94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ., 11 January 2023

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1057706

This article is part of the Research TopicInsights in Teacher Education: 2022View all 13 articles

The culture of an educational institution is defined as a set of common beliefs and values that closely connect the members of a community. Structural dimensions (space, time, teaching materials, and teaching strategies), social dimensions (relationships among school staff, between teachers and children, and among children), common rituals, and customs and traditions of the school are manifestations of school culture in which it is recognized and becomes visible. The aim of this research is to determine the connection between structural dimensions and social relations in the institution. The research was conducted in 2022 on a sample of 174 primary teachers employed in various schools in the Republic of Croatia. The Questionnaire for the Assessment of the Culture of the Educational Institution was used for data collection. An exploratory factor analysis on the Scale of the State of School Culture, which measured the state of structural dimensions, extracted two factors, based on which two subscales of good metric characteristics were created: organization of educational work and spatial and temporal dimensions. The Scale of the State of Relations in the Institution consists of 13 items and has high reliability. In order to determine the existence of a connection between the structural and social dimensions of school culture, Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated. Moderate to relatively high positive correlations between the examined variables were found, which confirms the intertwining and interdependence of different dimensions of school culture, which significantly determines the quality of life and education of children in the institutional context.

School culture is probably one of the most complex and important concepts in education (Prosser, 1999; Stoll, 1999; Bruner, 2000). The term culture of an educational institution usually refers to the accumulation of many individual values and norms, attitudes and beliefs, rituals, history, traditions, etc., which form unwritten rules about how one should think, feel, behave, and act in a certain educational institution (Veziroglu-Celik and Yildiz, 2018). In addition to the curriculum and structural elements such as spatial-material and temporal dimensions, expectations, ways of solving problems, and decision-making, the concept of institutional culture, in particular, encompasses the social interactions of people, which are, at the same time, largely determined by the culture itself. This is where the culture of an individual ends and grows into the culture of a group of people who work and live together. In every human organization, such as an educational institution, there is an unwritten consensus about what is important to the members of the institution; how they should behave in the institution; how to work; and what, when, how, and where to do something. It is for these reasons that some authors define the culture of an institution as “the way we get things done around here” (Deal and Kennedy, 1983, p. 4, as cited in Hopkins, 2001, p. 155) or as “a lens through which the world is viewed” (Hargreaves, 1999, p. 33) because culture permeates everything that happens in the institution.

Although each institution has a certain set of externally prescribed rules and procedures on a conscious level, the culture of the institution is something completely different and something covert; it is that hard-to-know, unconscious part of the daily life in it. Therefore, the culture of an institution is not made up of explicit norms, so it is not accessible to direct observation, research, and comprehension but is subtly created from unspoken expectations, common beliefs, behavior, unwritten rules, established habits and patterns of behavior, and the social interactions of the members of the institution (Chung et al., 2019). Thus, each educational institution has its own, unique culture that makes it special, and by which it differs from all the others. Therefore, for the purposes of this article, the culture of an educational institution is defined as a set of common beliefs and values that closely connect the members of a community and is recognizable through the social relations between people, their mutual work, institutional management, the organizational and physical environment, and the degree of focus on continuous learning and research in the educational practice for the purpose of its improvement (Vujičić, 2011).

In order to understand the process of cultural change, it is important to take into consideration the distinction between structure and culture. It is impossible to explore school culture separately from the structure because they are inextricably linked and interdependent, and the relationship between them is dialectical. Structures influence culture, just as culture influences structures. Structures are often regarded as the most basic and profound because they generate cultures that not only allow the structures to work but also justify or legitimize the structures. On the other hand, changes in culture, i.e., value systems and beliefs, can change underlying structures. The two go hand-in-hand and are mutually reinforcing. But culture can only be influenced indirectly, while structures can be changed (Stoll and Fink, 2000). That is the reason why, on a practical level, it is often easier to change structures than cultures. In this sense, Hargreaves (1994) stated that it is not possible to establish productive school cultures without prior changes in school structures that increase the opportunities for meaningful relationships and collegial support between the school staff. Therefore, structural changes should be less focused on the direct impact on curriculum and assessment and more on improving opportunities for teachers to work together. Also, it is difficult to sustain changes in culture without a concomitant change in structure. However, if structures are changed too radically without paying attention to the underlying culture, then one may get the appearance of change (change in structure) but not the reality of change (change in culture) (Hopkins, 2001). Hence, the challenge is that structural changes without concomitant changes in school culture are likely to be superficial, which is a risk associated with all externally driven educational reforms. Therefore, culture change is at least partly achieved through structural change.

Structural dimensions (organization of space and time, teaching materials, and teaching strategies), social dimensions (relationships in the institution between school personnel, between teachers and children, and among children), common rituals, customs, and traditions of the school are manifestations of school culture in which it is recognized and becomes visible (Deal and Kennedy, 1983, as cited in Hopkins, 2001; Schoen and Teddlie, 2008). “Structures are relatively easy to manipulate because they are visible from the outside, but in order to achieve change, one must change the culture that lies behind the existing structures” (Prosser, 1999, p. 40). However, there is a difference between culture and structure: culture refers to the values, attitudes, and beliefs mentioned earlier, while structure refers to the material, physical environment, and the temporal structuring of the activities of children, educators, etc. (Vujičić, 2008). According to author Hargreaves (1999), there is a physical, organizational and social type of structure, while Stoll and Fink (2000) mentioned space, time, roles, and relationships of people in the institution as structural elements. The same authors believe that the culture of an institution cannot be researched separately because it is highly related to the structure and both are interdependent in many ways. A change in the structure without a change in the culture is nothing more than a superficial change. If two educational institutions have a similar structure, they may have different cultures, but cultures can also be formed within certain structures, so that a change in culture is partly achieved by a change in structure (Stoll and Fink, 2000).

When it comes to social relations, Ogbu (1989 according to Vujičić, 2011, p. 21) defined culture as “… the totality of the way of life of a particular human group, as a network and system of accumulated knowledge, customs, values, and patterns of behavior.” Fullan (1999) used the term “living thing” when describing the culture of an educational institution precisely because it is most strongly shaped by the relationships between educators and children within the institution, as well as the relationships between educators and children within the community (Weckström et al., 2020). Prosser (1999) also agrees, stating that culture is a set of reciprocal relationships between all those involved in the educational process and a way of constructing reality. The importance of the reciprocal relationships between all subjects that create the institutional culture is emphasized by many authors (Čamber Tambolaš and Vujičić, 2019; Hewett and La Paro, 2019; Čamber Tambolaš et al., 2020), including Hargreaves (1999), by using the term “lens” through which participants see themselves and also the world around them.

Research studies (Hewett and La Paro, 2019; Hatton-Bowers et al., 2020; Jeon and Ardeleanu, 2020; Ji and Yue, 2020) showed that reciprocal relationships within and outside the institution, sharing attitudes and beliefs, working on curriculum, and collaborative learning are key to change to improve the quality of institutional culture. If the relationships are positive and efforts are made to improve them outside and inside the institution, the culture itself will be positive, as the results of the above research have shown. To change the culture of the institution, its members need to understand it very well, which is supported by the research of authors Veziroglu-Celik and Yildiz (2018), in which educators actively reflected on their own culture of the institution and expressed their opinions and attitudes. They consider group reflections and collaborative learning in the institution to be an even better form of expressing opinions and attitudes that not only bring about personal change and growth for educators but also largely transform the entire culture into a culture of participation in which the kindergarten becomes a learning community. This is evidenced in the research studies of authors Toran and Yagan Güder (2020), Weckström et al. (2020), and Avidov-Ungar et al. (2021), whose research reflects the culture of participation created by creating a context in which collaborative learning and reflective practice were encouraged. The research studies by authors Yang and Li (2019) also demonstrated that the culture of the institution can change in accordance with changes in the curriculum and that several different cultures interacting with each other create an authentic new culture.

The results presented in this article are part of a wider research conducted as part of the scientific research project Hidden Curriculum and the Culture of Educational Institutions of the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Rijeka. The aim of this article was to determine the correlation between structural dimensions and social relations in the institution as dimensions of school culture, as well as their correlation with the sociodemographic variables under consideration. In accordance with the stated goal, the following research tasks were developed:

1. To determine the correlation between the structural dimensions of school culture and social relations in the institution;

2. To determine the differences in teachers' assessments of the current state of structural dimensions in the institution (organization of space, time, teaching materials, and teaching strategies) regarding their level of education and length of service; and

3. To determine the differences in teachers' assessments of the current social relations in the institution regarding their level of education and length of service.

The following research hypotheses were formulated based on the set research tasks:

H1: There is a positive correlation between structural dimensions and social relations in the institution.

H2: Teachers with a higher level of education (master's degree) evaluate the current state of the structural and social dimensions of school culture more positively than teachers with a lower level of education (bachelor's degree).

H3: Teachers with longer lengths of service evaluate the current state of the structural and social dimensions of school culture more positively than teachers with shorter lengths of service.

It is assumed that teachers' assessments of the current state of the structural dimensions of school culture are positively correlated with their assessments of social relations in the institution, in such a way that in those schools where teachers assess interpersonal relations in the collective as being of higher quality and more focused on cooperation, the organization of the structural dimensions of school culture (space, time, teaching materials, and teaching strategies) is to a greater extent in accordance with the contemporary (co)constructivist understanding of education, according to which structures promote communication, discussion, and collaborative learning between all school members involved in the educational process.

The research was conducted at the beginning of 2022 on a convenient sample of 174 primary teachers employed in various schools in the Republic of Croatia. In Croatia at the time, due to the implementation of epidemiological measures in schools and kindergartens with the aim of suppressing the spread of COVID-19 infection in accordance with the requirements of the Croatian Institute of Public Health, access to external actors to schools and kindergartens was restricted. Therefore, the research was conducted online via Google Forms. In order to include in the research as many primary teachers as possible, the researchers contacted school principals by e-mail with information on the implementation of the research and a request to inform all employed teachers in their institution and send them a link to the online survey. The list of all elementary schools in the Republic of Croatia, to which we sent an invitation to participate in the research, was prepared on the basis of data from the Ministry of Science and Education. This suggests that the survey sample cannot be considered representative but rather convenient, thus, it is important to take this limitation into account when interpreting the results obtained.

The Questionnaire for the Assessment of the Culture of the Educational Institution was used for data collection, which was designed in 2015 for the needs of the research project Culture of the Educational Institution as a Factor of Co-construction of Knowledge at the University of Rijeka (grant number: 13.10.2.2.01). Numerous authors, such as Rosenholtz (1989, according to Stoll and Fink, 2000), Hopkins et al. (1994), Hargreaves (1995), Bruner (2000), and Stoll and Fink (2000) are concerned with the study and typology of school culture and offer a considerable number of different, well-developed typologies of school culture based on different initial criteria. For example, the model of school cultures by Stoll and Fink (2000) based on the dimensions of school effectiveness and school improvement represents a finely developed typology, as does the model by Hargreaves (1995) based on completely different dimensions explained in the areas of social cohesion and social control. Hopkins et al. (1994) built their model of school culture on the dimensions of school effectiveness and the degree of dynamism of the quality improvement process. In their model of school culture, Schoen and Teddlie (2008) listed the following dimensions: professional orientation, organizational structure, quality of the learning environment, and student-centered focus. Schein (1992) pointed out that organizational culture manifests itself at three different levels: artifacts, espoused values and beliefs, and basic assumptions. From the above, it is clear that there are a variety of typologies for the culture of an educational institution, with some similarities and differences among them, which is a consequence of the different initial criteria or dimensions on which these typologies were built. In addition, there is considerable overlap in definitions of school culture and school climate by different researchers, even within the same research tradition (Schoen and Teddlie, 2008). From the above, it is clear what challenges researchers face when attempting to operationalize the concept of the culture of an educational institution, and the questionnaire used in the research presented in this article is one of the possible ways to do so.

Structural dimensions of school culture were operationalized in this study through four aspects: organization of space, time, teaching materials, and teaching strategies. Items examining the current state of aforementioned aspects in the institution are grouped in the Scale of the State of School Culture. The respondents' greater adherence to all items in the mentioned Scale indicates that the shaping and organization of the structural dimensions of school culture in a certain institution are approached from the position of socio-constructivist theory, whereby attention is directed to the organization of a flexible time schedule and school environment that will encourage collaborative and active learning of all involved, and where it will strive for the greatest possible integration of teaching subjects and teaching contents.

Furthermore, social relations as a dimension of school culture were operationalized in this study through three aspects: relations among teachers, relations between teachers and professional associates, and relations between teachers and the principal. Items examining teachers' assessments of current relations in the institution are grouped in the Scale of the State of Relations in the Institution. The respondents' greater adherence to all items in the mentioned Scale, except for one (There is a lack of communication between teachers in the collective.), points to the practice of establishing and maintaining quality, respectful, and reciprocal relations in the institution, which is inherent to the positive school culture (Peterson, 2002).

In both scales, the respondents provided answers using a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1—Does not apply at all to 5—Completely applies). The collected data were analyzed in the statistical program SPSS. There were no missing data in the database because the research was conducted through an online survey, which did not give participants the opportunity to skip/not answer the question (except for questions related to sociodemographic characteristics), i.e., they could not continue with completing the survey if they did not answer the previous question.

Possible biases in participants' responses due to IER (insufficient effort responding) or CR (careless responding) were attempted to be prevented in several ways. The introductory invitation to participate in the survey at the beginning of the online questionnaire was written in a personal rather than formal style to convey a sense of the researchers' appreciation for the respondents and their genuine interest in what the respondents had to say. In this invitation, the importance of research to the field of school culture was explained in detail to the respondents and the importance of their involvement in completing the questionnaire was emphasized. They were also given the opportunity to contact the researchers if they wanted additional clarification. They were promised that they would be informed about the obtained research results by forwarding the results to schools that express their interest.

A descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic variables of the sample showed that 174 teachers participated in the research, 166 of whom are women, 6 men, and 2 respondents did not specify their gender. The average age of the respondents is 48 years (M = 48.2, SD = 9.8), ranging from 24 to 64 years, and the average length of service is 24 years (M = 23.92, SD = 10.98), ranging from a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 44 years of service. The largest number of the respondents completed graduate studies and obtained a university degree (N = 99, i.e., 56.9%), followed by 37.4% of respondents (N = 65) with completed college, professional, or undergraduate studies (bachelor's degree), and 2.9% of the respondents completed doctoral studies (Ph.D.). Nevertheless, 2.9% of them did not answer about their completed level of education. Due to the reform of initial teacher education in the Republic of Croatia, the diversity of primary teachers' educational levels is present in the sample. From the late 1970s until the introduction of the Bologna process into the higher education system in the academic year 2005/2006, there were regular changes in the level and type of teacher study programs in Croatia. The biggest change in initial teacher education in Croatia took place in 1992 with the transition from a 2-year post-secondary associate degree to a 4-year college (bachelor) degree (Uzelac et al., 2003). With the start of the implementation of the Bologna process, primary teacher study programs changed to Integrated undergraduate and graduate study of primary school education lasting 5 years.

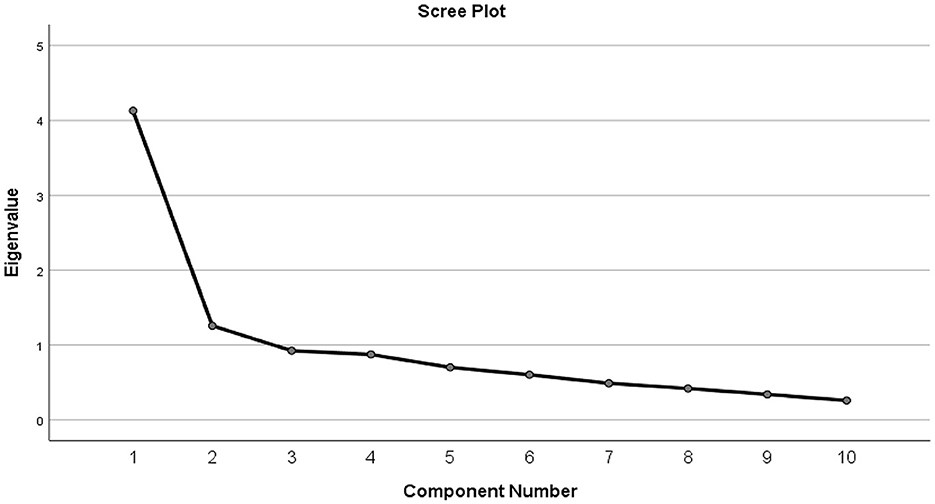

An exploratory factor analysis using the principal component (PC) method with direct oblimin rotation was performed to explore the latent structure of the Scale of the State of School Culture (10 items). The adequacy of the correlation matrix for factorization was verified using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin coefficient (KMO = 0.820) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 = 568.358, df = 45, p < 0.001). Based on the Kaiser-Guttman criterion (eigenvalue >1), and the scree plot criterion (Figure 1), two components were extracted, explaining 53.85% of the variance of scale results, which is consistent with the desired 50% limit of the percentage of the variance explained for the component analysis (Nunnaly and Bernstein, 1994). The results of the performed principal component analysis (component loadings and communalities, eigenvalue, and percentage of the explained variance) are shown in Table 1. The value of 0.3 was taken as the limit of an acceptable component loading value (Pett et al., 2003) so that the items with the same or greater component loading (≥0.3) were included in the component. Table 1 shows that two items (42. and 43.) are saturated on both components. However, these items substantively belong to the first component, and their loadings on the second component are also low (< 0.35), thus, they were retained.

Figure 1. Scree plot for the principal component analysis of the Scale of the State of School Culture.

The obtained results of the principal component analysis indicate that it is reasonable to calculate the linear composite of subscales, i.e., the total average result on each subscale, which is expressed as the sum of the corresponding item response divided by the number of items. It is observable from Table 1 that the first component is saturated with 6 items, pointing to the way of organizing the entire educational work in the school and applied teaching strategies (e.g., project-based learning), while the second component is saturated with four items, reflecting the way of organizing space and time for learning in school. Based on the components described, two subscales were created: (1) Organization of educational work (Cronbach's alpha = 0.82) and (2) Spatial and temporal dimensions (Cronbach's alpha = 0.67). The reliability coefficient of internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) suggests high reliability of the first subscale and acceptable marginal reliability of the second subscale. Although a frequently cited acceptable range of Cronbach's alpha is a value of 0.70, its interpretation is muddled with a lack of agreement regarding the appropriate range of acceptability. Some authors (Cho and Kim, 2015) argued that rather than a universal standard, the appropriate level of reliability is dependent on how a measure is being applied in research. Hair et al. (2010) noted that while a value of 0.70 is generally agreed upon as an acceptable value, values as low as 0.60 may be acceptable for exploratory research, as is the research presented in this article. Additionally, George and Mallery (2003, p. 231) suggested a tiered approach consisting of the following: “≥0.9—Excellent, ≥0.8—Good, ≥0.7—Acceptable, ≥0.6—Questionable, ≥0.5—Poor, and ≤ 0.5—Unacceptable.” While researchers disagree on the appropriate lower cut-off values of Cronbach's alpha, some researchers (Cortina, 1993; Cho and Kim, 2015) warn against applying any arbitrary or automatic cut-off criteria. Rather, it is suggested that any minimum value should be determined on an individual basis based on the purpose of the research, the importance of the decision involved, and/or the stage of the research. Besides that, it is important to be aware that decisions about scale adequacy should not be made based solely on the level of Cronbach's alpha, and that the adequate level of reliability depends on the specific research purpose and importance of the decision associated with the scale's use. Therefore, in this study, the decision was made to keep the obtained subscale with a marginally acceptable value of Cronbach's alpha, but with a warning about the importance of careful examination and interpretation of the results obtained by the subscale, taking into account the possibility of the existence of some additional factors in the data structure, which should be given a theoretical framework.

The descriptive data for the subscales are shown in Table 2. Correlations of each item with the total result on both subscales are relatively high. Partitioning would not significantly increase the reliability of the subscales, and, for this reason, all items were retained on both subscales.

In order to examine the relations in the educational institution at all levels (among teachers, between teachers and professional associates, and between teachers and the principal), the Scale of the State of Relations in the Institution was used, which consists of 13 items. The Scale was previously used in several studies (Pejić Papak et al., 2017; Vujičić and Čamber Tambolaš, 2017, 2019a,b; Vujičić et al., 2018; Čamber Tambolaš and Vujičić, 2019), on different samples and in three different countries (Croatia, Slovenia, Serbia), and, in all contexts, it showed high reliability, with Cronbach's alpha value of 0.83 and higher. For this reason, in the statistical data analysis of this research, the reliability coefficient of the internal consistency Cronbach's alpha was calculated and showed high reliability of the Scale (0.92). The descriptive data for the Scale of the State of Relations in the Institution are shown in Table 3.

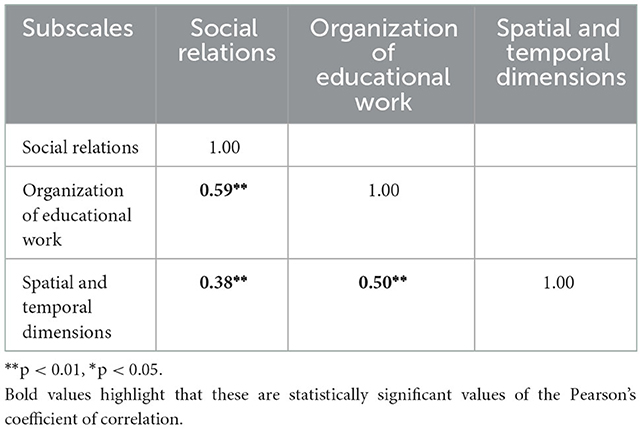

In order to determine the existence of a connection between the structural and social dimensions of school culture, Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) were calculated between the subscales of social relations, organization of educational work, and spatial and temporal dimensions.

Statistical analysis showed that all three mentioned subscales are positively correlated with each other (moderate to relatively high), ranging from 0.38 to 0.59. Table 4 shows that both subscales of the structural dimensions of school culture (organization of educational work and spatial and temporal dimensions) have a relatively high positive correlation (r = 0.50, p < 0.01). This means that the more the organization of the entire education of work in the school is directed toward encouraging a socio-constructivist approach to learning in which the importance of the active role of students in the process of creating knowledge is emphasized, the more flexible the organization of space and time for learning and more adaptable to the specific interests of students.

Table 4. Pearson's coefficient of correlation between social and structural dimensions of school culture.

The assessment of the quality of relationships between people in the institution, which represent the operationalization of the social dimension of school culture, has a statistically significant positive correlation with both subscales of the structural dimensions of school culture. The quality of relationships in the institution has a relatively high-positive correlation (r = 0.59, p < 0.01) with the organization of educational work in the school. This means that the higher the quality of teachers' mutual relationships, the more inclined they are to apply modern teaching methods in the organization of educational work methods and strategies, such as project-based learning, integrated learning, and research-based learning. Also, the quality of relationships in the institution has a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.38, p < 0.01) with the spatial and temporal dimensions. This indicates that the more teachers assess the relationships in the collective as positive, the more flexible their shaping of the space and time schedule of living in school and more adapted to the interests and needs of students with the aim of stimulating the learning process and active creation of knowledge.

Based on the presented results of Pearson's correlation coefficient, the first research hypothesis about the positive relationship between structural dimensions and social relations as dimensions of school culture is confirmed.

In order to examine the existence of differences in the assessments of the surveyed teachers about the structural and social dimensions of school culture regarding their level of education, i.e., the differences in assessments between teachers who obtained a college degree (N = 65) and teachers who obtained a university degree (N = 99), a series of t-tests for independent samples was performed on the obtained subscales: social relations, organization of educational work, and spatial and temporal dimensions.

A statistically significant difference was obtained in the average score on the spatial and temporal dimensions scale (t = 2.28, df = 160, p < 0.05), whereby teachers with a college degree have a higher score (M = 3.41, SD = 0.82) compared with teachers with a university degree (M = 3.10, SD = 0.87). The results point to the conclusion that teachers with a lower level of education (college) consider the organization of the spatial and material environment and time schedule in their school to be more flexible and to a greater extent aligned with the educational interests and needs of students than teachers with a completed higher level of education (university). However, the low effect size index η2 = 0.031 (Petz et al., 2012) suggests that educational level can explain only 3.1% of the variance in teachers' assessments of flexibility in organizing the spatial and material environment and time schedule in the schools. This means that there are obviously some other independent variables besides the stated level of education that have a much stronger influence on teachers' assessment of the organization of space and time for learning in school.

On the other two analyzed subscales (social relations and organization of educational work), no statistically significant differences were obtained regarding the level of education of the surveyed teachers, which means that there is no difference in the assessments of the quality of interpersonal relations in the institution and in the assessments of the strategies used in the organization of educational work in the school between teachers with obtained college and university degree.

Based on the presented results of t-tests for independent samples, the second research hypothesis about the more positive assessments of the current state of structural and social dimensions of school culture by teachers with higher educational levels (master's degree) compared to teachers with lower educational levels is rejected.

In order to examine whether teachers' length of service is significantly correlated with the result on the subscales social relations, organization of educational work, and spatial and temporal dimensions, Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) were calculated. No statistically significant correlation was obtained between the investigated variables, which means that teachers' length of service is not related to their assessments of the quality of relations in the institution, as well as to their assessments of the current state of the structural dimensions of the school culture in terms of the organization of educational work, used learning and teaching strategies, spatial and material environment, and the time schedule of activities at school. Based on the results presented, the third research hypothesis about the more positive assessments of the current state of structural and social dimensions of school culture by teachers with longer service time compared to teachers with shorter service time is rejected.

It is clear that the level of education and length of work service have an almost negligible, if not no, influence on teachers' assessment of the state of the various dimensions of school culture, and that these are determined to a much greater extent by some other factors, such as the frequency and forms of professional development in which teachers are involved, the number of opportunities to think about, reflect on and discuss with colleagues the culture of the institution in which they work, and ways to improve its quality.

Statistical analysis showed that all three analyzed subscales of structural and social dimensions of school culture are in positive, moderate to relatively high correlations with each other. Two subscales of the structural dimensions of school culture (organization of educational work and spatial and temporal dimensions) were expected to have a relatively high-positive correlation (r = 0.50, p < 0.01). Such a finding confirms that the efforts and actions of the school staff aimed at greater flexibility in the shaping of the spatial and temporal institutional context in order to support the individual ways and pace of learning of different students as adequately as possible are accompanied by such an organization of the teaching process that is student-centered in terms of adapting the content learning and teaching methods to their specific needs and interests.

The quality of relationships in the institution, which represent the operationalization of the social dimension of school culture, has a relatively high-positive correlation (r = 0.59) with both subscales of the structural dimensions of school culture. This leads to the conclusion that the higher the quality of teachers' mutual relations at school, the more inclined they are to apply modern teaching methods and strategies in the organization of the teaching process, as well as flexibility in shaping the space and time schedule of life in the institution. The implementation and application of the mentioned modern teaching methods and teaching strategies at school, such as project learning, integrated learning, and research-based learning, presuppose a high level of teacher autonomy and cooperation, but also of all other stakeholders in the teaching process (students, professional associates, parents, and local community) in making decisions about the methods, directions, and intensity of the learning process, which implies a high level of engagement, but also the personal responsibility of all involved for the success of the learning process of children and adults. This means that such synergy can come to life only in a social environment where helpful and supportive interpersonal relationships prevail, which is confirmed by the results of the conducted research.

Moderate to relatively high-positive correlations found between structural dimensions of school culture and social relations in the institution confirm the interconnectedness of social and structural dimensions of school culture, which leads to the conclusion that the quality of relations between members of the institution largely determines the structural and organizational aspects of school life, as well as that by working on questioning and changing them, the dynamics and quality of people's relationships in the institution are affected. The above speaks in favor of the intertwining, interdependence, and interaction of different dimensions of school culture.

The research results showed that socio-demographic variables, such as the level of education and length of service, are not closely related to teachers' assessments of school culture dimensions. It is somewhat understandable that some other variables, such as teachers' professional development, have a greater influence on the assessment of the quality of relationships in the collective, as well as on the shaping of the structural dimensions of the school context, especially those modalities that are aimed at encouraging the interpersonal and intrapersonal competences of the teachers themselves, and in which they are active participants in (self)reflection and (self)change. Therefore, future studies should focus on determining the relationship between teachers' assessments of school culture and some other factors, such as the level of support teachers receive from the institution's leadership or the ways and forms of professional development in which teachers are involved. We advocate for those forms of professional development that have transformational, rather than merely informational potential because positive change is only possible through constant questioning and reflecting on one's educational reality. Professional development of teachers represents a feature of improving the quality of an educational institution, i.e., its culture, as it presupposes a strong connection between the members of the institution and emphasizes the interdependence of their actions and the responsibility for them.

In addition, it would be beneficial in future research to investigate what else influences the culture of an educational institution, especially studies such as those by Jančec et al. (2022), who found that the empathy of the members of the institution has no influence on its culture, while the influence of other important educational forces of the educational process, such as personality traits, attitudes, and other important indirect and direct factors that participate in the process in the institution and the classroom, remains unexplored. Also, using the questionnaire from this study for some future research conducted in other social, cultural, and educational contexts provides an opportunity for additional testing of the validity and reliability of the measuring instrument used to assess the culture of the educational institution.

One of the main limitations of this study, due to which the results obtained should be considered with some caution, is the small sample size and the fact that it is a convenient sample, so it has a low degree of representativeness or possibilities of generalization. In school climate research, the research problem is approached from a psychological perspective with the usual use of quantitative diagnostic instruments, while in school culture research, an anthropological perspective dominates, where the data sources are typical of a qualitative approach (narrative statements, interviews, videos, etc.) (Schoen and Teddlie, 2008). This also means that the concepts of school climate and school culture, although similar, come from different research traditions and research communities. In this sense, despite the obstacles encountered in the research (low respondent response rate) and the lack of generalization possibilities, the significance of the results obtained lies in the empirical confirmation of the relationship between the structural and social dimensions of school culture, which is mainly discussed in theoretical discussions about school culture but has either not been studied at all or minimally studied and identified through quantitative methodological approaches.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee for Scientific Research of the Faculty of Teacher Education University of Rijeka, Croatia. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This study was funded as a part of scientific research project Hidden Curriculum and Culture of Educational Institutions [grant number uniri-mladi-drustv-20-24] within the UNIRI Program Support for the Projects of Young Scientists by the University of Rijeka, Croatia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Avidov-Ungar, O., Merav, H., and Cohen, S. (2021). Role perceptions of early childhood teachers leading professional learning communities following a new professional development policy. Leadership Policy Schls. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2021.1921224

Čamber Tambolaš, A., and Vujičić, L. (2019). “Early Education Institution as a Place for Creating a Culture of Collaborative Relationships,” in Educational Systems and Societal Changes: Challenges and Opportunities, eds J. Mezak, M. Drakulić, and M. Lazzarich (Rijeka: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Teacher Education), 69–71. Available online at: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1048529 (accessed September 1, 2022).

Čamber Tambolaš, A., Vujičić, L., and Badurina, K. (2020). “Relationships in the educational institution as a dimension of kindergarten culture: a narrative study,” in ICERI2020 Proceedings: 13th International Conference of Education, Research and Innovation, eds L. Gómez Chova, A. López Martínez, and I. Candel Torres (Valencia, Spain: IATED Academy) 6604–6614. doi: 10.21125/iceri.2020.1410

Cho, E., and Kim, S. (2015). Cronbach's coefficient alpha: well known but poorly understood. Organiz. Res. Methods 18, 207–230. doi: 10.1177/1094428114555994

Chung, K.-S., Cha, J.-R., and Kim, M. (2019). Relationship-oriented organizational culture and educational community-building competence of early childhood teachers in korea: the mediating role of teacher empowerment. Int. J. Early Childh. Educ. 25, 1–18. doi: 10.18023/ijece.2019.25.1.001

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 78, 98–104. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.98

George, D., and Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 11.0 Update, 4th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., and Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson.

Hargreaves, A. (1994). Restructuring restructuring: postmodernity and the prospects for educational change. J. Educ. Policy 9, 47–65. doi: 10.1080/0268093940090104

Hargreaves, D. (1995). School culture, school effectiveness and school improvement. Schl. Effect. Schl. Improv. 6, 23–46. doi: 10.1080/0924345950060102

Hargreaves, D. (1999). “Helping practitioners explore their school's culture,” in School Culture, ed J. Prosser (London: P.C.P.), 48–65. doi: 10.4135/9781446219362.n4

Hatton-Bowers, H., Howell Smith, M., Huynh, T., Bash, K., Durden, T., Anthony, C., et al. (2020). “I will be less judgmental, more kind, more aware, and resilient!”: early childhood professionals' learnings from an online mindfulness module. Early Childhd. Educ. J. 48, 379–391. doi: 10.1007/s10643-019-01007-6

Hewett, B. S., and La Paro, K. M. (2019). organizational climate: collegiality and supervisor support in early childhood education programs. Early Childh. Educ. J. 48, 415–427. doi: 10.1007/s10643-019-01003-w

Hopkins, D., Ainscow, M., and West, M. (1994). School Improvement in an Era of Change. London: Cassell.

Jančec, L., Čamber Tambolaš, A., and Vujičić, L. (2022). “Hidden curriculum and culture of an educational institution,” in The 2nd International Scientific and Art Conference Contemporary Themes in Education–dedicated to Prof. Milan Matijević (Zagreb: Institute for Scientific Research and Arts Work of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, and the Faculty of Teacher Education, University of Zagreb). Availible online at: https://hub.ufzg.hr/books/zbornikbook-of-proceedings-stoo2/page/skriveni-kurikulum-i-kultura-odgojno-obrazovne-ustanove

Jeon, L., and Ardeleanu, K. (2020). Work climate in early care and education and teachers' stress: indirect associations through emotion regulation. Early Educ. Dev. 31, 1031–1051. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1776809

Ji, D., and Yue, Y. (2020). Relationship between kindergarten organizational climate and teacher burnout: work–family conflict as a mediator. Front. Psychiatry 11, 408. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00408

Pejić Papak, P., Vujičić, L., and Čamber Tambolaš, A. (2017). “Preschool teacher as a reflective practitioner and changing educational practice,” in The 1st International Conference “Initial Education and Professional Development of Preschool Teachers – State and Perspectives”, eds D. Pavlović Breneselović, Ž. Krnjaja, and T. Panić (Sremska Mitrovica: Preschool Teacher Training and Business Informatics College – Sirmium), 118–121. Available online at: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1063763 (accessed September 1, 2022).

Peterson, K. (2002). Positive or negative? J. Staff Dev. 23, 10–15. Available online at: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ654750

Pett, M. A., Lackey, N. R., and Sullivan, J. J. (2003). Making Sense of Factor Analysis. London: SAGE Publications. doi: 10.4135/9781412984898

Petz, B., Kolesarić, V., and Ivanec, D. (2012). Petzova statistika: osnove statističke metode za nematematičare [Petz statistics: the basics of statistical methods for non-mathematicians]. Jastrebarsko: Naklada Slap.

Rosenholtz, S. J. (1989). Teachers' Workplace: The Social Organization of Schools. New York, NY: Longman.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd Edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schoen, L., and Teddlie, C. (2008). A new model of school culture: a response to a call for conceptual clarity. Schl. Effect. Schl. Improv. 19, 129–153. doi: 10.1080/09243450802095278

Stoll, L. (1999). “school culture: black hole or fertile garden for school improvement?” in School Culture, ed J. Prosser (London: P.C.P.), 30–47. doi: 10.4135/9781446219362.n3

Toran, M., and Yagan Güder, S. (2020). Supporting teachers' professional development: examining the opinions of pre-school teachers attending courses in an undergraduate program. Pegem Egitim ve Ögretim Dergisi 10, 809–868. doi: 10.14527/pegegog.2020.026

Uzelac, V., Pejčić, A., Pinoza Kukurin, Z., and Sam Palmić, R., (eds.). (2003). Teacher Education College Rijeka. Rijeka: University of Rijeka, Teacher Education College.

Veziroglu-Celik, M., and Yildiz, T. G. (2018). Organizational climate in early childhood education. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 6, 88–96. doi: 10.11114/jets.v6i12.3698

Vujičić, L. (2008). Kultura odgojno-obrazovne ustanove i kvaliteta promjena odgojno-obrazovne prakse. Pedagogijska Istraživanja, 5, 7–20.

Vujičić, L. (2011). Istraživanje kulture odgojno-obrazovne ustanove [Exploring the Culture of Educational Institution]. Zagreb: Mali profesor.

Vujičić, L., and Čamber Tambolaš, A. (2017). Professional development of preschool teachers and changing the culture of the institution of early education. Early Child Dev. Care 187, 1583–1595. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1317763

Vujičić, L., and Čamber Tambolaš, A. (2019a). “Educational paradigm and professional development: dimensions of the culture of educational institution,” in Implicit Pedagogy for Optimized Learning in Contemporary Education, eds J. Vodopivec Lepičnik, L. Jančec, and T. Štemberger (USA: IGI Global), 77–103. doi: 10.4018/978-1-5225-5799-9.ch005

Vujičić, L., and Čamber Tambolaš, A. (2019b). “The culture of relations - a challenge in the research of educational practice in early education institutions,” in Quality of Education: Global Development Goals and Local Strategies, eds V. Orlović Lovren, J. Peeters, and N. Matović (Beograd: Institute for Pedagogy and Andragogy, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia; Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy Centre for Innovation in the Early Years, Ghent University, Belgium), 137–153. Available online at: https://www.bib.irb.hr/1048416 (accessed September 1, 2022).

Vujičić, L., Pejić Papak, P., and Valenčić Zuljan, M. (2018). Okruženje za učenje i kultura ustanove [The Learning Environment and Culture of the Institution]. Rijeka: Učiteljski fakultet Sveučilišta u Rijeci.

Weckström, E., Karlsson, L., Pöllänen, S., and Lastikka, A. (2020). Creating a culture of participation: early childhood education and care educators in the face of change. Children Soc. 35, 503–518. doi: 10.1111/chso.12414

Keywords: institutional context, primary teacher, relationships, school culture, structural dimension of school culture

Citation: Čamber Tambolaš A, Vujičić L and Jančec L (2023) Relationship between structural and social dimensions of school culture. Front. Educ. 7:1057706. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1057706

Received: 29 September 2022; Accepted: 14 December 2022;

Published: 11 January 2023.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Jairo Rodríguez-Medina, University of Valladolid, SpainCopyright © 2023 Čamber Tambolaš, Vujičić and Jančec. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lucija Jančec,  bHVjaWphLmphbmNlY0B1ZnJpLnVuaXJpLmhy

bHVjaWphLmphbmNlY0B1ZnJpLnVuaXJpLmhy

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.