95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Educ. , 08 December 2021

Sec. STEM Education

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.780401

This article is part of the Research Topic Professional and Scientific Societies Impacting Diversity, Equity and Inclusion in STEMM View all 17 articles

Miriam Segura-Totten1†

Miriam Segura-Totten1† Bryan Dewsbury2†

Bryan Dewsbury2† Stanley M. Lo3

Stanley M. Lo3 Elizabeth Gibbons Bailey4

Elizabeth Gibbons Bailey4 Laura Beaster-Jones5

Laura Beaster-Jones5 Robert J. Bills6

Robert J. Bills6 Sara E. Brownell7

Sara E. Brownell7 Natalia Caporale8

Natalia Caporale8 Ryan Dunk9

Ryan Dunk9 Sarah L. Eddy10

Sarah L. Eddy10 Marcos E. García-Ojeda5

Marcos E. García-Ojeda5 Stephanie M. Gardner11

Stephanie M. Gardner11 Linda E. Green12

Linda E. Green12 Laurel Hartley13

Laurel Hartley13 Colin Harrison14

Colin Harrison14 Mays Imad15

Mays Imad15 Alexis M. Janosik16

Alexis M. Janosik16 Sophia Jeong17

Sophia Jeong17 Tanya Josek18

Tanya Josek18 Pavan Kadandale19

Pavan Kadandale19 Jenny Knight20

Jenny Knight20 Melissa E. Ko21

Melissa E. Ko21 Sayali Kukday22

Sayali Kukday22 Paula Lemons23

Paula Lemons23 Megan Litster24

Megan Litster24 Barbara Lom25

Barbara Lom25 Patrice Ludwig26

Patrice Ludwig26 Kelly K. McDonald27

Kelly K. McDonald27 Anne C. S. McIntosh28

Anne C. S. McIntosh28 Sunshine Menezes29

Sunshine Menezes29 Erika M. Nadile7

Erika M. Nadile7 Shannon L. Newman30

Shannon L. Newman30 Stacy D. Ochoa31

Stacy D. Ochoa31 Oyenike Olabisi32

Oyenike Olabisi32 Melinda T. Owens33

Melinda T. Owens33 Rebecca M. Price34

Rebecca M. Price34 Joshua W. Reid35

Joshua W. Reid35 Nancy Ruggeri36

Nancy Ruggeri36 Christelle Sabatier37

Christelle Sabatier37 Jaime L. Sabel20

Jaime L. Sabel20 Brian K. Sato38

Brian K. Sato38 Beverly L. Smith-Keiling39

Beverly L. Smith-Keiling39 Sumitra D. Tatapudy40

Sumitra D. Tatapudy40 Elli J. Theobald41

Elli J. Theobald41 Brie Tripp42

Brie Tripp42 Madhura Pradhan43

Madhura Pradhan43 Madhvi J. Venkatesh44

Madhvi J. Venkatesh44 Mike Wilton45

Mike Wilton45 Abdi M. Warfa46

Abdi M. Warfa46 Brittney N. Wyatt47

Brittney N. Wyatt47 Samiksha A. Raut48*

Samiksha A. Raut48*The tragic murder of Mr. George Floyd brought to the head long-standing issues of racial justice and equity in the United States and beyond. This prompted many institutions of higher education, including professional organizations and societies, to engage in long-overdue conversations about the role of scientific institutions in perpetuating racism. Similar to many professional societies and organizations, the Society for the Advancement of Biology Education Research (SABER), a leading international professional organization for discipline-based biology education researchers, has long struggled with a lack of representation of People of Color (POC) at all levels within the organization. The events surrounding Mr. Floyd’s death prompted the members of SABER to engage in conversations to promote self-reflection and discussion on how the society could become more antiracist and inclusive. These, in turn, resulted in several initiatives that led to concrete actions to support POC, increase their representation, and amplify their voices within SABER. These initiatives included: a self-study of SABER to determine challenges and identify ways to address them, a year-long seminar series focused on issues of social justice and inclusion, a special interest group to provide networking opportunities for POC and to center their voices, and an increase in the diversity of keynote speakers and seminar topics at SABER conferences. In this article, we chronicle the journey of SABER in its efforts to become more inclusive and antiracist. We are interested in increasing POC representation within our community and seek to bring our resources and scholarship to reimagine professional societies as catalyst agents towards an equitable antiracist experience. Specifically, we describe the 12 concrete actions that SABER enacted over a period of a year and the results from these actions so far. In addition, we discuss remaining challenges and future steps to continue to build a more welcoming, inclusive, and equitable space for all biology education researchers, especially our POC members. Ultimately, we hope that the steps undertaken by SABER will enable many more professional societies to embark on their reflection journeys to further broaden scientific communities.

On May 25th, 2020, Mr. George Floyd was murdered by a police officer in Minneapolis (Bryson Taylor, 2020). This was not the first high-profile murder of a Black man by police in Minnesota-in 2016, Mr. Philando Castile was killed near Minneapolis (Smith, 2017). However, building on a history of racial injustices nationwide and the Black Lives Matter movement, the death of Mr. George Floyd in 2020 catalyzed national action in all parts of society, including the sphere of higher education. The location of these incidents was particularly relevant to the Society for the Advancement of Biology Education Research (SABER), an international organization of discipline-based biology education researchers, because its annual meetings had been held in Minneapolis since its inception in 2011. The historical and continuing racial violence in Minneapolis (Nathanson, 2010) sparked a conversation about whether SABER should continue to hold its meetings in this city. This in turn led to a much broader discussion related to systemic racism and the perception by some of SABER’s members of a lack of existing support and inclusion towards members of color. This event paved the way for SABER’s journey of acknowledging and reflecting on systemic racism.

In this essay, we describe SABER’s actions in direct response to Mr. George Floyd’s death, discuss the impact of these actions, and articulate SABER’s long-term goals for addressing systemic racism both within the society and broader academic structures. The goal of documenting this process is to show how a professional society could be mobilized in response to an event that heightened long-standing issues of racial justice and equity, and how the resulting journey led to tangible evidence of positive change in a year. We hope that the reflections in this essay will serve as a general guide to other professional societies that are grappling with how to address issues related to racism, diversity, equity, and social justice.

We are writing this essay on behalf of SABER, but it brings up an important question as far as who constitutes SABER and who can speak on behalf of an organization of hundreds of people, all of whom have a different history and set of experiences and perceptions of the organization. We acknowledge this challenge and hope that our shared contribution can help describe the collective efforts of the society, but we know that voices are missing. We tried to identify people who contributed in specific ways to these 12 actions and invited them as authors. Our team cannot speak about the experiences or perceptions of all SABER members, but the authors identify as white, Latinx, Black, Southeast Asian, East Asian, South Asian, multiracial, Immigrant American, women, men, non-binary, genderqueer, LGBTQ+, first-generation college graduate, continuing generation college graduate, non-traditional student, parent, caregiver, chronically ill, living with a disability, religious, non-religious, and associated with the military (Smith-Keiling et al., 2020). We represent graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, university staff, tenure-track faculty, tenured faculty, and non-tenure-track faculty including lecturers. Some of us have held leadership positions at the highest levels of SABER, including the Steering and Executive committees, others have served as committee chairs, committee participants, abstract reviewers, event facilitators, or as general attendees of the conference.

More than a decade ago, the need emerged for a new professional society focused on biology education research. More biologists and biology educators were engaging in discipline-based education research, yet there was not a single meeting where everyone could attend to present their work. Discipline-based education researchers in fields like physics, chemistry, and geoscience in the United States could attend one or two professional society meetings. However, the sub-disciplinary nature of biology - with over 64 different professional societies (e.g., American Society for Plant Biologists, American Society for Microbiology, American Society for Cell Biology) - made it impossible for all biology educators to attend a single cohesive biology meeting. Many of these sub-disciplinary biology societies had some sessions focused on education research, although there were often very few organized talks and posters, making it difficult to justify the expense of attending the entire meeting.

In response to this need, SABER was founded in 2010. In the first year, a group of 29 invited biologists and biology education researchers convened at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis to lay the groundwork for the society (Offerdahl et al., 2011). The new SABER society exclusively focused on biology education research, and its unofficial slogan of “Show me the data” emphasized the need for systematically collecting evidence to make instructional decisions within biology courses. Given the social contexts of the issues that some SABER members attempt to address, “data” here are inclusive of that derived from both qualitative and quantitative approaches to experimental design (Lo et al., 2019). We also note that our students are more than just sources of data and consider the impact of our research on their lives and education.

The first annual meeting of SABER was held in 2011 at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Every in-person meeting thereafter was held at this same location because it was logistically convenient and also kept the meeting costs affordable. Specifically, free access to meeting rooms at the university and the low cost of food kept the registration costs relatively economical in comparison to other education or scientific meetings. The availability of a major international airport, convenient mass transportation, student dorms and hotels within walking distance of the meeting, and the central location of Minneapolis with respect to the east and west coasts of the US made travel costs less expensive. Lower costs for attendees reduced the financial barrier posed by a typical meeting attendance and thus made attending SABER relatively financially inclusive.

The first seven meetings were primarily organized by one of the founders of SABER. In 2017, the inaugural steering committee, which was composed of eight people, was formed to create bylaws, organizational structure, and hold the first elections. This steering committee made diversity and inclusion key components of the bylaws and goals of the organization, and visibly posted both the society’s goals and a diversity statement on the organization website. Reflective of these priorities, the Diversity and Inclusion Committee (Table 1) was the second SABER-wide committee to be formed in 2018, after the Abstract Review Committee. The first president, president-elect, secretary, and treasurer were elected in 2019. Although SABER has held 11 annual meetings that have attracted thousands of people, it is still a young society with no paid staff, composed exclusively of volunteer leaders and committee members, and with a formal structure that has only been in place for two years.

Most scientific professional societies have a history of racial exclusion and continue to grapple with issues of inclusion and diversity within the membership (Cech and Waidzunas, 2019; ASM Diversity, 2020; Lee et al., 2020; Segarra et al., 2020b; Ali et al., 2021; Carter et al., 2021); the ubiquity of this problem illustrates its systemic nature. Steps to address racial inequity are specifically important for professional societies because these societies ought to provide a platform for individuals from minoritized backgrounds to share their research and build a network for their continued professional success (Morris and Washington, 2017; Segarra et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2020; Segarra et al., 2020b; Harris et al., 2021; Madzima and MacIntosh, 2021). SABER, like other professional societies, has struggled with a lack of representation of People of Color (POC), including in leadership positions. The 29 scholars who were invited to the initial meeting of the organization were all white-presenting1. The founders of SABER, seven out of eight of the steering committee members, and the majority of committee chairs have been white-presenting, including the two inaugural co-chairs of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee. All of the elected officers in the first round of elections were white. Further, even though no demographic data were collected on race or ethnicity before 2020, an overwhelming majority of attendees at the annual conference have been perceived as white. It is important to point out that the reasons for these observations are complex and potentially the result of the intrinsic racial composition of the SABER membership that mirrors the national trend of faculty in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields (Miriti, 2020; National Science Foundation, 2021). In this article, we define POC as individuals who identify as members of racial and ethnic groups that have been traditionally marginalized. This denomination includes, but is not limited to, individuals who identify as Asian, Black, Latinx, and Indigenous. We focus on marginalization rather than underrepresentation because certain racial and ethnic groups, while not underrepresented in STEM, still experience marginalization (Siy and Cheryan, 2013; Yip et al., 2021).

Indeed, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in the membership and leadership of SABER reflects a wider issue within STEM, both in the workplace and in academia. The lower representation of certain groups in STEM extends from the college level through the attainment and retention of academic faculty positions (Allen-Ramdial and Campbell, 2014; Hassouneh et al., 2014; National Science Foundation, 2021; Pew Research Center, 2021). Moreover, diversity in the workforce and in academia is not reflective of the ethnic and racial composition of the US (Allen-Ramdial and Campbell, 2014; Li and Koedel, 2017; Morris and Washington, 2017; Martinez-Acosta and Favero, 2018; Miriti, 2020; National Science Foundation, 2021). Factors that influence the observed underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities in STEM are varied, and include the lack of access to research experiences at the college level, paucity of mentorship at different career stages, and the creation and perpetuation of institutional environments around race that range from apathetic to repressive (Mahoney et al., 2008; Villarejo et al., 2008; Peralta, 2015; Valantine and Collins, 2015; Whittaker et al., 2015; Zambrana et al., 2015; McMurtrie, 2016; Swartz et al., 2019; Folkenflik, 2021; Gosztyla et al., 2021). Interestingly, a climate survey of the membership of the American Physiological Society (APS) revealed unwelcoming environments across different sectors, including private corporations and academia, highlighting that issues with inclusion are pervasive in society (ASM Diversity, 2020). Even though there are many initiatives aimed at increasing diversity, these often fall short when implemented in academic STEM spaces that are not supportive and inclusive (Puritty et al., 2017).

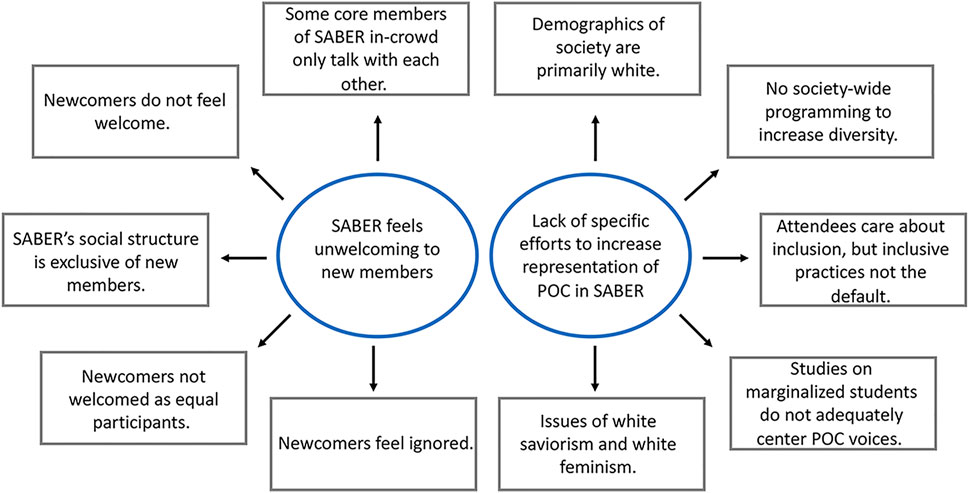

Responses from a SABER post-conference survey in 2019 indicated that many members of SABER saw a lack of racial representation in conference attendance and leadership as a problem, and that first-time SABER attendees did not feel included at SABER (Figure 1). For example, some survey respondents felt as though SABER was an exclusive clique, and if they were not part of the in-group, then they were dismissed and ignored. Further, survey responses commented that there was seemingly a lack of awareness in the research being presented at SABER of critical frameworks and issues facing Black students and colleagues. For example, it was noted that the majority of the biology education research on Students of Color focused on achievement gaps, using deficit framing of comparing white students to Students of Color, and did not focus on racism (Ladson-Billings, 2006), institutional barriers to minoritized students, or critical race theory (Ladson-Billings, 1998) as a way to understand the experiences of these students. In addition, survey responses reflected that many members supported measures to increase representation in SABER, such as establishing travel funds specifically for conference attendees who identify as POC.

FIGURE 1. Themes derived from SABER attendee survey responses from 2019 in response to the question: “In what ways has SABER not fully practiced diversity, equity, and inclusion?” Themes are shown in blue circles and sample comments from these themes are shown in squares.

In response to the survey results, members of the Executive and Diversity and Inclusion committees (Table 1) decided to: 1) track the demographics of registrants for the annual meetings starting in 2020 to better characterize the racial composition of SABER, 2) compare the demographics of abstract submitters and accepted abstract presenters to identify any inequities in abstract acceptance that should be addressed, and 3) establish and support the Mentoring Committee, to address issues of inclusion for newcomers (Table 1). Further, the Diversity and Inclusion Committee generated a list of ideas to address additional issues from the survey responses, but none of the ideas were transformed into tangible actions during the 2019–2020 academic year. Thus, although the leadership of SABER had taken initial steps to address issues of inclusion and diversity, the majority of the actions described in this article resulted from conversations and discussions in the summer of 2020.

To begin addressing issues of lack of support and inclusion, the “SABER Buddies” program was instituted to build community among new SABER attendees. The Diversity and Inclusion Committee suggested the name and the Mentoring Committee implemented the structure of the program. This initiative paired multiple new or returning attendees with mentors who had previously attended SABER, forming groups of four to seven people. Small group mentoring was used in an effort to provide new attendees with multiple contacts and ease potential social and logistical pressures. Mentors were asked to meet with attendees and help introduce the conference to them; attendees were encouraged to ask mentors questions and some of these conversations even led to new collaborations. The SABER Buddies program was so well-received that it was implemented again in 2021 and is being extended into a yearlong mentoring program. In addition to the Buddies, virtual game nights were hosted in SABER 2020 and 2021, and in SABER West in 2021. These virtual game nights were designed to help graduate students and postdoctoral fellows to meet and interact.

As protests began nationwide in response to Mr. George Floyd’s murder (Bryson Taylor, 2020), SABER, like many other scientific professional societies, was silent on the issue until a Black member emailed the SABER listserv. The call for justice in support of those who have experienced racially-motivated trauma created a sense of urgency and propelled a flurry of emails about whether the conference should continue to be held in Minneapolis given the local history of systemic racism there. This tragic event and the resulting email exchanges on the SABER listserv served as a catalyst for SABER to self-reflect on its previous inaction on systemic racism, to recognize that systemic racism pervades nationally but manifests in different ways, and to determine what changes needed to be made to the organization to make it more inclusive.

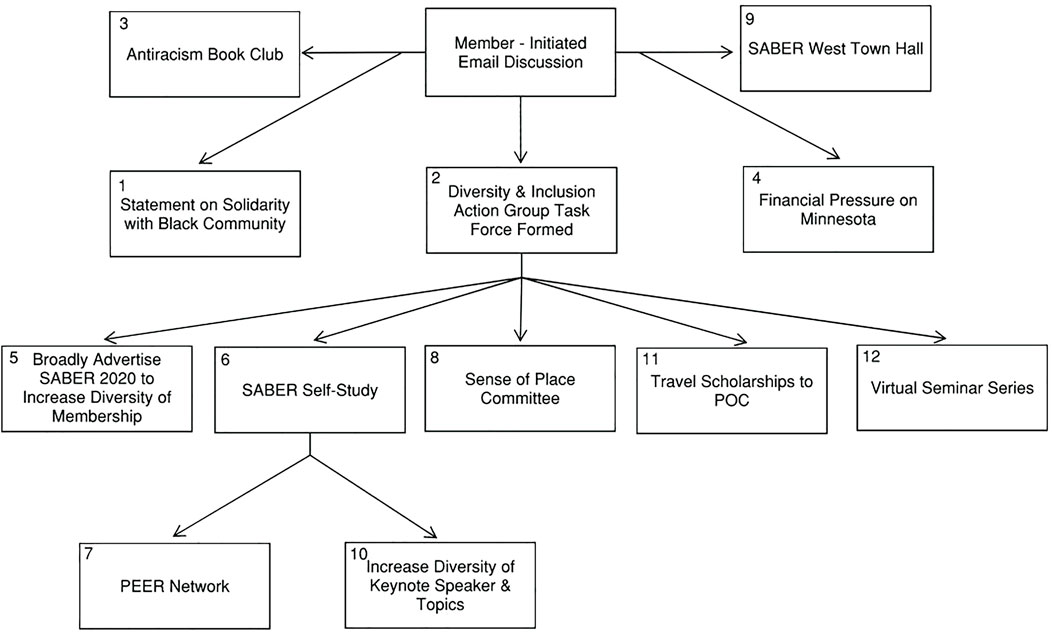

Within three weeks of Mr. George Floyd’s murder, SABER’s Executive and Diversity and Inclusion committees worked together to: 1) create a public statement of solidarity with the Black community, 2) send a letter to entities in Minnesota to financially pressure them to end police brutality, and 3) initiate a task force open to anyone in the SABER community called Diversity and Inclusion Action Group on Place and Racial Justice (Table 1; Figure 2, actions 1, 2 and 4). These initial actions, coupled with the email discussions resulting from Mr. George Floyd’s murder, ultimately led to additional actions (Figure 2, actions 5–12). Importantly, while some of the discussions and activities related to these actions included all members of the society, some of the activities were first steps towards involving and amplifying the voices of POC members of SABER. For example, many of the actions that derived from conversations within the Diversity and Inclusion Action Group (Figure 2, actions 5–8 and 10) were shaped by the perspectives and suggestions of POC SABER members on how to best address issues of equity and inclusion. The creation of an online environment for difficult dialogues on how to tackle issues of inclusion in SABER was important for the creation of initiatives that responded to POC members’ needs. These 12 actions are described in detail below, including what has resulted from the action.

FIGURE 2. Actions taken by SABER to increase inclusion. Actions are numbered according to the order in which they appear in the text. The arrows indicate which actions led to other initiatives.

Given that members often look up to professional societies to model what is appropriate and accepted in the field, the silence of an organization can inadvertently indicate approval or neutrality about an issue or event, even if that event runs counter to the goals of the organization (Settles et al., 2020). As such, it can be useful for professional societies to make formal statements about events or issues, particularly when they affect marginalized groups within the organization, so that the organization does not appear to ignore the situation.

The SABER Executive Committee felt a response was needed to the events surrounding Mr. George Floyd’s murder. However, they were aware of their positionality as white individuals and for that reason relied on the Diversity and Inclusion Committee, which included POC, to take the lead in drafting a statement indicating SABER’s explicit solidarity with the Black community. This statement highlighted SABER’s support for the Black community, particularly students and colleagues in biology, and an acknowledgement of the society’s current lack of awareness and action regarding racial injustices, even though a stated goal of the society was to strive for an inclusive community (Table 2). The statement, which was reviewed and edited by the member who first emailed the listserv, the SABER Diversity and Inclusion Committee, and the SABER Executive Committee, was then posted on the society website and sent to everyone on the society listserv.

Even though the statement promised specific commitment to raising awareness of issues of racism and taking antiracist actions, it was in many ways written from the point of view of a white majority organization with white majority perspectives. As such, the statement intentionally recommended resources focused on what white people could do for racial justice and how to unpack white privilege. While unintentional, the language of the statement subtly positioned the organization as distinct from the Black community (thereby erasing the presence of SABER members who identify as Black), by standing in solidarity with the Black community and committing for white individuals to learn about the struggles of students and colleagues from minoritized backgrounds. In addition to providing educational resources to the membership on issues of diversity and racism, it is important for SABER to center minority voices in ways that consider them as rightfully present with legitimized membership in the organization (Calabrese Barton and Tan, 2020). Because of the perceived timely need of producing a statement and the concern about silence being interpreted as lack of compassion, there was not enough time to solicit extensive feedback from a diversity of perspectives on the statement, which may have identified some of these problems beforehand. Nonetheless, this statement represents an important first step for the society to acknowledge its history and reckon with potential future actions. We share the imperfect nature of the SABER statement of solidarity not as an indictment of those who worked to show their support of minoritized individuals, but as a way to alert readers who care about issues of racism and social justice to the importance of including a variety of individuals with different perspectives when crafting a document meant to represent the stance of the entire membership of a society.

Notably, many other scientific societies, institutions of higher education, and private corporations also responded to the events surrounding the death of Mr. George Floyd by posting statements of solidarity with the Black community (Staff A. P., 2020; August et al., 2020; Bertuzzi and Patel, 2020; Staff E., 2020; Samuelson et al., 2020; Schloss et al., 2020). Some of these statements had similar issues as SABER’s statement and others were critiqued for committing to efforts that were largely symbolic and short-term (Belay, 2020; Bumb, 2020; Weiser, 2020). However, the SABER membership saw their statement of solidarity not as the end of their pledge to address systemic racism and racial injustices, but as the first step. The remainder of this manuscript describes 11 additional steps that were taken to transform this pledge into actions to pave the way towards concrete changes in the society’s practices, policies, and composition.

Professional societies can bring hundreds to thousands of people into a city, creating revenue for transportation, lodging, and restaurants. This financial influence can be used as an agent of change, as when organizations boycotted North Carolina when it enacted anti-transgender policies (Jenkins and Trotta, 2017). SABER held its annual meeting in Minneapolis for eight consecutive years, bringing thousands of visitors into Minneapolis. In an effort to exert a political impact by using its financial influence, SABER sent letters to the governor of Minnesota, the mayor of Minneapolis, the CEO and manager of the hotel where conference participants typically stay, the director of operations for the catering company that has supplied food for the conference dinners, the deli that had supplied lunches, and the chief of the Minneapolis police. The letter stated that SABER would stop meeting there if it did not see evidence of justice and changes in Minnesota law enforcement. An excerpt demands that:

“We need to see tangible evidence of action for justice for Mr. Floyd and of changes in Minnesota law enforcement. Such changes would include de-escalation training for police, firing of police who violate human rights, and implicit bias training for all government officials, police, and other public servants. These actions will allow its citizens of color to feel protected, not threatened, by police. We need to see the requests, needs and perspectives of your Black communities in Minneapolis and Minnesota honored.”

The letters had three concrete demands: justice, to the extent it could be achieved, for Mr. George Floyd, changes in Minnesota law enforcement, and honoring the requests, needs, and perspectives of Black communities in Minnesota. We have included the complete letter that was sent to the governor in the Supplementary Materials.

SABER did not hear back from anyone who received the letters, so it is impossible to discern the letter’s impact. That said, the society was part of a broader social movement to demand change in the Minneapolis Police Department. The society followed what happened concerning justice and reform in Minneapolis over the next year to see whether our demands were met. While justice for Mr. George Floyd can never be fully served, all four of the police officers involved in his death were fired and charged with either second-degree murder or aiding and abetting second-degree murder. Notably, police officer Derek Chauvin was found guilty of second-degree unintentional murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter and sentenced to 22.5 years in prison. In terms of changes in Minnesota law enforcement, while initial protests in Minneapolis were often met with a seemingly violent police presence, the city of Minneapolis did invoke plans for police reform (Office of Police Conduct Review, 2021), which included new disciplinary processes and body worn camera policy changes, as well as requiring officers to use the lowest level of force to safely engage a suspect. However, there is concern about whether this reform is sufficient or meaningful. Much work still needs to be done in terms of honoring the requests, needs, and perspectives of Black communities in Minnesota and across the US. Black people continue to die at the hands of the Minneapolis police force (Hargarten et al., 2021), what reforms to enact remain contentious both overall and within the Black community (Janzer, 2021), and everything is occurring within a national framework that greatly limits police accountability (Carlisle, 2021).

Professional societies can serve as sources of information for its members. The initial statement from SABER (action 1) indicated that SABER committed to becoming more knowledgeable about how biases contribute to racial injustices. The email conversations on whether the SABER conference should continue to meet in Minneapolis spurred two SABER members to organize and facilitate a virtual book club to discuss Dr. Ibram X. Kendi’s book How to Be an Antiracist (Kendi, 2019) and how to consider its principles in our STEM teaching and research. The initial call resulted in 49% of the SABER membership (286 individuals) expressing interest in joining a virtual learning community. Twenty nine facilitators led different sections with a total of 191 participants. The two organizers met with facilitators across three separate meetings prior to the start of the book club to talk about the format and share sample discussion questions and facilitation tips (see Supplementary Materials). Each discussion group met three to five times during the summer of 2020. The organizers convened at the end of the summer with 13 of the 29 facilitators (others could not meet due to scheduling conflicts) and debriefed ways to improve this process and gauge interest in future book club discussions. Some groups continued to meet and discuss other books and media focused on racism (e.g., Race after Technology, Benjamin, 2019). Given the predominantly white membership of SABER, it is important to acknowledge the tendency for white communities to join book clubs when Black trauma occurs in lieu of taking actionable steps to address racism from a position of privilege (Johnson, 2020). For this reason, during discussions facilitators specifically asked participants to identify antiracist action-oriented goals they could implement at the individual to institutional levels. Actions articulated included: identifying specific changes to course content, facilitating workshops on inclusive teaching practices, attending conferences such as NCORE (National Conference on Race and Ethnicity), creating departmental antiracism working groups, advocating for more equitable admissions and hiring practices, applying for funding to support antiracist initiatives, and writing letters to administrators about creating more inclusive institutional environments. Due to the way it was organized, the book club helped increase awareness and focus conversations toward actionable change in the SABER community.

To immediately respond to the issues of race and social justice that arose during the email conversations resulting from the murder of Mr. George Floyd, the Diversity and Inclusion Committee created the Diversity and Inclusion Action Group on Place and Racial Justice task force (Table 1) to focus on two goals. The first was to identify issues of “place” that create a sense of safety, or lack thereof, to members of SABER who identify as POC in consideration for future conference locations. The second was to assess actions that SABER and its members could take to promote awareness of and action surrounding racial justice.

This task force convened to develop concrete recommendations that would be conveyed at the SABER 2020 meeting that was happening within a month. A group of 25 people participated in a series of meetings and online discussions to try to address current challenges for POC in SABER. The group collectively brainstormed steps that could be enacted in the short-term (over the following weeks) and long-term (within the year) to begin addressing these issues. They generated seven ideas (Figure 2, actions 5–8 and 10–12) that the SABER community enacted and which are described below. The action group dissolved after the summer 2020 meeting because the intent was for it to be a temporary task force that would lead to more permanent SABER infrastructure to carry out the long-term actions.

With conferences forced to go online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the annual SABER meeting was not held in Minneapolis and instead was delivered as a free virtual conference held every Friday in July 2020. Cost is a motivating factor for individuals who attend research conferences (Sarabipour et al., 2021). For this reason, the SABER leadership and the action group saw the virtual conference as a unique opportunity to promote inclusion by alleviating financial pressure. The free nature of the virtual conference might attract people who had never attended the SABER meeting, including participants from institutions that are not research-intensive (Sarabipour et al., 2021). Attracting new attendees from diverse types of institutions might in turn result in an increase in the representation of POC at the conference particularly because research-intensive institutions, which were currently overrepresented in the membership of SABER, tend to have less diversity in their faculty ranks (Vasquez Heilig et al., 2019).

The group identified a number of listservs and emails to contact about the 2020 SABER conference: American Society of Microbiology, Council for Undergraduate Research, National Institute on Scientific Teaching, CUREnet, CC BioINSITES, HHMI Inclusive Excellence Awardees, IRACDA, SACNAS, CCB FEST, SABER West, Sigma Xi, AAAS Community Board, and Research on STEM education (ROSE) Network (See Supplementary Materials for more information about these organizations). While some of these organizations are specifically for POC, others were leveraged by the social networks of people in the action group to try to broaden awareness of the conference. Additionally, SABER used social media to promote the conference, initiating the SABER Twitter and Instagram accounts.

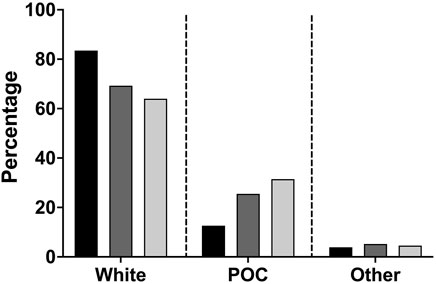

As a result of these actions, the number of people who participated in SABER in 2020 was nearly double the number who participated in 2019. While we did not collect data on the racial and ethnic breakdown of SABER attendees prior to 2020, the percentage of POC who attended SABER in 2020 was 24.3% (307/1264) and in 2021 was 25.9% (174/673). Additionally, the fact that 24% of attendees in 2020 were POC is encouraging given the perception from the 2019 survey responses that POC attendance was much lower. The 2020 and 2021 rates of POC attendance could be explained by at least two alternative hypotheses: 1) the number of POC who attended SABER increased from 2019 to 2021 in part due to some of the actions taken, or 2) the 2019 perception that the percentage of POC in SABER was much lower than 24% did not match actual POC attendance. POC individuals can be “invisible” in professional situations, either because they physically pass for white and may not be perceived as POC, or because they are simply not seen as professionals (Morris and Washington, 2017; Settles et al., 2020). Thus, while it is possible that POC representation in SABER drastically increased from 2019 to 2021, we cannot discount the latter explanation without baseline demographic data. Notably, in 2020, 63.5% (803/1264) of SABER conference registrants were first time attendees and 27.4% of these first time attendees were POC compared to 18.9% of non-first timers (Figure 3). In 2021, 39.2% (264/673) of people were new attendees and 31.4% were POC compared to 22.3% of non-first timers (Figure 3). These numbers suggest that SABER has attracted a more diverse membership in recent years and supports the hypothesis that the number of POC who attended SABER increased from 2019 to 2021. Overall, the racial demographics of SABER are similar to those of other biology professional societies: a 2019 study of the APS membership conducted as part of the STEM Inclusion Study and a climate study conducted by the American Society for Microbiology (Cech and Waidzunas, 2019; ASM Diversity, 2020) indicated that 28% of respondents were Asian, Black or Latinx.

FIGURE 3. Demographic composition of SABER 2020 conference attendees. Black bars represent individuals who had attended five or more SABER conferences as of 2020. Dark grey bars represent individuals who had attended two to four SABER conferences as of 2020. Light grey bars represent first-time SABER attendees.

To better understand how SABER as a professional society could help support POC within SABER, the Diversity and Inclusion Action Group on Place and Racial Justice task force conducted a self-study of the organization and dedicated time during the 2020 annual meeting to help accomplish this objective. We were mindful of the positionality of the facilitator of the self-study during the selection process since we wanted someone who was external to the society and who had relevant personal experience. We therefore invited Dr. Kecia Thomas, a Black scholar who is an expert in the organizational experiences of minority groups and the psychology of workplace diversity, to facilitate this self-study. This self-study included: 1) a pre-conference survey that asked participants to share their thoughts about SABER’s strengths, weaknesses, and barriers for promoting diversity and inclusion, 2) a presentation by the expert facilitator about the importance of diversity in professional organizations, 3) engaging in affinity groups over two weeks to discuss questions related to diversity and inclusion, and 4) having the facilitator convey the results of the self-study to SABER attendees. The pre-survey allowed individuals to anonymously share their thoughts and ideas with the facilitator, and the affinity group leaders summarized the discussions from their groups and shared these with the facilitator. The affinity groups included the following categories: POC, LGBTQ+ individuals, individuals with disabilities, religious individuals, women, community college faculty, primarily undergraduate institution faculty, postdoctoral scholars and graduate students, undergraduates, mentors for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars in biology education research, and an open group for anyone to join. The presentation by the facilitator was intended to broaden awareness about issues of diversity in an organization. It highlighted definitions of diversity and inclusion (Downey et al., 2015), diversity resistance in organizations (e.g., silence regarding inequities, diversity is too time consuming, discrediting ideas of individuals who are in the minority (Thomas, 2008; Segarra et al., 2020b)), implicit biases and reinforcing of negative racial stereotypes (Wheeler et al., 2001), privilege of majority identities, and the “otherness” of being in the minority.

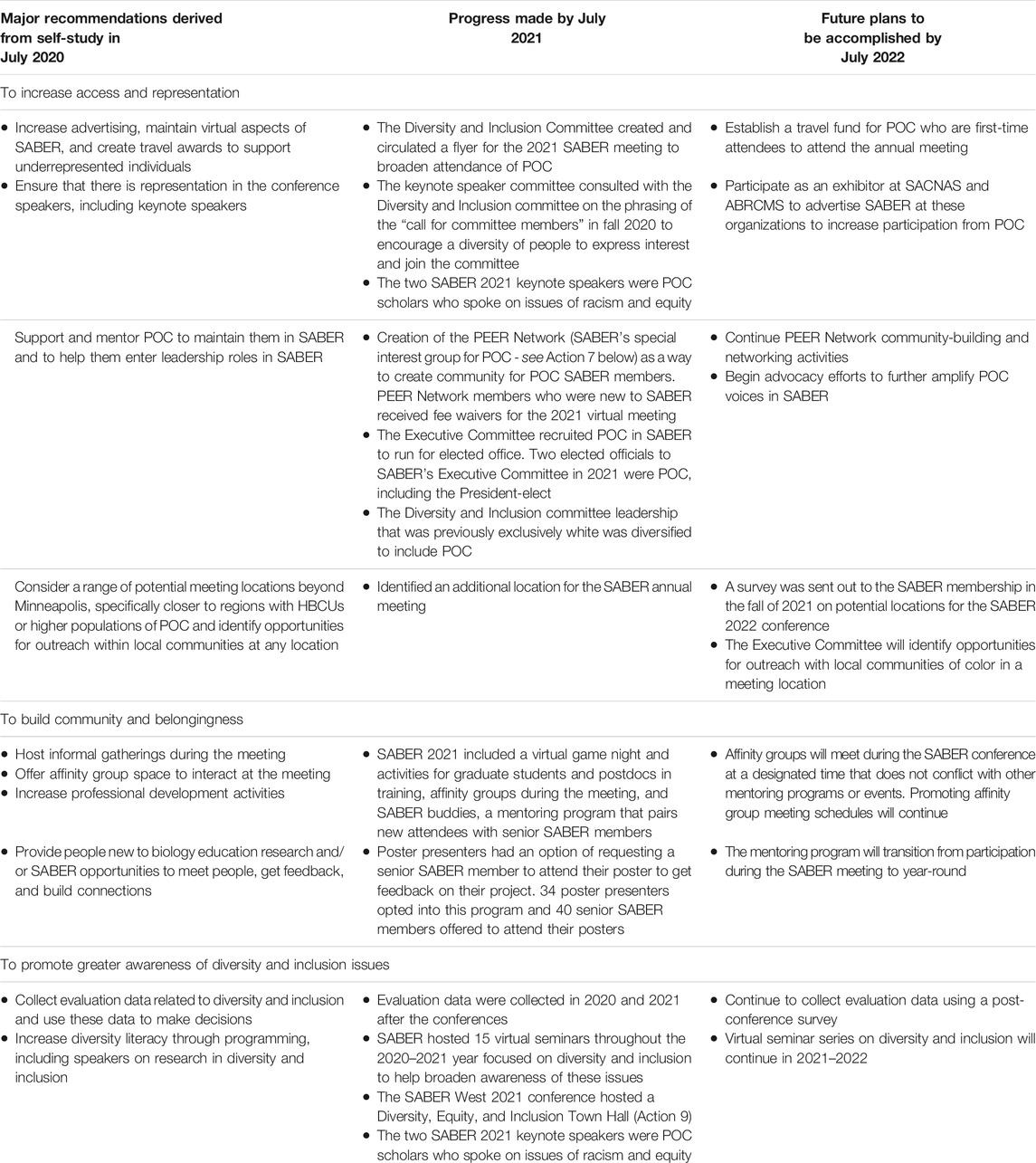

After evaluating the pre-survey responses and the affinity group responses, particularly those from marginalized groups, the facilitator summarized the key findings. The three most prominent findings are listed in Table 3. Many of the recommendations were focused on increasing representation and supporting POC in SABER, building community and belongingness, and promoting greater awareness of diversity and inclusion. Notably, many of the recommendations aligned with ideas that the action group had already identified and was making progress on, but importantly these recommendations were derived from the broader SABER community. In Table 3, we also highlight how the SABER community is addressing these recommendations and what future plans are intended to be accomplished by July 2022. It is important to mention that conversations during the self-study and within the action group acknowledged that even when other locations were being considered as options for future SABER conferences, we had to bear in mind that systemic racism is nationally found. For this reason, the action group recommended focusing on identifying meaningful opportunities for outreach with local communities of color in future meeting locations (Table 3). For a copy of the pre-conference survey questions or the discussion questions in the affinity groups, see Supplementary Materials. For a video of the complete summary of the self-study results, see this link: https://saberbio.wildapricot.org/2020-July-24-Anti-Racism-Summary.

TABLE 3. Major self-study findings from July 2020, including progress to date and future plans to address recommendations.

SABER attendees were surveyed after the 2020 meeting. On average, respondents said that they agreed with the statement, “I found SABER’s 2020 national meeting to be equitable and inclusive.” Some participants noted that SABER had done more specifically on diversity and inclusion within the society and at the conference, and many noted a positive shift from previous years. Many participants mentioned that they appreciated the work done by the racial justice action group, the self-study, the affinity groups, the buddy system for new attendees, and the online free and accessible format. Even though respondents noted that there was room for improvement in terms of the overall lack of diversity in SABER, they appreciated that it seemed like SABER was acknowledging this problem and making concrete actions to rectify it for future meetings.

During conversations within the Diversity and Inclusion Action Group on Place and Racial Justice, the idea emerged that building a community for SABER members who identify as POC would be an important early step in making the professional society more inclusive. This community would also help to address the overarching feeling of exclusion that many SABER members who identify as POC had voiced. Three members of this action group volunteered to lead the creation of the community. Since SABER already had in place special interest groups (SIGs) as a tool for individuals with similar interests and identities to connect (e.g., LGBTQ+ special interest group, Physiology special interest group), it made sense to use this existing framework to build a community for individuals who identify as POC. Initially, the group was termed the Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) SIG. However, the SIG was eventually renamed the PEER Network after conversations between members revealed that the term PEER (Persons Excluded because of their Ethnicity or Race, (Asai, 2020)) better reflected the identity of individuals in the group (Table 1). The first meetings of this SIG coincided with the two self-study affinity group sessions during the July 2020 SABER meeting. More than 20 people met as part of this group during the conference. The general consensus after these meetings was that the SIG should be a community that met throughout the year and had an online space for PEER members to network, collaborate, and grow professionally.

After the July 2020 SABER meeting, the group leads designed and distributed a survey through the SABER email listserv to help shape the direction of the SIG and to collect contact information for individuals interested in joining the group. The results of this survey showed that individuals were most interested in participating in: 1) journal clubs on articles related to inclusiveness, diversity, and antiracist pedagogical practices, 2) mentoring groups, 3) social check-in meetings, and 4) regular meetings to discuss topics of importance to PEERs. Other priorities mentioned in the survey were increasing the visibility of PEERs within SABER, building research collaborations, mental health resources, fundraising, and the creation of a PEER SIG listserv. During this time, we received several emails from individuals asking to join the SIG who do not identify as PEERs but who wanted to be involved in advancing the role of PEERs in SABER. Since, as a group, the members of the network wanted to make it an inclusive space, we decided to leave it open to allies who are not PEERs, and we publicized this in emails to the SABER listserv and during PEER SIG meetings. The PEER Network met as a group twice in the fall of 2020. These initial meetings led to the creation of six subgroups: 1) Happy hour, 2) Journal club, 3) Mentoring (modeled after the SABER-wide “SABER Buddies” program), 4) Safe space (this is the only subgroup that is restricted to individuals who identify as PEERs), 5) Website, and 6) Writing buddies.

Another top priority was to establish an online presence within SABER to enhance the visibility of PEERs, attract new members, and facilitate collaborations. To accomplish this, we solicited and found a volunteer to build a webpage for the PEER Network. The webpage (https://saberbio.wildapricot.org/PEER-Network) contains a description of the goals of the group as well as its mission. In addition, it contains an announcement section, information on the subgroups, a community discussion forum, and contact information for joining the PEER Network and the subgroups. The design and content for the webpage was refined using member feedback.

An early challenge we encountered was how to publicize the existence of the PEER Network within SABER to reach out to members who did not know of its existence. One of the SIG leads advocated to the SABER leadership for society-wide announcements to be made during the 2021 annual meeting, and we designed a slide that members could share at the end of their talks to provide information on the network. We plan to conduct a roundtable discussion on the PEER Network during future SABER meetings to continue to internally publicize the existence of this SIG. An area in which we have not made as much progress as we anticipated is in establishing research collaborations within members of the network. Moving forward, we are considering creating a research mentorship program and establishing research working groups following successful models that are focused on inclusion and equity (Pelaez et al., 2018; Reinholz and Andrews, 2019; Campbell-Montalvo et al., 2020).

Currently, the PEER Network SABER SIG has 105 members out of 582 SABER members (18% of the SABER membership). These numbers provide evidence for the tremendous need for community among SABER POC members. The creation of this group has provided fertile ground for important discussions related to diversity and inclusion within SABER. Our meetings have offered a way for individuals who identify as PEERs to connect and share their experiences. Perhaps most importantly, the creation of this SIG gave PEERs a collective voice within SABER that was previously unavailable. During the summer of 2021, two members of the PEER Network were elected to the offices of President-elect and Secretary of SABER. During our most recent meetings, discussions organically arose about how to further amplify PEER voices by beginning advocacy efforts in SABER.

The impetus for the formation of the Diversity and Inclusion Action Group on Place and Racial Justice task force was the discussion about where to hold the annual conference and whether it should be held in Minneapolis. For this reason, a sub-committee of the task force was the Sense of Place Committee (Table 1), which intentionally included POC, Minneapolis residents, and individuals at different career stages from different types of institutions. The final committee was composed of 16 people and met in three rounds in July 2020 to discuss issues related to the physical location of the SABER conference and Minneapolis specifically. Representatives from the committee shared their advice with the SABER community at the last session of the 2020 SABER conference.

Although the original intent was to discuss how to choose a physical conference location in a way that would honor SABER POC, the conversation broadened with the realization that every major city in the US has racial tensions and systemic racial inequities. The committee did weigh the impacts of registration and travel costs, the logistical challenges of moving to a new location, and previous incidents of racial violence in certain places. However, the discussion expanded to focus on how the SABER community could engage in a more meaningful way with local communities of color, including Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Notably, the committee did not recommend against going back to Minneapolis, as long as progress was made towards racial justice and police reform that reflected the demands stated in the letter we sent to the city (see action 2). There was broad support for keeping a part of the meeting virtual, instituting travel scholarships for POC, and intentionally partnering with local communities of color. This could include speakers addressing local issues of social justice relating to education, being thoughtful about who we are financially supporting (e.g., Black-owned catering companies), and engaging explicitly with local Students of Color through fee waivers and special sessions.

Beginning in 2017, the University of California, Irvine has been home to SABER West, an annual regional conference aimed at providing faculty, staff, and students who seek to improve biology education and conduct education research with an opportunity to engage with the SABER community. While built upon SABER’s focus on biology education research, SABER West has been dedicated to increasing diversity and inclusion by fostering the professional development of biology researchers and educators from community college and other non-research-intensive institutions, a population that is underrepresented at education research conferences. This goal is made explicit by a unique meeting format that includes workshops to promote the development of attendees’ research skills and assist with the implementation of evidence-based teaching practices, as well as multiple sessions to foster collaborative research or pedagogical connections between 2-and 4-year affiliates.

The exacerbation of existing inequities by the pandemic and the national call for higher education to re-evaluate its anti-Black and anti-POC policies after Mr. George Floyd’s death led SABER West organizers to reiterate the need to make diversity, equity, and inclusion in conference spaces a priority. In response, the conference organizers met consistently to reflect on these priorities and to assess whether we, as a field, were critical of our own roles in perpetuating inequality and inequity, especially centered on race and ethnicity.

To start to address the need for actions to increase diversity and inclusion in the SABER West conference, as well as to begin an open dialogue on these issues, the online SABER West 2021 conference convened a panel of diverse individuals for a virtual Town Hall aimed at identifying challenges and practices that result in marginalizing conference spaces. This Town Hall happened in place of a traditional keynote address. Panelists gathered participant insights into the climate of STEM education conferences through a pre-conference survey. This survey asked about participants’ general thoughts on STEM education conferences, motivations and barriers for attendance, and how the conference organization, programming, and structures impact climate (Mair and Thompson, 2009; Mair et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2019).

During the Town Hall, panelists identified and presented the themes that arose from the survey responses: 1) Monetary and physical barriers to conference attendance that can be marginalizing for individuals with families or those who work at institutions with less professional development support, 2) First- or second-hand experience with discriminatory behavior at STEM education conferences, resulting in unwelcoming climates, 3) Physical spaces or programming that has not been designed with individuals with disabilities in mind, and 4) A lack of representation and inclusion of individuals and researchers from 2-year colleges, HBCUs, and Tribal Colleges, resulting in reinforcement of academic hierarchies where participants from 4-year research-intensive institutions often comprise the overwhelming majority of conference attendees. These themes highlight participants’ perceptions of the different barriers to inclusion that can be present in conference spaces.

Panelists viewed their contributions to the Town Hall as giving a voice to and elevating the experiences of those who have been marginalized in these conference spaces. This event was envisioned as a starting point to characterize the current participant experience of STEM education conferences and provide information for SABER West organizers, SABER as a whole, and the broader STEM education research community, to develop ways to create more inclusive conference space.

The majority of invited keynote speakers throughout the history of SABER including the 2020 conference have been white, even when their talks have addressed racial justice. The visibility of invited speakers can send implicit messages about the culture of an organization, and who should be listened to (Tulshyan, 2019; Hagan et al., 2020). The demographic composition of speakers at conferences can also affect the self-efficacy of participants by modeling what a successful researcher looks like and which producers of knowledge are viewed as legitimate (Hagan et al., 2020; Settles et al., 2020). A survey of the SABER community conducted by the Keynote Speaker Committee (Table 1) in 2019 indicated a clear interest in inviting a scholar for the 2020 annual SABER conference to talk about their research around issues of equity, inclusion, and racism, with implications for our own instructional practice. At the SABER 2020 conference, Dr. Elizabeth Canning shared her work on social-psychological interventions to support historically and currently marginalized students. The Keynote Speaker Committee developed a community survey to get an input about SABER community preferences for the 2021 keynote speaker. This committee intentionally conferred with the Diversity and Inclusion Committee on the content and wording of the survey to make the survey as inclusive as possible. Feedback from both the 2020 conference and the community survey for the 2021 SABER conference indicated a sustained interest in learning from scholars in the area of equity, inclusion, and racism and a recommendation to invite a POC as the keynote speaker. This specific action was addressed by the Keynote Speaker Committee; in 2021, the two invited key speakers included a Black woman, Dr. Saundra McGuire, who spoke about her research on metacognitive strategies for increasing STEM student success, with an anti-deficit lens on improving equity in the classroom, and a South Asian man, Dr. Niral Shah, who spoke about his research using poststructuralist frameworks to understand how racism affects the STEM learning experiences of students from minoritized groups.

Given that cost is often a motivating factor for attending a research conference (Segarra et al., 2020b), the action group recommended increasing representation of POC at SABER by offering funding to defray the cost of conference attendance to first-time conference attendees. This was also highlighted in the post-conference survey responses in 2019 and findings from the 2020 SABER self-study. Since SABER 2021 was online again due to COVID-19, the only cost was registration. SABER offered registration fee waivers to individuals in the PEER Network who had not attended SABER previously. Additionally, the ROSE network offered waivers to attendees, with an emphasis on individuals who identified as POC, first-time attendees, community college faculty, and people from primarily undergraduate institutions. While we have not yet implemented a specific travel funding mechanism to increase POC attendance at the SABER national meeting, we have plans to establish a permanent travel award program for POC who are first-time SABER attendees.

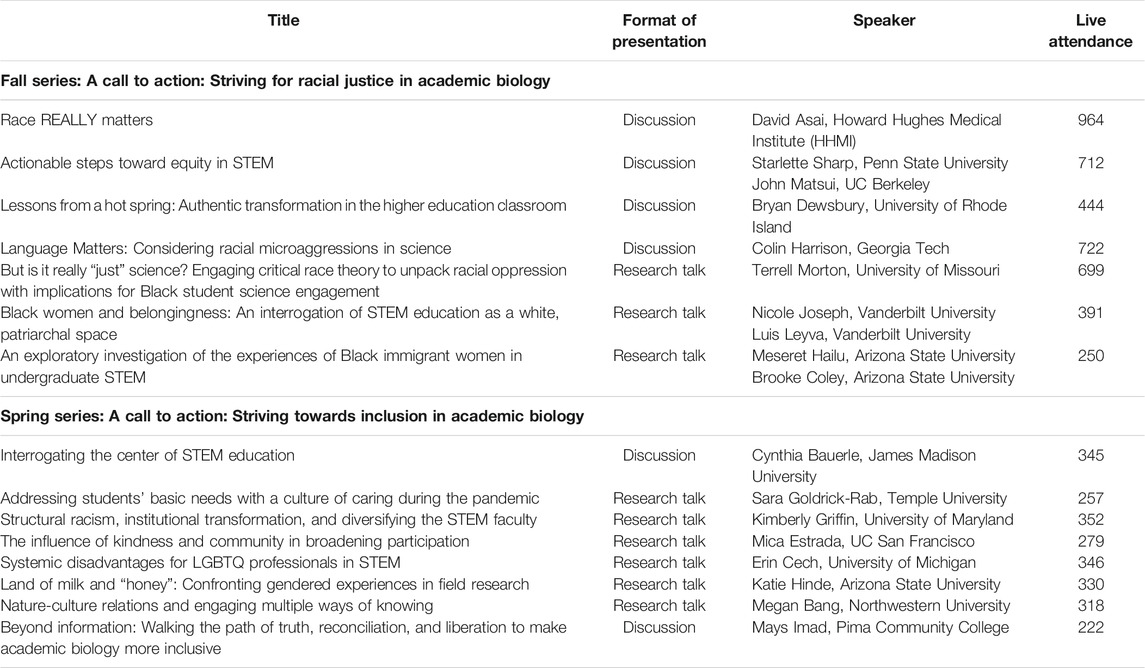

To help promote awareness of issues of systemic racism, SABER hosted a year-long seminar series focused on making academic biology more inclusive, with the fall term speakers specifically focused on racial justice (Table 4). Importantly, the speakers were experts and scholars in issues around diversity, equity, and inclusion; the speakers were intentionally not scholars of color working in other areas of research, thus avoiding the common and taxing assumption that all people of color are experts in research about inclusion (Applewhite, 2021). The intended audience for the seminar series were biologists and biology educators. To broaden the reach of the series, SABER members at 42 different institutions advertised the series to their biology departments. The series was highly attended and attendance ranged from 222 to 964 people. All talks were recorded and posted on the SABER website for later viewing (at https://saberbio.wildapricot.org/Diversity_Inclusion).

TABLE 4. Summary of talk titles, speakers, and live attendance for the SABER virtual inclusion seminar series.

All speakers in the fall 2020 series were POC, and all speakers in the spring 2021 series were women or genderqueer. The focus of the fall seminar series was on building awareness of issues related to racial injustices, particularly experienced by Black individuals, and the spring series broadened the scope to include inequities faced by LGBTQ+ individuals, low-income students, Indigenous students, and women. It was especially important to broaden the types of inequity discussed in the spring 2021 series because the effect of oppression can be amplified in individuals who identify with multiple marginalized identities (Crenshaw, 1991). Some of the seminars were general discussions on topics that academic biologists may not be familiar with but ought to be aware of, including examples of systemic racism, how supposedly neutral language used to describe individuals can be offensive, and how racial microaggressions can create unwelcome and threatening situations in academic settings. The majority of the seminars were research presentations highlighting qualitative and quantitative data that demonstrated inequities in academic environments, and most of the work was done through the lens of critical frameworks. Notably, all of the research presenters were outside the SABER network of biology education researchers: we intentionally brought in new ideas and perspectives by identifying scholars outside of SABER who were working on issues related to diversity and inclusion. Most of the speakers were trained in sociology, psychology, and schools of education (as opposed to discipline-based education research), so they brought a different lens and scholarly focus to this work and to the SABER community.

Several institutions hosted their own local discussion groups to debrief the talks and consider how they could incorporate the ideas at their institution. Some of these have led to the formation of equity and inclusion committees or diversity, equity, and inclusion proposals to higher levels of administration. The series was so well-attended that SABER will continue to hold the series in the 2021–2022 academic year with an additional six talks focused on inclusion.

These actions are just the first steps for SABER to grapple with systemic racism and were not intended, nor expected, to fully make the society antiracist. We acknowledge that organizational change takes time and coordinated effort. Further, we know that it is easy to revert to what is comfortable or familiar, which can make change temporary if it is not accompanied by structural changes to ensure diversity, equity, and inclusion. SABER is not unique in the challenges it faces in terms of equity and inclusion: other biology professional societies, which are older and more established than SABER, also face similar issues. For example, a report published by ASM’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Task Force noted that, while the society has demonstrated a commitment to diversity through initiatives like graduate fellowships to students of color, outreach activities to bring attention to issues of social justice and racism, and providing its staff with antiracism and anti-discrimination training, there remains a lack of diversity in leadership positions, and a significant proportion of ASM POC members feel that they do not have a voice within the society (ASM Diversity, 2020). Black and Latinx members of American Physical Society reported feeling marginalized in the workplace more often than other groups (Cech and Waidzunas, 2019).

Several practices can promote long-term and sustained changes to increase diversity, equity and inclusion: 1) centering voices from individuals who are underrepresented so they can help guide the direction, mission and vision of the organization, 2) supporting efforts to promote diverse representation in leadership positions, 3) mentoring programs to retain underrepresented individuals within the organization, and 4) reaching a critical mass of individuals from diverse backgrounds within the organization (Allen-Ramdial and Campbell, 2014; Morris and Washington, 2017; Piggott and Cariaga-Lo, 2019; Segarra et al., 2020b; Madzima and MacIntosh, 2021). The 12 actions described in this article have initiated the process of long-term change by taking steps towards giving a voice to POC (through the creation of the PEER Network SIG, diversification of keynote speakers at the SABER annual meeting, and the creation of a seminar series focused on inclusion with speakers from marginalized identities), increasing diversity in the leadership of SABER, establishing mentoring programs for new and POC SABER members, expanding the networks through which the SABER conference is advertised, and providing financial support to POC to attend the SABER conference. To continue this process, we hope to enact the following measures: 1) expand current efforts to establish a welcoming environment for POC through mentoring programs and opportunities to network and socialize (Madzima and MacIntosh, 2021), 2) increase fundraising efforts to augment the financial capacity of SABER to provide support to members of groups underrepresented in the society (e.g., conference registration waivers, travel funds), 3) continue and expand current efforts to reach new constituencies of individuals who might benefit from joining SABER, and 4) examine all aspects of the SABER organization and conference through a diversity lens to ensure it is inclusive, equitable, and a welcoming environment for all members (Ali et al., 2021). We are interested in increasing POC representation within the SABER community and bringing our resources and scholarship to reimagine education as an equitable, antiracist experience. To this end, in the future the society might address this goal by initiatives including, but not limited to: 1) the incorporation of special sessions on classic liberatory education frameworks within the annual SABER meeting to learn from other cross-disciplinary scholars engaging in education and equity work (e.g., Gay, 2002; Giroux, 2010; Givens, 2021) and 2) SABER-sponsored programs that work with educators on social justice pedagogy at the postsecondary and secondary level, perhaps following the model for professional development developed by SABER West. The second of these would be crucial in developing a pathway and culture of inclusive discipline-based education research long before these careers are chosen at the graduate level.

We acknowledge that there is not a “one size fits all” approach to the journey of a professional society towards being more inclusive and equitable, and that change should be driven by the specific needs and challenges of a particular group of individuals. For this reason, we envision that SABER as a society should: 1) continue the reflections and conversations that began in earnest during the 2020 self-study, 2) continue to collect demographic data to investigate existing inequities and to make informed decisions about better supporting individuals from minoritized identities who are members of SABER, and 3) keep communication open through forums and surveys that both give a voice to all members and serve to “check in” on the success (or lack thereof) of initiatives geared to increase inclusion and diversity (Cech and Waidzunas, 2019; ASM Diversity, 2020; Segarra et al., 2020b; Madzima and MacIntosh, 2021). As a society, we are making steady progress towards these goals: 1) the Executive Committee is planning to facilitate the attendance of POC faculty and faculty at MSIs, TCUs, and HBCUs at the 2022 SABER conference through awards that include funding for travel and a registration waiver. Beyond attracting a more diverse set of participants to the SABER conference, we are planning inclusive ways to support these individuals by making them an integral part of the conference activities through the PEER Network and the mentoring buddy system; 2) the Diversity and Inclusion Committee and the PEER Network SIG will annually survey the SABER membership and the members of the SIG, respectively, to collect data on existing inequities and the success of current initiatives and to inform future actions; 3) we will continue to collect demographic data society-wide through an annual SABER survey, and 4) the Diversity and Inclusion Committee is reaching out to past POC SABER participants to inquire about reasons they have not returned to SABER conferences, in an effort to identify barriers to participation.

Several climate reports and reflections by STEM professional societies have proposed the following recommendations to increase diversity and inclusion: 1) establishing and fostering open communication with members from minoritized groups, 2) providing greater and continued support and agency to POC individuals to not only retain them within the society, but to build a welcoming environment that these members see as valuable to them, 3) promoting greater diversity in positions of leadership reflective of the racial and ethnic composition of the society, 4) conducting yearly surveys of the membership to track the progress made towards inclusion and diversity, 5) engaging in outreach activities to support diversity on a wider scale, and 6) integrating programming on diversity and inclusion in conferences (Cech and Waidzunas, 2019; Segarra et al., 2020a; ASM Diversity, 2020; Bell, 2020; Segarra et al., 2020b; Womack et al., 2020; Ali et al., 2021; Madzima and MacIntosh, 2021). The findings and recommendations of these climate surveys largely mirror the initial efforts to increase inclusion by SABER as well as those activities planned to sustain the initial work. There is one notable difference: the actions described in this manuscript arose organically through the work of many SABER members, and were not the product of a small group of people. The grassroots movement that began with the horrific death of a man at the hands of a police officer galvanized the membership of SABER and catalyzed change in our group within the span of a year. It is essential for scientific societies to identify ways in which they have neglected their POC members before taking action to rectify issues of inclusion and racism (Ali et al., 2021). Recognizing with humility our shortcomings but utilizing the urgency of this event to propel change, we as a professional society know we are not alone in this endeavor as institutions across the nation and globally have also been seeking more profound steps toward lasting change. We hope that the process of open communication, iterative changes to organizational policy and initiatives, and a data-based approach to examining the success of SABER’s actions will allow the organization to keep equity as not only a core value but also a lived philosophy.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

SR and MS-T conceived of the design of the manuscript. All authors participated in the writing of and editing of the manuscript. SR & MS-T - lead for PEER • BD sent the initial email, gave a talk in the series, co-organized book club on how to be an antiracist • SML is the current President of SABER and contributed to the Sense of Place committee and the SABER West town hall (second author) Alphabetical: • EB - posted solidarity statement, letters, and other D&I content on SABER website • LB-J - active D&I committee member • RB - served as a facilitator for the 2020 SABER book club How to Be an Antiracist • SB - helped lead the action group and the seminar series • NC - led sense of place committee, led initial creation of PEER • RD - participated in sense of place committee, member of mentoring committee 2019–2020, host of SABER game nights 2020 & 2021 • SE - initiated the letters to the governor • MG-O - active D&I committee member • SG - led keynote committee and made sure to incorporate recommendations from action group • LG - D&I committee active member • LH - headed up mentoring committee.

We would like to thank Arizona State University’s HHMI Inclusive Excellence Award, Arizona State University’s Research for Inclusive STEM Education (RISE) Center, University of California Santa Barbara, SEISMIC collaboration, and Community College (CC) BioINSITES for funding the seminar series, as well as all of the speakers, people who introduced the speakers, hosts at institutions who helped to advertise the series, and all of the attendees. Finally, we are grateful for the financial support of SABER and the ROSE network grant (National Science Foundation Research Coordination Networks in Undergraduate Biology Education Grant No. 1826988 to SR) to help support fee waivers and National Science Foundation Grant No. 2109356 to SML and JKK to support some of the seminar speakers and future initiatives.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

These actions would not have been possible without some funding and substantial time and effort by dedicated volunteers. We are grateful to so many people in the SABER community who have spent countless hours -- and continue to do so -- to try to make SABER more inclusive. Special thanks go out to the volunteers of the action group, the volunteer facilitators for the affinity groups, the members of Sense of Place Committee, the members of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee, the members of the Keynote Speaker Committee, the members of the Mentoring Committee, and the members of the Executive Committee whose leadership allowed us to make immediate changes, alter the programming of the summer conference, and fund the self-study out of SABER’s budget. We appreciate all of the people who participated in the self-study, including those who completed surveys, attended an affinity group, or watched the presentation on diversity. We are grateful to the people who volunteered to facilitate the book club discussions and appreciate the people within the SABER community who attended the discussions.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.780401/full#supplementary-material

1We capitalize Black and People of Color (POC) but not white in this manuscript. This is in accordance with current Associated Press (AP) style standards that recognizes that there is a shared history, culture, and discrimination based on skin color for Black individuals or People of Color, but there is not the same shared experience for white individuals. Further, white is not capitalized to avoid legitimizing white supremacist beliefs. However, there is disagreement here and some scholars and organizations advocate for white to be capitalized (https://apnews.com/article/entertainment-cultures-race-and-ethnicity-us-news-ap-top-news-7e36c00c5af0436abc09e051261fff1f).

Ali, H. N., Sheffield, S. L., Bauer, J. E., Caballero-Gill, R. P., Gasparini, N. M., Libarkin, J., et al. (2021). An Actionable Anti-racism Plan for Geoscience Organizations. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 3794. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23936-w

Allen-Ramdial, S. A., and Campbell, A. G. (2014). Reimagining the Pipeline: Advancing STEM Diversity, Persistence, and Success. BioScience 64 (7), 612–618. doi:10.1093/biosci/biu076

Applewhite, D. A. (2021). A Year Since George Floyd. Mol. Biol. Cel 32 (19), 1797–1799. doi:10.1091/mbc.E21-05-0261

Asm Diversity, E. A. I. T. F. (2020). Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Task Force Report. Washington, DC.

August, A., Barnes, L., Booker, S., Boyer, C., Casadevall, A., Contreras, L., et al. (2020). ABRCMS Stands in Solidarity. ABRCMS. Available at: https://www.abrcms.org/index.php/component/k2/item/576-abrcms-stands-in-solidarity (Accessed September 16, 2021).

Belay, K. (2020). What Has Higher Education Promised on Anti-racism in 2020 and Is it Enough?. Available at: https://eab.com/research/expert-insight/strategy/higher-education-promise-anti-racism/ (Accessed September 3, 2021).

Bell, R. (2020). Eight Deliberate Steps AGU Is Taking to Address Racism in Our Community. Washington, DC: AGU.

Benjamin, R. (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA: Polity Press.

Bertuzzi, S., and Patel, R. (2020). ASM Calls for Equality and Unity. Available at: https://asm.org/Press-Releases/2020/ASM-Calls-for-Equality-and-Unity (Accessed September 3, 2021).

Bryson Taylor, D. (2020). George Floyd Protests: A Timeline [Online]. The New York Times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/article/george-floyd-protests-timeline.html (Accessed September 6, 2021).

Bumb, N. (2020). Corporate Silence and Anti-racism. Available at: https://www.fsg.org/blog/corporate-silence-anti-racism (Accessed September 3, 2021).

Calabrese Barton, A., and Tan, E. (2020). Beyond Equity as Inclusion: A Framework of "Rightful Presence" for Guiding Justice-Oriented Studies in Teaching and Learning. Educ. Res. 49 (6), 433–440. doi:10.3102/0013189x20927363

Campbell-Montalvo, R. A., Caporale, N., McDowell, G. S., Idlebird, C., Wiens, K. M., Jackson, K. M., et al. (2020). Insights from the Inclusive Environments and Metrics in Biology Education and Research Network: Our Experience Organizing Inclusive Biology Education Research Events. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 21(1), 25. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2083

Carlisle, M. (2021). The Debate over Qualified Immunity Is at the Heart of Police Reform. Here’s what to Know. Available at: https://time.com/6061624/what-is-qualified-immunity/ (Accessed August 20, 2021).

Carter, T. L., Jennings, L. L., Pressler, Y., Gallo, A. C., Berhe, A. A., Marín‐Spiotta, E., et al. (2021). Towards Diverse Representation and Inclusion in Soil Science in the United States. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 85 (4), 963–974. doi:10.1002/saj2.20210

Cech, E., and Waidzunas, T. (2019). STEM Inclusion Study Organization Report: APS. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color. Stanford L. Rev. 43, 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039

Downey, S. N., van der Werff, L., Thomas, K. M., and Plaut, V. C. (2015). The Role of Diversity Practices and Inclusion in Promoting Trust and Employee Engagement. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 45 (1), 35–44. doi:10.1111/jasp.12273

Folkenflik, D. (2021). After Contentious Debate, UNC Grants Tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones. Available at: https://www.npr.org/2021/06/30/1011880598/after-contentious-debate-unc-grants-tenure-to-nikole-hannah-jones (Accessed August 20, 2021).

Garcia, J., Sanchez, D., Wout, D., Carter, E., and Pauker, K. (2019). Society of Personality and Social Psychology (SPSP) Diversity and Climate Survey. Available at: https://spsp.org/sites/default/files/SPSP_Diversity_and_Climate_Survey_Final_Report_January_2019.pdf (Accessed August 20, 2021).

Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for Culturally Responsive Teaching. J. Teach. Education 53 (2), 106–116. doi:10.1177/0022487102053002003

Giroux, H. A. (2010). Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy. Pol. Futures Education 8 (6), 715–721. doi:10.2304/pfie.2010.8.6.715

Givens, J. R. (2021). Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching. Harvard University Press.

Gosztyla, M. L., Kwong, L., Murray, N. A., Williams, C. E., Behnke, N., Curry, P., et al. (2021). Responses to 10 Common Criticisms of Anti-racism Action in STEMM. Plos Comput. Biol. 17 (7), e1009141. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009141

Hagan, A. K., Pollet, R. M., and Libertucci, J. (2020). Suggestions for Improving Invited Speaker Diversity to Reflect Trainee Diversity. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 21 (1), 21–2122. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v21i1.2105

Hargarten, J., Bjorhus, J., Webster, M., and Smith, K. (2021). Every Police-Involved Death in Minnesota since 2000. Available at: https://www.startribune.com/every-police-involved-death-in-minnesota-since-2000/502088871/ (Accessed August 20, 2021).