- 1Department of Education, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, Ireland

- 2Institute of Education, University of Derby, Derby, United Kingdom

- 3Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, Ireland

Seventeen Practitioner Researchers (PRs) were engaged as co-researchers in an evaluation commissioned by Ireland’s Department of Childhood, Equality, Disability, Integration, and Youth (DCEDIY), as an innovative aspect in methodological design. The evaluation investigated the implementation and impact of Ireland’s award winning policy for the inclusion of children with disabilities in mainstream pre-schools, the Access and Inclusion Model (AIM). As co-researchers in the project, the PRs constructed case studies of pre-schools, and children who were being supported by AIM. In this context, this paper draws on feminist theory to present the rationale for involving PRs as co-researchers in evaluations of high profile national programs like AIM. It also applies thematic analysis to a critical reflection written by one co-researcher (who is also the lead author), in which she writes about her gendered experience of being a PR. Thematic Analysis (TA) is applied to this critical reflection to explore the way in which the PR role may have impacted on her professional identity and agency. Three themes were constructed from the TA which included expertise as a resource for advocacy, personal and professional development, and continual learning and inclusive practice. The findings were interpreted through a feminist lens, and cast light on the way that the PR frames professional potency within more feminine constructions of power related to care, nurture, collaboration, nurturing and enabling. They also demonstrate how, in this particular case, the PR role had a transformative impact on expert identity, and enriched capitals for empowering others. The paper ends with a call for more participative approaches to the evaluation of national policies through the engagement of practitioners as researchers. It is argued that this would result in evaluations that were more attuned to the vernacular of practice, and hence more impactful. It also offers opportunities for professional development whilst symbolizing the validation of practitioner expertise by policy makers in a feminized sector where, low pay and low status have long been issues of concern.

Foreword

Ireland’s history of investing in early childhood education is inextricably linked to specific political, cultural, and socio-economic contexts, associated with the birth of the new state in 1922. These unique contexts have shaped the development of the system, we are all familiar with today (Ring, 2022). From 1831, at the establishment of the national school system, children from 2 years of age were enrolled in infant classes. In 1884 the age of enrolment increased to three and remained so until 1934 (O’Connor, 1952). The impact of prevailing doctrinal cultural and ideologies related to the place of children, women and families in Irish society that prevailed during the early years of the new state were further consolidated in the Irish Constitution of 1937 (Ireland, 1937, 2018). Increasingly as the new state forged its own identity, global movements underlining the crucial role of high-quality inclusive early learning and care (ELC) for children’s learning and development began to influence Irish policy development (Ring, 2022). Parallel to the process of modernization and reform, allied with growing economic prosperity and an increasingly female workforce, realizing the vision for a universal system of quality inclusive ELC for all children became an imperative. This imperative would begin to be finally realized in 2010 with the introduction of the free early childhood care and education (ECCE) scheme, its subsequent extension in 2016, and advent of the Better Start Access and Inclusion model (AIM) in 2016 (Ring and O’Sullivan, 2019). As research continues to confirm the incontestable link between children’s high-quality inclusive ELC experiences and the ELC practitioners’ knowledge (s), practices and values (Urban et al., 2012, 2017; Ring et al., 2019a), the role of the ELC practitioner becomes pivotal. It is timely therefore as we celebrate a hundred years of independence that the policy lens becomes clearly focused on the ELC practitioner. Engaging practitioners as co-researchers in building a high-quality inclusive ELC system provides a real opportunity to create meaningful and responsive policy, while simultaneously disrupting the hegemony of the existing order through resisting patriarchal constructions of ‘expertise’. Placing the ELC practitioner as co-researcher in the ELC policy and practice ecosystem propels the professionalization of the ELC practitioner to the apex of the policy agenda (Ring et al., 2019b). As a core element of a progressive society, ELC policy makers, and indeed education policy makers more broadly have much to learn from “The case of the end of year three evaluation of the Access and Inclusion Model.”

Introduction

This paper focusses on the involvement of practitioners as co-researchers in the evaluation of national policies. It applies feminist theory to argue that the involvement of Early Learning and Care (ELC) practitioners in this type of high-profile activity, offers opportunities for professional development and identity shift in a workforce that is largely female.

These arguments are explored in the context of the end of year three evaluation of Ireland’s Access and Inclusion Model (AIM). This evaluation was commissioned by the Department of Childhood, Equality, Disability, Integration, and Youth (DCEDIY) and its purpose was to investigate AIM’s effectiveness in ensuring the full inclusion and meaningful participation of children with disabilities in the Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) program.

Its methodological approach included the appointment of 17 Practitioner Researchers (PRs) as co-researchers who were recruited with the support of Early Childhood Ireland (ECI) to work with the wider research team on the evaluation of AIM. PRs were introduced to research methods for constructing case studies of individual pre-schools and children. The research methods included a multi-modal mapping method to use with children who were supported by AIM. The purpose of this method was to elicit (and validate) children’s voices, specifically their subjective experiences of inclusion and participation within their pre-schools. In the end of year three evaluation of AIM, the methodological design sought to include children’s perspectives on their own inclusion and include PRs as co-researchers as an expression of congruence with the principles of inclusive practice, and its democratic and pluralist values. The DCEDIY were supportive of the engagement of PRs in the evaluation, and of the methods used to elicit children’s experiences, since elevations in the status of the ELC workforce, and a commitment to children’s right to be heard, is central to Ireland’s policy intentions and aspirations for the sector.

In this inclusive milieu, this paper focusses on the rationales for engaging PRs, and the experiences of one PR specifically, so that the potential of such approaches can be better understood. The questions pursued in the paper are as follows:

• In the context of ELC, what rationales apply to the involvement of practitioners as co-researchers in evaluations of national programs like AIM?

• What are the potential impacts of involving practitioners as co-researchers in these contexts, as derived from the gendered experiences of one PR?

To initiate exploration of the first question listed above, this paper begins with a brief explanation of the end-of-three-year evaluation of AIM, and its purposes and methodological approach to engaging PRs. Then, the rationale for involving PRs as co-researchers is considered with reference to feminist theories in order to critique traditional patriarchal models of knowledge generation and their command-and-follow orientation (Sisson and Iverson, 2014). The paper applies a feminist lens to the concept of ‘counter hegemony’ which is a process that self-consciously opposes the hegemony of an existing order (Weiler, 1988), which in this case refers to the gendered oppression of the ELC workforce.

To explore the second question, we consider the potential impact of co-researching on identity, agency, knowledge, and practice by presenting one PR’s critical reflections on her gendered experience of being a co-researcher in the evaluation of AIM. The PR narrates her subjective experiences to explore how a) shifts toward an ‘expert’ identity and professional agency, were catalysed by being engaged as a co-researcher within the AIM evaluation research community, and b) knowledge and implementation of the research tools had implications for her own professional practices, perceptions and decision making. The PRs critical reflection forms the data for a thematic analysis which is interpreted through a feminist lens.

The paper concludes with an account of the implications for policy makers and the practitioner community.

Context: The end of year three evaluation of aim

The following provides the context for the co-researching role of PRs in the evaluation of AIM and serves simply as an overview such that the counter hegemonic function of this methodological approach, and its broader impacts can be understood within its specific context. Fuller accounts of methods and findings are reported in DCEDIY publications about the AIM evaluation.

The evaluation of AIM was commissioned by the DCEDIY who posed the following research questions for investigation:

Is AIM effective and achieving intended outcomes of enabling the meaningful participation and full inclusion of children with disabilities?

Has AIM influenced practice, or capacity in the workforce for inclusive practice?

Is the current approach appropriate in the national context?

Can AIM be enhanced, and/or scaled up or out to other age groups and types of additional need?

As can be discerned from the list above, the AIM evaluation questions were focused on the implementation and impact of the policy, and whether it should be expanded. This was in the context of the First 5 strategy for babies, young children, and their families (Government of Ireland, 2018a). AIM is regarded as a central pillar to strategic action 8.3 of the First 5 Implementation Plan 2019–21 (Government of Ireland, 2018b) which seeks to:

Ensure that ELC provision promotes participation, strengthens social inclusion, and embraces diversity through the integration of additional supports and services for children and families with additional needs (Government of Ireland, 2018a, p. 95).

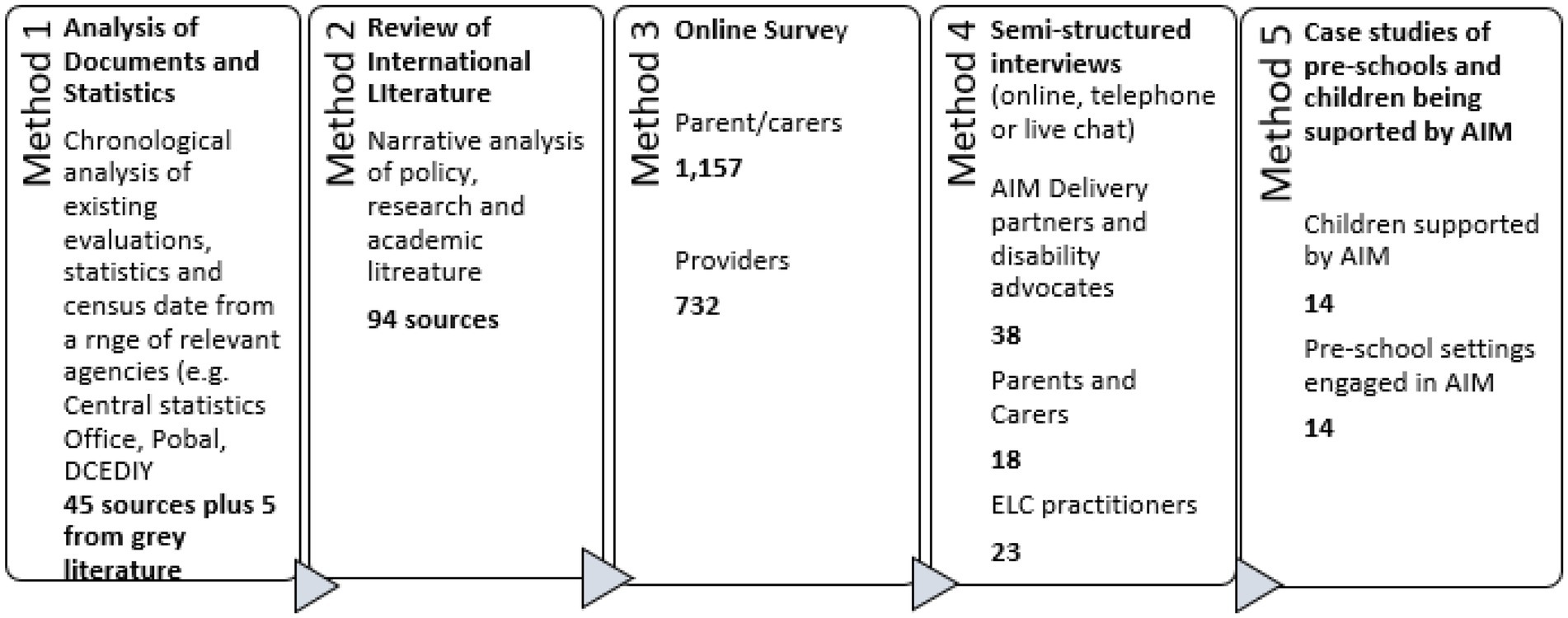

The evaluation of AIM was implemented by the University of Derby Research Consortium, which comprised of researchers from the University of Derby, IFF Research, and Mary Immaculate College (MIC). Mixed methods were deployed to the investigation of the research questions, which included reviews of documents and international literature, large scale surveys, multimodal interviews, and case studies. The research design is summarized in Figure 1.

The PRs were deployed to Method 5 – the case studies of pre-schools and children being supported by AIM. Seventeen Practitioner Researchers were appointed through an open, formal application process supported by Early Childhood Ireland and criteria for selection included a DCEDIY approved Level 8 qualification in Early Childhood Education as a minimum, the Leadership for Inclusion in the early years (LINC) special purpose award, and knowledge of the AIM model. To prepare for the role, PRs engaged in a research skills development program led by researchers at MIC and the University of Derby, which focused on ethics, instrumentation, data collection methods and interpretation. This began early in the project timeline, so that the program could be influenced by emergent findings, and the methods piloted and developed in collaboration with PRs. In most cases, PRs completed a case study of a single pre-school, which included a multi-modal conversation with a child supported by AIM attending that pre-school. Data collection focused on the pre-schools’ implementation of inclusion in the context of AIM. A variety of research methods were deployed, including interviews, spontaneous encounters, observations of practice, observations of the environment, and analysis of documents within the settings. For the multi-modal conversations with children, PRs implemented a method, which involved several stages of elicitation, including family led introductions to making maps about the people and places in their lives, and the creation of a map about the pre-school by the child; the children’s book, ‘My Map Book’ by Sara Fanelli supported this. Further stages of the multi-modal conversations took place at the child’s pre-school and involved a walking tour involving the child, the family and the PR. PRs referred to the child’s map as a stimulus for the tour and took photographs of the places and things that children pointed out. Finally, the PR, child and family would engage in a focused conversation using the map and the photographs, so that the child could narrate their experiences of full inclusion and meaningful participation. The mapping approach was a way of linking young children’s experiences (in this case of inclusion and participation) to the contexts where they occur (Gowers, 2022a). Its method was informed by social semiotic theory (Bezemer and Kress, 2010; Halliday, 2014) to recognize the multimodality in contemporary communicative practices, and the need to provide forums for elicitation that might enable young, disabled children to express their lived experiences of the abstract notions of inclusion and participation. Multimodal texts may combine image, sound, gesture, movement, animation, and written language (Jewitt, 2005; Kress and Mavers, 2005).

The pragmatic rationale for engaging PRs

As practice experts in the contexts being investigated, PRs’ ability to notice phenomena of interest to evaluating AIM’s implementation and impact is likely to be more developed than that of a researcher who is more distant from practice. For example, PRs’ ability to understand and interpret the use of resources in the pre-school, specific ELC practices, and interactions between children and others. This level of insight has the potential to result in richer, more fine-grained, and more nuanced data in the vernacular of practice, and readers may consider whether this has been achieved, when accessing the DCEDIYs publications about the evaluation. Our view is that the engagement of PRs enabled high quality evidence of AIM’s operation and impact in context. In the spirit of AIM, this also enabled children’s own accounts of full inclusion and meaningful participation to be reported, and in so doing, recognized children’s status as active citizens whose right to have a say in matters affecting them irrespective of age are ability, is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child 1990 (Murray et al., 2019).

Literature review: The early years workforce and the gender relations of expertise, and the philosophical rationale for engaging PRs

In what follows, the philosophical rationale for engaging PRs as co-researchers in the evaluation of AIM is explored with reference to feminist theory. The discussion uses the term gender to refer to feminine and masculine as socially constructed categories of being, and sex to refer to male and female as biological, physiological categories of being. In adopting a feminist framing, the term gender allows inequalities between men and women to be critiqued so that the assumption of such differences as ‘natural’ is open to contestation and informed action (McNeil, 1998). The term ‘expertise’ refers to specialized forms of knowledge associated with professions, though it is recognized that there are forms of expertise (in care giving, manual activity, and emotional labor for example) that are expounded in private and personal domains.

The intersection of gender and expertise in the labor market has long been a subject of interest in feminist research. For example, Braverman (1998) explored the way in which work, and skills come to be devalued in sectors where women predominate, a process often referred to as ‘feminisation’ (Cullen, 2022). Drawing on studies of the clerical sector in the United States (US), Braverman (1998) theorized a causal relationship between gender and the attribution of ‘expertise’. Where a profession is feminized, expertise is sequestered, where a profession is masculinized, expertise is accorded. In this context, decisions are made about how much a worker should be paid. In the Early Learning and Care (ELC) sector in Ireland, and globally, the ELC workforce is a feminized profession, and has experienced low pay and low status (Osgood, 2006; Sisson and Iverson, 2014). This is a situation the Irish government has been seeking to reverse in pursuit of higher quality provision for young children through the professionalization of the workforce (for example, see descriptions of working with children as a ‘professional role’ in Aistear—National Council for Curriculum Assessment (NCCA), 2009, and Síolta—Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education, CECDE, 2006), but progress has been difficult to secure, in part because of the predominance of private providers in the sector and the limited reach of the state (Hayes et al., 2013).

However, when viewing the matter from a feminist poststructuralist position, gendering discourses can also be implicated in the reproduction of low status for the ELC workforce. As an illustration, Moloney (2015) argues that the ambiguity of the early educator role in Ireland compounds the challenges to an expert identity and status. The ambiguity comes from the dual description of early childhood provision as care and education, such that simplistic conceptualizations of the role (e.g., childcare, or childcare worker) perpetuate to reinforce the assumption that the task can be performed by any lay person, and particularly any lay woman (Lyons, 2011). Caregiving is often associated with innate or ‘natural’ abilities not associated with professional knowledge and expertise (Bolton and Muzio, 2008). Feminist theorists have argued that the tendency to describe women’s skills as ‘natural capacities’ is one method through which expertise is denied (Elson and Pearson, 1981) with particular consequences for the ELC workforce (Osgood, 2006). Such discourses are considered to impose an ideological dimension on expertise, such that ‘skill’ is attributed to certain types of work according to the sex and power of the workers, rather than its actual content. In this way, the ideologies of a patriarchal society are dressed up as objective truths (Phillips and Taylor, 1980) to oppress a largely female workforce. The concept of practitioner-as-researcher has long been associated with the construction of the practitioner as expert because it carries an inherent recognition of a knowledge base, and a profession’s commitment to ongoing development through intellectual, extended training. The process of research enacts a spirit of altruism, personal responsibility, adherence to codes of ethics, and teacher autonomy (Ring et al., 2019b), and is also counter hegemonic in its construction of the practitioner as an expert.

Returning to the inclusion of PRs in the evaluation of AIM, there was an intention to work against these dominating discourses, and position practitioners as experts with specialist knowledge and skills of great value to the development of inclusion in the sector. This was through the expertise-affirming function of research. We commend the DCEDIY for supporting their integration as co-researchers, and for supporting the child-elicitation methods used to gather data. However, there were limitations in the extent to which PRs were co-constructors of the evaluation because of the resources available for paying for their time. For this reason, PRs were not involved in the co-design of research instruments, or in the writing of reports. They were also not involved in the discursive communications between the research team and the commissioning authority. These are matters it will be important to resolve in a context where the AIM evaluation represents a significant step forward.

This paper includes an unabridged critical reflection on the gendered experiences and impacts of co-research in the context of the AIM evaluation. As first author of this paper, she narrates her experiences of the PR role, and reflects on its impacts. Her co-authors have implemented a thematic analysis of the narration, using the narrative text itself as data. The methodological approach used is described below.

Methodology

The first stage was for the PR to write a critical reflection on her experiences. The wider authorial team supported her preparations by conversing with her and listening actively to her accounts of experience and perspective This was further supported by a symposium, where she talked about her experiences with other ELC practitioners, and professional educators. The critical reflection was written freely as an outcome of this process and is presented unedited in order to expound respect for the author’s expertise, and the validity of her perspective. We consider this to be in the counter hegemonic spirit of this paper.

Braun and Clark’s (2012) approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2019) was adopted to explore the lived experience of the PR, and to form a framework for interpretation through the lens of feminist theory. In particular, feminist theories about workforce feminization were applied, In the present study an inductive approach was adopted in the analysis of the critical reflection, because it was important to identify themes which were strongly linked to the data rather than using questions or hypotheses to drive the development of themes. As is traditional within thematic analysis, themes were developed through the iterative formation of codes and categories, and the full research team came together to review the logic and consistency of the analytical process and come to agreement on the themes that were the outcome of the process.

The unedited critical reflection by one PR follows.

Critical reflection on the gendered experiences and impacts of co-research

My journey as an early years Educator began in 2010 when I set up the first inclusive green school in my area. We opened under the guidance of Aistear (the Irish Learning through Play framework for early years), designed an emergent curriculum support structure, began a journey through An Taisces’ Green school program and in 2018 received our formal Siolta Quality Framework Accreditation. Influenced by the Reggio Emilia model of the environment as educator, it has always been very important to me to support the inclusion of children by working through a learning through play model. Prior to opening my preschool service, I began an Advanced Diploma in Inclusive Education with Queen’s University. Over the last twelve years I have witnessed much change within the Irish early years sector particularly around designing for inclusion. During this time, I have worked within the previous Irish model of a Special Needs Assistant (SNA) being assigned to the child prior to starting in preschool, in 2017I trained to become one of the first graduates of the LINC program, introduced the role of Inclusion Coordinator (INCO) within our setting, rolled out the AIM model within my setting (2017 to current), continued on to complete the LINC + continuing professional development (CPD) program for INCOs, and successfully applied for the PR role as part of the end-of-three-year evaluation of AIM.

Throughout all this change and growth in the sector, my professional skill set developed and through experiential learning with the children in an emergent curriculum setting I continue to challenge, discover, explore new and revised ways of advocating for children and their families. Prioritizing a child-centered approach, which focuses on the voice and the rights of the child to support their personal, social, and emotional development (PSED) is of uppermost importance to me.

The past twelve years have been a most rewarding journey of discovery, reflection, reframing and continually challenging my own support of the children in our setting.

Having completed the LINC program in 2017 and the LINC+ CPD for graduates’ program in 2021, I was at a point in my professional career where I was looking for opportunities to enhance my professional knowledge and value to the early years sector more generally. When the community of LINC CPD graduates were given the opportunity to apply for the position of PR, I found my avenue to do so, but also so much more came from this experience than I initially anticipated.

My experience as PR began at a critical time of change within Irish society following COVID19, the early years sector being the frontline for children returning and beginning their journey through preschool. Some of these children had never mixed with children of their own age, and some had experienced trauma through the death of a relative, loss of employment within the house and illness in the home. Children who happily enjoyed their preschool journey were now presenting with anxiety or withdrawing from their friends. In my preschool setting, and in the sector more generally we found ourselves supporting children who were born during and /or have lived through a pandemic, and the effects of this on children’s personal, social, and emotional development are still in the process of being understood. It should be understood that this is not a shared experience, rather early years professionals should reflect on this as a unique experience pertinent to a specific cohort. As a setting we found we needed to journey through this moment in time with the children, learning how best to support them through our experiences with them. Practitioners in my setting and amongst the PRs more generally, found they were and still are directly discovering with the children and their families how to modify supports, introduce new scaffolding techniques, designing with the children new tools to support their personal, social, and emotional development (PSED) in this new world. It is of critical importance in building this community of knowledge within early years that a path exists to use this direct collaboratively gathered research obtained through our shared experiential learning to influence policy making, continue implementation of the AIM model and support First 5’s vision of improving the lives of children and families within Irish society.

Through my work as PR, I acquired knowledge and research tools that I not only added to my own professional practice, perceptions and decision making, but also led me to becoming a systematic observer, deepening my partnership with parents, rediscovering of the power of language, developing my professional knowledge of how to hear children’s voices and leading on inclusion. The following section will pick up on these points in turn.

In the role of PR, I also found that I deepened my skills as a systematic observer (Palaiologou, 2019); this method challenged my professional objectivity and promoted a need for the absence of emotional bias, which stepped me out of my normal educator role so that I could see things anew. My engagement with systematic observation took me to a new place of emersion in the rich narrative of the child’s experiences. As a researcher this direct relationship with the child has deepened my understanding of their “code” (Silverman, 2011), their daily ceremonies and rituals which led to both the gathering of more meaningful quality data, and the forming of much stronger relationships with the children and their families. Having engaged in the process of becoming a PR I have experienced a shift in my own expert identity and professional practice. As an AIM co-researcher, my professional identity, has been elevated through my work as a PR, which has influenced my leadership of the preschool and in turn supported my colleagues with their professional development.

As part of the research gathering for the case study, I discovered the real time effectiveness of capturing evidence directly from children. As a sector, we know the value of primary caregivers sharing their knowledge of their child with the early years educator facilitates effective transitioning between home and preschool (NCCA, 2018; The Government of Ireland, 2018b). Co-researching allowed the inclusion of more meaningful familial participation and also elevating the child to content creator. Co-researching while deepening the child and parents’ involvement in everyday practice also provided an opportunity for familial investment in our emergent curriculum.

As early years professionals, we are often not equipped with the nuanced language needed to articulate our own CPD requirements within the sector. Moreover, it can also be difficult to locate a shared inclusive vernacular understood universally by other children’s services, families and child supporting experts. Reflecting on the language introduced to the PRs through the research skills development programme, I quickly discovered a new vocabulary which aligned with my child-centered values and the embedding of children’s voices in our emergent curriculum. Subsequently, I found that when in discussion with peers, parents, therapists, and other communities of practice this new language brought a deepened meaning to the true value of practitioners’ daily interactions with children in the setting. I am now working to embed this newly discovered language of expertise into our early year’s community so that it is evident in our ethos, culture, and practice. For example, in my preschool we no longer talk about “drawing a picture,” rather we “draw and discuss.” Instead of labelling drawing, painting, story making etc. as merely “mark making” we encourage the children to capture their feelings, capture what they would like to do, explore their thinking on paper, map out their day/interests/needs. Through this approach, our deepened professional language is having a direct impact on the children’s ability to communicate more complex ideas. As part of this work, we have introduced the act and language of planning before daily play activities. This allows the child time and space to explore, discover, investigate, engineer, design, and create. When learning through play using the language of STEAM, this provokes the child to explore more and in so doing, learn more about their own identity within their social setting. We have found that by broadening and deepening children’s communication this approach serves as a form of social inclusion equalizer, supporting the development of children’s critical thinking, deeper sense of personal identity, and group belonging within a social setting.

Through co-researching with the project team, we were introduced to participatory research with children applying a process called multimodal mapping (Gowers, 2022b). The aim of this voice elicitation tool being to capture a child’s interests in a meaningful representation of their voice (Children’s Rights Alliance, 2011). The use of multimodal approaches facilitated our elicitation of all children’s voices, including those who were non-verbal and had no/limited social interaction with their peers. Through the gathering of photos, videos, mapping, and audio files children shared with us what they like to do on a daily basis. The final “map” PRs created took a full account of the child’s day, embedding their voice and right to actively participate in decision making that affects them.

Following on from this case study model learning, I began working with a family and a child who would enter preschool in Sept 2022 with additional learning support requirements and at the time presented with delayed speech. We reviewed our Home to Preschool Transition model with him in mind and reflecting on the inclusive nature of AIM as a model of practice in a post pandemic environment. Now through a researcher practitioner lens I was challenging how inclusive our model was. Children were physically at the centre of our model. The child came for pre-visits, we worked with parents on a managed approach to starting until they were fully settled in their new environment, a child record full of family information was documented and kept on file.

Following this program of research skill development coupled with the COVID-19 restrictions that the child could not enter the building with his parents prior to starting I engaged with the parents to create a multimodal learning story of the life of their child in the home and mirrored these activities in the preschool setting. This was the first direct implementation of my new PR learning in improving daily practice and our transitions process was redesigned within a number of weeks. While focusing on improving the experience of the child through more meaningful participation in this major transition we actively and effectively introduced sustainable change through a more inclusive home to transition model in direct collaboration with the child and their parents.

What I was not expecting from this experience was the importance of having my professional voice heard, listened to and its value acknowledged. Acting as a co-researcher on this project delivered all of that and more. The importance of having my professional interests represented in this project as a research practitioner supported a meaningful participation in my daily work activities and has also provided a pathway for my professional development as an influencing role on the professional identity of the early years sector.

Following on from my involvement as PR and the transformation of our internal Home to preschool Transitions program, I continued on this process of evidence-based practice. I rolled out a six-month DCEDIY funded program of the Child’s exploration and discovery of the value of their voice in every day decision making. This was completely transformational and part of a much larger program of research I am currently documenting on the child’s own understanding of the importance of their voice in every day decision making.

In September 2022 I will be co-leading a transitions project within a voluntary community of practice group focusing on increasing the positive experience within the lives of children and their families throughout the transitional stages of the child. I will also take on a mentoring role within the early years degree program for students, and an assistant tutor role supporting LINC Graduates within the Irish early years sector.

By inviting families and children to engage in research gathering on this project I witnessed an elevation of the depth of value accorded to their contributions. As research practitioners not only can we as a sector influence change through collaboration and partnership with parents we can also provide evidence to families regarding how their input has influenced change. Supporting an emergent curriculum through a learning through play framework fully supported my role of research practitioner as the child is at the centre of their decision making and as a direct contact to that child, we capture research every day from the source. This discovery of my role as PR awakened the true value of meaningful participation when supporting young children in our settings. While working as an advocate of agency of the child I have also advocated for the voice of the PR and in so doing provided opportunities not only for the child to become the content maker but also discovered collaborative pathways for family members and practitioners to create more meaningful participation through content making in support of process evaluation and transformational practice process introduction or renewal.

In this newfound agency while continuing to advocate for children and my own professional identity I have also discovered a voice of advocacy for the early years practitioner researcher. At a sectoral level this also lays the groundwork for true professional identity of the sector. For the first time in my professional career, I am on a pathway to influencing real change for the quality of support for children and families in early years and beyond.

Through the capture of real time evidence from children, practitioners can introduce time and space for children to have more meaningful experience in everyday activities. By working as PRs, we have an opportunity to embed First 5 policy visions within the culture of early years through research gathered from experiential learning. How transformative that will be.

Findings

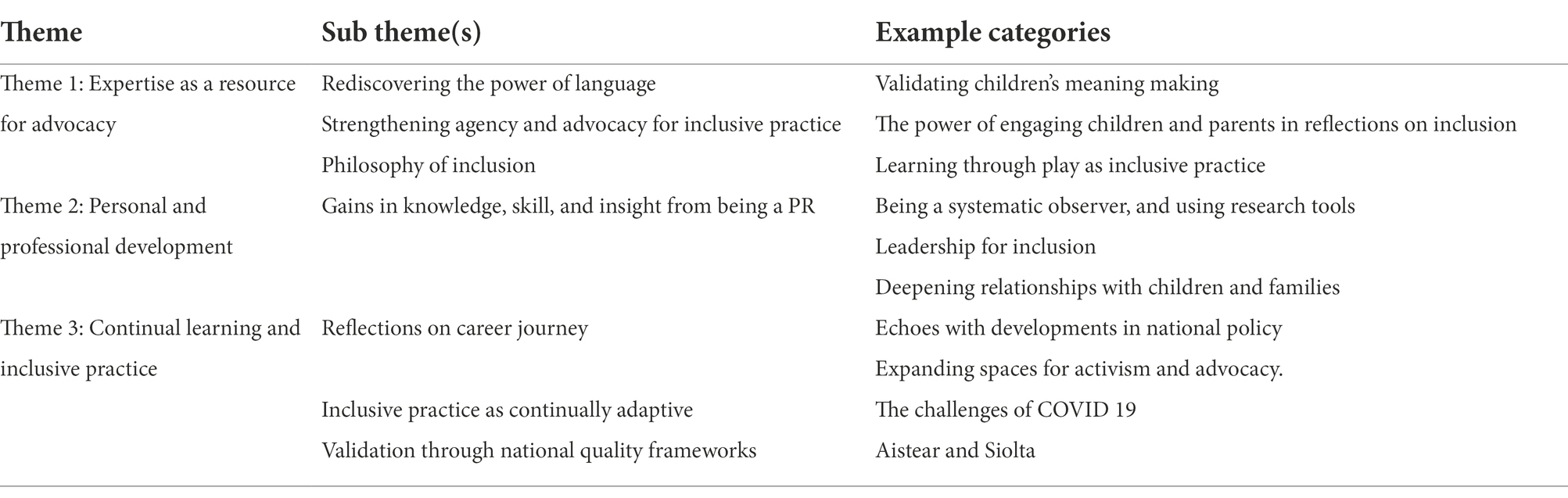

The thematic analysis of the critical reflection above, led to the formation of three major themes as follows:

• Expertise and advocacy for others

• Personal and professional development

• Continual learning and inclusive practice

Table 1 provides a summary of the results of the thematic analysis.

Theme 1: Expertise as a resource for advocacy

The first theme, expertise as a resource for advocacy includes accounts of the PRs experiences of agency as this relates to her own advocacy work. When reflecting on her role as a PR, she notes that ‘much more came from this experience than I initially anticipated.’ An unanticipated gain was new awareness of the importance of being affirmed and valued as a professional:

‘What I was not expecting from this experience was the importance of having my professional voice heard, listened to and its value acknowledged. Acting as a co-researcher on this project delivered all of that and more’.

The PR observes a relationship between her experience of being heard and valued, and finding new ways to advocate for others:

The importance of having my professional interests represented in this project as a research practitioner supported a meaningful participation in my daily work activities and has also provided a pathway for my professional development as an influencing role on the professional identity of the early years sector.

In the above, and in the critical reflection more broadly, there are accounts of how professional qualifications and projects have increased her capacity to advocate for others – the PR role was part of this journey. She also explains that being a PR had given her a new expert language for talking about day-to-day interactions with children in her setting. These practices were intended to validate children’s voice, and elevate their status as meaning makers:

I found that when in discussion with peers, parents, therapists, and other communities of practice this new language brought a deepened meaning to the true value of practitioners’ daily interactions with children in the setting. I am now working to embed this newly discovered language of expertise into our early year’s community so that it is evident in our ethos, culture, and practice.

In the extract above, we observe the PR’s perspective on the relationship between an expert language and the validation of caring practices focused on listening to children. In this way, an expert language frames these actions as expert practices. This in turn, elevates children’s voices, and their status as meaning creators.

The theme also contains data that illustrates how the PR role was one step in a journey of professional development that was congruent with her values, and how this journey had strengthened her capacity to enact them. Her values include a belief in learning through play as a foundation for inclusive practice, finding ‘new and revised ways of advocating for children and their families’, and engaging in continuous learning and reflection. In her conclusion, the PR describes the expansion of her capitals for agency:

In this newfound agency while continuing to advocate for children and my own professional identity I have also discovered a voice of advocacy for the early years practitioner researcher. At a sectoral level this also lays the groundwork for true professional identity of the sector. For the first time in my professional career, I am on a pathway to influencing real change for the quality of support for children and families in early years and beyond.

In summary, the PRs experience includes a positive shift in her expert identity, and her expertise. These are catalyzed by the development of a new language which she deploys to achieve power sharing and advocacy in her local context. In her view, expertise and expert status are resources to be used for sharing power with others, rather than for claiming personal status or authority. She also perceives a relationship between an expert identity for practitioners in the ELC sector, and improved capacities for bringing about the kind of transformative change needed for inclusion. Where an expert status is affirmed, it can catalyze engagement in problem solving and innovation at the local level, and where practitioners are involved as expert change agents and influencers at the sector level, this transformative power is boosted.

Theme 2: Personal and professional development

The second theme, personal and professional development captures the PRs experiences of gaining new knowledge and perceptions as a consequence of the PR professional development program, and the co-research process. The PR notes the importance of becoming more skilled in systematic observation as a consequence of engaging in the AIM research:

My engagement with systematic observation took me to a new place of emersion in the rich narrative of the child’s experiences.

The mapping method used to elicit children’s experiences of inclusion and participation inspired the use of similar multimodal methods in her own setting:

This was the first direct implementation of my new PR learning in improving daily practice and our transitions process was redesigned within a number of weeks. While focusing on improving the experience of the child through more meaningful participation in this major transition we actively and effectively introduced sustainable change through a more inclusive home to transition model in direct collaboration with the child and their parents.

The above extract illustrates how the PR deployed research methods as a way of seeing a child’s experiences anew, and using the insights gained to build more inclusive practices. This PR explains how her experiences as a co-researcher inspired new approaches to familial participation in her own setting, whilst elevating the status of the child as a meaning maker:

As a sector, we know the value of primary caregivers sharing their knowledge of their child with the early years educator facilitates effective transitioning between home and preschool (NCCA, 2018; First 5, 2019). Co-researching allowed the inclusion of more meaningful familial participation and also elevating the child to content creator. Co-researching while deepening the child and parents involvement in everyday practice also provided an opportunity for familial investment in our emergent curriculum.

In summary, this theme captures the PRs experience of learning new ways to use data gathering as a route to collaborating with parents and children in the construction of more inclusive practices centered on listening.

Theme 3: Continual learning and inclusive practice

When observing the data in this theme, it becomes clear that the PR role was one part of a sustained journey of continual learning and reflection focused on inclusion. The PR saw an opportunity for extending her agency, in ways that were useful to the sector:

I was at a point in my professional career where I was looking for opportunities to enhance my professional knowledge and value to the early years sector more generally.

For the PR, continual learning and reflection are essential to the building of inclusive practice:

Throughout all this change and growth in the sector, my professional skill set developed and through experiential learning with the children in an emergent curriculum setting I continue to challenge, discover, explore new and revised ways of advocating for children and their families.

The extract above is an example of her sustained commitment to professional reflection, and she views this as essential to practitioners and their responsibility for innovating practice in response to children’s needs. In her view, COVID 19 was an illustration of the importance of continual innovation:

In my preschool setting, and in the sector more generally we found ourselves supporting children who were born during and/or have lived through a pandemic, and the effects of this on children’s personal, social, and emotional development are still in the process of being understood. It should be understood that this is not a shared experience, rather early years professionals should reflect on this as a unique experience pertinent to a specific cohort. As a setting we found we needed to journey through this moment in time with the children, learning how best to support them through our experiences with them.

As demonstrated in the extract above, the PR believes that the purpose of professional learning is to inspire new ways of keeping children at the center of practice. In her view, this is best achieved by being continually observant and responsive. She positions the processes of ‘discovery, reflection, reframing and continually challenging’ as central to the achievement of more inclusive practice.

In summary, this theme captures the PRs commitment to continual learning, and her belief in the relationship between resolute reflective practice, and positive outcomes for children.

Discussion

The first question posed by this paper focused on how feminist rationales might apply to the involvement of practitioners as co-researchers in evaluations of national programs like AIM. The second was to understand the potential impacts of involving practitioners as co-researchers in these contexts, as derived from the gendered experiences of one PR.

In response to the first question, we note the PRs beliefs about the relationship between growth in an expert professional identity, and her capacities for sharing power. Rather than perceiving the status of the ‘expert’ as a resource for strengthening her personal authority or rank, the PR sees it as a resource for advocacy in pursuit of full inclusion and meaningful participation. Beard (2017) takes a feminist stance on power and being powerful that can help us to understand the PRs gendered perspective on what an expert status should achieve. Noting that history has led us to a point where there is no template for female power other than one that looks rather masculine (modelled on dispositions like competitiveness, objectivity, toughness, and ruthlessness), Beard (2017) proposes a new, feminine framing for what it means to be powerful. Here, power is not conceived as elitist or owned. Instead, it is expressed through the dispositions that women are raised to enact – kindness, care, nurture, collaboration, empathy, listening, enabling. This is not to say that only women enact such dispositions (since men working in ELC contexts are likely to enact the same), or that masculine dispositions are not of value in workplaces, but to emphasize how such dispositions may dominate contemporary constructions of what it means to be professionally potent. The PRs position on power resonates with Beard’s claim that ‘power is a verb and not a possessive noun’ (Beard, 2017, p.40) since it emphasizes enablement over control. It also offers us an alternative view of what expertise is for. In terms of the rationale for engaging ELC practitioners as co-researchers in evaluations of national policies and programs, we can observe a method for reframing professional potency in feminine terms.

As Cullen (2022) and Braverman (1974) have demonstrated, the process of ‘feminisation’ leads to the devaluing of skills, and the retraction of expert status from workforces that are largely female. At the same time, the historical construction of ‘caring’ as a domestic labor has led to its disavowal as specialized skill or expertise (Lyons, 2011). This has repercussions for a workforce centered on the care and education of young children, since along with being feminized, the labors of the workforce are also considered to be do-able by non-professionals. The experience of being a PR seemed to have validated the expert status of day-to-day professional action focused on advocacy. The rationale for including practitioners as co-researchers appears to be validated since it had strengthened the PRs expert identity and her agency as a practitioner. It had also engendered an expert language which in turn had catalyzed practices focused on advocacy, which in turn are deployed to the construction of inclusion for children.

We now consider the second research question posed by this paper. This focusses on the impact of the PR role on professional expertise and efficacy. The PRs critical reflection also points to the significance of ongoing professional becoming, as opposed to professionalism as a static entity. Although the PR had engaged in a range of extensive and high-quality continuing professional development prior to becoming a PR, it is important to recognize the transformation that took place in this role. It seems to have initiated a detachment from the comfort of her ‘average-everydayness’ (Heidegger et al., 2007) causing the PR to suspend assumptions and gaze anew at the phenomena in question. From a position of openness to change, the PR has uncovered a wide range of varied professional possibilities that point to new horizons and a significant leadership contribution to the Irish early years sector.

The PRs’ professional knowledge, practices, and values (Urban et al., 2012), were instrumental in mobilizing a highly effective methodology for capturing the voices of children, families, and professionals. As the PR’s critical reflection illustrates, participation in the evaluation also supported knowledge utilization (Buyse and Wesley, 2006) as PRs adopted project tools in their daily practice. This demonstrates the power of collaborative research to influence practice, more directly. It is particularly interesting to note the nexus forming between the professional language development of the lead author, the children’s own deepening and broadening communication and social inclusion, and the strengthening of family partnership work. Whilst choosing the right language can sometimes seem little more than semantic fashion or a professional challenge to keep up to date with (Codina and Wharton, 2021) this paper takes the stance that language matters, for words gain their meaning from the way in which they are used (Wittgenstein, 2009). As the lead author’s critical reflections highlight, the changing of professional language from “mark making” to capturing feelings, mapping interests and needs, initiates a pedagogical move towards curriculum design that supports the acquisition of multiple forms of literacy, from photo elicitation to audio recordings. The significance of these multi-modal activities being the provision of varied ways for children to represent and hold onto their thinking, share it, revisit, and edit it, develop, discover, and redefine it. For “it is important to recognize there is nothing as slippery as a thought” (Eisner, 2005) and without such opportunities children’s inclusion and development is negatively impacted (Booth and Ainscow, 2016).

Limitations

We do not identify the focus on a single PR as a limitation since this would not be in the spirit of our counter hegemonic intention. Validating the voice, and the truth of one AIM PR is an expression of this commitment. However, it is recognized that policy makers are likely to be more convinced of the potential of engaging practitioners as co-researchers, if the cohort for analysis is larger. Our next step will be to gather data from all PRs, to present a more pluralist account of rationales and impacts.

Conclusion

The rationales for involving practitioners as co-researchers in the evaluation of Ireland’s Access and Inclusion Model (AIM) was at one level pragmatic, and at another level philosophical. At the pragmatic level, the evaluation team took the view that practitioner researchers (PRs) could bring a close-to-practice expertise to the research and evaluation process. These could not be equaled by a researcher who was distant from practice. In the case studies of pre-schools and children supported by AIM, PR’s were well positioned to identify and interpret the phenomena implicated in the construction (or deconstruction) of inclusion and participation. They were also more likely to report their interpretations in the vernacular of practice, deepening the relevance and impact of the findings. Readers will be able to review the results of their contribution in the DCEDIY’s publication of the AIM research reports.

The philosophical rationale for engaging PRs was counter hegemonic because it was deliberate resistance to workforce feminization, and to the way in which a feminized workforce is denied status or any claim to expertise. For the PR in this study, the role had a transformative impact on her expert identity and enriched her capitals for empowering others. She believed that the purpose of expertise, and an expert status was not to elevate one’s own authority, or rank. Instead, it was to be deployed to the enablement of others, and to practices focused on advocacy. In her gendered, critical reflection, the PR gives expertise a feminine framing, and positions within in it, the gendered-feminine practices of care, nurture, empathy, collaboration, and collegiality. In this way, professional potency and power can be observed in a gendered-feminine frame, rather than a gendered-masculine one (where dispositions such as competitiveness, objectivity or ruthlessness may be exalted). This is not to claim that feminine dispositions are enacted only by women, nor that masculine dispositions are without worth, but to argue that were such dispositions are aligned with concepts of professionalism, they are validated as expertise in ways that are particularly relevant to a feminized workforce. There were other impacts which included the development of a new language, and new research tools which could be deployed in pursuit of inclusive practice for children and their families. Here, the act of research, and membership of a community of researchers in the AIM evaluation, had inspired new ways understanding children, and families. ‘Everydayness’ was reframed as expert practice, and everyday practices were conferred more potency. Also observed were new ways for the PR to engage in transformations to practice through agency at the local and national level. On this point we conclude that validating the expert identity of ELC practitioners through engaging them as co-researchers in high profile evaluations has the potential to accelerate transformations at a sector level.

Finally, we commend the DCEDIY for supporting the integration of PRs as co-researchers in the project and encourage policy makers to embrace such approaches when designing or commissioning evaluations of high-profile policies or programs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The original studies involving human subjects were reviewed and approved by the University of Derby Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in these studies was provided by the participants and/or their legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

DS: Practitioner, LINC CPD Tutor at Mary Immaculate College, lead author, research practitioner, and content provider. ER: Dean of Early Childhood and Teacher Education at Mary Immaculate College and current Faculty Lead of Education at the College, Contribution: Foreword. DR: Professor of Special Educational Needs, Disability and Inclusion, Institute of Education University of Derby Lead researcher on the AIM end of 3 year evaluation and introduction lead with specific focus on feminist and gendered. SG: Researcher, research skills program rollout, and feminist theory content contributor. LOS: Head of Reflective Pedagogy and Early Childhood Studies at MIC Research content contributor on the impact of co-researching for practitioners. GC: Associate Professor - Research Institute of Education Content and literary review provider. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bezemer, J., and Kress, G. (2010). Changing text: a social semiotic analysis of textbooks. Designs Learn. 3:10. doi: 10.16993/dfl.26

Bolton, S., and Muzio, D. (2008). The paradoxical process of feminisationin the professions: the case of the established, aspiring and semi-professions. Work, Empoy. Soc. 22, 281–299. doi: 10.1177/0950017008089105

Booth, T., and Ainscow, M. (2016). The Index for Inclusion: A Guide to School Development Led by Inclusive Values. 4th. Cambridge: Index for Inclusion Network (IfIN).

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braverman, H. (1974). Labor and monopoly capital: The degradation of work in the twentieth century. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Braverman, H. (1998). Labor and monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in The Twentieth Century. New York: NYU Press.

Buyse, V., and Wesley, P. W. (2006). “Evidence-based practice: how did it emerge and what does it really mean for the earlychildhood field” in Evidence-Based Practice in the Early Childhoodfield. eds. V. Buyse and P. W. Wesley (Washington, DC: Zero to Three), 1–35.

Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education, CECDE (2006). Síolta: The National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education. Dublin: CECDE.

Codina, G. N., and Wharton, J. C. (2021). “The language of SEND: implications for the SENCO” in Leading on Inclusion: The Role of the SENCO. eds. M. C. Beaton, G. N. Codina, and J. C. Wharton (Nasen Routledge: Abingdon), 15–25.

Cullen, P. (2022). From feminised to feminist? Trade union campaigns for early years educators, nurses, and midwives in Ireland. Soc. Partners Gend. Equality, 245–269. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-81178-5_11

Eisner, E. W. (2005). Reimagining Schools: The Selected Works of Elliot W. Eisner. London; New York: Routledge (World Library of Educationalists Series).

Elson, D., and Pearson, R. (1981). “Nimble fingers make cheap workers”: an analysis of women’s employment in third world export manufaturing. Fem. Rev. 7, 87–107. doi: 10.1057/fr.1981.6

Government of Ireland. (2018a). First 5: A Whole-of-Government Strategy for Babies, Young Children, and Their Families 2019–2028. Dublin: Government of Ireland.

Government of Ireland. (2018b). First 5: Implementation plan 2019-2021. [Online]. Available at: https://first5.gov.ie/userfiles/pdf/5223_5156_DCYA_EY_ImplementationPlan_INTERACTIVE_Booklet_v1.pdf (Accessed June 01, 2020).

Gowers, S. J. (2022a). Making everyday meanings visible: investigating the use of multimodal map texts to articulate young children’s perspectives. J. Early Child. Res. 20, 259–273. doi: 10.1177/1476718X211062750

Gowers, S. J. (2022b). Mapping young children’s conceptualisations of the images they encounter in their familiar environments. J. Early Child. Lit. 22, 207–231.

Halliday, M. A. K. (2014). Language as social semiotic. The discourse studies reader. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 263–272.

Hayes, N., O’Donoghue-Hynes, B., and Wolfe, T. (2013). Rapid change without TRansformation: the dominance of a National Policy Paraigm over International influences on ECEC development in Ireland 195-2012. Int. J. Early Childh. 45, 191–205. doi: 10.1007/s13158-013-0090-5

Ireland (1937, 2018). Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na héireann). Dublin: The Stationery Office.

Jewitt, C. (2005). Multimodality, “reading”, and “writing” for the 21st century. Discourse Stud. Cult. Politics Educ. 26, 315–331.

McNeil, M. (1998). “Gender, expertise and feminism” in Exploring Expertise: Issues and Perspectives. eds. J. Fleck, W. Faulkener, and R. Williams (New York: Sage), 55–71.

Moloney, M. (2015). Progression or regression. Is the pre-school quality agenda perpetuating a care-education divide in the early childhood education and care sector in Ireland? Researchgate. Available at: https://childrensresearchnetwork.org/knowledge/resources/progression-or-regression. (Accessed November 30, 2018).

Murray, J., Swadener, B., and Smith, K. (2019). “Epilogue: Imaginig child rights futures,” in The Routlefge International Handbook of Young Children’s Rights (London: Routledge), 552–556.

National Council for Curriculum Assessment (NCCA) (2009). Aistear: The early childhood curriculum framework. Dublin: NCCA.

Osgood, J. (2006). Professionalisation and perforativity: the feminist challenge facing eary years practitioners. Early Years 26, 187–199. doi: 10.1080/09575140600759997

Palaiologou, I. (2019). Child Observation: A Guide for Students of Early Childhood (4th). London: Sage.

Phillips, A., and Taylor, B. (1980). Sex and skill: notes towards a feminist economics. Fem. Rev. 6, 79–88. doi: 10.1057/fr.1980.20

Ring, E. (2022). A History of Special Education in Ireland 1922–2022 [with Dr P.F. O’Donovan]. Trim: National Council for Special Education.

Ring, E., Kelleher, S., Kelleher, S., Heeny, T., McLoughlin, M., Kearns, A., et al. (2019a). Interim Evaluation of the Leadership for Inclusion in the Early Years (LINC) Programme, Limerick: Mary Immaculate College.

Ring, E., and O’Sullivan, L. (2019). Creating spaces where diversity is the norm. Child. Educ. 95, 29–39. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2019.1593758

Ring, E., O’Sullivan, L., and Ryan, M. (2019b). “Early childhood teacher-as-researcher: an imperative in the age of “Schoolification”: harnessing Dewey’s concept of the laboratory school to disrupt the emerging global quality crisis in early childhood education’” in Contemporary Perspectives on Research on Laboratory Schools in Early Childhood Education. ed. O. Saracho (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing), 173–193.

Silverman, D. (2011). Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Qualitative Data (4th). London: Sage.

Sisson Iverson, S. V. (2014). Disciplining professionals: a feminist discourse analysis of public preschool teachers. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 3, 217–230. doi: 10.2304/ceic.2014.15.3.217

Urban, M., Robson, S., and Scacchi, V. (2017). Review of Occupational Role Profiles in Ireland in Early Childhood Education and Care. Dublin: Department of Education and Skills.

Urban, M., Vandenbroeck, M., Van Laere, K., Lazzari, A., and Peeters, J. (2012). Competence Requirements in Early Childhood Education and Care. Final report. Brussels: European Commission.

Weiler, K. (1988). Women Teaching for Change: Gender, Class & Power. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group.

Keywords: research practitioner, early years and leadership, inclusion and aim, co-researching in evaluation, policy evaluation

Citation: Sheridan D, Robinson D, Codina G, Gowers SJ, O’Sullivan L and Ring E (2022) Engaging practitioners as co-researchers in national policy evaluations as resistance to patriarchal constructions of expertise: The case of the end of year three evaluation of the access and inclusion model. Front. Educ. 7:1035177. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1035177

Edited by:

Stefinee Pinnegar, Brigham Young University, United StatesReviewed by:

Renee Moran, East Tennessee State University, United StatesGloria Gratacós, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Sheridan, Robinson, Codina, Gowers, O’Sullivan and Ring. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Denise Sheridan, ZGVuaXNlam9hbm5hc2hlcmlkYW5AZ21haWwuY29t

Denise Sheridan

Denise Sheridan Deborah Robinson

Deborah Robinson Geraldene Codina

Geraldene Codina Sofia J. Gowers

Sofia J. Gowers Lisha O’Sullivan

Lisha O’Sullivan Emer Ring3

Emer Ring3