94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 06 October 2022

Sec. Teacher Education

Volume 7 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.1015163

Jaber S. Alqahtani1*

Jaber S. Alqahtani1* Abdulelah M. Aldhahir2

Abdulelah M. Aldhahir2 Shouq S. Al Ghamdi3

Shouq S. Al Ghamdi3 Ahmad M. Aldakhil4

Ahmad M. Aldakhil4 Hajed M. Al-Otaibi5

Hajed M. Al-Otaibi5 Saad M. AlRabeeah1

Saad M. AlRabeeah1 Eman M. Alzahrani6

Eman M. Alzahrani6 Salah H. Elsafi7

Salah H. Elsafi7 Abdullah S. Alqahtani1

Abdullah S. Alqahtani1 Thekra N. Al-maqati7

Thekra N. Al-maqati7 Musallam Alnasser1

Musallam Alnasser1 Yaser A. Alnaam7

Yaser A. Alnaam7 Eidan M. Alzahrani8

Eidan M. Alzahrani8 Hassan Alwafi9

Hassan Alwafi9 Wafi Almotairi10

Wafi Almotairi10 Tope Oyelade11

Tope Oyelade11Background: The COVID-19 pandemic and associated preventative measures introduced a shock to the teaching paradigm in Saudi Arabia and the world. While many studies have documented the challenges and perceptions of students during the COVID-19 pandemic, less attention has been given to higher education staff. The aim of the present investigation is to evaluate the staff’s perception and experiences of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods: A validated survey was conducted between December 2021 and June 2022 in Saudi Arabian Universities to assess the status of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic among faculty members. The collected responses were exploratively and statistically analyzed.

Results: A total of 1117 response was received. About 66% of the respondents were male and 90% of them hold postgraduate degree. Although rarely or occasionally teach online pre-COVID-19, only 33% of the respondents think the transition was difficult and 55% of them support the move. Most respondents received adequate training (68%) and tools (80%) and 88% of the respondents mentioned that they did not accrue additional workload in online study design. While the perception of online teaching was mostly positive (62%) with high satisfaction (71%). However, 25% of the respondents reported that a poor internet bandwidth was an obstacle and 20% was unable to track students’ engagement. Respondents with more years of experience, previous training, support, or perceived online transition as easy were also more likely to be satisfied with the process. Also, older respondents, those who support the transition and those with previous training were less likely to report barriers (all p < 0.001).

Conclusion: The perception and experience of transition to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia were positive. Low internet bandwidth and inability to track students’ limited effective online teaching. Work experience, previous training, and positive perception are the main factors that influence staff online teaching satisfaction.

The COVID-19 pandemic remains one of the major public health emergencies in the last century resulting in over 500 million confirmed infections and over six million deaths globally (Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021; World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). The pressure on healthcare systems around the world due to the rapid spread resulted in various measures and a hurried search for effective vaccines and therapies (Nuevo-Chow, 2021). To reduce the spread and corresponding healthcare pressure, governments around the world implemented various measures including national lockdown and social restrictions resulting in the closure of various industries and institutions with resulting economic and welfare issues (Nuevo-Chow, 2021; Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). One sector especially affected is educational institutions which faced an unprecedented challenge of sustaining learning while ensuring the safety of students and staff members, thus moving to an online mode of teaching delivery (Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020; Nuevo-Chow, 2021). Indeed, around 1.6 billion educators and learners around the world were affected and had to adapt quickly to a different modes of teaching and learning, respectively (Adedoyin and Soykan, 2020; Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021).

The Education in Emergency (EiE) initiative was introduced by the united nations children fund (UNICEF) to ensure global access to safe and quality education during the global lockdown by aiding mostly developing countries in transition to accommodate the disruption of traditional learning paradigm (Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). In incredible fits of innovation, various platforms and corridors were developed to accommodate disruptions and provide uninterrupted access to training modules and material (Lepp et al., 2021; Pokhrel and Chhetri, 2021). However, learners were especially faced with various challenges which are well documented in the literature (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Hassounah et al., 2020; Khalil et al., 2020). One aspect that escaped scrutiny is the challenges faced by teachers and staff members supporting teaching with little to no comprehensive study documenting the various challenges faced during the lockdown when they had to adapt rapidly to moving teachings online.

Transitioning to online teaching mode exposed teachers to different including poor access to the required technology, internet connections, and increased workload from redesigning training modules suited for online delivery. In essence, most staff members were conceivably unprepared and untrained for the swift shift in delivery mode (Lepp et al., 2021). Further, the inability to effectively track students’ engagement in an online learning environment (Aldhafeeri and Alotaibi, 2022), or deliver modules that are experimentally based are major challenges that have been reported (Cuschieri and Calleja Agius, 2020). A study by Rapanta et al. (2020), involving teachers from Switzerland, Australia, Spain, and Canada, reported challenges to include increased workload and inadequate technology. Hassan et al. (2020) findings corroborated this by reporting that around 50% of teachers reported transitioning to online teaching as “very difficult” due also to poor internet bandwidth and inadequate equipment. Similar challenges have been reported in Saudi Arabia and seem to be global (Alqurshi, 2020; Aldakheel, 2021).

Indeed, reports of positive aspects of online teaching are available. For instance, various studies have reported that online learning allowed prior, repeated, and unlimited access to educational materials and recorded lessons, improving satisfaction and outcomes (Agormedah et al., 2020; İilmaz Ince et al., 2020). Indeed, post lockdown, many institutions continue to employ some of the innovative and positive techniques used during the lockdown where suitable. Thus, while the transition to online teaching could not be avoided, improving on the positive aspects, and mitigating the negative perception is a balance that may help in future pandemics.

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced various challenges to physical teaching due to measures implemented to curtail the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 including movement and gathering restrictions and national lockdowns around the world. Indeed, to keep the educational sector running educational institutions around the world had to restrict teachings to remote/online only. Thus, while the use of online teaching in higher education is not new, it was the first time that all teachings were delivered fully online. This resulted in various limitations which is well documented especially in low- and middle-income countries where preparations were not especially adequate for managing the magnitude of the task. For instance, studies have aptly described challenges faced by faculty members in delivering teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in China (Tsegay et al., 2022), India (Hassan et al., 2020), Indonesia (Hermanto and Srimulyani, 2021), Pakistan (Akram et al., 2021; Aslam et al., 2021), and among English as Foreign Language learners in Saudi Arabia (Mahyoob, 2020) to mention but a few. These challenges affected all subjects of teaching and cut across all levels of learning including primary and secondary schools (Parveen et al., 2022) and is mainly exemplified by inadequate technical training or equipment exacerbated by poor internet bandwidth (Noor et al., 2020; Gurung, 2021). These challenges have been well studied and comprehensively discussed in literature (Parveen et al., 2022; Tang, 2022).

Although the challenges of online teaching due to the COVID-19 lockdown in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is well documented for students (Al-Nofaie, 2020; Hassounah et al., 2020; Khalil et al., 2020), the challenges faced by teachers and staff members that support the rapid movement of all teaching online has not received due attention especially in the KSA. Thus, we present here the perception, expectations, and challenges of higher education institution teachers and staff that support moving teaching online during the COVID-19 lockdown. The aim is to provide a platform for improved experience in future pandemics and stimulate discussion around the topic in Saudi Arabia and around the world.

Between December 5th, 2021, and June 5th, 2022, a cross-sectional survey was performed online using (Survey Monkey) platform.

The survey is composed of four sections including demographics data, experience and perceptions of online teaching before COVID-19, current practices and tools, expectations, satisfaction, and barriers to online teaching during COVID-19. A panel of experts in the fields of education collaborated to develop the framework, define, and verify it based on the available data from the literature. Survey content and face validity were conducted by the panel of experts and have been piloted with 15 faculty experts who have expertise in teaching in higher education before its first dissemination.

There were four parts to the two-page survey, each with a set of multiple-choice questions. Part one collected demographic data from respondents, such as regions, gender, age, academic qualification, specialty, years of teaching experience, size of the student cohort, and type of institution. Part two included three questions concerning experience and perceptions regarding online teaching before COVID-19 pandemic. Part three consisted of 13 questions regarding current practices and tools of online teaching during COVID-19. The last part asked three questions about the faculty’s expectations, satisfaction, and barriers to online teaching during COVID-19. Using the Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient, we observed that the instrument’s internal consistency was 0.84.

A convenience sampling technique was used to recruit the study participants from different specialties. The major areas of specialization: Professions and applied sciences, Formal sciences, Humanities and social sciences, and natural sciences from major universities and colleges in Saudi Arabia were included. Professional networks and different social media platforms (Twitter, LinkedIn, WhatsApp) were used to distribute and promote the survey to reach a larger number of educators and faculty members.

Based on the latest statistical summary of teaching staff by ministry of education in KSA (General Authority for Statistics, 2022), there was a total of 76,599 university teaching staff in the KSA. Thus, with a confidence interval of 95%, a margin of error of 3%, and assuming a response rate of 50%, the minimum sample size will be 1,053, which would allow a national representative sample.

This research was approved by Institutional Review Board from Prince Sultan Military College of Health Sciences, reference number (IRB-2022-RC-004).

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences was used to gather and analyze data (SPSS software, Version 28). The categorical variables were provided in percentages and frequencies. The Chi-square test was employed to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between categorical variables. We did logistic regression to determine the predictors for satisfaction and barriers to online teaching during COVID-19. If the p < 0.05, statistical significance was considered.

A total of 1,117 participants were recruited. The male represents 66% of the total sample. Almost 35% of the participants were between the ages of 41–50. A total of 533 (48%) and 473 (42%) hold a doctorate and master’s degree, respectively, and mostly specialized in applied and formal sciences. Almost 47% of the respondents have 10 or more years of working experience. Overall, only about 11% of respondents teach classes of over 100 students and most respondents teach in government/public educational institutions. Table 1 presents the demographic and characteristics of the participants.

Before COVID-19, approximately (360) 32% of the participants rarely used online platforms for teaching, with only 294 (26%) frequent users. Regarding the overall perception of moving to teach online, most of the respondents 413 (37%) perceived this transition as an easy process, while 345 (32%) found it difficult to move to online teaching. A total of 609 (54%) supported the move to online teaching with only 198 (18%) of the respondents opposed to the process. Table 2 presents the experience and perceptions of the participants regarding the online teaching before COVID-19 pandemic.

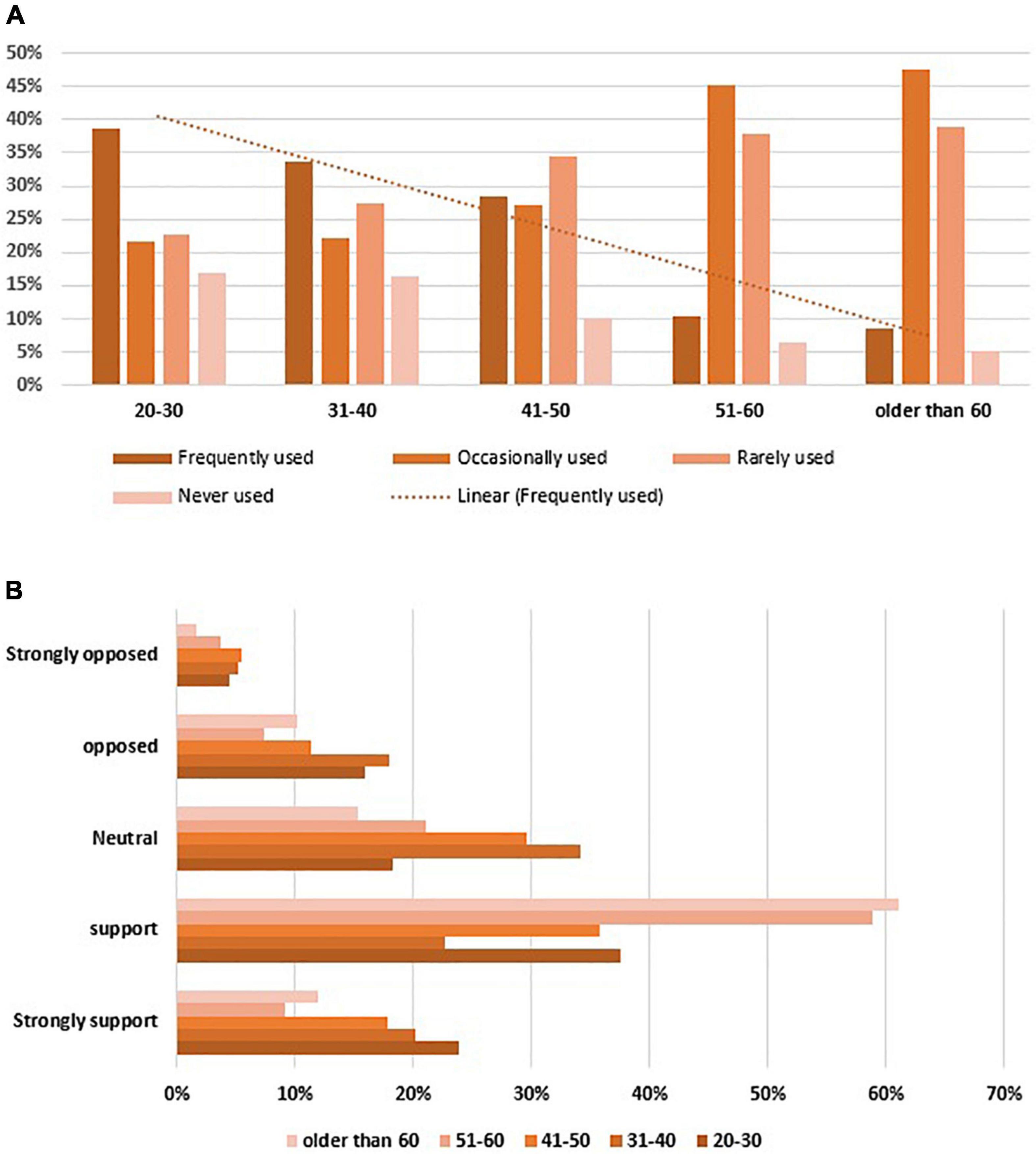

As expected prior experience of online teaching and age groups showed a statistically significant difference (p-value < 0.001) whereby younger teachers used online platforms for teaching more frequently before COVID-19. However, there was a significant difference in the overall perception of moving teaching online between age groups, where older staff supported moving teachings online more strongly than younger staff (p-value < 0.001). Figure 1A illustrate the use of online teaching before COVID-19 among the age groups, while Figure 1B illustrate the use of online teaching before COVID-19 stratified by the age and the willingness of moving teaching online.

Figure 1. Use of online teaching before COVID-19 stratified by age (A) and the willingness of moving teaching online stratified by age (B).

About 80% of respondents indicated that they were provided relevant tools for online teaching with 20% indicating otherwise. A total of 67.5% of staff members stated that they received adequate training for online teaching; online courses represents 43% of the training mode. The Blackboard was the most popular online teaching platform. This was reported by 52% of the respondents while it was used in combination with Zoom by 34.5% of respondents.

A total of 61% of the respondents spent less the 2 h on average preparing for a single online session, while only 8% of the respondents spent more than 4 h preparing. Further, 47% of respondents spent the same time needed for a face-to-face class, with teaching materials more likely distributed within a week of online classes on 71% of occasions. Table 3 presents the current practices and tools of online teaching during COVID-19.

A combination of assignments, quizzes, and examinations was frequently used as an evaluation method for the online teaching classes by 469 (42%) respondents. The most-reported evaluation instrument for an online class was Blackboard (77%), and Google forms (17.5%).

A total of 52.5% of the respondents deliver teaching that involve practical skills. To maintain continuum during the lockdown, 69% of the respondents distributed practical teaching materials by post while 31% of the respondents requiring students to collect them from campus. Evaluation for practical skills was mainly performed via live and recorded presentation on 35% of the occasions.

The expectations of moving to online teaching due to COVID-19 lockdown was generally positive among 62% of the respondents while 30% of them were uncertain whether moving online will be effective. Indeed, 71% of respondents were satisfied with the process for transitioning to online teaching. Regarding the limitations, 25% of the respondents cited poor internet strength (bandwidth) as the main barrier to effective online teaching during COVID-19 lockdown followed by the inability to track students’ engagement on 20% of the occasions. Childcare and family responsibilities was also reported as a main barrier with 9% of respondents. Table 4 presents the expectations, satisfaction, and barriers of online teaching during COVID-19.

Logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between satisfaction and age, experience, perception, and training. Age, experience, and training were positively and significantly correlated with satisfaction. Indicating older age, more experienced and adequately trained staffs are more satisfied with transitioning to online teaching. On the other hand, responders who perceived moving teaching online as difficult and those who opposed moving teaching online were less satisfied. Table 5 presents the multivariable logistic regression analysis of predictors for satisfaction and barriers.

The relationship between observed barriers and age or willingness to support moving teaching online and training are also presented. Age and training were negatively associated with barriers. Furthermore, people who were opposed moving to online teaching were more likely to have more barriers. Figure 2 illustrates the main barriers for online teaching by age groups.

The current data presents the perception, attitude, challenges, and satisfaction of 1,117 educators with online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic. Our results show that training and experience in online teaching are crucial factors that influence the perceptions of online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although, most educators supported the move to online teaching and were mostly positive in terms of perception, various challenges such as poor internet bandwidth, the limited ability to follow up or track students’ engagements, and family commitments were highlighted as barriers to effective online teaching delivery during the national lockdown. These obstacles persisted even though relevant teaching tools and training were provided. Our findings align with a previous study from India that assessed the challenges of online teaching and learning during COVID-19 which found that the main barriers were lack of technical skills and low internet bandwidth (Hassan et al., 2020).

The frequency of using the online teaching platforms before the COVID-19 pandemic is a major driver of perception and observed barriers. Indeed, a significant difference in the online teaching experience before the pandemic has been reported worldwide (Bolliger and Halupa, 2022). A previous report assessed teachers’ prior engagement in online teaching has shown that 67% of faculty members had frequently used online teaching platforms before the SAR-CoV-2 pandemic (Jaschik and Lederman, 2019). This is comparatively higher compared to 26% observed in the present study. This lack of preparedness or prior exposure to an online teaching environment is a major limitation, especially in developing countries where educational resources are not as abundant. The sudden nature of the transitioning to online teaching did not help either, resulting in a significant shock to educational paradigm and equilibrium (Brooks and Grajek, 2020).

Most of our respondents perceived the transition to online education as an easy process with mostly positive expectations and satisfaction and mostly supported the transition. This indicates that respondents thought that moving teachings online was a useful step to avoid interruption to learning during the COVID-19 lockdown despite the various challenges. A previous study on the perception of online teaching of teaching staff and students reported similar findings where although respondents perceived that online teaching could not achieve a similar learning experience offered via face-to-face teaching, it was a useful tool giving the global COVID-19 pandemic circumstance (Rajab et al., 2020; Almahasees et al., 2021).

Our data show that older staff faced less challenges, but age was not a predictor of satisfaction with online teaching in the multivariable analysis. However, staff who had more prior training, years of experience, positive perceptions, and supported transitioning to online teaching were more likely to be generally satisfied with the process. Also, older respondents were more supportive of the transition to online teaching. We hypothesize that this may be due to the general belief and acceptance that online teaching is a better alternative than no teaching at all and the understanding that teaching had to be moved online to avoid SARS-CoV-2 infection and associated risk of hospitalization and mortality which is especially higher in older adults (Mesas et al., 2020). Indeed, the fear of COVID-19 is a well-researched topic that has been strongly linked with compliance and perception of COVID-19 preventative measures globally (Demirtaş-Madran, 2021; Håkansson and Claesdotter, 2022; Melki et al., 2022).

Expectedly, younger respondents were more likely to have used online teaching platforms more frequently before the COVID-19 pandemic. Our result is in line with previous studies where age was reported as a major factor associated with increased digital teaching skills (Cruz and Díaz, 2016; Mirķe et al., 2019). Although, Elliott et al. (2015) reported increased workload due to more time needed to prepare online teaching materials, our results show otherwise with only 12% of respondents reporting spending relatively more time preparing for online teaching than they would need for face-to-face teaching. This is intuitive as online learning standards for higher education in the KSA were built according to the best standards that include the provision of cutting-edge technology, training and support, and accessibility (Al Zahrani et al., 2021). However, the current system has a room for improvement which could improve students’ and staff’s perception and experience as well as the effectiveness of online teaching.

Our study further highlights the need to integrate technological training and retraining into the continued professional development of teachers to improve competence in the use of online teaching platforms in the KSA and around the world (Hassan et al., 2020). This is crucial not only in preparation for future pandemic but as teaching-learning technologies continues to advance globally. It seems that post-COVID-19, online teaching will remain an integral part of future education delivery, and continued assessments will be needed to bring to fore the various challenges to both teachers and students in this ever-evolving field. Decision-makers should focus on improving teachers’ technological skills to improve online learning outcomes and readiness for future events.

Importantly, the challenges faced by faculty members regarding moving teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic is not unique to KSA alone. Indeed, while the level of each challenge may vary depending on the level of infrastructures available in countries, most countries had similar limitations resulting in subpar movement of teaching fully online. For instance, Akram et al. (2021) in a case study of public studies in the Pakistan state of Karachi reported lack of experience, inadequate equipment and technical support as the main barriers to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. This report was also corroborated in a review by Aslam et al. (2021) on the readiness of Pakistan for online teaching and learning during COVID-19 pandemic. The cross-sectional design of this study and recall bias of respondents are the main limitations. However, the relatively higher sample size provides a strong collective perspective that is reflective of the study population. In general, our finding builds on previous work on the topic and pushes the case for improved information and communication technological (ICT) training as part of continued professional development (CPD) of teaching staffs as well as provision of adequate equipment and support. This will provide adequate learning environment and serve as buffer against any future disruption to learning in educational institutions in KSA and globally.

In summary, although limited by poor internet bandwidth and low technological skills, the perception and experience of transition to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia were positive. Low internet bandwidth and inability to track students limited the delivery of effective online teaching. More experienced staffs and those who receive adequate training are more likely to be satisfied with the transition to online teaching.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board from Prince Sultan Military College of Health Sciences, reference number (IRB-2022-RC-004). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JA and TO contributed to the study conception and design. JA, ShA, and TO helped to prepare the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the methodology section including data collection and analysis, revised the manuscript, read, and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adedoyin, O. B., and Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interact. Learn. Environ. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Agormedah, E. K., Henaku, E. A., Ayite, D. M. K., and Ansah, E. A. (2020). Online learning in higher education during COVID-19 pandemic: a case of Ghana. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 3, 183–210. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00332-1

Akram, H., Aslam, S., Saleem, A., and Parveen, K. (2021). The challenges of online teaching in COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of public universities in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Inform. Technol. Educ. Res. 20:263.

Al Zahrani, E. M., Al Naam, Y. A., AlRabeeah, S. M., Aldossary, D. N., Al-Jamea, L. H., Woodman, A., et al. (2021). E-Learning experience of the medical profession’s college students during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 21:443. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02860-z

Aldakheel, M. (2021). An Exploration of the Technological, Technological-Pedagogical, and Technological and Instructional Challenges that Saudi Faculty Face in Their Transition to Online Education. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Aldhafeeri, F. M., and Alotaibi, A. A. (2022). Effectiveness of digital education shifting model on high school students’ engagement. Educ. Inform. Technol. 27, 6869–6891. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10879-4

Almahasees, Z., Mohsen, K., and Amin, M. O. (eds) (2021). Faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:638470. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.638470

Al-Nofaie, H. (2020). Saudi University Students’ perceptions towards virtual education During Covid-19 PANDEMIC: a case study of language learning via Blackboard. Arab World Eng. J. 11, 4–20.

Alqurshi, A. (2020). Investigating the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on pharmaceutical education in Saudi Arabia–A call for a remote teaching contingency strategy. Saudi Pharm. J. 28, 1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2020.07.008

Aslam, S., Saleem, A., Akram, H., Parveen, K., and Hali, A. (2021). The challenges of teaching and learning in the COVID-19 pandemic: the readiness of Pakistan. Acad. Lett. 2, 1–6.

Bolliger, D. U., and Halupa, C. (2022). An investigation of instructors’ online teaching readiness. TechTrends 66, 185–195.

Brooks, C., and Grajek, S. (2020). Faculty Readiness to Begin Fully Remote Teaching. Utrecht: EDUCAUSE.

Cruz, F. J. F., and Díaz, M. J. F. (2016). Generation z’s teachers and their digital skills. Comun. Media Educ. Res. J. 24:46.

Cuschieri, S., and Calleja Agius, J. (2020). Spotlight on the shift to remote anatomical teaching during Covid-19 pandemic: perspectives and experiences from the University of Malta. Anatom. Sci. Educ. 13, 671–679. doi: 10.1002/ase.2020

Demirtaş-Madran, H. A. (2021). Accepting restrictions and compliance with recommended preventive behaviors for COVID-19: a discussion based on the key approaches and current research on fear appeals. Front. Psychol. 12:558437. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.558437

Elliott, M., Rhoades, N., Jackson, C. M., and Mandernach, B. J. (2015). Professional development: designing initiatives to meet the needs of online faculty. J. Educ. Online 12:n1. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003061

General Authority for Statistics (2022). Statistical Summary of Teaching Staff. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en (accessed April 20, 2022).

Gurung, S. (2021). Challenges faced by teachers in online teaching during Covid-19 pandemic. Online J. Distanc. Educ. eLearn. 9, 8–18.

Håkansson, A., and Claesdotter, E. (2022). Fear of COVID-19, compliance with recommendations against virus transmission, and attitudes towards vaccination in Sweden. Heliyon 8:e08699. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e08699

Hassan, M. M., Mirza, T., and Hussain, M. W. (2020). A critical review by teachers on the online teaching-learning during the COVID-19. Int. J. Educ. Manag. Eng. 10, 17–27.

Hassounah, M., Raheel, H., and Alhefzi, M. (2020). Digital response during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Internet Res. 22:e19338.

Hermanto, Y. B., and Srimulyani, V. A. (2021). The challenges of online learning during the covid-19 pandemic. J. Pendidikan Dan Pengajaran 54, 46–57.

Jaschik, S., and Lederman, D. (2019). The 2019 Inside Higher ed Survey of Faculty Attitudes on Technology, a Study by Inside Higher ed and Gallup. Utrecht: Mediasite.

Khalil, R., Mansour, A. E., Fadda, W. A., Almisnid, K., Aldamegh, M., Al-Nafeesah, A., et al. (2020). The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Med. Educ. 20:285. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z

Lepp, L., Aaviku, T., Leijen, Ä, Pedaste, M., and Saks, K. (2021). Teaching during COVID-19: the decisions made in teaching. Educ. Sci. 11:47.

Mahyoob, M. (2020). Challenges of e-Learning during the COVID-19 pandemic experienced by EFL learners. Arab World Eng. J. 11, 351–362.

Melki, J., Tamim, H., Hadid, D., Farhat, S., Makki, M., Ghandour, L., et al. (2022). Media exposure and health behavior during pandemics: the mediating effect of perceived knowledge and fear on compliance with COVID-19 prevention measures. Health Commun. 37, 586–596. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1858564

Mesas, A. E., Cavero-Redondo, I., Álvarez-Bueno, C., Sarriá Cabrera, M. A., Maffei de Andrade, S., Sequí-Dominguez, I., et al. (2020). Predictors of in-hospital COVID-19 mortality: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis exploring differences by age, sex and health conditions. PLoS One 15:e0241742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241742

Mirķe, E., Cakula, S., and Tzivian, L. (2019). Measuring teachers-as-learners’ digital skills and readiness to study online for successful e-learning experience. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 21, 5–16.

Noor, S., Isa, F. M., and Mazhar, F. F. (2020). Online teaching practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Process Int. J. 9, 169–184.

Nuevo-Chow, L. (2021). Higher Education and Strategic Leadership during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Phenomenological Study of Deans in the 21 st Century. La Verne, CA: University of La Verne.

Parveen, K., Tran, P. Q. B., Alghamdi, A. A., Namaziandost, E., Aslam, S., and Xiaowei, T. (2022). Identifying the leadership challenges of K-12 public schools during COVID-19 disruption: a systematic literature review. Front. Psychol. 13:875646. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875646

Pokhrel, S., and Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. High. Educ. Future 8, 133–141.

Rajab, M. H., Gazal, A. M., and Alkattan, K. (2020). Challenges to online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus 12:e8966.

Rapanta, C., Botturi, L., Goodyear, P., Guàrdia, L., and Koole, M. (2020). Online university teaching during and after the Covid-19 crisis: refocusing teacher presence and learning activity. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2, 923–945.

Tang, K. H. D. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on primary, secondary and tertiary education: a comprehensive review and recommendations for educational practices. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. [Epub ahead of print].

Tsegay, S. M., Ashraf, M. A., Perveen, S., and Zegergish, M. Z. (2022). Online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic: teachers’ experiences from a Chinese university. Sustainability 14:568.

World Health Organization [WHO] (2021). COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update, Edition 56, 7 September 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Keywords: teaching, online teacher and learning processes, COVID, Saudi Arabia, education

Citation: Alqahtani JS, Aldhahir AM, Al Ghamdi SS, Aldakhil AM, Al-Otaibi HM, AlRabeeah SM, Alzahrani EM, Elsafi SH, Alqahtani AS, Al-maqati TN, Alnasser M, Alnaam YA, Alzahrani EM, Alwafi H, Almotairi W and Oyelade T (2022) Teaching faculty perceptions, attitudes, challenges, and satisfaction of online teaching during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A national survey. Front. Educ. 7:1015163. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1015163

Received: 09 August 2022; Accepted: 20 September 2022;

Published: 06 October 2022.

Edited by:

Michelle Diane Young, Loyola Marymount University, United StatesReviewed by:

Pinaki Chakraborty, Netaji Subhas University of Technology, IndiaCopyright © 2022 Alqahtani, Aldhahir, Al Ghamdi, Aldakhil, Al-Otaibi, AlRabeeah, Alzahrani, Elsafi, Alqahtani, Al-maqati, Alnasser, Alnaam, Alzahrani, Alwafi, Almotairi and Oyelade. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jaber S. Alqahtani, QWxxYWh0YW5pLUphYmVyQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.