- South African Research Chair in Education and Care in Childhood, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

This study examined pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education. A total of 131 pre-service teachers from two programs—one at a College of Education and a university program through the Faculty of Education—were surveyed using a cross-sectional survey research design. Data were collected using a self-developed questionnaire. The questionnaire was pilot tested among pre-service teachers from the Faculty of Education at a university which did not participate in the study. We used a 3 × 2 factorial multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to analyze the descriptive and inferential data (means, standard deviations). The study revealed a statistically significant difference between pre-service teachers’ gender (male and female) and programs (university and college of education) regarding their knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education. The results indicated a significant MANOVA. In the follow-up analysis of the variance test, pre-service teachers’ perceptions and attitudes differed between genders and programs. In addition, the study found a significant difference between pre-service teachers’ perceptions and attitudes toward inclusive education based on their educational programs. Pre-service teachers from the College of Education scored higher than those from the Faculty of Education at a university. We discuss the implications of an egalitarian learning environment.

Introduction

Inclusive education has emerged as a benchmark for education communities that prioritize equality of opportunity and non-discrimination to reach as many students as possible regardless of their characteristics or needs. “Inclusion” is closely related to social justice campaigns, human rights movements, and equality-related movements (Adigun, 2021). According to Cushner et al. (2012), inclusive education is the practice of integrating students with special needs into regular classrooms. In other words, inclusive education aims to fulfill many of the same goals that encourage students with disabilities to be independent and to benefit from educational resources, practices, and activities for all.

The successful implementation of inclusive education depends on the organization and resources in the learning situation, educational content and management style, and the availability of qualified teachers. There is a lack of confidence among pre-service teachers in being able to teach both regular learners and learners with special needs. In addition to the increased workloads of teachers, the arguments against inclusive education are remain focused on the teachers’ lack of skills (YLE, 2019). It appears that attitudes toward inclusion are becoming more hostile, highlighting the importance of research like the present one which examines the potential impact of the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of pre-service teachers. Based on cross-sectional studies (Savolainen et al., 2012), teacher efficacy may influence teacher attitudes significantly. Comparative studies demonstrate that the relationship between teacher efficacy and teacher attitudes is as strong in Finland (Yada et al., 2018) as anywhere else (Savolainen et al., 2012).

Teachers’ attitudes, perceptions, beliefs, and humanity toward students with disabilities are crucial to implementing inclusive education because they can hinder or facilitate the integration, learning, and participation processes. Teachers’ perceptions and attitudes depend on a variety of factors, including qualifications, experience, teaching experience, and their impacts can determine whether an inclusive process will succeed or fail (Suriá, 2012; Granada et al., 2013; Castro et al., 2016). Moreover, a key component of inclusion is the Salamanca Framework for Action (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 1994; Adigun, 2021), which is incorporated into several African educational policy documents and provides guidance on how pre-service teachers can improve the educational process and outcomes for learners with disabilities. In its National Policy on Education, the Federal Republic of Nigeria (2004) defined inclusive education through this framework.

Regardless of their linguistic, emotional, cognitive, or physical condition, these documents stipulate that all learners receive equal treatment. Interestingly, the Nigerian Policy on Education specifies that all learners should have equal access to quality education by integrating learners with disabilities into regular classrooms free of discrimination (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2004). Challenging objectives are outlined in various policy documents on the provision of quality education to learners with disabilities.

Researchers have extensively studied the attitudes of teachers toward inclusion (Jerlinder et al., 2010; de Boer et al., 2011). Furthermore, Avramidis and Norwich (2002) noted that different studies have been conducted on teachers’ perceptions of inclusion in education and the factors that might influence their acceptance of this. Teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion were positive, but full acceptance was not evident. How teachers responded to students’ needs was directly influenced by any learning institution’s ability to offer inclusive education (Suriá, 2012). Solis et al. (2019) noted that promoting and maintaining an inclusive educational setting was influenced by the knowledge and attitudes educators had toward individuals with disabilities, affecting the outcome of the inclusion process (Broomhead, 2019; Florian, 2019).

This study is important because it intended to investigate pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education based on their gender (male and female) and program (Bachelor’s Degree in Education and Nigerian Certificate in Education). The research questions for the study were:

1. Is there significant difference between pre-service teachers’ gender (male and female) and programs [Bachelor’s Degree in Education (B.Ed.) and Nigerian Certificate in Education (NCE)] in terms of their knowledge of inclusive education.

2. What is the significant difference between pre-service teachers’ gender (male and female) and programs (Bachelor’s Degree in Education and Nigerian Certificate in Education) in terms of their perception of inclusive education.

3. Is there a significant difference between pre-service teachers’ gender (male and female) and programs (Bachelor’s Degree in Education and Nigerian Certificate in Education) in terms of their attitude toward inclusive education.

Literature review

Teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education

The effectiveness of inclusive educational practices depends on the knowledge and understanding teachers have of the processes involved (Osisanya et al., 2015). According to Baguisa and Ang-Manaig (2019), pre-service teachers are relatively unaware of inclusive education. The knowledge base of teachers has also been criticized in other studies. According to AlMahdi and Bukamal (2019), 17.4% of candidates for teaching jobs in the Bay District of the Philippines were unaware of inclusive education policies, while other candidates only had a moderate understanding of them. It is well-documented that teacher training on disabilities suffers from major shortcomings (Arias et al., 2013; Alnasser, 2020) because of false beliefs and prejudices that stigmatize pupils with disabilities. Inclusive processes that are carried out correctly are determined by the prevailing attitude of the community in which they occur (Pérez-Jorge, 2010; Suriá, 2012; Sorkos and Hajisoteriou, 2020). It has been reported that Nigerian teachers have limited knowledge of inclusive education (Timothy et al., 2014).

A study conducted by Wanjiru (2017) found that Kenyan teachers lacked knowledge of what was required to engage them in driving and reaching inclusion goals. Pre-service teachers may not fully grasp the concept of inclusive education, a practice designed to accommodate all learners irrespective of their differences in learning (Rouse, 2010; Dapudong, 2013; Wanjiru, 2017). In many pre-service teacher education programs, the introduction to inclusive education is the only subject related to inclusive education (Carroll et al., 2003). Studies have shown that introductory inclusive education courses can positively influence pre-service teachers’ attitudes and confidence (Campbell et al., 2003; Loreman and Earle, 2007; Sharma et al., 2008). Carroll et al. (2003) and Lancaster and Bain (2007) discovered that participation in short compulsory courses dealing with inclusive education increases discomfort, sympathy, uncertainty, fear, coping, and confidence levels.

The inability to establish inclusive schools has not been unexpected. Teachers with some experience and higher education in teaching students with disabilities and those with more training showed significantly more support for inclusive education, indicating that a lack of preparation contributes to resistance to this practice (Mngo and Mngo, 2018). Some experts have suggested that the success of inclusive education depends on the knowledge and skills of general education teachers and their attitudes and beliefs about including students with disabilities (Friend and Bursuck, 2006).

Teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education

The successful implementation of inclusive policies relies greatly on the willingness of the teachers to accept them (de Boer et al., 2011). Therefore, improving the deficiencies within the education system that negatively affect teachers’ perceptions of toward inclusive education needs to be assessed. Inclusion involves adapting the learning environment and curriculum to meet the needs of all students and ensuring that learners belong to a community (Cushner et al., 2012). In-service teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education have been debated and studied extensively (Magumise and Sefotho, 2020), however, only a limited number of studies have examined the views of pre-service teachers.

There is growing concern regarding teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education and their readiness to integrate learners with disabilities into the mainstream learning environment to teach them alongside their peers without special needs (Daane et al., 2000). According to Carpenter and Dyal (2001), inclusion is most effective when proactive principals create effective co-teaching models. The perceptions of general classroom teachers and special education teachers must be positive for collaboration to be effective. It is plausible that the quality of inclusion programs established in schools may suffer from both attitudinal and training factors leading to a lack of preparation for working with learning with disabilities (Kilanowski-Press et al., 2010). Cheng (2011) noted that despite teachers’ positive perceptions of inclusive education and support for such educational practices, previous studies have shown a negative attitude toward its implementation.

From the point of view of many teachers, there is a need to reassess the curriculum, teaching strategies, and classroom environment to successfully implement inclusive practices (Ghergut, 2010). This is because teachers perceive learners with emotional or behavioral disorders as more challenging than those with other disabilities (Chhabra et al., 2010). The perceptions of primary and high school teachers regarding inclusive education are often similar in many instances (Barco, 2007; Ross-Hill, 2009). Wiggins (2012) found an association between teachers’ perceptions of inclusion and the classroom setting.

Teachers’ attitude toward inclusive education

Solis et al. (2019) defined attitudes as beliefs and feelings based on knowledge that guides a person’s behavior, opinions, and feelings. The attitudes of teachers affect the quality of instruction provided to learners (López and Hinojosa, 2012; Esteban et al., 2017; Williams-Brown and Hodkinson, 2020). Therefore, Solis et al. (2019) asserts that attitudes can be modified, and that training is crucial to this process. It has been shown that training, especially regarding responses to diversity (Pérez-Jorge, 2010; Suriá, 2012; Pérez-Jorge et al., 2020), does not seek only to improve the educational response of students, but also to expand expectations around their abilities (Pérez-Jorge et al., 2020). In general, educators are hesitant to support inclusive education and admit students with special needs to general classes.

An inclusive education policy cannot be implemented effectively without a positive attitude from teachers (Shade and Stewart, 2001). Teachers’ acceptance of the policy of inclusion is likely to influence their commitment to implementing it (Bradshaw, 2003). In general, there is a significant correlation between the attitudes of teachers and the categories of teachers, with special-education teachers generally exhibiting more positive attitudes toward inclusive education (Engelbrecht et al., 2013; Hernandez et al., 2016). In addition, school administrators are more likely to be positive than teachers (Boyle et al., 2013), whereas secondary school teachers tend to be less positive than primary school teachers (Chiner and Cardona, 2013).

In their literature review, Avramidis and Norwich (2002) contended that more support and resources could improve the attitudes of teachers. It appears from this literature review that the views of the personnel who have the most responsibility for implementing the inclusive education policy—teachers—play an important role in its successful implementation. For the adoption of inclusive practices in schools to succeed, teachers’ beliefs and attitudes must be considered because their acceptance of the policy of inclusion is likely to affect their commitment to implementing it (Avramidis and Norwich, 2002). Evidence suggests that most teachers have negative attitudes toward students with disabilities and their inclusion in general education classrooms (Barco, 2007; Ross-Hill, 2009).

Methodology

Research design

This study used a cross-sectional survey research design. The procedure was considered appropriate because it served as a motive for participating in an ongoing debate and affirmation of factors responsible for teachers’ values and attitudes toward the inclusion of learners with special needs. The design would provide an opportunity to understand teachers’ perceptions and values regarding an inclusive educational learning environment. Two publicly funded institutions were selected for the study.

Participants

For the study, pre-service teachers from a publicly funded university and a college of education were selected. A publicly funded university was randomly selected from two public universities in Oyo State, Nigeria. Furthermore, one of the three publicly funded colleges of education was selected using a random sampling technique. All participants received academic instruction in English at their respective schools. Their willingness to participate in the study was also considered and only those who responded in the affirmative to the question on participation were included in the study during the first semester of the 2021/2022 academic session (Sedgwick, 2013).

Instrumentation

The pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education were measured using a self-designed questionnaire that was divided into three sections (α = 0.73, α = 0.81, and α = 0.79). There were four points on the Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree.

Eight items were on the five items on the knowledge subscale, perception subscale, and eight items on the attitude subscale. Perception subscale items included: It is detrimental for other students to have learners with disabilities in mainstream classrooms; Respecting the individual differences of all learners is essential for inclusion in Nigeria; Learners with special needs are more likely to succeed academically in inclusive classrooms; and Learners with disabilities are more likely to improve their social skills in mainstream classes. Items on the subscales included: I want inclusive education to address individual differences; Social justice will be promoted in schools through inclusive education; I feel that teaching about diversity and inclusive education is my professional responsibility; and All teachers should be responsible for implementing inclusive education.

Some of the items included in the attitude subscale are: Teaching special needs learners is rewarding; I am not familiar with the resources required for teaching talented academic learners; Learners with special needs will be marginalized in the inclusive learning environment; and I cannot teach in an inclusive school. Others were: I believe that inclusiveness would require teachers to work harder at their jobs; ’I think inclusion can work in all schools; and Learners who need specialized academic support should be removed from the class. Scores ranged from 27 to 45 on the perception subscale, 10 to 24 on the subscale, and 26 to 43 on the attitude subscale.

Data collection

We collected data from pre-service teachers from the faculty of education of a public university and a college of education in Nigeria. They responded to the questionnaire in English, having participated in a 6-month mandatory professional practice in teaching. Prior to participating in the study, participants were informed about the study’s purpose.

Ethical declarations

Informed consent was obtained by completing the form digitally by all participants after confirming an understanding of the study objectives. Profiles and responses were kept confidential.

Data analysis

The dependent variables were knowledge, perception, and attitudes, while gender (male vs. female) and program (Nigeria Certificate in Education vs. Degree) were the independent variables. Inferential statistics using the 3 × 2 factorial MANOVA were generated to determine the differences in participants’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education vis-à-vis their gender and programs. A MANOVA was used to assess the differences in knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes based on gender regarding inclusive education in different pre-service teaching training programs in Nigeria. MANOVA assumptions included multivariate normality, homogeneity of variance, and the quality of variance errors of the independent variables across the dependent variables. The dimensions of the variables examined made MANOVA a suitable analysis method for the data collected in this study. Data containing one or more factors (each with more than one level) and two or more independent variables may be analyzed with this method (Grice and Iwasaki, 2007).

Results

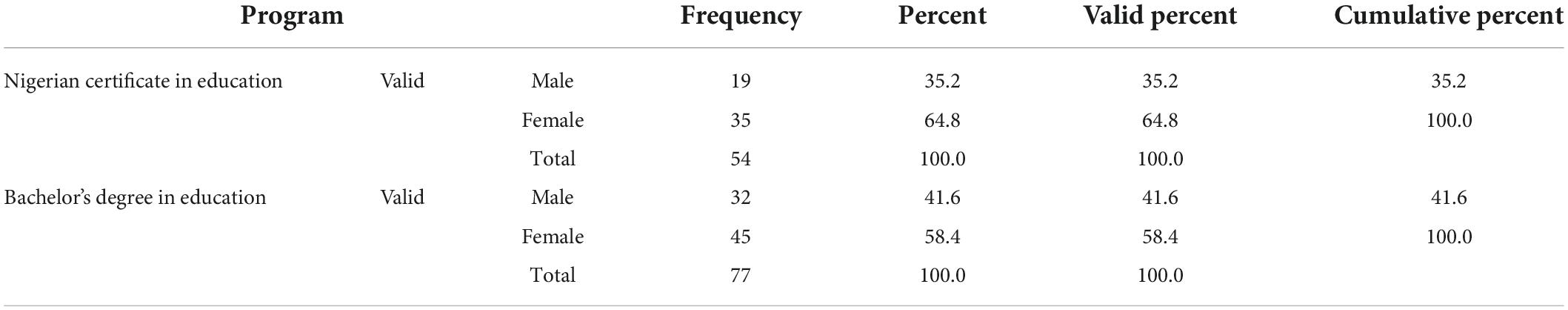

Table 1 is presents the demographic data of study respondent. The numbers of pre-service teachers from the Certificate in Education and Bachelor’s degree in education who participated in the study were 54 and 77, respectively. Of the participants, 41.22% were engaged with the program of the college of education and 58.78% with that of the degree in education. Of the study participants from the college of education, 19 (35.20%) were male and 35 (64.80%) were female. Similarly, 32 (41.60%) male and 45 (58.40%) female pre-service teachers studying for Bachelor’s degree in Education completed the research instrument.

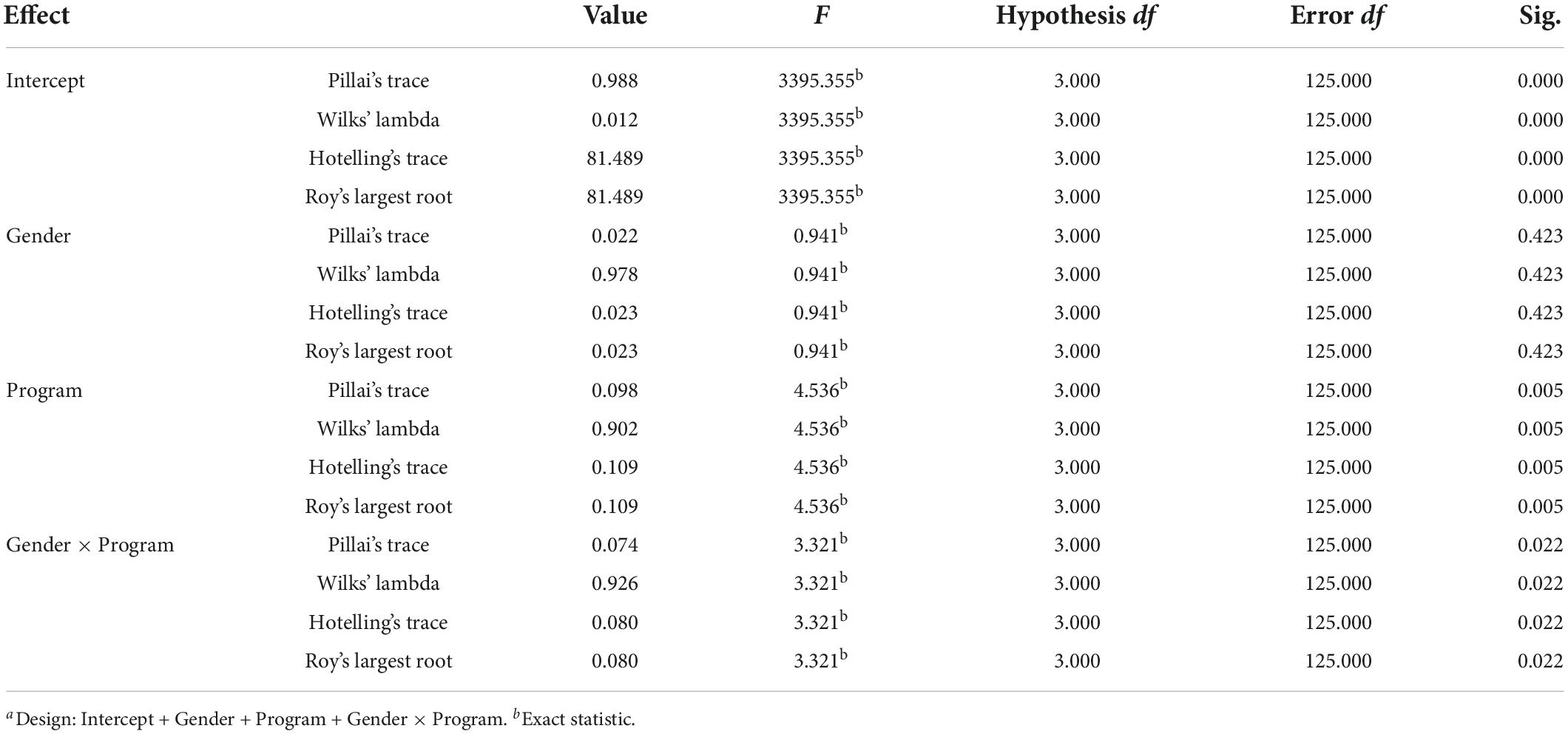

The results presented in Table 2 revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the gender of pre-service teachers (male or female) and the programs (university or college of education) in terms of their knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education: F(3, 125) = 0.941, ρ = 0.022; Pillai’s trace = 0.074; at 0.05 level of significance. Although Wilks’ lamda value is regarded as one of the most reported statistics (Pallant, 2011), Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) recommended Pillai’s trace value as stronger if the data had an unequal sample size. It was further revealed that the knowledge, perceptions, and attitudes of pre-service teachers was only statistically different in terms of program and not gender at: F(3, 125) = 4.536, ρ = 0.005; Pillai’s trace = 0.098 at 0.05 level of significance. Thus, to determine if the noticeable variance is peculiar to a certain program or across all dimensions of the dependent variables, univariate analysis was conducted as indicated in Table 3.

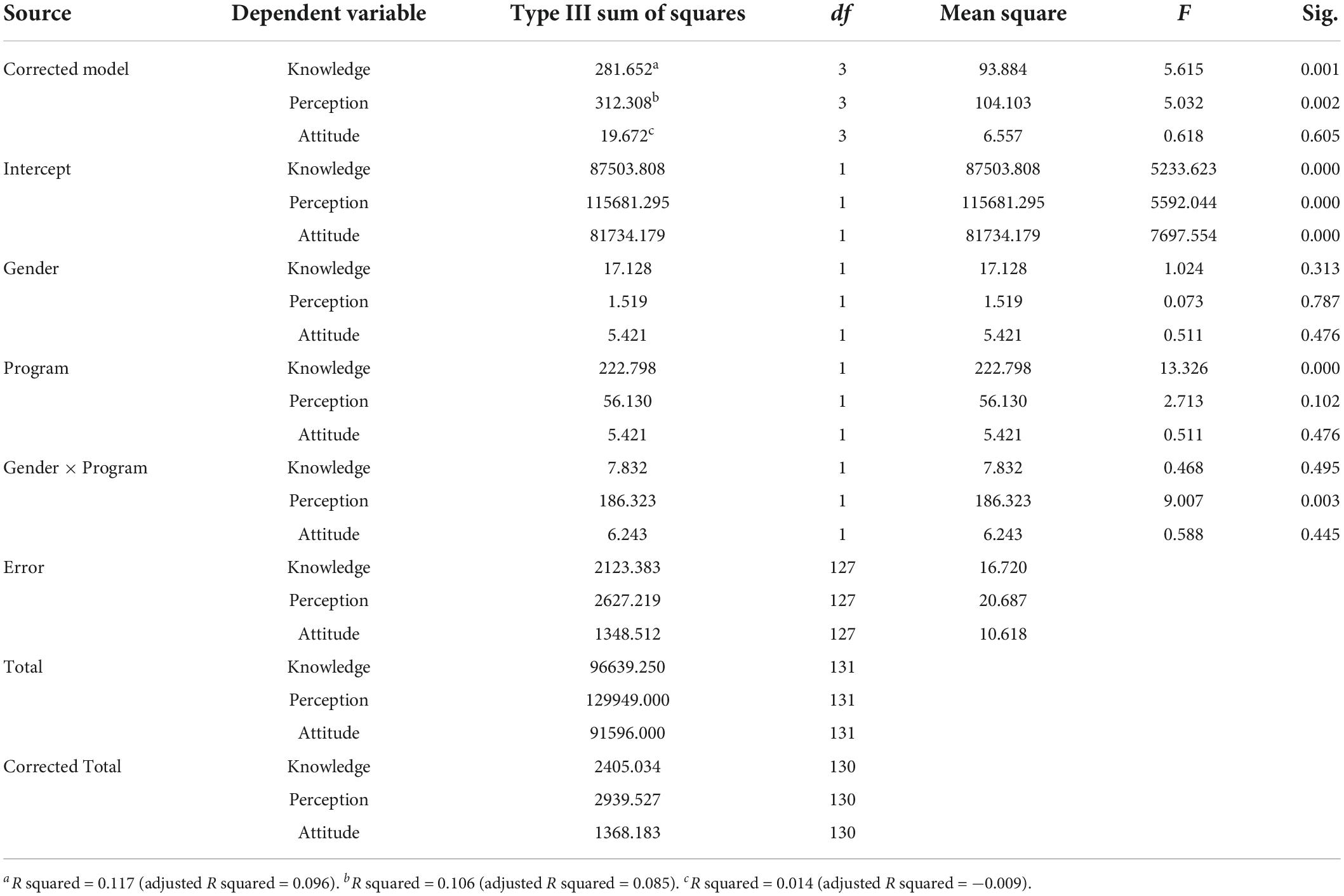

Table 3 shows the results for the dependent variables (knowledge, perception, and attitude) considered separately. The Bonferroni adjustment was used to reduce the risk of committing a Type 1 error, especially when numerous analyses are performed. A new alpha level of 0.017 can be calculated by dividing the original alpha level of 0.05 by 3 (number of dependent variables) (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007; Pallant, 2011). After Bonferroni adjustment alpha of 0.017, based on gender: knowledge, F(1, 125) = 1.024, ρ = 0.313; perception, F(1, 125) = 0.073, ρ = 0.787; and attitude, F(1, 125) = 0.511, p = 0.476; were found non-statistically different between male and female pre-service teachers because all variables exceeded the new alpha level of 0.017. Hence, there was no statistically significant difference between male pre-service teachers and female pre-service teachers in terms of their knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education.

Furthermore, using the adjustment alpha of 0.017, the result revealed that: participants knowledge, F(1, 125) = 13.326, ρ = 0.000; perception, F(1, 125) = 2.713, ρ = 0.102; and attitude, F(1, 125) = 0.511, p = 0.476. The results showed that pre-service teachers’ perceptions and attitudes were non-statistically different significantly, based on programs (university and colleges of education) because the two variables exceeded the new alpha level of 0.017. Thus, it implied that regarding the perceptions and attitudes of the pre-service there was no statistically significant difference between male pre-service teachers and female pre-service teachers in terms of their knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education. The results, however, showed that pre-service teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education varied significantly between the programs.

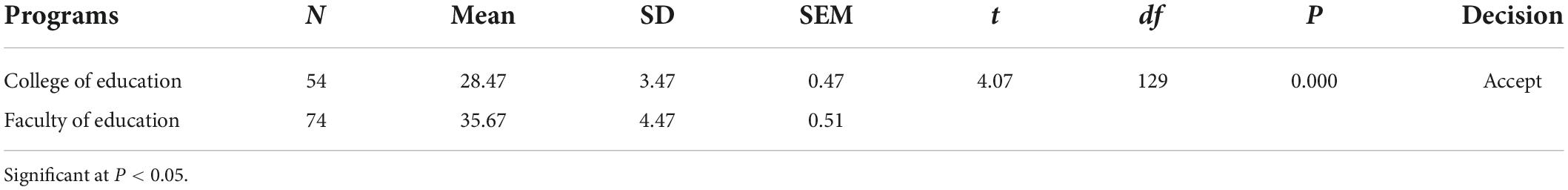

Table 4 revealed that a significant difference did exist between the college of education and faculty of education pre-service teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education: t(129) = 4.07, ρ = 0.000. Since the calculated significance (0.000) was less than the critical alpha level of significance (0.05), the implication is that the college of education and faculty of education pre-service teachers were statistically and significantly different in their knowledge of inclusive education. Therefore, it implied that pre-service teachers from the college of education program had better knowledge of inclusive education than their counterparts in the faculty of education at the university.

Table 4. Comparison of pre-service teachers’ knowledge of inclusive education between programs (college of education and faculty of education).

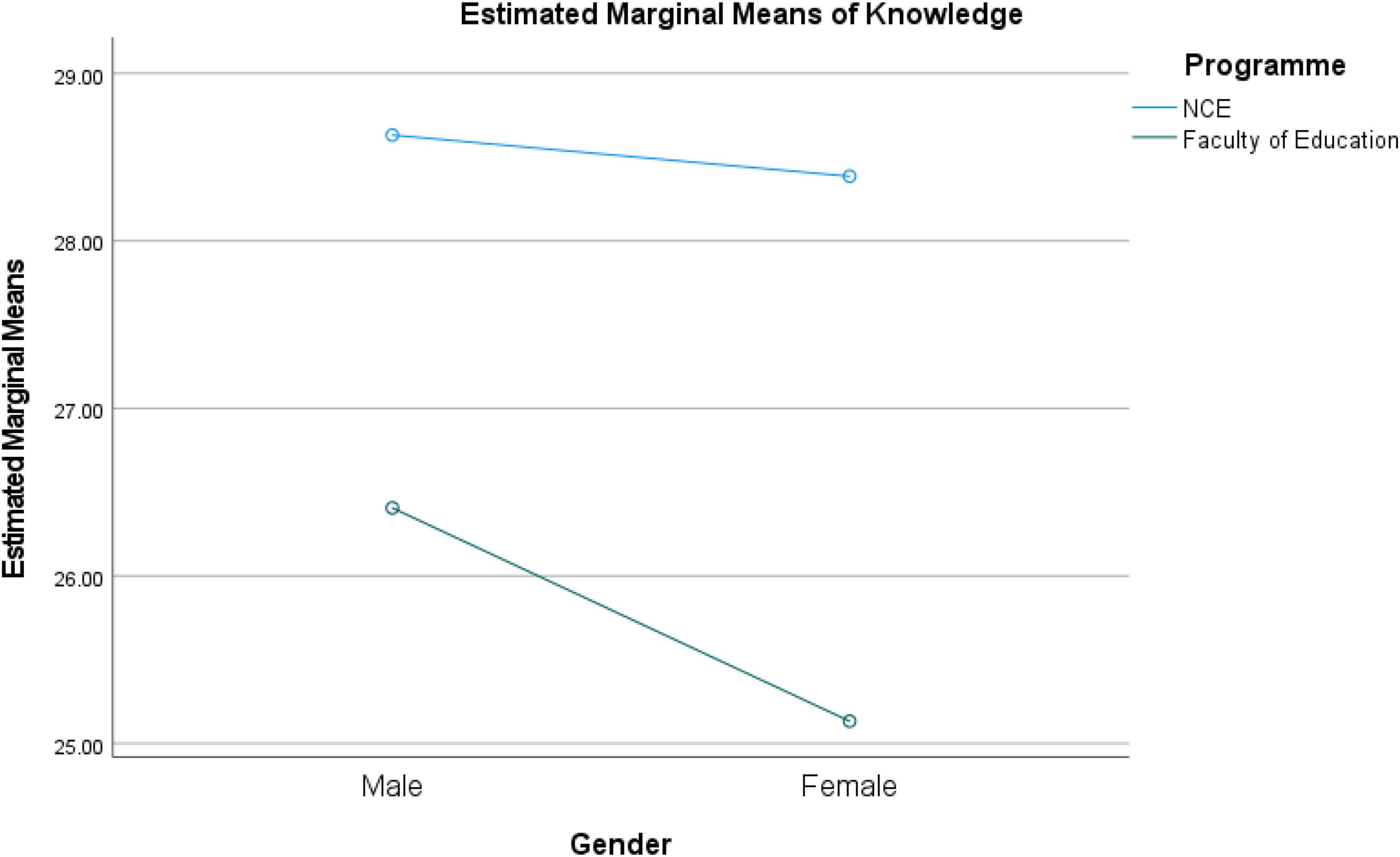

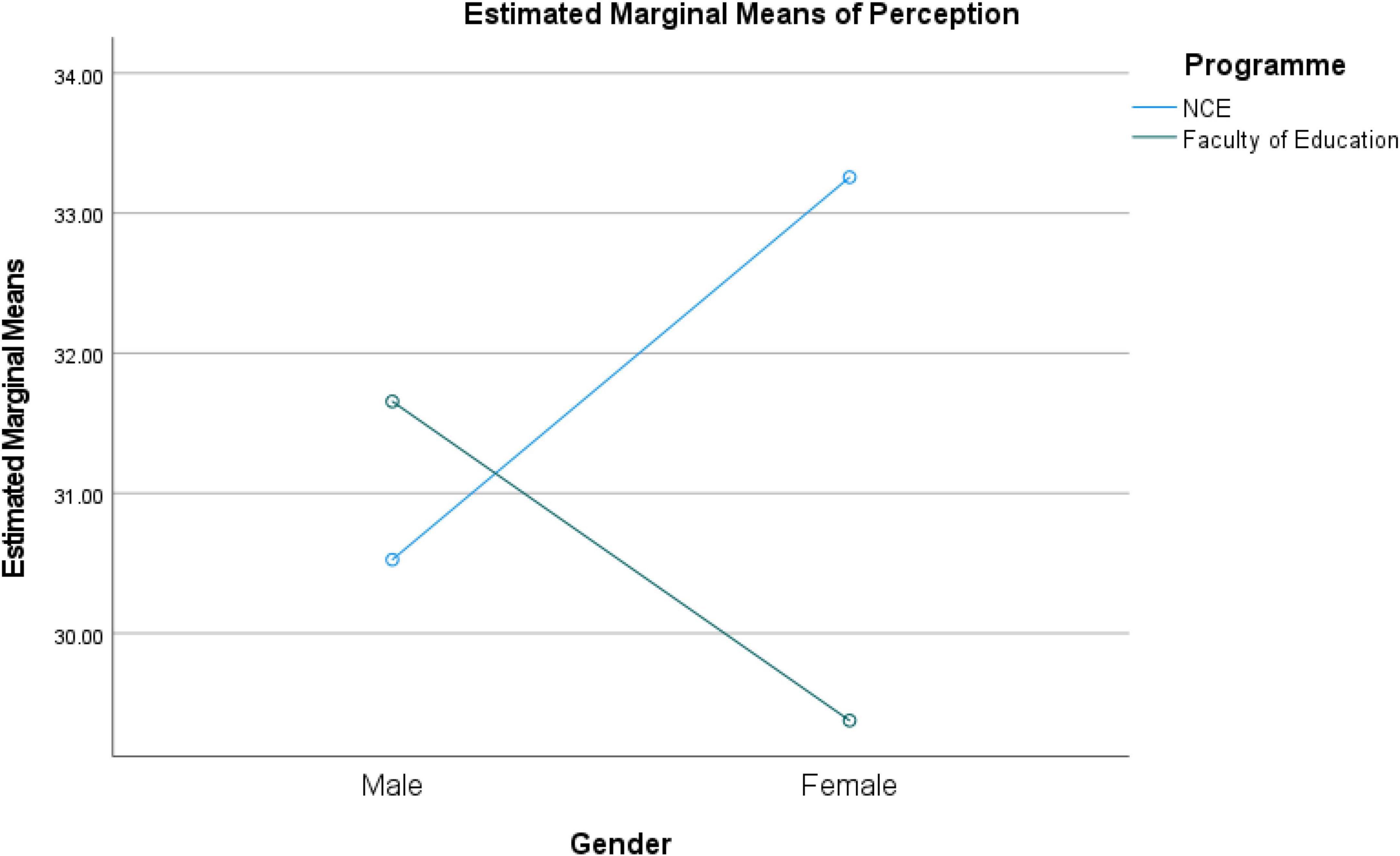

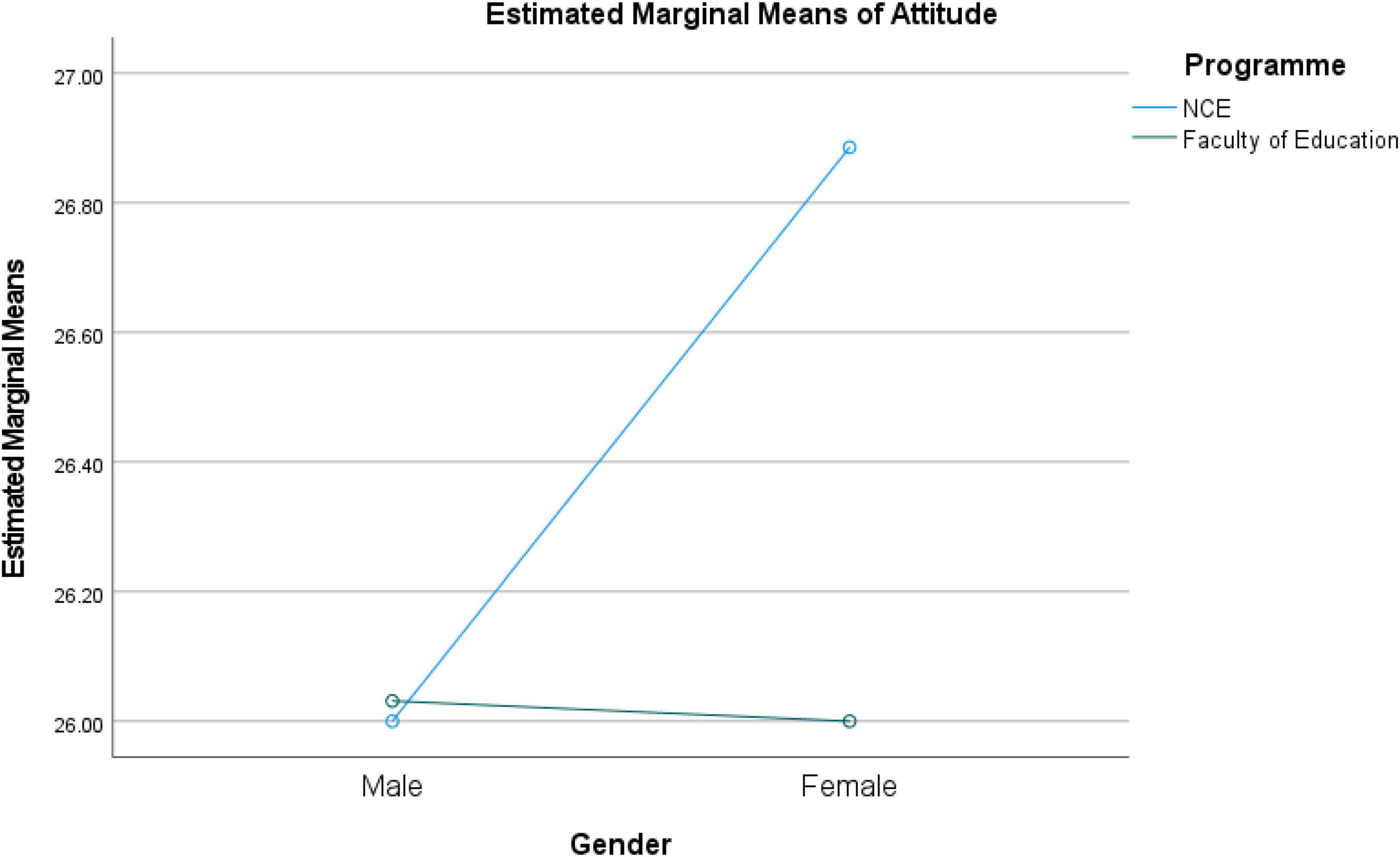

Furthermore, slopes were plotted to determine if the gender (male or female) and program (college of education and university) of participants were significant predictors of the dependent variables and clarified their relationships. The graphs presented in Figure 1 show linear slopes, but Figures 2, 3 depict non-linear slopes. According to the findings, pre-service teachers’ perceptions and attitudes differed between genders and programs. Figure 1 shows no interaction between the college of education and university programs of participants and their gender. However, the college of education programs allowed pre-service teachers to gain a deeper understanding of inclusive education than those in the faculty of education at the university. Figures 2, 3 demonstrate the interaction between participants’ gender and programs. There was a high-level of interaction between gender and the program in Figure 2, and how participants perceived inclusive education. However, participants in the college of education program had a higher perception of inclusive education than those in the university program. Figure 3 shows a lower interaction between the independent variables (gender and program) and perceptions of inclusive education among participants. Pre-service teachers in the college of education program were more optimistic about inclusive education than their university counterparts.

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means interaction between gender and programs on pre-service teacher knowledge about inclusive education.

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means interaction between gender and programs on pre-service teacher perception about inclusive education.

Figure 3. Estimated marginal means interaction between gender and programs on pre-service teacher attitudes about inclusive education.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education. No significant difference was found based on the comparison of pre-service teachers’ gender with knowledge of inclusive education. However, pre-service teachers from the college of education had better knowledge of inclusive education. This suggests that teachers from the college of education are more likely than their counterparts from the faculty of education at the university to embrace inclusive education and make meaningful contributions to inclusive education and equality. In line with these findings, Ministry of Education (2015) indicated that a lack of knowledge about the universal right to primary education and inadequacies in school management and teaching excluded many children from all education and poor-quality education.

The poor implementation of inclusive education in Nigeria may be due to limited knowledge regarding inclusive education. To yield good performance in schools, Rouse (2010) contends we must address the perceived lack of knowledge among pre-service and in-service teachers about managing learners in inclusive education classrooms. However, program type was found to have a significant relationship with pre-service teacher knowledge of inclusive education. Lambe and Bones (2006) concur that pre-service training is the best time to foster favorable attitudes and build confidence in the teaching profession. Pre-service teachers need adequate training to enhance their knowledge of inclusive education. In addition, Majoko and Phasha (2018) found that universities did not teach pre-service teachers about inclusive education.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Wanjiru (2017), who posited that teachers perceived that their knowledge and skills were insufficient to teach learners with disabilities effectively in inclusive learning situations. They expressed concern that this would negatively affect learners’ academic performance. According to the present findings, pre-service teachers from the college of education were more inclined to perceive inclusive education positively than respondents from the faculty of education at a university. In addition, there was a significant interaction between gender and perception of inclusive education. Female pre-service teachers at the college of education rated inclusive education more positively than their counterparts at the faculty of education. Cheng (2011), who also found positive teacher perceptions of inclusive education, concurred with this finding.

Despite being ready to teach students with disabilities, participants in the study of Mayat and Amosun (2011) worried about how they would cope with rigorous academic activities in the lecture rooms of an engineering faculty. The results showed that pre-service teachers from the faculty of education had poor perceptions of inclusive education and were less likely to make adequate educational provisions for students with disabilities when compared to pre-service teachers from the college of education. Teachers perceived students with emotional or behavioral disorders as more challenging to teach than children with other disabilities (Chhabra et al., 2010). Although the pathological medical model continued to dominate the educational activity in many schools, mainstream teachers believed children who were labeled “different” were not their responsibility (Angelides et al., 2006). Teachers’ previous experiences with special education children also significantly influenced their attitudes.

People who frequently interact with people with disabilities have a more positive attitude toward inclusion than those with little contact (Forlin et al., 1999). In the opinion of many teachers, successful implementation of inclusive practices should be based on a thorough review of the curriculum and strategies used with children with special needs (Ghergut, 2010). The findings did not show that pre-service teaching training with structured fieldwork experience fostered favorable changes in attitudes toward inclusive education. The content and pedagogy of the course can explain a portion of the change in participants’ attitudes regarding inclusive education, especially in the cognitive subscale that measures pre-service teachers’ ideas, thoughts, beliefs, or opinions about it. There is an assumption that a focus on the needs of children with different disabilities may prepare prospective teachers to teach students with similar disabilities (Sharma et al., 2008). However, these findings contradict previous studies (Johnson and Howell, 2009; Taylor and Ringlaben, 2012; Killoran et al., 2014) which suggested that information-based courses at universities might influence pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion.

Conclusion

Some implications arise from this finding. As a first step, courses need to expose pre-service teachers to various educational settings to prepare them for an inclusive classroom. It is also necessary to include topics addressing inclusive education into course structures to allow for content exploration, the development of strategic knowledge and skills, and closer exposure to critical resources. Inclusive education can be implemented effectively only if the curriculum and resources are adequate. Developing a curriculum for pre-service teachers can be influenced by the findings of this study. Pre-service education programs should include a sound theoretical component and a practical component where students would be able to interact meaningfully with people with disabilities.

Moreover, institutions saddled with the responsibility of training pre-service teachers should scale up the content of their curricula so that trainee teachers have a clear understanding of the nuances of inclusive education and what is feasible in a real inclusive classroom environment. Expanding curricula for the pre-service teacher training program is essential for developing just and egalitarian societies. In addition, it would help to ensure that children with disabilities are not stereotyped based on the segregation of their educational facilities. Training activities should be incorporated into the curricula to ensure that pre-service teachers are adequately prepared to teach learners with disabilities. For inclusive education to be successful, pre-service teachers must be guided in modeling the pedagogy required.

The study was limited to pre-service teachers who had participated in the practical aspects of teacher training in Nigeria. Comparative cross-national studies should be conducted to examine pre-service teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in all regions of Africa. Using more comprehensive research instruments to assess demographic variables and not necessarily gender would be beneficial.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

UJ conceived the research and did the data collection. JP worked and edited the manuscript. Both contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Innovation and National Research Foundation of South Africa, South African Research Chair in Education and Care in Childhood, Faculty of Education, University of Johannesburg, South Africa (Grant No. 87300, 2017).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Adigun, O. T. (2021). Inclusive education among pre-service teachers from Nigeria and South Africa: A comparative cross-sectional study. Cogent Educ. 8:1930491. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2021.1930491

AlMahdi, O., and Bukamal, H. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusive education during their studies in Bahrain teachers’ college. SAGE Open 9:2158244019865772. doi: 10.1177/2158244019865772

Alnasser, Y. A. (2020). The perspectives of Colorado general and special education teachers on the barriers to co-teaching in the inclusive elementary school classroom. Education 49, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2020.1776363

Angelides, P., Stylianou, T., and Gibbs, P. (2006). Preparing teachers for inclusive education in Cyprus. Teach. Teacher Educ. 22, 513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.11.013

Arias, B., Verdugo, M., Gómez, L., and Arias, V. (2013). “Actitudes hacia la discapacidad (Attitudes towards disability),” in Discapacidad e Inclusión, Manual Para la Docencia, eds M. Verdugo and Y. R. Schalock (Spain: Amarú Ediciones), 61–88.

Avramidis, E., and Norwich, B. (2002). Teachers’ Attitudes towards Integration/Inclusion: A Review of the Literature. Europ. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 17, 129–147. doi: 10.1080/08856250210129056

Baguisa, L. R., and Ang-Manaig, K. (2019). Knowledge, skills and attitudes of teachers on inclusive education and academic performance of children with special needs. PEOPLE 4, 1409–1425. doi: 10.20319/pijss.2019.43.14091425

Barco, M. J. (2007). The relationship between secondary general education teachers’ self-efficacy and attitudes as they relate to teaching learning disabled students in the inclusive setting. Ph.D thesis, Virginia: Virginia Polytechnic & State University.

Boyle, C., Topping, K., and Jindal-Snape, D. (2013). Teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion in high schools. Teach. Teaching 19, 527–542. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2013.827361

Broomhead, K. E. (2019). Acceptance or rejection? The social experiences of children with special educational needs and disabilities within a mainstream primary school. Education 47, 877–888. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2018.1535610

Campbell, J., Gilmore, L., and Cuskelly, M. (2003). Changing student teachers’ attitudes towards disability and inclusion. J. Intellect. Develop. Disabil. 28, 369–379. doi: 10.1080/13668250310001616407

Carpenter, L., and Dyal, A. (2001). Retaining quality special educators: A prescription for school principals in the 21st century. Catalyst Change 30, 5–8.

Carroll, A., Forlin, C., and Jobling, A. (2003). The impact of teacher training in special education on the attitudes of Australian pre-service general educators towards people with disabilities. Teach. Educ. Quart. 30, 65–79.

Castro, P. G., Álvarez, M. I. C., and Baz, B. O. (2016). Inclusión educativa. Actitudes y estrategias del profesorado. (Educational inclusion, Teacher attitudes and strategies.). REDIS 4, 25–45.

Cheng, K. (2011). “Shanghai: How a big city in a developing country leaped to the head of the class,” in Surpassing Shanghai: An agenda of American education built on the world’s leading systems, ed. M. S. Tucker (Massachusetts: Harvard Education Press), 21–48.

Chhabra, S., Srivastava, R., and Srivastava, I. (2010). Inclusive education in Botswana: The perceptions of schoolteachers. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 20, 219–228. doi: 10.1177/1044207309344690

Chiner, E., and Cardona, M. C. (2013). Inclusive education in Spain: How do skills, resources, and supports affect regular education teachers’ perceptions of inclusion? Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 17, 526–541. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2012.689864

Cushner, K., McClelland, A., and Safford, P. (2012). Creating inclusive classrooms. Human diversity in education. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Daane, C. J., Beirne-Smith, M., and Latham, D. (2000). Administrators’ and teachers’ perceptions of the collaborative efforts of inclusion in the elementary grades. Education 121, 331–338.

Dapudong, R. (2013). Knowledge and attitude towards inclusive education of children with learning disabilities: The case of Thai primary school teachers. Acad. Res. Int. 4, 496–512.

de Boer, A., Pijl, S. J., and Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitude towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 15, 331–353. doi: 10.1080/13603110903030089

Engelbrecht, P., Savolainen, H., Nel, M., and Malinen, O.-P. (2013). How cultural histories shape South African and Finnish teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A comparative analysis. Europ. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 28, 305–318. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2013.777529

Esteban, M. D. P., Canosa, V. F., and Ayala, A. S. (2017). Interculturalidad y discapacidad: Un desafío pendiente en la formación del profesorado (Interculturality and disability: A pending challenge in teacher education). Rev. Educ. Incl. 10, 57–76.

Florian, L. (2019). On the necessary co-existence of special and inclusive education. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 23, 691–704. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1622801

Forlin, C., Tait, K., Carroll, A., and Jobling, A. (1999). Teacher education for diversity. Queensl. J. Educ. Res. 15, 207–225.

Friend, M., and Bursuck, W. D. (2006). Including students with special needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Ghergut, A. (2010). Analysis of inclusive education in Romania. Results from a survey conducted among teachers. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 5, 711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.170

Granada, M., Pomés, M., and Sanhueza, S. (2013). Actitud de los profesores hacia la inclusión educativa. (Teachers’ attitude towards educational inclusion). Papeles Trabajo 25, 51–59. doi: 10.35305/revista.v0i25.88

Grice, J. W., and Iwasaki, M. (2007). A truly multivariate approach to MANOVA. Appl. Multiv. Res. 12, 199–226. doi: 10.22329/amr.v12i3.660

Hernandez, D. A., Hueck, S., and Charley, C. (2016). General education and special education teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion. J. Am. Acad. Spec. Educ. Profess. 16, 79–93.

Jerlinder, K., Danermark, B., and Gill, P. (2010). Swedish primary-school teacher’s attitude to inclusion: The case of PE and pupils with physical disabilities. Europ. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 25, 45–57. doi: 10.1080/08856250903450830

Johnson, G. M., and Howell, A. J. (2009). Change in pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward contemporary issues in education. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 24, 35–41.

Kilanowski-Press, L., Foote, C., and Rinaldo, V. (2010). Inclusion classrooms and teachers: A survey of current practices. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 25, 43–56.

Killoran, I., Woronko, D., and Zaretsky, H. (2014). Exploring pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 18, 427–442. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2013.784367

Lambe, J., and Bones, R. (2006). Student teachers’ perceptions about inclusive classroom teaching in Northern Ireland prior to teaching practice experience. Europ. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 21, 167–186. doi: 10.1080/08856250600600828

Lancaster, J., and Bain, A. (2007). The design of inclusive education courses and the self-efficacy of pre-service teacher education students. Int. J. Disabil. 54, 245–256. doi: 10.1080/10349120701330610

López, M., and Hinojosa, E. (2012). El estudio de las creencias sobre la diversidad cultural como referente para la mejora de la formación docente (Study of beliefs about cultural diversity as a reference for the improvement of teacher training). Educacion 15, 195–218. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.15.1.156

Loreman, T., and Earle, C. (2007). The development of attitudes, sentiments and concerns about inclusive education in a content-infused Canadian teacher preparation program. Exceptional. Educ. Canada 17, 85–106.

Magumise, J., and Sefotho, M. M. (2020). Parent and teacher perceptions of inclusive education in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Inclus. Educ. 24, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1468497

Majoko, T., and Phasha, N. (2018). The state of inclusive education in South Africa and the implications for teacher education programmes: Research report. Randburg: British Council. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.30210.56009

Mayat, N., and Amosun, S. L. (2011). Perceptions of academic staff towards accommodating students with disabilities in a civil engineering undergraduate program in a University in South Africa. J. Postsecond. Educ. Disabil. 24, 53–59.

Ministry of Education (2015). Education statistics annual abstract 2008 E.C. (2015/16). Addis Ababa: Ministry of Education.

Mngo, Z. Y., and Mngo, A. Y. (2018). Teachers’ perceptions of inclusion in a pilot inclusive education program: Implications for instructional leadership. Educ. Res. Int. 2018:3524879. doi: 10.1155/2018/3524879

Osisanya, A., Oyewumi, A. M., and Adigun, O. T. (2015). Perception of parents of children with communication difficulties about inclusive education in Ibadan metropolis. African J. Educ. Res. 19, 21–32.

Pallant, J. (2011). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using the SPSS program, 4th Edn. Berkshire: Allen & Unwin.

Pérez-Jorge, D. (2010). Actitudes y concepto de la diversidad humana: un estudio comparativo en centros educativos de la isla de Tenerife (Attitudes and concept of human diversity: A comparative study in educational centers on the island of Tenerife). Ph.D thesis, Spain: Universidad de La Laguna.

Pérez-Jorge, D., Pérez-Martín, A., del Carmen, Rodríguez-Jiménez, M., Barragán-Medero, F., and Hernández-Torres, A. (2020). Self and hetero-perception and discrimination in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Heliyon 6, e04504. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04504

Ross-Hill, R. (2009). Teacher attitude towards inclusion practices and special needs students. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 9, 188–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2009.01135.x

Rouse, M. (2010). “Reforming initial teacher education: A necessary but not sufficient condition for developing inclusive practice,” in Teacher education for inclusion: Changing paradigms and innovative approaches, ed. C. Forlin (London: Routledge), 47–55.

Savolainen, H., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., and Malinen, O.-P. (2012). Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: Implications for pre-service and in-service teacher education. Europ. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 27, 51–68. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.613603

Shade, R. A., and Stewart, R. (2001). General education and special education preservice teachers‘attitudes toward inclusion. Prevent. School Fail. 46, 37–41. doi: 10.1080/10459880109603342

Sharma, U., Forlin, C., and Loreman, T. (2008). Impact of training on pre-service teachers’ attitudes and concerns about inclusive education and sentiments about persons with disabilities. Disabil. Soc. 23, 773–785. doi: 10.1080/09687590802469271

Solis, P., Pedrosa, I., and Mateos-Fernández, L.-M. (2019). Assessment and interpretation of teachers’ attitudes towards students with disabilities / Evaluación e interpretación de la actitud del profesorado hacia alumnos con discapacidad. Cult. Educ. 31, 576–608. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2019.1630955

Sorkos, G., and Hajisoteriou, C. (2020). Sustainable intercultural and inclusive education: Teachers’ efforts on promoting a combining paradigm. Pedag. Cult. Soc. 29, 517–536. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2020.1765193

Suriá, R. (2012). Discapacidad e integración educativa: ¿qué opina el profesorado sobre la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad en sus clases? (Disability and educational integration: what do teachers think about the inclusion of students with disabilities in their classes?). Rev. Españ. Orient. Psicoped. 23, 96–109. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.23.num.3.2012.11464

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th Edn. New York: Allyn and Bacon.

Taylor, R. W., and Ringlaben, R. P. (2012). Impacting pre-service teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. High. Educ. Stud. 2, 16–23. doi: 10.5539/hes.v2n3p16

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (1994). The salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. France: UNESCO.

Timothy, A. E., Obiekezie, E. O., Chukwurah, M., and Odigwe, F. C. (2014). An assessment of English language teachers’ knowledge, attitude to, and practice of inclusive education in secondary schools in Calabar, Nigeria. J. Educ. Pract. 5, 33–39.

Wanjiru, N. J. (2017). Teachers’ knowledge on the implementation of inclusive education in early childhood centers in Mwea East Sub-County, Kirinyaga County, Kenya. Ph.D thesis, Kenya: Kenyatta University.

Wiggins, C. (2012). High School Teachers’ Perceptions of Inclusion. Ph.D thesis, Lynchburg, VA: Liberty University.

Williams-Brown, Z., and Hodkinson, A. (2020). ‘What is considered good for everyone may not be good for children with special educational needs and disabilities’: Teacher’s perspectives on inclusion in England. Education 49, 688–702. doi: 10.1080/03004279.2020.1772845

Yada, A., Tolvanen, A., and Savolainen, H. (2018). Teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy on implementing inclusive education in Japan and Finland: A comparative study using multigroup structural equation modelling. Teach. Teacher Educ. 75, 343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.011

Keywords: attitudes, inclusive education, knowledge, perceptions, pre-service teachers

Citation: Jacob US and Pillay J (2022) A comparative study of pre-service teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of, and attitudes toward, inclusive education. Front. Educ. 7:1012797. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1012797

Received: 05 August 2022; Accepted: 16 September 2022;

Published: 06 October 2022.

Edited by:

Raman Grover, Psychometric Consultant Vancouver, CanadaReviewed by:

Adigun Timothy Olufemi, University of Zululand, South AfricaMusa Ayanwale, National University of Lesotho, Lesotho

Copyright © 2022 Jacob and Pillay. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Udeme Samuel Jacob, dWRlbWUwMUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Udeme Samuel Jacob

Udeme Samuel Jacob Jace Pillay

Jace Pillay