- 1Department of Training Pedagogy and Martial Research, German Sports University Cologne, Cologne, Germany

- 2Department of Police, University of Applied Sciences for Police and Public Administration North Rhine-Westphalia, Aachen, Germany

Being a police officer bears the inherent risk of encountering violent conflicts while on duty. Federal reports on violence against German police officers document an increase in registered acts since 2011. However, apart from statistical data, little is known about the qualitive specifics of violent encounters within police operations. At the same time, national and international data point to problems of transfer between training and the field. Against this background, the following study presents the expert views of 29 German Federal police officers which have been interviewed about qualitative specifics of conflict dynamics they had experienced during operations and the extent to which they felt prepared for these situations by means of professional training. Results of the study reveal that violent encounters are perceived as complex, dynamic and ambiguous in nature, in turn demanding high standards of police officers’ awareness, decision-making and interaction skills, ranging from de-escalation to fighting. Moreover, the majority of police officers reported that police training lacked adequate preparation. The findings are discussed through the lenses of professional policing and police training in Germany. For the further empowerment of police organisations, police trainers and police trainer education, we argue that a solid and methodically controlled knowledge base on situational parameters of violent encounters is key.

Introduction

Police officers are exposed to a variety of demanding situations associated with the specific tasks of the job. Depending on the chosen career path (e.g., office service, riot police, cyber officer, special unit) professionals within the policing domain are likely to experience different types of violence in the course of their work. This is especially true for front-line policing, for example in the context of safety monitoring at airports or train stations. In the field, everyday police situations can take an unexpected turn from one moment to the next. A passport check, for example, can be amicable, but it can also escalate. The situation may return to normality and resolve peacefully, but it can also turn violent and endanger the physical integrity of police officers (Jager et al., 2013; Ellrich et al., 2011; Renden, et al., 2015b). To understand these differing outcomes of police-citizen interactions, researchers regularly point out the interactional dynamics of police-citizen encounters (Alpert 2004; Dai et al., 2011; White 2015; Todak and James 2018; Lee 2021). For example, using data from social observations Dai et al. (2011) found that police demeanour and their consideration of citizen voice significantly reduced citizen disrespect and noncompliance. In a similar vein, the results of an observational study by Todak and James (2018) indicate, that when police officers keep their emotions in check and interact with the citizen in a way that reduces the power differential predicted a calm citizen at the end of the encounter. In contrast, the concept of officer-created jeopardy (Lee 2021; Stein et al., 2021) explicitly points towards problematic tactical behaviours of police officers that deoptionalize officer behaviour beyond a certain point leaving very few behavioural options. In sum, these indicate the need for employing an interactional lense concerning qualitative specifics of police-citizen encounters. However, this lens is in need of interactional data in order to be employed. Those respective data are widely lacking for the German context.

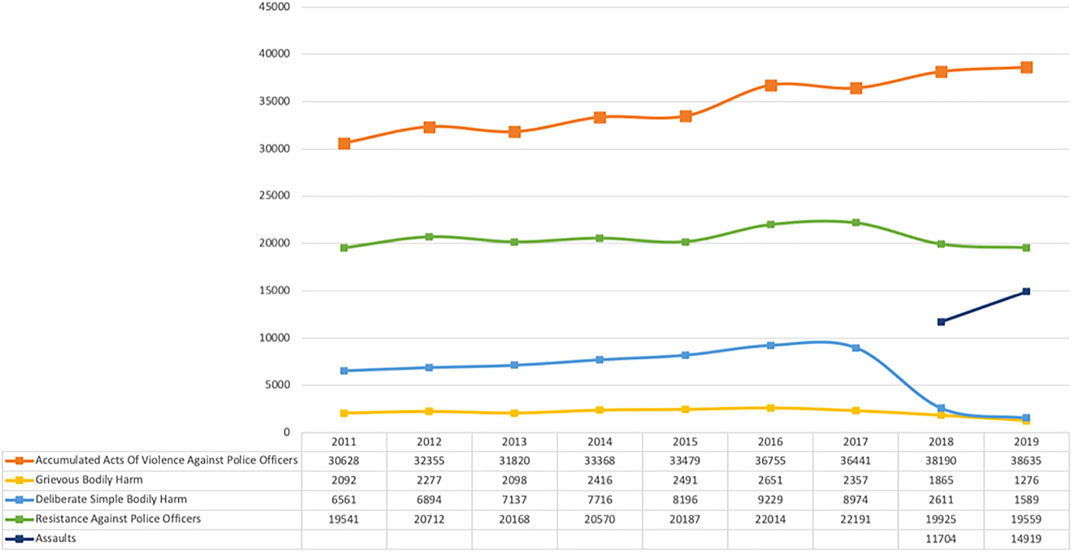

Instead, the German discussion within the public-media and scientific sphere focuses on statistical data on the frequency of violence against police officers. Annual reports of the German Federal Criminal Police Office regularly provide incidence-based empirical insights. Since 2011 the reports provide detailed information on the prevalence of violence against police officers, that is regularly present and debated with the media. Figure 1 shows the number of police officers having experienced violence in various forms in 1 year. From 2011 to 2019 the total number of violent encounters has increased by 21%, which is predominantly due to the increase in deliberate simple bodily harm, grievous bodily harm and resistance against police officers. In addition, since the introduction of the offence of assaults in 2018, the number of victims of deliberate simple bodily harm has decreased in comparison to the years before. In the case of grievous bodily harm, there was a significant increase in the period from 2011 to 2017, although the number of victimized police officers has decreased in recent years as well.

FIGURE 1. Violence against police officers in Germany by year (data from BKA, 2012–2020, own graphic).

Regardless of the question whether violence against police officers increases or decreases in statistical numbers (Derin and Singelnstein, 2019), police operations inherently bear the risk of being exposed to violence. However, while annual reports of the German Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA, 2020) provide important information on the frequency of deployment-related violence, the collected data do not provide qualitative information about the specifics of the reported violent acts, for instance about situational dynamics (Ellrich et al., 2014) or their impact on the police officers’ state and behaviour. Beyond statistical data, for Germany there are only few reliable findings which shed light into the emergence, dynamics and impacts of violent encounters experienced during frontline police work.

Ellrich et al. (2011) provided important insights into the characteristics of the situation in a study comprised of nearly 2,700 police officers from ten German state police forces who experienced violence on duty. In addition to temporal (day of the week, time of day), local (urban area, location), and perpetrator-related aspects (e.g., intoxicated), the study identified a high influence of communicative factors on the (non)occurrence of violence. From the perspective of the police officers, more than half of the assaults occurred during the phase of establishing contact, e.g., during arrests or the examination of suspects, as well as in the course of attempts at communicative de-escalation (Ellrich et al., 2011).

To date, there is little empirical evidence on the extent to which police training in Germany meets the preparatory demands for these real-world operational requirements. Police training pursues the goal of effectively preparing said officers for operational demands, especially for the professional handling of conflict and violence. However, the study of Jager, Klatt and Bliesener (2013) points out discrepancies between training and the field. Summarizing the qualitative part of their investigation, the authors state: “Overall, the interviewed PVB [police officers] said that the training and further education they have received does not lead to them feeling adequately prepared for attacks directed against them.” (p. 351). From the point of view of the police officers interviewed, the “techniques” covered in training do not transfer to the operational context in the desired way, which in turn can lead to a “feeling of helplessness” (ibid.).

The doubts expressed here about the effectiveness of police training and the accompanying desire for a more realistic approach by referencing characteristics of real-world violence dynamics are supported by findings from a recent study of Staller et al. (2021a) investigating perceptions of German police recruits. In the recruits’ point of view, police training lacks key informational variables which are present in the field. For example, they perceive it as problematic, that the role of the citizen in frontline policing is not as clear as in the training setting: “[…] you don’ know the other person, you are uncertain from the beginning whether it is the perpetrator, whether it is the victim […]. I know that nothing can happen to me in here, maybe a little injury, I have to expect worse things outside.” (TN12; Staller et al., 2021b).

Geared towards the German situation, the following qualitative case study aims to further explore this constellation by investigating police officers’ experiences of violent conflicts, qualitative characteristics of those conflicts and their respective views on preparatory police training. It is the first study explicitly focusing on 1) qualitative aspects of violent situations in duty as experienced by German federal police officers and 2) their assessment of the preparatory function of police training related to these experiences. Thereby, this study is underpinned by the assumption that a profound knowledge on the qualitative specifics of violent encounters in duty provides a key prerequisite for the empowering of police training, so that it can achieve its declared intention and function: to adequately prepare police officers for professionally coping with conflict and violence. For the content and pedagogical design of police training, data on qualitative specifics of police violence dynamics provide a central basis and orientation. As training for frontline work, knowledge about contextual factors, situational features, and typical interaction dynamics is essential for the professional planning, implementation, and evaluation of police training and police trainer education in Germany (Koerner and Staller, 2020a).

In this respect, the expansion of operational knowledge, especially focusing on qualitative aspects in the context of violent conflicts, is an urgent issue of concern. A sample of 29 German Federal police officers have been interviewed about conflict dynamics they had experienced during operations and to what extent police training had prepared them for coping with the respective demands. Since violence within the context of policing manifests itself in numerous forms of social interaction, the study’s perspective on violent conflicts covers a broad range of social interaction, including verbal, non-verbal and physical conflicts during police-citizen encounters (Buss and Arnold, 1961; Tedeschi and Felson 1994).

Materials and Methods

Method Selection

The course of violent police-citizen interactions could be properly analysed by using video data from body-worn cameras (Nassauer and Legewie 2019). However, in contrast to countries such as the US (Chapman, U. S. Department of Justice, 2019; Koen and Mathna 2019), in Germany material from body-worn cameras has not yet been considered as a source for systematically generating operational knowledge on qualitative aspects of violent encounters. Instead, the use of self-recorded video data by the police is currently limited to legal purposes. In line with said national constraints for the use of data from body-worn cameras, the study attempts a different approach.

Due to the access to the German federal police within the broader context of research projects related to police training, the study has been conducted as a qualitative case study utilizing semi-structured interviews with police officers. As a prominent part of qualitative research methods, interviews have their strength especially in delivering insights on issues of interest, using subjective perspectives and interpretations (Flick, 2018). Generally, police officers are deemed experts by value of their profession. Since experts own “technical, process and interpretative knowledge that relates to his or her specific professional or occupational field of action” (Bogner and Menz 2005), p. 46), police officers appear to be a promising source in the attempt to identify situational features and qualitative aspects of violent encounters during deployment. This may include specific contextual factors of police-citizen encounters as well as the unfolding dynamics of these situations. In contrast to statistical and video data, interview data has the advantage of also capturing how a single police officer subjectively experienced the violent situation. In addition, the interviews provide insights into the police officers’ perception of police training as a preparatory measure that all police officers in Germany have undergone. While we fully acknowledge the subjective interactional perspectivity of their accounts, we find value in this subjectivity in so far, that the police officers’ perspective may provide important insights of how police training is currently designed and delivered in Germany.

Data Collection

Within the literature on qualitative research, for single case studies a sample-size of 15–30 participants is recommended for data saturation (Francis et al., 2010; Marshall et al., 2015). The final sample of the following study consisted of 29 German Federal police officers (m = 26; f = 3), suggesting adequate information power (Malterud et al., 2016) for the research question posed. The officers had a mean age of 38 (SD = 7.35) and a minimum of 3 years of working experience in-service (M = 17.14; SD = 7.91).

The interview-guide comprised questions on the topics of violent experiences in duty as well as questions on the respective role of police training which had been derived from the review of relevant literature (see discussion above). After an opening question about their personal background and individual career-path, police officers were asked to comment on the following points (translated from German to English):

1) Please tell me what conflict situations have you experienced in the field.

2) Please describe one or two situations in further detail.

3) Please explain to what extent police training had prepared you to deal with the experienced conflicts.

The semi-structured regime ensured orientation along the topical domains, at the same time enabling flexible follow-up questions of the interviewer concerning the statements of the police officers. This structured sensitivity to participants’ views, as well as the individually varying level of experience, memory and detail in the reports, led to interviews of between 10 and 34 min of length (M = 19.86; SD = 6.81). Ahead of each interview, informed consent was obtained from all police officers, including the assurance of anonymity. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the German Sport University Cologne. The interviews were conducted and audio-recorded by both authors (SK, MS) and subsequently transcribed verbatim by trained research assistants (Kuckartz 2014). For the purpose of publication, quoted passages were translated from German to English.

Data Analysis

In order to support scientific rigor and credibility of the findings (Tracy 2010), the data analysis followed procedures of qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006), utilizing MAXQDA software (Kuckartz 2014). The analytical strategy was chosen according to the objectives of the study, thus employing concept-led (deductive) and data-driven (inductive) approaches for the systematic development of themes (Graneheim et al., 2017). The deductive coding of meaning units was based on the research question; that is 1) experiences of violent encounters and 2) perception of the preparatory function of police training (Braun and Clarke 2006).

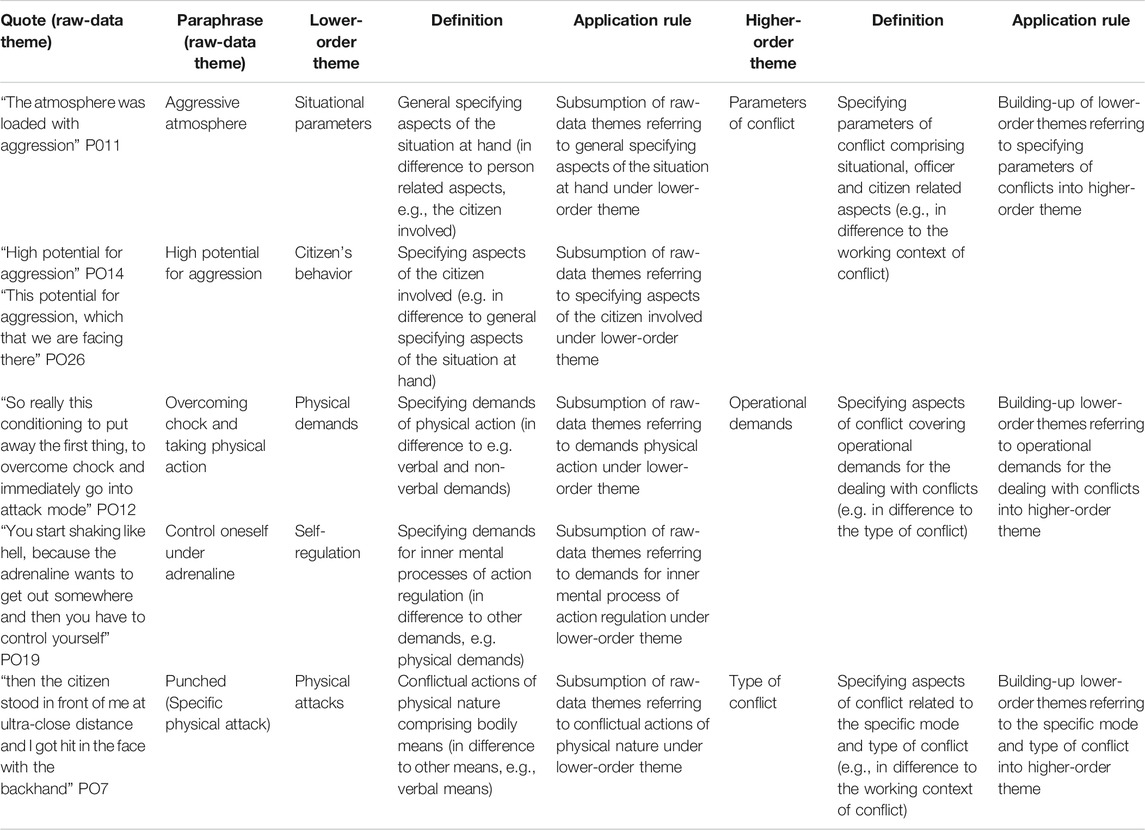

Due to the open approach to this rather unexplored field of interest, we additionally utilized inductive coding. Using the inductive approach, further meaning units relevant to the overall research question were identified and then assigned to further (sub-)themes (Biddle et al., 2001; Braun and Clarke 2006; Graneheim et al., 2017). Within both coding strategies, the database was analyzed and clustered into raw-data, lower-order, and higher-order themes. Raw-data themes were derived from the coding of relevant meaning units within the database. Identity in focal meaning (e.g., “hit in the face with the backhand”, police officer 07/“got fist punched in the face, so to speak”, police officer 10) led to the creation of raw-data themes by paraphrase comprising the generalized meaning (e.g., “punched”) and in turn allowing for the further subsumption of similar units under the existing theme, whilst difference in meaning led to the creation of a new theme (e.g., “spit”, derived from “one [person] spit”, police officer 23). The coding guide created after a first turn of fully coding the whole set of data, was then applied to the entire dataset for a second time in order to ensure a comprehensive analysis (see Table 1).

TABLE 1. Coding examples of building up process of raw-data, lower-order themes and higher-order themes.

In a next step, raw-data themes were coherently built-up into lower-order themes by generalising their focal meaning (e.g., “spit” and “punched” to “physical conflict” due to their physical nature). The set of lower-order themes had been re-examined by the second author beforehand, and both researchers had reached a consent on said themes by using questions and debates (Abraham et al., 2006). Subsequently, the sub-themes were generalised on a further abstraction level of meaning and built-up to higher-order themes (e.g., “physical conflict” and “verbal conflict” to “types of conflict” due to their difference in mode but similarity in being conflictual). Higher-order themes were again critically evaluated by the second author before eventually being set. At the level of raw-data themes, meaning units providing qualitative information on violent encounters and assessments of the effectiveness of preparatory training were quantified according to the frequency of their mentioning by single participants. At the level of lower-order and higher-order themes, meaning units have been quantified according to their overall occurrence. Although “the “keyness” of a theme is not necessarily dependent on quantifiable measures” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 82), the total number of mentions provides important insight into the subjectively perceived relevance of individual themes within the study sample and thus “captures something important in relation to the overall research question” (ibid.).

Results

Experienced Conflicts

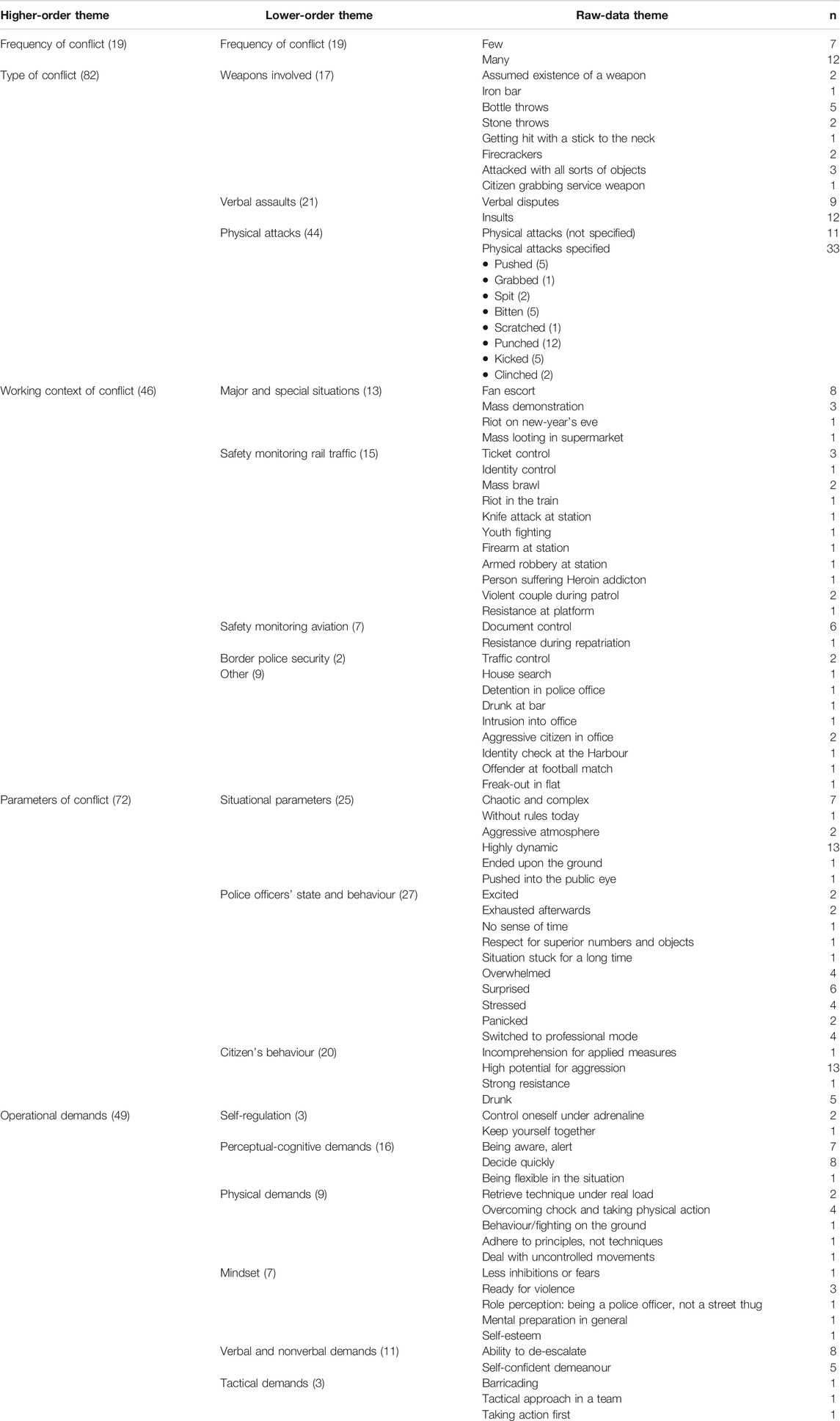

With regards to police officers’ personal experiences of violent encounters in duty (issues 1 and 2, see Data Collection), data analysis revealed five higher-order themes that are presented in Table 2: 1) frequency of conflicts; 2) working context of conflict; 3) type of conflict; 4) parameters of conflict; and 5) operational demands.

TABLE 2. Results of qualitative analysis of conflicts experienced by German federal police officers (Numbers in column “n” denote the number of participants contributing to the raw-data theme; within the columns of lower-order and higher-order themes, numbers in brackets denote the total number of meaning units).

We are aware that theses higher-order themes are interrelated. Given the rather open focus on experiences of conflict situations and on implicitly what the interviewees ascribed relevance to it (throught mentioning it), we place the higher order-themes in the foreground individually and in sequence. However, this separation is purely analytical in nature. In reality, the higher-order themes of conflict situations, which are presented in excerpts based on quotations, are inextricably linked. Thus, the exemplary presentation of, for instance, the working context of a violent conflict also provides insight into the dynamics or type of conflict. Notwithstanding this, we have decided to reproduce longer quotes from the police officers’ descriptions in order to give the reader a denser and more vivid insight into the conflict situation experienced. The respective higher-order theme merely represents the chosen focus of the analytical view.

At this point, it is important to note that the higher-order themes identified within the sample do not allow for further generalisation, but rather have their value within the sample and within the issue the German federal police officers were asked to comment on (“Please describe one or two situations in further detail”). The cases of the sample stand for themselves.

Frequency of Conflicts

The frequency of conflict describes the perceived frequency of conflictual situations while on duty. When asked about violent situations experienced in the line of duty, all police officers elaborated on at least one (12) or two (17) concrete incidents in further detail, leading to a report of a total of n = 46 conflict situations. Many (but not all) of them began their reflection with an estimation of the frequency of violent encounters in general. Police officer 05 represents the group of colleagues (n = 12) that reported already having been confronted with violence on duty many times.

“There are many. Be it violence from the crowd, be it violence three against one or three against two, group dynamics, violence from the group. I have experienced a lot, because I am in the riot police’s arrest squad, which is deployed in these hot spots. Or sometimes house searches, even one to one.” (PO 05)

However, not all police officers reflecting on the frequency of violent experiences during operations stated that “conflicts are an everyday appearance” (PO 12). For instance, the perception of police officer 02 represents the group of interviewees who reported having experienced only a few conflictual situations in duty so far:

“So, I’ve actually only had real resistances like that twice. Twice. Otherwise, I always got along quite well while policing.” (PO 02)

Type of Conflict

Police officers reported different types of conflict within their accounts of experienced conflictual situations. The type of conflict comprised a total of n = 82 meaning units. The theme is made-up of physical attacks (n = 44), verbal assaults (n = 21) and the involvement of weapons (n = 17), displaying the broad range in which violence had been experienced during deployment. For instance, police officers 07, 08, 09, 11, and 16 recalled having bottles thrown at them as improvised weapons on several occasions, representing a special type of attack, because

“when bottles are thrown at you, you don’t always have direct access to who did it, because you don’t really notice where it came from.” (PO 09)

This is somehow different to the type of physical attacks, in which the violent interaction is based on direct contact between the police officers and citizens. Within this lower-order theme, many police officers reported being punched, kicked, bitten and pushed. Typically, the different types of attacks used to follow each other and alternated, as experienced by police officer 07 at a demonstration during the G20 summit in Hamburg:

“We just got out of the car to prevent it and then an offender jumped into my colleague with a jumping knee, I would call it, bounced off him a bit, stood in front of me at ultra-close range and hit me in the face with his backhand. That was an attack that is still very present in my mind because it was launched from such a close distance.” (PO 07)

In many cases, especially within the reported control situations, physical conflicts were preceded or accompanied by verbal assaults. During a patrol at the railway station, one of the interviewees recalled a situation in which

“a person, who was apparently completely against the police, began to insult us in passing with such insults as “You fucking cops”, “Get out of here”, “You have no business here”, “We don’t want you here”. Then we wanted to make an identity check in line with the protocol and file a report for insults. He then went completely berserk, stormed towards us and wanted to hit us. We had to bring him to the ground and restrain him. Even when he was tied up he continued to resist in such a way.” (PO 06)

On the other hand, several of the reported experiences of violent encounters were limited to verbal offences, such as the following insult, experienced by police officer 23 during a passport control at the airport:

“There was a very interesting situation for me. At the very beginning I came to the airport and I was checking in the passengers. And there was a citizen standing in front of me pointing at my epaulettes and saying to me in English that I’m “a nothing”. And first I thought, okay what is this? What is he doing? What does he want from me now?” (PO 23)

Working Context of Conflict

Within the data, the experienced conflicts had been specified by contextual information, displaying a localisation of encounters that can be expected in the area of use of German federal police officers. Even if the contexts mentioned do not provide any representative information on the operational contexts of German federal police officers, they nevertheless give valuable indications as to which operational contexts are considered newsworthy and thus relevant by the police officers surveyed. Most of the reported incidents took place within the context of safety monitoring rail traffic (n = 15), safety monitoring aviation (n = 13) and major and special situations (n = 13). Within the latter, fan escorts on the periphery of football matches (n = 8) provide the most frequent contextual frame of violent encounters reported by the interviewed German federal police officers, followed by deployments alongside of mass demonstrations (n = 3), such as those around the Gorleben nuclear waste repository. For instance, PT 13 recalls an incident during which a protester almost removed the officer’s firearm from his holster without him noticing as follows:

“That was also a drastic experience, where you thought: OK, that happened during the scuffle. We had those other holsters back then, not these safety holsters that we have now. At that time, we were at the nuclear waste repository in Gorleben. It must have been the mid-nineties. The blockades were first secured with a police cordon. Usually, the water cannon came and then the protester were surrounded and carried away from the site. Then I noticed that someone had already reached for the gun.” (PT 13)

The encounter of a group of violent football fans alongside a premiere league match as reported by PT 04 provides a detailed insight into the situation he and his colleagues were in:

“If we want to talk about football, we were deployed here in Gelsenkirchen once. We simply closed off the lower area from the upper area at the train station to the Christmas market. There, in the public area there were fans, who were pursued by, I don’t know, about 50 hooligans came towards us. Then the space became narrower, funnel-shaped narrower and we closed it down, then we had to retreat. Everyone fled into the stands, also the passers-by and then it was channeled a bit. That slowed down everything that was happening. Then, full blast, so with sticks and fists we simply drove the crowd back. That was very explosive, because it was getting tighter, it was a mess, some people crashed, so also to keep the people together or to look for themselves, but then you were more or less on your own to find yourself again.” (PT 04)

In the context of safety monitoring at German airports and rail stations, control situations (ticket control, passport check) attracted the highest number of reported conflicts within the sample. As an example of this working context, the following experience of police officer 06 is presented here, in which he had to track and secure a single suspicious person:

“The second situation I can remember relatively well was during a document inspection at the aircraft. A person presented me the passport. I noticed that something was wrong with the passport, then I looked at his height and noticed that it said 1.65 m, but he was clearly taller than me, which was the first indication that something was wrong. I then made it relatively clear to him that he would now accompany us to the police station because we would have to take him back to check his document, which he then immediately took advantage of and out of reflex practically passed us and fled. And of course we, that is a colleague and myself, immediately followed him and I then tried to hold him by the shoulder. He then broke away twice and in the end I was the only one who managed to stop him after I approached him from behind and was able to grab him by the leg. Then we both fell forward head-on and the colleague joined us. He was half a metre to a metre behind me and we were able to fixate him on the ground, but we did not have his arms yet. We had to use a lot of force and a few nerve pressure techniques to force him to give up his arms, because he had always blocked them under his body and then, thank God, he accepted his fate relatively quickly and allowed himself to be tied up and transported to the police station without any further situation arising.” (PO 06)

Parameters of Conflict

Within the retrospective views of the interviewed police officers, parameters of conflict (n = 72) are of high relevance. Those parameters could be subdivided into parameters related to the overall situation (n = 25), to the citizens involved (n = 20) and finally to the state and behaviour of the police officers themselves (n = 27). Within the experienced conflicts a high potential for aggressive behaviour (n = 13) among citizens had been perceived. The relevance of this parameter was for example articulated by police officer 17. During an operation at a train station where several young men had been involved, his colleague had to be taken to a hospital after “the aggressiveness of the police counterpart, (who) immediately struck my colleague and also brutally started to punch” (PO 17).

According to many police officers, aggression is seen as a potential that can unfold “spontaneously” (e.g., PO 06). It was also stated that “nowadays” (PO 26, PO 28) there is a generally lowered inhibition threshold for violence against police officers. In several cases, however, the aggressive behaviour of the citizen was accompanied by an alcoholic state (n = 5), as for example during this riot in a train reported here:

“There was a person who was rioting in the ICE, so he was very drunk and very aggressive and also insulted the people. And he was already sitting in his seat again and was actually just supposed to get off the train. We talked to him, the situation got out of hand. A colleague was standing in front of me. I was standing behind the person. Then the person got up and wanted to hit my colleague in the face and I took advantage of the moment, because I don’t think he noticed that I was standing behind him because he was so drunk, and I intercepted his arm and was able to immediately put him in a restraining grip and basically stopped him from hitting me. Then I had him quite safely. Then we took him out of the train, and at that moment a unit from the police force of Hesse joined us and supported us again because he put up a lot of resistance, so we brought him to the ground with several colleagues, tied him up and carried him to the police station.” (PO 29)

Next to the citizens behaviour, situational parameters of conflicts had been mentioned, forming a significant lower-order theme within the police officers’ perception (n = 25). Conflictual situations are perceived as being inherently complex, chaotic (n = 7) and foremost: highly dynamic (n = 13). In many reported cases, conflict situations altered in a split second, turned literally “from zero to one hundred” (PO 16), evolved practically “out of nothing” (PO 21) and lacked clarity. Looking back on the situations he experienced, interviewee 10 describes the situational quality as follows:

“It happens relatively unexpected sometimes as well. It is a normal search and he launches a headbutt directly, or it is a normal document search and he runs away, where you could say that sometimes it is difficult to recognise that something is about to happen. If you don’t really have an affinity for it and you’re not prepared for it, it’s really, really hard to recognise that the situation is about to get dicey.” (PO 10)

Finally, the police officers’ state and behaviour (n = 32) completes the qualitative parameters of conflict. In coherence with the already highlighted key themes, police officers denote their own mental state during violent conflicts as being stressed (n = 4), surprised (n = 6) and overwhelmed (n = 4) throughout the situation, “not knowing how to deal” (PO 10) with it. At the same time, some interviewees report that they were shifted into professional mode (n = 4), being much more alert and made ready for the use of violence.

Operational Demands

Finally, operational demands (n = 49) emerged as a higher-order theme displaying a certain relevance in the police officers’ reflection of conflicts that they had experienced. Within this thematic complex, perceptual-cognitive demands (n = 16) were mentioned the most, followed by verbal and nonverbal demands (n = 11), physical demands (n = 9) and mindset (n = 7). The perceived qualitative specifics of conflictual situations and portraying them as inherently complex, dynamic and shaped by the citizens’ aggressiveness, aligns with the enumeration of significant demands on police officers which are based on those qualities. Within an unclear situation

“incidents don’t always announce themselves. People just stand in front of you at a short distance and decide to attack all at once … you have to focus on what is really important at that moment, e.g., how is the person behaving, how is his or her state mood or what is happening here right now? That’s what you really need in practice, namely the right reaction within the shortest possible amount of time.” (PO 01)

This perception of police officer 01 had been confirmed by several colleagues pointing to operational demands which address the perceptual and cognitive domain: Conflict situations call for quick decisions (n = 8) and a heightened awareness (n = 6) for the selection of action guiding cues. As police officer 12 puts it:

“I have to recognise that there is a danger. I have to decide how to react to the danger. And then I have to do something, which does not have to be technically perfect, but it has to work.” (PO 12)

According to the data-driven typology of conflicts comprising physical and verbal encounters, the interviewees stated that conflict situations demand sound action capabilities in the respective domain. The police officers’ ability to de-escalate in an atmosphere of aggression, for instance, is mentioned frequently (n = 8), thereby showcasing even more thematic relevance than the physical ability for overcoming the shock and taking action (n = 4) or the correlated mindset of being ready for violence (n = 3) in situations that have already escalated. Furthermore, within the non-verbal domain, self-confident demeanour (n = 5) is deemed important. To the mind of police officer 16, displaying self-confidence during conflict situations is linked to de-escalation: “So if one has the right demeanour, this can already have a de-escalating effect.” (PO 16)

In this regard, one of his colleagues points out that for purposes of de-escalation, the fine line between displaying self-confidence and displaying arrogance has to be acknowledged, since the latter can provoke opposition and create resistance. The officer states:

“That doesn’t have much to do with ego, so nothing to do with ego or overestimation but simply with a certain kind of self-confidence and security that I have to have towards the person... I don’t want to provoke any resistance.” (PO 03)

This kind of perception is reinforced by police officer 02, who emphasises the reciprocity of behavioural outcomes, an effect that especially the police officers involved in the interaction should be aware of: “Many things are based on how one behaves oneself: What goes around comes around.” (PO 02) The practical relevance of de-escalating behaviour in critical moments becomes clear in the following conflict situation reported by police officer 23. The situation was about to escalate into a physical conflict when she had to deal with an indignant citizen who could not be calmed down by any other colleague:

“We were called in, it was about, I think it was [anonymized], who was behaving very aggressively with several colleagues. Yes, he had already had a verbal altercation, he was shouting and we just got involved and he saw me and fixated on me, but not in a negative way, but in a positive way. That means that in the end I was the only one who could direct and control him a bit, because he reacted to me. And it was a situation that was very tense. He was also difficult to calm down. But through this verbal communication and for whatever reason he had chosen me at that moment, we actually managed to calm him down to such an extent that we were able to get him out of the masses, out of this room. We took him to the office and did everything else there ... He didn’t let anyone touch him, he didn’t let anyone get close to him, and in the end, we were able to take him with us in a really sensible way.” (PO 23)

While in this case it was the verbally de-escalating behaviour of the police officer that led to the citizen focusing on her and letting her calm him down, the second situation described by the same officer shows that things can always turn out differently in the field. In this case, the solution to the situation at hand required an adaptive use of resources:

“A fare dodger was discovered by the DB [the railway company]. He refused to talk to them. We then came to take his personal details and he did not act normally. He wasn’t agitated, he was just very, very calm. We asked him to give up his personal details and out of nowhere he lashed out and wanted to hit me first and then run away. And then I grabbed him by the arm, he was wearing a thick winter jacket, and he wriggled out of it. Then the colleague came and folded him up on the floor, (laughs) like a jack-knife. Yes, and then it actually happened very quickly. So we lay on him like that. We actually did everything without thinking.” (PO 23)

Experienced Conflicts and Police Training

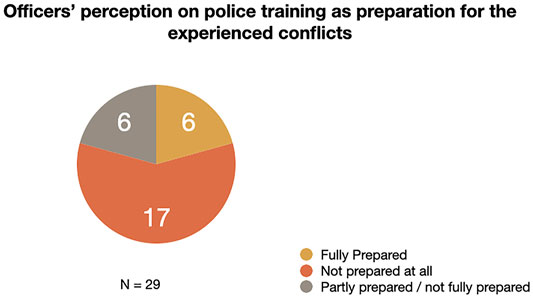

With regard to the question as to what extent police training prepared them for the violent conflicts they had experienced (question 3), six out of 29 police officers confirmed that they had been prepared adequately, whereas 17 interviewees stated that the training did not serve this purpose at all (see Figure 2). In another six cases, police officers gave a differentiated assessment in which both functional and dysfunctional aspects were mentioned (partly prepared/not fully prepared). For instance, one officer reported that in front-line situations “the tear-back technique, practised thousands of times in training, worked fairly well” (PO 26), while mental preparation for operational requirements “was almost non-existent” (ibid.).

FIGURE 2. Police officers’ perception on whether police training had prepared them for the conflicts they had experienced.

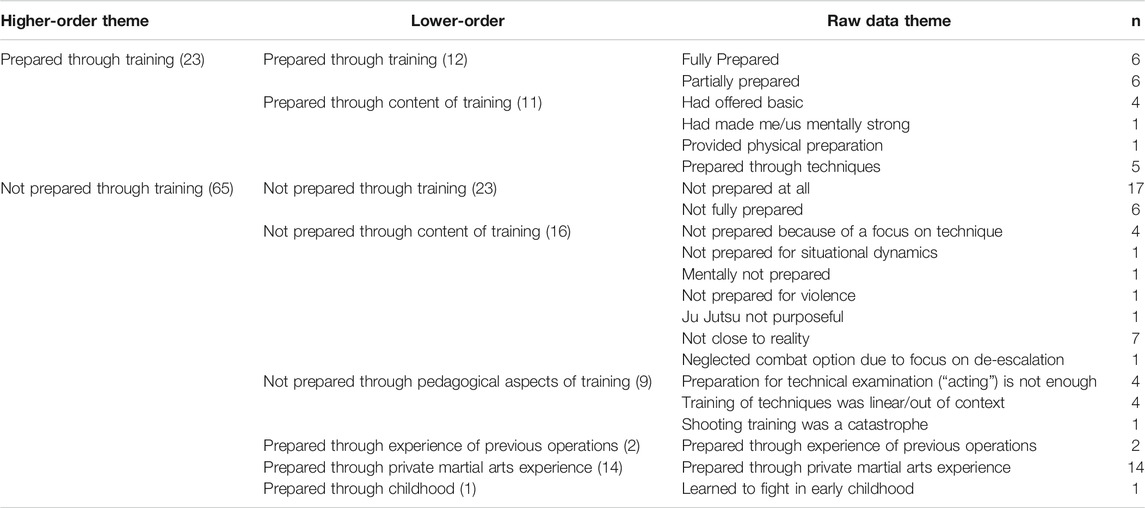

Furthermore, data analysis revealed that a significant number of raw-data themes contribute to not prepared through training (n = 65), as compared to prepared through training (n = 23), as shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3. Results of qualitative analysis whether training prepared for experienced conflicts (Numbers in column after raw-data theme denote number of participants contributing to the raw-data theme; numbers in brackets denote total number of meaning units for lower-order and higher-order theme).

Prepared Through Training

Six out of 29 police officers assessed that training had prepared them for the conflicts they had experienced. A further six stated that this had at least partially been the case. For the thematic complex of prepared through training, aspects of content (n = 11) were deemed relevant. More specifically, police officers stated that police training had offered the basics (n = 4) for dealing with real-world conflicts. While police officer 11 stated that police training “actually had not prepared me at all” (PO 11), he subsequently puts the assessment into perspective. With regard to arrest situations he experienced in the line of duty, which differed from the situations experienced during training, he still states that the training has taught him/her the basics for a successful handling of said arrests:

“Although arrests were trained, in the context of this chaos, I was only a functioning, clearly with basics that I had received from the police training. Taking down somebody was automatised.” (PO 11)

Like police officer 11, another three colleagues also emphasised that the police training had given them the necessary basics for dealing with the experienced conflict situations. In the perception of police officer 04, for instance,

“jujutsu, the system we basically trained back in the days, was sufficient for the time being. It wasn’t particularly spectacular, but you had your basic tools.” (PO 04)

More specifically, several police officers mentioned the value of techniques learned in police training: “There are already techniques that you use, which give you a certain amount of safety” (PO 26), as one interviewee states. However, the same officer continues by acknowledging that he had experienced limits for the use of those techniques in real-world situations: “The fact that they don’t work like that in reality, those are experiences that you only make in reality.” (ibid.) Interviewee 15 arrives at a similar assessment, on the one hand emphasising the usefulness of learned techniques and on the other hand pointing out the limits of their applicability in real-world settings. He states:

“Of course, all the joint locks we’ve trained were good. It also helped me a lot, but it was rather secondary. When you have someone on the ground. Then you do a little bit here and a little bit there, but that you really do a sophisticated arm bar or a finger lever, that rarely happened. It’s always this mishmash...”. (PO 15)

The techniques learned in training were good, they had helped. However, when put into the context of front-line policing, its quality, which has been parametrized before in great detail and is coded here as “mishmash”, forced the officers to adapt said techniques. Along with this, a perceived difference between training and field comes into play. Police officer 14 puts it this way:

“Police training always offers only a partial basis. The rest, which you then acquire in reality, is then, in my opinion, flexibility, and in some cases, you cannot train this at all, because the situation is quite different.” (PO 14)

The quote “the situation is quite different” condenses a view of major relevance within the police officers’ perception, articulating that training had not prepared them adequately for competently dealing with conflictual situations in front-line policing.

Not Prepared Through Training

17 out of 29 police officers stated that their former police training had not prepared them for the conflict situations they reported at all. Police officer 07 puts it this way:

“Well, I hate seeing things negative, but if I’m honest, I have to say that the police training didn’t help me at all.” (PO 07)

With regards to police officers’ personal assessment of not having been prepared, data analysis revealed a significant number of raw-data themes referring to the content of training (n = 16) and to pedagogical aspects of training (n = 9). Finally, another thematic category emerged from a number of the officers’ statements, which explicitly attributes the preparation for the experienced conflict situations not to police training, but to a private origin: The fact of having a biographical background in martial arts provided the main resource for feeling able to competently deal with conflicts in deployment. A fact that was stated by n = 14 police officers.

Within content of training a number of police officers pointed to remarkable differences between the field and training, stating that the latter was not close to the reality of the field (n = 7) and suggesting a lack of realism in police training. This point is, for example, made clear by police officer 20 as he describes one of the conflicts he experienced at the airport in further detail:

“In the transit area, the US demanded a ten percent follow-up check from us at random. And our task was actually only to pull out those who wanted to go to the US or who were coming back from the US and then hand them over to a team from [anonymised] Security, who checked them again. A couple came, and he let himself be checked normally. He didn’t question it. But she completely lost it during the check, not because of our search, but because of the [anonymized] security. So without any indication, at least we didn’t recognized any, she completely unleashed, head-locked one of the officers and kicked a second one. We joined in and had to restrain her. She was like in such a frenzy. She was completely out of control. It was the first resistant behaviour for me where I realised that it doesn’t work like on the mat.” (PO 20)

In this retrospection of an experienced front-line conflict, the difference between “the mat” and the dynamic quality of real-world violence leads to the important conclusion: In the context of dealing with the sudden release of physical resistance and chaotic attacks, the police officer realised that reality differs from training. Despite that, to the mind of several other interviewees, training was not geared towards realism. On the contrary:

“That was the mat, you had more of a feeling as if you were preparing for a competition. That was a dojo, with a [martial arts] suit, and all that had nothing to do with the street … And otherwise it was just all so stiff ju-jutsu ... There was this, yes, I don’t know how to describe it, this street-like thing, it was not in there.” (PO 08)

When seen through the lens of the qualitative specifics of the experienced conflict situations described above, police training is depicted as being rather stiff and oriented towards traditional codes of the martial arts, therefore not being very ‘street-like’. On the other hand, fast decision-making and spontaneous eruptions of violence, as well as the application of de-escalation skills when dealing with aggressive citizens in dynamic, complex and chaotic situations characterise the process of dealing with conflicts during frontline work:

“Well, police training was absolutely not geared in this direction. And that is still not the case today”. (PO 06)

According to this view, police training lacks realism. Within the domain of issues related to the content of training, foremost techniques have been problematised. In n = 4 cases, the deficit in preparation is seen as being related to dysfunctional techniques that had been practised in police training. Police officer 13 clarifies:

“The police training that was done, generally what we did in this ju-jutsu. It was actually not effective. The techniques always failed in reality … these techniques with arm bar that existed were actually rather ineffective.” (PO 13)

Police officer 05 also attributes the lack of preparation for real conflict situations to a focus on techniques that largely lacked a functional application in reality. In this case, impacted by conflict parameters and operational demands, the technique failed during the specified situation as well, that is why

“you can’t say I was prepared. Because the techniques we learned in the old curriculum, I rarely applied them until now, when I experienced it outside. The only thing we were sure of was the procedure when it came to restraints. So, the hand locks, they worked. But these techniques to get to the ground always ended up in wrestling (laughs). No matter how, the main thing is that we go to the ground.” (PO 05)

In addition to the content issues, there were a considerable number of raw data themes that contributed to the cluster of pedagogical aspects of the training (n = 9), which were also viewed as being responsible for the circumstance that the police training did not prepare adequately for deployment. Within this thematic complex, the repetitive learning of single techniques out of their context of relevant parameters of conflict, is held responsible. Police officer 20 provides a detailed insight into this issue, which is related to the pedagogical design of training:

“In principle, we were asked to repeat techniques over and over again in a calm atmosphere, in a laboratory situation, so to speak. There were few or no surprises, neither in normal training nor in the situational training. Because even in situational training, where you don’t actually know beforehand how exactly the situation will unfold, you already knew the intensity levels beforehand. Yes, you were told, ‘Watch out, you’re going to be in a situation, but it’s going to be very relaxed. Just be communicative.’ So, we were already prepared for it and that’s how it happened. It would have been better to have said ‘Take it easy, it’s probably going to be a calm thing.’ And all of a sudden, (claps) two intensity levels on top of that there is a surprise from the side. Because then I would say in hindsight after such a training, that I would have gotten to know myself better. I would have understood better how I react in such a situation. Am I capable of acting or am I paralyzed at first? Am I in a kind of shock state where I can’t really sort out my thoughts at all? I had to wait for these experiences until I was in frontline police work. Also that’s why, in answer to your initial question, no, I did not feel well prepared.” (PO 20)

The repetitive practicing of techniques is foremost seen as problematic due to the missing connection to the relevant parameters that are representative of conflict dynamics in the field, such as surprise and uncertainty. Instead

“a lot of blunt movement sequences were simply trained with the same input over and over again. But this does not reflect what might happen on the street or in the field. I had the feeling that there was always a certain prompt in the training, that is, for example, attack with the right hand now and then please do this and then use that specific defence technique. But that doesn’t really reflect reality.” (PO 01)

The linear technical approach to solve a known problem (e.g., “attack with the right hand”) with a prescribed technique (“that defence”), underpinned by the linear teaching model of “if x, then y”, is also problematized within the context of testing and evaluation, in which

“the technique had to be performed correctly and that it is not so much the outcome that counts in the end, but rather that the technique was beautiful. Then, of course, it always becomes acting. Of course, I can show a much more beautiful technique with a partner who is acting nicely, than when someone really resists. And our whole examination system, which is still the same, is designed more for the correct showcasing of a technique, so more for a spectacle than for the realistic fight outside, because of course we all know if it is a fight, what it will be outside, then it always looks messy and you won’t see much technique in it.” (PO 03)

As in normal training, the problem with examinations is that a demonstration of beautiful techniques, while excluding realistic constraints, is considered more important than a proper check of the ability to act “when real resistance comes into play” (PO 05). Whilst reality is messy, training and examinations on the other hand stage a well scripted choreography:

“I always call it acting. That such a training takes place, the techniques are shown, the aspirant has understood the technique, he also knows the technique, but he has never used it when real resistance exists. That’s what happens with us. And that’s what happened to me at the time.” (PO 05)

Finally, a further lower-order theme deserving attention when analysing the question on whether and to what extent police training had prepared them for conflict emerged from the data set. A total of n = 14 police officers reported that not professional police training, but having a private martial arts background provided the main resource for the ability to competently deal with conflict situations. Police officer 07 states:

“But if I’m honest, I have to say that the police training didn’t help me much at all, so for almost all situations ... through the skills that I acquired in martial arts I was able to solve quite a lot... I have drawn a lot from that. But not much, if anything, from the pure police training.” (PO 07)

Police officer 09, who has practised ju-jutsu and kickboxing in private, emphasises the impact of private martial arts as a key preparatory means for successful policing:

“Actually, police training itself didn’t really prepare me for this. I relied more on my private background. But the pure police training itself, I rather don’t rely on it.” (PO 09)

Discussion

For Germany, the results shed light onto so far under-researched qualitive specifics of violent conflicts as experienced by German federal police officers. Furthermore, the findings reveal valuable information concerning the significance of police training as a preparatory means in this regard.

Although not every interviewee gave an estimate on the frequency of personally experienced violent conflicts, all of them reported at least one specific. As such, it can be assumed that violent experiences related to their job are an issue of concern within the sample of this study. The result is in accordance with statistical data of the past decade (Bundeskriminalamt 2015; Bundeskriminalamt 2020), indicating an inherent and case-by-case risk of German police officers being exposed to violence in the field, while acknowledging that the question of causality within the development of violence cannot be answered at this point (Ellrich and Baier, 2021).

Within the reported cases, different types of violent conflicts were deemed as relevant by the interviewees, showcasing a major focus on physical attacks, followed by verbal assaults. The dominance of physical violence is in line with current data on the prevalence of violence against police officers (Bundeskriminalamt 2020). However, at this point it has to be considered that e.g., the annual reports of the German Federal Criminal Police Office are mainly focused on physical violence. As a consequence, this may lead to the perception that violent conflicts in policing are basically physical in nature. In light of the research on violence and aggression, it becomes clear that this is not the case. Instead, the micro-social interaction of violence in policing encompasses a broad range of types (Tedeschi and Felson 1994; Collins 2009). In this study, the experts’ reports on violent conflicts support this finding: In the context of control situations for instance, data indicated both that conflict dynamics were limited to verbal means, as well as that they were preceded by verbal confrontations and eventually result in physical violence. One way or another, communication plays a major role in violent encounters of German federal police officers.

Furthermore, study data yielded valuable information about the working context in which said violent conflicts had been experienced. Although violent encounters do have a contextual index per se (they take place somewhere), for Germany, there is less empirical knowledge on their context-specificity (Ellrich et al., 2011; Reuter, 2014)—for federal police officers, which were the subject of this study, there is even none at all. In this vein, mainly control situations at the airport or at train stations, e.g., during passport checks involving individual citizens were mentioned. On the other hand, fan escorts on the periphery of football matches turned out to be another frequent context of violent encounters, involving a mass of people on both sides. The range of identified contexts is influenced by the use of a sample group consisting purely of German federal police officers, which are primarily tasked with border protection and security in the context of major events.

The potential of different types of conflicts, including the involvement of improvised weapons, account for a distinct quality that is inherent to violence itself. Therefore, parameters of conflict that have been identified within the data are of special interest. On the side of the citizens involved, a high potential for aggressiveness, occasionally unfolding into brutal violence in a spontaneous manner, has been pointed out. The data additionally addressed the fact that this process is sometimes accompanied by an alcoholic state of said citizens. Furthermore, qualitative parameters specifying the overall situation were deemed important, such as complexity, chaos and high dynamics, which for instance refers to conflict situations in deployment that altered in a split second and went “from zero to one hundred”. In view of these parameters involved, the police officer’s state and behaviour are affected, leading to feelings of stress, surprise and overload. These findings are in line with other current research, indicating that violent encounters in policing are accompanied by the element of surprise and high levels of aggressiveness (Jager et al., 2013; Giessing et al., 2020; Renden, et al., 2015b). Importantly, according to psychological (Groves and Anderson 2018; Lansford 2018; Parrott and Eckhardt 2018) and sociological (Collins 2009) explanations of violence, the parameters of conflict are likely to interact and affect each other in rapid succession.

In light of these conflict parameters, it seems plausible that the data reflect another topic–highlighting important demands on the side of police officers. In the interviewees’ point of view, dealing with conflicts such as those that were reported, calls for awareness and quick decision-making in the domain of perceptual-cognitive skills, as well as for the ability to de-escalate situations in an atmosphere of aggression, or for taking physical action. These aspects represent the domain of verbal and physical demands. Finally, the value of a self-confident demeanour during conflict situations is emphasised by the experts. These results align with existing research, touching on the question of how performance under pressure (Nieuwenhuys et al., 2015; Frenkel et al., 2021) and decision-making in stressful situations (Baldwin et al., 2019; Jenkins et al., 2020a) can be optimized in light of the demanding tasks police officers are confronted with during deployment. For instance, as Jenkins et al. (Jenkins et al., 2020b) recently investigated, applying the use-of-force option in conflict situations impacts the physiological stress response of police officers, which may in turn be associated with further performance impairment. Interestingly, the reciprocity of behavioural outcomes, and more specifically the issue of police officers’ demeanor in police-citizen interactions, has rarely been the subject of research yet (Alpert 2004; Dai et al., 2011; White 2015; Todak and James 2018; Lee 2021). For Germany, research on qualitative aspects, such as situational parameters, of police-citizen encounters is still in its infancy (Jager et al., 2013; Ellrich et al., 2011). The data provided here underline the important role of future studies by shedding more light upon qualitative specifics of conflict interactions in policing.

The ability to professionally cope with conflict situations requires training. However, according to the majority of police officers interviewed in this study, police training had lacked crucial input when it came to serving this purpose. When asked to reflect on the functionality of police training in reference to a concrete conflict situation they had experienced, a vast number of police officers pointed to problems during training that limited its function. This finding is of high interest, since for police training in Germany, little is known in regards to its effectiveness (Staller et al., 2021a; Koerner et al., 2021b). The experts’ opinions point to problems of content and pedagogical aspects related to the design of training, which were mainly identified as an overall poor relationship between training and application in reality, putting an emphasis on dysfunctional techniques and isolated exercises. Although programmatically serving as training for the field, the training lacked key contextual parameters of the field, e.g. surprise, mental stress and ambiguity. It is noteworthy that a large number of police officers stated that they had been better prepared for the conflict situation by their private martial arts background than through the use of mandatory training programs. While national and international data already pointed to issues of problematic content as likely causes for the disintegration between training and the field (Jager et al., 2013; Renden, et al., 2015a), pedagogical issues came into focus only recently (Staller et al., 2021b; Koerner, 2021).

In conclusion, the findings of this study support the need for future research on 1) issues related to the qualitative specifics of conflict situations in police operations, as well as on 2) the functionality of police training, especially in Germany, where related research is scarce (Koerner, 2021). In this regard, the following aspects call for more scientific attention:

1) First, in order to broaden the scope on conflict situations a continuous analysis on a micro-level of police-citizen interaction is needed, specifically with regard to the question of how exactly violence arises and under what conditions it develops or is avoided. Statistical data available in Germany do not provide any information about this. For this purpose and in order to circumvent biases of perspectivity, as caused by interview-studies like the paper on hand, in-depth analysis of video data (Koen and Mathna 2019; Longridge et al., 2020) seems to be a fruitful avenue for more (and different) objective (but still perspective-driven) data.

2) Second, data on qualitative specifics of conflict dynamics is of high importance, especially for police training, which is, one way or another, based on knowledge about “the field”. The more empirical knowledge on qualitative specifics of conflict situations we have, the more systematically evidence-based (Bennell et al., 2021) and functional in terms of its purpose the police training and police trainer education could be.

3) Third, data gathered here and elsewhere (Jager et al., 2013; Renden et al., 2015a; Boulton and Cole 2016; Preddy et al., 2019) clearly indicate a nonlinear nature of real-world conflict dynamics. This in turn calls for a reflection on whether the existing predominantly linear police training in Germany based on techniques and emphasising isolated exercises out of context (Staller et al., 2021a) can meet the demands displayed in front-line policing. In contemporary police training settings in Germany, firearms training, self-defence training and tactical training are offered in a separate manner (Staller et al., 2021b) following a linear fashion of delivery. While such training models have previously been problematized and are related to questions of effective coaching in police training in general (Cushion 2020, Cushion, 2021; Koerner and Staller 2018), current questions concerning the optimization of German police training revolve partly around how police training could be delivered more effectively. As such, paradigmatic alternatives emphasising nonlinearity in training (Koerner and Staller 2020a) have to be explored. Training that is designed according to principles of nonlinear pedagogy for instance allows officers to pick up relevant information similar to those in the field (e.g., those that would otherwise induce the element of surprise), in turn allowing them to make decisions in training as they will have to make in the field 1 day; as well as to act in training as they will have to act in the field 1 day. As such, the nonlinear approach to police training heavily relies on knowledge about qualitative interactional data of front-line policing. The effects of these data-driven pedagogical approaches in general have to be empirically evaluated (Koerner et al., 2020b).

4) Fourth, the impact of biographical backgrounds on professional performance in police operation and its training deserves more scientific attention. How does a background like being socialised in martial arts impact the thinking or the actions taken on several levels of police work (operation, training, organisational decision-making)?

5) Fifth, all requirements and future perspectives mentioned here lead up to the point that German police organisations are well-advised to continuously revise their educational structure and knowledge base, as well as to create a certain mindset and a procedure of second order observation on all levels: As we train, what are the guiding assumptions of content and design? On which knowledge is the practice based? The same reflexive mechanism applies to necessary organisational reform, e.g. comprising changes in the curriculum in terms of content and pedagogical approaches. Research can help to base decisions on all levels on the best current available evidence (Bennell et al., 2021), as well as enable their reflection. Thus, methodically controlled organisational knowledge is key for the further professionalisation and empowerment of police operation and police training in Germany (Koerner et al., 2021b).

Limitations

Whilst interview-based case studies serve the purpose of exploring so far untouched fields of interest and allow for an in-depth reconstruction of subjective experiences and views, the validity of the results is subject to important limitations on different levels. First, on an epistemological level, expert-interviews deliver ex-post narratives on the issue at hand containing personal experiences, views and attitudes (Smith 1992). As such, they depict neither an accurate portrayal of real-world violent encounters nor of police training. Instead, interview data are subject to perspectivity in three ways: They are 1) perspectively biased due to the officer’s selection of content, 2) perspectively biased due to his or her retrospective narration, and 3) perspectively biased due to the analysis and interpretation of the researchers. In this way, they are re-constructions. Second, on a methodological level, as an instrument of qualitative research expert interviews have their strength in delivering insights from subjective perspectives and interpretations of a chosen sample (Flick, 2018). As such, the qualitative data gathered in this study does not provide any representative information. General statements or conclusions regarding qualitative specifics of conflict situations or the (dys-)function of police training lay beyond the scope of this study. The results have their meaning and value within the sample and within the issues of concern. In this respect, the study`s results are explorative in nature, context-specific and must be critically reflected upon in terms of their scope. Provided there is a willingness within police authorities to be further open to research, future studies have to provide further insights on qualitative aspects of violent conflicts and related aspects of preparatory training.

Conclusion

For Germany, annual reports of the German Federal Criminal Police Office provide important empirical data which shed light upon the prevalence of violence against police officers. More specifically, the quantitative data allow for the assessment of longitudinal trends, as well as for changes in the focus of single types of offences. However, information on qualitative aspects of violent conflicts as experienced in policing remains vague. Also, geared towards the German situation, there is poor empirical evidence on the question whether police trainings serves as an integrative mechanism between training and the field, and if it does, then the question of how much of an asset it really is, remains (Staller et al., 2021a; Koerner, 2021).

In this study, 1) experts’ views on qualitative specifics of conflict dynamics during their field work and 2) the extent to which police training had prepared them to meet the respective demands have been explored. Concerning the quality of the reported violent encounters, German federal police officers perceived them as complex, dynamic and ambiguous in nature. In order to cope with these demands, police officers reported that they needed awareness for situational cues that are relevant for the interaction at-hand, as well as fast decision-making and sound interaction skills ranging from de-escalation to hands-on-fighting skills. Concerning the preparation, the majority of police officers reported that police training did not provide adequate preparation, thereby pointing towards problems concerning the content of training (focus on technique), its representativeness (lack of realism) and its delivery and testing methods (linear approach).

While we acknowledge the subjectivity of the police officers’ reports (and our analysis), in turn leading to biases in perspectivity, we identify this perspectivity as a major problem that has to be addressed by implementing structural mechanisms that provide police training with a solid and methodically controlled knowledge base in the field of situational parameters of violent encounters. In our view, a solid and continuous growing knowledge on qualitative aspects of violent encounters as well as corresponding procedures of systematic data collection and evaluation are an urgent task and challenge for the further professionalization of contemporary police training in Germany.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article can be requested from the authors.

Ethics Statement

The study has been approved by the German Sport University Cologne, Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SK and MS equally contributed to the current study and the final manuscript. The study was designed by SK and MS. Data was collected and analyzed by SK and MS. SK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MS revised the draft and helped to reach the manuscript its final form.

Conflict of Interest

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor is currently organizing a Research Topic with one of the authors SK and MS.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham, A., Collins, D., and Martindale, R. (2006). The Coaching Schematic: Validation through Expert Coach Consensus. J. Sports Sci. 24 (Nr. 6), 549–564. doi:10.1080/02640410500189173

Alpert, G. P., Dunham, R. G., and MacDonald, J. M. (2004). Interactive Police-Citizen Encounters that Result in Force. Police Q. 7 (Nr. 4), 475–488. doi:10.1177/1098611103260507

Baldwin, S., Bennell, C., Andersen, J. P., Semple, T., and Jenkins, B. (2019). Stress-Activity Mapping: Physiological Responses during General Duty Police Encounters. Front. Psychol. 10, 2216. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02216

Bennell, C., Alpert, G., Andersen, J. P., Arpaia, J., Huhta, J. M., Kahn, K. B., et al. (2021). Advancing Police Use of Force Research and Practice: Urgent Issues and Prospects. Leg. Crim Psychol. 26, 121–144. doi:10.1111/lcrp.12191

Biddle, S. J., Markland, D., Gilbourne, D., Chatzisarantis, N. L., and Sparkes, A. C. 2001. Research Methods in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Quantitative and Qualitative Issues. J. Sports Sci. 19, Nr. 10: 777–809. doi:10.1080/026404101317015438

Bogner, A., and Menz, W. 2005. Das Theoriegenerierende Experteninterview – Erkenntnisinteresse, Wissensformen, Interaktion. In: Das Experteninterview - Theorie, Methode, Anwendung, ed. by A. Bogner, B. Littig, and W. Menz, 33–70. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Boulton, L., and Cole, J. 2016. Adaptive Flexibility. J. Cogn. Eng. Decis. Making 10, Nr. 3: 291–308. doi:10.1177/1555343416646684

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, Nr. 2: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bundeskriminalamt (2015). Bundeslagebild Gewalt gegen PBV. Avialable at: http://www.heute.de/ZDF/zdfportal/blob/46503134/1/data.pdf.

Buss, A. H., and Arnold, H. 1961. The Psychology of Aggression. New York, NY: Wiley. doi:10.1037/11160-000

Chapman, U. S. Department of Justice (2019). Body-Worn Cameras: What the Evidence Tells Us, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Brett. NIJ J. 280 (7. January), 1–5.

Collins, R. (2009). The Micro-sociology of Violence. Br. J. Sociol. 60 (Nr. 3), 566–576. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01256.x

Cushion, C. J. (2020). Exploring the Delivery of Officer Safety Training: A Case Study. Policing: A J. Pol. Pract. 5 (Nr. 4), 1–15. doi:10.1093/police/pax095

Derin, B., and Singelnstein, T. (2019). "Amtliche Kriminalstatistiken als Datenbasis in der Empirischen Polizeiforschung (Official Crime Statistics as a Data Basis in Empirical Police Research)," in Polizei und Gesellschaft-Transdisziplinäre Perspektiven zu Methoden, Theorie und Empirie reflexiver Polizeiforschung. Editors C. Howe, and L. Ostermeier (Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 207–203. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-22382-3_9

Dai, M., Frank, J., and Sun, I. (2011). Procedural justice during Police-Citizen Encounters: The Effects of Process-Based Policing on Citizen Compliance and Demeanor. J. Criminal Justice 39 (Nr. 2), 159–168. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.01.004

Ellrich, Karoline, Baier, Dirk., and baier, (2014). Gewalt gegen niedersächsische Beamtinnen und Beamte aus dem Einsatz- und Streifendienst. Avialble at: https://kfn.de/wp-content/uploads/Forschungsberichte/FB_123.pdf.

Ellrich, K., and Baier, D. (2021). Gewalt gegen die Polizei-Befunde und Interpretationen (Violence against police). Duestches Polizeiblatt), 16–21.

Ellrich, Karoline, Baier, Dirk, and Pfeiffer, Christian. (2011). Gewalt gegen Polizeibeamte. Befunde zu Einsatzbeamten, Situationsmerkmalen und Folgen von Gewaltübergriffen [Violence against police officers. Findings on officers, situational characteristics and consequences of violent assaults]. Hannover: Kriminologisches Forschungsinstitut Niedersachsen e.V. Avialble at: https://www.gdp.de/gdp/gdp.nsf/id/kfn_gewalt/$file/Zwischenbericht3.pdf.

Flick, U. (2018). Managing Quality in Qualitative Research. London; Los Angeles: Sage. Managing Quality in Qualitative Research. doi:10.4135/9781529716641

Francis, J. J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M. P., et al. (2010). What Is an Adequate Sample Size? Operationalising Data Saturation for Theory-Based Interview Studies. Psychol. Health 25 (Nr. 10), 1229–1245. doi:10.1080/08870440903194015

Frenkel, Marie. Ottilie., Giessing, Laura., Jaspaert, Emma., and Mario, S. (2021). Mapping Demands: How to Prepare Police Officers to Cope with Pandemic-specific Stressors, 21. Bietlod, Belgium: European Law Enforcement Research Bulletin. https://www.cepol.europa.eu/sites/default/file/CEPOL_European_Law_Enforcement_Research_Bulletin_Issue_21.pdf.

Giessing, L., Oudejans, R. R. D., Hutter, V., Plessner, H., Strahler, J., and Frenkel, M. O. (2020). Acute and Chronic Stress in Daily Police Service: A Three-Week N-Of-1 Study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 122, 104865. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.104865

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., and Lundman, B. (2017). Britt-marie Lindgren and Berit LundmanMethodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper. Nurse Edu. Today 56, 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Groves, C. L., and Anderson, C. A. (2018). Aversive Events and Aggression. Curr. Opin. Psycholmotiv. Emotion171993 19 (1. February), 144–148. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.027

Jager, Janine., Klatt, Thimna., and Bliesener, Thomas. (2013). Gewalt gegen Polizeibeamtinnen und Polizeibeamte. Avialble at: https://www.polizei.nrw.de/media/Dokumente/131202_NRW_Studie_Gewalt_gegen_PVB_Abschlussbericht.pdf.

Jenkins, B., Semple, T., and Bennell, C. (2020a). An Evidence-Based Approach to Critical Incident Scenario Development. Policing: Int. J. ahead-of-print 44, 437–454. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-02-2020-0017

Jenkins, B., Semple, T., and Bennell, C. (2020b). An Evidence-Based Approach to Critical Incident Scenario Development. Policing: Int. J. ahead-of-print 44, 437–454. doi:10.1108/PIJPSM-02-2020-0017

Koen, M., and Mathna, B. (2019). Body-Worn Cameras and Internal Accountability at a Police Agency. Am. J. Qual. Res 3 (Nr. 2), 1–22. doi:10.29333/ajqr/6363

Koerner, S., and Staller, M. S. (2020a). Police Training Revisited-Meeting the Demands of Conflict Training in Police with an Alternative Pedagogical Approach. Policing: A J. Pol. Pract. 15, 927–938. doi:10.1093/police/paaa080

Koerner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, (2021). From Data to Knowledge: Training of Police and Military Special Operations Forces in Systemic Perspective. Spec. Operations J. 7 (Nr. 1), 29–42. doi:10.1080/23296151.2021.1904571

Koerner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, A. (2020b). "There Must Be an Ideal solution…"Assessing Training Methods of Knife Defense Performance of Police recruits” Assessing Training Methods of Knife Defense Performance of Police Recruits, Pijpsm, 44. Nr, 483–497. ahead-of-print. doi:10.1108/pijpsm-08-2020-0138

Koerner, Swen. (2021). Nonlinear Pedagogy in Police Self-Defence Training: Concept and Application. Doctoral Thesis. Freiburg: Pädagogische Hochschule Freiburg.

Kuckartz, Udo. (2014). Concluding Remarks. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods. Pract. Using Softw., 159–160. doi:10.4135/9781446288719.n7

Lansford, J. E. (2018). Development of Aggression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 19 (1. February), 17–21. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.015

Lee, Cynthia. 2021. Officer-Created Jeopardy: Broadening the Time Frame for Assessing a Police Officer’s Use of Deadly Force. George Wash. L. Rev. 89, Nr. 6: 101–190.

Longridge, R., Chapman, B., Bennell, C., Clarke, D. D., and Keatley, D. (2020). Behaviour Sequence Analysis of Police Body-Worn Camera Footage. J. Police Crim Psych, 1–8. doi:10.1007/s11896-020-09393-z