94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Front. Educ., 14 March 2022

Sec. Assessment, Testing and Applied Measurement

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.699627

This article is part of the Research TopicAssessment Practices with Indigenous Children, Youth, Families, and CommunitiesView all 12 articles

The compartmentalization of knowledge and of mind, body, and spirit to schooling is the antithesis of Indigenous epistemologies and the philosophical and relational aspects of assessment making. For Indigenous students, this contributes to the cultural mismatch between home and school. In the classroom there is continued focus on colonial methods of assessment and little emphasis on children’s natural processes of learning. Assessments highlight what students know, rather than how they know. Assessments impact student’s self-esteem, self-confidence, and influence their future prospects during their educational journey. Public education and its emphasis on grading and standardized tests as measures of learning, neglect to understand the unique and diverse ways of knowing that children come to their classrooms with. Kan’nikonhrí:io (Good Mind) means to move through life with respect, dignity, honor and responsibility and is necessary for becoming fully Kanien’kehá:ka or Onkwehón:we (Original People). Non-Indigenous educators and institutions serving non-Indigenous students can benefit from the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and epistemologies through raising awareness of Indigenous peoples history and contemporary realities, while enhancing a better understanding of the increasing cultural and learning diversity of student bodies. When children can bring their whole selves to their learning experience, including their spirits, while connecting the larger community, they can feel motivated for self-discovery through their lifelong adventure in learning, and they can be uplifted as they grow to be whole human beings with Kan’nikonhrí:io (Good Minds) and kind hearts. In this article, I offer a reflection on Indigenous holistic education and advocate for Indigenous epistemologies in public education including assessment practices as a way to address the TRC Calls to Action. Adapted from the AFS model, I offer a modified example of Indigenous holistic education here.

“Education is what got us into this mess…but education is the key to reconciliation.” -- The Honorable Justice Senator Murray Sinclair (2015)1

As I write this, we have been in a global pandemic for almost 2 years. The health, justice, economic, and educational inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples has greatly magnified during this time. It has been 5 years since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action were put forth. The Calls address all aspects of Indigenous peoples lives in Canada including: “#62 Develop and fund Aboriginal content in education” and “#63 Council of Ministers of Education Canada to maintain an annual commitment to Aboriginal education issues2.” According to the CBC website tracker “Beyond 94, Truth and Reconciliation in Canada3,” both of these Calls are listed as “In progress – Projects proposed” and only 13 out of 94 calls have been completed, 20 have not started at all, and the remainder have been proposed or are underway (Jewell and Mosby, 2020).

The public education system has been long overdue for an overhaul which has become most apparent during the pandemic amid lockdowns, spurts of online learning, mandated masking of children all day long, haphazard ventilation systems, and constantly changing regulations that confuse and anger both parents and children.

In addition, Indigenous children continue to face ongoing colonial structures that place education at the bottom of the priority list. The Canadian federal government has made promises to improve education for First Nations children, but funding continues to be inadequate. “Beyond 94” reports that there is still no Indigenous education legislation underway that would support sufficient education funding, improvement of educational attainment, development of culturally appropriate curricula, protection of Indigenous languages, and increased parental participation in their children’s education (see footnote 3).

In the classroom there is continued focus on colonial methods of assessment and little emphasis on children’s natural processes of learning as reflected in Indigenous epistemologies. Assessments highlight what students know, rather than how they know. Assessments impact student’s self-esteem, self-confidence, and influence their prospects during their educational journey. Public education and its emphasis on grading and standardized tests as measures of learning, neglect to understand the unique and diverse ways of knowing that Indigenous children come to their classrooms with.

Western colonial norms of education pervade every aspect of schooling from curriculum, institutional physical structures, policies, organization, communication, dress, and assessment (Trumbull and Nelson-Barber, 2019). The compartmentalization of knowledge and of mind, body, and spirit into schooling, sports, and church, is the antithesis of Indigenous epistemologies4 and the philosophical and relational aspects of assessment making. For many Indigenous students, this contributes to the cultural mismatch between home and school.

Indigenous epistemologies are grounded within one’s inner spiritual forces that as Willie Ermine states, “connects the totality of existence – the forms, energies, or concepts that constitute the outer and inner worlds” (Ermine, 1995). To understand the external, Indigenous ways of knowing turn to the inner spaces of our soul or spirit. There is holism in Indigenous epistemologies that recognizes the energy or force that exists within and between all living things, including the cosmos, our ancestors, and the unseen world. The very purpose of life is to uphold this worldview, to transmit this knowledge to future generations, and to ensure all of humanity benefits from remembering our purpose as human beings. A fragmentary Western world view severs the holistic framework for recognizing, nurturing, and maintaining the connection between the seen and unseen worlds.

In this essay, I offer a reflection on Indigenous holistic education and advocate for Indigenous epistemologies in Canadian public education including assessment practices to address the TRC Calls to Action. I first provide an overview of the Akwesasne Freedom School (AFS) and highlight the ways that this independent Mohawk school is grounded in Haudenosaunee worldviews which emphasize a child centered approach to teaching and learning and where children’s unique gifts and talents are nurtured. I share narratives of my family experiences within a western education system weaving threads that link across generations from my grandfather’s time at the Carlisle Indian School to my son’s current school experiences where there is little emphasis on identifying gifts and talents, a lack of Indigenous content and a fragmented approach to learning that is counter to holistic frameworks such as what is offered at the AFS. I explore Indigenous ways of knowing in education, the learning spirit, and offer alternatives to western models of assessments based on Indigenous holistic education. Finally, I imagine what education could be in the context of Indigenous holistic education frameworks, decolonization and reconciliation.

First, I must position myself with a proper introduction to who I am and what informs my own ways of knowing. I am a Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) scholar and a mother to a young child in the public education system in Quebec and whose experiences I share here. As an Associate Professor of First Peoples Studies, I am steeped in unraveling and reconstructing my own colonial education experiences, building up Indigenous pedagogy for my students, and advocating for my child’s educational needs.

In 2015 I published the text, Free to be Mohawk: Indigenous Education at the Akwesasne Freedom School, which is based on my doctoral research with an independent Mohawk language and cultural immersion school in my home community. The book is an exploration into the intersections of language, culture, and identity and offers a framework for holistic Indigenous education based on Haudenosaunee5 worldview. The Akwesasne Freedom School (AFS) is a space for children to explore their inner worlds, a place that instills a sense of kinship and connection to all living things, is heavily centered within the context of an Indigenous community. The AFS embodies the value of relationality while providing a nurturing environment for every child’s unique gifts to be identified, respected, and elevated so that every child may eventually become a whole human being or fully Kanien’kehá:ka.

The curriculum at AFS has strong foundations in Haudenosaunee philosophy and cosmology providing the means with which teachers assess children’s progress using portfolios as measures of achievement. AFS teachers are grounded in the cultural process of identifying the individual and diverse gifts of children and nurturing those gifts throughout their educational journey which is consistent with the Haudenosaunee philosophy of considering our actions of today and the impact on the next seven generations into the future (White, 2015).

In traditional Haudenosaunee education, it was the elders who noticed and nurtured each child’s unique gifts and talents so they may grow to become strong members of their community. When children are supported in such a way, they have freedom to explore their interests and strengths and they in turn become positive contributing members of the community.

The gift each child possesses is unique and takes patience, kindness, and a keen observation by teachers and community to help identify and nurture. Teachers at the AFS recognize that ALL children are gifted and each of them deserves to be taught in the way that they learn best. In supporting such gifts, children are cradled in a deeply rooted spiritual practice that positively contributes to their sense of self, gives them confidence as they blossom into adulthood, while allowing them the freedom to express themselves.

Akwesasne Freedom School parents share how their student’s gifts of singing and art were enhanced at the AFS. One child went on to pursue her gift of singing with a traditional women’s singing group. A teacher explains that a “hyper child” will “be my gym instructor.” Even those students who might be perceived as “difficult” are not ignored: “There was this one girl, they said ‘she’s so mean, so terrible,’…I said she’s going to be our leader because she has that strong spirit…Don’t take that out of her. We’re going to need her to stand up for us someday” (White, 2015, p. 102).

In mainstream public education with overcrowded classrooms, teacher shortages, lack of funding, inadequate infrastructure, and inefficient or absent support for neuro-diverse or learning challenged students, individual attention is often impossible, and everyone is treated the same. Therefore, the gifts of these precious children often go unrecognized, are forgotten, and become buried within their hearts and minds. It is a tragic disservice to these children who potentially lose out on finding their way through life, consumed in a capitalistic society that appears to value individualism and competition above all else. However, the AFS demonstrates that when there is a slowing down to the present moment, allowing for an opening of authentic deep connections, while the focus is on who they are as children, rather than on who they will become, there is space for their diverse gifts and talents to flourish.

I had hoped my son Skye, could benefit from a program like the AFS. In the years I was editing the book for publication as a mother to a young child, I often thought about what his education would look like. We lived too far from Akwesasne and there were limited opportunities for alternative education in the public or private sector where we live in Montreal.

I had another problem. I lived in Quebec where French school was mandatory without an English eligibility waiver, which was only obtained if either parent was educated in English within Canada. I grew up and did all my schooling in the U.S., in English. This doesn’t count however, because I did not go to school within the boundaries of Canada. I worked at an English-speaking University, and I didn’t know a bit of French. I was beside myself with worry about my child being forced into a colonial institution that was already devoid of Indigenous curricula and worldview and to top it off, in an unfamiliar language forced upon him, all while in our own traditional territory.

Like many Indigenous children, my son knows far more about the history of colonialism than his non-Indigenous peers because this history informs and shapes our everyday lives. Skye is aware of Indian Residential Schooling and settler colonialism and is resistant to learning French because he understands that French is yet another foreign language often forced upon our Haudenosaunee ancestors in our own territories. He learns this through our interactions with the outside world and through our many conversations about our family, culture, traditional territories, and why we don’t speak Kanien’kéha (Mohawk language).

There were many sleepless nights, as I lay awake feeling like a hypocrite for writing an entire book about the advantages of holistic education and advocating for heritage languages and cultures to be supported in schools. My child would receive none of that. Of course, I had no idea I would have a child who was gifted in many ways, did things in his own time, but who would also not by fully supported by public education.

Just before Kindergarten, Skye was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). I was worried about how he would fit in and be treated in a public school with limited resources. Because of his diagnosis, it was recommended that he attend English school to remove at least one major obstacle to his learning. So, my son began his education at a nearby English school in a small integration class for children who are neuro-diverse and “coded” within the school board system. Halfway through the year he made the slow transition to a regular kindergarten classroom. Because my son is academically advanced and “high-functioning,” his challenges are often attributed to “bad” behavior and educators overlook his individual needs as well as his talents and gifts. He has been called “scatter brained,” a “sly character,” and his behavior has been attributed to him being an “only child.” He slips through the cracks of an educational system designed to treat all students as one size fits all. He has been forced to adapt to the school, rather than the school and teachers adapting to his needs.

There has been a shortage of teachers and childcare workers (CCW), who are responsible for providing classroom support for “coded” students. My son had three different childcare workers in grade two who sometimes rotated their time in the classroom. The CCW’s are often undertrained, especially in a pandemic when the government hired anyone willing to do the job. It is not the fault of the teachers or CCWs. The system is failing them too. The lack of adequate training for all staff, particularly with students with ASD, has caused all sorts of additional issues for my child. For example, my child is often “put in trouble” as he calls it, by losing recess, made to sit in the quiet corner, or is sent out of the classroom for behavior he has difficulty controlling. Fortunately, he has had caring and patient teachers for the most part. His teachers are not fully supported in the classroom to better meet students’ individual needs. Like many, they must abide by a strict provincial curriculum, has additional students with “special needs,” and has had to rely on undertrained support staff who resort to handing out punishments instead of taking the time to help guide students like my son in making good choices. Tragically, under pandemic restrictions, the teachers could not even hug my child when he needs it most. Already overworked and underpaid, teachers have been under an exorbitant amount of stress and pressure.

I’m given conflicting information from various school staff that tell me on one hand “He’s so bright, a natural leader with lots of friends. There are no serious issues,” and the other, “He’s so disrespectful, aggressive, refuses to do his work, he hides in his locker. He’s been sent to the calming room again.” After requesting meetings with the school and insisting on more support, I’m told that he has a great team and that the school is doing better than most, and that my son just needs to work on being more “accountable.” This puts the burden on my 9-year-old son to dust himself off, be a big boy, and get along, rather than the school meeting him halfway to address their own accountability. It wasn’t until his struggles escalated to the point of knocking over chairs and shoving desks that the school finally sought the expertise of a specialist in ASD. Meanwhile, parents are all expected to “just hang in there because it will get better,” and “we are all in this together,” even though our children are struggling.

“Momma, today we learned about Moses!”

“Momma, I don’t want to learn French!”

“Momma, no one likes me at school.”

“Momma, I don’t want to go to school.”

(Skye, 9 years old)

In addition to the struggles my child faces as a neuro-divergent student, he is also subjected to a deeply colonial system of education that continues to perpetuate western models of pedagogy. The curriculum has little representation of Indigenous peoples, cultures, history, and contemporary realities. So, I continue righting the wrongs of proper cultural misrepresentation and undoing the damage incurred from being subjected to a colonial curriculum that erases Indigenous realities except for once a year on Orange Shirt Day. I will continue to support my son’s own ways of learning and to share with his teachers why it’s inappropriate to have young children playing the roles of “chiefs” in a school yard game. Approaches to teaching anything about Indigenous peoples, particularly by non-Indigenous educators, are often steeped within misinformed and misguided colonial frameworks filled with ignorance, racism, and stereotypes of Indigenous peoples.

I’m tired of doing damage control when my son Skye comes home from school and tells me he learned about “The Iroquoisee” today and that Indigenous Peoples came across Beringia from Asia. I had hopes that Skye would feel safe in school, that he would thrive, and where he could feel free to express himself and who he is as a young Onkwehon:we (The Original People) boy. Then came the week of September 30, Orange Shirt Day and National Day for Truth and Reconciliation here in Canada.

Initially Skye was very excited about having his very own show and tell on September 30 after his teacher invited him to share some of our culture. He sat in a circle on a blanket he brought from home. He wore his tobacco pouch and bear claw necklace, and before him he placed his rattle, a braid of sweetgrass, a bundle of sage, and a turtle shell which he held up as he told the Creation story and of Sky Woman falling onto turtle’s back.

It was his idea to bring a picture of his great-grandfather, Mitchell Arionhiawa:kon White, taken in 1909 at Carlisle Indian School. He passed the photo around the circle of classmates and quietly explained that his grandpa went to an Indian Residential School. The teacher had read a couple of books about Indian Residential Schools and many kids were wearing orange shirts that day.

Since the tragic news of children’s burials at former schools made the news a few months earlier there was at least some awareness of this history. Seeing all those orange shirts that day brought up a lot of very different and sometimes confusing emotions. I wasn’t surprised by any of the news since I was very familiar with this research, yet it was still gut wrenching every time a new story would surface.

I had been doing research for many years on my family’s experiences at Carlisle (White, 2017) and more recently have been working on locating burial sites for children who died at Carlisle and the Lincoln Institution in Philadelphia. I have walked through cemeteries looking for children who died, often never to find any indication of what happened to them. My son has walked that path with me (White, 2021a,b,c). He learned at a very young age what those institutions were for and the impacts they have had on Indigenous peoples, including our family. Survival and resilience run in his blood.

I had a hard time holding back tears of pride that day that my son sat as a proud confident young Kanien’kehá:ka boy sharing the stories of his ancestors. I told him how proud I was and reminded him that his great-grandpa, who spent his entire childhood at a residential school, wouldn’t have been allowed to share the creation story at Carlisle. When I was his age, I was made fun of during show-and-tell when I shared my red fringy poncho that my father bought me from the Bears Den Trading Post in Akwesasne. But now, he could feel proud to be Onkwehon:we and reclaim our stories and culture in honor of the children who were punished for sharing theirs. He was filled with pride that day.

That all changed a few days later. I picked Skye up from school the following week and we went to the park as we often do. He pulled some papers out of his bag and showed me his social studies test. My eyes immediately fixed on the word “Iroquois” toward the top.

Question one reads: “Choose the three statements that describe the first inhabitants of North America.” The answers to choose from include: “(A) They came from Europe; (B) They were nomads; (C) They were farmers; (D) They came from Asia; (E) They settled in one place; (F) They were hunters.”

I saw that my son chose as one of the answers: “(D) They came from Asia,” and my heart dropped. I kept reading. The next question asked him to place historic events in the correct order. He had to choose which came first: “The ancestors of Aboriginal people occupied a large part of America” or “The first inhabitants of America crossed the Beringia land bridge.” While he chose the former, it was marked as incorrect.

Tears began to well up in my eyes out of heartbreak. He had been seen. And then he wasn’t.

I had to do damage control. I talked with him at length about what he was learning. I dug out some books from home by Indigenous authors for younger readers. I explained that our people were always here, from the time Sky Woman fell from the Sky World and landed on Turtle’s back. I explained how early explorers were credited for founding north America when our people had always been here. And I told him they were wrong.

Then, I wrote to his teacher explaining how problematic it is that the curriculum presents Indigenous peoples in this way. Telling an Indigenous child that our creation story was wrong, that our people came from Asia across the Bering Strait, which was a theory and not a fact, was confusing and damaging. I told her that I hoped she would work with me to provide Indigenous perspectives to counter these colonial narratives and tackle this systemic problem to make real change and I sent her several resources. I said that she, the school, school board, and the Ministry of Education need to do more than wear Orange Shirts and instead do something real and tangible to address the issues raised by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

She responded quite defensively while explaining that she was just doing her job by teaching the required and approved curriculum. Then she added a line that made me realize how ignorant this young teacher was about Indigenous peoples: “They will learn about the creation story from different perspectives over their years of schooling. I am happy to see the resources that you sent in and will share them with the students and the other teachers. Unfortunately, I am still required to teach the material provided to me. Have a good day.”

A few days later my son brought home the social studies workbook. I had only seen the few pages from his test but now I was looking at the entire textbook. It was full of colonial language written by non-Indigenous scholars and educators. The most damaging is the image toward the back of the book captioned: “Missionaries captured, tortured, and killed by the Iroquois” (Cormier, 2021, p. 119). The image was of a historic drawing like those I have used to teach students about harmful stereotypes of Indigenous peoples. Several Indigenous men, supposedly “Iroquois,” wearing little clothing, their hair fashioned in the scalp lock that our ancestors wore, wielded hatchets over the heads of black robed missionaries whose hands were bound by rope, while on their knees pleading to the merciless “savages.”

I have seen hundreds of these types of damaging images over the years. But this one, and this time, it was my child’s eyes and heart that would be subjected to the damaging stereotypical portrayals of his own people. This is not just an abstract notion anymore; this is happening right in front of us. What would that do to his delicate and tender 8-year-old self who was still trying to formulate his own sense of belonging. This hurt. Deeply.

I told my son that when he has a social studies, he could skip it, refuse to take it, and/or answer from his own heart. Even if its marked wrong. He made the conscious choice to cover up the image with sticky notes and warned, “DO NOT LOOK!”

I explained to Skye that we don’t call ourselves “Iroquois” because it’s derived from Algonquin and French and means “rattle-snake people.” He had never heard the term because all he knows is that the Kanien’kehá:ka are part of the Haudenosaunee.

When I asked him how he felt about what he was seeing and reading in his textbook, he responded:

It makes me feel kind of sad to see all this stuff in a book. I want them to change it and tell the stories that the Onkwehon:we told. I don’t want to go to school learning these things. It makes me angry because they’re going to tell their parents and they’ll believe that. And then the people won’t believe our stories. They’ll be like no, no and argue and argue and it will turn into a big fight. I don’t want my friends to see it. They’ll think all Onkwehon:we are bad, they’ll think, kill all the Onkwehon:we. We’re not all bad, we’re the first to live on the land. I thought everybody was going to be nice to all Onkwehon:we now and then they’ll only believe the book and not believe me.

This young Onkwehon:we boy, living away from family and strong cultural roots already struggles to stand firmly and confidently among non-Indigenous peers. For a moment, he was able to reclaim the land he was standing on as he shared our stories. But then he was made to feel a foreigner in our ancestral territory and in the land, we call home. And that is a tragedy.

How can I defend the choice to send my son to a colonial institution that does a disservice to him on so many levels? It is my job to help him feel empowered by providing our cultural worldview and the emotional capacity to navigate his way through a world that can feel so foreign to him. But I often feel as if I’m swimming against the current.

Indigenous parent and student attitudes about schooling are informed by the history of colonial policies and practices of genocide, assimilation, eradication of cultures and languages, IRS, erasure of Indigenous peoples in curricula, historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, and affects the ways in which Indigenous peoples approach schooling (Trumbull and Nelson-Barber, 2019). As a result of historical and ongoing traumas, Indigenous peoples have learned the survival strategy of not completely trusting educational institutions. My son Skye’s own resistance to the rigidity of a western model of colonial education void of any Indigenous representation and sorely lacking in understanding and embracing neurodiversity, is a testament to his strengths and survival strategies.

My son’s school is rich in diverse cultures represented by students from all over the world, but those cultures are rarely represented in a real meaningful way, and when they are it’s around a particular holiday, rather than embracing the students own diverse cultures and the ways of knowing embedded within those cultures. This deeply colonial system to learning disregards the identities of students and how their cultures inform who they are and how they come to know. This is damaging to young minds and spirits.

There has been a great disruption to Indigenous ways of knowing, a severing of truths about who we are and our purpose, and with that a severing of knowledge to the next generations and ultimately a severing of our power. Colonization is ongoing, not just in land and resources, but over our bodies, minds, and spirits. The worldviews of Indigenous students do not shut off at the door to a school building but permeate all aspects of our lives and to deny or be cut off from our worldviews and cosmologies is to deny our very existence or to deprive Indigenous peoples of the essence of our life force. It is how we come to know and without it, we cease to exist as Indigenous peoples.

In Indigenous cultures, the source of all knowledge is deeply embedded within, it’s part of our inner world, and is informed by our collective understanding of who we are as Indigenous peoples birthed from the land and the stars, whose ancestors live in our blood and bone. The answers to life’s deepest mysteries lie within us. Our life force, the energy that flows within and between all things can become muddied and dim as we try navigating in a world bent on dividing up our minds, spirits, and bodies and where accessing the source of knowledge though ceremony, songs, and dance, has been outlawed and forbidden, creating shame and confusion. We have forgotten our Original Instructions. But our children and the next seven generations are the ones who will help us all return to living with a good mind and to living in balance, so we may all become whole human beings and whole in our spirits. Haudenosaunee philosophy considers how our actions today will affect seven generations into the future. The world we live in today is to be respected as we “are borrowing it from future generations6.”

The public education system and its shortcomings can learn from programs like the Akwesasne Freedom School. The AFS and holistic Indigenous education has the potential to transform learning environments for all children. At the AFS, the learning spirit is nurtured through Haudenosaunee teachings of living with Kan’nikonhrí:io (Good Mind), which means to move through life with respect, dignity, honor and responsibility and is necessary for becoming fully Kanien’kehá:ka or Onkwehon:we. The learning spirit is enhanced when someone has Kan’nikonhrí:io which is akin to a spiritual power that helps prepare young people for adulthood (White, 2015).

Learning can encompass practices that encourage children to be still and to clear their minds. Battiste calls this idea the “learning spirit” (Battiste, 2013, p. 181) as a method for increasing connections and engaging inner capacities, which in turn enhances learning.

As a model of Indigenous holistic education, the curriculum at the AFS, has a strong foundation in Haudenosaunee worldview, culture, and language. Students learn where they come from, their connection to the universe, and they learn ceremonies, songs, and traditional dances. They practice gratitude to all living things, and they do this through Kanien’kéha. In turn they develop values of respect, responsibility, stewardship of the Earth, and honoring kinship relations. They embody Kan’nikonhrí:io. The Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen (Words That Come Before All Else) is part of our Original Instructions from Creator and guide us in living with Kan’nikonhrí:io. When we express gratitude for all living things, we acknowledge the life force that connects to all things (White, 2015).

Essentially, AFS facilitates a holistic system of human potential whereby children embody traditional cultural values. There is an exploration and affirmation of identity and community belonging as there is emphasis on the whole person (spiritual, physical, emotional, intellectual). Learning about Haudenosaunee history helps instill a sense of pride and self-confidence and shapes their worldview. And students learn by doing. Like pre-colonization when classrooms were outside, they go out on the land, pick medicines, and learn from Earth’s teachers. Intergenerational transmission of teachings comes from elders through means of oral traditions and storytelling, which will guide them throughout their lives. Students grow up to become knowledge bearers and storytellers and continue to pass on cultural teachings to the next generation (White, 2015).

The AFS allows for a flexible and creative curriculum as well as evaluation and assessment. Each teacher may take a different approach to assessment, but all emphasize observation, listening, and welcoming both students and parents into the assessment process. Through use of qualitative portfolios that reflect the individuality of each student, parents and students are invited to discuss their progress. Even when report cards are utilized, parents and student are co-creators. Students at the AFS are evaluated on their ability to speak Kanienke:ha, reading and writing in the language, math, science, language arts, and social studies, as well as participation, attitude, socialization. Science may entail recognizing water animals and Sky Beings, while following instructions can be reflected in language arts. Social studies might focus on showing respect for others. Getting along with others is an important socialization skill that is also part of the assessment process. Language arts are assessed as children learn traditional stories. Because it shows socialization development, community activities outside of the school like ceremonies, are also considered part of a child’s learning, and growth potential and can become part of their educational assessment. The line between school and community is blurred because there is a sense of cultural continuity and therefore a child’s learning world is much more than what takes place inside of the school walls (White, 2015). There is a high level of trust from parent to teacher at the AFS because Akwesasne is a small community and teachers are known outside of the classroom. Sometimes they are aunties or cousins and all share similar ideologies about Kanien’kéha and the importance of transmitting language and culture to younger generations.

How success is measured is dependent on colonial values of material possessions, wealth, and prestige, disregarding Indigenous cultural values like caring for others. At the AFS, children learn to become good parents: “She learned how to be a good parent at the AFS…she’s an excellent mother” (White, 2015, p. 102).

There are many models of Indigenous approaches to education, learning, and assessment that are inquiry based, focus on children’s natural sense of curiosity, employ sacred circle teachings, and respond to the TRC Calls to Action (Anderson et al., 2017; Katz, 2018; Toulouse, 2018). Additionally, scholars Barnhardt and Kawagley (2005) provide numerous examples of Indigenous epistemologies embedded in education programs. Cajete (1994) focuses on Indigenous Knowledge’s and western science development in curriculum. Trumbull and Nelson-Barber (2019) offer a literature review of models of culturally responsive assessment practices in the U.S. Don Trent Jacobs and Jacobs-Spencer (2001) offers a character education guide rooted in Indigenous perspectives that help educators integrate core universal virtues like courage, fortitude, patience, generosity and humility across the curriculum. Developing good character does not mean adherence to any one religion or political affiliation. We can hopefully all agree that we want our children to be kind and compassionate human beings.

In his text “Teaching Truly: A Curriculum to Indigenize Mainstream Education,” (Jacobs et al., 2013). Jacobs offers practical tools for K-16 classrooms in core subject areas with a foundation in Indigenous perspectives and ways of knowing. This foundation in holistic Indigenous education helps equip teachers with an understanding of our connections to all things and our place in the universe so they may begin to focus on relationality in their approaches rather than compartmentalizing knowledge. In addressing the structural inequality in the education system and looking to Indigenous guidance, the field of teaching can be liberated as educators guide our young people to become independent thinkers living more consciously in the balance with the world. As we think about the purpose of education, we must think beyond one way of knowing, one knowledge, or one truth.

Holistic assessments are personalized rather than a one size fits all approach. Laughlin (n.d.) provides a model based on Indigenous holistic education in which assessments consider multiple perspectives and multiple places of learning. Perspectives of the students, parents, community members, and even librarians are considered along with the teacher’s assessment. Holistic assessment considers that children learn wherever they are and there is cultural continuity between home and school and community, creating multiple places of learning. In such a child centered way of assessment, the parents and students are empowered as they take charge of their own learning (Stonechild and McGowen, 2009).

As an educator, I often struggle within the confines of a colonial institution and the mandated grading system of academia, opting to offer my student’s alternative curricula and assignments that embrace creativity, and experiential learning options that create opportunities for sense making in their projects. For example, they may choose to be of service to an Indigenous homeless organization by gathering personal hygiene supplies, researching the topic of Indigenous urban populations, and working together with a group, all provide a meaningful learning environment. When they later create a portfolio reflecting on their experience and present it in a creative way through story, art or video, they embrace these projects with more enthusiasm and have a richer learning experience. They practice leadership skills when they lead discussions with their peers and provide peer evaluations to give each other feedback in their writing processes.

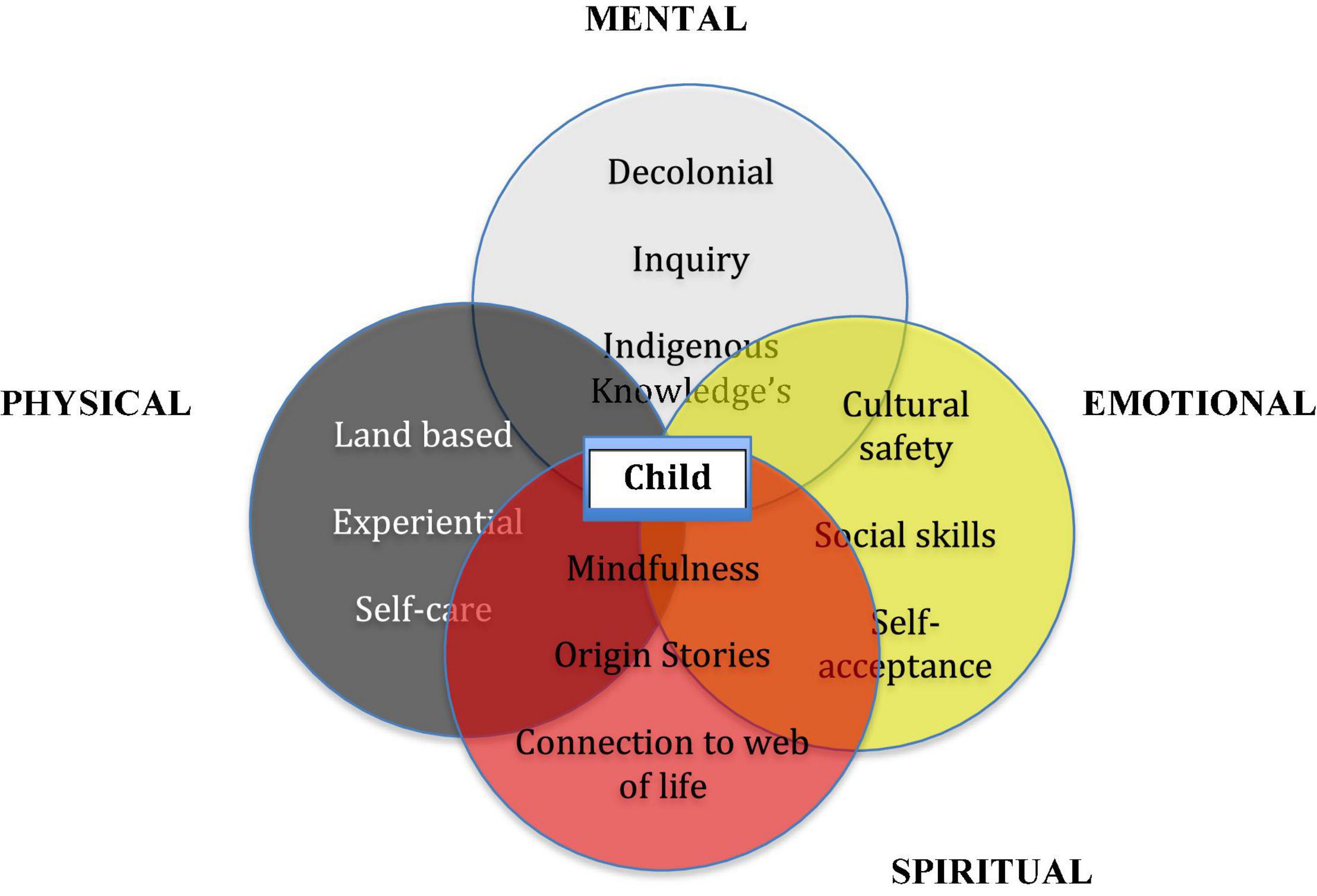

Indigenous holistic education has many models based on the Medicine Wheel and basic understandings of the self, or the whole human being who has mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional components. Adapted from the AFS model (White, 2015), I offer a modified example of Indigenous holistic education here (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Indigenous holistic education (White, 2015).

Children thrive when they are encouraged to think not only critically but creatively as well. Rather than having students create generic totems, schools could encourage deeper inquiry into the lives and cultures of Indigenous peoples, beginning with the land they occupy. As mentioned previously, an acknowledgment of the traditional land is a good place to start these conversations.

Rather than colonial retellings of history such as the Bering Strait Theory and making Onkwehon:we children believe we are merciless savages, children can learn about the complex history of Indigenous peoples and contemporary realities from Indigenous authors, elders, and guests who share cultural teachings. Some school boards in Quebec employ “spiritual animators” who come to various schools to talk about Orange Shirt Day. However, most, if not all of them are not Indigenous. When schools, boards, provincial government bodies talk of reconciliation, it needs to be backed by decolonial efforts in putting Indigenous voices at the forefront. Hire Indigenous “spiritual animators” to come to schools on Orange Shirt Day and extend the curriculum on Indigenous content to go well beyond one day in September. My son had the wonderful idea to have Tom Longboat Day7 in addition to Terry Fox8 day.

We read books on Indigenous hero’s including Tom Longboat at home. We talk about the spirits of the deceased bugs my son collects as he buries them with a tobacco offering and a prayer. Skye is very inquisitive about science, especially the cosmos. We talk of the stars, the universe, and the Sky World which is the place of our creation. When he goes to school, however, these teachings are contradictory to the lens of western science that his school adheres to.

In Indigenous holistic education, western science is complimentary rather than superior to Indigenous knowledge’s, which encourages cultural continuity between school and home. To help in that continuity, I send books on Indigenous heroes for his teacher to read, and more books on our creation story. But it would sure be nice if there was knowledge, respect, and resources for embracing Indigenous knowledges beyond his classroom. Books are a great way to open conversations but field trips to our nearby reserve communities to have medicine walks with elders, would go a long way in supporting Indigenous knowledges and invoking respectful curiosity among students.

We already know students learn best by doing. Experiential education focuses on the “doing.” Children thrive when they spend more time outside during their school days, exploring and learning from the land and Indigenous perspectives. Walking outside around the school could evoke lessons in learning about the traditional territory of the land the school sits upon. Students could learn about the plants and trees that grow in a nearby park by observing, drawing pictures, identifying parts of the plants, learning traditional Indigenous uses such as for medicine.

Modeling various means of moving our bodies promotes self-care. Children could greatly benefit from mindfulness practices like breathing, yoga, and somatic experiencing in which a connection is made between emotions, the nervous system, and the physical body.

Skye could learn more about how he experiences sensory overload and instead of kicking a chair or yelling when the classroom gets too loud, he could be reminded to wear his noise canceling headphones. He could be taught deep breathing and how to feel his breathe moving through his body until he feels calm. Skye told me he learns math best with his body. He explained that when he moves his body in the shapes of numbers, counts using his limbs and fingers, and moves around with classmates to add or subtract, he understands better. I told him this is a wonderful alternative to sitting at a desk with paper and pencil and suggested he tell his teacher about his idea.

When children learn about the cosmos, origin stories, and the great mysteries of life from Indigenous perspectives and they are internalized, “this identity relates to the larger web of life” (Jacobs and Jacobs-Spencer, 2001, p. vii). In a holistic model, children are encouraged to connect with themselves, can see themselves in their community, and learn to be of service to others, while appreciating the diversity of life. Furthermore, mindfulness practices that are trauma informed to respect the histories of genocide, oppression and ongoing realities could enrich a child’s spiritual development.

What if my son’s school embraced mindfulness practices like meditation and encouraged children to talk openly about topics like Indigenous creation stories that extend beyond reading a book but allow discussion surrounding the life’s great mysteries. Skye knows our Creation Story well. He also likes to tell his friends that his Momma has seen “ghosts” because that is the language that his friends understand. He is referring to ceremonial experiences that I have shared with him in which I witnessed “spirit lights.” I embrace talking to him about topics like death and what comes after, so he knows he’s never alone because our ancestors are always with us. How beautiful it would be if school were a safe space for him to speak openly about these topics.

Holistic education intentionally develops social and emotional skills throughout the education journey, rather than as a byproduct. Emotional development is nurtured when creating cultural safety for Indigenous children to feel safe and in which their voices are listened to without judgment. This guides them making friendships and connections to others.

There have been times when educators at my son’s school have outright asked him things like “what’s it like to be Indigenous?” which only serves to put an uncomfortable spotlight on him with such a broad question for a child. Creating an environment where Skye could speak about what it means to him to be Indigenous when and how he chooses, without pressure or judgment, can help him feel a sense of cultural safety (Cote-Meek, 2020) in which he can feel a sense of self-acceptance as he experiences outward acceptance. Reading age-appropriate books by Indigenous authors can help open conversations about the unique and diverse cultures of Indigenous peoples. Allowing Indigenous children to speak about their personal lives and families when and how they feel comfortable, helps create a safer space for those children to feel seen and listened to. If education allowed children to learn from an inner space of peace and acceptance of self, to play and learn in their natural states of being, the whole child is nurtured.

Marie Battiste says, “Every school is a site of reproduction or a site of change” (Battiste, 2013, p. 175). Do schools continue causing harms to Indigenous children or can educators take responsibility for understanding how education systems have harmed Indigenous peoples through failed assimilation policies and challenge unbalanced systems of power creating liberation for all?

When young people feel heard and respected, have freedom to explore, have space to grow, and who see themselves in who and what they are learning about, they can be equipped to go on to do great things in their lives busting out of the social hierarchy, empowered to become agents of social change.

The AFS is an effort in decolonization9 where the balance of power between repressive modes of education and Indigenous peoples has shifted. Mohawk youth thrive in a system once used to subjugate and control previous generations. When students learn their own history and culture, they feel empowered, and their self-confidence grows enabling them to have a secure future. Why can’t public schools adopt similar models?

We need education systems and teachers who embody the values of mutual respect, relationships, connection, and who understand the importance of identifying and nurturing each child’s unique gifts. We need those systems to support teachers and provide opportunities to engage in the practice of decolonizing education. Teacher education programs need to go beyond the abstract theoretical models of decolonialism and allow for the intentional embodiment and practice of what that looks like on an individual level within the classroom. Teachers need space and support to do this work and to provide “practices consistent with norms in Indigenous communities that provide space for students to assess their own progress and allow alternative ways of demonstrating knowledge and skills” (Kanu, 2011, p. 113). Children like Skye should not have to choose between their cultural teachings and that of opposing western frameworks that continue to press agendas detrimental to Indigenous people’s existence.

As reform is necessary in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous educational institutions, the AFS reminds us how culturally relevant curricula including assessment practices can have “far reaching influence on young people in a global society that increasingly emphasizes individuality, competition, and material gain” (White, 2015, p. 175). When schooling is made meaningful and involves real parent and student input, when students are engaged through experiential methods, education can “better serve diverse student bodies” (p. 176). Non-Indigenous educators and institutions serving non-Indigenous students can benefit from the inclusion of Indigenous perspectives and epistemologies through raising awareness of Indigenous people’s history and contemporary realities, while enhancing a better understanding of the increasing cultural and learning diversity of student bodies. All children can develop Kan’nikonhrí:io.

Educators and parents must ask: What is the meaning of education? Do we want to prepare our children for gaining material wealth as a measure of success? Or do we want to create systems that encourage young people to explore their unique gifts and talents, that help them tap into an inner knowing to guide them through their lives, to point them toward a trajectory of living freely, reaching their potential and contributing to a world where diversity in cultures and learning is respected?

For true reconciliation to move forward, settler society including educators must have difficult and uncomfortable conversations about colonization and institutional roles in the suppression of Indigeneity. Teachers must ask themselves what their role is in reconciliation and take responsibility in the classroom (Katz, 2018). They must question their own power and privilege by delving deeper into understanding whose lands do they stand upon. They must ask how they have personally benefited from the exploits of colonization. It would be beneficial to begin such inquiries with some self-reflection about their own histories and family legacies. For genuine and lasting change to occur, the work first must come from within individuals.

One positive step toward true reconciliation would come if local schools and school boards thoughtfully and respectfully created appropriate Territorial Acknowledgments. Indigenous students could feel a greater sense of visibility and belonging. Entire curricula can be framed around Territorial Acknowledgments beginning with lessons exploring whose land the school sits upon. A continuation could have students identify the traditional territories where they live and inquiring about what happened to the Indigenous peoples from that land. This might invoke questions like: where are they now? What language did/do they speak? What do you know about them? What more can we learn? A Territorial Acknowledgment opens endless possibilities for conversations about Indigenous Peoples. In fact, our local school board, the English Montreal School Board consulted with me about forming their own land acknowledgment. I helped draft Concordia University’s Territorial Acknowledgment and they thought I could help. In our discussions it was apparent they were merely interested in copying existing language so they could check off a box. Their progress has been slow, and I have not witnessed any substantial effort to do the front work necessary to birth their own meaningful land acknowledgment. I have also informed them of the problematic social studies textbook that has been forced upon my child with little response.

Schooling is often conflated with education with the former associated with institutions with rigid structures amidst the confines of four walls, where individualism and conformity ensure the production of citizens whose consumption contributes to a global economy based on greed and material wealth. The heart, love, and values like compassion are mostly neglected. Education on the other hand is lifelong and takes place anywhere. Holistic Indigenous education and alternative forms of education focus on nature and involve the greater community.

Imagine a reconciliatory approach to welcoming the diversity of student whole selves into a learning environment to usher in the next generation of change makers. Imagine if, rather than compartmentalization of mind, body, spirit into distinct physical locations like school, church, sports, home, community, there was integration into a holistic, reciprocal, and relational approach to education and where content is diverse in format and delivery. Imagine if educators were able to slow down, form authentic relationships with their students; know their life stories, backgrounds, and unique ways of knowing. If education was more humanized and teachers felt freedom to explore alternative methods of teaching and assessing their student’s knowledge and understanding with flexible outcomes driven by learner inquiry, then everyone benefits. Imagine a space where there is mutual understanding, a coming together for the benefit of all while recognizing that we are all related and where children rise with Kan’nikonhrí:io. It was disheartening to receive the response from my son’s teacher. Imagine if parents and teachers formed alliances to find the best strategies to help struggling children rather than proceeding as if we are on opposite teams.

None of these suggestions mean filling the void with generic Indigenous curriculum filled with stereotypes and non-Indigenous perspectives. Either Indigenous peoples are erased completely from curricula or are presented in such ways that render our present-day existence obsolete. It takes real commitment toward positive change. Imagine if the Ministry of Education engaged in meaningful consultation with Indigenous educators when developing textbooks and focused on our current realities rather than placing us in a solely historical context? Imagine if Skye created his own learning modules about our ancestors and current lives by speaking with elders, reading books written by Indigenous authors, creating a replica of a historic longhouse and then visiting a modern one. Imagine if his school made a respectful thoughtful request to invite a Haudenosaunee elder to his classroom to share our Creation Story. He would feel seen. He would feel understood and the gap between home and school would lessen. Holistic education models can achieve such imaginings.

The problems in our education system are not the fault of any one teacher, principal, or school board. States and provincial governments mandate outdated curriculum, force educators to “teach to the test,” while expecting teachers to move mountains with their students. The fault is systemic. The current system of public education continues to fail Indigenous children, particularly those with special needs. Society needs to do better at prioritizing our children and ensuring our leaders do the same.

It can feel impossible to dream when we are constantly faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles and reacting to continual crises. We all need to think about what kind of future we wish for our children and for the next seven generations? It cannot be left up to Indigenous peoples alone to bear. Do we want to make fear driven decisions and perpetuate more anxiety in our children, while encouraging domination over species, nature, and Indigenous cultures? Our children deserve safety in mind, body, and spirit. Indigenous ways knowing can help bring us all back to who we truly are, to help us all remember our origins as spiritual beings who can live more consciously. When children can bring their whole selves to their learning experience, including their spirits, while connecting the larger community, they can feel motivated for self-discovery through their lifelong adventure in learning, and they can be uplifted as they grow to be whole human beings with Kan’nikonhrí:io and kind hearts.

I can imagine such things for my son. I imagine his innate curiosity as a driving force for learning as he comes to understand his inner world and how his spirit, mind, and body come together as one. I imagine him thriving in an educational program where teachers take the time to understand his needs and gifts and support him along the way. According to Altogether Autism Takiwâtanga, the Maori of New Zealand have a term for Autism, “Takiwâtanga” which means: “my/his/her own time and space” which considers that “people with autism tend to have their own timing, spacing, pacing and life-rhythm10.” I imagine him seeing Indigenous peoples not only represented in the curriculum in a meaningful way but also having elders pass on teachings through oral tradition. I imagine him growing into his own inner space of stillness as he learns to listen to his own heart and spirit. I imagine him becoming Fully Human and transmitting these teachings to the next seven generations. I imagine him continuing to embody Kan’nikonhrí:io.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Anderson, D., Comay, J., and Chiarotto, L. (2017). Natural Curiosity 2nd Edition: A Resource for Educators. The Importance of Indigenous Perspectives in Children’s Environmental Inquiry. Toronto: University of Toronto.

Barnhardt, R., and Kawagley, A. O. (2005). Indigenous knowledge systems and Alaska native ways of knowing. Anthropol. Educ. Quart. 36, 8–23. doi: 10.1525/aeq.2005.36.1.008

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing Education: Nourishing the Learning Spirit. Saskatoon: Purich Publishing.

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the Mountain: An Ecology of Indigenous Education. Durango, CO: Kivaki Press.

Cote-Meek, S. (2020). Decolonizing and Indigenizing Education in Canada. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press.

Ermine, W. (1995). “Aboriginal epistemology,” in First Nations Education in Canada: The Circle Unfolds, eds Batiste, Marie and J. Barman (Vancouver: UBC Press).

Jacobs, D. T., England-Aytes, K., Cajete, G., Fisher, M. R., Mann, B. A., Mcgaa, E., et al. (2013). Teaching Truly: A Curriculum to Indigenize Mainstream Education. Oxford: Peter Lang Inc.

Jacobs, D. T., and Jacobs-Spencer, J. (2001). Teaching Virtues: Building Character Education ACROSS the Curriculum. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press Inc.

Jewell, E., and Mosby, I. (2020). A Special Report: Calls to Action Accountability: A 2020 Status Update on Reconciliation. Toronto: Yellowhead Institute.

Kanu, Y. (2011). Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives into the School Curriculum: Purposes, Possibilities, and Challenges. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Katz, J. (2018). Ensouling Our Schools: A universally Designed Framework for Mental Health, Well-Being, and Reconciliation. Newburyport, MA: Portage and Main press.

Laughlin, J. (n.d.). Report on Holistic Education: How Holistic Assessment Enables True Personalized Learning. Ottawa: Sprig Learning.

Stonechild, B., and McGowen, S. (2009). More Holistic Assessment for Improved Education Outcomes. Regina: University of Regina.

Toulouse, P. R. (2018). Truth and Reconciliation in Canadian Schools. Winnipeg: Portage and Main press.

Trumbull, E., and Nelson-Barber, S. (2019). The ongoing quest for culturally responsive assessment for Indigenous students in the United States. Front. Educ. 4:40. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.0040

White, L. (2015). Free to be Mohawk: Indigenous Education at the Akwesasne Freedom School. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

White, L. (2017). “White power and the performance of assimilation: Lincoln Institute and Carlisle Indian School,” in Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, & Reclamations, eds J. Fear-Segal and S. Rose (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press), 106–123. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt1dwssxz.11

White, L. (2021a). A Mother’s Prayer: Bring the Children Home. Indian Country Today Media Network. Available online at: https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/a-mothers-prayer-bring-the-children-home

White, L. (2021b). Are Your Ancestor’s on this List? Indian Country Today Media Network. Available online at: https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/are-your-ancestors-on-the-list

White, L. (2021c). The Search Intensifies for Boarding School Descendants. Indian Country Today Media Network. Available online at: https://indiancountrytoday.com/news/search-intensifies-for-boarding-school-descendants

Keywords: Indigenous, education, holistic, assessment, reconciliation, Akwesasne, Mohawk, Haudenosaunee

Citation: White L (2022) “Momma, Today We Were Indian Chiefs!” Pathways to Kan’nikonhrí:io† Through Indigenous Holistic Education. Front. Educ. 7:699627. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.699627

Received: 23 April 2021; Accepted: 17 February 2022;

Published: 14 March 2022.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Stavros Stavrou, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaCopyright © 2022 White. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louellyn White, TG91ZWxseW4ud2hpdGVAY29uY29yZGlhLmNh

†Having Kan’nikonhrí:io (Good Mind) comes from the Haudenosaunee teachings and means to move through life with respect, dignity, honor and responsibility

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.