- 1Department of Counseling Psychology and Special Education, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

- 2Office of Research and Development, BYU Marriott School of Business, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

One of the roles of reflection is to support teachers in implementing new instructional techniques. Collaborative reflection is a promising tool in addressing reluctance and resistance to implementing instructional techniques. This qualitative study describes how literacy coaches incorporated collaborative reflection with high implementing and initially resistant-low implementing teachers in four rural, low resourced school districts in the southeastern, United States. The findings indicated that as coaches incorporated collaborative reflection, initially resistant-low implementing teachers were more likely to share instructional needs with coaches, feel more confident in implementing the literacy intervention and express less resistance to coaching. Additional research is needed to understand collaborative reflection more fully as an aspect of the coach-teacher relationship.

Introduction

Over the years, researchers have argued that reflection supports teachers in developing knowledge and implementing new instructional techniques (Attard, 2012; Daniel et al., 2013; Lambert et al., 2014). School leaders interested in change effort should recognize the utility of reflection in effective professional development (Knight, 2009). When leaders utilize reflection to support teacher learning and development, they should recognize that using it successfully requires two things. They need to provide opportunity for interaction with a “knowledgeable other” (Clarà et al., 2019, p. 176), and they need to organize collaboration with a facilitator (Gelfuso and Dennis, 2014; Moore-Russo and Wilsey, 2014; Foong et al., 2018; Clarà et al., 2019). Engaging teachers in the process of self-reflection is enhanced by communicating with a more knowledgeable other who pushes teachers to think deeply about varying perspectives, consider social and ethical contexts, and initiate new ways of thinking and being (Çimer et al., 2013). As teachers engage in reflection they develop new knowledge and understanding of themselves as agents of change within their classrooms and usually take up new practices or refine current ones.

Collaborative reflection

While most literature centers on individual reflection, Clarà et al. (2019) promote collaborative reflection since the potential for teachers to learn through reflection is enhanced by collaboration. This is especially so when teachers become immersed in and energized about new learning through coaching scenarios (Foong et al., 2018). Collaborative reflection refers to the process by which members of a community reflect together through social interactions and the outcomes of this process (Jiang and Zheng, 2021, p. 248). Collaborative reflection requires greater skill than individual reflection to be successful (Prilla and Renner, 2014). Individual reflection is an isolated activity and the person who is doing the reflection, even when they take a critical stance, can only use their own thinking and understanding to interrogate the actions they view. In contrast, collaborative reflection requires sharing information, negotiating resistance and conflict, respecting individual differences, planning instruction to meet needs of others, inspiring trust and affecting strong commitment in all teachers (Katz and Earl, 2010). Thus, collaborative reflection incorporates active self-reflection, effective communication, as well as the ability to accept and utilize critique and provide advice to others in appropriate ways (Çimer et al., 2013; Clarà et al., 2019).

Coaching and collaborative reflection as part of effective professional development

Literacy coaching as part of professional development models has become a successful way to enhance the instructional abilities of classroom teachers (Desimone and Pak, 2017) and has spread to nearly every school district in the country as a strategy for increasing early elementary classroom teacher skills in helping struggling readers who may be poor, minoritized, or English Learners (ELs) (Amendum et al., 2018; Desimone et al., 2019). Teacher coaching can lead to growth in teacher learning, changes in teacher practice, and improvement in student outcomes (Ali et al., 2018; Fabiano et al., 2018; Kraft and Blazar, 2018; Kraft et al., 2018; Ennis et al., 2020; Pianta et al., 2021). While coaching results in positive instruction outcomes, the magnitude of the outcomes varies based on several factors including the type of coaching and the size of the coaching program (Kraft and Blazar, 2018; Kraft et al., 2018). Of note, Pianta et al. (2021) observed that teachers who engaged in more coaching cycles demonstrated greater instructional improvements than their counterparts with fewer coaching sessions. the infusion of collaborative reflection as part of the coaching cycle can foster teacher growth and development (Foong et al., 2018).

Coaches, by the nature of their position within the teacher’s social context, are well suited to cultivate an attitude of “accompanying” a teacher through the journey of reflection, self- discovery and growth (Foong et al., 2018). Creating an effective atmosphere that promotes positive collaborative reflection requires coaches to be more than good conversationalists. Coaches must be able to not only identify areas where job performance could improve, but also raise awareness of ideas, consequences, and actions which the teacher may not perceive or may ignore. Thus, when coaches take a critical stance, they are able to provide not just critique but also education targeting areas that could be improved or refined. Coaches can use ongoing collaborative reflection times to affirm teacher progress, provide additional encouragement, identify areas, or action teachers may not see, suggest areas for improvement, and support setting goals for next steps (Foong et al., 2018). Coaches must recognize and honor the professionalism of teachers by listening respectfully and modeling and expressing genuine positive regard for the teacher throughout the education and reflection process (Çimer et al., 2013; Foong et al., 2018). During reflection coaches and teachers can share their observations, experiences, and insights to co-create knowledge that can inform teacher practice. Because the reflection is anchored in real world experiences, coaches can engage teachers with insights and alternative representations of the practice and effectively merge theory with practice (López-de-Arana Prado et al., 2019). In facilitating a time for reflective collaboration, coaches create a set of scaffolds where teachers can engage deeply with their practice and their thinking about it which promotes learning and guides teachers in making steps toward personal and professional growth (Foong et al., 2018).

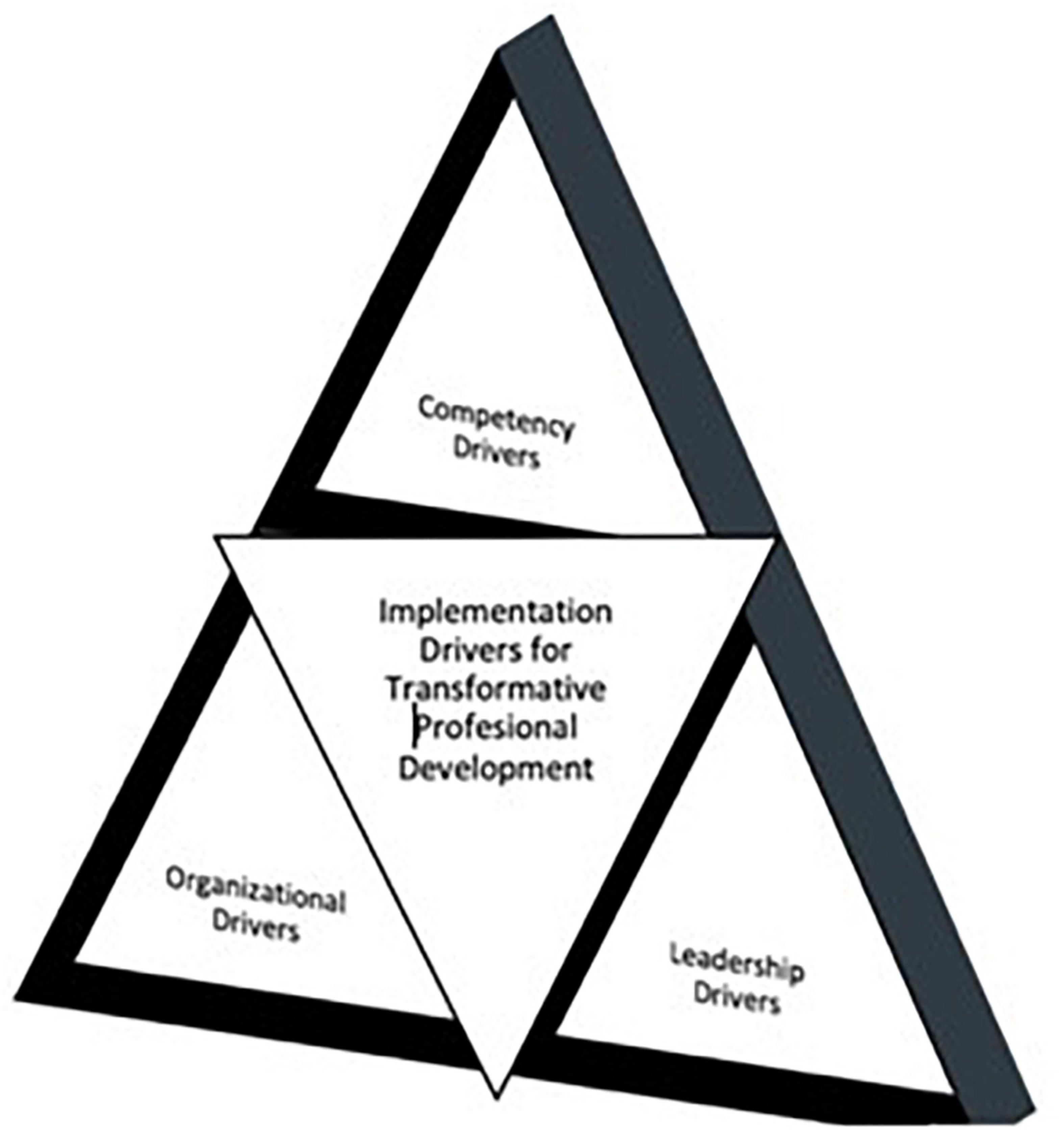

Researchers suggest three categories of implementation drivers that influence whether effective professional development is both successful and sustainable (Fixsen et al., 2005; National Implementation Research Network [NIRN], 2022). The three implementation drivers are Competency, Organization, and Leadership. Competency drivers are mechanisms to develop, improve, and sustain one’s ability to implement an intervention as intended. Organization drivers are mechanisms used to intentionally critique and develop the supports and infrastructures needed to create a hospitable environment for new interventions. Leadership drivers focus on identifying leadership challenges and then seek to provide appropriate strategies for meeting the leadership challenges. These include making decisions, providing guidance, and supporting organization functioning (Fixsen et al., 2005, 2009). Coaching falls within the competency organizational driver (see Figure 1) and is defined as “regular, embedded professional development designed to help teachers and staff use the program or innovation as intended” (NIRM, p. 1). When coaches engage in collaborative self- reflection with the teachers they are supporting, they can provide a context for analysis, goal setting, and support for changes.

Figure 1. Implementation drivers for transformative professional development. Adapted from Fixsen et al. (2013).

Collectively, these drivers are key components that enable implementation of transformative professional development.

Hard and soft coaching models

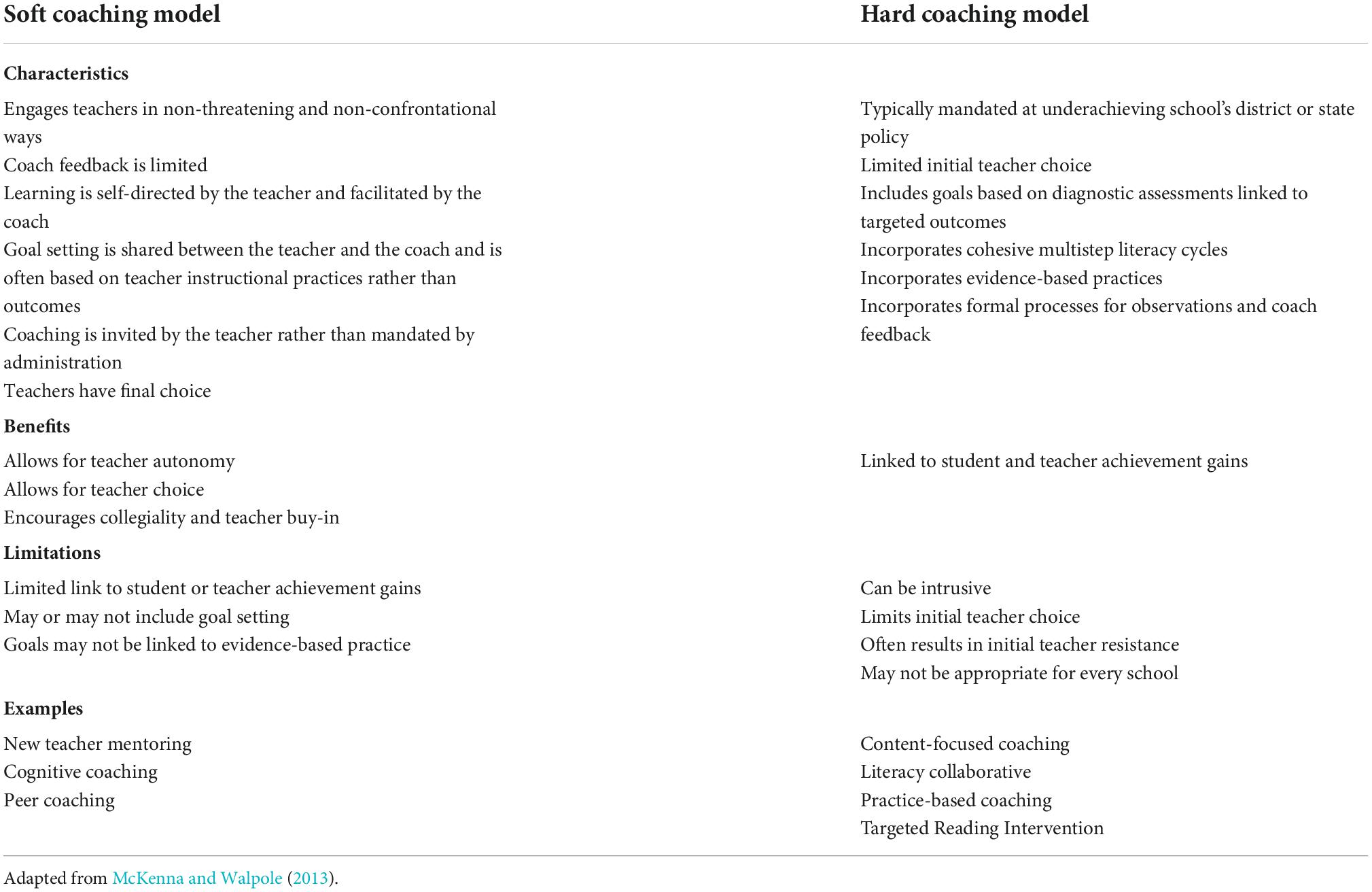

McKenna and Walpole (2013) compared the various models of coaching iterations to a geology scale used to measure hardness in rocks (see Table 1 below). At one end is what they labeled as soft models of coaching. Soft coaching is defined as coaching that is based on unobtrusive coaching practices. Soft models engage teachers in non-threatening and non-confrontational ways wherein the literacy coach often refrains from giving feedback but facilitates the self-directed learning of teachers where teachers have the last word. Soft coaching models usually involve teacher choice implementing an intervention. Examples of soft coaching are (a) mentoring of new teachers, (b) cognitive coaching, and (c) peer coaching (McKenna and Walpole, 2013).

On the other end of the scale are the hard models of coaching. Hard coaching is defined by coaching that assumes the current practices at the school related to proposed interventions are responsible for low achievement and must be adjusted or replaced by new practices. Hard coaching models are characterized by coaching cycles with targeted, specific learning outcomes based on implementation of evidence-based practices (L’Allier et al., 2010; Fox et al., 2011; McKenna and Walpole, 2013). Hard coaching models are typically implemented at underachieving schools and mandated by the school, district, or state with little teacher input. While hard coaching models may allow teachers to help decide when or where they will implement the model, hard coaching rarely allows classroom teachers to choose whether they will be part of the program (McKenna and Walpole, 2013).

Research reports that hard coaching models that use up-front goal setting are more likely to result in substantive achievement gains in students and teachers (Neuman and Cunningham, 2009; Shidler, 2009; Biancarosa et al., 2010; Matsumura et al., 2010; Carlisle and Berebitsky, 2011; Fox et al., 2011; Desimone and Pak, 2017; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2018). Even so, hard up-front coaching models can be intrusive, limit teacher choice, and often result in initial teacher resistance upon implementation (McKenna and Walpole, 2013).

Examples of hard coaching include the following: (a) content-focused coaching (CFC), (b) literacy collaborative (LC), (c) practice-based coaching (PBC), and (d) the Targeted Reading Intervention (TRI) (Biancarosa et al., 2010; Matsumura et al., 2010; Artman-Meeker et al., 2014; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2018).

One study of interest unintentionally compared hard and soft coaching. The purpose of this 3-year study (Shidler, 2009) was to look at the correlation between the time literacy coaches spent coaching teachers and efficacy in literacy instruction and student achievement. Analysis of this study revealed that a significant correlation between literacy coach time in the classroom and student achievement was found for year one only, even though literacy coaches spent more time in teacher classrooms in years two and three of the study. This could be viewed as a baffling outcome. Upon closer examination, however, the researcher described that although literacy coaches spent more time in teachers’ classrooms in years two and three helping teachers with whatever was asked of them, it was only in year one when the literacy coach implemented a hard coaching model that focused on specific goals for efficacy in specific content and teaching methods (Shidler, 2009). This study suggests that the initial teacher resistance may have gone underground and continued in years two or three or more progress would surely have been made. Olson and Craig (2005) talk about these as “cover stories” wherein teachers say what they think those in power (such as coaches) want to hear but then have secret stories about what is really happening.

It is becoming ever clearer that most studies involving coaching that show teacher and/or student achievement gains have implemented a hard, up-front model of coaching. However, these models can be intrusive, and implementation of these harder models often cause initial teacher resistance (Carlisle and Berebitsky, 2011; Walpole and McKenna, 2013).

Approaches that reduce teacher resistance for transformative professional development

In the past, teacher resistance was viewed as a negative characteristic that afflicted teacher leaders (Musanti and Pence, 2010). Many researchers today are beginning to view teacher resistance through a more hopeful lens (Sannino, 2010). Kindred (1999) wrote:

Although resistance is most often considered a sign of disengagement, it can in fact be a form, as well as a signal, of intense involvement and learning. In the simultaneity of negation and expression, it is an active dialog between the contested past and the unwritten future, between practice and possibility (p. 218).

Coaching experts now agree that some amount of teacher resistance should be expected and suggest coaches recognize teachers, because of their profession, are naturally critical of those who would teach them (McKenna and Walpole, 2013). Resistance may naturally occur as teachers wrestle to adjust their teacher identity in response to a coach’s invitation to modify teaching practices (Valoyes-Chávez, 2019). Additionally, resistance may be an outcome of “change fatigue;” teachers, bombarded with an unending stream of novel, sometimes unsupported, teaching approaches, may be skeptical of and resist, yet another, new practice (Orlando, 2014; Jacobs et al., 2018).

According to some, acts of teacher resistance are just good common sense. For e.g., in an analysis of how teachers reacted to an education initiative, the authors found three different responses to the reform. One group immediately embraced the new initiative. A second group included teachers who waited to see how the first group implemented the reform. When the second group observed that the first group was successful, they implemented the reform. A third group presented with profound reluctance to implement the reform due to time constraints and the fear of public disapproval (Tye and Tye, 1993). In describing the reaction of the second group to the reform initiative, the authors concluded: “This group reminds us that we too easily label teachers who do not immediately accept proposed innovation as ‘resistant’ to change. Wanting to see how something works is not resistance, it is simply good common sense” (p. 60). Wanting to see how something works falls under one of the three approaches to reduce teacher resistance which include: (a) results-focused coaching, (b) processes-focused coaching, and (c) relationships-focused coaching.

Results-focused coaching

Some researchers argue that resistance can be reduced through a results-oriented frame, an approach like the Guskey (2002) notion that changes in teachers’ beliefs come about after—rather than before—changes in practice. As teachers gain mastery over new instructional strategies and see positive outcomes, teachers become increasingly willing to implement interventions (Guskey, 2002; Steckel, 2009). During active coaching cycles, results- oriented coaches focus on a few critically important proven and powerful teaching practices to help ensure teacher buy-in and greater student outcomes (Knight, 2009; Steckel, 2009). In the face of resistance, the coach celebrates achievement and movement toward goals, acknowledges alternative views without discounting the evidence of success, and invites motivated teachers to talk about the usefulness of the instructional practice (McKenna and Walpole, 2013). Results- oriented literacy coaches also invite resistant teachers to recount successful experiences during team meetings (Knight, 2019). After active coaching cycles, literacy coaches support teachers to reflect on acquisition of their new learning, evaluate practices, debrief strengths and weaknesses related to effectiveness, and then set new goals (Trivette et al., 2009).

Processes-focused coaching

Some researchers argue that resistance can be reduced through an ordered processes approach to coaching (Elish-Piper and L’Allier, 2010; L’Allier et al., 2010). These types of coaches work to make sure there is coherence of school, district, and school reform policies (Desimone and Pak, 2017). They employ teacher resistance prevention strategies such as starting coaching processes early in the school year to allow time for teachers to become familiar with process steps. They plan active professional development with clearly designed intervention strategies with distinct steps to follow and allow for practice time (Steckel, 2009; Trivette et al., 2009; L’Allier et al., 2010; Lemons et al., 2016; Desimone and Pak, 2017). During active coaching cycles, literacy coaches demonstrate a deep understanding of teaching practices and employ progressive scaffolding using intervention checklists to help guide learning (Knight, 2009; Collet, 2012; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2018). Coaches with a processes-focused frame implement diagnostic coaching which includes reflecting with teachers before offering descriptive feedback to ensure coaching practices match teacher needs to provide transformative support (Domitrovich et al., 2009; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2018).

Relationships-focused coaching

Some researchers argue that coaching models that focus on relationship building and invitational, collaborative frameworks of coaching will minimize resistance (Gallucci et al., 2010; Collet, 2012; Knight, 2019; Cutrer-Párraga et al., 2021). Coaches with a relationship frame employ teacher resistance prevention strategies such as increasing relational trust, treating teachers with respect, recognizing and respecting teachers’ accumulated experiences and expertise, and seeing their ideas as a rich resource (Knowles, 1989; Knight, 2019; Ippolito and Lieberman, 2020). Further, coaches offer teachers choices when possible and communicate clearly that the coach’s role is nonevaluative (Collet, 2012; Knight, 2019; Cutrer-Párraga et al., 2021). Coaches draw on teacher expertise and demonstrate careful listening by signaling teachers have been heard when they question interventions (Knight, 2019). Coaches offer support by refraining from offering research to counter philosophical differences (Al Otaiba et al., 2008; Collet, 2012; McKenna and Walpole, 2013), and instead arranging for active reflection sessions with the teacher to co-plan and seek input about issues and problems (McKenna and Walpole, 2013; Cutrer-Párraga et al., 2022).

Coaches may utilize and prioritize one resistance reduction approach over another, yet a single resistance reduction approach is likely not sufficient to prevent or minimize the disparate causes of teacher resistance for sustained periods of time (Elish-Piper and L’Allier, 2010; Kretlow and Bartholomew, 2010). Rather, it is argued, that the interplay of all three resistance reduction approaches working together minimizes teacher resistance. It is noted that reflection is imbedded within all three resistance reduction approaches (see Figure 2).

Coaching models

Various literacy coaching definitions, models and implementation modalities exist within literacy scholarship (Hathaway et al., 2016). Across modalities, coaching proponents presuppose that: (a) as teachers are primary influencers of student outcomes, fundamental improvements in teacher instruction will result in improved student performances, and (b) empowerment of teachers within a coaching program (e.g., dialog between coaches and teachers replacing workshops and lectures) is more likely to result in sustained teaching practice changes (Connor, 2017).

Contrary to literacy coaching modalities, a student-oriented model removes accountability for student outcomes from the general education classroom teacher. The general education classroom teacher sends struggling readers to specialized teachers for support. This model, while commonly used, can unintentionally disempower classroom teachers and cause them to disengage from struggling readers (Neumerski, 2012). When general education classroom teachers experience movement away from the traditional student-oriented models and encounter accountability for the diverse needs of struggling readers, they may feel overwhelmed or unprepared. Teachers may, understandably, resist a literacy coaching model (Hathaway et al., 2016).

Purpose

This 2-year study investigated the use of collaborative reflection within a relationship-focused coaching frame, in promoting teacher changes in literacy practices. A subset of a larger study, this study focused on data collected from kindergarten teachers and their literacy coaches participating in an early literacy intervention, the Targeted Reading Instruction (TRI; Vernon-Feagans et al., 2018). For more information on the TRI, refer to this website1. Data collection commenced after IRB approval was obtain by the primary author’s university.

Research design rationale

A multiple case study approach was used in this study. Multiple case studies are useful when exploring contextual elements relevant to the phenomena under study (Yin, 2018). The current study was distinctive in that the researchers only began to understand the role of reflection in teachers’ implementing after considering the context provided for such reflection. Ultimately, case study design was selected to allow an in-depth, focused unpacking of the perceptions of focal participants in relation to reflection among high implementers and initially resistant teacher implementers in the study (Stake, 2013). Participants in this study (kindergarten teacher and literacy coach dyads) interacted for a period of 2 years as part of a larger, multi-year literacy intervention study.

Data collection

Typically, within a case study design, data is collected from multiple sources to assist in developing a rich understanding of the case and the phenomenon in question (Yin, 2018). Morrow (2005) suggested that rigorous qualitative data collection involves a search for disconfirming evidence while in the field and recommended comparing disconfirming cases with confirming cases help to assure adequate data collection and an improved possibility of understanding the complexities of the phenomenon being studied. This study gathered data from both initially high and low implementing teachers via semi-structured interviews (participating teachers and literacy coaches), observations of recorded dyad coaching sessions, study intervention communications to participating teachers and coaches, field notes (researchers and coaches), and analytic memos from preliminary data analysis.

Setting

This study was composed of six teachers from four rural elementary schools, in the Southeastern United States. The schools served primarily minoritized students, and all received Title I funding. In previous years, the schools had failed to meet adequate yearly progress.

Teacher participants and study context

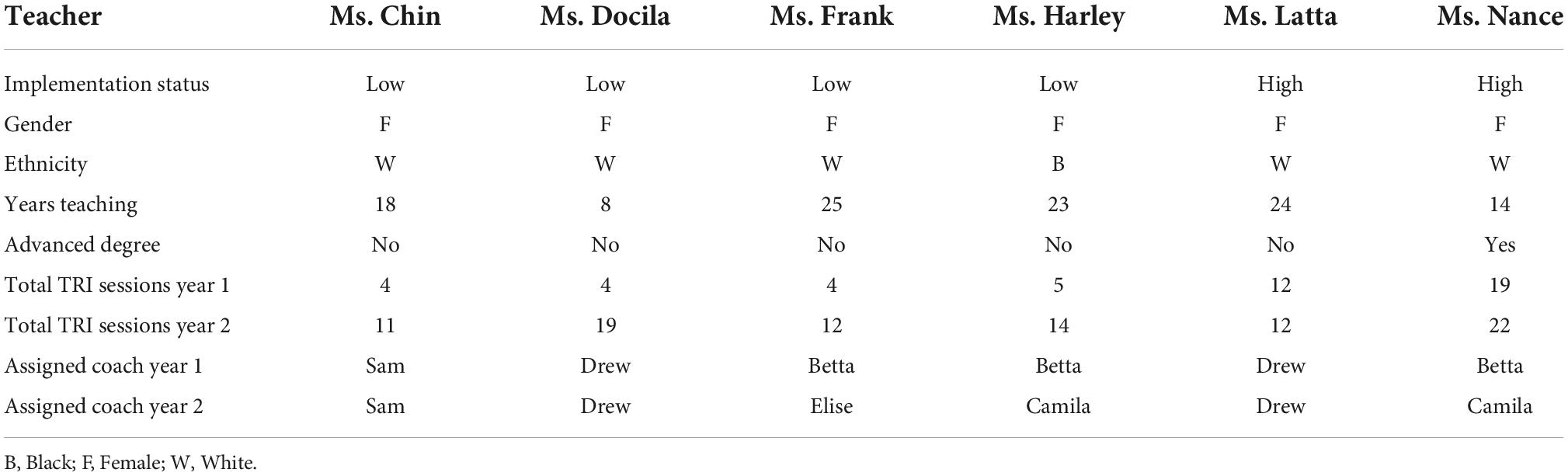

Six veteran teachers, both high and low implementers, were invited to participate in this study. (See Table 2 for information about teacher participants.) As part of the larger study, teachers were expected to implement the TRI daily and participated in weekly literacy coaching sessions. Low implementing, initially resistant teachers in this study were defined as teachers who completed five or fewer coaching sessions over the first academic year of the study. High implementing teachers were teachers who completed twice as many coaching sessions in comparison with their low-implementing counterparts in the first year. All the teacher participants were female and all but one identified as White. On average, the teacher participants had 18 years of teaching experience. At the end of the second year, both high and low implementing teachers increased implementing TRI sessions. The four initial resistors implemented almost triple (or more) the number of sessions as in their first year (Ms. Chin 4 sessions first year to 11 sessions second year; Ms. Docila, 4 sessions first year to 19 second year, Ms. Frank, 4 sessions first year to 12 second year; Ms. Harley 5 sessions first year to 14 second year).

Coach participants

Five literacy coaches (4 female and 1 male) participated in the study. Coaches outside the school districts were invited to participate in the study because of their experience teaching struggling readers. Three coach participants had prior literacy coaching experience, two were certified as literacy coaches and four were doctoral students. On average, the coaches had 11.5 years of teaching experience (range 3−20 years). Additionally, all participant coaches worked with kindergarten teachers for at least one year of TRI implementation.

Teacher training

Prior to the first year of the study, the teacher participants attended a 3-day summer workshop where they met, worked with, and learned from their literacy coaches. Teacher participants were expected to return to their classroom and implement a reading intervention with students selected by the study assessment team. The reading intervention consisted of 15-min one on one instruction sessions, three-four times per week during the academic year. Literacy coaches offered support and scaffolding in weekly coaching sessions via webcam. Coaches provided real time feedback for participating teachers and follow up emails to help teachers match instruction to a student’s most pressing need. Literacy coaches also met weekly with kindergarten teaching teams.

Coach training

Prior to working with a participating teacher, coaches completed an intensive 5-day coaching training. Coaches were instructed in coaching pedagogy and TRI content. During the institute coaches were required to demonstrate via video recording a high level of TRI quality and fidelity in instructing a struggling reader. When coaches achieved a sufficient standard both in TRI instruction and coaching methodology, they were certified as TRI coaches and started working with teachers in the study. Coaches received ongoing training and mentoring from the intervention director throughout the study to help them meet teacher’s needs.

Trustworthiness

Specific protocols were intentionally followed throughout the study to ensure trustworthiness of data collection and analysis. The research team included member checking, peer debriefing source triangulation (interviews, observations, and TRI newsletters), and sensitive and fair representation of participants within the study design to aid in the development of credibility, confirmability, dependability and transferability (Lincoln and Guba, 1985; Brantlinger et al., 2005). Participant protection measures including informed consent, and equitable selection of participants, as well as participant prioritization measures such as, inviting participants to confirm transcriptions and conclusions during member checking, provide respect for participant voice and acknowledgment of their experience. Participant demographics and thick descriptions of participant experiences are provided to facilitate naturalistic generalizability. Transparency in participant characteristics invites the reader to consider how the findings might be different had the participant characteristics differed.

Data analysis

Data was collected and analyzed over a period of 2 years. The dataset consists of ten audio or video recorded participant interviews and 24 video recorded coaching sessions. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, saved as word documents then imported into a qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti). All analysis, including initial coding, second-level hierarchical coding, analytic memoing, and generation of themes were completed within ATLAS.ti.

Following Miles et al. (2018) analytic guidelines, data were carefully reviewed. In cycle one coding, a priori codes derived from a pilot study (Cutrer and Ricks, 2013) were applied to the data. Next ATLAS.ti editing options were used to create second-level hierarchical codes (Saldaña, 2021). Finally, the second-level hierarchical codes were consolidated elaborate codes. When subthemes emerged, a matrix linking codes to emerging themes was created. Quotations corresponding to each emerging theme were partially annotated to provide a textural view of subthemes and were then consolidated into overarching themes (Miles et al., 2018).

Intercoder reliability

Two researchers (primary researcher and a secondary coder) were responsible for the coding of the data. To minimize bias the secondary coder analyzed 20% of the collected data (Bloomberg and Volpe, 2012). After initial coding, the two coders discussed and clarified codes. The primary researcher revised codes and the reliability processes were repeated. Intercoder reliability was at or above 0.90 after two rounds of coding.

Theme organization

After ensuring coding reliability, an iterative process was used to organize subthemes into themes. A narrative report was created that incorporated evidence from observations, transcripts, and study communications (Cutrer-Párraga et al., 2021).

Findings and discussion

The findings indicated that as coaches actively participated in collaborative reflection during coaching cycles with their teachers, they came to view teachers as capable adult learners. Also, the initially resistant-low implementing teachers who engaged in collaborative reflection with their coaches, were more likely to share instructional needs with coaches, demonstrate higher confidence in implementing the literacy intervention, express less resistance to coaching, and more willingness to implement the intervention.

Coaches actively participated in collaborative reflection during coaching cycles

In a typical coaching rotation, coaches are expected to engage teachers in cycles of demonstration, observation, and feedback with reflection (Mraz et al., 2016). In the second year of this study, collaborative reflection with coaches and teachers took place after the coaches observed teachers’ literacy lessons and after coach feedback. Collaborative reflection seemed to be a coaching component that allowed teachers to think deeply about and consider frustrating or undesirable components of coaching in alternate ways. The following scenarios describe how both teachers began to question their initial negative reactions and view coaching in a more favorable light after they engaged in collaborative reflection. In the first scenario, low-implementing/initially resistant teacher Ms. Frank shared how she learned through reflection to notice positive qualities about her coach. This reflection helped Ms. Frank to acknowledge the efforts of her coach:

My coach was very young, and that was hard for me. Sometimes it just burned me up. One day after a session, I was very frustrated because I had tried to connect with my coach, and it took almost 30 mins of class time to finally connect. I mean I was literally running up and down the hallway, you know? My coach apologized all over herself, but I was still frustrated. After my coach observed me and gave me feedback, we started talking about my daughter and she [the literacy coach] helped me with some questions I had about college. But I got off from the session still frustrated. I mean I was really put out, you know, wasting all that time. After I got off, I started reflecting on what happened. I started realizing how helpful the coach was in answering my questions about my daughter. When I calmed down, I realized that although it took 30 mins to connect, my coach was trying in every way possible to connect with me. I mean, seriously—bless her heart—the poor girl tried everything. She tried Skype, Facetime, and Google Chat. She even offered to audio-record me. When I reflected about it, though I was still annoyed about the time it took, no teacher has THAT much time, but it made me appreciate my coach more. Even though she was still very young, I could see how hard my coach was trying with me (Ms. Frank).

Ultimately, by reflecting on the experience Ms. Frank was able to let go of her annoyance and redefine her response to an event with an inexperienced coach resulting in her taking up a more productive attitude. Researchers suggest an overarching goal for collaborative reflection between coaches and teachers is to deepen understanding of individual students’ instructional needs for increased learning outcomes (Peterson et al., 2009). As initially resistant, low-implementing teacher, Ms. Docila engaged in reflection with her second year coach after literacy lessons, her understanding of her student’s instructional needs and progress deepened.

So after every session, my coach would say something like “Did you notice how he is doing such and such, so he might be ready to go to this level, so what do you think?” She never told me what to do. It was, she always just gave great insights and helped me understand why what I was doing was helping (the student). She would also offer suggestions if I asked. Then we would try it out together, and if it didn’t work we would come back and discuss why it worked or why it did not and what to do next (Ms. Docila).

Collaborative reflection, as a component of the coaching cycle, provided space where coaches and teachers could attend to student learning.

Coaches came to view teachers as capable adult learners

Teachers are first and foremost adult educators (L’Allier et al., 2010). Understanding adult learning and its salience for coaching teachers is imperative (Gallucci et al., 2010; Walpole and McKenna, 2013). Adult learning theory may lend insight into why the low-implementing teachers seemed to need a coaching approach pathway that included opportunities for collaborative reflection. The following key adult learning features help to demonstrate how collaborative reflection seemed to be effective with the low-implementing teachers: (a) adults need to know why they should learn something before commencing their learning; (b) adults have accumulated experiences that can be a rich resource for learning; and (c) adults have a psychological need to be treated by others as capable of self-direction.

Adults need to know why they should learn something before commencing their learning

Knowles (1989) explained that adults need to know why they should learn something before commencing their learning. This adult learning feature may help answer why collaborative reflection seemed to be successful in supporting the teacher participants. The use of video recordings is an essential tool in collaborative reflection with teachers (Stover et al., 2011). In the next scenario, Ms. Nance shared how the reflection process helped her to accept the reason for being videotaped, which was an undesirable component for her:

I can’t lie to you. I hated, I mean hated [teacher draws this word out slowly and loudly] being videoed. First of all, it made me want to run for the hills and second of all—well tell me—do you really know anyone who actually likes being videoed? And to tell you the truth I had never done it before. I was insecure not only about how I looked but just really how to do it, like the technology piece. Anyway, my coach asked me to really contemplate and reflect on how it could help me as a teacher like really think about it. And you know what? I realized it was making me better. I mean we teachers are used to doing hard things, right? So in my reflecting I realized I can do this hard thing and be an example to my team [teachers on the same grade level] and to myself. I can do hard things. And most of the time, hard things are good for us, aren’t they? Then I embraced it—the videoing—and now I am really good at it! Ha! I even do it with my kids who think I’m UH-mazing, and I’ve taught my other family how to do it. Have mercy—even my mama videos me now!

Ms. Nance’s experiences were typical of the other participants in the study who initially resisted the videotaping component of the intervention. Through reflection with her coach, Ms. Nance came to understand the reason for videotaping, and turned an initially negative experience into productive learning for her teaching and her life.

Adults have accumulated experiences that can be a rich resource for learning

Knowles (1989) argues that adults have accumulated experiences that can be a rich resource for learning. This may help to explain why coaches who used collaborative reflection to understand what teachers already knew then built upon that knowledge during coaching, seemed to help reluctant, low-implementing teachers move toward higher implementation. Low-implementing teacher, Ms. Harley referred to her process the first year as “trial and error” and “getting the kinks out.” She explained how implementing the TRI was different for her the second year as a result of collaborative reflection with her coach,

Well I guess in my first year, doing like a trial and error, uh huh, you have to do trial and error and you have to get the kinks out, like anything [else] I’ve done. And I felt more comfortable like how to do the reading and the writing. I was just a whole lot more valiant in the second go round, in the second year than in the first year. After reflecting with my coach, I realized I could do and was doing it a whole lot better than I did the first year. Like I said, that first year I was scared; I didn’t know what to do. When you don’t know what to do, you know, it just makes you nervous, and if you don’t have a full understanding of what you are doing and then you feel like, well how can I do my best if I don’t have an idea of what I am doing. But the second year was different. My coach helped me realize I knew a lot. I felt like I did know what I was doing and so I put my heart into it (Ms. Harvey).

As a result of collaborative reflection with her coach in the second year, Ms. Harvey realized she had accumulated experiences “my coach helped me realize I knew a lot” that became a resource for implementing the intervention with her students, “so I put my heart into it.”

Adults have a psychological need to be treated by others as capable of self-direction

Another key adult learning feature that may help to explain findings in this study is that adults have a psychological need to be treated by others as capable of self-direction (Knowles, 1989). In other words, adults prefer to plan and direct their own learning. This adult learning feature may help answer why low-implementing teachers reacted with initial resistance when they discovered that the TRI would be a mandatory requirement for them. Knowing that the TRI would be mandatory for teachers could be seen as nullifying teachers’ ability to be viewed as capable of self-direction. This concept is supported by Dozier (2014).

Mandated [coaching] bring(s) another layer of complexity to professional development initiatives. Some teachers resist leaving their classrooms, and others do not participate willingly. Yet in order for systemic change initiatives to take hold, some professional development will necessarily be mandatory to bring together all teachers to engage in the construction of a school- or district-wide vision of literacy and literacy teaching. Rethinking practices takes a willingness to engage in uncertainty and a willingness to move beyond resistance (p. 235).

Skinner et al. (2014) analyzed teachers’ enacted identities relative to being coached to implement new literacies strategies in their classrooms across two case studies; one of mandated participation and the other of voluntary participation. At Westview Middle School, where the teachers were mandated to attend coaching sessions, the teachers initially resisted and held tightly to their previous literacy practices. In comparison, the teachers at Laura Bailey Middle School, who were invited to participate in the coaching voluntarily, willingly explored and engaged with new literacies texts and tools, and discussed new literacies strategies.

Similar to the Skinner et al. (2014) study of coaching, all of the low-implementing teacher participants in this study spoke poignantly about how perceived lack of choices related to elements of the TRI created initial resistance to TRI implementation. Literacy coach Drew explained how collaborative reflection prompted the providing of more choice to the teacher, “After reflecting with her [the teacher] and realizing I needed to help her feel comfortable, I decided it didn’t matter to me when or where we coached. If I could get her to agree to do it, I would do it anyplace or at any time—” In a similar way, literacy coach Sam described how he offered choice to his low-implementing/initially resistant teacher Ms. Chin after engaging in reflection.

If Ms. Chin missed three or four sessions and I hadn’t heard from her, I would say, “Okay I am coming to visit now. I would talk with her. I would hear her concerns then I began to offer more of what she needed. I would say – I will model whatever you want.” And I would say, “We are going to make this happen. I’m here to support you so I would be happy to model a lesson. We are missing all these sessions so we have to sit and do a lesson. But after reflection, I offered more of what she wanted and I would add “if you want me to do it, I will do it. You just sit and watch.” And so that is what we started doing and it helped (Sam).

Drew and Sam clearly indicated that as coaches they came to understand the value of collaborative reflection both for their relationships with the teachers and in order to have increased engagement through providing choice with the teachers.

Teachers came to share instructional needs with coaches

When coaches incorporated reflection with their teachers, the coaches learned to listen better to teacher needs. Teachers then began sharing individual needs with coaches as evidenced by coach Elise. The teachers needed to reflect with Elise about their negative past experiences with coaching before being willing to implement. As Elise gave them this opportunity to reflect, the teachers felt heard and were able to move forward:

They [initially resistant/low-implementing teachers] wanted to be able to be validated on their past negative experiences. It was awkward for me because I did not want to get into specific conversations about the previous coach, so I tried to keep it in a professional way. But some of them just needed the chance to reflect and say “I didn’t like that coach. I didn’t like what she said to me, when she did this to me.” When I slowed down enough to engage in reflection and then just say, “I’m sorry that happened to you,” they moved on (Elise).

Note that Elise listened to the needs of the teachers which allowed space for teachers to report and articulate their negative experiences.

Teachers began recognizing growth and demonstrating higher confidence in implementing the literacy intervention

Collaborative reflection between coaches and teachers encourages teachers to recognize their own growth (Korthagen and Vasalos, 2005). This was true for the low implementing teachers in this study. For instance, Ms. Docila commented; “I really think I have grown in reflecting on myself with my coach.” Collaborative reflection also fosters higher confidence in teachers (Keay et al., 2019; Sprott, 2019). Below is an analytic memo written to describe the step-by-step changes in live coaching sessions between TRI literacy coach Sam and Ms. Chin:

Video of coaching session one (October)

Coaching session opens with Ms. Chin’s back turned, facing the camera so that she cannot see or hear coach Sam. Sam’s view of Ms. Chin is only of her back. Sam is taking notes. When Sam attempts to give Ms. Chin feedback, she frowns at Sam and then completely ignores him and continues with the student. The awkwardness in the coaching session seems palpable. I feel uncomfortable watching the session because of the tension in the air. The TRI lesson is completely incorrect. At the end of the session, Sam thanks Ms. Chin. Sam asks Ms. Chin to work on one thing: asking the child to say the sound instead of the letter name. Ms. Chin quickly ends video. Teacher does not attempt full lesson.

Video of coaching session two (November)

Video opens with Ms. Chin’s back facing the camera again, but this time at more of an angle where the side of Ms. Chin’s face is noticeable. TRI lesson still incorrect. However, Ms. Chin is directing student to say letter sound instead of letter name each time. When Sam gives instruction, Ms. Chin does not respond; however, she does listen and nod her head as opposed to completely ignoring Sam as in previous coaching session. Teacher does not attempt full lesson.

Video, final coaching session (May)

Coaching session opens with Ms. Chin smiling into camera. Ms. Chin thanks Sam for sending some sort of card to her—sounded like a get-well card. Still inaccuracies of implementing TRI (confusion between segmenting words, change one sound, and read write and say); however, teacher attempting full lesson. Sam corrects Ms. Chin and refers to an earlier reflection session with goals Ms. Chin made. Ms. Chin smiles and accepts feedback. Can’t help noticing the change in Ms. Chin’s demeanor. Even though there are mistakes in implementation, Ms. Chin seems calm and confident. Yes, she seems much more confident (Analytic Memo 6015).

Going back to the interview transcripts with Ms. Chin, Ms. Chin did not seem to notice the small changes that took place over a period of time. Nor did Ms. Chin notice any differences in the way she was coached. Instead, she seemed to notice her own progress and growth in confidence.

Well, I didn’t see any differences with Sam [the coach]. I think that a lot of the difference was the fact that I probably had more of a positive attitude because I felt more confident after my coach and I reflected on my teaching together. And if I feel like I’m really good at something, then I feel like I am going to try it (Ms. Chin).

Reflection with evidence enabled the teachers recognize progress and increase in confidence.

Teachers began expressing less resistance to coaching

All study participants (high-implementing teachers, low-implementing/initially resistant teachers, and coaches) cited examples of how reflection helped support teachers in implementing increased sessions of the reading intervention in the second year. Literacy coach Elise explained in detail how she learned to engage teachers in collaborative reflection to lessen resistance. Elise said,

Something I learned that I always try to keep in mind: If people resist you, many times our first inclination is to then change your message so they won’t resist. “Oh you don’t want to do TRI? Okay I won’t ask you to do TRI.” I mean that is what I would want to say. I mean I don’t want teachers to resist me. But it’s not watering down your message, it’s more about my method of saying it. How can I get to the same result even if we have to take a different path? If the key principles are there, you have to be open in the processes. You have to ask them to think about what is happening. After they reflect, you have to reflect as a coach. You have to make allowances in the processes. For those teachers who were so resistant, after I reflected with them – I could understand better why they would resist. So I let them choose. I gave them parameters that we have to do and I said “Let’s all figure it out within that.” I think that the previous coach had tried to go at it like “Let’s have team meetings. They are a great thing. You guys will really want to do this,” and she really glossed over you don’t have a choice about it. And she never reflected on why teachers would or would not want to do that and why. She tried to make it seem like it was their choice, but then she was going to get you and report you when you don’t do it. After reflecting, that made me really, really clear with them: “We have to have team meetings, we have to have email correspondence, we have to have individual sessions about TRI. Now anything other than that I am really open to whatever makes it work with you guys.” (Elise)

Elise suggests that engaging teachers in collaborative reflection opens space for increased implementation within a hard coaching mode (Cutrer-Párraga et al., 2021).

Conclusion

This study described how coaches incorporated collaborative reflection with high implementing and initially resistant-low implementing teachers in four rural, low resourced school districts in the southeastern, United States. Overall, study findings indicate that both high implementing and low implementing initially resistant teachers responded well to collaborative reflection.

For low implementing initially resistant teachers specifically, collaborative reflection seemed to expand coach engagement, strengthen confidence in the intervention, and grow teacher willingness to implement the intervention. Moreover, active reflection with their coach seemed to provide a space where teachers’ voices and concerns mattered and provided time to connect and strengthen a relationship with their coach. Further, as coaches actively participated in collaborative reflection, they began to view teacher participants as adult learners. The time spent reflecting with their teachers allowed them to gain understanding of the teachers’ needs and the barriers hindering the teachers’ implementation of the TRI, as wells as to develop a framework to help teachers be willing to participate in the intervention.

Implications for practice, limitations, and suggestions for future research

The implications of this study are designed to enhance the understanding of ways collaborative reflection might be incorporated more effectively in active coaching with teachers. By soliciting both high implementing, initially resistant-low implementing teachers and their coaches to convey lived experiences with coaching during year one and year two of a literacy intervention study, the researchers gained insights about the benefit of collaborative reflection with initially resistant-low implementing teachers. More research is needed in this area, with particular emphasis on practical strategies and processes for coaches to implement collaborative reflection with teachers (Jiang and Zheng, 2021). Implications include that universities (Foong et al., 2018) and school districts need to increase opportunities for preservice and in-service teachers to develop and practice collaborative reflection (Glazer et al., 2004).

Collaborative reflection involves skill, finesse, and ingenuity – particularly when working with teachers who may feel initial resistance (Clarà et al., 2019). There is limited research on the teachers’ role in developing effective collaborative reflection frames. Teachers are too often absent in the development of collaborative reflection models and prescribed reflection processes may be too narrowly structured to inspire teachers to collaborate with an “other” openly (Çimer et al., 2013). Future research needs to explore teacher involvement in creating effective collaborative reflection models with coaches. This study examined the interactions between coaches and teachers as one piece of a larger study and did not attempt to quantify or qualify the fidelity of coaches’ use and implementation of collaborative reflection with fidelity data. Further research is necessary in this area.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

EC-P contributed to the research design, data collection, data analysis, and wrote and edited the manuscript. EM was a contributing author and helped write and edit the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Support for this research was provided by Grant R305A100654 from the Institute of Education Sciences, awarded to Lynne Vernon-Feagans.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

Al Otaiba, S., Hosp, J. L., Smartt, S., and Dole, J. A. (2008). The challenging role of a reading coach, a cautionary tale. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 18, 124–155. doi: 10.1080/10474410802022423

Ali, Z. B. M., Wahi, W., and Yamat, H. (2018). A review of teacher coaching and mentoring approach. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 8, 504–524. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i8/4609

Amendum, S. J., Bratsch-Hines, M., and Vernon-Feagans, L. (2018). Investigating the efficacy of a web-based early reading and professional development intervention for young English learners. Read. Res. Q. 53, 155–174. doi: 10.1002/rrq.188

Artman-Meeker, K., Hemmeter, M. L., and Snyder, P. (2014). Effects of distance coaching on teachers’ use of pyramid model practices: A pilot study. Infants Young Child. 27, 325–344. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0000000000000016

Attard, K. (2012). Public reflection within learning communities: An incessant type of professional development. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 199–211. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2011.643397

Biancarosa, G., Bryk, A. S., and Dexter, E. R. (2010). Assessing the value-added effects of literacy collaborative professional development on student learning. Elem. Sch. J. 111, 7–34. doi: 10.1086/653468

Bloomberg, L. D., and Volpe, M. (2012). Completing your qualitative dissertation: A roadmap from beginning to end. Thousand Oakes, CA: SAGE.

Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., and Richardson, V. (2005). Qualitative studies in special education. Except. Child. 71, 195–207. doi: 10.1177/001440290507100205

Carlisle, J. F., and Berebitsky, D. (2011). Literacy coaching as a component of professional development. Read. Writ. 24, 773–800. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3243-2

Çimer, A., Çimer, S. O., and Vekli, G. S. (2013). How does reflection help teachers to become effective teachers. Int. J. Educ. Res. 1, 133–149.

Clarà, M., Mauri, T., Colomina, R., and Onrubia, J. (2019). Supporting collaborative reflection in teacher education: A case study. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 175–191. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1576626

Collet, V. S. (2012). The gradual increase of responsibility model: Coaching for teacher change. Lit. Res. Instr. 51, 27–47. doi: 10.1080/19388071.2010.549548

Connor, C. M. (2017). Commentary on the special issue on instructional coaching models: Common elements of effective coaching models. Theory Into Pract. 56, 78–83. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1274575

Cutrer, E., and Ricks, D. (2013). Teacher perceptions of how to implement and sustain a tier two reading intervention via web-cam coaching [paper session]. Bronson, MO: 2013 NREA Annual Conference.

Cutrer-Párraga, E. A., Hall-Kenyon, K. M., Miller, E. E., Christensen, M., Collins, J., Reed, E., et al. (2022). Mentor teachers modeling: Affordance or constraint for special education pre-service teachers in the practicum setting? Teach. Dev. 26, 587–605. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2022.2105939

Cutrer-Párraga, E. A., Heath, M. A., and Caldarella, P. (2021). Navigating early childhood teachers initial resistance to literacy coaching in diverse rural schools. Early Child. Educ. J. 49, 37–47. doi: 10.1007/s10643-020-01037-5

Daniel, G. R., Auhl, G., and Hastings, W. (2013). Collaborative feedback and reflection for professional growth: Preparing first-year pre-service teachers for participation in the community of practice. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 41, 159–172. doi: 10.1080/1359866x.2013.777025

Desimone, L. M., and Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Pract. 56, 3–12. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1241947

Desimone, L. M., Stornaiuolo, A., Flores, N., Pak, K., Edgerton, A., Nichols, T. P., et al. (2019). Successes and challenges of the “new” college-and career-ready standards: Seven implementation trends. Educ. Res. 48, 167–178. doi: 10.3102/0013189X19837239

Domitrovich, C. E., Gest, S. D., Gill, S., Jones, D., and DeRousie, R. S. (2009). Individual factors associated with professional development training outcomes of the Head Start REDI program. Early Educ. Dev. 20, 402–430. doi: 10.1080/10409280802680854

Dozier, C. L. (2014). Literacy coaching for transformative pedagogies: Navigating intellectual unrest. Read. Writ. Q. 30, 233–236. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2014.908684

Elish-Piper, L., and L’Allier, S. K. (2010). Exploring the relationship between literacy coaching and student reading achievement in grades K–1. Lit. Res. Instr. 49, 162–174. doi: 10.1080/19388070902913289

Ennis, R. P., Royer, D. J., Lane, K. L., and Dunlap, K. D. (2020). The impact of coaching on teacher-delivered behavior-specific praise in Pre-K–12 settings: A systematic review. Behav. Disord. 45, 148–166. doi: 10.1177/0198742919839221

Fabiano, G. A., Reddy, L. A., and Dudek, C. M. (2018). Teacher coaching supported by formative assessment for improving classroom practices. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 293–304. doi: 10.1037/spq0000223

Fixsen, D., Blase, K., Metz, A., and Van Dyke, M. (2013). Statewide implementation of evidence- based programs. Except. Child. 79, 213–230. doi: 10.1177/001440291307900206

Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Naoom, S. F., and Wallace, F. (2009). Core implementation components. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 19, 531–540. doi: 10.1177/1049731509335549

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., Wallace, F., Burns, B., et al. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute.

Foong, L. Y. Y., Nor, M. B. M., and Nolan, A. (2018). The influence of practicum supervisors’ facilitation styles on student teachers’ reflective thinking during collective reflection. Reflect. Pract. 19, 225–242. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2018.1437406

Fox, L., Hemmeter, M. L., Snyder, P., Binder, D. P., and Clarke, S. (2011). Coaching early childhood special educators to implement a comprehensive model for promoting young children’s social competence. Topics Early Child. Spec. Educ. 31, 178–192. doi: 10.1177/0271121411404440

Gallucci, C., Van Lare, M. D., Yoon, I. H., and Boatright, B. (2010). Instructional coaching: Building theory about the role and organizational support for professional l earning. Am. Educ. Res. J. 47, 919–963.

Gelfuso, A., and Dennis, D. V. (2014). Getting reflection off the page: The challenges of developing support structures for pre-service teacher reflection. Teach. Teach. Educ. 38, 1–11.

Glazer, C., Abbott, L., and Harris, J. (2004). A teacher-developed process for collaborative professional reflection. Reflect. Pract. 5, 33–46. doi: 10.1080/1462394032000169947

Hathaway, J. I., Martin, C. S., and Mraz, M. (2016). Revisiting the roles of literacy coaches: Does reality match research? Read. Psychol. 37, 230–256. doi: 10.1080/02702711.2015.1025165

Ippolito, J., and Lieberman, J. (2020). “Literacy coaches as literacy leaders,” in Best practices of literacy leaders: Keys to school improvement, 2nd Edn, eds R. M. Bean and A. S. Dagen (New York, NY: Guilford Press), 69–88.

Jacobs, J., Boardman, A., Potvin, A., and Wang, C. (2018). Understanding teacher resistance to instructional coaching. Prof. Dev. Educ. 44, 690–703. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2017.1388270

Jiang, Y., and Zheng, C. (2021). New methods to support effective collaborative reflection among kindergarten teachers: An action research approach. Early Child. Educ. J. 49, 247–258. doi: 10.1007/s10643-020-01064-2

Katz, S., and Earl, L. (2010). Learning about networked learning communities. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 21, 27–51. doi: 10.1080/09243450903569718

Keay, J. K., Carse, N., and Jess, M. (2019). Understanding teachers as complex professional learners. Prof. Dev. Educ. 45, 125–137. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2018.1449004

Kindred, J. B. (1999). “8/18/97 Bite me”: Resistance in learning and work. Mind Cult. Act. 6, 196–221.

Knight, J. (2009). What can we do about teacher resistance? Phi Delta Kappan 90, 508–513. doi: 10.1177/003172170909000711

Knight, J. (2019). Instructional coaching for implementing visible learning: A model for translating research into practice. Educ. Sci. 9:101. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020101

Korthagen, F., and Vasalos, A. (2005). Levels in reflection: Core reflection as a means to enhance professional growth. Teach. Teach. 11, 47–71. doi: 10.1080/135406000420003370093

Kraft, M. A., and Blazar, D. (2018). Taking teacher coaching to scale: Can personalized training become standard practice? Educ. Next 18, 68–75.

Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., and Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 88, 547–588. doi: 10.3102/0034654318759268

Kretlow, A. G., and Bartholomew, C. C. (2010). Using coaching to improve the fidelity of evidence-based practices: A review of studies. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 33, 279–299. doi: 10.1177/0888406410371643

L’Allier, S., Elish-Piper, L., and Bean, R. M. (2010). What matters for elementary literacy coaching? Guiding principles for instructional improvement and student achievement. Read. Teach. 63, 544–554.

Lambert, M. D., Sorensen, T. J., and Elliott, K. M. (2014). A comparison and analysis of preservice teachers’ oral and written reflections. J. Agric. Educ. 55, 85–99. doi: 10.5032/jae.2014.04085

Lemons, C. J., Otaiba, S. A., Conway, S. J., and Mellado De La Cruz, V. (2016). Improving professional development to enhance reading outcomes for students in special education. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2016, 87–104. doi: 10.1002/cad.20177

López-de-Arana Prado, E., Martínez Gorrotxategi, A., Agirre García, N., and Bilbatua Pérez, M. (2019). More about strategies to improve the quality of joint reflection based on the theory-practice relationship during practicum seminars. Reflect. Pract. 20, 790–807. doi: 10.1080/14623943.2019.1690982

Matsumura, L. C., Garnier, H. E., and Resnick, L. B. (2010). Implementing literacy coaching: The role of school social resources. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 32, 249–272. doi: 10.3102/0162373710363743

McKenna, M. C., and Walpole, S. (2013). The literacy coaching challenge: Models and methods for grades K-8. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldaña, J. (2018). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Moore-Russo, D. A., and Wilsey, J. N. (2014). Delving into the meaning of productive reflection: A study of future teachers’ reflections on representations of teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 37, 76–90.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. J. Couns. Psychol. 52, 250–260. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

Mraz, M., Salas, S., Mercado, L., and Dikotla, M. (2016). Teaching better, together: Literacy coaching as collaborative professional development. English Teach. Forum 54, 24–31.

Musanti, S. I., and Pence, L. (2010). Collaboration and teacher development: Unpacking resistance, constructing knowledge, and navigating identities. Teach. Educ. Q. 37, 73–89.

National Implementation Research Network [NIRN] (2022). Active implementation hub. Available online at: https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/module-2/coaching (accessed September 3, 2022).

Neuman, S. B., and Cunningham, L. (2009). The impact of professional development and coaching on early language and literacy instructional practices. Am. Educ. Res. J. 46, 532–566. doi: 10.3102/0002831208328088

Neumerski, C. M. (2012). Leading the improvement of instruction: Instructional leadership in high-poverty, urban schools. Doctoral dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Olson, M. R., and Craig, C. J. (2005). Undercovering cover stories: Tensions and entailments in the development of teacher knowledge. Curric. Inq. 35, 161–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-873X.2005.00323.x

Orlando, J. (2014). Veteran teachers and technology: Change fatigue and knowledge insecurity influence practice. Teach. Teach. 20, 427–439. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.881644

Peterson, D. S., Taylor, B. M., Burnham, B., and Schock, R. (2009). Reflective coaching conversations: A missing piece. Read. Teach. 62, 500–509.

Pianta, R. C., Lipscomb, D., and Ruzek, E. (2021). Coaching teachers to improve students’ school readiness skills: Indirect effects of teacher–student interaction. Child Dev. 92, 2509–2528. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13600

Prilla, M., and Renner, B. (2014). “Supporting collaborative reflection at work: A comparative case analysis,” in Proceedings of the 18th international conference on supporting group work, (New York, NY: ACM), 182–193.

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 1–440.

Sannino, A. (2010). Teachers’ talk of experiencing: Conflict, resistance and agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.021

Shidler, L. (2009). The impact of time spent coaching for teacher efficacy on student achievement. Early Child. Educ. J. 36, 453–460. doi: 10.1007/s10643-008-0298-4

Skinner, E. N., Hagood, M. C., and Provost, M. C. (2014). Creating a new literacies coaching ethos. Read. Writ. Q. 30, 215–232. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2014.907719

Sprott, R. A. (2019). Factors that foster and deter advanced teachers’ professional development. Teach. Teach. Educ. 77, 321–331.

Steckel, B. (2009). Fulfilling the promise of literacy coaches in urban schools: What does it take to make an impact? Read. Teach. 63, 14–23. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.1.2

Stover, K., Kissel, B., Haag, K., and Shoniker, R. (2011). Differentiated coaching: Fostering reflection with teachers. Read. Teach. 64, 498–509. doi: 10.1598/RT.64.7.3

Trivette, C. M., Dunst, C. J., Hamby, D. W., and O’herin, C. E. (2009). Characteristics and consequences of adult learning methods and strategies. Res. Brief 3, 1–33.

Tye, K. A., and Tye, B. B. (1993). The realities of schooling: Overcoming teacher resistance to global education. Theory Into Pract. 32, 58–63. doi: 10.1080/00405849309543574

Valoyes-Chávez, L. (2019). On the making of a new mathematics teacher: Professional development, subjectivation, and resistance to change. Educ. Stud. Math. 100, 177–191. doi: 10.1007/s10649-018-9869-5

Vernon-Feagans, L., Bratsch-Hines, M. E., Varghese, C., Cutrer, E. A., and Garwood, J. (2018). Improving struggling readers’ early literacy skills through a tier 2 professional development program for rural classroom teachers: The Targeted Reading Intervention (TRI). Elem. Sch. J. 118, 525–548. doi: 10.1086/697491

Walpole, S., and McKenna, M. C. (2013). The literacy coach’s handbook: A guide to research- based practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Keywords: teacher education, reflection, preservice < teacher education, coaching, literacy

Citation: Cutrer-Parraga EA and Miller EE (2022) The role of reflection in supporting initially resistant teachers’ implementation of targeted reading instruction. Front. Educ. 7:1048716. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1048716

Received: 19 September 2022; Accepted: 24 October 2022;

Published: 08 December 2022.

Edited by:

Shaun Murphy, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaReviewed by:

Eliza Pinnegar, Independent researcher, Orem, United StatesMary Frances Rice, University of New Mexico, United States

Mary Frances Hill, The University of Auckland, New Zealand

Copyright © 2022 Cutrer-Parraga and Miller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth A. Cutrer-Parraga, ZWxpemFiZXRoY3V0cmVyQGJ5dS5lZHU=

Elizabeth A. Cutrer-Parraga

Elizabeth A. Cutrer-Parraga Erica Ellsworth Miller2

Erica Ellsworth Miller2