- 1Center for Teacher Education, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- 2Optentia Research Focus Area, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

In the last decades, social-emotional learning interventions have been implemented in schools with the aim of fostering students’ non-academic competences. Evaluations of these interventions are essential to assess their potential effects. However, effects may vary depending on students’ variables. Therefore, the current systematic review had three main objectives: 1) to identify the effectiveness of social-emotional learning interventions with students with special educational needs, 2) to assess and evaluate those intervention conditions leading to effective outcomes in social-emotional competences for this population, and 3) to draw specific conclusions for the population of students with special educational needs. For this purpose, studies were retrieved from the databases Scopus, ERIC, EBSCO and JSTOR, past meta-analysis and (systematic) reviews, as well as from journal hand searches including the years 1994–2020. By applying different inclusion criteria, such as implementation site, students’ age and study design, a total of eleven studies were eligible for the current systematic review. The primary findings indicate that most of the intervention studies were conducted in the United States and confirm some positive, but primarily small, effects for social-emotional learning interventions for students with special educational needs. Suggestions for future research and practice are made to contribute to the improvement of upcoming intervention studies.

Introduction

Schools often focus strongly on teaching subject-related content. However, educators and policymakers have increasingly recognized that the teaching and learning of non-academic competences also play an important role when it comes to preparing students for their life journey. In this context, it has been acknowledged that social-emotional well-being is a key factor for school belonging (Allen et al., 2018). A recent systematic review (Amholt et al., 2020) and further meta-analysis (Bücker et al., 2018; Kaya and Erdem 2021) have shown, mixed but overall small to medium effects of well-being on students’ academic achievement. Well-being has also been discussed as a key factor for inclusive education (Hascher 2017; Juvonen et al., 2019). In this context, students with special educational needs (SEN) in particular were found to have reduced well-being (McCoy and Banks 2012; Skrzypiec et al., 2016) and school belonging (Dimitrellou and Hurry 2019) relative to their peers without SEN. Students with SEN have also been reported to lack of social-emotional competences compared to their peers without SEN (Frostad and Pijl 2007). Therefore, the development in and enhancement of social-emotional competences play a crucial role in every students’ life, especially in those of students with SEN. However, the concept of SEN is wide and includes students with distinct (learning) needs that are unaddressed or weakly addressed within mainstream schools and curricula. This results in cognitive, social-emotional, behavioral and/or physical needs, whether or not there is a formal diagnosis (Frederickson and Cline 2015). Yet, there is no consensus on the definition of the wide construct of SEN (Susanne, 2021) as it includes both those students with an official diagnosis (Abedi and Faltis 2015) and those scoring high (Kaptein et al., 2008; Ullebø et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2019; Bryant et al., 2020) on diagnostic instruments such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman 1997; Goodman, Meltzer, and Bailey 1998). In many studies, the sample of students with SEN is also not differentiated by type which may be due to the great number of comorbidities. Students with learning disabilities (LD), for instance, often exhibit ancillary behavior problems (see e.g., Susanne, 2018). Elias et al. (1997) presented teaching methods enabling students to recognize and control their emotions as well as their social interactions. Domitrovich et al. (2017) propose to divide social-emotional competences into an intra- and interpersonal domain. Accordingly, intrapersonal competences comprise self-control, emotional regulation, and coping strategies, while communication, social problem solving, and cooperation are associated with the interpersonal domain. Jones et al. (2017) point out that the former is essential to learning the latter. Social emotional learning (SEL) is thus described by the Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2020) as “the process through which all young people and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to develop healthy identities, manage emotions and achieve personal and collective goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain supportive relationships, and make responsible and caring decisions”. Hence, five core competences are defined for the SEL framework: self-awareness (e.g., understanding emotions and thoughts as well as their impact on behavior), self-management (e.g., goal achievement through managing emotions, thoughts, and behavior), social awareness (e.g., empathy, recognizing social norms), relationship skills (e.g., effective communication, development of healthy relationships, helping others), and responsible decision-making (e.g., individual and social problem solving, reasoned judgment, critical thinking skills). In recent decades, several SEL intervention programs have been developed and implemented in schools. Past research has shown that these programs have positive impacts on academic success as well as non-cognitive skills. For example Corcoran’s et al. (2018) meta-analyses, which included forty studies, found evidence that SEL interventions had positive effects on reading and mathematics and small effects on science. Positive outcomes on social emotional competences could be found in two meta-analyses (Durlak et al., 2011; Wigelsworth et al., 2016) and evidence of long term effects of social-emotional interventions was demonstrated by Sklad et al. (2012), including forty-five studies, and Taylor et al. (2017), including eighty-two studies, although short-term effects were more likely than long-term effects. However, Siddiqui and Ventista (2018) reported slightly more attenuated but positive results in their systematic review on the impact on non-cognitive skills, including thirteen studies.

Overall, several meta-analyses in the last decade could find at least some evidence of SEL intervention benefits on social-emotional competences. Besides individual competences Morganti et al. (2019) emphasize that SEL also plays an important role in the context of SEN and inclusive education, since students learn to recognize and understand the emotions, views, and actions of their classmates, creating an accepting learning environment. The authors highlight that SEL can foster the interaction between students with or without SEN but also predict desirable behaviors or inhibit inappropriate ones. Nonetheless, it remains important to have a closer look at whether students with SEN benefit from SEL intervention programs. Three existing reviews have been carried out on this topic. Hagarty and Morgan (2020) recently published a systematic literature review on SEL interventions for students with LD, including twelve studies. The authors included school-based as well as out-of-school interventions with children aged 4–19. The results show little evidence of the effectiveness of SEL interventions for students with LD. Play-based programs, however, showed more effects, and studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions based on behavioral psychology and social learning theory showed the greatest effect for students with LD. It has to be mentioned that the authors also included intervention studies without control groups as well as case studies. Another systematic literature review and meta-analysis focused on computer-based SEL interventions for individuals on the autistic spectrum (ASD) (Tang et al., 2019). The meta-analysis, including seventeen studies, could find medium effects of computer-based interventions targeting social-emotional outcomes. However, in this study, the participants ranged in age from 3 to 52 years, seventeen intervention studies lacked a control group, and case studies were included. Furthermore, the interventions were only computer based. A further systematic review assessed SEL interventions for students with hearing impairments (Luckner and Movahedazarhouligh 2019). The authors were very reluctant to evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions on SEL outcomes since a great number of the studies had inadequate study designs (e.g., no control group, too few participants, etc.).

Due to the aforementioned studies, it has to be stated that past research mainly examined the effects of SEL interventions for students without SEN. Few available reviews of the effects of SEL programs for students with SEN focused on interventions for individuals with ASD, LD, or hearing impairment and included studies without a control group, also conducted out-of-school (e.g., therapeutic), and included both very young and elderly people. The present systematic review therefore aims to close this gap by examining school-based SEL interventions for school-aged students with SEN.

The research questions leading this systematic review are as follows:

1. What are the effects of SEL interventions on the social-emotional competences of students with SEN?

2. Which intervention conditions (e.g., duration, implementing person, etc.) are most important SEN students’ outcomes?

3. Which specific conclusions can be drawn according to the population of students with SEN?

Methods

Search Procedure and Inclusion Criteria

This systematic literature review aligns with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (Page et al., 2021). The search procedure started in May 2020 and ended in mid-July 2020. The databases Scopus, ERIC, EBSCO, and JSTOR were used to retrieve relevant studies. In advance, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses on SEL interventions were screened to identify keywords used. These keywords were then pooled and systematized. The syntax used in the databases was hence composed of three main areas, namely content, program, and study-related terms. The following syntax was, for example, applied to the Scopus database:

(“social emotional” OR “social and emotional” OR “social-emotional” OR “social emotional competenc*” OR “social-emotional competenc*” OR “social and emotional competenc*” OR “social emotional learning” OR “social and emotional learning” OR “social-emotional learning” “SEL” OR “social emotional wellbeing” OR “social emotional well-being” OR “social and emotional wellbeing” “social and emotional well-being” OR “social-emotional wellbeing” OR “social-emotional well-being” OR “social competence” OR “social development” OR “social skills” OR “social-skills”) AND (intervention OR “class* intervention” OR curriculum OR program* OR implementation OR “education* intervention” OR “evidence-based intervention” OR “school intervention” OR “school-based intervention*" OR “universal intervention*" OR “school-based program*" OR “universal prevention” OR “school-wide” OR education OR prevention OR training) AND (evaluation OR effect* OR outcome* OR “program* evaluation” OR “intervention research” OR “random control” OR “random* trial” OR study OR review OR predictor*)

In addition to the databases, studies from thirteen (systematic) reviews and meta-analysis of SEL interventions were added (Merrell 2010; Durlak et al., 2011; Weare and Nind 2011; Sklad et al., 2012; Humphrey, Lendrum, and Wigelsworth 2013; Barnes, Smith, and Miller 2014; Sullivan and Simonson 2016; Wigelsworth et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2017; Corcoran et al., 2018; Moy et al., 2018; Siddiqui and Ventista 2018; Goldberg et al., 2019). Furthermore, a hand search was completed in the following journals, as they contained a great amount of the studies included in the respective meta-analyses and/or (systematic) reviews: Child Development, Developmental Psychology, Early Education and Development, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, Journal of Educational Psychology, Review of Educational Research, Review of Research in Education, and School Psychology Quarterly.

Several inclusion criteria were defined to answer the research questions. Hence, studies had to meet the following criteria to be included in the systematic literature review:

• published in English

• published since 1994 (since the emergence of the term SEL)

• published in a scientific journal

• focus on SEL intervention

• school-based intervention

• students not older than eighteen during intervention implementation (grade 1 and above)

• empirical research (quantitative or mixed methods)

• sample size of at least ten students with SEN

• reporting outcomes on at least one SEL dimension

• reporting pre and post-test outcomes for students with SEN

• evaluated with a control group (including students with SEN)

SEL interventions were defined as those that had a curriculum and were composed of different sessions in which the promotion of social-emotional competences was addressed and implemented in the same way by teachers/other professionals. Intervention studies in which, for example, teachers were provided theoretical/practical training in SEL and/or in specific teaching techniques aiming to promote these competences without a specific intervention/curriculum were excluded from this literature review. With respect to students’ age, studies were excluded if they did not provide separate data for students within the targeted age group. For example, studies were included if pre-test was in pre-school and followed data for the same sample in first grade after the intervention but excluded if data from pre-school/kindergarten intervention participants were mixed with those of school-aged participants. In terms of methodology, case studies were excluded, as were studies that applied only qualitative methods to evaluate outcomes. Studies had to report at least some descriptive statistics (mean scores and standard deviations for pre-and post-tests for both intervention and control groups) for students with SEN. For example, studies that included only partial descriptive data were included, and the corresponding author(s) was/were contacted and asked for missing data (e.g., studies applying various regression analyses). The missing data were included in the current review and marked accordingly in the reporting tables if provided by the author. If authors could not provide the missing data (e.g., older data) or did not respond, the study had to be excluded, as effect sizes (ES) could not be calculated without sufficient descriptive data. Multiple papers on the same cohort were considered if the inclusion criteria were met and additional data were reported. SEN was operationalized based on an official diagnosis or cut-off values indicated as clinical/high/at-risk on screening instruments such as the SDQ (Goodman 1997; Goodman, Meltzer, and Bailey 1998) or the Systematic Screening for Behavior Disorders tool (SSBD; Walker and Severson 1992). Studies had to report clear cut-off values to be eligible. In this sense, studies that reported, for example, students with behavioral and/or emotional difficulties based on teacher referral (without any assessment) were excluded, as were studies that reported data from “at-risk students” without any further information or assessment.

Screening, Selection, and Critical Appraisal of Selected Studies

The whole process of the current systematic literature review was conducted with the systematic review software Covidence, an online screening and data extraction tool. In the first step, records were uploaded to the tool where duplicates were automatically removed. In a second step, both authors screened study titles and abstracts independently. The online tool allows researchers to mark studies with “yes,” “no,” and “maybe.” When both authors agreed, the respective study was either included or excluded for full-text screening. In case of a disagreement, consensus had to be reached between the authors by discussion. During the full-text screening, both authors independently excluded studies with one of the reasons specified in the inclusion criteria (e.g., no SEN specific outcome). The inclusion criteria were ranked hierarchically, and the reason for exclusion of the studies was determined accordingly. This also means that a study could have several reasons for exclusion; however, the online tool only allows the assignment of one reason. For example, the reason for excluding a study which neither included students with SEN nor had a pre- and post-test design would be “wrong population” since the inclusion criteria of students with SEN is ranked higher in the inclusion criteria than the inclusion criteria pre-post study design.

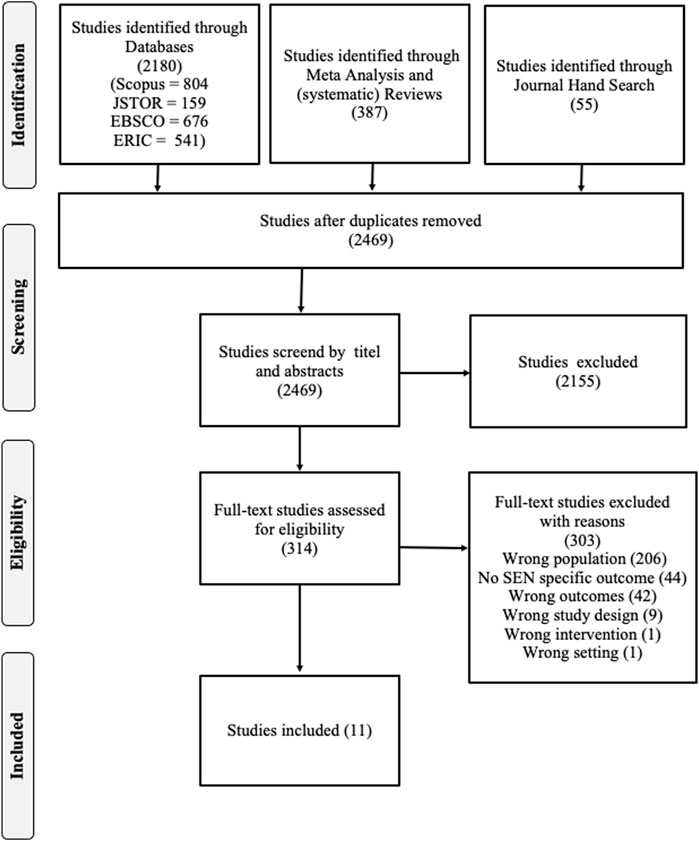

Figure 1 shows the total number of records (N = 2,622) identified through databases (n = 2,180), meta-analysis and (systematic) reviews (n = 387) as well as journal hand search (n = 55). After removing duplicates, a total of 2,469 studies remained for the title and abstract screening. After the title and abstract screening, 314 studies were eligible for full-text screening. After reviewing the full texts, eleven studies remained to be included in the literature review.

Following the full-text screening, the included studies were critically appraised using the checklist instrument for educational intervention studies proposed by Morrison et al. (1999). According to this instrument, nine key questions are put forward to critically evaluate the intervention as well as the evaluation. Topics to be assessed included research question; aims of the intervention; description of the educational context, structure, content, and process of the intervention; study design; methods; outcomes to evaluate the intervention; further explanations of results; and discussion for unanticipated outcomes.

Coding, Data Extraction, and Calculation of Effect Sizes

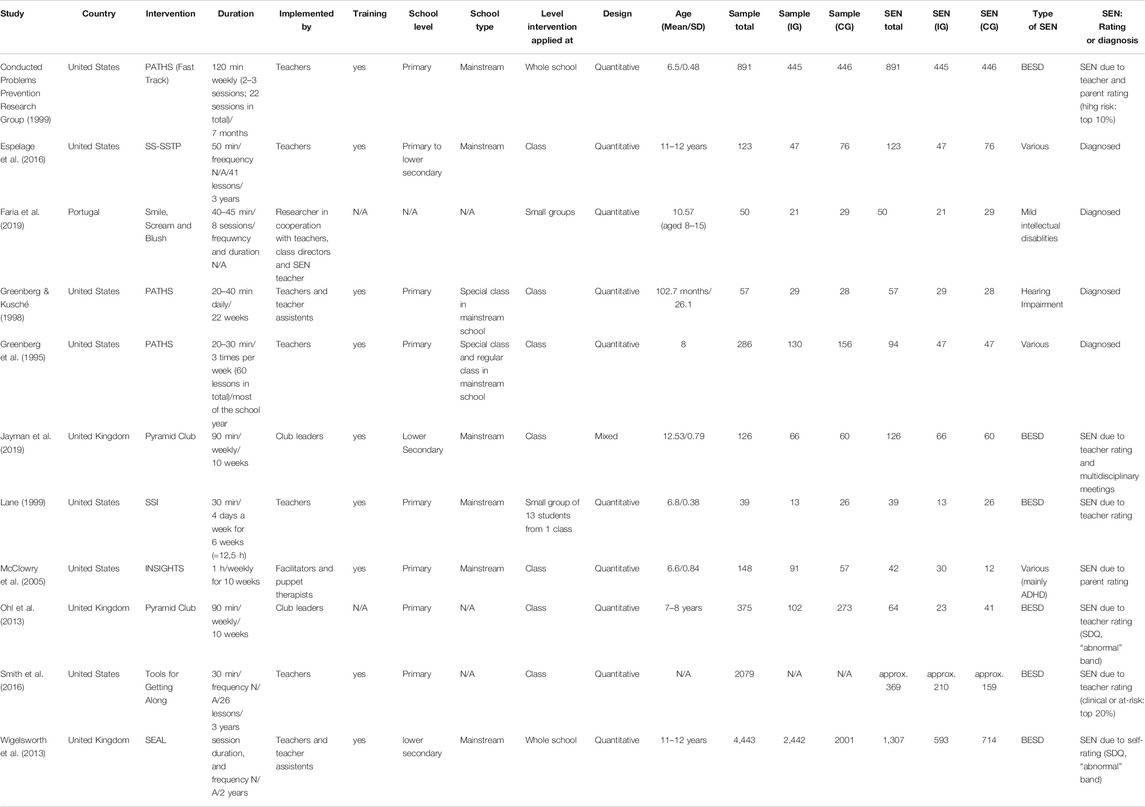

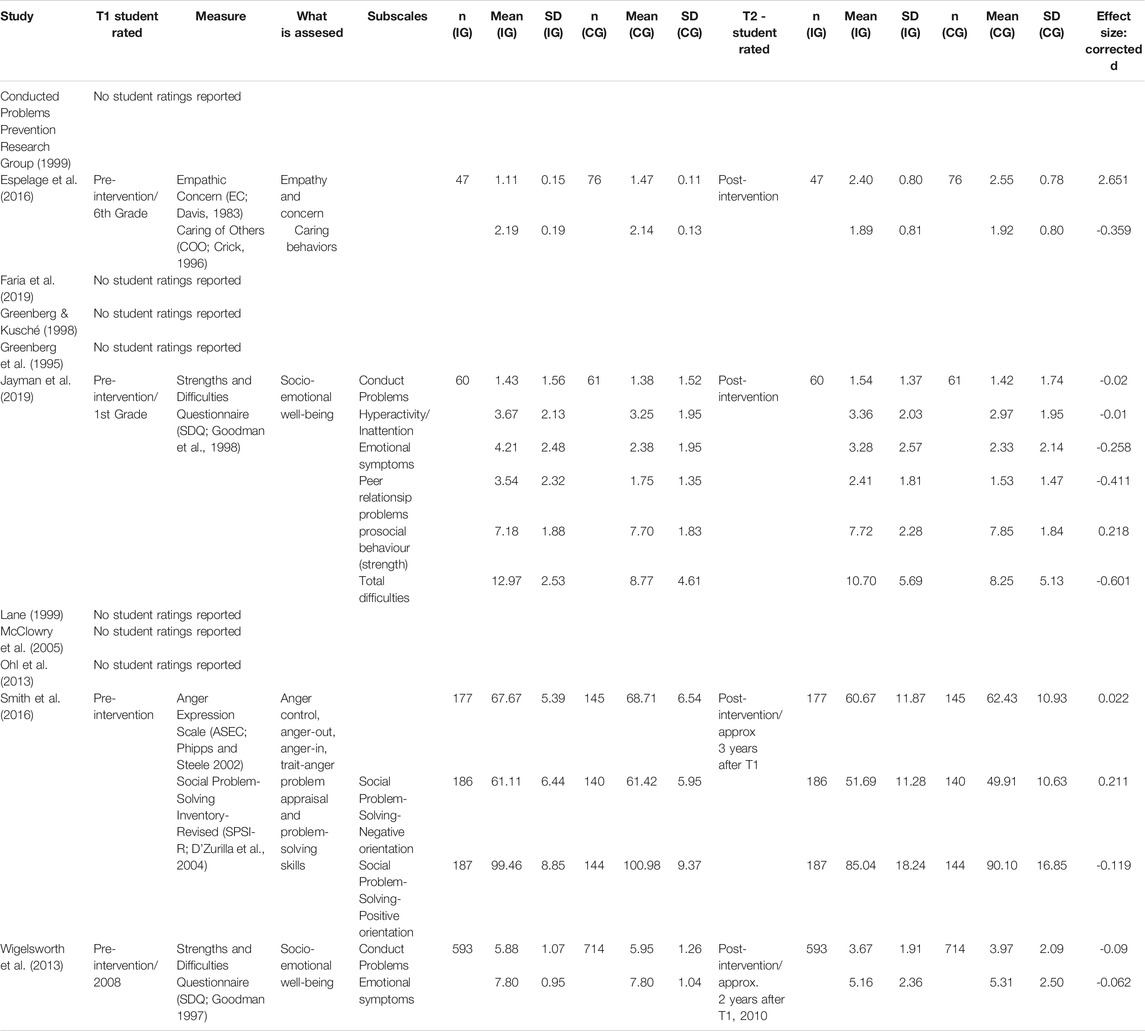

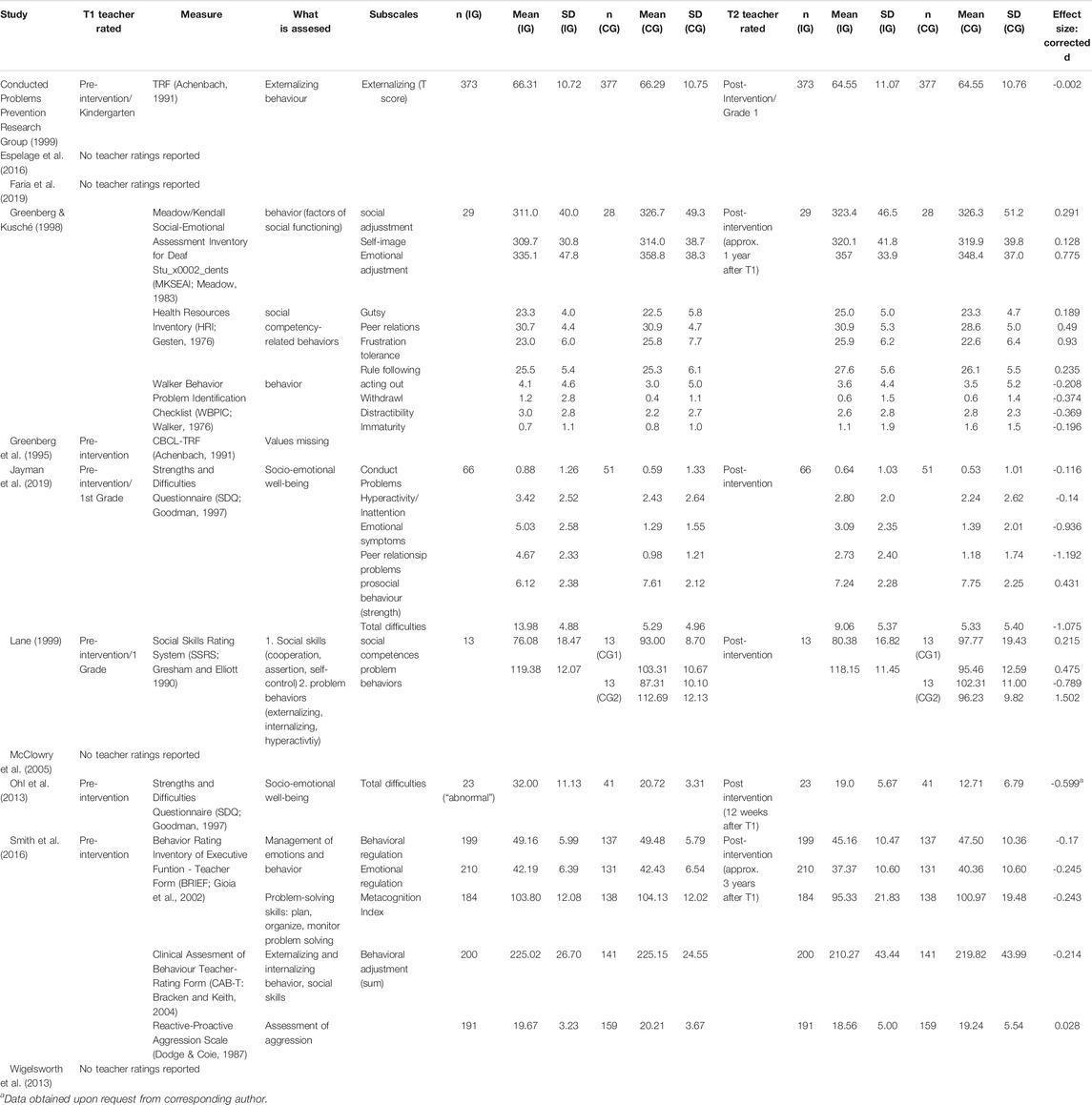

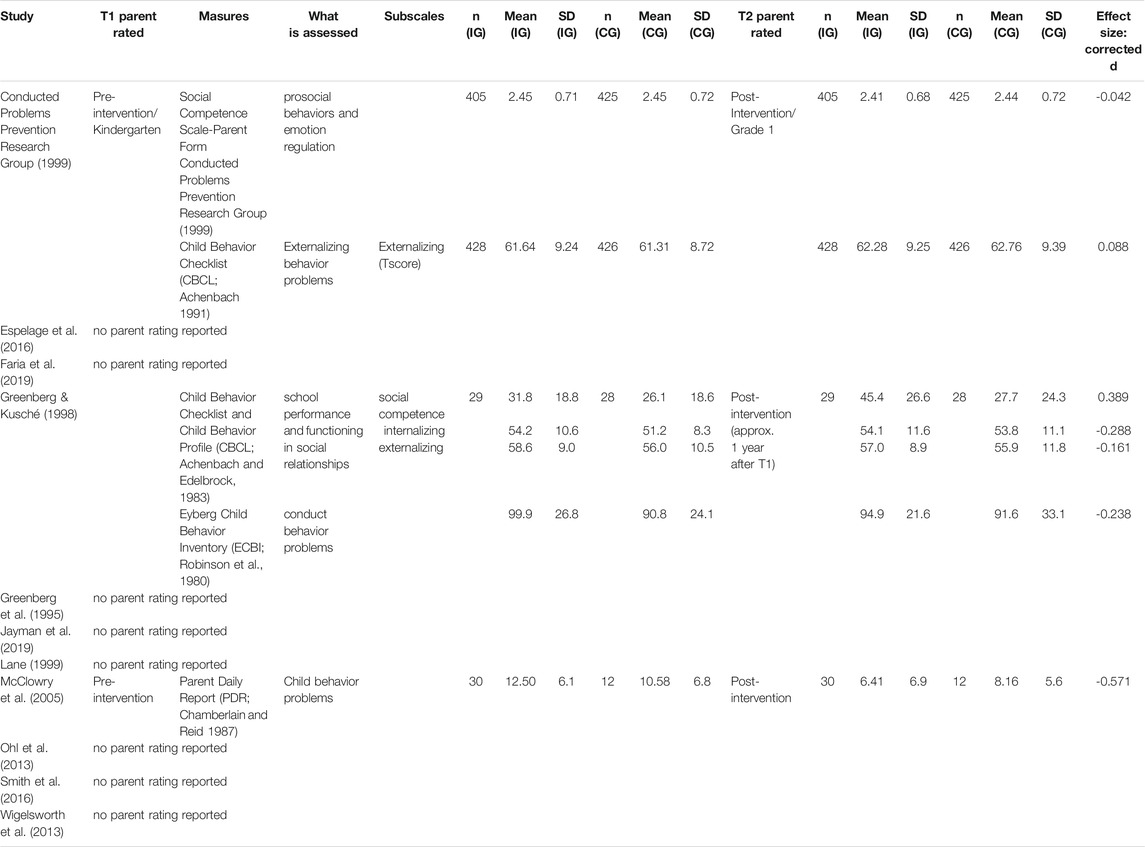

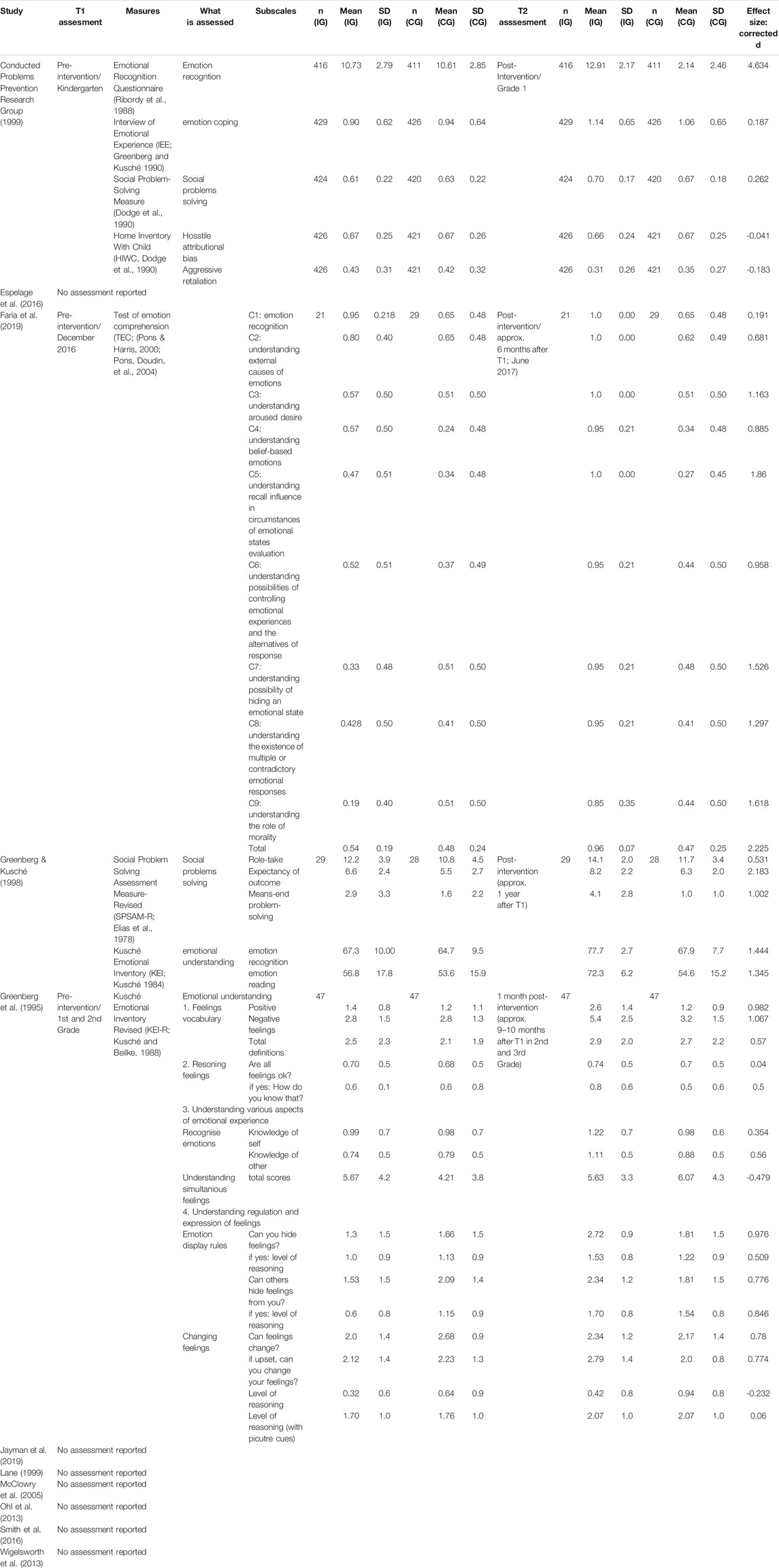

Coding was piloted using two of the eligible studies. To allow a good overview of the intervention and its results, two protocols were designed. The first protocol provides general information on the intervention and the study (Table 1): country, intervention name, intervention duration and frequency, implementer, training, school level and type, research design, mean age, sample, and type of SEN. The second protocol contains student-specific outcomes. The latter provides descriptive statistics for pre- and post-test and is subdivided into four parts: student ratings, teacher ratings, parent ratings, and assessments (Tables 2–5). Studies used a variety of designs leading to reported outcomes on at least one of the aforementioned subgroups to assess emotional and/or social/behavioral competences for the participating students. In the case of several measurement points during the intervention, only pre- and post-test data were extracted, as only a few studies reported (e.g., Espelage, Rose, and Polanin 2016).

Calculation of effect sizes (ES) was necessary since they were missing in some studies or reported differently across the studies. Since only evaluations with pre-post designs (repeated measurement points) that were evaluated with a control group were included, the ES dcorr was calculated for each study following Klauer (2014), who proposes to use the difference between the Hedge’s g of the intervention (IG) and control group (CG). This corrected version allows for unbiased ES, especially for studies with smaller sample sizes. ESs are indicated as small (<0.5), medium (0.5–0.8), or large (>0.8) within the tables.

Results

Due to the inclusion criteria a total of eleven studies (Greenberg et al., 1995; Greenberg and Kusché 1998; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999; Lane 1999; Sandra G.; McClowry, Snow, and Tamis-LeMonda 2005; Ohl, Fox, and Mitchell 2013; Wigelsworth, Humphrey, and Lendrum 2013; Espelage, Rose, and Polanin 2016; Smith et al., 2016; Faria, Esgalhado, and Pereira 2019; Jayman et al., 2019)were found eligible for the current systematic review. This section is subdivided into two sections and reports on general information (see also Table 1) regarding the interventions (e.g., name of intervention, country in which it was implemented, etc.) as well as some basic information regarding the study (e.g., study design, sample size and type of SEN). The second section reports on measures and outcomes with a focus on ESs. Descriptive data for pre- and post-intervention measures are presented in Table 2 through 5 to provide a better overview.

General Information

Publication dates reached from 1995 to 2019. Most of the program evaluations were conducted in the United States (n = 7), followed by the United Kingdom (n = 3), while one study was evaluated in Portugal. Regarding author overlap, it can be reported that this appeared in one case, comprising three studies, and in a second case, comprising two studies, where at least two authors appeared as (co)authors. In total, eight different intervention programs were evaluated, namely: Promoting Alternative THinking Strategies (PATHS) (n = 3); Pyramid Club (n = 2); Second Step-Student Success Through Prevention (SS-SSTP); Smile, Scream and Blush; Social Skills Intervention (SSI); INSIGHTS into Children’s Temperament intervention (INSIGHTS), the Tools for Getting Along, and Secondary Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL). Sessions were conducted in most of the studies at least on a weekly basis for 20–120 min, while few studies did not report any information on the frequency (n = 4). The intervention was delivered by teachers in seven of the studies and by external persons (e.g., facilitators, puppet therapists, researcher) in four studies. Training for implementation was provided in nine cases. Two studies did not provide any information in this regard; however, this concerns those interventions that were delivered by external professionals. In most of the studies (n = 7), the intervention was implemented in a primary mainstream school; two of these had regular and special classes. Seven interventions were implemented at the classroom level, two in small groups, and two at the school level. Ten studies reported a quantitative study design while one applied a mixed-method design. Students aged 6.5 to 14 in ten studies, while one study could not report neither on the mean age nor age ranges as data was not available for all students. The total sample size of the study ranged from 39 to 443, while the sample size of students with SEN ranged from 39 to 1,307. The sample size for students with SEN in the intervention group ranged from 13 to 593, and from 12 to 714 for the control group. Six studies reported data for students with Behavioral, Emotional, Social Difficulties (BESD), three studies for students with diverse SEN, one study for students with mild intellectual disabilities and one for students with hearing impairment. Four studies reported on outcomes for students with a diagnosed SEN. Seven studies included those students in their sample who scored high/clinical on screening instruments assessing behavioral and/or emotional problems.

Outcomes for Emotional, Social, Behavioral Competences

In the reviewed studies, reported outcomes were measured in the form of student ratings (n = 4), teacher ratings (n = 6), parent ratings (n = 3), and assessments (n = 4). Five studies reported outcomes from at least two different assessors for social/behavioral and/or emotional competences. Seven studies reported outcomes in the social/behavioral and emotional domains, two in emotional, and two in social/behavioral competences. In total, ES (d corr) for emotional, social, behavioral competences ranged from small (-0.208) to large (4.634). When comparing different reporting sources on overall ES, student ratings yielded small (0.211) to large (2.651) effects, teacher ratings showed likewise small (0.208) to large (-1.192) ES, parent ratings yielded small (-0.238) to medium (-0.571) ES, and assessments yielded small (-0.232) to large (4.634) ES. However, small ESs were much more frequent than medium to large ones, except for assessments, where this was the reversed (see Tables 2–5).

Overall, ES for emotional outcomes ranged from small (-0.245) to large (4.634). In student ratings ES for emotional outcomes ranged from small (-0.258) to large (2.651) in two studies while no effect on emotional outcomes could be found in two studies (anger control; emotional symptoms). In teacher ratings, ES for emotional outcomes ranged from small (-0.245) to medium (-0.936) in four studies, while in two studies two subscales on emotional outcomes (self-image, aggression) did not yield any ES. In the three studies that included parent ratings, only one assessed emotional outcomes, finding no effects. Studies using assessments to evaluate emotional competences ranged in ES from medium (0.681) to large (4.634), available in four studies. However, in one study reporting on a subscale regarding emotion coping, no effect could be found, while another subscale of this study had a large ES in emotion recognition. In a second study, however, no effects could be shown on the subscale for emotion recognition.

For the overall effects of social/behavioral outcomes, ES ranged from small (-0.208) to large (2.183). For student ratings, ESs for social/behavioral outcome, available in three studies, were small (0.211) to medium (-0.411). In one of these studies, there was no effect for the subscale positive orientation in social problem solving, and in a second study, there was no effect for two subscales on conduct problems and hyperactivity. For teacher ratings, ES ranged from small (-0.208) to large (1.502). In one of these studies, no effect could be found for one subscale assessing externalizing behavior, in a second study there was no effect regarding the subscales on conduct problems and hyperactivity, and in a third study a subscale regarding behavioral adjustment did not show an effect. For parent ratings of social/behavioral outcomes, ES ranged from small (-0.238) to medium (-0.571), while in one of these studies no effect could be shown for the externalizing behavior subscale. In one study, which included parent ratings, no effect at all could be shown either for the pro-social behavior or the externalizing behavior problems subscale. For the two studies applying assessments to evaluate social/behavioral outcomes, ES ranged from small (0.262) to large (2.183) for social problem-solving skills, while in one of these studies assessing hostile attributional bias and aggressive relation, no effects could be found.

Discussion

During past decades the number of published studies has radically increased in the field of inclusive education. One the one hand challenges of inclusion have clearly been made visible. For instance, it was shown that students with SEN have lower social skills (Frostad and Pijl 2007) and are at risk of low social participation (Banks, McCoy, and Frawley 2018; Zweers et al., 2021). On the other hand, there is still a considerable gap in research providing evidence on how to prevent or intervene these challenges. The main aim of the current study was hence to assess whether SEL interventions are effective in the population of students with SEN. In contrast to the few existing reviews/meta-studies published on the same topic (SEL intervention and its effects on the population of students with SEN), within the current study, only studies following high methodological standards, including a (waiting-)control-group design and reporting results for pre- and post-tests on SEL dimension(s), were included. This decision was made to allow a more reliable judgment of the effects of SEL programs on students with SEN.

First, based on the selected studies, it became apparent that SEL interventions are more frequently evaluated in the United States than in other countries. Only three out of the eleven studies were conducted in Europe, with an overlap of authors for two of these studies. On the one hand, this is somehow not surprising, since the first SEL programs have been developed and implemented within the US context (Osher et al., 2016). On the other hand, previous literature e.g., in Europe has also highlighted the urgent need to foster social-emotional competencies of students with SEN. However, for some effective intervention programs developed in the United States (e.g., PATHS), there are also studies showing that effects could be shown in the United Kingdom but equally for the intervention and control group when implemented outside of the United States (see e.g., Humphrey et al., 2016). These geographical differences regarding the effectiveness may result from various reasons (e.g., transferability of programs from one continent to the other, different school systems, different social norms, etc.) and have been discussed in the respective evaluations. A positive finding from the articles reviewed that needs to be highlighted is that those people delivering the intervention, in most cases teachers, received training prior to implementation. Implementation quality has been shown to be an important factor for intervention outcomes (for an overview see e.g., Durlak and DuPre 2008). Past research has shown that teacher training affects implementation quality and thus the effectiveness of the program regarding SEL outcomes for students (see e.g., Durlak and DuPre 2008; Bradshaw 2015; Humphrey, Barlow, and Lendrum 2018). Therefore, in line with previous research, the present study recommends giving a crucial role to the implementation processes of interventions in schools as well as their evaluation in research.

Regarding the overall results of the current study with respect to the first research question, it can be reported that the review of studies found some evidence supporting the effectiveness of SEL programs for students with SEN. The effects were reported by different raters (e.g., self-ratings from students, teacher ratings, parent ratings) or were evaluated via assessments. Positive changes were particularly reported in emotional outcomes for this subsample, with improvements ranging between small and large effects, with the former predominating. For these outcomes more precisely, ESs were slightly higher for assessments (0.681–4.634) than for students’ ratings (-0.258–2.651). Effects for teacher ratings (-0.245 to -0.936) were even a bit lower, and no effect was found in the only study that included parents’ ratings. This result might indicate that changes in emotional outcomes are less sensitive for observers compared to assessment. While these outcomes are somewhat promising out of eight studies reporting effects on emotional outcomes, one did not find any effects, while one did not find effects for parent ratings but for the assessment. The picture is different for social/behavioral outcomes. Teacher ratings showed the highest effects (-0.208–1.502) compared with student ratings (0.211 to -0.411), parent ratings (-0.238 to -0.571), and assessments (0.262–0.531), especially for social/problem-solving skills. However, again not all studies showed significant outcomes of the intervention on social behavioral aspects. Interestingly, several studies could not find any effect for externalizing behavior, regardless of the rater. One explanation may be that interventions may not have addressed externalizing behavior within their curriculum or that additional and more specific components were needed for students with behavioral difficulties. To conclude, it can be stated that nearly half of the studies included outcomes from different sources, which is highly important since outcomes might be biased e.g., if the teacher him/herself is implementing the intervention. Further, other studies already indicated that raters’ perspectives might play a significant role and stressed the importance of multi-informant assessment (e.g., Achenbach 2018; Miller et al., 2018). Achenbach (2018) argues that students’ behavior in particular might vary in different contexts, which results in different perceptions of different raters. However, taking all sources into account, within the current study, small to medium ESs were demonstrated by all raters (students’ self-ratings, teacher ratings, parent ratings, assessments), although most of the effects were small.

With respect to the second research question (specific effects based on specific intervention conditions), no conclusion can be drawn within the current literature review. Generally, different intervention programs have been used within the included studies. Moreover, the frequency of the implementation of the intervention varied widely, and around one third of the studied did not indicate information on frequency. Two studies provided insufficient information about the individuals delivering the intervention. However, most interventions (seven out of eleven) have been implemented by the teachers. This is somewhat promising, as the ecological validity is higher if no external persons (e.g., researchers) are interfering in the setting, though more experimental settings often show higher ESs at least for short-term effects. Furthermore, as only four studies have been included where no teachers implemented the intervention, no precise conclusions can be drawn within the current review study.

Regarding the third research question, it can be reported that within the included studies, the samples varied a lot. For instance, not only studies with students having an official diagnosis of SEN, but also studies with students who scored clinical/high/at-risk of BESD were included. However, taking into account the specific operationalizations of SEN (e.g., legal diagnosis, teacher rating, parent rating) or the specific type of SEN (e.g., behavior problems, physical disability), it was not possible within the present study to draw specific conclusions according to the population of students with SEN since the total number of studies included was limited. For example, several studies included students with SEN in the intervention but did not provide separate statistical data for this subsample. Subgroup analyses provide an important contribution to the evaluation of whether an intervention achieves differential effects in specific student populations. Furthermore, in several trials, students with SEN were completely excluded from the intervention study (e.g., Aber, Brown, and Jones 2003; Gueldner and Merrell 2011; Ialongo et al., 2019). Therefore, the studied population within the current literature review is also influenced by this bias. Not only, but also for students with SEN, it would be crucial to include them in interventions and evaluate their social-emotional outcomes. Researchers are therefore encouraged to use instruments that are appropriate for these students.

Limitations

The current study has to be read in light of several limitations. First, relevant publications may not have been identified due to the keywords used or missing journal access. Moreover, within the current study, only English-language publications were considered eligible. Since intervention studies might be aimed at a practitioner-oriented audience (e.g., teachers), it is expected that there will be more studies published in the language of instruction. Next, likewise, as in all systematic literature reviews, there is a publication bias affecting the outcomes. Non-significant studies generally are less often published. Additionally, non-significant outcomes for the treatment group or contrary to the expected results (e.g., negative treatment effects, etc.) are rarely published (for more information about the publication bias see e.g., (Cooper, DeNeve, and Charlton 1997; Card 2012). In addition, for some studies, it was difficult to determine whether the intervention program could be considered as SEL. In particular, the lack of information about the intervention led to decision disagreements among the authors. While for some included interventions (e.g., PATHS, SEAL) it was clear that they were following the SEL criteria, for others it was rather difficult to make a clear decision, and those papers therefore had to be excluded from the current review. Similarly, for some studies, detailed (descriptive) information was missing in the publications and therefore corresponding authors were contacted via email. While some information was added due to personal contact between the original authors of the study and the authors of the review, some papers had to be excluded due to unavailable information. Furthermore, it has to be stated that systematical literature reviews are rare in the field of students with SEN. This can partly be explained by specific problems. First of all, the studied population is broad and still difficult to narrow down. Even studies using the same terminology (SEN) do not compare similar populations; for example, the criteria for having a diagnosis of SEN varies widely between countries and sometimes even within countries (see e.g., Susanne, 2021). Moreover, summarizing students into a group of students with SEN diagnosis is difficult since the group of students with SEN is heterogeneous. Therefore, one student with SEN might be very different from another student with SEN. Just giving one example: in the population of students with SEN, the age of students attending the same grades might vary widely, and therefore studies including students older than eighteen had to be excluded. Furthermore, SEN was also operationalized based on clinical scores from diagnostic assessment instruments. In this regard, scores were based on teacher and/or parent ratings (Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 1999; McClowry et al., 2005), but also one study based on students’ ratings (Wigelsworth, Lendrum, and Humphrey 2013) was included. However, previous literature has already indicated that behavior ratings are sensitive based on the rater (e.g., Cheng et al., 2018).

Finally, the possibility of giving a quantitative summary or conducting a meta-analysis is limited within the current review. Not only the insufficient numbers of included studies in total but also the huge variations in study design, the intervention conditions, and the methodological quality cut the possibilities for showing overall ESs. Therefore, conducting a meta-analysis was not feasible with such a high diversity in the population and the interventions studied, taking into account interesting research questions (e.g., correlation of intervention duration/frequency and effectiveness, who should deliver the intervention). Taking these limitations into account, the ESs reported within this study might be overestimated. ESs could be lower if more variables are included. Hence, only including pre-post data of the intervention and control groups and no other variables could lead to overestimated ES. Potential moderator variables (e.g., the type of disability, age of students, etc.) and possible interaction effects of variables (e.g., duration of intervention, frequency of intervention) have to be investigated in future research.

Conclusion

This literature review provided the first systematic insight into the effectiveness of SEL programs in the population of students with SEN. While some positive effects could be identified, an important finding of the current study is the need for further research. There is still the need for research to determine the features of intervention programs that are most successful. Therefore, in order to achieve the most successful outcomes for students with SEN, much more research is required in the future. One further gap identified in this literature review regarding pedagogical practice was that in the studies reviewed, students with SEN themselves were minimally involved in intervention decisions. Not a single study included student decisions (e.g., about the specific intervention program). Involving the advocates themselves could increase the effects, as self-determination plays a crucial role, especially in the subgroup of students with SEN. Additionally, it would be critical to foster teacher awareness of evidence-based teaching practices as part of the teacher training curriculum. Finally, the highest effects on a student population can be reached if effective strategies are used in teachers’ day-to-day practice.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abedi, J., and Faltis, C. (2015). Teacher Assessment and the Assessment of Students with Diverse Learning Needs. Rev. Res. Edu. 39 (1), vii–xiv. doi:10.3102/0091732X14558995

Aber, J. L., Brown, J. L., and Jones, S. M. (2003). Developmental Trajectories toward Violence in Middle Childhood: Course, Demographic Differences, and Response to School-Based Intervention. Dev. Psychol. 39 (2), 324–348. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.324

Achenbach, T. M., and Edelbrock, C. S. (1983). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: T. M. Achenbach.

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Integrative Guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont.

Achenbach, T. M. (2018). Multi-Informant and Multicultural Advances in Evidence-Based Assessment of Students' Behavioral/Emotional/Social Difficulties. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 34 (2), 127–140. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000448

Allen, K., Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., and Waters, L. (2018). What Schools Need to Know about Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 30 (1), 1–34. doi:10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Amholt, T. T., Dammeyer, J., Carter, R., and Niclasen, J. (2020). Psychological Well-Being and Academic Achievement Among School-Aged Children: A Systematic Review. Child. Ind. Res. 13 (5), 1523–1548. doi:10.1007/s12187-020-09725-9

Banks, J., McCoy, S., and Frawley, D. (2018). One of the Gang? Peer Relations Among Students with Special Educational Needs in Irish Mainstream Primary Schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 33 (3), 396–411. doi:10.1080/08856257.2017.1327397

Barnes, T. N., Smith, S. W., and Miller, M. D. (2014). School-Based Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions in the Treatment of Aggression in the United States: A Meta-Analysis. Aggression Violent Behav. 19 (4), 311–321. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.013

Bracken, B. A., and Keith, L. K. (2004). Clinical Assessment of Behavior. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating Research to Practice in Bullying Prevention. Am. Psychol. 70 (4), 322–332. doi:10.1037/a0039114

Bryant, A., Guy, J., Holmes, J., Duncan, A., Baker, K., Gathercole, S., et al. (2020). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Predicts Concurrent Mental Health Difficulties in a Transdiagnostic Sample of Struggling Learners. Front. Psychol. 11, 3125. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587821

Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., and Luhmann, M. (2018). Simonsmeier, Michael Schneider, and Maike LuhmannSubjective Well-Being and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. J. Res. Personal. 74 (June), 83–94. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2018.02.007

Card, N. A. (2012). Applied Meta-Analysis for Social Science ResearchApplied Meta-Analysis for Social Science Research. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Chamberlain, P., and Reid, J. B. (1987). Parent Observation and Report of Child Symptoms. Behav. Assess. 9 (1), 97–109.

Cheng, S., Keyes, K. M., Bitfoi, A., Carta, M. G., Koç, C., Goelitz, D., et al. (2018). Keyes, Adina Bitfoi, Mauro Giovanni Carta, Ceren Koç, Dietmar Goelitz, Roy Otten, et alUnderstanding Parent-Teacher Agreement of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Comparison across Seven European Countries. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 27 (1), e1589. doi:10.1002/mpr.1589

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (2020). CASEL SEL Framework. Available at: https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CASEL-SEL-Framework-11.2020.pdf.

Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (1999). Initial Impact of the Fast Track Prevention Trial for Conduct Problems: I. The High-Risk Sample. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. J. Consult Clin. Psychol. 67 (5), 631–647.

Conducted Problems Prevention Research Group (1999). Technical Reports for the Fast Track Assessment Battery. Fast Track Project.

Cooper, H., DeNeve, K., and Charlton, K. (1997). Finding the Missing Science: The Fate of Studies Submitted for Review by a Human Subjects Committee. Psychol. Methods 2 (4), 447–452. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.2.4.447

Corcoran, R. P., Cheung, A. C. K., Kim, E., and Xie, C. (2018). Effective Universal School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Programs for Improving Academic Achievement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 50 Years of Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 25, 56–72. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2017.12.001

Crick, N. R. (1996). The Role of Overt Aggression, Relational Aggression, and Prosocial Behavior in the Prediction of Children's Future Social Adjustment. Child. Dev. 67 (5), 2317–2327. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01859.x

D'Zurilla, T. J., Nezu, A. M., and Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2004). “Social Problem Solving: Theory and Assessment,” in Social Problem Solving: Theory, Research, and Training. Editors E. C. Chang, T. J. D’Zurilla, and L. J. Sanna (Washington: American Psychological Association), 11–27. doi:10.1037/10805-001

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring Individual Differences in Empathy: Evidence for a Multidimensional Approach. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 44 (1), 113–126. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Dimitrellou, E., and Hurry, J. (2019). School Belonging Among Young Adolescents with SEMH and MLD: The Link with Their Social Relations and School Inclusivity. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 34 (3), 312–326. doi:10.1080/08856257.2018.1501965

Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., and Pettit, G. S. (1990). Mechanisms in the Cycle of Violence. Science 250 (4988), 1678–1683. doi:10.1126/science.2270481

Dodge, K. A., and Coie, J. D. (1987). Social-information-processing Factors in Reactive and Proactive Aggression in Children's Peer Groups. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 53, 1146–1158. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.53.6.1146

Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, K. C., and Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-Emotional Competence: An Essential Factor for Promoting Positive Adjustment and Reducing Risk in School Children. Child. Dev. 88 (2), 408–416. doi:10.1111/cdev.12739

Durlak, J. A., and DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation Matters: A Review of Research on the Influence of Implementation on Program Outcomes and the Factors Affecting Implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 41 (3–4), 327–350. doi:10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students' Social and Emotional Learning: a Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child. Dev. 82 (1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Elias, M. J., Larcen, S. W., Zlotlow, S. P., and Chinsky, J. H. (1978). An Innovative Measure of Children's Cognitions in Problematic Interpersonal. Toronto, Canada: Paper presented at the American Psychological Association.

Elias, M. J., Zins, J. E., Weissberg, R. P., Frey, K. S., Greenberg, M. T., Haynes, N. M., et al. (1997). Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators. Alexandria, Va., USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Espelage, D. L., Rose, C. A., and Polanin, J. R. (2016). Social-Emotional Learning Program to Promote Prosocial and Academic Skills Among Middle School Students with Disabilities. Remedial Spec. Edu. 37 (6), 323–332. doi:10.1177/0741932515627475

Faria, S. M. M., Esgalhado, G., and PereiraPereira, C. M. G. (2019). Efficacy of a Socioemotional Learning Programme in a Sample of Children with Intellectual Disability. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 32 (2), 457–470. doi:10.1111/jar.12547

Frederickson, N., and Cline, T. (2015). Special Educational Needs, Inclusion and Diversity. Third edition. Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press.

Frostad, P., and Pijl, S. J. (2007). Does Being Friendly Help in Making Friends? the Relation between the Social Position and Social Skills of Pupils with Special Needs in Mainstream Education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 22 (1), 15–30. doi:10.1080/08856250601082224

Gesten, E. L. (1976). A Health Resources Inventory: The Development of a Measure of the Personal and Social Competence of Primary-Grade Children. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 44 (5), 775–786. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.44.5.775

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Retzlaff, P. D., and Espy, K. A. (2002). Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in a Clinical Sample. Child. Neuropsychol. 8 (4), 249–257. doi:10.1076/chin.8.4.249.13513

Goldberg, J. M., Sklad, M., Elfrink, T. R., Schreurs, K. M. G., Bohlmeijer, E. T., and Clarke, A. M. (2019). Effectiveness of Interventions Adopting a Whole School Approach to Enhancing Social and Emotional Development: A Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 34 (4), 755–782. doi:10.1007/s10212-018-0406-9

Goodman, R., Meltzer, H., and Bailey, V. (1998). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Pilot Study on the Validity of the Self-Report Version. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 7 (3), 125–130. doi:10.1007/s007870050057

Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 38 (5), 581–586. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Greenberg, M. T., and Kusché, C. A. (1990). Inventory of Emotional Experience: Technical Report. Seattle: University of Washington.

Greenberg, M. T., and Kusché, C. A. (1998). Preventive Intervention for School-Age Deaf Children: The PATHS Curriculum. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Edu. 3 (1), 15. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014340

Greenberg, M. T., Kusche, C. A., Cook, E. T., and Quamma, J. P. (1995). Promoting Emotional Competence in School-Aged Children: The Effects of the PATHS Curriculum. Dev. Psychopathol 7 (1), 117–136. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006374

Gresham, F. M., and Elliott, S. N. (1990). Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Gueldner, B., and Merrell, K. (2011). Evaluation of a Social-Emotional Learning Program in Conjunction with the Exploratory Application of Performance Feedback Incorporating Motivational Interviewing Techniques. J. Educ. Psychol. Consultation 21 (1), 1–27. doi:10.1080/10474412.2010.522876

Hagarty, I., and Morgan, G. (2020). Social-Emotional Learning for Children with Learning Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 36 (2), 208–222. doi:10.1080/02667363.2020.1742096

Hall, C. L., Guo, B., Valentine, A. Z., Groom, M. J., Daley, D., Sayal, K., et al. (2019). The Validity of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) for Children with ADHD Symptoms. PLOS ONE 14 (6), e0218518. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218518

Hascher, Tina. (2017). “Die Bedeutung von Wohlbefinden und Sozialklima für Inklusion,” in Inklusion: Profile für die Schul- und Unterrichtsentwicklung in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz: theoretische Grundlagen, empirische Befunde, Praxisbeispiele. Beiträge zur Bildungsforschung (Münster New York: Waxmann), 69–79.

Humphrey, N., Barlow, A., and Lendrum, A. (2018). Quality Matters: Implementation Moderates Student Outcomes in the PATHS Curriculum. Prev. Sci. 19 (2), 197–208. doi:10.1007/s11121-017-0802-4

Humphrey, N., Barlow, A., Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., Pert, K., Joyce, C., et al. (2016). A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial of the Promoting Alternative Thinking Strategies (PATHS) Curriculum. J. Sch. Psychol. 58 (October), 73–89. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2016.07.002

Humphrey, N., Lendrum, A., and Wigelsworth, M. (2013). Making the Most Out of School-Based Prevention: Lessons from the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) Programme. Emotional Behav. Difficulties 18 (3), 248–260. doi:10.1080/13632752.2013.819251

Ialongo, N. S., Domitrovich, C., Embry, D., Greenberg, M., Lawson, A., Becker, K. D., et al. (2019). Celene Domitrovich, Dennis Embry, Mark Greenberg, April Lawson, Kimberly D. Becker, and Catherine BradshawA Randomized Controlled Trial of the Combination of Two School-Based Universal Preventive Interventions. Dev. Psychol. 55 (6), 1313–1325. doi:10.1037/dev0000715

Jayman, M., Ohl, M., Hughes, B., and Fox, P. (2019). Improving Socio-Emotional Health for Pupils in Early Secondary Education with Pyramid: A School-Based, Early Intervention Model. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89 (1), 111–130. doi:10.1111/bjep.12225

Jones, S. M., Barnes, S. P., Bailey, R., and Doolittle, E. J. (2017). Promoting Social and Emotional Competencies in Elementary School. Future Child. 27 (1), 49–72. doi:10.1353/foc.2017.0003

Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., and Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 54 (4), 250–270. doi:10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645

Kaptein, S., Jansen, D. E., Vogels, A. G., and Reijneveld, S. A. (2008). Mental Health Problems in Children with Intellectual Disability: Use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 52 (Pt 2), 125–131. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00978.x

Kaya, M., and Erdem, C. (2021). Students' Well-Being and Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis Study. Child. Ind. Res. 14 (5), 1743–1767. doi:10.1007/s12187-021-09821-4

Klauer, K. J. (2014). Training des induktiven Denkens - Fortschreibung der Metaanalyse von 2008. Z. für Pädagogische Psychol. 28 (1–2), 5–19. doi:10.1024/1010-0652/a000123

Kusché, C. A., Greenberg, M. T., and Beilke, B. (1988). The Kusche Affective Interview. Washington: University of Washington: Department of Psychology.

Kusché, C. A. (1984). The Understanding of Emotion Concepts by Deaf Children: An Assessment of an Affective Education Curriculum.

Luckner, J. L., and Movahedazarhouligh, S. (2019). Social-Emotional Interventions with Children and Youth Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing: A Research Synthesis. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 24 (1), 1–10. doi:10.1093/deafed/eny030

Lynne Lane, K. (1999). Young Students at Risk for Antisocial Behavior: The Utility of Academic and Social Skills Interventions. J. Emotional Behav. Disord. 7 (4), 211–223. doi:10.1177/106342669900700403

McClowry, S. G., Snow, D. L., and Tamis-LeMonda, C. S. (2005). An Evaluation of the Effects of INSIGHTS on the Behavior of Inner City Primary School Children. J. Prim. Prev. 26 (6), 567–584. doi:10.1007/s10935-005-0015-7

McCoy, S., and Banks, J. (2012). Simply Academic? Why Children with Special Educational Needs Don't like School. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Edu. 27 (1), 81–97. doi:10.1080/08856257.2011.640487

Meadow, K. P. (1983). Revised Manual. Meadow/Kendall Social-Emotional Assessment Inventory for Deaf and Hearing-Impaired Children. Washington, DC: Pre-College Programs, Gallaudet Research Institute.

Merrell, K. W. (2010). Linking Prevention Science and Social and Emotional Learning: The Oregon Resiliency Project. Part a Spec. Issue Using Prev. Sci. Address Ment. Health Issues Schools 47 (1), 55–70.

Miller, F. G., Johnson, A. H., Yu, H., Chafouleas, S. M., McCoach, D. B., Riley-Tillman, T. C., et al. (2018). Methods Matter: A Multi-Trait Multi-Method Analysis of Student Behavior. J. Sch. Psychol. 68 (June), 53–72. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2018.01.002

Morganti, A., Pascoletti, S., and Signorelli, A. (2019). Index for Social Emotional Technologies: Challenging Approaches to Inclusive Education. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351185073

Morrison, J. M., Sullivan, F., Murray, E., and Jolly, B. (1999). Evidence-Based Education: Development of an Instrument to Critically Appraise Reports of Educational Interventions. Med. Educ. 33 (12), 890–893. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00479.x

Moy, G., Polanin, J. R., McPherson, C., and Phan, T.-V. (2018). International Adoption of the Second Step Program: Moderating Variables in Treatment Effects. Sch. Psychol. Int. 39 (4), 333–359. doi:10.1177/0143034318783339

Ohl, M., Fox, P., and Mitchell, K. (2013). Strengthening Socio-Emotional Competencies in a School Setting: Data from the Pyramid Project. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 83 (3), 452–466. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02074.x

Osher, D., Kidron, Y., Brackett, M., Dymnicki, A., Jones, S., and Weissberg, R. P. (2016). Advancing the Science and Practice of Social and Emotional Learning. Rev. Res. Edu. 40 (1), 644–681. doi:10.3102/0091732X16673595

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., MulrowMulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 Explanation and Elaboration: Updated Guidance and Exemplars for Reporting Systematic Reviews. Bmj 1, n160. doi:10.1136/bmj.n160

Phipps, S., and Steele, R. (2002). Repressive Adaptive Style in Children with Chronic Illness. Psychosom Med. 64 (1), 34–42. doi:10.1097/00006842-200201000-00006

Pons, F., and Harris, P. L. (2000). Test of Emotion Comprehension – TEC. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford.

Pons, F., Doudin, P. L., and Harris, P. L. (2004). “La compréhension des émotions:,” in Les émotions à l'école edited by Louise Lafortune, Pierre-André Doudin, Fracisco Pons and Dawson R. Hancock (Sainte-Foy, France: Presses de l’Université du Québec), 7–32. doi:10.2307/j.ctv18pgxjg.4

Ribordy, S. C., Camras, L. A., Stefani, R., and Spaccarelli, S. (1988). Vignettes for Emotion Recognition Research and Affective Therapy with Children. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 17 (4), 322–325. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1704_4

Robinson, E. A., Eyberg, S. M., and Ross, A. W. (1980). The Standardization of an Inventory of Child Conduct Problem Behaviors. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 9 (1), 22–28. doi:10.1080/15374418009532938

Siddiqui, N., and M. Ventista, O. (2018). A Review of School-Based Interventions for the Improvement of Social Emotional Skills and Wider Outcomes of Education. Int. J. Educ. Res. 90 (1), 117–132. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2018.06.003

Sklad, M., Diekstra, R., Ritter, M. D., Ben, J., and Gravesteijn, C. (2012). Effectiveness of School-Based Universal Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Programs: Do They Enhance Students' Development in the Area of Skill, Behavior, and Adjustment? Psychol. Schs. 49 (9), 892–909. doi:10.1002/pits.21641

Skrzypiec, G., Askell-Williams, H., Slee, P., and Rudzinski, A. (2016). Students with Self-Identified Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (Si-SEND): Flourishing or Languishing!. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Edu. 63 (1), 7–26. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2015.1111301

Smith, S. W., Daunic, A. P., Aydin, B., Van Loan, C. L., Barber, B. R., and Taylor, G. G. (2016). Effect of Tools for Getting along on Student Risk for Emotional and Behavioral Problems in Upper Elementary Classrooms: A Replication Study. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 45 (1), 73–92. doi:10.17105/SPR45-1.73-92

Sullivan, A. L., and Simonson, G. R. (2016). A Systematic Review of School-Based Social-Emotional Interventions for Refugee and War-Traumatized Youth. Rev. Educ. Res. 86 (2), 503–530. doi:10.3102/0034654315609419

Susanne, S. (2021). “Inclusive and Special Education in Europe,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Inclusive and Special Education. Editors U. Sharma, and S. Salend (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 807–819. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1230

Susanne, S. (2018). “Peer-relaNons of Students with Special Educational Needs in Inclusive Education,” in Dirib Cittadinanza Inclusione. Editors S. Polenghi, M. Fiorucci, and L. Agostinetto (Rovato: Pensa MultiMedia), 15–24. Available at: https://www.siped.it/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018-Roma-Ab.pdf

Tang, J. S. Y., Chen, N. T. M., Falkmer, M., Bӧlte, S., and Girdler, S. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Social Emotional Computer Based Interventions for Autistic Individuals Using the Serious Game Framework. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 66 (10), 101412. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2019.101412

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting Positive Youth Development through School-Based Social and Emotional Learning Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Follow-Up Effects. Child. Dev. 88 (4), 1156–1171. doi:10.1111/cdev.12864

Ullebø, A. K., Posserud, M.-B., Heiervang, E., Gillberg, C., and Obel, C. (2011). Screening for the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Phenotype Using the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 20 (9), 451–458. doi:10.1007/s00787-011-0198-9

Walker, H. M., and Severson, H. H. (1992). Systematic Screening for Behavior Disorders (SSBD). Second Edition. Boston Ave: Sopris West, 1140.

Walker, H. M. (1976). Walker Problem Behavior Identification Checklist (Manual). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Weare, K., and Nind, M. (2011). Mental Health Promotion and Problem Prevention in Schools: What Does the Evidence Say? Health Promot. Int. 26 (Suppl. 1), i29–69. doi:10.1093/heapro/dar075

Wigelsworth, M., Humphrey, N., and Lendrum, A. (2013). Evaluation of a School-wide Preventive Intervention for Adolescents: The Secondary Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning (SEAL) Programme. Sch. Ment. Health 5 (2), 96–109. doi:10.1007/s12310-012-9085-x

Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., Oldfield, J., Scott, A., Ten Bokkel, I., Tate, K., et al. (2016). The Impact of Trial Stage, Developer Involvement and International Transferability on Universal Social and Emotional Learning Programme Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Cambridge J. Edu. 46 (3), 347–376. doi:10.1080/0305764X.2016.1195791

Zweers, I., de Schoot, R. A. G. J. v., Tick, N. T., Depaoli, S., CliftonClifton, J. P., de Castro, B. O., et al. (2021). Social-emotional Development of Students with Social-Emotional and Behavioral Difficulties in Inclusive Regular and Exclusive Special Education. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 45 (1), 59–68. doi:10.1177/0165025420915527

Keywords: soical-emotional learning, special educational needs, systematic literature review, school-based, interventions

Citation: Hassani S and Schwab S (2021) Social-Emotional Learning Interventions for Students With Special Educational Needs: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Educ. 6:808566. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.808566

Received: 03 November 2021; Accepted: 30 November 2021;

Published: 21 December 2021.

Edited by:

Brahm Norwich, University of Exeter, United KingdomReviewed by:

Joanne Banks, Trinity College Dublin, IrelandGarry Squires, The University of Manchester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Hassani and Schwab. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sepideh Hassani, c2VwaWRlaC5oYXNzYW5pQHVuaXZpZS5hYy5hdA==

Sepideh Hassani

Sepideh Hassani Susanne Schwab

Susanne Schwab