those having children with or without SEN, regarding inclusive education and social inclusion must also be given attention. Past research showed that parents of students with SEN expressed ambivalent attitudes regarding inclusive education. Although they highlighted the advantages of inclusive education risks (e.g., students with SEN being excluded) were also articulated (De Boer et al., 2010; Gasteiger-Klicpera et al., 2013; Mann et al., 2016). Results of studies regarding the attitudes of parents of students without SEN were mixed. De Boer et al. (2010) conduced a review and showed that overall parents’ attitudes were positive regarding the inclusion of students with SEN. Contrary, Schmidt et al. (2020) found in their study that parents of children with SEN were more inclined to inclusion and supposed more positive social effects and advantages for all students than parents of children without SEN. Albuquerque et al. (2019) showed that the latter parents indicated neutral attitudes toward inclusion. Beside these findings, also, the type of disability seems to play a role when it comes to inclusion. Studies have found that parents are more open to the inclusion of students with physical or learning disabilities than to the inclusion of those students with behavioral disorders and intellectual disabilities (see e.g., Paseka (2017), Waxmann Paseka and Schwab (2020)). These results are important since Hellmich et al. (2019) also showed that perceived parental behavior toward students with SEN also predicted peers’ attitudes. Therefore the importance of parents’ attitudes and behavior in the context of social inclusion has to be given attention.

Teachers’ Role

In addition to peers and parents, teachers also play a crucial role in the social participation of students with SEN. In this sense, the role of classroom management also needs to be taken into consideration when aiming to include all students (Vollet et al., 2017). Farmer et al. (2019) point out that teachers need awareness and knowledge regarding classroom dynamics in order to create a classroom climate where all students help and cooperate with each other. Moreover, teacher-student relationships have been shown to impact peer relationships and students’ feelings of belonging (Hendrickx et al., 2016; Henke et al., 2017; Van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). Past research also found evidence that teachers’ attitudes toward students with SEN and inclusive teaching practices also play an important role (Avramidis et al., 2019). Subsequently, teachers holding more positive attitudes are open to implement inclusive teaching practices (Hellmich et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2019) and modify their teaching practices to ensure the inclusion of all learners (Monsen et al., 2014). Another outcome of past research is the role of feedback in social acceptance. For instance, it could be shown that positive and negative teacher feedback on both, behavior and academic performance, had an impact on peer acceptance (Bacete et al., 2017; Hendrickx et al., 2017; Wullschleger et al., 2020; Schwab et al., 2022). Teachers themselves emphasize the importance of early integration of students with SEN into kindergarten and preschool in order to foster contact and highlight that cooperation between parents and social workers is crucial. Concerning teachers, Schwab et al. (2019) state that pointing out not only similarities but also the uniqueness of students is crucial to avoid stigmatization and support participation.

Study

Given the assumption that inclusive educational processes are multifaceted and influenced by various stakeholders involved, the present study aims to highlight different perspectives related to students’ inclusion in school. The main research question is as follows:

What promotes the inclusion of students with SEN into educational situations from teachers’, students’, and parents’ perspectives who have an active relationship with inclusive educational settings (teaching in inclusive classes, attending inclusive classes, or being a parent of a student that attends an inclusive class)?

Materials and Methods

Sample and Procedure

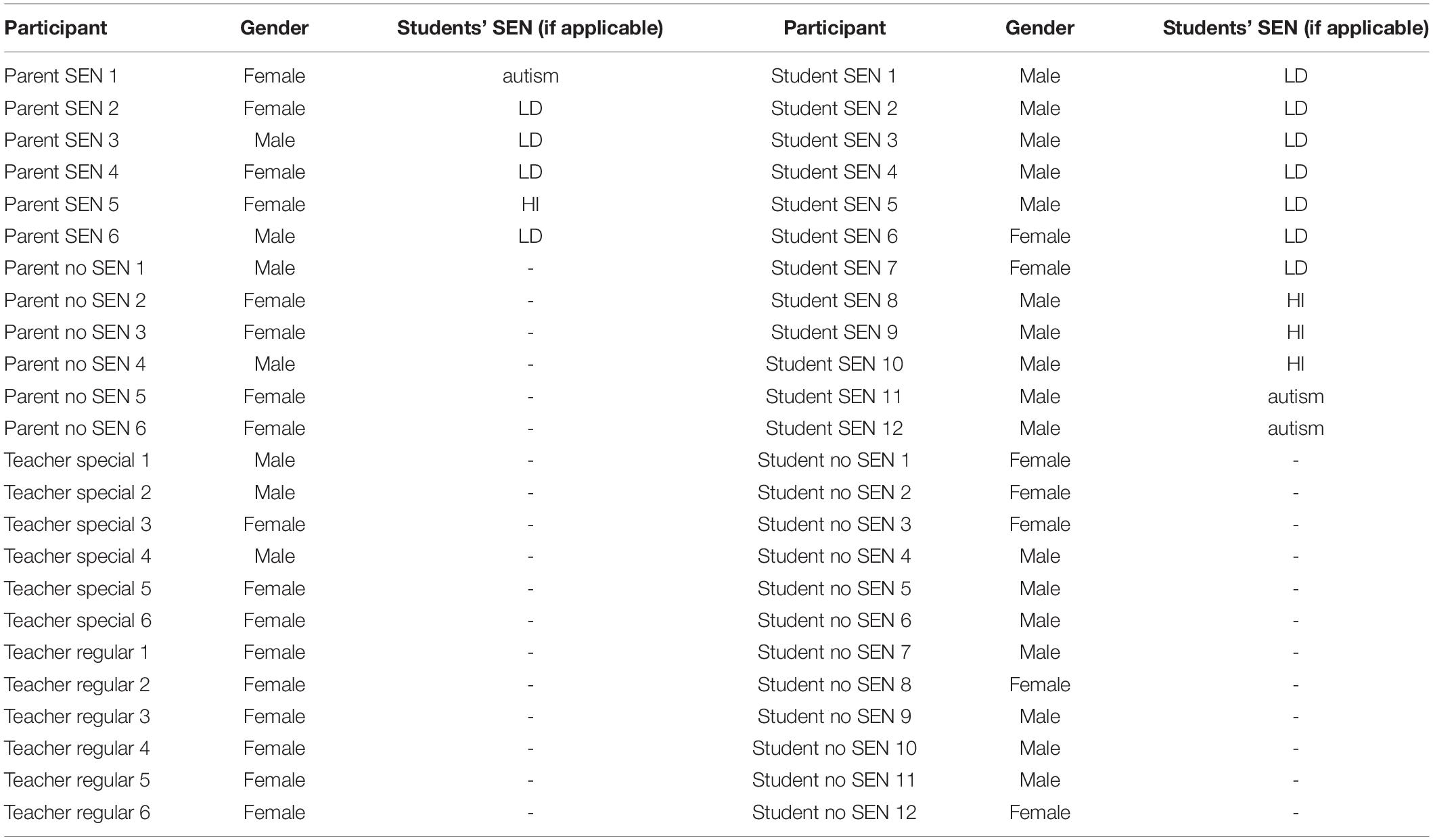

We conducted semi-structured face-to-face interviews with students, teachers, and parents of students in inclusive classes. The inclusion criteria for the sample were that there had to be at least two students with an official diagnosis of having SEN in class and the existing cooperation of a regular as well as a special needs teacher. Overall, six parents (mother or father) of students with SEN, six parents (mother or father) of students without special educational needs, six regular teachers, six special needs teachers, twelve students with SEN, and twelve students without SEN took part in the study. Out of the twelve students with SEN, seven students had learning disabilities (LD), three had hearing impairments (HI), and two students were diagnosed with autism (see Table 1).

The recruitment took place within a broader research project, ATIS STEP project (e.g., Schwab, 2018b). This project was supported by the Styrian Government [grant number: ABT08-247083/2015-34]. Ethical approval was given by the local school authority of Styria (Landesschulrat Steiermark). The interviewees have been chosen from six schools in Styria (a federal state of Austria). To guarantee consent from the school board members and participants, the following procedure was performed: First, school leaders were asked for permission to choose six inclusive classes of the 4th grade from the respective schools. Subsequently, both teachers (regular and special needs teachers) of all of the six classes took part in the interviews. Second, two students with SEN as well as two students without SEN had been selected (by the research team and the teachers) to be interviewed. Additionally, for all students, one caretaker was asked to participate in the interview study. The interviews lasted for 15–90 min and had been conducted at school or other places convenient for the interviewees.

Material

Semi-structured interviews were conducted following a guideline-based approach. Interviewees were asked about their perception of conditions required for the successful inclusion of students. In addition to that, the participants were asked about educational aspects that might promote or hinder successful inclusive learning situations for students with SEN. Another focus was given to the participants’ perceptions of possible opportunities for inclusive action and intervention with a particular focus on inclusion in their area of responsibility as well as considering other stakeholders involved (depending on the role students, teachers, parents). The interviews had been audio-recorded and transcribed in the course of which, personal data have been kept confidential.

Analytical Approach

Methodologically, the current study follows a multiple-case study approach, which provides the opportunity to shed light to different perspectives by carefully choosing cases that are predicted to contain similar as well as contrasting results depending on the participants role in inclusive education of students with SEN (Yin, 2013). For an analytical approach, the thematic analysis with regards to Froschauer and Lueger (2020) was chosen. In the course of this method of analysis, five steps were to be taken into account when investigating the data material: (1) identifying thematic clusters, (2) explicating the characteristics of the themes, (3) investigating differences and similarities regarding the extracted phrases within one theme, (4) elaborating a hierarchical relevance of topics if possible, and (5) integrating the themes in the context of the research question (Froschauer and Lueger, 2020). By combining the methodological approach of a multiple-case study and the analytical method of thematic analysis, the summarizing discussion can deal with the perspective related results within a cross-case synthesis after coding and analyzing each case individually.

Results

Given a multi-perspective approach by including the perceptions of teachers, students and parents, the results are displayed by highlighting the promoting and hindering factors including the respective samples in terms of self-perception and perception by the other sample groups. Therefore, the thematic clusters are firstly identified, and their general characteristics are explained and in the consequent steps. Following that, self-attributions, as well as external attributions of conducive and obstructive interventions considering students’ social participation, are presented.

Regarding the results of the analyzed multi-perspective data, the inclusion of students with SEN in school can be summarized on three levels: educational, interpersonal, and intrapersonal levels. Throughout all samples, the aspects considering every level were examined.

Inclusion and Its Educational Requirements

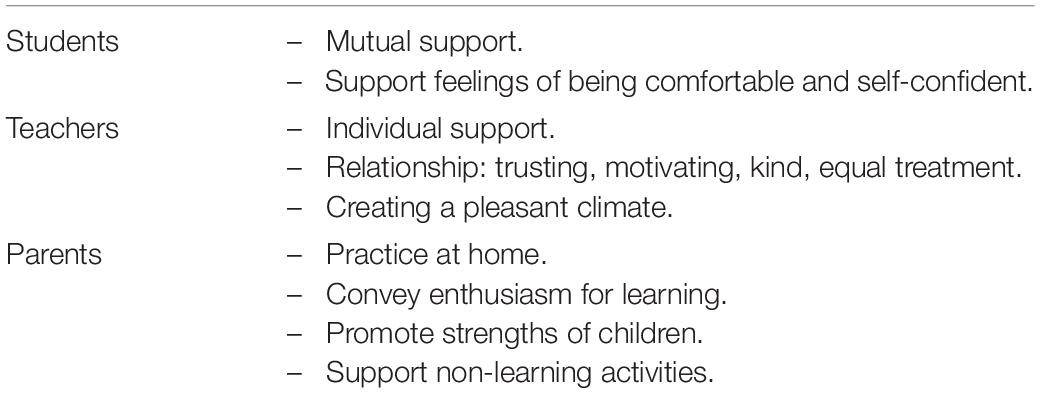

When it comes to beneficial conditions for the promotion of inclusion on the educational level, students with SEN themselves mention that everyone involved can play a supportive role in creating inclusive learning activities. Mutual support has been formulated as particularly important, which can be provided in the context of a supportive network of educational professionals and students (see Table 2).

Regular teachers mention that they should focus on adjusting the difficulty of the learning material according to every student’s educational needs. They also mention that special needs teachers should also be able to work alone with students when necessary. From a special needs teacher’s point of view, teachers should encourage and motivate students, build a trustful relationship between teachers and students, and avoid giving strong negative ratings of school performance that might discourage students from engaging with the teaching and learning processes. They should further create a pleasant class climate in which students feel free to participate. In doing so, the goal is to communicate that, regardless of having SEN or not having SEN, students feel accepted as equals in the class.

The sample of regular teachers and special needs teachers both highlight the important role of parents in creating inclusive educational situations. Regular teachers and special needs teachers believe that parents should support their children at home. They should help their child with the learning process at home, practice with them, and convey enthusiasm for learning activities. Teachers also wish that parents take over their consultation.

The parents’ perspective goes in line with that of teachers. They believe that teachers should support students with SEN individually and, in connection therewith, use an adequate speed of introduction when explaining new learning content. In addition, parents of students with SEN point out that teachers should not exclusively focus on the weaknesses of students, but rather focus on their (potential) strengths. They highlight the importance of teachers’ patience, kindness, and equal treatment toward diverse students. Parents of students with SEN also highlight that the competence of the special needs teacher is crucial to the successful educational development of their child. They should individually support students and give them precise feedback on what was good and what was not good regarding schoolwork. It is important to not put students under pressure and instead focus on building motivation and a good work attitude. Their peers who have and don’t have SEN should support a climate of comfort and self-confidence. In line with this, students with and without SEN mentioned that learning seems possible if they feel comfortable and self-confident.

Students without SEN highlight that parents should support their children with their learning activities. Interestingly, they mention that it is important to also promote non-performance-related activities, i.e., sports and social engagement. They argue that activities in between teaching and learning sessions, which are free from the pressure of performing, act as recovery phases that promote concentration and performance.

Inclusion and Its Intrapersonal Requirements

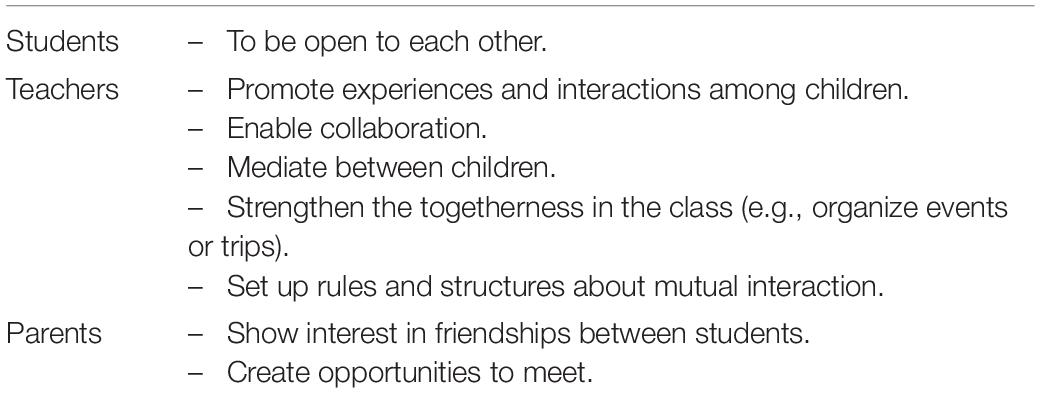

According to students, parents, and teachers, students’ positive wellbeing, on an intrapersonal level, is considered to be a criterion when it comes to the provision of inclusive schooling situations and processes (see Table 3).

When asking students with SEN about who they think can help them in building or strengthening their positive wellbeing in school they mention various actors, they mentioned friends and classmates as the most central persons, but also teachers, parents, and additional caretakers. In addition to social contact and interaction in school, spending free time together when invited to social events (i.e., birthday parties) of peers was also considered important. Students without SEN highlight that the togetherness within the class and friendships are significant when it comes to wellbeing. Students “shouldn’t be mean to each other, help each other, play with each other, do not insult each other, and stand up for each other when something bad happens” (An interview with a student without SEN).

Students also highlight the role of parents. They can support the wellbeing of special education needs students: “they for example, if there is a problem with another student go to the teachers and tell them and then the teachers do something.”

Parents of students with SEN mention that it is important to address problems and support children in learning to deal with conflicts. Thus, parents should discuss experiences with their children. They should also encourage their children to change their perspective in order to understand others involved in social situations. Therefore, it is necessary to be patient with the children. Teachers, on the other hand, should be willing to find solutions for problems and conflicts and promote mutual understanding between students. Teachers should be just in their behavior and treat children equally. They should also engage in creating a suitable environment for students, including creating a enjoyable classroom environment. In general, the culture or climate at school as well as a positive discussion culture is considered to be beneficial for students’ wellbeing.

Parents of students without SEN highlight that parents of students with SEN should assume an active role and participate in the education of the children and also work with teachers (and not against them) to support their children. In addition, parents of students without SEN should get their children to invite both students with and without special education needs and guide their children with mutual acceptance. However, from their point of view, teachers are responsible for creating structures and rules for learning together, which is important from the beginning of the school year on. In addition, teachers should convey the basic value that people’s ability to be diverse should be accepted and appreciated. In doing so they should accept children as they are and promote self-confidence. In the case of students’ behavior, parents think that mutual acceptance and their interaction within the class is decisive for the positive wellbeing of students with SEN.

Special needs teachers highlight that the attitudes of students are strongly based on the attitudes of their parents. Thus, parents should support the integration process and talk with their children regarding their peers with SEN, answer their questions, and discuss difficulties. Parents should also proactively invite students with SEN to their homes. In addition, good cooperation between parents and teachers is important to support the wellbeing of students with SEN.

Regular teachers highlight that all teachers should act as a team and work together. They should create an appropriate classroom setting, set up class rules, adhere to them, demand them, and make sure that all students feel welcome within this behavioral frame. In other words, they should create conditions that are suitable for all children. Teachers should also support interaction among students by promoting collaboration and mediating their interactions. Social learning will be enabled through such interactions. Further, teachers can increase the acceptance of students among each other and that they are aware and accept that there are differences. In particular, they should explain to all children that everyone has weaknesses and strengths, and that some students learn differently than others, which is acceptable. In addition, they should establish an understanding of the students’ disabilities. Teachers should invest efforts in strengthening the class community. Within their behavior to the individual students, teachers should be sensitive, take children as they are, consider all their needs, and act fair without favoring anyone or emphasizing the special feature of the student with SEN.

From the perspective of regular teachers, students with SEN should have a caregiver and friend to establish positive wellbeing. Therefore, students must play together to enable building friendships.

Inclusion and Its Interpersonal Requirements

Students with SEN often see themselves as responsible for having friends regarding the expectations of others toward them. However, when talking to parents and teachers the multi-causality is getting clearer (see Table 4).

The parents’ perspectives of students with and without SEN highlight the perception that they feel responsible to show interest in their children’s friendships and that they feel the need to support these interactions. They feel that they are expected to seek interactions with other parents. An upright interaction between parents is understood as a bridge for friendships among children. For instance, they can directly invite other children to their homes without getting their children involved in the process of rapprochement. Parents also highlight the importance of teachers regarding their children’s social inclusion as an important aspect of inclusion at school. Parents of students with SEN believe that teachers should support the collaboration among students and, if necessary, mediate between students with and without SEN. Both samples of parents indicate the importance for teachers to treat all students equally. Parents of students without SEN elaborate on this issue and suggest that teachers should initiate and enable experiences and interactions among students with and without SEN and support the class community by organizing events and trips with their students. Further, to enable conflict-free situations, teachers should establish rules and structures that define how students should interact with each other. In the event of conflicts, teachers should be able to guide students in dealing with these situations. The parents of students without SEN also point out that parents should strengthen their children’s self-esteem and teach them tolerance.

Regular teachers have similar opinions. They mention that they indirectly create the social foundation that allows interactions and friendships between students to develop. They enable interactions by implementing social grouping strategies or by changing the seating arrangement. Special needs teachers mention that games can also enable a feeling of togetherness. However, within these games, teachers should also be present and help when conflicting situations emerge. They should then address and discuss conflicts. In general, they point out that teachers must talk about the children in a positive way. Both teachers point out that parents are important when it comes to friendships. Parents should not work against inclusion. Instead, parents should create opportunities for children to privately meet after school and in general be open. They also point out that parents should pass on basic values and behaviors to their children that can be beneficial for building friendships. Regular teachers further highlight that parents should support their children in accepting others. This will further contribute to a good class climate. Teachers can also strengthen the class community. For instance, they can establish and enable contact among children. They should also support the interaction between students by providing them their help (e.g., during conflicts) and support interpersonal acceptance.

Summary of Results

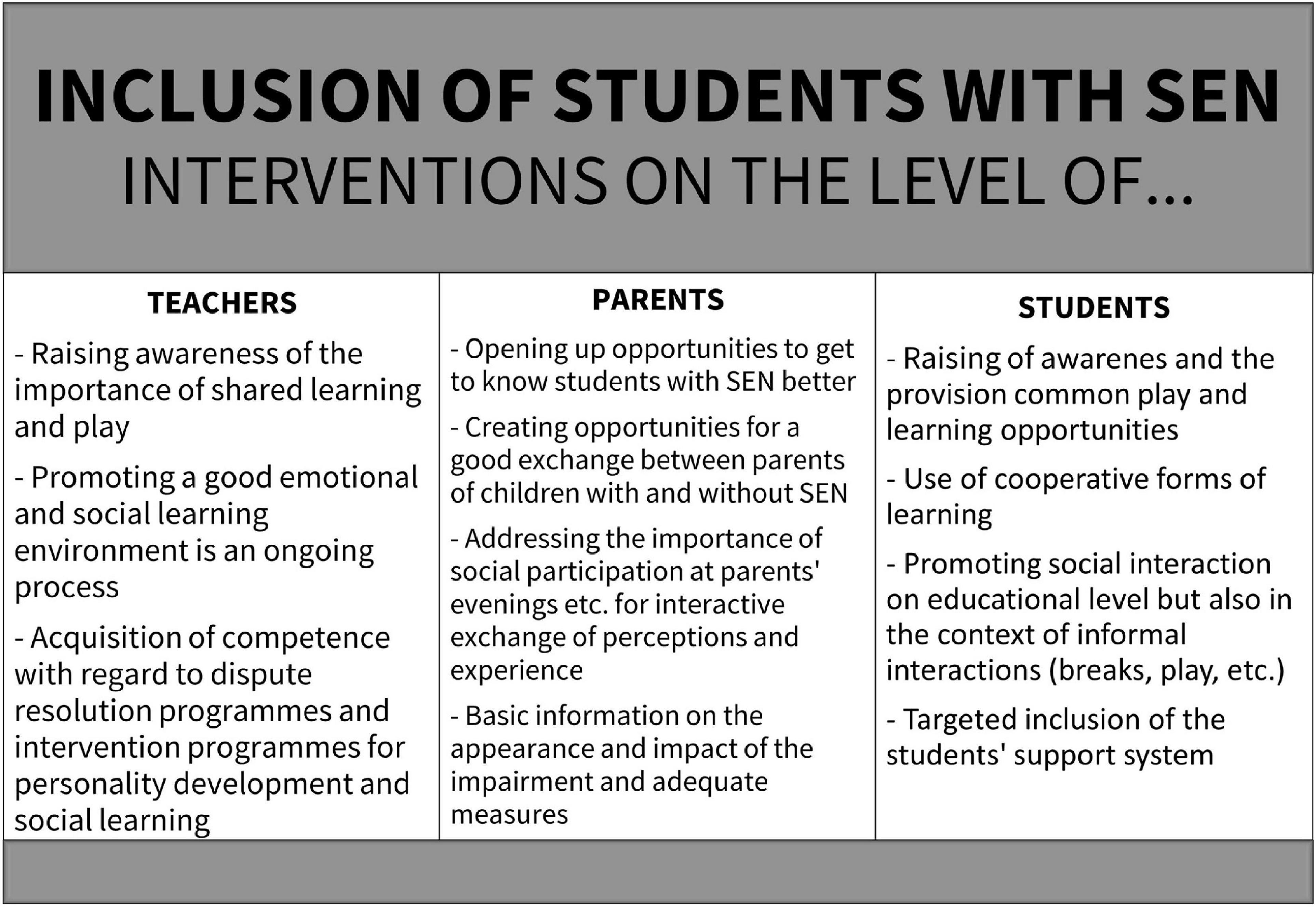

Figure 1 presents opportunities for intervention at different personal levels that can contribute to the design and promotion of an inclusive classroom climate.

Discussion

The present study describes aspects that can facilitate inclusive education for and inclusion of students with SEN. Regarding promoting factors, different perspectives of people who are somewhat involved in educational processes of students with SEN (i.e., teachers, parents, peers without SEN), as well as the perspective of students with diverse special needs (i.e., learning disabilities, hearing impairments, and autism), have been highlighted. The findings yield conditions that support inclusive educational opportunities on the following three levels of inclusion: educational, intrapersonal, and interpersonal levels. Tracing back the findings to these three levels of inclusion complements the literature presented earlier in the introduction, thereby emphasizing the need to allow interactions of students with and without SEN considering diverse pedagogical dimensions, for example, within social, educational, but also individual contexts (Felder, 2018; UNESCO, 2020).

The outcomes resulted in a collection of desired measures and behaviors from the perspective of different stakeholders involved in the education of students with SEN to support their inclusion. The results hold practical implications for teachers and parents, but also students with and without SEN when it comes to fostering the inclusion of students with special education needs.

Regarding students’ inclusion and consequent educational requirements that are needed, the prerequisites to promote adequate teaching and learning processes and to provide equal and adapted access to education for all students have been examined (Monsen et al., 2014; Vollet et al., 2017; Farmer et al., 2019; Hellmich et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2019). The requirements for fostering intrapersonal factors of inclusion encompass prerequisites of the feeling of belonging and wellbeing regarding school and classroom processes (Hendrickx et al., 2016; Henke et al., 2017; Van den Berg and Stoltz, 2018). On the interpersonal level, basic conditions for interactions and building friendships in order to promote inclusive education are highlighted in various studies (Bossaert et al., 2009; Koster et al., 2009; Little, 2017).

Interestingly, various explicit and implicit implications for desired behaviors of specific stakeholders were mentioned in the context of external perspectives. This signifies that the interviewees addressed the need for inclusive action not (only) in themselves, but, above all, in other groups of people involved. This primary finding goes in line with previous research and theory on inclusive education that highlights the importance of taking the whole educational network and people involved into account. Therefore, an inclusive school culture needs to be considered when fostering students’ inclusion.

When it comes to requirements for inclusion on an intrapersonal level, friends and classmates are considered to be the most central and important persons involved in developing a sense of belonging and wellbeing (Vignes et al., 2009; De Boer and Pijl, 2016; Schwab, 2017). Parents are deemed indirectly relevant, as attitudes of students are strongly based on the attitudes of their parents (Hellmich and Loeper, 2019). Interestingly, the factors that seem to be especially relevant for creating friendships are teachers that set the ground for friendships in the classroom (Keith et al., 2015; Garrote et al., 2017; Schwab, 2017), and parents that enable opportunities to meet other students.

For educational requirements of inclusion, the role of teachers appears to be important for all the interviewed samples. They are expected to promote individual learning opportunities and just treatment of all students (Janice et al., 2017; Watkins, 2017). The previously mentioned areas of responsibility, which the sample groups attribute to each other rather than to themselves, become particularly clear. Meanwhile, students and parents highlight the central role of teachers in the context of providing adequate educational opportunities. In light of inclusion, teachers also assign increased responsibility to another group of stakeholders involved, namely, the parents. According to the interviewed teachers, parents take over an important role regarding the educational dimension of their children’s inclusion by practicing with them at home. In this context, a specific question arises: Why are parents expected to do the pre-work or follow-up work on teachers’ pedagogical decisions regarding the didactic measures in class? A possible explanation for this is that they know that their children with SEN would not be capable of keeping up with the teachers’ instructions otherwise. In line with this assumption, inadequate teaching that is not adapted to the needs of individual students could create the need for at-home support by external stakeholders, namely, their parents/caregivers. Furthermore, the extent of measures promoting inclusion that can be supported by all parents or different possibilities and degrees of supporting children in learning due to individual family characteristics and situations should be discussed.

Regarding this issue, the data highlights additional factors that predict whether inclusion is successful for creating a stimulating and promoting learning environment for every student regardless of an SEN diagnosis: resources (time and staff–and their skills and competencies) and the quality of teamwork between students, teacher (special needs teachers and regular teachers) and parents (Moore et al., 2017; Allen et al., 2018; Littlecott et al., 2018; Goldan et al., 2021).

Conclusion

While policies for inclusive education ensure the spatial inclusion of students with and without SEN within the same classes, efforts have to be made to ensure real inclusion. Within the current study, it became evident that a sustainable inclusive development needs support of preventive actions and interventions at the level of all involved stakeholders. Teachers need to ensure high quality learning conditions (e.g., creating a fruitful emotional and social learning environment). Moreover, parents can create opportunities for exchange (e.g., of students with and without SEN and parents of children with and without SEN). However, peers play a significant role in promoting successful inclusion, for example, through formal interactions such as cooperative learning processes or informal interactions (e.g., playing together). The study indicated clear evidence that current practices need to be improved in order to overcome inequality and exclusion and to become more inclusive for students with SEN.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by local school authority of Styria (Landesschulrat Steiermark). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

K-TL contributed to conception and design of the study, analyzed data, revised the first draft, wrote the second draft of the manuscript, wrote sections of the manuscript, and participated in theoretical framework. SH wrote sections of the manuscript and participated in theoretical framework. SS contributed to conception and design of the study and wrote sections of the manuscript. CG contributed to conception and design of the study, analyzed data, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and wrote sections of the manuscript. SK-S and AH contributed to conception and design of the study, analyzed data, and wrote sections of the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

CG was employed by company AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Albuquerque, C. P., Pinto, I. G., and Ferrari, L. (2019). Attitudes of parents of typically developing children towards school inclusion: the role of personality variables and positive descriptions. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 34, 369–382. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2018.1520496

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., and Waters, L. (2018). What schools need to know about fostering school belonging: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30, 1–34. doi: 10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Anderson, D. L., and Graham, A. P. (2016). Improving student wellbeing: having a say at school. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 27, 348–366. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2015.1084336

Avramidis, E., Toulia, A., Tsihouridis, C., and Stroglios, V. (2019). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion and their self-efficacy for inclusive practices as predictors of willingness to implement peer tutoring. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 19, 49–59. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12477

Bacete, F. J. G., Planes, V. E. C., Perrin, G. M., and Ochoa, G. M. (2017). Understanding rejection between first-and-second-grade elementary students through reasons expressed by rejecters. Front. Psychol. 8:462. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00462

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2011). The attitudes of belgian adolescents towards peers with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 32, 504–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.033

Bossaert, G., Colpin, H., Pijl, S. J., and Petry, K. (2013). Truly included? A literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 60–79. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2011.580464

Bossaert, G., Kuppens, S., Buntinx, W., and Molleman, C. (2009). Usefulness of the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS) for persons with other than intellectual disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 30, 1306–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2009.05.007

De Boer, A., and Pijl, S. J. (2016). The acceptance and rejection of peers with ADHD and ASD in general secondary education. J. Educ. Res. 109, 325–332. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2014.958812

De Boer, A., Pijl, S. P., and Minnaert, A. (2010). Attitudes of parents towards inclusive education: a review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 25, 165–181. doi: 10.1080/08856251003658694

Erten, O., and Savage, R. S. (2012). Moving forward in inclusive education research. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 16, 221–233. doi: 10.1080/13603111003777496

Farmer, T. W., Hamm, J. V., Dawes, M., Barko-Alva, K., and Cross, J. R. (2019). Promoting inclusive communities in diverse classrooms: teacher attunement and social dynamics management. Educ. Psychol. 54, 286–305. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1635020

Felder, F. (2018). The value of inclusion. J. Philos. Educ. 52, 54–70. doi: 10.1111/jope.2018.52.issue-1

Froschauer, U., and Lueger, M. (2020). Das Qualitative Interview: Zur Praxis interpretativer Analyse sozialer Systeme [The qualitative interview: On the Practice of Interpretive Analysis of Social Systems]. Munich: Utb GmbH.

Garrote, A., Dessemontet, R. S., and Opitz, E. M. (2017). Facilitating the social participation of pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools: a review of school-based interventions. Educ. Res. Rev. 20, 12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.11.001

Gasteiger-Klicpera, B., Klicpera, C., Gebhardt, M., and Schwab, S. (2013). Attitudes and experiences of parents regarding inclusive and special school education for children with learning and intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 17, 663–681. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.706321

Gökmen, A. (2021). School belongingness, well-being, and mental health among adolescents: exploring the role of loneliness. Aust. J. Psychol. 73, 70–80. doi: 10.1080/00049530.2021.1904499

Goldan, J., Hoffmann, L., and Schwab, S. (2021). “A matter of resources? – students’ academic self-concept, social inclusion and school well-being in inclusive education,” in Resourcing Inclusive Education (International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, Vol. 15, eds J. Goldan, J. Lambrecht, and T. Loreman (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 89–100. doi: 10.1108/S1479-363620210000015008

Hascher, T. (2017). “Die Bedeutung von Wohlbefinden und Sozialklima für Inklusion [The impact of wellbeing and social climate for inclusion],” in Inklusion: Profile Für Die Schul- Und Unterrichtsentwicklung in Deutschland, Österreich Und Der Schweiz, eds B. Lütje-Klose, S. Miller, S. Schwab, and B. Streese (Münster, NY: Waxmann), 69–79.

Hassani, S., Aroni, K., Toulia, A., Alves, S., Görel, G., Löper, M. F., et al. (2020). School-Based Interventions To Support Student Participation. A Comparison Of Different Programs. Results from the FRIEND-SHIP Project. Vienna: University of Vienna. doi: 10.25365/phaidra.147

Hellmich, F., and Loeper, M. F. (2019). Children’s attitudes towards peers with learning disabilities – the role of perceived parental behaviour, contact experiences and self-efficacy beliefs. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 46, 157–179. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12259

Hellmich, F., Löper, M. F., and Görel, G. (2019). The role of primary school teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs for everyday practices in inclusive classrooms – a study on the verification of the ‘theory of planned behaviour’. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 19, 36–48. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12476

Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Mainhard, M. T., Boor-Klip, H. J., Cillessen, A. H. M., and Brekelmans, M. (2016). Social dynamics in the classroom: teacher support and conflict in the peer ecology. Teach. Teach. Educ. 53, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.004

Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Boor-Klip, H. J., and Brekelmans, M. (2017). Teacher behavior and peer liking and disliking: the teacher as a social referent for peer status. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 546–558. doi: 10.1037/edu0000157

Henke, T., Bogda, K., Lambrecht, J., Bosse, S., Koch, H., Maaz, K., et al. (2017). Will you be my friend? A multilevel network analysis of friendships of students with and without special educational needs backgrounds in inclusive classrooms. Z. Erziehungswiss. 20, 449–474. doi: 10.1007/s11618-017-0767-x

Janice, K., Lee, J. K., Joseph, J., Strain, P., and Dunlap, G. (2017). “Social inclusion in the early years,” in Supporting Social Inclusion For Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder, ed. C. Little (London: Routledge), 57–70. doi: 10.4324/9781315641348

Jose, P. E., Ryan, N., and Pryor, J. (2012). Does social connectedness promote a greater sense of well-being in adolescence over time? J. Res. Adolesc. 22, 235–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00783.x

Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., and Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting social inclusion in educational settings: challenges and opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 54, 250–270. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645

Keith, J. M., Bennetto, L., and Rogge, R. D. (2015). The relationship between contact and attitudes: reducing prejudice toward individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 47, 14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2015.07.032

Koster, M., Nakken, H., Pijl, S. J., and van Houten, E. (2009). Being part of the peer group: a literature study focusing on the social dimension of inclusion in education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 13, 117–140. doi: 10.1080/13603110701284680

Little, C. (2017). “Social inclusion and autism spectrum disorder,” in Supporting Social Inclusion For Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder, ed. C. Little (London: Routledge), 9–20.

Littlecott, H. J., Moore, G. F., and Murphy, S. M. (2018). Student health and well-being in secondary schools: the role of school support staff alongside teaching staff. Pastor. Care Educ. 36, 297–312. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2018.1528624Majda

Mann, G., Cuskelly, M., and Moni, K. (2016). Parents’ views of an optimal school life: using social role valorization to explore differences in parental perspectives when children have intellectual disability. Int. J. Q. Stud. Educ. 29, 964–979. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2016.1174893

McCoy, S., and Banks, J. (2017). Simply academic? Why children with special educational needs don’t like school. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 27, 81–97. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.640487

Monsen, J. J., Ewing, D. L., and Kwoka, M. (2014). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, perceived adequacy of support and classroom learning environment. Learn. Environ. Res. 17, 113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10984-013-9144-8

Moore, G. F., Littlecott, H. J., Evans, R., Murphy, S., Hewitt, G., and Fletcher, A. (2017). School composition, school culture and socioeconomic inequalities in young people’s health: multi-level analysis of the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) survey in Wales. Br. Educ. Res. J. 43, 310–329. doi: 10.1002/berj.3265

Nilholm, C., and Göransson, K. (2017). What is meant by inclusion? an analysis of european and north american journal articles with high impact. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 32, 437–451. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2017.1295638

Nowicki, E. A., and Sandieson, R. (2002). A meta-analysis of school-age children’s attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 49, 243–265. doi: 10.1080/1034912022000007270

Paseka, A. (2017). “Stand der Inklusion Aus Elternsicht [inclusion from a Parents‘ Perspective],” in Eltern Beurteilen Schule – Entwicklungen und Herausforderungen. Ein Trendbericht Zu Schule und Bildungspolitik in Deutschland. 4. JAKO-O Bildungsstudie, eds D. Killus and K.-J. Tillmann 99–122. Waldkirchen: Waxmann Verlag.

Rademaker, F., de Boer, A., Kupers, E., and Minnaert, A. (2020). Applying the contact theory in inclusive education: a systematic review on the impact of contact and information on the social participation of students with disabilities. Front. Educ. 5:602414. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.602414

Schmidt, M., Krivec, K., and Bastiè, M. (2020). Attitudes of Slovenian parents towards pre-school inclusion. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 696–710. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1748430

Schwab, S. (2017). The impact of contact on students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 62, 160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.01.015

Schwab, S. (2018b). “Peer-relations of students with special educational needs in inclusive education,” in Diritti Cittadinanza Inclusione, eds S. Polenghi, M. Fiorucci, and L. Agostinetto (Rovato: Pensa MultiMedia), 15–24. doi: 10.1111/bjep.12262

Schwab, S. (2018a). Attitudes Towards Inclusive Schooling. A Study On Students’, Teachers’ And Parents’ Attitudes. Münster: Waxmann Verlag.

Schwab, S., Markus, S., and Hassani, S. (2022). Teachers’ feedback in the context of students’ social acceptance, students’ well-being in school and students’ emotions. Educ. Stud. 2022, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2021.2023475

Schwab, S., Wimberger, T., and Mamas, C. (2019). Fostering social participation in inclusive classrooms of students who are deaf. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 66, 325–342. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2018.1562158

Skrzypiec, G., Askell-Williams, H., Slee, P., and Rudzinski, A. (2016). Students with self-identified special educational needs and disabilities (si-SEND): flourishing or languishing! Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 63, 7–26. doi: 10.1080/1034912x.2015.1111301

UN (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. New York, NY: Department of Economic and Social Affairs Disability

UNESCO (1994). The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Salamanca: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2020). Towards Inclusion In Education: Status, Trends And Challenges. The UNESCO Salamanca Statement 25 years on. Paris: UNESCO.

Van den Berg, Y. H. M., and Stoltz, S. (2018). Enhancing social inclusion of children with externalizing problems through classroom seating arrangements: a randomized control trial. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 26, 31–41. doi: 10.1177/1063426617740561

Vignes, C., Godeau, E., Sentenac, M., Coley, N., Navarro, F., Grandjean, H., et al. (2009). Determinants of students’. attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 51, 473–479. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.2009.51.issue-6

Vollet, J. W., Kindermann, T. A., and Skinner, E. A. (2017). In peer matters, teachers matter: peer group influences on students’ engagement depend on teacher involvement. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 635–652. doi: 10.1037/edu0000172

Watkins, A. (2017). Inclusive Education And European Educational Policy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.153

Waxmann Paseka, A., and Schwab, S. (2020). Parents’ attitudes towards inclusive education and their perceptions of inclusive teaching practices and resources. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 35, 254–272. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2019.1665232

Wilson, C., Marks Woolfson, L., and Durkin, K. (2019). The impact of explicit and implicit teacher beliefs on reports of inclusive teaching practices in Scotland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 378–396. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1658813

Woodgate, R. L., Gonzalez, M., Demczuk, L., Snow, W. M., Barriage, S., and Kirk, S. (2020). How do peers promote social inclusion of children with disabilities? A mixed-methods systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 42, 2553–2579. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2018.1561955

Wullschleger, A., Garrote, A., Schnepel, S., Jaquiéry, L., and Moser Opitz, E. (2020). Effects of teacher feedback behavior on social acceptance in inclusive elementary classrooms: exploring social referencing processes in a natural setting. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 60:10184. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101841

Keywords: inclusive education, social inclusion, special educational needs, promoting factors, multiperspective approach

Citation: Lindner K-T, Hassani S, Schwab S, Gerdenitsch C, Kopp-Sixt S and Holzinger A (2022) Promoting Factors of Social Inclusion of Students With Special Educational Needs: Perspectives of Parents, Teachers, and Students. Front. Educ. 7:773230. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.773230

Received: 09 September 2021; Accepted: 21 March 2022;

Published: 27 April 2022.

Edited by:

Francesco Arcidiacono, Haute École Pédagogique BEJUNE, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Ruth-Nayibe Cárdenas-Soler, Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, ColombiaSourav Mukhopadhyay, University of Botswana, Botswana

Copyright © 2022 Lindner, Hassani, Schwab, Gerdenitsch, Kopp-Sixt and Holzinger. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sepideh Hassani, c2VwaWRlaC5oYXNzYW5pQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Katharina-Theresa Lindner

Katharina-Theresa Lindner Sepideh Hassani

Sepideh Hassani Susanne Schwab

Susanne Schwab Cornelia Gerdenitsch4

Cornelia Gerdenitsch4 Silvia Kopp-Sixt

Silvia Kopp-Sixt Andrea Holzinger

Andrea Holzinger