- Department of Elementary and Primary Education, University College of Teacher Education Carinthia, Viktor Frankl College, Klagenfurt, Austria

Many assume that school shutdowns in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly impaired students’ achievement and self-determined motivation. Of greatest concern given the sudden shift to distance learning are students with inadequate access to digital media and insufficient experience organizing learning processes independently—for example, first and second graders. This study used a quasi-experiment with 206 elementary students to investigate differences in reading comprehension and self-determined reading motivation of students who attended grades one and two during or before the pandemic. Surprisingly, the results revealed no differences in reading comprehension and reading motivation between the groups, contradicting the assumption that the pandemic-driven shift to distance learning would inevitably impair young students’ achievements and self-determined motivation.

Introduction

In many countries, the COVID-19 pandemic necessitated school shutdowns. Numerous reports followed these shutdowns that students had been severely affected by the shift to distance learning. It is important to gain an understanding of the impact the pandemic had on student learning, because such knowledge may help to initiate appropriate action to compensate for eventual COVID-related detriments in students’ achievement. In Austria, elementary students switched to home-based learning in March 2020 and again in November 2020 (Federal Ministry - Education, Science and Research, 2021). Thus, in the 2019–2020 school year, elementary students had 8 weeks of distance learning, and in 2020–2021, with some regional differences, students stayed away from school for at least 14 weeks. However, the school shutdowns were at no time absolute. Students could attend school even during the shutdowns, and many did when there was no childcare option. Specifically, students with poor German language knowledge were invited to attend school even during school shutdown to ensure adequate learning progress of these students (Federal Ministry—Education, Science and Research, 2020). Nevertheless, for most students, the school shutdowns meant new restrictions and changes such as being unable to meet with friends and classmates and limited contact with their teachers. Younger students especially badly missed their peers and teachers (Ewing and Cooper, 2021; Flynn et al., 2021).

The teaching itself also changed as teachers sought new ways to get in touch with their students. When choosing methods for distance learning, they had to consider the students’ access to technical equipment and skills in handling digital media. The younger students might have had limited access to digital devices and not yet acquired the necessary skills for self-organized learning in the home environment. Empirical data suggest that only about 20% of the schoolteachers provided regular online lessons at least once a week during the school shutdown, and nearly 70% did not use digital devices to provide online lessons (König et al., 2020). Most schoolteachers relied primarily on standard worksheets and lesson plans but maintained contact with students and parents via social media. Educators and parents alike worried that students’ emotional well-being and achievement might have suffered because of the pedagogic changes during the pandemic (e.g., Aurini and Davies, 2021; Minkos and Gelbar, 2020), albeit with great interindividual variance (Tomasik et al., 2021).

Learning to read is an important goal for first and second graders. In Austria, students are not taught to read in kindergarten, only in elementary school. Therefore, most students enter grade one with little or no reading skills. The Austrian curriculum for elementary schools provides that students should acquire basic reading skills during their first 2 years of school (Federal Ministry—Education, Science and Research, 2012). Thus, the pandemic-related school shutdowns had the potential to significantly impede the reading progress of the first and second graders who started school in the fall of 2019. Many expected that the pandemic would dramatically impact those children’s reading achievements. And indeed, first empirical data have suggested that the school shutdowns might have had an especially great impact on students’ reading skills in the early grades (Wyse et al., 2020). This study examined whether this was the case.

Reading Skills and Distance Learning During COVID-19

In 2020, researchers conducted a survey in the German-speaking countries of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland soliciting the perspectives of various stakeholders, including parents, students, school staff (e.g., teachers, administrators, authorities, and support), policymakers, and educational institutes. The School Barometer found that many students spent less time engaged in formal learning during the first school shutdown in March 2020 than during regular on-site schooling (Huber and Helm, 2020; König et al., 2020). This would suggest that students spent less time reading—and learning to read. Because the time spent reading is an important predictor of students’ reading comprehension (Allington, 2002), decreased time spent reading could negatively affect the students’ reading comprehension. We are accustomed to thinking of the young as digital natives—they have grown up surrounded by and using myriad devices, applications, and forms of connectivity. However, not all students have easy access to technical equipment or internet connections. Furthermore, most first graders are unfamiliar with the use of communication technologies necessary for distance learning, such as videoconferencing applications (Drexler, 2018; Huber and Helm, 2020; König et al., 2020). Many younger students have found online learning challenging and need help from their parents, older siblings, or others (Ewing and Cooper, 2021). Indeed, empirical evidence suggests that only a small percentage of elementary teachers conducted live online lessons. Instead, most elementary teachers developed and distributed lesson plans for the students (Flynn et al., 2021; Huber and Helm, 2020). While evidence suggests that learning plans can effectively substitute for in-person learning (Tomasik et al., 2021), they cannot make up for small-group collaboration. Because collaboration in pairs or small groups positively affects reading comprehension (Guthrie et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2000), the lack of social interactions during distance learning might also have negatively impacted young students’ reading skills (Allington, 2002; Guthrie et al., 2007). Given teachers’ self-reported disinclination to use online communication tools (Huber and Helm, 2020), we can assume that their direct instruction and guidance were severely restricted during distance learning. Direct teacher instruction also fosters students’ reading comprehension (Allington, 2002; Rupley et al., 2009), and its decline during the school shutdowns might also have affected students’ reading comprehension education.

Online distance learning can also hinder teachers’ task individualization, which is more difficult during videoconferences involving whole classes or large groups than in on-site learning. Very young children typically have limited concentration spans, so most education videoconferences are shorter than an in-person lesson; the limited time must be focused on covering material and assigning tasks that apply to the whole class. Although teachers could deliver one-to-one sessions, the amount of time this would require makes this an unrealistic option. Evidence shows that online learning during COVID-19 has been less individualized than regular on-site learning (Ewing and Cooper, 2021). Some teachers have always routinely individualized work packages for each student. However, during the school lockdowns, teachers lacked the easy student access that would enable them to assess the tasks’ adequacy readily, so days might elapse during which the students struggled with ineffectual assignments. Elementary children, especially first graders, benefit from individualized reading instruction (Connor et al., 2013; Förster et al., 2018). Thus, the hiatus in individualization might have affected their reading comprehension development. However, the children who attended school during the lockdown because their families could not spend education-focused time with them during the days probably enjoyed a favorable learning environment with more individual training than their pre-pandemic in-person schooling. Overall, research suggests that the quality of reading instruction for first and second graders decreased during distance learning, even though many parents tried to support their children’s learning (Flynn et al., 2021). More data are needed on the achievement-related outcomes of elementary students during COVID-19.

Self-Determined Reading Motivation and Distance Learning During COVID-19

To investigate how distance learning during COVID-19 might have affected reading motivation, we used the framework of self-determination theory (SDT). SDT holds that highly self-determined types of motivation, such as intrinsic motivation and identified regulation, predict desirable outcomes such as deep-level learning and psychological well-being. Intrinsically motivated behaviors are inherently satisfying and require no external incentives or rewards; we engage in them because we enjoy them. Identified regulation concerns behaviors that might not be inherently pleasant, but we recognize as having value (Ryan and Deci, 2020).

While intrinsic motivation is considered an optimal basis for learning, identified regulation can support learning in domains that are not inherently enjoyable. According to SDT, motivational regulations are enhanced by supports for student’s basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Niemiec and Ryan, 2009; Ryan and Deci, 2020). However, some evidence suggests that the sudden shift to distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has affected basic psychological needs satisfaction. For example, one study found that it negatively affected university students’ basic psychological needs satisfaction and self-determined motivation (Author, submitted). Similarly, a retrospective study by Zaccoletti et al. (2020) found lower academic motivation during the pandemic-related school closures for children in grades 1–9. Extrapolating from these findings, we could expect a decline in self-determined reading motivations among first and second graders related to the school shutdowns. However, as with reading comprehension, we have insufficient data on how the pandemic-related restrictions affected elementary students’ motivational regulations.

Changes in General Conditions Between 2015 and 2019

As this research investigates the impact of the pandemic on the reading skills of first and second graders, it is important to consider changes in general conditions that might have affected student achievement. Beside the school lockdowns changes in general conditions such as educational expenditure or school reform might have affected students’ academic achievements and learning motivation. In Austria expenditure on education has progressively increased since 2000 (Statistik Austria, 2021). However, according to the results of the Progress in Reading Literacy Study the improvement in financial resources has not led to a meaningful improvement in students’ reading comprehension from 2006 to 2016 (M2006 = 538; M2016 = 542; Mullis et al., 2007; Mullis et al., 2017). It is therefore unlikely, that changes in financial resources affected students’ reading comprehension between 2015 and 2019. Another change concerned the implementation of a preparatory program for students with poor German language knowledge. While the resources for language support did not change between 2015 and 2019, in the school year 2018–19 attending a preparatory program became mandatory for students with poor German language knowledge (Federal Ministry—Education, Science and Research, 2019). Before then teachers could decide whether a student should attend a preparatory program or an immersion program with systematic language support, and many schools used both types of language promotion (Author, 2021). Research on the effectiveness of these types of language support is still inconclusive and presumably the quality and the quantity of support matters more than the type of program (Stanat and Cristensen, 2006). Overall, there were some changes in the general conditions in the educational system, but it seems unlikely that they led to meaningful changes in student outcomes. If anything, many fear that the implementation of a compulsory preparatory program for students with poor German language knowledge may have reduced immersion and negatively affected German language acquisition (Thomas et al., in press).

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The tenuous findings regarding the impact of the COVID-related school shutdowns on students’ achievement and self-determined learning motivation inspired the following research questions and hypotheses:

1) Did reading comprehension differ between the students whose first 2 years of school fell during the COVID-19 pandemic and students who had regular on-site lessons during their first 2 years in school?

2) Did self-determined reading motivations differ between students whose first 2 years of school fell during the COVID-19 pandemic and students who had regular on-site lessons during their first 2 years in school?

H1: Students who did (did not) experience pandemic-related shutdowns during their first 2 years of school differed in reading comprehension.

H2: Students who did (did not) experience pandemic-related shutdowns during their first 2 years of school differed in self-determined reading motivations.

To answer these research questions, reading comprehension and self-determined reading motivations of students who started school in fall 2019 and thus, experienced COVID-19 related school shutdowns during their first two school years, were compared with outcomes from students who attended elementary school before the pandemic.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Procedures

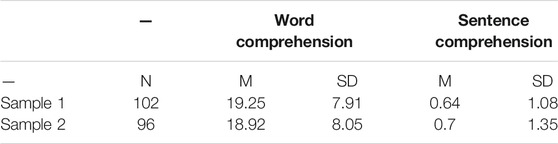

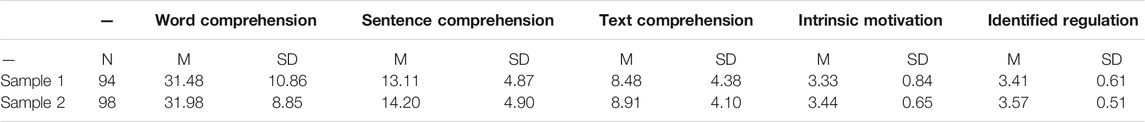

A quasi-experiment was conducted to answer the research questions. The participants were 206 students from five schools: Sample 1 comprised 102 students who started school in the fall of 2015 and experienced no school shutdowns; Sample 2 comprised 104 students who started school in the fall of 2019 and experienced pandemic-related shutdowns in their first and second year of school. As teachers could apply to participate in this research these are convenience samples. Both samples were drawn from the same five schools and thus, students of both samples had comparable social backgrounds. Two schools (four classes, nsample2 = 67, nsample2 = 68) were located in cities, and the other three schools were from rural locations. None of the schools had a catchment area with students from a privileged socioeconomic background. Because student characteristics and teacher characteristics are the most influential predictors of student achievement (Hattie, 2003), it is of great importance for the comparability of the samples that the catchment area and the teachers are the same in both samples. In fall 2015 participating teachers had 16–34 years of teaching experience. This is important because teachers might have gained additional experience from fall 2015 to fall 2019. However, research suggests that increases in teaching experience are associated with additional gains in student achievement only in novice teachers (Burroughs et al., 2019). Therefore, it is unlikely that the additional teaching experience gathered between 2015 and 2019 affected student outcomes. Of the 206 students participating in this study, one child from Sample 2 was excluded from all the analyses because a diagnosis of learning disabilities meant there were confounding differences in reading comprehension development. Therefore, the final sample consisted of 205 students. However, because of school and class changes, COVID-related absences from school, and lack of parental consent, only 186 students participated in both assessments (Table 1). It is important to note that principals of participating schools and participating teachers reported that they contacted parents of children with poor German language knowledge as well as parents with challenging domestic circumstances to let their children attend school during the school shutdown in the 2020–2021 school year.

In Sample 1, 38.2% of the students were female, and 82.4% spoke German as their first language. In Sample 2, 48.5% of the students were female, and 78.6% spoke German as their first language. The differences in sex (χ2 = 2.22, df = 1, p = 0.14) and first language (χ2 = 0.45, df = 1, p = 0.50) were not significant, indicating that the two samples were comparable. At t1, the students’ mean age was 7.02 years (SD = 0.55). In both samples, the students’ reading comprehension and self-determined reading motivation were assessed at the end of grade one (t1) and the end of grade two (t2). Data collection was approved by the relevant school authorities and was conducted during regular classes by the author. Participating students had to provide their parents’ written consent.

Measures

Reading Comprehension in grade one was measured with two subtests assessing word comprehension and sentence comprehension. Word comprehension was assessed with 63 word–picture assignment tasks in which the children chose one word out of four to correspond with the picture; sentence comprehension was assessed using a maze format with five response options for 17 items. For each subtest, we gave the students 3 minutes of working time. The second graders completed a standardized reading comprehension test called Ein Leseverständnistest für Erst- bis Sechstklässler (Reading Comprehension Test for First to Sixth Graders) (ELFE 1-6; Lenhard and Schneider, 2006), validated for use with students in grades 1–6. The ELFE 1–6 comprised three subtests to assess word comprehension, sentence comprehension, and text comprehension. All three subtests used a multiple-choice answer format. The children had 3 minutes (each) to complete the word-comprehension and sentence-comprehension subtests and 7 minutes to complete the text-comprehension subtest.

Reading Motivations were measured at the end of grade two with an adapted version of the Scales Assessing Motivational Regulation for Learning (SMR-L, Thomas and Müller, 2016). The SMR-L measures intrinsic, identified, introjected, and external motivational regulation with three items per scale answered on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “not true” (1) to “true” (4). The SMR-L was validated with children from grades three to eight and tested in various pilot studies with children from grade two (Thomas, 2015; Thomas and Müller, 2016). The present study used only the items assessing intrinsic motivation and identified regulation.

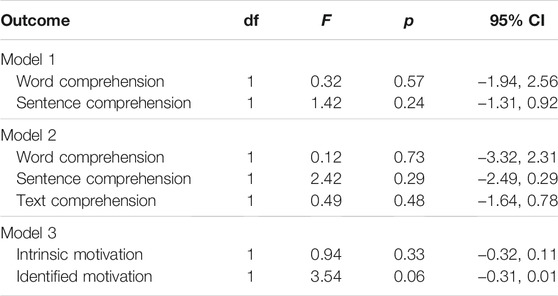

Statistical Analyses

Multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was used to assess the differences in reading achievement and reading motivation between the students in Sample 1 and Sample 2. First, we tested the assumptions for all outcome variables. For outcome variables at t1, the Box’s M test (p = 0.18) and the Levene test (pword comprehension = 0.57; psentence comprehension = 0.24) indicated that the covariances and error variances did not differ significantly between groups. Thus, the application of the MANOVA was adequate for all the variables at t1 (Model 1). For the reading comprehension variables at t2, the Box’s M test (p = 0.18) was not significant, indicating adequate congruence between the covariance matrices. Levene’s tests yielded non-significant results for the variables assessing reading comprehension (pword comprehension = 0.07; psentence comprehension = 0.86; ptext comprehension = 0.50). However, the Levene’s test for motivational regulations was significant (pintrinsic motivation = 0.02; pidentified regulation = 0.04). Therefore, a MANOVA was run only for the outcome variables assessing reading comprehension (Model 2) and a Welch’s t-test was applied for intrinsic motivation and identified regulation (Model 3). Because empirical evidence suggests that second-language learners might have lower reading comprehension scores (Stanat and Cristensen, 2006), I extended Models 1 and 2 to include first language (German vs. other) as a covariate (Model 4, Model 5). Pillai trace was used to evaluate the significance because it has adequate power for similar group sample sizes (Mayers, 2013).

Results

An inspection of the dependent variable descriptive statistics shows that means were very similar for both samples (Tables 2, 3). Model 1 showed that the students’ word comprehension and sentence comprehension at t1 did not differ between the two samples (Pillai trace = 0.00, F (2,194) = 0.43, p = 0.65). These findings were confirmed for both dependent variables. Likewise, reading competencies at t2 did not differ between the samples (Pillai trace = 0.03, F (3,188) = 1.62, p = 0.19; Model 2). One-on-one tests confirmed these results. In Model 3, a Welch’s test also yielded non-significant results for the motivational outcomes at t2. Relevant coefficients for Models 1 to 3 are displayed in Table 4. Thus, neither at t1 nor t2 were there any differences in reading competencies and reading motivations between the students in Sample 1 and Sample 2. Even when first language was added as a covariate (Models 4 and 5), the findings were not affected (Model 4: Pillai trace = 0.01, F (2,193) = 0.48, p = 0.62; Model 5: Pillai trace = 0.03, F (3,187) = 0.03, p = 0.16).

Discussion

This study investigated differences in reading comprehension and reading motivation among students who did or did not experience pandemic-related school shutdowns during their first 2 years of school. Theoretical considerations complemented by some empirical findings suggested that students who attended grades one and two during the pandemic would have lower reading competencies and lower self-determined reading motivations compared to students who attended elementary school before COVID-19. However, dissenting hypotheses H1 and H2, this study found no evidence that the pandemic-related shutdowns had adversely affected these students’ reading competencies or self-determined reading motivations. Thus, the anticipated declines in first and second graders’ reading skills did not manifest in this student population. Moreover, as the non-significant Levene’s tests showed, the interindividual differences in reading comprehension did not increase during the pandemic.

We must, however, consider that none of the schools was located in a large city. While their students’ socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds were diverse, none of the schools had a catchment area with a very low socioeconomic background or a high percentage of immigrants. Therefore, these results should not be applied to those populations. However, the students in this study are drawn from low to medium socioeconomic backgrounds and findings can be generalized to these populations. Another limitation of this study is, that it cannot completely be ruled out that changes in general conditions might have affected changes in student achievement. As already discussed, an increase in general expenditure on Austria’s education system was not associated with students reading comprehension between 2006 and 2016 (Mullis et al., 2007; Mullis et al., 2017`) and it is thus unlikely that it affected students’ achievement between 2015 and 2019. The shift of resources for children with poor knowledge of the German language from school autonomous use to mandatory implementation of preparatory programs probably has no impact on the findings because empirical evidence suggests that there is no difference in student achievement for immersion with systematic language support programs and preparatory programs (Stanat and Cristesen., 2006). Moreover, only one of the schools was affected by this reform. Before 2018 this school had both programs and dedicated about 50% of resources for language promotion to each of them (school principal, personal communication, October 11, 2021). The shift to compulsory preparatory programs is perceived as detrimental for the development of children with poor German language knowledge by experts and by teachers (Thomas et al., in press) and is therefore unlikely to have contributed to the surprisingly good performance of sample 2.

While the results of this study certainly are good news, this study cannot explain which factors contributed to these findings. One possibility is that because the school shutdowns meant that the students were not involved in non-academic classes (e.g., gym, art), the teachers had more time to focus on teaching reading. Another possibility is that the teachers used the advantage of smaller classes (those students who attended school even during school shutdown) to work intensively on their reading comprehension. The Austrian Ministry – Education, Science, and Research (2021) recommended that students with poor knowledge in the language of instruction should attend school during the school shutdown in the 2020–2021 school year, and according to statements of participating principals and teachers, this recommendation was implemented successfully. Thus, many students with underprivileged backgrounds attended school during the second school shutdown and probably received special attention during this time. A third possibility is that the teachers’ specialized lesson plans for the shutdowns effectively substituted in-person learning (Tomasik et al., 2021). Parental involvement also likely played a role. While this study did not include such data, there is evidence that parental support increased meaningfully during school shutdowns (Flynn et al., 2021), which might have compensated for any shortcomings of the enforced distance learning.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

AT desiged this research, conducted the data collection, conducted the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University College of Teacher Education Carinthia, Viktor Frankl College.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allington, R. L. (2002). What I've Learned about Effective Reading Instruction:From a decade of studying exemplary elementary classroom teachers. Phi Delta Kappan 83 (10), 740–747. doi:10.1177/003172170208301007

Aurini, J., and Davies, S. (2021). COVID-19 School Closures and Educational Achievement Gaps in Canada: Lessons from Ontario Summer Learning Research. Can. Rev. Sociol. 58 (2), 165–185. doi:10.1111/cars.12334

Burroughs, N., Gardner, J., Lee, Y., Guo, S., Touitou, I., Jansen, K., et al. (2019). Teaching for Excellence and Equity: Analyzing Teacher Characteristics, Behaviors and Student Outcomes with TIMSS. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Connor, C. M., Morrison, F. J., Fishman, B., Crowe, E. C., Al Otaiba, S., and Schatschneider, C. (2013). A Longitudinal Cluster-Randomized Controlled Study on the Accumulating Effects of Individualized Literacy Instruction on Students' reading from First through Third Grade. Psychol. Sci. 24 (8), 1408–1419. doi:10.1177/0956797612472204

Drexler, W. (2018). “Personal Learning Environments in K–12,” in Handbook of Research on K–12 Online and Blended Learning. Editors K. Kennedy, and R. E. Ferdig. 2nd ed. (Pittsburgh, PA: ETC Press), 151–162.

Ewing, L.-A., and Cooper, H. B. (2021). Technology-enabled Remote Learning during Covid-19: Perspectives of Australian Teachers, Students and Parents. Technol. Pedagogy Edu. 30 (1), 41–57. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2020.1868562

Federal Ministry - Education, Science and Research (2019). Deutschförderklassen und Deutschförderkurse (German remedial classes and German remedial courses).

Federal Ministry - Education, Science and Research (2021). Schulbetrieb 2020/21 (Running of the Schools 2020/21). Available at: https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/Themen/schule/beratung/corona/schulbetrieb20210118.html (Accessed August 30, 2021).

Federal Ministry - Education, Science and Research (2020). Schulbetrieb ab dem 17, November 2020 (Running of the Schools as from November 17, 2020). Available at: https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/dam/jcr:5958d150-eaf6-42a1-be65-b575e8eb959f/schulbetrieb_20201117_dl.pdf (Accessed November 15, 2020).

Federal Ministry - Education, Science and Research (2012). Volksschul-Lehrplan (Elementary School Curriculum). Available at: https://bildung.bmbwf.gv.at/schulen/unterricht/lp/lp_vs_gesamt_14055.pdf?61ec07 (Accessed August 30, 2021).

Flynn, N., Keane, E., Davitt, E., McCauley, V., Heinz, M., and Mac Ruairc, G. (2021). 'Schooling at Home' in Ireland during COVID-19': Parents' and Students' Perspectives on Overall Impact, Continuity of Interest, and Impact on Learning. Irish Educ. Stud. 40 (2), 217–226. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558

Förster, N., Kawohl, E., and Souvignier, E. (2018). Short- and Long-Term Effects of Assessment-Based Differentiated reading Instruction in General Education on reading Fluency and reading Comprehension. Learn. Instruction 56, 98–109. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.04.009

Guthrie, J. T., Hoa, A. L. W., Wigfield, A., Tonks, S. M., Humenick, N. M., and Littles, E. (2007). Reading Motivation and reading Comprehension Growth in the Later Elementary Years. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 32 (3), 282–313. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.004

Hattie, J. A. C. (2003). “Teachers Make a Difference: What Is the Research Evidence? Paper Presented at the Building Teacher Quality: What Does Research Tell Us?”,inACER Research conference, Melbourne, Australia, October 19-21, 2003. Available at: https://research.acer.edu.au/research_conference_2003/4/ (Accessed October 8, 2021).

Huber, S. G., and Helm, C. (2020). COVID-19 and Schooling: Evaluation, Assessment and Accountability in Times of Crises-Reacting Quickly to Explore Key Issues for Policy, Practice and Research with the School Barometer. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 32, 1–34. doi:10.1007/s11092-020-09322-y

König, J., Jäger-Biela, D. J., and Glutsch, N. (2020). Adapting to Online Teaching during COVID-19 School Closure: Teacher Education and Teacher Competence Effects Among Early Career Teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Edu. 43 (4), 608–622. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650

Lenhard, W., and Schneider, W. (2006). EFLE 1–6. Ein Leseverständnistest für Erst- bis Sechstklässler (A reading comprehension test for first to sixth graders). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Minkos, M. L., and Gelbar, N. W. (2020). Considerations for Educators in Supporting Student Learning in the Midst of COVID‐19. Psychol. Schools 58 (2), 416–426. doi:10.1002/pits.22454

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Kennedy, A. M., and Foy, P. (2007). PIRLS 2006 International Report. Boston: TIMMS & PIRLS International Study Center.

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., and Hooper, M. (2017). PIRLS 2016 International Results in Reading. Boston: TIMMS & PIRLS International Study Center.

Niemiec, C. P., and Ryan, R. M. (2009). Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in the Classroom. Theor. Res. Edu. 7 (2), 133–144. doi:10.1177/1477878509104318

Rupley, W. H., Blair, T. R., and Nichols, W. D. (2009). Effective reading Instruction for Struggling Readers: The Role of Direct/explicit Teaching. Reading Writing Q. 25 (2-3), 125–138. doi:10.1080/10573560802683523

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: Definitions, Theory, Practices, and Future Directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61, 101860. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101860

Stanat, P., and Cristensen, G. S. (2006). Where Immigrant Students Succeed: A Comparative Review of Performances and Engagement in PISA 2003. Paris: OECD.

Statistik Austria (2021). Bildung in Zahlen 2019/20 (Education in Numbers 2019/20). Vienna: Statistik Austria.

Taylor, B. M., Pearson, P. D., Clark, K., and Walpole, S. (2000). Effective Schools and Accomplished Teachers: Lessons about Primary-Grade reading Instruction in Low-Income Schools. Elem. Sch. J. 101 (2), 121–165. doi:10.1086/499662

Thomas, A. E. (2015). Messbarkeit von Lesemotivation bei Leseanfänger/innen (Measurability of reading motivation in beginning readers). Kongress der Österreichischen Gesellschaft für Forschung und Entwicklung im Bildungswesen (ÖFEB). Klagenfurt: Alpen-Adria-Universität Klagenfurt.

Thomas, A. E., and Müller, F. H. (2016). Entwicklung und Validierung der Skalen zur motivationalen Regulation beim Lernen (Development and Validation of Scales Measuring Motivational Regulation for Learning). Diagnostica 62, 74–84. doi:10.1026/0012-1924/a000137

Thomas, A. E., Herndler-Leitner, K., and Frank, E. (in press). Die sprachliche Förderung von Schülerinnen und Schülern mit einer anderen Erstsprache als Deutsch (aEaD) in Deutschförderklassen: eine erste Evaluation (Language support for students with insufficient knowledge in German in language remedial classes: a first evaluation). heilpäd.

Tomasik, M. J., Helbling, L. A., and Moser, U. (2021). Educational Gains of In-Person vs. Distance Learning in Primary and Secondary Schools: A Natural experiment during the COVID-19 Pandemic School Closures in Switzerland. Int. J. Psychol. 56 (4), 566–576. doi:10.1002/ijop.12728

Wyse, A. E., Stickney, E. M., Butz, D., Beckler, A., and Close, C. N. (2020). The Potential Impact of COVID‐19 on Student Learning and How Schools Can Respond. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 39 (3), 60–64. doi:10.1111/emip.12357

Keywords: reading comprehension, self-determination theory (SDT), COVID-19, elementary school, achievement

Citation: Thomas AE (2021) First and Second Graders’ Reading Motivation and Reading Comprehension Were Not Adversely Affected by Distance Learning During COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:780613. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.780613

Received: 21 September 2021; Accepted: 09 November 2021;

Published: 01 December 2021.

Edited by:

Isabel Morales Muñoz, University of Birmingham, United KingdomReviewed by:

Fitri Nur Mahmudah, Ahmad Dahlan University, IndonesiaBiljana Stangeland, Alv B AS, Norway

Copyright © 2021 Thomas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Almut E. Thomas, YWxtdXQudGhvbWFzQHBoLWthZXJudGVuLmFjLmF0

Almut E. Thomas

Almut E. Thomas