- 1Department of Educational Foundations, Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile

- 2Faculty of Economics and Business, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile

- 3Department of Languages, Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile

The need to increase educational quality has led public policymakers to create and implement strategies for improving teachers’ skills. One such strategy, adapted in Chile, is the classroom accompaniment program, which has become a case of teacher professional development. The present study primarily seeks to understand public schoolteachers’ perception on classroom pedagogical accompaniment program (CPAP), and at the same time its effectiveness. This qualitative research is a case study framed within an interpretive paradigm, in which semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect data. A content analysis was done with 4 categories and 10 subcategories of perceptions attributed to the program and its effectiveness by 13 teachers, 8 females and 5 males, belonging to four public educational establishments. The results show opposed perceptions about the existing accompaniment program. On one hand, some teachers rate it positively and consider it beneficial for them and their students, who also received adequate feedback. On the other hand, another group of teachers considered that there were no positive contributions to their work performance, with impacts including greater reticence during the in-class observation process. Thus, the study concludes that the initial orientations and instruction regarding the role of the observing teacher are fundamental for the classroom accompaniment process to be effective and that it can be a valuable tool to apply for improving teacher performance.

Introduction

Access to quality education for all children is one of the top priority issues driving much of the effort around education in Chile. However, expected learning improvements have not yet been achieved. The tendency for learning as per the National Education Quality Measurement System (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación, SIMCE) test shows that language and math results have stagnated. Further, it was found that there was a negative gap persisting in school results between students from lower and higher socioeconomic levels (Quaresma and Valenzuela, 2017; Muñoz-Chereau, 2019). This fact, on the one hand, presents a major national challenge to improve achievement results, and on the other hand, shows the need to review the implementation of reforms oriented toward improving education.

One of the major factors influencing public policy outcomes is teachers’ perceptions of proposed policy changes or reticence toward quality measurement systems and accountability. Furthermore, multiple studies indicate that the teacher is the key element in educational transformation and, consequently, in learning achievement (Jackson et al., 2014; Ker, 2016; Duong et al., 2019; Roorda et al., 2020). Therefore, knowing teachers’ perceptions on the implemented policy measures is relevant for determining their impact or efficacy.

One of the programs implemented in Chile is the Pedagogical Accompaniment Program. This program seeks to provide technical and pedagogical support to teachers to help them improve the methodological practices with which they teach mathematics and language curriculum and content. However, for any program to be effective, it must recognize participants’ perceptions toward the same, given their impact on the success or failure of any intervention.

In this context, considering the aforementioned discussions, the objective of this study is to know the perceptions attributed by teachers in the Maule Region to the Classroom Pedagogical Accompaniment Program (CPAP) and its effectiveness. This is relevant considering that the efficacy of the program depends on teachers’ perceptions, and their understanding, which can guide the formulation of public policy in this area. In fact, studying the perceptions of teachers on the accompaniment program allows us to identify and highlight the key ideas that will favor a comprehensive understanding of this professional development strategy and guide initial teacher training. For this purpose, a case study methodology was used through semi-structured interviews, which were encoded and analyzed.

Background and Theoretical Groundings

Pedagogical Accompaniment

Pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy, which forms part of the professional development models centered on schools, fulfilling the challenge of breaking one of the greatest barriers in teaching: isolation and solitary work. According to Pirard et al. (2018), this strategy is oriented toward continual teacher training to improve their teaching skills. This occurs through a process of classroom intervention aimed at leaving behind the strategies designed and implemented by experts and specialists from outside the school and instead of becoming a knowledge source, through peer experience, generating knowledge around learning and its context (Vezub, 2011).

Haro (2014) indicated that pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy for collaborating with the teacher during the teaching process, principally by identifying weaknesses, lacks, and strengths observed in teaching practices and working to overcome difficulties in order to give better classes. In fact, evidences indicated that the practice of teacher accompaniment, along with others positively impacted teaching practices (Leithwood, 2009; Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019).

In other words, pedagogical accompaniment is understood as a peer knowledge construction procedure, which can become a powerful pedagogical practice improvement tool. However, Batlle (2010) maintained that accompaniment imposed vertically from above would become a tool of destruction. On the contrary, if it is approached as a horizontal, peer-driven process where experiences are shared for mutual enrichment as a team, accompaniment becomes a tool for building (Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019).

In fact, it is essential to ensure instances of teacher training, to support teachers in the use of acquired skills, to generate conditions for sharing ideas and practices, to show confidence in the work and progress of teachers, among other ideas that are reiterated by various authors (DiGennaro Reed et al., 2018; Duong et al., 2019). This is favored by the practice and process of classroom accompaniment, where both the assessor and the teacher in charge can achieve common learning objectives of students (Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019). Thus, evidence indicates that the teacher accompaniment strategy, interacting with other factors, has a positive impact on the improvement of teaching practices (Vezub, 2011; Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019) and on student learning (Berres Hartmann and Maraschin, 2019).

In the literature, there are researches, which demonstrate the impact of accompaniment programs on students and teachers, however, there are only a few studies evaluating the construction of the accompaniment programs based on the perceptions of the teachers. For example, Castro-Cuba-Sayco et al. (2019) studied the impact of the Strategic Learning Achievement Program in primary education students in Arequipa, concluding that it helped improve teachers’ professional practice and also contributed to students’ results in mathematics. In fact, they showed a high correlation between teacher competence and student achievement. Similarly, Berres Hartmann and Maraschin (2019) found that a pedagogical accompaniment program helped improve learning in children and the initial formation of pedagogy students.

It should be noted that according to Cardemil et al. (2010) the ultimate goal of intervention programs is to make educational quality a reality and that it is necessary to have classroom accompaniment involving observation followed by reflection on the events observed and seeking strategies to improve routines. Thus, observation and reflection are key elements in the accompaniment program.

Observation is used in various areas of human endeavors as a knowledge acquisition method. Classroom observation allows us to identify pedagogical practices, which contribute to student learning and aid teamwork, progressively improving relevant teaching practices. In other words, it aims to support the teaching and learning practices in the instructional process (Eradze et al., 2019). It analyses the characteristics of the performance of teachers and their students in the real context in which the educational process takes place, avoiding making inferences about what actually happens in classrooms (O’Leary, 2020).

On the contrary, the feedback of what has been observed is the sub process of teacher accompaniment, which considers a space for reflection and orientation with respect to what has been observed. The process of reflection is necessary for the accompaniment process to be effective for teacher training (Rojas et al., 2019). The feedback process occurs when the results of the observation are shared, analyzed, and understood jointly between the teacher and the observer. Leithwood (2009) says that positive and constant feedback is one of the leadership actions with the greatest positive impact on teacher performance. Its usefulness comes from allowing teachers to identify their errors and successes, reorienting their practices and constituting a learning source for them (Haro, 2014). Hence, the observation and feedback processes in the analysis of teachers’ perceptions of the classroom accompaniment program were considered to respond to the following research question of the study.

What are the schoolteachers’ perceptions on classroom pedagogical accompaniment program (CPAP) and its effectiveness?

Materials and Methods

The methodological design focuses on the qualitative interpretative paradigm, which allows the researchers to investigate social phenomena in the natural environment in which they occur, giving preponderance to the subjective aspects of human behavior (Mihas, 2019). It was considered the most appropriate approach because it properly fulfils the coverage and comprehension of the studied phenomenon (Alase, 2017). According to Arellano et al. (2018), “it allows us to approach our everyday life and to understand, describe and sometimes explain ordinary phenomena from within.” The incorporation of this approach in the research allows us to know, describe and interpret, from the participants’ (teachers) point of view, the effectiveness of the program. Specifically, the design strategy known as a case study is used, which allows the selection of real scenarios, which constitute sources of information (Yin, 2012; Mihas, 2019). This methodological decision makes it possible to highlight the perceptions of teachers on the Classroom Accompaniment Program.

Context of the Study

The teaching profession is currently recognized as being done and consolidated collaboratively; therefore, multiple pedagogical accompaniment programs have been implemented internationally (Vezub, 2011; Roorda et al., 2020). In Chile, important efforts have also been made to improve teaching practices and general educational quality (Escribano et al., 2020). In fact, education policymakers have come up with diverse strategies to improve educational quality and teacher performance. Among these, ideas such as the “National Induction and Mentoring System,” the “Teaching Teachers Network,” the “Shared Support Plan,” and “Classroom Advisory Programs” stand out.

The current study seeks to know the perceptions and the utility of the CPAP of the schoolteachers and the best way is to carry out a research listening to their voices for the improvement of teaching and learning. This further would provide information to the policy makers for taking policy decisions related to the educational quality.

In this context, in the Maule Region (Chile), through the support of a technical educational advisor, an implementation of the Classroom Accompaniment Program was carried out in 23 public schools for 1 year. This intervention consisted of supporting teachers in various public education establishments in the Maule Region, through this teacher accompaniment strategy. Specifically, this consisted in;

a) language and math classroom advisory, 90 min weekly for each teacher per class, throughout the year;

b) methodology course in language and didactics of mathematics through workshops of 2 h per month for each subject, throughout the school year;

c) delivery of teacher material: planners (annual-semester-class by class-unit tests-class guide), language, math, and delivery of student material: learning guides per class (language and math) and unit tests.

Participants

The Classroom Accompaniment Program was implemented in 23 public schools, of which four public schools were selected due to the diversity of their educational proposal. Three schools were from urban setup and one from rural area, wherein one from urban setup was exclusively a primary school, and the other three establishments were from both primary and secondary level. Each selected establishment responded to different educational and sociocultural needs. Within said establishments, the teachers interviewed were selected intentionally considering homogeneity and heterogeneity criteria of educational level and geographical locations. Two teachers from the rural setup, and 11 teachers from the urban schools were selected. Out of 11 teachers, 8 teachers were from two schools and 3 from one. Information was compiled on these 13 teachers, 8 females and 5 males, belonging to four public educational establishments. Each establishment represented a particular educational Project, manifesting the diverse reality of public education. The research technique applied was semi-structured interviews. This methodological decision makes it possible to investigate teachers’ perception of teaching, and its interpretation. Thus, it permitted learning about the study subject, the phenomenon under study, and about the concrete case in question (Yin, 2012).

In the semi-structured guided interviews, four dimensions were considered: perception of the program, the use of the program material, the impact on student learning achievement, and the opinion on the contribution of the Program to their own work. The interview was useful for obtaining information on how teachers reconstruct and represent the classroom accompaniment experience. In other words, the interview technique provided deeper access to teachers’ own words and their perceptions regarding the phenomenon under study. Furthermore, through this technique, the interviewer had the possibility of clarifying doubts and focusing on the subject, intending to go deeper into the phenomenon.

It is also important to highlight that there was a variation over time in terms of observation/co-teaching. In a survey, 92% of the teachers who started the program participated actively in the observation and co-teaching process over the time period of the program. There was no formal negotiation between the observer and the co-teachers in the design of the program. However, this negotiation occurred spontaneously through a horizontal dialogue among the participants, which included betterment agreements to achieve quality learning of the accompanied teachers and students correspondingly.

Ethical Considerations

The study followed ethical protocols and was approved by the Ethics Committees both from Universidad Católica del Maule and Universidad de Talca. Researchers personally informed the teachers selected for this study and duly signed their consent form. The validation process of the applied instrument was also carried out through expert judgment.

Data Analysis

Data treatment was carried out through the content analysis technique, which consists of reducing information by means of interview encoding to organize and group contents related to one theme (Krippendorff, 2018; Mihas, 2019). Systematization was carried out through the construction of integrating matrices of categories and subcategories. This process allowed the ordering of the significant segments that make up the information in the narratives to show the results as they were experienced and explained by the social actors. Initially, the analysis was done according to each source, taking into account the particularity of the guided interview, the informant, and the time at which the data was collected. The interview was carried out in the Spanish language, and the narratives were literally translated into English, to maintain the originality of the content. Data were transcribed and was grouped into categories and subcategories allowing for coding.

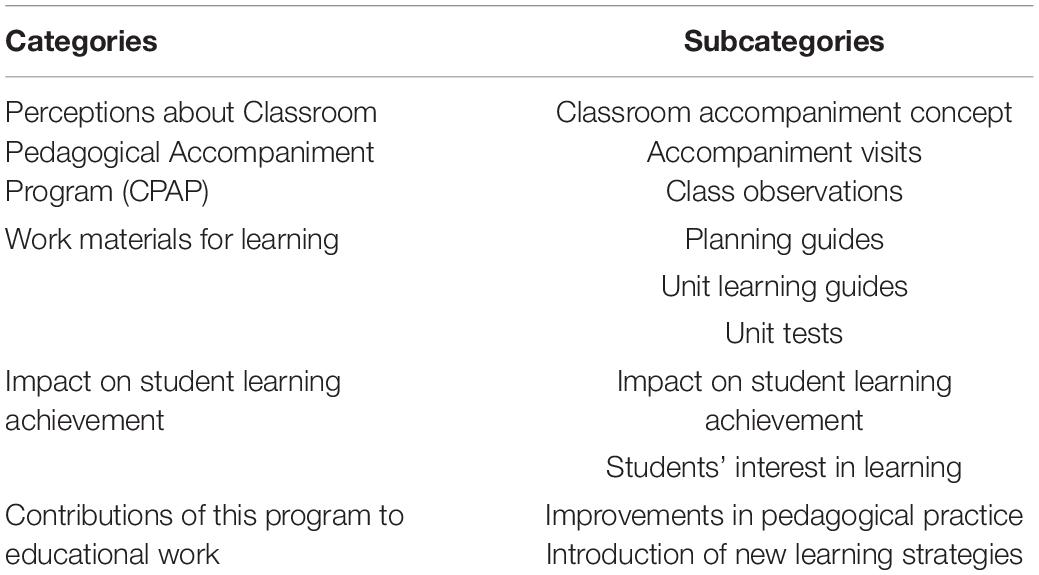

Subsequently, a systematic, rigorous, and exhaustive process was followed to reduce the data obtained and the judgment of the actors in order to arrive at a reasonable number of units of analysis that would allow them to be studied with precision and clarity (Male, 2016; Mihas, 2019). Specifically, four categories were outlined to develop data analysis, focusing on the principal themes set out in the study: perception of the pedagogical accompaniment program, working materials for learning, impact on student learning achievement, and contribution of the program to their educational work (Table 1). Each category is related to a series of subcategories that allow for a coherent link between the contributions from interviewees, literature review, and research objectives.

Results

Data analysis allowed identifying relevant aspects of the intervention under study, and thus get closer to the perceptions that the teachers had of CPAP. This section is structured around different assessments of teachers regarding the four categories of analysis as identified in the previous section: perceptions regarding the CPAP, contributions of working materials for learning, impact on student learning achievement, and CPAP’s contribution to educational work. The above-mentioned is in line with the research question raised in the study and in coherence with the objective that seek to understand the perceptions attributed by public schoolteachers of the classroom accompaniment program and its effectiveness.

Classroom Pedagogical Accompaniment Program Perception

Teachers value the process as an instance of support for pedagogical work, to the extent, it provides guidance for improvement on part of the observer. In most narratives, the observer was present in the classroom, but in different roles. The first one was a more passive role where the observer avoided interrupting the development of the class and in the second one, the observer was active, who interacted with both, the students and the teacher, that is to say, he or she developed more of a co-teaching role. This affects the perception of the program.

“This person observed a couple of classes, and then started participating in them–participation in the sense of accompanying the teacher wherever improvement or changes could be carried out in class, as perceived by her.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

“I do not know if everyone was the same, but at least the person I got. I cannot remember her name. It was just another colleague who helped me. Later, during the feedback, following were her comments on my teaching “look, this is good, we can improve this other thing”—yeah, good, pretty good.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

It should be noted that the majority of teachers interviewed positively evaluated the classroom observation process, to the extent that the accompanying teacher collaborated in the teaching process as another teacher in the classroom. This could be considered as a confusion between the accompaniment strategy and an assistantship or co-teaching strategy.

“The other person participated more in basically accompanying the kids. She went around seeing if the kid was working, showed a positive attitude, pretty cheerful. Some things caught her attention, and she mentioned them, but finally later on she also told me all the good and bad about my class.” (Language Teacher 2, School 1)

“For me it was not accompaniment, it was supervising. I saw it like supervision, from the perception she had of my performance with the students… well, I did not see it as someone accompanying, because for me accompanying, accompaniment is also, it’s interacting with students, right? And intervening.” (Math Teacher, School 4)

Teachers recognized and valued the feedback process, emphasizing the importance of this feedback being provided in a timely and rigorous manner. In various narratives, teachers mentioned participating in feedback, showing how CPAP fulfilled the stages corresponding to the accompaniment process. However, in spite of this, their narratives showed animosity toward the action of the observer during the observation process. For instance:

“She came several times. Most times she was observing, she was supposed to be observing and after we finished the class she gave some instructions-let’s say some indications of what needed improvement, or the way the content should be presented.” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

On the other hand, regarding the importance of the feedback process, teachers reiterated that the pedagogical accompaniment process fails to the extent that the feedback stage is ineffective or does not materialize. e.g.,

“There was no feedback, none, so when there’s no feedback, there’s nothing. I mean for me, I cannot say it was significant.” (Language Teacher 1, School 2)

“It was a great idea, a relief, I mean, a lesser load for us.” (Math Teacher 1, School 4)

They also emphasized that the intervention was conceived as a process of support for teaching as seen in the above comment. This understanding does not mean increasing the workload, but precisely the opposite.

Work Materials for Learning

The materials provided during the program were intended to be a tool for the development of the learning session, the context in which the reflective dialogue between peers takes place. In the case of the present study, the focus is centered on the interviewees’ views on the planning guides for the educational process. The opinions of the teachers are different with respect to the perception of the program. Some positively valued the delivery of abundant didactic material and the orientations from teachers who intervened in the accompaniment process. e.g.,

“I recall they did classes too, a demo class with all the parts of a class, so that generated lots of feedback. Professionally it was good because having another teacher from the same specialty in the classroom where you can share a learning experience is what helps you grow.” (Math Teacher 2, School 4)

“We teachers complain or complained that we did not have time to prepare material and those things, so I think from that point of view it helped.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

“The good thing is that the whole thing was put together, so it favored planning (…), so they went to the objective we needed, and then we just had to adjust a few things and not have to put together this entire plan.” (Language Teacher 2, School 1)

However, not all teachers used the material given by CPAP. This occurred for different reasons, either because they considered the materials not suitable for their students or because they did not fit in with their previous planning, e.g.,

“The guides, like I was saying, I used them, some of them. The folders they gave, some of us worked with them.” (Math Teacher 2, School 3)

“Let’s see, I used the ones I thought were pertinent for using…” (Language Teacher, School 3)

However, in the narratives a negative perception was frequently mentioned about the teaching materials that were given, maintaining that they were given to teachers at an inappropriate time, causing inconsistency with the material from the national curriculum or the traditional content sequence previously used by the teacher. As the following narratives indicate:

“The guides did not come in to fit the plan, so there was a lot of irregularity in how the guides and the tests are, or were ……I could not use them because I’m more structured with my classes, so what happened was, they would have the drama text up in the first unit and I did it in the last unit, so it did not come in order.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

In the same line, teachers highlighted the importance of contextualizing learning resources, insisting that each reality is diametrically distinct from the other and that therefore planning and supplies must respond to each reality. Focusing on this, the teachers insisted that the plans provided needed improvement, as they were standardized resources, which paid no attention to their students’ interests and learning styles. In this regard, some narratives had details such as:

“The way they’d planned and sent out these guides did not work in this reality, in this context … the students are used to their learning pace, and apart from that pace with these kinds of students you’ve got to constantly reinforce contents, something you did not see in the plans or guides.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

Furthermore, some teachers took on responsibility for the material provided, carrying out relevant contextual curricular adjustments and granting it the singularity, which would give significance and closeness to the application of the material with the students.

“I adapted, adjusted and changed it. It came in little notebooks, so each kid got one and all the semester’s guides went inside there. So before planning each class, I analyzed the plan, adapted it, and put in something really similar.” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

From the above narration, it could be inferred that this type of attitude required time and inclination to prepare for the class.

Impact on Student Learning Achievement

Pedagogical accompaniment aims to improve student learning through optimization of teaching practice performance in classrooms. Teachers also find further implications. For instance, some indicate there was an advantage for students:

“Yes, yes, they did it, obviously the kids learned the content…” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

“Achievement is always limited because there are some elements here that are part of student disinterest, and different factors that, that generate…, an effective and enthusiastic learning from the students.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Meanwhile, other teachers move away from the premise suggesting that the accompaniment implementation lacks evidence of learning (e.g., SIMCE national quality test results) and also shows a negative perception of the implementation of the program. For instance:

“I still do not know what the impact was because they have not given any information about it, so up to now I do not know what the impact on the students was.” (Math Teacher 1, School 4)

“I think the kids did not learn with it, what they need is something fun and didactic, and there was not anything like that.” (Language Teacher, School 1)

Teachers consider learning to be a complex process involving multiple factors. Therefore, it is risky to relate this strategy to the learning achievement, even more so when, according to the teachers there was no evaluation of the program. Thus, they were unable to see the effect in the follow-up tests on student learning, as this narration illustrates:

“Achievement is always limited, because there are elements here from student disinterest, and from different factors which, which generate an, an ineffective and unenthusiastic learning from students.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Teachers insist that the principal factor influencing learning achievement is teacher labor, and that they are responsible for the teaching-learning process.

“No, because it turns out that we brought the workshops, we brought the classes, we brought them in ready, they were planned by us.” (Language Teacher, School 3)

Some teachers were more radical when they indicated that the implementation of this program even impeded the student learning process.

“There was not any significant impact, because that year on the SIMCE, the kids did badly.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

As seen in the above narration, the teachers also emphasized the need for other strategy types involving motivational aspects synchronized with students’ interests.

Program Contribution to Educational Work

Regarding teachers’ vision about the contribution of the accompaniment program to improving their practice, it can be said that teachers were not indifferent. Some interviewees considered that intervention should improve various aspects to achieve positive impacts on pedagogical practice and student learning, while another group focused on relevant and significant aspects supporting their pedagogical work.

Specifically, some teachers had very critical impressions when they said that intervention fell short of expectations, basing their opinions on various reasons. The most reiterative arguments mentioned the lack of frequency of the accompanying teacher, the way they fulfilled an observation/supervision role, the insufficient or no feedback, bad coordination or non-fulfillment of CPAP development, and unfortunate attitudes or opinions on the part of these professionals, among various other opinions.

“The guides, yes, we could cut and paste, and do something, and at first that helped, but then later during classroom accompaniment we did not see any real contribution. Because, of course, the teacher’s in the room, observing…but there was not a follow up, like they do now, when they go into the classroom, there’s a chat, there’s a proposal, you want to improve.” (Math Teacher 3, School 4)

“No real contribution, it was not up to date, the teachers did not know about working in at-risk schools.” (Math Teacher 2, School 4)

“For me it did not help because I still had to do my plans.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

The above mentioned narratives make up a group of assumptions, which allow us to assume that implementation of the strategy evidently lacked rigor, or that the teacher union is resistant to change and/or criticism, which goes along with the accompaniment process. For example, this could be due to the lack of familiarity with the classroom accompaniment process, as shown by the uncomfortable attitude from the teacher and even the students with the mere presence of someone external within the classroom.

“Students were uncomfortable with her presence, because since they didn’t know her or why she came, the kids did not trust her and were uncomfortable with her presence.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Some other narratives value the public policy initiative, describing it as a positive intervention and offering important suggestions about implementing future projects involving classroom intervention. In fact, some narratives highlight the efficacy of the program and the shared vision of various teachers regarding its contributions, such as the following:

“A kind of discipline support, as far as confirming your knowledge, and training for new strategies, introducing new instruments, just general didactics.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

“I think the essence of the program’s a great idea, there should be more programs, but with the rigor you need to enter a classroom.” (Math Teacher, School 3)

“It was an accompaniment. The general perception of CPAP was that it was positive, both for the didactic material and for the teacher interviews guiding our practice. The trainings were related with that type of classroom support too.” (Language Teacher, School 3)

“It was an accompaniment, the general perception of the program was that it was positive.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

“Since this accompaniment was for primary school, she went with us too. And this teacher showed us, gave us some tools, more than anything, all related with reading comprehension.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

Some participants thought of pedagogical accompaniment as an instrument allowing educators to be attentive to methodological changes arising in the professional development process. Thus, this group of teachers considered it to be an orderly, continuous process to improve teacher performance in classrooms to positively influence students’ learning process.

Discussion

As previously explained, pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy for collaborating with the teacher in the teaching process, principally identifying weaknesses, lacks, and strengths observed in pedagogical practices and working to overcome difficulties to conduct better classes (Haro, 2014). However, the current study results show that both the participating and accompanying teachers must have clarity about their roles, especially to carry out properly the classroom observation procedure and feedback to achieve the expected results for accompaniment. It was found that the perceptions of the teachers changes according to the role played by the accompanying teacher, with participation being well-evaluated and a negative evaluation when there was little feedback. This can be explained by the type of relationship existing between the teacher and the accompanier, as indicated by Jerez Yáñez et al. (2019), who mention, if there is a horizontal relationship based on trust, respect, and quality, it facilitates the process of cooperation between the teacher and the assessor for the achievement of educational objectives.

In this sense, the teachers understand the CPAP process as a substantial support for their pedagogical work. This situation gives rise to guidelines for improvement on the part of the observer. However, in general, the interviewees’ narratives indicated little familiarity with the practice of classroom accompaniment, principally with classroom observation, a fearful and critical attitude regarding the observers’ actions, revealing tension and reluctance to expose their class to a third party. In this regard, Hamilton and O’Dwyer (2018) indicate that the assumptions and perceptions between teachers condition the collaboration between them. Thus, negative impacts from the program could be due to the teachers not desiring to receive feedback, which could lead to the failure of the intervention. This has been observed in other studies such as Rodríguez et al. (2016), who found that problems with implementing accompaniment programs, such as the accompanying teachers’ profiles, negatively affected their effectiveness.

Perception of CPAP is noted to be positive when there is feedback. This is because the information received by teachers allows them to identify errors and successes, thereby reorienting their practice and constituting a learning source for them, which was perceived positively by the participating teachers. Furthermore, it reflects that teachers value peer contributions (Miquel and Duran, 2017).

On the other hand, some teachers positively appraised the classroom observation process to the extent that the observer collaborated in the teaching process as an additional classroom teacher, confusing the accompaniment strategy with assistantship or co-teaching, or, in the cases where they received effective feedback, which supported teaching works. In this regard, Vezub (2011) indicates that the better the dialogue, in a climate of horizontality, interaction, personal disposition, and commitment, the greater the impact of this type of program. In fact, in some cases, the teachers’ perception of the accompaniment program is based on the domestic and affective bond formed with the professional “who accompanies,” showing a positive attitude toward the intervention when there is a liking for the observers’ actions. In other words, the greater the teachers’ willingness to be accompanied, the better their perception of the Program.

Teachers’ attitudes toward external intervention are also related to the dynamics of the educational institution, since the presence of a group of teachers who are interested in and open to this type of practice can positively influence their willingness to participate in the strategy and, therefore, their perceptions of it. It also occurs that when no culture of continuous learning is present, many obstacles are visualized for implementing accompaniment strategies among teachers, precipitating negative attitudes toward change.

Additionally, perceptions about low contributions from the program to students show that teachers expect short-term and instant results from public policies, even knowing that the effects of classroom accompaniment programs can be seen in students over the medium and long run (Rodríguez et al., 2016; Berres Hartmann and Maraschin, 2019). This could be explained by the fact that the accountability system exerting pressure on teachers and may impact the vision of the education process (Elacqua et al., 2016).

The preceding forms an array of presumptions, which allows us to assume that, on the one hand, the implementation of the strategy lacked the necessary rigor, or rather that it was necessary to work on the teachers’ disposition since they were reluctant to participate in this type of intervention with the openness that the accompaniment process needs. Furthermore, the results show the importance of adapting classroom accompaniment strategies to context. For instance, plans and inputs or materials should respond to the reality of the educational establishments, especially for those with lower learning. Thus, if an accompaniment program is implemented, it should not be standardized but adapted to different types of schools.

Finally, as a summary taken from the above-mentioned discussions, it can be stated that the CPAP is an effective tool for enriching the pedagogical work, which influences the learning process of the students. In agreement with the results obtained in the study, it can be highlighted that the accompaniment program of the teachers reveals three main steps for its successful implementation. The first being the mutual agreement between the two actors on the class-organization before its start to carry out the accompaniment process in the pedagogical program. The second being the observation of the class for the execution and development of the accompaniment program as agreed in the first step. Finally, the pedagogical dialogue between the actors that allows to the betterment of the teaching learning process based on the feedback and outcomes of CPAP. The later allows taking future pedagogical decisions in an optimal way.

Conclusion

The perceptions communicated by the interviewed teachers regarding the classroom accompaniment program are diverse, with the predominant idea being that classroom accompaniment is a useful strategy when implemented with the rigor needed in any intervention undertaken in the sensitive teaching-learning process. They also said that both parties; main teacher and the accompanier, need to have a shared vision of the program.

In the same way, teachers showed multiple visions about the initiation of the classroom accompaniment program and its effects. Many of the interviewees positively appraised the classroom observation process to the extent that the accompanying teacher collaborated in the teaching process as another teacher in the classroom. This represents a misconception of the strategy, confusing pedagogical accompaniment with an assistantship or co-teaching, which distorts perceptions of the process and its objectives. Thus, initial orientation and instruction about the role of the observing teacher are a priority for classroom accompaniment process effectiveness.

Regarding teachers’ vision about the contribution of the accompaniment program to improving their practice, the results indicate that there are diverse perceptions. One group of interviewees considered that the intervention needed to improve various aspects to positively impact in pedagogical practice. Another group highlighted relevant and significant aspects of support for their pedagogical work.

Regarding the use of material, the teachers’ critiques focused on the rigor of their development, highlighting the importance of learning resource contextualization. However, some teachers took on some responsibility regarding the material provided, carrying out the necessary curricular adaptations for their context. They also positively valued the support for reducing their workload by having class material available.

Regarding the impact of classroom accompaniment on student learning, the interviewed teachers highlighted that learning is a complex process involving multiple factors, emphasizing that the principal factor influencing learning achievement is teachers’ labor. They were primarily responsible for the teaching-learning process.

In general, the teachers who participated in this study considered the classroom accompaniment program to be a valuable initiative toward improving teaching. CPAP, as shared by the teachers, is expected to be implemented more rigorously and with attention to the educational context where it takes place. The teachers valued the process to the degree that it supplied tools for improving pedagogical practice, thereby affecting student learning. Therefore, it is concluded that this type of program can be carried out by considering the selection process of classroom observer, informing all actors of the process to reduce reluctance, providing adequate guidance on the actors’ roles, and adapting the contents of the program to the specific reality of the schools. That is to say, there could not be a standardized solution for peculiar realities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee from Universidad Católica del Maule and Universidad de Talca. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) under Fondecyt Regular number 1170369 of the year 2017.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 5, 9–19. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

Arellano, R., Costa, E., and Moreira Ribeiro, J. (2018). Conocimiento y contextos interculturales: enfoques cualitativos. Rev. Forum Identidades 27, 201–212.

Batlle, F. (2010). Acompañamiento docente como herramienta de construcción. Rev. Electrón. Hum. Educ. Comun. Soc. 5, 102–110.

Berres Hartmann, A. L., and Maraschin, M. S. (2019). Programa de Apoio Pedagógico: contribuições para a aprendizagem matemática de alunos do CTISM/UFSM e para a formação inicial de professores. TANGRAM Rev. Educ. Mat. 2, 96–105. doi: 10.30612/tangram.v2i4.9667

Cardemil, C., Maureira, F., Zuleta, J., and Hurtado, C. U. (2010). Modalidades de Acompañamiento y Apoyo Pedagógico al Aula. Santiago: CIDE-UA HurtBowado.

Castro-Cuba-Sayco, S. E., Espinoza-Suarez, S. M., Bejarano-Meza, M. E., Martinez-Puma, E., Ramos-Quispe, T., and García-Holgado, A. (2019). “The impact of the strategic learning achievement program in primary education students in Arequipa,” in Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop, Aachen.

DiGennaro Reed, F. D., Blackman, A. L., Erath, T. G., Brand, D., and Novak, M. D. (2018). Guidelines for using behavioral skills training to provide teacher support. Teach. Except. Child. 50, 373–380. doi: 10.1177/0040059918777241

Duong, M. T., Pullmann, M. D., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Lee, K., Benjamin, K. S., Nguyen, L., et al. (2019). Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. Sch. Psychol. 34, 212–221. doi: 10.1037/spq0000296

Elacqua, G., Martínez, M., Santos, H., and Urbina, D. (2016). Short-run effects of accountability pressures on teacher policies and practices in the voucher system in Santiago, Chile. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 27, 385–405. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2015.1086383

Eradze, M., Rodríguez-Triana, M. J., and Laanpere, M. (2019). A conversation between learning design and classroom observations: a systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 9:91. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020091

Escribano, R., Treviño, E., Nussbaum, M., Torres Irribarra, D., and Carrasco, D. (2020). How much does the quality of teaching vary at under-performing schools? Evidence from classroom observations in Chile. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 72:102125. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102125

Hamilton, M., and O’Dwyer, A. (2018). Mixed but not mixing: enabling agency and collaboration among a diverse student teacher cohort to support culturally responsive teaching and learning. Educ. Res. Perspect. 45, 41–70.

Haro, Y. (2014). Propuesta de Acompañamiento Docente en el Aula para la Escuela Básica Blas Caña. Master’s thesis. Santiago: Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

Jackson, C. K., Rockoff, J. E., and Staiger, D. O. (2014). Teacher Effects and Teacher-Related Policies. Annu. Rev. Econ. 6, 801–825. doi: 10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-040845

Jerez Yáñez, Ó, Aranda Cáceres, R., Corvalán Canessa, F., González Rojas, L., and Ramos Torres, A. (2019). A teaching accompaniment and development model: possibilities and challenges for teaching and learning centers. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 24, 204–208. doi: 10.1080/1360144X.2019.1594238

Ker, H. W. (2016). The impacts of student-, teacher- and school-level factors on mathematics achievement: an exploratory comparative investigation of Singaporean students and the USA students. Educ. Psychol. 36, 254–276. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2015.1026801

Krippendorff, K. (2018). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology, 4a Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Leithwood, K. (2009). >Cómo Liderar Nuestras Escuelas? Aportes Desde la Investigación. Santiago: Fundación Chile.

Male, T. (2016). Analysing Qualitative Data. Doing Research in Education: Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publication.

Miquel, E., and Duran, D. (2017). Peer Learning Network: implementing and sustaining cooperative learning by teacher collaboration. J. Educ. Teach. 43, 349–360. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2017.1319509

Muñoz-Chereau, B. (2019). Exploring gender gap and school differential effects in mathematics in Chilean primary schools. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 30, 88–103. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2018.1503604

O’Leary, M. (2020). Classroom Observation: A Guide to the Effective Observation of Teaching and Learning. New York, NY: Routledge.

Pirard, F., Camus, P., and Barbier, J. M. (2018). “Professional development in a competent system: an emergent culture of professionalization,” in International Handbook of Early Childhood Education, eds M. Fleer and B. van Oers (Dordrecht: Springer), doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0927-7_17

Quaresma, M. L., and Valenzuela, J. P. (2017). “Evaluation and accountability in large-scale educational system in chile and its effects on student’s performance in Urban Schools,” in Second International Handbook of Urban Education, eds W. Pink and G. Noblit (Cham: Springer), 523–539. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-40317-5_29

Rodríguez, J., Leyva, J., and Hopkins, Á (2016). El efecto del Acompañamiento Pedagógico Sobre los Rendimientos de los Estudiantes de Escuelas Públicas Rurales del Perú. MPRA Paper No. 72400. San Miguel de Allende: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Rojas, C., López, M., and Echeita, G. (2019). Significados de las prácticas escolares que buscan responder a la diversidad desde la perspectiva de niñas y niños, Una aproximación a la justicia educacional. Perspect. Educ. 58, 23–46.

Roorda, D. L., Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2020). Don’t forget student-teacher dependency! A Meta-analysis on associations with students’ school adjustment and the moderating role of student and teacher characteristics. Attach. Hum. Dev. 23, 490–503. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2020.1751987

Vezub, L. (2011). Las políticas de acompañamiento pedagógico como estrategia de desarrollo profesional docente. El caso de los programas de mentoría a docentes principiantes. Rev. IICE 30, 103–124. doi: 10.34096/riice.n30.149

Keywords: classroom accompaniment, professional development, co-teaching, teacher training, classroom observation, feedback

Citation: Arrellano R, García LY, Philominraj A and Ranjan R (2022) A Qualitative Analysis of Teachers’ Perception of Classroom Pedagogical Accompaniment Program. Front. Educ. 7:682024. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.682024

Received: 17 March 2021; Accepted: 20 May 2022;

Published: 15 June 2022.

Edited by:

Verónica López, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, ChileReviewed by:

Jacqueline Joy Sack, University of Houston–Downtown, United StatesSeyum Getenet, University of Southern Queensland, Australia

Vanessa Valdebenito, Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

Sherine Akkara, Hindustan University, India

Copyright © 2022 Arrellano, García, Philominraj and Ranjan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Leidy Y. García, bGdhcmNpYUB1dGFsY2EuY2w=

Rodrigo Arrellano

Rodrigo Arrellano Leidy Y. García

Leidy Y. García Andrew Philominraj

Andrew Philominraj Ranjeeva Ranjan1

Ranjeeva Ranjan1