Overview

A previous study analyzed the names of babies born in Japan between 2004 and 2018 and demonstrated that common writings have many variations in readings, which makes it difficult to choose the correct reading at first glance (Ogihara, 2021c). The study provides empirical evidence of the difficulties in reading recent Japanese names correctly. The current article answers three questions on Ogihara (2021c). Specifically, I explain 1) it is still difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly even if one tries to remember the most frequent readings of names 2) specific numbers of reading variations are not important, and 3) how we should deal with these difficulties. This new information would certainly help to further comprehend the difficulties in reading recent Japanese names correctly, which contributes to a better understanding of names and naming practices not only in Japan but also across the entire Sinosphere.

Introduction

Ogihara (2021c) analyzed the names of babies born in Japan between 2004 and 2018 and demonstrated that common writings have many variations in readings, which makes it difficult (or almost impossible) to choose the correct reading. For instance, one of the common writings for boys, 大翔 had 18 variations in reading, and for girls, 結愛 had 14 variations in reading. These variations differed remarkably in pronunciation, length, and meaning. This shows that it is difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly at first glance. Prior research had mentioned these difficulties (e.g., Sakata, 2006; Sato, 2007; Kobayashi, 2009; Ohto, 2012), but they had not been empirically examined. Thus, the study provides empirical evidence of the difficulties in reading recent Japanese names correctly at first glance, contributing to a better understanding of names and naming practices not only in Japan but also across the entire Sinosphere (the vast regions where Chinese characters are/were used).

I found questions on this study that are not discussed in Ogihara (2021c) and are helpful to better understand Japanese names and naming practices. Thus, in this article, I answer some of them and add further explanations for the difficulties in reading recent Japanese names correctly. These explanations would contribute to a further understanding of names and naming practices not only in Japan but also across the entire Sinosphere.1

1. Is It Truly Difficult to Read Recent Japanese Names Correctly?

Question

One saw the distribution of readings of the name 結愛 [Figure 1; Figure 5 of Ogihara (2021c)] and insisted that the name is easy to read because the frequency of the most common reading, Yua, was approximately 60%. In other words, even if one does not know the correct reading of this name, reading it as Yua will be correct with a 60% probability. This questions whether it is truly difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly.

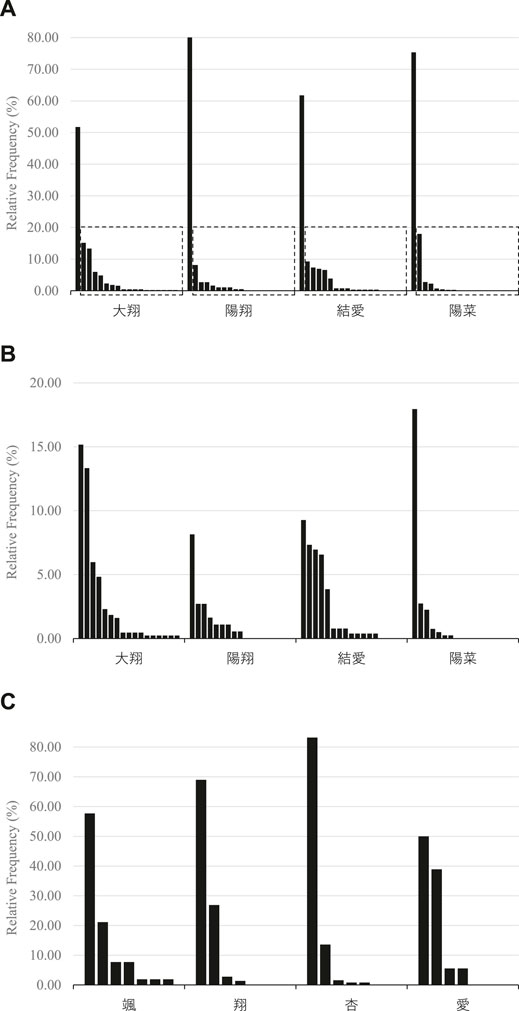

FIGURE 1. Relative frequencies of each reading. (A) All readings (two-letter names). (B) Without the most frequent readings [within the dotted frames of panel (A)]. (C) All readings (one-letter names).

Response

This is incorrect for at least four reasons. It is still difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly, even if one tries to remember the most frequent readings of names.

First, frequencies of the most common readings remarkably differ in names, and it is not always the case that the most common readings have high frequencies. It is important to understand that distributions of name readings in Japan vary widely for names. Indeed, the distributions of reading variations of the eight names that were examined in Ogihara (2021c) are different from each other (Figure 1). For example, the frequencies of the most common readings range from 50.00% (愛: Ai) to 83.20% (杏: An). Moreover, it is not always true that the frequency of the most common reading is much higher than those of the remaining readings. The distribution of the readings of 愛 is one example of this [Figure 1; Figure 7 of Ogihara (2021c)]. The most frequent reading was Ai (50.00%), but the second most frequent reading was Mana (38.89%), which was also a frequent reading and its frequency was close to that of the most frequent reading.

Second, distributions of reading variations of names other than those analyzed in Ogihara (2021c) are still unclear. As stated above, distributions of reading variations differ in names. Ogihara (2021c) demonstrated the most common readings for the eight popular writings, but other writings have not been investigated and clarified. Thus, it is still difficult to read other names. The distributions of the readings became clear “after” the study was conducted. Before the study, the distributions had been unknown. In this sense, one of the purposes of Ogihara (2021c) was partially fulfilled, which was to help people read Japanese names correctly.

Third, even if all the most common readings of writings are clear (though this has not been achieved), it is difficult (or almost impossible) to remember all the most common readings of every name. Because there are too many writings, this is not realistic.

Fourth, even if one remembers all the most common readings of every name (though this is impractical), they can change in the future. It is also important to know that distributions of name readings are changeable over time. Thus, the most common readings are not fixed, which leaves it difficult to read Japanese names correctly.

Yet, it should be noted that there may be individual differences in the difficulties of reading recent Japanese names correctly. Not every individual has the difficulties to the same extent. For example, people who engage in educational or medical services may be somewhat better at reading recent Japanese names correctly at first sight. Teachers, instructors, school staff, doctors, nurses, and hospital staff are some examples. This is because they see many recent names with both their writings and readings, store them, and update them regularly. In other words, they have a larger amount of data on baby names and the distributions of their readings stored in their own heads. Thus, they may have better predictions for readings of names. Yet, it is still difficult even for them to read recent names correctly at first sight.

2. Are Specific Numbers of Reading Variations Important?

Question

Ogihara (2021c) analyzed and revealed the distributions of reading variations of eight popular writings. For example, the study showed 18 variations of readings of the writing 大翔 and 14 variations of readings of the writing 結愛.

Some have emphasized these specific numbers of reading variations. For instance, one argued whether a name with seven reading variations is more difficult to read correctly than a name with five reading variations. This questions whether such specific numbers regarding reading variations matter.

Response

Specific numbers of reading variations are not very important. As written in Ogihara (2021c), the study indicated specific numbers because it was necessary to empirically demonstrate the difficulties of reading recent Japanese names and provide readers a clearer understanding of the difficulties. Ogihara (2021c) did not collect all names that were given to newborn babies in Japan between 2004 and 2018. Thus, the numbers of reading variations are the results of data (Ogihara, 2020a; Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company, 2020) examined in Ogihara (2021c), and they are not necessarily consistent with those of populations in interest (all names that were given to newborn babies in Japan between 2004 and 2018).

Thus, if more names are investigated, more variations of readings will likely be found. Indeed, there are other readings than those listed in Ogihara (2021c). For example, 大翔 was read Takeru and 結愛 was read Yuria for the same period, both of which were not found in Ogihara (2021c).

Further, numbers of reading variations can change over time. As stated above, distributions of name readings are changeable over time. New readings can appear in the future, which increases the number of reading variations. Similarly, some readings may be less frequently given to Chinese characters, which decreases the number of reading variations. Thus, specific numbers of reading variations are not very important.

3. So, How Should We Deal With the Difficulties?

Question

One agreed with the difficulties of reading recent Japanese names correctly and then asked about how we should deal with these difficulties. Reading names correctly is important in daily communication. Misreading names should be avoided because it is generally considered to be rude in Japan.2 This question is also important for non-native Japanese speakers who learn Japanese names, language, and culture.

Response

I recommend four strategies to face these difficulties.

First, accepting the difficulties is necessary. The difficulties are somewhat shared in Japan, but there seem to be variations in some layers such as generation and region. Accepting the difficulties and understanding that the difficulties are shared should decrease the pressure to read names without mistakes. It would be particularly effective for non-native Japanese speakers to know that even native Japanese speakers cannot read recent Japanese names correctly.

Second, explicitly asking how a name is read is recommended. When there are many possibilities in readings and no hints as to choosing the correct one, asking for the correct reading is the most straightforward solution. As stated above, at times even native Japanese speakers cannot read names correctly at first glance and misreading names is generally considered to be rude in Japan. Thus, asking for a correct reading before making mistakes is basically not impolite in Japan.

Third, it is effective to learn patterns of reading names in Japan (for a summary, see Ogihara, 2015; 2021b). For example, 海 (meaning marine) is read as Marin and 月 (meaning moon) is read as Runa. These are based on a strategy to read Chinese characters as foreign words (e.g., English, Latin, and French) that correspond to the semantic meaning. The percentages of unique names have increased in Japan (Ogihara, 2021a; Ogihara, in press; Ogihara et al., 2015). Thus, capturing how to read uncommon names would be beneficial. This increases the possibility of reading Japanese names correctly. Related to the second point above, it is also effective to ask about the origins and meanings of names, which helps one to understand and remember the names. Yet, it is still difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly at first sight because predicting which pattern is applied to a name is difficult (or almost impossible).

Fourth, knowing more names and updating distributions of reading variations would increase the probability of reading Japanese names correctly. In particular, it is effective to learn how to read common writings as it was conducted for the eight writings in Ogihara (2021c). However, this is difficult for ordinary people who do not have many opportunities to see recent Japanese names.

As stated above, professionals in education and medical services may be better at reading recent names correctly. This is because they have their own databases of names in their heads, update them, and communicate with people (e.g., students, patients) using them in their workplaces, which in turn causes them to implement the four strategies explained above (accepting the difficulties, asking how a name is read explicitly, learning patterns of reading names in Japan, knowing more names, and updating distributions of reading variations).

Discussion

This article answers three questions on Ogihara (2021c). Specifically, I explain 1) it is still difficult to read recent Japanese names correctly even if one tries to remember the most frequent readings of names 2) specific numbers of reading variations are not important, and 3) how we should deal with these difficulties. This new information would certainly be helpful for further comprehending the difficulties in reading recent Japanese names correctly, which contributes to a better understanding of names and naming practices not only in Japan but also across the entire Sinosphere.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1For example, revealing how people in Japan give names to babies enables comparisons with naming practices in other countries in the Sinosphere. Indeed, such a comparison shows substantial cultural differences and similarities in naming practices between Japan and China (e.g., Ogihara, 2020b; Bao et al., 2021), which deepens our understanding of naming behaviors, languages, and cultures.

2When how to pronounce/read Chinese characters of Japanese names [“furigana”: “furi” means giving and “gana” comes from “(hira)gana” or “(kata)kana”] is explicitly referred, people do not mistake (Ogihara, 2021c). However, furigana is not always explicitly referred.

References

Bao, H. W., Cai, H., Jing, Y., and Wang, J. (2021). Novel Evidence for the Increasing Prevalence of Unique Names in China: A Reply to Ogihara. Front. Psychol. 12, 731244. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731244

Kobayashi, Y. (2009). Nazuke No Sesoushi. Koseitekina Namae Wo Fi-Rudowa-Ku [Social History of Naming. Fieldwork of Unique Names]. Tokyo: Fukyosya.

Meiji Yasuda Life Insurance Company (2020). Umare Doshi Betsu No Namae Chosa [Annual Survey on Baby Names]. Available at: http://www.meijiyasuda.co.jp/enjoy/ranking/index.html.

Ogihara, Y. (2015). Characteristics and Patterns of Uncommon Names in Present-Day Japan. J. Hum. Environ. Stud. 13, 177–183. doi:10.4189/shes.13.177

Ogihara, Y. (2020a). Baby Names in Japan, 2004-2018: Common Writings and Their Readings. BMC Res. Notes 13, 553. doi:10.1186/s13104-020-05409-3

Ogihara, Y. (2020b). Unique Names in China: Insights from Research in Japan-Commentary: Increasing Need for Uniqueness in Contemporary China: Empirical Evidence. Front. Psychol. 11, 2136. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02136

Ogihara, Y. (2021a). Direct Evidence of the Increase in Unique Names in Japan: The Rise of Individualism. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2, 100056. doi:10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100056

Ogihara, Y. (2021b). How to Read Uncommon Names in Present-Day Japan: A Guide for Non-native Japanese Speakers. Front. Commun. 6, 631907. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2021.631907

Ogihara, Y. (2021c). I Know the Name Well, but Cannot Read it Correctly: Difficulties in reading Recent Japanese Names. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 8, 151. doi:10.1057/s41599-021-00810-0

Ogihara, Y. (in Press). Common Names Decreased in Japan: Further Evidence of an Increase in Individualism. Exp. Results. 3, 1–13. doi:10.1017/exp.2021.27

Ogihara, Y., Fujita, H., Tominaga, H., Ishigaki, S., Kashimoto, T., Takahashi, A., et al. (2015). Are Common Names Becoming Less Common? the Rise in Uniqueness and Individualism in Japan. Front. Psychol. 6, 1490. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01490

Ohto, O. (2012). Nihon Jin No Sei, Myouji, Namae. Jinmeini Kizamareta Rekisi. [Japanese Family Names, Last Names and First Names. A History of People’s Names]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Sakata, S. (2006). Myouji to Namae No Rekishi [The History of Family and First Names]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan.

Keywords: name, reading, writing, pronunciation, Chinese character, uniqueness, Japan, Sinosphere

Citation: Ogihara Y (2022) Further Explanations for Difficulties in Reading Recent Japanese Names Correctly. Front. Educ. 6:799119. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.799119

Received: 21 October 2021; Accepted: 28 December 2021;

Published: 07 February 2022.

Edited by:

Antonio P. Gutierrez de Blume, Georgia Southern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Han-Wu-Shuang Bao, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, ChinaCopyright © 2022 Ogihara. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuji Ogihara, eW9naWhhcmFAcnMudHVzLmFjLmpw

Yuji Ogihara

Yuji Ogihara