- 1Department of Teacher Education, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT, United States

- 2Utah State Board of Education, Salt Lake City, UT, United States

- 3Jordan School District, South Jordan, UT, United States

- 4Alpine School District, American Fork, UT, United States

- 5Nebo School District, Spanish Fork, UT, United States

Background: University supervisors in teacher education assume a complex and demanding role, which is essential to the development of prospective teachers, but is often underappreciated or ignored.

Aim: This descriptive study was designed to explore former clinical faculty associates’ (CFAs’) perceptions of the challenges and opportunities inherent in their work as CFAs, and the influence of this experience on their future professional work.

Materials and methods: Using survey research methodology, followed by selected individual interviews, this paper focuses on the experiences of CFAs, highly respected PK-6 teachers employed by the university for 2–3 years to serve as university supervisors.

Results and conclusion: Although participants reported facing several professional and personal challenges as CFAs, they also described opportunities to participate in a wide variety of professional experiences that positively impacted their future work. Furthermore, most reported feeling the CFA experience was professionally renewing and brought opportunities to build strong personal and professional relationships that cross institutional boundaries.

Introduction

Mentoring prospective and beginning teachers has long been considered a critical component of teacher education (Hagger et al., 1994; Darling-Hammond et al., 2005; Marable and Raimondi, 2007), induction [Martin et al., 2016; see also Stephensen and Bartlett (2009)], and retention efforts and programs (Odell and Ferraro, 1992; Smith and Ingersoll, 2004; Whalen et al., 2019). This is particularly true in the context of school-university partnerships, where teacher candidates are guided and supported by experienced classroom teachers and by university supervisors/clinical faculty, sometimes referred to as hybrid teacher educators (Zeichner, 2010). Interestingly, much of the existing literature devoted to mentors and mentoring in teacher preparation has focused on preservice teachers and cooperating teachers (e.g., mentor teachers), with far less attention given to those who serve as university supervisors.

In 2004, Bullough and colleagues explored the role of clinical faculty/university supervisors in the context of building and sustaining university-school partnerships, concluding that “identity formation and relationship building” are at the heart of this collaborative work (p. 505). With this in mind, we began to wonder how university supervisors are faring as they engage in their work as hybrid teacher educators within university partnerships. More specifically, we sought to better understand how the work of university supervisors/clinical faculty impacts them personally and professionally.

The role of university supervisors

University supervisors fulfill a complex and demanding role see Burns et al. (2016), Jacobs et al. (2017). However, research suggests that the work of these individuals is often underappreciated and even ignored (McCormack et al., 2019). Still, teacher preparation programs rely heavily on the work of these faculty members who are responsible for fostering relationships within the university and public schools, supporting preservice teachers both personally and professionally, and developing program coherence (e.g., connecting university coursework with field-based experiences). Fulfilling these expectations requires relationship building and communication skills (Gimbert and Nolan, 2003; Nguyen, 2009; Johnson and Napper-Owen, 2011), as well as a strong K-12 teaching background (Hertzog and O’Rode, 2011) and a working knowledge of teacher preparation within the university (Valencia et al., 2009).

Scholars have raised questions about the role of supervision in teacher preparation (Glanz, 1996; Byrd and Fogleman, 2012) including who should perform the work (Richardson-Koehler, 1988; Burns et al., 2016). Some programs hire adjunct faculty; others rely on program faculty or hire full-time clinical faculty. Regardless of their position, university supervisors often “suffer overwhelming workloads, feel marginalized…, lack ongoing training and are often unclear as to what their role is” (McCormack et al., 2019, p. 22).

Given these challenges, Burns et al. (2016) have suggested rethinking university supervision for preservice teachers, recommending that the role and title be shared between the public schools and the university (e.g., “preservice teacher supervisor” for both classroom and university mentors, p. 422). This recommendation alone will likely not result in substantial change; however, as Burns et al. have also suggested, creating a role that “is more inclusive of a variety of terms of contextually-specific boundary-spanning roles in an era of increased school-university collaboration” (p. 422) may result in more meaningful changes.

In the context of a long-standing public school partnership between our institution and local school districts, efforts have been made to create boundary-spanning roles, which are mutually reinforcing to both the public schools and the university. As a result, we are well-situated to further explore the role of university supervisors, including some of the challenges and opportunities inherent in their work. In these efforts we have sought to investigate teaching and mentoring experiences, as well as other relationships and knowledge university supervisors have developed through interaction with university programs and faculty, which have led to personal learning, professional development, and shifts in thinking and practice.

University-public school partnership

In 1984, the College of Education entered into a formal partnership with five surrounding school districts and the university colleges of arts and sciences. The Partnership was originally based on the work of John Goodlad (1984), who emphasized the symbiotic relationship between universities and public schools as essential to improving both the preparation of teachers and the schooling of children and youth. Collaboration within the Partnership requires the mutual understanding that comes from opportunities to learn together and, in the process, to learn from each other. An example of the resulting simultaneous renewal see Goodlad (1994) can be seen in the work of clinical faculty associates (CFAs), who serve as the university supervisors for our teacher preparation programs.

Clinical faculty associates

In 1996, the Partnership implemented an experimental program to increase simultaneous renewal by working to elevate the quality of teacher preparation. Six open FTEs in the department were dedicated to 12 elementary-grade master teachers from the partnership districts. These teachers would be appointed as clinical faculty associates (CFAs) to work in the program as university supervisors. It was determined that applications for these positions would be limited to teachers from within the five partnership districts and decisions about CFA appointments (2–3 years) would be made jointly with the university and school districts. Although roles have changed slightly over time, the selection and hiring process has remained the same.

Role of clinical faculty associates

The CFA role is complicated. These individuals serve as hybrid teacher educators, who are crucial to the quality and success of the teacher education program and the Partnership, narrowing the gap between the institutions. Their primary responsibilities are to teach, mentor, and supervise preservice teachers, while also helping to form, maintain, and extend strong relationships between the public schools and the university. At the end of their appointment, these individuals typically return to various positions at the school and district level with a desire to stay connected to the university and participate in teacher preparation. Although only one possible model for employing university supervisors, the CFA model is also intended to help to provide opportunities for personal and professional growth for the person working in this capacity, as well as simultaneous renewal across the partnership.

Simultaneous renewal

As noted above, our partnership has been growing and evolving for 30+ years. Its strength is found in the purposeful investment in people/relationships and a shared commitment to the well-being of K-12 students and their teachers. One of four main tenets of our partnership vision statement is simultaneous renewal: “…the Partnership fosters in educators a commitment to renewal through consistent inquiry, reflection, and action within their professional practice, resulting in continuous improvement” (see partnership website). Creating a culture of collaboration, growth and improvement takes time, but it also results in more significant, longer-term change (Shroyer et al., 2007). Ultimately, renewal efforts are most successful when they build capacity from within. As Goodlad (1999) argued, “any change that depends on just a few…designated leaders is hazardous. The message: Leadership must be widely shared, which in turn means that preparation for leadership must be a built-in, continuing activity” (p. 13). Although our CFA program is not a leadership preparation program, many of the CFAs return to the schools to provide leadership within their sphere of influence. Building capacity for future leadership, creating advocates for teacher preparation, supporting strong teacher mentors, and ultimately improving education and schooling for Prek-12 students are all critical components of simultaneous renewal and necessary for any thriving, growing university public-school partnership see Bier et al. (2012).

Our clinical faculty associates (university supervisors) have long played a critical role in university-public school partnerships and the work of teacher preparation, yet little is known about how they believe they are faring. The purpose of this study is to examine how former CFAs view their experience and how those experiences have impacted and are continuing to impact their subsequent work as educators. In essence, is, or was, the CFA experience personally renewing?

Materials and methods

Study purpose and design

Using survey research methodology followed by selected individual interviews, this descriptive study (see Gall et al., 2003) was designed to explore clinical faculty associates’ (CFAs) perceptions of (a) the challenges and opportunities inherent in their work as university supervisors, and (b) the influence of this experience on their professional work in education. Data collection occurred in two phases. First, all individuals who had worked as a CFA from 2000 to 2017 (n = 44) were asked to respond to an online questionnaire designed to gain an understanding of their experiences as CFAs and their professional work in education that followed. After preliminary analysis of participants’ responses, four respondents were purposefully selected as representative cases of the career pathways chosen by individuals following their CFA experience. They were then asked to respond to a series of questions in order to dealve more deeply into the details of the survey responses, including (a) pathways to becoming a CFA, (b) experiences while working in this capacity, and (c) perceptions of the impact of these experiences on their professional work.

Participants

Participants included experienced elementary classroom teachers who had worked as Cinical Faculty Associates (CFAs) for 2 or 3 years in either the Early Childhood Education (ECE) or Elementary Education (ELED) program from 2005 to 2017. Years of teaching experience at the time of the study ranged from 6 to 31+ years, with 54% of participants having taught for 25+ years. The highest level of formal education at the time of the study across participants was BA/BS 18%, MA/MS 77%, and PhD/EdD 5%. Of the 44 individuals contacted, three requests were returned as “undeliverable”; 38 individuals (93%) responded to the invitation to participate in the study.

Data source

An invitation to participate in the study with a survey link was distributed via email. The questionnaire consisted of both open- and closed-ended questions (Cohen et al., 2018). Participants were asked to respond to forced-choice multiple-choice questions (e.g., What is your highest level of education?) and to free choice multiple-choice items (e.g., What positions have you held in the district since your time as a CFA? Select all that apply.). They were also prompted to respond to a series of open response questions asking them to describe their work as a CFA and to explain their perception of its influence on their thinking and/or practice. Two follow-up email requests for participation were sent to non-respondents at 1-week intervals.

Recognizing that Internet questionnaires are “an impersonal medium, with no opportunities for in-depth probes” (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 363) and may be fraught with misleading information because participants lack the ability to request explanations or to develop the trust that can exist during face-to-face interviews (Kilinç and Fırat, 2017), we conducted follow-up interviews with four participants purposefully selected as representative cases of different career pathways most often chosen by CFAs or assigned to them following their work at the university (see Miles and Huberman, 1994). These individuals represent (a) a classroom teacher, (b) a school leader/administrator, (c) a district leader (i.e., director, specialist, coach), and (d) a classroom teacher who had again returned to the university in some capacity. These individual interviews, which included both written prompts and face-to-face questions and follow-up clarifying questions, as appropriate, prompted participants to more fully describe (a) their pathway to becoming a CFA, (b) challenges associated with being a CFA, (c) opportunities they experienced as a CFA, and (d) impacts of this experience on their current professional work and career pathways.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed in three phases. First, to better understand the overall population of former CFAs who responded to the survey, we used both quantitative and qualitative methods to analyze responses to the online questionnaire. Considering these results, we then selected four respondents as representative of different, but most common, career pathways chosen by or assigned to CFAs following their work at the university. Finally, using the responses provided by these four individuals, we conducted a cross-case analysis. Each of these phases is detailed in the following subsections.

Questionnaire

All single answer/forced-choice and free choice multiple-choice questions were analyzed to yield frequencies and percentages of respondents. As appropriate, additional categories were added based on participant responses to the option “Other.”

Open-ended questions were analyzed through an inductive process. First, two members of the research team (university-based teacher educators) independently reviewed transcripts of participant responses line by line, assigning codes to phrases or text segments, focusing on semantic relationships while interpreting meaning. Thus, a label was assigned to each phrase or word unit, then grouped into categories (Creswell and Clark, 2011). Together, the researchers then compared, clarified, and revised the coding categories, reaching consensus as they formulated a list of emergent themes for each question. Throughout this process, in order to ensure the rigor and validity of the analysis, a search was made for both confirming and disconfirming evidence (Duran et al., 2006).

Case studies

Analysis of the initial survey data suggested four overarching and representative career trajectories: (a) a return to the classroom, (b) an assignment to a leadership position in a public school, (c) an assignment to a leadership position in a school district, and (d) a return to the classroom followed by a decision to return to the university (i.e., second CFA term). Representative individuals from these career pathways were asked to respond in writing to four open-ended questions to more fully illuminate the results of the survey and thus enable researchers to “gather descriptive data in the subjects’ own words” (Bogdan and Biklen, 1998, p. 93). This was followed by a face-to-face group interview/conversation with all four participants and members of the research team, which was recorded using field notes.

Responses to the additional questions enabled the researchers to hear individual’s personal stories in detail; the group interview then led to a more nuanced description of the CFA experience, allowing participants to “support, influence, complement, agree and disagree (and sometimes commiserate) with each other” (Cohen et al., 2018). As noted previously, both written response and group interview questions prompted participants to describe (a) their pathway to becoming a CFA, (b) the challenges faced as a CFA, (c) the opportunities introduced while working as a CFA, and (d) the impact or influence of this experience on their professional work. Both individual and group responses were then examined and coded for emergent themes, as described previously.

Cross-case analysis

Finally, in order to “deepen our understanding” of the CFA experience and “to enhance generalizability” (Miles and Huberman, 1994, p. 173) of the study, a cross-case or multiple-case analysis was conducted. Based on emergent patterns in the cases, relational and causal factors were detected (Gall et al., 2003)—challenges, opportunities, and impact/influence on subsequent professional work.

Results

With the overall purpose of understanding CFAs’ perceptions of (a) the challenges and opportunities inherent in their work as CFAs, and (b) the influence of this experience on their professional work in education, this section is divided into two subsections. First, we report all participants’ (n = 38) responses to the survey followed by a description of four representative cases and a cross-case analysis.

Survey results

The survey included questions designed to (a) characterize the group of participants, including current and interim professional positions, (b) describe the responsibilities of a CFA, (c) identify the opportunities, benefits, and challenges associated with this work, and (d) share how the experience influenced their thinking and practice as educators.

Current and interim positions

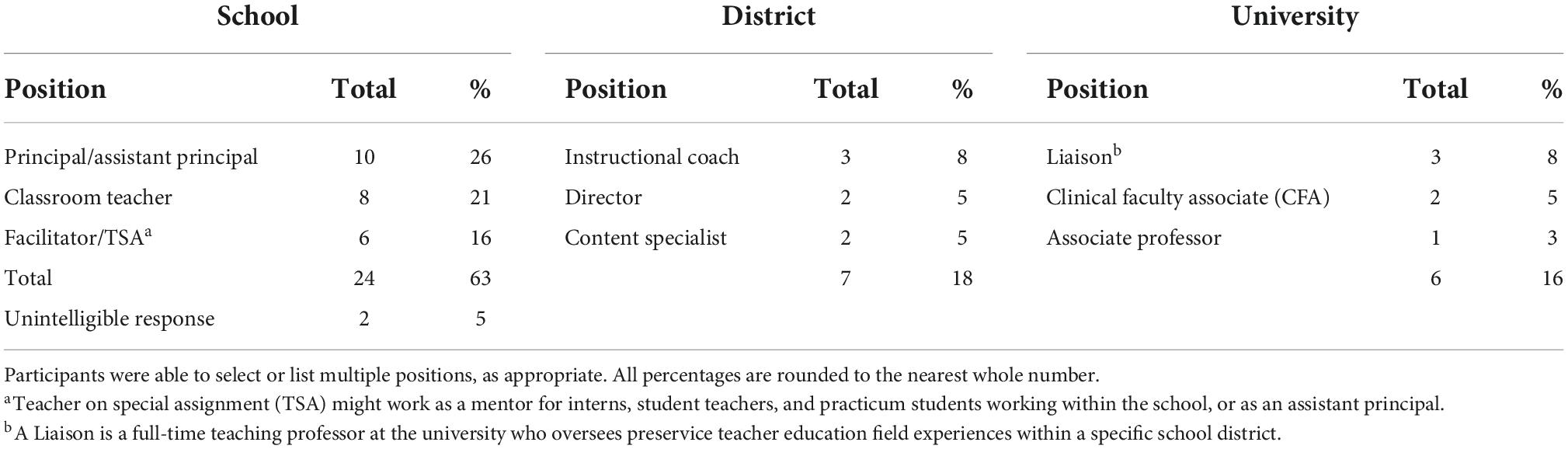

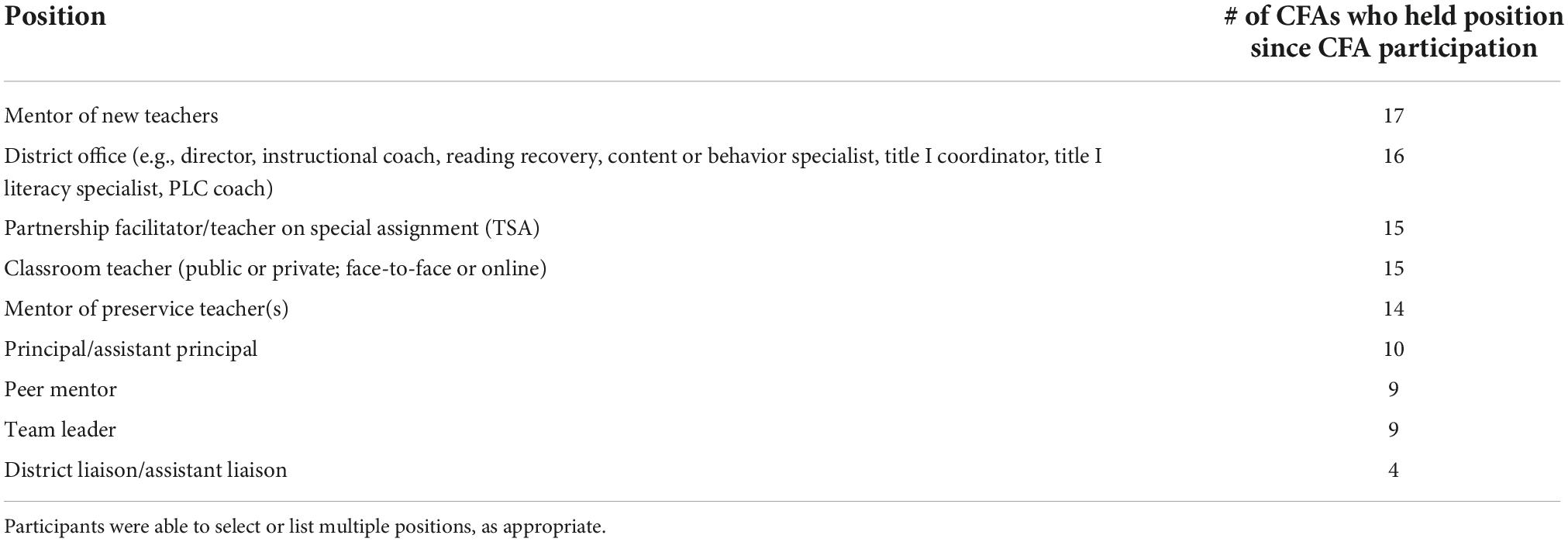

This section reports respondents’ current professional position in education (see Table 1) and positions held since their CFA work (see Table 2; n = number of responses not number of participants because CFAs may have held more than one position since their appointment as a CFA). Although some CFAs have worked as classroom teachers since being a CFA (n = 8; 21%), a majority of the respondents have assumed leadership positions at the school (n = 16; 42%) or district (n = 7; 18%) level. Others have since earned advanced degrees and accepted permanent positions at a university (n = 4; 11%) or have returned to the partnership university for a second CFA appointment (n = 2; 5%). Most CFAs have worked in multiple professional positions since their experience as a CFA and report that their CFA experience often led to administrative, leadership, or other responsibilities (e.g., peer or student mentoring) at the school, district, or university levels. See Table 2.

Clinical faculty associate responsibilities

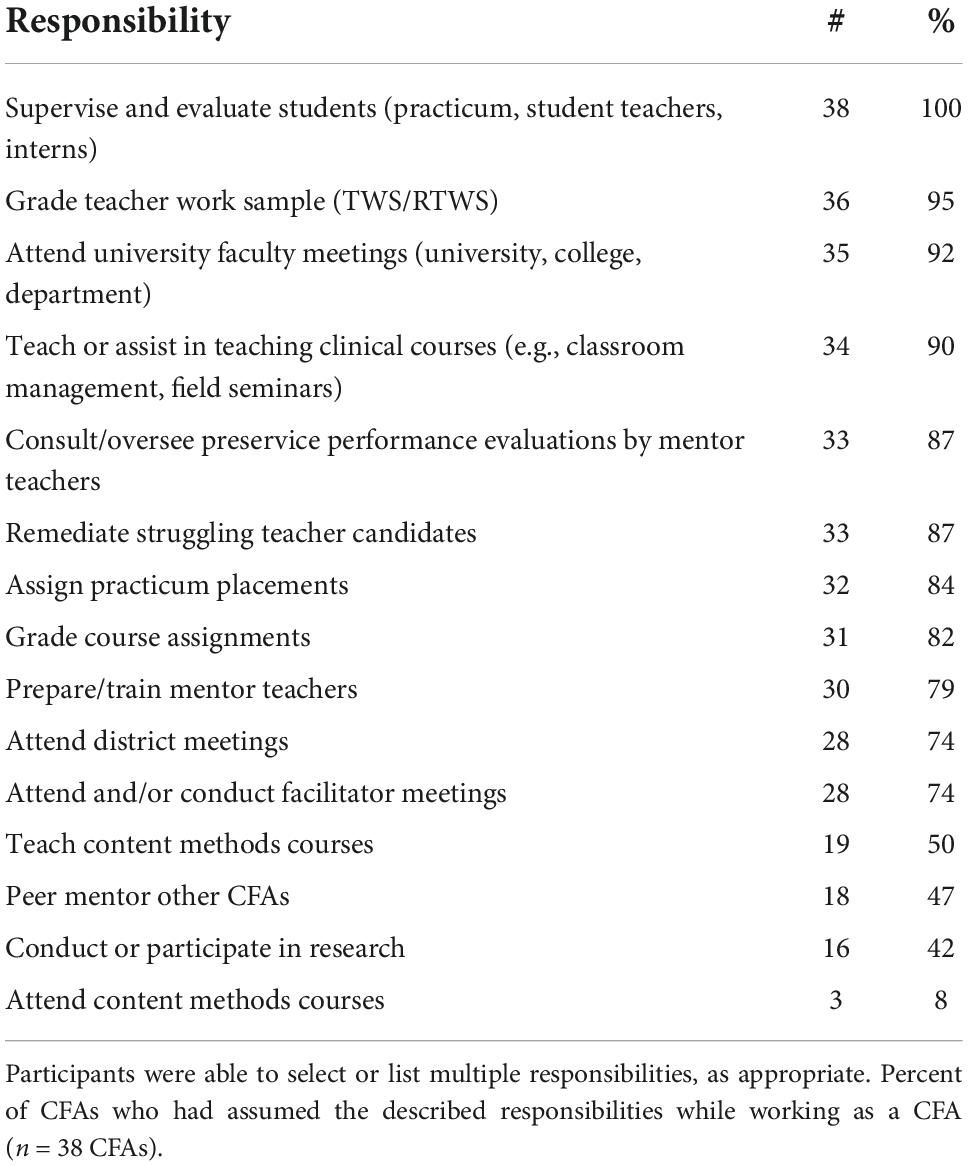

To describe the work of CFAs, the survey asked participants to select from a list of probable responsibilities, with an option to describe expectations not listed. Participants could select multiple responses, such that numbers and percentages reported in this and the following sections represent number of responses and not number of respondents. As anticipated, responses indicated that a majority of their work was as supervisors, evaluators, and mentors for teacher candidates in field placements (see Table 3). All respondents were also asked to teach and evaluate the work of teacher candidates in clinical courses (e.g., field seminars). Attending university and district meetings and working with mentor teachers were also commonly reported. Approximately half of participants were also asked to teach content methods courses (e.g., mathematics, science), mentor other CFAs, and participate in research with university faculty.

Clinical faculty associate opportunities, benefits, and challenges

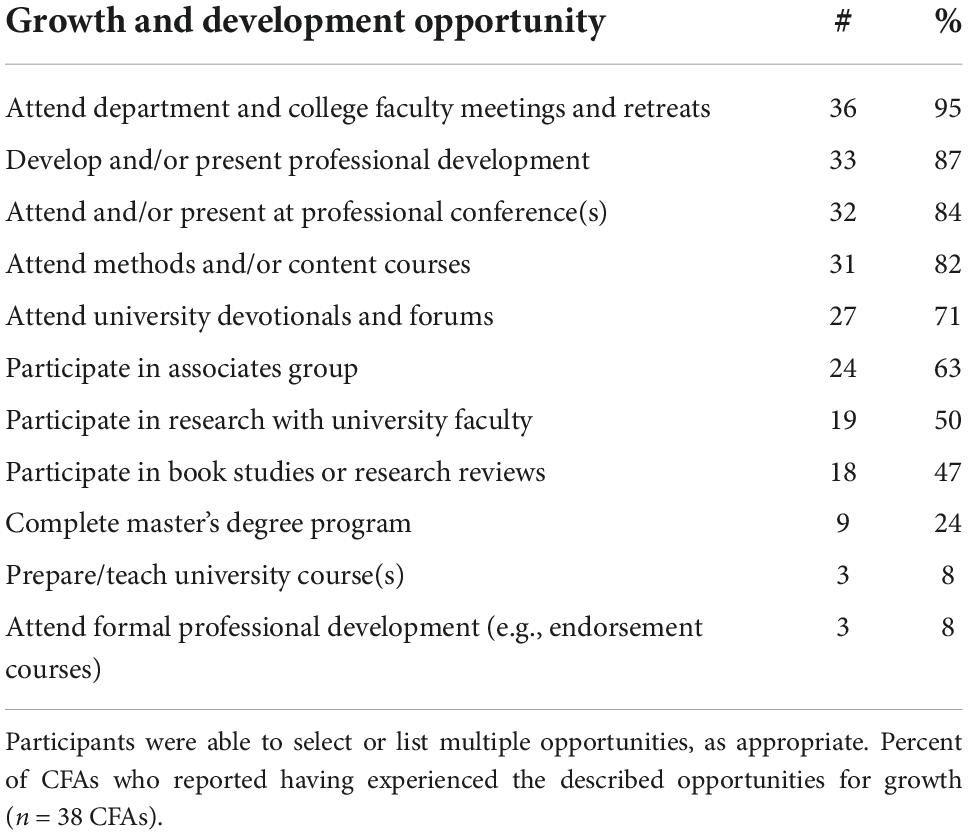

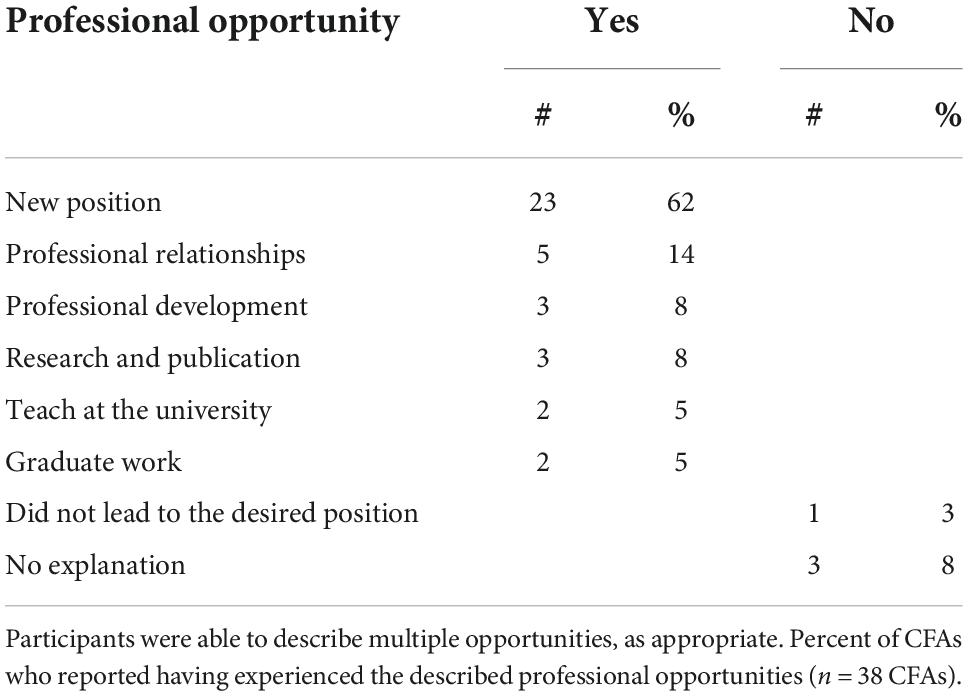

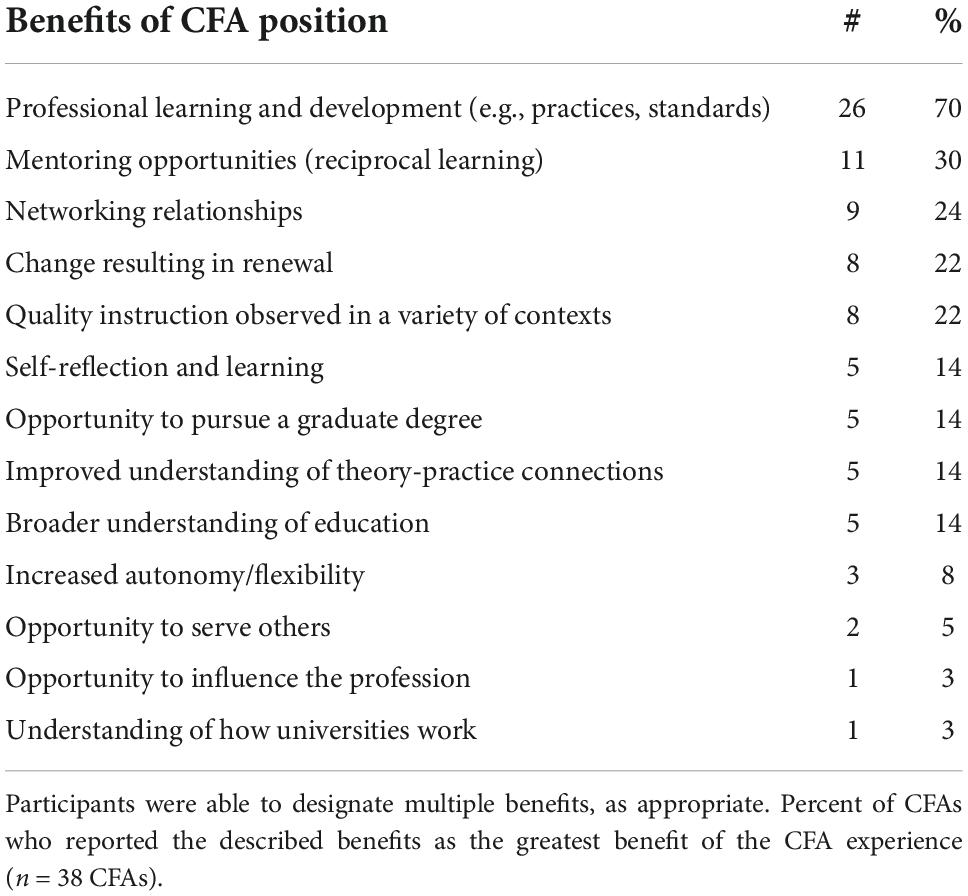

Open-ended questions prompted participants to describe perceived opportunities, benefits, and challenges they had experienced during their CFA experience. As depicted in Table 4, this work enabled them to participate in a wide variety of professional experiences, including (a) attending, developing, and/or presenting professional development; (b) attending and/or presenting at professional conferences; (c) participating in research; (d) teaching university courses; and (e) completing graduate degrees. A majority of participants also reported that working as a CFA opened additional professional opportunities for them (see Table 5) and introduced both professional and personal benefits (see Table 6).

In contrast, participants described challenges, both professional and personal, they faced in their work as CFAs. Organizing and managing time (30%; n = 11) and mentoring difficult or struggling students (27%; n = 10) were the professional challenges mentioned most often. Personal challenges were more diverse, including loneliness or a sense of not belonging, uncertainty regarding their role, or intimidation and discomfort negotiating a university culture (see Table 7).

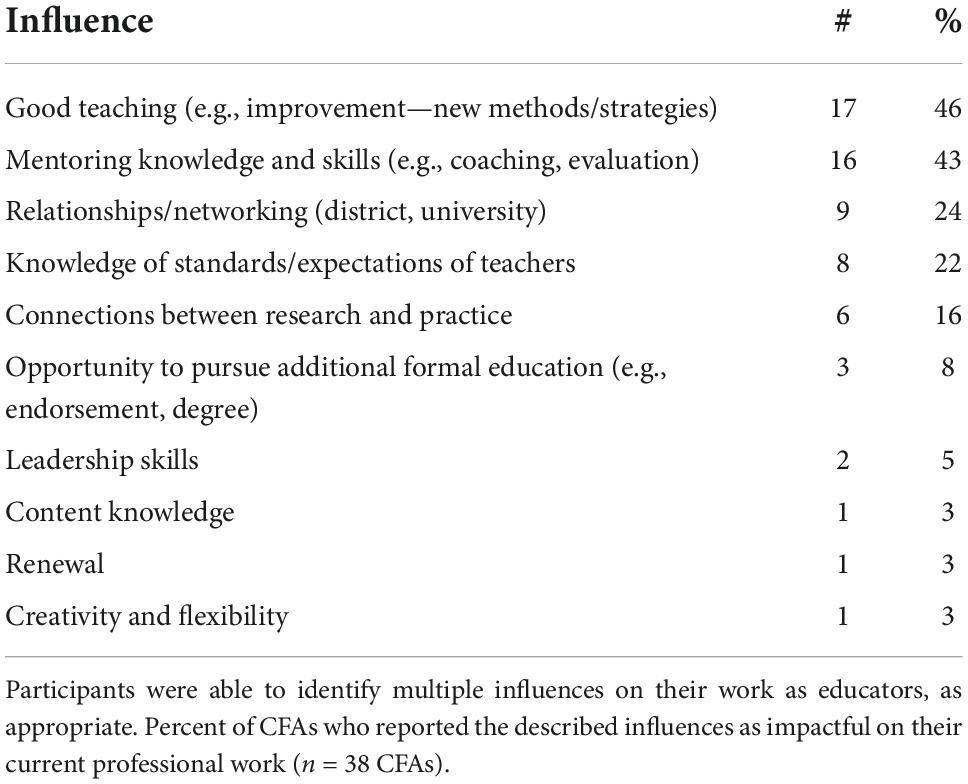

Overall influence of the clinical faculty associate experience

Finally, participants were asked to describe how their CFA experiences influenced what they have done or currently do in their work as educators. Notably, all responses were positive, with 46% (n = 17) of the participants indicating they feel they are better teachers, having improved their instruction as they learned new methods and strategies. Other comments focused on having improved their ability to mentor or coach, with a better understanding of evaluation (43%; n = 16). Participants also described having (a) developed important relationships and built professional networks; (b) increased their knowledge of standards and expectations for new teachers; (c) developed a better understanding of theory and practice; and (d) improved leadership skills, content knowledge, and creativity and flexibility (see Table 8 for a full representation of responses).

Representative cases

The experiences of four former CFAs, each from different, but representative, career pathways are described below. Each case highlights the educator’s pathway to becoming a CFA, the challenges and opportunities she experienced in her work as a CFA, and the impact the experience had on her professional work.

Heather: Classroom teacher

Heather had been a lower elementary grade (K-3) teacher for 22 years prior to working as a CFA. She had also earned a master’s degree and teaching endorsements in literacy and Reading Recovery. Additionally, at the time she was invited to apply for a CFA position in the ECE program at the university, she had been working for 3 years as a curriculum coach and was mentoring newly hired teachers in kindergarten through sixth grade across a few schools.

The university ECE program was short staffed when Heather began working as a CFA, which added to the challenges faced by most newly hired CFAs because she was asked to take on some additional responsibilities. These included coordinating school placements with the ELED program across two districts, counseling with students who were struggling in their field placements, planning and implementing practicum seminars, and collaborating with the university lab school on campus. Heather “had a steep learning curve [in her position as CFA], with little supervision or guidance.” She also taught courses on campus (both practicum and content courses), which she found “challenging but also very rewarding.”

As Heather became more and more involved with the ECE program, she found several additional opportunities for personal learning and growth. She reported one of the “most rewarding was building relationships with university faculty and becoming an integral part of the program” as she worked closely with the ECE students and faculty. She also “gained a new perspective on what students came to the classroom knowing but not yet understanding or having experienced.”

At the end of her experience as a CFA, Heather was asked to consider applying for a full-time clinical position at the university. Although she seriously considered the opportunity, it would have resulted in a substantial pay cut and negatively affected her retirement benefits. Ultimately, she decided to return to the classroom so she could have a direct impact at the school level, something that brings her tremendous fulfillment. She noted, however, that her experience as a CFA had “helped [her] in many ways, particularly in mentoring new teachers and teachers on [her] grade-level team, as well as in working with parents and families.” She also reported that one day she hopes to have the opportunity to return to the university.

Janna: School leader/Teacher on special assignment

Prior to her appointment as a CFA, Janna taught first grade for 10 years. She was well-respected in her school district and the district leadership often asked her to serve on district committees. She had also earned a master’s degree and an ESL teaching endorsement.

Although Janna recalled enjoying almost all aspects of her work as a CFA, which included teaching university practicum courses, presenting at professional conferences, and collaborating with faculty, she found it particularly “challenging to work with preservice teachers who were struggling or not fully committed to the profession.” She reported feeling “tension between her concern for the preservice teachers and worry for the children in the classrooms where these prospective teachers would work in the future.” As with many CFAs, Janna’s concern for the children in the schools was paramount.

Looking back, Janna described several ways her CFA experiences influenced her professional work. For example, she has felt better prepared to support struggling teachers, which is a significant part of her current position as a Teacher on Special Assignment (TSA–assistant principal equivalent with responsibility to oversee preservice teachers/interns assigned to the school) in an elementary school affiliated with the Partnership. In addition, Janna reported feeling she can continue helping to “bridge the theory-practice divide because [she] know[s] more about what is happening at the university and can help new teachers connect what they learned during their university programs with current practices in the schools.” Janna also works as an adjunct faculty member for another university in the state, something that brings her great satisfaction and was made possible, in part, because of her previous experience as a CFA.

Melissa: District content specialist

Having taught fifth and sixth grades for 9 years, Melissa had already earned endorsements in reading, advanced reading, and English as a second language, and had been accepted into a master’s degree program in teacher education, which she completed while working as a CFA.

Even with Melissa’s energy and experience, she found challenges associated with being a CFA. Unlike the specific job description of a classroom teacher, the work of the CFA was “quite loosely defined,” and the responsibilities felt unclear. “Managing time in the work day, in terms of load and scheduling,” was sometimes “impossible,” and “the amount of paperwork could be overwhelming.” Melissa was also asked to place preservice students in classrooms for clinical experiences with quality mentor teachers, which she found more difficult than she had anticipated.

As she continued to work through the challenges of the new job, however, Melissa found she enjoyed the opportunities for “networking with colleagues, researching with professors, attending professional conferences, and being fully immersed into the university community.” She was also able to “work closely with university professors” to complete her master’s degree and “develop lasting personal and professional relationships.”

In looking back on her experience as a CFA, Melissa reported that her experiences in teaching and supervising preservice students, conducting research, and working with education “experts” helped her “develop a broader perspective and enhanced her professional confidence and desire to continue to impact teachers and teaching.” When she returned to the district, she did so as the district Elementary Science Specialist.

Tricia: Return to university/Second term clinical faculty associate

Tricia began her career teaching special education in an elementary setting and later expanded her special education teaching license to include endorsements in teaching mathematics and gifted and talented. Before applying to be a CFA, she had spent a majority of her 18-year career teaching sixth grade (in elementary school) and had taught 1 year of seventh grade.

As a CFA Tricia found challenges she had not expected. Coaching “a variety of adult personalities and abilities” was more difficult than anticipated. Like Melissa, Tricia found “the load and scheduling demands for a CFA to be surprisingly stressful.” In addition to these managerial issues, Tricia was confronted with the “personal challenge of trying to reconcile and adapt her identity as an educator” to better conform to the idiosyncrasies of the university setting.

While working through these challenges, Tricia also found “great opportunities for personal and professional growth.” Attending and teaching preservice courses reminded her of “the connections between university course content and field experiences.” She also worked with college professors on various projects, including “collaboration on research and presentations at professional conferences,” work she found particularly stimulating, energizing, and informative.” Personally, she also described “warm friendships” that would “be difficult to leave behind” when she returned to the classroom.

Tricia was one of very few teachers from the Partnership overall who had been a CFA more than once, having returned to her district as a classroom teacher then applied for a second CFA opportunity. When asked how serving as a CFA impacted or influenced her professional work, Tricia mentioned that she now “felt better prepared to mentor and support other teachers” and had an overall “desire to make a change in [her]self and others to better the profession.”

Cross-case analysis

While the four interview participants in this study had been teaching in different school districts and differed in years of experience and specific work-related assignments, they came to the CFA position having followed a similar professional pathway. Each had extensive experience teaching elementary grades (Heather and Janna, lower grades; Melissa and Tricia, intermediate grades). Tricia was the only CFA who held a special education teaching license and had been teaching sixth grade special education. Additionally, each of these participating CFAs had sought education beyond her bachelor’s degree; all having earned one or more state endorsements, thus increasing their knowledge and skills in specific areas (e.g., literacy, mathematics, STEM), and two having completed graduate programs.

Challenges

All four interviewees reported facing significant challenges as they began their work at the university. A large majority of these issues seemed to be related to confusion about the roles and responsibilities of CFAs. In large part this was because each school district had slightly different expectations for the CFAs as conveyed by the full-time clinical faculty members serving as the liaison between the CFA, the university, and school district personnel (e.g., mentor teachers). The lack of universal definitions/descriptions of the CFA position, created challenges for many, if not most, of the incoming CFAs.

In addition to confusion about the CFA role, Heather, Melissa, and Tricia also mentioned that for them, the additional responsibilities at the university, overwhelming amount of paperwork, and complex scheduling were significant challenges as they jumped into the “deep end,” again with little or no guidance or training. All four of the interviewees found it difficult to manage the time associated with the teaching, mentoring, observing, and grading. Additionally, these CFAs found themselves learning to coach a variety of adult personalities and abilities, knowing that these teacher candidates, some of whom were struggling to meet program expectations, would soon be their colleagues in the schools. Tricia noted that these challenges even made her question her identity, as she found herself reinventing her view of what it means to be an educator. Heather and Melissa also felt this shift, although in slightly different ways. Heather carefully considered a full shift by accepting a full-time position at the University at the conclusion of her CFA experience; in contrast, Melissa began exploring options to continue her research in a doctoral program.

Opportunities

Interestingly, in spite of ongoing challenges identified by the CFAs, they also were able to highlight significant opportunities associated with their experiences at the university. All four indicated that they were able to develop relationships in various ways with educators at the university level. Being fully immersed in the university community allowed them to work closely with professors in creating and teaching courses, designing and facilitating professional development for teachers in partnerships schools, and making connections between university courses and clinical experiences for preservice teachers.

Each of the interviewees also described opportunities to attend and present at professional conferences, with Melissa and Tricia also mentioning opportunities to participate in collaborative research with professors in the department. Melissa felt strongly that her networking with professors had allowed her to complete her master’s degree and helped carve out a vision to work toward completing a PhD program. Heather indicated that her experience working closely with a university faculty member to support struggling teacher candidates enabled her to observe and participate in crucial and difficult conversations. These experiences strengthened her mentoring skills. Janna had been able to teach several preservice courses while working as a CFA, allowing her to collaborate with department faculty members and apply her own classroom teaching experiences as she taught content and skills to her university students.

Impact/Influence on subsequent professional work

Overall, all four CFAs interviewed in our study reported that their experience had a positive and lasting impact on their careers. Each indicated she was glad she had the experience working with preservice teachers and with university faculty.

Heather, for example, mentioned having gained “better insight into the preparation given to students and the need for mentoring new teachers in the schools.” As mentioned previously, she was offered a full-time permanent position at the university. Although she very much wanted to accept the offer, she found that it was not in her best interest at the time given the number of years she had worked in the school district and the retirement benefits she would forfeit. Thus, Heather returned to the district and is currently a lead teacher in her school and mentoring new and struggling teachers. In the future, however, she hopes to be involved in some capacity at the university level to help educate prospective teachers.

Janna found great importance in her work as a CFA in “bridging what is learned in [university] classroom content to application in the [elementary school] classroom.” She returned to her district and was assigned to an elementary school where she is a “teacher on special assignment,” mentoring new and preservice teachers. In this capacity, she is committed to working with experienced teachers to help them improve their practice.

Melissa attributed a “broader perspective” of education and teacher education gained as a result of her experience as a CFA. She believes that developing professional relationships and researching with university professors directly correlated to her rise in self-confidence as a professional educator. After working as a CFA, Melissa took on a new professional role in her district as an elementary content specialist and subsequently enrolled in a PhD program. She has remained in close contact with some of the professors with whom she worked at the university and her hope is to return to a university teacher preparation program as a professor.

As Tricia ended her second 3-years turn as a CFA, she shared that she was once again energized by and committed to the concept of “simultaneous renewal” espoused by Goodlad (1994) and the Partnership as she had been in her previous experience as a CFA. As a result of her experiences, she whole-heartedly supports the CFA program. Although she plans to return to her district prepared to continue helping new and struggling teachers and to assist others to be better mentors, she remained in her position throughout this study.

While each of the four women interviewed for our study came to the position with similar backgrounds, their experiences as a CFA differed. All were challenged by the work as it drew them out of their comfort zones in the public school classroom and forced them into situations where they were not sure of the expectations or how to perform the job. In the end, however, each identified and emphasized positive opportunities for growth and development both personally and professionally associated with working as a CFA.

Discussion and conclusion

Although the participants in this study reported a wide variety of experiences and perspectives, the overall consensus was that being a CFA was a positive, renewing, and revitalizing experience, with multiple opportunities for personal and professional growth. As noted above, we purposefully selected the four representative cases based on their professional positions at the time of the study (e.g., classroom teacher, school administrator, district administrator, and returning CFA) and not necessarily their experiences as a CFA. Thus, we did not fully capture the variety of experiences that were heavily dependent on contextual factors (e.g., school placement, program faculty vacancies, individual student needs) and individual experiences with particular students, faculty and schools. As a result, it is important to view the data (survey and interviews) together, as a whole.

Personal and professional growth through challenges and opportunities

Nearly all of the participants in the study reported facing some significant challenges as they began their work at the university as novice teacher educators see Cochran-Smith (2005), experiences common to many new or adjunct university supervisors who “must negotiate the unfamiliarity of the position and make choices about what kind of teacher educator they want to be” (Cuenca, 2010, p. 29), often without sufficient preparation (Korthagen et al., 2005). Most of these challenges were related to time/organizational management (e.g., managing the time required for the teaching, mentoring, observing, and grading; reporting/paperwork requirements) and mentoring difficult or struggling students. The interviewees elaborated on this learning curve, particularly as it related to mentoring struggling students. CFAs had to learn how to coach a variety of adult personalities and ability differences, which changed their personal perspectives about teacher preparation and mentoring new teachers in the schools. One CFA specifically mentioned feeling additional pressure knowing that these preservice teachers would soon be colleagues in the schools. Overall, these experiences seem to be highly varied and dependent upon the unique situation for each struggling student. Still, grappling with these instances did appear to have a significant impact on the CFAs and their overall experience working as a university supervisor.

In spite of the many ongoing challenges identified by the CFAs, they also highlighted numerous and varying opportunities associated with their experience working at the university. The most common benefits identified were related to personal learning and professional development. Many also mentioned mentoring opportunities and networking or the opportunity to build professional relationships.

Interestingly, all four interviewees highlighted relationships, indicating that they were able to develop various kinds of connections with educators at the university level during their time as a CFA. Being fully immersed in the university community allowed them to work closely with professors in creating and teaching courses, designing and facilitating professional development for teachers in partnership schools, and helping preservice teachers make connections between university courses and their clinical experiences. As Bullough et al. (2004) noted, these relationships, although time consuming and often “fragile,” are at the heart of a strong and healthy university public-school partnership and should be cultivated and valued as a critical part of any teacher preparation program (p. 518).

Nearly all of the participants in our study affirmed that their experience as a CFA had positively impacted their careers in education. Most respondents mentioned that they learned more about good teaching as they attended and taught university methods courses, strengthening their own knowledge and work as educators (e.g., improving teaching, learning new methods and strategies). Thus, the experience served as an opportunity for professional development (Hudson, 2013). Many participants also felt the experience improved their knowledge of mentoring and their ability to coach other teachers. Some also noted that the experience brought with it new professional opportunities that may not have been available to them had they not come to work at the university (e.g., graduate school, new positions in the district and at the university).

Notably, while the four CFAs serving as representative cases in this study came to the position with similar teaching backgrounds and professional aspirations, all had different experiences at the university and were prepared to accept different positions at the end of their term as a CFA, thus illustrating the many ways the experience can impact future professional work. Having former CFAs return to the school districts, the expected culmination of this model, is critical for renewal within the partnership and in the field of education in a variety of ways. Perhaps most importantly, most came away from the experience with an increased commitment to and investment in the preparation of teachers. We find this promising as we consider ways to improve our teacher preparation programs and strive to strengthen and renew our public-school partnership over time.

The CFA experience appears to be mutually supportive and mutually renewing for the CFAs, the university and the public schools. However, like most experiences that bring renewal, the CFA position involves struggle and growth. Many former CFAs reported difficulty in moving into a new position. Some felt lost in the new environment, others struggled to manage the schedule, and some grappled with their professional identity. This is, perhaps, not surprising given that successful university supervisors must often serve as bridge spanners as they liaise between the university and public schools. Such work requires a strong practical background with “a deep understanding of the clinical context to support a clinically-rich program” along with understanding of “theory to practice connections between coursework and fieldwork” (Bullock, 2012, as cited in Jacobs et al., 2017, p. 183). With one foot in the public schools and the other at the university, CFAs in our study sometimes found themselves in uncharted territory and even sometimes seeing themselves in a new light—as teacher educators.

It is important to note that not all CFAs experienced this transformation; however, among the study participants various new self-perspectives emerged. Among the four represented as case studies, one indicated coming to a fuller understanding of the particular needs of preservice and new teachers for expert mentoring and recognized her ability and desire to fill this need. Most were drawn in by their opportunities to participate with university faculty in research projects and conference presentations, and they choose to seek advanced degrees that may enable them to return to university work in a professorial position. These forms of redefinition lead to personal and professional growth for the CFAs as well as greater depth and understanding between partnership affiliates in the university and the schools.

Bullough et al. (2004) suggested that “contrasting cultures” between the university and public schools (p. 513) can make it difficult. Other models have been successful in easing the contrast, such as shifting the focus from university-and school-based supervisors to “preservice teacher supervisor” as suggested by Burns et al. (2016, p. 422). Regardless of titles as well as initial discomfort and adaptation, nearly all of the CFAs responding to our survey reported multiple professional benefits from inclusion in the univeristy. These included sitting in on university courses, participating in professional conferences, completing graduate degrees, engaging in research collaborations. Many found building and strengthening personal and professional relationships of greatest importance. Almost all reported that they enjoyed the challenges and felt overall renewal from the experience. Nearly half of the survey respondents reported that the CFA experience improved their teaching and enhanced their abilities as educators.

The overall sense of the CFA experience differs, in many ways, from other studies of university supervisors (McCormack et al., 2019). For example, many respondents in our study reported feeling connected to the program, university colleagues, and the partnership. However, more traditional models for university supervisors do not appear to provide the same affordances. Because the work of university supervision is so critical in the work of teacher preparation we need to continue to rethink how those serving in these roles are integrated into our programs and supported and renewed in their work.

Perhaps the most important work of teacher educators is centered in relationships, and the most significant renewal results from investment in others. Strong thriving partnerships balance self-interests of each partner with the well-being of the whole. Clinical faculty associates are critical to the success of the Partnership; especially when strong individual relationships are formed between university faculty and CFAs, as indicated by the CFAs themselves. As this happens the partnership flourishes and new opportunities for individual and collective growth emerge. Investments in the well-being and professional development of university supervisors strengthens their work with preservice teachers in the schools, and when CFAs return to their districts as leaders, as classroom teachers, or as a combination of both, benefits are compounded. However, as suggested by Bullough et al. (2004).

Collaborative relationships are fragile things, difficult to build and easy to destroy. Like friendship, they cannot be forced, even planned for with any significant degree of certainty. A serious commitment to building collaborative partnerships demands much: gradual formation of unusual ways of being with others and creation of new practices around which new and shared communities can be formed (p. 518).

Much more needs to be done to create and support these collaborative relationships that are mutually supportive: improving our practices at the university and in the public schools, and positively impacting the lives of each individual working in the partnership.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, Brigham Young University. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

KH-K and LS were the primary researchers with LE, MM, PT, HC, and JR being secondary researchers on this study. MM, PT, HC, and JR were all former CFAs and participants in the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bier, M. L., Horn, I., Campbell, S. S., Lazemi, E., Hintz, A., Kelley-Petersen, M., et al. (2012). Designed for simultaneous renewal in university-public school partnerships: Hitting the “sweet spot.” Teach. Educ. Q. 39, 127–141.

Bogdan, R., and Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon, Inc.

Bullock, S. M. (2012). Creating a space for the development of professional knowledge: A self-study of supervising teacher candidates during practicum placements. Stud. Teach. Educ. 8, 143–156. doi: 10.1080/17425964.2012.692985

Bullough, R. V. Jr., Draper, R. J., Smith, L. K., and Birrell, J. R. (2004). Moving beyond collusion: Clinical faculty and university/public school partnership. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 505–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.04.007

Burns, K. W., Jacobs, J., and Yendol-Hoppey, D. (2016). The changing nature of the role of the university supervisor and function of preservice teacher supervision in an era of clinically-rich practice. Action Teach. Educ. 38, 410–425. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2016.1226203

Byrd, D., and Fogleman, J. (2012). “The role of supervision in teacher development,” in Supervising student teachers: Issues, perspectives and future directions, ed. A. Cuenca (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 191–210. doi: 10.1007/978-94-6209-095-8

Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Teacher educators as researchers: Multiple perspectives. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.003

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education, 8th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 2nd Edn. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Cuenca, A. (2010). In loco paedagogus: The pedagogy of a novice university supervisor. Stud. Teach. Educ. 6, 29–43. doi: 10.1080/17425961003669086

Darling-Hammond, L., Hammerness, K., Grossman, P., Rust, F., and Shulman, L. (2005). “The design of teacher education programs,” in Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do, eds L. Darling-Hammond and J. Bransford (San Francisco, CA: Wiley), 390–441.

Duran, R. P., Eisenhart, M. A., Erickson, F. D., Grant, C. A., Green, J. L., Hedges, L. V., et al. (2006). Standards for reporting on empirical social science research in AERA publications: American Education Research Association. Educ. Res. 35, 33–40.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., and Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research: An introduction, 7th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gimbert, B., and Nolan, J. F. (2003). The influence of the professional development school context on supervisory practice: A university supervisor’s and interns’ perspectives. J. Curric. Superv. 18, 353–379.

Glanz, J. (1996). “Pedagogical correctness in teacher education: Discourse about the role of supervision,” in Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American educational research association, New York, NY. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Goodlad, J. (1994). Educational renewal: Better teachers, better schools. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Goodlad, J. (1999). Teacher education: The movement from omission to commission. Natl. Crosstalk 7, 1–16.

Hagger, H., Mcintyre, D., and Wilkin, M. (1994). Mentoring: Perspectives on school-based teacher education. Oxford: RoutledgeFalmer.

Hertzog, H. S., and O’Rode, N. (2011). Improving the quality of elementary mathematics student teaching: Using field support materials to develop reflective practice in student teachers. Teach. Educ. Q. 38, 89–111.

Hudson, P. (2013). Mentoring as professional development: ‘Growth for both’ mentor and mentee. Prof. Dev. Educ. 39, 771–783. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2012.749415

Jacobs, J., Hogarty, K., and Burns, K. W. (2017). Elementary preservice teacher field supervision: A survey of teacher education programs. Action Teach. Educ. 39, 172–186. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2016.1248300

Johnson, I. L., and Napper-Owen, G. (2011). The importance of role perceptions in the student teaching triad. Phys. Educ. 68, 44–56. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_208_19

Kilinç, H., and Fırat, M. (2017). Opinions of expert academicians on online data collection and voluntary participation in social sciences research. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 17, 1461–1486. doi: 10.12738/estp.2017.5.0261

Korthagen, F., Loughran, J., and Lunenberg, M. (2005). Teaching teachers – studies into the expertise of teacher educators: An introduction to this issue. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.007

Marable, M. A., and Raimondi, S. L. (2007). Teachers’ perceptions of what was most (and least) supportive during their first year of teaching. Mentor. Tutoring 12, 25–37.

Martin, K. L., Buelow, S. M., and Hoffman, J. T. (2016). New teacher induction: Support that impacts beginning middle-level educators. Middle Sch. J. 47, 4–12. doi: 10.1080/00940771.2016.1059725

McCormack, B., Baecher, L. H., and Cuenca, A. (2019). University-based teacher supervisors: Their voices, their dilemmas. J. Educ. Supervis. 2, 22–37. doi: 10.31045/jes.2.1.2

Miles, M. B., and Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Nguyen, H. T. (2009). An inquiry-based practicum model: What knowledge, practices, and relationships typify empowering teaching and learning experiences for student teachers, cooperating teachers, and college supervisors? Teach. Teach. Educ. 25, 655–662.

Odell, S. J., and Ferraro, D. P. (1992). Teacher mentoring and teacher retention. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 200–204.

Richardson-Koehler, V. (1988). Barriers to the effective supervision of student teaching: A field study. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 28–34.

Shroyer, G., Yahnke, S., Bennett, A., and Dunn, C. (2007). Simultaneous renewal through professional development school partnerships. J. Educ. Res. 100, 211–225. doi: 10.3200/JOER.100.4.211-225

Smith, T. M., and Ingersoll, R. M. (2004). What are the effects of induction and mentoring on beginning teacher turnover? Am. Educ. Res. J. 41, 681–714.

Stephensen, J., and Bartlett, S. (2009). Mentoring and teacher induction. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 4, 1–3. doi: 10.2304/rcie.2009.4.1.1

Valencia, S. W., Martin, S. D., Place, N. A., and Grossman, P. (2009). Complex interactions in student teaching: Lost opportunities for learning. J. Teach. Educ. 60, 304–322. doi: 10.1177/0022487109336543

Whalen, C., Majocha, E., and Van Nuland, S. (2019). Novice teacher challenges and promoting novice teacher retention in Canada. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 591–607.

Keywords: university supervisors, hybrid teacher educators, teacher preparation, reflection, qualitative research

Citation: Hall-Kenyon KM, Smith LK, Erickson LB, Mendenhall MP, Tingey P, Crossley H and Runolfson J (2022) Clinical faculty associates serving as hybrid teacher educators: Personal and professional impacts. Front. Educ. 7:1046698. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1046698

Received: 16 September 2022; Accepted: 31 October 2022;

Published: 06 December 2022.

Edited by:

Shaun Murphy, University of Saskatchewan, CanadaReviewed by:

Eliza Pinnegar, Independent Researcher, Orem, ON, United StatesMary Frances Rice, University of New Mexico, United States

Nasr Chalghaf, University of Sfax, Tunisia

Laura Sara Agrati, University of Bergamo, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Hall-Kenyon, Smith, Erickson, Mendenhall, Tingey, Crossley and Runolfson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kendra M. Hall-Kenyon, a2VuZHJhX2hhbGxAYnl1LmVkdQ==

Kendra M. Hall-Kenyon1*

Kendra M. Hall-Kenyon1* Lynnette B. Erickson

Lynnette B. Erickson