95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Educ. , 08 November 2021

Sec. Educational Psychology

Volume 6 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.769573

This article is part of the Research Topic Student-Teacher Relationship Quality Research: Past, Present and Future View all 17 articles

Anne-Katrien Koenen1

Anne-Katrien Koenen1 Liedewij Frieke Nel Borremans1*

Liedewij Frieke Nel Borremans1* Annet De Vroey2

Annet De Vroey2 Geert Kelchtermans3

Geert Kelchtermans3 Jantine Liedewij Spilt1

Jantine Liedewij Spilt1Relationships with children with special educational needs can be emotionally challenging for teachers and conflicts may negatively impact both children and teachers. Beginning teachers in particular may struggle with negative teacher-child relationships and the emotions these invoke. A first step in coping with relationship difficulties with specific children is increasing the teacher’s awareness and understanding of relational themes and emotions in the relationship with that specific child. Therefore, this multiple case intervention study examined the effects of LLInC (Leerkracht Leerling Interactie Coaching in Dutch, or: Teacher Student Interaction Coaching) in a sample of six student teachers in their final internship. LLInC is a relationship-focused coaching program using narrative interview techniques to facilitate in-depth reflection on teacher-child relationships. The intervention aims to foster teachers’ awareness of (negative) internalized emotions and beliefs in order to improve closeness and positive affect, and to reduce conflict and negative affect in teacher-child relationships. Participants repeatedly reported on their perceptions of the teacher-child relationship and on emotions in relation to a specific child before and after the LLInC intervention, which consisted of two one-on-one sessions with a coach. Visual between- and within-phases analyses revealed differential intervention effects across teachers on the development of teacher-child relationship quality and relationship emotions. For all teachers, except for one, positive effects were found on feelings of joy and perceptions of closeness. Preventive effects (i.e., stopping downward trends) were more often observed for competence-based and relationship-based emotions and perceptions (competence, commitment, closeness) than for basic emotions (joy, anger, worry). Although further research is needed, the results highlight the potential of LLInC in influencing pre-service teachers’ child-specific emotions and relationship perceptions. Directions for future research and implications for teacher education are discussed.

Relationships with children with special educational needs can be emotionally challenging for teachers (Hargreaves, 2000; Breeman et al., 2014). Conflictual relationships can negatively impact both children and teachers (McGrath and Van Bergen, 2015; Evans et al., 2019). Beginning teachers in particular may struggle with negative teacher-child relationships and the emotions these invoke (Pillen et al., 2013; Kelchtermans and Deketelaere, 2016). A first step in successfully coping with relationship difficulties with specific children is increasing teachers’ awareness and understanding of relational themes and experienced emotions in the relationship with that specific child. For this purpose, LLInC was developed (Leerkracht Leerling Interactie Coaching in Dutch, or: Teacher Student Interaction Coaching). LLInC is a coaching program for teachers that is aimed at improving teacher-child relationships. As it is necessary that teachers develop this awareness of relational themes and emotions already during their education, so that they are prepared for the relational challenges that are inherent to teaching children with special educational needs, the present study examined the effects of LLInC on teacher-child relationships in a volunteer sample of student teachers during their internship in special education schools.

The importance of positive teacher-child relationships, both for the development of children (e.g., McGrath and Van Bergen, 2015; Roorda et al., 2017) and the well-being of teachers (e.g., Zee et al., 2017; Aldrup et al., 2018; Corbin et al., 2019), is well-established. Research on teacher-child relationships has been largely guided by two frameworks, self-determination theory and the extended attachment perspective [for reviews, see Kincade et al. (2020); McGrath and Van Bergen (2015); Roorda et al. (2017)]. Self-determination theory states that three needs, the need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, have to be fulfilled in order for children to be able to truly engage in a task (Deci et al., 1991; Ryan and Deci, 2000). In this light, the teacher-child relationship has been identified as an important lever to fulfill children’s need for relatedness and thus support their school engagement (Deci et al., 1991; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Within the extended attachment perspective, the teacher-child relationship is conceptualized using three dimensions: closeness, conflict and dependency (Pianta, 2001). In a positive, effective relationship the teacher functions as a “secure base” and “safe haven” for children, allowing them to explore the world and supporting their further social, emotional and academic development (Pianta, 1999; Verschueren and Koomen, 2012). However, it is not always evident for teachers to build a positive, close relationship with each child. Teachers experience both positive (e.g., joy, connectedness) and negative (e.g., anger, helplessness) emotions in relationships with children (Hargreaves, 2000; Cross and Hong, 2012; Hagenauer et al., 2015; de Ruiter et al., 2019; Frenzel et al., 2020). These emotions strongly impact teachers’ interactions with their children: joyful expressions tend to serve as an invitation for positive interactions, whereas anger may invoke a willingness to control the child’s behavior (Frenzel et al., 2009). Teachers’ emotions thus guide teachers’ responses to individual children and eventually have an important impact on children’s learning, classroom climate, and the overall quality of education (Frenzel et al., 2009; Malm, 2009; Kelchtermans and Deketelaere, 2016; Chen, 2019). Being aware of these emotions and having the necessary skills to cope with negative emotions is crucial for building close teacher-child relationships.

Research indicates that beginning teachers and teachers working with children with special educational needs are particularly prone to negative emotions and are more likely to experience conflict in their teacher-child relationships (Kelchtermans and Deketelaere, 2016; Zee et al., 2020; Zendarski et al., 2020; Roorda et al., 2021). Scholars have suggested that teachers are often not sufficiently prepared for the emotional and relational aspects of working with (special needs) children (Stempien and Loeb, 2002; Brunsting et al., 2014; Jo, 2014; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019; Aspelin et al., 2021). To date, teacher education programs primarily focus on formal (subject) knowledge and teaching skills, and pay far less attention to relational and emotional competencies that are necessary for building positive relationships with children (Jensen et al., 2015; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019). Additionally, teacher education has been criticized for focusing too much on theory and might not offer sufficient opportunities for pre-service teachers to “bridge the gap” with their practice (Korthagen, 2010a; 2010b). There is a great need for “programs emphasizing adequate care of teacher emotions, especially in relation to children (Jo, 2014, p.128).”

The literature suggests that it are teachers’ mental representations of relationships with children that guide their emotions in everyday interactions with children. Mental relationship representations comprise a set of internalized feelings and cognitions about the child and the relationships with that child that are based on a history of interactions with that child (Pianta, 1999; Spilt et al., 2011). More specifically, this mental representation consists of internalized mental representations of 1) the characteristics and needs of the child, 2) the self as a teacher of this student in various teaching roles (e.g., caregiver, instructor, disciplinarian, organizer, peer mediator), and 3) the quality of the dyadic relationship with that child (Bowlby, 1969/1982; Pianta, 1999; Spilt and Koomen, 2009). A teacher’s mental representation is automatically activated in everyday interactions with a child and guides (largely unconsciously) the teacher’s perceptions and interpretations of a particular child’s behavior. This, in turn, influences the behavior of the teacher toward the child. In layman’s terms, the internalized mental representation of the relationship is like a map for the teacher, providing internal “directions” that guide their interpersonal behavior in everyday interactions with a child (Pianta, 1999). This line of reasoning converges with the attachment theory of caregiver-child relationships and has become the dominant framework for the understanding of teacher-child relationships in current research (Sabol and Pianta, 2012; Verschueren and Koomen, 2012).

Teachers’ mental representations of relationships with children can be narrow, negative, and fixed, especially in relationships with children with problem behavior (e.g., “This student is always trying to make me angry”). Such maladaptive mental representations may activate negative emotions and biased or hostile causal attributions of child behavior (i.e., attributing control and negative intent to the student) in everyday interactions. Maladaptive mental representations may decrease teachers’ sensitivity to children’s needs, resulting in ineffective discipline strategies and increasingly coercive interactions (e.g., Stuhlman and Pianta, 2002). As a result, child problem behavior may increase. A vicious circle is likely to develop in which child problem behavior, in turn, reinforces the negative content of teachers’ mental representations and ineffective teacher behavior, and vice versa (c.f., Pianta, 1999; Doumen et al., 2008; de Ruiter et al., 2020). To break this circle, it is necessary to intervene at the level of the teacher’s representations of the relationship with the child. Teacher awareness of maladaptive mental representations and how these representations influence everyday interactions is a first critical step for successful coping with relationship difficulties and may be achieved through explicit, guided reflection (Pianta, 1999).

To help teachers cope with relationship difficulties, it is important that teachers become aware of underlying implicit feelings and beliefs that are part of their mental representations of teacher-child relationships. Broad and deep reflection, including the recognition and re-examination of both negative and positive beliefs and feelings regarding a child, can create a rich opportunity to increase teachers’ relational understanding and professional learning (Kelchtermans, 2019). In educational research, narratives are often used as a mean for reflection and professional development of in-service and preservice teachers (Kelchtermans, 2014).

To stimulate reflection on internalized beliefs and feelings, Pianta (1999) indicated that consultation needs to start with the teacher narrating the mental representation. The teacher needs to put words to internalized feelings and beliefs of which they may only subconsciously be aware. Through the construction of a narrative, teachers are challenged to go from implicit beliefs to explicit thoughts, from unawareness and taken-for-granted ideas to self-knowledge and reflection (Clemente and Ramírez, 2008; Kelchtermans, 2014). Pianta (1999) suggested that the Teacher Relationship Interview (TRI), a semi-structured narrative interview, can help a teacher to construct such a relationship narrative. A second step in consultation is to provide the teacher with a new perspective or framework to invoke a deeper understanding of their relationship with a child (Pianta, 1999). To this end, Pianta (1999) suggests that the consultant or coach presents a theory-based perspective that labels the teacher’s narrative of the relationship in a new way. By adding new information or a new perspective, the teacher is challenged to reconsider the narrative and to re-engage in the process of reflection. In addition, by linking everyday experiences to theoretical constructs the pedagogical understanding is strengthened. LLInC is based on this idea of guided construction of a relationship narrative as a basis for reflection and change. The goals of this type of intervention are to create a representation of the relationship with a child that a) is flexible and differentiated, b) is positive in tone or at least balanced between positive and negative emotions, and c) reflects a sense of agency by increasing feelings of competence as well as perceived impact on the child (Pianta, 1999). These changes in teachers’ mental relationship representations are believed to result in more positive, open, and flexible teacher behavior (Pianta, 1999; Spilt et al., 2012).

Recent research provided first evidence for the potential of LLInC among (regular) kindergarten and elementary school teachers. Spilt et al. (2012) found that LLInC improved the sensitive behavior of teachers towards individual children with externalizing behavior problems. LLInC was also shown to increase teachers’ perceptions of closeness and self-efficacy and decrease perceptions of conflict in relationships with individual children with whom the teachers at first experienced relationship difficulties (Bosman et al., 2021). In addition, LLInC has been tested as part of the multi-component intervention Key2Teach based on the idea that changing implicit mental representations is a necessary condition for improving teacher-child relationships. Key2Teach was shown to increase closeness and decrease conflict in relationships with children with externalizing problem behavior (Hoogendijk et al., 2019). The intervention also had positive effects on teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs and reduced emotional exhaustion (Hoogendijk et al., 2018). However, no research to date has investigated how LLInC may be implemented in teacher education to prepare student teachers for working with (special needs) children.

Answering the call of several scholars to address emotional and relational competencies in teacher training (Jo, 2014; Jensen et al., 2015; Korpershoek et al., 2016; Blömeke and Kaiser, 2017; Aspelin and Jonsson, 2019), this study is the first to examine how an existing intervention targeting teacher-child relationships can be implemented in teacher education. As teachers working with children with special educational needs are more prone to experience conflict in their relationships (Breeman et al., 2014; Roorda et al., 2021), the study focused on student teachers in a specialized program for teaching in special education. The aim of this study was to explore the impact of LLInC on student teachers’ relationships with children during their internship. To this end, the current study adopted a multiple single case design including six cases. A multiple single-case time-series study, with multiple measurements both before (pre-intervention phase) and after the intervention (post-intervention phase), is an appropriate study method to obtain empirical data about intervention efficacy in educational settings (Borckardt et al., 2008; Kratochwill, 2015). The current study included six student teachers with a professional bachelor’s degree enrolled in a 1-year specialized education program for teaching in special education. During their final internship, data were collected (on internship days) about teachers’ feelings and perceptions of their relationship with a (self-chosen) target child. The intervention was scheduled halfway the internship.

We expected that teachers’ positive emotions and positive relationship perceptions would increase and that their negative emotions and negative relationship perceptions would decrease after the intervention.

The study adopted a multiple single case design. A two-phase AB design, including multiple measures before and after the intervention, was implemented (Kratochwill, 2015).

Six student teachers participated voluntarily in the project during their internship in special education schools. The internship involved two teaching days a week over a period of 4 months. All six participating teachers had already obtained a professional bachelor’s degree (four teachers had a Bachelor in Teaching, one teacher had a Bachelor in Speech Therapy and one in Social Work; these last two also held a postgraduate teaching degree). All of them were now enrolled as students in a 1-year specialized program for teaching children with special educational needs. Researchers nor coaches were associated with the program. All teachers were female and born in Belgium. They were between 21 and 24 years old. All target children were boys and were born in Belgium, except for one child who was born in Albania. The children were between 5 and 13 years old. More detailed information on each student teacher and target child is provided in Table 1.

The study consisted of four phases (Figure 1): introduction and selection phase, pre-intervention phase, intervention phase, and post-intervention phase. Before the start of the project, the researchers contacted the teachers to obtain background information and inform them about the procedures. Two weeks into the internship, teachers chose a child with whom they experienced a more difficult relationship or felt no genuine contact. Both the teachers and parents of the target children completed an informed consent form. A daily questionnaire was administrated on internship days (two adjacent days a week) in the pre- and post-intervention phase during approximately 5 weeks in each phase. The intervention phase consisted of two sessions.

To describe the cases (Table 1), the teachers completed a questionnaire in the pre-intervention phase about their perceptions of their relationship with the target child. Teacher-child relationship quality was measured by the well-validated Student Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS, Koomen et al., 2007; Pianta, 2001). Two scales were administered: Closeness (11 items, e.g., “I share an affectionate, warm relationship with this child”; α = 0.93) and Conflict (11 items, e.g., “Dealing with this child drains my energy”; α = 0.94). The items were completed on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all applicable” 1) to “highly applicable” (5). Norm scores (M = 10, SD = 3) are reported along with their qualitative interpretation (Dutch norm group, see Koomen et al., 2007) in Table 1.

On each internship day of the pre- and post-intervention phase, a link to the online questionnaire (Limesurvey) was sent via e-mail to collect the teachers’ reports of emotions and relationship perceptions (Bolger et al., 2003). Mean scores across the two internship days per week were calculated to obtain scores per week. Outcome variables were chosen to represent the goals of LLInC, and thus to include both positive and negative emotions and relationship perceptions, as well as to reflect the teachers’ sense of agency.

Teachers had to answer the following question: “In the list below, you see several emotions which you may have experienced during the day. Please mark for each emotion to what extent you have felt that emotion in interaction with the target child.” Items were rated on a scale from “(almost) not” 1) to “very strongly” (5). Eight emotions were selected. First, the most basic emotions in everyday life, joy, anger, and worry (more appropriate and less strong equivalent for anxiety) were included (Frenzel et al., 2015). To cover emotions often experienced by (beginning) teachers, helplessness, competency, and doubt/insecurity were included (Spilt and Koomen, 2009; Pillen et al., 2013; Ria et al., 2003). These emotions also reflect teachers’ sense of agency and competence (cf. goals of LLInC). In addition, two relationship-focused emotions were included: connectedness and commitment (Pianta, 1999; Chang and Davis, 2009; Spilt et al., 2011).

Four items were included to measure teachers’ perceptions of their relationship with the individual child. Two items selected from the STRS (Pianta, 2001; Koomen et al., 2007) measured closeness (“Today, I shared an affectionate, warm relationship with this child“ and “My interactions with this child on this day made me feel effective and confident,” α = 0.74). Two items measured conflict (“Dealing with this child drained my energy today” and “This day, this child did things that I did not know how to handle,” α = 0.86). The first conflict item was also taken from the STRS. The second item was taken from the Teacher-perceived Control of Child Behavior (TCCB, Hammarberg and Hagekull, 2002). For both closeness and conflict, the first item primarily targeted the valence of teachers’ relationship perceptions, whereas the latter item rather focused on teachers’ sense of agency and competence in their interactions with the child. The items were completed on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all applicable” 1) to “highly applicable” (5).

LLInC (Leerkracht Leerling Interactie Coaching in Dutch, or: Teacher Student Interaction Coaching) is a Dutch coaching program for teachers aimed at improving individual teacher-child relationships. This intervention uses relationship-focused reflection as a means to elicit change in a teacher’s relationship representation and was previously referred to as the “Relationship-Focused Reflection Program” (Spilt et al., 2012). LLInC was individually administered by two university master’s students who were extensively trained to this purpose by the researchers. The coaching consisted of two one-on-one sessions with the teacher of about 1 hour.

Session 1: A first critical step in the reflection process is “to give words” to internalized cognitions and emotions, and to have the teacher construct a narrative of the relationship with the child in order to create awareness. To this end, the Teacher Relationship Interview was conducted (TRI, Pianta, 1999; Dutch version, Koomen and Lont, 2004). The TRI is a semi-structured, narrative interview that contains 12 questions referring to teachers’ interpersonal experiences with the target child (e.g., “Describe a time in the last week when you and the child really clicked”) and takes approximately 30–40 min. The teachers were asked to give real-life examples and to be as specific as possible. Follow-up questions prompt teachers to describe recent (everyday) situations and to describe the emotions of both themselves and the child in these situations. Because teachers are asked to provide detailed descriptions of events that actually happened, it is relatively easy and non-threatening for them to talk about the (sometimes intense) emotions they felt during that event.

After this session, coaches summarize and label the narrated experiences, beliefs, and feelings of the teacher in more general, theory-based terms. The labels that are used are derived from the TRI manual (Pianta, 1999; Spilt and Koomen, 2009): four labels refer to the teacher’s beliefs on interacting with the child, including teacher’s self-efficacy toward an individual child, (i.e., sensitivity of discipline, secure base, perspective taking, and intentionality) and four labels reflect the teacher’s feelings about the child and the relationship with the child (i.e., feelings of helplessness, negative affect, positive affect, and neutralizing of negative affect). The use of these labels to describe the quality of teacher-child relationships has been validated in regular as well as special education (cf. Stuhlman and Pianta, 2002; Spilt and Koomen, 2009; Koenen et al., 2019). The labels are presented in a bar graph as a unique “relational profile.” A large bar indicates that the construct is very present in the teacher’s narrative and can be considered a strength of the relationship. A small bar, in contrast, indicates a weakness in the relationship.

Session 2: In the second session, coaches present teachers this individual “relationship profile” and explain for each label why the teacher received either a high, a middle or a low bar. The coaches invite teachers to reflect on the profile, to agree or disagree, and, if wanted, to change the profile in accordance with their own beliefs. Teachers are further encouraged to draw an “ideal” (but still realistic) profile and to reflect on discrepancies between the presented profile and the “ideal” profile. Change talk is stimulated by coaches asking teachers what is needed to narrow the gap between the actual and ideal profile. Coaches ask teachers what their specific focus will be, what the effects of the envisaged change would be on the child and on themselves (to stimulate motivation for change), what concrete actions they can take to realize the change, and what they need to achieve the change. Teachers are encouraged to take notes during this session.

Data were analyzed at the single-subject level to model the intra-individual development of teachers’ emotions in and perceptions of the relationship with the target child. Visual between- and within-phases analyses were conducted (Lane and Gast, 2014; Tarlow et al., 2021). Per teacher, median-level differences between the pre-and post-intervention phases were calculated and trend lines within the phases were compared for each outcome variable to see if the intervention initiated positive developments or counteracted (stabilized or reversed) negative trends. Missing data due to absences of the child or the teacher (as reported in Table 1) were not replaced, as this could distort visual analyses.

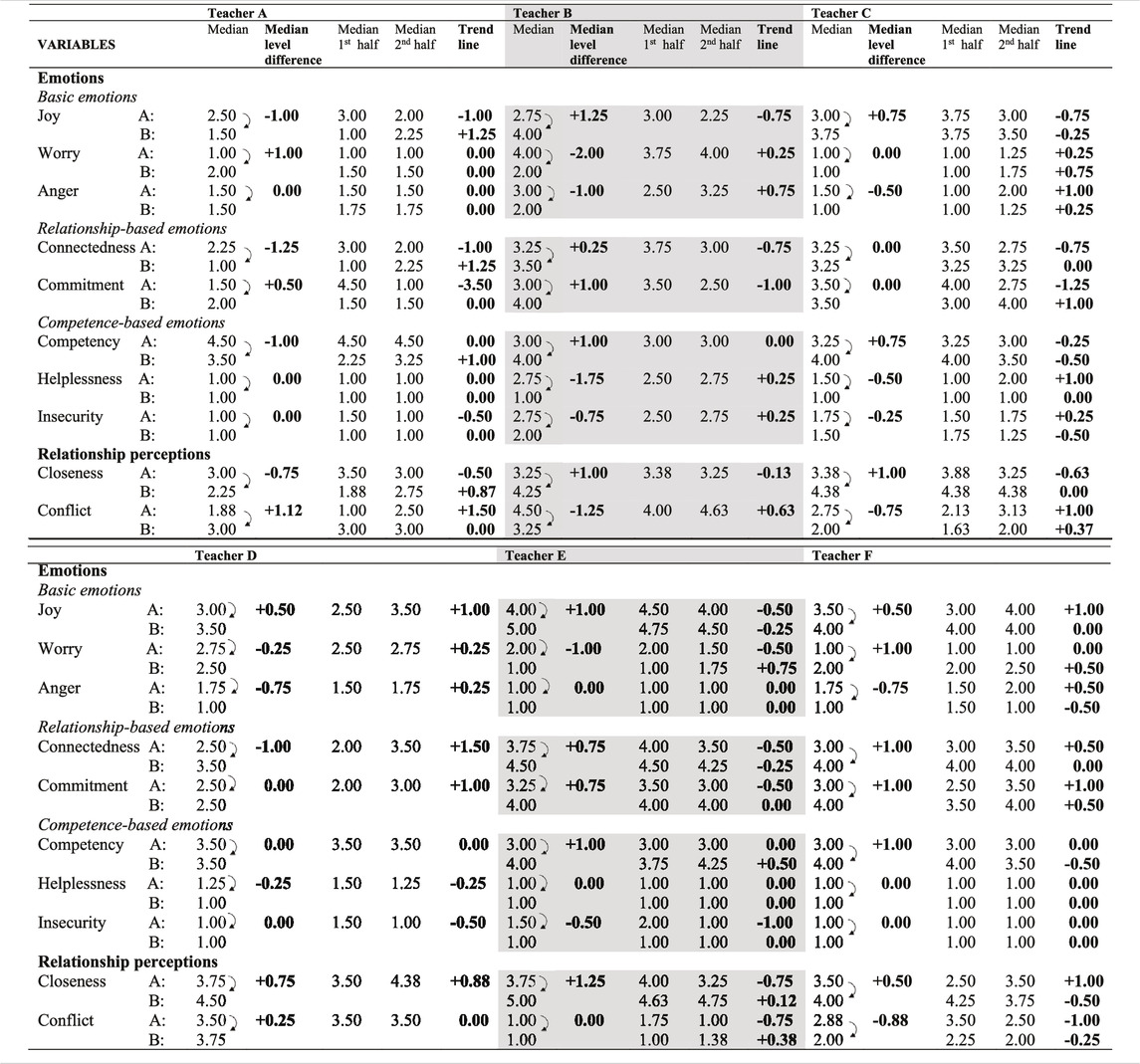

Table 2 presents a summary of the calculations of teachers’ emotions and relationship perceptions across the pre-and post-intervention phase, per teacher. The extensive tables as well as graphical displays of these results can be found in the Supplementary Material.

TABLE 2. Summary of the results of median level differences and trend lines of the 10 outcome variables for each teacher separately.

For teacher A, we found one median level difference between the phases in the expected direction: the teacher felt more committed to the child after the intervention. Six out of ten unexpected effects (i.e., negative intervention effects) were found: the teacher felt less joyful, less connected, less competent, perceived less closeness, was more worried, and perceived more conflict after the intervention.

However, when looking at the trend lines (i.e., median level change within phases, see Supplementary Figure S2) before and after the intervention, we found six positive trends: an increase in joy, connectedness, competency, and closeness after the intervention was observed. In addition, the decrease in commitment and the increase in conflict before the intervention were stabilized after the intervention. Worry, anger, insecurity, and helplessness remained (quite) stable during the study. Although the median effects between phases were opposite as to what we expected, the results suggested that the intervention positively impacted the teacher through reversing or stabilizing the negative development in emotions and perceptions that was seen before the intervention. Thus, the intervention yielded a preventive effect for this teacher-child dyad.

For teacher B, we found median level differences between the phases in the expected direction for all 10 outcomes. This suggested that the intervention was very effective for this teacher. Unfortunately, no trend lines after the intervention could be calculated due to too few measurements.

For teacher C, we found median level differences between the phases in the expected direction for seven of the 10 outcomes: the teacher felt more joyful and competent, felt less angry, helpless, and insecure, and perceived more closeness and less conflict. No unexpected or negative effects were found.

When looking at the trend lines before and after the intervention (Supplementary Figure S6), we found five positive trends and five (small) negative trends. The intervention could not counteract the negative trends in the basic emotions but did positively change the trends in connectedness, commitment, helplessness as well as in the perception of closeness. The results suggest a more mixed profile and raise the question whether the initial positive effects in the first half of the post-intervention phase are unstable or fading away. It is interesting that despite negative trends for the basic emotions (small decrease in joy and small increase of anger and worry), the intervention initiated a substantial increase in commitment and halted the downward development in closeness and connectedness. This indicated a positive impact of the intervention on the teacher’s relationship-specific emotions and perceptions.

For teacher D, we found median level differences between the phases in the expected direction for five of the 10 outcomes: the teacher felt more joyful, perceived more closeness, and felt less worried, angry, and helpless after the intervention. Two unexpected effects were found: a decrease in feeling connected and a (small) increase in perceived conflict were observed. Overall, the positive effects of the intervention appeared more prominent.

Unfortunately, no trend lines after the intervention could be calculated due to too few measurements.

For teacher E, we found positive median level pre-post differences for seven of the 10 outcomes: the teacher felt more joyful, competent, connected, committed, and close, and less worried and insecure after the intervention. No unexpected median level differences were found. Looking at the trend lines before and after the intervention (Supplementary Figure S10), we found four positive trends for commitment, competency, insecurity, and closeness. In addition, four (small) negative trends were found for joy, worry, connectedness, and conflict. This suggests a more mixed profile and raises the question whether the initial positive effects in the first half of the post-intervention phase are unstable or fading away. Again, it is interesting that despite negative trends in the development of basic emotions, the intervention yielded an increase in competency and closeness and could stop the decrease in commitment and insecurity.

For teacher F, we found positive median level pre-post differences for seven of the 10 outcomes: the teacher felt more joyful, connected, committed, competent, and close, and reported less anger and conflict after the intervention. One negative effect was found: the teacher felt more worried after the intervention.

When looking at the trend lines pre- and postintervention (Supplementary Figure S12), we found one distinct positive effect on the development of anger and three negative effects on the development of worry, competency, and closeness. Together, this suggests both positive and negative intervention effects.

Relationships with children are an important source of various positive and negative teacher emotions. Beginning teachers are more prone to experience negative emotions in teacher-child interactions and can have difficulties establishing close relationships, particularly in special education settings. Negative emotions and conflictual relationships can in turn undermine teachers’ sensitivity to the specific needs of children and endanger the well-being of both the child and the teacher. Teacher training programs need to prepare teachers for the emotional and relational challenges of teaching. To this end, we investigated the effects of LLInC, a relationship-focused coaching method, on teacher-child relationships in a sample of volunteer student teachers enrolled in a training program for special education.

The results indicated that the intervention affected all teacher-child relationships, either by improving relationship quality (Teacher B), preventing or stopping declines in relationship quality (Teacher A and Teacher C), or by inducing both positive and negative effects (Teacher D, Teacher E, and Teacher F). For all teachers, except for Teacher A, positive effects were found on feelings of joy and perceptions of closeness. Preventive effects (i.e., stopping downward trends) were more often observed for competence-based and relationship-based emotions and perceptions (e.g., competence, commitment, closeness) than for basic emotions (e.g., joy, anger, worry).

For some teachers we found a mix of both positive and negative effects. Importantly, increases in negative emotions and perceptions such as worry and conflict may not necessarily be negative for the teacher-child relationship as long as they are accompanied with (increases in) positive emotions, which was the case in our sample. Reflection may result in the recognition and/or release of negative emotions that were previously hidden or denied by the teacher. Increases in for instance worry can perhaps be explained by more awareness of the troubles in the relationship due to the insights of the intervention. Spilt et al. (2012) also found mixed intervention effects for a small subset of teachers who improved in observed sensitive behavior in interactions with the target child but at the same time reported more conflict. Bosman et al. (2019) reported mixed results for teachers’ perceptions of conflict but found quite consistent effects of LLInC on closeness. Moreover, LLInC does not aim to avoid negative feelings and perceptions but strives to accept both the “good and the bad” in the relationship. LLInC aims to create a balance between positive and negative emotions and promotes a differentiated and flexible understanding of the relationship with the child (Pianta, 1999), in such way that the teacher can receive the child, is able to recognize and respond to the child’s signals, and is committed to the relationship with the child in spite of difficulties.

The results revealed differential intervention effects across teachers. Teacher B, for example, showed positive results on all outcomes. Interestingly, this teacher reported a very high level of conflict with the target child at the start of the study. In contrast, Teacher A showed a less straightforward patterns of results. At the start of the intervention, Teacher A reported low levels of both closeness and conflict, which suggests a “distant” relationship with the target child. A distant relationship between teacher and child is typically characterized by an absence of prominent feelings and proximate interactions (Spilt and Koomen, 2009). In addition, Teacher A reported declining relationship patterns, which however, could be partly stopped or reversed through the intervention. LLInC may thus have had a preventive effect but the intervention may not have been extensive enough to truly improve the teacher-child relationship. More research is needed to investigate for which relationship types and problems LLInC may yield the best outcomes.

As scholars advocate the need to better “care” for teacher emotions by preparing student teachers for the emotional-relational dimension of teaching children (Jo, 2014; Jensen et al., 2015), this study examined how LLInC can help student teachers understand their relational experiences with children during their final internship. Student teachers were engaged in a reflective process on their relationship with a self-chosen “challenging” child. Through narrative construction by reflection on concrete events and associated (negative) emotions, and by making the connection between their everyday experiences and theoretical concepts, guided by a coach, LLInC may facilitate the transfer from theory to practice. In this way, we expect that student teachers will be better prepared for the emotional-relational challenges inherent to teaching when they enter the profession. Results of the study highlight the potential of implementing existing interventions in teacher education. One other intervention targeting teacher-child relationships is Playing-2-gether (Vancraeyveldt et al., 2015), which was adapted and successfully integrated in to a pre-primary teacher education program (Huyse et al., 2016). In the same way, LLInC could be adapted and integrated into the program and support all pre-service teachers in reflecting on their teacher-child relationships.

This multiple case study provides new evidence for the effectiveness of LLInC among student teachers. However, some methodological limitations must be considered in weighing the results. Due to the constraints of the educational program (short length of the internship and low intensity, i.e., 2 days a week) it was not possible to collect daily measurements, examine transfer effects to teacher behavior, or to conduct follow-up research to examine long-term (or sleeper) effects. In addition, because LLInC was presented as an extra to the educational program, a randomized controlled trial was not possible and student teachers participated voluntary, which may have impacted the results. Furthermore, the intensity of the intervention should be considered. The participants’ feedback after the study suggested extending LLInC with a follow-up session to discuss and evaluate the improvements they experienced in their work with the child. Although there is ample evidence that brief reflective exercises targeting beliefs and feelings of children can induce lasting change (cf., Yeager and Walton, 2011), for some teachers, more sessions may have yielded stronger results. In previous research, two target children instead of one child were selected, resulting in a total of four intervention sessions (Spilt et al., 2012; Bosman et al., 2019; Bosman et al., 2021). In this way, teachers could recognize similarities and differences in the relationships with different children. This might deepen the reflective process and may help teachers to distinguish between unique elements in each relationship versus the teacher’s personal style of relating to children (e.g., Spilt et al., 2012). Notably, (Bosman et al., 2019) only found improvements in daily measurements for the second selected child. However, due to the length of the internship it was not possible to implement four intervention sessions in this study. Future research needs to examine the implementation and effectiveness of LLInC in internship programs in multiple teacher programs including all internship students.

Relationships with children are a primary source of (sometimes intense) positive and negative teacher emotions. This is particularly true for beginning teachers, who can have difficulties building close relationships or coping with conflictual relationships with children, especially in special education settings. Scholars have repeatedly suggested that teacher education programs do not focus sufficiently on teachers’ relational and emotional competencies. We investigated the potential of LLInC to be implemented during pre-service teachers’ final internship in special education. Results revealed differential intervention effects on pre-service teachers’ emotions and their perceptions of teacher-child relationships. Notably, the intervention affected all teacher-child relationships, either by improving relationship quality, preventing or stopping declines in relationship quality, or by inducing a combination of positive and negative effects. Further research is needed to investigate these differential effects across teachers and relationship types. Through guided reflection and connecting everyday internships experiences and theoretical concepts, LLInC might offer pre-service teachers a unique chance to bridge the gap between theory and practice. The integration of LLInC might strengthen teacher education programs in preparing future teachers for the emotional and relational challenges that are inherent to teaching.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee, KU Leuven. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

JS was responsible for conceptualization and supervision of the study. JS and A-KK contributed to design and methodology. JS and AD provided the necessary resources. A-KK was responsible for project administration and data collection, performed the analyses, and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to review and editing of the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

We are grateful to the teacher education, schools, and student teachers who participated in this study. We are especially grateful to the two master students, who administered the intervention after training: Andrea Peers and Emily Huyghe.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.769573/full#supplementary-material

Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., and Trautwein, U. (2018). Student Misbehavior and Teacher Well-Being: Testing the Mediating Role of the Teacher-Student Relationship. Learn. Instruction 58, 126–136. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006

Aspelin, J., and Jonsson, A. (2019). Relational Competence in Teacher Education. Concept Analysis and Report from a Pilot Study. Teach. Development 23 (2), 264–283. doi:10.1080/13664530.2019.1570323

Aspelin, J., Östlund, D., and Jönsson, A. (2021). Pre-Service Special Educators' Understandings of Relational Competence. Front. Educ. 6, 678793. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.678793

Blömeke, S., and Kaiser, G. (2017). “Understanding the Development of Teachers' Professional Competencies as Personally, Situationally and Socially Determined,”. The SAGE Handbook of Research on Teacher Education. Editors D. J. Clandinin, and J. Husu (London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications), Vol. 2, 783–802. doi:10.4135/9781529716627

Bolger, N., Davis, A., and Rafaeli, E. (2003). Diary Methods: Capturing Life as it Is Lived. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 54, 579–616. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030

Borckardt, J. J., Nash, M. R., Murphy, M. D., Moore, M., Shaw, D., and O'Neil, P. (2008). Clinical Practice as Natural Laboratory for Psychotherapy Research: a Guide to Case-Based Time-Series Analysis. Am. Psychol. 63 (2), 77–95. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.63.2.77

Bosman, R. J., Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Using Relationship-Focused Reflection to Improve Teacher-Child Relationships and Teachers' Student-specific Self-Efficacy. J. Sch. Psychol. 87, 28–47. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2021.06.001

Bosman, R. J., de Jong, P. F., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2019). Improving Teacher-Child Relationships Using Relationship-Focused Reflection: A Case Study. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. University of Amsterdam.

Breeman, L. D., Tick, N. T., Wubbels, T., Maras, A., and Lier, P. A. C. V. (2014). “Problem Behaviour and the Development of the Teacher-Child Relationship in Special Education,” in Interpersonal Relationships in Education: From Theory to Practice. Editors D. B. Zandvliet, P. den Brok, T. Mainhard, and J. van Tartwijk (Rotterdam, NL: Sense Publishers), 25–35. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-701-8_3

Brunsting, N. C., Sreckovic, M. A., and Lane, K. L. (2014). Special Education Teacher Burnout: A Synthesis of Research from 1979 to 2013. Education Treat. Child. 37 (4), 681–711. doi:10.1353/etc.2014.0032

Chang, M.-L., and Davis, H. A. (2009). “Understanding the Role of Teacher Appraisals in Shaping the Dynamics of Their Relationships with Students: Deconstructing Teachers' Judgments of Disruptive Behavior/Students,” in Advances in Teacher Emotion Research: The Impact on Teachers' Lives. Editors P. A. Schutz, and M. Zembylas (Springer), 95–127. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0564-2_6

Chen, J. (2019). Exploring the Impact of Teacher Emotions on Their Approaches to Teaching: A Structural Equation Modelling Approach. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 89 (1), 57–74. doi:10.1111/bjep.12220

Clemente, M., and Ramírez, E. (2008). How Teachers Express Their Knowledge through Narrative. Teach. Teach. Education 24 (5), 1244–1258. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2007.10.002

Corbin, C. M., Alamos, P., Lowenstein, A. E., Downer, J. T., and Brown, J. L. (2019). The Role of Teacher-Student Relationships in Predicting Teachers' Personal Accomplishment and Emotional Exhaustion. J. Sch. Psychol. 77, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2019.10.001

Cross, D. I., and Hong, J. Y. (2012). An Ecological Examination of Teachers' Emotions in the School Context. Teach. Teach. Education 28 (7), 957–967. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2012.05.001

de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M. G., Aldrup, K., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2020). Teachers' Emotional Experiences in Response to Daily Events with Individual Students Varying in Perceived Past Disruptive Behavior. J. Sch. Psychol. 82, 85–102. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2020.08.005

de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M. G., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2019). Relevant Classroom Events for Teachers: A Study of Student Characteristics, Student Behaviors, and Associated Teacher Emotions. Teach. Teach. Education 86, 102899. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.102899

Deci, E., Vallerand, R., Pelletier, L., and Ryan, R. (1991). Motivation and Education: The Self-Determination Perspective. Hedp 26 (34), 325–346. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep2603&4_6

Doumen, S., Verschueren, K., Buyse, E., Germeijs, V., Luyckx, K., and Soenens, B. (2008). Reciprocal Relations between Teacher-Child Conflict and Aggressive Behavior in Kindergarten: a Three-Wave Longitudinal Study. J. Clin. Child. Adolesc. Psychol. 37 (3), 588–599. doi:10.1080/15374410802148079

Evans, D., Butterworth, R., and Law, G. U. (2019). Understanding Associations between Perceptions of Student Behaviour, Conflict Representations in the Teacher-Student Relationship and Teachers' Emotional Experiences. Teach. Teach. Education 82, 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.008

Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., and Goetz, T. (2015). Teaching This Class Drives Me Nuts!--Examining the Person and Context Specificity of Teacher Emotions. PLoS One 10 (6), e0129630. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129630

Frenzel, A. C., Fiedler, D., Marx, A. K. G., Reck, C., and Pekrun, R. (2020). Who Enjoys Teaching, and when? between- and Within-Person Evidence on Teachers' Appraisal-Emotion Links. Front. Psychol. 11, 1092. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01092

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Stephens, E. J., and Jacob, B. (2009). “Antecedents and Effects of Teachers' Emotional Experiences: An Integrated Perspective and Empirical Test,” in Advances in Teacher Emotion Research, 129–151. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0564-2_7

Hagenauer, G., Hascher, T., and Volet, S. E. (2015). Teacher Emotions in the Classroom: Associations with Students' Engagement, Classroom Discipline and the Interpersonal Teacher-Student Relationship. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 30 (4), 385–403. doi:10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

Hammarberg, A., and Hagekull, B. (2002). The Relation between Pre-school Teachers' Classroom Experiences and Their Perceived Control over'Child Behaviour. Early Child. Development Care 172 (6), 625–634. doi:10.1080/03004430215099

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed Emotions: Teachers' Perceptions of Their Interactions with Students. Teach. Teach. Education 16, 811–826. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00028-7

Hoogendijk, C., Tick, N. T., Hofman, W. H. A., Holland, J. G., Severiens, S. E., Vuijk, P., et al. (2018). Direct and Indirect Effects of Key2Teach on Teachers' Sense of Self-Efficacy and Emotional Exhaustion, a Randomized Controlled Trial. Teach. Teach. Education 76, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.014

Hoogendijk, K., Holland, J. G., Tick, N. T., Hofman, A. W. H., Severiens, S. E., Vuijk, P., et al. (2019). Effect of Key2Teach on Dutch Teachers' Relationships with Students with Externalizing Problem Behavior: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 35, 111–135. doi:10.1007/s10212-019-00415-x

Huyse, M., Vancraeyveldt, C., Bertrands, E., Vastmans, K., Peeters, E., Borghgraef, F., et al. (2016). Samen-Spel in de klas. Kleuters & ik 32 (4), 6–10.

Jensen, E., Skibsted, E. B., and Christensen, M. V. (2015). Educating Teachers Focusing on the Development of Reflective and Relational Competences. Educ. Res. Pol. Prac. 14 (3), 201–212. doi:10.1007/s10671-015-9185-0

Jo, S. H. (2014). Teacher Commitment: Exploring Associations with Relationships and Emotions. Teach. Teach. Education 43, 120–130. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2014.07.004

Kelchtermans, G., and Deketelaere, A. (2016). “The Emotional Dimension in Becoming a Teacher,” in International Handbook of Teacher Education. Editors J. Loughran, and M. Hamilton (Springer), 429–461. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-0369-1_13

Kelchtermans, G. (2019). “Early Career Teachers and Their Need for Support: Thinking Again,” in Attracting and Keeping the Best Teachers. Editors A. Sullivan, B. Johnson, and M. Simons (Springer), 83–98. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-8621-3_5

Kelchtermans, G. (2014). “Narrative-biographical Pedagogies in Teacher Education,” in International Teacher Education: Promising Pedagogies - Part A. Editors L. Orland-Barak, (Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing), 273–291. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00666-710.1108/s1479-368720140000022017

Kincade, L., Cook, C., and Goerdt, A. (2020). Meta-Analysis and Common Practice Elements of Universal Approaches to Improving Student-Teacher Relationships. Rev. Educ. Res. 90 (5), 710–748. doi:10.3102/0034654320946836

Koenen, A.-K., Vervoort, E., Verschueren, K., and Spilt, J. L. (2019). Teacher-student Relationships in Special Education: the Value of the Teacher Relationship Interview. J. Psychoeducational Assess. 37 (7), 874–886. doi:10.1177/0734282918803033

Koomen, H. M. Y., and Lont, T. A. E. (2004). Teacher Relationship Interview: Qualitative Coding Manual. [Ongepubliceerde Nederlandse Vertaling]. Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Koomen, H. M. Y., Verschueren, K., and Pianta, R. C. (2007). Leerling Leerkracht Relatie Vragenlijst - Handleiding [Manual of Student Teacher Relationship Scale]. Houten, NL: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., and Doolaard, S. (2016). A Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Classroom Management Strategies and Classroom Management Programs on Students' Academic, Behavioral, Emotional, and Motivational Outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 86 (3), 643–680. doi:10.3102/0034654315626799

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2010a). How Teacher Education Can Make a Difference. J. Education Teach. 36 (4), 407–423. doi:10.1080/02607476.2010.513854

Korthagen, F. A. J. (2010b). “The Relationship between Theory and Practice in Teacher Education,”. International Encyclopedia of Education. Editors E. Baker, B. McGaw, and P. Peterson (Elsevier), 7, 669–675. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-044894-7.00638-2

Kratochwill, T. R. (2015). “Single-case Research Design and Analysis: An Overview,” in Single-case Research Design and Analysis. New Directions for Psychology and Education. Editors T. R. Kratochwill, and J. R. Levin (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–14.

Lane, J. D., and Gast, D. L. (2014). Visual Analysis in Single Case Experimental Design Studies: Brief Review and Guidelines. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 24 (3-4), 445–463. doi:10.1080/09602011.2013.815636

Malm, B. (2009). Towards a New Professionalism: Enhancing Personal and Professional Development in Teacher Education. J. Education Teach. 35 (1), 77–91. doi:10.1080/02607470802587160

McGrath, K. F., and Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, Why and to what End? Students at Risk of Negative Student-Teacher Relationships and Their Outcomes. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing Relationships between Children and Teachers. Washington, DC: APA. doi:10.1037/10314-000

Pianta, R. C. (2001). Student-Teacher Relationship Scale: Professional Manual. Lutz: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Pillen, M., Beijaard, D., and Brok, P. d. (2013). Tensions in Beginning Teachers' Professional Identity Development, Accompanying Feelings and Coping Strategies. Eur. J. Teach. Education 36 (3), 240–260. doi:10.1080/02619768.2012.696192

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective Teacher-Student Relationships and Students' Engagement and Achievement: A Meta-Analytic Update and Test of the Mediating Role of Engagement. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 46 (3), 239–261. doi:10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

Roorda, D. L., Zee, M., Bosman, R. J., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2021). Student-teacher Relationships and School Engagement: Comparing Boys from Special Education for Autism Spectrum Disorders and Regular Education. J. Appl. Developmental Psychol. 74, 101277. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101277

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 55 (1), 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sabol, T. J., and Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent Trends in Research on Teacher-Child Relationships. Attach. Hum. Dev. 14 (3), 213–231. doi:10.1080/14616734.2012.672262

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M., Thijs, J. T., and van der Leij, A. (2012). Supporting Teachers' Relationships with Disruptive Children: the Potential of Relationship-Focused Reflection. Attach. Hum. Dev. 14 (3), 305–318. doi:10.1080/14616734.2012.672286

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., and Thijs, J. T. (2011). Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher-Student Relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23 (4), 457–477. doi:10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y

Spilt, J. L., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2009). Widening the View on Teacher-Child Relationships: Teachers' Narratives Concerning Disruptive versus Nondisruptive Children. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 38 (1), 86–101. doi:10.1080/02796015.2009.12087851

Stempien, L. R., and Loeb, R. C. (2002). Differences in Job Satisfaction between General Education and Special Education Teachers. Remedial Spec. Education 23 (5), 258–267. doi:10.1177/07419325020230050101

Stuhlman, M. W., and Pianta, R. C. (2002). Teachers' Narratives about Their Relationships with Children: Associations with Behavior in Classrooms. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 31 (2), 148–163. doi:10.1080/02796015.2002.12086148

Tarlow, K. R., Brossart, D. F., McCammon, A. M., Giovanetti, A. J., Belle, M. C., Philip, J., et al. (2021). Reliable Visual Analysis of Single-Case Data: A Comparison of Rating, Ranking, and Pairwise Methods. Cogent Psychol. 8 (1), 1911076. doi:10.1080/23311908.2021.1911076

Vancraeyveldt, C., Verschueren, K., Wouters, S., Van Craeyevelt, S., Van Den Noortgate, W., and Colpin, H. (2015). Improving Teacher-Child Relationship Quality and Teacher-Rated Behavioral Adjustment Amongst Externalizing Preschoolers: Effects of a Two-Component Intervention. J. Abnorm Child. Psychol. 43 (2), 243–257. doi:10.1007/s10802-014-9892-7

Verschueren, K., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Teacher-child Relationships from an Attachment Perspective. Attach. Hum. Dev. 14 (3), 205–211. doi:10.1080/14616734.2012.672260

Yeager, D. S., and Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-Psychological Interventions in Education. Rev. Educ. Res. 81 (2), 267–301. doi:10.3102/0034654311405999

Zee, M., de Bree, E., Hakvoort, B., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2020). Exploring Relationships between Teachers and Students with Diagnosed Disabilities: A Multi-Informant Approach. J. Appl. Developmental Psychol. 66, 101101. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2019.101101

Zee, M., de Jong, P. F., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). From Externalizing Student Behavior to Student-specific Teacher Self-Efficacy: The Role of Teacher-Perceived Conflict and Closeness in the Student-Teacher Relationship. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 51, 37–50. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.06.009

Keywords: relationship-focused reflection, LLInC (teacher student interaction coaching), teacher emotions, special education, teacher-child relationship

Citation: Koenen A-K, Borremans LFN, De Vroey A, Kelchtermans G and Spilt JL (2021) Strengthening Individual Teacher-Child Relationships: An Intervention Study Among Student Teachers in Special Education. Front. Educ. 6:769573. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.769573

Received: 02 September 2021; Accepted: 18 October 2021;

Published: 08 November 2021.

Edited by:

Matteo Angelo Fabris, University of Turin, ItalyReviewed by:

John Mark R. Asio, Gordon College, PhilippinesCopyright © 2021 Koenen, Borremans, De Vroey, Kelchtermans and Spilt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Liedewij Frieke Nel Borremans, bGllZGV3aWouYm9ycmVtYW5zQGt1bGV1dmVuLmJl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.