- 1Department of Arabic Education, Institut Agama Islam Negeri, Kendari, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia

- 2Department of Educational Leadership, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States

- 3Department of English Education, Universitas Islam Malang, Malang, East Java, Indonesia

- 4Department of Shariah Economic Law, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta, South Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia

- 5Department of Islamic Family Law, Universitas Nahdlatul Ulama Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

Much research on textbook analysis has looked at diverse perspectives nested by the textbook authors, including gender equality. Although a growing body of research on gender representation in textbooks has been undertaken, there is a paucity of research on Arabic textbooks. This study aims to examine gender representation in Arabic textbooks for Islamic school students approved by the Ministry of Religion of Indonesia to fill the research gap. This research employed a case study design focusing on three textbooks. The researchers utilized thematic analysis anchored in Rifkin’s theory. The findings show that (1) gender representation in Arabic textbooks, verbally and visually, is dominated by men, (2) gender representation is visualized from six themes showing male dominance except for the theme “traveling,” which is dominated by women, and (3) the pedagogical actions that need to be taken to overcome these problems are (a) Arabic language teachers need to develop materials when using government-endorsed Arabic textbooks and (b) the Ministry of Religious Affairs should promote gender equality through recommended textbooks.

Introduction

In the last decades, much research on textbook analysis has been enacted using multiple perspectives (Syairofi et al., 2022), including the essence of gender in textbooks. Gender issues have permeated many aspects of our lives, emphasizing gender equality in education, status, awareness, and access to socioeconomic possibilities (Khan, 2011). In the Indonesian context that adopts democratic ideology, the government is concerned with achieving gender equality, as required by Article 27(1) of the 1945 Constitution, which reveals that every citizen has equal standing before the law. Therefore, regardless of their racial, religious, political, economic, or gender backgrounds, all Indonesian people are required to be treated equally before the law and given equal opportunity to contribute to the nation’s development (Lopez-Zafra and Garcia-Retamero, 2012). In the same vein, Reeves (1987) contends that the Indonesian government formally endorses equal rights for its people to pursue decent employment and good education. This phenomenon may be traced through the long history of the attempts of Indonesian women to obtain equal rights through education such as Kartini, Dewi Sartika, Maria Walanda Maramis (Porter, 2001; Setyono, 2018; Widodo, 2018), and the struggle against Dutch colonialism such as Tjut Nya Dhien and Martha Christina Tiahahu (Poerwandari, 1999).

In the education sector, gender concerns have been extensively covered as a salient issue that emerged in many textbooks. Specifically, the issues related to gender and education identified in textbooks include gender representations, gender stereotypes, and the under-representation of women in school textbooks. For instance, after examining textbooks used in Japan, Hong Kong, Australia, Uganda, Pakistan, and Morocco, many scholars have found that most of the objects and pictures in those textbooks represent the idea of masculinity (Ullah and Skelton, 2013; Gebregeorgis, 2016; Cobano-Delgado and Llorent-Bedmar, 2019; Lee, 2019; Namatende-Sakwa, 2019). Gender inequality issues in textbooks also persist in the United States. Atchison (2017) reported that gender is not well represented in the textbooks used in schools and universities in the United States. Similarly, the same issues exist in the Arab world. It was found in a discourse analysis study that was conducted on 35 textbooks in Iran, including Persian, Arabic, and English, that male representation generally dominated (Foroutan, 2012). Al-Qatawneh and Al Rawashdeh (2019) reviewed ninth-grade Arabic textbooks in the UEA and discovered that masculinity terms appear more than feminist ones. Earlier, Baghdadi and Rezaei (2015) argued that although women’s education is increasing in Iran, men’s masculinities are portrayed in English and Arabic textbooks. Similarly, using critical micro-semiotic analysis, Ariyanto (2018) found a significant gender bias and many gender stereotypes in the form of visual and verbal representations in English language teaching (ELT) textbooks published by the Indonesian Ministry of Education. In the same vein, Setyono (2018) indicated unequal representations of male and female characters in most English as a foreign language (EFL) textbooks used in Indonesian schools. Furthermore, Damayanti (2014) reported that women were depicted as more dependent on men and were also seen as admirers of men’s actions in some textbooks used in Indonesian schools. Additionally, Agni et al. (2020) demonstrated that gender bias in the EFL textbooks in Indonesia could be seen from visual and textual representations, various activities, roles, occupations, and adjective descriptions.

Although gender inequality in Indonesian textbooks has been examined using multilayered angles, Arabic textbooks have received little attention. Also, most studies were focused on English textbooks endorsed by the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Education that are used for elementary, junior, and senior high school students. Still, the Arabic textbooks endorsed by the Ministry of Religion for high school students have not yet been extensively examined. These two ministries in Indonesia have different educational policy directions, which may also affect the content of textbooks. This study aimed to explore gender representation in government-endorsed Arabic language textbooks used in Indonesian Islamic junior high schools to address this void.

Therefore, three questions are addressed in the present study:

1. What is the percentage of gender (male and female) representation in government-endorsed Arabic language textbooks used in Indonesian Islamic junior high schools?

2. In what ways are men and women presented and portrayed in those textbooks?

3. What pedagogical actions may be taken to address gender inequalities in those textbooks?

Theoretical underpinnings

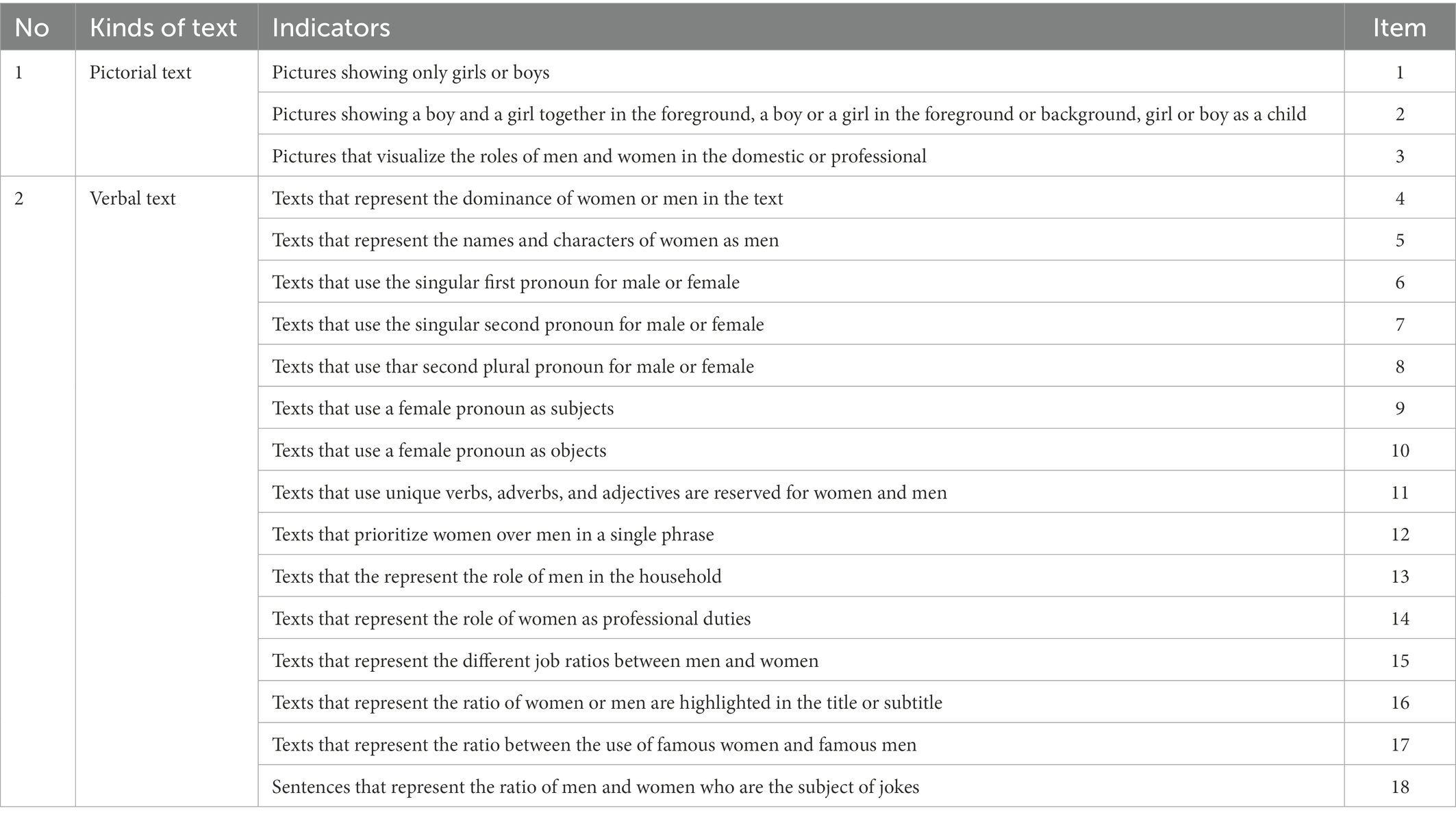

The current study employs the modified theory of Rifkin’s (1998) gender inequity. The researchers modified the theory because of the different contexts of foreign language textbooks used in Russia, especially the use of pronouns, which cannot be applied in the Arabic textbooks used in Indonesia. In this case, gender inequity in textbooks was revealed to consist not only of verbal texts but also pictorial texts. This indicator can be observed in the following description (Table 1).

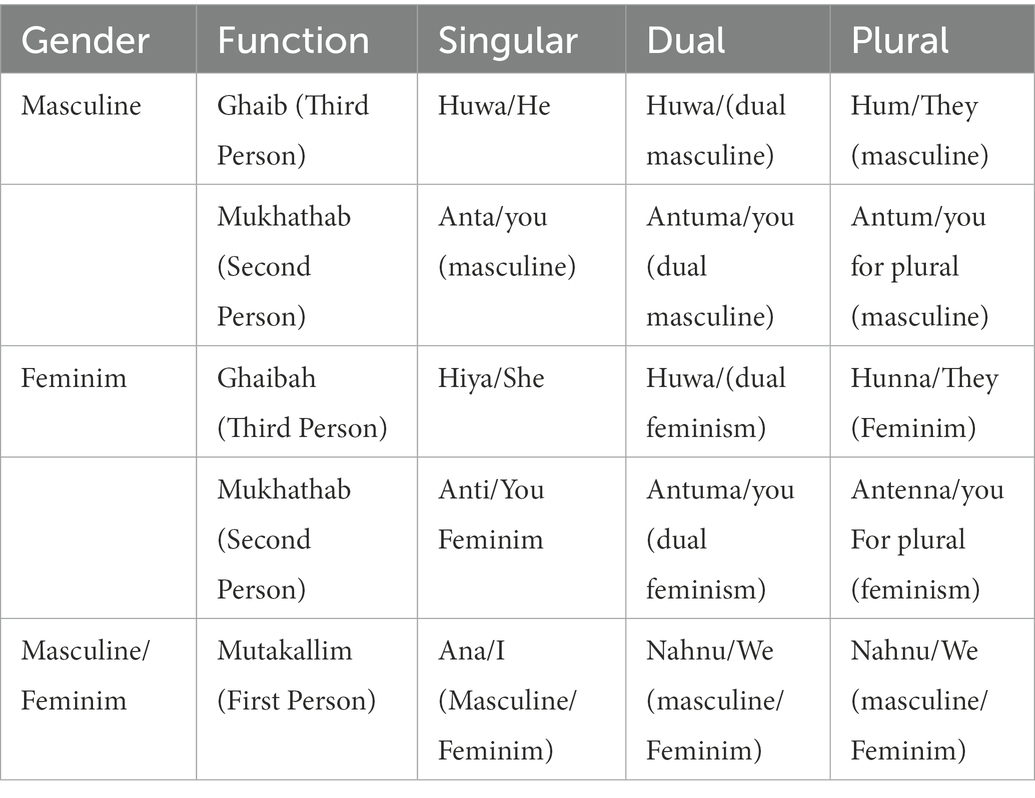

However, Rifkin’s (1998) concept of the gender inequality indicator cannot be used entirely to analyze the data in this study. The theory was modified based on the Arabic language context. This was because, on a micro-basis, Rifkin (1998) does not separate indicators of the use of the pronoun, both first, second, and third person, and singular or plural. At the same time, in Arabic grammar, the use of pronouns always separates the use of aspects of pronouns from all genders and number aspects, as applied in this study.

As a result, the development of the theory was conducted to be used as an analytical tool in analyzing Arabic textbooks not only in the context of Indonesia but also in the context of other countries in Southeast Asia. Empirically, it was discovered in this study that the Arabic language is gender-neutral because every word has a partner. However, some words contain gender biases because of the incompetence of the writer, the strong patriarchal culture, and the influence of the understanding of authors regarding religious doctrine. Such an understanding of the religious doctrine is inadequate, making religion the main reason for gender subordination and stereotypes. In policy, the government, as the policymaker, needs to ensure that the content of textbooks for Islamic senior high school (Madrasah Aliyah) students has been tested and selected nationally, not perpetuating gender bias. Therefore, the recruitment process of textbook authors should be conducted more selectively and professionally and not based on nepotism or “pointing out.”

Gender representation issues in Indonesia

Gender equality has been openly discussed since the 1960s, even before Indonesian independence. The issue of gender equality arose from the awareness of women toward their lag compared with men (Mas’udah, 2020). Regarding quality and quantity, women are still far behind men (Setyono, 2018). Thus, the struggle for gender equality is a long process that has yet to end (Kochuthara, 2011). This condition is motivated by numerous factors. First, the patriarchal culture tends to monopolize and legitimize male domination. Second, Indonesia is a multiethnic and multi religious country. Third, policymakers have not fully internalized and integrated the understanding of gender equality. Also, gender equality has not been implemented according to development programs and activities, including in the education sector (Kochuthara, 2011; Litosseliti, 2014; Romera, 2015; Setyono, 2018). Gender equality is a concept used to identify the engagement balance between men and women in social, cultural, and other non-biological aspects.

Five indicators measure gender equality and inequality: subordination, marginalization, double burden, violence, and stereotyping. The first indicator is subordination, considering that the workload performed by a specific gender is lower than others (Setyono, 2018; Lestariyana et al., 2020). In this respect, a housewife who domestically works for her family is not considered to have a job. The second indicator is marginalization, which appears when the gender gap between men and women in the formal and informal sectors is inversely related. Women are more involved in informal sectors, while men dominate the formal sectors. The third indicator is a double burden—the reproductive role of women has often been considered a static and permanent role. Therefore, even though women work in the public sphere, this has not been accompanied by a reduction in their burden in the domestic sphere. The fourth indicator is violence—the characteristic of women is always identified as feminism. Consequently, they need to show tenderness and submissiveness. On the other hand, men are always considered masculine. Therefore, it is necessary to appear with courage and strength. As a result, the characteristics portrayed impact acts of violence against the weak. The fifth indicator is stereotyping—all forms of gender inequalities are from stereotyping, which can mislead and harm certain genders (Kochuthara, 2011; Ganguli et al., 2014; Mas’udah, 2020).

Gender representation in Arabic textbooks

Studies of gender representation in Arabic textbooks are limited compared with those in English textbooks. Scholars have consistently found gender inequalities and gender biases in Arabic and non-Arabic textbooks. In non-Arabic textbooks, most of the research conducted around the world presents examples of gender representation such as stereotypes, biases, norms, and ideological discourses that are detrimental to women. Carlson and Kanci (2017) reported that in Turkey, men are depicted as protectors, while women are objects to be protected. The main role of women is motherhood even though they have several other social roles outside the home. This is due to the influence of the culture of “enemies” and “defense” that shapes masculinity around the concept of the “warrior-protector.” Lee's (2019) research shows that in contemporary Japan, men occupy more social roles outside the home as breadwinners, while women are expected to stay at home. Not unlike Japan, English textbooks in China depict women as being inferior to men because they are influenced by the Confucian culture despite the government’s efforts to eliminate the gender gap in the textbooks. In Uganda, a research report by Namatende-Sakwa (2018) shows that women are constructed to have a physical appearance like men and are highly dependent on men as providers of sustenance. This is influenced by the traditional patriarchal culture of the agricultural economy that circulates among them. In Poland, Pakuła et al. (2015) revealed that men are represented in a strong position, while women are stereotyped as weak. In Vietnam, men in textbooks have more social traits and occupy a larger verbal space. Meanwhile, women are represented as people who are less independent, have limited choices, and have limited knowledge of resources. It is influenced by patriarchal Confucian values (Vu and Pham, 2021).

In Arabic textbooks, Foroutan (2012) found three variations of gender representation patterns in three Iranian language textbooks: Persian, Arabic, and English. First, a male is more represented in textbooks than a female. Second, male domination appears more frequently in Persian textbooks compared with Arabic and English textbooks. Third, there are similar representations between men and women in English textbooks. Baghdadi and Rezaei (2015) and Foroutan (2012) revealed that Arabic textbooks have more gender biases than English textbooks. It was shown in the results of the data analysis that the frequency of female representation was consistently lower than male representation in all categories from 10 criteria, either pictorial or textual. Furthermore, it was found that there was a notable change in educational level regarding gender representation. It was shown that the more the education level increased, the more the male gender dominated. It was shown in similar research by Al-Qatawneh and Al Rawashdeh (2019) in the UEA that, although textbook authors try to convey positive messages of support for gender equality, social stereotypes still occur in Arabic textbooks. Thus, the previous literature shows that gender representation in textbooks has been carried out by many world experts, especially English textbooks, and is still limited to studying Arabic textbooks in the context of Indonesia which is multicultural, multilingual, and multi-religious. It is for this reason that this research was conducted.

Pedagogical actions to address gender inequalities

The issue of which pedagogical actions can be applied to overcome gender inequalities has been examined by many researchers. Dunne et al. (2006) emphasized the importance of advocacy for teachers as agents of change with adequate attitudes and experiences about gender equality as a form of resistance to gender inequality and violent practices. Sulaimani (2017) requires teachers to act against gender bias in textbooks. Bandura (2003) highlighted that formal education is essential for gender development in their social cognitive theory. This is especially true in the learning environment created through education in which people think positively or negatively (Bandura et al., 2003; Romera, 2015). One factor that influences the learning styles, attitudes, and thoughts of students is the representation of gender in textbooks. In the case of gender stereotypes or biases that appear in textbooks, students directly or indirectly practice them in everyday life (Bandura et al., 2003; Lee, 2018). Therefore, gender equality must receive attention in the curriculum at all levels of education. As reported by Sunderland (2000), teachers in Portugal prefer not to be fixated on the text and innovate on their own in discussion topics. Stromquist (1998) indicated that textbooks and curriculum content last a long time in memory so what is heard, seen, told, read, and written about the treatment of men and women will condition the mind.

With this in mind, gender mediates student learning in the classroom. It, for example, drives students to construct and negotiate their identities when interacting with different gendered peers. Pedagogically, teachers are encouraged to provide equitable learning activities for both male and female students in the classroom, even when the textbooks used contain gender bias. Teachers’ teaching strategies can be enacted through initial awareness of gender represented in the textbooks.

Methods

Research design

A critical content analysis design was adopted in this empirical research. Content analysis refers to a research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts (or other meaningful matters) to the contexts of their use (Krippendorff, 2004, p. 18). Numerous scholars studying language textbooks have used content analysis to analyze gender content using quantitative and qualitative approaches (Risager, 2018). This study goes beyond mere content analysis to illuminate how gender is represented in textbooks. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were employed in this critical content analysis. A quantitative analysis was also used to determine the percentage and frequency of gender representation in the textbook. Then, a qualitative method was used to analyze the deep structural meaning of the data.

Data collection

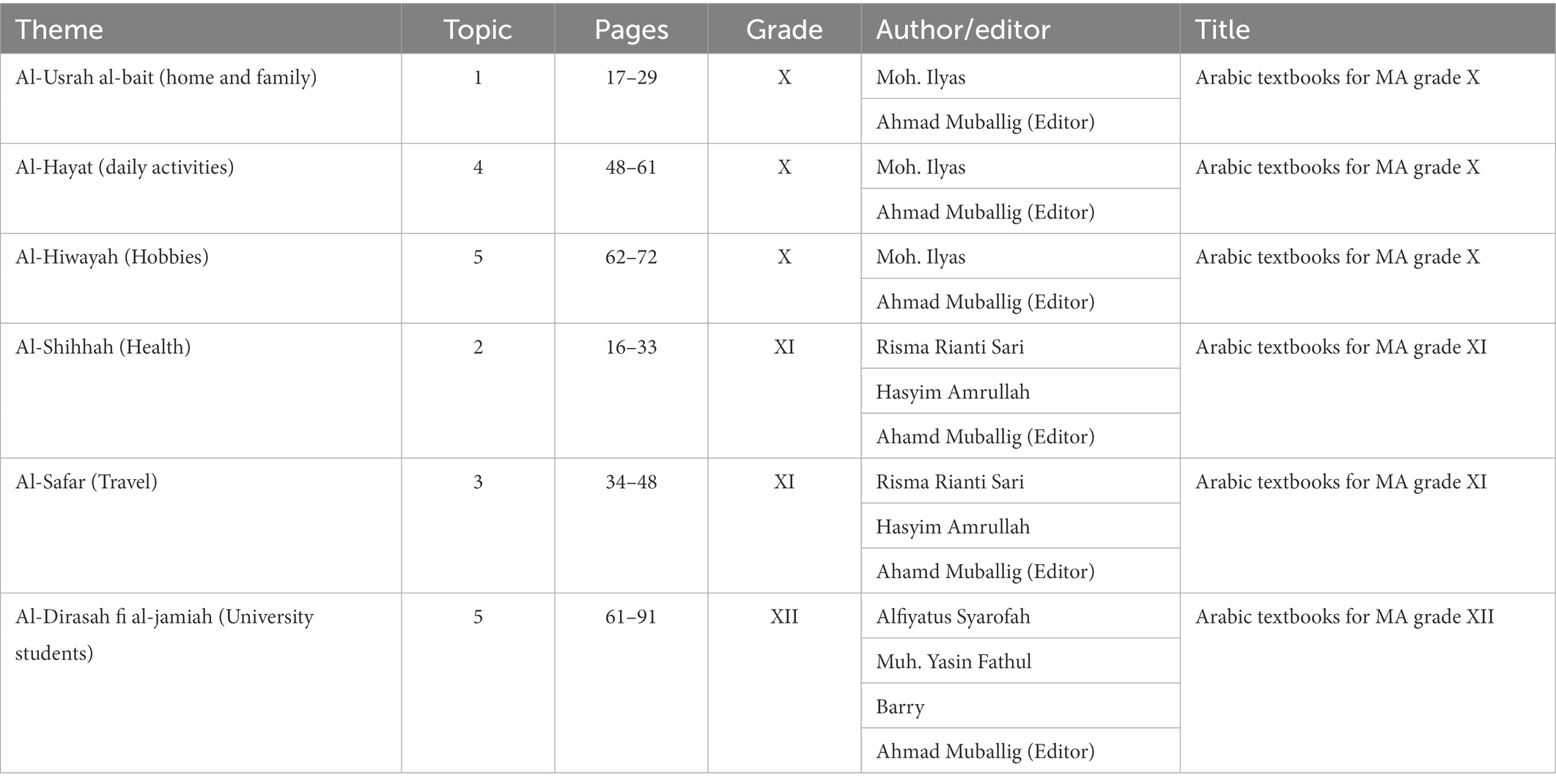

In this study, the researchers selected three Arabic textbooks from Islamic senior high schools (MA), mainly of grades X, XI, and XII, published by the Directorate General of Islamic Education, Ministry of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia. These textbooks were designed based on the 2013 curriculum and are the only books published and recommended by the Ministry of Religion of the Republic of Indonesia to be used in Islamic senior high schools. Additionally, Arabic teachers in Indonesia use other sources, such as handouts, materials from the Internet, and other books published by private publishers. However, we did not include those sources in this text analysis research because different additional sources may differ from one teacher to another. For the analysis, verbal and visual texts depicting gender bias and gender stereotyping were chosen. For verbal text analysis, we focused only on the exercises of six themes from the textbooks. The chapter and theme were preferred because they contained social contexts that showcased how specific gender was stereotypically portrayed. The theme chosen can be seen in Table 2.

Data analysis

We analyzed all visual components in our visual analysis based on the selected topics by adopting Rifkin’s (1998) framework for a critical evaluation of gender representations in visual and verbal texts. The visual framework consisted of three core concepts elaborated into seven sub-concepts. However, only four concepts were adopted in this study because not all criteria were applicable in the textbooks. The visual concepts selected were (1) pictures that only included women/men, (2) foregrounded pictures of women/men to backgrounded women/men, (3) pictures of boy/girl children, and (4) visual context, which could be identified as “domestic/professional.” Rifkin offered 14 indicators for verbal texts to measure gender representation in textbooks. However, the researchers only focus on three leading indicators: (1) the percentage of women and men as subjects in sentences, (2) the percentage of men and women as objects in sentences, and (3) the percentage of men and women as possessive in sentences. This consideration was decided because not all indicators offered in Rifkin’s theory were suitable for application to verbal data. If used as a whole, it could result in overlapping and repetitive data calculations. From the six themes (home and family, daily activities, hobbies, health, travel, and university students), researchers used the manual method of analyzing a textual representation of gender by conducting content analysis. Gender representation frequencies were counted to identify feminism and masculine pronouns. Afterward, the researchers compared the two characters. After a general quantitative analysis of gender representations was applied, the researchers conducted a discursive analysis emphasizing the visibility of gender bias and stereotyping.

Findings

RQ1: What was the percentage of gender (male and female) representation in government-endorsed Arabic language textbooks used in Indonesian Islamic senior high schools?

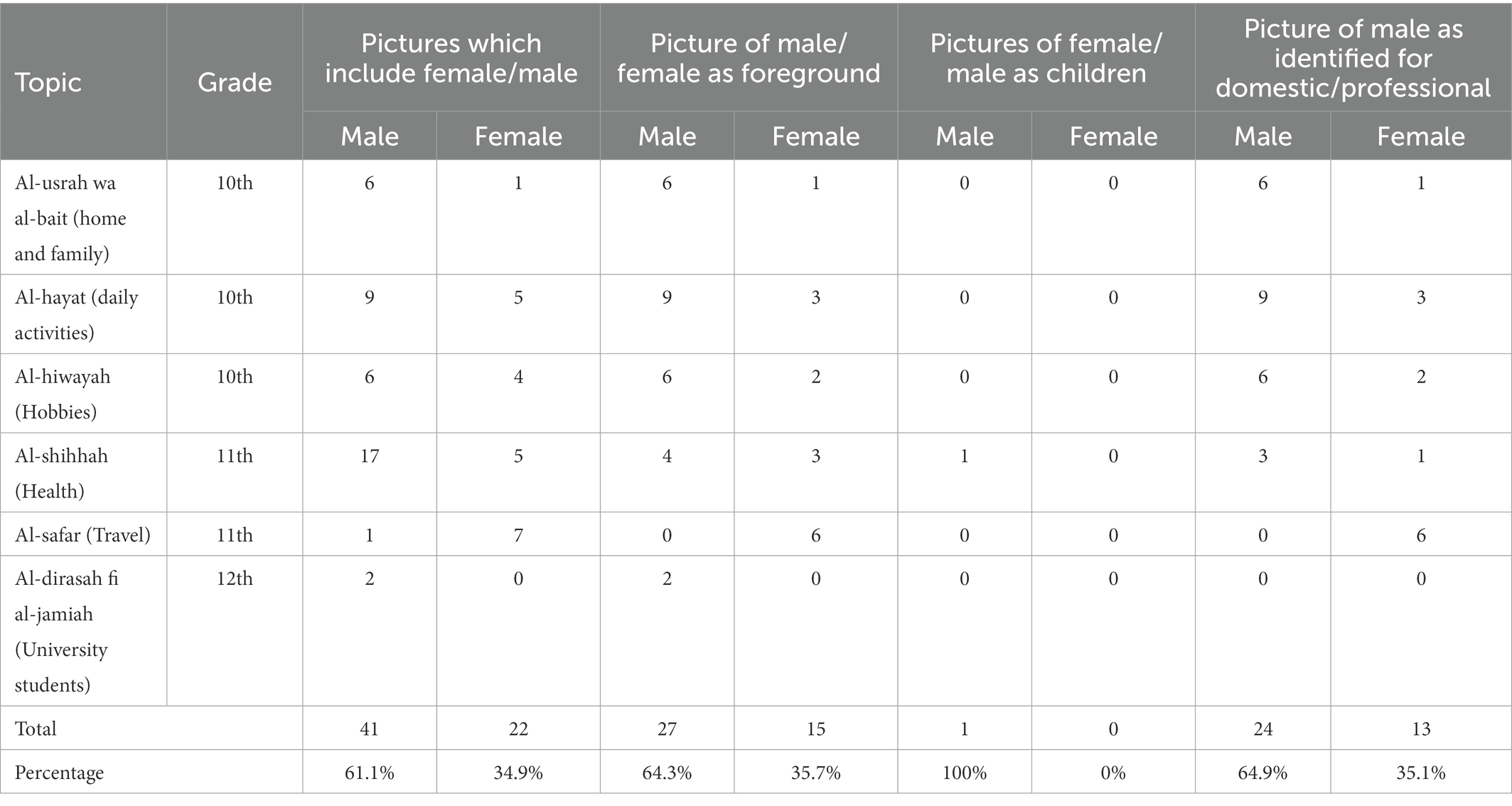

We counted pictures that portrayed men and women in four categories from Rifkin’s (1998) framework to find the different percentages of gender representation (male and female) in the Arabic language textbooks. Additionally, the verb representing men and women (subject pronoun, object pronoun, and possessive pronoun) was also accounted for in this exercise.

As shown in Table 3, female pictures had a smaller percentage than male pictures in all categories, which visually translated into gender imbalances in the three textbooks examined. The comparison between male and female pictures in all categories had a similar percentage—about 65% of men and 35% of women. Overall, the representation of men and women in the visual data was 93 men (65.03%) compared to 50 women (34.96%). Interestingly, the count based on the topics, except for the topic about travel, represents more male pictures than female ones. Male predominance in most roles was indicated by these results, except for traveling, in which females were predominant.

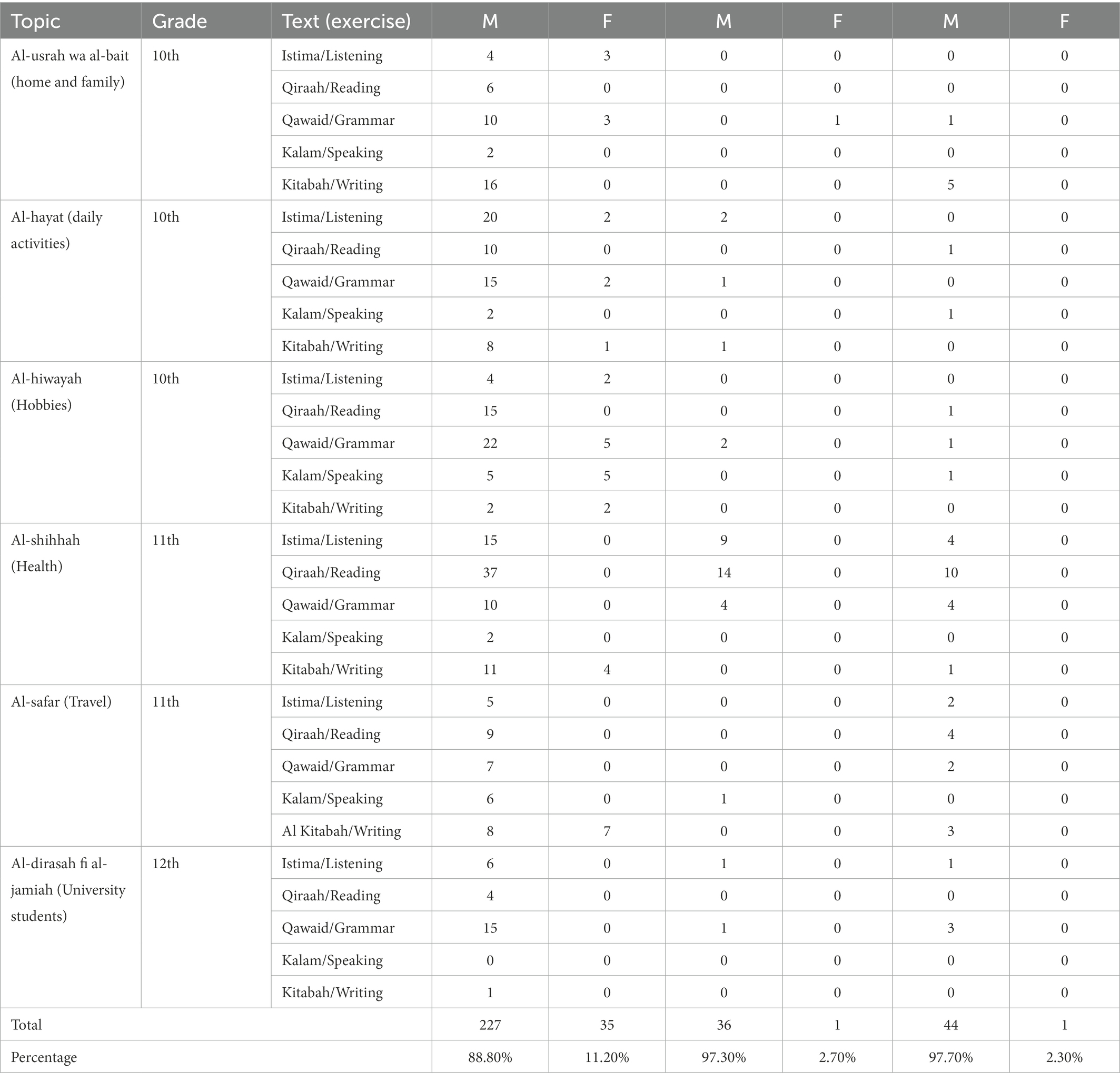

The frequencies of masculine and feminine representations from the textbooks based on text (exercise) focusing on listening (istima’), reading (qiraah), grammar (qawaid), speaking (al-kalam), and writing (al-kitabah) are shown in Table 4. Although the researchers only counted pronouns (subject, object, and possessive pronouns), the data showed significant differences between masculine and feminine representations in the textbooks in all aspects. The most significant numbers regarding gender representation were in the subject pronoun, with 277 (88.8%) male representations and 35 (11.2%) female representations. Of all skills, masculinity was mentioned predominantly, except in speaking skills on health and travel, where women were mentioned more frequently than men. Feminine object and possessive pronouns were only mentioned once, or 2.7% and 2.3%, respectively. The total male and female representations were 357 men (90.6%) compared with 37 women (9.39%). A significant difference in the three indicators studied was revealed by this verbal data, following Rifkin’s theory.

RQ2. In what ways are males and females presented and portrayed in these textbooks?

Government-endorsed Arabic textbooks for senior high schools verbally presented texts, conversations, and exercises. Each chapter was structurally arranged by listening, reading, grammar, speaking, and writing. Meanwhile, on the visual level, textbooks used more photographs than caricatures and cartoons. As shown below, visual gender representation was presented based on the selected theme.

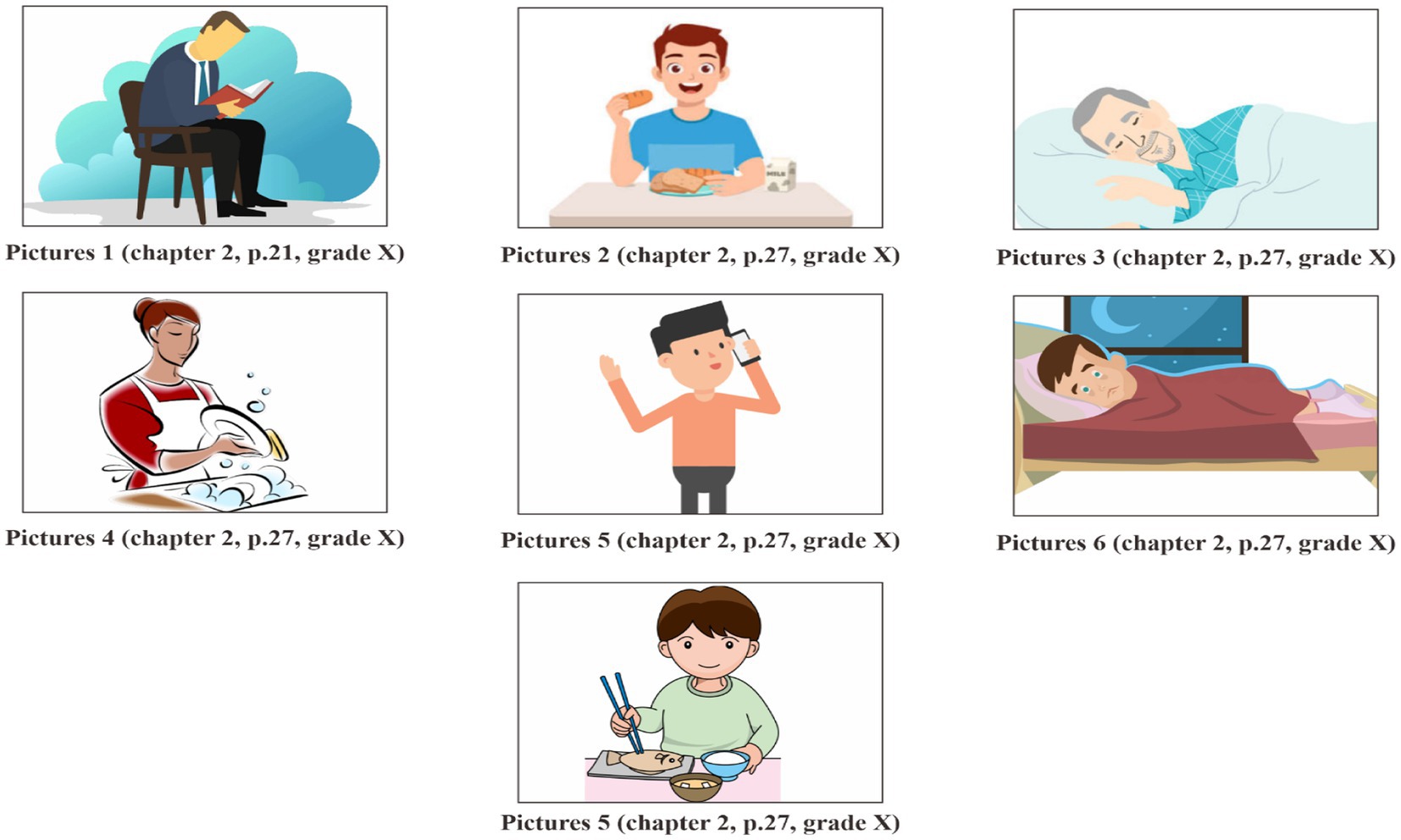

Portraying males and females in the theme of home and family life

The pictures about home and family can be found in Chapter Two, pages 17–29. The pictures on this topic have a robust male representation and appear to stereotype the female characters vividly. Inequality of gender representations can be seen on pages 21 and 27. On those pages, male pictures were presented more than female pictures. Six of the seven pictures were men and only one was a woman. In the family context, the female image was portrayed stereotypically. The woman was presented as a mother who worked domestically for her family (Figure 1, picture 4). Concurrently, men were shown in some activities, such as reading (Figure 1, picture 1), having breakfast and dinner (Figure 1, pictures 2 and 7), on the bed (Figure 1, pictures 3 and 6), and on the phone (Figure 1, picture 5).

Portraying men and women in the theme of daily activities

In the theme of daily activities, the authors of Arabic textbooks of senior high school grade X portrayed 13 photographs on pages 48 and 52. Six of the 13 pictures represented girls. However, female representation in the foreground was shown in only three pictures: female students and male students in the class (Figure 2, picture 10), a mother in the market (Figure 2, picture 4), and a female news anchor (Figure 2, picture 5). In the other three pictures, women were represented in the background. In 10 other images, outdoor activities that males strongly dominate were shown, such as practicing activities in the laboratory (Figure 2, picture 3), sports (Figure 2, picture 2), a journalist (Figure 2, picture 6), a doctor checking a patient (Figure 2, picture 7), an engineer (Figure 2, picture 8), cleaning services (Figure 2, picture 9), a scavenger (Figure 2, picture 10), a police officer (Figure 2, picture 11), a preacher (Figure 2, picture 12), and farmers (Figure 2, picture 13).

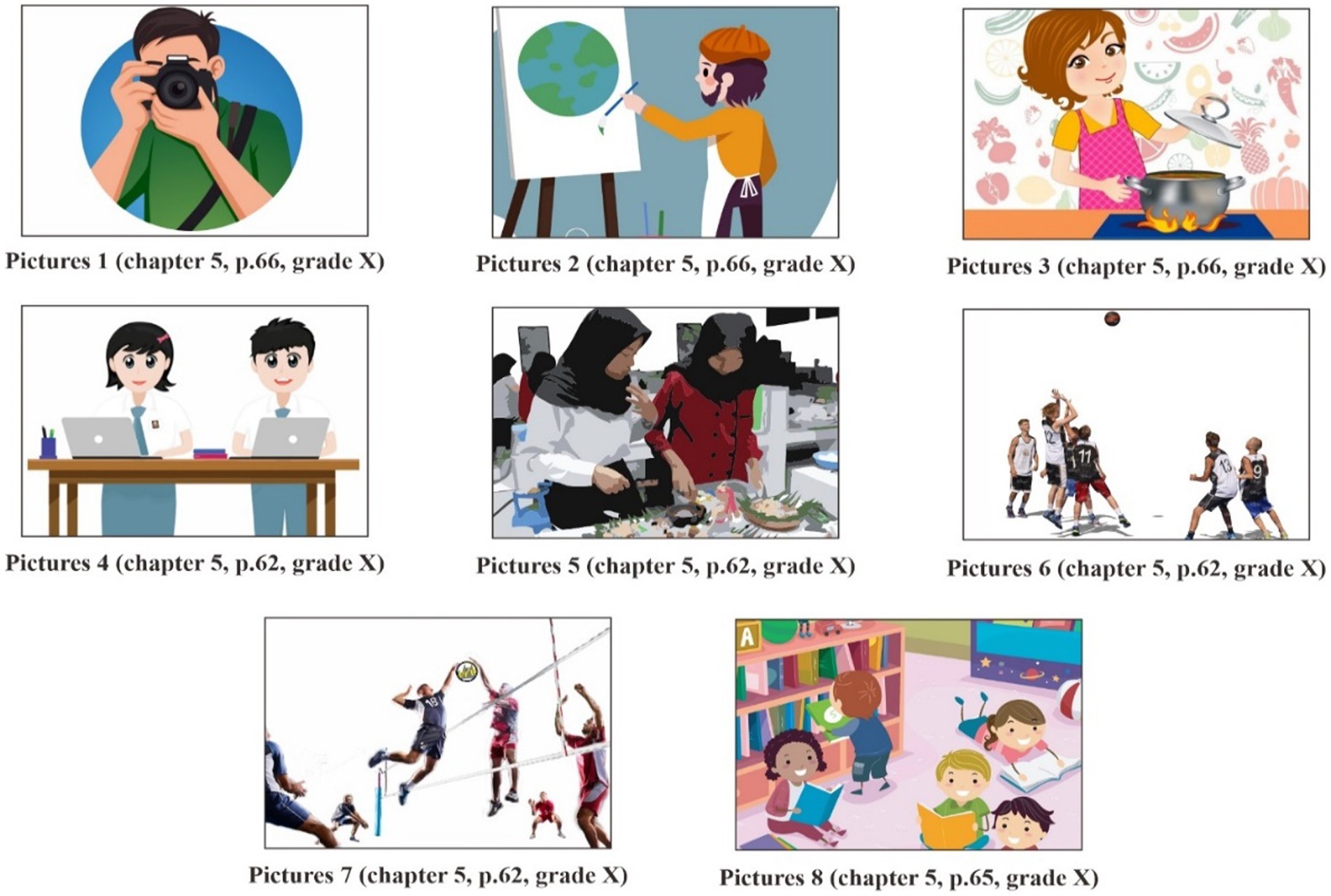

Portraying men and women in the theme of hobbies

The authors represented eight photographs on the topic of hobbies (pages 62–72). The hobbies shown were reading, photography, painting, sports, and cooking. Of all the pictures, only two represented women—pictures 3 and 5 (cooking activities). The other hobbies were represented by men, such as photography (Figure 3, picture 1), painting (Figure 3, picture 2), and sports (Figure 3, picture 7). There was one picture in which a woman and a man were shown in one frame: a picture of two students in the library. There seemed to be stereotyping of the female gender in the visual data.

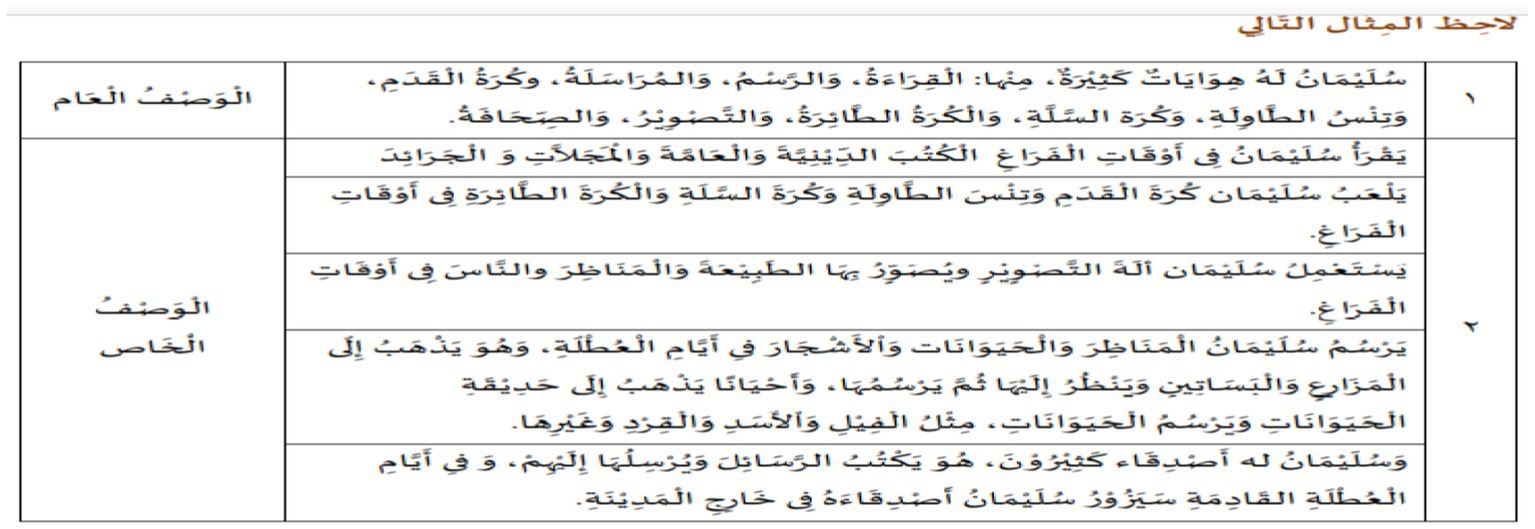

The visual data are supported by the verbal data on page 69, as shown below.

The male gender was strongly represented in the text in Figure 4. The character Sulaiman (a male student) had some hobbies, such as reading, painting, sports, and photography. Gender gaps and stereotyping appeared in this chapter because there was a picture featuring a female, but they were not described in the text. Many women have hobbies and can perform the same activities as in the picture. The marginalization and labeling of the female gender are shown in Figure 5 (pictures 3 and 5), where women are portrayed in cooking activities.

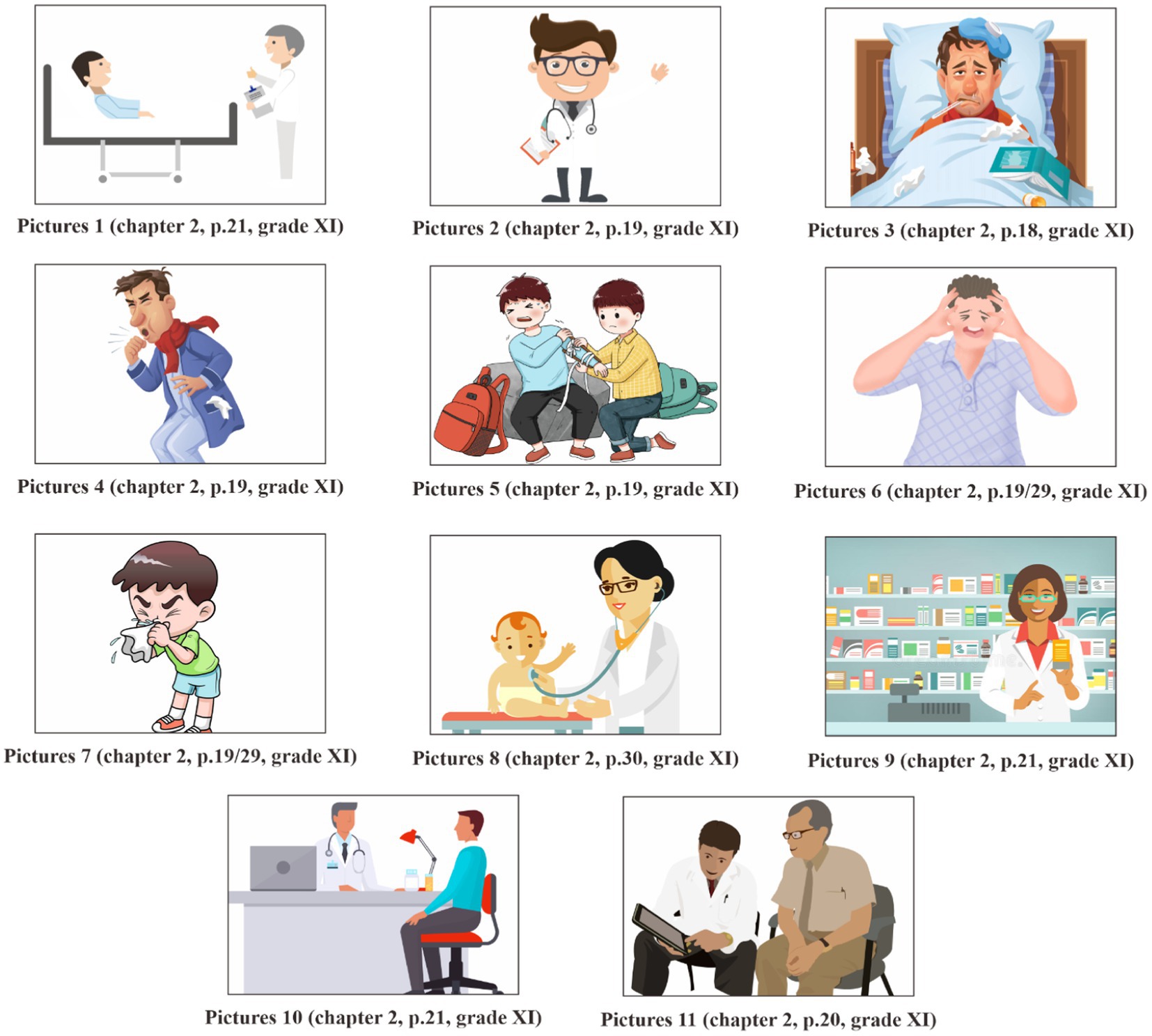

Portraying males and females in the theme of health

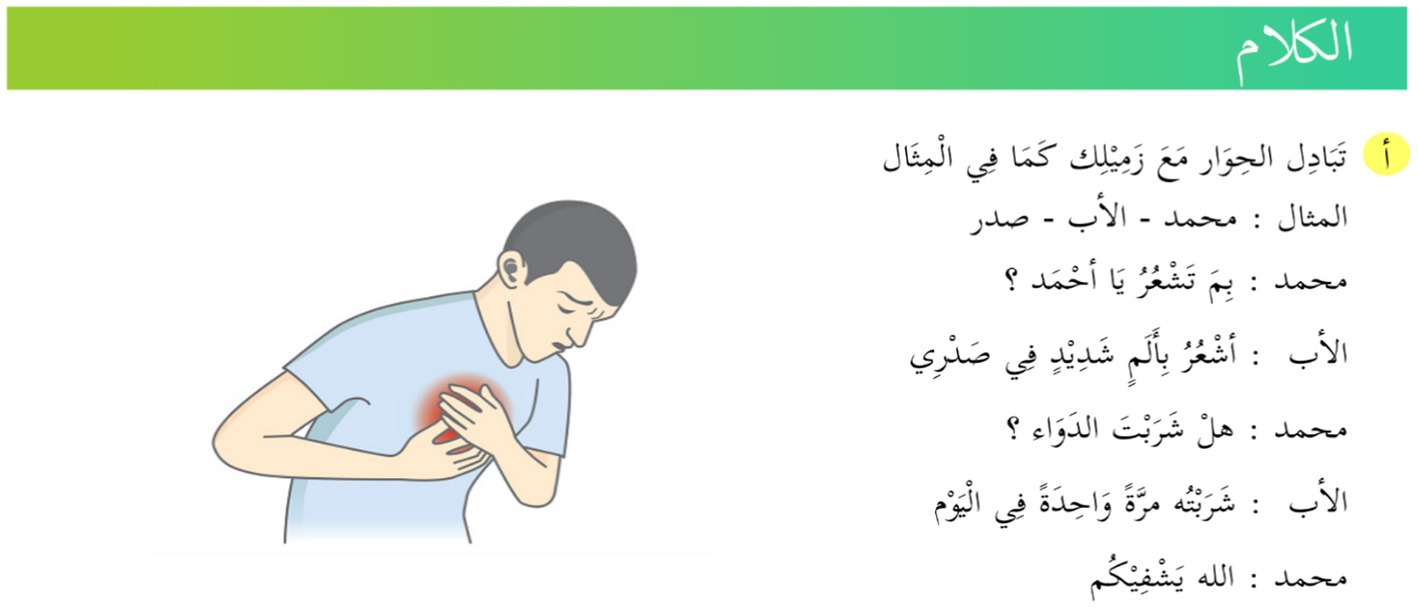

The topic of health consisted of 11 pictures. Nine pictures represented the male gender and two represented the female gender. Female characters are shown in Figure 5 (picture 8) as a pediatrician and a pharmacist (picture 9). In this topic, the authors presented women out of the domestic area; however, gender gaps still exist because of the imbalanced gender representation. The visual data is also supported by verbal data, as shown below.

The researcher showed the verbal data presented on the theme of health as follows, in which the alignment of the male gender is obvious to support the previous visual data (Figure 6).

The exercise above is about a conversation between a father and his son (Muhammad). Students were given a conversational practice with their peers. The content of the conversation was a father asking about the condition or health of his son. The characters of Muhammad and his father are one of several examples dominated by male representations. Even though there are several female figures in the picture, this data reinforces why there is more gender bias in verbal data than visual data.

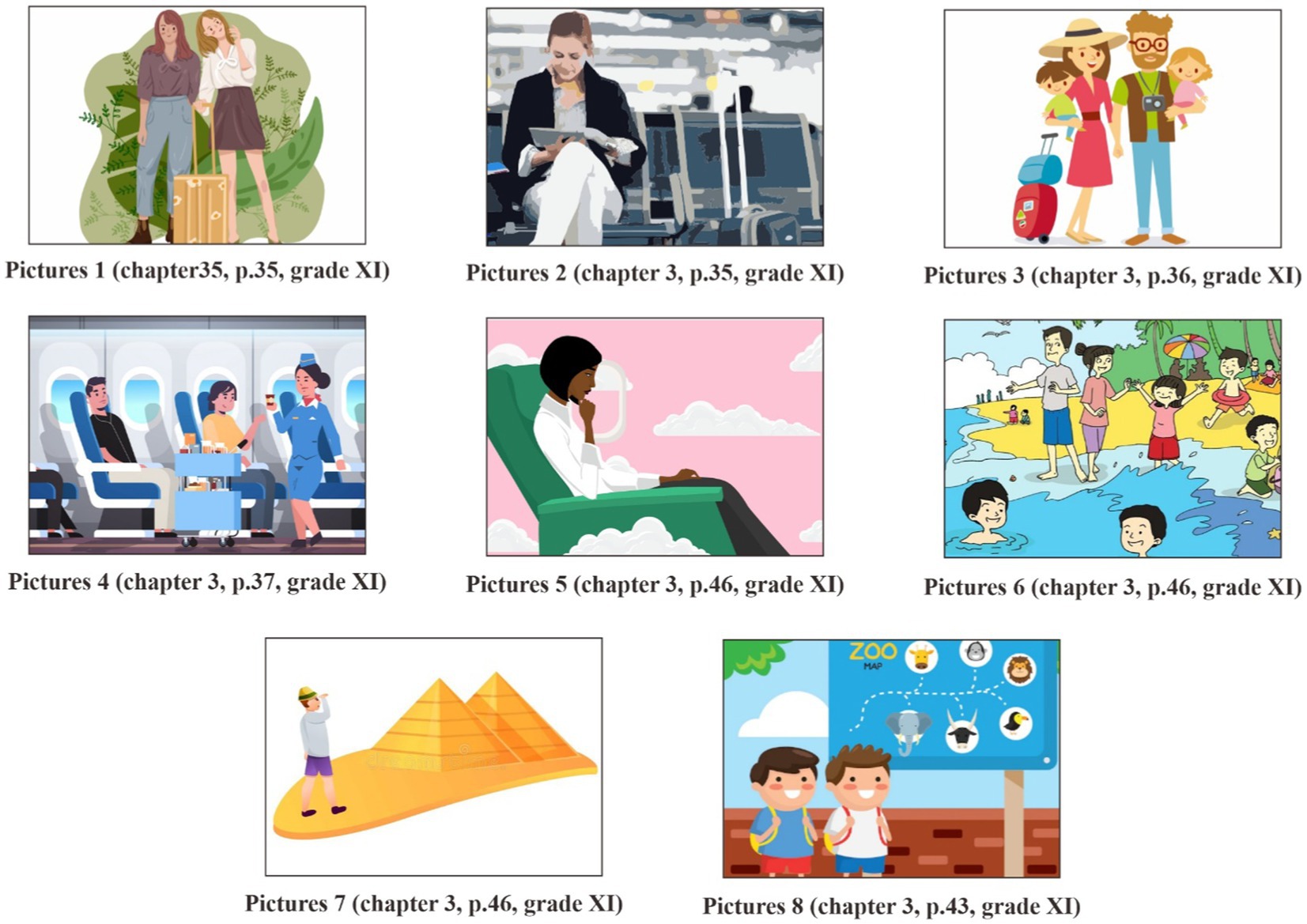

Portraying men and women in the theme of traveling (grade XI)

In this chapter, there are only seven pictures. Five pictures represented the female gender. Two women preparing for travel are shown in Figure 7, picture 1. In Figure 7, picture 2, a woman sitting in the waiting room is shown. In Figure 7, picture 3, a family, composed of a mother, a father, and their child, is shown. Figure 7, picture 4, has a female flight attendant speaking to a passenger. In Figure 7, picture 5, a woman sitting on a plane is shown. Meanwhile, a man and a woman on the beach are shown in Figure 7, picture 6. The male representation can be found in pictures 7 and 8 from Figure 7, where a man is visiting a pyramid (Figure 7, picture 7). Finally, two boys are visiting the zoo in Figure 7, picture 8.

Although women were visually represented in a strong manner in this chapter, verbally, the exercise texts over-represented the male gender. The male gender was expressed using a male name, such as Hasan (حسن). Still, it overwhelmed verbs indicating male, such as safara (سافر), which means to travel, zara (زار) or to visit, zahaba (ذهب) or to go, qadha (قضى) or to stay, and sya’ura (شعر) or to feel. The representation of the male gender can be seen in one example below (Figure 8).

Portraying boys and girls in the theme of studying at the university (grade XII)

The textbooks for the 12th grade had five themes. Only one of them was selected in this study (Chapter 5) because the other chapters had limited pictures. In Chapter 5, there were 14 pictures. However, only two human pictures represented gender. The first picture shows a male reading in the library and the second shows another male student in the laboratory. Although there were only two pictures, this theme still had an imbalanced gender representation. Overall, visual and verbal data on all topics over-represent the male at the expense of the female (Figure 9).

RQ3. What pedagogical actions may be taken to address gender inequalities in these textbooks?

The government-endorsed Arabic language textbook used in this research contains gender bias. Visual data show that male gender representations were 65% and female representations were 35%. Verbal data, which were examined from subject pronouns, object pronouns, and possessive pronouns, also had comparable results. Subject pronouns consisted of 88.8% of male representations and 11.2% of female representations. Meanwhile, the number of object pronouns was 97.7% of male representations and only 2.7% of female representations. Additionally, boys represented 97.7% of the possessive pronoun and girls only represented 2.3%. The gender imparity representations discussed what the Arabic teachers need to do in teaching Arabic using those books and what actions the government should undertake to address the gender issues in those textbooks.

Arabic teachers must develop materials when they decide to use the government-endorsed Arabic language textbook. They must explore the teaching material deeply by providing gender equality pictures or photographs, and teachers are encouraged not to follow the textbooks fully. Moreover, teachers must also provide example exercises and texts on gender, balancing between men and women as subjects, objects, and possessives in the sentences, because Arabic grammar is very gender friendly. This aims to achieve a comprehensive image of the understanding of the materials by students so that the message of gender equality is not neglected. Teachers need to apply these steps because the teaching and learning process in the class can change the attitudes of societies, cultures, and civilizations. Thus, teachers must be more creative, innovative, and adaptive in delivering teaching materials so that learning does not remain male-oriented. Furthermore, for the Ministry of Religious Affairs and government representatives to promote gender equality among students, they need to provide a professional and skilled team of teaching material compilers. Also, it is crucial to hire professional animators so that the picture in the produced books were not gendered biased and the books are qualified as quality standard textbooks.

Discussion

This study portrays that government-endorsed Arabic textbooks contain gender bias. This could be seen from the percentage of gender representation in Arabic textbooks verbally and visually, which tended to favor men over women in various themes, such as home and family, daily activities, hobbies, health, and university students, except for the travel theme, which was female. It was shown in many studies that the dominance of women in the traveling or tourism sectors was higher than men (Khan, 2011; Laing and Frost, 2017; Cichocki, 2019). Quantitatively, it was shown in empirical evidence that the number of female Muslim travelers increased to 63 million in 2018. Two-thirds of them were from Europe, America, Asia, and the Middle East (Oktadiana et al., 2020). Khan (2011) reported that men did not have much free time to travel because they tended to have more office work, while family responsibilities were relatively more limited than women. Still, nowadays, women cannot be labeled to compose the less busy gender regarding office work. They are doing much more office work, but still prioritizing traveling activities. Cichocki (2019) highlighted that women are more dominant in the traveling and tourism sectors because women excel more in interpersonal relationships than men. Therefore, they can become great negotiators in personal, business, office activities, and other transactions. Still, women might find themselves in double binds, for example, when they must utilize their interpersonal and relationship skills more than men (Mitten et al., 2018). This implies that domestic roles should not be labeled for women because women can interact and engage in outside activities.

The study also reveals that not only traveling but female students were also featured in five other themes in domestic activities, such as cooking. Even if activities are outside domestics, they are limited to specific occupations, such as news anchors and pediatricians. This condition is happening because the social construction of Indonesian culture associates gender with jobs (Lestariyana et al., 2020). News anchors and pediatricians are considered more suitable for women in Indonesia, while men are deemed fit for positions other than those occupations. In this case, the Arabic textbook authors seem unable to separate the identity of the domination of religious ideology from that of the profession. They are influenced by the fanaticism of traditional Islamic understanding, which emphasizes that women are second creatures. Women are complementary to men. Therefore, the activities that women perform are domestic. This implies that the authors of the Arabic textbook are also less aware of the grammatical characteristics of the Arabic language. This situation always balances males and females in several types of words, for example, in the form of pronouns, as shown in Table 5.

Additionally, textbooks that should be prepared purely for learning purposes are a new medium to indoctrinate conservative religious understanding and patriarchal culture that is still firmly rooted in textbook authors. This empirical evidence aligns with the study of Baghdadi and Rezaei (2015). They found that most of the gender bias in textbooks was caused by global cultural phenomena. In the UEA, patriarchy is still dominant and it influences the materials in textbooks. The same phenomenon is inevitable in Indonesia. The government-endorsed Arabic textbook used in Indonesia shows that planning and drafting did not consider gender equality since men dominate the authors and editors. Similarly, gender bias also appears in Arabic textbooks in Iran and Jordan (Otoom, 2014; Baghdadi and Rezaei, 2015; Al-Qatawneh and Al Rawashdeh, 2019). The results of the textbook research analysis in those countries showed that the parties involved in the curriculum and material designs paid less attention to the gender issues in the textbooks. This was because of the domination of customs, cultures, beliefs, and religious teachings that men must be more eminent than women.

Furthermore, a tradition that always preluded men before woman seems entrenched. Moreover, in their study, Salami and Ghajarieh (2016) indicated that gender stereotypes were in line with the efforts of authorities to maintain the status quo in Iranian society. Similarly, the authors of the textbooks seem affected by classical Islamic doctrine that lies in the segregation between men and women by bringing up the roles of men in the public sector and women in the domestic sector. From a cultural perspective, women were always positioned as housewives and the second gender (Eagly and Sczesny, 2019). Stereotype implications presented in the government mandate that Arabic textbooks used in Indonesia may cause emotional fragilities that support male supremacy and female inferiority. Otoom (2014) suggested raising the image of women in the curriculum and textbooks and enacting them as major methodological issues that need to be considered because the curriculum and textbook contents affect the visualizations of students about their roles in their future lives. Young generations are substantially prepared by school curricula to embody philosophy, values, and principles in their societies. Besides, teachers are expected to express their views about cultural ideas that should be promoted in the textbooks (Salami and Ghajarieh, 2016).

In addition, male gender bias was more represented verbally and visually in the material presented. The visual data were 93 men (65.03%) compared to 50 women (34.96%). Regarding verbal text data, there were 357 men (90.6%) compared with 37 women (9.39%). The unbalanced visual and verbal data were analyzed using Rifkin’s theory. The study results showed that the theory could not be applied to Arabic texts. The indicator items offered had unclear specifications, thus, the collected data overlapped. One of the indicators was “the ratio of all females to male characters” (Rifkin, 1998, p.235). For example, Fatimah Yusuf indicates that Fatimah is Yusuf’s daughter. In Arabic, the name used is Fatima, not Miss Yusuf, as explained by Rifkin. When using the name Miss Yusuf, it is confusing when using pronouns in sentences because the word Miss indicates female, while the word Yusuf indicates a male. In the case of Arabic texts, these pronouns must be precise because Arabic grammar shows firmness. At the same time, it acknowledges and appreciates the existence of each gender. Ignoring this fact indicates that the government is not concerned with fulfilling gender equality in textbooks before publication. In contrast, the slogan of gender equality is continually echoed by the Ministry of Religion of the Republic of Indonesia. Similarly, the author of the book neglects to use the characteristics of the Arabic language, pro-gender equality, to transfer the value of gender equity.

This study suggests the need to implement gender mainstreaming in textbooks by using measurable indicators. Textbook authors are advised to adopt a rotation strategy to mention male and female genders in the text to accommodate the concept of gender equality so that gender bias in textbooks can be minimized. The Ministry of Religion, as a country representative, needs to monitor the preparation of Arabic textbooks that risk gender bias misperceptions. Arabic is an accommodative language for gender equality, which can be shown by the availability of various forms of words for men and women. This step must be taken to avoid gender bias and misperceptions of Islamic teachings. Thus, this empirical research implies that pedagogical actions that can be applied to solve this problem are as follows. First, Arabic teachers must develop materials when they decide to use the government-endorsed Arabic language textbook. Second, government representatives in the Ministry of Religious Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia should promote gender equality among students.

Conclusion

The present study has analyzed gender representation in the three government-endorsed Arabic textbooks for Islamic-based schools in Indonesia. It is essential to mention that only verbal and visual texts representing gender were examined. This empirical evidence attempts to administer a comprehensive understanding of gender stereotypes in social contexts such as home and family, daily activities, hobbies, health, traveling, and students in a university. This shows that although women were visible in verbal and visual texts in the three endorsed textbooks (Grades X, XI, and XII), they were still conventionally stereotyped as domestic workers. Women are also stereotyped as travelers, home workers, and pediatricians.

Furthermore, the textbook writers exposed their little awareness of gender equality. As a result, gendered stereotypes remain in textbooks. Based on the empirical investigation, it was implied that curriculum and textbook designers should be mindful of gender stereotyping to perform gender equality roles in Arabic textbooks. It is recommended that textbook writers refrain from gender bias or stereotyping in Arabic textbooks because they teach about language areas and morals, such as gender (ness). However, it is unquestionable that gender inequality cannot be removed because this gender issue is part of a global cultural phenomenon. In other words, gender representation is socioculturally regulated, given that women and men have impartial opportunities to play distinct roles appointed by their community and society.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SK and FG contributed to the conceptual framework and wrote the article. AA and FF contributed to the methodological section. MU and SA translated, proofread, and wrote the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Agni, Z. A., Setyaningsih, E., and Sarosa, T. (2020). Examining gender representation in an Indonesian EFL textbook. Regist. J. 13, 183–207. doi: 10.18326/rgt.v13i1.183-207

Al-Qatawneh, S., and Al Rawashdeh, A. (2019). Gender representation in the Arabic language textbook for the ninth grade approved by the Ministry of Education for use in schools in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Stud. Educ. Eval. 60, 90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.12.001

Ariyanto, S. (2018). A portrait of gender bias in the prescribed Indonesian ELT textbook for junior high school students. Sex. Cult. 22, 1054–1076. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2012.669394

Atchison, A. L. (2017). Where are the women? An analysis of gender mainstreaming in introductory political science textbooks. J. Political Sci. Educ. 13, 185–199. doi: 10.1080/15512169.2017.1279549

Baghdadi, M., and Rezaei, A. (2015). Gender representation in English and Arabic foreign language textbooks in Iran: a comparative approach. J. Int. Women's Stud. 16, 16–32. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol16/iss3/2/

Bandura, A. (2003). Bandura’s social cognitive theory: an introduction. San Luis Obispo, CA: Davidson Films, Inc. http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/1641092

Carlson, M., and Kanci, T. (2017). The nationalised and gendered citizen in a global world–examples from textbooks, policy and steering documents in Turkey and Sweden. Gend. Educ. 29, 313–331. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1143917

Cichocki, M. K. (2019). “Women’s travel patterns in a suburban development,” in New Space for Women (1980). 1st Edn. eds. G. R. Wekerle, R. Peterson, and D. Morley (Routledge), 151–163. doi: 10.4324/9780429048999

Cobano-Delgado, V. C., and Llorent-Bedmar, V. (2019). “Identity and gender in childhood. Representation of Moroccan women in textbooks,” in Women’s Studies International Forum. Vol. 74 (Pergamon), 137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2019.03.011

Damayanti, I. L. (2014). Gender construction in visual images in textbooks for primary school students. Indones. J. Appl. Ling. 3, 100–116. doi: 10.17509/ijal.v8i3.15270

Dunne, M., Humphreys, S., and Leach, F. (2006). Gender violence in schools in the developing world. Gend. Educ. 18, 75–98. doi: 10.1080/09540250500195143

Eagly, A. H., and Sczesny, S. (2019). Gender roles in the future? Theoretical foundations and future research directions. Front. Psychol. 10:1965. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01965

Foroutan, Y. (2012). Gender representation in school textbooks in Iran: the place of languages. Curr. Sociol. 60, 771–787. doi: 10.1177/0011392112459744

Ganguli, I., Hausmann, R., and Viarengo, M. (2014). Closing the gender gap in education: what is the state of gaps in labour force participation for women, wives, and mothers? Int. Labour Rev. 153, 173–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2014.00007.x

Gebregeorgis, M. Y. (2016). Gender construction through textbooks: the case of an Ethiopian primary school English textbook. Afr. Educ. Rev. 13, 119–140. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2016.1224579

Khan, S. (2011). Gendered leisure: are women more constrained in travel for leisure? Tourismos 6, 105–121. doi: 10.26215/tourismos.v6i1.198

Kochuthara, S. G. (2011). Patriarchy and sexual roles. J. Dharma 36, 435–452. Available at: https://philpapers.org/rec/KOCPAS

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. California: Sage publications.

Laing, J. H., and Frost, W. (2017). Journeys of well-being: women’s travel narratives of transformation and self-discovery in Italy. Tour. Manag. 62, 110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.004

Lee, J. F. (2018). Gender representation in Japanese EFL textbooks–a corpus study. Gend. Educ. 30, 379–395. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2016.1214690

Lee, J. F. (2019). In the pursuit of a gender-equal society: do Japanese EFL textbooks play a role? J. Gend. Stud. 28, 204–217. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2018.1423956

Lestariyana, R. P. D., Widodo, H. P., and Sulistiyo, U. (2020). Female representation in government-endorsed English language textbooks used in Indonesian junior high schools. Sex. Cult. 24. doi: 10.1007/s12119-018-9512-8

Lopez-Zafra, E., and Garcia-Retamero, R. (2012). Do gender stereotypes change? The dynamic of gender stereotypes in Spain. J. Gend. Stud. 21, 169–183. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2012.661580

Mas’udah, S. (2020). Resistance of women victims of domestic violence in dual-career family: a case from Indonesian society. J. Fam. Stud. 1–18. doi: 10.1080/13229400.2020.1852952

Mitten, D., Gray, T., Allen-Craig, S., Loeffler, T. A., and Carpenter, C. (2018). The invisibility cloak: women’s contributions to outdoor and environmental education. J. Environ. Educ. 49, 318–327. doi: 10.1080/00958964.2017.1366890

Namatende-Sakwa, L. (2018). The construction of gender in Ugandan English textbooks: a focus on gendered discourses. Pedagogy Cult. Soc. 26, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2018.1436583

Namatende-Sakwa, L. (2019). Networked texts: discourse, power, and gender neutrality in Ugandan physics textbooks. Gend. Educ. 31, 362–376. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2018.1543858

Oktadiana, H., Pearce, P. L., and Li, J. (2020). Let’s travel: voices from the millennial female Muslim travelers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 22, 551–563. doi: 10.1002/jtr.2355

Otoom, K. A. S. (2014). The image of women in the Arabic language textbook for the primary second grade in Jordan. Eur. Sci. J. 10, 283–294. doi: 10.19044/esj.2014.v10n7p%25p

Pakuła, Ł., Pawelczyk, J., and Sunderland, J. (2015). Gender and sexuality in English language education: focus on Poland. London: British Council.

Poerwandari, E. K. (1999). The other side of history: Women’s issues during the national struggle of Indonesia, 1928–1965. Paper presented at the 7th international interdisciplinary congress on women. Tromso, Norway.

Porter, M. (2001). Women in “Reformasi”: aspects of women’s activism in Jakarta. Can. J. Dev. Stud./Rev. canadienne d’études du développement 22, 51–80. doi: 10.1080/02255189.2001.9668802

Reeves, J. B. (1987). Work and family roles: contemporary women in Indonesia. Sociological Spectr. 7, 223–242. doi: 10.1080/02732173.1987.9981820

Rifkin, B. (1998). Gender representation in foreign language textbooks: a case study of textbooks of Russian. Mod. Lang. J. 82, 217–236. doi: 10.2307/329210

Risager, K. (2018). Representations of the world in language textbooks. London: Multilingual Matters.

Romera, M. (2015). The transmission of gender stereotypes in the discourse of public educational spaces. Discourse Soc. 26, 205–229. doi: 10.1177/0957926514556203

Salami, A., and Ghajarieh, A. (2016). Culture and gender representation in Iranian school textbooks. Sex. Cult. 20, 69–84. doi: 10.1007/s12119-015-9310-5

Setyono, B. (2018). The portrayal of women in nationally endorsed English as a foreign language (EFL) textbook for senior high school students in Indonesia. Sex. Cult. 22, 1077–1093. doi: 10.24176/pro.v2i1.2989

Stromquist, N. P. (1998). The institutionalization of gender and its impact on educational policy. Comp. Edu. 34, 85–100. doi: 10.1080/03050069828360

Sulaimani, A. (2017). Gender representation in EFL textbooks in Saudi Arabia: a fair deal? Engl. Lang. Teach. 10, 44–52. doi: 10.5539/elt.v10n6p44

Sunderland, J. (2000). Issues of language and gender in second and foreign language education Lang. Teac. 33, 203–223.

Syairofi, A., Mujahid, Z., Mustofa, M., Ubaidillah, M. F., and Namaziandost, E. (2022). “Emancipating SLA findings to inform EFL textbooks: a look at Indonesian school English textbooks,” in The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 1–12. Online First.

Ullah, H., and Skelton, C. (2013). Gender representation in the public sector schools’ textbooks of Pakistan. Educ. Stud. 39, 183–194. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2012.702892

Vu, M. T., and Pham, T. T. T. (2021). Still in the shadow of Confucianism? Gender bias in contemporary English textbooks in Vietnam. Pedagogy Culture Soc. 1-21. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2021.1924239

Widodo, H. P. (2018). “A critical micro-semiotic analysis of values depicted in the Indonesian ministry of national education-endorsed secondary school English textbook” in Situating moral and cultural values in ELT materials: The southeast Asian context. eds. H. P. Widodo, M. R. G. Perfecto, L. V. Canh, and A. Buripakdi (Cham: Springer), 131–152.

Keywords: Arabic language, gender equality, gender representation, textbooks, stereotypes

Citation: Kuraedah S, Gunawan F, Alam S, Ubaidillah MF, Alimin A and Fitriyani F (2023) Gender representation in government-endorsed Arabic language textbooks: Insights from Indonesia. Front. Educ. 7:1022998. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1022998

Edited by:

Margaret Grogan, Chapman University, United StatesReviewed by:

Hanita Ismail, National University of Malaysia, MalaysiaAiril Haimi Mohd Adnan, MARA University of Technology, Malaysia

Copyright © 2023 Kuraedah, Gunawan, Alam, Ubaidillah, Alimin and Fitriyani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fahmi Gunawan, ✉ Zmd1bmF3YW5AaWFpbmtlbmRhcmkuYWMuaWQ=

St Kuraedah1

St Kuraedah1 Fahmi Gunawan

Fahmi Gunawan M. Faruq Ubaidillah

M. Faruq Ubaidillah