- 1Department of Police, University of Applied Sciences for Police and Public Administration in North Rhine-Westphalia, Aachen, Germany

- 2Department for Training Pedagogy and Martial Research, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany

For professional policing, learning is key. Since learning can be viewed as a complex process between the individual and information, learning takes place both within and outside the police system as well as during and before employment. The current conceptual analysis delineates different areas of (non-)learning related to policing and argues for the management of learning as a key issue for the police’s professionalization. According to this assumption a Police Learning Management Framework is presented, in which the relevant areas of learning as well as the related challenges for police learning on an individual and organizational level are specified. The proposed model calls for a more focused view on police learning which is a prerequisite for professionally coping with the pressing challenges of contemporary policing.

Introduction

A high quality of police work is essential in a socially fair and democratic society. Especially since the police are mandated with legally using coercive means to uphold the law (Terrill, 2014; Dunham and Alpert, 2021), it is essential that the delegated power is exercised professionally by the individual officer. While democracy does not guarantee that the judgments of the individual police officer will uniformly replicate those of the public, the public has a right to spell out the criteria by which the judgment should be made (Reiman, 1985). This social contract also entails that these criteria are adhered to by competent individuals. As such, ensuring that only competent individuals are tasked with making sound judgments is part of this social contract between the police and the public. To ensure good policing, police institutions invest resources to select both sufficient and qualified police officer candidates usually by using psychological selection procedures and optimally preparing the individuals on the front through education and training for their duties (Yuille, 1986; Feltes, 2002; Cordner and Shain, 2011; Donohue, 2020).

However, analysis of violations of this social contract, such as the inappropriate use of force (Boxer et al., 2021), racially and socially biased policing (Engel and Cohen, 2014; Abdul-Rahman et al., 2020), and police misconduct (Ivkovic, 2014; Porter, 2021), suggest that the genesis of such events is multi-faceted and cannot only be attributed to the individual’s behavior. While personal characteristics may play a role, training experiences, education, socialization, and other influences weigh into the performance in any given situation (Goff and Rau, 2020; Boxer et al., 2021).

Concerning professional conduct, there are a plethora of factors contributing to the competence of quality policing. While expertise might be an essential ingredient for professional police conduct, it is the result of a continuous development of the individual that has to be regularly renewed (Staller and Körner, 2021). It is noteworthy that this development extends beyond experiences in the police domain. Human development is a continuous, never-ending process that is dependent on various contexts and interactions within these contexts leading to individual experiences (Huston and Bentley, 2010; Osher et al., 2018).

We refer to this change in the individual’s system state and capacity due to interaction with the environment as learning. More specifically, learning occurs as an adaptation to regularities in the environment (Houwer et al., 2013). As such, our conceptualization of learning extends to what is—depending on the literature—referred to as training and/or education in organizational contexts. While training in an organization refers to a systematic approach to learning to improve individual, leading to the acquisition of new knowledge or skills (Aguinis and Kraiger, 2009), education encompasses, among other things, taking a reflexive stance toward one role. As such, police education reflects on the intentional, guided, and goal-directed development of police work, the police organization, and police governance (Huisjes et al., 2018). This reflexivity has been described as a key component of good policing (Bergman, 2017; Wood and Williams, 2017), resulting in a shift from only practical vocational training toward hybrid-formats of higher education programs in preparation for police work that has taken place over the last decades in several countries (Paterson, 2011; Frevel, 2018).

Ultimately, police officers have to perform their duties aligned with the goals of society. In order to do that, they have to arrive at an internal capacity, with the skills, knowledge, attitudes, belief system, etc., that allow them to professionally perform that duty. Society, and police organizations as part of it, have to ensure that, when individuals perform that societal task of policing, they have learnt what is needed. By referring to our broad understanding of learning we do not point toward a specific setting where such learning has occurred. Instead, we contend that police officers have been and are subject to various interactional contexts, where learning has the potential to occur and to ultimately unfold its impact when performing their daily duty.

In the current article, we analytically describe several areas where learning does take place—or non-learning understood as the negative value of learning: no adaptation on a certain (normatively set) aspect (e.g., learning to police) despite experiences within the environment. Of course, it can be argued which aspect should normatively be learnt. As such, non-learning is an observation depending on the perspective of the observer, based on the assumption that learning is always taking place (see section “Learning as an interaction process between individual and information”). Building on a systemic view on the area of learning, we selectively focus on five areas of (non-)learning that seem to play a key role in police learning. These areas comprise of what police officers have (or have not) learnt (1) before the job, (2) in preparation for their job, (3) during their job, (4) alongside their job, and (5) by being part of (sub-)system(s) of police. Having a clear concept of what is learnt, where, and when allows the police to (re)direct resources to the learning situations needed for optimal job performance. We finally state three challenges that future scholarly and practical endeavors have to address to further professionalize police learning. Before we start our analytical account of police learning we feel we should present our two general assumptions to the reader that guide our selection, description, and practical implication of our account of police learning.

Assumptions

The management of police-citizen interaction and the mandate to use coercion as key features of policing

The police profession has two structural features that distinguish it from other professions: (a) the mandate to legitimately use coercion and (b) a high potential for experiencing conflict situations during police-citizen interactions that have to be resolved on a continuum ranging from empathy and cooperation to means of coercion.

Both features stem from the inherent assignment of the police: providing safety for its citizen and ensuring that the law is adhered to. Through preventive and repressive measures, the police try to accommodate its mandate. Experiencing that prevention through repression is rather ineffective (Feltes, 2002); police services around the world have adhered more and more to a community-oriented approach of policing over the last decades including “order maintenance, conflict resolution, problem solving, and provision of services as well as other activities” (Feltes, 2002, p. 48). This proactive approach entails managing conflicts when they arise, soundly intervening when they have manifested, and simultaneously enforcing the legislation as mandated. The management of tension and conflict—be it verbal or physical—is structurally embedded in the policing mandate. However, given the social contract it is important to note that this must be achieved in forms best for the society (Reiman, 1985).

Since not all conflictual situations can be solved by cooperative means and violent acts of individuals have to be responded to, the police are mandated to use coercion and force legitimately (Terrill, 2014; Dunham and Alpert, 2021). The police are even allowed to use deadly force within the limits of the law (Terrill, 2016; Lee, 2017). This power comes with great responsibility: there is the danger the social contract will be violated; that police behavior harms the public more than it helps and serves.

These two distinguished features of the police profession create a field of tension: a high probability of experiencing conflict situations on a daily basis and the legal mandate to use coercion. While many conflict situations may be resolved using cooperative means, the use of coercion seems to provide an appealing shortcut (Staller and Koerner, 2021b). As such, it falls at the discretion of the acting police officer to make a sound judgment in which conflict resolution strategy might be appropriate in any given situation.

The decision of what strategy to employ and how to apply it is highly dependent on the stable and acute factors of the individual: their attitude, belief set, skills, physical characteristics, emotional state, etc. In short, it depends highly on the individual and the current internal system state. And this is—alongside situational factors involved (Cojean et al., 2020)—heavily the result of what the individual acting police officer has explicitly and implicitly learnt so far.

Learning as an interaction process between individual and information

In our account we adopt the broad definition of learning. We account for learning as interaction processes between individuals and information leading to permanent changes in the individual system’s capacity. Information potentially to be acted upon is omnipresent: experiences, learning material, thoughts, something we hear, something we see, or something that happens to us. As such, as soon as we interact with our physical or social environment, or with stored or generated information in our minds, we learn. This understanding of learning entails—but does not limit learning to—the mental processes that take place in the individual and that can lead to intended and unintended changes in emotion, cognition, and behavior. Traditionally, and more narrowly, learning in educational and training settings is concerned with the intended changes, also referred to as the learning outcomes (Illeris, 2007). With our broad definition we adopt a constructivist view to learning that is more equivalent to the definition of Illeris (2007) who defines learning as “any process that in living organisms leads to permanent capacity change and which is not solely due to biological maturation or aging” (p. 3). Adopting such a constructivist conceptualization has major consequences, especially concerning learning to police. These premises form the basis of our account:

• Premise 1: Learning is a continuous, always-happening process.

• Premise 2: Learning is not fully controllable.

• Premise 3: Learning is done by the individual.

In this constructivist approach (1), learning is more than just engaging in explicit learning settings such as school education or police training. Vast amounts of research show that learning takes place in formal settings, but also in informal environments such as peer talks or media (Hoy and Murphy, 2001; Ichijo and Nonaka, 2007). This directly refers to premise (2). If, when, and to what extent learning occurs eludes external control. While external information the individual acts upon can be influenced, for example, through the presentation of knowledge, setting up learning experiences, managing with what and who individuals engage with, etc., the effects—namely what is learned through these interactions—remains vague. Also, interactions the learning individual will have with material, thoughts, or people are often beyond the control of external influences and remain at the discretion of the individual, which points to premise (3). Ultimately, learning is done by the individual. It is a highly individualized and constructivist process.

This view on learning is in accordance with key assumptions of ecological dynamics, within that process, individual, task, and environmental constraints provide individual affordances and opportunities for learning which allow them to attune to information and to specify and guide their learning process (Seifert et al., 2019). As ecological psychology emphasizes the learning individuum attunes (consciously and subconsciously) to different sources of information to interact with, e.g., learning material, peer groups, social media, or their own thoughts (Wood and Williams, 2017; Staller et al., 2022b). Also, different intensity levels of interaction [e.g., (un-)conscious, (de-)motivated] are heavily dependent on the individual’s capacities and state at the moment of interaction (Vansteenkiste et al., 2004; Gorges and Kandler, 2012).

Furthermore, learning as a change in the individual’s system’s capacity posits that the starting point of any learning process is the current system state that is altered through interaction with information. As such, the starting point is always highly individual depending on different capacities and internal, e.g., emotional and motivational, states (Orth et al., 2019).

Finally, each interaction and the subsequent alteration in the individual’s system’s state provides an opportunity to interact with by itself. Using those experiences to learn from is at the heart of experiential and reflexive learning theories (Schön, 1983; Brookfield, 1998; Kolb, 2015).

Learning to police with democratic ideals

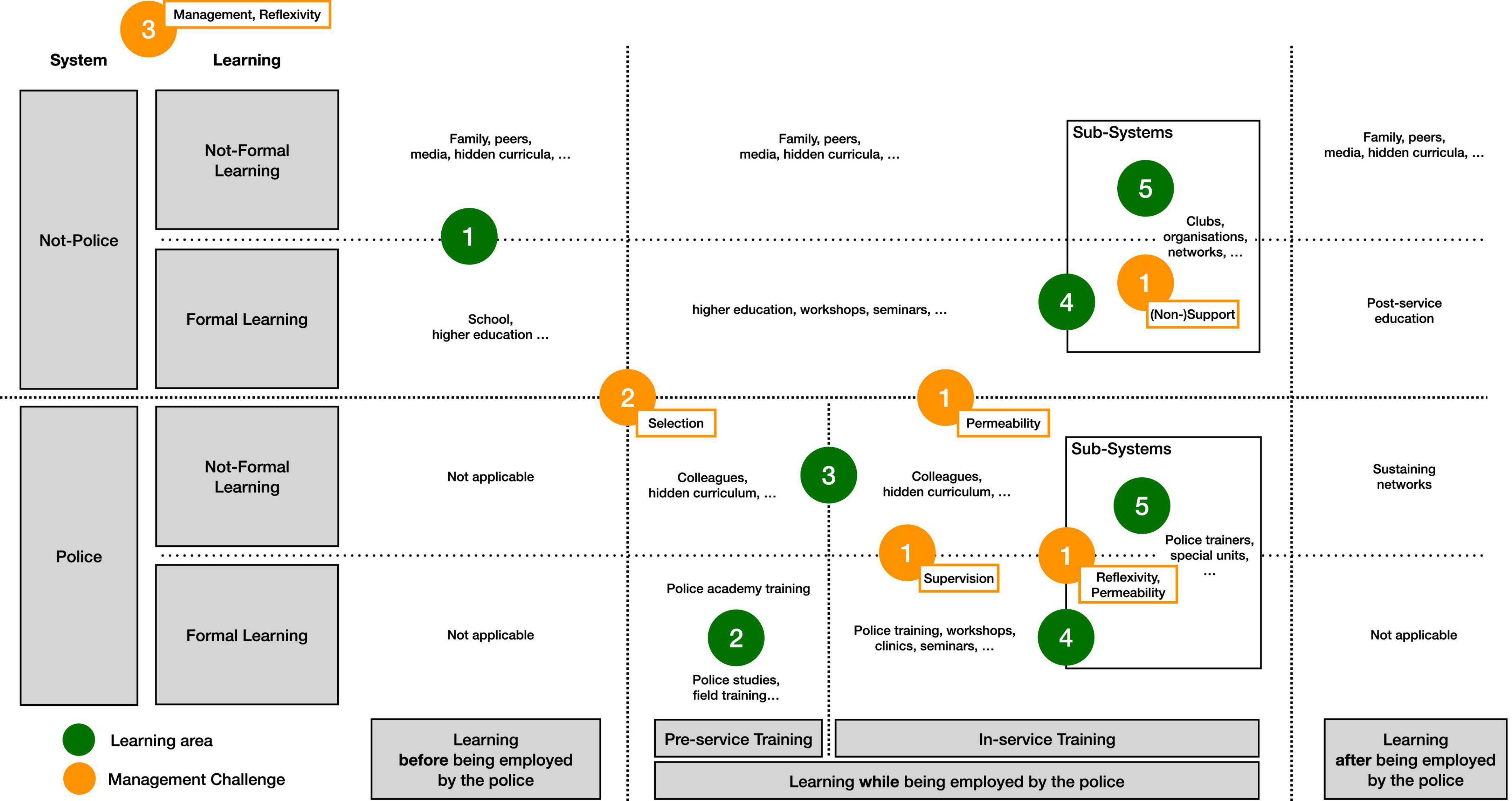

Based on our identified key aspects, that (a) high-quality policing is heavily dependent on the individual’s capacity to responsibly use the mandated power and that (b) learning extends beyond training and educational settings, we propose a framework for police learning. The framework aims at systematizing different areas where learning for policing takes place and that have to be accounted for—and thus be managed—by the police in order to ensure high-quality policing by the individual officers (see Figure 1). Within the framework we differentiate police (non-)learning on three dimensions: (a) in and outside the police (gray blocks on the left), (b) formal and not-formal learning (second columns of gray blocks on the left), and (c) the time-line centering on the employment status by the police institution (gray blocks on the bottom).

We purposely chose these three differentiations since they demark different systems (police vs. not-police, formal vs. not-formal learning, and timeline) with different internal system logics. Police and not-police refers to learning within the system of policing or not. We refer to formal learning as highly institutionalized settings that are formally recognized with diplomas and certificates and other organized learning opportunities. We refer to not-formal learning as any other learning taking place such as self-driven searches for knowledge and non-intended implicit learning through any other interaction between the individual and the environment. We are fully aware that there are other conceptualizations of formal and other forms of learning (Eraut, 2000; Nelson et al., 2006; Mallett and Dickens, 2009; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015). However, for our argument, the differentiation between what is institutionalized and intended (=formal learning) versus what is not (=not-formal learning) seems to us as a pragmatic differentiation. Concerning the timeline, we differentiate between not being employed by the police versus being employed by the organization. Additionally, we differentiate between pre-service training and in-service training, since the formal learning settings are different in nature between these two training and educational settings. The dotted lines depict system barriers between one system and another.

Based on our analytical approach, we now focus on five areas of learning (green circles) that, from our perspective, are essential to be considered when managing learning in policing and that provide various contemporary challenges. After describing the areas of learning and providing an overview of aspects to consider, we point toward the challenges (yellow circles) that from our perspective need to be addressed in order to further professionalize police training and education.

Learning before the job

Individuals have learnt a lot before becoming police officers. Before they enter the system of policing, individuals have learnt in different learning environments (Illeris, 2007): in school, college. Or universities, but also through media, family, peers, and other everyday learning interactions.

As such, individuals already have an individually learned conception about policing and underlying democratic ideals. A study from Germany showed that police recruits at the beginning of their career lie in the typical range for xenophobic attitudes compared to their education and age group (Krott et al., 2018). With what individuals have learnt before the doorstep of their police career is embedded within the societal context, like all learning (Illeris, 2007). This also extends to the current debates about the role and the orientation of policing (Jacobs et al., 2020; Goff, 2021; Koziarski and Huey, 2021; Staller and Koerner, 2021a). Individuals may have developed their individual conception about policing in society: What it entails, how it is embedded within the society, and what its main functions are. Depending on such conceptions individuals will enter to the profession with different premises and expectations. Is policing primarily understood as a public service or is it primarily a crime-fighting endeavor?

The conception about what the police profession is about may be influenced by experiences of the police as addressee or as a family member of a police family (Navarro-Abal et al., 2020)—but also in pop culture (Pautz, 2016; Seeßlen, 2019; Wilson et al., 2019) or police recruitment videos (Koslicki, 2020; Carrier et al., 2021). These conceptions are problematic if they do not match with what the profession is about or what the individual has to expect. For example, depictions and prominence of community-policing versus militaristic themes in videos may suggest a specific understanding of what policing is about (Koslicki, 2020).

Concerning the mandate to use legitimate coercive force, individuals may also bring an understanding of this responsibility to the table. This understanding may differ between the mandate embedded within the social contract and a given authority as an end to itself. For example, for some police recruits to be perceived as an authority seems a motivating factor (Muhadjeri, 2021). While this factor is regularly on the lower end of motives for becoming a police officer, the excitement of work, helping others, fighting crime, and the desire to enforce the law regularly score higher in self-reported motivational studies (Raganella and White, 2004; Wu et al., 2008; White et al., 2010; Lohbeck, 2021).

Besides learning that has taken place regarding the understanding, expectation, and attitude toward policing and its democratic foundation, individuals also have learnt a lot concerning practical conflict management skills: Through the rise of martial arts and reality-based self-defense systems (Bowman, 2015; Staller et al., 2016), individuals often enter the police service with a background of martial arts (Renden et al., 2015; Körner et al., 2019). A study investigating the effect of martial arts training on solving conflictual situations “hands-on” (Torres, 2018) indicated that prior experience in marital arts training and high perceived use of force self-efficacy predict confidence in resolving conflict physically. On the other side of conflict resolution skills, lots of learning opportunities in cooperative conflict resolution may lead to a learned skill set that emphasizes cooperation over coercion. However, to our knowledge no studies exist examining this linkage with regards to police conflict management. There are indications that individuals that learnt to cope with conflict in ways other than coercion yield these skills in conflict situations during police work (Jaeckle et al., 2019; Ba et al., 2021).

The argument is simple: Individuals are likely to perform what they have learnt, at least when they do not engage in a reflexive account of their learning process. For example, while there is nothing wrong with engaging in martial arts, it is about acknowledging that there may be a blind spot when it comes to conflict management. The argument also extends to biases and fallacies in general. Without reflexivity, individuals may have learnt things that may prove problematic combined with the mandated authority of police (Staller et al., 2022b). The benefit of higher order thinking skills—like reflexivity—may be a reason for results indicating that officers with a pre-service bachelor’s degree hold attitudes that are less supportive of abuse of authority (Telep, 2011).

In sum, people have a lot of learning opportunities before they arrive at the doorstep of policing. These depend on the societal constraints the individual is subjected to Illeris (2007). The more learning opportunities that relate to responsible conduct, sound police-citizen interactions, and conflict management, the more likely that these learnt beliefs and skills are put into the field.

Learning for the job

Training and education of police officers is essential factor for ensuring a high quality of police work (Feltes, 2002). Given that individuals—now police recruits—arrive with differing capacities of learnt content, the police have to ensure that individuals learn what is necessary for the police profession. However, since learning is ultimately not controllable and done by the individuals, the police organization is responsible for providing the grounds and the constraints in which learning is facilitated.

In order to prepare for the job, police recruit programs around the world regularly entail three planned learning settings: (a) theory informing class-room settings at the police academy, the police college, or the police university (Frevel, 2018; Leek, 2020); (b) practical skills training like conflict management training, traffic stop training, etc., (Staller et al., 2021a); and work-integrated learning through supervised and accompanied working in the field, otherwise known as field-training (Engelson, 1999; Hoel and Christensen, 2020).

Such planned learning settings provide the platform for what can be learnt; however, it is worth noting that what is indented to be learnt is not necessarily what is learnt. This issue refers to the difference between an explicit curriculum and a “hidden” one (White, 2006; Staller et al., 2019). For example, while the explicit curriculum in a Police University of Applied Sciences in Germany states that a community-oriented and de-escalative approach to policing is warranted, an analysis found that the vast amount of training content concerns coercive force (Staller et al., 2019, 2021a), providing the “hidden” learning message that conflictual situations are to be solved via coercion.

Concerning field training, explicit and implicit learning opportunities also differ: Engelson (1999) found that that although positive explicit values were communicated, several potentially negative implicit values were also communicated to police recruits (Engelson, 1999). Recruits learn more than what is explicitly addressed in field training. Learning within these settings also entails learning police misconduct (Getty et al., 2016). Field-training officers—like police trainers—are role models and peers and are of critical importance for police learning (Belur et al., 2019; Staller et al., 2022a). They can be a source of ethical practice but also of unethical practice (Fekjær et al., 2014; Hoel and Christensen, 2020). For example, the study on police students by Fekjær et al. (2014) showed that, during field training, police students changed their attitude to be more in line with negative characteristics of street cop culture. Police trainers also have the potential to influence the becoming of a police officer negatively. A reason for this might lie in the finding that recruits strive to be accepted; as such they focus on performing and learning what they observe through their field training officers (Hoel and Christensen, 2020). Danger narratives (Branch, 2021; Sierra-Arévalo, 2021) and storytelling (Kurtz and Upton, 2017; Rantatalo and Karp, 2018) implicitly convey a negatively biased perspective on the daily routine and problematic attitudes toward police-citizen interactions. On the positive side, field training officers and police trainers are of critical importance for police recruits in integrating theoretical learning with practical skills (Belur et al., 2019; Staller et al., 2022a). Also, field training officers’ professional and emotional support has been accounted for as an important feature by recruits (Hoel, 2019; Hoel and Christensen, 2020).

Also, studies in Germany regularly point toward differences between what is learnt in theory-driven academy settings compared to practical training and field training (Frevel, 2018). Frevel (2018) points out that some lecturers, trainers, and field trainers would disagree with the content taught by their respective partners. While the one side advises to “Forget everything you have learnt at the university, this is the real policing” (p. 209), the other side states “What you have learnt from your tutor is not state of the art and even wrong/illicit” (p. 209).

There is a broad consensus that police are in need of good education, leading toward an orientation toward higher education (Paterson, 2011; Frevel, 2018; Huisjes et al., 2018; Rogers and Frevel, 2018). Research has shown the beneficial aspects of this orientation, like a reduction in police culture (Cox and Kirby, 2018), a reduction in use of force (Rydberg and Terrill, 2010; Vespucci, 2020), or a reduction in xenophobic attitudes (Krott et al., 2018). Compared to a more practical-oriented approach to vocational training, higher educational settings focus on the development of broader skills sets such as such as emotional, cognitive, social and moral skills (Blumberg et al., 2019) as well as scientific thinking and reflective practice (Huisjes et al., 2018) in policing. Recently it has been argued that reflexivity is a key aspect in modern policing (Wood and Williams, 2017; Staller et al., 2022b), a metacognitive capacity and learning content especially prevalent in professional education (Schön, 1983). However, police recruits and officers sometimes wish for more hands-on practical skill experience, indicating a lack of perceived relevance to their daily work (Frevel, 2018; Edwards, 2019).

Learning on the job

When police officers enter their field, they are subjected to a lot of different experiences providing opportunities for (non-)learning. On the positive side, it is the diversity of the task that is regularly stated as one of the main reasons for becoming a police officer (Lohbeck, 2021; Muhadjeri, 2021). Negative accounts of the police job state the “shock of real-world experience” (Behr, 2006, 2017; Wang et al., 2020): the engagement with police-citizen interactions that are perceived as difficult, complex, and non-rewarding. Such interactions provide opportunities for a learning on-the-job situation: for example, the danger of manifesting stereotypes about social groups through cognitive biases when regularly occurring situations are not properly reflected upon has been regularly pointed out. On the other side, police-citizen interactions provide ample opportunities for reflection upon the experiences made, challenging one’s assumptions and optimizing interactional behaviors (Staller et al., 2021b). Reflexivity is the key prerequisite here (Wood and Williams, 2017).

As well as their own experiences, officers also learn from their peers (Doornbos et al., 2008): What they do, how they perceive and interpret situations, and—on an implicit level (see next section)—more general attitudes toward policing and reasoning structures. That learning takes place in everyday policing situations can be seen in results aiming at investigating used de-escalation strategies by officers (Bennell et al., 2021). Officers already learnt a lot before attending de-escalation workshops. Studies aiming at investigating what works in cooperative conflict management regularly tap into these learnt knowledge structures of police officers (Rajakaruna et al., 2017; Todak and White, 2019).

However, without underlying declarative knowledge structures it may be hard to determine what worked and why. Again, reflexivity provides a tool for making meaning—and seeing other perspectives—in police-citizen interactions. As such, supervision is regularly employed in domains that are characterized by power imbalances (Asakura and Maurer, 2018). Police frontline work benefits from this approach (Owens et al., 2018; Staller and Koerner, 2021c). For example, Owens et al. (2018) reported positive effects of police officers reflecting on the process of rather uncritical experiences of police-citizen interactions with supervisors modeling central components of procedural just behavior in these meetings.

There is a lot to learn from day-to-day job experiences (Schweer et al., 2008). However, without proper reflection, problematic lessons can be learnt from these events. Research on cognitive biases and fallacies indicates that no one is immune to drawing biased conclusions from experiences (Dror, 2020; Staller et al., 2021b).

Learning alongside the job

Learning alongside the job refers to all intended learning activities that are attended alongside daily work. While this entails continuous professional development (CPD) courses or training sessions on job-related issues (e.g., how to operate a certain system, conflict management training, etc.), learning alongside the job also takes place in privately attended learning settings, such as martial arts classes, reality-based combat training, or attending a university’s degree program.

CPD courses can equip police officers with new skills that may be needed due to a change in job demands. For example, a regular police officer may become a police trainer in the academy and may in preparation receive an extra training course for meeting the pedagogical challenges associated with the new role. Also, CPD courses may provide—or explicitly focus—on new perspectives regarding experiences had on duty. For example, implicit bias training and social interaction training may be a useful strategy to reduce inappropriate use of force on minority populations and coercive conflict management strategies with citizens in general. However, the results are mixed (Kahn and Martin, 2020; Wolfe et al., 2020), highlighting the potential without promising guaranteed effects. What is learned and what is not depends on a variety of factors, ranging from factors associated with the learners to those dependent on the trainer or coach. Therefore—in line with our initial assumptions—formal (non-)learning is a non-linear endeavor with the potential, not the promise, of learning.

From the perspective of the institution of police it is also worth considering which CPD activities are mandatory and which are not, which self-selected settings get supported and which do not. The latter aspect refers to formal settings that are attended alongside the police outside the police system. There are various providers for formal learning courses aimed at police officers. For example, concerning conflict management, firearms organizations, self-protection, and martial arts academies or networks fight for the limited resource of paying police officers.

Likewise, the higher education sector also offers (part-time) programs to working professionals that are attended voluntarily by motivated police officers (Lee and Punch, 2004). Several authors suggested the benefits of completing a higher education program alongside a job: police officers who engage in education beyond the remit of police training can “add value” to their organizations through the development of critical and wider reflective skills that are then transferable to policing settings (Lee and Punch, 2004; Jones, 2015). For example, attendees of a police studies program reported having developed a more reflexive conduct with members of the public (Jones, 2015), showcasing the adoption of new perspectives on specific police situations. This is a learning outcome that has regularly been described as essential in policing (Wood and Williams, 2017; Staller et al., 2022b).

Learning in closed systems

The police itself can be viewed as a social system: a plurality of social actors who are engaged in a more or less stable interaction according to shared cultural norms and meanings. With this perspective of analysis, research has continuously evidenced that the closeness of the system of policing contributes to another area of learning opportunities: learning from the system-embedded norms and values that are prevalent within the system of policing. Research on police culture shows that a lot is learnt from being a part of the system (Behr, 2006; Charman, 2017). For example, prevalent police narratives and the act of storytelling shape values, beliefs, and decision-making algorithms (Kurtz and Colburn, 2019). Implicit system knowledge is conveyed from one person to another. While, on the one hand, organizational socialization can contribute to imparting professional knowledge to new officers, including specific tactics for professional practice (Ford, 2003; van Hulst, 2013, 2017; Kurtz and Colburn, 2019), it can also manifest problematic values, beliefs, and practices (Branch, 2021).

Concerning the evaluation of such practices, the system’s perspective provides a relevant observation: while certain aspects are valued from outside the system as problematic, the within-system perspective yields them as the solution to presented problems. The difference in evaluation lies in the different system logics (Baechler, 2017). This is an aspect that is also learnt within the system.

The power of such system-implicit learning structures has regularly been described through the lenses of socialization: implicit learning within the system has a fundamental impact (Shernock, 1998). For example, a recent study found that personality traits change through socialization and identification within the police organization over 3 years (Alessandri et al., 2020).

The mechanisms through which learning occurs are manifold. Peer associations, reinforcement, and modeling have been described as effective learning opportunities within the system of policing (Chappell and Piquero, 2004; Chappell and Lanza-Kaduce, 2010). Also, storytelling (van Hulst, 2013; Smith et al., 2014; Schaefer and Tewksbury, 2017; Rantatalo and Karp, 2018) and the prevalence of specific narratives, such as the narrative of the police officer continuously being in danger (Woods, 2019; Branch, 2021; Sierra-Arévalo, 2021) or the police being society’s last line of defense against chaos (Wall, 2020), form continuous information flows that have the potential to transfer knowledge within an organization (Swap et al., 2015).

It is worth noting that the police service is not a homogeneous system. While there is indeed a common ground between all police organizational units based on the overall framework of policing, police culture within different functional units is different (Gutschmidt and Vera, 2020). As such, socialization within different sub-systems of the police, e.g., special forces, or police use of force training may vary, leading to distinct values, beliefs, and decision-algorithms that circulate in a self-referential loop. This in turn leads to a self-stabilizing system behavior. The more a system closes, the more self-referential it becomes. On a structural level, any changes to the system fail due to the lack of structural linkage to the outside system, e.g., non-special forces or non-use of force training. For example, data about the knowledge management of police use of force trainers showed that the main sources for “new” and valued knowledge stems from within the system, such as other trainers and workshops. While coaches in other domains beyond policing also value social interaction with peers as an area for knowledge generation (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2015), it becomes a problem if the system lacks a structural link to outside information. Concerning police conflict management, an analysis of the workshops and the members journal of an influential police trainer organization in Germany showed that police conflict management is heavily reduced to coercive force (Muhadjeri, 2021). This is a result that has recently also been evidenced in an analysis of police academy basic training curricula in the United States (Sloan and Paoline, 2021). The heavy imbalance toward coercive conflict management options as compared to more cooperative options gets stabilized within the system of police training: trainers seek to know more about these options, resulting in an implementation of these, which in turns creates the need to know more about it. As such, the knowledge of police officers—in this case trainers—forms the basis of the filter that new knowledge is selected through. This is a mechanism that has also been evidenced for knowledge in the context of police special forces (Koerner and Staller, 2021). The sub-system within the police system, e.g., police trainers or special forces, create their own system’s logic through which new information is evaluated, discarded, or selected, stabilizing the logic of the system.

Finally, distinct systems, e.g., martial arts clubs, training organizations, higher education settings, or participation in activist groups on social media, implicitly convey knowledge, beliefs, and values next to their external agenda. As such, these learning opportunities have the potential to be beneficial or problematic—depending on the perspective. For example, participants of a police studies program alongside their police work reported that the learning setting provided an opportunity for debate amongst officers, which contrasts experiences of hierarchical rank structures and associated obedience that are required of police officers (Jones, 2015). This exemplifies the different logics between system-based beliefs and values of hegemonic power structures, which have also been reported in other studies (Chappell and Lanza-Kaduce, 2010).

Challenges

So far, we have described the different areas of (non-)learning that contribute to what the individual police officer is able to perform. Based on this conceptual analysis, there are three distinct challenges that have to be addressed. These challenges arise from a systemic perspective on our analysis.

Systems tend to self-stabilize themselves. As such. the border between two systems is of special interest. How do the systems influence each other? How does what is learnt transfer from one system to the other? As such, the structural coupling of systems is of great importance. Social systems such as police and science have the potential to both irritate each other and to mutually provide information for each other to attune to. Such structurally coupled systems allow for a higher degree of internal complexity which in turn increases each system’s ability for future learning and performance.

We therefore focus on the different links between the systems: first, the challenge of overcoming non-permeable system barriers as it relates to knowledge management; and second, the transition of individuals between systems that specifically related to the selection of individuals that gain access to new (sub-)systems. Finally, we outline the challenge that this paper aims at providing a solution to: the management of learning in policing and how this can be achieved.

Challenge 1: Overcoming system barriers

The first challenge relates to the observation that police learning occurs in different systems, and that knowledge structures of one system do not necessarily transfer from one system to the other. As such, the challenge is to implement the mechanism that allows for the different systems to efficiently interact with each other and allow knowledge structures to pass system boarders. In this regard, systems theory proposes a way forward: systems have to structurally be coupled in order to achieve this. Various endeavors in the context of police learning have been deemed as promising (Henry, 2016; Baechler, 2017). For example, structural implemented cooperation between the police and universities via funded part-time higher education programs (Jones, 2015), the development of higher education routes into the system of policing (Martin and Wooff, 2018), or forming partnerships aimed at conducting research with the police (Goode and Lumsden, 2016) are all strategies that have been implemented before. However, it is essential that these structural couplings are functional as it relates to the knowledge transfer and ultimately what is learnt by of individuals within the organization. This is an aspect that cannot be taken for granted (Goode and Lumsden, 2016; Koerner and Staller, 2021).

The aspect of structural coupling also holds true for the sub-systems within the police, like police trainer networks or specialized units within the police system. Current evidence in the context of police conflict management training indicates dysfunctional or non-existing structural couplings between sub-systems and the police system as a whole. What is needed on duty does not reflect what is trained (Rajakaruna et al., 2017; Henriksen and Kruke, 2021; LaFrance, 2021; Staller et al., 2022a). A solution in this instance may lie in the structural coupling of a systematic mapping of demands on duty with the alignment and reevaluation of what is actually trained (Koerner and Staller, 2021). While science has mapped the deficit or challenge, practice still struggles to overcome this problem, indicating the challenge that has to be addressed.

Challenge 2: Selection for impact

Concerning knowledge management within systems, the permeability between different (sub-)systems is particularly important when knowledge structures of other systems are a needed resource within the system in focus. As such, in our framework the demarcation lines between different systems are of interest in so far as they present points of potential structural couplings between systems (challenge 1). The decision process of who to select for trespassing such system barriers—including what the individual has learnt so far—also has the potential to effectively function as a structural coupling between systems. These selection processes occur from the beginning of a policing career—as a transition from non-policing to policing—as well as within the system of policing, when individuals are selected for specialized tasks und professional roles, such as working as a police trainer, as a crisis negotiator, or a criminal investigator.

Since (non-)learning within (sub-)systems heavily occurs implicitly, it is essential for police organizations to select individuals for their learning impact on others: explicitly—if they are tasked with the conduct of formal learning settings such as police training—but also implicitly as they interact with colleagues regularly.

Concerning several pressuring issues, such as the structural inequalities in our societies, the inappropriate use of force toward minority populations (Boxer et al., 2021), the overreliance of use of coercive force trainings compared to cooperative conflict management training aiming at building cooperation and trust (Sloan and Paoline, 2021), the selection of who to allow access to (sub-)systems and unfold their impact is essential. Considering what an individual has learnt so far and what the individual is likely to contribute to the learning of others is key when selecting for impact. In a globalized and diverse world, where society is characterized by heterogeneity rather than homogeneity, selecting for different world views, experiences, and perspectives within the organization by selecting for difference rather than similarity is particularly important in systems that have a tendency to self-stabilize themselves through homogeneity.

Since selecting individuals are themselves part of the (sub-)system, it is likely that diversification is overseen based on one’s biases toward coherence rather than conflict (Simon et al., 2020). Overcoming this bias is not easy: it needs structurally implanted functional mechanisms (challenge 1). The last challenge to be addressed is reflexivity within the system.

Challenge 3: Enhancing reflexivity in learning to police

The last challenge concerns shifting the perspective of learning in the police toward a standpoint of a systemic view. This results in viewing (non-)learning in policing as a complex process that cannot be controlled in its entirety (premise 2)—but a process that has to be managed. Learning is contingent (Hager, 2012). The appearance of a stimulating learning situation is not predictable, nor what is learnt from it. However, being aware of and having insights into what accounts for learning situations and what can be learnt provide insights of the processes that represent control in contingent systems (Nassehi and Saake, 2002).

And in order to account for what and where can be learnt and is finally learnt, we need to take a step back and recalibrate our perspective from distinct learning settings and situations to seeing how we observe this specific learning setting and situation and what we omit by focusing on a specific aspect. This process of stepping back to observe what we observe is known as reflexivity. Reflexivity allows us to account for the hidden curriculum in formal learning settings that otherwise would remain unnoticed. By presenting our framework and laying out what can(not) be learnt in policing we allow for assessing potential blind-spots in police learning and allow for implementing strategies to manage police learning holistically.

As we have described throughout our paper, (a) various research endeavors have focused on shedding more light into learning processes in different systems related to police learning and (b) practical solutions have been implemented to enhance police (non-)learning in line with democratic ideals. By encouraging taking a reflexive stance toward police learning, we hope we can encourage further research endeavors and creative practical solutions to effectively manage the complexity of learning for policing.

Finally, the call for reflexivity extends beyond the system of policing to the individual police officer. Being aware of what has been learnt and where provides the first step towards uncovering one’s own assumptions and beliefs that may limit taking on other perspectives. Consequently, the challenge also extends to individuals through enhancing reflexivity in individual police officers. As such, learning in the police has to be coherently and constructively aligned to foster reflexivity in the individual police officer.

Conclusion

Learning can be viewed as an ongoing interaction between the individual and the environment, resulting in an experience-based permanent change of internal states and capacity that limit and enable how the individual perceives the world and (inter-)acts within. For the professional handling of the sovereign tasks assigned to police officers, they must learn what to do and how. At the same time, their task-related behavior in duty is yet an expression of what has already been learned.

According to this diagnosis, we have identified learning and its management as key issues for the further professionalization of police on an individual and organizational level, resulting in the proposal of a Police Learning Management Framework. Within this framework, learning before the job, for the job, on the job, alongside the job, and within closed systems in and outside of the police have been differentiated and weighted regarding their individual and organizational relevance in the light of current debates and empirical findings.

From the systematics thus obtained, challenges for a management of learning finally result, which we have specified in three directions.

• The first challenge is to systematically orient knowledge creation within the police toward external sources and partners and to enable the necessary organizational conditions for this.

• The second key challenge concerns the selection for and within the police service: for this, the management needs valid criteria that, depending on the task and activity, also demand and promote further requirements in addition to professional and ethical ones, e.g., a balanced pedagogical expertise of police trainers.

• The third challenge relates to a reflexive approach that goes hand in hand with the before mentioned challenges: a reflexivity built into the system of the police and its management of learning that makes it possible to constantly distance oneself from one’s own practices and structures and to question them with regard to their preconditions and intended as well as unintended consequences.

Taken together, a more focused view on police learning is a prerequisite for professionally coping with the pressing challenges policing faces today.

Author contributions

MS and SK contributed to the ideas presented. MS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Both authors contributed equally to editing the first draft to its final version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdul-Rahman, L., Grau, H. E., Klaus, L., and Singelnstein, T. (2020). Rassismus und Diskriminierungserfahrungen im Kontext polizeilicher Gewaltausübung. Zweiter Zwischenbericht zum Forschungsprojekt,,Körperverletzung im Amt durch Polizeibeamt*innen “(KviAPol) [Racism and Experiences of Discrimination in the Context of Police Violence. Second Interim Report on the Research Project “Assault in Office by Police Officers”]. Germany: Ruhr-Universität Bochum.

Aguinis, H., and Kraiger, K. (2009). Benefits of training and development for individuals and teams, organizations, and society. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60, 451–474. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163505

Alessandri, G., Perinelli, E., Robins, R. W., Vecchione, M., and Filosa, L. (2020). Personality trait change at work: associations with organizational socialization and identification. J. Pers. 88, 1217–1234. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12567

Asakura, K., and Maurer, K. (2018). Attending to social justice in clinical social work: supervision as a pedagogical space. Clin. Soc. Work J. 46, 289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10615-018-0667-4

Ba, B. A., Knox, D., Mummolo, J., and Rivera, R. (2021). The role of officer race and gender in police-civilian interactions in Chicago. Science 371, 696–702. doi: 10.1126/science.abd8694

Baechler, S. (2017). Do we need to know each other? bridging the gap between the university and the professional field. Policing: J. Policy Practice 13, 102–114. doi: 10.1093/police/pax091

Behr, R. (2006). Polizeikultur: Routinen - Rituale - Reflexionen [Police culture: routines - rituals - reflections]. Berlin: Springer, doi: 10.1007/978-3-531-90270-8

Behr, R. (2017). “Ich bin seit dreißig Jahren dabei“: relevanzebenen beruflicher identität in einer polizei am dem weg zur profession [“I’ve been on the job for thirty years”: relevant levels of professional identity in a police force on the way to professionalisation],” in Professionskulturen - Charakteristika Unterschiedlicher Professioneller Praxen, eds S. Müller-Hermann, R. Becker-Lenz, S. Busse, and G. Ehlert (Berlin: Springer Fachmedien), 31–62. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-19415-4_3

Belur, J., Agnew-Pauley, W., McGinley, B., and Tompson, L. (2019). A systematic review of police recruit training programmes. Policing: J. Policy Practice 39, 1–15. doi: 10.1093/police/paz022

Bennell, C., Alpert, G., Andersen, J. P., Arpaia, J., Huhta, J., Kahn, K. B., et al. (2021). Advancing police use of force research and practice: urgent issues and prospects. Legal Criminol. Psychol. 26, 121–144. doi: 10.1111/lcrp.12191

Bergman, B. (2017). Reflexivity in police education. Nordisk Politiforskning 4, 68–88. doi: 10.18261/issn.1894-8693-2017-01-06

Blumberg, D. M., Schlosser, M. D., Papazoglou, K., Creighton, S., and Kaye, C. C. (2019). New directions in police academy training: a call to action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:4941. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16244941

Bowman, P. (2015). Martial Arts Studies: Disrupting Disciplinary Boundaries. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Boxer, P., Brunson, R. K., Gaylord-Harden, N., Kahn, K., Patton, D. U., Richardson, J., et al. (2021). Addressing the inappropriate use of force by police in the United States and beyond: a behavioral and social science perspective. Aggress. Behav. 47, 502–512. doi: 10.1002/ab.21970

Branch, M. (2021). ‘The nature of the beast:’ the precariousness of police work. Policing Soc. 31, 982–996. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2020.1818747

Brookfield, S. D. (1998). Critically reflective practice. J. Continuing Educ. Health Prof. 18, 197–205. doi: 10.1002/chp.1340180402

Carrier, J., Bennell, C., Semple, T., and Jenkins, B. (2021). Online Canadian police recruitment videos: do they focus on factors that potential employees consider when making career decisions? Police Practice Res. 22, 1585–1602. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2020.1869549

Chappell, A. T., and Lanza-Kaduce, L. (2010). Police academy socialization: understanding the lessons learned in a paramilitary-bureaucratic organization. J. Contemporary Ethnography 39, 187–214. doi: 10.1177/0891241609342230

Chappell, A. T., and Piquero, A. R. (2004). Applying social learning theory to police misconduct. Deviant Behav. 25, 89–108. doi: 10.1080/01639620490251642

Charman, S. (2017). Police Socialisation, Identity and Culture: Becoming Blue. London: Palgrave macmillan.

Cojean, S., Combalbert, N., and Taillandier-Schmitt, A. (2020). Psychological and sociological factors influencing police officers’ decisions to use force: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 70:101569. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101569

Cordner, G., and Shain, C. (2011). The changing landscape of police education and training. Police Practice Res. 12, 281–285. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2011.587673

Cox, C., and Kirby, S. (2018). Can higher education reduce the negative consequences of police occupational culture amongst new recruits? Policing: Int. J. 41, 550–562. doi: 10.1108/pijpsm-10-2016-0154

Donohue, R. H. (2020). Shades of blue: a review of the hiring, recruitment, and selection of female and minority police officers*. Soc. Sci. J. 58, 484–498. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2019.05.011

Doornbos, A. J., Simons, R., and Denessen, E. (2008). Relations between characteristics of workplace practices and types of informal work-related learning: a survey study among Dutch Police. Hum. Resource Dev. Quarterly 19, 129–151. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1231

Dror, I. E. (2020). Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: six fallacies and the eight sources of bias. Anal. Chem. 92, 7998–8004. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00704

Dunham, R. G., and Alpert, G. P. (2021). “The foundation of the police role in society: important information to know during a police legitimacy crisis,” in Critical Issues in Policing, eds R. G. Dunham, G. P. Alpert, and K. D. McLean (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press).

Edwards, B. D. (2019). Perceived value of higher education among police officers: comparing county and municipal officers. J. Criminal Justice Educ. 30, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2019.1621360

Engel, R. S., and Cohen, D. M. (2014). “Racial profiling,” in The Oxford Handbook of Police and Policing, eds M. R. Reisig and R. J. Kane (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 383–408.

Engelson, W. (1999). The organizational values of law enforcement agencies: the impact of field training officers in the socialization of police recruits to law enforcement organizations. J. Police Criminal Psychol. 14, 11–19. doi: 10.1007/bf02830064

Eraut, M. (2000). Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 70, 113–136. doi: 10.1348/000709900158001

Fekjær, S. B., Petersson, O., and Thomassen, G. (2014). From legalist to dirty harry: police recruits’ attitudes towards non-legalistic police practice. Eur. J. Criminol. 11, 745–759. doi: 10.1177/1477370814525935

Feltes, T. (2002). Community-oriented policing in Germany: training and education. Policing: Int. J. Police Strategies Manag. 25, 48–59. doi: 10.1108/13639510210417890

Ford, R. E. (2003). Saying one thing, meaning another: the role of parables in police training. Police Quarterly 6, 84–110. doi: 10.1177/1098611102250903

Frevel, B. (2018). “Starting as a kommissar/inspector? - the state’s career system and higher education for police officers in Germany,” in Higher Education and Police, eds C. Rogers and B. Frevel (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 197–221.

Getty, R. M., Worrall, J. L., and Morris, R. G. (2016). How far from the tree does the apple fall? field training officers, their trainees, and allegations of misconduct. Crime Delinquency 62, 821–839. doi: 10.1177/0011128714545829

Goff, P. A. (2021). Asking the right questions about race and policing. Science 371, 677–678. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4518

Goff, P. A., and Rau, H. (2020). Predicting bad policing: theorizing burdensome and racially disparate policing through the lenses of social psychology and routine activities. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 687, 67–88. doi: 10.1177/0002716220901349

Goode, J., and Lumsden, K. (2016). The McDonaldisation of police-academic partnerships: organisational and cultural barriers encountered in moving from research on police to research with police. Policing Soc. 28, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2016.1147039

Gorges, J., and Kandler, C. (2012). Adults’ learning motivation: expectancy of success, value, and the role of affective memories. Learn. Individual Differ. 22, 610–617. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.09.016

Gutschmidt, D., and Vera, A. (2020). Dimensions of police culture - a quantitative analysis. Policing: Int. J. 43, 963–977. doi: 10.1108/pijpsm-06-2020-0089

Hager, P. J. (2012). “Formal learning,” in Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning, ed. N. M. Seel (Berlin: Springer), 1314–1316. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_160

Henriksen, S. V., and Kruke, B. I. (2021). Police basic firearms training: a decontextualised preparation for real-life armed confrontations. Policing Soc. 31, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2021.1877290

Henry, A. (2016). “Reflexive academic-practitioner collaboration with the police,” in Reflexivity and Criminal Justice, eds S. Armstrong, J. Blaustein, and A. Henry (Berlin: Springer), 169–190. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-54642-5_8

Hoel, L. (2019). ‘Police students’ experience of participation and relationship during in-field training’. Police Practice Res. 21, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2019.1664302

Hoel, L., and Christensen, E. (2020). In-field training in the police: learning in an ethical grey area? J. Workplace Learn. 32, 569–581. doi: 10.1108/jwl-04-2020-0060

Houwer, J. D., Barnes-Holmes, D., and Moors, A. (2013). What is learning? on the nature and merits of a functional definition of learning. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 20, 631–642. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0386-3

Hoy, A. W., and Murphy, P. K. (2001). “Teaching educational psychology to the implicit mind,” in Understanding and Teaching the Intuitive Mind, eds B. Torff and R. J. Sternberg (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum), 145–184.

Huisjes, H., Engbers, F., and Meurs, T. (2018). Higher education for police professionals. the dutch case. Policing: J. Policy Practice 14, 362–373. doi: 10.1093/police/pay089

Huston, A. C., and Bentley, A. C. (2010). Human development in societal context. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61, 411–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100442

Ichijo, K., and Nonaka, I. (eds) (2007). Knowledge Creation and Management: New Challenges for Managers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ivkovic, S. K. (2014). “Police misconduct,” in The Oxford Handbook of Police and Policing, eds M. D. Reisig and R. J. Kane (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 302–335.

Jacobs, L. A., Kim, M. E., Whitfield, D. L., Gartner, R. E., Panichelli, M., Kattari, S. K., et al. (2020). Defund the police: moving towards an anti-carceral social work. J. Prog. Hum. Services 32, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/10428232.2020.1852865

Jaeckle, T., Benoliel, B., and Nickel, O. (2019). “Police use of force decisions: a gender perspective,” in Walden University Research Symposium - 2019 Program & Posters, 23, (Minneapolis, MN). doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01817

Jones, M. (2015). Creating the ‘thinking police officer’: exploring motivations and professional impact of part-time higher education. Policing 10, 232–240. doi: 10.1093/police/pav039

Kahn, K. B., and Martin, K. D. (2020). The social psychology of racially biased policing: evidence-based policy responses. Policy Insights Behav. Brain Sci. 7, 107–114. doi: 10.1177/2372732220943639

Koerner, S., and Staller, M. S. (2021). From data to knowledge: training of police and military special operations forces in systemic perspective. Special Operat. J. 7, 29–42. doi: 10.1080/23296151.2021.1904571

Körner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, A. (2019). “Weil mein background da war. “- biographische effekte bei einsatztrainern*innen [“Because my background was. - Biographical effects for police trainers],” in Lehren ist Lernen: Methoden, Inhalte und Rollenmodelle in der Didaktik des Kämpfens”: internationales Symposium; 8. Jahrestagung der dvs Kommission “Kampfkunst und Kampfsport” vom 3. - 5. Oktober 2019 an der Universität Vechta; Abstractband, eds M. Meyer and M. S. Staller (Hamburg: Deutsche Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaften (dvs)), 17–18.

Koslicki, W. M. (2020). Recruiting warriors or guardians? a content analysis of police recruitment videos. Policing Soc. 36, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10439463.2020.1765778

Koziarski, J., and Huey, L. (2021). #Defund or #Re-Fund? re-examining Bayley’s blueprint for police reform. Int. J. Comparative Appl. Criminal Justice 45, 269–284. doi: 10.1080/01924036.2021.1907604

Krott, N. R., Krott, E., and Zeitner, I. (2018). Xenophobic attitudes in German police officers. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 20, 174–184. doi: 10.1177/1461355718788373

Kurtz, D. L., and Colburn, A. (2019). “Police narratives as allegories that shape police culture and behaviour,” in The Emerald Handbook of Narrative Criminology, eds J. Fleetwood, L. Presser, S. Sandberg, and T. Ugelvik (Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing).

Kurtz, D. L., and Upton, L. L. (2017). The gender in stories: how war stories and police narratives shape masculine police culture. Women Criminal Justice 28, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/08974454.2017.1294132

LaFrance, C. (2021). Improving mandatory firearms training for law enforcement: an autoethnographic analysis of illinois law enforcement training. J. Qual. Criminal Justice Criminol. 10, 1–23. doi: 10.21428/88de04a1.391b1386

Lee, C. (2017). Reforming the law on police use of deadly force: De-escalation, pre-seizure conduct, and imperfect self-defense. GWU law school public law research paper No. 2017-65. Available online at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3036934

Lee, M., and Punch, M. (2004). Policing by degrees: police officers’ experience of university education. Policing Soc. 14, 233–249. doi: 10.1080/1043946042000241820

Leek, A. F. (2020). Police forces as learning organisations: learning through apprenticeships. Higher Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn. 10, 741–750. doi: 10.1108/heswbl-05-2020-0104

Lohbeck, L. (2021). Berufswahlmotivation von Polizeibeamtinnen und -beamten (BEWAPOL). Entwicklung und Validierung eines Fragebogens zur Wahl des Polizeiberufs [Career Choice Motivation of Police Officers. Development and validation of a questionnaire on the choice of police profession]. Polizei Wissenschaft 2, 2–17.

Mallett, C. J., and Dickens, S. (2009). Authenticity in formal coach education: online studies in sports coaching at the University of Queensland. Int. J. Coaching Sci. 3, 79–90.

Martin, D., and Wooff, A. (2018). Treading the front-line: tartanization and police-academic partnerships. Policing: J. Policy Practice 14, 325–336. doi: 10.1093/police/pay065

Muhadjeri, B. (2021). Warum Werden wir Polizisten? Eine Analyse der Motivationen zur Berufswahl. Germany: Hochschule für Polizei und öffentliche Verwaltung Nordrhein-Westfalen. [Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis].

Nassehi, A., and Saake, I. (2002). Kontingenz: Methodisch verhindert oder beobachtet? [Contingency: Methodically prevented or observed?]. Zeitschrift Soziol. 31, 66–86.

Navarro-Abal, Y., López-López, M. J., Gómez-Salgado, J., and Climent-Rodríguez, J. A. (2020). Becoming a police officer: influential psychological factors. J. Invest. Psychol. Offender Prof. 17, 118–130. doi: 10.1002/jip.1544

Nelson, L. J., Cushion, C. J., and Potrac, P. (2006). Formal, nonformal and informal coach learning: a holistic conceptualisation. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coaching 1, 247–259. doi: 10.1260/174795406778604627

Orth, D., Kamp, J., and van der Button, C. (2019). Learning to be adaptive as a distributed process across the coach-athlete system: situating the coach in the constraints-led approach. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 24, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2018.1557132

Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., and Rose, T. (2018). Drivers of human development: how relationships and context shape learning and development1. Appl. Dev. Sci. 24, 1–31. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2017.1398650

Owens, E., Weisburd, D., Amendola, K. L., and Alpert, G. P. (2018). Can you build a better cop? Criminol. Public Policy 17, 41–87. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12337

Paterson, C. (2011). Adding value? a review of the international literature on the role of higher education in police training and education. Police Practice Res. 12, 286–297. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2011.563969

Pautz, M. C. (2016). Cops on film: hollywood’s depiction of law enforcement in popular films, 1984-2014. PS: Political Sci. Politics 49, 250–258. doi: 10.1017/s1049096516000159

Porter, L. E. (2021). “Police misconduct,” in Critical Issues in Policing, eds R. G. Dunham, G. P. Alpert, and K. D. McLean (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press).

Raganella, A. J., and White, M. D. (2004). Race, gender, and motivation for becoming a police officer: implications for building a representative police department. J. Criminal Justice 32, 501–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2004.08.009

Rajakaruna, N., Henry, P. J., Cutler, A., and Fairman, G. (2017). Ensuring the validity of police use of force training. Police Practice Res. 18, 507–521. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2016.1268959

Rantatalo, O., and Karp, S. (2018). Stories of policing: the role of storytelling in police students’ sensemaking of early work-based experiences. Vocat. Learn. 11, 161–177. doi: 10.1007/s12186-017-9184-9

Reiman, J. (1985). “The social contract and the police use of deadly force,” in Moral Issues in Policing, eds F. A. Ellison and M. Feldberg (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefeld), 237–349.

Renden, P. G., Landman, A., Savelsbergh, G. J. P., and Oudejans, R. R. D. (2015). Police arrest and self-defence skills: performance under anxiety of officers with and without additional experience in martial arts. Ergonomics 58, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2015.1013578

Rogers, C., and Frevel, B. (eds) (2018). Higher Education and Police, An International View. Berlin: Springer.

Rydberg, J., and Terrill, W. (2010). The effect of higher education on police behavior. Police Quarterly 13, 92–120. doi: 10.1177/1098611109357325

Schaefer, B. P., and Tewksbury, R. (2017). The tellability of police use-of-force: how police tell stories of critical incidents in different contexts. Br. J. Criminol. 58, 37–53. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azx006

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals think in Action. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Schweer, T., Strasser, H., and Zdun, S. (2008). Das da Draußen ist ein Zoo, und wir sind die Dompteure“, Polizisten im Konflikt mit ethnischen Minderheiten und sozialen Randgruppen [“It’s a zoo out there, and we’re the tamers,” police officers in conflict with ethnic minorities and marginalized social groups]. Berlin: Springer.

Seeßlen, G. (2019). Cops, bullen, flics, piedipiatti: polizist*innen in der populären kultur [Cops, Cops, Flics, Piedipiatti: policewomen in Popular Culture]. Aus Politik Und Zeitgeschichte 2, 49–53.

Seifert, L., Papet, V., Strafford, B. W., Coughlan, E. K., and Davids, K. (2019). Skill transfer, expertise and talent development: an ecological dynamics perspective. Movement Sport Sci. Motricité 19, 705–711. doi: 10.1051/sm/2019010

Shernock, S. K. (1998). The differential value of work experience versus pre-service education and training on criticality evaluations of police tasks and functions*. Justice Prof. 10, 379–405. doi: 10.1080/1478601x.1998.9959478

Sierra-Arévalo, M. (2021). American policing and the danger imperative. Law Soc. Rev. 55, 70–103. doi: 10.1111/lasr.12526

Simon, D., Ahn, M., Stenstrom, D. M., and Read, S. J. (2020). The adversarial mindset. Psychol. Public Policy Law 26, 353–377. doi: 10.1037/law0000226

Sloan, J. J., and Paoline, E. A. (2021). “They Need More Training!” a national level analysis of police academy basic training priorities. Police Quarterly. 24, 486–518.

Smith, R., Pedersen, S., and Burnett, S. (2014). Towards an organizational folklore of policing: the storied nature of policing and the police use of storytelling. Folklore 125, 218–237. doi: 10.1080/0015587x.2014.913853

Staller, M. S., Bertram, O., Althaus, P., Heil, V., and Klemmer, I. (2016). “Selbstverteidigung in deutschland - Eine empirische Studie zu trainingsdidaktischen Aspekten von 103 Selbstverteidigungssystemen [Self-defence in Germany - A empirical study of pedagogical aspects in 103 self-defence systems],” in Martial Arts Studies in Germany - Defining and Crossing Disciplinary Boundaries, ed. M. J. Meyer (Hamburg: Czwalina), 51–56.

Staller, M. S., and Koerner, S. (2021a). Evidence-based policing or reflexive policing: a commentary on Koziarski and Huey. Int. J. Comp. Appl. Criminal Justice 45, 423–426. doi: 10.1080/01924036.2021.1949619

Staller, M. S., and Koerner, S. (2021b). Polizeiliches Einsatztraining: was es ist und was es sein sollte [Police Training: What is is and what it should be]. Kriminalistik 75, 79–85.

Staller, M. S., and Koerner, S. (2021c). Die verantwortung des polizeilichen einsatztrainings: gesellschaftliche bilder und sprachgebrauch in der bildung von polizist_innen [The Responsibility of Police Training: Social Images and Language Use in the Education of Police Officers]. Sozial Extra 45, 361–366. doi: 10.1007/s12054-021-00418-3

Staller, M. S., and Körner, S. (2021). Regression, progression and renewal: the continuous redevelopment of expertise in police use of force coaching. Eur. J. Security Res. 6, 105–120. doi: 10.1007/s41125-020-00069-7

Staller, M. S., Körner, S., Heil, V., and Kecke, A. (2019). “Mehr gelernt als geplant? versteckte lehrpläne im einsatztraining [More learned than planned? The hidden curriculum in police use of force training],” in Empirische Polizeiforschung XXII Demokratie und Menschenrechte - Herausforderungen für und an die polizeiliche Bildungsarbeit, eds B. Frevel and P. Schmidt (Berlin: Springer), 132–149.

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., Heil, V., Klemmer, I., Abraham, A., and Poolton, J. (2021a). The structure and delivery of police use of force training: a german case study. Eur. J. Security Res. 1–26. doi: 10.1007/s41125-021-00073-5

Staller, M. S., Zaiser, B., and Koerner, S. (2021b). The problem of entanglement: biases and fallacies in police conflict management. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 24, 113–123. doi: 10.1177/14613557211064054

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., Heil, V., Abraham, A., and Poolton, J. (2022a). Police recruits’ wants and needs in police training in Germany. Security J. 1–23. doi: 10.1057/s41284-022-00338-1

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., and Zaiser, B. (2022b). “Der/die reflektierte Praktiker*in: reflektieren als polizist*in und einsatztrainer*in,” in Handbuch polizeiliches Einsatztraining, Professionelles Konfliktmanagement - Theorie, Trainingskonzepte und Praxiserfahrungen, eds M. S. Staller and S. Koerner (Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler), 41–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-34158-9_3

Stoszkowski, J., and Collins, D. J. (2015). Sources, topics and use of knowledge by coaches. J. Sports Sci. 34, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2015.1072279

Swap, W., Leonard, D., Shields, M., and Abrams, L. (2015). Using mentoring and storytelling to transfer knowledge in the workplace. J. Manag. Inform. Systems 18, 95–114. doi: 10.1080/07421222.2001.11045668

Telep, C. W. (2011). The impact of higher education on police officer attitudes toward abuse of authority. J. Criminal Justice Educ. 22, 392–419. doi: 10.1080/10511253.2010.519893

Terrill, W. (2014). “Police coercion,” in The Oxford Handbook of Police and Policing, eds M. D. Reisig and R. J. Kane (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 260–279.

Todak, N., and White, M. D. (2019). Expert officer perceptions of de-escalation in policing. Policing 36, 47–16. doi: 10.1108/pijpsm-12-2018-0185

Torres, J. (2018). Predicting law enforcement confidence in going ‘hands-on’: the impact of martial arts training, use-of-force self-efficacy, motivation, and apprehensiveness. Police Practice Res. 21, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/15614263.2018.1500285

van Hulst, M. (2013). Storytelling at the police station: the canteen culture revisited. Br. J. Criminol. 53, 624–642. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azt014

van Hulst, M. (2017). Backstage storytelling and leadership. Policing: J. Policy Practice 11, 356–368. doi: 10.1093/police/pax027

Vansteenkiste, M., Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K. M., and Deci, E. (2004). Motivating learning, performance, and persistence: the synergistic effects of intrinsic goal contents and autonomy-supportive contexts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 87, 246–260. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.2.246

Vespucci, J. (2020). Education Level and Police Use of Force, The Impact of a College Degree. Berlin: Springer, doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-42795-5

Wall, T. (2020). The police invention of humanity: notes on the “thin blue line.”. Crime Media Culture: Int. J. 16, 319–336. doi: 10.1177/1741659019873757

Wang, X., Qu, J., and Zhao, J. (2020). The link between police cadets’ field training and attitudes toward police work in China: a longitudinal study. Policing: Int. J. 43, 591–605. doi: 10.1108/pijpsm-01-2020-0014

White, D. (2006). A conceptual analysis of the hidden curriculum of police training in England and Wales. Policing Soc. 16, 386–404. doi: 10.1080/10439460600968164

White, M. D., Cooper, J. A., Saunders, J., and Raganella, A. J. (2010). Motivations for becoming a police officer: re-assessing officer attitudes and job satisfaction after six years on the street. J. Criminal Justice 38, 520–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.04.022

Wilson, F. T., Schaefer, B. P., Blackburn, A. G., and Henderson, H. (2019). Symbolically annihilating female police officer capabilities: cultivating gendered police use of force expectations? Women Criminal Justice 19, 1–20. doi: 10.1080/08974454.2019.1588837

Wolfe, S. E., Rojek, J., McLean, K., and Alpert, G. (2020). Social interaction training to reduce police use of force. Annals Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 687, 124–145. doi: 10.1177/0002716219887366

Wood, D. A., and Williams, E. (2017). “The politics of establishing reflexivity as a core component of good policing,” in Reflexivity and Criminal Justice: Intersections of Policy, Practice and Research, eds S. Armstrong, J. Blaustein, and A. Henry (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 215–236. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-54642-5_10

Woods, J. B. (2019). Policing, danger narratives, and routine traffic stops. Michigan Law Rev. 117, 635–712.

Wu, Y., Sun, I. Y., and Cretacci, M. A. (2008). A study of cadets’ motivation to become police officers in China. Int. J. Police Sci. Manag. 11, 377–392. doi: 10.1350/ijps.2009.11.3.142

Keywords: police learning, police professionalization, reflective policing, police systems, knowledge management

Citation: Staller MS and Koerner S (2022) (Non-)learning to police: A framework for understanding police learning. Front. Educ. 7:730789. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.730789

Received: 25 June 2021; Accepted: 04 August 2022;

Published: 26 September 2022.

Edited by:

Konstantinos Papazoglou, Pro Wellness Inc., CanadaReviewed by:

Stefano Zago, IRCCS Ca’ Granda Foundation Maggiore Policlinico Hospital, ItalyStefan Schade, Hochschule der Polizei Rheinland-Pfalz, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Staller and Koerner. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mario S. Staller, TWFyaW8uc3RhbGxlckBoc3B2Lm5ydy5kZQ==

Mario S. Staller

Mario S. Staller Swen Koerner2

Swen Koerner2