- 1University of Applied Sciences for Police and Public Administration in North Rhine-Westphalia, Aachen, Germany

- 2German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany

- 3Carnegie School of Sport, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, United Kingdom

The current study explored police trainers’ perceptions of their actual and preferred methods of acquiring new coaching knowledge; the types of knowledge they currently require and/or desire; and how they apply new knowledge. A total of 163 police trainers from Germany and Austria participated in the study. The responses were analysed using an inductive approach. The results showed that police trainers thought they needed knowledge of pedagogy, policing, and self-development, with reasons being centred around a need to optimise learning, training content and the engagement of learners within the training sessions. Preferred methods of learning focused predominantly around informal and non-formal opportunities, the reasons for which were social interaction, the reality-based focus of the content and the perceived quality. Finally, police trainers identified technical or tactical policing knowledge, or knowledge specific to the delivery of police training as useful, recently acquired coaching knowledge, mainly because it was perceived to have direct application to their working practices. Based on these findings, it is suggested police trainers are in need of context-specific knowledge and support to develop the declarative knowledge structures that afford critical reflection of new information.

Introduction

In most police departments, institutions, academies and agencies, police training is considered an essential training setting for recruits and sworn officers to develop and refine their practical front-line skills, such as self-defence and arrest skills, firearms, tactical skills and communication (Staller M. and Körner, 2019b; Isaieva, 2019), in order to safely and effectively cope with operational and conflictual scenarios that are a regularly part of police work (Ellrich and Baier, 2016). Within this context—sometimes also referred to as police use of force or conflict management training—the police trainer facilitates the development of recruits through the achievement of learning outcomes (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021b). However, research from observational and interview studies has identified problematic issues with the current delivery of police training in some quarters. For instance, training might not lead to the achievement of the intended outcomes (Rajakaruna et al., 2017; Nota and Huhta, 2019; Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021a; Staller et al., 2021b). Furthermore, there is evidence of outdated pedagogical approaches in practice (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021b), and a shortfall in knowledge required by police trainers for purposeful planning and reflection on training sessions (Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021a). Such observations bring the structure of how police trainers are educated and developed into question. For the purpose of this paper, we consider the practice of police trainers as coaching (Staller et al., 2020) and therefore refer to police trainer development as coach development or coach education. There is anecdotal evidence from Germany that police trainers are assigned to coach other police officers often without formal coach education (Staller M. and Körner, 2019b). Taken in combination with evidence displaying that when coach education in police training is offered it varies in content, depth and duration (Staller et al., 2020), questions about the type, source and application of knowledge by these coaches arise.

In light of this scarcity of research in the domain of coach development in police training, the closely aligned field of sport coaching offers insights. An increasing body of research has investigated how coaches learn how to coach (Cushion et al., 2010; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). The acquisition of coaching knowledge takes place in a variety of settings, extending beyond formal coach education environments encompassing non-formal and informal self-directed learning situations (Cassidy and Rossi, 2006; Lemyre et al., 2007; Wright et al., 2007; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). Whereas formal coach education is considered as a highly institutionalised setting that is formally recognized with diplomas and certificates, non-formal coach education encompasses organised learning opportunities outside the formal educational settings, whereas informal education reflects self-driven searches for knowledge and reflection (Mallett and Dickens, 2009). In the context of police training, national regulations provide the framework for the formal coach education for police trainers. For example, in Germany, the police regulation 211 (PDV211, 2014) describes the obligation of a police force to adequately equip their coaches with the knowledge and competencies needed to deliver a police training curriculum. These formal coach education courses differ from state to state (Körner et al., 2019a). Nonformal coach education settings typically comprise of workshops, seminars and conferences that police trainers attend. Opportunities for informal coach education can arise within formal and nonformal coach education settings. Informal learning is primarily controlled by the learner and is not typically classroom based or highly structured (Mallett and Dickens, 2009). For example, police trainers discussing new operational tactics over lunch would be considered an informal learning experience. Finally, informal opportunities exist in everyday life through job experience, or personally directed searches on online and offline sources of information.

The different formats of learning seem to have a unique role in the development of coaches (Lemyre et al., 2007; Wright et al., 2007). For example, Wright et al. (2007) identified seven different learning situations accessed by ice hockey coaches as sources for their coaching knowledge, encompassing formal (large-scale coach education programs, formal mentoring), non-formal (coaching clinics and seminars) and informal learning settings (books and videotapes, personal experiences, face-to-face interactions with other coaches, the internet). Stoszkowski and Collins (2015) recruited some 320 participants for an online survey. They found that coaches prefer to acquire coaching knowledge from informal learning activities, especially when activities allow for social interaction, such as talking to other coaches. Furthermore, the data revealed that coaches employed knowledge acquired from formal coach education settings, even though this learning setting was not mentioned as the preferred source of knowledge acquisition by the majority of coaches (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015).

Abraham et al. (2010) used self-determination theory to explain why informal learning opportunities are valued by coaches; “Firstly, the coaches have autonomy of choice when they decide about what to engage with and when. Secondly, the coaches gain feelings of competence by deciding what ideas and knowledge they find useful and can work with while choosing to ignore those they don’t (especially as no one is looking over their shoulder to check understanding). Finally, by making these choices, they are more likely to gain ideas and knowledge of how to relate better to their athletes, other coaches, parents and officials. In essence, self-driven learning is by its very nature intrinsically motivating” (p.53).

That being said, Abraham et al. (2010) acknowledge that a self-determined approach to coach development inevitably leaves gaps in a coach’s repertoire of skills and knowledge (Abraham and Collins, 2011). because in the absence of conscious programme design and evaluative processes, most coaches acquire knowledge that is limited in scope, depth, breadth and interconnectivity (Gilbert and Trudel, 2001; Mallett and Dickens, 2009; Cushion et al., 2012).

It has been argued that coaches need well developed declarative knowledge structures (conceptual knowledge) to check and challenge the value of new knowledge acquired from informal learning situations (Abraham et al., 2006; Abraham and Collins, 2011). An advanced declarative knowledge base guards against coaches mindlessly mimicking the practice of other coaches (Grecic and Collins, 2013). Similarly, a heavy or even sole focus on procedural knowledge (how knowledge) limits the coach’s ability to adequately adapt to changes in the training environment and the individual needs of trainees (Staller et al., 2020). Declarative knowledge about the pros and cons of a wide range of coaching approaches is needed to make informed decisions and judgements about how best to navigate the dynamics of police training (Abraham and Collins, 2011; Staller et al., 2020). In short, knowing what to do and how to do it (procedural) is clearly important to police trainers. However, it is knowing why they are doing something (declarative), and indeed why they are not doing something else, that facilitates adaptability and criticality in coaching.

Results from Stoszkowski and Collins (2015) indicated that critical reflection and justification of the application of acquired coaching knowledge was mostly absent within sport coaches. Based on these results, the authors infer the “necessity of some element of “up front” formal learning, in order to equip coaches with the structures to ensure their informal development is sufficiently open-minded, reflective and critical” (p. 8). Indeed, appropriate formal learning may actually be crucial for the majority of coaches at different stages of their development. This may be particularly true as coaches come to understand the “relative” nature of knowledge and practice (Collins et al., 2012). With regard to police training, the potential lack of evidence-based knowledge structures for police coaches to reflect informally acquired knowledge against, may provide an explanation for the manifestation of traditional pedagogies within this specific domain (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020). However, since there is no empirical data on where police trainers get their knowledge from (the sources), what knowledge domains are relevant to them (the topics) and what they deem to be applicable to them, it would be speculative to generalise the conclusions arising from sport coaching education to the police training domain. As such, the purpose of this study was to capture police trainers’ perceptions related to the following questions:

• What they need to know more about to be a better police trainer, and why?

• Preferred source and methods of acquiring new coaching knowledge, and why?

• Examples of useful, recently acquired coaching knowledge, how it was acquired and how it was applied.

Materials and Methods

Participants

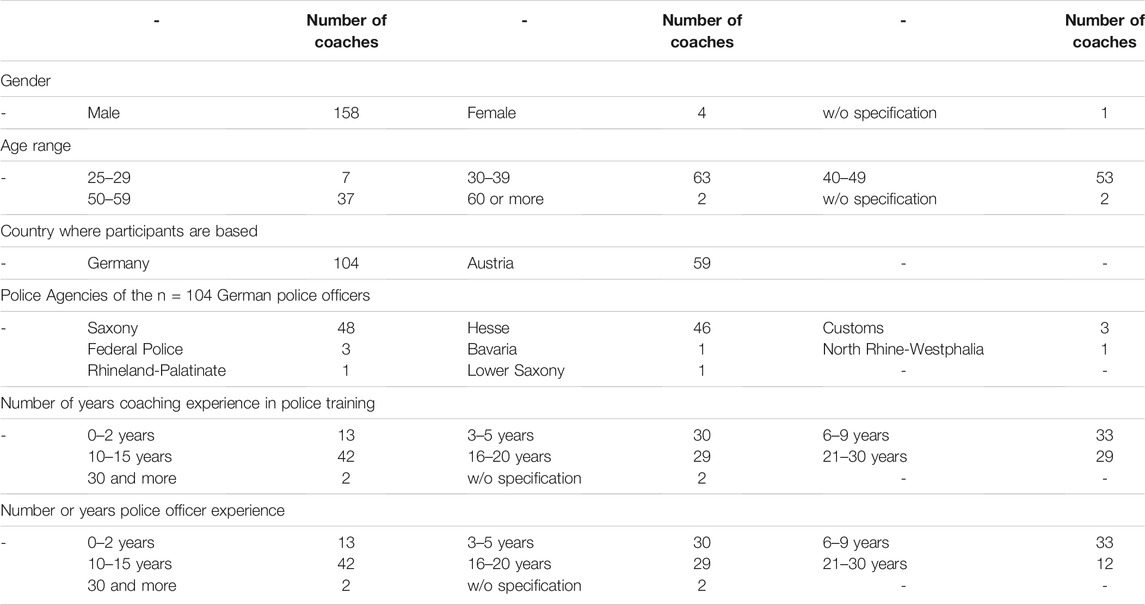

Police trainers from German speaking countries—Germany and Austria—volunteered to participate (N = 163). The German and Austrian police training programmes are collaborative in terms of knowledge exchange and take a similar view on the content and delivery of police training, which is informed by the same police training literature. Demographic details of participants are displayed in Table 1. Police trainers from Austria, Saxony and Hesse were particularly well-represented.

Online Survey

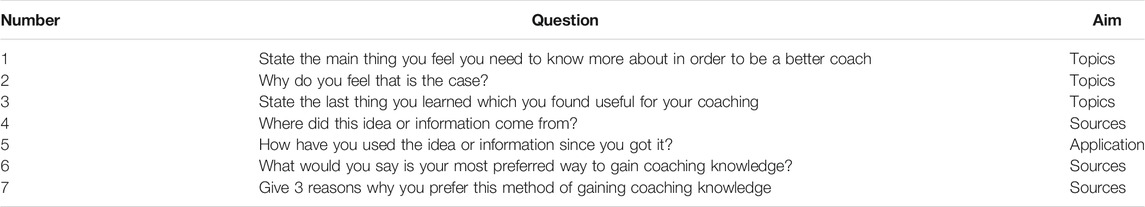

An online survey was constructed in SoSci Survey (www.soscisurvey.de) that comprised demographic questions and seven open-ended questions taken and translated from Stoszkowski and Collins (2015) who systematically developed the questions for their highly-relevant study on the knowledge acquisition of sports coaches. The online survey afforded data collection from police trainers across German speaking countries. The seven open ended-questions listed in Table 2 elicited qualitative responses about the sources the participants consult for coaching knowledge (questions 4, 6, 7), the topics of coaching knowledge they seek and acquire (questions 1, 2, 3), and the ways they use and apply the acquired knowledge (question 5). While questions 1, 2, 6 and 7 aimed at eliciting the general knowledge needs and sources of police trainers, questions 3 to 5 were aimed at their last learning experience.

Procedures

The questionnaire was distributed using opportunity sampling (Brady, 2006). The survey was initially distributed by email to a professional network of police training coaches and to gatekeepers of police trainer networks. The landing page of the survey contained detailed information about the purpose and procedure of the study and how responses to the survey would be handled. Participants were informed that they should only continue if they were active police training coaches. Participants were also informed that submitting a response would constitute consent to use the data and that they could not withdraw their data once it was submitted as no identifying information was tracked at any stage of data collection. Recruitment of participants took place over a 10-week period before the web link was deactivated.

Data Analysis

The open-ended responses consisted of a mixture of short statements and longer, more structured sentences and were subjected to an inductive content analysis (Patton, 2002) using MAXQDA 2018. The analysis followed a two-stage protocol (Nelson et al., 2013; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). First, the survey answers were treated as stand-alone meaning units. If they contained more than one self-definable point, for example, “visiting conferences and talking with peers”, they were separated accordingly. The meaning units for each item were listed and labelled, before they were compared for similarities and organised into raw data themes. Meanings units were treated as similar, when they conveyed the same idea; for example, “will boost motivation of trainees” and “officers will be more motivated”. In the second stage, the analysis proceeded to a higher level of abstraction. The raw data themes were built up into larger and more general themes and categories to form higher-order concepts (Côté et al., 1993). In order to enhance the validity of the data analysis, two researchers (MS and SK) independently familiarised themselves with the data before discussing meaning units, categories and themes to reach a consensus. If consensus was not reached initially, the researchers debated the issue of contention until consensus was achieved. Having used inductive content analysis to interpret the data into raw, lower and higher order themes, the final phase of analysis involved gaining triangular consensus between the lead (MS) and second researcher (SK) along with two additional researchers (AA and JP) who acted as a “critical friend” (Faulkner and Biddle, 2002; Kelly et al., 2018). The additional researchers were not involved with the data collection or analysis and were required to confirm, or otherwise, the placement of raw data themes into lower and higher order themes.

Enhancing Trustworthiness of the Analysis

Using guidelines relating to qualitative methods (Tracy, 2010; Tracy and Hinrichs, 2017), checks were made to ensure eight criteria of high-quality qualitative research (worthy topic, rich rigour, sincerity, credibility, resonance, significant contribution, ethics and meaningful coherence) were met. Investigating the sources, topics and application of coaching knowledge in police training was perceived to be a worthy topic. Data collection and analysis procedures were carried out systematically following established guidelines to enhance the rigour of the methodology and data analysis is described in detail for increased transparency. Sincerity was observed via two “critical friends” who checked and challenged the coherence between the data and the presented raw data themes and higher order themes. This helped maximise the trustworthiness of the analysis process. To ensure credibility, we ensured that higher order and raw themes were traced back to the participant’s statements. Furthermore, we highlighted direct quotations to support findings, which we argue demonstrated resonance as it allowed for visual representations of participants thoughts. In terms of contributing to the literature, we argue the study has theoretical (e.g., conceptual understanding) and practical (e.g., professional training programmes and applied practice) implications that will further develop this area of study. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. We also adhered to situational (e.g., reflectively discussing the analysis process with the research team and reflect on data worth exposing), relational (e.g., reflection on researcher actions and potential consequences of data analysis) and exiting (e.g., avoiding unjust or unintended consequences of findings presented) obligations. Finally, in terms of meaningful coherence, the study used methods consistent with earlier studies of coaching knowledge.

Results

Topics of Coaching Knowledge

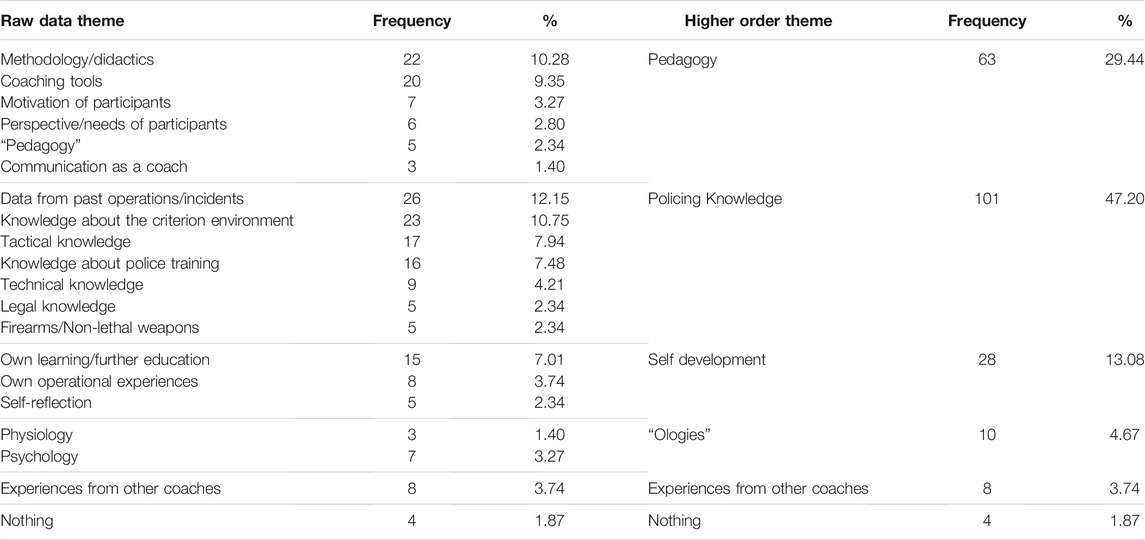

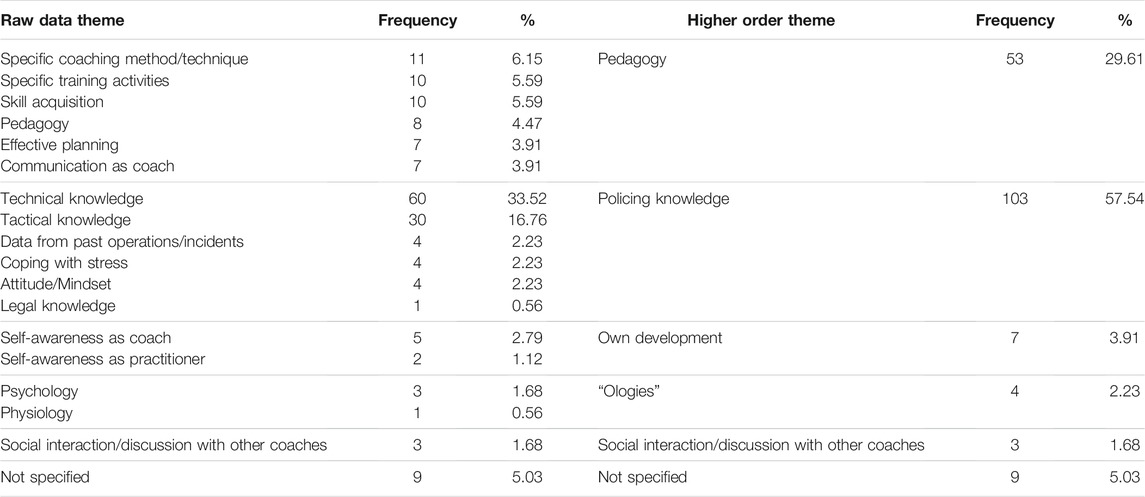

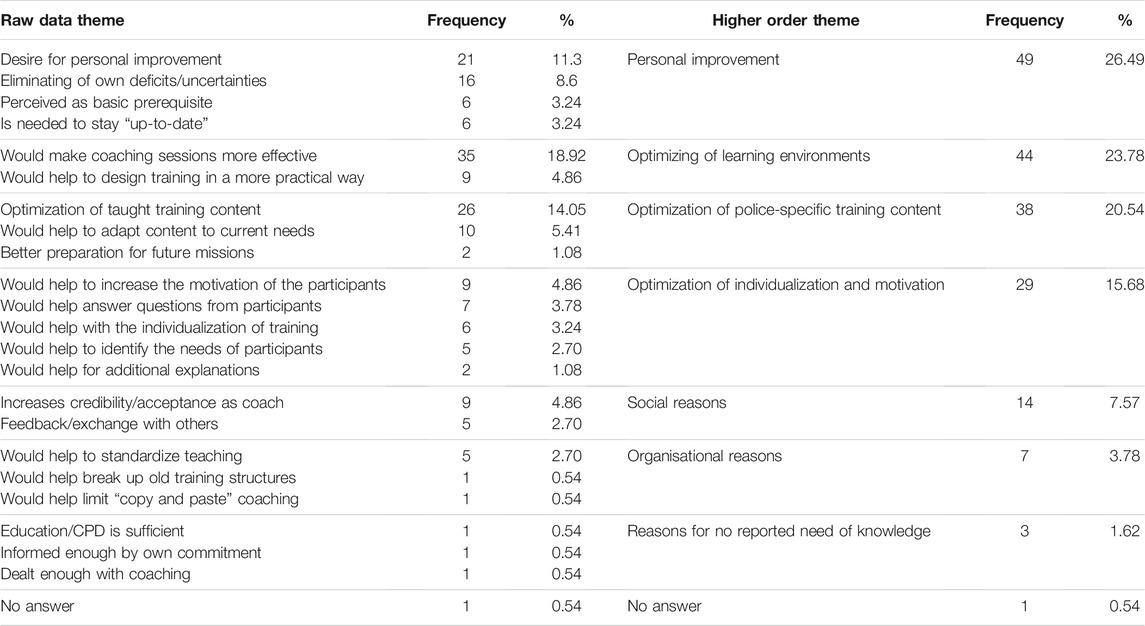

The topics that participants felt they needed to know more about to be a better coach tended to be associated with policing knowledge (47.20%) or related to coaching pedagogy (29.44%—see Table 3). Specifically, participants felt the need to know more about past operations and incidents (12.15%) and the criterion environment, like statistics and current modes of operandi (10.57%). Regarding pedagogy, the group articulated a need to know more about coaching methodology and didactics, such as teaching methods for firearms training or learning approaches (10.28%); and coaching tools, including frameworks for periodisation or training principles (9.35%). The topics of coaching knowledge specified (see Table 4) were deemed by participants to be needed mainly for personal development (26.49%); to optimize learning environments (23.78%); and to optimize the taught police-specific training content (20.54%).

TABLE 4. Participants’ perception of why they need to know the knowledge reported in Table 3.

Sources of Coaching Knowledge

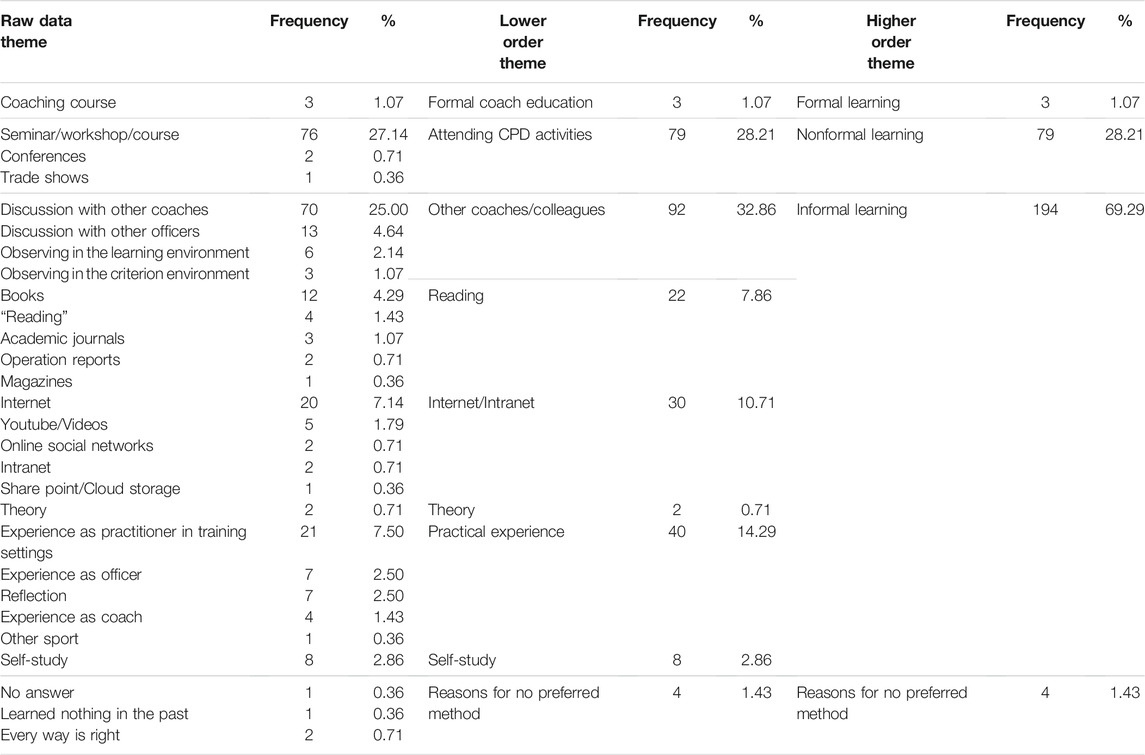

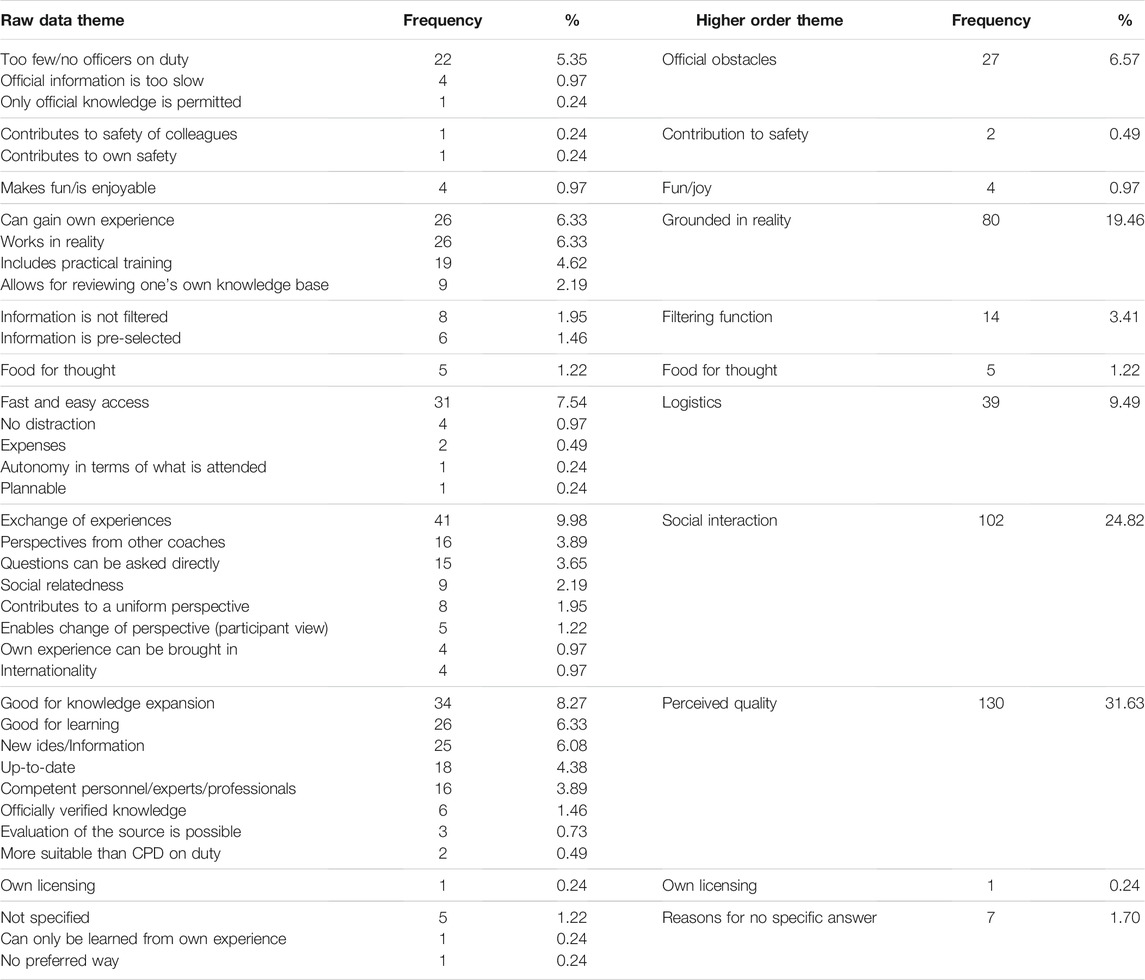

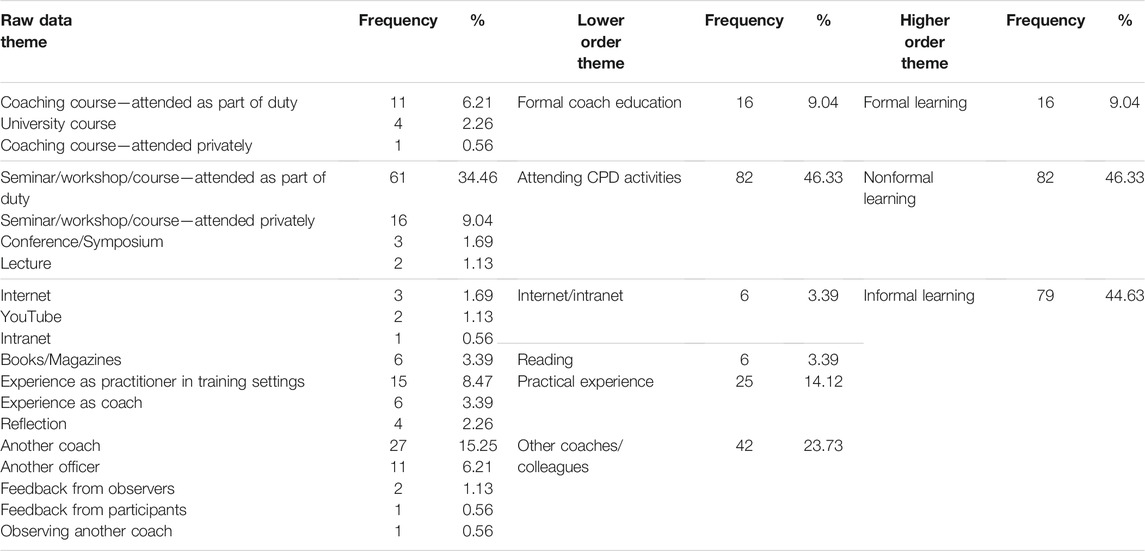

Table 5 indicates that the majority of police trainers preferred to acquire knowledge by informal means (69.29%), particularly from conversations with and observation of their peers (32.86%). Fewer police trainers referenced nonformal continuing professional development (CPD) learning activities (e.g., seminars, workshops, conferences) as their preferred learning source (28.21%). Formal learning activities were the least favoured source. Three police trainers (1.07%) preferred to acquire knowledge from formal coach education programmes. The reasons reported for why coaches prefer particular methods of acquiring coaching knowledge were wide ranging (see Table 6); however, perceived quality of the source (31.63%), social interaction (24.82%) and the preference of knowledge that is grounded in reality (19.46%) were most common.

Topics, Sources and Application of Recently Acquired Knowledge

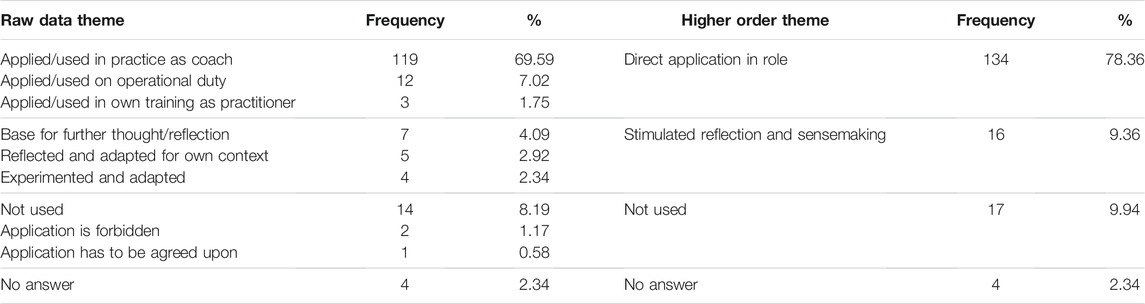

Concerning the last topic police trainers found they had learned or found useful, the results tended to be either content specific to police training (57.54%), particularly technical or tactical knowledge, or specific to the delivery of police training, that is pedagogy (29.61%—see Table 7). Police trainers indicated that knowledge was mainly gained from accessing a variety of nonformal (46.33%) and informal learning opportunities (44.63%; see Table 8). CPD seminars, workshops and/or courses either organised by the police force or privately attended were the primary source of knowledge identified. Concerning the application of that knowledge (see Table 9), police trainers primarily reported that they immediately utilised the knowledge to inform their own coaching practice (78.36%). Police trainers also reported to have further considered the newly acquired knowledge to reflect on and/or adapt their practice (9.36%); although, in nearly 10% of the cases police trainers acknowledged that the knowledge had not been used at all.

Discussion

Given recent concerns about the quality of police training delivery and the lack of empirical data about how police trainers learn to coach, the current study was designed to shed light on the acquisition of knowledge by police trainers. Structured around three main research questions, the results provide insight into what knowledge police trainers think they need, where they prefer to get it from, and how they apply their recently acquired knowledge.

Context-specificity of Police Training Knowledge

For this sample of police trainers police training specific knowledge about what to teach was commonly identified as a development need. Most frequent was the need to know more about past operations and incidents, as well as statistics and further information about the current situation on the street. The importance of domain specific content knowledge for coaches has been identified in sport (Nash and Collins, 2006; Abraham and Collins, 2011). In the distinct domain of police training, the focus on specific content knowledge may reflect the need to better understand the criterion environment and uncertainty of how to best cope with (un-)armed conflict situations in the field; and may explain the observed failure of skills learned in readily transfering to the field (Jager et al., 2013; Renden et al., 2015). Identification of the technical or tactical skill set needed on the front-line will help trainers develop a more comprehensive police training curriculum (Renden et al., 2016; Körner and Staller, 2018).

CPD activities in police training, like workshops and seminars, mainly involve police training specific content, like technical or tactical behaviour. As such it is not surprising, that this domain specific content knowledge is actually picked up by coaches from this source as the current data showed. Also, within these settings, information of past operations or incidents is disseminated via case studies and anecdotal accounts of the personal leading the CPD activities (coach developers), which satisfies the need of police trainers for further knowledge within these areas. Such educational settings also afford social interaction with other coaches and colleagues, which were a preferred knowledge source for many police trainers.

Besides the need for specific content knowledge, the findings of the current study also support the interpretation that police trainers long for police training specific pedagogical knowledge, since police trainers reported that (a) they generally wanted to know more about pedagogical aspects and (b) they prefer nonformal and in-formal sources to acquire their knowledge.

Research has consistently highlighted the importance of gaining coaching knowledge through informal, self-directed learning situations (Lemyre et al., 2007; Erickson et al., 2008; Mallett et al., 2009), which is also in line with findings from Stoszkowski and Collins (2015) who identified other coaches and colleagues as important sources of coaching knowledge. Interactions among coaches can provide valuable learning situations, in which coaching issues are discussed and strategies are developed, experimented upon and evaluated to resolve these issues (Gilbert and Trudel, 2001; Lemyre et al., 2007). Therefore, self-directed learning activities allow police trainers to tackle their specific coaching issues, an aspect that is more difficult to focus on in formal learning settings, where the agenda is somewhat fixed by the ones delivering the program. The limited impact of formal coaching courses has been documented throughout the coaching literature (Abraham et al., 2006; Lemyre et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2010). A possible explanation is that coach-education programs fail to cover complex contextual factors in the specific coaching environment (Lemyre et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2010). This is also supported by the reported need for police trainers to know more about police training specific content knowledge and pedagogical aspects. An aspect that was also reported by police trainers in in-depth interviews about the importance of pedagogy in police training (Körner et al., 2019a). The 30 police trainers interviewed highlighted a lack of context specificity of content as a limitation of formal coaching courses.

The reported reasons for preferring specific sources provide an indication of what police trainers want in terms of the quality of the knowledge and how it is delivered. Specifically, this group of police trainers identified a need for knowledge that was credible, current and expanded their knowledge base. References to sources being preferred because they were grounded in reality (being reality-based) suggests the need of some police trainers for a practical focus to the delivery of knowledge, whether it is experiential or has credibility in that it is known to work in practice. Furthermore, many police trainers value the exchange of experiences, perspectives of colleagues and opportunities to directly ask questions afforded by the social interaction facilitated by some sources. The three main reasons for preferring certain knowledge sources all appear to point toward the accepted need of police trainers to acquire coaching solutions that tackle the specific issues of police trainers.

While the criteria of a source being high in quality and grounded in reality provide a functional reference point for what knowledge is needed and where to get it from, there is a problem attached to that argument. In the self-defence domain, a reference to reality has been identified as a major selling point for technical and tactical behaviour advocated by different self-defence systems (Staller, 2016). However, research indicates that the conception of what works in self-defence situations differs between individuals (Heil et al., 2017; Heil et al., 2019). This may provide a rationale for the reported need of coaches to acquire further knowledge about the criterion environment (“the reality”). However, if anecdotes of colleagues are used as a primary source for information about the criterion environment compared to relying on sound and rigorous analyses of operational situations (Staller M. and Körner, 2019b), police trainers perception of reality might not accurately reflect reality.

The surveyed police trainers predominately reported police-specific content knowledge, like tactics and techniques, as nearly twice as often as pedagogical knowledge compared to the topic of knowledge they last acquired that they found useful. The reported knowledge was predominantly acquired by accessing non-formal and informal learning settings. Specifically, the source for pedagogical knowledge were mainly informal learning settings, whereas domain-specific content knowledge was mainly acquired though non-formal learning settings. All knowledge topics could be applied in practice in nearly 80% of the cases. These findings show two things: First, police trainers mainly find and use context-specific content and pedagogical knowledge in non-formal and informal learnings settings compared to formal learning settings like formal coaching courses. Second, informal learning settings are the main sources for pedagogical knowledge, whereas non-formal learning settings are the primary source for domain-specific content knowledge. This adds to the current data from coaches’ preferred sources and topics, suggesting formal coaching courses may lack context specificity and as such direct applicability for police trainers.

The dominant difference between reports of police-specific content and pedagogical knowledge in the last meaningful learning experience indicates a shortfall of pedagogical knowledge compared to police-specific knowledge. This might explain a observed prevalence of out-dated pedagogical approaches in police training (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020; Cushion, 2022; Staller et al., 2021b). Recent studies advocate for strengthening the focus on pedagogical aspects of police training centred coach education (Staller and Zaiser, 2015; Staller MS. and Körner S, 2019a; Nota and Huhta, 2019; Cushion, 2020). Knowledge of pedagogy is considered an attribute of coaching excellence (Nash and Collins, 2006; Abraham and Collins, 2011), which is widely acknowledged by sport coaches (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). While some police trainers acknowledged the need for pedagogical knowledge, many more reported the need for police training specific content knowledge. Such views may reflect the “shadowy existence” the topic of pedagogy has in the German police training domain (Körner et al., 2019a; Staller M. and Körner, 2019b). While police training specific content (e.g., tactical behaviour and use of force) and “ologies” (e.g., psychology) are explicitly referenced in the official regulations about how police training coaches in Germany should be qualified for their work (PDV211, 2014), there is no direct mention of the need of pedagogical knowledge.

When asked about their last learning experience, police trainers reported that they primarily acquired pedagogical knowledge through self-directed informal learning settings. This further supports the notion that finding and tapping into the sources of such knowledge primarily rests in the hands of police trainers. This adds to evidence from interview data from police trainers reporting that the potential for pedagogy for police training has not been recognised comprehensively within policing (Körner et al., 2019a). As such, it may be fruitful to further strengthen and communicate the value of pedagogy for effective coaching in police training (Körner and Staller, 2018).

Need for Knowledge Structures for Reflection

The synthesis of the results indicate that police trainers are in need of knowledge structures that allow for reflection, especially when they come in contact with new information. The findings yield that police trainers prefer police-specific content knowledge more than pedagogical knowledge and draw mainly from informal learnings settings, especially from interactions and observations of other coaches. Also, related to their last meaningful learning experience, police trainers reported that other coaches and colleagues are a useful source and that pedagogical knowledge is primarily acquired through self-directed informal learning activities. Finally, the vast majority of recently acquired knowledge has been directly applied.

While these findings do not directly indicate a need of knowledge structures that allow for the filtering and reflection of new information, they may serve as an explanation for results reported in other studies (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021a; Staller et al., 2021b) indicating that police trainers use outdated pedagogical approaches and that declarative knowledge structures are missing allowing for a critical reflection of police training delivery (Körner and Staller, 2018; Staller et al., 2021a). In order to tackle out-dated pedagogical approaches, police trainers need to be aware of what approach they are using and what assumptions about learning governs their behaviour as a coach. They also need alternative approaches with the underlying knowledge of why a specific approach might be useful in a given situation. Acquiring this knowledge and being able to reflect on it seems hard to achieve through self-directed learning activities, which was predominately reported as the main source for pedagogical knowledge. Instead, it seems more likely that coaches stick to the pedagogical approach they know, which seems to be a traditional approach to learning (Birzer, 2003; Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021a; Staller et al., 2021b). This traditional model of police training heavily relies on a linear approach to training, with large amounts of repetitive practice of isolated skills, that are later put together in complex training scenarios. Without the knowledge structures about pedagogical approaches, and without guidance for what and where to look for new information, self-directed learning activities may become a self-reinforcing mechanism for traditional pedagogical approaches (Hoy and Murphy, 2001).

This potential lack of reflecting capacity also becomes problematic when police trainers draw knowledge from social interactions with peers and observation. The main purpose of the coaching environment is coaching the trainees—and not coach learning (Trudel et al., 2010; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). For coaches it is hard to know how appropriate or relevant information by other coaches is, particularly considering the differing needs of both coaches and participants and the differing contexts within which coaches coach (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). Just because a “successful” coach applies a specific method or uses a specific drill, does not necessarily mean that it will be appropriate or effective for another coach in another context (Abraham and Collins, 2011; Cushion et al., 2012). Likewise, this argument holds true for police training specific content, like technical or tactical behaviour. Just because on operator successfully applies a specific technique in a specific situation does not necessarily mean that the application of the same technique will be effective for another officer and/or in another situation (Staller and Körner, 2020). Moreover, there is evidence from the sport coaching domain that the social milieu of coaches encourages perceiving aspects of training as relevant that actually are not (Nelson et al., 2013), and that much of the coaching practice that coaches observe and discuss in the coaching environment is more influenced by tradition (Abraham et al., 2006; Lemyre et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2010) than the critical consideration of current research (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). The precedence of traditional knowledge has also been identified in observational studies of police training (Staller et al., 2021). In sum, even though when reflected against the current literature the coaches in the current study seem aware of what they need, it seems that they do not seek this in a sufficiently critical and reflective way and via the best routes.

In order to engage in meaningful discussion with other coaches and colleagues, a declarative knowledge base is needed to allow coaches to reflect new information against (Nash and Collins, 2006; Abraham and Collins, 2011; Staller et al., 2020). However, the current results indicate that newly acquired knowledge is directly applied, suggesting that the knowledge has been critically reflected upon before application or that it has been uncritically applied. In the case of an uncritical application of newly acquired knowledge this would suggest that many participants may lack an overall knowledge structure against which they can compare, contrast, and reflect new knowledge against. Evidence from recent studies investigating the planning, delivery and reflection of police training (Cushion, 2020; Staller et al., 2021a; Staller et al., 2021b) indicate that this might be the case. The lack of declarative knowledge has been pointed out as problematic in sport (Martindale and Collins, 2013; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2014; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015) and martial arts domains (Staller et al., 2020). The need for such knowledge structures, providing clear and justifiable criteria against which questions, practice, habits, standards, values and beliefs can be reflected against have been continuously highlighted as being important with regards to coaching practice (Gilbert and Trudel, 2001; Abraham et al., 2006; Abraham and Collins, 2011). As such, without these structures, there is potential for police training coaches (a) to uncritically adopt information from the dominant culture, especially if the main source of learning is another coach or someone who is perceived as an expert without necessarily being one (Staller and Koerner, 2021), and (b) to incorporate information through self-directed learning settings without appropriate filters. Strengthening the acquisition of declarative knowledge structures within police trainers would prevent the implementation of potentially undesired, ineffective and/or dangerous practices that are otherwise simply being accepted at face value (Rynne and Mallett, 2014).

Furthermore, the need for knowledge structures for reflection also concerns the choice of where police trainers look for new information and knowledge. When asked to identify the source of the last thing learned that they found useful, it is notably that a portion of the CPD activities from which knowledge was drawn were privately attended seminars, workshops or courses. This adds to findings indicating that police trainers do what they do because they like it and are privately invested in it and as such are influenced by their personal background stories, especially with regards to martial arts or self-defence systems (Körner et al., 2019b). On the one hand, the finding might suggest that police trainers are highly engaged in their subject matter; however, on the other hand, it might suggest that there are perceived gaps in content and/or knowledge provided by police programmes that motivated trainers may be seeking out. Especially in the light of a lack of higher levels of reflection concerning the assumptions governing their behaviour this may become problematic. For example, communicative and de-escalative conflict resolution strategies in police training have been identified as blind spots in the delivery of police training (Rajakaruna et al., 2017; Staller, 2019; Staller et al., 2021b). As such, a police trainer who attends a physical combat and fighting workshop needs to be aware if the taught content is needed to become a better coach for. It may be advisable, that police trainers remain self-reflexive about that issue.

Practical Implications

The context a police trainer operates within may differ widely (Staller and Koerner, 2021) from teaching recruits at the academy over a period of time, to isolated CPD activities for officers, to the training of special operators. Each context differs with regards to the wants and needs of the learners, the curriculum, the learning environment and the organisational context. Police trainers seek out knowledge to tackle specific problems they face in their coaching practice. As such, coach education in police training needs to be mindful of who, what and how police trainers are required to coach in order to provide access to an appropriate suite of resources for support and coach development.

Second, police trainers have to be aware that coaching in the law enforcement domain is a pedagogical endeavour (Basham, 2014; Körner and Staller, 2018). The current data implies that police trainers want a better understanding of pedagogy. This is reassuring given that police training coaching is essentially a pedagogical endeavour. As such, it is important that nonformal coaching activities are built around pedagogical knowledge and are reflected upon from this perspective. A strong focus on pedagogical aspects in nonformal (and formal) learning settings, may result in pedagogical issues becoming the topic of informal activities as well. It is important to note that this does not call for downsizing the importance of police training specific content knowledge. However, valuing coaching as a decision-making process (Abraham and Collins, 2011) and as such a focus on knowledge structures allowing for the effective plan, implementation and review of police training sessions, may be beneficial for formal coach courses as well as for nonformal and informal learning situations. Thinking and reflecting tools such as the Coaching Practice Planning and Reflecting Framework (Muir et al., 2011; Muir et al., 2015) or reflective cards (Hughes et al., 2009) may help coaches with the demands of this ongoing, dynamic and adaptive process of coaching. Consequently, regulations about the qualifications and the development of police training coaches should acknowledge the importance of a sound pedagogical knowledge base; police training coach development courses should be designed to cover these aspects and facilitate the development of the needed knowledge structures.

Since social interactions with other trainers and colleagues and in self-directed learning settings seem to provide valuable context-specific knowledge for the police trainers, the need to be wary, critical and open minded to make the best use of these interactions. Preparing police trainers for continuously making the best out of informal and nonformal learning opportunities may be one of the main goals of formal coaching education in police training. In order to achieve this, formal coach education in police training has to be fundamentally changed. Stoszkowski and Collins (2015) suggest that a primary purpose of formal learning is to equip coaches with the knowledge structures that promote critical and reflective thinking in informal and nonformal learning settings. Coach learning “episodes” should be designed to expose and challenge pre-existing values and beliefs that coaches may have formed about a certain topic (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). Based on these experiences, context specific theoretical knowledge could be introduced to provoke, stimulate debate and to raise awareness of alternative and potentially more effective ideas about what to coach and/or how to coach it (Werthner and Trudel, 2006). Planned learning episodes used to check, re-visit and monitor the appropriateness of new beliefs and knowledge and regular interactions in the coaching context could then be interspersed and periodically implemented. This would allow coaches to move forward towards a more critical understanding of their thinking, reasoning and behaviour (Cushion et al., 2003; Abraham et al., 2010; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015), and reduce the copy and paste mentality of some coaches.

Limitations

There are limitations inherent to the survey approach employed by this study. Since police trainers answered the survey questions independently, there remains the potential for response biases due to participants’ interpretation of the questions (Evans and Mathur, 2005). Hence, future studies in police training could incorporate more interactive approaches (e.g., interviews) to further illicit how knowledge structures are developed in police training. Furthermore, participants in this survey were mainly recruited from three police agencies (Saxony, Hesse and Austria). Although no differences in patterns of responses were detected between the three main communities during the analysis, caution is warranted with regards to the generalisation of the results, especially if states fundamentally differ with regards to coach education in police training. Future studies should therefore incorporate other states and federal agencies as well.

Conclusion

The current study focused on coaching knowledge in police training. Specifically, it aimed at answering questions about (a) the types of knowledge they currently require and/or desire (the topics), (b) their actual and preferred methods of acquiring new coaching knowledge (the sources), and (c) how they apply the acquired knowledge (the applicability). Many of the police trainers surveyed indicated a need for knowledge about what to coach and the criterion environment, as well as pedagogical knowledge about how to coach. In light of the out-dated pedagogical approaches observed in police training (Cushion, 2020) and the lack of focus on pedagogy within coach education, the development of police trainers pedagogical knowledge should be prioritised. Finally, the findings show that nonformal and informal learnings settings are a prevalent and preferred source for police trainers to acquire new coaching knowledge. In order to make best use of these settings, police trainers need the declarative knowledge structures that allow them to be wary, open-minded and critically reflective about any new topic knowledge, received from any source, before it is applied to their coaching practice.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the current study and the final manuscript. The study was designed by MS and AA. Data was collected and analysed by MS. MS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. SK, AA, and JP provided substantial feedback to the manuscript and helped the manuscript to reach its final form.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham, A., Collins, D., and Martindale, R. (2006). The Coaching Schematic: Validation through Expert Coach Consensus. J. Sports Sci. 24 (06), 549–564. doi:10.1080/02640410500189173

Abraham, A., and Collins, D. (2011). “Effective Skill Development,” in Performance Psychology: A Practitioners Guide. Editors A. Button, and H. Richards (New York: Churchill Livingstone), 207–229. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-06734-1.00015-8

Abraham, A., Muir, B., and Morgan, G. (2010). UK Centre for Coaching Excellence Scoping Project Report: National and International Best Practice in Level 4 Coach Development. Leeds: Sports Coach UK, 1–96.

Birzer, M. L. (2003). The Theory of Andragogy Applied to Police Training. Policing 26 (1), 29–42. doi:10.1108/13639510310460288

Brady, A. (2006). “Opportunity Sampling,” in The Sage Dictionary of Social Research Methods. Editor V. Jupp (London: Sage), 205–206.

Cassidy, T., and Rossi, T. (2006). Situating Learning: (Re)examining the Notion of Apprenticeship in Coach Education. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 1 (3), 235–246. doi:10.1260/174795406778604591

Collins, A. M., Abraham, A., and Collins, R. (2012). On Vampires and Wolves - Exposing and Exploring Reasons for the Differential Impact of Coach Education. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 43, 255–271. doi:10.7352/ijsp.2012.43.255

Côté, J., Salmela, J. H., Baria, A., and Russell, S. J. (1993). Organizing and Interpreting Unstructured Qualitative Data. Sport Psychol. 7 (2), 127–137. doi:10.1123/tsp.7.2.127

Cushion, C., Ford, P. R., and Williams, A. M. (2012). Coach Behaviours and Practice Structures in Youth Soccer: Implications for talent Development. J. Sports Sci. 30 (15), 1631–1641. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.721930

Cushion, C. J., Armour, K. M., and Jones, R. L. (2003). Coach Education and Continuing Professional Development: Experience and Learning to Coach. Quest 55 (3), 215–230. doi:10.1080/00336297.2003.10491800

Cushion, C. J. (2022). Changing Police Personal Safety Training (PST) Using Scenario-Based-Training (SBT): A Critical Analysis of the ‘dilemmas of Practice’ Impacting Change. Front. Educ. 6, 796765. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.796765

Cushion, C. J., Nelson, L., Armour, K., Lyle, J., Jones, R., Sandford, R., et al. (2010). Coach Learning and Development: A Review of Literature. Sports Coach UK. Available at: https://www.sportscoachuk.org/sites/default/files/Coach-Learning-and-Dev-Review.pdf. (Accessed 06. 06. 2020)

Cushion, C. J. (2020). Exploring the Delivery of Officer Safety Training: A Case Study. Policing: J. Poli. Prac. Editors M. Meyer, and M. S. Staller 14, 166–180. doi:10.1093/police/pax095

Ellrich, K., and Baier, D. (2016). “6. Police Officers as Victims of Violence: Findings of a Germany-wide Survey,” in Representative Studies on Victimisation. Editors D. Baier, and C. Pfeiffer (Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG), 139–162. doi:10.5771/9783845273679-139

Erickson, K., Bruner, M. W., MacDonald, D. J., and Côté, J. (2008). Gaining Insight into Actual and Preferred Sources of Coaching Knowledge. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 3 (4), 527–538. doi:10.1260/174795408787186468

Evans, J. R., and Mathur, A. (2005). The Value of Online Surveys. Internet Res. 15 (2), 195–219. doi:10.1108/10662240510590360

Faulkner, G., and Biddle, S. (2002). Mental Health Nursing and the Promotion of Physical Activity. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 9 (6), 659–665. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2850.2002.00520.x

Gilbert, W. D., and Trudel, P. (2001). Learning to Coach through Experience: Reflection in Model Youth Sport Coaches. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 21, 16–34. doi:10.1123/jtpe.21.1.16

Grecic, D., and Collins, D. (2013). The Epistemological Chain: Practical Applications in Sports. Quest 65 (2), 151–168. doi:10.1080/00336297.2013.773525

Heil, V., Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2017). “Conceptions of Reality in Self-Defence Training: Impulses for Discussion,” in Conference ‘Martial Arts as a Challange for Inter- and Transdisciplinary Research, Ghent, Belgium (Lüneburg).

Heil, V., Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2019). “Konzeption von Realität im Selbstverteidigungstraining – Welche Parameter sind für Trainierende bedeutend? [Conception of reality in self-defence training - Which parameters are important for trainees?],” in Abstracts of the 7th Annual Conference of the Committee for Martial Arts Studies in the German Association of Sport “Experiencing, Training and Thinking the Body in Martial Arts and Martial Sports, Ghent, Belgium, November 15-17, 2018. Editor A Niehaus. J. Martial Arts Res.2, 16.

Hoy, A. W., and Murphy, P. K. (2001). “Teaching Educational Psychology to the Implicit Mind,” in Understanding and Teaching the Intuitive Mind. Editors B. Torff, and R.J. Sternberg (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 145–184.

Hughes, C., Lee, S., and Chesterfield, G. (2009). Innovation in Sports Coaching: the Implementation of Reflective Cards. Reflective Pract. 10 (3), 367–384. doi:10.1080/14623940903034895

Isaieva, I. (2018). Police Training in the System of Professional Training for Federal Police Force in Germany. Comp. Prof. Pedagogy 8 (4), 54–59. doi:10.2478/rpp-2018-0054

Jager, J., Klatt, T., and Bliesener, T. (2013). NRW-Studie: Gewalt gegen Polizeibeamtinnen und Polizeibeamte [North Rhine-Westphalian study: Violence against police officers]. Kiel: Christian‐Albrechts‐Universität zu Kiel.

Jones, R. L., Armour, K. M., and Potrac, P. (2010). Constructing Expert Knowledge: A Case Study of a Top-Level Professional Soccer Coach. Sport Educ. Soc. 8 (2), 213–229. doi:10.1080/13573320309254

Kelly, S., Thelwell, R., Barker, J. B., and Harwood, C. G. (2018). Psychological Support for Sport Coaches: an Exploration of Practitioner Psychologist Perspectives. J. Sports Sci. 36 (16), 1852–1859. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1423854

Körner, S., and Staller, M. S. (2018). From System to Pedagogy: Towards a Nonlinear Pedagogy of Self-Defense Training in the Police and the Civilian Domain. Secur J. 31 (2), 645–659. doi:10.1057/s41284-017-0122-1

Körner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, A. (2019a). “Pädagogik…, hat man oder hat man nicht…“ – Zur Rolle von Pädagogik im Einsatztraining der Polizei ["Pedagogy… did you or did you Not…" - The role of pedagogy in police training],” in “Lehren ist Lernen: Methoden, Inhalte und Rollenmodelle in der Didaktik des Kämpfens” : internationales Symposium; 8. Jahrestagung der dvs Kommission “Kampfkunst und Kampfsport” vom 3. - 5. Oktober 2019 an der Universität Vechta; Abstractband. Editors M. Meyer, and M.S. Staller (Hamburg: Deutsche Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaften dvs), 13–14.

Körner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, A. (2019b). “Weil mein Background da war …“ – Biographische Effekte bei Einsatztrainern*innen ["Because my background was… - Biographical effects for police trainers],” in “Lehren ist Lernen: Methoden, Inhalte und Rollenmodelle in der Didaktik des Kämpfens” : internationales Symposium; 8. Jahrestagung der dvs Kommission “Kampfkunst und Kampfsport” vom 3. - 5. Oktober 2019 an der Universität Vechta; Abstractband. Editors M. Meyer, and M.S. Staller (Vechta: Deutsche Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaften dvs), 17–18.

Lemyre, F., Trudel, P., and Durand-Bush, N. (2007). How Youth-Sport Coaches Learn to Coach. Sport Psychol. 21 (2), 191–209. doi:10.1123/tsp.21.2.191

Mallett, C. J., and Dickens, S. (2009). Authenticity in Formal Coach Education: Online Studies in Sports Coaching at the University of Queensland. Int. J. Coaching Sci. 3 (2), 79–90.

Mallett, C. J., Trudel, P., Lyle, J., and Rynne, S. B. (2009). Formal vs. Informal Coach Education. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 4 (3), 325–364. doi:10.1260/174795409789623883

Martindale, A., and Collins, D. (2013). The Development of Professional Judgment and Decision Making Expertise in Applied Sport Psychology. Sport Psychol. 27 (4), 390–399. doi:10.1123/tsp.27.4.390

Muir, B., Till, K., Abraham, A., Morgan, G., et al. (2015). “A Framework for Planning Your Practice: A Coach’s Perspective,” in The Science of Sport rugby. Editors K. Till, and B. Jones (Wiltshire: The Crowood Press), 161–175.

Muir, B., Morgan, G., Abraham, A., Morley, D., et al. (2011). “Developmentally Appropriate Approaches to Coaching Children,” in Coaching Children in Sport. Editor I. Stafford (New York: Routledge), 39–59.

Nash, C., and Collins, D. (2006). Tacit Knowledge in Expert Coaching: Science or Art? Quest 58 (4), 465–477. doi:10.1080/00336297.2006.10491894

Nelson, L., Cushion, C., and Potrac, P. (2013). Enhancing the Provision of Coach Education: the Recommendations of UK Coaching Practitioners. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 18 (2), 204–218. doi:10.1080/17408989.2011.649725

Nota, P. M., and Huhta, J. M. (2019). Complex Motor Learning and Police Training: Applied, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 10, 1797. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01797

PDV211 (2014). PDV 211: Schießtraining in der Aus- und Fortbildung - Ausgabe 2005 [PDV 211: Shooting training in basic and advanced training - 2005 edition]. Berlin: Innenminister Konferenz.

Rajakaruna, N., Henry, P. J., Cutler, A., and Fairman, G. (2017). Ensuring the Validity of Police Use of Force Training. Police Pract. Res. 18 (5), 507–521. doi:10.1080/15614263.2016.1268959

Renden, P. G., Savelsbergh, G. J. P., and Oudejans, R. R. D. (2016). Effects of Reflex-Based Self-Defence Training on Police Performance in Simulated High-Pressure Arrest Situations. Ergonomics 60 (5), 669–679. doi:10.1080/00140139.2016.1205222

Renden, P. G., Nieuwenhuys, A., Savelsbergh, G. J. P., and Oudejans, R. R. D. (2015). Dutch Police Officers' Preparation and Performance of Their Arrest and Self-Defence Skills: A Questionnaire Study. Appl. Ergon. Editors M. Meyer, and M. S. Staller 49, 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2015.01.002

Rynne, S. B., and Mallett, C. J. (2014). Coaches' Learning and Sustainability in High Performance Sport. Reflective Pract. 15 (1), 12–26. doi:10.1080/14623943.2013.868798

Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2019a). Commentary: Complex Motor Learning and Police Training: Applied, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 10, 2444. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02444

Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2019b). “Quo Vadis Einsatztraining? [Quo Vadis Police Training?],” in Die Zukunft der Polizeiarbeit - die Polizeiarbeit der Zukunft - Teil II. Rotenburg: Eigenverlag der Hochschule der Sächsischen Polizei (FH). Editor E. Kühne, 321–364.

Staller, M. S. (2019). “Mehr gelernt als geplant? Versteckte Lehrpläne im Einsatztraining [More learned Than planed? The hidden curriculum in police use of force training],” in Empirische Polizeiforschung XXII Demokratie und Menschenrechte - Herausforderungen für und an die polizeiliche Bildungsarbeit. Editors B. Frevel,, and P. Schmidt (Frankfurt: Verlag für Polizeiwissenschaft), 132–149.

Staller, M. S. (2016). “Selbstverteidigung in Deutschland – Eine empirische Studie zu trainingsdidaktischen Aspekten von 103 Selbstverteidigungssystemen [Self-defence in Germany - A empirical study of pedagogical aspects in 103 self-defence systems],” in Martial Arts Studies in Germany - Defining and Crossing Disciplinary Boundaries. Editor M.J. Meyer (Hamburg: Czwalina), 51–56.

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., Heil, V., Abraham, A., and Poolton, J. (2021a). The Planning and Reflection of Police Use of Force Training – A German Case Study. Security J. accepted. doi:10.13140/rg.2.2.27963.95528

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., Heil, V., Klemmer, I., Abraham, A., and Poolton, J. (2021b). The Structure and Delivery of Police Use of Force Training: A German Case Study. Eur. J. Secur Res. 1, 1–26. doi:10.1007/s41125-021-00073-5

Staller, M. S., Körner, S., and Abraham, A. (2020). Beyond Technique – the Limits of Books (And Online Videos) in Developing Self Defense Coaches’ Professional Judgement and Decision Making in the Context of Skill Development for Violent Encounters. Acta Periodica Duellatorum 8 (1), 1–16. doi:10.2478/apd-2020-000910.36950/apd-2020-009

Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2020). Komplexe Gewaltprävention: Zum Umgang mit Gewalt auf individueller Ebene [Complex Violence Prevention: Coping with Violence on an Individual Level]. Österreich Z. Soziol 45 (S1), 157–174. doi:10.1007/s11614-020-00413-0

Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2021). Regression, Progression and Renewal: The Continuous Redevelopment of Expertise in Police Use of Force Coaching. Eur. J. Secur Res. 6, 105–120. doi:10.1007/s41125-020-00069-7

Staller, M. S., and Zaiser, B. (2015). Developing Problem Solvers: New Perspectives on Pedagogical Practices in Police Use of Force Training. J. L. Enforcement 4 (3), 1–15.

Stoszkowski, J., and Collins, D. (2015). Sources, Topics and Use of Knowledge by Coaches. J. Sports Sci. 34 (9), 794–802. doi:10.1080/02640414.2015.1072279

Stoszkowski, J., and Collins, D. (2014). Communities of Practice, Social Learning and Networks: Exploiting the Social Side of Coach Development. Sport Educ. Soc. 19 (6), 773–788. doi:10.1080/13573322.2012.692671

Tracy, S. J., and Hinrichs, M. M. (2017). “Big Tent Criteria for Qualitative Research,” in The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods. Editors C.S. Davis, and R.F. Potter (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons).

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative Quality: Eight "Big-Tent" Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 16 (10), 837–851. doi:10.1177/1077800410383121

Trudel, P., Gilbert, W., and Werthner, P. (2010). “Coach Education Effectiveness,” in Sport Coaching: Professionalisation and Practice. Editors J. Lyle, and C. Cushion (London: Elsevier), 135–152.

Werthner, P., and Trudel, P. (2006). A New Theoretical Perspective for Understanding How Coaches Learn to Coach. Sport Psychol. 20 (2), 198–212. doi:10.1123/tsp.20.2.198

Keywords: police training, coaching knowledge, coach learning, coach development, police conflict management training

Citation: Staller MS, Koerner S, Abraham A and Poolton JM (2022) Topics, Sources and Applicability of Coaching Knowledge in Police Training. Front. Educ. 7:730791. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.730791

Received: 25 June 2021; Accepted: 14 January 2022;

Published: 10 February 2022.

Edited by:

Konstantinos Papazoglou, Pro Wellness Inc., CanadaReviewed by:

Nashwa Ismail, Durham University, United KingdomSimon Baldwin, Carleton University, Canada

Copyright © 2022 Staller, Koerner, Abraham and Poolton. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mario S. Staller, bWFyaW8uc3RhbGxlckBoc3B2Lm5ydy5kZQ==

Mario S. Staller

Mario S. Staller Swen Koerner

Swen Koerner Andrew Abraham

Andrew Abraham Jamie M. Poolton

Jamie M. Poolton