- 1Department of Teaching, Learning and Culture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, United States

- 4Department of Computer Science, University of Houston, Houston, TX, United States

This study narratively untangles an African–American student’s experiences in the throes of receiving a scholarship to study computer science and enter a future Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) career. Using the “wounded healer” metaphor as an interpretative lens, this work explores challenges the young adult experienced relating to his development, culture, contextualized learning, family interactions, religious beliefs, and self-identity. The student’s stories of teaching-learning, transforming, and healing instantiate the profound impact the grant-supported scholarship had on the youth’s development, life, and career trajectory. Additionally, new connections between narrative and metaphor are forged in ways that strengthen the sense made of teaching-learning, culture, and social interactions in higher education.

Introduction

Through ongoing interviews/focus groups with undergraduate/graduate students awarded scholarships from six National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) grants in the United States, remarkable plotlines illuminating how these scholarships changed students’ learning and lives emerged. Among the many elicited stories, one hope narrative stood out. This particular hope story demanded reflection and retelling, given the obstacles a young African–American overcame on his journey to becoming a STEM professional. In this work, we share the higher education experience of Kadeem Bello, a Nigerian immigrant who became an American citizen and began studying the STEM disciplines at a research-intensive university in a northern state before enrolling in computer science at a research-intensive university in a southern state. Kadeem’s personal narrative conveys the profound impact that NSF scholarships can have on students’ learning, lives, and career trajectories.

Before we unspool Kadeem’s wounded healer story, we present our literature review, theoretical framework, and research method. We next share the raw narrative Kadeem unraveled and reframe his narrative using the wounded healer metaphor as an interpretative lens to “shine a light” (Lamott, 2018, p. 95) on the challenges he experienced. Craig’s (2001) “monkey’s paw” article provided a model for how we might undertake the complex task of capturing Kadeem’s “being” and “becoming” (Greene, 1995) a metaphorical wounded healer in the throes of being awarded a scholarship to study computer science and enter a future STEM career.

Literature review

Scholarship grants

The genesis of NSF’s efforts did not grow entirely from altruistic roots. Rather, U.S. initially experienced an unsuccessful “race to space.” The country’s historical loss to a less technological nation threatened America’s global standing. Because of these necessity-driven security problems, “NSF is not interested in benefits; its main concern is with meeting its goals,” one of the grants’ co-principal investigators with 40 years in higher education informed us. Foundationally, NSF does not intentionally strive to enhance NSF scholarship recipients’ careers and lives. Indeed, as the co-principal investigator concluded: “NSF is not in that business.” Given that NSF’s purpose is to increase the productivity and innovative outcomes of the scientific community, the foundation introduced scholarship grant programs aimed at producing more STEM learners/workers, thus addressing the one-million job shortfall in STEM (Holdren and Lander, 2012). Hence, NSF’s funded scholarship grant programs are a targeted means to an anticipated end—with its intended outcome being increased STEM production/advancement and national/international security.

Instrumentalism

Amid this means-ends tension sits another important consideration: instrumentalism. From one point of view, instrumentalism means keeping the means-ends relationship at the forefront of action and not deviating from the plan. At a second level, instrumentalist-driven policies are foundational to technical-economic-educational development. Thus, funded grant programs emphasize the achievement of predetermined outcomes—the future employability of undergraduate/graduate students in STEM positions that will meet projected needs in the country’s labor market and secure the homeland from physical/virtual attack. This instrumentalist view forms a contrast with academic/personal growth and/or career development. While NSF’s ends are undisputedly important, the “radical possibilities” (Phelan, 2009, p. 105) of education are constrained because attention is not paid to “the distinction between utility and meaningfulness…” (Arendt, 1998, p. 157). The “logic of utility risks reducing” human beings “to a means to some end” (Phelan, 2009, p. 110). The pragmatic guiding forces behind NSF’s scholarship investments prove the narrative findings of this study to be all the more novel and compelling.

Theoretical framework

Five concepts underpin this narrative inquiry: (1) experience, (2) story, (3) metaphor, (4) identity, and (5) value.

Experience

Education and experience are intimately connected with each dialectically informing the other. In Dewey’s (1938) theory of experience, past experience links with present experience, which informs future experience. Unfortunately, not all experiences are instructive. Some may be miseducative. One paradox is that miseducative experiences can become educative if reflected upon. Another paradox is that experience works in both active and passive ways. Kadeem, for instance, accepted an NSF-funded scholarship with the intent of furthering his academic education/entering a STEM career. However, it was impossible to predict that the experience of the scholarship would change not only his career but his life. This is because experience has an all-encompassing effect: it shapes what students like Kadeem know, do, and who they are.

Story

Another of experience’s anomalies is that humans have no access to experience in its raw form except through modes like story. Narrative is almost the only way experience can be made known to self/others. Researchers championing narrative approaches maintain that their favoring of storied methods/forms trace to the centrality of educational experience. They claim there would be no need for story in the study of education if it was not for experience. Narratives, though, risk becoming “stuck” or “frozen.” They can become “ruling stories we do not dare step out of” (Conle, 1999, p. 21).

Thankfully, humans are able to make personal choices (Schwab, 1960/1978). As Weill (2013) noted, we can “apprehend stories… [and] awaken to new perspective[s] [and] to new possibilities…” (p. 152–160). Through rigorous reflection, we may “see that our misery [is] only… us looking through the stories with which we had defined the world and our difficult feelings simply are our body’s responses to those narratives” (p. 160–164).

Cases in point are those in the teen and young adult phases of life. They necessarily must engage in self-facing (Anzaldua, 1987/1999) to gain self-knowledge and become independent of their parents. Thus, they delve deeply into their family narratives that may or may not have negatively impacted their psyches. In the process, they uncover “damaged parents, poverty, abuse, addiction, disease, and other (un) pleasantries.” They eventually realize that “life … damages people” (Lamott, 2018, p. 59) and find “way[s] to be part of and apart from [these influences]”; they discover “way[s] of holding on and [ways of] letting go” (Stone, 1988, p. 244).

Metaphor

Metaphor is closely linked to experience and story. Humans come to know experiences through storytelling and metaphor-making (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980). Some consider metaphors condensed narratives (Ritchie, 2010); others call them “two sides of the same coin” (Arkhipenka and Lupasco, 2019, p. 221). Still, others claim “metaphors [i.e., wounded healer] contain narrative life [and] narrative potentiality…[and] are sparks of stories” (Penwarden, 2019, p. 256).

Identity

“Stories to live by” denote identity. Humans story/re-story their identities through revisiting/revising their experiences narratively. This process includes one’s cultural background. One’s identity is both personal and social. Identities are fluidly “formed and reformed by the [multitude of] stories [individuals are told] and which [they] draw upon in [their] communications with others” (Beijaard et al., 2004, p. 123). Identity is always in the making and never made (Greene, 1995).

Value

One’s values stem from a natural tendency to gravitate toward the good. In short, “values underpin what we respect and care about, and determine why we aspire to certain modes of life, actions and responses more than others” (Gill, 2014, p. 20). The capacity to lead a happy life is linked to “one’s capacity to create value—specifically values of aesthetic or sensory beauty, individual gain, and social good—in and from any circumstances” (Goulah, 2015, p. 254). Taylor (1989) considers values, “hypergoods,” that form our frameworks for judgments and decisions. Values/hypergoods allow humans “to equip [them]selves with…capacities to make strong evaluations in relation to what [they] do and how [they] are in the world” (Gill, 2014, p. 20).

A self-fulfilling life involves non-instrumentally valuable activities; that is, activities that do not satisfy means-ends purposes in the act of becoming one’s best-loved self (Schwab, 1954; Craig, 2013, 2017, 2020). Following Aristotle, values such as the appreciation of others, the ability to reformulate problems, being open to others’ views, and having a rich inner life are important because “mind, body, heart and spirit connections” fuel people’s being and becoming (Goodson and Gill, 2011, p. 115). Specific to Kadeem is the distinct culture of the African continent and its adherence to Ubuntu—the belief that “I am because we are,” a worldview that values caring, sharing, reciprocity, cooperation, compassion, and empathy.

Research method

Narrative inquiry

Narrative inquiry is the “experiential study of experience” (Xu and Connelly, 2010, p. 354) with narrative serving as both phenomenon and method. Story is a “portal through which a person enters the world” (Connelly and Clandinin, 2005, p. 477) and a “portal to experience” (Xu and Connelly, 2010, p. 352). In essence, narrative inquiry provides “a gateway…to meaning and significance” (Xu and Connelly, 2010, p. 356). It is “…a way of understanding experience. It is a collaboration between researcher[s] and participant, over time, in a place… in several social interactions” (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000, p. 20).

Narrative inquirers suspend judgment as participants’ experiences unfold. They are careful not to let their knowledge overpower what their research participants are discovering. They take preventative steps to ensure that their voices do not drown out or write over the experiences and voices of those in their studies (Clandinin and Huber, 2010). They leave their participants’ experiences and their narrative inquiries open to interpretation rather than forcing closure (Phelan, 2009). They know their work is inherently “unfinished and unfinishable business” (Elbaz-Luwisch, 2006). They are keenly aware that life continues despite research inquiries ending. They do not “collaps[e] disparate perspectives into unanimity” (Phelan, 2009, p. 111), take pattern as meaning, but instead embrace particularity, plurality, and unpredictability of actions, which reveals and “gives expression to what other approaches might think impossible to explore” (Phelan, 2009, p. 111), such as Kadeem’s identification of “hope” in his STEM study and life narrative.

Sources of evidence

This study’s evidence was produced through (1) interviews, (2) focus groups, (3) participant observation, (4) creating video clips, and (5) a digital narrative inquiry product. We presented Kadeem’s storied data in a digital narrative format first due to the delicate nature of his storyline (Lee et al., 2018). Creating the precautionary digital narrative before initiating this written narrative inquiry fostered a deeper trust between Kadeem and ourselves. We took this not-previously attempted approach because we were acutely aware of Kadeem’s vulnerability. We wanted to respect his boundaries while capturing and representing his lived educational experience with “candor [and] proper circumspection” (Nash, 2004, p. 31).

Tools of analysis

Broadening, burrowing, and storying and restorying were the analytical tools we used to interpret and seam together Kadeem’s narrative. We used these sense-making devices to transition our field texts into research texts. Broadening allowed us to include a brief history of NSF in the US and to consider the theory of action underlying its scholarship grant programs. Burrowing prompted us to examine Kadeem’s stories and how they unfolded over time and across hemispheres. Meanwhile, storying and restorying (re-selfing, Goodson (2013) calls it) animated circumstances that spurred Kadeem to change. Together, broadening, burrowing, and storying/restorying allowed us to explore Kadeem’s experiences in a “three-dimensional narrative inquiry space” (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000), which simultaneously accounts for temporality, personal/social interactions, and places.

A fourth tool, fictionalization (Clandinin et al., 2006), provided a way to mask Kadeem’s identity. We did this by slightly altering his description without significantly changing his story. Our action-cloaked secrets Kadeem may not want to be divulged.

Trustworthiness

Narrative inquiry research privileges narrative truth (Spence, 1984) and follows where stories lead rather than through prescriptive structures. This does not mean we are not concerned with historical truth. However, we entered into this inquiry and present our research texts narratively. Readers decide whether our research with Kadeem adds to their knowledge and is actionable.

Kadeem Bello’s wounded healer story

Kadeem Bello, a competitive scholarship recipient, is enrolled in computer science at a research-intensive university in Greater Houston. Though he currently exudes academic/career promise, Kadeem’s path to success has been arduous and circuitous. His self-description starts with his challenging Nigerian “middle-child” upbringing. Interviews revealed school experiences of being bullied because he was “sensitive” and “skinny/wore glasses.” Though the antithesis of his current appearance—strong, athletic—his past “nerdish-ness” was perceived as a weakness by peers and even his parents in his local cultural context.

While faith was integral to Kadeem’s childhood, his family’s faith culture seemed more structurally litigious than grace-focused. Kadeem recalled an over-emphasis on churching:

Yeah, it was a Christian family, so we did lots of church activities, and the cool things that… religious people do, you know, go to church and go to…Bible studies…we spent so much time on that…

Aligned with their religious beliefs, Kadeem’s strict parents meted out physical punishment, supporting the culturally accepted adage of “spare the rod, spoil the child.” Kadeem recalls punishment as a regular part of his childhood experience, “I would come home, I would get beat up. It was harsh growing up….” Though the physicality of such punishment is at odds with current Western mores, Kadeem affirmed that it was normal “maybe 10 or 20 years ago [when it was] still okay to beat up your child…” in Nigeria. It was for these reasons, and others, that Kadeem began to “question everything [he had] come to know” and learned “from watching American movies, which gave insights into other ways of living” cataloged in his own lived experiences.

Understandably, the intense focus on religion juxtaposed with bullying at school and corporal punishment at home, put Kadeem on a sojourn down a dark path “already heading toward depression.” Fueled by idealistic western media images, Kadeem independently traveled to America to seek a new life; however, his fresh start in the northern state introduced new challenges:

And when I came, my parents sponsored it, right? But once I got over here, I wanted to support myself and become independent. But… I overworked and I was even getting more depressed and well… I was diagnosed with major depression.

Fighting for his life after attempting to end it, Kadeem desperately called his self-proclaimed “angel,” a white female professor he met on his flight from Nigeria, for emergency help. This “angel” brought him into her family where he was invited to live and heal while struggling with mental health issues. He confided,

She helped me a lot. One time when I was going to hang myself, she was the one I called…she even let me stay at her place. She’s married with a little kid. She helped—she did so much for me.

When Kadeem Bello became healthier, his uncle brought him to Texas; however, not long after Kadeem settled in, tragedy struck again. This time, a devastating flood destroyed his car, and he was forced to abandon his previously affordable, no longer inhabitable, apartment.

Kadeem: So last year,—okay, I had a friend. I was staying at his place, and I was paying about $500. So that was after one of my last leases expired, because I didn’t have enough () to get another place…So, I stayed at his place. And around May 30, he was flooded out Greater Houston. That was when all this flooding… started. I lost my car, so that…ruined everything… because May 30 is just when summer is really beginning, and that’s when you plan to save money…. So that messed up everything.

Without financial means to secure a new lease or cultural capital to find more affordable accommodation, Kadeem took to couch surfing which worsened his depression. Without the good sleep essential to mental health, Kadeem lived in a friend’s storage space for months, homeless, hot, and frequently without hope. But, due to his lack of work and his inability to achieve future goals without negative financial indebtedness, this situation seemed to be his best option:

So, my storage unit is quiet and it’s dark. I mean, around August it was hot, so it was kind of a struggle…But in October, then the weather changes, it was pretty comfortable. October through March, the weather was pretty good. It wasn’t a bad place to sleep. But it gets spooky and rats are running around.

Kadeem then shared his most unnerving experience:

I got scared one time. Someone was trying to break into people’s storage units. So I called the cops and that didn’t do me good, because it made me expose that I was sleeping in that unit…but I just decided to keep on staying there to just save up some money.

Despite being more financially secure, Kadeem continued to stay there to save money to live near a school in a future “safe area.” Kadeem also reflected on his future and career/life goals:

I was soul searching… I questioned many things, and felt I needed to change. I felt like the only reasonable way for me to really live in this world was if I did things more realistically, more logically. If I was more rational rather than accepting the belief system that my parents told me… I never really had any real reason (why) I’m doing this or that.

Kadeem also began to question his own religious beliefs in relation to his experiences. Though his initial reflective analysis led to a desire to “step away from that” with a view that “religion is really bad for the world,” he eventually decided against extreme views, declaring “I’m not an extreme kind of person…because my belief in reason won’t let me stay in such extremes.” He further elucidated his evolving scientific perspective by delving into his current religious preponderances, “If I’m going to be a scientist, I have to think like a scientist. And scientists…consider possibilities… You have to know something for certain… I had to keep the [God] door open.”

Relentless, he Kadeem persevered and continued taking classes toward his eventual goal. Concurrent with Kadeem’s homelessness and his identity growth experiences, by purely universal intervention and a great measure of luck, Kadeem was introduced to the NSF-sponsored scholarship program in a class. The scholarship program offered an avenue to greater financial and life stability. The scientifically grounded field of computer science offered him the logical transmutations of meaning he sought and yearned for. After being awarded the scholarship, Kadeem intuited the benefits to his mental health. Once he received the first installment of his scholarship, Kadeem reflected on the now positive trajectory of his future, “[The scholarship] has given me hope,” he declared, “Over the past year, I was pretty much sleeping in [a] storage unit…that is, until last week. The scholarship has allowed me to hang in there; I found hope in knowing that something is coming.” Kadeem reflected backward on the tremendous burden the scholarship lifted, citing, “it took so much stress away” and helped greatly to ease his depression. When asked about other benefits, Kadeem recalls site visits (i.e., Hewlett-Packard), but most genuine perhaps was this exchange about the grant program’s helpfulness:

Researcher: So, this has benefited you greatly then?

Kadeem: Oh, hell, yes.

Kadeem also revealed his “aspiration to open up a lab” so he can do “helpful research.” He further acknowledged that “the scholarship heightened [his] sense of compassion” and birthed a desire in him to heal others with his long-term goal of being one who shares learning resources with other African children in need. Kadeem grounds his desire to do research within a human frame, asserting that “we humans will be better off if we value research” more than profit, and that we “all do better when we all are better,” a phrase reflecting the Ubuntu belief that “we should care about the improvement of others,” and not just be “concerned about improving ourselves.” The compassion afforded Kadeem via the STEM scholarship seeded and expanded his generosity toward others. No longer living in the clutches of undiagnosed depression, Kadeem claimed he is a “wounded healer and ambassador,” an agent of change bringing hope to others in crisis.

Unpacking the wounded healer metaphor

The wound is where the light enters in—Rumi (2004).

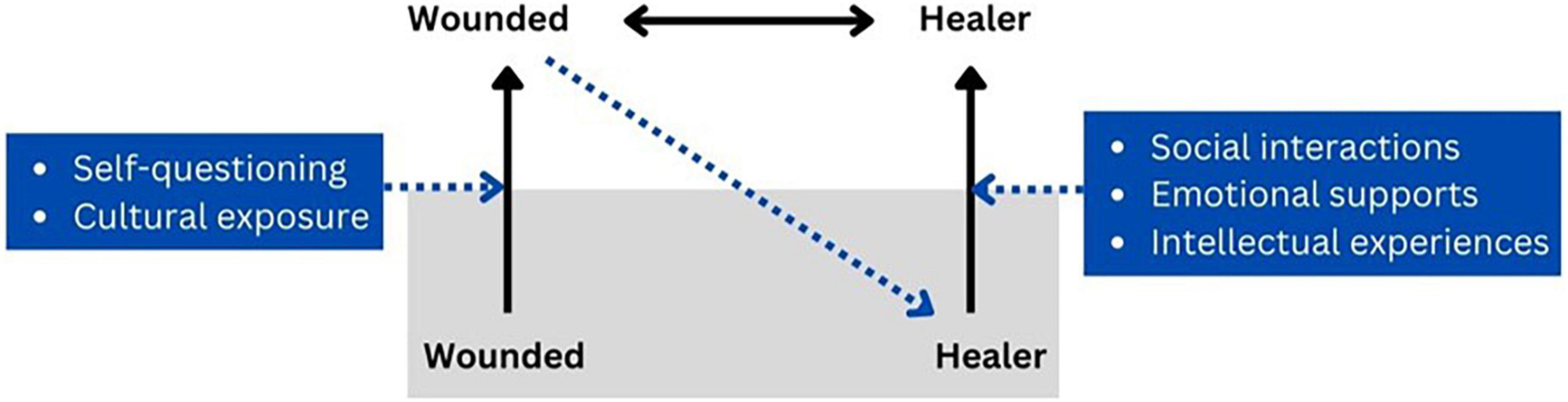

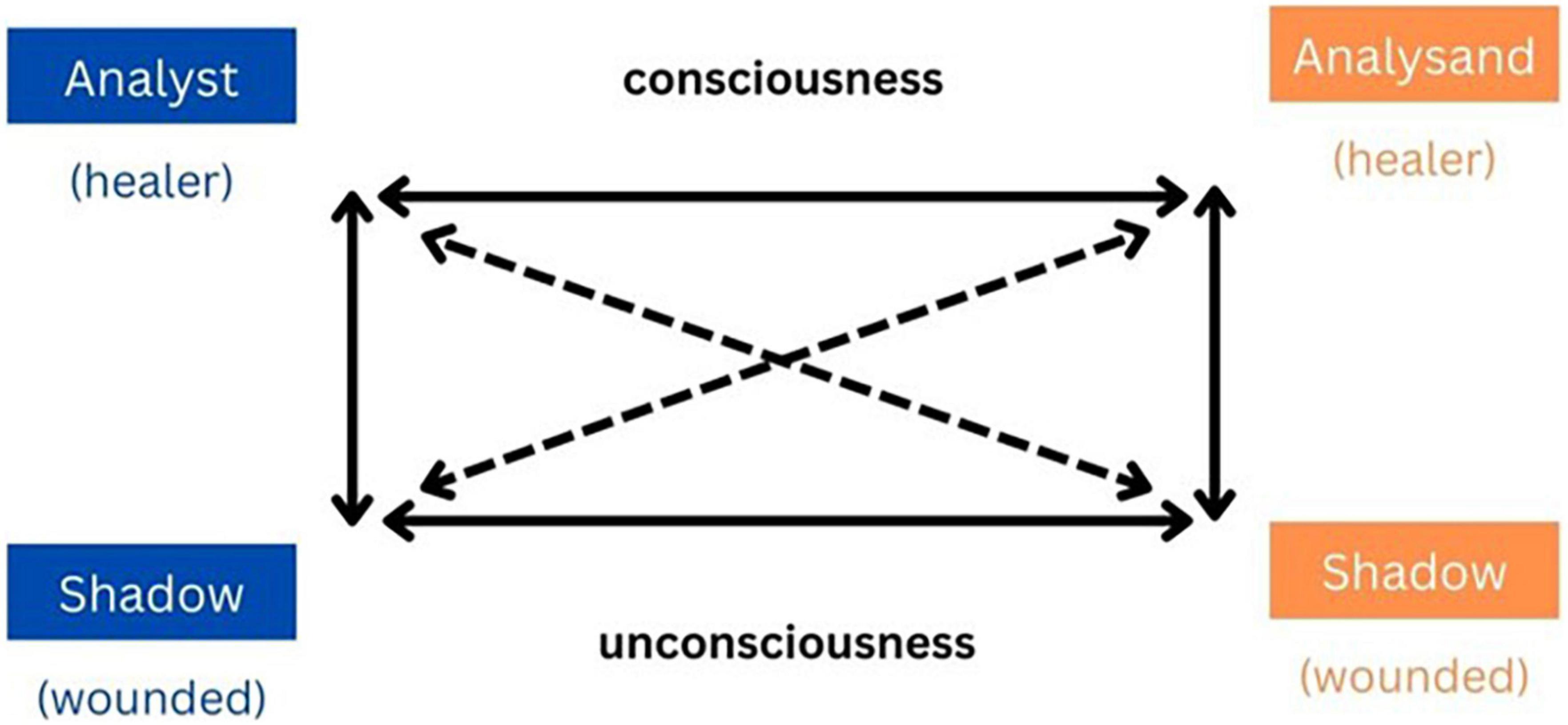

The image of the wounded healer that Kadeem Bello called forth in his narrative is a psychological construct of Carl Jung. It is the most well-known of Jung’s 12 archetypes, the one most spread in society’s mainstream and pop cultures, which we presaged through using spoken word excepts. The driving force behind Jung’s wounded healer is that analysts treat patients with wounds because analysts themselves have been wounded (Figure 1). It follows that those previously healed can best tend to others’ wounds. Psychic healing requires companionship rather than a hierarchical relationship. Jung shared Freud’s response to the wounded healer archetype:

Figure 1. The relationship between the healer and the wounded (based on Frith Luton, 2019).

Freud…accepted my suggestion that every doctor should submit to…analysis before inserting himself [sic] in the unconscious of his [sic] patients for therapeutic purposes…. We could say… that a good half of every treatment…consists in the doctor’s examining himself, for only what he can put right in himself can be right in the patient. This, and nothing else, is the meaning of the Greek myth of the wounded physician (Jung, 1953, Collected Works, Vol. 12, p. 115–116).

Jung traces his well-known construct to Greek mythology, specifically to the Chiron myth about the centaur wounded by an unintentional arrow from Heracles’ bow. However, Chiron did not die. Rather, he experienced agonizing pain for life. Because of his wound, Chiron became celebrated as a legendary Greek healer. Later, an orphan was placed in his care. That orphan became the Greek God of Healing because he used harmless Asklepieion snakes in healing rituals. The single serpent wrapped around a cypress branch—the widely recognized Rod of Asklepios—symbolizes medicine today. The wounded healer myth, which Jung attributed to the Greeks, exists in other cultures as well (i.e., African Shamanistic tradition, the Muslim physician Al-Raz, the Jewish Talmud, children’s novel, Pollyanna). For example, the quote from Rumi, the Persian Muslim poet, indicates how widespread the wounded healer metaphor was prior to the Greeks, who are credited with forming the roots of western civilization.

Retelling Kadeem Bello’s wounded healer story

Kadeem’s story is now re-told and reframed through the unpacked wounded healer metaphor, on which subtle nuances of his storied experience are captured. First, based on Jung’s archetype, we shine the spotlight on how social, emotional, cultural, and intellectual contexts surrounding the psychologically wounded boy from Nigeria served to activate the inner healer. We then couple this psychoanalytic unraveling of Kadeem’s story with the Chiron myth, interpreting his “being” and “becoming” as not only a wounded healer but a “wounded storyteller” (Frank, 1995). It further reflects the reciprocal aspect of Kadeem’s wounded healer/storyteller story.

Jung’s wounded healer polarity (Figure 1) illuminates the paradoxical coexistence of the wound and the inner healer in Kadeem’s story to live by. When revisiting his narrative with this in mind, we came to view it from a different angle. As shown in Figure 2, Kadeem’s “being wounded” and “being the inner healer” is disconnected when they are left unconscious. When it comes to his unconscious woundedness in his childhood story to live by, his wounded being is likened to that of Chiron. Like the arrow causing Chiron’s wound was accidentally discharged from Hercules’s bow, his parents’ use of corporal punishment left Kadeem scarred unintentionally.

The unintended, unconscious woundedness bubbled to the surface of his consciousness when Kadeem’s being “one of those sensitive kids” who used to “question everything” was strengthened by exposure to American culture through media.

Put differently, the self-questioning and cultural exposure enkindled the existential acceptance of Kadeem’s woundedness and sharpened his awareness of “narrative incoherence” (Carr, 1986) between his ideal story to live by and his lived story. Accordingly, the conscious attention to the ontological discomfort activated Kadeem’s thirst to be healed and led him to leave the African continent in seeking “other ways of life.” Differently speaking, Kadeem’s sense of his own woundedness awakened his hidden inner healer and provoked his story to live by to shift into his story to leave by Clandinin et al. (2009).

Although Kadeem had an increased awareness of the intrapsychic healer, his woundedness became worsened due to the unstable financial situation he experienced with the severe flood in America, the land he had dreamed of settling down in to actualize his ideal story to live by. Fortunately, already uncovered unconscious woundedness enabled Kadeem to seek an external healer, a campus therapist who could strengthen his inner healer. For Kadeem, the relationship between his external and inner healers was not restricted to the therapeutic realm. In addition to the prescription the doctors issued him, what actually facilitated his inner healer to be integrated into consciousness were (1) social interactions with others, including his official mentor in the scholarship program, the advisor for international students, and the “angel,” (2) emotional supports from them, and (3) intellectual experiences he had as an NSF scholarship student. Significantly, the knowledge he gained from the scholarship program experience brought greater awareness and integration of Kadeem’s own wound and inner healer; he began to see his woundedness “more realistically, more logically” through the interdisciplinary lens of computer science and neuroscience.

Growing as an integrated and conscious wounded healer, Kadeem now dreams of becoming a computer scientist who heals the other wounded with more scientific knowledge helping to see his wound through neuroscientific investigations and “helpful research.” Kadeem’s spirit of Ubuntu parallels the paradox of the mythological wounded healer, Chiron; though Chiron has to carry his incurable wound with him, he can cure others using “the knowledge of a wound in which the healer forever partakes” (Kerenyi, 1959, p. 98–99). Further, Kadeem’s becoming a wounded healer revealed his identity as a “wounded storyteller” (Frank, 1995), an associated dimension of wounded healing. In exchanges of narratives through the interviews and the digital narrative inquiry process, Kadeem’s sharing his painful but hopeful story was a wish that the dissemination of his wounded healer story would inspire wounded others to uncover their own unconscious inner healer. Also, the consecutive telling/retelling of Kadeem’s experience through traditional and digital narrative inquiry fostered iterative reciprocal healing between the participant and the authors. In the open-ended interview and the digital storytelling situations, the image of Kadeem’s wounded healer was narratively projected onto us and activated the wounded healer polarity in ourselves. We each became consciously aware of the woundedness and the hidden healers within ourselves while attending to Kadeem’s wounded healer narrative.

Emergent themes

In Kadeem’s hope story and in our re-telling of his narrative using Jung’s archetypal metaphor, five overarching themes surfaced: (1) continuum of life; (2) role of the stranger; (3) narrative, trauma, and identity; (4) metaphor, narrative and truth; and (5) arrogant perception-loving acceptance of others and their worldviews.

Continuum of life

Kadeem did not arbitrarily decide that he would be a wounded healer and an ambassador of hope to African children in crisis. Rather, events in his unfolding life conspired together to give shape to this plotline that developed amid his past–present–future life continuum. As King (2003) reminded us, “memory of the past is continuously modified by the experiences of the present and of the ‘self’ that is doing the remembering” (p. 33). Through this rigorous, reflective process requiring Kadeem to think backward, forward, inside, and out (Clandinin and Connelly, 2000), his storied version of the wounded healer found a voice and gradually surfaced as an intimate part of his being. The wounded healer narrative necessarily had antecedent cultural, familial, and personal experiences that laid the foundation for its telling (Sacks, 2017). Kadeem’s description of his bookish appearance, his identification of bullying and harsh physical/mental punishment, his positioning as a middle child (angry, wanting to fit in), and his fervent desire to break free from the excesses of his parents’ religious practices set the stage for him moving to the U.S. to pursue his higher education. His expressed purpose was to create a brighter future. However, much to his chagrin, shadows from his past accompanied him on his transnational journey. Not only did he carry suitcases to America but his “complicated” Nigerian life also accompanied him like carry-on luggage filled to the brim with unresolved baggage needing to be sorted out (Penwarden, 2019). In Kadeem’s new setting—an ocean away from his family—and working inordinate hours so he would not feel financially indebted to his parents, he fell into a deep depression. The massive shifts he experienced while changing continents unhinged his withered story to live by while stoking his story to leave by, creating narrative wreckage for which psychological attention was required. Kadeem realized he had no other choice but to deal with his psychic upheaval because it curtailed the healthier, more productive life he had in mind for himself.

Role of the stranger

Kadeem’s turning point in his narrative paradoxically involved a stranger, a white female professor seated beside him on his flight to the U.S. That professor provided him with food, shelter, and advice. His “angel,” as he called her, helped him to come to terms with his depression, encouraged him to have it medically treated, and assisted him in learning the conditions (i.e., proper sleep habits) he needed to manage it. Kadeem’s female stranger incidentally was not unlike Schwab’s stranger—a man at a train station who strangely enough gave that 15-year-old boy money to escape his parents and his hometown and to travel to Chicago where he would commence his career as one of the U.S.’s most-renowned scholars. Kadeem’s stranger—like Schwab’s stranger story, which Cheryl Craig laid alongside Kadeem’s story in the first interview—served as a harbinger of change, a junctional figure who walked alongside Kadeem as he came to grips with his mental health condition and his ghosts from the past. Interestingly, Kadeem’s interactions with this professor, like Schwab’s interactions with the stranger at the train station, were only for a fleeting time. When we later questioned whether he would contact the professor, Kadeem indicated that he would follow up after graduation. He wanted his “angel” to know that her assistance had brought him successfully full circle and that he would soon be embarking on a career merging neuroscience and computer science. We also noted that Kadeem’s use of computer science to study the nervous system and psychiatric disorders uncannily resonated with his biography and his experiences. His area of emphasis likewise fulfilled the familial and cultural expectations placed on him as a first-generation immigrant hailing from the African continent where being a doctor—or a “double doctor” (Kadeem’s dream)—personified the achievement of the American Dream, a plotline with which Kadeem had been long enamored.

In addition to Kadeem’s “angel,” other strangers played key roles: (1) his uncle and (2) our research team. Identifying a full-blood relative as a stranger initially seemed illogical. However, that was the case. While his uncle accompanied Kadeem from Chicago to Greater Houston, his uncle was not on the scene from that point onward. It is entirely possible that his uncle and his family also suffered hardship during the gulf coast debacle. But it could also be that Kadeem cast his uncle as a third parent in his life story, an individual he intentionally kept at arms-length because he feared his uncle would act as a conduit channeling news to his parents. As researchers, we will never know whether these two options or some other possibility were at work. But we do know from the literature that strangers have played pivotal roles in people’s stories since the beginning of time as sacred books from all belief systems attest.

The third manifestation of the stranger was our research team. The germinal seed for this article was planted in the initial interview that Cheryl Craig conducted with Kadeem Bello. Craig used a battery of open-ended interview queries mirroring the questions she asked other participating NSF scholarship students. However, it seems the “narrative environment” (Baboulene et al., 2019, p. 33) she created provided the conditions Kadeem needed to publicly own his experiences leading up to his voicing of his emergent healer/ambassador of hope plotline. In her field notes, Craig wrote that Kadeem’s story seemed to “spill out” because it had to. Put differently, both interviewer and interviewee shared “a [sense of a] …deep arrival of something unavoidable” (Lamott, 2018, p. 135) in their inaugural interaction. In retrospect, it seems Kadeem had reached a turning point and desired to “make the inchoate intelligible” (Kerby, 1991, p. 45). He was ready to claim his narrative authority of his life experiences following his recovery from debilitating depression. Critically important to his improved condition was his access to university counseling services, a healthcare plan that paid for medications, an apartment with optimal sleeping conditions, and an academic environment where his professor welcomed and encouraged his questioning, all conditions made possible by his NSF-funded scholarship.

Still, we, as researchers, were understandably cautious. We were deeply aware that people not only “need to be careful of the stories [we] tell” but also “watch for the stories [we] are told” (King, 2003, p. 10). We had no interest in crafting a hot story (Lamott, 2018) that capitalized on Kadeem’s fragility by instrumentalizing him in the research process. As a team, we decided to first give Kadeem’s narrative back to him in a digital narrative inquiry form. After viewing his narrative devoid of personal photographs and with an anonymous storyteller speaking his words/feelings into being, Kadeem could decide what he wanted told/not told about his life experiences or declare that he did not want his autobiography shared at all. We observed as Kadeem intently viewed the digital narrative footage. To our relief, he found no objection. He added points of clarification, granted his permission a second time around, and authorized the subsequent writing of this article. Kadeem’s continuing approval sealed our continuing research relationship. It also determined the degree to which he was ready to meet a world of strangers by presenting his life thus far (Penwarden, 2019). He was eager to show that he had changed his life narrative by personally dealing with depression, its sources, and its triggers, and, in the process, transformed the quality of his life while bettering his life chances (King, 2003). Sharing his journey with others made his life “more livable” (Popova, 2013, p. 336). Time taught both Kadeem and us that his wounded healer narrative instantiated how he had “all that [he] needed to come through…” (Lamott, 2018, p. 189). Through Kadeem Bello’s telling/re-telling and his drawing on his bred-in-his-bones understanding of Ubuntu, he “claim [ed] the events of [his] life [and] made [his self] [his own].” In possession of all he “[had] been and done,” he no longer needed to tell cover stories to family or strangers. The counter-story he had crafted alongside his counselor meant he could unapologetically be “fierce with reality” (Scott-Maxwell cited in Palmer, 2018, p. 173)—even its most painful parts.

Narrative, trauma, and identity

Kadeem’s eventual release of his story to the world would not have occurred had he not dealt with the narrative incoherence previously happening in his life. He had been a victim of bullying and physical/psychological punishment. He attributed both phenomena to his culture/generation/time in which his childhood unfolded in Nigeria; he also connected his parents’ punishment to their fundamentalist religious beliefs. In Kadeem’s view, his country’s culture, coupled with his family’s religion of choice, had fixed him (Hekman, 2000) in ways contrary to how he would personally story/position himself as a developing youth. These “single stories” of Kadeem were “dangerous and caused harm” (Adichie, 2009) to his sensitive childhood story to live by. The narrative his culture and parents bestowed on him was what he wanted to shake off later in life. He organically knew that some stories he had been given had positively formed him (i.e., his focus on high achievement and his understanding of Ubuntu), while others (i.e., bullying, physical/mental abuse) had unintentionally disformed him (Sacks, 2019). “Others’ words,” to cite Beckett (1953/1958), had become who he was and what he was made of. Such words had served as “‘swords’ to attack his diminishing sense of self” (Popova, 2019, p. 356). The continuous echoing of these “stock-plots” (Lindemann Nelson, 2001) drowned out the story he was attempting to live by and left him “unable to maintain…. continuity [and] a genuine inner world of self” (Sacks, 1998, p. 111). When he approached the female professor/stranger in desperation, she advised him to seek professional help. At her insistence, he entered therapy because “the [dominant] narratives storying [his] experiences” were out-of-synch with his “lived experiences” (White et al., 1990, p. 80). The time was ripe for Kadeem to self-face alongside a skilled professional. How his life experiences had alienated and worn him down needed to be addressed. It was time for him to narratively trace the sources of his sorrow (the arrow) and how his childhood and teen traumas (later compounded by Greater Houston flood) (the bow) had continued to psychologically injure him. Kadeem’s request for help from a stranger created “a crack” in his frozen story to live by. That crack opened up a “possibility [for him] retelling [his] life” (Clandinin et al., 2010, p. 84) in a more psychologically healthy way. Kadeem furthermore needed to expose the stories fixing him for what they were: stereotypes. These stereotypes were not only untrue but also incomplete because the unintended damage invoked years ago was currently given too much play and causing too much pain. Through telling/re-telling his stories to his therapist and having those stories told/re-told to him, he was more confidently able to determine “who [he] was” (Silko, 1997, p. 30) in a more multi-dimensional, self-satisfying way.

Metaphors, narrative, and truth

Not only did Kadeem reclaim his preferred identity through narrative but he also likewise found the truth of his life. This “convincing whole” richly informed his forward-moving story. Further to this, the campus therapist he visited after the flood officially introduced him to the wounded healer archetype, divulging that he also had been wounded and had since helped others nurse their wounds. This spoken metaphor served as “a flash of connection” (Egan, 2017; Edwards, 2018) for Kadeem. Once uttered, it became a vehicle through which he could “re-author [his] conversations” (White et al., 1990) with his counselor and eventually with us. Because we understand how narrative pedagogies work but do not necessarily know the inner dynamics of therapeutic counseling narratives, we surmise that Kadeem’s therapist challenged his client (Kadeem) to reclaim his experiences, while concurrently freeing himself of the victimhood that had weighed him down for decades. In other words, Kadeem learned that he needed to stop accepting the victim plotline. He needed to claim the narrative truth (Spence, 1984) of his life and to recognize that it was more real than the pseudo-narrative truths that others had perpetuated and that he—deleterious to his story to live by—felt forced to live within. Kadeem found that his claiming of “devastating experiences of deep darkness…. did not negate the light that also [was] part of who [he] was” (Palmer, 2018, p. 65). With great clarity, he could see that his “suffering [could] be transformed into something that brings life” (Palmer, 2018, pp. 46–47). Rather than being broken apart by depression, Kadeem’s narrative was “broken open” (Palmer, 2018, p. 49) to the world. This new understanding enabled him to share his story widely and to assist children to benefit from his wounded healer experience where “failure morphed into fulfillment” (Palmer, 2018, p. 35).

Arrogant perception, loving acceptance, and identity

A fifth prominent narrative thread is intermingled in Kadeem’s wounded healer story: his movement from arrogantly perceiving his Nigerian parents and their Christian faith to his loving acceptance of them and the religious views they held and expressed (Lugones, 1990). Readers will recall that Kadeem initially trivialized and then riled against his parents’ faith. In fact, he privileged science over religion in his first interview. However, when the research study ended, Kadeem had learned a great deal more about being a scientist and how discarding religious belief without holding religion open to inquiry would not be something a scientist would do. He knew that the final score on the religion–science debate probably would never be reached. He had come to know that “science grows out of its past but never outgrows it, any more than [young adults] can outgrow their childhoods” (Sacks, 2019, p. 39).

Closing statement

Kadeem Bello, a computer science student who received an NSF-sponsored scholarship, ended his story by declaring himself a wounded healer and an ambassador of hope. Kadeem’s personal identification with Jung’s archetypal metaphor enabled us to sift the events in his experiential narrative “through the conceptual lens proposed by the person utter[ing] it” (Hanne, 2015, p. 24). Our resultant work forged new connections between narrative and metaphor and underscored the importance of opening up stories (Greene, 1995) as a way to strengthen wellbeing. More specifically, Kadeem Bello’s hope story demonstrates how “narrative agency can challenge the impact of trauma on…identity” (Lucas, 2016, p. 23), which, with time and attention, gives narrative cohesion to a past–present–future that previously was stuck and unable to be dislodged. This allowed Kadeem to subsume new identity threads and to consider new future possibilities. All this was accomplished through unpacking two seemingly contradictory ideas (wounded + healer) and animating how the metaphor “disturb[ed] a whole network of meaning [through] aberrant attribution” (Ricoeur, 2003, p. 23). The wounded healer metaphor further proved to be the “gloved hand that touch[ed] lightly but true” (Lane, 1988, p. 6) on Kadeem’s experiential continuum. Our following of his chosen story caused us to revisit his narrative through the metaphoric lens of the wounded healer, which surprisingly managed to “heal and transform” him (Greene, 1995, p. 17) and awaken us to the import of his narrative not only for him, but for us and others globally reading and learning from it. Most importantly, Kadeem’s scholarship not only prepared him to be a STEM professional earning an above-average wage, but taught him the inordinately important life lesson that “you are the only custodian of your integrity and the assumptions made by those who misunderstand who you are and what you stand for reveals a great deal more about them and absolutely nothing about you” (Popova, 2013).

Because of his more keenly refined understanding of his Nigerian/American cultural practices and his awareness of social interactions that previously wounded him, Kadeem Bello was able to confidently continue his life with a deep sense of hope, knowing he had laid past insecurities to rest, and that his story of overcoming odds that would have incapacitated others, could now stand as a national and international model that others—particularly other African, African–American, and African immigrant youth—can emulate in the future.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of the research participant. The digital narrative inquiry that conveys key themes can be retrieved at https://youtu.be/_ca_LYIwW94.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by an Institutional Review Board. The participant consented to participate in this study. The participant was given the option to withdraw participation at any time.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This article was supported by the National Science Foundation Grants: DUE 1356705 and DGE 1433817.

Conflict of interest

RV is the founder of Everest Security and Analytics, Inc.

The remaining authors declare that they have made contributions in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers.

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009). The danger of a single story’ TED global talk. Available Online at: https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story [accessed June 30, 2022].

Anzaldua, G. (1987/1999). Borderlands la Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books.

Arendt, H. (1998). The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226924571.001.0001

Arkhipenka, V., and Lupasco, S. (2019). “Narrative and metaphor as two sides of the same coin: The case for using both in research and teacher development,” in Narrative and metaphor in education: Look both ways, eds M. Hanne and H. Kaal (New York, NY: Routledge), 221–232. doi: 10.4324/9780429459191-16

Baboulene, D., Golding, A., Moenandar, S.-J., and Van Renssen, F. (2019). “You in motion: Stories and metaphors of becoming in narrative learning environments,” in Narrative and metaphor in education: Look both ways, eds M. Hann and A. Kaal (New York, NY: Routledge), 32–45. doi: 10.4324/9780429459191-3

Beijaard, D., Meijer, P. C., and Overlook, N. (2004). Reconsidering research on teachers’ professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 20, 107–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2003.07.001

Clandinin, D. J., and Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Publishing.

Clandinin, D. J., and Huber, J. (2010). “Narrative inquiry,” in International encyclopaedia of education, 3rd Edn, eds P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw (New York, NY: Elsevier), 436–441. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01387-7

Clandinin, D. J., Downey, C. A., and Huber, J. (2009). Attending to changing landscapes: Shaping the interwoven identities of teachers and teacher educators. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 37, 141–154. doi: 10.1080/13598660902806316

Clandinin, D. J., Huber, J., Huber, M., Murphy, M. S., Orr, A. M., Pearce, M., et al. (2006). Composing diverse identities: Narrative inquiries into the interwoven lives of children and teachers. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203012468

Clandinin, D. J., Murphy, M. S., Huber, J., and Murray Orr, A. (2010). Negotiating narrative inquiry: Living in a tension-filled midst. J. Educ. Res. 103, 81–90. doi: 10.1080/00220670903323404

Conle, C. (1999). Why narrative Which narrative Struggling with time and place in life and research. Curric. Inq. 29, 7–32. doi: 10.1111/0362-6784.00111

Connelly, F. M., and Clandinin, D. J. (2005). “Narrative inquiry,” in Complementary methods for research in education, 3rd Edn, eds J. Green, G. Camilli, and P. Elmore (Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association), 477–488.

Craig, C. J. (2001). The relationships between and among teachers’ narrative knowledge, communities of knowing, and school reform: A case of “The Monkey’s Paw”. Curric. Inq. 31, 303–331. doi: 10.1111/0362-6784.00199

Craig, C. J. (2017). “Sustaining teachers: Attending to the best-loved self in teacher education and beyond,” in Quality of teacher education and learning, eds X. Zhu, A. L. Goodwin, and H. Zhang (Singapore: Springer), 193–205.

Craig, C. J. (2020). Curriculum making, reciprocal learning, and the best-loved self. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Egan, K. (2017). “Discovering the oral world and its disruption by literacy,” in Proceedings of the look both ways: Narrative & metaphor in education, conference, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University). doi: 10.4324/9780429459191-2

Elbaz-Luwisch, F. (2006). “Studying teachers’ lives and experiences: Narrative inquiry in K-12 teaching,” in Handbook of narrative inquiry, ed. D. J. Clandinin (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 357–382. doi: 10.4135/9781452226552.n14

Frank, A. (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness and ethics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. doi: 10.7208/chicago/9780226260037.001.0001

Frith Luton (2019). Jungian dream analysis and psychotherapy. Available Online at: https://frithluton.com/articles/wounded-healer/ [accessed June 30, 2022].

Gill, S. (2014). “Mapping the field of critical narrative,” in Critical narrative as pedagogy, eds I. Goodson and S. Gill (New York, NY: Bloomsbury), 13–37.

Goodson, I. (2013). Developing narrative theory: Life histories and personal representation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Goodson, I., and Gill, S. (2011). “Learning and narrative pedagogy,” in Narrative pedagogy, eds I. Goodson and S. Gill (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 113–136.

Goulah, J. (2015). Cultivating chrysanthemums: Tsunesaburo makiguchi on attitudes toward education. School. Stud. Educ. 12, 252–260. doi: 10.1086/683218

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hanne, M. (2015). “An introduction to the ‘Warring with words’ conference,” in Warring with words, eds M. Hanne, W. D. Crano, and J. S. Mio (New York, NY: Psychology Press), 1–15. doi: 10.4324/9781315776019

Hekman, S. (2000). Beyond identity: Feminism, identity and identity politics. Femi. Theory 1, 289–308. doi: 10.1177/14647000022229245

Holdren, J. P., and Lander, E. (2012). Engage to excel: Producing one million additional college graduates with degrees in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Report to the president. Washington, DC: President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

Kerenyi, C. (1959). Asklepios: Archetypal image of the physician’s existence. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lane, B. (1988). Landscapes of the sacred: Geography and narrative in American spirituality. New York, NY: Paulist Press.

Lee, H., Rios, A., Li, J., and Craig, C. J. (2018). Becoming a Wounded Healer. Available Online at: https://youtu.be/_ca_LYIwW94 [accessed June 30, 2022].

Lindemann Nelson, H. (2001). Damaged identities: Narrative repair. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lucas, S. (2016). The primacy of narrative agency: A feminist theory of the self. Doctoral dissertation. Sydney: University of Sydney.

Lugones, M. (1990). “Playfulness, “world”-travelling, and loving perception,” in Making face, making soul: Creative and critical perspectives by feminists of colour, ed. G. Anzaldua (San Francisco, CA: Aunt Lute Books), 390–402.

Nash, R. (2004). Liberating scholarly writing: The power of personal narrative. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Palmer, P. (2018). On the brink of everything: Grace, gravity and getting old. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Penwarden, S. (2019). “Weaving threads into a basket: Facilitating counsellor identity creation through metaphors and narratives,” in Narrative and metaphor in education: Look both ways, eds M. Hanne and H. Kaal (New York, NY: Routledge), 249–262. doi: 10.4324/9780429459191-18

Phelan, A. (2009). “A new thing in an old world Instrumentalism, teacher education and responsibility,” in Engaging in conversation about ideas in teacher education, eds F. J. Benson and C. Riches (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 105–114.

Popova, M. (2013). Happy birthday, brain pickings: 7 things I learned in 7 years of reading, writing, and living. Available Online at: https://www.themarginalian.org/2013/10/23/7-lessons-from-7-years/ [accessed June 30, 2020].

Ricoeur, P. (2003). The rule of metaphor: The creation of meaning in language. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Ritchie, L. (2010). ‘Everybody goes down’: Metaphors, stories and simulations in conversations. Mean. Symb. 25, 123–143. doi: 10.1080/10926488.2010.489383

Sacks, O. (1998). The man who mistook his wife for a hat: And other clinical tales. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Sacks, O. (2019). Everything in its place: First loves and last tales. New York, NY: Knope Doubleday Publishing Group.

Schwab, J. (1960/1978). “What do scientists do,” in Science, curriculum and liberal education: Selected essays, eds I. Westbury and N. Wilkof (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press), 184–228.

Schwab, J. J. (1954). Eros and education: A discussion of one aspect of discussion. J. Gen. Educ. 8, 51–71.

Silko, L. M. (1997). Yellow woman and a beauty of the spirit: Essays on native American life today. New York, NY: Touchstone.

Spence, D. (1984). Narrative truth and theoretical truth. Psychoanalytic 51, 43–69. doi: 10.1080/21674086.1982.11926984

Stone, E. (1988). Black sheep and kissing cousins: How our family stories shape us. New York, NY: Transaction Publishers.

Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of the modern identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

White, M., White, M. K., Wijaya, M., and Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. New York, NY: WW Norton & Company.

Keywords: higher education, scholarships, STEM, learning, teaching, narrative, metaphor, identity

Citation: Craig CJ, Li J, Rios A, Lee H and Verma RM (2022) Wounded healer: The impact of a grant-supported scholarship on an underrepresented science, technology, engineering, and mathematics student’s career and life. Front. Educ. 7:1043518. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1043518

Received: 13 September 2022; Accepted: 05 October 2022;

Published: 10 November 2022.

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Celina Lay, Brigham Young University, United StatesMary Frances Rice, University of New Mexico, United States

Copyright © 2022 Craig, Li, Rios, Lee and Verma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: HyeSeung Lee, ZWR1bGhzZWR1QHRhbXUuZWR1; ZWR1bGhzZWR1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Cheryl J. Craig

Cheryl J. Craig Jing Li2

Jing Li2 Ambyr Rios

Ambyr Rios HyeSeung Lee

HyeSeung Lee