- 1School of Foreign Languages, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

- 2School of Foreign Languages, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China

- 3School of Foreign Languages, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing, China

Many Chinese students further their master’s study in translation, however, only a few of them become translators at last and most of them gradually decrease their language learning motivation in the translation program. Based on Complex Dynamic Systems Theory, the study adopted a sequential mixed methods design with both questionnaires and interviews to collect the data. We collected 446 questionnaires to explore what types of affordances influence their language learning motivation most. After that, we interviewed six participants to explore how these affordances influence their motivation. Findings from the questionnaires showed that the affordances of the mentor can be divided into strong academic ability, rich academic resources, caring students, and strict requests; affordances of the instructor can be divided into informative courses, being serious in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and the reasonable course planning; affordances of the peer can be divided into peer pressure, shared learning resources, mutual encouragement, and mutual supervision. Affordances of the institution can be divided into a good learning atmosphere, sufficient internship opportunities, abundant library resources, good infrastructure, and scholarships. Findings from the interview showed that different interpretations of affordances lead to different effects on language learning motivation; affordance has little influence on intrinsic language learning motivation. This study provided some insights for policymakers and teachers on how to cultivate and promote translation students’ language learning motivation.

Introduction

Nowadays, English has become a global language, leading to a surge in the number and variety of English language learners. China, the most populous country, has the largest population of English language learners in the world (Crystal, 2008). Therefore, it is necessary to understand why English learners, especially English majors choose to study English as well as how they view the way English is taught and learned. This is also in line with the call for English language educators to gain a deeper understanding of their students’ attitudes and needs as well as linguistic resources, so as to adopt a more fluid perspective on the ways the language is taught (Pan and Zhang, 2021).

In recent years, it is a generally accepted fact that language learning motivation is a crucial contributor to L2 learning in all educational contexts (Dörnyei and Csizér, 2005). Dörnyei (2009) pointed out that language is not only an academic subject to be studied, but also a communicative medium to be used for social interaction, self-expression, and the establishment of a person’s identity. Motivation to learn an L2 presents a particularly complex and unique situation because of the multifaceted nature and roles of language itself.

Although many scholars have done a great job in exploring English language learners’ motivation (Ali, 2022; Jiao et al., 2022; Kühl and Wohninsland, 2022), there is a paucity of research into its role in the graduate students majoring in translation. China established the MTI Program to cultivate translation talents in China in 2007. Till now, the number of MTI students in China has jumped to a staggering number. MTI means Master of Translation and Interpreting, which is a master’s program for translation study. However, it has some differences. First, students in this program have their own mentors, who can guide their academic life. Second, this program focuses more on practice, which is designed to meet the job requirement. Lastly, this program was established in 2009 and is still in its initial stage. On this very note, this study combined questionnaires and interviews to explore what types of affordances of the mentors, instructors, peers, and institutions affect language learning motivation and how they affect the change of motivation.

Literature review

Motivation in second language learning

Motivation is commonly defined as “the extent to which the individual works or strives to learn the language because of a desire to do so and the satisfaction experienced in this activity” (Gardner, 1985, p. 10). It is an intricate and multidimensional concept that has been described as “one of the most elusive concepts in the whole domain of social sciences” (Dörnyei, 2001, p. 2). There is a consensus that various factors can influence one’s motivation, positively or negatively, directly or indirectly, in variable levels in a time-sensitive and dynamic fashion (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008). As a vital part of successful second language learning, motivation has attracted growing research attention in second language acquisition (Park, 2017).

Second language motivation research has gone through four successive developmental phases over the past decades. In the socio-psychological period, scholars Gardner and Lambert (1959) firstly introduced social psychology into L2 learning and put forward the social-educational model in second language learning, which has been the dominant L2 motivation model for many years. The study of second language learning motivation in this stage focused on motivation types and classification, which can be divided into the “integrative” and “instrumental” language learning tendencies or motivation types (Gardner and Lambert, 1972). However, with the growing gap between motivational thinking in the second language learning field and in educational psychology at the beginning of the 1990s, motivation research entered the cognitive-situated period. In this period, the construct of motivation began to embrace many cognitive theories, including self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1986), attributional theory (Weiner, 1992), self-determination theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985), the expectancy of success/incentive value theory (Wigfield and Eccles, 2000), and goal theory (Locke and Latham, 1990). However, with the shift of motivation research from a macro-social-psychological perspective, researchers focused more on motivational evolution (Dörnyei, 2009), which marked that motivation research entered the process-oriented period. In this period, people focused on the fluctuating temporal nature, considering that motivation as a static attribute is not adequate to explain motivation (Dörnyei, 2001) and that language initial motivation to learn a second language is hard to sustain and often declines over time (Dörnyei and Csizér, 2002; Gardner et al., 2004; Tseng and Schmitt, 2008). The Process Motivation Model framework was an effective and coherent framework to explore the motivation of second language learning, which connected the research plan, instrument design, data collection, and interpretive analysis of data together (Bower, 2019). The main limitation of motivation research in the process-oriented period is its ignorance of the interference from other ongoing activities the learner is engaged in. Currently, it has evolved into the socio-dynamic period featured by a keen interest in the complexity of the motivation process and its dynamic interaction with internal, social, and contextual variables (Dörnyei and Ushioda, 2011).

The studies of second language learning experienced significant changes over the years. Scholars tried to find new frameworks to illustrate a clear understanding of motivation. On this very note, the motivational framework base changed from linear cause–effect relationships to complex and dynamic systems. The core of the study was not classification and reasons of motivation statically anymore, but the changes in motivation and interaction among internal and external factors. Scholars tended to find a practical framework to trace the English learning motivation system’s trajectories dynamically while exploring frameworks for motivation research. Motives did not work individually but worked with other motives and the context when researching the motivational trajectory of language learners (Papi and Hiver, 2020). The motivational development of language learners can be seen as a complex and adaptive system; the environmental conditions had dynamic interactions with the changes in motivation types (Papi and Hiver, 2020). With the instruction of Dynamic System Theory, the analysis of the changes in motivations was not linear interactions with variables but dynamic connections of multi-level subsystems and parameters (Yashima and Arano, 2015).

Akdağ (2019) focused on the achievement goal orientations of translation students and explored the effects of gender, department, class, and perception of academic achievement on the translation students’ motivation. Findings show that learning orientation varies significantly by gender, perception of academic achievement, and performance-approach orientation by department and gender. García (2020) explored the motivating factors of volunteer translators in a Spanish Chinese fansubbing group. Findings showed that most fan translators think of themselves as consumer producers and show traits similar to those of their readers. Jabu and Abduh (2021) explored the motivation of 40 students participating in translation training in the Indonesian context. Findings showed that students portray their future selves as the key motivational factor in participating in translation courses. They faced both linguistics and non-linguistics challenges in doing translation work. Although these scholars did an excellent job exploring the translation’s motivation, they focused more on the students and ignored the environment around them. Therefore, based on Complex Dynamic Systems Theory, this study aims to explore which affordances affect language learning motivation and how they affect the change of motivation.

Affordance

Affordances have been extensively used as a theoretical lens in education research. Gibson (1979, p. 127) firstly defined affordance as “what the environment offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill.” Van Lier (2000) introduced affordance theory into language learning and defined it as what is available to the person to do something with. The definition of affordance in the proposal refers to the language resources given by their learning environment, including classmates, teachers, and institutions.

Researchers have used affordance theory for studying 3-D Virtual Environments (Dalgarno and Lee, 2010), online social networks (Veletsianos and Navarrete, 2012), scaffolded social learning (Zywica et al., 2011), blogs and learning (Robertson, 2011), science learning (Webb, 2005), literacy (Hawkins, 2004). Current research about affordance in language learning is dominated by theoretical discussion and lacks sufficient empirical evidence (Kramsch, 2000). The existing empirical studies have been conducted mainly in the context of technology-assisted language teaching (McNeil, 2014), study abroad (SA) programs (Allen, 2010), multilingual environments (Aronin and Singleton, 2010; Aronin et al., 2013), foreign language teachers (Cheng and Wu, 2016), social learning space (Murray and Fujishima, 2013), and school language learning program (Cotterall and Murray, 2009; Peng, 2011; Qin and Dai, 2015).

In this article, we focus on the affordance of language learning programs, which have attracted much interest. For example, Cotterall and Murray (2009) researched Japanese students of English and investigated the development of their metacognitive knowledge. However, this study was its inability to explore the relationship between enhanced metacognitive knowledge and gains in language proficiency, due to intervening variables. Peng (2011) tracks a first-year college student’s belief about English teaching and learning since his enrollment from an ecological perspective. However, this inquiry only focuses on classroom affordances and ignores the affordance of the institution. Qin and Dai (2015) investigated English learners’ learning resources and interactive learning opportunities in a sociocultural environment at a university in northeastern China. However, this study ignored the language learners’ personalities, attitudes toward college English, interest in learning English, and peer help during the learning process.

In conclusion, many scholars have explored affordance in language learning from different perspectives. In terms of the research content, they focus more on the classroom or teachers and ignore the affordance of the institution and the peer. On this very note, we take a big picture look at the affordance and take the affordance from mentors, instructors, peers, and institutions into consideration. In this way, we can have a better understanding of how affordances affect language learning motivation.

Theoretical framework: Complex dynamic systems theory

Complex systems are “systems that are heterogeneous, dynamic, non-linear, adaptive, and open” (Larsen-Freeman and Cameron, 2008, p. 36). There were three essential features in CDST, variability, stability, and context (Waninge et al., 2014). It is a popular approach to studying second language acquisition (Gao and Zhou, 2021). In terms of language learners, De Bot et al. (2007) explain: “from a CDST perspective, a language learner is regarded as a dynamic subsystem within a social system” (p. 14). When it was applied to language development, CDST regards language as a complex, dynamic, and systematic system (Zheng, 2019). This theory has been used to describe developmental processes (e.g., Verspoor, 2017; Larsen–Freeman, 2019) and variability (e.g., Polat and Kim, 2014; Lowie et al., 2018) in L2 learning in a number of recent SLA studies.

The motivations changed chronologically, and different affordances are at play in the changes of them and these factors affect each other at the same time. In this sense, the CDST framework was an effective way to explore the changes in motivation and how these affordances worked under the system. The CDST perspective offers a conceptual tool for a relational unit of analysis (Hiver and Larsen-Freeman, 2019; Papi and Hiver, 2020), echoing the person-in-context ecological perspective (Ushioda, 2020). Under the instruction of CDST, the motivational trajectory was often taken as a complex and dynamic system and language learners as the agents. Several scholars have used the CDST theory to explore language learning motivation. For example, Thompson (2017) used the CDST theory to explore the motivational profiles of two advanced language learners of Chinese and Arabic. Zheng et al. (2020) applied the Q methodology to track the changing motivational profiles of 15 Chinese university students on the basis of the complex dynamic systems theory. In this light, CDST is a suitable theory for us to explore the effect of affordances on language learning motivation.

Research methodology

Research questions

This paper took the motivational development of students as a system and translation students as the agents of the system. Based on the Complex Dynamic Systems Theory, we aimed to find out what types of affordances affect language learning motivation. In addition, we tried to find out how affordances impact the change in students’ language learning motivation. On this very note, this paper proposed the following research questions:

1. What was the language learning motivation of the translation students before and after the translation program?

2. What types of affordances of the mentors, instructors, peers, and institutions affected the language learning motivation?

3. How did these affordances affect the changes of language learning motivation?

Participants

At first, 72 master students majoring in translation at the same university in northern China were requested to take part in a pilot study. After obtaining the information for the questionnaire, we started collecting data from a large sample of teachers in the second stage of the study. We sent out 500 questionnaires but end up collecting 446 viable copies of responses. These sampled students all pursued their master’s degrees in English translation in different cities in China, and most of them are from Dalian, Beijing, and Tianjin. While we made attempts to run through random sampling, we still collected most surveys from Dalian, from which two of our principal investigators came.

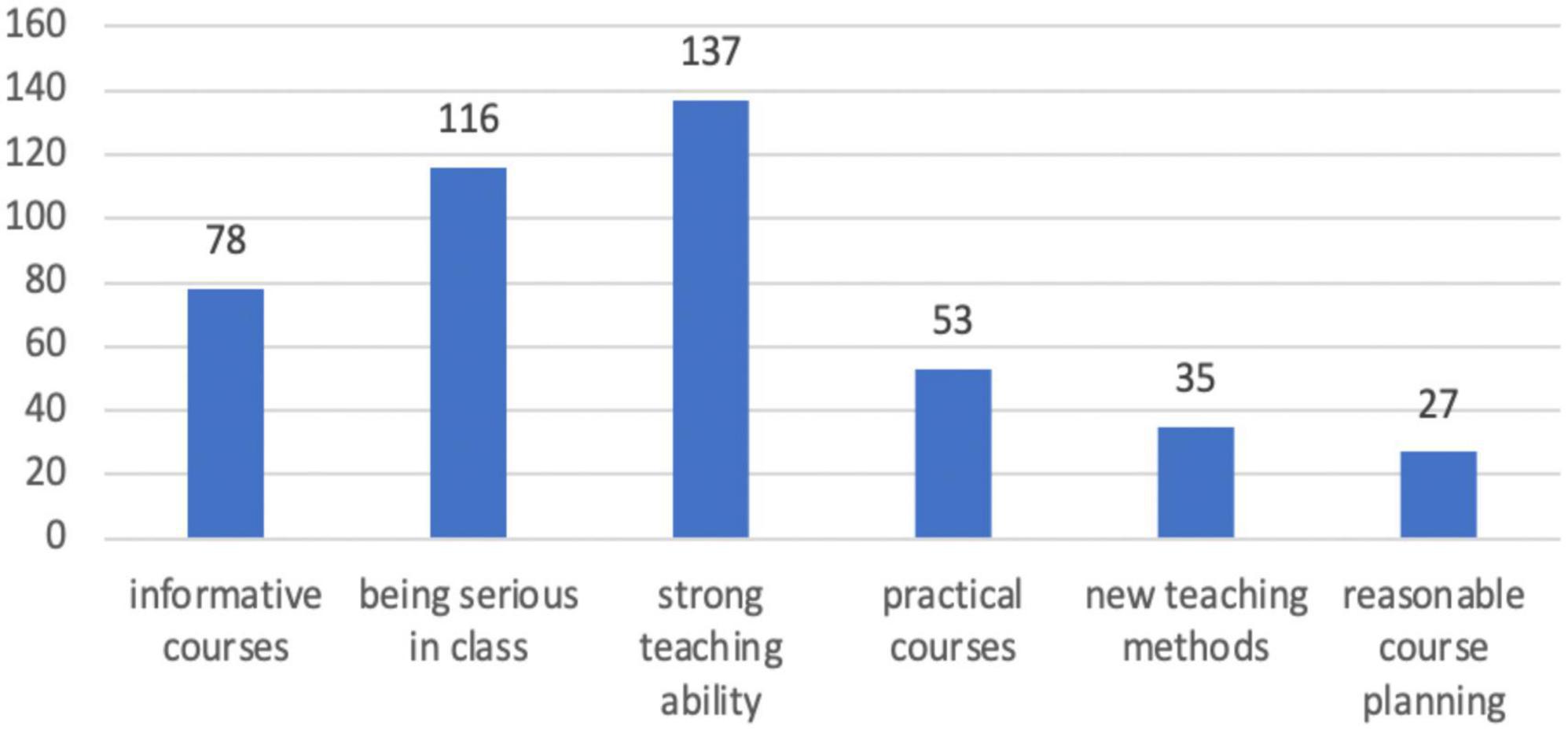

In the third stage, we further interviewed six participants from the selected universities. The participants were purposefully selected according to certain criteria, including but not limited to student willingness to participate, availability for interviews, and the manageability of the study. Specifically, we included three female participants and three male participants. All of them had been studying translation as masters for at least 2 years at the time the study was conducted. Some of them, however, get their bachelor’s degrees as non-English majors. Table 1 lists the biographical information of the six purposive participants.

Research method: An exploratory sequential mixed-methods design

We adopted an exploratory mixed-method design. When choosing our research method, we considered whether the design fits our research aim, purposes, and questions. The purpose of this study is to analyze which factors influenced students’ motivation and how they influenced their motivation.

We mapped out three stages for this study according to our design. For the first stage, we used qualitative analysis to report basic descriptive and correlation analyses of students’ perceived affordance and motivation. The second stage involved exploring whether these affordances are still the same on a larger scale and what kind of influencing factor is the most important affordance. In the third stage, we used a structured survey to interview the six participants and then analyzed their interview transcripts.

Instruments

The study consisted of three sections. Prior to undertaking the study, all participants were provided with an explanation of the study and a consent form that was embedded within the survey. Participants were informed that survey results would likely be published, and that participation was strictly voluntary. With the participants’ signed consent forms, we then guided the participants through the whole process.

In the first section, we mapped out the existing literature (Fayram et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2019; Gao, 2021; Gao et al., 2022) and framed the study with four dimensions of affordance, including mentor, instructor, institution, and peers. To ensure the validity and reliability of our study, a pilot study was conducted among a small group of students majoring in translation at the same university in northern China. In this stage, we used an open survey to check whether they agree that the four factors above influence their language learning motivation and to explore different sub-dimensions for each factor at the same time. In the second section of the study, with the results we obtained in the first section, we designed a multiple-choice questionnaire through a survey management platform (Wen Juan Xing), which helped us to collect and analyze the data. To make sure that the survey covered all affordances that translation students received, we added a blank answer at the end of each question of the questionnaire, which means that if the sampled students do not agree with the options we gave, they can add their own answers by themselves. In the third stage, with the results obtained in the first two sections, we used interviews to further solicit students’ opinions on affordance and motivation. The questions in this section were more retrospective.

Data collection and analysis

We collected and analyzed data according to the three stages scheduled in the study. In the first stage, we used an open survey to collect responses on language learning motivation and affordance during master’s study among 72 students and analyzed their answers before combining their answers with our initial framework. In the second stage, we hand out 500 multipole-choice questionnaires containing questions about affordance and finally received 446 valid questionnaires. The answers were analyzed and reported in figures. In the third stage, we conducted a structured interview with six participants to solicit answers to a handful of questions. Every respondent was interviewed for nearly 1 h, which was recorded by a recording pen produced by iFLYTEK. And then we used the pen’s voice-to-text function to transcribe the interviews and then analyzed the transcripts. In the process of analyzing data, we reviewed the participant’s answers and compiled a motivation profile of each participant to track his or her learning motivations during different periods. And then a cross-case comparison was conducted to compare and integrate the findings generated from each case in order to form a deeper and fuller understanding of the participants’ motivation change in the program. The goal of the interview is to find out how they interpret different affordances and how their interpretation of affordance affected their language learning motivation. To ensure the viability and reliability of our research, we returned to our interviewees in several cases to further check their answers. The whole process was conducted in Chinese as all our participants were Chinese students and they can better express their thoughts in Chinese. However, we used a translated version of the survey when we collected and analyzed our data.

Findings

Quantitative descriptions: What types of affordances affect language learning motivation

In this part, we present the initial motivations of these surveyed English language learners and the different affordances of four factors: mentors, instructors, institutions, and peers. Then a comparison between the initial and present motivation is made so as to demonstrate how these learners’ motivations change over their 2-year study.

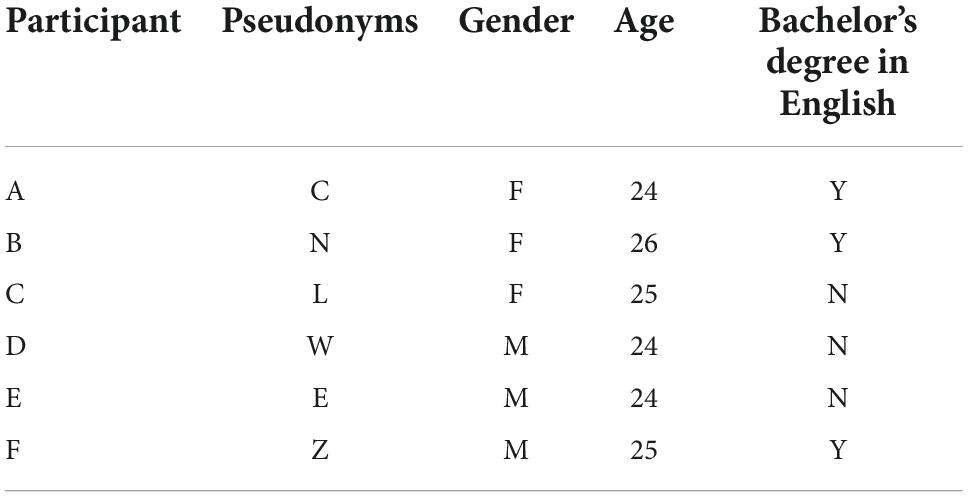

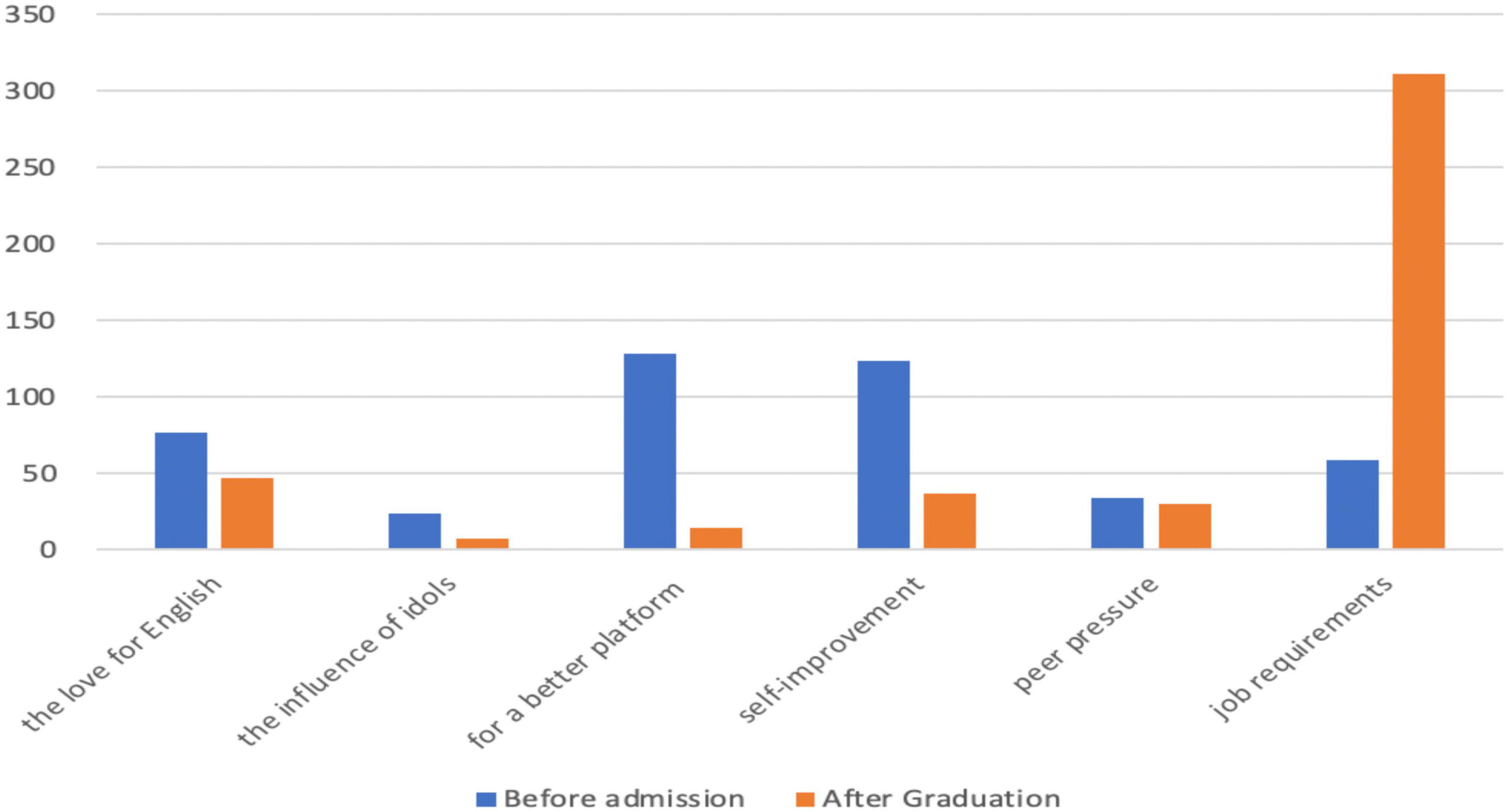

Figure 1 shows that students have various motivations to further their studies as English translation majors at the beginning of their 2-year studies. Among them, 128 students take the pursuit of a better platform as their initial motivation for their master’s studies; 124 students regard self-improvement as their initial motivation; 77 students further their master’s studies just because of their love for English; 59 students choose to be a postgraduate majoring in English because of job requirements. In addition, 34 students further their studies because they are affected by their peers; 24 students are influenced by their idols to become a postgraduate. To be exact, the first three factors are intrinsic ones, which play a more important role in motivation than the latter three extrinsic factors.

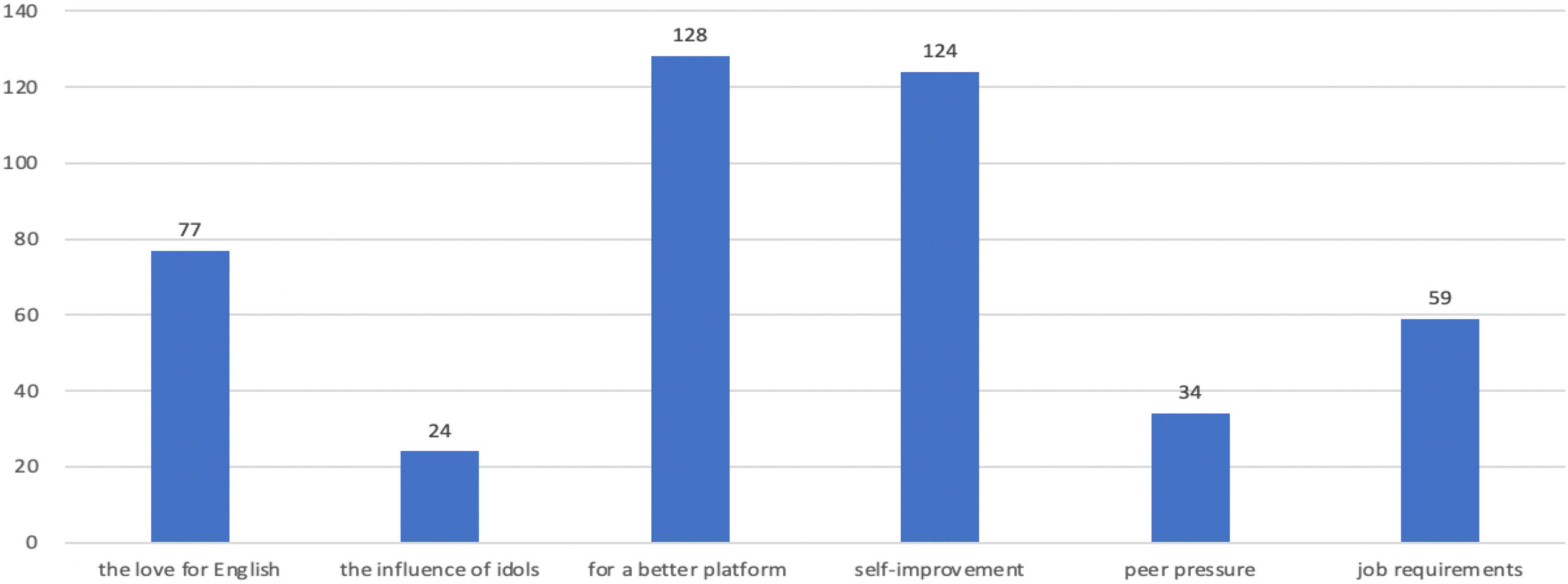

Figure 2 shows the affordances of mentors, including strong academic ability, rich academic resources, care for students, and strict requests. As shown in Figure 2, 168 participants think that mentors’ care for students is the most important factor in their motivation; 146 participants hold that their mentors’ strong academic ability motivates them most; 96 participants believe that their mentor’s rich academic resource is the most important factors behind their motivations. Additionally, 36 students think that the strict requests made by the mentor give them the most affordance.

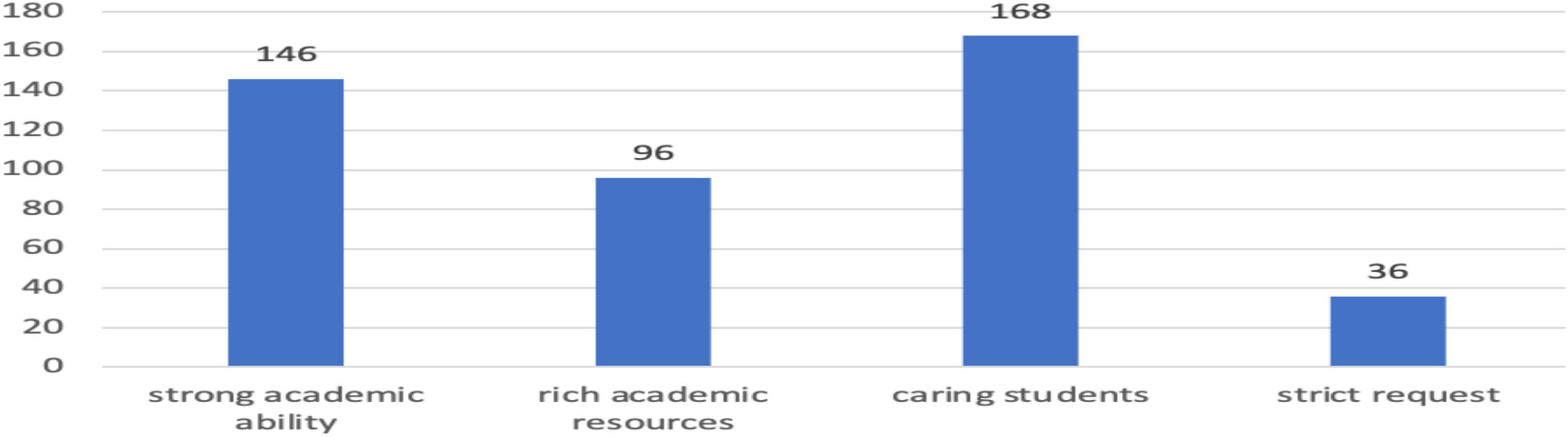

Figure 3 demonstrates the affordances of instructors, including informative courses, being serious in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and reasonable course planning. 137 students believe that instructors’ strong teaching ability ranks first in terms of its effect on motivation; 116 students think that a lecturer’s attitude of being serious in the class motivates them most; 78 students hold that the informative course is the main factor affecting their motivation; 53 students believe that informative course is the vital factor affecting their motivation; 35 students think that new teaching method motivates them most; 27 students believe that reasonable course planning motivates them most.

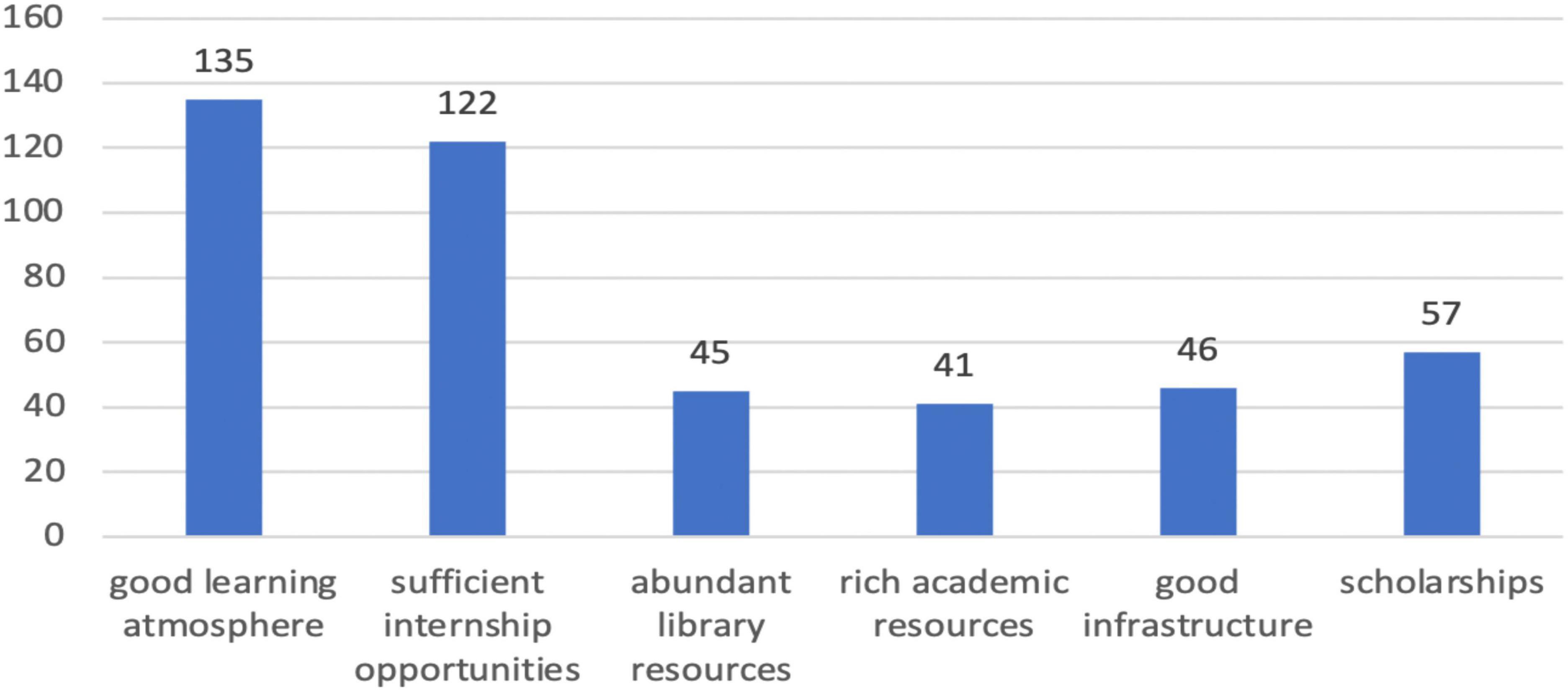

The affordances of the institution are demonstrated in Figure 4, which include a good learning atmosphere, sufficient internship opportunities, an abundant library, rich academic resources, top-class infrastructure, and scholarships. Among them, 135 participants regard a good learning atmosphere as the most vital factor behind their motivation; 122 participants think that sufficient internship opportunities are very essential in their motivation toward their language learning; 57 participants view scholarship as the crucial factor influencing their motivation. Moreover, 46 participants think that the world-class infrastructure provided by the institution affects their motivation for language learning most. Besides, 45 participants take abundant library resources as the most important factor behind their motivation, and 41 participants think rich academic resource influence their motivation most.

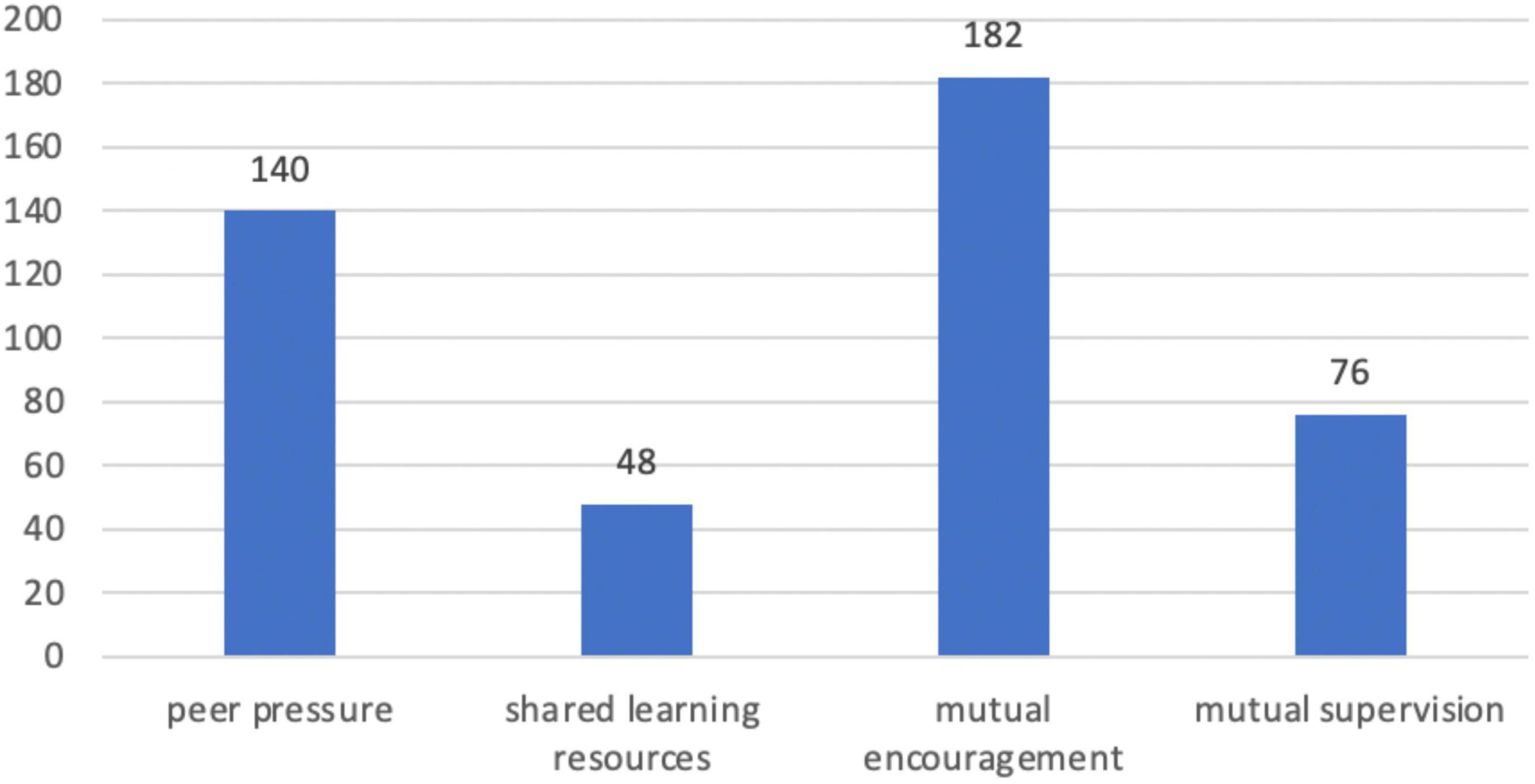

Figure 5 demonstrates the affordances of peers, which include peer pressure, shared learning resources, mutual encouragement, and supervision. 182 students believe that the importance of mutual encouragement ranks first in increasing their language learning motivation; 140 students think that peer pressure influences their motivation most; 76 students hold that mutual supervision is the most vital factor behind their motivation; 48 students believe that sharing learning resources is the most essential in increasing their learning motivation.

Figure 6 displays the comparison between these participants’ initial motivation and present motivation. It can be seen that job requirement is the motivation that changes most. At the beginning of their 2-year study, only about 50 participants further their studies because of job requirements, but now the number has increased to more than 300. In addition, such motivations as the pursuit of a better platform and self-improvement also changed a lot. At first, more than 100 participants choose to be postgraduates because of their pursuit of a better platform and more than 100 participants because of self-improvement, but now the number has become less than 50. In addition, the influence of passion and idols is also reduced. But the influence of peer pressure on participants’ motivation remains almost unchanged.

Qualitative descriptions: Perception and interpretation of the affordance inform the trajectory of motivation

While we found that the quantitative findings may provide the reader with a general picture of different types of affordances that affect language learning motivation, we also found them unable to capture how these affordances had different influences on language learning motivation. Therefore, we further interviewed six graduate students who majored in translation to explore the reasons behind them. The findings are as followed:

Mentor’s affordance on motivation

Here are parts of the interviews, which are about the participants’ opinions on the affordances of mentors.

L: “My mentor does a good job in academic life, which set a good example for me.”

E: “He publishes many papers every year. Thanks to this, I think it is not hard to publish academic papers, which increased my motivation.”

From the responses of participants L and E, we can see that a mentor with strong academic ability can set a good example for his/her students. Influenced by that, students will push themselves to move forward.

But it is not the full picture. Sometimes, students may not be affected by any mentor with strong academic ability and rich academic resources. Here are two examples.

Z: “She gave me some opportunities about the academic paper. But I just want to acquire a master’s degree, so paper is not a must. So, I refused her.”

From the answer of participant Z, we can see that although his mentor gave him a lot of academic resources, he didn’t take advantage of these resources and he just want to graduate with a satisfying job as soon as possible.

Therefore, it is found that a mentor’s strong academic ability and resources can exert a positive influence on students, but whether students will be influenced by that to study hard relies on the students themselves.

Besides mentors’ strong academic ability and rich academic resources, it is found that mentors’ care for students also exerts a profound effect on students’ motivation.

C: “She was very kind, she often cared about our lives, which warmed me a lot in my master’s study and gave me some motivation to study hard.”

W: “My tutor is easygoing in daily life except in the academic field, which makes me feel kind.”

From interviews with C and W, we can see that a kind and easygoing mentor can encourage her/his students to work hard. However, if the mentor has contact with students, students will feel ignored, which is evidenced by the response from participant N.

N: “My supervisor is busy with her life and she was seldom in contact with us. My postgraduate study is the same as my undergraduate life, which decreased my motivation.”

From N’s response, we can see that she has seldom contact with her mentor, which makes her lazy and feel hopeless, finally decreasing her motivation.

All in all, it is found that if mentors care about their students more, students will feel more motivated. Last but not least, being a strict mentor also has an influence on students’ motivation, but its influence is complex.

W: “He is very serious about academic standards, which helped me understand the importance of academic norms.”

L: “But she often criticized me for my paper, which demotivated me a lot. I just want to graduate as soon as possible.”

From the response of student W, we can see that the strict attitude of his mentor pushes him to learn more, which is motivation. But for student L, being strict exert a negative on her study, which ends up a demotivation.

In conclusion, the affordance of mentors is mainly from four respects: strong academic ability, rich academic resources, care for students, and being strict. Among them, care for students can always motivate students; a mentor with strong academic ability and rich academic resources can set an example for students, but it relies on students to decide whether they want to learn more; and what effect will being strict exert on students still relies on students.

Instructor’s affordance on motivation

Here are parts of the interviews, which are about the participants’ opinions on the affordances of instructors.

C: “Among the instructors, Professor Liu updated his knowledge in translation despite his big age. This spirit affects me a lot…”

N: “Although I have taken many courses, only a few courses aroused my interest. These courses are very useful in daily life…”

L: “Some instructors did a good job in teaching, which aroused my interest in learning…”

W: “Professor Yan affected me most, she made a wonderful syllabus and her serious attitude motivated me a lot…”

E: “Dr. Gao is a knowledgeable lecturer; he gave more information than the course itself. His course was very interesting and informative.”

From the interviews above, we can see that a serious and knowledgeable instructor and an informative and practical course can also benefit students and arouse their interest to acquire more knowledge. Therefore, in most cases, these affordances are what motivate students to learn. But there are some exceptions sometimes.

Z: “I just want to pass the exam to get the master’s degree. I hate the instructor that handed out too much homework…”

From the interview with student Z, we can see that even though the course is interesting and practical, he still chooses to be left unchecked because what he wants is nothing but a diploma.

In conclusion, it can be seen that the six affordances, namely, informative courses, being serious in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and reasonable course planning can always motivate students to acquire new knowledge in most cases.

Institution’s affordance on motivation

Here are parts of the interviews, which are about the participants’ opinions on the affordances of the institution.

C: “My university is a leader in maritime studies, and my mentor gave me some translation missions related to maritime. This made me feel that I did the front-line work in maritime research, which motivated me a lot…”

L: “My university is located in Beijing, which provided me with a wide range of volunteer activities, broadening my horizon and helping me better understand the translation major…”

W: “My graduate university is better than my undergraduate one. Students here are more diligent. The learning atmosphere is very good…”

1. E: “This university provides a better platform for me to apply for the Ph.D. study. In addition, it has the wonderful facilities to get access to the international journal for free…”

From the interview with students C, L, W, and E, we can see that their graduate university is better than their undergraduate university, which corresponds to one of their initial motivations: the pursuit of a better platform. And their graduate university provides them with more translation opportunities and professional knowledge, which has increased their motivation.

But in our interview, some students mentioned that they come to a better platform for a better job, not for more knowledge. The conversations are as follows.

N: “My graduate university is a 985 university. Many good companies come to my university to recruit students. It offered me a lot of opportunities to find a good job…”

Z: “It is a 211 university, it helped me get access to some specific jobs. This is the most important thing it provided…”

From the responses of students N and Z, we can see that at the beginning of their 2-year study, they decided to take advantage of their graduate university to find a better job. Therefore, the diploma is the most important thing for them, not language learning. As such, universities cannot exert any influence on their language learning.

In conclusion, it is found that the affordances of institutions, namely, good learning atmosphere, sufficient internship opportunities, abundant library resources, rich academic resources, good infrastructure, and scholarships are what motivate students to learn. For some students who already set a career goal that isn’t related to the English language, universities can give them affordance in finding a job, not language learning motivation.

Peer’s affordance on motivation

Here are parts of the interviews, which are about the participants’ opinions on the affordances of peers.

N: “My roommate is a nice girl, she encouraged me very often, so I have some motivation from her encouragement…”

L: “All my roommates are preparing for the civil service examination. They work very much and give me much pressure. I feel the need to work hard…”

From the interview with participants N, L, and E, we can see that peer pressure can motivate students to learn. When all the people around you are learning, you will feel it necessary to learn, which is a positive affordance for students.

But sometimes, students may become lazy because of the influence of their roommates.

C: “My roommate is not very active in studying, so when I go to the dorm, I feel very negative to study anything and just want to play games…”

W: “Most of my classmates just want to pass the exam, so there is not much pressure from the peer…”

From the responses of students C and W, we can see that they are affected by what their classmates and roommates think. If there is one student who doesn’t learn, he/she won’t learn as well, which damages his/her learning motivation.

But a few students don’t care what other students are doing at all and just pursue what they want.

E: “I want to get the national scholarship; therefore, I have to get a high rank in the school, and I have to do a better job than my peer, so the pressure from them motivated me a lot…”

Z: “I only want to meet the minimum requirement; it is very easy. And I don’t get the pressure from the peer, I just want to get the degree…”

Students E and Z are two kinds of students. Student E wants to get the scholarship; therefore, he studies hard to get a better score. It can be seen that for some students, scholarship is what motivates them to learn. But some students like Z have nothing to pursue. Therefore, passing the exam is their only expectation and they won’t feel peer pressure at all.

In conclusion, we can see that most students will be influenced by their peers. If their roommates are diligent, they will try to learn more; if their roommates play games all day, they will lack interest in studying as well. But a few students won’t be influenced by their surroundings as they clearly know what they want. If what they want is directly related to language learning, it will be a motivation; otherwise, a demotivation.

Discussion

The types of affordances are complex

In this study, we found that the types of affordances themselves are complex. First, the origin of affordance is complex, including mentors, instructors, institutions, and peer pressure. Second, each affordance is complex as well, including several respects at the same time. The affordances of mentors are mainly from mentors’ strong academic ability, rich academic resources, care for students, and strict attitude. The affordances of instructors are mainly from informative courses, teachers’ serious attitudes in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and reasonable course planning. The affordances of institutions are mainly from a good learning atmosphere, sufficient internship opportunities, abundant library resources, rich academic resources, good infrastructures, and scholarships. The affordances of the peer are mainly from peer pressure, shared learning resources, mutual encouragement, and mutual supervision.

Non-linearity: The motivation changed a lot during the 2-year study

From the comparison between these participants’ initial motivation and present motivation, we saw that their language motivation changed greatly during their 2-year study. The language motivation that changed most is job requirements. At the beginning of their 2-year study, only one-ninth of participants further their studies because of it, but now the number has increased to more than three-fourths. In addition, such motivations as a better platform and self-improvement also changed a lot. The number of participants pursuing a better platform and self-improvement decreased rapidly. In addition, the influence of passion and idols is also reduced. But the influence of peer pressure on participants’ language learning motivation remains almost unchanged.

Different interpretations of the affordance lead to different language learning motivation

In terms of the affordances of mentors, a mentor with strong academic ability and rich academic resources can set a good example for his/her students and increase their language learning motivation (Fayram et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2019). But whether it can motivate students relies on students themselves.

In terms of the affordance from instructors, informative courses, being serious in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and reasonable course planning can always motivate students to acquire new knowledge in most cases (Klímová and Poulová, 2015; Yang and Wyatt, 2021). But for some students who choose to be left unchecked, instructors cannot motivate them at all.

In terms of the affordance of institutions, they provided students with a good learning atmosphere and rich academic resources to increase their language learning motivation. However, for some students who already set a career goal that isn’t related to the English language, the affordances of the institution cannot increase their language learning motivation.

In terms of the affordance of peers, most students will be influenced by their peers (Arnándiz et al., 2022; Weng et al., 2022). They will finally become what their roommates are. But a few students won’t be influenced by their surroundings as they clearly know what they want. If what they want is directly related to language learning, it will be a motivation; otherwise, a demotivation.

Affordance has little influence on the intrinsic motivation

The affordances of the mentors and instructors provided what the translation students need if they pursue their cancer in the translator. However, some students just want to get a master’s degree to find a job that is unrelated to translation, so they just followed the minimum standard in the 2-year study. On this very note, the affordances of the mentor and instructors cannot have much effect on their language learning motivation (Li et al., 2020).

Conclusion

In this paper, we combined questionnaires and interviews to explore what types of affordances of the mentors, instructors, peers, and institutions affect language learning motivation and how they affect the change of motivation. Findings from the questionnaires showed that the affordances of the mentor can be divided into strong academic ability, rich academic resources, caring students, and strict requests; affordances of the instructor can be divided into informative courses, being serious in class, strong teaching ability, practical courses, new teaching methods, and the reasonable course planning; affordances of the peer can be divided into peer pressure, shared learning resources, mutual encouragement and mutual supervision. Affordances of the institution can be divided into a good learning atmosphere, sufficient internship opportunities, abundant library resources, good infrastructure, and scholarships. Findings from the iuccessive developmental phasenterview showed that different interpretations of affordances lead to different effects on language learning motivation; affordance has little influence on intrinsic language learning motivation.

But our paper also has some limitations. First, the number of participants is small, which cannot represent the whole picture. Second, the participants are restricted to several universities, and students from some top universities in the translation field like Beijing Foreign Studies University and Shanghai International Studies University are not included in our questionnaires.

In the future, we hope that more participants from different universities could participate in this research so as to show the whole picture. If possible, we also expect that more students from other countries can participate in this research so as to show how it is in other countries. In addition, we found that job requirements exert a huge effect on students’ motivation at the end of their 2-year studies. Therefore, we hope to further explore how job requirements influence students’ motivation.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The ethical review and approval were not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

XW contributed to the overall design, organization, and logic of the manuscript. FS contributed to the data analysis and manuscript writing. QW and XL were responsible for data collection. All authors contributed to the drafting and proofreading of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akdağ, A. I. (2019). Improving motivation in translator training: Achievement goal orientations of translation studies students. Selçuk Üniv. Edebiyat Fakültesi Derg. 41, 1–14.

Ali, Z. (2022). Investigating the intrinsic motivation among second language learners, in using digital learning platforms during the Covid-19 pandemic. Arab World Engl. J. 2022, 437–452. doi: 10.24093/awej/covid2.29

Allen, H. (2010). Interactive contact as linguistic affordance during short-term study abroad: myth or reality? Front. Interdiscipl. J. Study Abroad 19:271. doi: 10.36366/frontiers.v19i1.271

Arnándiz, O. M., Moliner, L., and Alegre, F. (2022). When CLIL is for all: Improving learner motivation through peer-tutoring in Mathematics. System 106:102773. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2022.102773

Aronin, L., Fishman, J., Singleton, D., and Ó Laoire, M. (2013). “Current multilingualism: A new linguistic dispensation,” in Current Multilingualism: A New Linguistic Dispensation, eds D. Singleton, J. Fishman, L. Aronin, and M. Ó Laoire (Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton), 3–24. doi: 10.1515/9781614512813.3

Aronin, L., and Singleton, D. (2010). Affordances and the diversity of multilingualism. Int. J. Sociol. Lang. 2010, 105–129. doi: 10.1515/ijsl.2010.041

Bower, K. (2019). Explaining motivation in language learning: a framework for evaluation and research. Lang. Learn. J. 47, 558–574. doi: 10.1080/09571736.2017.1321035

Cheng, X., and Wu, L. Y. (2016). The affordances of teacher professional learning communities: A case study of a Chinese secondary school. Teach. Teach. Educ. 58, 54–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.04.008

Cotterall, S., and Murray, G. (2009). Enhancing metacognitive knowledge: Structure, affordances and self. System 37, 34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2008.08.003

Crystal, D. (2008). Towards a philosophy of language management. Latin Am. J. Content Lang. Integr. Learn. 1, 43–53. doi: 10.5294/laclil.2008.1.1.5

Dalgarno, B., and Lee, M. J. (2010). What are the learning affordances of 3−D virtual environments? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 41, 10–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01038.x

De Bot, K., Lowie, W., and Verspoor, M. (2007). A dynamic systems theory approach to second language acquisition. Bilingualism 10, 7–21. doi: 10.1017/S1366728906002732

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Pers. 19, 109–134.

Dörnyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second language motivation research. Ann. Rev. Appl. Linguist. 21, 43–59. doi: 10.1017/S0267190501000034

Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. Motiv. Lang. Ident. L2 Self 36, 9–11. doi: 10.21832/9781847691293-003

Dörnyei, Z., and Csizér, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Appl. Linguist. 23, 421–462. doi: 10.1093/applin/23.4.421

Dörnyei, Z., and Csizér, K. (2005). The effects of intercultural contact and tourism on language attitudes and language learning motivation. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 24, 327–357. doi: 10.1177/0261927X05281424

Fayram, J., Boswood, N., Kan, Q., Motzo, A., and Proudfoot, A. (2018). Investigating the benefits of online peer mentoring for student confidence and motivation. Int. J. Mentor. Coach. Educ 7, 312–328. doi: 10.1108/IJMCE-10-2017-0065

Gao, Y. (2021). How do language learning, teaching, and transnational experiences (Re) shape an EFLer’s identities? A critical ethnographic narrative. SAGE Open 11:21582440211031211. doi: 10.1177/21582440211031211

Gao, Y., Zeng, G., Wang, Y., Khan, A. A., and Wang, X. (2022). Exploring educational planning, teacher beliefs, and teacher practices during the pandemic: a study of science and technology-based universities in China. Front. Psychol.:2322. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903244

Gao, Y., and Zhou, Y. (2021). Exploring language teachers’ beliefs about the medium of instruction and actual practices using complex dynamic system theory. Front. Educ. 6:708031. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.708031

García, L. D. M. (2020). Researching the motivation of Spanish to Chinese fansubbers: A case study on collaborative translation in China. Transl. Cogn. Behav. 3, 165–187. doi: 10.1075/tcb.00039.mor

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C., and Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second-language acquisition. Can. J. Psychol. 13, 266–272. doi: 10.1037/h0083787

Gardner, R. C., and Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and Motivation in Second-Language Learning. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A. M., Tennant, J., and Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: Changes during a year−long intermediate−level language course. Lang. Learn. 54, 1–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00247.x

Gibson, J. G. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Hawkins, M. R. (2004). Researching English language and literacy development in schools. Educ. Res. 33, 14–25. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033003014

Hiver, P., and Larsen-Freeman, D. (2019). “Motivation: It is a relational system,” in Contemporary language motivation theory: 60 years since Gardner and Lambert, eds P. D. MacIntyre and A. H. Al-Hoorie (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 285.

Jabu, B., and Abduh, A. (2021). Motivation and challenges of trainee translators participating in translation training. Int. J. Lang. Educ. 5, 490–500. doi: 10.26858/ijole.v5i1.19625

Jiao, S., Wang, J., Ma, X., You, Z., and Jiang, D. (2022). Motivation and Its Impact on Language Achievement: Sustainable Development of Ethnic Minority Students’. Sec. Lang. Learn. Sustain. 14:7898. doi: 10.3390/su14137898

Klímová, B. F., and Poulová, P. (2015). “The role of ICT in raising student’s motivation to learn English as a foreign language: Two case studies,” in Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on E-Learning (ECEL) Conference Hatfield, (San Diego, CA: ACAD), 293–298.

Kramsch, C. (2000). Second language acquisition, applied linguistics, and the teaching of foreign languages. Modern Lang. J. 84, 311–326. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00071

Kühl, T., and Wohninsland, P. (2022). Learning with the interactive whiteboard in the classroom: Its impact on vocabulary acquisition, motivation and the role of foreign language anxiety. Educ. Inform. Technol. 27, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11004-9

Larsen-Freeman, D., and Cameron, L. (2008). Complex Systems and Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Larsen–Freeman, D. I. A. N. E. (2019). On language learner agency: A complex dynamic system theory perspective. Mod. Lang. J. 103, 61–79.

Li, L., Gao, F., and Guo, S. (2020). The effects of social messaging on students’ learning and intrinsic motivation in peer assessment. J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 36, 439–448. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12409

Lin, Z., Wu, B., Wang, F., and Yang, D. (2019). Enhancing student teacher motivation through mentor feedback on practicum reports: a case study. J. Educ. Teach. 45, 605–607. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2019.1675355

Locke, E. A., and Latham, G. P. (1990). Work motivation and satisfaction: Light at the end of the tunnel. Psychol. Sci. 1, 240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1990.tb00207.x

Lowie, W., Verspoor, M., and van Dijk, M. (2018). The acquisition of L2 speaking. Speak. Sec. Lang. 17, 105. doi: 10.1075/aals.17.05low

McNeil, J. D. (2014). Contemporary Curriculum: In Thought and Action. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Murray, G., and Fujishima, N. (2013). Social language learning spaces: Affordances in a community of learners. Chin. J. Appl. Linguist. 36, 141–157. doi: 10.1515/cjal-2013-0009

Pan, C., and Zhang, X. (2021). A longitudinal study of foreign language anxiety and enjoyment. Lang. Teach. Res. 8, 1–24. doi: 10.1177/1362168821993341

Papi, M., and Hiver, P. (2020). Language learning motivation as a complex dynamic system: A global perspective of truth, control, and value. Modern Lang. J. 104, 209–232. doi: 10.1111/modl.12624

Park, J. H. (2017). Syntactic Complexity as a Predictor of Second Language Writing Proficiency and Writing Quality. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University.

Peng, J. E. (2011). Changes in language learning beliefs during a transition to tertiary study: The mediation of classroom affordances. System 39, 314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2011.07.004

Polat, B., and Kim, Y. (2014). Dynamics of complexity and accuracy: A longitudinal case study of advanced untutored development. Appl. Linguist. 35, 184–207. doi: 10.1093/applin/amt013

Qin, L., and Dai, W. (2015). Investigating affordances in college english learning environment from an ecological perspective. Modern Foreign Lang. 38, 227–237.

Robertson, J. (2011). The educational affordances of blogs for self-directed learning. Comp. Educ. 57, 1628–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.03.003

Thompson, A. S. (2017). Don’t tell me what to do! The anti-ought-to self and language learning motivation. System 67, 38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2017.04.004

Tseng, W. T., and Schmitt, N. (2008). Toward a model of motivated vocabulary learning: A structural equation modeling approach. Lang. Learn. 58, 357–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2008.00444.x

Van Lier, L. (2000). From input to affordance: Social-interactive learning from an ecological perspective. Sociocult. Theor. Sec. Lang. Learn. 78, 245.

Veletsianos, G., and Navarrete, C. (2012). Online social networks as formal learning environments: Learner experiences and activities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distr. Learn. 13, 144–166. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1078

Verspoor, M. (2017). “Complex dynamic systems theory and L2 pedagogy,” in Complexity Theory and Language Development: In Celebration of Diane Larsen-Freeman, eds L. Ortega and H. ZhaoHong (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 143–162. doi: 10.1075/lllt.48.08ver

Waninge, F., Dörnyei, Z., and De Bot, K. (2014). Motivational dynamics in language learning: Change, stability, and context. Modern Lang. J. 98, 704–723. doi: 10.1111/modl.12118

Webb, M. E. (2005). Affordances of ICT in science learning: implications for an integrated pedagogy. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 27, 705–735. doi: 10.1080/09500690500038520

Weng, F., Ye, S. X., and Xue, W. (2022). The effects of peer feedback on L2 Students’ writing motivation: An experimental study in China. Asia-Pacific Educ. Res. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40299-022-00669-y

Wigfield, A., and Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 68–81. doi: 10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Yang, X., and Wyatt, M. (2021). English for specific purposes teachers’ beliefs about their motivational practices and student motivation at a Chinese university. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 11, 41–70. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.1.3

Yashima, T., and Arano, K. (2015). “Understanding EFL learners’ motivational dynamics: A three-level model from a dynamic systems and sociocultural perspective,” in Motivational Dynamics in Language Learning, eds Z. Dörnyei, A. Henry, and P. D. MacIntyre (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 285–314

Zheng, Y. (2019). The CDST perspective on effective foreign language teaching. Contemp. Foreign Lang. Stud. 19, 12–16.

Zheng, Y., Lu, X., and Ren, W. (2020). Tracking the evolution of Chinese learners’ multilingual motivation through a longitudinal Q methodology. Modern Lang. J. 104, 781–803. doi: 10.1111/modl.12672

Keywords: language learning motivation, affordance, translation students, Chinese context, MTI program

Citation: Wang X, Sun F, Wang Q and Li X (2022) Motivation and affordance: A study of graduate students majoring in translation in China. Front. Educ. 7:1010889. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1010889

Received: 03 August 2022; Accepted: 07 September 2022;

Published: 20 October 2022.

Edited by:

Alfred Kweku Ampah-Mensah, University of Cape Coast, GhanaReviewed by:

Mubarak Alkhatnai, King Saud University, Saudi ArabiaMorshed Al-Jaro, Seiyun University, Yemen

Copyright © 2022 Wang, Sun, Wang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaochen Wang, d2FuZ3hpYW9jaGVuNjY2NjY2QG91dGxvb2suY29t; Fei Sun, c3VuZmVpXzk4QHRqdS5lZHUuY24=

Xiaochen Wang

Xiaochen Wang Fei Sun

Fei Sun Qikai Wang

Qikai Wang Xinyu Li

Xinyu Li