- 1Department of Training Pedagogy and Martial Research, German Sport University Cologne, Cologne, Germany

- 2Department of Police, University of Applied Sciences for Police and Public Administration North Rhine-Westphalia, Aachen, Germany

The individual views and attitudes of trainers responsible for equipping police officers for operational demands have rarely been subject to international research. Geared toward the German situation, the following case study focuses on the particular question of how police trainers at a German state police training site perceive police recruits as the target group of their coaching. The data set consisted of n = 8 interviews with police trainers who were originally conducted with the aim to investigate their expert opinions on pedagogical, training-related issues. Within the process of inductive coding, the perceived recruit condition emerged as a high-order theme, displaying a predominantly deficit-oriented view among police trainers. The findings are discussed through the lens of the concept of critically reflective practice, in which the reflection of the views and guiding assumptions of the police trainers is seen as a key ingredient for a further professionalization of the police trainer education and its respective research.

Introduction

For police training, institutionalized within police organizations around the world, police trainers play a decisive role (Staller, 2021). Their role-specific actions are supposed to prepare police officers for the complex demands of front-line policing (Birzer and Ronald, 2001; Blumberg et al., 2019). While police training has recently attracted a remarkable amount of scientific attention (Birzer and Ronald, 2001; Andersen et al., 2015; Renden et al., 2015; Nota, 2019; Mcneeley and Donley, 2020; Bennell et al., 2021), the pedagogy of police training, the role of police trainers, and more specifically their views on police training and related pedagogical issues have received only marginal attention so far (Cushion, 2020; Koerner, 2021; Staller, 2021).

Staller, et al. (2021a) investigated sources and types of knowledge of 163 police trainers from Germany and Austria, identifying a perceived need for pedagogical knowledge and a preference for nonformal and informal sources of knowledge acquisition. For the United States, Preddy et al. (2020) have examined the views of 317 police trainers on cognitive readiness in the context of violent police-citizen interactions. Data indicate a perceived lack between the capabilities and operational demands of the officers during violent encounters.

In the course of engaging with data from an interview study with police trainers in Germany, which was originally aimed at exploring pedagogical issues of training through the lenses of the persons in charge, using an open methodological approach (Körner et al., 2019), the analysis revealed an unexpected thematic focus on the perceived condition of police recruits: Within the reconstructed perceptions of the trainers, a deficit-oriented view on learners emerged, which was in turn comprised of the categories of “social,” “psychological,” and “physical” aspects. In addition, the views of the trainers on female recruits revealed a gender bias.

Based on this unexpected thematic focus in the existing data set, we present the results as they relate to the perceived condition of police recruits in more detail. We then discuss these within the broader framework of the critically reflective practice of Brookfield (Brookfield, 1998, Brookfield, 2017), arguing for the decisive role of police trainers and their views play within the context of a further professionalization of police training as an institution of professional teaching and learning. Due to their specific origin, we start by outlining the methodological context from which said findings on the perception of the trainer of police recruits emerged.

Materials and Methods

Method Selection

Similar to the international situation (Basham, 2014; Cushion, 2020; Preddy et al., 2020), the research on German police training using the perspective of pedagogical issues is still in its infancy (Koerner, 2021; Staller, 2021). Methodologically, for the purpose of exploring and mapping presumably important issues of a given field of interest, qualitative research has proven functionality (Flick, 2018), delivering insights form subjective perspectives and interpretations. In our case and due to the initial access to police trainers at a central state police training-site, semi-structured expert interviews have been conducted (Bogner et al., 2014) to serve the aim of qualitative exploration. Since experts are associated with professional role play and (are said to) possess “technical, process and interpretative knowledge that relates to his or her specific professional or occupational field of action” (Bogner and Menz, 2005, p. 46), police trainers represent a valuable knowledge resource for the exploration of central aspects in the field of police training. For the case study, two preliminary guiding assumptions were made: First, as an institutionalized teaching and learning setting, police training is of pedagogical relevance (Cushion, 2020). Second, within this setting and its function, the role and views of trainers form the basis for the exploration of this specific field of interest (Preddy et al., 2020).

Data Collection

Due to the initial character of our research, along with organizational matters (time available during duty), the sample size was determined by accessibility rather than by information power (Malterud et al., 2016). A total of eight police trainers (m = 7; f = 1) teaching police recruits within the bachelor degree program at a central training site of a German state police had been interviewed. The number of interviewed police trainers represented the total of police trainers we were granted access to. Based on the strong dialogue developed by the researchers with the police trainers, it was deemed that a small sample size would hold sufficient information power (Guest et al., 2006). Taking into account the fact that police training in Germany has hardly any connections to scientific research yet, as well as the fact that there is a documented skepticism in police to take part in scientific studies (Jasch, 2019), the sample size was deemed satisfactory.

The trainers had a mean age of 39 (SD = 5.95) and an average of 7 years (SD = 3.45) of experience as a trainer. The interview guide was comprised of 24 questions, aiming to gather biographical background data on the police trainers, as well as to create an opportunity for them to provide information about different aspects of training, e.g., with regard to their favorite methods of delivery, including instruction and feedback, or their understanding of their own role as police trainers. The semi-structured regime ensured orientation along the topical domains, at the same time enabling flexible follow-ups and probes of the interviewer to statements of the police officers. The interviews lasted between 35 and 65 min. Informed consent was obtained from all trainers before each interview. The interviews were conducted in German, audio-recorded, and subsequently transcribed verbatim (Kuckartz, 2014). For the purpose of publication, quoted passages were translated to English.

Data Analysis

In order to support scientific rigor and credibility of the findings (Tracy, 2010), the data analysis followed procedures of qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Graneheim, 2017) utilizing MAXQDA software (Kuckartz, 2014). The analytical strategy was chosen according to the objectives of the study. Due to the rather open approach to the field of interest, which served as a first qualitative exploration of pedagogically relevant aspects of police training from the perspective of trainers, the data-set was subjected to a data-driven, inductive thematic coding (Biddle et al., 2001; Graneheim, 2017), allowing for emergent information and had been “irritation through data.” Inductively, meaning units relevant to the topical issue were identified and assigned to further (sub-) themes (Biddle et al., 2001; Braun and Clarke, 2006; Graneheim, 2017).

Within the inductive coding strategy, the database had been analyzed and clustered into raw-data, lower-order, and higher-order themes. Raw-data themes were derived from the coding of relevant meaning units within the database. Identity in focal meaning (e.g., “basic coordination is not present,” police officer 01/“You can’t challenge them anymore, so coordination, for example gymnastic elements,” police officer 06) led to the creation of raw-data themes comprising the generalized meaning (e.g., “lack of coordinative skills”) allowing for the further subsumption of similar units under the existing theme, while the difference in meaning led to the creation of a new theme (e.g., “lack of motivation,” derived from “people are not motivated,” police officer 05). The coding guide created after a first coding pass of the whole data set was applied to the entire dataset in a second pass in order to ensure complete analysis.

In a next step, raw-data themes were coherently built-up into lower-order themes by generalization of their focal meaning (e.g., “lack of coordinative skills” to “physical deficiency” due to its physical nature). The set of lower-order themes had been re-examined by the second author and consented between both researchers using question and debate (Abraham et al., 2006). Subsequently, the sub-themes were generalized on a further abstraction level of meaning and built-up to higher-order themes (e.g., “physical deficiency” and “psychological deficiency” to “deficit” due to their difference in mode but similarity in being deficit oriented). High-order themes were again critically evaluated by the second author and finally set.

At the level of raw-data, the themes were quantitatively numbered according to the frequency of their mentioning by single participants, respectively, according to the overall prevalence of meaning units at the level of lower-and higher-order theme. Although “the ‘keyness’ of a theme is not necessarily dependent on quantifiable measures” (Braun and Clarke, 2006, p. 82), the number of mentions is key in those cases, in that it “captures something important in relation to the overall research question” (ibid.).

Results

When asked to examine 1) what they as police trainers like and like less about police training and 2) which situations in training they perceive as pleasant or as difficult, issues related to the recipients (n = 31 meaning units) of the training gathered by far the greatest number of thematic appearances, even more than the problematic issues of resources (n = 16 meaning units) and working conditions (n = 7). Interestingly, 27 out of the 31 meaning units were grouped around the deficient constitution of police recruits. In view of this dominance of deficit aspects, we reinvestigated the entire data set looking for meaning units referring to the condition of police recruits.

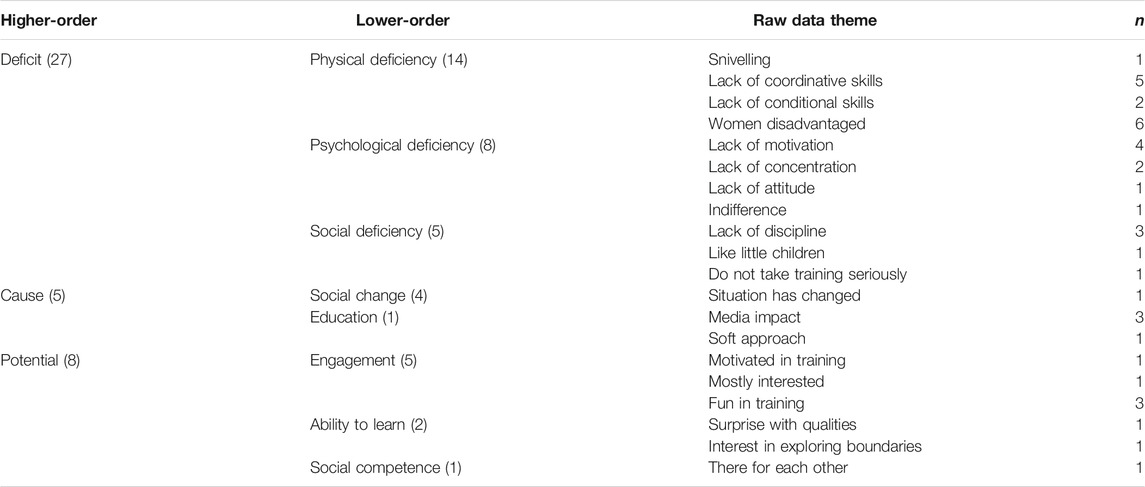

Three higher-order themes emerged from the data analysis that are presented in Table 1: 1) deficits of police recruits, 2) causes for perceived deficits, and 3) potential of police recruits.

TABLE 1. The perception of the police trainers of the condition of the police recruits (numbers in column after raw-data theme denote number of participants contributing to the raw-data theme; within lower-order and higher-order theme, numbers in brackets denote the total number of meaning units).

In the perception of trainers, the engagement, learning ability, and social competence of the recruits denote their potential. As a higher-order theme, however, the potential of recruits (n = 8) appears in qualitatively significantly lower differentiation and quantitative expression within the interview data compared with the deficit theme (n = 27).

While the view of the coaches on police recruits seems to be less associated with their potential, their deficits dominate the perception of their trainers. Within this complex, physical deficiency represents the largest thematic unit, mainly seen in a lack of coordination and condition/fitness in police recruits. As one police trainer puts it:

Or take the area of self-defense, coordinative things, of course injuries often occur here because this basic coordination, which one actually assumes that every police applicant should have, is actually not there. Many things are missing. Of course, that’s because you’ve never climbed anywhere in your life or done other physical things. Maybe you just sat at home in front of a computer game and tried to master something, but you didn’t/weren’t whistling through the forest, jumping from tree to tree. It has changed, you have to say that, quite clearly (I: Mh.) And then, of course, there are more and more injuries, because things that you assume should be there are not there (PT 01).

In the perception of this police trainer, contemporary recruits fail to meet the expected physical standards for police training. According to this point of view, the negative condition is caused by modern times and the according lifestyle, consisting of the use of modern media and a decline of playful natural movement in childhood, eventually leading to consequences of injury in training and the need to implement basic coordination exercises, e.g., “running backward up the stairs” (PT 01). Recruits do not have what they should have and used to have back in the days: “It has changed, … quite clearly.” This change in condition is also reported by another trainer, a prerequisite which, for instance, is making the teaching of appropriate restraint techniques challenging.

And it’s not getting better because the material is getting worse. So, I say the students (I: Ok.) You can no longer demand as much of them like that and you have to pick them up where they are. And then you have to cut back. Because you simply can’t do these exercises, for example, coordination, gymnastic elements. We always do the TKF, this hold in the floor position, but if you have no coordination and if you have no strength and no assertiveness, then even the technique is of no use (PT 06).

In the view of trainers, recruits appear as deficient modes of their ideal version. This perception is reinforced by deficits in motivation and concentration during police training, building the theme of psychological deficiency (see Table 1). The lack of motivation and attention of the recruits within the teaching process are perceived as burdensome, for instance negatively effecting the emotional state of the trainers. One police trainer states as follows:

When you notice that some of the people are not motivated, they don’t listen to you at all. You say something now and then at some point I’m also not motivated. You quickly notice my mood then (PT 05).

Additionally, and related to motivational issues, deficits in the domain of social behavior contribute to the negative complex, as it can be viewed in this statement of a police trainer:

Sometimes there’s an admonition if someone doesn’t really want to run on track. The discipline among the young colleagues is different in contrast to my training back then, basic training… We didn’t have to salute any more, that used to be the case with the police, but then there was silence. When in the frontline the announcement was made and then they all stepped away. There is a lack of discipline. I don’t know what the reason is, it may be the generations that now come to the police. Maybe it's a tougher approach, in my eyes that could be helpful, here and there (PT 03)

The lack of discipline in young trainees, which is stated here appears as a recurring theme within the data-set, and again, the deficit is compared with its better version, which once more is located in past times of a more disciplined generation of apprentices. Furthermore, in accordance with the point of view of the trainers, a sensible cause of action to deal with inappropriate social behavior would be a tougher approach to teaching and learning within police training, which might in turn fix the problem of discipline.

Additionally, within the thematic complex of the deficiency of the recruits, a gender bias emerged within the data.

Yes, and what we try to pass on to the students, who come to us completely clueless, who have never had anything to do with anything, especially the girls, who have never had anything to do with this kind of contact, is to make it clear to them that it is really important to defend oneself outside or to effectively support a colleague during an arrest (PT 08).

Female police officers are seen as “supporters” in the context of deployment, compared with their male colleagues who supposedly carry out the actual work. Labeled as “girls,” the overall condition of females and suitability for operational requirements, especially when it comes to physical confrontations, are called into question by the trainer. In this point of view, female police recruits are perceived as rather incapable and as inexperienced learners. They appear to be deficient beings with special needs that have to be met in a compensational manner through training:

Especially women, who are considered the weaker sex here or so. They cannot always hide behind it …of course they are physically disadvantaged, but eh there are simply certain things that you can train and that you also have to train. (PT 08)

According to this view, female police recruits are considered as members of the “weaker” sex within the domain of police training. Interestingly, it is not this depiction itself that is further problematized here. On the contrary, in this statement the image of a weaker sex is reinforced by referring to generalized physical disadvantages of women. Even more importantly, the statement suggests that this view appears to be a shared opinion among police trainers and police organizations, and that it is seen as an excuse for female police recruits to hide behind.

In conclusion, initial qualitative interview data led to unexpected explorative findings broadening the perspective of pedagogically relevant issues in police training. The analysis of expert views provided by police trainers at a central German training site for police recruits revealed a predominant perception of physical, psychological, and social deficiency, which is linked to changes in society as a whole, presenting pressing concerns in police training. In contrast, the potential of said students was less emphasized.

Discussion

The findings on the perceptions of the police trainers of their clientèle can be contextualized and discussed on several different levels.

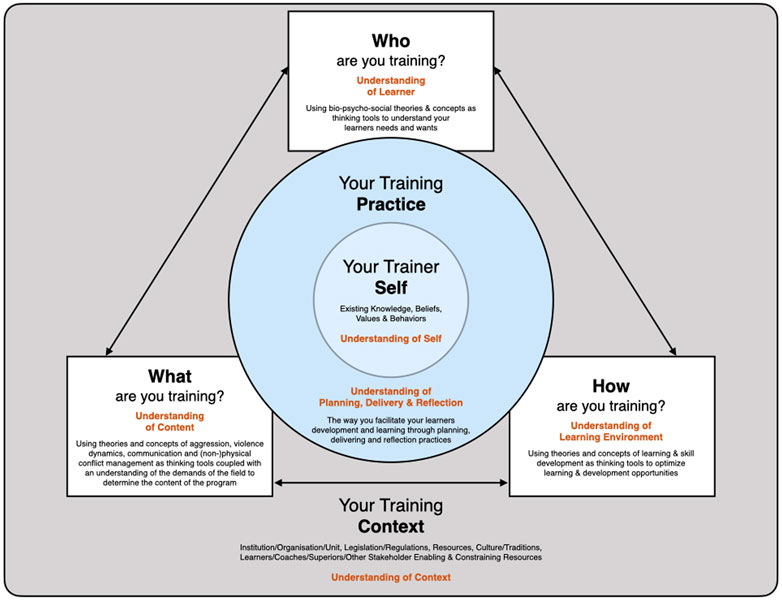

First, the deficit themes that emerged from the data could be interpreted as a more or less representative depiction of reality and objective conditions. Taking this objective approach, the deficiency of police recruits in physical, psychological, and social areas regard has to be met in training and become the subject of compensatory education (Luhmann ans Schorr, 1979a). According to this perspective, issues of appropriate teaching and the design of learning environments according to the model of professional coaching (Staller, 2021) are deemed relevant (see Figure 1). If, for instance, police recruits lack the ability of running up stairs backward, or to perform mandatory restraint techniques (see quote above), structured coordination exercises and fitness programs must be implemented in training as compensatory measures for the creation of a motor-related baseline to work with (Blumberg et al., 2019). In a similar vein, compensatory attention and education must then be given to female police recruits because of their “physical disadvantages.”

FIGURE 1. Professional coaching model (Staller, 2021).

According to the model in Figure 1, problematic and heterogeneous prerequisites within the learners (Who-Dimension) affect and determine the selection of contents (What-Dimension) that meet the demands of the learners. Furthermore, deficits in motor skills, motivation, or discipline also have an influence on the decisions of the trainers on how to teach (How-Dimension). For instance, heterogeneity of physical pre-conditions in the learning group may call for the within-differentiation of exercises along with individualized instruction and feedback strategies, as applied in physical education (Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2018). Moreover, disciplinary problems as perceived by the trainers may raise the question of whether more (or less) authority (Omer et al., 2010), and which kind of authority (Reichenbach, 2009) within the personal teaching style, is appropriate and serves as a possible solution (or as the problem). Within the objective approach, general recruits’ as well as specific gender-based deficits are taken for granted. They are perceived as entities at hand, and as such, they call for action.

Second, the deficit themes that emerged from the data could be observed through the lenses of pedagogical paradigms. In this conceptual approach, the pre-dominant orientation toward deficits could be confronted by implementing an alternative: a pedagogy of potential. In this perspective, declarative knowledge as well as the ability to distance oneself from one’s views is the basic prerequisite trainers have to fulfil. The practice and reflection on education is historically grounded in a semantic of human deficits (Luhmann and Schorr, 1979b; Valencia, 1997), especially within the history of physical education (Koerner, 2020). Pedagogical endeavors, even nowadays, do not seldom start with the deficit premise—that something is not yet as it should be (Paschen, 1973, 1988). If children do not partake in enough physical activity (Finger and Lange, 2018), the resulting deficits should be resolved, for instance through physical education (Koerner, 2008a).

However, the traditional pedagogical premise of deficits is neither without alternatives nor unchallenged. Looking at learners in a different way, the pedagogy of potential turns the perspective around (Oelkers, 2001). In large parts of modern pedagogy, a potential-oriented view has prevailed, even when the initial conditions deviate from a socially constructed normality, as is the case in the field of special needs education (Kozulin, 2015). At the same time, this orientation toward potential is by no means exclusively the expression of normative hopes that miss the mark.

The call for potential is empirically supported. On the one hand, learners are inherently endowed with a broad range of hard-wired potential. These are for example grounded in neurobiological degeneracy (Orth et al., 2019), allowing to yield the same goal and output in different behavioral ways. In the area of movement coordination, learners have an incredible number of degrees of freedom at their disposal when it comes to the use of joints and muscles in a targeted manner (Schoellhorn et al., 2012). On a social level, concerning the German situation, it is evident that never before have so many people been engaged in organized sports (DOSB, 2020). In addition, the area of informal sport culture, popular especially with younger people, has grown remarkably in recent decades (Gugutzer, 2004). So, it may be true that nowadays more people, and even police recruits, have not “jumped from trees” (see quote above) as much as their predecessors did in their childhood days, but as a matter of fact, the new generation does different things differently—what can be viewed either as deficit or as a potential. On the other hand, pedagogical research indicates that deficit-oriented views on learners, as well as certain pedagogical practices, can both lead to negative consequences (García and Guerra, 2016; Smit, 2012; Valencia, 1997).

The orientation toward either deficits or potential is a crucial part of the professional action and reflection of a trainer. The respective conceptualization of the learners is a difference that makes a difference: a difference in view, a difference in the chosen course of action, and eventually, a difference in outcome (Koerner, 2008b). If two police trainers are teaching the same recruit, depending on their pedagogical orientation, they are likely to set a different focus of attention and are likely to evaluate the observed aspects in different ways. For the potential view, this may include the opportunity to evaluate deficits, e.g., in motor performance or discipline, as a potential for personal growth and development. The question of basic pedagogical attitudes is paradigmatic, referring to the dimension of self-reflection within the model of professional coaching (Dimension of Trainer-Self). The self-dimension advocates for the reflection of the very premises that underpin the model of the learner and the learning process of a trainer (Chow et al., 2016). This leads to a additional view on the empirical findings.

Third, the deficit themes that emerged from the data could be interpreted through the lenses of subjective theories. Subjective theories refer to implicit and explicit beliefs about the world, including its people (Nespor, 1987). As filters of perception (Weinstein, 1990), subjective theories are of high functionality for the reduction of real-world complexity, which serves as a premise for dealing with it: They structure the relationships of the subject to the world by shaping his or her perception and interpretation of situations and persons (Borko and Putnam, 1996). As school research has shown, subjective theories act as key agents of teachers’ professional actions (Baumert and Kunter, 2013; Mandl and Huber, 1983). Empirical data indicate that subjective theories about the subject as well as the learners affect the actions of the teachers and, thus, also indirectly the learning process of the students. They are of considerable significance for lesson planning (Bromme, 1986), control the perception of teaching processes, especially of critical teaching situations (Wahl, 1981), and have substantial effects on classroom management (Stipek et al., 2001).

In line with scientific theories, subjective theories serve to predict, explain, justify, and evaluate one’s own as well as the actions of others. In contrast to scientific theories, subjective theories do not have to meet scientific criteria (Eynde et al., 2002). They are rather the result of socialization (Calderhead and Robson, 1991) than of methodically controlled observations. Being foremost derived from one’s own learning biography in school as well as other learning institutions, subjective theories are believed to be true (Nespor, 1987) and resistant to change (Lasley and Thomas, 1980). As such, subjective theories mostly contain implicit assumptions (Mandl and Huber, 1983) that in a professional scientific manner need to be acknowledged as the axioms of the trainer-self, guiding his or her practice of planning, delivery, and evaluation of training (see Figure 1).

In terms of professional trainer action, subjective theories and their underlying assumptions have to be aligned with scientific knowledge and corrected if necessary. Within the framework of subjective theories, the perceived deficits of police recruits are not taken for granted, as is the case in the objective approach. Rather, the views of the trainers are analyzed by referring to the underlying assumptions that (may) guide those views. By doing so, subjective theories literally call for a reflective turn within the professional action of police trainers.

In summary, all three approaches are based on declarative knowledge structures. The objective approach requires solution-knowledge since the perceived problem itself is not problematized, but set. If recruits show physical deficiencies, structured fitness exercises are needed for compensation. The approaches of conceptual orientation and subjective theories call for higher-order declarative knowledge. Both perspectives do not start from the object of perception, but focus on perception itself and relate it to its guiding premises and assumptions (Brookfield, 2017). The pedagogy of potential makes different assumptions about the learner and the learning process than deficit-orientation does. Additionally, both approaches contain different expectations on delivery and outcome: Whereas deficit-orientation leads to a practice of compensation, potential-orientation leads to a practice of growth and development in police training.

The approach of subjective theories starts at an even more fundamental level and investigates all the assumptions that guide the actions of the trainer. This is analogous to our recent proposal for reflective policing (Staller et al., 2021b), in which we introduced the uncovering of individual paradigmatic, prescriptive and causal assumptions as a part of professionalism based on Brookfield’s critically reflective practice (Brookfield, 2013). The conceptual, as well as the approach of subjective theories, are both components of a reflective practice of trainer action. The reflective practice focuses on action and reflects on their consequences (future direction) and premises (past direction). Thereby, reflective practice is based on the assumption that—analogous to findings in school research (Hattie, 2011)—in police training, the trainer matters, including his or her views on the learner.

The pedagogical views, orientations, and guiding assumptions of police trainers do not exist in a vacuum. They are, among other things, embedded within a police culture (see context-dimension, Figure 1) that reproduces itself in applying them (Behr, 2006; Chapell and Lanza-Kaduce, 2010; Behr, 2017; Gutschmidt and Vera, 2020). Through a reflexive analysis of pedagogical approaches and assumptions, this cycle can be made visible and, if necessary, interrupted; especially at points where adopted perspectives contain assumptions in need of correction, for example about a supposedly weak gender (Rawski and Workman-Stark, 2018; Seidensticker, 2021).

Limitations

The validity of the results is subject to important limitations on several levels. First, from a methodical point of view, the study had only limited access to police trainers in Germany due to the cooperation with a single central training site. In this respect, the results of the study are explorative in nature, context-specific and must be critically reflected upon in terms of their scope. Provided there is a willingness within police authorities to further open up police training to pedagogical research, future studies at other training sites across the country will have to provide further insights on police trainers perception on their recruits. Second, while research on subjective theories of teacher action in particular suggests that these influence classroom action in many ways, the findings of this study do not allow this causal conclusion and transfer to police trainers. The views and attitudes of police trainers were re-constructed selectively, but not their influence on the practical level of coaching. The latter issue requires further studies as well as alternative methodological approaches, such as training observations (Cushion, 2020). Third, limitations on an epistemological level have to be acknowledged. Although qualitative research in general and expert interviews especially have their strength in delivering insights form subjective perspectives and interpretations (Flick, 2018), the qualitative data are subject to perspectivity and bias due to the retrospective narration by the police trainers and the analysis and interpretation of the researchers. In this way, they are re-constructions.

Conclusion

Pedagogical issues of police training have rarely been the subject of international and national research yet. Police trainers, as the agents in charge of police training, are offering a relevant access to this special field of interest. In the context of our explorative interview study on the German police trainer’s expert views on pedagogical implications of their training, a predominantly deficit-oriented perception of police recruits occurred as a rather random finding. When asked about different aspects of the training, the interviewed trainers reported a deficiency of their clientèle within the realms of physical fitness, motivation and discipline.

In this article, it has been argued that this view, in particular, as well as the trainers’ perception, in general, is of great importance for pedagogical research, as well as for the reflection of police training itself. Through the lenses of a professional coaching model and (critically) reflective practice, the deficit-oriented view has been discussed on different levels: 1) as an objective depiction of real conditions, which have to be effectively met in training in a compensatory manner; 2) a conceptual orientation that has a deep foundation within the history of education and can be contrasted with the alternative approach of a pedagogy of potential; and 3) as an issue relevant to the reflection of believed subjective theories, which in turn guide trainers’ actions.

Especially the approaches of conceptual orientation and subjective theories contribute to the paradigm of reflective practice in police training. They refocus the process of reflection back on the generating mechanism of the point of view of the trainer, and advocate for analytical deliberations on the underlying premises and assumptions. By doing so, they make an important contribution to elucidating the police culture that forms the breeding ground of those action-guiding assumptions and practically reproduces itself through it.

Although the key finding of a deficit orientation in German police trainers regarding police recruits has to be considered as limited due to the small sample size, it stresses the relevance for further research on the role of police trainers and their perceptions of training. In view of the hypothetical impact within the context of practical police training, further insights into the spread and impact of objective views, conceptual orientations, subjective theories and their underlying assumptions are of great interest for future research.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The study has been approved by the German Sport University Cologne, Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

SK and MS equally contributed to the current study and the final manuscript. The study was designed by SK and MS. The data were collected by SK and analyzed by SK and MS. SK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MS revised the draft and helped to reach the manuscript to its final form.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling editor is currently organizing a research topic with the authors.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed nor endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham, A., Collins, D., and Martindale, R. (2006). The Coaching Schematic: Validation through Expert Coach Consensus. J. Sports Sci. 24, 549–564. doi:10.1080/02640410500189173

Andersen, J. P., Papazoglou, K., Koskelainen, M., Nyman, M., Gustafsberg, H., and Arnetz, B. B. (2015). Applying Resilience Promotion Training Among Special Forces Police Officers. SAGE Open 5 (Nr. 2), 215824401559044. doi:10.1177/2158244015590446

Baumert, J., and Kunter, M. (2013). Cognitive Activation in the Mathematics Classroom and Professional Competence of teachersResults from the COACTIV Project. Springer, 25–48. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5149-5_2

Behr, R. (2006). Polizeikultur: Routinen - Rituale - Reflexionen [Police Culture: Routines - Rituals - Reflections. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-90270-8

Behr, R. (2017). “Ich bin seit dreißig Jahren dabei",” in Professionskulturen – Charakteristika Unterschiedlicher Professioneller Praxen. Editors S. Müller-Hermann, R. Becker-Lenz, S. Busse, and G. Ehlert (Springer Fachmedien), 31–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-19415-4_3

Bennell, C., Alpert, G., Andersen, J. P., Arpaia, J., Huhta, J. M., Kahn, K. B., et al. (2021). Advancing Police Use of Force Research and Practice: Urgent Issues and Prospects. Leg. Crim Psychol. 26, 121–144. doi:10.1111/lcrp.12191

Biddle, S. J., Markland, D., Gilbourne, D., Chatzisarantis, N. L., and Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Research Methods in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Quantitative and Qualitative Issues. J. Sports Sci. 19 (Nr. 10), 777–809. doi:10.1080/026404101317015438

Birzer, M. L., and Tannehill, R. (2001). A More Effective Training Approach for Contemporary Policing. Police Q. 4 (Nr. 2), 233–252. doi:10.1177/109861101129197815

Blumberg, D. M., Schlosser, M. D., Papazoglou, K., Creighton, S., and Kaye, C. C. (2019). New Directions in Police Academy Training: A Call to Action. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 (Nr. 24), 4941. doi:10.3390/ijerph16244941

Bogner, A., and Menz, W. (2005). Das Theoriegenerierende Experteninterview – Erkenntnisinteresse, Wissensformen, Interaktion. in ” Das Experteninterview - Theorie, Methode, Anwendung, Editors A. Bogner, B. Littig, and W. Menz, 33–70. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

Bogner, A., Littig, B., and Menz, W. (2014). Interviews mit Experten, Eine praxisorientierte Einführung Interviews with experts. A practical orientation. Frankfurt, Germany: Springer, 71–86. doi:10.1007/978-3-531-19416-510.1007/978-3-658-08349-6_6

Borko, H., and Putnam, R. (1996). Learning to Teach. In: Handbook of Educational Psychology, Editors D. Berliner, and R. Calfee, 673–708. New York: Macmillan.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (Nr. 2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bromme, R. (1986). Die alltägliche Unterrichtsvorbereitung des (Mathematik-) Lehrers im Spiegel empirischer Untersuchungen. Jmd 7 (Nr. 1), 3–22. doi:10.1007/bf03338690

Brookfield, S. (1998). Critically Reflective Practice. J. Cont. Educaiton Health Professions 18 (Nr. 4), 197–205. doi:10.1002/chp.1340180402

Brookfield, S. (2013). Teaching for Critical Thinking. Int. J. Adult Vocational Educ. Techn. (Ijavet) 4 (Nr. 1), 1–15. doi:10.4018/javet.2013010101

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-BassJossey-Bass.

Calderhead, J., and Robson, M. (1991). Images of Teaching: Student Teachers' Early Conceptions of Classroom Practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 7 (Nr. 1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/0742-051x(91)90053-r

Chappell, A. T., and Lanza-Kaduce, L. (2010). Police Academy Socialization: Understanding the Lessons Learned in a Paramilitary-Bureaucratic Organization. J. Contemp. Ethnography 39 (Nr. 2), 187–214. doi:10.1177/0891241609342230

Chow, J. Y., Davids, K., Button, C., and Renshaw, I. (2016). Nonlinear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315813042

Cushion, C. J. (2020). Exploring the Delivery of Officer Safety Training: A Case Study. Policing: A J. Pol. Pract. 5 (Nr. 4), 1–15. doi:10.1093/police/pax095

DOSB (2020). Bestandserhebnung 2019 [Survey 2019]. Frankfurt, Germany: Deutscher Olympischer Sportbund.

Eynde, P., De Corte, E., and Verschaffel, L. (2002). Framing Students' Mathematics-Related Beliefs. 13–37. doi:10.1007/0-306-47958-3_2

Finger, J. D., and Lange, C. (2018). Körperliche Aktivität von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland – Querschnittergebnisse aus KiGGS Welle 2 und Trends [Physical activity of children and adolescents in Germany - cross-sectional results from KiGGS wave 2 and trends]. J. Health Monit 3 (1), 25–31. doi:10.17886/RKI-GBE-2018-006.2

Flick, U. (2018). Managing Quality in Qualitative Research. London; Los Angeles: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781529716641

García, S. B., and Guerra., P. L. (2016), 36. Deconstructing Deficit ThinkingEducation and Urban Society, 150–168. doi:10.1177/0013124503261322

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., and Lundman, B. (2017). Britt-marie Lindgren and Berit LundmanMethodological Challenges in Qualitative Content Analysis: A Discussion Paper. Nurse Educ. Today 56, 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

Guest, G., Bunce, A., and Johnson, L. (2006). How Many Interviews Are Enough. Field Methods 18 (1), 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822x05279903

Gugutzer, R. (2004). Trendsport im Schnittfeld von Körper, Selbst und Gesellschaft. Leib- und körpersoziologische Überlegungen [Trendsport between body, self and society]. Sport & Gesellschaft 1 (Nr. 3), 219–243. doi:10.1515/sug-2004-0305

Gutschmidt, D., and Vera, A. (2020). Dimensions of Police Culture - a Quantitative Analysis. Pijpsm 43 (Nr. 6), 963–977. doi:10.1108/pijpsm-06-2020-0089,

Hattie, J. (2011). Visible Learning for Teachers. London; New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203181522

Jasch, M. (2019). “Kritische Lehre und Forschung in der Polizeiausbildung. in ”Polizei und Gesellschaft - Transdisziplinäre Perspektiven zu Methoden, Theorie und Empirie reflexiver Polizeiforschung, Editors C. Howe, and L. Ostermeier, 231–250. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-22382-3_10

Koerner, S. (2008a). Dicke Kinder - Revisited. Zur Kommunikation Juveniler Körperkrisen [Fat Children – Revisited]. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript.

Köerner, S. (2008b). In-Form durch Re-Form: Systemtheoretische Notizen zur Pädagogisierung juveniler Körperkrisen / In-form by Re-form: System Theory Reflections on the Education of Juvenile Body Crises. Sport und Gesellschaft, 2 (2), 134–152. doi:10.1515/sug-2008-0203

Koerner, S. (2020). “Zwischen Wirklichkeit und Möglichkeit: Der Körper in Erziehung und Wettkampfsport [Between reality and possibility: The Body in education and competitive sports]. in” Upgrades der Natur, künftige Körper, Interdisziplinäre und internationale Perspektiven, Editors M. Sahinol, and C. Coenen, 53–73. Technikzukünfte, Wissenschaft und Gesellschaft/Futures of Technology, Science and Society. Wiesbaden: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-31597-9_4

Koerner, S. (2021). Nonlinear Pedagogy in Police Self-Defence Training: Concept and Application. Doctoral Thesis. Pädagogische Hochschule Freiburg.

Koerner, S., Staller, M. S., and Kecke, A. (2019). “Pädagogik., hat man oder hat man nicht.“ – Zur Rolle von Pädagogik im Einsatztraining der Polizei ["Pedagogy. did you or did you Not." - The role of pedagogy in police training]. in”Lehren ist Lernen: Methoden, Inhalte und Rollenmodelle in der Didaktik des Kämpfens” : internationales Symposium; 8. Jahrestagung der dvs Kommission “Kampfkunst und Kampfsport” vom 3. an der Universität Vechta; Abstractband, Editors M. Meyer, and M. S. Staller, 13–14. Vechta: Hamburg: Deutsche Vereinigung für Sportwissenschaften (dvs)

Kozulin, A. (2015). Dynamic Assessment of Adult Learners' Logical Problem Solving: A Pilot Study with the Flags Test. J. Cogn. Educ. Psych 14 (Nr. 2), 219–230. doi:10.1891/1945-8959.14.2.219

Kuckartz, U. (2014). Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice & Using Software. London: Sage. doi:10.4135/9781446288719.n7

Lasley, T. J., and Thomas, J. (1980). Preservice Teacher Beliefs about Teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 31 (Nr. 4), 38–41. doi:10.1177/002248718003100410

Luhmann, N., and Schorr, K. E. (1979a). „Kompensatorische Erziehung" unter pädagogischer Kontrolle. Bildung und Erziehung 32, 551–570. doi:10.7788/bue-1979-jg53

Luhmann, N., and Schorr, K. E. (1979b). Reflexionsprobleme im Erziehungssystem [Reflection problems in the system of education]. Stuttgart: Schoeninghaus.

Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., and Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 26 (Nr. 13), 1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

Mandl, H., and Huber, G. L. (1983). Subjektive Theorien von Lehrern. Psychol. Erziehung, Unterricht 30, 98–112. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Heinz_Mandl/publication/301214826_Subjekive_Theorien_von_Lehreren/links/573ade6908ae9f741b2d3e5f/Subjekive-Theorien-von-Lehreren.pdf.

Mcneeley, S., and Donley, C. (2020). Crisis Intervention Team Training in a Correctional Setting: Examining Compliance, Mental Health Referrals, and Use of Force. Criminal Justice Behav. 48, 195–214. doi:10.1177/0093854820959394

Nespor, J. (1987). The Role of Beliefs in the Practice of Teaching. J. Curriculum Stud. 19 (Nr. 4), 317–328. doi:10.1080/0022027870190403

Di Nota, P. M., and Huhta, J.-M. (2019). Complex Motor Learning and Police Training: Applied, Cognitive, and Clinical Perspectives. Front. Psychol. 10, 1797. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01797

Oelkers, J. (2001). Einführung in die Theorie der Erziehung [Introduction in theory of education]. Weinheim; Basel: Beltz.

Omer, H. (2010). The New Authority: Family, School, and Community. Editors S. London Sappir, and M. Herbsman. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511974229

Orth, D., van der Kamp, J., and Button, C. (2019). Learning to Be Adaptive as a Distributed Process across the Coach-Athlete System: Situating the Coach in the Constraints-Led Approach. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 24 (Nr. 2), 146–161. doi:10.1080/17408989.2018.1557132

Paschen, H. (1973). Pädagogische Kommunikation. Bildung und Erziehung 26, 85–86. doi:10.7788/bue-1973-jg11

Paschen, H. (1988). Pädagogisches Argumentieren [Pedagogical Argumentation]. Bildung und Erziehung 41 (Nr. 4), 363–364. doi:10.7788/bue.1988.41.4.363

Preddy, J. E., Stefaniak, J. E., and Katsioloudis, P. (2020). The Convergence of Psychological Conditioning and Cognitive Readiness to Inform Training Strategies Addressing Violent Police-Public Encounters. Perf Improvement Qrtly 32 (Nr. 4), 369–400. doi:10.1002/piq.21300

Rawski, S. L., and Workman-Stark, A. L. (2018). Masculinity Contest Cultures in Policing Organizations and Recommendations for Training Interventions. J. Soc. Issues 74, 607–627. doi:10.1111/josi.12286

Reichenbach, R. (2009). “Bildung und Autorität,” in Bildung der Kontrollgesellschaft: Analyse und Kritik pädagogischer Vereinnahmungen. Editors C. Bünger, R. Mayer, A. Messerschmidt, and O. Zitzelsberger ( Paderborn, Germany: Schöningh), 71–84.

Renden, P. G., Nieuwenhuys, A., Savelsbergh, G. J., and Oudejans, R. R. (2015). Dutch Police Officers' Preparation and Performance of Their Arrest and Self-Defence Skills: a Questionnaire Study. Appl. Ergon. 49, 8–17. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2015.01.002

Ruiz-Pérez, L. M., and Palomo-Nieto, M. (2018). “Clumsiness and Motor Competence in Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy,” in Advanced Learning and Teaching Environments - Innovation, Contents and Methods. Editors N. Llevot-Calvet, and O. B. Cavero (London, United Kingdom: IntechOpen). doi:10.5772/intechopen.70832

Schollhorn, W., Hegen, P., and Davids, K. (2012). The Nonlinear Nature of Learning - A Differential Learning Approach. Tossj 5 (Nr. 1), 100–112. doi:10.2174/1875399x01205010100

Seidensticker, K. (2021). Aggressive Polizeimännlichkeit: Noch Hegemonial, Aber Neu Begründet [Aggressive Masculinity in Police. Still Hegemonic but Newly Invented], 126. Bürgerrechte & Polizei/CILIP.

Smit, R. (2012). Towards a Clearer Understanding of Student Disadvantage in Higher Education: Problematising Deficit Thinking. Higher Educ. Res. Develop. 31 (Nr. 3), 369–380. doi:10.1080/07294360.2011.634383

Staller, M. S., Körner, S., Abraham, A., and Poolton, J. (2021a). Topics, Sources and the Application of Coaching Knowledge in Police Training. Accepted; Frontiers in Education.

Staller, M. S., Koerner, S., and Zaiser, B. (2021b). “Der/die reflektierte Praktiker*in: Reflektieren als Polizist*in und Einsatztrainer*in [The Reflective Practitioner: Reflecting as a Police Officer and Police Trainer]. in” Handbuch Polizeiliches Einsatztraining: Professionelles Konfliktmanagement, Editors M. Meyer, and M. S. Staller. Wiesabaden: Springer.

Staller, M. S. (2021). Optimizing Coaching in Police TrainingDoctoral Thesis. Leeds: Leeds Beckett University.

Stipek, D. J., Givvin, K. B., Salmon, J. M., and MacGyvers, V. L. (2001). Teachers' Beliefs and Practices Related to Mathematics Instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17 (Nr. 2), 213–226. doi:10.1016/s0742-051x(00)00052-4

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative Quality: Eight "Big-Tent" Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qual. Inq. 16 (Nr. 10), 837–851. doi:10.1177/1077800410383121

Valencia, R. R. (1997). The Evolution of Deficit Thinking. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203046586

Wahl, D. (1981). “Subjektive psychologische Theorien: Möglichkeiten zur Rekonstruktion und Validierung, am Beispiel der hanldungssteuernden Kognitionen von Lehrern [Subjective psychological theories: Possibilities for reconstruction and validation, using the example of teachers' cognitions that control their actions]. in” Bericht über den 32. Kongreß der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie, Editor D. Michaelis, 625–631. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Keywords: police training, police recruits, reflective policing, subjective theories, professionalization

Citation: Koerner S and Staller MS (2022) “It has Changed, Quite Clearly.” Exploring Perceptions of German Police Trainers on Police Recruits. Front. Educ. 6:771629. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.771629

Received: 06 September 2021; Accepted: 14 December 2021;

Published: 10 February 2022.

Edited by:

Craig Bennell, Carleton University, CanadaReviewed by:

Christopher Cushion, Loughborough University, United KingdomPeter Shipley, Kinetic Defense Systems, Inc., Canada

Copyright © 2022 Koerner and Staller. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Swen Koerner, a29lcm5lckBkc2hzLWtvZWxuLmRl

Swen Koerner

Swen Koerner Mario S. Staller

Mario S. Staller