- Department of Psychology and Education, University of Neuchâtel, Neuchâtel, Switzerland

This paper focuses on the learning processes of students involved in a pedagogical design bridging in-class and out-of-class activities. As academic teachers–researchers, we designed a semester-long course in which academic and out-of-university activities interact and overlap. The data were collected at the end of the course from student reports (diaries) and audio-recorded semi-structured interviews inspired by the elicitation interview technique. This technique involves a fine-grained description of the lived experience. We present selected excerpts in which students described their boundary-crossing movements between academic and out-of-university activities. Data were evaluated using a purpose-built analysis approach comprising two macro-categories and three sub-categories of students’ boundary-crossing movements. The results showed that specific learning processes emerged and developed through these movements. Implications for teaching and learning are highlighted.

Introduction

In previous work that focused on the same pedagogical design described herein, we showed how both the sociomaterial characteristics of the contexts in which students acted and the situated nature of participant engagement contributed to the polyphony of students’ positioning with respect to their understanding of the learning aims (Cattaruzza et al., 2019b). In a complementary way, this paper focuses on boundary-crossing movements through the analysis of students’ verbal accounts of their participation in a pedagogical approach aimed at merging activities carried out in the classroom with those conducted outside the school.

Our pedagogical approach has been conceived as a hybrid learning course to support the students’ experience of being “in between several different sources of knowledge” (Gee, 2010). As teachers and researchers, we consider these kinds of situations as important cultural opportunities (Gutierrez et al., 1999) for developing a new kind of learning that effectively expand a school’s institutional boundaries (Yamazumi, 2008; Engeström, 2016, 2020). The basic assumption of our pedagogical challenge is that we can encourage students to experience an “in between” perspective which can help them “to see connections, as well as contradistinctions between the ways they know the world and the ways others know the world” (Moje et al., 2004, p. 44). This paper briefly introduces the notion of boundary-crossing, which is adopted in our approach.

Interaction as Unit of Analysis

Several studies have shown that an inter-contextual level of analysis can better capture the complexity and situatedness of psychological activity. These approaches consider this activity, and especially learning processes, as involving complex sequences that students realize as sets of physical and psychological actions in multiple social spaces (Perret-Clermont, 2004; Iannaccone and Zittoun, 2014). In particular, in the course of daily activities, students frequently cross the boundaries between contexts, with relevant consequences for data collection and analysis (Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström, 2003; Iannaccone, 2013). These characteristics require researchers both to take the movements between contexts seriously and to choose, as the unit of analysis, precisely the dynamics that characterize this inter-contextuality.

An interesting example of this type of methodological approach is represented by researchers’ criticisms of traditional research on family–school relations. In fact, a large part of classical research on family–school relationships has, for decades, collected the “individual” ethno-theories of parents and teachers (using questionnaires and/or interviews), and attempted to articulate, post hoc only, the multiple positions of teachers and parents. Using ethnographic observations of verbal interactions among parents, students, and teachers, Iannaccone and Marsico (2013) obtained results that clearly support the choice of conversational interaction as a non-decomposable unit of analysis. It is during these sometimes-conflictual conversations that those involved can better recognize each other’s point of view. In addition, this approach makes it possible to observe how, during interactions, the individuals negotiate their positions, frequently modifying their initial beliefs (Iannaccone and Marsico, 2013; Iannaccone and Arcidiacono, 2014; Cattaruzza et al., 2019a).

Movements Across Borders

Research focusing on the movements between contexts assumes as fundamental the notion of a “boundary zone” (Konkola, 2001). This is defined as the place where multiple human activity systems converge, each one reflecting its own structure, attitude, belief, norm, and role. This convergence creates the need for the actors involved to “tune” the different perspectives and to consider different points of view at the same time. In many cases, this seems to facilitate understanding of the situation.

The promotion of learning at the boundary zone has fostered the emergence of new kinds of pedagogical activities called “boundary-zone activities” (Konkola et al., 2007; Cattaruzza et al., 2019b). When considering the conditions under which continuities and discontinuities in learning across school and in out-of-school contexts occur, Bronkhorst and Akkerman (2016) highlighted “the complicated challenges schools face in connecting to out-of-school contexts” (p. 28). Connecting learning across school and in out-of-school contexts for understanding and supporting students’ learning is a growing topic in educational research and practice (Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström, 2003; Bronkhorst and Akkerman, 2016; Rajala et al., 2016).

In their review of boundary-crossing studies, Akkerman and Bakker (2011) showed how the multitude of “boundary” terms (boundary object, boundary zone, boundary crosser etc.) reflect various ways in which boundary-crossing can happen: “Boundaries can be crossed by people, by objects, and by interactions between actors of different practice” (p. 2). From that perspective, borders can present a real identity challenge for those who cross them or stay in the zone for a certain time. Crossing the borders requires, in many cases, a deep reworking of personal and social roles and skills. In these situations, the role of adults (e.g., teachers) in charge of managing a border zone can be crucial, especially when they have experience in: managing challenging situations, conflicts mediation, and creating open spaces for dialogue and joint work (Perret-Clermont, 2015). In this sense, the effectiveness of border spaces utilized for thinking and learning depends on the condition of the dialogic relationships, which should provide an emotionally secure basis for participants (Perret-Clermont, 2015).

A Dialogical Perspective to Explore Learning

What do we mean exactly by the notion of a “dialogic approach” referred to in this paper? From our perspective, the choice of a dialogic paradigm assumes two complementary purposes, as described below.

First, a dialogic approach can be considered a powerful way to effectively support socio-constructionist pedagogies. Dialogism in this sense is more than the “basic” idea that social interactions create favorable conditions for learning through the confrontation of different points of view (Markova, 2016).

According to the classical definition of Linell (2003), the dialogic paradigm is rooted on some basic assumptions. One assumption is interactionism: “the basic constituents of discourse are interactions (exchanges, inter-acts), rather than speech acts or utterances by autonomous speakers (authors, communicators)”. Another assumption is contextualism: “situated discourse is interdependent with contexts. One cannot make sense of discourse outside of its relevant contexts…”. The final assumption is the notion of communicative constructionism: “Knowledge is largely communicatively constructed, in the sociohistorical genesis of knowledge, language, communicative genres (routines)”.

In a way, the dialogic perspective (Linell, 2009) allows one to go beyond the mechanistic idea of socio-cognitive. For example, the second generation of socio-cognitive conflict theories (Carugati and Perret-Clermont, 2015) posit that the success of interactions essentially depends on each individuals’ point of view, on their interpretation of both the experimental settings and the perception of the others’ roles, and finally on the degree of mutual engagement in the task proposed (Psaltis et al., 2015).

Second, a dialogic approach should be considered a powerful tool to analyze the social interactions at play, within a systemic and inter-contextual framework.

In light of these elements, we were interested in studying the impact of movements between contexts on students’ ways of learning. In fact, movements create a need for continuous readjustments of academic knowledge to that acquired in other contexts.

Research

Aims

According to the theoretical premises discussed above, the basic aims of the approach were twofold, with both pedagogical and scientific objectives. The pedagogical objective focused on supporting students’ movements to allow their active participation in inter-context activities. From an educational point of view, this kind of student participation in the pedagogical processes should serve to foster their critical and social skills. The present article presents the project in detail; however, the pedagogical impact is only marginally addressed. Other specific contributions can be found in the bibliography.

The scientific objective focused on exploring, based on results of their movement between multiple contexts of activity, the transformation of students’ representations about the lived experience of the intricate relationships among human actors, objects, and spaces (Barad, 2007; Orlikowski and Scott, 2008; Fenwick et al., 2011), from sociocultural and sociomaterial perspectives.

Context and Participants

The empirical data presented in this paper were collected during a semester-long course entitled “Materiality in contexts”, held at the Department of Psychology and Education, University of Neuchâtel (Switzerland). It was selected and funded by the Rector’s Office of the University of Neuchâtel as an “innovative” pedagogical project. Twenty-six students, aged 19–24 years, attended the course.

The lessons were conceived as hybrid activities carried out in both the university classroom and the cultural association’s headquarters, using different sources of knowledge, such as reading, observation, experimentation, and debriefing. The course also allowed different types of interactions with individuals that included student peers, academics, association educators, and workshop participants (children and parents).

In order to achieve our pedagogical aims, the course design was conceived in four phases, as described below.

First Phase: Designing the Workshops

At this first stage of the course, the role of the teachers was twofold. First, they introduced cultural resources to advance students’ reflections about the roles of objects, space, and others. For example, they introduced lectures and reports about the Reggio Emilia pedagogical approach, according to which children construct knowledge about their environment through active exploration (Malaguzzi, 1998). Second, the teachers regularly supervised activities and discussions in each group.

In this first phase, the students’ task was to present, in groups, an outline of their workshop proposal, in which they specify their plan, their roles, and the content of their workshop. This proposal was not formally evaluated; rather, it was presented and discussed in the class, and modified according to the feedback received by the teachers and by other students. In this sense, the content of the course was not an end in itself, but was treated as a set of resources that mediated investigation (Wells, 2002). The group work and discussions in class were freely complemented with online collaboration between students (e.g., via Google Drive or WhatsApp groups).

This resulted in two full workshop proposals: a workshop inviting participants to create a musical instrument (workshop number 1) and a workshop inviting them to create a means of transportation (workshop number 2). The two workshops conceived in this first phase were realized by the students during the second phase.

Second Phase: Realizing the Workshops

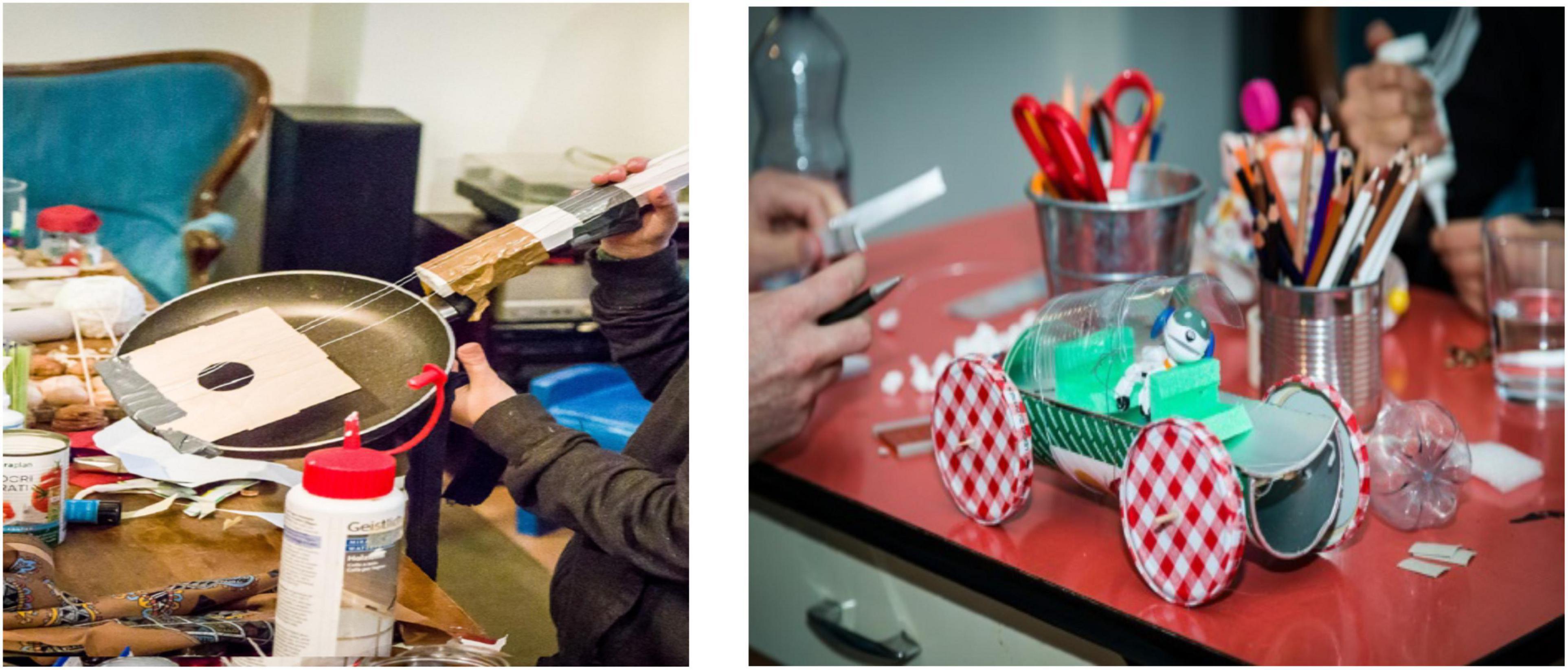

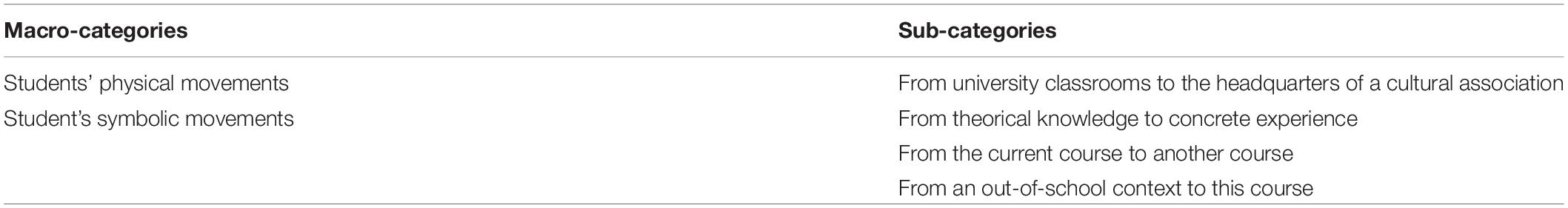

This second phase was carried out in a third space (a cultural association headquarters, within Neuchâtel city). During a 2-h long activity, participants who attended the atelier, which was promoted by the association, were invited by the university students to create: a musical instrument (workshop number 1) and a means of transportation (workshop number 2) (Figure 1).

The workshop participants engaged with natural or recycled materials (Figure 2) in a free-exploration manner; no formal guide or procedure was provided about how to create the musical instrument or means of transportation, or what materials should be used.

The activity workshops involved students, participants, and academics, as follows.

(a) A total of 26 students were involved: 8 students (4 for each workshop) introduced the activity, managed the planning of the activity and arranged provision of the materials; 10 students (5 for each workshop) were in charge of observing the situation, with the support of methodological tools created by the students themselves (e.g., observational grids, maps); and 8 students (4 for each workshop) were actively involved with the children and adults in the activity.

(b) Nine children and five adults (parents or caregivers) gathered with the students in the first workshop. Five children and three adults participated in the second workshop. All participants voluntarily took part in the activity, which was not part of an afterschool program.

(c) Two university teachers–researchers, together with two educators appointed by the association, attended both workshops to observe the activities.

Third Phase: Participant Debriefing

The two workshops took place on different dates so that each debriefing could be carried out separately. Immediately after each workshop, an informal debriefing was provided in the association’s headquarters, to allow students, university teachers–researchers, and educators to share feedback and observations about the activities.

During the intermediate period between the two workshops, a second debriefing was organized at the university, to give students the opportunity to discuss work strategies and difficulties, and to reflect on the development of their activity with their peers who had not yet carried out their activity.

At the end of the course, we gathered information from the students regarding their participation via focus groups and semi-structured interviews.

Our previous work presented the focus group results (Cattaruzza et al., 2019b); the current study reports the analyzed semi-structured interview results.

Fourth Phase: Reporting of Findings

In this last phase, the students were invited to reflect on their experience and course-related readings. The evaluation criteria adopted concerned students’ understanding about their learning experience. Students referred to their observations during the workshop and the resources mobilized, and their understanding of the learning experience was assessed in terms of theoretical references and based on the pertinence of the examples given.

Corpus of Data

Within the more general framework of the applied research described above, this paper deals specifically with students’ verbal accounts through which they reconstructed their participation in the activities and their interpretations of what was observed. The data are drawn from their individual reports (learning diaries, which were assessed) and semi-structured interviews. At the end of the lecture cycle, all students were invited to participate in an optional 45-min interview and seven of them accepted.

The data analyzed were obtained from the twenty-six students’ learning diaries and from the seven interviews of those students who gave explicit authorization to participate in the research. The interviews were conducted in a manner inspired by Vermersch’s elicitation interview technique1. Specifically, with this technique, the interviewer focuses on a fine-grained description of a “lived” experience (Vermersch, 1994), providing iterative questioning focusing on a specific past event. This type of interview technique was expected to result in as precise a description as possible of the focused event. In this particular research, the elicitation interview allowed a relatively precise reconstruction of the movements made by the students and the significance of their lived experience (Cesari-Lussi et al., 2015; Mouchet and Cattaruzza, 2015).

Data Analysis

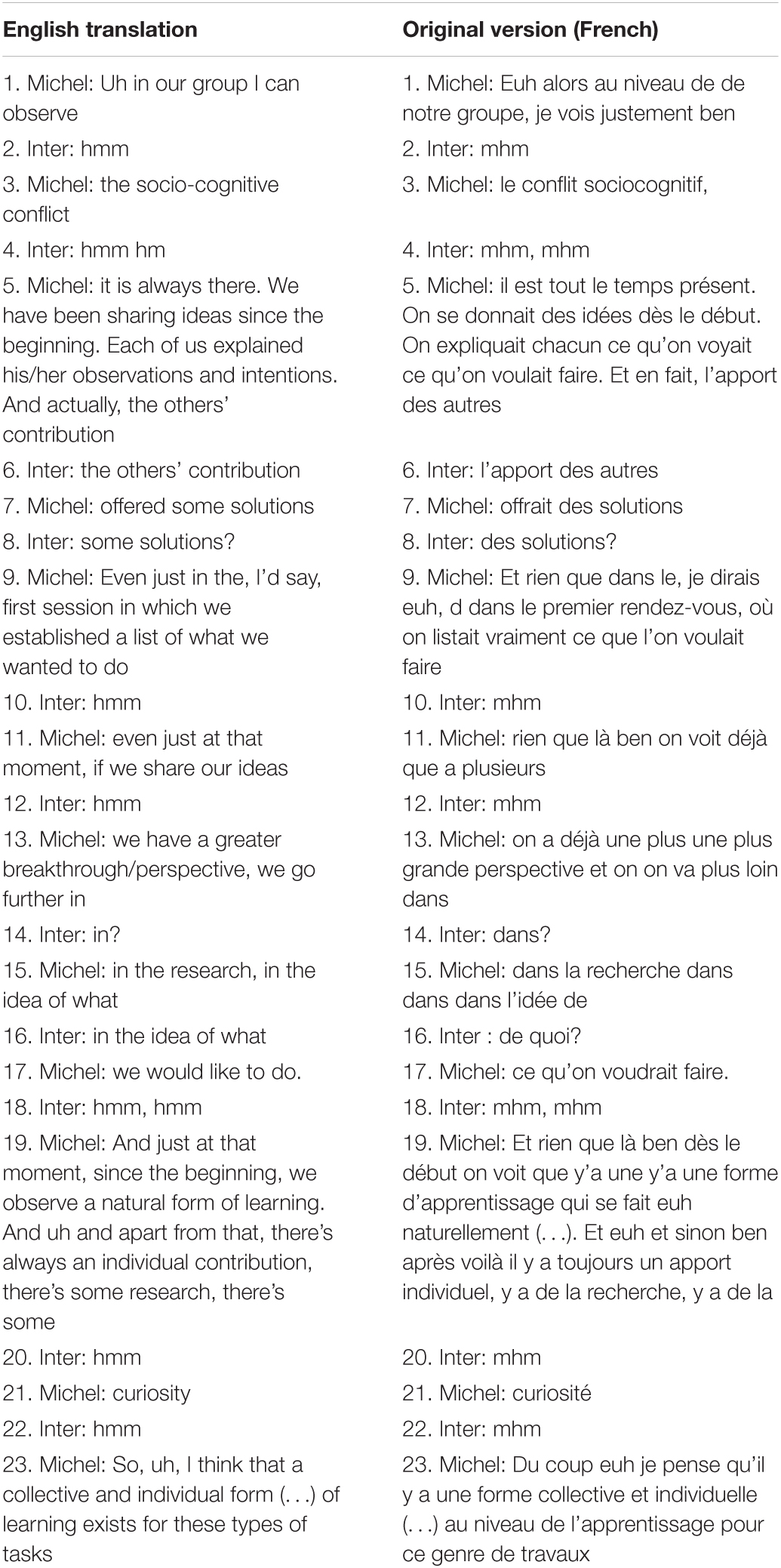

The data were evaluated using a purpose-built analysis approach comprising two macro-categories and three sub-categories. In order to determine these categories, independent analysis of the data was followed by meetings in which the findings were compared and coordinated. A note keeper was appointed to keep our discussion on track.

We began by reading the whole corpus of data. We then engaged in the process of open coding, to explore the topics contained in the raw data (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). In this phase of early coding, we broke data down into manageable pieces (excerpts) by identifying any connections that may exist, in order to produce a first draft of macro-categories. Subsequently, we negotiated a common name for the macro-categories, and we better defined the sub-categories. The purpose-built data analysis was finalized in this manner (see Table 1).

Academic Researcher and Teacher Roles: Ethical Boundaries

Being at the same time teachers and researchers, during the semester-long course, our responsibility was always to the students. Data collection, analyses and other research-related activities were completed at the end of the semester. In this sense, our “Teacher and analyst roles thereby become temporally separated” (Roth, 2005, p.245).

During the data analysis phase, we appointed an external researcher to act as a “disinterested peer” (Guba and Lincoln, 1989). The external researcher was actively involved in the coding process by providing additional observations. This allowed us to proceed at a distance from our presuppositions and beliefs by promoting a “cogenerative dialogue” (Roth, 2005). In accordance with Roth (2007), in order to prevent “power-over relationships”, “(…)where power over denotes the power differential between university teachers-researcher and his or her students” (Roth, 2007, p.6), the following practices were adopted:

(a) We assured students that their participation in the research was not mandatory, and would have no effect on their grade nor on their relationship with the university teachers.

(b) We employed a neutral tone in the recruitment and preliminary consent document.

(c) Confidentiality was assured.

(d) We collected data at the end of the semester course, when there was no longer a relation of power between the teachers and the students in the context of this course.

Results

The main purpose of this paper is to highlight the transformations of students’ representations of learning as a consequence of their involvement in an innovative pedagogical design, largely based on learning experiences both in the academic formal context and in an informal context of extracurricular activities. The data considered here consist of transcripts, verbal content from semi-directed interviews and individual reports in the form of learning diaries.

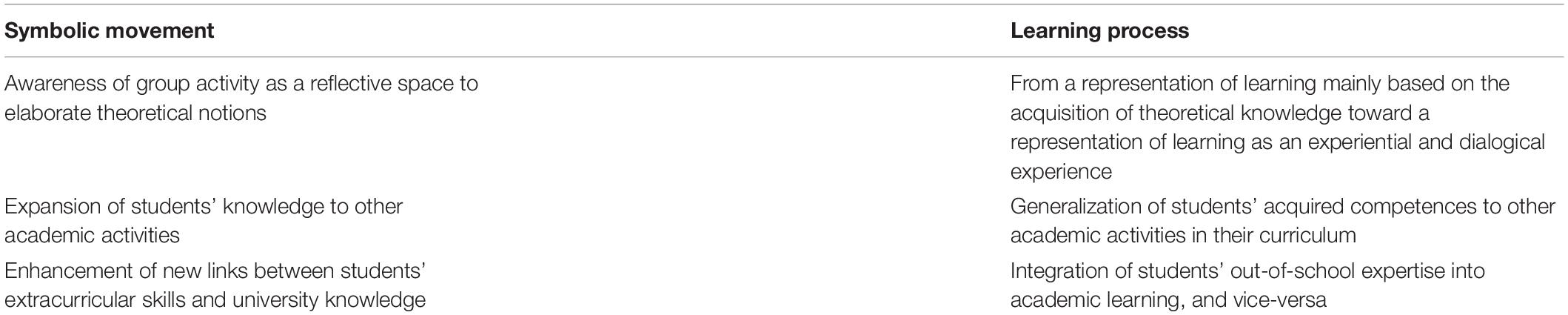

The results we report, based on the following excerpts, identify three main transformations in students’ representations of learning at the university: becoming aware of a group activity as a reflective space in order to elaborate on theoretical notions, extensions of knowledge to other academic activities, and enhancement of new links between extracurricular skills and university knowledge.

Becoming Aware of Group Activity as a Reflective Space to Elaborate on Theoretical Notions

During the individual interviews, some students gave precise reports on their collective experiences in the pedagogical project. The following examples show how this attempt to understand and qualify these interesting collective moments triggered the use of two concepts briefly introduced in the course and mobilized in other courses: the concept of socio-cognitive conflict (Mugny and Doise, 1978), and Vygotsky’s concept of productive versus reproductive imagination (Vygotsky, 1994, 2004).

In excerpt 1, Michel2 recalls the notion of socio-cognitive conflict (lines 1–3) to explain the dynamics of his group, especially the interplay of the individual and collective learning, which seems to happen “naturally” through group work in the context of the course.

In the above excerpt, Michel describes the inquiry process of his group by highlighting how the sharing of ideas contributed to the deepening of one’s own ideas (lines 5–17) and permitted them to “go further in the research of what they would like to do” (lines 15–17). According to him, the knowledge emerged in a “natural” way (line 19), not just as an individual experience, but as a collective form of learning (line 23).

In excerpt 2, extracted from Isabel’s individual report, the achievements of the group’s activity were explained by resorting to the Vygotskian notion of imagination (Vygotsky, 1994, 2004). Isabel’s group had to plan a workshop by envisioning the details of the activity. As she described in the report, the task was not entirely linear because the group was faced with many unknown factors (the excessive number of participants attending the workshop, a partially incorrect estimation of the time needed to complete the planned work, etc.).

According to Isabel, this group’s imagination echoes with the notion of what Vygotsky calls a productive imagination (Vygotsky, 1994, 2004). Sociomaterial resistances (Boissonnade et al., 2016) form the basis of her reflection, sharpened by her responsibility as a workshop facilitator to manage the unexpected.

As evident in both excerpts, students recalled theoretical concepts learned in previous courses to give meaning to their own experiences.

Extensions of Students’ Knowledge to Other Academic Activities

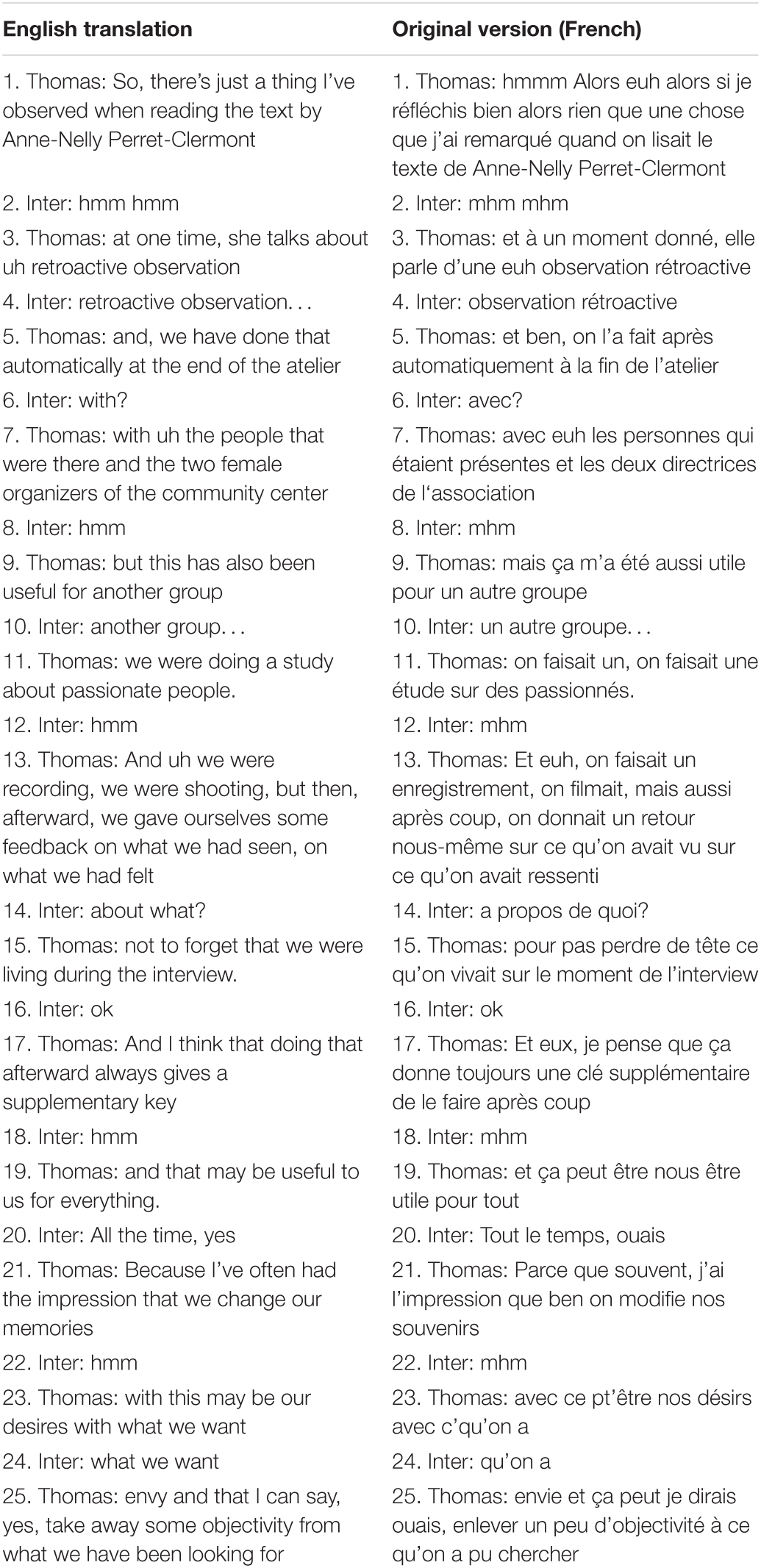

The following excerpt shows how a successful practice in the context of the course could be extended by the students to other project work or to another course. In excerpt 3, Thomas introduces the “retroactive observation”, a method presented in a paper discussed within the classroom. He explains how this method was useful in workshop activities but also in the project work for another academic course.

The research and learning practices acquired here in collaboration with the academics, professionals, and peers, could be appropriated by the students and re-used autonomously in other academic contexts. Characteristics of the pedagogical design may have supported some generalization of the contents learned; for instance, by recognizing the close interdependence between individual and collective activities. In fact, the pedagogical activities promoted exchanges among students and meetings in which students met other professionals (staff of associations) to organize activities to be carried out. In addition, to support students’ agentivity, a significant part of the responsibility for organizing activities had been transferred from academics to the students.

Enhancement of New Links Between Students’ Extracurricular Skills and University Knowledge

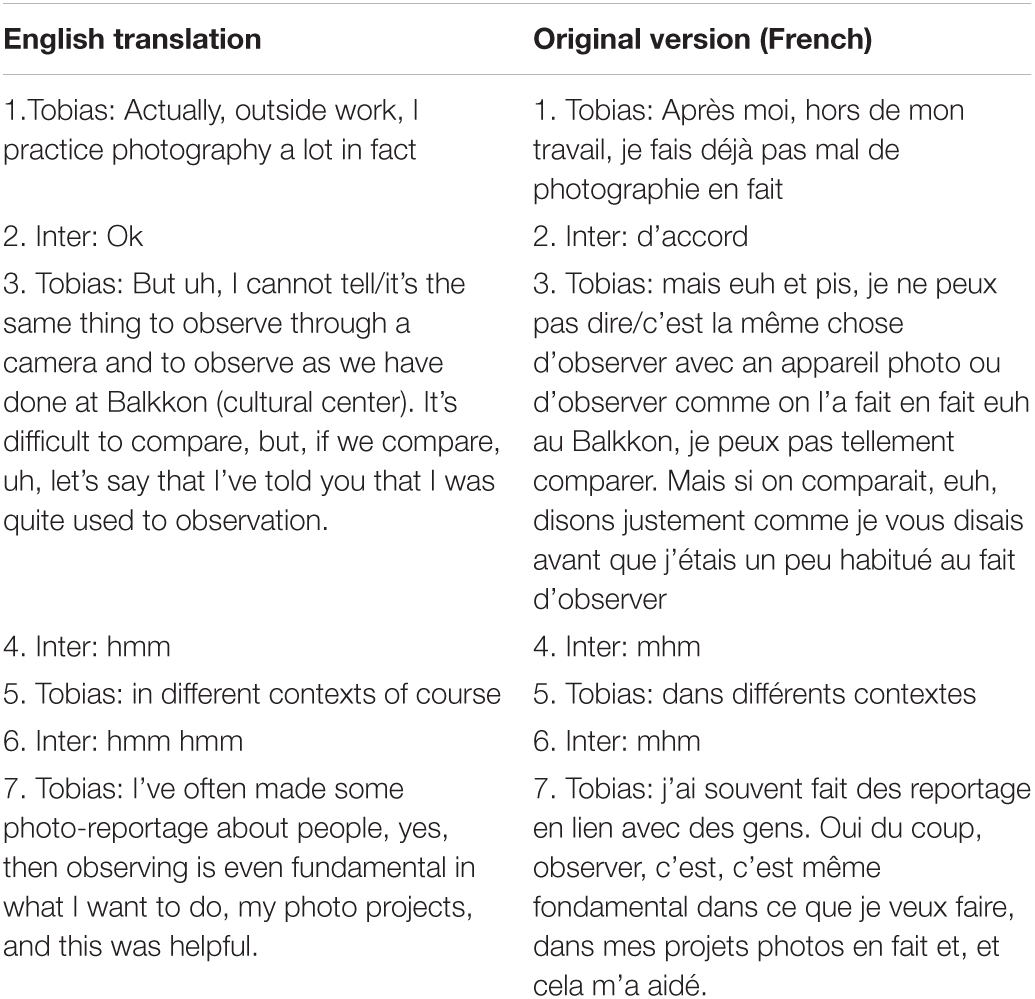

The following excerpts illustrate the bidirectional integration of out-of-school skills into academic learning. Excerpt 4 shows how Tobias combined his professional competences in practicing photography, with the needs of accurate observations during workshop activities.

Tobias argues (line 7) that his professional competence as a photographer was helpful for conducting accurate observations during the workshops. In the excerpt, Tobias also reflects critically on the specificity of observing in both contexts. Analyzing the excerpt, one also gets the impression that Tobias’ successful activities in the academic context have the effect of legitimizing his extracurricular photographic work.

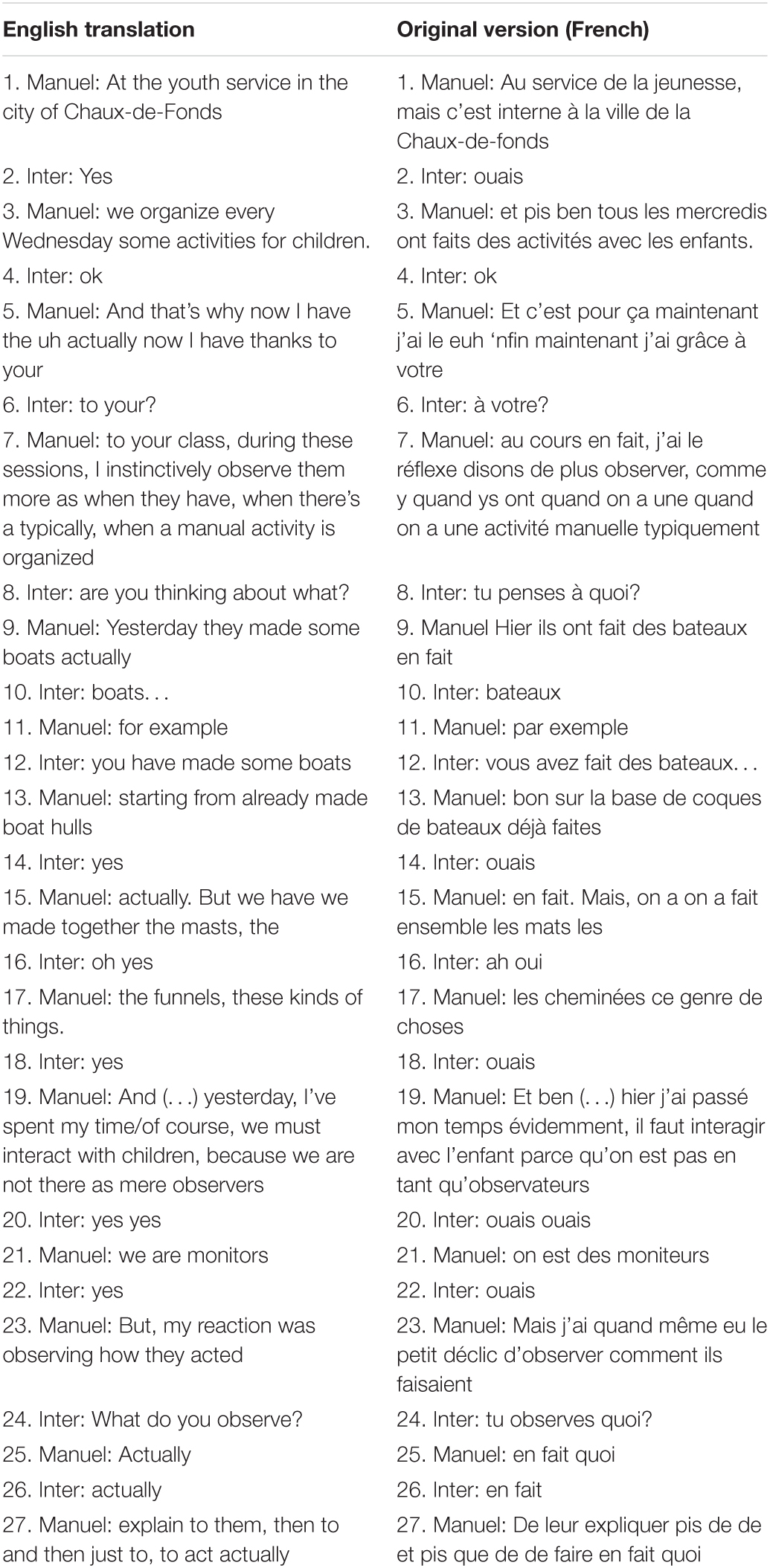

Similarly, Manuel explains below (excerpt 5) how participation in the pedagogical activities allowed him to transfer competences to his external work as a child educator. The fact that there were some conceptual and practical issues in common between the university course and his work as an educator undoubtedly facilitated this transfer.

Manuel’s participation in this academic activity encouraged him not only to do things with the children, but to observe the children too (line 23), in order to try and understand the complex and often implicit elements underlying children’s behavior.

Discussion and Conclusion

Analyzing both the interviews and the students’ reports, it is evident that the proposed pedagogical design had a significant impact on the students’ ways of both conceptualizing theoretical notions and combining them with rich everyday skills.

To support this position, we have highlighted in the students’ speech and texts those elements which, in our opinion, allow us to better identify the effects of the changes in perspective (that we have called “movements”) instigated by the pedagogical design.

Furthermore, the broad frame of the dialogic perspective that we adopted has been considerably useful, as it: (a) enhanced the selection of theoretical resources made available to students, (b) improved conception of the type of pedagogical intervention, and (c) helped to define research aims and interpretations.

We are convinced that, when considering social and contextual interaction as the minimum research unit, we had some concrete opportunities to understand the subtle interdependence between formal and informal learning.

It seems important to summarize (see Table 2) the main transformations induced by the movements that the students carried out from one context to another; these give an account of the main research findings.

In this sense, boundary-crossing seems to be useful for creating new expertise, by supporting changes in students’ perspectives (Tuomi-Gröhn et al., 2003). It implies, as Konkola et al. (2007) have stated, that “the school needs to prepare its teachers and students not just to do their assigned routine jobs but also to work as boundary crossers” (p. 217). Furthermore, giving students more opportunities to demonstrate their agency, and modifying the top-down relationship between students and teachers, can promote students’ engagement as citizens (Cattaruzza, 2019) and enhance their wellbeing (Savarese et al., 2019). As the data show, by crossing boundaries, students do not limit themselves to the routine work assigned to them; they become members of their local activity system or community (Wells, 1999), gaining new conceptual and practical learning tools (Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström, 2003). The challenge that we share with other scholars is “to structure the activities in such a manner that people are willing to see learning as worthwhile” (Säljö, 2003, p. 320; Engeström et al., 1995; Tuomi-Gröhn et al., 2003).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, upon request.

Ethics Statement

In this study we based on Federation of Swiss Psychologists code of professional conduct. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

EC, LK, and AI contributed to conception and design of the study. EC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. LK and AI wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The development of the course on which the analysis is based was funded by the Rector’s Office of the University of Neuchâtel as an “Innovative Pedagogical Project” (academic year 2017–2018).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Translation from the French: “entretien d’explicitation”

- ^ All names used in this paper are pseudonyms

References

Akkerman, S. F., and Bakker, A. (2011). Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Rev. Educ. Res. 81, 132–169. doi: 10.3102/0034654311404435

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Boissonnade, R., Kohler, A., and Iannaccone, A. (2016). “Essai sur les fonctions psychologiques de la résistance matérielle dans l’apprentissage lors d’activités informelles de bricolage,” in Paper Presented at the Colloque “La Conception d’un Artefact: Approches Ergonomiques et Didactiques”. Lausanne: Haute École Pédagogique Vaud.

Bronkhorst, L. H., and Akkerman, S. F. (2016). At the boundary of school: continuity and discontinuity in learning across contexts. Educ. Res. Rev. 19, 18–35. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2016.04.001

Carugati, F., and Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (2015). “Learning and instruction: social-cognitive perspectives,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn, Vol. 13, ed. J. D. Wright (Oxford: Elsevier), 670–676.

Cattaruzza, E. (2019). A Sociomaterial Perspective for Learning: Exploring Atelier Activities. Ph.D. thesis. Neuchâtel: Université de Neuchâtel.

Cattaruzza, E., Iannaccone, A., and Arcidiacono, F. (2019a). Provoking social changes in a family-school space of activity. Psychol. Soc. 11, 33–47.

Cattaruzza, E., Ligorio, M. B., and Iannaccone, A. (2019b). Sociomateriality as a partner in the polyphony of students positioning. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 22:100332. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2019.100332

Cesari-Lussi, V., Iannaccone, A., and Mollo, M. (2015). “Tacit knowledge and opaque action in the processes of learning and teaching,” in Reflexivity and Psychology, eds G. Marsico, R. Ruggeri, and S. Salvatore (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 273–290.

Corbin, J., and Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication.

Engeström, Y. (2016). Studies in Expansive Learning: Learning What is Not Yet There. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2020). Ascending from the abstract to the concrete as a principle of expansive learning. Psych. Sci. Educ. 25, 31–43. doi: 10.17759/pse.2020250503

Engeström, Y., Engeström, R., and Karkkainen, M. (1995). Polycontextuality and boundary crossing in expert cognition: learning and problem solving in complex work activities. Learn. Instr. 5, 319–336. doi: 10.1016/0959-4752(95)00021-6

Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., and Sawchuk, P. (2011). Emerging Approaches to Educational Research: Tracing the Socio-material. London: Routledge.

Gee, J. P. (2010). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gutierrez, K. D., Baquedano-Lopez, P., and Tejeda, C. (1999). Rethinking diversity: hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space. Mind Cult. Act. 6, 286–303.

Iannaccone, A. (2013). “Crossing boundaries. Toward a new cultural psychology of education,” in Crossing Boundaries. Intercontextual Dynamics Between Family and School, eds G. Marsico, K. Komatsu, and A. Iannaccone (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), XI–XVII.

Iannaccone, A., and Arcidiacono, F. (2014). “Les relations école-famille: questions méthodologiques [School-family relationships: methodological issues],” in Hétérogénéité Linguistique et esourcee dans le Contexte Scolaire, (Bienne: Hep-Bejune), 147–156.

Iannaccone, A., and Marsico, G. (2013). “The family goes to school. Talks and rituals of a meeting,” in Crossing Boundaries. Intercontextual Dynamics Between Family and School, eds G. Marsico, K. Komatsu, and A. Iannaccone (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 135–169.

Iannaccone, A., and Zittoun, T. (2014). “Overview: the activity of thinking in social spaces,” in Activities of Thinking in Social Spaces, eds A. Iannaccone and T. Zittoun (New York, NY: Nova), 1–12. doi: 10.4324/9780429452307-1

Konkola, R. (2001). “Developmental process of internship at polytechnic and boundary-zone activity as a new model for activity,” in (2003). Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary Crossing, eds T. Tuomi-Grohn, Y. Engestrom, and M. Young. Oxford: Pergamon.

Konkola, R., Tuomi-Gröhn, T., Lambert, R., and Ludvigsen, S. (2007). Promoting learning and transfer between school and workplace. J. Educ. Work 20, 211–228. doi: 10.1080/13639080701464483

Linell, P. (2003). Aspects and Elements of a Dialogical Approach to Language, Communication, and Cognition. Lecture first Presented at Växjö University, October 2000. Available online at: https://cspeech.ucd.ie/Fred/docs/Linell.pdf

Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking Language, Mind and World Dialogically: Iinteractional and Contextual Theories of Human Sense-making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Malaguzzi, L. (1998). “History, ideas, and basic principles: an interview with Loris Malaguzzi,” in The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach – Advanced Reflections, eds C. Edwards, L. Gandini, and G. Forman (Greenwich, CT: Ablex), 49–97.

Markova, I. (2016). The Dialogical Mind. Common Sense and Ethics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moje, E. B., Ciechanowski, K. M., Kramer, K., Ellis, L., Carrillo, R., and Collazo, T. (2004). Working toward third space in content area literacy: an examination of everyday funds of knowledge and discourse. Read. Res. Q. 39, 38–70. doi: 10.1598/rrq.39.1.4

Mouchet, A., and Cattaruzza, E. (eds) (2015). La Subjectivité Comme Ressource en Formation [Subjectivity as a Training Resource], Vol. 80. Lyon: ENS Editions.

Mugny, G., and Doise, W. (1978). Socio-cognitive conflict and structure of individual and collective performances. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 8, 181–192. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420080204

Orlikowski, W. J., and Scott, S. V. (2008). Sociomateriality: challenging the separation of technology, work and organization. Acad. Manage. Ann. 2, 433–474. doi: 10.5465/19416520802211644

Perret-Clermont, A.-N. (2004). “Préface,” in Joining Society. Social Interaction and Learning in Adolescence and Youth, eds A.-N. Perret-Clermont, C. Pontecorvo, L. B. Resnick, T. Zittoun, and B. Burge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), xv–xvii.

Perret-Clermont, A. N. (2015). “The architecture of social relationships and thinking spaces for growth,” in Social Relations in Human and Societal Development, eds C. Psaltis, A. Gillespie, and A. N. Perret-Clermont (London: Palgrave Macmillan), 51–70. doi: 10.1057/9781137400994_4

Psaltis, C., Gillespie, A., and Perret-Clermont, A. N. (eds) (2015). Social Relations in Human and Societal Development. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rajala, A., Kumpulainen, K., Ritella, G., and Wilkinson, L. C. (2016). Expanding conceptualization for the study of learning. Frontline Learn. Res. 4, 56–58.

Roth, W.-M. (2007). Doing Teacher-Research: A Handbook for Perplexed Practitioners. Rotterdam: Sense Publisher.

Säljö, R. (2003). “Epilogue: from transfer to boundary-crossing,” in Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing, eds T. Tuomi-Grohn and Y. Engestrom (Amsterdam: Pergamon), 311–321.

Savarese, G., Iannaccone, A., Mollo, M., Pecoraro, N., Fasano, O., and Carpinelli, L. (2019). Academic performance-related stress levels and reflective awareness: the role of the elicitation approaching an Italian university’s psychological counselling. Br. J. Guid. Counc. 47, 569–578. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2019.1600188

Tuomi-Gröhn, T., and Engeström, Y. (eds) (2003). Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing. Amsterdam: Pergamon.

Tuomi-Gröhn, T., Engeström, Y., and Young, M. (2003). “From transfer to boundary-crossing between school and work as a tool for developing vocational education: an introduction,” in Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing, eds T. Tuomi-Gröhn and Y. Engeström (Amsterdam: Pergamon), 1–18.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1994). “Imagination and creativity of the adolescent,” in The Vygotsky Reader (Original publication 1931), eds R. Van der Veer and J. Valsiner (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing), 266–288.

Vygotsky, L. S. (2004). Imagination and creativity in childhood. J. Russ. East Eur. Psychol. 42, 7–97.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic Inquiry: Towards a Socio-cultural Practice and Theory of Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wells, G. (2002). “Inquiry as an orientation for learning, teaching and teacher education,” in Learning for Life in the 21st Century, eds G. Wells and G. Claxton (Oxford: Blackwell), 197–210.

Keywords: boundary-crossing, dialogical learning, school and out-of school contexts, innovative course design, active participation

Citation: Cattaruzza E, Kloetzer L and Iannaccone A (2022) Boundary-Crossing Movements: A Resource for Student Learning. Front. Educ. 7:730263. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.730263

Received: 07 September 2021; Accepted: 21 January 2022;

Published: 24 March 2022.

Edited by:

John Lawrence Dennis, University of Perugia, ItalyReviewed by:

Johanna Pöysä-Tarhonen, University of Jyväskylä, FinlandDolly Predovic, Career Paths, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Cattaruzza, Kloetzer and Iannaccone. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisa Cattaruzza, ZWxpc2EuY2F0dGFydXp6YUB1bmluZS5jaA==

Elisa Cattaruzza

Elisa Cattaruzza Laure Kloetzer

Laure Kloetzer Antonio Iannaccone

Antonio Iannaccone