- Department of Teaching and Learning, Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ, United States

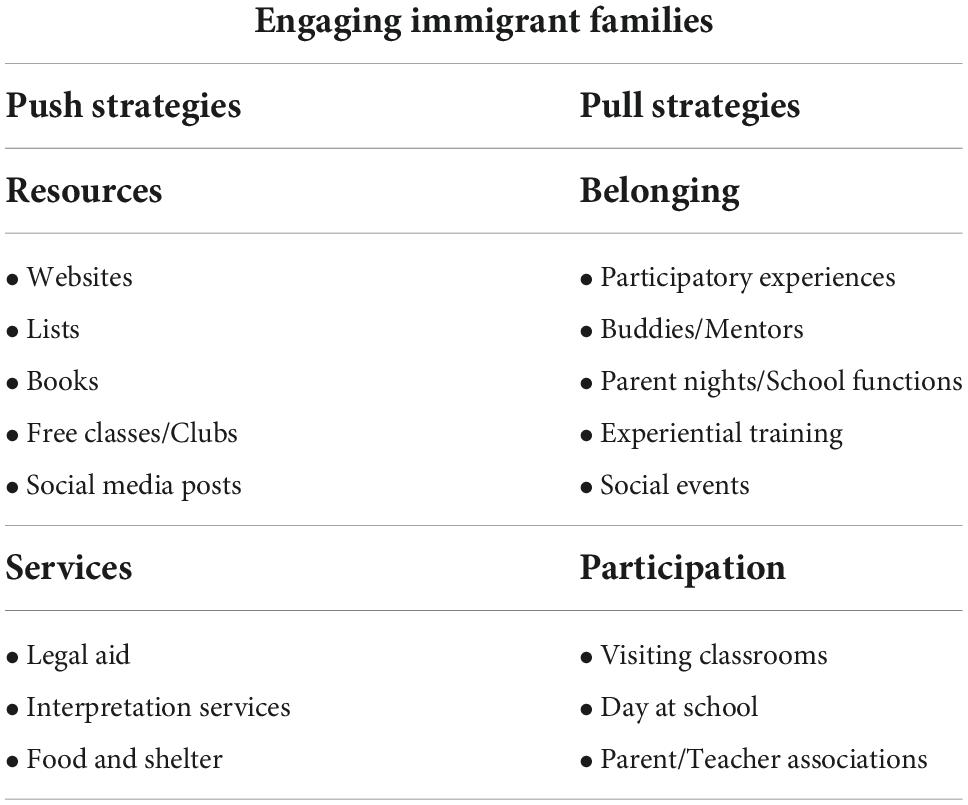

More than one million immigrants arrive in the United States each year. The diversity of languages and cultures brought by immigrants makes America a more multicultural and inclusive nation, but also presents some challenges as immigrants engage in their socialization process. Schools play a central role in acculturating immigrant families and their children, and they serve as mediators of the relationships between these families and the larger society. This article describes a project in a school district in New Jersey that focuses on integrating immigrant families in the community. The framework we developed includes a number of strategies that were grouped into two categories: “push” and “pull.” Push strategies refer to the strategies developed by the school to offer families resources and connect them to an array of services that assist immigrants. Pull strategies focus on bringing families from the community to the school building and creating mechanisms to include them in both curricular and extra-curricular activities to strengthen their sense of belonging and identity.

Introduction

According to data from the Pew Research Center, more than one million immigrants arrive in the United States each year (Budiman, 2020). This immigrant population is very diverse, and almost every country in the world is represented among US immigrants. The diversity of immigrants is also represented in the number of languages spoken and the cultures that are present in different communities across the US once these immigrants become part of the American society. The diversity brought by immigrants presents both opportunities and challenges for many communities. The opportunities are usually reflected in terms of the contributions these immigrants make to the American society, such as diversifying the work force by bringing new skills, new ways of thinking and solving problems, and ultimately increasing economic growth, as well as adding aspects of their culture to make America more multicultural. Immigrants contribute to the development of the arts, music, literature, cuisine, among others, and help society become more open, inclusive, and integrated. The challenges immigration brings are mostly associated with aspects of social life, particularly in areas where people see immigrants as a threat to their language, culture, status quo, and identity.

Schools are always at the center of every discussion on immigration. This is because they serve as acculturation centers where children and their families go through language and culture socialization processes. While schools represent the official knowledge of a society (Apple, 2014), they also serve as the place where diversity is authentically experienced by all stakeholders (Ladson-Billings, 2011). As students, teachers, families, and school personnel interact and engage in various pedagogical processes, they also get to know one another and learn from everyone’s backgrounds and lived experiences.

In this article, I describe part of a project in a school district in New Jersey that focuses on integrating immigrant families in the community and including their voices and histories as part of the school curricula. Apart from working with the teachers and school personnel to prepare them to understand and address the needs of immigrant students and English Learners (ELs), one of our main concerns was to design effective strategies to work directly with immigrant families to support their socialization and acculturation processes while also learning from them and using their knowledge as part of the work being done in the schools through curricular and extra-curricular activities.

Immigration is a human right and humans have always been on the move. The many and different reasons that lead people to begin an immigration journey need to be understood as a human’s basic rights to life with opportunity, dignity, equality, inclusion, security, stability, and respect. Leaving one’s homeland can be a hard but necessary decision. Immigration is part of life and the history of humankind. Yet, the discourse surrounding immigration has always been filled with discriminatory, xenophobic, and ignorant arguments that aim to deny people of this basic right.

What is not mentioned in the anti-immigration discourse is that immigration translates into growth and progress. The United States is a nation of immigrants. It has been enriched by the innumerable contributions of its immigrants and the nation is stronger because of their presence. In the work described in this article, we focus on the kinds of support systems that a school and its community can develop to integrate immigrants in the larger society. School communities, while socializing agents, are also incredibly strengthened by welcoming immigrants and inviting their contributions to enhance the educational experiences of all community members.

Background

Immigrating to a new country implies going through a process of socialization. Immigrants go through a series of steps and actions while learning how to act in socially acceptable ways and function based on the norms and values established by their host country.

Little (2016) describes socialization as “the process through which people are taught to be proficient members of a society. It describes the ways that people come to understand societal norms and expectations, to accept society’s beliefs, and to be aware of societal values. It also describes the way people come to be aware of themselves and to reflect on the suitability of their behavior in their interactions with others” (p. 205). Little (2016) goes on to further describe socialization as the way that people learn to play different roles in their lives. This means that roles such as being a man or a woman, a son or a daughter, a teacher or a student, a parent or an administrator are also learned socially and that their meanings and representations will vary depending on the norms and expectations of the society in which we grow up.

When it comes to the life of an immigrant, we can say that they are in fact re-socializing. Robertson (1987) describes four processes people go through in their lives as they socialize to gain membership in different groups: primary socialization, anticipatory socialization, developmental socialization, and re-socialization. Primary socialization is the most basic of the four types, as it means learning and internalizing the norms of the society in which we are born and grow up. The first social group that we belong to is our families and, therefore, the primary socialization occurs within the sphere of family and the close community within which our families circulate. The next step, the anticipatory socialization, occurs when we start navigating new territories and exploring new social groups with the expectation (or anticipation) of joining these groups. This process goes along with developmental socialization which is basically a continuation of the primary and anticipatory processes of socialization. Primary socialization occurs in the early years of life when we are still growing up, forming our identities, and developing a sense of belonging in our families and immediate communities. As we enter adult life, we build on this initial socialization process to develop new skills and knowledge as we navigate new aspects of our life, such as our professional field, new family, and social circles (spouses, partners, co-workers, friends, and acquaintances), and even our participation in social, religious, and sports organizations or activities. These new spheres reflect the roles described by Little (2016). Becoming an adult, gaining more responsibility, getting a job, becoming a spouse and a parent are all roles that come with different expectations and norms that we add on to our socialization repertoire. Finally, re-socialization refers to a process of change or substitution of membership. Many times, in life, because of different circumstances, people need to move or migrate, and this causes a radical shift in their lives. This shift in their life circumstances is accompanied by a shift in perspective. Immigrants need to learn and understand new ways of thinking and acting and new norms, patterns, and values.

Immigrating to a new country means going through the process of re-socialization. You are basically starting over, learning new roles, attitudes, and beliefs, as you claim membership in a new society which may be completely different from the one you know and have lived all your life. It is important to mention, though, that while the concept of re-socialization may sound like a remaking of individuals, I prefer to see it as adding another layer of complexity to these individuals, as they figure out who they are in this new society. Re-socializing does not mean abandoning who you are but adding new markers to an existing identity. It should be understood as an additive (as opposed to a subtractive) process. It is ultimately up to the immigrants to determine how this process will affect their identities.

Apart from socializing into the norms and expectations of the new society in terms of actions and behaviors, immigrants also go through a language socialization process. The field of language socialization examines the relationships between language and culture to understand how communicative practices are defined and enacted within a society and how speakers learn to engage in these practices.

Ochs and Schieffelin (2017) describe how language development is dependent upon a child’s early interactions in life and the kinds of linguistic input, types of language and forms of discourses they are exposed to growing up. Immigrants also go through a process of language socialization in their new society. As much as they may want to preserve their linguistic practices, they will also be required to learn new practices and ways of communicating if they truly want to integrate into the life of a community. Once again, for the children of immigrants, schools operate as the mediator of the cultural and linguistic socialization processes, after all, as I have described before, “schools serve as the bastions of a society, as they uphold the principles, the attitudes, the values and the history of a nation and are tasked with socializing the youth into life in the larger society. In this sense, schools are also gatekeepers for they provide access to knowledge and attending school can translate into acceptance and opportunity for its students” (Naiditch, 2021a, p. 3).

Schools provide access to the linguistic and cultural systems of a nation and opportunities for students to engage in communicative practices that will empower and prepare them to become fluent members of the speech community. Ochs and Schieffelin (2017) argue that “language socialization transpires whenever there is an asymmetry in knowledge and power and characterizes our human interactions throughout adulthood as we become socialized into novel activities, identities, and objects relevant to work, family, recreation, civic, religious, and other environments in increasingly globalized communities” (p. 9).

Language, after all, as Sapir (1933/1958) claimed “is a great force of socialization, probably the greatest that exists” (as quoted in Mandelbaum, 1958, p. 15). In fact, learning to communicate meanings and understand messages is a culturally embedded activity and it is one way for immigrants to claim membership in a speech community. As they become more competent at using English and start adhering to the communicative rules established by local language users, they position themselves as capable participants of that community. Language socialization, thus, also results in social competence. Learning the ways of talking and listening in common communicative activities of a community enhances and promotes the social engagement of immigrant families. This is what Ochs and Schieffelin (2014) refer to as “becoming speakers of cultures” (p. 7).

If children can rely on schools to support their socialization process, how about adult immigrants, parents who are not at school age, but still need to socialize into new cultural norms, and linguistic rules? Adult immigrants, unlike children, may need to purposefully search for opportunities to engage in communicative events with people from the community if they want to learn the appropriate cultural and linguistic norms that govern conversations. These norms are unwritten rules that dictate how people exchange ideas, interact with each other, ask and answer questions, share information, take turns, begin and end conversations, and use non-verbal communication, for example. Immigrants can learn these norms as they socialize through different venues–work, classes, shopping, moving around the community, etc., but they may not have as many opportunities as their children to engage in meaningful interactions.

The process of socialization is dependent upon opportunities to integrate in the life of the new society and access to conversational partners who are members of that speech community. Therefore, it can become complicated or problematic, particularly for adult immigrants and parents who, many times, may depend upon the availability of community members to be given access to the speech community. These community members are, in general, native speakers who need to be willing to include immigrants in their social circles and to position them as equally competent interlocutors. For that reason, engaging in the socialization process, both culturally and linguistically, does not always depend on the immigrants themselves. Community members (native speakers and dominant groups) can regulate the socialization process of immigrants by acting as gatekeepers: they establish the norms and control access to opportunity and participation.

There are different reasons why people migrate, but often, immigration is a result of people searching for a better life whether it means greater economic opportunity, religious freedom, freedom of expression, or even for the right to exist, and be who they are. When immigrants are welcomed and supported, they will thrive in their new environment and will participate and contribute to their adopted communities.

From its earliest days, America has been a nation of immigrants and immigration is central to the spirit of American democracy: it is what makes this nation what it is. It is not only a fundamental aspect of human history, but also an issue of human rights, survival, and social justice.

Undoubtedly, immigration is also a controversial issue from many points of view–whether it is a political, social, economic, or humanitarian issue, there is always disagreement when it comes to the role of immigration in the fabric of American society. In American history, the influx of newcomers has always resulted in anti-immigrant sentiment among certain factions of America. But one thing has never changed: immigration is still part of life in the 21st century and due to war, climate change, poverty, political and social unrest, economic instability, food insecurity, humanitarian refuge, among many other factors, immigration will continue to be at the center of every debate about life in society. Whatever the reason that brought immigrants to our communities, it is our responsibility to support these families and to ensure as smooth a transition as possible to life in the United States.

Learning to work with immigrant families is a necessary and essential aspect of teacher preparation in the US as well as the preparation of all school personnel who are tasked with not only welcoming these families into the school building, but also helping them navigate complex bureaucratic processes and understand the principles and practices that base the work developed in schools.

Schools need to prepare their staff to relate to and respond to people that come from every culture and background and this means developing culturally responsive practices in all aspects of the work. Whether it is in the classroom through culturally and linguistically responsive teaching (Naiditch, 2021b) or in providing services and assistance in culturally appropriate ways, the need to be adequately prepared to work with immigrants includes developing an understanding of the complex issues involved in immigration, knowledge of the specific services and many times, even interventions that immigrant families may need.

In order to fit in and develop a sense of belonging, many immigrant families believe that they need to assimilate so they can be seen as equal partners. This pressure to “Americanize” is understood given our human nature to belong. However, assimilation is not the goal of multicultural societies like ours and we do not want these immigrant families to forget or abandon who they are, which is their identities. On the contrary, we want them to maintain their culture, language, customs, and bring them to light so we can learn from them and include their histories as part of our work. Assimilation is a word that is not part of our work at all. In fact, as Alba and Nee (2005) have rightfully described, assimilation is a contested idea, “an ethnocentric and patronizing imposition on minority peoples struggling to retain their cultural and ethnic integrity” (p. 1).

Working with immigrant families, therefore, many times means walking a fine line between what we expect from these families and what they expect from us. The American Psychological Association (APA) describes the process experienced by immigrants as acculturation, which may seem more appropriate for the kind of work that we do. As the association describes it, “acculturation, a multidimensional process, involves changes in many aspects of immigrants’ lives, including language, cultural and ethnic identity, attitudes and values, social customs and relations, gender roles, types of food and music preferred, and media use” (American Psychological Association [APA], and Presidential Task Force on Immigration, 2012, p. 2). The APA distinguishes between psychological acculturation (which refers to the immigrant adapting to the new culture) and behavioral acculturation (which refers to the extent to which immigrants participate both in the new culture and their culture of origin).

In this view, acculturation takes place in stages and immigrants engage in a learning process to systematically acquire the knowledge and the skills needed to navigate life in the new society. This includes learning the language and culture of the host country without losing their own: “while some settings, such as workplaces or schools, are predominantly culturally American, others, such as an immigrant’s ethnic neighborhood and home environment, may be predominantly of the heritage culture. From this perspective, acculturation to both cultures provides access to different kinds of resources that are useful in different settings and is linked, it is hoped, to positive mental health outcomes” (American Psychological Association [APA], and Presidential Task Force on Immigration, 2012, p. 2).

This is an essential aspect of the work we do–connecting families with their own immigrant communities and to resources within those communities. In every city in America, you will find ethnic enclaves (Edin et al., 2003) and these communities serve as support systems for immigrants by assisting them with jobs, making connections, and creating various opportunities (Munshi, 2003; Beaman, 2012). They can also serve as a third space (Bhabha, 1994) for immigrants who can find a place where people share their language, culture, cuisine, and customs. These networks created by immigrants for immigrants in ethnic enclaves are, ultimately, structured systems of self-organization that focus on survival and protection for immigrants.

In our work, we want to convey to these immigrant families that we want them to maintain their integrity without losing the essence of who they are and without forgetting where they came from while learning how to navigate the American legal, social, economic, educational, and health systems in ways that allow them to benefit from the services and support systems in place to help them integrate in society. Schools serve as mediators of these relationships between families and services. While we strive not to create any loss of identity for these families, we also understand that socialization and acculturation require adjustments and adaptations.

Immigration is a dynamic process that does not end when a family arrives in a new country. Immigration is an ongoing movement and for many families who embark on this journey, they may feel that they are still immigrating, even after years of being in a new land.

The project

The work described in this article is part of a large professional development project developed in a school district in the state of New Jersey. While the project focused on teacher preparation and development, we quickly realized the need to also work with immigrant students’ families and create mechanisms to support their socialization process, particularly as they learned to navigate complex bureaucratic structures, new cultural ways of doing business, and a new language.

While considering how to integrate immigrant families in the community and the schools their children would be attending, our main aim was to create the necessary conditions for these families to be welcomed in their new country while supporting their acclimation, acculturation, and socialization processes. This included working within the school building, but also moving beyond the four walls of the school and reaching out to the community by fostering relationships and embedding immigrant families in the life and fabric of the larger society.

This was a collaborative project which included all stakeholders–the university researcher, the school staff, parents, community members, and the immigrant families. Studies that focus on pedagogy and education in school settings usually focus on teachers and students, but because this was a participatory and community-based project, we engaged all school community in the activities and in all the steps taken as the work was being planned and developed.

In the larger research project (see Naiditch, 2021a for a detailed description of the study), practitioner action research was used as both the data gathering technique and the method of inquiry to engage all stakeholders to examine our practice critically and to improve it (Anderson et al., 2007). Because the work was done mostly in the classrooms and school buildings and it involved mainly educators, we focused on practitioner action research: the work developed by teachers who were engaged in a systematic, careful, and critical examination of their practice.

For this part of the project, we are considering and including more participants, both inside and outside the school building and, therefore, we are using the acronym PAR to refer to participatory action research (PAR). Action research is a participatory form of inquiry, which can be conducted by an individual or a group of people who intend to advance their practice. The different types of action research reflect the purposes and the participants involved: “a plan of research can involve a single teacher investigating an issue in his or her classroom, a group of teachers working on a common problem, or a team of teachers and others focusing on a school- or district-wide issue” (Ferrance, 2000, p. 3). Often associated with research done by teachers looking to improve their pedagogy, PAR can also involve the whole school building and beyond, as in the case of this particular project.

For this project, we wanted to involve the larger community and combine the collective knowledge of all participants to affect change in the way schools represent and are represented by their communities to provide services and practices that facilitate the integration of immigrant families as new members in the community. PAR requires all people involved in the project to engage in a collaborative inquiry process while implementing the strategies to support immigrant families. PAR allows us to regularly reflect on our strategies and activities by assessing, reassessing and transforming them. Because PAR is a systematic and developmental tool which allows participants to engage in a critical analysis of their practices by identifying aspects that need to be changed and improved, it results in professional and organizational learning that adds to our repertoire of best practices.

By strengthening the relationship between inquiry and action, PAR allows participants to better understand how to plan, create and implement more equitable actions within the school building (Anderson and Herr, 2009). Because it is done in cycles, PAR allows us to reflect on the activities and practices planned and act in order to improve them and make them more effective to meet the needs of our school community.

In this article, we focus on the framework to be implemented in the school building where the project originated. Because this particular aspect of the project is part of a larger study which focuses on preparing teachers and school personnel to understand and address the needs of immigrant students and ELs, it is essential to understand that there are multiple parts to it and, in the next section, we describe our vision–the way we created, planned, developed, and will implement different strategies to facilitate the socialization process of immigrant families in the school and the larger community. It is important to highlight here that this is a process that is relatively new and ongoing and that we are still working on implementing the project as immigrant families arrive in the community and as we develop new strategies and collaborations. Because of its cyclical nature, PAR will allow us to study our strategies and assess, revise and restructure the work concomitantly, as we search for better alternatives and more effective strategies and practices.

Not all the activities listed and described in this paper have been implemented due in part to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic which interrupted much of the in-person work being developed and moved everyone to a virtual reality that prevented us from fully developing the project. Unfortunately, the global pandemic had a severe impact on immigrant communities which usually already have fewer resources, less access to the internet and are still developing their digital literacy. Therefore, as we discuss our framework, we focus on the kind of work that is yet to come, the rationale for developing it and the likely positive effects it can have on the acculturation and socialization processes of immigrant families starting new lives in our community.

The framework

According to data from the United States Census Bureau (2019), immigrants represent 13.7% of the total population in the United States. These numbers only tend to grow and, as a result, schools today see their student population becoming more culturally and linguistically diverse. Children born to immigrant parents are growing up in a more diverse America, not only in terms of culture and language. As society evolves, we see more inclusive expressions of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, education levels, and beliefs, which are also reflected in the political and socioeconomic aspects of life in society. Immigrant families and their children also tend to be in a more vulnerable socio-economic situation when compared to US-born citizens (Hernandez and Charney, 1998). They are more likely to experience economic hardship, which translates into instability and insecurity when it comes to attending to basic needs, such as food and shelter as well as finding work and caring for their health and emotional wellbeing. This, in turn, may affect their children’s development and their physical and socio-emotional health. The adversities experienced by immigrant families will also be seen in many aspects of the school life–children’s ability to attend school regularly, focus on their studies, form relationships, and, ultimately, succeed academically.

Immigrating is not an easy decision for any family. The process of uprooting and resettlement involves many steps and can affect a family for generations to come. Acclimating and adjusting to a new reality are processes that need to be supported and scaffolded. Among the many challenges immigrants experience, there is access to services, opportunities to socialize and integrate in the new society, as well as linguistic and cultural barriers that may prevent them from communicating their needs and understanding the norms they are now expected to follow. Immigrants need assistance on many levels, from fulfilling the most basic human needs to caring for their welfare.

A closer look at Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of needs helped us understand the necessary strategies we had to develop in order to not only bring these families to work with us in the schools, but to ensure that their needs were being met and that they felt comfortable enough, so they could feel a sense of belonging and security. Just like a child who will not be able to focus on learning in school if they are hungry, a family that is experiencing food insecurity will not be able to participate in the life of a school or educational community until their most basic needs are met.

The need to belong and connect is also a basic social and emotional need and this is, undoubtedly, an essential part of the process. Immigrant families need to perceive the school as an ally and as a support system, but we realized that simply welcoming them into the building was not enough. We needed to develop a broader understanding of what “welcoming” someone into your community means and to consider the central role that schools play in the socialization process of both immigrant students and their families. The wellbeing promoted by being accepted and socialized into a new community and school translates into what many today refer to as social-emotional learning (Allensworth et al., 2018). Social-emotional learning (or SEL) is the process through which individuals develop the skills needed to recognize and manage their emotions in order to self-regulate and develop positive interpersonal relationships. Durlak et al. (2011) identify five sets of cognitive, affective, and behavioral competencies that need to be fostered as people develop SEL: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision making.

Being in the process of developing SEL and wellbeing will lead to an increased feeling of esteem, which is the next level in Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy. In our project, we focused on the idea of esteem by making sure we included the families’ funds of knowledge (Moll et al., 1992) into the school curricula and we brought their voices, histories, and immigrant journeys to light by discussing them in the classrooms, by inviting the families to be guest speakers, and by including them in the social life of the school building, parent-teacher association (PTA), and different committees that rely on parental involvement and participation. By making use of their personal experiences and their life stories, languages and cultures, immigrant families see how valuable their contributions are and how important we consider them for everyone’s education. This, in turn, will help create the idea of self-actualization described by Maslow (1943).

We understand that the process is not linear, and that the hierarchy might be looked at as a continuum. We may not be able to fulfill one need in order to move to the next level. The idea was to use Maslow’s (1943) research as part of our framework to remind us that, as a school, it is our responsibility to serve the families and the communities where we are situated. It is a two-way street. We understand their needs and try to help them and support them. As a result, immigrant students will also develop healthy lives and identities which will ultimately result in them thriving in the new environment.

One of the purposes of the school is to serve as a liaison between the families and the larger community. Because of the role of schools in serving the children and caring for all their needs, there is a trust that needs to be developed between schools and the families that they serve. Trust is only developed through forming strong and lasting relationships, creating conditions for accepting differences and building an inclusive and open-minded environment. Clear and straightforward communication leads to an understanding of the expectations from all parties involved. In addition, it is necessary to demonstrate commitment to the work and be honest about it. This will result in transparency in the discussions and encourage collective decision-making processes.

Based on the work we have been developing by working closely with immigrant families and students throughout the years, we have developed a framework that groups the strategies described here into two categories: “push” and “pull.”

Push strategies refer to the strategies developed by the school to offer families resources and connect them to an array of services that assist immigrants, especially the ones that attend to their immediate needs. Anyone who is new to a country needs to be given support systems in order to navigate routine aspects of life in society. This includes making them aware of their rights and providing access to services which will help them acclimate in the community. Push strategies distribute resources, information, and support, but may not require further participation or additional involvement on the part of the school. This means that the school functions as an agent that connects families and resources but does not necessarily provide those resources. It is up to the recipient to act upon the information and support suggested by the school.

The reason they are push strategies is because, although initiated by school personnel, they are not related to work done within the school building. They move (or push) the immigrant families from the school to the outside world. The school operates as a mediator that scaffolds the relationship between immigrant families and the larger community.

Pull strategies, on the other hand, focus on actively bringing families from the community to the school building and creating mechanisms to include them in both curricular and extra-curricular activities to strengthen their sense of belonging and identity. By creating opportunities for families to participate in the life of a school building and to engage with teachers and administrators, we are pulling them into the everyday life of the school structure and including their voices in the educational decisions. Table 1 summarizes our framework and gives examples of the kinds of activities and initiatives developed under each category.

When immigrant families arrive at the community, they immediately contact the school to enroll their children. This is when we start the process of welcoming them into our school community and offer to mediate communication and interaction between the families and the resources and services available to them. By connecting them to the services offered for immigrants and the many resources available to them that they are not usually aware of or do not know how to navigate, we aim at supporting their acculturation and facilitating their socialization process.

One of the strategies that seems to be effective when working with immigrant parents is creating opportunities for them to come to the school building for some training and guidance. These sessions work as orientation for a parent who is new to the country and does not know how to get started.

Parent night is a common event in American schools. They differ in terms of purpose and frequency and how much individualized attention parents get. In general, parents come to their children’s classrooms to get to know the teacher, to learn about school policies, expectations, and procedures, and to receive information about how their child is progressing socially and academically while also having the opportunity to interact with the teacher and school personnel, ask questions and express their opinions.

The parent nights planned for this project are events that will bring immigrant parents to the school building several times for both push and pull strategies. The parent nights that focus on push strategies serve as orientation in several workshop style meetings that aim at informing them of the services and resources available to them, as well as guide them through the process of navigating these services. The focus of these sessions will vary depending on the needs of the immigrant families. Sometimes we will bring an immigration lawyer or staff of legal aid societies who can offer free legal support for these families. Other times we will connect them with the local food bank and food pantries, so they know who to reach out to when they need food. Immigrant families also need to be connected to housing authorities and go over the process of applying for public housing. What may seem like simple tasks, such as filling out forms, making sure you have all the documents required by different agencies and being able to communicate your needs can actually be a daunting and intimidating undertaking for families that are new to the country and that are trying to make sense of the environment around them while also having to make decisions and take actions that will affect their lives.

As part of the push strategies, we also want to make sure immigrant families know about free classes they can take (like English as a second language, ESL), and clubs and organizations they can join. We will provide them with lists of names, contact information, useful websites, and books for them to read. Everything is available both in their native language and in English and we will always bring a translator to these sessions so they can have access to the information and feel comfortable to ask questions in their native languages.

For families who do not have internet access and who do not know how to use a computer, there are a lot of free classes offered in local institutions, such as public libraries, where they can also go to have free internet access. The school building also offers internet and computer access and we have even recruited some parents to help immigrant families develop their digital literacy. Some of the workshops include guiding immigrants on how to look for and apply for jobs online, how to write resumés, and even mock interviews to prepare them for the real job interviews.

These parent nights and training sessions help immigrants organize their lives in the new country. The workshops can also vary in terms of the kinds of services provided and skills being honed. They can be used to teach immigrant parents strategies that they can use at home to support the education of their children while also developing and practicing skills that can be directly applied to their lives. For example, helping parents and students with literacy skills is always a topic that draws everyone’s attention because all school activities require the use of literacy skills. One of the workshops that we already had a chance to offer was developed by the ESL teachers and the homeroom teachers to instruct parents on how to develop literacy at home. Because we do have parents who are considered academically illiterate, i.e., they speak their native language but cannot read or write it, we will also have sessions focusing on oral literacy and ways the family can contribute to cultivating literacy at home. The idea for these sessions was adapted from the work described in Naiditch (2013). Teachers encourage parents to tell stories to the children in their native language and to ask questions about these stories. Even if they cannot read in their native language, they can still engage their children in learning about narrative and its elements (plot, character, setting, etc.). This knowledge is essential for teachers to build on in their classes as they teach students the written word. Another strategy is to bring parents to the school for a “day at school.” They can visit classrooms to tell stories about their home countries so that everyone becomes familiar with the students’ cultural background and are also exposed to different approaches to storytelling. In this “day at school,” they can also engage in play and plan other activities to do with the students. They can assist teachers in and outside the classroom and work more closely with all the different professionals that are part of the school community.

As a pull strategy, parent nights are also social events which allow immigrant families to get to know one another and the other members of the school community. They are an opportunity to develop relationships and learn from one another. Teachers engage with the families and learn about the family’s history and their funds of knowledge. Social conversations can work as informal interviews where the families are the experts and the teachers become the learners as they acquire important information about the family’s culture, history, and lived experiences that can be used by teachers to make more informed decisions about pedagogy and ways of relating to and interacting with immigrant students.

In order for these meetings to be effective, it is always important to bear in mind the significance of community and its role in promoting and sustaining a sense of belonging, which is what we ultimately want for these families to feel. Not only that they belong, but that they are also valued and have a contribution to make. They need to understand that we truly care and want to learn from them as much as they want to learn from us. Their lived experiences inform the work we do as educators and in order to be responsive to their needs, we have to understand and learn who they are, what they think and feel, how they see the world. Because, initially, we need to make use of translators, we have also reached out to other families in the community who have immigrated before and have been through the same process to serve as translators. We hope this will make the process even more personal and bring all families closer.

Parent night is also an opportunity to get to know and interact with other families in the community, not only the immigrant families, and start to learn about their ways of thinking and doing. We designed a set of activities to be done with the parents when they come to parent night. These are various “getting-to-know-you” activities, which involve everyone–parents and school staff. Sharing is a big part of these activities. Everyone is encouraged to share their names and meanings (if applicable), countries of origin, languages spoken, anything they consider relevant. We will also ask them to share one success, one accomplishment that has been achieved since the previous meeting. Acknowledging small wins is a way to boost their esteem, increase their motivation and recognize that progress is being made meaningfully.

These activities and gatherings are (and always need to be) intentional, i.e., they are planned with a specific purpose, which is to integrate the families into the larger school community, develop a sense of belonging and empower them so they can develop agency. This last aspect is particularly important because many immigrant families believe that they do not have any agency over their lives and that they depend on the host country as a benefactor. Once they are in the country, though, they need to understand that they are members of the community who should participate in the life of our society by learning about their rights as much as their responsibilities and learning to advocate for their needs and wants.

While mediating the process of socialization for these families, the school becomes a safe space for these families to form relationships, exchange and share experiences, and learn from one another’s challenges and successes. Agency is power. As immigrant families begin to understand how to navigate bureaucracies and as they begin to understand the social norms that regulate the kinds of transactions that they need to participate in, they start becoming more visible both for us as a school community and for themselves, as they recognize the power of engagement in the democratic spirit that permeates our actions and our ways of living.

The same is true about teaching and learning relationships. Agency is a goal we want to achieve both with the families and the students. Agency allows people to understand that they have a voice and choice. Immigrant families must constantly make decisions about how to meet their needs and students face decisions about their learning. As they develop agency, students will understand they have choice over their learning and families will learn how to go about their lives and the challenges they are presented with–all the while, hopefully, learning to make more informed decisions.

From our experience working with immigrant families and students over the years, once they start developing agency, they are more likely to engage in school functions and participate in all aspects of their community both inside and outside the school building.

Family engagement is always at the core of every discussion involving our responsibilities as educators. Schools understand that educating a child depends on the home environment and that, therefore, they need to work with the families. Many schools that are not prepared or do not have qualified personnel to engage immigrants end up blaming the parents for not getting involved in their children’s education. This is a consequence of the deficit model that looks at immigrants as lacking cultural capital without realizing that they just operate from a different perspective which is not the normalized or widely accepted view of our society. Our model is an asset-based approach to working with immigrant families. We need to learn about their ways of communicating, interacting, thinking, and doing, so that we can develop proactive strategies that are intentionally built on their strengths and the knowledge that they bring.

We try to create a safe space where all members are equal participants who have different things to offer without judgment or comparisons. Diversity in this case is about understanding differences, and differences are what inspires us to grow and develop as educators and citizens engaged in the lives of our schools and communities.

As immigrant families become more comfortable interacting with the large school community and as they move from the push to the pull strategies, we will also encourage them to join the PTA. The PTA is an association that brings together teachers and parents to discuss all matters that affect the educational work done in the school, which includes teaching, learning and the wellbeing of the students. This association is an opportunity for parents to participate actively in the decision-making process along with teachers and school personnel and to address any issues that may arise, such as bullying or school safety. Many PTAs also work as fund-raising entities that plan events to raise money for different activities, such as field trips, buying equipment and material. In the case of immigrant families, the PTA can also serve as another liaison between immigrants and the community.

The way we conceive of the PTA is twofold: activism and advocacy. Activism refers to families being actively engaged in the life of the school building and community. Their constant presence in the building reinforces the connection between the schools and the families that they serve and sends a message about the role of parents in the education of their children not only at home, but also in the formal education setting.

Advocacy refers to supporting a cause or an idea, but also to problem-solving. Through advocacy, parents can not only voice their opinions, but also make recommendations and plan courses of action, and take action to make real changes. For example, they can engage in fund raising activities that support and extend the work of the school. Many of the parents, especially immigrants, work full-time jobs with different schedules and hours and not all of them are available and able to pick up their child at 3 pm, which is when the school day usually ends. Through advocacy, they can develop programs, especially after-school activities and can provide free resources and food for the children that need to have extended school hours.

Another example of advocacy and activism is when the school organizes food or clothing drives to benefit the vulnerable members of its community. People are encouraged to donate food, items of clothing and other useful items that families might need, such as toiletries, cleaning products, and even furniture.

An important aspect of acculturation is that immigrant families are usually willing to learn about the so-called American way of life and participate in local and national holidays and celebrations. Some programs we have planned address issues of cultural differences through experience. The Family Adoption Program, for example, places immigrant families with American families and this gives them a chance to experience family life in America. It also gives them a place to spend the holidays and learn about American culture in a more informal setting. A similar experience can be developed through a Partnership Program, sometimes referred to as a “buddy system,” which places immigrant students with American students for social purposes, such as play dates, going out for an activity, studying together, or watching a movie. The idea is for immigrant students to experience as many and varied social situations as possible in order to learn about the culture and make friends. Encouraging immigrant students to participate in volunteering programs and in student clubs can also be effective tools in socializing them beyond the classroom so that the knowledge gained informally can be translated to the relationships established in the classroom to enrich and maximize their educational experiences. Participating in these activities minimizes the effect of culture shock and allows people to get to know one another without being misunderstood and even mislabeled. The more opportunities immigrant and American families have to interact with one another, the more we strengthen the partnership between schools, families and community. These activities also aim at empowering immigrant families. Their participation and engagement can help them develop their agency and their ability to see themselves as capable and contributing members of the community.

An important outcome of developing push and pull strategies is that by being proactive and immediately reaching out to immigrant families, we expect to prevent them from being othered or stereotyped by the rest of the community. The idea of othering is very prevalent in the anti-immigration discourse, which portrays immigrants as not belonging in a community because they do not adhere to the socially, culturally and linguistically established norms. This is an idea also embedded in the “us vs. them” argument, which separates people in affinity groups and segregates those who are seen as “not like us” or “not one of ours.” Othering is a direct result of prejudice and xenophobia. It marginalizes immigrants and blames them for socio-economic problems that existed much before they arrived in the country. The blame-placing rhetoric is a way of justifying a racist attitude and dehumanizing certain groups of people. Education is the only way of combating these discriminatory attitudes and intolerant thinking.

By including immigrant families in all aspects of the school life from the moment they arrive in our community through push strategies that connect them to services, resources, and support systems, and through pull strategies that give them visibility and a sense of belonging and security through inclusion, we aim at integrating immigrant families in the larger community in an intentional, deliberate, scaffolded and safe way.

While we initially thought that we had to start with the push strategies and then work on the pull strategies, our experience has shown us that they do not have to operate separately. On the contrary, schools can work on developing both push and pull strategies concomitantly depending on the individual needs of the families and their level of preparedness and readiness to engage.

Preparedness refers to how much their immediate needs are being met. If an immigrant family feels that they still need to tend to their basic needs and address issues of food or housing, they will need to focus on those first and will only be able and prepared to engage with the school after taking care of those needs.

Readiness has to do with where they stand in their socialization process, i.e., their level of comfort both interacting with new people and participating in school activities. This will also depend on their level of acculturation–whether they want to acculturate or not, how they negotiate their bilingual bicultural identities, as well as their linguistic proficiency. Even though translators are always available, some families feel that they want to be able to communicate without aid and want to try and develop their language skills before coming into the school building. Other families regulate their level of participation by choosing when and how they will engage, what activities they want to join and how ready they feel to join certain groups, committees, and activities. We need to respect their level of readiness. We cannot forge a relationship when immigrant families feel that they are not ready or prepared for it yet.

The idea is to have these push and pull strategies always available for immigrant families and there are people constantly working to ensure that all the resources are being updated and that families know how to access the services that they need. It is an ever-evolving process of communication and outreach. By making these strategies available to immigrant families, we hope to integrate them more easily into the school community (both inside and outside the school building) and to become full participating members of life in the new society.

Conclusion

Immigrants are an integral part of American society, and their contributions are making the country more diverse, more inclusive, and more multicultural. Socializing immigrants successfully into the life of society is an important aspect of the process of acculturation, which invites them to learn about the new society while also encouraging them to maintain their language, culture, customs, and traditions.

One of the challenges of working with immigrant families is the lack of knowledge and preparation of different professionals and organizations, which causes this population to be underserved, and many times, ignored. As educators who deal with immigrant families daily, it is our moral and ethical responsibility to understand who these families are, their histories, and their needs.

Schools have an important social responsibility that goes beyond what is usually expressed in the dyad teaching and learning. Apart from the traditional educational purpose of teaching content and developing skills, schools should strive to meet the needs of the students, the families, and the larger community that they serve. While forming and informing new generations, schools also need to care for individuals’ physical, social, and emotional wellbeing.

Having worked with immigrant families and students for many years, we have developed an approach that puts schools at the center of the socialization process. Navigating governmental agencies and services can be a daunting task for immigrants who may or may not speak the language and who do not understand the systems of bureaucracy established by public services and power structures. The initial focus of an immigrant and a parent is on meeting the immediate needs of their family, but at the same time, they also need to make sense of a new culture, a different language, and a set of rules and conventions that differ from their native norms.

In our work supporting immigrant families and their children, schools have become mediators of the relationships between families and the larger community, and they facilitate the socialization process of parents by educating them and guiding them as they explore and learn about a new environment.

Having developed a framework with push and pull strategies, we hope to be able to create a system that functions seamlessly. Everyone has a role–teachers, administrators, school staff, parents, community members–and everyone feels responsible for the larger goal of supporting the immigrant families, which will ultimately translate into supporting immigrant students. The stress of integrating in a new school, with classmates who do not always look like them, act like them or speak like them can directly affect the wellbeing of a child and their subsequent academic achievement. By making sure we identify and address the needs of the families and their children as soon as possible, we are being proactive in ensuring that the child is fully supported and can therefore thrive in the new society.

As mentioned earlier, this is an ongoing project and a number of the strategies described in this article are still being (or have not yet been) implemented. This is part of a larger project, so the relationships with immigrant families, the outreach, and many of the support systems have already been in place and we have had an opportunity to engage in those strategies (such as workshops and connecting with services). Developing this framework of push and pull strategies was a way to help us organize our work and systematize it, so it can function as part of the school life permanently. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had to interrupt most of the in-person work, which only now is being reinitiated. Our hope is to continue studying the strategies described here and their effect on the socialization and acculturation processes of immigrant families.

Due to current migration movements that are affecting the geography and the distribution of population in the world, communities across the United States will continue to welcome immigrants that will need to be socialized into the life of their new society. In our community in New Jersey, the schools will take a central role in working closely with these families and support them as they engage and proceed in their socialization process.

Push and pull strategies will operate on an ongoing basis and we intend to develop a sustainable process within this framework. Families can always choose to join any of the strategies at any time and they can also regulate their level of involvement, the intensity and the duration of the services, and their participation. The important thing is to create and maintain a channel of communication between the families and the school. The school creates the conditions for immigrant families to feel welcomed and supported in an environment that promotes inclusion and a sense of belonging This, in turn, will strengthen the relationships between the school and the community that it serves.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not provided for this study on human participants because the article does not present the results of human subject research. It describes a framework we developed to be implemented with human subjects in the next academic year. The article describes our proposed strategies and procedures, but the program evaluation has not been conducted yet. The ethics committee will be reviewing our proposal for a study. Written informed consent was not provided because it will be provided after the ethics committee reviews our proposal for the upcoming study.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alba, R., and Nee, V. (2005). Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Allensworth, E. M., Farrington, C. A., Gordon, M. F., Johnson, D. W., Klein, K., McDaniel, B., et al. (2018). Supporting Social, Emotional, & Academic Development: Research Implications for Educators. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

American Psychological Association [APA], and Presidential Task Force on Immigration (2012). Crossroads: The Psychology of Immigration in the New Century. Available online at: http://www.apa.org/topics/immigration/report.aspx (accessed on July 5, 2022).

Anderson, G., Herr, K. G., and Nihlen, A. S. (2007). Studying Your Own School: An Educator’s Guide to Practitioner Action Research, 2nd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. doi: 10.4135/9781483329574

Anderson, G. L., and Herr, K. (2009). “Practitioner action research and educational leadership,” in The SAGE Handbook of Educational action Research, eds S. E. Noffke and B. Somekh (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Ltd), 155–165. doi: 10.4135/9780857021021.n15

Apple, M. W. (2014). Official Knowledge: Democratic Education in a Conservative Age, 3rd Edn. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203814383

Beaman, L. (2012). Social networks and the dynamics of labor market outcomes: evidence from refugees resettled in the U.S. Rev. Econ. Stud. 79, 128–161. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdr017

Budiman, A. (2020). Key Findings About U.S. Immigrants. Available online at: https://www.pewresearch.org/?p=290738 (accessed on July 8, 2022).

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school -based universal interventions. Child Dev. 82, 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Edin, P. A., Fredriksson, P., and Aslund, O. (2003). Ethnic enclaves and the economic success of immigrants: evidence from a natural experiment. Q. J. Econ. 118, 329–357. doi: 10.1162/00335530360535225

Ferrance, E. (2000). ). Action Research (Themes in Education Series). Providence, RI: LAB at Brown University.

Hernandez, D. J., and Charney, E. (eds) (1998). From Generation to Generation: The Health and Well-Being of Children in Immigrant Families. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2011). “Yes, but how do we do it?” Practicing culturally relevant pedagogy,” in White Teachers/Diverse Classrooms: Creating Inclusive Schools, Building on Students’ Diversity, and Providing True Educational Equity, 2nd Edn, eds J. Landsman and C. W. Lewis (Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing), 33–46.

Mandelbaum, D. G. (ed.) (1958). Selected Writings of Edward Sapir in Language, Culture and Personality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev, 50, 370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., and Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Pract. 31, 132–141. doi: 10.1080/00405849209543534

Munshi, K. (2003). Networks in the modern economy: Mexican migrants in the U.S. labor market. Q. J. Econ. 118, 549–599. doi: 10.1162/003355303321675455

Naiditch, F. (2013). Cross the street to a new world. Phi Delta Kappan 94, 26–29. doi: 10.1177/003172171309400606

Naiditch, F. (2021a). Implementing co-teaching to support the language socialization process of immigrant students. Cult. Educ. 33, 1–26. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2021.1978152

Naiditch, F. (2021b). “Culturally responsive teaching: learning to teach within the context of culture,” in Critical Transformative Educational Leadership and Policy Studies – A Reader: Discussions and Solutions From the Leading Voices in Education, ed. J. Paraskeva (Gorham, ME: Myers Education Press), 427–442.

Ochs, E., and Schieffelin, B. (2017). “Language socialization: an historical overview,” in Language Socialization: Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 3rd Edn, eds P. A. Duff and S. May (New York, NY: Springer), 3–16. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-02255-0_1

Ochs, E., and Schieffelin, B. B. (2014). “The theory of language socialization,” in The Handbook of Language Socialization, eds A. Duranti, E. Ochs, and B. Schieffelin (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell), 1–21. doi: 10.1002/9781444342901.ch1

Sapir, E. (1933/1958). “Language,” in Selected Writings of Edward Sapir in Language, Culture and Personality, ed. D. Mandelbaum (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press), 7–32.

United States Census Bureau (2019). Explore Census Data Learn about America’s People, Places, and Economy. Available online at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ (accessed July 8, 2022).

Keywords: immigrants, families, schools, community, socialization, acculturation, strategies, education

Citation: Naiditch F (2022) Beyond schooling: Push and pull strategies to integrate immigrants in the community. Front. Educ. 7:1005964. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1005964

Received: 28 July 2022; Accepted: 26 September 2022;

Published: 03 November 2022.

Edited by:

Sara Victoria Carrasco Segovia, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Gary Anderson, New York University, United StatesBettina Dos Santos, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Copyright © 2022 Naiditch. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Fernando Naiditch, bmFpZGl0Y2hmQG1vbnRjbGFpci5lZHU=

Fernando Naiditch

Fernando Naiditch