- 1Department of Surgery, Busitema University Faculty of Health Sciences, Mbale, Uganda

- 2Center for Health Equity in Surgery and Anesthesia, Institute for Global Health Sciences, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States

There has been a recent increase in dialogs around decolonization in global health. We present a perspective from global surgery emphasizing personal experiences around equity in barriers to education and surgical missions, citing specific personal challenges and local perceptions that we have experienced as well as potential solutions. We also cite fundamental challenges to the movement to decolonize global surgery, including donor-directed priorities and the creation of partnerships based in genuine bilateral exchange. We cite several models of current programs aiming to address some of these challenges.

Introduction

We know that the history of global health is inextricably tied to colonialism, so what does it mean to decolonize global health? (Castor and Borrell, 2022) Much has been written on the subject in recent years, enough so for it to be considered a movement (Kwete et al., 2022). But momentum alone does not make a movement as discourse without action does not lead to real change. Unfortunately, the movement to decolonize global health may have developed into an echo chamber of rhetoric, roadmaps, and buzzwords that upholds the very power dynamics it claims to dismantle (Khan et al., 2021). This explains why there is so much contention within the movement about what decolonization ought to look like (Chaudhuri et al., 2021; Mogaka et al., 2021; Finkel et al., 2022). Moreover, this is why we ought to take a step back and a closer look at the reality of the work as it exists today. Only then can we begin to determine what needs to happen next. In this article we hope to shed light on some of our personal experiences with teaching and learning in global health, some of the broader challenges that need to be addressed, and some of the ways forward that may lead to a new direction for the movement to decolonize global health.

Personal experiences in global health

Barriers to education

One of the most difficult things to reconcile as healthcare providers committed to achieving health equity for our communities is the constant reminder of how deeply entrenched so much of the work remains in colonial legacy. While there are more examples to share than we would like, it is important to highlight a few of the ongoing struggles in global health education. One example is a poignant testimony from one of our authors, Dr. Emmanuel Bua, a surgeon and scholar who reflects:

“Dear Emmanuel,

Thank you for your email. We do require an English language proficiency test from you, or a document explaining why you fulfill the waiver requirements listed below.”

This was the message I received when I applied for a short course in global health at one of the most reputable universities in the world. I wasn’t keen on writing that English language proficiency test, so I chose the other alternative – the ‘document’.

In this ‘document’, I tried to explain how I come from a commonwealth member state. I reminded them, just in case they had forgotten, that English is the official language in Uganda in all public places including schools, except for a few private language schools that also teach French, German and Chinese.

To build my case further I pointed out that all my education from kindergarten right through university was conducted in the English language. I hold a Master’s degree and several other academic fellowships, all done in the English language. To that end I was convinced there was no need to take an English language proficiency test in order to be eligible for the short course I had applied for. After all, I had already submitted a 500 word long personal statement written in the English language, if proficiency was anything to go by.

These and several other examples of intentional and unjustified barriers to equity in education are responsible for many of the inequalities that plague healthcare services globally.

The decolonization movement in global health has largely focused on healthcare delivery, however, not much has been written or done to address the widespread challenges in accessing medical education which are a byproduct of the very structures that the movement hopes to dismantle. Not only are these challenges often intentional and unjustified but also they are detrimental to the communities that would stand to benefit most from access to medical education. For example, while it may not require much for a specialist trainee from the global north to spend time in the global south studying or carrying out research, it is often extremely difficult if not impossible for their counterparts from the global south to access the same opportunities in the global north. Even those who can take advantage of such opportunities routinely face additional challenges and frustrations (Pai, 2022). We must recognize how deeply rooted global health remains in the colonial mindset because we cannot change what we do not acknowledge. An increasing number of groups have called for a fundamental re-evaluation of global health education with emphasis on curricula and anticolonialism (Garba et al., 2021). Nonetheless, some of the momentum may be excessively originating in high-income countries (HICs) rather than low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs). We urge programs not only to re-evaluate their own curricula and objectives but also to ensure that this process is primarily driven by LMICs – even for something as simple as revisiting the definition of a term like “global surgery” (Jayaram et al., 2021).

Surgical missions

Another area with which we have extensive experience is the tradition of surgical missions and camps. These were originally conceived with the intent of reaching out to communities that lack access to surgical care. In these camps surgeons and their teams from HICs visit and offer surgical services to LMICs, however the utility of this model has been under ongoing scrutiny (Botman et al., 2021). The general observation by many hosts is that most visiting members of surgical camps often lack standardized patient selection methods and routinely neglect to plan for patient follow-up after the camp. Unless a system has been set in place, the departure of the visiting team signals the end of their contact with the patient, and the local health care personnel are left to handle any complications.

Most surgical camps are disease specific and do not necessarily address the most urgent needs of the communities. Common examples include surgery for cleft lip and palate, obstetric fistula, and clubfoot among others. Meanwhile procedures to treat acute traumatic injuries or general surgical conditions, especially emergency conditions, are less likely to be prioritized.

Once the visiting team arrives, the normal function of the local hospital may cease. The operating rooms may be taken over, the anesthesiologists and other human and material resources diverted away from routine care, and the nursing teams and local staff sidelined in favor of those from the visiting team regardless of their training or experience. Such missions frequently disturb the daily work of the LMIC hospital and overlook any exchange of knowledge, introduction of novel techniques, or improvement of operative skills. The visiting surgeon may even be less qualified than the local surgeon because the local surgeon has a better understanding of the local health care system, familiarity with advanced disease pathology that they see more frequently, and knowledge of the limitations that patients will face after discharge.

The huge cost of running these camps mainly stems from the visiting team as they tend to arrive in big numbers with some coming primarily for a tour of the continent. The teams often include public relations officers, photographers, IT specialists, nurses, surgeons, and students. They tend to stay in expensive five-star hotels for the duration of the camp, which is usually crowned with a week-long post-camp adventure through national parks and tourist attractions as a reward for their own hard work. Many of the team members are either non-essential or their services can and should be sourced locally from the host community.

Despite these all-too-common scenarios, most volunteers are well intentioned. However, some may arrive with a “savior mentality.” Their true objective may be to take the perfect picture (i.e., “the selfie”) with a destitute patient that can be shared on social media. Therefore, HIC providers who wish to get involved in surgical camps must be aware of their limitations regarding the local disease burden and acknowledge that their participation can, in fact, be disruptive. They should be willing to work with the local staff as much as possible. This helps to reciprocate the true spirit of global health, one focused on genuine bilateral exchange, collaboration, and partnership (Foretia, 2022).

In Uganda, the Association of Surgeons of Uganda has required that all international groups register their surgical outreach and mission trips with local groups, with clear plans for patient recruitment, follow up, and an agreement with a local clinical leader. This is in effort to minimize harm while still providing these often-essential services. Other groups have also tried to provide guidelines for short-term surgical work (Butler et al., 2018), while locally led surgical missions and camps within Uganda have also been shown to be effective and sustainable (Galukande et al., 2016).

Local perceptions

Another often overlooked aspect of the colonial mindset that permeates global health and especially global surgery is the all too hypnotizing colonial gaze. While it is well known that much of colonial history is written by, centered on, and flattering to the colonizer, we must recognize the importance not only of acknowledging our own shortcomings but also of respecting the perspectives of the very communities in which we work (Chaus, 2020). For many years expatriate physicians have taken on diverse roles in underserved settings globally, including in the provision of clinical care, research, education, and mentorship. In the United States, 31% of medical students participate in international experiences, over 50 residency programs offer global health tracks and international rotations, and over 6,000 medical mission trips originate annually (Parekh et al., 2016).

These experiences are overwhelmingly positive from the perspective of the visiting providers, not to mention their glowing statistics that often justify the means: physicians with global health experiences are more likely to work with underserved populations and engage in community service opportunities back home (Parekh et al., 2016) Reported benefits include gaining experience with diverse pathologies, learning to work with limited resources, developing clinical and surgical skills, participating in education, and experiencing new cultures (Parekh et al., 2016). Furthermore, in the setting of LMICs, expatriate physicians can serve important roles in addressing physician shortages and helping to establish medical education infrastructure (Kisa et al., 2019).

However, there seem to be knowledge gaps regarding the perception that local hosts have of the benefits of these programs, and of their influence on host institutions, physicians, and trainees (Zivanov et al., 2022). Such benefits should include genuine bilateral exchanges whereby both local hosts and expatriates are able to participate in reciprocal visits, training, and research as true partners, rather than the hosts becoming recipients of the visiting saviors’ charitable goodwill. These concerns are not new and have been raised in various evaluations of “hosts,” including in Uganda (Elobu et al., 2014; Velin et al., 2022).

These are just a few of the examples that we have seen and experienced firsthand in our own work, but we have no doubt that there are countless others that occur daily around the world. Some have been written about as of late, but most have yet to be acknowledged let alone published. As global surgery grows and develops into a field of its own, and as we continue to recognize the importance of surgical systems as a cross-cutting part of healthcare in general, it is critical that we acknowledge and address the immense inequalities that exist in global health education. More specifically, the immense inequalities that pertain to surgical education in LMICs.

Fundamental challenges to the decolonization movement

Having highlighted some of our own experiences and observations with the colonial legacy of global health education, we also wanted to bring attention to some of the core challenges that remain as the decolonization movement continues; the core challenges that are often intentionally overlooked or minimized because they seem too big to tackle. While there is a lot of focus being placed on the idea of decolonization from an academic perspective, that focus often takes away from many of the structures and systems in place that are so deeply rooted in colonialism to begin with and which perpetuate the very challenges that the decolonization movement is attempting to address.

Genuine bilateral exchange

The first of these broad challenges remains the notion of genuine bilateral exchange. Much has been written on this, and we have referred to this idea several times within this article, but we must take a closer look at what this vague prescription really entails. We would argue that partnerships and collaborations which aim to provide bilateral exchange through shared research publications, coordinated teaching efforts, and local capacity building are not enough. While all these endeavors are certainly encouraged and a step in the right direction, if we truly want to decolonize global health and specifically global surgery then we must ensure that every opportunity that is afforded to a HIC partner should also be afforded to an LMIC partner. Clearly there are overwhelming, systematic barriers to such bilaterality but these same barriers are precisely what the decolonization movement ought to be focused on. HIC partners should actively advocate for the same kind of clinical and research opportunities for LMIC partners at their own institutions, with the same level of autonomy and participation, especially if this requires advocacy in the realm of policy (Pai, 2022). If the decolonization movement is to be taken seriously in both its efforts and its intentions, then genuine bilaterality must be at the forefront of all future advocacy and programmatic planning (Scheiner et al., 2020).

Centralization of services

Another broad challenge we have noticed in our work is the centralization of services. While this remains a challenge in most health care systems globally, it is an extremely pronounced challenge in many LMICs (Sund et al., 2022). Tradition holds that the best academic medical centers the world over exist in urban environments, often leaving rural communities to rely on aid-based, unilateral programs for support. This can lead to an unintentional domestic brain drain whereby healthcare providers either want to or have to leave their communities for these urban centers to find the opportunities they have worked so hard to obtain (Gajewski et al., 2020). And again, while this challenge is not unique to LMICs by any means, the consequences of this centralization of services can be devastating for the communities that are unable to access such services. If the decolonization movement in global health is to have any success, it will be measured by the sustainability and independence of the very healthcare systems that have long suffered in the legacy and shadows of colonialism. For these very reasons, the internationalization of medical education in the context of the decolonization movement must also explicitly focus on rural communities as a vital part of healthcare systems.

Donor directed priorities

Lastly, one of the greatest challenges to global health and particularly global surgery is the phenomenon of donor-directed priorities. While often unintentional, the healthcare priorities set by donors and foreign aid institutions rarely reflect the true needs of the recipients (Olusanya et al., 2021). Furthermore, these priorities can have unpredictable downstream effects that only worsen the gaps in healthcare services (Parsons, 2022). A very pertinent example of this can be seen in the way that infectious diseases have affected the healthcare workforce in Uganda. In a nation with a longstanding history of receiving aid specifically earmarked and targeted for infectious diseases, the very notion of which is stained by the colonial tendency to solve problems “elsewhere” so that they do not become a problem at “home,” donors have directed the priorities of an entire healthcare system away from the greatest need. It is well known now that globally HIV, TB, and malaria combined have a lower annual mortality rate than traumatic injuries alone (Meara and Greenberg, 2015). And this does not even include the mortality caused by a lack of access to various other essential surgical procedures. Despite this, there is virtually no funding from major international healthcare organizations for the prevention and treatment of traumatic injuries when compared to the funding available for infectious diseases. And while this may seem like an obvious oversight, it remains a surprisingly neglected truth. The most dangerous part, however, is how these priorities influence the decisions of future healthcare workers. A survey of medical students across Uganda revealed that the overwhelming majority wanted to pursue a career in infectious disease, largely because that is the specialty with the most funding and in turn the most well-paying jobs, despite the immense burden of disease from other specialties such as surgery (Kakembo et al., 2020) This is just a single example of what is undoubtedly a widespread consequence of how donor-directed priorities can negatively impact medical education and in turn the medical workforce.

Current advances in global health programs

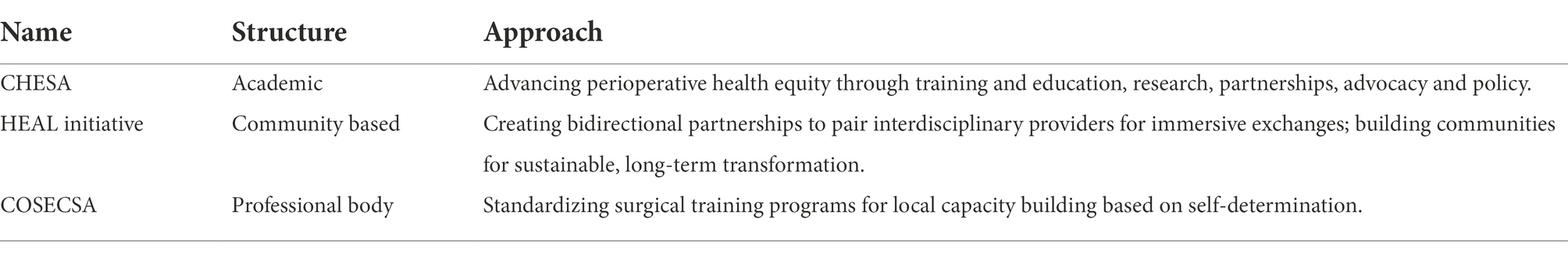

Once we start from a place of clarity and accountability, then it is not only possible but also inspiring to set anticolonial intentions and to put them to work. And this cannot happen in isolation, in fact it must happen in collaboration or else the decolonization movement will never gain the momentum it needs to achieve any genuine, lasting change (Table 1).

There are several institutions and organizations that have committed to precisely this kind of work, including the Center for Health Equity in Surgery and Anesthesia (CHESA) and the Health, Equity, Action, and Leadership (HEAL) Initiative, both of which are based out of the University of California San Francisco (UCSF; Figure 1). Both of these programs also aim to address disparities within the local health care system in the United States, where institutions and structures entrenched in racism similarly to those entrenched in colonialism remain a major threat to public health. We see very similar strands of essential action between the movement to decolonize global health and advance an antiracist agenda.

Furthermore, the College of Surgeons of East, Central, and Southern Africa (COSECSA), which has made sustainable impact on local capacity building by investing in the current and next generation of surgeons across the region by embracing a model of “learning without borders” such that trainees do not have to leave their place of work in often rural and essential hospitals to gain qualification as a specialist surgeon (Mulwafu et al., 2021) Such programs have devised new and innovative models for global health education and care delivery that are rooted in the core values of anticolonialism such as equity, justice, and self-determination.

Discussion

Decolonizing global health, and particularly the internationalization of medical education, is a necessary part of achieving health equity for all populations. This is no easy task, and we admit that it will require a process in tandem – where we intentionally create anew while simultaneously learning from the old with the ultimate goal of leaving colonial systems and institutions behind once and for all. This process requires that we first bring awareness to and take responsibility for our own actions because we are all complicit.

Many have shared their perspective, offered suggestions, and made recommendations about the most practical and necessary next steps to carry the decolonization movement forward (Pai, 2021). In addition to these, we believe that incorporating an anticolonial mindset and intention into the very way we do the work is paramount to the success of any such movement (Foretia, 2022). This means transforming the very way we teach and learn about global health, with the ultimate transformation coming from the creation of brand-new systems, institutions, and programs to support the work. Such novel approaches to global health require a certain awareness of our own individual biases and tendencies and how they relate to both the historical and ongoing colonial impact on health equity. Only with this awareness will it be possible to dismantle colonial legacies while learning from their very real and very widespread ramifications, several examples of which we have shared in this article as mere footnotes to the realities of global health as we know it today.

Clearly there is much work to be done, and there are many different ways to do it, but from our perspective the only way to bring the decolonization movement to fruition is to shift its focus entirely from fixing old problems to creating new solutions. Most importantly, this shift must be led by, prioritized for, and centered on the very communities that have long been denied not only their seat at the head of the table, but also their very own tables (Oti and Ncayiyana, 2021).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SS and EB contributed in its ideation, preparation, writing, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Botman, M., Hendriks, T. C. C., Keetelaar, A. J., Smit, F. T. C., Terwee, C. B., Hamer, M., et al. (2021). From short-term surgical missions towards sustainable partnerships. A survey among members of foreign teams. Int. J. Surg. Open 28, 63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ijso.2020.12.006

Butler, M., Drum, E., Evans, F. M., Fitzgerald, T., Fraser, J., Holterman, A., et al. (2018). Guidelines and checklists for short-term missions in global pediatric surgery. Pediatr. Anesth. 28, 392–410. doi: 10.1111/pan.13378

Castor, D., and Borrell, L. N. (2022). The cognitive dissonance discourse of evolving terminology from colonial medicine to global health and inaction towards equity – a preventive medicine Golden Jubilee article. Prev. Med. 163:107227. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107227

Chaudhuri, M. M., Mkumba, L., Raveendran, Y., and Smith, R. D. (2021). Decolonising global health: beyond ‘reformative’ roadmaps and towards decolonial thought. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006371. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006371

Chaus, M. (2020). The dark side of doing good: a qualitative study to explore perceptions of local healthcare providers regarding short-term surgical missions in Port-Au-Prince. Haiti. J. Global Health Rep. 4. doi: 10.29392/001c.11876

Elobu, A. E., Kintu, A., Galukande, M., Kaggwa, S., Mijjumbi, C., Tindimwebwa, J., et al. (2014). Evaluating international global health collaborations: perspectives from surgery and anesthesia trainees in Uganda. Surgery 155, 585–592. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.11.007

Finkel, M. L., Temmermann, M., Suleman, F., Barry, M., Salm, M., Bingawaho, A., et al. (2022). What do Global Health practitioners think about decolonizing Global Health? Ann. Glob. Health 88:61. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3714

Foretia, D. A. (2022). To decolonize global surgery and global health we must be radically intentional. Am. J. Surg. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2022.10.015

Gajewski, J., Wallace, M., Pittalis, C., Mwapasa, G., Borgstein, E., Bijlmakers, L., et al. (2020). Why do they leave? Challenges to retention of surgical clinical officers in district hospitals in Malawi. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 11, 354–361. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.142

Galukande, M., Kituuka, O., Elobu, E., Jombwe, J., Sekabira, J., Butler, E., et al. (2016). Improving surgical access in rural Africa through a surgical camp model. Surg. Res. Pract. 2016:9021945. doi: 10.1155/2016/9021945

Garba, D. L., Stankey, M. C., Jayaram, A., and Hedt-Gauthier, B. L. (2021). How do we decolonize Global Health in medical education? Ann. Glob. Health 87:29. doi: 10.5334/aogh.3220

Jayaram, A., Pawlak, N., Kahanu, A., Fallah, P., Chung, H., Valencia-Rojas, N., et al. (2021). Academic global surgery curricula: current status and a call for a more equitable approach. J. Surg. Res. 267, 732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2021.03.061

Kakembo, N., Situma, M., Williamson, H., Kisa, P., Kamya, M., Ozgediz, D., et al. (2020). Ugandan medical student career choices relate to foreign funding priorities. World J. Surg. 44, 3975–3985. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05756-z

Khan, M., Abimbola, S., Aloudat, T., Capobianco, E., Hawkes, S., and Rahman-Shepherd, A. (2021). Decolonising global health in 2021: a roadmap to move from rhetoric to reform. BMJ Glob. Health 6:e005604. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005604

Kisa, P., Grabski, D. F., Ozgediz, D., Ajiko, M., Aspide, R., Baird, R., et al. (2019). Unifying Children’s surgery and anesthesia stakeholders across institutions and clinical disciplines: challenges and solutions from Uganda. World J. Surg. 43, 1435–1449. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-04905-9

Kwete, X., Tang, K., Chen, L., Ren, R., Chen, Q., Wu, Z., et al. (2022). Decolonizing global health: what should be the target of this movement and where does it lead us? Global Health Res. Policy 7:3. doi: 10.1186/s41256-022-00237-3

Meara, J. G., and Greenberg, S. L. M. (2015). The lancet commission on global surgery global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery 157, 834–835. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.009

Mogaka, O. F., Stewart, J., and Bukusi, E. (2021). Why and for whom are we decolonising global health? Lancet Glob. Health 9, e1359–e 1360. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00317-x

Mulwafu, W., Fualal, J., Bekele, A., Itungu, S., Borgstein, E., Erzingatsian, K., et al. (2021). The impact of COSECSA in developing the surgical workforce in east central and southern Africa. Surgeon 20, 2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2021.11.003

Olusanya, J. O., Ubogu, O. I., Njokanma, F. O., and Olusanya, B. O. (2021). Transforming global health through equity-driven funding. Nat. Med. 27, 1136–1138. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01422-6

Oti, S. O., and Ncayiyana, J. (2021). Decolonising global health: where are the southern voices? BMJ Glob. Health 6:e006576. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006576

Pai, M. (2021). Decolonizing Global Health: a moment to reflect on a movement. Forbes Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2021/07/22/decolonizing-global-health-a-moment-to-reflect-on-a-movement/?sh=80e5b1 453862 (Accessed 29 October 2022).

Pai, M. (2022). Passport and visa privileges In Global Health.. Jersey City, NJ, United States: Forbes Available at: https://www.forbes.com/ sites/madhukarpai/2022/06/06/passport-and-visa-privilegesin-global-health/ (Accessed 29 October 2022).

Parekh, N., Sawatsky, A. P., Mbata, I., Muula, A. S., and Bui, T. (2016). Malawian impressions of expatriate physicians: a qualitative study. Malawi Med. J. 28, 43–47. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v28i2.3

Parsons, M. A. (2022). Toward an ethics of global health (de)funding: thoughts from a maternity hospital project in Kabul, Afghanistan. Glob. Public Health 17, 1136–1151. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2021.1924821

Scheiner, A., Rickard, J. L., Nwomeh, B., Jawa, R. S., Ginzburg, E., Fitzgerald, T. N., et al. (2020). Global surgery pro–con debate: a pathway to bilateral academic success or the bold new face of colonialism? J. Surg. Res. 252, 272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.01.032

Sund, G., Huang, A. H., Mascha, E. J., Miburo, C., Machemedze, S., Razafimanantsoa, M., et al. (2022). Delays to essential surgery at four faith based hospitals in rural sub-Saharan Africa. ANZ J. Surg. 92, 228–234. doi: 10.1111/ans.17433

Velin, L., Lantz, A., Ameh, E. A., Roy, N., Jumbam, D. T., Williams, O., et al. (2022). Systematic review of low-income and middle-income country perceptions of visiting surgical teams from high-income countries. BMJ Glob. Health 7:e008791. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008791

Zivanov, C. N., Joseph, J., Pereira, D. E., Mac Leod, J. B. A., and Kauffmann, R. M. (2022). Qualitative analysis of the host-perceived impact of unidirectional global surgery training in Kijabe, Kenya: benefits, challenges, and a desire for bidirectional exchange. World J. Surg. 46. doi: 10.1007/s00268-022-06692-w

Keywords: decolonization, health equity, global surgery, global health education, perspective

Citation: Bua E and Sahi SL (2022) Decolonizing the decolonization movement in global health: A perspective from global surgery. Front. Educ. 7:1033797. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1033797

Edited by:

Anette Wu, Columbia University, United StatesReviewed by:

Joseph Grannum, Tartu Health Care College, EstoniaCopyright © 2022 Bua and Sahi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saad Liaqat Sahi, c2FhZC5zYWhpQHVjc2YuZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Emmanuel Bua1†

Emmanuel Bua1† Saad Liaqat Sahi

Saad Liaqat Sahi