- 1Department of Early Childhood, Youth, and Family Studies, Teachers College, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, United States

- 2College of Education, Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids, MI, United States

- 3Werklund School of Education, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 4College of Education, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, United States

This paper presents findings from a 2-year collaborative self-study examining four teacher educators’ (TEs’) experiences facilitating community-based field experiences in the United States and Canada. To examine our experiences working in these field settings we drew experiential learning theory (ELT) as well as the concept of apprenticeship of observation. Facilitating preservice teachers’ (PSTs) learning in field settings outside traditional PK-12 contexts, such as museums and a construction site, prompted us to consider how apprenticeships of observation and ELT intersect when seeking to expand PST education to also include community-based field settings. Working in these community-based field settings also served to disrupt some of our own apprenticeships of observation. Finally, we noted that when working in these non-traditional field settings and utilizing the ELT framework, our experiences as TEs were neither sequential nor unidirectional.

Introduction

In an earlier study, we focused on preservice teachers’ (PSTs) experiences working and learning in community-based field experiences (Hamilton et al., 2019). Through that study we sought to understand how these “less traditional” field experiences served to support PSTs’ learning. Part of this work focused on identifying and understanding how these community-based field experiences potentially disrupted PSTs’ “apprenticeships of observation” (Lortie, 1975). For most beginning and experienced educators, their apprenticeships of observation are informed by their prior PK-12 teaching and learning experiences, more so than what they learned in their teacher education programs.

Connected to our initial study, we also noted evidence regarding how our own apprenticeships of observation were challenged (Hamilton et al., 2019), but we did not focus on this finding. However, as teacher educators (TEs), the idea that facilitating and working in a community-based field experience might also serve to disrupt some of our own apprenticeships of observation intrigued us. To study this further, we returned to our data. We also collected additional data to identify and better understand how, if at all, our own apprenticeships of observation were challenged when facilitating community-based field experiences. In contrast to much of the literature connected to Lortie’s (1975) concept of apprenticeship of observation, which often centers on K-12 teachers, this study centers on TEs’ apprenticeships of observation. We believe this focus to be especially valuable as it is our job to prepare future teachers. If our own apprenticeships of observation are never challenged or disrupted, we are less likely to challenge PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation.

Drawing on Lortie’s (1975) work related to apprenticeships of observation and Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning theory (ELT) to frame our analysis, this self-study presents findings connected to how facilitating community-based field experiences served to disrupt some of our own apprenticeships of observation. Thus, the following research question guided this study.

As teacher educators,

1. How, if at all, does working in community-based settings serve to disrupt our apprenticeships of observation?

We begin with a theoretical framework and examination of relevant literature. We then present results, followed by a discussion, implications, and limitations. We conclude with how this study can serve to inform other TEs’ work.

Theoretical Framework

Traditional school settings are those experienced by many throughout their educational journey, that of the brick-and-mortar PK-12 school in which students and curriculum are organized and instructed by grade. These traditional settings are often hallmarked by educational experiences in which a teacher transmits knowledge and students receive that knowledge (Morrison, 2014). And although experiential, student-centered learning can occur in these brick-and-mortar settings, purposeful, disrupted learning is most often gained through experience (Dewey, 1938), particularly experiences beyond the four walls of a traditional classroom. Thus, if TEs are to expand their understanding of teaching and learning beyond brick-and-mortar PK-12 school settings, which informs their “apprenticeships of observation” (Lortie, 1975), they must have experiences in settings different from those they experienced as PK-12 students and teachers (Lortie, 1975; Brayko, 2013).

One such setting, which can serve to augment traditional PK-12 school field experiences are those that are community-based. Community-based field settings exist in many locales, including community-based arts organization, museums, and recreational sites (Hamilton et al., 2019). Such settings can serve to challenge, interrupt, and often expand formalized notions of teaching and learning (Hallman, 2012). Together with teacher education and in-school PK-12 field experiences, community-based settings can serve as an important part of expanding new and experienced educators’ understandings of when and where teaching and learning take place (Hamilton et al., 2019).

Apprenticeship of Observation

Lortie (1975) notes that, “American young people, in fact, see teachers at work much more than they see any other occupational group” (p. 61). As a result, PSTs and TEs often emulate pedagogies and practices they experienced and observed during their PK-12 schooling experiences. This emulation, however, is not without consequences. For Lortie, the apprenticeship of observation was akin to viewing a play. As future educators spend their PK-12 and postsecondary years as students in school, they “see the teacher from a specific vantage point,” thereby allowing them to see “the teacher frontstage and center like an audience viewing a play” (p. 62). Lortie also noted that this “play” was similar across schooling contexts; his claims align with the idea that PK-12 education is, relatively speaking, somewhat the same regardless of the geographical location and/or school setting. In other words, students’ apprenticeships of observation often end up being similar because systems of education are often similar and generally reflect a transmission model of teaching and learning (i.e., teacher instructs and students learn).

Thus, most PSTs and, by default many TEs, come to teacher education with similar and widely shared and deeply held notions of schooling, including models of instruction, based on limited and partial understandings (Hamilton and Van Duinen, 2018; Hamilton et al., 2019; Gray, 2020). Moreover, Lortie’s (1975) study – although conducted decades ago – still rings true today, as most models of PK-12 education remain similar to those in which Lortie’s study took place. These apprenticeships of observation are the result of observations and experiences PSTs had as PK-12 students and, for many TEs, as PK-12 teachers. Although not all observed pedagogies and practices are problematic, unless TEs and PSTs identify and understand their own deeply held beliefs, often based on their own experiences, they will not be able to determine what they should continue to enact and what should change.

Furthermore, Bullock (2009) notes that, “to teach teachers is a complicated process that requires a TE to confront and re-examine his or her prior assumptions about teaching and learning while constructing a pedagogy of teacher education” (p. 292). In community-based contexts (e.g., museums, parks, cultural centers, etc.) PSTs and TEs have opportunities to be apprenticed into new and expanded, perhaps even less-traditional, ways of thinking about teaching and learning (Hamilton et al., 2019). Similarly, in these community-based settings, TEs have opportunities to engage in purposeful, sustained inquiry into one’s own experiences and practices (Bullock, 2009). Such work can result in new knowledge and deeper understandings, including awareness of one’s own apprenticeship(s) of observation. While both traditional PK-12 school settings and community-based settings provide opportunities to engage in learning, community-based setting also presents opportunities to re-examine one’s own notions of what teaching looks like and to consider the multiple variations of when, how, and where teaching and learning occur.

Much of the literature associated with Lortie’s (1975) apprenticeship of observation is associated with PSTs and teacher preparation. For example, to make known and, when necessary, challenge PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation, some TEs have used modeling and “overcorrection” to draw attention to PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation, doing so to expressly draw attention to specific pedagogies and practices PSTs emulated and used (Grossman, 1991). Additionally, reflection and critique has also been embedded into PST education to challenge apprenticeships of observation. For example, Boyd et al. (2013), utilized blogs to invite PSTs to consider multiple perspectives and outcomes related to teaching and learning and Hamilton and Van Duinen (2018) employed “purposeful reflections” to scaffold PSTs’ secondary field placement experiences. These reflections challenged PSTs to name their observations and also consider, and reconsider, what they noticed and why, with the express expectation that in doing so, they would intentionally assume different perspectives throughout the semester. Additionally, Knapp (2012) employed reflective journals to elicit as well as challenge PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation and Furlong (2013) utilized PSTs’ life histories to help PSTs articulate their ideas and beliefs so that they could consider and reconsider them. Westrick and Morris (2016) also found that when explicitly attended to, it is possible for TEs to address PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation and, to varying degrees, purposefully disrupt and shift them.

Concurrently, it stands to reason that Lortie’s (1975) concept applies to TEs, who also had primary and secondary school experiences. Some TEs, despite being trained in teacher education programs, can – like PSTs – revert to pedagogies and practices aligned with their own apprenticeships of observation, either from their own PK-12 teaching experiences or as former inservice teachers themselves. Unless TEs – through advanced training or experiences – have actively challenged their own apprenticeships of observation, they may also actively support particular types of teaching and the schooling models they experienced as students or as former K-12 teachers. Although they may not all teach as they were taught, it is not often enough that TEs are explicitly invited to confront and examine their own apprenticeships of observation.

That said, there are many TEs who do this informally and on their own, seeking to develop and hone their pedagogy and practice. For example, Bullock (2009) utilized a self-study of the first 3 years of his work as a TE to understand how his own apprenticeships contributed to his work as a TE. Building on this initial work, Bullock (2011) challenged TEs to identify and name how particular apprenticeships of observation serve to advance or limit certain pedagogies and practices. In response to Bullock’s (2009, 2011) work, as TEs ourselves, we sought to understand how working in community-based field settings might present additional opportunities to become aware of our own apprenticeships of observation, including how these settings and experiences may influence the ways we conceive of education and how we prepare PSTs.

Experiential Learning Theory

Noted previously, experiential learning is an important component of teaching and learning (Dewey, 1938). Learning occurs as the result of a given experience, whether in or outside a PK-12 classroom setting. Moreover, experiential learning can and does happen in both PK-12 educational settings as well as settings schools and classrooms. Connected to this idea, Kolb’s (1984) ELT claims that humans gain new understanding through experience and, although not developed for the field of education specifically, ELT provides a model by which to examine our experiences as instructors working in community-based placement settings. This theory is particularly suited to the learning that occurs outside of traditional classrooms, such as that which happens in community-based settings where the interplay between the learner and the environment is a key element of experiential learning. It is this interplay that challenges learners to take risks and engage with an unfamiliar context, a necessary undertaking for “assimilating new experiences into existing concepts and accommodating existing concepts to new experiences” (Kolb and Kolb, 2005, p. 194). In this way, ELT presents a theoretical lens through which to examine how community-based field settings may serve as a catalyst for challenging apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975).

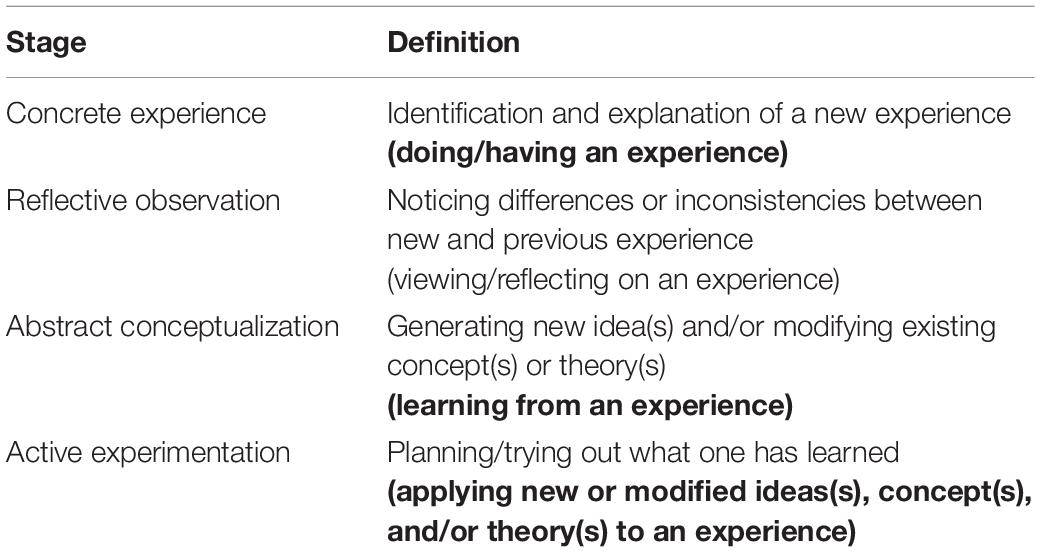

Experiential learning theory consists of four stages through which participants pass, though progression may not be sequential or unidirectional. Kolb (1984) describes these stages, noting that the first stage, the concrete experience, involves the identification of the new experience and is heavily dependent on the new context in which one finds oneself. This is followed by reflective observation whereby inconsistencies between the new and previous experiences result in questions and comparison. A third stage, abstract conceptualization then results in the development of new ideas or modification of long held beliefs. This is followed by active experimentation where one attempts to apply the new ideas to the learning context. Kolb and Kolb (2005) note that the ELT model offers two dialectically related modes of “grasping experience,” namely Concrete Experience (CE) and Abstract Conceptualization (AC). This model also presents two dialectically related modes of “transforming experience,” those being Reflective Observation (RO) and Active Experimentation (AE) (p. 194). To theorize the study of our own apprenticeships of observation, we drew on Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT, and to guide our analysis we clarified definitions for each stage (Table 1).

Table 1. Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT stages and authors’ definitions.

Experiences in community-based settings reflect Concrete Experiences which present learners, including TEs, with new situations and experiences from which to learn. Based on our experiences, community-based settings provide a “learning cycle or spiral where the learner ‘touches all the bases’ – experiencing, reflecting, thinking and acting – in a recursive process that is responsive to the learning situation and what is being learned” (Kolb and Kolb, 2005, p. 194). As a result, new ideas are formed within the context of a unique environment (i.e., a community-based setting), and the opportunity to challenge apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975) becomes possible.

Literature Review

Community-Based Field Settings

As part of teacher education programs, TEs must provide PSTs with various opportunities to engage and observe in PK-12 field experiences (Ball and Cohen, 1999; Forzani, 2014; Jenset et al., 2018). When TEs maintain a commitment to facilitating and supporting socially constructed learning experiences, such as those in field-based settings, they align with Conant’s (1963) seminal study of teacher education, in which field experiences are “one indisputably essential element in professional education” (p. 142).

Learning to teach is a process fostered through an examination of theory and pedagogy and gained through experiences in formal and informal learning settings (Hallman and Rodriguez, 2015). However, as Singer et al. (2010) note, not all field-based experiences need to, or should, occur in PK-12 schools. This strengthens the argument for the inclusion of community-based field experiences within teacher education programs. In addressing how community-based contexts can be used in teacher education, Richmond (2017) argued that community-based experiences impact beliefs and understandings, including relationships between theory, pedagogy, and practice. This is especially true in community-based settings because the routines, norms, and experiences differ from those in traditional brick-and-mortar PK-12 schools. These differences can serve to more readily disrupt apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975) in ways traditional PK-12 school settings cannot.

For example, McGregor et al. (2010) studied community-based experiences for PSTs employing an alternative placement program at the University of Victoria, Canada. These TEs placed PSTs in community-based organizations, including arts-based settings, Indigenous groups, hospitals, and non-profit organizations. When working in these settings, the authors recognized an avenue to disrupt traditional notions of teaching and schooling. As noted previously, most literature centers on disrupting PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). As such, these authors noted that

Our goal has been to disrupt and unsettle the more normalized ways in which the field experience is characterized within our teacher education [program] while simultaneously introducing preservice teachers to their roles as civic educators and leaders…. Early findings have shown the significant power of the unfamiliar in helping [preservice teachers] to unpack their own beliefs about schooling, teaching and learning. (p. 313)

This opportunity for disruption, particularly connected to community-based field placements was common throughout much of the examined literature (e.g., Holder and Downey, 2008; Mullholland et al., 2010; Harkins and Barchuk, 2015).

Based on our own work and experiences as TEs, community-based field settings provide additional important teaching and learning opportunities (Hamilton et al., 2019). While it may be useful to compare community-based field settings and those in traditional PK-12 schools, this is not the purpose of this study. Instead, through this work we seek to establish the value of community-based field settings as an addition and augmentation to traditional PK-12 school settings, rather than a replacement of or critique therein. Research indicates that alternative practicum settings, such as community-based settings, provide opportunities to learn about and engage in teaching and learning outside traditional PK-12 locations (Richmond, 2017).

Coffey (2010) argued that community-based field experiences allow for exposure and engagement with diverse settings. In her study about graduate PSTs’ work at a Children’s Defense Fund Freedom School within the context of an “introduction to teaching” course, Coffey found that this field experience provided opportunities for participants to further contextualize and understand their own biases and assumptions about teaching and learning. According to Brayko (2013), community-based settings are important and most often utilized to prepare future teachers for both the realities and possibilities of the teaching profession. Brayko’s (2013) study involved United States teacher candidates working in two community-based organizations that supported Latino and Muslim Somali children in afterschool literacy programs. For PSTs, and by proxy TEs, “community-based activity systems … made available distinctive learning opportunities beyond those typically encountered in school-based placements” (p. 52).

In Harkins and Barchuk’s (2015) study of Canadian PSTs working in community colleges, health care institutions, non-profit organizations, and museums, PSTs developed a wider understanding of themselves and their role as educators. These community-based experiences complemented PSTs’ traditional, PK-12 school-based experiences and provided TEs and PSTs opportunities to expand their understanding of teaching and learning. In physical and health teacher education, Yi and Lee (2018) suggest that when working in community-based settings PSTs can positively contribute to local communities’ overall health and sustainability. Thus, working in community-based settings supports the belief that when TEs and beginning teachers work within the contexts of community-based settings, there exists more opportunities for learning, growth, and change (Hamilton et al., 2019).

Furthermore, community-based field settings also support socially constructed learning and knowledge creation. This knowledge and learning are the direct result of working in these particular community contexts, including interactions and experiences with others in these settings (Hallman, 2019). Thus, when facilitating community-based field experiences, TEs should engage in a “pedagogy of investigation” (Ball and Cohen, 1999; Hamilton et al., 2019). Doing so affords opportunities to challenge, interrupt, and expand formalized notions of teaching and learning (Hallman, 2012). Participation in this “pedagogy of investigation” (Ball and Cohen, 1999) affords TEs opportunities in which they may seek to identify and understand their own as well as others’ apprenticeships of observation. As Loughran and Menter (2019) noted, teaching others how to teach is a sophisticated endeavor. Thus, TEs must actively work to challenge traditional approaches to teaching and learning. To accomplish this, TEs need to actively engage in explicit reflection and discussion, while also acknowledging and critiquing their pedagogy and practice.

Method

Collaborative self-study provides TEs opportunities to engage in a “pedagogy of investigation” (Ball and Cohen, 1999) and to learn from one’s own teaching experiences (Hammerness et al., 2005). For TEs, one place to engage in a “pedagogy of investigation” is within field-based experiences, which are a central tenet of global teacher education (Darling-Hammond, 2017). As a methodology, self-study enables TEs to engage in reflection-in-action (Schön, 1983) and positions TEs’ research within their own lived experiences (Kitchen, 2020). Engaging in this works supports the “lifelong ability to learn from teaching, rather than a more contained image of learning for teaching” (Hammerness et al., 2005, p. 405). Moreover, self-study provides opportunities to explore questions of practice that are individually and collectively important to the field (Pinnegar and Hamilton, 2009). As Kitchen (2020) notes, self-study methodology is an effective and meaningful approach TEs can use to develop self-knowledge. Similarly, self-study methodology enabled use with a means to explore and examine our own apprenticeships of observation while increasing our understanding of ourselves and the ways in which we approach our work as TEs. Methodologically, self-study provides opportunities to gain insights about our experiences, including our own teaching and learning (Ritter et al., 2018). Moreover, we have not yet found a study in which TEs utilized self-study methodology to explore and examine their own apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Thus, in addition to addressing this study’s research question, this study has the potential to contribute to TEs’ use of self-study methodology to explore and examine their own apprenticeships of observation.

Participants

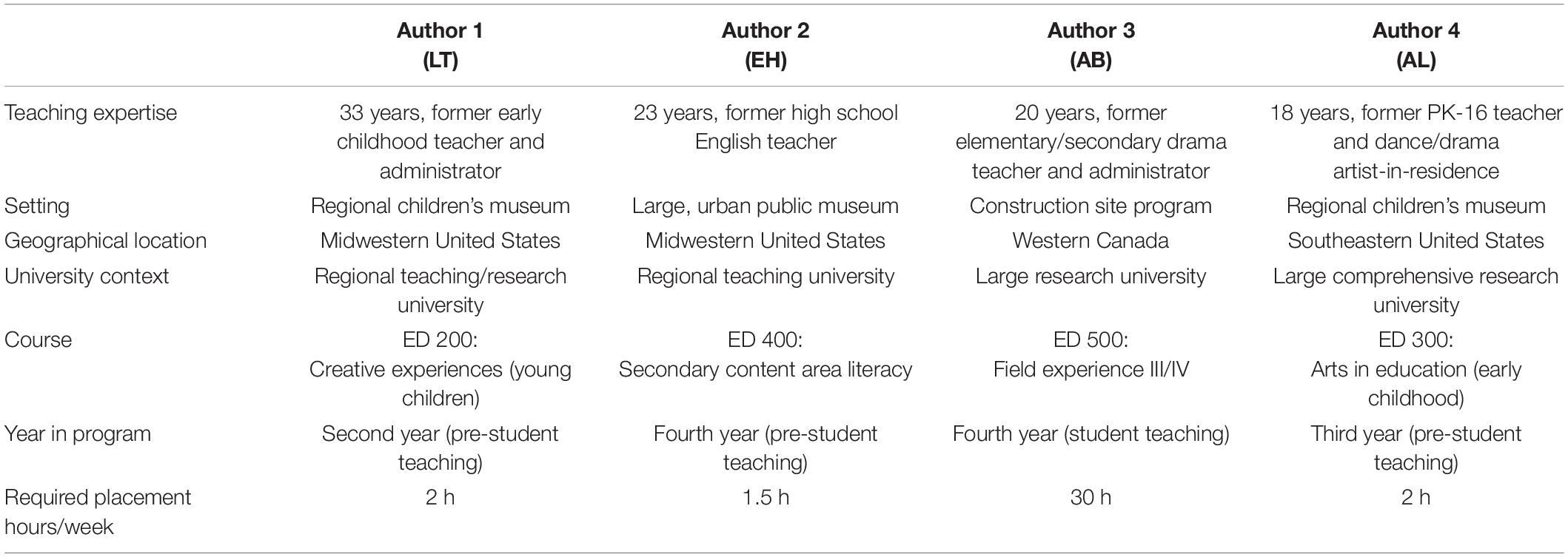

We first met at an international education conference in the spring of 2017. Based on our common interests and roles as TEs, we embarked on research that is now in its fourth year. We self-identify as TEs committed to facilitating meaningful, connected field experiences for PSTs and continuing our own professional learning and development. As participants in this collaborative 3-year self-study, we also represent various experiences, locations, and expertise (pseudonyms used for all names, locations, and identifying information) (Table 2).

Noted in Table 2, as TEs we have varying experiences and have worked in traditional school settings (e.g., EH, who taught five English classes/day and utilized district-mandated common assessments) as well as non-traditional educational settings (e.g., AL, who was formerly employed as an artist-in-residence).

To understand the ways our past experiences informed our present pedagogies and practices, including potential biases, throughout the past 3 years we’ve regularly shared and reflected on our own educational experiences, prior to and after becoming TEs. For example, despite growing up in various parts of the United States and Canada, as PK-12 students all of our educational experiences took place in brick-and-mortar schools in which students were organized and instructed by grade and age. As learners, most of our experiences included teacher directed learning and lecture-based, assignment-centered assessments. This is in contrast to a model of ELT (Kolb, 1984) that would be more likely reflected in models such as project-based learning, place-based education, and inquiry-based learning. Our PK-12 school years started in late summer and ended in late spring. As PSTs, LT, EH, and AB completed all required teacher education fieldwork in traditional PK-12 school settings and classrooms. Although AL did not originally train to be a PK-12 teacher, AL has experiences as a substitute teacher, PK-16 teaching artist, and curriculum specialist in community arts education.

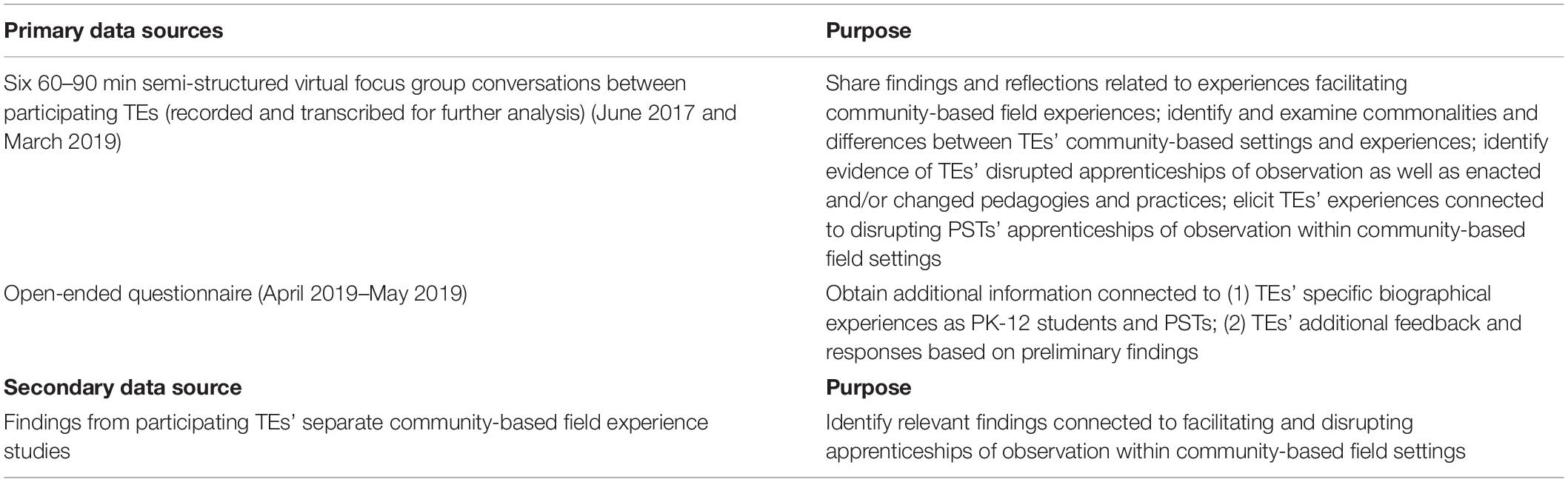

Data Collection

To triangulate and strengthen this self-study’s findings, we identified and analyzed primary and secondary data sources (Newby, 2010; Table 3).

These data serve to capture and establish relevant findings, including reflections, experiences, and evidence connected to our experiences, as TEs, working in community-based settings. Based on initial findings, we noted a number of instances in which we shared observations and changes we made that aligned with Lortie’s (1975) apprenticeship of observation concept. To explore to what extent, if any, the ways our own apprenticeships of observation were enacted, challenged, and/or changed through facilitating community-based field experiences, LT and EH developed an open-ended questionnaire to gather additional reflections, observations, and feedback, experiences, and observations, shared via email (Appendix). Separately, we generated responses to the three questions over a 2-week period. Once completed, we read through and analyzed our separate responses. Answers to these questions provided additional opportunities to reflect on preliminary findings as well as elicit more information and clarification related to the ways working in community-based field settings served to disrupt any of our own apprenticeships of observation.

Data Analysis

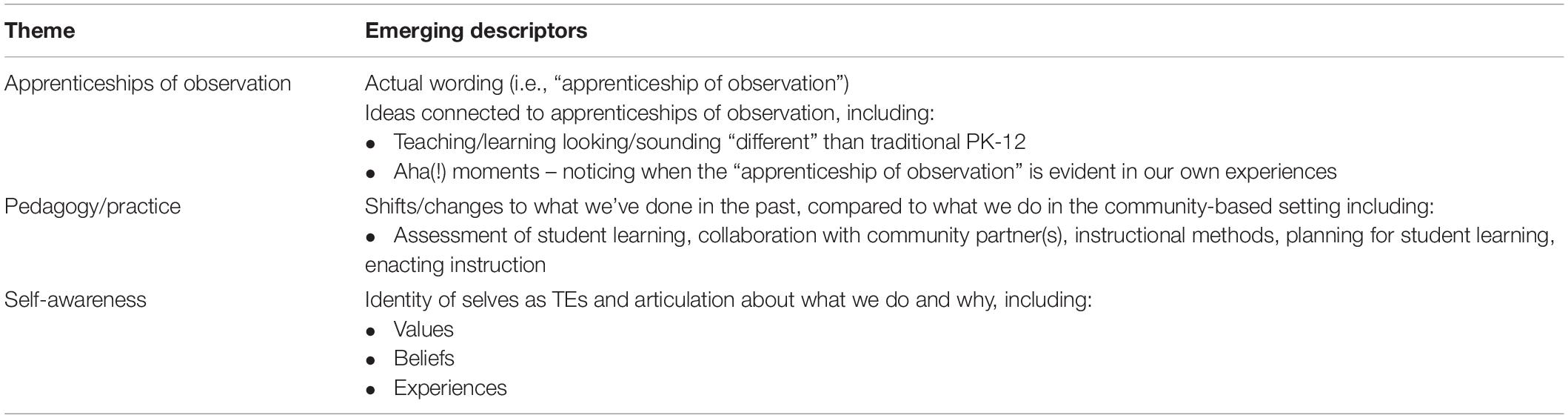

As this was a collaborative self-study, we first treated ourselves as separate cases (Creswell, 2012), in which we sought to identify and highlight our individual perspectives and experiences. In this phase, we utilized the interview transcripts to generate overviews of each of our community-based field settings (i.e., three museums and a construction site), including settings, duration, our experiences working in these settings, and what we observed and learned about ourselves as a result of working in said settings. Learning about one another’s work helped us identify common experiences and begin to consider how our experiences working in community-based settings served to, if at all, disrupt any of our own apprenticeships of observation. Using cross-case analysis (Yin, 2009), we then read through all primary and secondary data sources, comparing commonalities and contrasting differences. Through this iteration of analysis, three themes emerged (i.e., apprenticeships of observation, pedagogy/practice, and self-awareness) (Table 4).

To compare and contrast our experiences, we then completed independent thematic analyses (Miles et al., 2014) of the six transcripts (Table 4).

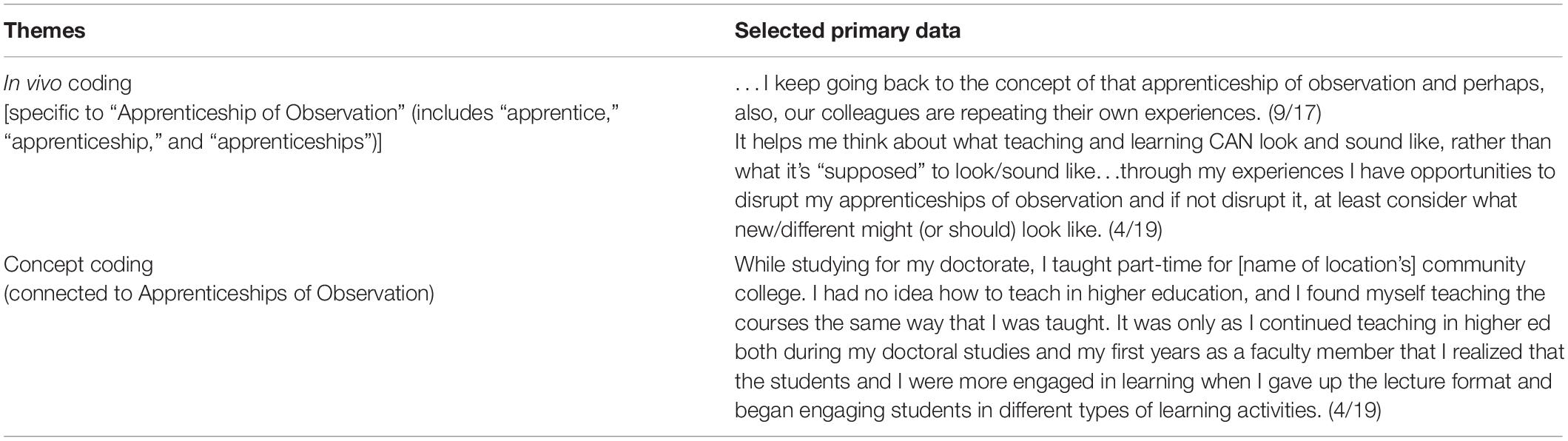

As we examined data connected to the three themes that emerged, we noted ways the second and third themes (i.e., pedagogy/practice and self-awareness) actually served to inform and provide additional information about many of the apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975) we identified. We then engaged in another round of coding, using a combination of in vivo coding (Miles et al., 2014) and concept coding (Saldaña, 2016). During this coding iteration we looked specifically for evidence related to any disruptions of our own apprenticeships of observation present in the data, specifically disruptions resulting from facilitating community-based field experiences (Table 5).

After completing this additional round of coding, particularly the emergence of the three themes (Table 4), we met to review analyses results. In this meeting, AB shared their prior knowledge of Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT, noting potential connections between our initial findings and the ELT framework. LT, EH, and AL then reviewed the ELT framework, including engaging in an additional literature review. We then met again after completing our review of the ELT framework and noted the potential of this framework as a way to understand and frame this study’s findings. As a result, we then sought to more clearly identify and understand how Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT could be used inform our understanding of how working in community-based settings served to disrupt some of our own apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Throughout the analysis process, we met often and engaged in inter-rater reliability and member-checking multiple times (Miles et al., 2014).

Additionally, to align Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT to all data, LT and EH met three more times. First, we met to clarify our understanding of ELT. This resulted in agreed upon understandings and definitions of the four stages (Table 1). Using these stages as four separate codes, we applied them to the study’s data. First, we coded a portion of the data separately, using the four ELT stages as codes, and then we met again to compare and discuss codes. During this process, we further refined our understanding of these four stages, achieving 85% inter-rater agreement. We then coded the remaining data separately, meeting a third time and achieved a 90% inter-rater agreement.

We then met with AB and AL to review Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT definitions and share initial coding. After this meeting, AB and AL completed independent coding of data, again using the four ELT stages as codes. In this process, they identified disagreements and questions. During a follow-up meeting with all four of us, we discussed AB’s and AL’s coding and observations and reached 95% inter-rater reliability. This round of coding showcased clear connections between existing data and the four stages present in ELT (Table 6).

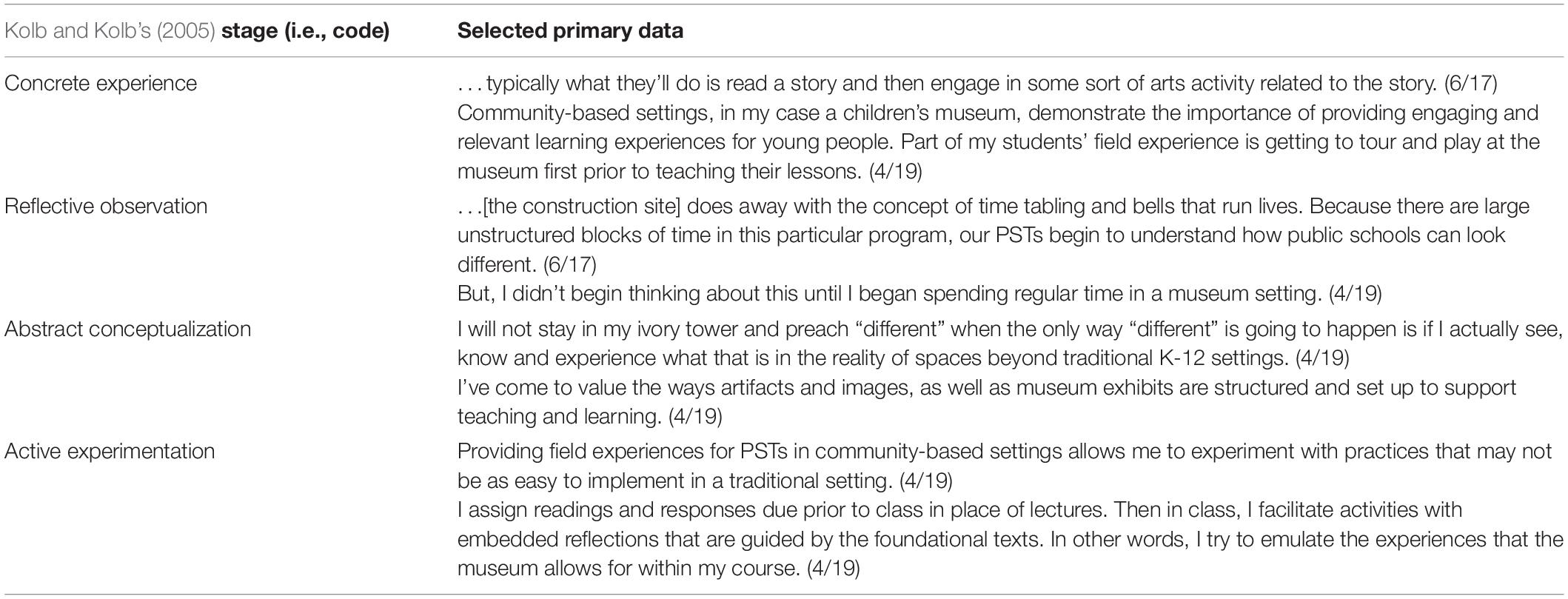

Table 6. Kolb and Kolb (2005) ELT stages coding.

Aligning Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) stages to the data provided further clarity and additional understanding regarding our disrupted apprenticeships of observation, specifically aligned with working in community-based field settings. Thus, drawing on the four ELT stages and aligning them with this study’s data led us to further identify ways working in and facilitating community-based field experiences served to make evident and, in some instances, disrupt some of our apprenticeships of observation.

Findings

Benefits of Community-Based Field Experiences for Teacher Educators

As this study’s data shows, we’ve come to realize that working in community-based settings afforded opportunities to work with colleagues not trained to facilitate traditional PK-12 teaching and learning. For example, in partnership with colleagues in these settings, we worked to identify, understand, and align our partners’ needs with our respective teacher education programs’ curriculum and goals. For example, AL worked closely with the children’s museum education team, program director, and CEO to identify resources, schedules, and expectations for the weekly arts-centered lessons their PSTs planned and implemented. Although this collaboration required extra planning and coordination, it afforded opportunities to better understand the needs of the children’s museum staff and patrons, which was then shared with PSTs. As AL came to articulate, these needs were different than those of a traditional PK-12 educator because these arts-based learning experiences were scheduled, one-time experiences that occurred in a museum and included children and care-givers, who often varied from week to week.

Similarly, EH routinely met and co-planned with a sixth-grade teacher as well as museum personnel to identify learning outcomes for the sixth-grade students enrolled in the museum middle school and EH’s PSTs. Although co-planning was not an unfamiliar experience for EH, unlike a traditional PK-12 classroom setting, this planning and coordination included identifying how to use the museum space, specifically exhibits and artifacts, to support and extend teaching and adolescents’ literacy development. Prior to this partnership, EH had no experience working or teaching in a museum space, which meant that EH’s prior learning and teaching experiences were not as useful and there was more opportunity to imagine and plan what this could look like and be. Although AL had previously taken PSTs on field trips to museums, neither they or their students had taught in museum spaces. Like EH, this partnership presented an opportunity to develop new ideas and skills, in AL’s experience such planning needed to be commensurate with play- and arts-based learning designed not for brick-and-mortar classroom settings but, rather, for a more fluid, less-predictable community setting in a children’s museum. As such, these new experiences served to challenge some of our own apprenticeships of observation about how to plan, implement, and support teaching and learning in community-based settings.

These community-based field settings also encouraged on-going reflection and afforded each of us opportunities to experience teaching and learning outside traditional K-12 settings. This is an important finding as much of the research connected to community-based field experiences focuses almost exclusively on benefits for PSTs and inservice teachers. For example, when sharing their experiences teaching PSTs in a museum setting, LT noted multiple times how the setting itself required additional flexibility and adaptability. Additionally, working in this setting meant being in a public space, where teaching was no longer lecture-based but focused on interacting with and learning from the museum setting, including patrons, employees, exhibits, and artifacts. As a result, LT purposefully changed their teaching to include new approaches, such as requiring PSTs to observe patrons, particularly children, and the ways their interactions and play in the museum setting reflected specific theories.

In a construction site setting, AB observed and collaborated with inservice and PSTs working with tenth-graders in heated garages on two separate construction sites. AB observed and assessed interdisciplinary teaching and learning and worked with inservice educators and trade professionals, helping PSTs make connections between required curriculum and the construction of two houses. For AB, observing and supporting teaching and learning on a construction site was a new and uniquely different experience. Previously, AB had only attended and worked in traditional PK-12 school settings. This community-based setting challenged AB to rethink and, in some instances expand as well as change, their preconceived notions of teaching, which directly informed the ways AB observed, understood, and provided feedback on the teaching and learning that occurred.

Apprenticeships of Observation

When analyzing the data, we uncovered evidence regarding ways community-based settings helped us identify and, at times, disrupt our own apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Our responses in focus group conversations often focused on the ways we sought to use community-based field experiences to disrupt PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation. When examining our commitment to disrupting PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation, we more clearly came to understand how facilitating community-based field experiences also served to disrupt some of our own apprenticeships of observation, which was especially evident in the Spring 2019 questionnaire responses.

For example, EH noted how perpetuating one’s apprenticeship of observation – gained in traditional PK-12 school settings – doesn’t necessarily serve to benefit learners, PSTs, or TEs.

We cannot keep doing the same thing over and over – we deserve better and so do our PSTs and their students, not to mention my own children. Doing the same thing over and over again, like we seem to do in traditional PK-12 settings, but expecting different results doesn’t work.

Similarly, AB reflected on the ways community-based settings serve to expand one’s understanding of teaching and learning. This was in contrast to “traditional PK-12 school,” a system and setting AB first learned in and later worked as a teacher and administrator. AB explained,

Community-based settings allow me, as the instructor, to see the innovative conceptions of education being implemented. I think it is very easy, as instructors, to become too firmly lodged in the place of education as being the traditional PK-12 school when in fact education happens all around us. When I am able to go into a community-based setting I find myself more able to see what may be invisible in other more traditional settings such as the teaching that informs non-curricular activities.

Having attended and graduated from a traditional PK-12 school, AL also had experiences as a PK-16 teaching artist and reflected on how these informed their understanding of teaching and learning.

As a dancer and artist-in-residence in schools, I found so much potential for PK-12 education. I also saw how the arts or arts educators were marginalized as “not academic.” I also saw very traditional forms of teaching the arts, especially in conservatory-like models in dance in my schooling. While that is helpful to train dancers, they can also be oppressive.

LT also reflected on the influences of their own apprenticeships of observation, including how this appeared during their doctoral work and early in their career in higher education.

While studying for my doctorate, I taught part-time for [State’s] statewide community college. I had no idea how to teach in higher education, and I found myself teaching the courses the same way that I was taught.

Findings indicate that our own apprenticeships of observation were most often the result of our experiences as students in traditional PK-12 schools and universities. When working in community-based field settings we noticed the ways in which we shifted how and where we taught. We also came to understand how important these experiences were for our own development as TEs, including how they served to disrupt some of our apprenticeships of observation.

Disrupted Apprenticeships of Observation and Experiential Learning Theory

Stated earlier, experiential learning is an important component of teaching and learning (Dewey, 1938). When using Kolb’s (1984) ELT we have a model by which to examine our experiences as TEs facilitating community-based field experiences, in which teaching and learning occurs outside traditional brick-and-mortar classrooms. As such, ELT presents a particular way through which to examine how, if at all, working in community-based field settings can serve to challenge TEs’ apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). As such, in this section we first examine our experiences with the ELT model and explore how we experienced ELT’s dialectically related modes. Then, using the ELT model, we present results connected to how, if at all, working in and facilitating community-based field settings served to disrupt our own apprenticeships of observation.

Concrete Experience and Abstract Conceptualization

When we analyzed the data, we noted evidence of concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations (Table 1). For example, describing a concrete experience connected to teaching and supervising PSTs in a museum setting, EH explained,

When I walk around the museum, listening in and observing the small groups I realize that although there are familiar components of “traditional” teaching and learning embedded in the [PSTs’] small groups’ work, much of this is “different” than what I ever experienced. It helps me think about what teaching and learning can look and sound like, rather than what it’s “supposed” to look/sound like.

As a result of this concrete experience, EH’s abstract conceptualization resulted in pushing them to shift away from their own apprenticeships of observation.

I roll up my sleeves, dig in, get uncomfortable, wrestle with how to make things work, stay nimble, and lean in. I have to. I will not stay in my ivory tower and preach “different” when the only way “different” is going to start/happen is if I actually see/know and experience what that is in the reality of spaces outside and beyond traditional K-12 settings.

In similar ways, AL’s concrete experience working in a children’s museum led them to understand that, “…in many ways, the community-based field experiences feel more like home to me.” AL later explained, by way of abstract conceptualization, that “…educating children [in the museum] helps me know how diverse teaching and learning can be and that we need to acknowledge and embrace that diversity, too.”

When describing their concrete experience working with PSTs in a regional museum, LT shared, “When the students were roaming the museum to observe children at play, I had no idea what types of play they would see….” Later, LT noted that “teaching in a community-based setting allowed me to observe – in my students – what I wanted them to learn when working with children.” For LT, the very nature of the setting (i.e., children’s museum) was different from what either LT (or their PSTs) observed or experienced in their own PK-12 schooling. In this instance, the focus was on learning through play. Although a central tenet in many traditional early childhood classrooms, this focus was completed in a community-based setting specifically designed for play and exploration, rather than a classroom setting in which play occurs. Drawing on their concrete experiences observing PSTs teaching in two classrooms on a construction site, which housed an interdisciplinary program designed for tenth graders to complete academic coursework and work alongside professional builders to build two houses, AB noted through abstract conceptualization that this experience challenged them, and the educators with whom they worked, “…to examine our preconceived notions of what a learning space looks like.”

These examples indicate how our concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations, generated in community-based settings, provided opportunities to identify some of our own apprenticeships of observation. Additionally, these specific concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations also presented opportunities to begin challenging particular apprenticeships of observation, including thinking beyond brick-and-mortar school settings to reconsider what constitutes a learning space and reimagine when and where teaching and learning can and do occur.

Reflective Observation and Active Experimentation

In addition to concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations, we also noticed ways our own disrupted apprenticeships of observation were evident through reflective observation (i.e., planning/trying out what you have learned) and active experimentation (i.e., reviewing/reflecting on the experience) (Table 1). For example, when reflecting on their experiences working in a regional museum, LT stated

I’m realizing that my desire to have students in community-based settings is in some ways an extension of having students more actively engaged in their learning. Students and sometimes even I have to wrestle with real-life experiences – the expected, the unexpected, and the unknown.

This led to LT’s active experimentation, as they noted that, “Providing field experiences for PSTs in community-based settings allows me to experiment with practices that may not be as easy to implement in a traditional setting.” Similarly, when reflecting on their experiences teaching in children’s museum, AL noted

I have stopped lecturing and discussing readings in class at length since I am not sure as an arts in education professor that these are the most effective at getting my points across.

As a result of this reflective observation, AL’s active experimentation resulted in the following.

[Now] I assign readings and responses due prior to class in place of lectures. Then in class, I facilitate activities with embedded reflections that are guided by the foundational texts. In other words, I try to emulate the experiences that the museum allows for within my course.

Connected to structuring and supporting student learning in a museum setting, EH shared the following reflective observations. “Working in the museum has pushed me to think about how small group work and a public museum setting can be used to engage students and their academic (and personal) learning.” Later, EH reflected,

I need to see and know what “different” looks/sounds like and the only way to do that is through experiencing it (thank you, John Dewey). Through my experiences I have opportunities to disrupt my apprenticeships of observation and if not disrupt them, at least consider what new/different might (or should) look like.

As a result, EH actively experimented with new practices. For example,

I created an assignment for PSTs to explore specific exhibits in the museum, requiring them to consider how they might use that space to teach their major/minor. Working with actual learners, I could actively connect content from the course to the setting as well as PSTs’ work with their students. The learning was no longer hypothetical or abstract, as it often was in my own experiences as a student and even when I was a high school teacher.

Working in a community-based setting provided multiple opportunities for reflective observations. For AB, this meant reconsidering what student learning looked like on a construction site. “Movement and collaboration were inherent in the space so everyone had to let go of traditional notions of what it means to ‘pay attention’.” This challenged AB to actively experiment with how to effectively observe these PSTs, which meant AB purposefully deviated from a traditional model of observation in which classroom management and student behaviors are typically prioritized in an observation. Explaining how conducting an observation on a construction site differed from a traditional PK-12 classroom observation, AB explained what they did differently.

The one thing I can add is that it did change how I observed their teaching so assessment was definitely affected. The space allowed me to focus on those inquiry-based and interactive components without getting distracted by what one might call traditional classroom management.

Connected to observing PSTs in community-based settings AB also actively reflected that

In community-based settings I find myself noticing the ways in which youth and children moderate their own learning and the ways my PSTs are able to be a part of that instead of noticing only the ways in which my preservice teacher is leading the learning.

LT also noted that the nature of the community-based setting challenged each participating TE to make adjustments to their pedagogy and practice. LT explained, “I would say the setting/space required/demanded [change] because I couldn’t just do what I had previously done or teach in the same ways I had when working within the four walls of a traditional classroom.” Although we noted evidence of our own apprenticeships of observation through concrete experiences and abstract conceptualizations, it is important to note that the disruptions we noted and experienced were most readily realized in our reflective observations connected to working in community-based experiences. And, the ways we sought to address and challenge our own apprenticeships of observation were accomplished through active experimentation.

Discussion

As a result of this collaborative self-study, as TEs we’ve come to better understand the benefits of working in and facilitating community-based field experiences, not as a replacement for traditional brick-and-mortar PK-12 classroom experiences but in addition to such experiences. Moreover, we recognize that facilitating and working in community-based field settings can, and in our case did, serve to disrupt some of our apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). As TEs, our shared commitment to engage in work that challenged PSTs’ apprenticeships of observation (Hamilton et al., 2019) actually served to challenge some of our own apprenticeships of observation. Additionally, when examining this study’s data Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) four stages and their assigned modes of (1) grasping experience (i.e., concrete experience and abstract conceptualization) and (2) transforming experience (i.e., reflective observation and active experimentation) were helpful as we sought to note and name the ways facilitating community-based field experiences challenged some of our apprenticeships of observation. However, our experiences also revealed that these stages are more fluid and not always aligned in the dualistic ways Kolb and Kolb (2005) suggested.

Community-Based Settings and Disrupted Apprenticeships of Observation

This self-study’s findings align with others’ work, supporting the idea that working in community-based field settings provides opportunities for new ideas and experiences that differ significantly from those derived from working in traditional PK-12 field placement settings (e.g., Barchuk et al., 2015; Hallman and Rodriguez, 2015; Gillette, 2017; Hallman, 2019). Thus, it stands to reason that including and working in community-based field settings within traditional teacher education programs can be important for TEs’ learning (Hamilton et al., 2019) as we already know it is for PSTs’ development (e.g., Zeichner, 2010; McDonald et al., 2013).

To illustrate, when working on a construction site, AB regularly engaged with educators, students, and professionals in their work focused on building homes for local families. In this and the various museum settings included in this study, there existed additional purposes for teaching and learning (e.g., exploration, preservation of the past, storytelling, building homes, service to the community). Based on our experiences, these community-based field settings offered a different type of unpredictability that required a new type of flexibility and adaptability generally not required in traditional PK-12 classrooms, which are often governed by set schedules and predetermined curriculum that groups of teachers and students follow each day.

Community-based settings and the ways teaching and learning occur present opportunities to consider and reconsider when, how, and where teaching and learning occur (e.g., Holder and Downey, 2008; Mullholland et al., 2010; Harkins and Barchuk, 2015). While almost all of the literature connected to Lortie’s (1975) apprenticeship of observation center on PSTs and inservice teachers, this study’s findings demonstrate that TEs’ apprenticeships of observation can also be challenged or changed, particularly when working in community-based settings. For example, AL no longer lectures and LT intentionally seeks to teach in ways that are responsive to the setting, rather than simply teaching how they were taught. EH is actively lessening the amount of hypothetical learning experiences they use and, instead, designing and providing more real-world, applicable learning experiences that include working in community-based settings and directly collaborating with community partners. Moreover, knowing firsthand the value of teaching and learning outside brick-and-mortar classrooms, AB continues to champion the inclusion of community-based settings within their institution’s traditional teacher education program, which now includes a construction site, farm, and multiple indigenous communities.

Moreover, the disruptions of some of our own apprenticeships of observation which occurred when working in community-based field settings are not as likely to occur in traditional PK-12 school settings because these were the settings where our apprenticeships were established (Westrick and Morris, 2016). Therefore, when and where possible, community-based settings should be included as part of teacher education programs because when working in these settings, TEs have opportunities to consider, experience, and – potentially – be apprenticed into new and different models of teaching and learning. As we know from our own experiences, when this happens TEs are less likely to consciously perpetuate the same experiences they had as students or even inservice teachers because through community-based experiences they can see, understand, and come to know teaching and learning differently.

Community-Based Settings and Experiential Learning Theory

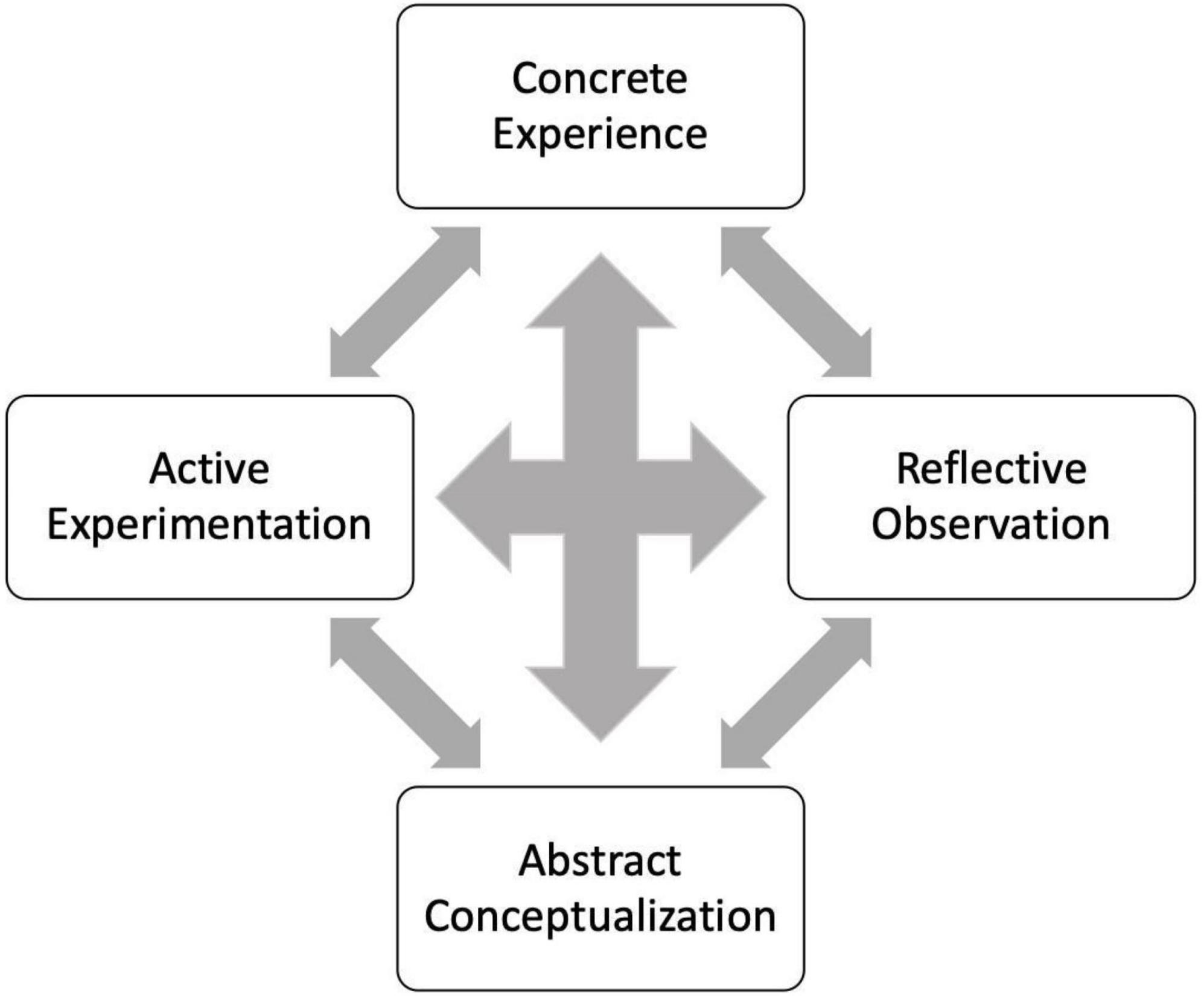

There is much power in experiential learning (Dewey, 1938; Lave and Wenger, 1991; Hallman, 2019). This power comes from the fact that it is through experience that humans learn (Kolb and Kolb, 2005). Although ELT is not without criticism (e.g., Fenwick, 2001; Schenck and Cruickshank, 2015), it was a useful framework for thinking about the ways in which working in community-based settings potentially served to make apparent and disrupt some of our apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). However, our findings reveal that we moved between and through the various stages much more fluidly, rather than sequentially or in an organized, hierarchical pattern as Kolb and Kolb (2005) suggest. To represent our experiences with ELT, we designed a visual that (1) reflects the interrelatedness among and between the stages and (2) demonstrates the recursive and fluid nature of ELT (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Authors’ proposed reconceptualization of the fluid and recursive nature of Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT.

Based on our experiences as TEs working in community-based field settings, this figure reflects the fluidity and recursiveness of ELT, an important finding when considering the ways in which TEs’ apprenticeships of observation can be disrupted when working in community-based field settings.

A tenet of ELT is that new ideas are formed and the opportunity for a transformative experience becomes possible through the “two dialectically related modes of grasping experience – Concrete Experience (CE) and Abstract Conceptualization (AC) – and two dialectically related modes of transforming experience – Reflective Observation (RO) and Active Experimentation (AE)” (p. 194). These authors suggest that these stages and their progression are not unidirectional or sequential and, yet, they present these stages as two parts of a whole, namely grasping experience and transforming experience. While our experiences working in community-based field settings provided opportunities for new ideas and transformative experiences – which included disrupted apprenticeships of observation – we found that our experiences did not always align or follow Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) dialectically related models.

Moreover, when looking for evidence of disrupted apprenticeships of observation, we noted that most often our concrete experiences were directly followed by reflective observations, rather than abstract conceptualizations. Additionally, when generating abstract conceptualizations, these were often followed by active experimentation. What this tells us is that while Kolb and Kolb’s (2005) ELT provided a useful framework to name and understand our experiences related to our own apprenticeships of observation, the stages were not linear or dialectically related. Reflecting on the coding process we also noted that we, perhaps unconsciously, expected a more linear movement from concrete experience to reflective observation – which would then be followed by abstract conceptualization and active experimentation.

Although we identified evidence of all four stages, our analysis demonstrates a much more fluid, nuanced means of learning through and from our experiences. This mirrors Bergsteiner et al.’s (2010) suggestion that, perhaps, there is a need to redesign the ELT model. Based on our findings, it is clear that experience can and did serve to disrupt some of our apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). For us, these disruptions occurred as a result of facilitating and working in community-based field settings. However, our concrete experiences were not necessarily followed by abstract conceptualizations, nor were our reflective observations directly tied to active experimentation. Instead, our experiences became the basis for reflection, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation, but these did not necessarily occur in tandem with one another or sequentially.

One outcome of this study is to encourage TEs to actively identify, and when possible, seek to disrupt, their own apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Based on our experiences, this is especially likely to occur when working in and facilitating community-based field experiences. However, not all TEs have ready access to such field settings. This is not to say that TEs cannot engage in this important work. Recognizing the fluid and nuanced ways in which TEs can learn through and from experience, including those connected to brick-and-mortar school settings, we propose that TEs may still be able to disrupt some of their own apprenticeships of observation when they seek out ways to name and consider their concrete experiences. In doing so, TEs have additional opportunities to consider these how their experiences may connect to and inform the ways they engaged in active experimentation, generated abstract conceptualizations, and utilized reflective observations. As our experiences tell us, this process will likely be fluid and recursive, if it is to be useful for TEs to identify and disrupt their own apprenticeships of observation.

Limitations

Working in the United States and Canada, we have utilized community-based locations at three museums and a construction site. We acknowledge not all TEs have such opportunities. We also recognize that although we each learned and taught in traditional K-12 schools, our research demonstrates distinct benefits of community-based settings for PSTs (Hamilton et al., 2019). Thus, we readily name our bias in believing in the power of including community-based field settings within teacher education programs. Although our results are not generalizable, TEs at other institutions may find that expanding their teacher education programs to include community-based field settings can serve to disrupt more apprenticeships of observation. Moreover, the disruption of TEs’ apprenticeships of observation could likely occur in a variety of community-based settings, not just the ones we’ve described. It may also possible for TEs to identify and disrupt apprenticeships of observation within brick-and-mortar classroom settings (beyond the scope of this study).

Conclusion

As this and other studies demonstrate, community-based field experiences present opportunities for those involved – including TEs and their PSTs – to interrupt formalized, traditional notions and models of PK-12 schooling and teacher education (Zeichner et al., 2014). To ensure TEs don’t continue to perpetuate traditional models of PK-12 education because these are what they know and are familiar with, they must be willing to identify and challenge their own apprenticeships of observation (Lortie, 1975). Although these results are not generalizable, for us there is compelling evidence that working and teaching in community-based settings expands TEs’ understanding and these were the settings in which some of our own apprenticeships of observation were disrupted. No matter the setting, it is important for TEs to intentionally name and seek to understand what informs their pedagogy and practice, including their apprenticeships of observation. Doing so can bring about change and growth, with the goal that whatever models, pedagogies, and practices TEs employ, they are those that best serve teaching and learning.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Office of Research Compliance and Integrity, Grand Valley State University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

LT, EH, AB, and AL contributed to the design of the study, as well as data collection, and analysis. LT and EH contributed significantly to the writing of the manuscript, with AB and AL providing clarification and edits. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ball, D. L., and Cohen, D. K. (1999). “Developing practice, developing practitioners: toward a practice-based theory of professional education,” in Teaching as the Learning Profession: Handbook of Policy and Practice, eds G. Sykes and L. Darling-Hammond (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass), 3–32.

Barchuk, Z., Harkins, M. J., and Hill, C. (2015). “Promoting change in teacher education through interdisciplinary collaborative partnerships,” in Change and Progress in Canadian Teacher Education: Research on Recent Innovations in Teacher Preparation in Canada, eds L. Thomas and M. Hirschkorn (Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Teacher Education), 190–216.

Bergsteiner, H., Avery, G. C., and Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb’s experiential learning model: critique from a modeling perspective. Stud. Contin. Educ. 32, 29–46. doi: 10.1080/01580370903534355

Boyd, A., Gorham, J. G., Justice, J. E., and Anderson, J. L. (2013). Examining the apprenticeship of observation: the practice of blogging to facilitate autobiographical reflection and critique. Teach. Educ. Q. Summer 40, 27–49.

Brayko, K. (2013). Community-based placements as contexts for disciplinary learning: a study of literacy teacher education outside of school. J. Teach. Educ. 64, 47–59. doi: 10.1177/0022487112458800

Bullock, S. M. (2011). Inside Teacher Education: Challenging Prior Views of Teaching and Learning. The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Bullock, S. M. (2009). Learning to think like a teacher educator: making the substantive and syntactic structures of teaching explicit through self-study. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 15, 291–304. doi: 10.1080/13540600902875357

Coffey, H. (2010). “They taught me”: the benefits of early community-based field experiences in teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.014

Creswell, J. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice? Eur. J.Teach. Educ. 40, 291–309. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

Fenwick, T. J. (2001). Experiential Learning: A theoretical Critique from Five Perspectives (Information Series 385). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Forzani, F. M. (2014). Understanding “core practices” and “practice-based” teacher education: learning from the past. J. Teach. Educ. 65, 357–368. doi: 10.1177/0022487114533800

Furlong, C. (2013). The teacher I wish to be: exploring the influence of life histories on student teacher idealised identities. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 36, 68–83. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2012.678486

Gillette, M. D. (2017). Sustaining a quality education through community-based educator preparation. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 53, 148–151. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2017.1369251

Gray, P. L. (2020). Mitigating the apprenticeship of observation. Teach. Educ. 31, 404–423. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2019.1631785

Grossman, P. L. (1991). Overcoming the apprenticeship of observation in teacher education coursework. Teach. Teach. Educ. 7, 345–357. doi: 10.1016/0742-051X(91)90004-9

Hallman, H. L. (2012). Community-based field experiences in teacher education: possibilities for a pedagogical third space. Teach. Educ. 23, 241–263. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2011.641528

Hallman, H. L. (2019). “Community-based field experiences in teacher education: theory and method,” in Handbook of Research on Field-Based Teacher Education, eds T. E. Hodges and A. C. Baum (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 348–366. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-6249-8.ch015

Hallman, H. L., and Rodriguez, T. L. (2015). “Fostering community-based field experiences across contexts in teacher education,” in Rethinking Field Experiences in Teacher Preparation: Meeting New Challenges for Accountability, ed. E. Hollins (New York, NY: Routledge), 99–116.

Hamilton, E. R., and Van Duinen, D. V. (2018). Purposeful reflections: scaffolding preservice teachers’ field placement observations. Teach. Educ. 53, 367–383.

Hamilton, E. R., Burns, A., Leonard, A. E., and Taylor, L. K. (2019). Three museums and a construction site: a collaborative self-study of learning from teaching in community-based settings. Stud. Teach. Educ. 16, 84–104. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2019.1690986

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Berliner, D., Cochran-Smith, M., McDonald, M., et al. (2005). “How teachers learn and develop,” in Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers should Learn and be Able to do, eds L. Darling-Hammond and J. Bransford (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 358–389.

Harkins, M. J., and Barchuk, Z. (2015). “Changing landscapes in teacher education: the influences of an alternative practicum on pre-service teachers’ concepts of teaching and learning in a global world,” in Change and Progress in Canadian Teacher Education: Research on Recent Innovations in Teacher Preparation in Canada, eds L. Thomas and M. Hirschkorn (Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Teacher Education), 283–314.

Holder, K. C., and Downey, J. A. (2008). “Incidental becomes visible: a comparison of school-and community-based field experience narratives,” in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, (New York, NY).

Jenset, I. S., Klette, K., and Hammerness, K. (2018). Grounding teacher education in practice around the world: an examination of teacher education coursework in teacher education programs in Finland. Norway, and the United States. J. Teach. Educ. 69, 184–197. doi: 10.1177/0022487117728248

Kitchen, J. (2020). “Studying the self in self-study: self-knowledge as a means toward relational teacher education,” in Exploring Self Toward Expanding Teaching, Teacher Education and Practitioner Research (Advances in Research on Teaching, Vol. 34), eds 0 Ergas and J. K. Ritter (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 91–104. doi: 10.1108/S1479-368720200000034005

Knapp, N. F. (2012). Reflective journals: making constructive use of the “apprenticeship of observation” in preservice teacher education. Teach. Educ. 23, 323–340. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2012.686487

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kolb, A. Y., and Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 4, 193–212. doi: 10.5465/amle.2005.17268566

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lortie, D. C. (1975). Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Loughran, J., and Menter, I. (2019). The essence of being a teacher educator and why it matters. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 47, 216–229. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2019.1575946

McDonald, M. A., Bowman, M., and Brayko, K. (2013). Learning to see students: opportunities to develop relational practices of teaching through community-based placements in teacher education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 115, 1–35. doi: 10.1177/016146811311500404

McGregor, C., Sanford, K., and Hopper, T. (2010). “<Alter>ing experiences in the field: next practices,” in Field Experiences in the Context of Reform of Canadian Teacher Education Programs, eds T. Falkenberg and H. Smits (Winnipeg, MB: Faculty of Education of the University of Manitoba), 297–315.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook (3rded.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Morrison, C. D. (2014). From ‘sage on the stage’ to ‘guide on the side’: a good start. Int. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 8, 1–15.

Mullholland, V., Nolan, K., and Salm, T. (2010). “Disrupting perfect: rethinking the role of field experiences,” in Field Experiences in the Context of Reform in Canadian Teacher Education Programs, eds T. Falkenberg and H. Smits (Winnipeg, MB: Faculty of Education of the University of Manitoba), 315–326.

Pinnegar, S., and Hamilton, M. L. (2009). Self-study of Practice as a Genre of Qualitative Research: Theory, Methodology, And Practice. New York, NY: Springer.

Richmond, G. (2017). The power of community partnership in the preparation of teachers. J. Teach. Educ. 68, 6–8. doi: 10.1177/0022487116679959

Ritter, J. K., Lunenberg, M., Pithouse-Morgan, K., Samaras, A. P., and Vanassche, E. (2018). Teaching, Learning, and Enacting of Self-Study Methodology: Unraveling a Complex Interplay. New York, NY: Springer.

Saldaña, J. (2016). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Schenck, J., and Cruickshank, J. (2015). Evolving kolb: experiential education in the age of neuroscience. J. Exper. Educ. 38, 73–95. doi: 10.1177/1053825914547153

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books, Inc.

Singer, N. R., Catapano, S., and Huisman, S. (2010). The university’s role in preparing teachers for urban schools. Teach. Educ. 21, 119–130. doi: 10.1080/10476210903215027

Westrick, J. M., and Morris, G. A. (2016). Teacher education pedagogy: disrupting the apprenticeship of observation. Teach. Educ. 27, 156–172. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2015.1059413

Yi, K. J., and Lee, Y. H. (2018). Community-based experiential learning: a way of reflexive, transformative, and relational pedagogy in physical and health education teacher education (PHETE). Res. Dance Phys. Educ. 2, 29–38. doi: 10.26584/rdpe.2018.6.2.1.29

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Zeichner, K., Payne, K. A., and Brayko, K. (2014). Democratizing teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 66, 122–135. doi: 10.1177/0022487114560908

Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college and university-based teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 61, 89–99. doi: 10.1177/0022487109347671

Appendix

Open-Ended Questionnaire (May 2019)

Excerpt about this questionnaire, taken from (5/17/19) email EH sent to LT, AB, and AL.

Would all three of you be willing to share feedback/responses to one more question on our Self-Study Teacher Educator Open-Ended Questionnaire? We’re using this as an additional data source for our [study] and as we talked through this work today, we realized that it’d be helpful to have a bit more feedback from everyone.

1. In what ways does working in community-based settings further inform our pedagogy and practice?

2. How do these settings serve to disrupt our own apprenticeships of observation?

3. When working in a community-based setting, what changes to your pedagogy and/or practice occurred (and why)? Specific examples are welcome.

Keywords: self-study, apprenticeship of observation, teacher education, community-based field experiences, experiential learning theory (ELT)

Citation: Taylor LK, Hamilton ER, Burns A and Leonard AE (2022) Teacher Educators’ Apprenticeships of Observation and Community-Based Field Settings. Front. Educ. 7:754759. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.754759

Received: 06 August 2021; Accepted: 11 March 2022;

Published: 06 April 2022.

Edited by:

Eline Vanassche, KU Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Martha Prata-Linhares, Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro, BrazilShawn Bullock, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Taylor, Hamilton, Burns and Leonard. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda K. Taylor, bGh1YmVyQGJzdS5lZHU=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Linda K. Taylor

Linda K. Taylor Erica R. Hamilton

Erica R. Hamilton Amy Burns

Amy Burns Alison E. Leonard

Alison E. Leonard